Robert Knox's Blog, page 31

April 20, 2017

The Garden of April Poetry: Morris Dancers Kicking Up Their Metrical Feet

The prompt for April 17 by the napowrimo.com website, a site dedicated to encouraging poets to write a new poem every day in April -- National Poetry Month -- calls for writing a poem relying on neologisms.

The prompt for April 17 by the napowrimo.com website, a site dedicated to encouraging poets to write a new poem every day in April -- National Poetry Month -- calls for writing a poem relying on neologisms. Here's how the site put it:

Today, I challenge you to write a poem that incorporates neologisms. What’s that? Well, it’s a made-up word! Your neologisms could be portmanteaus (basically, a word made from combining two existing words, like “motel” coming from “motor” and “hotel”) or they could be words invented entirely for their sound. Probably the most famous example of a poem incorporating neologisms is Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky, but neologisms don’t have to be funny or used in the service of humor."

[http://www.napowrimo.net/]

Well, not to put too fine a point on it, "Jabberwocky" (which appears in "Through the Looking Glass") is pretty funny, and Lewis Carroll sets a pretty high standard as a model.

The poem I'm sharing here attempts to capture some of the stylishly antic fun exhibited by the Newtown Morris Dancers, who ply their deeply traditional art of folk dance on Easter morning on Newbury Street in Boston's Back Bay directly after the Easter service at Emanuel Church.

They definitely slow down traffic.

The photo above gives a good idea of their costumes and suggests something of upbeat, open, yet carefully prescribed style of their art. Morris Dance dates back to a region of England from a long time ago. The dance is traditional, the costumes and music traditional, the Newtown Morris Dancers a Boston tradition, their appearance outside the church on Easter a pretty long-lasting tradition by itself, and Easter itself -- well all sorts of connections spring up there.

Here's my attempt to pack it all up in a poem with made-up words.

The Morris Dancers on Newbury Street

Twirl updown and crownaroundYour stickles brain percussion, your ankledings make sound

You have a rather handy look, your brawn is rather shandyYou eyes flow from the babelbrook, Do you feed them naught but candy?

You music goes a circle bendComes back to make a neverendWhat churchkey fellow found a brewTo bottle up the likes of you?

Twupsy-doo and jarl about Your feet choptime and rabble out Your beaks remind me of the rout Who tear my cherry blossoms out

Twirl updown and crownaroundYour stickles brain percussion, your ankledings make sound No mankey man can Morrisleap and dare to wear a frown

Published on April 20, 2017 19:55

April 19, 2017

The Garden of Verse: Melancholy Evenings Recollected in Tranquility

It's still April, and we're back at it. The prompt for April 17 by the napowrimo.com website, a site dedicated to encouraging poets to write a new poem every day in April, called for writing a verbal nocturne.

It's still April, and we're back at it. The prompt for April 17 by the napowrimo.com website, a site dedicated to encouraging poets to write a new poem every day in April, called for writing a verbal nocturne.Here's how the site put it:

"Today, I challenge you to write a nocturne. In music, a nocturne is a composition meant to be played at night, usually for piano, and with a tender and melancholy sort of sound. Your nocturne should aim to translate this sensibility into poetic form! Need more inspiration? Why not listen to one of history’s most famous nocturnes, Chopin’s Op. 9 No. 2?"

I listened to Chopin's Nocturne, Op. 9 No.2. I listened to a lot of other piano music loosely described as "similar" -- including Beethoven's "Moonlight Sonata," which is not melancholic, but romantic and just generally inspiring. My poem probably owes more to the enlivening effect of listening to good, strong music than to the delicacy of sentiment required by the Nocturne, nevertheless here it is:

Not Songs of Spring, but November Moans

Rain at dusk and steely gray all afternoon. I'll finish off that Dubonnet and straighten up, After all I may die soon. Darkness falls at four o'clock, time for a cup Of bitters with a little gloom. Do I dare to twist a dial and hear the latest cover-up? Some silence settles on the room Now please get dressed and get some din Before la tristesse barges in...

Oh no I fear, the darling fiend's already here I feel him stretch his hand for me To bind me up in weightless coils of SAD and subtle tears. I'll trace my nights on leaves of tea: The moon, the rain, and the restless sea.

And if you're truly interested in learning more about nocturnes, not the parody but the straight gin, see Robert Wexelblatt's poem "Nocturnes," which (wholly coincidentally) appears on this month's Verse-Virtual.com at: http://www.verse-virtual.com/robert-w...

Published on April 19, 2017 07:30

April 17, 2017

National Poetry Month: Between the Beginning of Things and the End

On Day Fifteen (which this year happened to be Easter) of National Poetry Month (also known as April), with the month now halfway behind us, the prompt from

NaPoWriMo/GloPoWriMo

asked us to write a poem on what it means to be in the middle of things.

asked us to write a poem on what it means to be in the middle of things. Here's a quote from the

NaPoWriMo/GloPoWriMo site on today's theme: "...write a poem that reflects on the nature of being in the middle of something. The poem could be about being on a journey and stopping for a break, or the gap between something half-done and all-done. Half a loaf is supposedly better than none, but what’s the difference between half of a very large loaf and all of a very small one? Let your mind wander into the middle distance, betwixt the beginning of things and the end."

My poem is titled by the Latin phrase meaning "in the middle of things":

In Medias Res

Nick made it home just in time to meet the Easter Bunny.Devils were lurking in the trees. Pamela summoned a special potion.Down on Cemetery Lane, the little people were choosing between fortune and fame.When the plague arrived in our district, many of us recollected old debts we had either forgotten to pay -- or to call in.On Project Hill people were coming and going with brows similarly furrowed.The story began small, dithered at the first turn, lunged forward unexpectedly, then retraced its steps.The intermezzo... ... the intermezzo.Behind the curtain the leading lady, larger than life, paced back and forth, glaring at anyone who came too near. She's always like this, her handler remarked quietly, when she's about to swallow a snake.I'm not looking for lukewarm praise, the artist said. Ordinary expressions of pleasure will do fine. Fear crept into the town, like a disappointed lover with a score to settle.We have to stop meeting like this, Lila said, resting her back on a tombstone. Pamela waited. It was her last trick. Would it work?It was not the Easter Bunny. And it was too late to close the door.

Published on April 17, 2017 20:47

April 16, 2017

National Poetry Month: Let's Start in the Middle

Here is my poem for Day 14 of National Poetry Month. It's written in response to a prompt from the NaPoWriMo/GloPoWriMo! site that provides encouragement, support, and community for people who are trying to write a poem each a day through the month of April.

Here is my poem for Day 14 of National Poetry Month. It's written in response to a prompt from the NaPoWriMo/GloPoWriMo! site that provides encouragement, support, and community for people who are trying to write a poem each a day through the month of April. The site also provides a different kind of prompt each day, examples, places to find for more examples, in addition to its other features. [Check out the site at http://www.napowrimo.net/]

Here is the site's prompt for April 14:"Because it’s Friday, let’s keep it light and silly today, with a clerihew. This is a four line poem biographical poem that satirizes a famous person."

The site offers this example:

Emily Dickinson

wasn’t a fickle one.

Having settled in Amherst,

she wouldn’t be dispersed.

Here's my offering, titled "Hell of a Time":

Hieronymus Bosch Grew a garden of squash. Dealing with black spot, Beelzebub fly, and weather sub-prime By the evidence of art he had a hell of a time.

Published on April 16, 2017 21:01

April 12, 2017

The Garden of 'ArtSake': What Is Your Greatest Need?

I'm flattered to be included in an online publication hosted by the Massachusetts Cultural Council, my state's arts agency, called "ArtSake."

I'm flattered to be included in an online publication hosted by the Massachusetts Cultural Council, my state's arts agency, called "ArtSake." ArtSake publishes a moderated blog in order -- in the council's words -- "to carve out a space where we celebrated art and art-making for its inherent merits. We’ll use this space to celebrate our state’s innovative and creative minds, highlight new projects, and feature ideas and content straight from the artists."

ArtSake's project officer Dan Blask was recently seeking comments from artists and writers about issues they face in their work and lives. He posed the question

What is your greatest need, as an artist?

ArtSake's project officer Dan Blask was recently seeking comments from artists and writers about issues they face in their work and lives. He posed the question

What is your greatest need, as an artist?

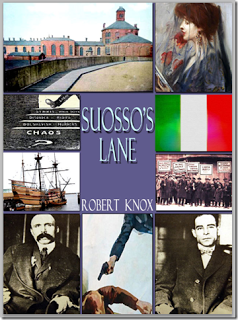

The resulting blog included my response and also mentioned my upcoming public programs, including my talk about "Suosso's Lane" Thursday, April 13, at 7 p.m. at the Ventress Memorial Library, 15 Library Plaza, in Marshfield.

So here's me quoting myself, courtesy of Art Sake:

Robert Knox , writer and poet

I’m a fiction writer and poet. My greatest need is ways to connect with readers. Happily, I’m in a stage of life when my most pressing needs are no longer time or money. But I want to see the books that I finally have time to write get into print, or get read, or even noticed somehow. Commercial publication of fiction is a narrow funnel, except for certain formulaic genres, and agents look to meet specific marketing needs. Newspapers, a declining industry in which I’m partially employed, review few books. After my novel Suosso’s Lane was published a year ago by a small independent, I find most of its readers myself through public programs at libraries. Many of the fiction writers I know publish their own books and sell them on Amazon. Poetry is an even more self-contained universe. I’m not proposing any solutions here, just stating a need: How do we get read?

Robert Knox discusses his novel Suosso’s Lane at the Ventress Memorial Library in Marshfield (4/13, 7 PM). He’ll read from his poetry collection Gardeners Do It With Their Hands Dirty at Plymouth Public Library (4/24, 7 PM). Currently, he has poetry published in Verse-Virtual.com, where he is a contributing editor.

Here's the link for the full discussion of the question What is your greatest need, as an artist?

http://artsake.massculturalcouncil.or...

Published on April 12, 2017 14:02

April 6, 2017

The Protest Garden: If Winter Chilled Our Souls, Can Spring Renew Our Hope?

Here's the beginning of my poem entitled "Salute to a Winter," which appears in the April 2017 issue of Verse-Virtual:

Here's the beginning of my poem entitled "Salute to a Winter," which appears in the April 2017 issue of Verse-Virtual: Where did you go when we were not looking?

Did we leave you in the boarding area for the airplane to take us away

to some milder place where the headlines did not show us the ugly masks

donned by D-list actors bumbling through a remake of The Great Dictator?

Or in the florist shop choosing tropical blooms the size of small bedrooms

to hide us from the ugliness outside,

when goons with flag pins seized house cleaners to send them away from their children

and protect for our native countrymen the honor of cleaning toilets and picking fruit?

...

Though I wrote the poems that appear in the current issue of Verse-Virtual, an online poetry journal, before National Poetry Month (April: that annual celebration of poetic-self) began, I am encouraged by Bill Moyers' timely linkage of poetry and national memory. Moyers quotes Czech writer Czeslaw Milos on the dangers of "a refusal to remember" and argues that "memory is crucial if a people are not to be at the mercy of the powers-that-be, if they are to have something against which to measure what the partisans and propagandists tell them today."

So this month I am offering more "measures" to apply to the current state of national affairs. Having exhausted rational analysis and pure invective, I am working my way through dystopian comparisons. When I consider the entire year-plus election season and the miserable first months of the new so-called administration, it seems to me that the entire country has plunged into an episode of "The Twilight Zone."

One knows from experience that these scripts don't end well.

Anyway... my other offerings in April's Verse-Virtual glance directly, or somewhat indirectly, at our current situation, by way of debts to the most political (and radical) of English poets, Shelley.

The first of three, titled "From 'The Grate America' Victory Tour," was inspired by the opening stanzas of Shelley's poem about a massacre of political opponents (titled "The Mask of Anarchy").

My offering begins:

We traveled down to old LA

and met some killers on the way

dragging Lady Liberty to the dump

They all wore masks that looked like Trump

On either side the chains they bore

Drove women from the homes they saw

Their uniforms were dark and bright

That screamed of anguish in the night

...

The second of these poems borrows its title ("Spring Not Far Behind") from one of the most quoted of Shelley's lines: "If winter's here, can Spring be far behind." This line is taken from the conclusion of Shelley's famous "Ode to the West Wind."

Spring, for Shelley, meant a fresh start for human society: reform, recognition of human rights, shared wealth. My own short poem's final line ("New seasons bloom on Western gale") alludes to Shelley's faith that a new hope for humanity arrives on that vernal west wind.

The most widely read of Shelley's poems -- it's a short one, a sonnet -- is probably "Ozymandias." My comparison ("Goddess") imagines the contemporary trashing of our nation's most famous monument, the great image of freedom installed New York harbor. "Goddess" begins:

The shattered crown full fathoms lies

Of antique form and freedom's fame

That boasted of one country free

And proud, days past, to wear the name

Of Liberty....

You can read these poems, and find many others by many fine poets, on

http://www.verse-virtual.com/robert-c-knox-2017-april.html

Published on April 06, 2017 14:06

April 4, 2017

The Garden of Verse: Every Day Poets in the 'Cruelest' Month of April

It's that wonderful time of year when people who write poetry and read it (or do either; or both) ask themselves why they do it, and perhaps not surprisingly find plenty of reasons to explain why they do.

It's that wonderful time of year when people who write poetry and read it (or do either; or both) ask themselves why they do it, and perhaps not surprisingly find plenty of reasons to explain why they do. April, National Poetry Month, stimulates many gardens of celebration and explanation.

Here's a quote from Bill Moyers' website:

Democracy needs her poets, in all their diversity, precisely because our hope for survival is in recognizing the reality of one another’s lives.

[http://billmoyers.com/story/celebrati...#]

Moyers then quotes the poet W.S. Merwin in this statement:

Against the sybaritic images of advertising that daily wash over us, against the sententious rhetoric of politics, poetry stands as “the expression of faith in the integrity of the senses and of the imagination.” (W.S. Merwin’s description).

Finally, he turns to Czech Nobel Prize winner Czeslaw Milosz on the dangers to free society posed by "a refusal to remember." Memory is crucial, Moyers argues, "if a people are not to be at the mercy of the powers-that-be, if they are to have something against which to measure what the partisans and propagandists tell them today."

Hmm, what about 'today' can he be thinking about?

The case for the civic value of poetry is also made by a story in Salon magazine by Alissa Quart, who writes that poetry can appear to be "suffocatingly personal; excessively decorative; exhaustingly bourgeois or tiringly avant-garde. (Some of this is true, especially the bourgeois part.)"

http://www.salon.com/2015/05/20/dont_...

It's always good to hear a little constructive criticism, don't you think?

Nevertheless, Quart argues: "Yet we shouldn’t give up on poetry, if only because we need a different public language to describe our country. Conventional public discourse is boring, too familiar and brittle: the spray-on-tan blather of pundits on CNN, the coo of commerce, the drained, template-like rhetoric of political speech."

Some colorful language in that final sentence; I wonder if Ms. Quart has turned her hand to a little of this poetry stuff.

David Graham also turns to the question of poetry's value in his column "Poetic License" in the April issue of Verse-Virtual.com. The discussion here turns to the personal value. Here's an excerpt from his discussion:

"... [M]y love of poetry grows directly from my practice of it. As with many basic enjoyments, repetition deepens rather than dulls the pleasure. That’s why I keep writing and pondering this art. In a way, it’s like the reverse of the old joke: “Why hit myself in the head with a hammer? Because it feels so good when I stop.” I keep at it because it feels so good when I don’t stop."

I don't think anyone is stopping. Though whether poetry is a useful weapon (or tool) in our species's struggle for survival, save democracy, combat meretricious speech, preserve societal memory, or retake language from the hands of the traders in facile, deceptive, or self-serving or merely boring wielders of our common speech -- arguably humanity's greatest strength -- remains to be seen.

Still, if it's 'Celebrate Poetry Month,' I'm up for the party.

Published on April 04, 2017 13:12

March 28, 2017

The Garden of Verse: 'Immortal' Glimpses Into the Lives of Poets

The title of this largely entertaining peek into the lives of creative artists in the early 19th century by Stanley Plumly, "The Immortal Evening: A Legendary Dinner with Keats, Wordsworth, and Lamb," mentions the names of three literary worthies likely to create an interest in lovers of poetry. Particularly the great age of English Romantic poetry. The title does not include the name of another artistic figure, Benjamin Robert Haydon -- a painter, not a poet -- who was the host for this "immortal evening." While he is not remembered the way the three writers are, at one time paid, public exhibitions of his ambitious historical paintings drew thousands of visitors in London and other sites.

The title of this largely entertaining peek into the lives of creative artists in the early 19th century by Stanley Plumly, "The Immortal Evening: A Legendary Dinner with Keats, Wordsworth, and Lamb," mentions the names of three literary worthies likely to create an interest in lovers of poetry. Particularly the great age of English Romantic poetry. The title does not include the name of another artistic figure, Benjamin Robert Haydon -- a painter, not a poet -- who was the host for this "immortal evening." While he is not remembered the way the three writers are, at one time paid, public exhibitions of his ambitious historical paintings drew thousands of visitors in London and other sites. The book's title evokes the enduring importance of the three writers, especially the poets Keats and Wordsworth. Lamb was most successful as a storyteller and informal essayist, popular in his time and for generations after, though not widely read today. But Haydon has been largely forgotten. His genre, "historical painting," has been entirely superseded, first by photography and then by film. The painting he was working on (and would take six years to complete) when he invited his literary friends for Sunday dinner, followed by a late supper, and apparently a good deal of wine throughout, was "Christ's Entry into Jerusalem." The particular reason for inviting the three writers (a few other guests were invited as well) was that all three had posed for Haydon and their faces, their figures clothed in period dress, appear among the crowd of observers depicted witnessing the momentous arrival of the great religious teacher. I found it hard to warm up to this painting. Plumly makes no case for it as great art either. The book's central preoccupation is what was wrong with Haydon's view of his vocation and his art, and with Haydon himself -- what keeps him, that is, despite his out-sized confidence in his own genius from being among the immortals. Rather than his painting it's his obsessive journal-keeping about his life and times that interests us today. His record of the memorable 'evening' serves as the book's lens into the characters of the 'immortal' figures and leads to his reflections about them at other times. But much of "The Immortal Evening" focuses on Haydon's "unsuccessful" life and this is the limitation of Plumly's approach. Almost anything else that Plumly writes about here is more interesting than his analysis of Haydon's failings, which at times appears to grow repetitious. It's the kind of book where you leaf ahead to see when the names of the people you are interested in, Wordsworth or Keats or Coleridge -- who, though unavailable for the feast or to pose for the painting, gets a lot of ink here too -- next turn up. So the hook -- three great writers who sort of know each other get invited to dinner by a guy who appears to be a better host than he is an artist -- attracts, but the book delivers less of what I want and more than I need to know about a period painter who happened to write an awful lot of diary and memoir stuff. At one point Plumly says of Haydon that he should have been a writer. Himself a poet, Plumly is a very good writer, and I would read anything he has to tell me about Keats, Wordsworth, Coleridge or their period. Haydon's life may invite our sympathy, but like his paintings as a subject he's ephemeral. Plumly, who wrote a book titled "Posthumous Keats," which I read enthusiastically a few years ago, might be regarded as the high chef of literary biographical slices. Keats, who died at 26, had a short life, but Plumly's book concentrates on how its ending has fixed our notion of a young man of genius, who (it seems to me) resembles the famous pursuer of a dream in his own "Ode to a Grecian Urn":

Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal...

Keats won't age, won't decline, won't disappoint his fans, can never be accused of "failing to live up" to expectation of his early brilliance. Here Plumly quotes this judgment by the ill-fated painter Haydon: "Keats is the only man I ever met with who is conscious of a high calling... except Wordsworth." In fact the arc of Wordsworth's artistic biography takes a path opposite to Keats's. His best work is done in his early years; by the time Haydon and Keats, and most English speakers, become acquainted with his great poetry, Wordsworth is at the peak of his fame but his inspiration is gone. He lives a long life, but falls increasingly out of favor, especially to those who loved his great work. As for Lamb, of whose career I knew almost nothing, his biography is also a cautionary tale. Despite wide publication and popular favor, he spends almost his whole life as a clerk in a civil service office, supporting a troubled family. He takes long rambles through his beloved London and gets amusingly drunk at Haydon's "immortal" party. For readers, especially English major types, fascinated by the two genius generations of Romantic poetry, slices of life from period letters and diaries woven together by an author who is a master of the field are like peeks into the lives of the rich and famous by the celebrity lovers of our own day. Only, to make explicit my own prejudice, learning what these guys thought about, or said about themselves -- or about one another -- is actually worth the effort. Keats knew who he was, and it is interesting that a fellow artist who misjudged his own destiny also knew. Haydon puts his three writer friends into his would-be masterpiece as figures among a watching crowd as Christ on a donkey (wearing a tiara of heavenly glow) pushes past them into the holy city. Wordsworth's face droops downward with heavy thoughts. Lamb looks abashed at divinity's approach, while Keats passionately argues his own line of thought. Plumly's fascinating book, perhaps unavoidably, puts Haydon in the center of the picture. But our eyes, and thoughts, are on the guys in the corner.

Published on March 28, 2017 21:12

March 26, 2017

The Immortal Evening: A Legendary Dinner with Keats, Wordsworth, and Lamb

[By the author of Posthumous Keats: A Personal Biography|3237684]

The title of this largely entertaining peek into the lives of creative artists in the early 19th century by Stanley Plumly, "The Immortal Evening: A Legendary Dinner with Keats, Wordsworth, and Lamb," mentions the names of three literary worthies likely to create an interest in lovers of poetry. Particularly the great age of English Romantic poetry. It does not include the name of the artistic figure, Benjamin Robert Haydon -- who was a painter, not a poet -- who was the host for this "immortal evening." He is not remembered the way the three poets are, though at one time paid, public exhibitions of his ambitious historical paintings drew thousands of visitors in London and other sites.

So the title, given to this gathering in his studio lodgings by Haydon, retains its insight into the value of the careers of the three writers, especially the poets Keats and Wordsworth. Lamb was most successful as a storyteller and informal essayist, popular in his time and for generations after, though not in a way that either made him rich in his own day or widely read today.

But Haydon has been largely forgotten. His genre, "historical painting," entirely superseded first by photography and then by film. The painting he was working on (and would for six years) when he invited his literary friends for Sunday dinner, followed by supper later, and apparently a good deal of wine throughout, was "Christ's Entry into Jerusalem." The particular reason for inviting the three writers (a few other guests were invited as well) was that all three had posed for Haydon and their faces, given period dress, appear among the crowd of observers depicted witnessing the momentous arrival of the great religious teacher.

I found it hard to warm up to this painting. Plumly makes no case for as great art either, and the central preoccupation is what is wrong with Haydon's art his view of himself as an artist, and Haydon himself -- what keeps him, despite his out-sized confidence in his own genius, from being among the immortals. What interests us today, it turns out, is what the obsessive journal-keeping artist has to say about this times, the memorable 'evening' that serves as the book's lens into the characters of the 'immortal' figures, and his reflections about them as other times.

But much of the book focuses on Haydon's "unsuccessful" life and this is the limitation of Plumly's approach. Almost anything else that Plumly writes about here is more interesting than his analysis, often repetitious, of Haydon's failings. It was the kind of book where you leaf ahead to see when the names of the people you are interested in, Wordsworth or Keats or Coleridge -- who, though unavailable for the feast, or to serve as an extra in the portrait -- gets a lot of ink here.

So the hook here -- three great period writers, who sort of knew each other get invited to dinner by a guy who appears to be a better host than he is an artist, works, but the book delivers less of what I wanted as a reader and more than what I wanted to know about the impinging subject of a Romantic painter who happened to write an awful lot of diary and memoir stuff. At one point Plumly says he should have been a writer.

Plumly, himself a poet, is a very good writer, with interesting insights into all his figures. I would read anything he has to tell me about Keats, Wordsworth, Coleridge -- does he have a book Shelley or Byron or Blake in the works? I would be happy with any of those mighty subjects. But Haydon, like his paintings, may invite our sympathy, but as a subject he's ephemeral.

The title of this largely entertaining peek into the lives of creative artists in the early 19th century by Stanley Plumly, "The Immortal Evening: A Legendary Dinner with Keats, Wordsworth, and Lamb," mentions the names of three literary worthies likely to create an interest in lovers of poetry. Particularly the great age of English Romantic poetry. It does not include the name of the artistic figure, Benjamin Robert Haydon -- who was a painter, not a poet -- who was the host for this "immortal evening." He is not remembered the way the three poets are, though at one time paid, public exhibitions of his ambitious historical paintings drew thousands of visitors in London and other sites.

So the title, given to this gathering in his studio lodgings by Haydon, retains its insight into the value of the careers of the three writers, especially the poets Keats and Wordsworth. Lamb was most successful as a storyteller and informal essayist, popular in his time and for generations after, though not in a way that either made him rich in his own day or widely read today.

But Haydon has been largely forgotten. His genre, "historical painting," entirely superseded first by photography and then by film. The painting he was working on (and would for six years) when he invited his literary friends for Sunday dinner, followed by supper later, and apparently a good deal of wine throughout, was "Christ's Entry into Jerusalem." The particular reason for inviting the three writers (a few other guests were invited as well) was that all three had posed for Haydon and their faces, given period dress, appear among the crowd of observers depicted witnessing the momentous arrival of the great religious teacher.

I found it hard to warm up to this painting. Plumly makes no case for as great art either, and the central preoccupation is what is wrong with Haydon's art his view of himself as an artist, and Haydon himself -- what keeps him, despite his out-sized confidence in his own genius, from being among the immortals. What interests us today, it turns out, is what the obsessive journal-keeping artist has to say about this times, the memorable 'evening' that serves as the book's lens into the characters of the 'immortal' figures, and his reflections about them as other times.

But much of the book focuses on Haydon's "unsuccessful" life and this is the limitation of Plumly's approach. Almost anything else that Plumly writes about here is more interesting than his analysis, often repetitious, of Haydon's failings. It was the kind of book where you leaf ahead to see when the names of the people you are interested in, Wordsworth or Keats or Coleridge -- who, though unavailable for the feast, or to serve as an extra in the portrait -- gets a lot of ink here.

So the hook here -- three great period writers, who sort of knew each other get invited to dinner by a guy who appears to be a better host than he is an artist, works, but the book delivers less of what I wanted as a reader and more than what I wanted to know about the impinging subject of a Romantic painter who happened to write an awful lot of diary and memoir stuff. At one point Plumly says he should have been a writer.

Plumly, himself a poet, is a very good writer, with interesting insights into all his figures. I would read anything he has to tell me about Keats, Wordsworth, Coleridge -- does he have a book Shelley or Byron or Blake in the works? I would be happy with any of those mighty subjects. But Haydon, like his paintings, may invite our sympathy, but as a subject he's ephemeral.

Published on March 26, 2017 15:39

•

Tags:

coleridge, haydon, historial-art, keats, lamb, london, poetry, romantic-poets, wordsworth

The Garden of History: Richard III and the End of the Middle Ages

This is a book that engages both a love of history and an interest in those who search for history, dig for it or otherwise create 'new' history, a seeming paradox. As the head archeologist repeatedly states in this multi-purposed book, "Digging for Richard III: The Search for the Lost King," you don't go looking to find the graves of famous historical figures and you pretty much never find them. You plan digs after careful research, probably preliminary digs that suggest that there may be finds of some scientific interest if you plan an organized, well-prepared, funded dig with a reasonable chance of telling you something more about the human uses of a particular site in the depths of time. Nevertheless, this archeological project in Leicester, England, a place with a university and a long history of human settlement, truly began with a contemporary woman's -- intuition? psychic summons? -- that she knew where the grave of Richard III could be found.

This is a book that engages both a love of history and an interest in those who search for history, dig for it or otherwise create 'new' history, a seeming paradox. As the head archeologist repeatedly states in this multi-purposed book, "Digging for Richard III: The Search for the Lost King," you don't go looking to find the graves of famous historical figures and you pretty much never find them. You plan digs after careful research, probably preliminary digs that suggest that there may be finds of some scientific interest if you plan an organized, well-prepared, funded dig with a reasonable chance of telling you something more about the human uses of a particular site in the depths of time. Nevertheless, this archeological project in Leicester, England, a place with a university and a long history of human settlement, truly began with a contemporary woman's -- intuition? psychic summons? -- that she knew where the grave of Richard III could be found.I'll be frank. It's the history that interests me most, and that attracted me to this book. Richard III is of course one of the most controversial kings, perhaps the most, in English history. Shakespeare, following earlier writers and traditions, blame him for the murder of two young claimants to the British crown ("the princes in the tower"), and Shakespeare's famous history play "Richard III" turned him into a monstrous and notable villain. A reaction, typified by the novel "Daughter of Time," looked at the historical evidence and concluded that Richard was a well-intended monarch who had been bad-mouthed by his enemies after his death. No evidence, this view says, shows that Richard had the princes killed.

So for me the highlight of this book comes at the beginning when author Mike Pitts gives a clear account of the War of the Roses, enumerating the twists and turns of the (mostly bloody) conflict between various branches of royal descendants over who had the better claim to the throne. Here are some of my gleanings from this book's account: Richard III, a member of the York line, and the last British kind to die in battle, lived from 1452 to 1485, a short life. He contended for the throne, made enemies, vanquished them for the crown, then fought to keep it and died in the effort. His death at Bosworth, marking the end of the Wars of the Roses, also initiates the reign of the Tudor dynasty. Also, arguably, the battle at Bosworth marks the end of the Middle Ages for England. Richard's lifetime saw the first book printed in English, the Caxton Bible, in 1473. Richard III owned one book, a slender "book of hours" prayer book; that's the pre-printing Middle Ages for you. Richard is generally regarded as last Plantagenet Kings (going back to William the Conqueror), though the Tudor kings who replaced him seem also to be descended from a Plantagenet ancestor. Dynastic politics is complicated.

I also learned that the British royal family today still receives rents from lands bequeathed to English monarchs from the Plantagenet kings.

The history of the area of the dig, what medieval Leicester was like, is also interesting. In act the official reason for the dig was to explore the remains of an old religious establishment. And I did find the details of the dig itself, and what Pitts had to tell us about how archeology actually works in today's world, worth reading about. However, I was less interested in the story that follows the amazing discovery; none of the professionals thought they would find the grave of Richard III. The journalistic account of how various institutions, academic, governmental, media, etc. reacted was less compelling. Maybe these details about how the world works today are more interesting to English readers, who can bring their own experiences to the contemporary story. I suspect, however, that if America had kings to dig up, the resulting brouhaha would be truly appalling.

There will always be an English royalty. Saying this, I have to admit to being a devoted viewer of two recent TV series about English monarchs. (I like fiction too.)

Published on March 26, 2017 11:53