Robert Knox's Blog, page 43

March 20, 2016

The Garden of Verse: Floral Visions Afloat on "Houseboat"

As of Friday, March 18, I've had the happy experience of being "Featured Poet No. 58" on Houseboat, an online journal that sees itself as an "amalgam" of the arts. I've been happily floating on this metaphor (and on the host website (houseboat.blogspot.pe) ever since. Six of my garden poems have been paired with luscious photos for my tenure as "feature poet." (All the photos are by Rose Mary Boehm.) Five of these poems were originally published by Verse-Virtual.com, the online journal for which I've been writing on a monthly basis. In my mind, at least, the poems hang together well as a group. Putting them in the same 'boat' with some lovely flowerful photos accomplishes, in my opinion, just what the editors are trying to do -- putting the two arts "in the same boat" in a mutually beneficial way. "A houseboat is an amalgam," the Houseboat Team states. "Not just a place to live, not just a water vessel. It is both—stable, yet allowing movement. The arts are often viewed in separate boxes...There aren't enough artistic outlets that truly cross boundaries." This site does. And as you can tell from the above, many other Houseboat combos of words and pictures are there to be explored on this innovative site. After all I may be the presently featured passenger, but I'm only number 58. All those other happy poet-passengers are still available for a cruise.

As of Friday, March 18, I've had the happy experience of being "Featured Poet No. 58" on Houseboat, an online journal that sees itself as an "amalgam" of the arts. I've been happily floating on this metaphor (and on the host website (houseboat.blogspot.pe) ever since. Six of my garden poems have been paired with luscious photos for my tenure as "feature poet." (All the photos are by Rose Mary Boehm.) Five of these poems were originally published by Verse-Virtual.com, the online journal for which I've been writing on a monthly basis. In my mind, at least, the poems hang together well as a group. Putting them in the same 'boat' with some lovely flowerful photos accomplishes, in my opinion, just what the editors are trying to do -- putting the two arts "in the same boat" in a mutually beneficial way. "A houseboat is an amalgam," the Houseboat Team states. "Not just a place to live, not just a water vessel. It is both—stable, yet allowing movement. The arts are often viewed in separate boxes...There aren't enough artistic outlets that truly cross boundaries." This site does. And as you can tell from the above, many other Houseboat combos of words and pictures are there to be explored on this innovative site. After all I may be the presently featured passenger, but I'm only number 58. All those other happy poet-passengers are still available for a cruise. Here's my direct link:

http://houseboathouse.blogspot.pe/201...

I'm also happy to report that the March 15 issues of Scarlet Leaf Review has published three of my poems, including a poem ("Sidewalk Madonnas") about Syrian refugees trying to make ends meet by begging on the streets of Beirut. (http://www.scarletleafreview.com/poem... can't fault Lebanon, a very small country that by now is sheltering an estimated 1.5 million displaced Syrians. While European countries are freaking out over taking in a few thousand, and in the US politicians aren't even willing to discuss the possibility of accepting Syrian refugees here. Worldwide, everybody else decided not to get involved -- except for Russia, perfectly content to kill more civilians, and create more refugees, by bombing rebel districts in behalf of blood-thirsty tyrant Bashar al-Assad -- with the result that an entire nation has been torn apart, with millions running for cover. And I am not happy to report that the Scarlet Leaf Review is ceasing publication after the current issue. It's a well put-together, diverse, free-wheeling journal that was certainly good to me. And editor Roxana Natase was more than typically responsive to questions and comments by contributors. She also volunteered frequent updates on traffic by readers: the journal was typically receiving more than 3,000 visits per day. But it's spring. We'll miss the "Scarlet Leaf," but new growth will take its place

Published on March 20, 2016 14:21

March 17, 2016

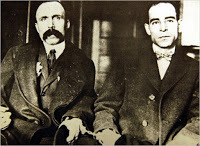

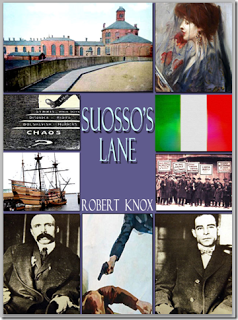

Were Sacco and Vanzetti Guilty After All? How Bill Bryson Blew It

After my program Tuesday night on "Suosso's Lane," a novel of the Sacco-Vanzetti case, an old friend pointed out to me that famous author Bill Bryson in his recent book "One Summer: America 1927" concludes that Sacco and Vanzetti were "probably" guilty of robbing a workers' payroll and killing two men in the Braintree shoe factory crime. This is how I know Bryson blew it: He gets crucial facts wrong before delivering his smug, complacent apology for the status quo. After pointing out basic flaws in the state's improbable case against Sacco and Vanzetti, Bryson suddenly changes sides when he returns to the subject of the Sacco-Vanzetti case 20 pages later and now is all sympathy with the nativist, WASP establishment apologists for the judicial murder of two Italian political radicals during a time of racist hysteria over immigration by the "lower races." Here's the first of two incredible "howlers" (scholar talk for blatant mistakes) that show Bryson was not on top of his material: With the 1927 execution date two weeks away, Bryson writes, Massachusetts Governor Alvan Fuller granted a brief stay of execution to allow "the condemned men's defense team -- which was essentially the lone, harried lawyer Fred Moore -- twelve days to find a court prepared to grant a retrial to hear new evidence." How completely wrong is this? Defense lawyer Fred Moore had officially withdrawn from the case three years before (and ceased acting for the defense the year before that) after Sacco refused to speak to him any longer. In 1927 Sacco and Vanzetti's defense was led by the prestigious William G. Thompson, widely regarded as Boston's top lawyer, a thoroughly Brahmin establishment figure who took Sacco and Vanzetti's case because the obvious flaws in their trial offended his sense of justice (and after the defense committee raised his healthy fee). And despite Bryson's snide comment, Fred Moore was never a "lone" anything. An active Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee raised funds first to hire both Moore (a California labor attorney) and a team of assistants. The Defense Committee later provided funds for Thompson and his assistants. No "lone, harried" defender, but a team of lawyers chased US Supreme Court justices around the county looking to convince a judge to hear their pleas for a new trial and save their clients' lives. The second, and even more unforgivable goof is Bryson's wholly inaccurate claim that highly regarded historian Paul Avrich, in his influential 1991 book "Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background," states that Sacco and Vanzetti were "almost certainly involved" in the Braintree robbery-murder. Bryson states (inaccurately): "In his 1991 book, historian Paul Avrich asked rhetorically whether Vanzetti could have been involved in the South Braintree holdup, and wrote: 'Though the evidence is far from satisfactory, the answer almost certainly is yes. The same holds true for Sacco.'" The actual quote (on page 150 in Avrich's book) is this: "Was Vanzetti himself involved in the conspiracy? Though the evidence is far from satisfactory, the answer almost certainly is yes. The same holds true for Sacco.'" The "conspiracy" Avrich refers to in this statement is not the Braintree holdup but a series of bombings (in 1918-19) widely attributed to anarchists. Anyone looking at the quote on the page will come to the same conclusion. The sentence that Bryson twists to his own purpose directly follows Avrich's lengthy account of how Italian anarchists turned to the use of bombs to strike back at the government officials and big capitalists that were persecuting them and, as they believed, oppressing the poor. That "conspiracy" included planting a bomb at the home of the US Attorney General, an act that precipitated massive arrests of immigrants and deportations and -- as many students of the case have argued -- the framing of known anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti for the Braintree crime. Those bombings (for whom no one was ever put on trial) and the Braintree shoe factory robbery-murder are entirely different cases. The only thing that puts the cases together is the state of Massachusetts' improbable theory that anarchists were responsible for the Braintree crime. Avrich may believe that Vanzetti and Sacco were "almost certainly" involved (in some unspecified way) in the Italian anarchist bombing conspiracy. He clearly does believe that they were members of the same network as the key anarchist figures he fingers as the principal conspirators (Carlo Valdinoci and Mario Budo). But when it comes to whether Sacco and Vanzetti bore any guilt for the Braintree crime, Avrich states explicitly that his book "makes no pretense of settling the issue of whether Sacco and Vanzetti were guilty of the crimes for which they were executed" (page 5). He states, instead, that the case against them "remains unproved... nor can their innocence be established beyond any shadow of doubt." It's hard for me to believe that an author of Bryson's stature could have bollixed this up so badly unless, perhaps, he was working from notes made by others. Nevertheless, the representation of a respected historian's judgment about one matter as his judgment on a distinctly different matter is not merely sloppiness, it's the kind of academic wrongdoing that would get your PhD thesis thrown out of court. In my opinion, it destroys Bryson's credibility as a commentator on the case.

After my program Tuesday night on "Suosso's Lane," a novel of the Sacco-Vanzetti case, an old friend pointed out to me that famous author Bill Bryson in his recent book "One Summer: America 1927" concludes that Sacco and Vanzetti were "probably" guilty of robbing a workers' payroll and killing two men in the Braintree shoe factory crime. This is how I know Bryson blew it: He gets crucial facts wrong before delivering his smug, complacent apology for the status quo. After pointing out basic flaws in the state's improbable case against Sacco and Vanzetti, Bryson suddenly changes sides when he returns to the subject of the Sacco-Vanzetti case 20 pages later and now is all sympathy with the nativist, WASP establishment apologists for the judicial murder of two Italian political radicals during a time of racist hysteria over immigration by the "lower races." Here's the first of two incredible "howlers" (scholar talk for blatant mistakes) that show Bryson was not on top of his material: With the 1927 execution date two weeks away, Bryson writes, Massachusetts Governor Alvan Fuller granted a brief stay of execution to allow "the condemned men's defense team -- which was essentially the lone, harried lawyer Fred Moore -- twelve days to find a court prepared to grant a retrial to hear new evidence." How completely wrong is this? Defense lawyer Fred Moore had officially withdrawn from the case three years before (and ceased acting for the defense the year before that) after Sacco refused to speak to him any longer. In 1927 Sacco and Vanzetti's defense was led by the prestigious William G. Thompson, widely regarded as Boston's top lawyer, a thoroughly Brahmin establishment figure who took Sacco and Vanzetti's case because the obvious flaws in their trial offended his sense of justice (and after the defense committee raised his healthy fee). And despite Bryson's snide comment, Fred Moore was never a "lone" anything. An active Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee raised funds first to hire both Moore (a California labor attorney) and a team of assistants. The Defense Committee later provided funds for Thompson and his assistants. No "lone, harried" defender, but a team of lawyers chased US Supreme Court justices around the county looking to convince a judge to hear their pleas for a new trial and save their clients' lives. The second, and even more unforgivable goof is Bryson's wholly inaccurate claim that highly regarded historian Paul Avrich, in his influential 1991 book "Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background," states that Sacco and Vanzetti were "almost certainly involved" in the Braintree robbery-murder. Bryson states (inaccurately): "In his 1991 book, historian Paul Avrich asked rhetorically whether Vanzetti could have been involved in the South Braintree holdup, and wrote: 'Though the evidence is far from satisfactory, the answer almost certainly is yes. The same holds true for Sacco.'" The actual quote (on page 150 in Avrich's book) is this: "Was Vanzetti himself involved in the conspiracy? Though the evidence is far from satisfactory, the answer almost certainly is yes. The same holds true for Sacco.'" The "conspiracy" Avrich refers to in this statement is not the Braintree holdup but a series of bombings (in 1918-19) widely attributed to anarchists. Anyone looking at the quote on the page will come to the same conclusion. The sentence that Bryson twists to his own purpose directly follows Avrich's lengthy account of how Italian anarchists turned to the use of bombs to strike back at the government officials and big capitalists that were persecuting them and, as they believed, oppressing the poor. That "conspiracy" included planting a bomb at the home of the US Attorney General, an act that precipitated massive arrests of immigrants and deportations and -- as many students of the case have argued -- the framing of known anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti for the Braintree crime. Those bombings (for whom no one was ever put on trial) and the Braintree shoe factory robbery-murder are entirely different cases. The only thing that puts the cases together is the state of Massachusetts' improbable theory that anarchists were responsible for the Braintree crime. Avrich may believe that Vanzetti and Sacco were "almost certainly" involved (in some unspecified way) in the Italian anarchist bombing conspiracy. He clearly does believe that they were members of the same network as the key anarchist figures he fingers as the principal conspirators (Carlo Valdinoci and Mario Budo). But when it comes to whether Sacco and Vanzetti bore any guilt for the Braintree crime, Avrich states explicitly that his book "makes no pretense of settling the issue of whether Sacco and Vanzetti were guilty of the crimes for which they were executed" (page 5). He states, instead, that the case against them "remains unproved... nor can their innocence be established beyond any shadow of doubt." It's hard for me to believe that an author of Bryson's stature could have bollixed this up so badly unless, perhaps, he was working from notes made by others. Nevertheless, the representation of a respected historian's judgment about one matter as his judgment on a distinctly different matter is not merely sloppiness, it's the kind of academic wrongdoing that would get your PhD thesis thrown out of court. In my opinion, it destroys Bryson's credibility as a commentator on the case.

Published on March 17, 2016 15:42

March 16, 2016

The Garden of Storytelling: Voices from the Snakish Past

OK, let's admit straight off that "The Man Who Spoke Snakish" By Andrus Kivirahk offers readers one of the strangest premises they are ever likely to come across, yet this book is wholly accessible, easy to read, and often humorous.

OK, let's admit straight off that "The Man Who Spoke Snakish" By Andrus Kivirahk offers readers one of the strangest premises they are ever likely to come across, yet this book is wholly accessible, easy to read, and often humorous. It's the mental leaps that require some energy, perhaps the old-fashioned "willing suspension of disbelief." But even these are presented charmingly -- talking snakes: the fount of all true wisdom; a cosmically gigantic "frog" waiting to bring the end of the world or the birth of a new cycle -- delivered with a kind of infinite withholding of an anticipated punch line that makes it easy to give up expecting some sort of 'rational' explanation. Once you get used to the wisdom of talking snakes, then you discover that the hero's mother was off having an affair with a bear... when, unhappily, they were discovered en flagrante by her husband who, unfortunately, startled the bear. Bears are really very gentle (so we are told) but get nervous when surprised, and on this occasion the bear reacted by biting the husband's head off. All a tragic misunderstanding.

If you think cohabbing with bears -- and talking to snakes -- is passing weird, wait till you meet the "hominids"... who keep a written record of all the changes in their paleo-history in wall markings on an endless cavern. But none of these extra-species connections make life difficult for people who live in the woods; it makes it easy. When you live in the primal forest of Estonia, all you really need to survive is a good command of snakish. Most of the beasts bow before the ancient authority of this tongue. So if you're hungry, a deer or a goat will come along, get the word, and offer his neck for the sacrifice. Estonian author Kivirahk offers us a pre-lapsarian universe. Nobody 'works.' No sweat of the brow. However, changes have come in the form of outlanders who cut down trees, build villages, plant fields, and sweat over their labor to earn their daily bread -- which they eat instead of the freely offered meat of the wild forest. They're also Christians. Kivirahk's book offers a kind of transvaluation of all values. We see the world from the perspective of the dying wilderness-dwellers whose values, skills, and way of life are being pushed to extinction by the new.The news way aren't better; they're demonstrably worse. But they're 'novel.' And the new, this book suggests, inevitably wins. While it's still obvious to our snakish-speaking narrator that his world is far superior -- freer, safer, more independent, in tune to what it is rather than the 'faith' some alien divinity wishes to create. How much easier, for example and 'natural,' to crawl into a nest of vipers to spend a winter warm and protected than fight the elements in a village hut by burning an acre of trees. What happens when new meets old is both sad, and funny, continually entertaining, and hard to sum up. It's a mythic story, worth pondering, like an old legend handed down from a people who not only talked to animals but regarded those could not as pathetically dense... A people who also knew what it was like to live at the end of the world.

Published on March 16, 2016 20:40

March 14, 2016

The Man Who Spoke Snakish by Andrus Kivirähk

OK, one of the strangest premises readers are ever likely to come across, yet this book is wholly accessible, easy to read, and often humorous. Once you get used to talking snakes, then you discover that the hero's mother was off having an affair with a bear... when, unhappily, they were discovered by her husband who startled the bear. Bears are really very gentle but get nervous when surprised, and on this occasion he reacted by biting the husband's head off. A tragic misunderstanding.

When you live in the forest of Estonia, all you really need to survive is a good command of snakish. Most of the beasts bow before the ancient authority of snakish. So if you're hungry, a deer or a goat will come along, get the word, and offer his neck for the sacrifice.

This is a kind pre-lapsarian universe. Nobody 'works.' No sweat of the brow.

But changes have come in the form of outlanders who cut down trees, build villages, plant fields, and sweat over their labor to earn their daily bread -- which they eat instead of the freely offered meat of the wild forest. They're also Christians.

Andrus Kivirahk's book offers a kind of transvaluation of all values. We see the world from the perspective of the dying wilderness-dwellers, whose values, skills, and way of life are being pushed to extinction by the new. While it's still obvious to our narrator that his world is far superior -- freer, safer, more independent, in tune to what it is rather than what some alien divinity wishes to create. Far easier, and more satisfying, to crawl into a nest of vipers to spend a winter warm and protected than fight the elements in a village hut by burning an acre of trees.

When you live in the forest of Estonia, all you really need to survive is a good command of snakish. Most of the beasts bow before the ancient authority of snakish. So if you're hungry, a deer or a goat will come along, get the word, and offer his neck for the sacrifice.

This is a kind pre-lapsarian universe. Nobody 'works.' No sweat of the brow.

But changes have come in the form of outlanders who cut down trees, build villages, plant fields, and sweat over their labor to earn their daily bread -- which they eat instead of the freely offered meat of the wild forest. They're also Christians.

Andrus Kivirahk's book offers a kind of transvaluation of all values. We see the world from the perspective of the dying wilderness-dwellers, whose values, skills, and way of life are being pushed to extinction by the new. While it's still obvious to our narrator that his world is far superior -- freer, safer, more independent, in tune to what it is rather than what some alien divinity wishes to create. Far easier, and more satisfying, to crawl into a nest of vipers to spend a winter warm and protected than fight the elements in a village hut by burning an acre of trees.

Published on March 14, 2016 20:19

•

Tags:

legends, literary-fiction, myths

The Garden of Story-telling: Tuesday Night at Plymouth Library

"Suosso's Lane" is not a courtroom novel, nor is it a straightforward dramatization of the factual record of Vanzetti's life in Plymouth. Why not -- a reasonable question -- simply stick to the facts? Historians do that, and they should.

"Suosso's Lane" is not a courtroom novel, nor is it a straightforward dramatization of the factual record of Vanzetti's life in Plymouth. Why not -- a reasonable question -- simply stick to the facts? Historians do that, and they should. But fiction is storytelling, and we need stories to give meaning to events. Stories are receptacles of meaning created by individuals and societies to interpret, advise, and make sense of the big mysteries and routine deeds of human experience. Folk tales, fairy tales, legends (emperors who want to cage the nightingale, kings who want the Midas touch), Greek myths, the book of Genesis in the Bible... We can all think of stories that matter to us.

Further, "Suosso's Lane" goes beyond historical fiction by developing a 21st century storyline based on reactions to the earlier events (Vanzetti in Plymouth), with characters forced to deal with some of the same deep social issues. The principals here are:-- Mill Becker, a young history teacher, who moves to Plymouth after being hired for his first real academic job at a nearby community college. Mill complains about his students and needs to develop a firmer grip on who he is, accept his limitations, and trust strengths. His fascination with, and desire to learn more about, Vanzetti drives the plot. -- His wife, Bernie Becker, a committed human services worker. Though more grounded than her husband, she has rescue fantasies about one of her clients (having fallen afoul of the law, he needs to be kept on the right path). Bernie has her own opinions; she asks Mill, 'Why were anarchists so against unions?'-- A second plot-driver -- here's a familiar character! your nosy local reporter (his working life, btw, is a lot more interesting than mine ever was), Maurice Jeter. He's investigating a real cold case, a 60-yr-old suspicious death of a Plymouth policeman. How can this death connect to the Sacco Vanzetti case? Well that's what fiction is for. -- Finally, Ike, the 'new immigrant' client Bernie seeks to help, works at a big box store (that I'm not allowed to call Wal-Mart). He finds parallels to V's story in his own life. He's in this novel because immigrants today do low-paying service job (they've replaced unskilled factory labor), as many of them as they can find to patch together an income, live in crowded conditions, save in order to send money home, or to bring loved ones over. Our response (judging from the tenor of our current politics) is to try to make things harder for them. So (quick plot wrap-up) Mill Becker is trying to find rumored documentary evidence, a letter or note of some sort, that would prove that Vanzetti could not have been at the scene of the Braintree crime that day (April 15, 1920). How well he does you'll have to read the book to find out.

Further, "Suosso's Lane" goes beyond historical fiction by developing a 21st century storyline based on reactions to the earlier events (Vanzetti in Plymouth), with characters forced to deal with some of the same deep social issues. The principals here are:-- Mill Becker, a young history teacher, who moves to Plymouth after being hired for his first real academic job at a nearby community college. Mill complains about his students and needs to develop a firmer grip on who he is, accept his limitations, and trust strengths. His fascination with, and desire to learn more about, Vanzetti drives the plot. -- His wife, Bernie Becker, a committed human services worker. Though more grounded than her husband, she has rescue fantasies about one of her clients (having fallen afoul of the law, he needs to be kept on the right path). Bernie has her own opinions; she asks Mill, 'Why were anarchists so against unions?'-- A second plot-driver -- here's a familiar character! your nosy local reporter (his working life, btw, is a lot more interesting than mine ever was), Maurice Jeter. He's investigating a real cold case, a 60-yr-old suspicious death of a Plymouth policeman. How can this death connect to the Sacco Vanzetti case? Well that's what fiction is for. -- Finally, Ike, the 'new immigrant' client Bernie seeks to help, works at a big box store (that I'm not allowed to call Wal-Mart). He finds parallels to V's story in his own life. He's in this novel because immigrants today do low-paying service job (they've replaced unskilled factory labor), as many of them as they can find to patch together an income, live in crowded conditions, save in order to send money home, or to bring loved ones over. Our response (judging from the tenor of our current politics) is to try to make things harder for them. So (quick plot wrap-up) Mill Becker is trying to find rumored documentary evidence, a letter or note of some sort, that would prove that Vanzetti could not have been at the scene of the Braintree crime that day (April 15, 1920). How well he does you'll have to read the book to find out. Tuesday night I'll be talking about and reading excerpts from "Suosso's Lane" at Plymouth Public Library, starting at 7 p.m.

Published on March 14, 2016 15:05

March 13, 2016

Spring's Garden of Anticipation: Return!

March is the month of returns. The biggest of all -- hard in fact to imagine anything bigger -- is the return of the sun to the northern hemisphere. That takes place next week and marks the beginning of the long-awaited season of spring. Le "printemps," in French, or 'the first of times.'

In most ways that matter spring is the beginning of the new year. The soil will warm up, the sun will dry up wet fields so farmers can plant once again. Only if the farmers can plant, and the sun makes the crops grow, will there be food for another year so that life for all creatures who depend on earth's bounty (especially us) can go on.

On a humbler, less survivalist note, the return of the sun also stirs the little flower gardens back to life as well. Last week we saw white and yellow, pink and violet crocuses popping up.

On a humbler, less survivalist note, the return of the sun also stirs the little flower gardens back to life as well. Last week we saw white and yellow, pink and violet crocuses popping up. However, in some spots many fewer than planted, with clear signs of squirrel predation. I put in dozens of new bulbs last fall and tried to cover my tracks, but our latest generation of squirrel pests -- I call them 'the barbarian horde' -- found and ate (or at least relocated) about 90 percent of the crocuses.

I could use some lessons in squirrel deterrence. If anyone has any ideas, please let me know.

Nevertheless the return of those cheerful, brightly colored mugs smiling up at us on sunny mornings is greatly fortifying. And the purple flowers of the Vinca minor are also fast spreading in both front and back gardens. Everywhere else the greening has begun in what fast becomes a garden of anticipation. Color, once begun, will expand geometrically now every week or two.

The middle of March, with spring on the near horizon, also means it's time to move the clock forward. I failed to anticipate this moment with my own wristwatch and so was living in the past for several hours this morning.

Speaking of returns, I'm back too, having lost the entire first half of this month to an extended recuperation period after a surgery to remove my gall bladder proved much more complicated than anyone anticipated.

Finally, "return" is also the theme for poems in the March issue of Verse-Virtual, the online poetry journal that draws more than 25,000 page views each month.

I have three poems in the issue, a group I titled "Three Dream Poems on the Theme of Return."

One of these, as its title "Return (ii): The Sun," suggests, is about the changes we see in March. It begins.

He finds the yellow ball in his backyard

And takes it to the sea.

The others are eating cornflakes.

They're shining bicycles.

Flutes and brass gleam in the sun.

The summits are brazen, glowing from their daily polish,

sparkle and dew,

a sheen in the night, silent as ice-fall at daybreak.

...

(For this poem and so many others, see verse-virtual.com and click on 'current poetry.')

Published on March 13, 2016 20:01

March 9, 2016

The Garden of Sickness and Health: The Uses of Maladies

At least, people say, we have our health. Don't take it for granted. Oh, I don't. Don't worry about the little things, we tell each other.The big things? Start with health. Oh, yes, nothing can be more important than that! And if you are healthy, be sure to appreciate your good fortune. But how to appreciate it?

At least, people say, we have our health. Don't take it for granted. Oh, I don't. Don't worry about the little things, we tell each other.The big things? Start with health. Oh, yes, nothing can be more important than that! And if you are healthy, be sure to appreciate your good fortune. But how to appreciate it? One answer to the latter question at least, I think, is by leaving it for a while. If we're fortunate our stay out of health, as opposed to in health, is only a brief one. But when that occasional absence-of-health experience comes around, I think we should recognize a learning experience when we see one. When you're sick, or recovering from a cure, a lot of ordinary defences are stripped away. You have a bad night. You cannot sleep, and lie awake looking at the ceiling and the lights in the world outside a hospital window, the IV trolley, the door of the bathroom you prefer to think you will not need. You have looked at these objects for hours, and they have nothing more to tell you. You cannot ring for the nurse to bring you something, because there is nothing at this point you are permitted to have. Perhaps the breathing tube is still up your nose, so you cannot wipe the area successfully when it begins to run. You have slept already once, earlier this evening, but then someone woke you to take your vital signs and make sure you are all right. 'I was all right when I was sleeping,' you think, 'but I am not "all right" now. I am awake and perfectly miserable.' Hospitals put limits on sleep. An hour; perhaps an hour and a half. You conclude, after much high-minded philosophical reasoning (and nothing else to think about), that human life without sleep is insupportable. Some time later, a few days, a week, maybe even longer, you realize that such nights are common, maybe even routine, for many people for long periods of time. Maybe all the time. You will go home in a few days, recuperate with some more bed rest in your own bed, resume your life. Many others are not so fortunate. Perhaps "health" doesn't always snap back; it's like an elastic stretched too far. Other bad nights, here there and everywhere, have other causes. Refugees sleep in the rain, holding their place at night in the endless queue that spirals out from the killing counties to the barbed wire and newly closed doors of Europe. Even in his own city, men and women sleep in doorways and parked cars. Perhaps sleeping in the back seat of an old car provides more interesting vistas than looking out of a hospital window, but he doubts it. How do we learn compassion? Does it come from our own illnesses with the concurrent bad nights and troubled thoughts? This is hardly a new idea. To be humbled by the flesh is a teachable moment. Old man Lear cast out on the heath on a stormy night discovers for a companion the poor mad beggar Tom. Poor wretch, the old king thinks, how many such others groan this cruel night?

"O! [Lear moans] I have ta'en too little care of this..."

No one chooses illness, the loss of physical comfort. But if it comes you try to learn something from it.

Published on March 09, 2016 19:27

The Garden of Sickness and Health: The Uses of Maldies

At least, people say, we have our health. Don't take it for granted. Oh, I don't. Don't worry about the little things, we tell each other.The big things? Start with health. Oh, yes, nothing can be more important than that! And if you are healthy, be sure to appreciate your good fortune. But how to appreciate it?

At least, people say, we have our health. Don't take it for granted. Oh, I don't. Don't worry about the little things, we tell each other.The big things? Start with health. Oh, yes, nothing can be more important than that! And if you are healthy, be sure to appreciate your good fortune. But how to appreciate it? One answer to the latter question at least, I think, is by leaving it for a while. If we're fortunate our stay out of health, as opposed to in health, is only a brief one. But when that occasional absence-of-health experience comes around, I think we should recognize a learning experience when we see one. When you're sick, or recovering from a cure, a lot of ordinary defences are stripped away. You have a bad night. You cannot sleep, and lie awake looking at the ceiling and the lights in the world outside a hospital window, the IV trolley, the door of the bathroom you prefer to think you will not need. You have looked at these objects for hours, and they have nothing more to tell you. You cannot ring for the nurse to bring you something, because there is nothing at this point you are permitted to have. Perhaps the breathing tube is still up your nose, so you cannot wipe the area successfully when it begins to run. You have slept already once, earlier this evening, but then someone woke you to take your vital signs and make sure you are all right. 'I was all right when I was sleeping,' you think, 'but I am not "all right" now. I am awake and perfectly miserable.' Hospitals put limits on sleep. An hour; perhaps an hour and a half. You conclude, after much high-minded philosophical reasoning (and nothing else to think about), that human life without sleep is insupportable. Some time later, a few days, a week, maybe even longer, you realize that such nights are common, maybe even routine, for many people for long periods of time. Maybe all the time. You will go home in a few days, recuperate with some more bed rest in your own bed, resume your life. Many others are not so fortunate. Perhaps "health" doesn't always snap back; it's like an elastic stretched too far. Other bad nights, here there and everywhere, have other causes. Refugees sleep in the rain, holding their place at night in the endless queue that spirals out from the killing counties to the barbed wire and newly closed doors of Europe. Even in his own city, men and women sleep in doorways and parked cars. Perhaps sleeping in the back seat of an old car provides more interesting vistas than looking out of a hospital window, but he doubts it. How do we learn compassion? Does it come from our own illnesses with the concurrent bad nights and troubled thoughts? This is hardly a new idea. To be humbled by the flesh is a teachable moment. Old man Lear cast out on the heath on a stormy night discovers for a companion the poor mad beggar Tom. Poor wretch, the old king thinks, how many such others groan this cruel night?

"O! [Lear moans] I have ta'en too little care of this..."

No one chooses illness, the loss of physical comfort. But if it comes you try to learn something from it.

Published on March 09, 2016 19:27

February 25, 2016

The Garden of the Trees: The Hawk About Town

Red-tailed hawks are the consensus pick for "most common hawk in North America" and are found throughout the country. I'm pretty sure they're common in Quincy, Massachusetts, because that's the kind of hawk I keep running into in the green places where I walk near the ocean.

Red-tailed hawks are the consensus pick for "most common hawk in North America" and are found throughout the country. I'm pretty sure they're common in Quincy, Massachusetts, because that's the kind of hawk I keep running into in the green places where I walk near the ocean. Red-tailed hawks are large hawks with what one authoritatively titled source ("All About Birds") calls "typical Buteo proportions: very broad, rounded wings and a short, wide tail."

They make a bulky presence perched on a leafless branch in winter, particularly the 'wide' lower half, that strikes me as one of the bulkier proportions on a creature that aspires to fly under its own power. In fact, red-tailed hawks fly like the wind. All About Birds comments: "Large females seen from a distance might fool you into thinking you’re seeing an eagle. (Until an actual eagle comes along.)"

I've never seen an eagle in Quincy, but lately I've been seeing either a lot of red-tailed hawks or a lot of the same red-tailed hawk. Last week on a sunny day pretending to be early spring, though the city-owned salt marsh near Wollaston Beach where someone laid out a snug nature trail right along the border of a hummock with trees rising above the winter-flattened Spartina grass of the marsh. The path was still sodden from the melt-off of snow that fell earlier this month, so I was picking my spots for each footfall.

I've never seen an eagle in Quincy, but lately I've been seeing either a lot of red-tailed hawks or a lot of the same red-tailed hawk. Last week on a sunny day pretending to be early spring, though the city-owned salt marsh near Wollaston Beach where someone laid out a snug nature trail right along the border of a hummock with trees rising above the winter-flattened Spartina grass of the marsh. The path was still sodden from the melt-off of snow that fell earlier this month, so I was picking my spots for each footfall. Coming around a slight bend where the footing was passable and a new perspective afforded every couple dozen feet, I looked up and spotted a large presence amid the branches of the bordering trees (top photo). It was good perch for keeping an eye on the open landscape of the marsh. I suspected, having had similar experiences before, that whatever was sitting in that tree would be worth looking at it, but the hawks and other large birds who choose to spend time in these outposts don't necessarily wait around for your inspection.

This one did. He let me walk up to his perch and photograph him as much as I pleased. I passed directly under the branch where he sat viewing the world about 20 feet above me, then turned around and took his picture from the other side. The hawk appeared content with the entirely correct notion that I was not about to climb a tree 20 feet up to disturb him and that whatever object I was holding up in his direction could not hurt him. I was tempted to start a conversation.

Two days later on an even brighter day, I visited another 'nature spot' a mile or two northward along the coast where the landscape was also still drying out from the same snow melt and was, if anything, even a little wetter. That same impression of something in the middle distance at the edge of the trees greeted me as soon as I stepped out of my car on the shore side of expansive and almost entirely empty (as always) apron of pavement that serves as parking for Squantum Point Park.

The walking trail was drawing as many visitors as I've ever encountered there. The park is mostly used by residents of the bordering Marina Bay development to walk their dogs. So it was that afternoon. People were walking their dogs. A few dogs appeared to be walking themselves. Some dogs were permitted off leash. Dog walkers encounter other dog walkers and talk about their dogs. Otherwise, little birds flutter and scatter through the thickets, not much concerned about dogs. Wading birds, however, keep their distance. I see heron flying overhead on some occasions, but they don't land near this trail.

No one, to my surprise, lifted their eyes to the trees and stopped to look at the hawk. No one, as far as I could tell, lifted their eyes once from the earthbound drama of dogs and mud or showed any sign of registering so palpable a presence as a hawk sometimes confused with an eagle.

Nor did anyone pay any attention to my fumbling efforts to photograph the big bird. It took me forever to get a decent shot because in direct sunlight that bright the viewfinder of my camera turns into a mirror. I tried shading it with one hand, fumbled, aimed the camera randomly, while the hawk permitted me to pay court beneath him about twenty-five feet off as long as I wanted. I finally walked about 180 degrees around the copse to get the bulk of my body between direct sunlight and a hawk perched on his branch to get a clear image in the viewfinder and snap a shot.

The image greatly reminded me of the hawk I had snapped a couple days before. The color differences in the two images you see here (the first one in the salt marsh; the second in Squantum Point Park) are illusory; the product of different light, different skies, different angles.

I'm concluding this hawk gets around, though so far he has shown affinity for Quincy. That must be why we keep running into each other.

I'm also posting a few others I took of the bay and the Boston skyline under a dazzling sky.

Published on February 25, 2016 14:25

February 20, 2016

The Garden of History: The Whole World Knew Their Name

From "Trial of the Century: Local Amnesia" (published in 2002 in Beyond Plymouth Rock):

"Plymouth has always been ambivalent about Vanzetti, arguably the central figure in one of the most famous criminal trials of the 20th century. By the end of the 20th century even long-time Plymouth residents had largely forgotten that he lived here among us, at 35 Cherry St. when he was arrested on a Brockton streetcar in 1920. But for many years the name of Vanzetti was known throughout the world. People who had never heard of John Alden, Gov. Bradford or Myles Sandish, or who may not have known much else about America in the 1920s nevertheless knew who Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were -- the workers who were framed and executed for their opposition to capitalism."

When I came across the surprising information that Bartolomeo Vanzetti had lived in Plymouth, Massachusetts, home of the Pilgrims and the first real community of English speakers in what became the United States, the first place I went to learn more was Plymouth Public Library. This was so long ago that the library was still on North Street. We could walk to it, and did, from our house up on a hill over Plymouth Harbor. Everything in Plymouth Center was historic. The plaque on the corner of our street named, not coincidentally, Massasoit Street and Mayflower Street stated that this was the place the first embassy from the Wampanoag Indian sachem Massasoit met with Pilgrim representatives led by Edward Winslow. The Pilgrim colony was fortunate to have Winslow, a natural diplomat, in its company.

When I came across the surprising information that Bartolomeo Vanzetti had lived in Plymouth, Massachusetts, home of the Pilgrims and the first real community of English speakers in what became the United States, the first place I went to learn more was Plymouth Public Library. This was so long ago that the library was still on North Street. We could walk to it, and did, from our house up on a hill over Plymouth Harbor. Everything in Plymouth Center was historic. The plaque on the corner of our street named, not coincidentally, Massasoit Street and Mayflower Street stated that this was the place the first embassy from the Wampanoag Indian sachem Massasoit met with Pilgrim representatives led by Edward Winslow. The Pilgrim colony was fortunate to have Winslow, a natural diplomat, in its company. But living on a corner where something from the history books took place is not unusual in Plymouth. Plaques and statues abound. A couple of blocks toward the harbor, on the way to the library on North Street, lay the park built along Town Brook. Town Brook was the fresh water source the Mayflower colonists were desperate to find before they would leave the ship (in whatever weakened state) and put up stakes.

So maybe when you have history to burn it's not surprising the town could forget about the early 20th century residency of one of the most well known names, worldwide, of his era, the seven years from the arrest to the execution (1920-1927) of Vanzetti and his anarchist comrade Sacco, like him an Italian immigrant and a believer that the widespread social injustice and poverty faced by masses of human beings in America, as in Italy, would not be overcome until the world turned to the path they termed "the beautiful idea."

However, while there is no public, physical acknowledgment of Vanzetti's presence anywhere in the town, Plymouth library knew about him (as it knows about most things). Reference Librarian Lee Regan, for whom local history was a passion, took me upstairs to the "local history room" and showed me the shelf where she kept books specifically related to the Sacco-Vanzetti case. I found more than enough there, notably the mammoth Francis Russell history of the case, titled "Tragedy in Dedham," to get me started.

I was familiar with the general outline of the story, the way someone with an interest in radical American politics is likely to know the headlines of the story -- two immigrants of suspect political beliefs nabbed for an outrageous daylight robbery and murder, and convicted because of the prevailing societal prejudice against everything these men appeared to represent, rather than on any solid evidence. I am being sentenced, Vanzetti said (to paraphrase his remarks to the court before sentencing), not for the case brought against me, but because I am an Italian and because I am a radical.

Yet the more details I learned about the case, about Vanzetti's life, and about the world he and millions of working class laborers and their families inhabited, it seemed to me that the story of a man whose name was known to everyone in the world 90 years ago, but whose story was ignored in the town he lived in, still has much to tell us.

Both about the way things were back the, and -- remarkably, unhappily -- about the way some things still are.

The excerpt below is from my novel "Suosso's Lane":

Late in the evening of August third, waiting until almost midnight so that reporters hovering all day outside his door would have no time to gather reaction to his decision, Governor Fuller released the report of the commission affirming the conduct of the court and the verdict of the jury. He set an execution date for two weeks away. The newspapers reported the decision with a two-word headline: "They Die!" Two words were all that were needed. Everybody in the world able to read a newspaper knew who "they" were. (Suosso's Lane available at www.web-e-books.com/index.php#load?ty...)

Published on February 20, 2016 21:17