Robert Knox's Blog, page 33

February 5, 2017

Garden of Verse: New Poems from Plymouth Author: Driving With the Right Side of the Brain

https://www.amazon.com/Driving-Right-...

Dolores Stewart Riccio, Plymouth-based poet and author of a series of clever mysteries by a circle of psychic friends, has published a new collection of her poems titled "Driving with the Right Side of the Brain." The book begins with the classic lament of the mature poet: "not enough time." Citing a quotation from Ralph Waldo Emerson on the task of the creative imagination ("My books should smell of the pines and resound with the hum of the insects"), Riccio's poem is titled "What Shall We Do About This Abundance?" It begins: There simply isn't enough time to get around to all the inviting beach roses, simmering with silk and scent.

Speaking as someone who has long appreciated the company of beach roses, I say what a marvelous image: "simmering with silk and scent." All those soft 's' sounds really do simmer. Silk strikes me as exactly right for the consistency of that special breed of rose, and 'scent' is the first sign of their presence when you near a New England shoreline. This poem concludes with an observation, "Before we are ready, the end of summer comes," both true and resonant. Because this is always the way of things, isn't it? Because, yes, summer comes to an end before we have figured out "what to do" with any of it. And by now we also realize that we are not merely speaking of summer. All of this imaginative, philosophical punch packed into the first page of a book of 104 pages of similarly reflective, delightful and affecting poetry. Riccio is a member of an ongoing poetry group sponsored by the Duxbury Library. The library's director, Carol Jankowski, sums up "Driving with the Right Side of the Brain" this way:

In her new anthology of poems, Dolores Stewart Riccio invites curiosity, memory, love, mystery, pageantry, and history to attend a celebration of soul! Each poem speaks directly to the reader; each lovely image appears in the mind’s eye and heart as brilliantly as a celestial panorama. The anthology is divided into eight sections, with topics ranging from Reincarnation to Shapeshifter and Acts of Faith. In the poem “Driving with the Right Side of the Brain,” the poet exclaims, “some daredevil soul records with a flourish of a pen adventures I never remember.” Trust me, daredevil souls: readers will lovingly remember the adventures that come alive in this poetry!

Ellen Jane Powers, author of a poetry collection titled "Celestial Navigations," writes of Riccio's book: "At times we feel we're overhearing a private rumination, then we come across an 'old spell' or charm to carry us onward. Her language is at once philosophical and witty, giving power to the underdog and dame alike." Having received a review copy of her new book , I wrote a brief review as well: Dolores Stewart Riccio's sure-handed lyrics, ranging from delicate to pointed, show us Shakespeare at the senior center, Greek mythology in the publisher's office, a Lakota legend on the power of youthful desire, quiet testimonies to the mystery of an undying love. She sees the legendary in the everyday as well, a grieving old man merging into his garden, mountains whirling just out of sight, rivers of sky only a bird can navigate. Her volume of new and selected poems is a book of marvels, some of them the everyday kind like listening to opera while driving to the post office, a cache of unexpected words for death ("the professor of fates and balances"), some of them acts of faith such as "Negative Birthday Candles." These poems provide a fitting response to the epistemological teaser "Do you believe you are breathing?" Dolores Stewart Riccio's answer: "I do not believe, I know."

You can find more information about the author's series of novels, known as the The Divine Circle of Ladies mysteries, at her website: http://www.doloresstewartriccio.com/w... These clever and entertaining ladies are a little more inclined to magic and witchcraft than to the writing of verse. But magic is a kind of poetry as well.

Published on February 05, 2017 12:17

January 29, 2017

The Garden of History: "We must grow greater or we grow less"

In these Orwellian times, when a senior adviser to the office of President offers the notion of "alternative facts" to defend an absurdity issued from the big mouth of our new fuhrer, I came across a statement by the author of 1984 and Animal Farm. George Orwell was speaking about his own country, England, but I think the point applies to this country as well:

In these Orwellian times, when a senior adviser to the office of President offers the notion of "alternative facts" to defend an absurdity issued from the big mouth of our new fuhrer, I came across a statement by the author of 1984 and Animal Farm. George Orwell was speaking about his own country, England, but I think the point applies to this country as well:

"Nothing ever stands still. We must add to our heritage or lose it, we must grow greater or we grow less, we must go forward or backward...." Orwell's words were quoted by Robert Tombs near the end of his recent ambitious study of his country's evolution, titled "The English and Their History." Here is Tombs's own picturesque and concise description of his country: "England is a rambling old property with ancient foundations, a large Victorian extension, a 1960s garage, and some annoying leaks and draughts balancing its period charm." This fine portrayal caused me to wonder how would we might describe the United States in real estate terms. How about: "Big House USA is a McMansion built with low-paid immigrant labor on a vast, environmentally-degraded but world-renowned property, offering separate bedrooms for all the members of its blended soap-opera family who don't get along." Various historians (to go back to "The English and Their History") contend that England is the prototype of the nation-state. If this is the case, Tombs asks, why has the English nation lasted so long while retaining a sense of its own peculiar "identity"? He then quotes a kind of minority report from 18th century philosopher and historian David Hume, who stated that England's long endurance and remarkable stability is the result of "a great measure of accident with a small ingredient of wisdom and foresight." In the concluding chapter of his 900-page book, historian Robert Tomb returns to questions he has asked in examining his country's state of the nation through the centuries. What makes England different, enduring, itself? Tombs cites the nation's particular geographical situation -- not its island separation alone, but an island situated close by the influence of a large continent. He recalls Charles deGaulle's conclusion that England should not be part of the Common Market because it would never cling to Europe but continue to spread its greedy fingerprints all over the world. The island nation's watery separation from the continent did not keep it safe from outside influences: the Romans, the Anglo-Saxons, the Vikings, and the Normans all successfully invaded. In an earlier millennium, the Celts arrived there from the continent. The island was Albion (or Alba) to the Greeks and Romans before it was Briton (in a variety of spellings and languages). It wasn't until the 800s that the name "Engelond" came into use. Norman conquest and expansion, Tombs writes, wrapped Wales, Ireland and (often) Scotland into union with the more populous and dominant Anglo-Saxon nation,but fear of invasion and the constant need for homeland defense was central to the resulting nation-state's development. Tombs notes this interesting consequence: "a prominent part of being English has been paying a lot of tax." (Note: An incredible wealth of national statistical information underpins the conclusions of this book.) Both the need for security and the desire for trade kept England interested in and involved with its neighbors. An obsession and rivalry with France is a millennium-long piece of its identity. England was slower than some of its seafaring neighbors to explore the world beyond its Atlantic neighbors. The Vikings sailed further abroad, visiting some parts of the globe centuries before the English did. Tombs contends that Great Britain's empire, its acquisition of colonies in far-flung regions was a result of its rivalry with and fear of the larger, impinging continental nation (and sometimes empire) of France. Trade, defense, and international insecurity turned the English into a seafaring nation that put is faith in a navy rather than an army. The two-century long British Empire did some good, Tombs contends. Its global reach suppressed continental wars (Tombs calls them 'world wars,' given European rivalries in both the America and Asia in addition to Europe) from the end of Napoleonic era to World War I and achieved some social gains such as the eventual end of the African slave trade. This early era of globalization also exported the English language and some beneficial institutions such as trial by jury, parliament and "sport." Imperial dominance and European peace allowed the industrial revolution to get rolling. But Tombs suggests the British Empire may have contributed to the two world wars because in some respects they were wars fought against the British empire. He considers the complicated question of the ways in which the names England and Britain are used interchangeably and the ways they cannot be. 'England' has warmer connotations. You cannot say, "Oh to be in Britain/ Now that April's here" or "in the UK's green and pleasant land." He also identifies the phenomenon of "Euroscepticism" in a book written before the Brexit vote. And he quotes Orwell again when considering the real, personal significance a nation's history has for its members. Orwell: "that it is your civilization , it is you... the suet puddings and red pillar boxes have entered into your soul." Other identifying English traits? Tombs cites "a pervasive social awkwardness alternatively displayed in politeness, rudeness and a characteristic time of humour." And how about that extra 'u'? -- borrowed centuries ago from the French. Tombs' habit throughout his 900-page study is to discuss a negative critique of the country, and then measure the same negative comparatively with other countries. Here, at his book's end, he cites England's long history of domestic peace compared to the body counts in countries such as France, Russia and China. He does not even bring up the American Civil War. Over the centuries, he writes, England has been "among the richest, safest and best governed places on earth." In an allusion to institutions such as trial by jury and local government he cites Edmund Burke's praise for "the wisdom of unlettered men." The book's last argument is for the value of the study of history itself. History, like travel, "broadens the mind." And in a return to the kind of architectural metaphors we began with, and a bow to his own study's heft, he calls his book "a brick for our common house." However well built, or ill, you find that house, this brick is worth hefting.

"Nothing ever stands still. We must add to our heritage or lose it, we must grow greater or we grow less, we must go forward or backward...." Orwell's words were quoted by Robert Tombs near the end of his recent ambitious study of his country's evolution, titled "The English and Their History." Here is Tombs's own picturesque and concise description of his country: "England is a rambling old property with ancient foundations, a large Victorian extension, a 1960s garage, and some annoying leaks and draughts balancing its period charm." This fine portrayal caused me to wonder how would we might describe the United States in real estate terms. How about: "Big House USA is a McMansion built with low-paid immigrant labor on a vast, environmentally-degraded but world-renowned property, offering separate bedrooms for all the members of its blended soap-opera family who don't get along." Various historians (to go back to "The English and Their History") contend that England is the prototype of the nation-state. If this is the case, Tombs asks, why has the English nation lasted so long while retaining a sense of its own peculiar "identity"? He then quotes a kind of minority report from 18th century philosopher and historian David Hume, who stated that England's long endurance and remarkable stability is the result of "a great measure of accident with a small ingredient of wisdom and foresight." In the concluding chapter of his 900-page book, historian Robert Tomb returns to questions he has asked in examining his country's state of the nation through the centuries. What makes England different, enduring, itself? Tombs cites the nation's particular geographical situation -- not its island separation alone, but an island situated close by the influence of a large continent. He recalls Charles deGaulle's conclusion that England should not be part of the Common Market because it would never cling to Europe but continue to spread its greedy fingerprints all over the world. The island nation's watery separation from the continent did not keep it safe from outside influences: the Romans, the Anglo-Saxons, the Vikings, and the Normans all successfully invaded. In an earlier millennium, the Celts arrived there from the continent. The island was Albion (or Alba) to the Greeks and Romans before it was Briton (in a variety of spellings and languages). It wasn't until the 800s that the name "Engelond" came into use. Norman conquest and expansion, Tombs writes, wrapped Wales, Ireland and (often) Scotland into union with the more populous and dominant Anglo-Saxon nation,but fear of invasion and the constant need for homeland defense was central to the resulting nation-state's development. Tombs notes this interesting consequence: "a prominent part of being English has been paying a lot of tax." (Note: An incredible wealth of national statistical information underpins the conclusions of this book.) Both the need for security and the desire for trade kept England interested in and involved with its neighbors. An obsession and rivalry with France is a millennium-long piece of its identity. England was slower than some of its seafaring neighbors to explore the world beyond its Atlantic neighbors. The Vikings sailed further abroad, visiting some parts of the globe centuries before the English did. Tombs contends that Great Britain's empire, its acquisition of colonies in far-flung regions was a result of its rivalry with and fear of the larger, impinging continental nation (and sometimes empire) of France. Trade, defense, and international insecurity turned the English into a seafaring nation that put is faith in a navy rather than an army. The two-century long British Empire did some good, Tombs contends. Its global reach suppressed continental wars (Tombs calls them 'world wars,' given European rivalries in both the America and Asia in addition to Europe) from the end of Napoleonic era to World War I and achieved some social gains such as the eventual end of the African slave trade. This early era of globalization also exported the English language and some beneficial institutions such as trial by jury, parliament and "sport." Imperial dominance and European peace allowed the industrial revolution to get rolling. But Tombs suggests the British Empire may have contributed to the two world wars because in some respects they were wars fought against the British empire. He considers the complicated question of the ways in which the names England and Britain are used interchangeably and the ways they cannot be. 'England' has warmer connotations. You cannot say, "Oh to be in Britain/ Now that April's here" or "in the UK's green and pleasant land." He also identifies the phenomenon of "Euroscepticism" in a book written before the Brexit vote. And he quotes Orwell again when considering the real, personal significance a nation's history has for its members. Orwell: "that it is your civilization , it is you... the suet puddings and red pillar boxes have entered into your soul." Other identifying English traits? Tombs cites "a pervasive social awkwardness alternatively displayed in politeness, rudeness and a characteristic time of humour." And how about that extra 'u'? -- borrowed centuries ago from the French. Tombs' habit throughout his 900-page study is to discuss a negative critique of the country, and then measure the same negative comparatively with other countries. Here, at his book's end, he cites England's long history of domestic peace compared to the body counts in countries such as France, Russia and China. He does not even bring up the American Civil War. Over the centuries, he writes, England has been "among the richest, safest and best governed places on earth." In an allusion to institutions such as trial by jury and local government he cites Edmund Burke's praise for "the wisdom of unlettered men." The book's last argument is for the value of the study of history itself. History, like travel, "broadens the mind." And in a return to the kind of architectural metaphors we began with, and a bow to his own study's heft, he calls his book "a brick for our common house." However well built, or ill, you find that house, this brick is worth hefting.

Published on January 29, 2017 17:36

January 25, 2017

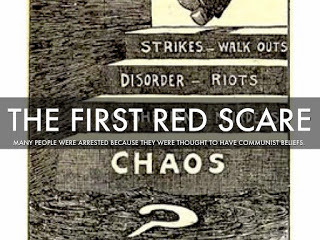

The Garden of History: What We Can Learn From the Political Panic of 1920

If you wanted to build a wall a hundred years ago, it would have had to be on the Atlantic.

If you wanted to build a wall a hundred years ago, it would have had to be on the Atlantic. I'll be speaking on my novel "Suosso's Lane" at Duxbury Library on Sunday, Jan. 29, 2 p.m., my first opportunity following the inauguration of a new administration to address the potential lessons for our own time from the notorious Sacco and Vanzetti case, in which two Italian immigrants were convicted of murder in 1920 after a biased trial offering absurdly thin evidence of their guilt. Comparisons between where we are today and the state of American society and politics a hundred years ago give me a thematic subtitle for Sunday's talk: "Sacco and Vanzetti, Democratic Stress Tests, and Dangerous Times." I believe there are lessons for our own time from a consideration of the social, political an economic conditions that form the background for the Sacco-Vanzetti, in which (from the evidence we do have) it appears that prosecutors invented a theory for who committed a payroll robbery and killed two officials that fit nicely into contemporary hysterical fantasies about the dangers posed to the nation by -- in 1920 -- foreign anarchists. And then picked out two "perpetrators" who fit the bill and went about inventing case against them that relied on current-day prejudices to win a conviction from a jury already persuaded that foreign radicals were capable of any horrendous crime you could imagine. Where did these dangerous foreigners come from? The other side of the Atlantic. Largely from southern and eastern Europe. More from Italy than anywhere else. Comparisons between that time and our own seem especially worth examining now that we are a week into a new administration that plans to build a border wall, reduce legal immigration and otherwise turn its back on traditional American democratic and egalitarian values, much like the period in which Sacco and Vanzetti were executed because of their beliefs and their ethnicity. A time of "us" and "them." One of those times, Sacco and Vanzetti's time, was called the "Red Scare." Every historical source that discusses Sacco-Vanzetti mentions the "Red Scare" as the essential piece of background to understand the famous case. In his book "Sacco and Vanzetti: the Anarchist Background," historian Paul Avrich writes, "The trial, occurring in the wake of the Red Scare took place in an atmosphere of intense hostility towards the defendants." My one-sentence definition is the Red Scare was period of social unrest and hard times set ablaze by anarchist bombings that led in turn to a massive, extra-legal crackdown on 'radical' immigrants and deportations in 1919-20. Some historians cast a wider net. Defining the Red Scare as a fear of communism, one source notes that the estimated of 150,000 anarchists or communists in USA in 1920 represents merely 0.1% of the country's overall population. Yet, this source points out, many Americans were easily spooked by fear of revolutionary ideas because of the successful communist takeover of Russia in 1917 and the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901 by a homegrown anarchist, Leon Czolgosz. Others emphasize major economic dislocations following the end of World War I, especially high unemployment and a rash of major strikes. Leo Robert Klein of City University of New York dates the Red Scare from the Armistice in November of 1918 to the collapse of hyper-inflation in mid-1920. During this period the "social and economic stresses" on American society, arriving almost concurrently, include "a deadly flu epidemic, a strike wave of unparalleled proportions, harsh suppression in some cases of those strikes, race riots, hyper-inflation, mass round-ups and deportations of foreign born citizens, expulsion of duly-elected officials from various offices in government, an incapacitated president, espionage laws, sedition laws and, of course, the advent of Prohibition and women's suffrage." These sudden blows and social dislocations led an exaggerated fear of threats posed to American stability and institutions from left-wing radicals. A more detailed analysis of the Red Scare offered by Paul Burnett on the website of the University of Missouri at Kansas City also discusses the Red Scare as the essential background for the Sacco-Vanzetti case.

[http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects...]

Burnett points to major strikes taking place at the end of World War I that rattled the economic status quo and the economic elite. These strikes led to alarmist political fears spread by government officials and sensationally publicized by what we now call the media. Some facts about events that none of us learned in our high school American history classes: At the end of World War I 9 million workers in war industries and 4 million soldiers faced unemployment in a suddenly declining job market. Freed from wartime restrictions two powerful left-wing movements rocked this boat: the IWW (International Workers of the World, or Wobblies) led a general strike in Seattle that brought out 60,000 workers. And Socialist Part candidate Eugene Debs received almost 1 million votes for President. Other strikes followed, including the famous Boston police strike and a national steel workers strike carried out by 365,000 workers. Negative publicity and scare tactics led to a right-wing reaction that "demonized" all strikes as crimes against society, Burnett writes. Strikers were called "reds," regardless of what their political views might be. As the fear of strikes leading to a Communist revolution spread throughout the country, hysteria took hold and "red hunting" became the national obsession. Colleges were deemed to be hotbeds of Bolshevism, and professors were labeled as radicals. If the last part sounds familiar, it's because the McCarthyism of the post-WW II era recycled the same obsessions. The Red Scare brought widespread attacks on civil liberties. The General Intelligence Division of Bureau of Investigation (soon to become the FBI) with J. Edgar Hoover as its head was created to uncover Bolshevik conspiracies, and to find and incarcerate or deport conspirators. The myth of internal subversion is essential to the FBI; it's the root mission. It must find some, or invent some -- ask MLK -- to stay in business. Eventually, the new anti-radical agency compiled over 200,000 cards in a card-filing system that detailed radical organizations, individuals, and case histories across the country. Does this sound familiar in the era of the NSA?

These early efforts resulted in the imprisonment or deportation of thousands of "supposed radicals and leftists," Burnett states. "These arrests were often made at the expense of civil liberties as arrests were often made without warrants and for spurious reasons." On January 2, 1920 alone over 4,000 alleged radicals were arrested in thirty-three cities (800 in Boston). Legislatures also reflected the national sentiment against radicals.... As the anti-Red hysteria spread, the New York State Legislature expelled five duly elected Socialist assemblymen from its ranks. According to Burnett,

the national mood returned to "normal" in 1920, as courts and other investigators detailed the Justice Department's violations of civil liberties in its treatment of supposed radicals, especially foreign nationals. But by then the Red Scare, and demonization of foreign-born critics of the American status quo had left its mark on the nation's psyche.

When the state of Massachusetts offered Sacco and Vanzetti, the Italian anarchists, as the killers in the Braintree payroll robbery, native-born jurors were convinced they were already dealing with criminals. The legacy of the Red Scare is the belief that criticizing the actions of your country, its policies, its political leaders, or its historical assumption of moral superiority is inherently disloyal, possibly dangerous, and -- in anxious times -- positively criminal.

The enduring gifts of the Red Scare include the creation of an agency to harass people of with unpopular beliefs (the FBI), a systematic attack on first amendment freedoms. The American Legion, created back in 1919 to break strikes. The notion of "Americanism": that those criticize the nation's wars, capitalist economy or other policies should be suspected of disloyalty.

We saw that during the Vietnam era. It muted criticism of the Iraq War.

And like the era that produced it, the Sacco-Vanzetti case appears to shine a light on the darker side of American society's historical treatment of immigrants of 'unfamiliar' ethnicity. Periodically -- especially in those periods when a 'new' group of foreign nationals arrives in large numbers -- the so-called 'nation of immigrants' has exhibited a desire to close doors and build walls. Forgetful of their own non-native origins, many Americans are quick to close the borders on the next group of newcomers, whose language or manners, or religion, or skin tone, or potential for economic competition, or imagined demand for public services, is said to threaten the well-being of those already comfortably settled in the United States. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, it was the turn of Italians to be the most numerous and visible of these presumed-to-be-problematic newcomers. The lessons of the Sacco-Vanzetti case may still be staring us in the face, especially at a time when many countries in both the new and the old worlds are experiencing crises over the arrival of large numbers of 'others' within settled, comfortable, more ethnically homogeneous borders.

Published on January 25, 2017 13:55

January 23, 2017

The Garden of History: What the Women's March for America (Hopefully!) means.

It's very unusual to see the entire world celebrating -- or even acknowledging -- the same important moment at the same time. The last example of this to my mind is the worldwide welcoming of the new millennium at the dawn of 2000. As the earth spun through the sky, each new longitudinal slice of humanity celebrated the new all-world, all-peoples' milestone at the stroke of the midnight -- or they cheated a little on the timing, but who cares. It was the universality that accounted. Here we all are! Still here! And turning a page in triumph.

It's very unusual to see the entire world celebrating -- or even acknowledging -- the same important moment at the same time. The last example of this to my mind is the worldwide welcoming of the new millennium at the dawn of 2000. As the earth spun through the sky, each new longitudinal slice of humanity celebrated the new all-world, all-peoples' milestone at the stroke of the midnight -- or they cheated a little on the timing, but who cares. It was the universality that accounted. Here we all are! Still here! And turning a page in triumph.

So it was a true delight to see images of the weekend's Women's March from all over the world, all seven continents (as the newspapers put it). People standing up for decency, fairness, affirmation of women's and human rights. For democratic and egalitarian values. The pictures I saw are from the website of the New York Times. I hope the Times keeps the link available for a long time. Here's the link for the images: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2... Here's what these photos mean to me.

So it was a true delight to see images of the weekend's Women's March from all over the world, all seven continents (as the newspapers put it). People standing up for decency, fairness, affirmation of women's and human rights. For democratic and egalitarian values. The pictures I saw are from the website of the New York Times. I hope the Times keeps the link available for a long time. Here's the link for the images: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2... Here's what these photos mean to me.They're a vote for the view that love triumphs. An international vote for the values of caring, compassion, protection of the weak, the embrace of all human beings regardless of what country they live in, whatever their ethnic, religious background, gender, or the color of the skin. Everybody is a human being. Everybody is born of woman. Everyone is loved by someone (or many someones) and loves someone else. Everyone deserves decent living conditions. Everybody deserves a helpinghand when in need of one, and pretty much everyone will need one at one time or another.

Let's embrace that moment, and go from there.

Published on January 23, 2017 12:55

January 21, 2017

The Garden of Wisdom Literature: Kazuo Ishiguro's 'The Buried Giant' and the Secret Histories From Which We Hide

I loved this book. Any attempt to describe the setting or plot or characters or themes is likely to encounter something like derision. The couple are long married, aging, but don't really wish to think of themselves as old. Their living conditions are rough, primitively agrarian. They live in something like a cave dug out of the side of a hill. They share in the work of a community, in the fields or in others sorts of basic labor, but they speak to, and behave toward, one another with the gentility and courtesy of lovers in some courtly romance. One recalls that the author is Japanese, and that one of his previous novels is about the life of a perfect butler, "The Remains of the Day." The loving couple can't remember much about the past, but then nobody can. It appears their entire country is under some spell called "the forgetting." Have I mentioned that the events take place in Britain shortly after the time of King Arthur? Our ideal, older pair remember something about the times of Arthur, but they can't seem to remember anything about their son. Where did he go? Why did he leave their village? Maybe they should go visit him -- even though they don't know where he lives. Knights in heavy armor ride about the countryside. Outlaws are a concern. Supernatural beings make an appearance. Their only notion of a destination leads them to a Saxon village, where a "warrior" has just killed "a giant," the mere rumor of whose existence had terrorized the common people. Then there is the matter of the boatman.

I loved this book. Any attempt to describe the setting or plot or characters or themes is likely to encounter something like derision. The couple are long married, aging, but don't really wish to think of themselves as old. Their living conditions are rough, primitively agrarian. They live in something like a cave dug out of the side of a hill. They share in the work of a community, in the fields or in others sorts of basic labor, but they speak to, and behave toward, one another with the gentility and courtesy of lovers in some courtly romance. One recalls that the author is Japanese, and that one of his previous novels is about the life of a perfect butler, "The Remains of the Day." The loving couple can't remember much about the past, but then nobody can. It appears their entire country is under some spell called "the forgetting." Have I mentioned that the events take place in Britain shortly after the time of King Arthur? Our ideal, older pair remember something about the times of Arthur, but they can't seem to remember anything about their son. Where did he go? Why did he leave their village? Maybe they should go visit him -- even though they don't know where he lives. Knights in heavy armor ride about the countryside. Outlaws are a concern. Supernatural beings make an appearance. Their only notion of a destination leads them to a Saxon village, where a "warrior" has just killed "a giant," the mere rumor of whose existence had terrorized the common people. Then there is the matter of the boatman.None of these details help much in conveying the reader's deeply stirring experience of having found a magic doorway into an allegory of age-old, nearly forgotten, still robust wisdom. We learn, in time, that there is a reason for the general forgetting. It is questionable whether the general restoration of memory will do more good than the universal spell of forgetting did. Must there be "truth" before there can be "reconciliation"? Or is a general, communal forgetting the best way to put societal traumas behind us? And what truths must our genteel, loving, deeply bonded couple learn for themselves? ...

This book itself is a spell. A beautiful, enchanting spell like the company of a saint, or a guru, or a hermit on a hill who has seen everything. You never want it to be broken. You wish the story would never end. Sadly, however...

Published on January 21, 2017 21:16

January 19, 2017

The Garden of Exemplary Prose: Two Early Books by the Brilliant John Banville

I've read a number of novels by John Banville, a world-class Irish writer, whom I would nominate for a Novel Prize (though it was sweet to see Dylan get in this year), but I was wholly unaware of his early series of fictions based on central Western Civ scientific and mathematical figures. "The Newton Letter" was published back in the 1980s, and since I am reading this so-called 'trilogy' out of order, I have no context in which to place it. Standing completely on its own, it's another beautiful piece of writing but less completely mind-blowing than some of his later novels. It's short; almost more of a novella. And according to the reviews (which I would not otherwise know) is an updating of a famous novel from a couple centuries before by Goethe described as the paradigm demonstration of the relativity of point of view. Things, in this case relationships, look to be a certain way to the narrator, who involves himself in the lives of characters all of whom know truths about each other that escape the narrator. In Banville's treatment of this idea, his narrator -- a rather vain, self-absorbed scholar facing a problem in his current book project -- moves to the sticks for a quiet place to work, but does nothing but 'get involved' with the local family renting him his cottage. What he perceives to be the reality of their lives is a mere glimpse through a glass darkly. The demonstration-plot relates to Newton, the subject of our narrator's blocked book, because it suggests that time and space are not 'objective,' as Newton would have it, but 'relative.' I appreciate this point, and I appreciate Banville's marvelous wielding of the English language here, as ever; but as a character the narrator is not only rather despicable but flat and fairly uninteresting. He has no name --no doubt a literary choice to make a point. He also has no heart. The central figures in other of Banville's novels -- and countless works by other authors -- that I do care about are equally flawed and lack an appreciation of the harm they cause, but somehow they make me care about what I'm reading more than this privileged cypher does.

I've read a number of novels by John Banville, a world-class Irish writer, whom I would nominate for a Novel Prize (though it was sweet to see Dylan get in this year), but I was wholly unaware of his early series of fictions based on central Western Civ scientific and mathematical figures. "The Newton Letter" was published back in the 1980s, and since I am reading this so-called 'trilogy' out of order, I have no context in which to place it. Standing completely on its own, it's another beautiful piece of writing but less completely mind-blowing than some of his later novels. It's short; almost more of a novella. And according to the reviews (which I would not otherwise know) is an updating of a famous novel from a couple centuries before by Goethe described as the paradigm demonstration of the relativity of point of view. Things, in this case relationships, look to be a certain way to the narrator, who involves himself in the lives of characters all of whom know truths about each other that escape the narrator. In Banville's treatment of this idea, his narrator -- a rather vain, self-absorbed scholar facing a problem in his current book project -- moves to the sticks for a quiet place to work, but does nothing but 'get involved' with the local family renting him his cottage. What he perceives to be the reality of their lives is a mere glimpse through a glass darkly. The demonstration-plot relates to Newton, the subject of our narrator's blocked book, because it suggests that time and space are not 'objective,' as Newton would have it, but 'relative.' I appreciate this point, and I appreciate Banville's marvelous wielding of the English language here, as ever; but as a character the narrator is not only rather despicable but flat and fairly uninteresting. He has no name --no doubt a literary choice to make a point. He also has no heart. The central figures in other of Banville's novels -- and countless works by other authors -- that I do care about are equally flawed and lack an appreciation of the harm they cause, but somehow they make me care about what I'm reading more than this privileged cypher does. The novel "Mefisto" by John Banville is a beautifully written ice-cold nightmare, a diamond in the void. Like the prior novel, "The Newton Letter," it was written in the 80s, and I didn't discover his work until later. It also follows "Doctor Copernicus" and "Kepler," which with "The Newton Letter" are regarded as a trilogy on essential scientific figures. Some reviewers add to this group Mefisto, a novel centered on a math prodigy wandering through the incoherent universe of a backward Irish village, a decayed mansion, a failing mine, and the nearby "city" into which the narrator and the 'friend'-antagonist whose role appears to justify the book's title wander after the mine collapses. Our narrator, who's also a bit of an idiot-savant, and through whose eyes we witness the book's dysfunctional universe, never asks questions and takes no part in what we might consider an "ordinary" conversation. His brain records life, a technique that allows Banville to show us brilliant evocations of helpless, confused, 'special,' lost or horribly disfigured pieces of broken human machinery, which we also find completely convincing. Since reasonably healthy or 'normal' human interaction is missing here, nobody ever really talks to anybody, the reader has no better idea of what is 'going on' in the ordinary sense of narrative, plot or motivation. We're experiencing the narrator's life, that is, just the way he does. He can sit absorbed for hours in pure mathematics, playing with equations (if that's the right term, and I don't think it is), but he can't explain why he does what he does, or goes, or what he makes of the people he interacts with, because he doesn't think about any of these "issues" or "choices" the way people who have such conversations, or read novels, experience life. We're just getting the data, but it's offered to us by a cinema-verite style of narrative-presentation that smacks of genius. Does our narrator feel anything? We don't feel anything when his mother dies, because she's presented as a crabbed, backwards, small-minded rustic slightly more advanced than a segmented worm -- have we known such people? If not, why is this portrayal so completely recognizable? Since she's not lovable, perhaps her genius weirdo son should not be expected to care, but what does he feel or think about any of these others -- especially the Mefisto embodiment, whose gift of manipulative mischief is matched only by his stagey saloon-villain gift of gab that is a combination of both Shakespeare and Beckett and something for which I find no literary equivalent. Again, we feel we've encountered this character all our life. He hangs around watching things screw up, occasionally lending a hand, and then offers a wry, distancing word or two of commentary. Misery is his meat. He thinks it's all splendid. Our narrator somehow receives all this as non-judgmentally as a computer screen.... Near the book's end the coldness of this universe began freezing my blood, even as I recognize that its perfectly conceived nothingness is the product of a spectacular literary performance. When, finally, we discover one character of whose heart or mind we know nothing (because our narrator cannot 'go inside' of anyone) actually weeping over the death of another, whom we know only by her pointless round of meaningless actions, spiced with a little drug use, I felt myself wishing to cry as well. Oh, I thought, the humanity.

Published on January 19, 2017 22:00

The Newton Letter by John Banville

The Newton Letter by John Banville

The Newton Letter by John BanvilleMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

I've read a number of novels by John Banville, a world-class Irish writer, whom I would nominate for a Novel Prize (though it was sweet to see Dylan get in this year), but I was wholly unaware of his early series of fictions based on central scientific and mathematical figures. "The Newton Letter" was published back in the 1980s, and since I am reading this so-called 'trilogy' out of order, I have no context in which to place. Standing completely on its own, it's another beautiful piece of writing but less completely mind-blowing than some of his later novels. It's short; almost more of a novella. And according to the criticism (which I would not otherwise know) is an updating of a famous novel from a couple centuries before by Goethe described as the paradigm demonstration of the relativity of point of view. Things, in this case relationships, look to be a certain way to the narrator, who involves himself in the lives of characters who all know about each other truths that escape the narrator. In Banville's treatment of this idea, his narrator -- a rather vain, self-absorbed scholar facing a problem in his current book project -- moves to the sticks for a quiet place to work, but does nothing but 'get involved' with the local family renting him his cottage. What he perceives to be the reality of their lives is a mere glimpse through a glass darkly. The demonstration-plot relates to Newton, the subject of our narrator's blocked book, because it suggests that time and space are not 'objective,' as Newton would have it, but 'relative.' I appreciate it, and I appreciate Banville's marvelous wielding of the English language here, as ever, but as a character the narrator is not only rather despicable but flat and rather uninteresting. He has no name --no doubt, a literary choice to make a point. He also has no heart. The central figures in other of Banville's novels -- and countless works by other authors that I care about -- are equally flawed and lack an appreciation of the harm they cause, but somehow they make me care about what I'm reading more this privileged cypher does.

View all my reviews

Published on January 19, 2017 21:36

A Devilish Work

The novel "Mefisto" by John Banville is a beautifully written ice-cold nightmare, a diamond in the void. Like the prior novel, "The Newton Letter," it was written in the 80s, and I didn't discover his work until later. It also follows "Doctor Copernicus" and "Kepler," which with "The Newton Letter" are regarded as a trilogy on essential scientific figures. Some reviewers added Mefisto, a novel centered on a math prodigy wandering through the incoherent universe of a backward Irish village, a decayed mansion, a failing mine, and the nearby "city" into which the narrator and the 'friend'-antagonist whose role appears to justify the book's title wander after the mine collapses. Our narrator, who's also a bit of an idiot-savant, and through whose eyes we see the book's dysfunctional universe, never asks questions and takes part in what we might consider an "ordinary" conversation. His brain records life, a technique that allows Banville to show us brilliant evocations of helpless, confused, 'special,' lost or horribly disfigured pieces of broken human machinery, which we also find completely convincing. Since reasonably healthy or 'normal' human interaction is missing here, nobody ever really talks to anybody, the reader has no better idea of what is 'going on' in the ordinary sense of narrative, plot or motivation. We're experiencing the narrator's life, that is, just the way he does. He can sit absorbed for hours in pure mathematics, playing with equations (if that's the right term and I don't think it is), but he can't explain why he does what he does, or goes, or what he makes of the people he interacts with, because he doesn't think about any of these "issues" or "choices" the way people who have such conversations, or read novels, experience life. We're just getting the data, but it's offered to us by a cinema-verite style of narrative-presentation that smacks of genius. Does our narrator feel anything? We don't feel anything when his mother dies, because she's presented as a crabbed, backwards, small-minded rustic slightly more advanced in perception than a segmented worm -- have we known such people? If not, why is this portrayal so completely recognizable? Since she's not lovable, perhaps her genius weirdo son should not be expected to care, but he does not feel or think about any of these others, either -- especially the Mefisto embodiment, whose gift of manipulative mischief is matched only by his stagey saloon villain gift of gab that is a combination of both Shakespeare and Beckett and something for which I find no literary equivalent. Again, we feel we've encountered this character all our life. He hangs around watching things screw up, occasionally lending a hand, and then offers a wry, distancing word or two of commentary. Misery is his meat. He thinks it's all splendid. Our narrator somehow receives all this, as non-judgmentally as a computer screen.... Near the end the coldness of this universe began freezing my blood. Its perfectly conceived nothingness is the product of a spectacular literary performance. When, finally, we discover one character of whose heart or mind we know nothing (because our narrator cannot 'go inside' anyone) actually weeping over the death of another, whom we know only by her pointless round of meaningless actions, spiced with a little drug use, I felt myself wishing to cry as well. Oh, I thought, the humanity.

of

nothingness of

of

nothingness of

Published on January 19, 2017 21:33

•

Tags:

fiction, ireland, john-banville, mathematics, mefisto, novel

January 15, 2017

The Garden of History: Sacco and Vanzetti and Democratic Stress Tests in a Dangerous Time

I'll be speaking on my book "Suosso's Lane" at Duxbury Library on Sunday, Jan. 29, 2 p.m., my first opportunity following the inauguration of a new administration to address the potential lessons for our own time from the notorious Sacco and Vanzetti case, in which two Italian immigrants were convicted of murder in 1920 after a biased trial offering absurdly thin evidence of their guilt.

I'll be speaking on my book "Suosso's Lane" at Duxbury Library on Sunday, Jan. 29, 2 p.m., my first opportunity following the inauguration of a new administration to address the potential lessons for our own time from the notorious Sacco and Vanzetti case, in which two Italian immigrants were convicted of murder in 1920 after a biased trial offering absurdly thin evidence of their guilt. When that date arrives we will be a week into the reign of a new president whose election threatens to signal a decline of democratic and egalitarian values, much like the period in which two men were executed because of their beliefs and their ethnicity. A time of "us" and "them."

Following an election year when voters, given the creakingly vestigial Electoral College system, selected a candidate who proposed building a wall to keep out immigrants, creating a registry of all Americans who practiced a certain religion, and tightening entry rules to deny refuge even to those Muslims fleeing the violence of terrorists in their own countries, it may be wise to remember an earlier time when American democracy society had a nervous breakdown over immigrants. In 1919 and 1920 American democracy buckled under stress, resulting in the period known to history, but largely forgotten by the generations that followed, as the "Red Scare." When, years ago I asked Plymouth town selectman Alba Martinelli Thompson, the town's first female member of its governing select board and a former Air Force officer, what she remembered hearing from family members about the Sacco-Vanzetti case, she replied (in part), “They weren’t at all sure that the facts of the case were being honestly distributed. Also, it was the twenties. It was the Red Scare. Anybody with an immigrant name was suspect…”

The Red Scare came on the heels of a four-decade long period of record immigration, from 1880 to 1920, when 20 million immigrants mostly from southern and eastern Europe -- Italians, Russians, Poles, Jews, Greeks, Portuguese, Serbs, Syrians and others -- transformed the ethnic make-up of America's cities and towns and provided labor for its industrial revolution. The largest national group, more than 4 million, were Italians. Native-born Americans worried that their country was being 'flooded' by immigrants, and the influx was accompanied by so-called 'scientific' racial theories that teaching that people from those part of the world represented different, and inferior races. On top of this growing resentment and fear of these 'new Americans,' two major events transformed the nation's political climate in 1917. The United States entered World War I. And the Russian Revolution created a Communist regime frankly inimical to America's capitalist economic system. Communist parties elsewhere claimed Russia's transformation was the forerunner of a world-wide revolution, making other governments, including ours, nervous. America's entry into World War I led to a military draft. In the face of opposition, the government passed laws that criminalized political dissent, making criticism of the draft and the decision to fight the war illegal. These stress points led to open fractures because opposition to the war and draft was fierceist among the radical labor movements led by Socialists and Anarchists, many of whom were foreign nationals. Determining that 'opposition' meant 'subversion,' the federal government created the first true national police -- or spy service -- to investigate war opponents such as prominent Italian anarchist Luigi Galleani, founder of the Italian language newspaper Cronaca Sovversiva. Its subscribers included Nicolo Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. Apparently fearful of violent revolution, or widescale draft resistance, U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer obtained thousands of warrants to arrest radicals, search their premises, confiscate literature, and destroy presses. Under the influence of the country's new security apparatus he demonized the left-wing opposition to the war, saying: “The Red Movement is not a righteous or honest protest against alleged defects in our present political and economic organization of society… It is a distinctly criminal and dishonest movement in the desire to obtain possession of other people’s property by violence and robbery.” Each radical was therefore “a potential thief.”(25) If you believed that, you could believe that anarchists were likely to rob factory payrolls. A later generation would recognize this wholly ignorant smear of radical thought as McCarthyism. While anarchists and some socialists did not believe in private property, they believed property belonged to the whole community; and they did not believe in or practice taking property by theft or violence. When Galleani and other leaders of the Italian anarchist movement were prosecuted under laws banning criticism of the draft -- for comparison, imagine the result of this sort of laws during the Vietnam years -- and deported to Italy, Galleani's supporters struck back. Denied legitimate means of protest, their press shut down, its subscription list confiscated, their freedom of speech, press and assembly criminalized, anarchists turned to the only means they believed available to them: bombs. Bombs were mailed to government and big business targets in April of 1919; and hand-delivered to the homes and offices in June. One of the latter bombs destroyed half of Palmer's house, though no one there was hurt. These events were the immediate backdrop to the increased repressions of the Red Scare. Palmer launched two series of raids, in November of 1919 and January of 1920. His agents arrested thousands of 'aliens' without warrants, holding many for deportation often in horrendous conditions and without due process of law. Ultimately, only 446 were actually deported, once the courts intervened and a reaction against abuses of executive power took place. There were fourteen raids on leftists in Massachusetts, and in Boston five hundred aliens were marched through the streets in chains and taken to the Deer Island House of Correction, where they were isolated "in brutally chaotic conditions,”according to later government reports. It was against this backdrop that Sacco and Vanzetti -- two names federal agents knew from the subscription list to the anarchist newspaper "Cronaca Sovversiva" -- were charged with the robbery a Braintree shoe factory payroll and the killing of two payroll officers despite the absence of direct evidence, convicted by a native-born Massachusetts jury that believed foreign anarchists should be 'strung up,' and sentenced to death by judge who bragged to a friend, "Did you see what I did to those anarchist bastards?" The Sacco-Vanzetti case appears to shine a light on the darker side of American society's historical treatment of immigrants of 'unfamiliar' ethnicities. Periodically -- especially in those periods when a 'new' group of foreign nationals arrives in large numbers -- the so-called 'nation of immigrants' has exhibited a desire to close doors and build walls. Forgetful of their own non-native origins, many Americans are quick to close the borders on the next group of newcomers, whose language or manners, or religion, or skin tone, or potential for economic competition, or imagined demand for public services, appears to threaten the well-being of those already comfortably settled in the United States. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, it was the turn of Italians to be the most numerous and visible of these presumed-to-be-problematic newcomers. The Sacco-Vanzetti case may still hold lessons for the 21st century, especially at a time when many countries in both the new and the old worlds are experiencing crises over the arrival of large numbers of 'others' within settled, comfortable, more ethnically homogeneous borders. One such lesson, at least in the US, appears to be that a native-born English-speaking population is disposed to believe that foreign nationals are capable of behaving in a criminal, violent manner and committing all manner of horrendous acts simply because they belong to "races" or "peoples" who are inherently different from themselves. They are foreigners, outsiders, trouble-makers, aliens, "illegals." As immigrants from a body of people inherently "different" from "us," they are more likely to believe in hateful, radical, un-American ideas -- such as Sacco and Vanzetti's anarchism of a century ago, or today's so-called 'Islamic' militancy -- than are those born in this country from "old stock," speaking English and capable of "understanding democracy." It's hard not to conclude that the simple fact that the two men were Italians -- not 'real' Americans -- weighed, perhaps fatally, against Sacco and Vanzetti. As Vanzetti himself put the matter in his last speech to the court: "I am suffering because I am a radical and indeed I am a radical; I have suffered because I am an Italian, and indeed I am an Italian."

Published on January 15, 2017 15:37

January 12, 2017

The Garden of Verse Blooms in March: "Gardeners Do It With Their Hands Dirty"

My first collection of poems, "Gardeners Do It With Their Hands Dirty" is scheduled for release in March. These are poems about plants, gardening, flowers, nature, talking to trees, getting stared at by a hummingbird. Seasons change and so do we. Also poems about family, places near and far, my father's near-fatal in World War II, family secrets, The Sacred Way at Delphi, Greece, Syrian refugees in Beirut, and a tricksy formal poem called The Slow Tritina. "Gardeners Do It With Their Hands Dirty" is what's called a 'chapbook,' meaning a half-size volume. This is a common way to publish poetry. I'm not sure I know why, but it gets a bunch of poems between covers, so I'm very happy about it. All of the poems in this collection have been published before in journals, many of them in Verse-Virtual.com. I am contributing editor to that online poetry journal, and my work appears there monthly. I asked two of my colleagues from Verse-Virtual to do me the favor of writing recommendations for this book, and their kind words (quoted below) for my efforts will appear on the volume.

Robert Knox’s well-tended garden of verses furnishes readers with elegant borders, unexpected vistas, gorgeous blossoms, and insights sharp as thorns. His themes are as local as the backyard and as universal as weather. The poet is tuned into the present, like the journalist he also is; he is as deeply read as a scholar, and the verses he produces simply aren’t biodegradable. Some are annuals, commentaries on the immediate; others are perennials, novel explorations of transcendent themes. No matter his subject, Robert Knox’s writing is never less than rewarding. His work is that of a gifted and generous writer sensitive to all the personal and public events enacted before nature’s scrim of seasons, to all that lives and grows and dies.-- Robert Wexelblatt, poet, scholar, author of the story collection "Heiberg’s Twitch" and other books

Robert Knox is a brilliant writer whose bountiful work I am privileged to publish. His new collection of poetry, 'Gardeners Do It With Their Hands Dirty,' blossoms with wonder, wisdom, and wit. I highly recommend it. -- Firestone Feinberg, editor of Verse-Virtual

The publisher, "Finishing Line Press," has put lots of poetry between covers over the last twenty years. There are literally hundreds of items in the company's website bookstore. Here's the link for my forthcoming title: https://www.finishinglinepress.com/pr... Any books purchased as pre-order sales will give me an added boost, because the size of my book's print run will be determined by the advanced sales. The more books ordered in advance, that is, the greater the total number of copies the publisher will print. Then it will be my job to find places to read from "Gardeners." Nobody ever begins writing poems because they think it will pay. But it's a great pleasure to connect with an audience.

Published on January 12, 2017 20:24