Robert Knox's Blog, page 27

September 18, 2017

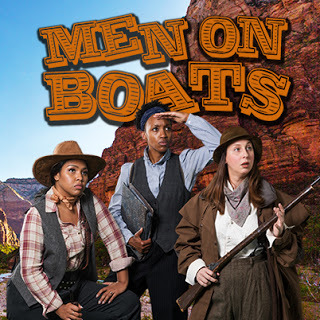

The Garden of American History: When the "Men on Boats" Are Mostly Women

How do you write a play about some historical event important in its time, of interest today because of its time, without the naive celebratory tone of the history textbook or a neo-Marxist condemnation of the entire enterprise on ideological grounds? And also without limiting your cast of characters to the brave, occasionally squabbling 19th century white men who did the deed? The SpeakEasy Stage Company's production of "Men on Boats" by Jaclyn Backhaus meets all those challengers. Directed by Dawn Simmons, the production fills the play's boats -- manned in 1869 by army veterans, adventurers, a lone English tourist (in over his head, so to speak) and led by a one-armed river-running specialist and Civil War casualty John Wesley Powell -- with a racially mixed cast of young actors and, mainly (eight out of ten), actresses. This bold casting choice means that the play is not merely a tale of what happened when Americans first succeeded in exploring the length of the Colorado River from Wyoming through the magnificently walled Grand Canyon. It's also a tale of who we are today, with women and African-Americans (and immigrants from everywhere else) doing their share, and then some, of rowing our boats and keeping us all afloat. The Powell expedition was a product of particular moment in American history. The four boats were carried by train from Chicago to a convenient disembarkation point in Wyoming in May of 1869, just two weeks after the Transcontinental Railroad was completed. Seven members of the expedition were Civil War veterans. Most of the crew was recruited by Powell among the mountain men he encountered en route to his starting point. Powell lost his right arm after being shot in the Battle of Shiloh in 1862. A professor of geology, he had explored rivers from childhood, rafting the Mississippi River and its tributaries. A scientist with a youthful sense of adventure that struck playwright Backhaus, who draws on Powell's journal for her play's factual basis, as remarkably and rather wonderfully childlike in a man who has seen and suffered from that worst of adult inventions, war. Her play's playful tone "sprung from a place of childhood" she discovered in his journal, the only preserved acciubnt of the expedition. "He taps into that kind of role," Backhaus states in an interview that appears in the SpeakEasy program notes, "because there's a natural childlike curiosity to wanting to know more about the world." When, as playgoers, we think of what to expect from a play about a historical event, we are likely to picture a few drawn-from-life figures in the role of the play's main characters, whose differing ideas or ambitions or world view or other conflicts will carry the plot toward some sort of crisis and resolution. But in "Men on Boats," the occasions of conflict between Powell and navigator William Dunn, are a secondary element, though they lead to a dramatic confrontation before theriver journey's triumphant conclusion. Instead, the piece's principal action and much of its charm lies in the crew's vigorously theatrical confrontation of a river we cannot see. Its spirit, humor, and the expression of that youthful wonder Backhaus found in Powell's journal lies in the cast's ability to make their characters transparent and their embrace of the challenge of riding a wild river play as a species of life-threatening fun. They are, in some sense, though danger threatens at every turn in the river, and hunger sticks in its own oar, kids on an truly excellent adventure. Interestingly, "Men in Boats" has been compared to "Hamilton," the interview tells us, because the racially mixed and mostly female casting raises the question of who gets to tell our country's stories. Backhuas says her play raises the question "What men and women and people do we want as part of our collective history?" Her play also provides for an encounter with local Native Americans, giving those who suffered from a white nation's drive to explore an entire continent -- their home before the Europeans came -- an opportunity to cast a cold eye on the "government" that sponsors this expedition. The chief take-away for the audience, to my mind, is the pure pleasure of experiencing a brilliantly imaginative theater piece delivered by a lively and talented young cast that manages to convey that childlike sense of wonder in a spectacular, death-defying journey.

How do you write a play about some historical event important in its time, of interest today because of its time, without the naive celebratory tone of the history textbook or a neo-Marxist condemnation of the entire enterprise on ideological grounds? And also without limiting your cast of characters to the brave, occasionally squabbling 19th century white men who did the deed? The SpeakEasy Stage Company's production of "Men on Boats" by Jaclyn Backhaus meets all those challengers. Directed by Dawn Simmons, the production fills the play's boats -- manned in 1869 by army veterans, adventurers, a lone English tourist (in over his head, so to speak) and led by a one-armed river-running specialist and Civil War casualty John Wesley Powell -- with a racially mixed cast of young actors and, mainly (eight out of ten), actresses. This bold casting choice means that the play is not merely a tale of what happened when Americans first succeeded in exploring the length of the Colorado River from Wyoming through the magnificently walled Grand Canyon. It's also a tale of who we are today, with women and African-Americans (and immigrants from everywhere else) doing their share, and then some, of rowing our boats and keeping us all afloat. The Powell expedition was a product of particular moment in American history. The four boats were carried by train from Chicago to a convenient disembarkation point in Wyoming in May of 1869, just two weeks after the Transcontinental Railroad was completed. Seven members of the expedition were Civil War veterans. Most of the crew was recruited by Powell among the mountain men he encountered en route to his starting point. Powell lost his right arm after being shot in the Battle of Shiloh in 1862. A professor of geology, he had explored rivers from childhood, rafting the Mississippi River and its tributaries. A scientist with a youthful sense of adventure that struck playwright Backhaus, who draws on Powell's journal for her play's factual basis, as remarkably and rather wonderfully childlike in a man who has seen and suffered from that worst of adult inventions, war. Her play's playful tone "sprung from a place of childhood" she discovered in his journal, the only preserved acciubnt of the expedition. "He taps into that kind of role," Backhaus states in an interview that appears in the SpeakEasy program notes, "because there's a natural childlike curiosity to wanting to know more about the world." When, as playgoers, we think of what to expect from a play about a historical event, we are likely to picture a few drawn-from-life figures in the role of the play's main characters, whose differing ideas or ambitions or world view or other conflicts will carry the plot toward some sort of crisis and resolution. But in "Men on Boats," the occasions of conflict between Powell and navigator William Dunn, are a secondary element, though they lead to a dramatic confrontation before theriver journey's triumphant conclusion. Instead, the piece's principal action and much of its charm lies in the crew's vigorously theatrical confrontation of a river we cannot see. Its spirit, humor, and the expression of that youthful wonder Backhaus found in Powell's journal lies in the cast's ability to make their characters transparent and their embrace of the challenge of riding a wild river play as a species of life-threatening fun. They are, in some sense, though danger threatens at every turn in the river, and hunger sticks in its own oar, kids on an truly excellent adventure. Interestingly, "Men in Boats" has been compared to "Hamilton," the interview tells us, because the racially mixed and mostly female casting raises the question of who gets to tell our country's stories. Backhuas says her play raises the question "What men and women and people do we want as part of our collective history?" Her play also provides for an encounter with local Native Americans, giving those who suffered from a white nation's drive to explore an entire continent -- their home before the Europeans came -- an opportunity to cast a cold eye on the "government" that sponsors this expedition. The chief take-away for the audience, to my mind, is the pure pleasure of experiencing a brilliantly imaginative theater piece delivered by a lively and talented young cast that manages to convey that childlike sense of wonder in a spectacular, death-defying journey.

Published on September 18, 2017 14:30

September 11, 2017

The Garden of the Seasons: Last weeks of Summer Still Do Their Best to Keep Us Outdoors

Warmer today, nearly the middle of September, than most of August was. Balmy here, catastrophic in Florida. That's the short-term of weather. Meanwhile the long-term march of climate shortens our days, brings apples and pumpkins to market -- and causes us to brood about the implications of a pair of unusually fierce storms. We brightened up the late summer flower garden this year with a Datura plant, whose intricate layered shades of deep purple and white-tending violet begin opening from the bud only after dark. By next morning the blossom is mostly open. The blossom opens more fully, revealing more of the internal layering over the next day or two at most, then swiftly decays. It's an event. The round, alien-looking seed pods left behind are striking as well. You can see a couple of them a little in the photo at the top of the page. I'm pretty much going to leave those seeds alone because they're poisonous, as are the flowers. Maybe that's why they're also called "devil's trumpets."

I suppose things with attractive surfaces and hidden dangers get that sort of name.

Along with the Datura we grouped some other annuals in pots in a flat, stonedust-covered space we call the patio extension; petunias, vinca, marigolds, cosmos, scaveola, whatever looked good in the garden centers (pictured in the fifth photo down). Among the perennials that bloom this time of year are anemone (second photo down). They put up with a lot of shade and keep blooming year after year. Having computer searched for pictures that look like what we're growing, I conclude that we have the Japanese Anemone, a "hardy, late summer to fall-blooming perennial."

Along with the Datura we grouped some other annuals in pots in a flat, stonedust-covered space we call the patio extension; petunias, vinca, marigolds, cosmos, scaveola, whatever looked good in the garden centers (pictured in the fifth photo down). Among the perennials that bloom this time of year are anemone (second photo down). They put up with a lot of shade and keep blooming year after year. Having computer searched for pictures that look like what we're growing, I conclude that we have the Japanese Anemone, a "hardy, late summer to fall-blooming perennial."

Not all of the plants we have bloom in the delicate pink color pictured here. Some have a classic robust pink flower. Others bloom almost completely white. Here's a grower's description of the Japanese Anemone: "Pale rose to mauve, 5-petaled, slightly cup-shaped flowers with distinctive yellow stamens rise on long, narrow, branching stems above basal growth of dark green foliage. Flower stems grow 2-3 feet tall by bloom time Prefers full sun to part shade and well-drained, fertile soil." (monticelloshop.org) This plant grows well in our region probably because it was found in China. Plants from North Asia do well in North America because the climates are similar. It was probably given the name "japonica" because that was the brand of choice among Western plant hunters in the 19th century. This flower came to the US in 1844.

Not all of the plants we have bloom in the delicate pink color pictured here. Some have a classic robust pink flower. Others bloom almost completely white. Here's a grower's description of the Japanese Anemone: "Pale rose to mauve, 5-petaled, slightly cup-shaped flowers with distinctive yellow stamens rise on long, narrow, branching stems above basal growth of dark green foliage. Flower stems grow 2-3 feet tall by bloom time Prefers full sun to part shade and well-drained, fertile soil." (monticelloshop.org) This plant grows well in our region probably because it was found in China. Plants from North Asia do well in North America because the climates are similar. It was probably given the name "japonica" because that was the brand of choice among Western plant hunters in the 19th century. This flower came to the US in 1844.

A plant authority from early in the last century, Harriet Keeler wrote, “the autumnal equinox comes and goes, but the Anemones bloom on, careless of threatening skies or pinching cold.” Actually some of our anemone plants started blooming in the middle of August. Usually our plants take turns blooming, extending their season, as our commentator noted, some weeks into official autumn.

A plant authority from early in the last century, Harriet Keeler wrote, “the autumnal equinox comes and goes, but the Anemones bloom on, careless of threatening skies or pinching cold.” Actually some of our anemone plants started blooming in the middle of August. Usually our plants take turns blooming, extending their season, as our commentator noted, some weeks into official autumn.

Other bloomers that bright up late summer are the red-flowering Sweet William, the third photo down. The Rose of Sharom (fourth photo), blooming pinkly against our flimsy fence. The garden fence plan (not "a wall") calls for a living fence of various shrubs filling in all interior and undoubtedly getting in each other's way. Two kinds of tall phlox are pictured in the sixth photo down. The plant with two-toned flowers is definitely a favorite.

Other bloomers that bright up late summer are the red-flowering Sweet William, the third photo down. The Rose of Sharom (fourth photo), blooming pinkly against our flimsy fence. The garden fence plan (not "a wall") calls for a living fence of various shrubs filling in all interior and undoubtedly getting in each other's way. Two kinds of tall phlox are pictured in the sixth photo down. The plant with two-toned flowers is definitely a favorite. The last photo yellow tansy flowers, a native wildflower in these parts. Behind it is the vegetable garden.

Published on September 11, 2017 14:08

September 6, 2017

The Garden of Verse: Matthew's Great Teaching on Charity and Hospitality, in an Age of Plastic

My poem on the difficult issue of living charitably and hospitably, as moral authorities such as the writers of the New Testament say we should, is appearing in the September issue of the online poetry journal, Verse-Virtual. The poem is titled "Food, Drink, Love" and responds to the often cited and beautifully phrased verse from the Book of Matthew in the New Testament. Here's the verse: "For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me." Matthew 25:35 I'll post the first four stanzas of my poem here:

Food, Drink, Love

If I were one for food and drink,

I'd never stop to mull and think

But fill the pail up to the brim

And bid good cheer to her and him

Now I keep nought of drink and food

For a plastic card is just as good

Its heart lies on a printed sheet

Accept this page, it's good to eat

Somewhere, my lad, your face I've seen

Perchance about the cash machine,

An oasis and a landscape green

With dates and palms and hands so clean

I knew you, Matthew, long ago

Your hair was long, your speech was slow

One of love's tribe, an innocent

Whose glory now is long since spent

If I were giving food and drink

I'd never have the time to think

For urchins with their empty cup

Would line my door to fill it up

To read the rest of this poem and other work by the 55 poets in this issue, see http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an...

The September 2017 issue of Verse-Virtual also includes one poem from my chapbook "Gardeners Do It With Their Hands Dirty," published in May. Here's the poem:

Waiting for the Perseids

No stars, but fire

And a guitar,

knock-knock-knocking on the soft diplomacy of clouds, visibility poor

A surge of smoke lunges like a ghost,

then twists back to the lake's black mirror

The weather worker builds a tapered temple of wood,

an offering,

draws flame from his hand

An instrument is procured for the master

The strings wind upward, songs

A few syllables hummed, rise to the diminished sky

From the dark below to the mottled cushion of the stars

The loon calls to the morning light

That chapbook, my first book of poems, is available from Finishing Line Press at https://www.finishinglinepress.com/pr...

Published on September 06, 2017 09:15

September 3, 2017

The Garden of Science: Climate is a Long-term Issue, Human Disaster a Short-Term Probability

Don't look now, but it appears likely that the human race is doomed. Having read "The Uninhabitable Earth" an article by climate-change explainer David Wallace Wells in a July issue of New York magazine, I am now able to put everything in perspective. Start with this so-called 'late summer' weather. A little cool, isn't it? Not my idea of real summer weather. Down in the sixties much of the time over for the last two weeks. And now that we're into mellow September, still three more weeks of summer technically according to the standard astronomical divisions of the solar-calendar, and I'm already looking around for key essentials in my winter wardrobe. Despite my desire to wind the seasonal clock back to the middle (or even beginning) of July and take these last two months over again, the worry is not that we've enjoyed (or tolerated) a cool summer, but that most of the world can look forward to warmer winters. In other words, warm is not good. This is counter-intuitive. I want to sit in nature's garden, sip something cold, and stare at the plants. Watch the sky. Track the many seemingly pointless (to us at least), patternless zigs and zags of the birds. Listen to the trees think. An occasional light breeze keeps the annoying insects off. The valuable, and intriguing insects, such as the honey bees are very welcome. I get photos of them every summer hopping in and out of big fact echinacea blooms and brushing against tiny bluish protrusions from the tips of the wild mint that joins the late summer crush around here. On my personal calendar August cannot have too many days. Quietly blessed and blooming afternoons slip into the hush of forever like a quiet nap. But too precious to sleep through. The cricket and cicada soundtrack of the early-starting evening. Not the songbirds calling end of day, but the humming appendages of largely invisible insects slipping into our consciousness from their undetectable hideouts. As the poets of Africa remind us: The grass is singing. But I'm living in the past. August serenades? Whoops, gones-ville. Now it's time for September songs. But apparently I am lamenting the wrong losses. The bigger story is that, temperature-wise, we're going up, up, up. And faster, and sooner, than we think. Wells's "The Uninhabitable Earth" has been fairly described as analyzing "worst-case scenarios," i.e., what is likely to happen to human life on earth if we do do nothing dramatic to contain our current greenhouse-gas emissions trajectory -- and, perhaps, even if we do. The article answers the question: how bad could it get? The answer: Bad. The issue for the continuance of human civilizatin, or mere survival of some fragment of the species, is the time-clock -- or time bomb -- that operates in the planetary system of which we are a mere jonny-come-lately. Here's my favorite quote, the fact I will try to remember, on taking the long-view of climate change on Planet Earth: The Earth has experienced five mass extinctions before the one we are living through now, each so complete a slate-wiping of the evolutionary record it functioned as a resetting of the planetary clock, and many climate scientists will tell you they are the best analog for the ecological future we are diving headlong into. Unless you are a teenager, you probably read in your high-school textbooks that these extinctions were the result of asteroids. In fact, all but the one that killed the dinosaurs were caused by climate change produced by greenhouse gas. The most notorious was 252 million years ago; it began when carbon warmed the planet by five degrees, accelerated when that warming triggered the release of methane in the Arctic, and ended with 97 percent of all life on Earth dead. We are currently adding carbon to the atmosphere at a considerably faster rate; by most estimates, at least ten times faster. The rate is accelerating.

Don't look now, but it appears likely that the human race is doomed. Having read "The Uninhabitable Earth" an article by climate-change explainer David Wallace Wells in a July issue of New York magazine, I am now able to put everything in perspective. Start with this so-called 'late summer' weather. A little cool, isn't it? Not my idea of real summer weather. Down in the sixties much of the time over for the last two weeks. And now that we're into mellow September, still three more weeks of summer technically according to the standard astronomical divisions of the solar-calendar, and I'm already looking around for key essentials in my winter wardrobe. Despite my desire to wind the seasonal clock back to the middle (or even beginning) of July and take these last two months over again, the worry is not that we've enjoyed (or tolerated) a cool summer, but that most of the world can look forward to warmer winters. In other words, warm is not good. This is counter-intuitive. I want to sit in nature's garden, sip something cold, and stare at the plants. Watch the sky. Track the many seemingly pointless (to us at least), patternless zigs and zags of the birds. Listen to the trees think. An occasional light breeze keeps the annoying insects off. The valuable, and intriguing insects, such as the honey bees are very welcome. I get photos of them every summer hopping in and out of big fact echinacea blooms and brushing against tiny bluish protrusions from the tips of the wild mint that joins the late summer crush around here. On my personal calendar August cannot have too many days. Quietly blessed and blooming afternoons slip into the hush of forever like a quiet nap. But too precious to sleep through. The cricket and cicada soundtrack of the early-starting evening. Not the songbirds calling end of day, but the humming appendages of largely invisible insects slipping into our consciousness from their undetectable hideouts. As the poets of Africa remind us: The grass is singing. But I'm living in the past. August serenades? Whoops, gones-ville. Now it's time for September songs. But apparently I am lamenting the wrong losses. The bigger story is that, temperature-wise, we're going up, up, up. And faster, and sooner, than we think. Wells's "The Uninhabitable Earth" has been fairly described as analyzing "worst-case scenarios," i.e., what is likely to happen to human life on earth if we do do nothing dramatic to contain our current greenhouse-gas emissions trajectory -- and, perhaps, even if we do. The article answers the question: how bad could it get? The answer: Bad. The issue for the continuance of human civilizatin, or mere survival of some fragment of the species, is the time-clock -- or time bomb -- that operates in the planetary system of which we are a mere jonny-come-lately. Here's my favorite quote, the fact I will try to remember, on taking the long-view of climate change on Planet Earth: The Earth has experienced five mass extinctions before the one we are living through now, each so complete a slate-wiping of the evolutionary record it functioned as a resetting of the planetary clock, and many climate scientists will tell you they are the best analog for the ecological future we are diving headlong into. Unless you are a teenager, you probably read in your high-school textbooks that these extinctions were the result of asteroids. In fact, all but the one that killed the dinosaurs were caused by climate change produced by greenhouse gas. The most notorious was 252 million years ago; it began when carbon warmed the planet by five degrees, accelerated when that warming triggered the release of methane in the Arctic, and ended with 97 percent of all life on Earth dead. We are currently adding carbon to the atmosphere at a considerably faster rate; by most estimates, at least ten times faster. The rate is accelerating. Earth abides; people not so much. I'm listening to Peter Kater's "River," a musical piece evoking continuity, as I read this piece over. Frankly, I need the solace. The part about how "carbon warmed the planet by five degrees (celsius)... and ended with 97 percent of all life on Earth dead" particularly got my attention. Because as Wells goes on to point out, a five degrees elevation -- in an accelerated time frame because human beings are supplying the big oomph to the 'natural' forces that control climate by sending temps up and down -- is well within the possibilities of our very own here and now 'rapid climate change' super-crisis. If we have been following the Paris climate change agreement story, even distantly, we may know that the goal of the international treaty is holding global warming to a 2 percent increase. Wells's article analyzes the consequences of 4 percent and 8 percent increases, arguing that climate scientists offer the general public only the most modest estimates of their current global warming projections because they don't want to freak people out -- or governments -- and frankly they don't want to face the backlash of climate-deniers. So, in fact, the idiot know-nothings who currently possess the White House and most of the US government are already succeeding in keeping the true picture of what climate scientists thing may be in store for us from the vast majority of non-scientists. Here is some of that truth: Now two degrees is our goal, per the Paris climate accords, and experts give us only slim odds of hitting it. The U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issues serial reports, often called the “gold standard” of climate research; the most recent one projects us to hit four degrees of warming by the beginning of the next century, should we stay the present course. But that’s just a median projection. The upper end of the probability curve runs as high as eight degrees — and the authors still haven’t figured out how to deal with permafrost melt...[The reports show] that temperature can shift as much as five degrees Celsius within thirteen years. The last time the planet was even four degrees warmer, Peter Brannen points out in The Ends of the World , his new history of the planet’s major extinction events, the oceans were hundreds of feet higher. Well there's another fact I may try to keep a grip on. Humankind may, relatively soon, be facing ocean levels "hundreds of feet higher." Yet in another part of his essay, Wells tells us that us rising sea level is merely one of many serious threats (such as "the end of food") humanity can expect to face. Here's where you can read the rest of this "worse than you think" analysis: http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/... I'll indulge in only one other scare-fact -- we're all familiar with 'scare-stories' (that's how certain 'media' manipulate consumers such as the little-brained thing in the White House). But here's another 'scare-fact' about climate: Climate-change skeptics point out that the planet has warmed and cooled many times before. But the climate window that has allowed for human life is very narrow, even by the standards of planetary history. That is to say, through most of Planet Earth's history, temperatures on Earth's surface have been too hot, or too cold, to allow for the presence of human beings dwelling here. In terrestrial terms we were always here on a short lease. Suddenly I find myself more interested in those seemingly wacko proposals to set up artificial living environments on other planets. The climate science projections Wells presents here are: what Stephen Hawking had in mind when he said, this spring, that the species needs to colonize other planets in the next century to survive, and what drove Elon Musk, last month, to unveil his plans to build a Mars habitat in 40 to 100 years. Mars? Some other so far undiscovered 'other' home for humanity to inhabit? Some other living space, that is, from which our descendants can remember us. Or try to forget.

If you're interested in hearing other voices on this subject, here's an article that takes issue with some of Wells's conclusions.... https://climatefeedback.org/evaluatio...

And here's an article that says he got his worrying forecast right:https://www.vox.com/energy-and-enviro...

Published on September 03, 2017 22:48

August 27, 2017

The Garden of Time: Poetry in the Prose of Banville's "Blue Guitar"

Superb prose poems crop up in the novels of John Banville.

Superb prose poems crop up in the novels of John Banville. In "The Blue Guitar," published in 2015 but which I have just recently got around to reading, Banville's narrator, the central figure as is so often the case in Banville's fiction, shares an account of his relational missteps, betrayals and self-deceptions. In a novel in which the narrator's self-analysis -- and self-absorption -- is in reality the work's central concern, Banville brings us to a moment of no particular dramatic import in which said narrator reflects:

I felt tired, immeasurably tired.... The wind keened to itself in a chink in the window frame, a distant, immemorial voice. When the time arrives for me to die I want it to happen as a stilled moment like that, a fermata in the world's melody, when everything comes to a pause, forgetting itself. How gently I should go then, dropping without a murmur into the void.

I felt tired, immeasurably tired.... The wind keened to itself in a chink in the window frame, a distant, immemorial voice. When the time arrives for me to die I want it to happen as a stilled moment like that, a fermata in the world's melody, when everything comes to a pause, forgetting itself. How gently I should go then, dropping without a murmur into the void. Focusing on the last sentence in this brief meditation we find a cogent response to one of the most famous, and oft-quoted, poems about facing death in modern times, namely (and you should all be shouting aloud where this observation is going by this point) Dylan Thomas's memorable poem about his father: "Do not go gentle into that good night." Thomas's poem fell, with considerable resonance, into the period of mid-century Western angst I am tempted to call "when everything was existential." The word 'existential' was used both to mean that everything that happened in life was meaningless and that any single moment, gesture, decision, or indecision in a human life was of singular, potentially turning-point importance. Absolutely everything: from deciding to join the French Resistance and risk a horrible death at the hands of the homicidal maniacs who have taken over your country, to the praiseworthy gesture of getting out of bed each morning to face another day in a life in which nothing could ever be known, understood, or valued with anything resembling certainty. Take a stance, Thomas's great poem urged: "Rage, rage, against the dying of the light." If the world had no meaning, if the universe might itself be the daydream of some cosmic cobra wrapped around the pachyderm upon which the spinning earth was mounted, if human life itself was a bad joke in which a poor player struts and frets his hour upon the stage before disappearing behind the eternal curtain -- as we must all inevitably do -- then did you not, poor Dylan Thomas's father, have cause enough to rail? But in the passage quoted above our hero -- Oliver?; Banville's narrator-protagonists seem to have forgettable names -- asserts that he would take the opposite tack, volunteering, as it were -- if only the universe would stop rumbling about and mumbling pointlessly to itself and achieve a moment of stillness -- to go "gently." He's a quitter, this brief soliloquy may suggest. Or a peace-maker. Or, perhaps, a peace-seeker. A figure of resignation, approaching some sort of wisdom, if only of the quietist sort. All he's asking is for the universe to -- 'pause' -- or hold a pause (that's the 'fermata') -- and he would step in to fill the silence with his own freely-accepted extinction. Is this a spiritually advanced attitude? (I ask a second time). A Christian (or even Buddhist) resignation? The acceptance of higher power? The stoicism of the ancient philosophers? Is it a breakthrough of sorts for a character who has confessed his faults, both grand and petty, given up a successful career as an artist, and run away from the consequences of an affair with a friend's wife. Or is it meant to be taken -- by the reader -- as yet another self-dramatizing pose. Not a frank self-confession of his life's failure, but a sort of self-ennoblement he wishes others to share. Banville's narrator, the lapsed painter, is a familiar type. Someone, generally male, who trades on the appearance of qualities he does not truly possess to get something he desires. So often that something is the favorable opinion of women. What sets this character apart from others of his type is that his narration has almost nothing good to say about himself. A central motif, introduced without particular emphasis, is that from boyhood he has been a unapologetic thief. Stolen items of no particular monetary value keep popping up in this story. When his partner in adultery, her marriage ruined and her infatuation replaced by the sad slap of reality, accuses him of stealing a book, the reader thinks, 'Oh no! Now he will be falsely accused of the sort of thing he actually did in his boyhood. Ironic!' But no -- incredibly -- he has stolen it! We now see (if we haven't before) that 'stealing' in this book is a metaphor for our narrator's theft of another man's wife. I wondered whether we should also apply that metaphor to issue of the narrator's successful painting career. Are we to think that he may be 'stealing' from the work of others? But no I don't think so. All artists, all writers, necessarily 'steal.' Or borrow, to use a politer term, from the work of others; or 'allude' to creations such as the language of a great poem. That 'gently' in the earlier quoted passage about a welcoming of death is a clearly intended allusion to Thomas's canonical poem. Am I stealing, Banville may be asking us in this moment, from a poem many of us know about a subject all of us must someday consider? As readers of what I certainly found to be a beautiful passage in a troubling book, do we need to think about the issue of literary borrowing? Not really. At least I didn't. The passage is music. It's beautiful. That's the reason the unusual word 'fermeta' rings true in this passage. It's a word taken from music that means holding a pause or note. Banville's evocation of our experience of the 'the world,' our human existence, is a kind of music. And at the right moment his narrator is willing to surrender everything to it. Even himself. I pause here to point out that I have not even mentioned the act of borrowing contained in the novel's title. The phrase 'blue guitar' is famously associated with Picasso's painting "The Old Guitarist," painted during that 20th century artist's ever-popular "blue period." And it is also associated, again no doubt because of the influence of Picasso, with a famous 20th century poem by Wallace Stevens, titled "The Man With the Blue Guitar," in which the poet states (among other things): You do not play thing as they are You play them on your blue guitar. I take back my earlier, hasty judgment that narrator-protagonist Oliver, a venial, self-centered, self-confessed evader of responsibility, has nothing good to say about himself. He has one thing. This passage is it.

Published on August 27, 2017 21:07

August 23, 2017

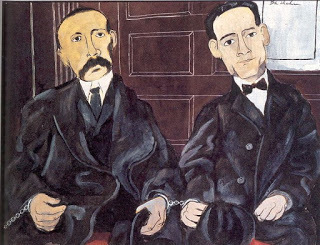

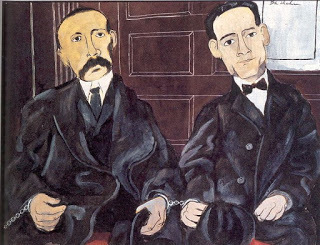

They Had "A Connection to the Case": Sacco and Vanzetti at 90

One of his ancestors was called to serve on the jury, a man told me. For one of those trials. He was at the gates when the getaway car went through, another man on another night told me of his family member's connection to the case. The words spoken with a rueful laugh. They didn't try to stop them. He told the police what he saw. So did a dozen other guys. "They all said different things." Her ancestor, a woman told me after my talk, was "a very well known doctor." At Harvard. "He was involved somehow in the case." She spoke quietly, as others filed out of the room. The name was McGrath. "The house was just down this way." He pointed to a part of West Bridgewater where an anarchist lived in 1920. Back then the 'house' was called Puffer's Place. Johnson's garage was still there too when he was growing up, the same person, a knowledgeable senior citizen, told me.Till some time in the Fifties, he thought. You could still see the sign: Johnson's Service Station. The woman stopped us as we came out of the Kingston senior center door. Is it over? she asked. She wanted to hear the author speak. I told her, happily, that I was the author. And, yes, the program was over, but I would gladly sell her a book if she had come to buy one. We spoke in the dark and I gave her my email address. Her family was connected to the case, she said. She gave me a name. Gardner. He worked for the Boston Globe too. He also worked for the defense committee, because they needed him when they began to get all that publicity. She told me who he was related to, and what he had done in the rest of his life after the case was over. I recognized the name, though his connection to the case was all I knew about him.

One of his ancestors was called to serve on the jury, a man told me. For one of those trials. He was at the gates when the getaway car went through, another man on another night told me of his family member's connection to the case. The words spoken with a rueful laugh. They didn't try to stop them. He told the police what he saw. So did a dozen other guys. "They all said different things." Her ancestor, a woman told me after my talk, was "a very well known doctor." At Harvard. "He was involved somehow in the case." She spoke quietly, as others filed out of the room. The name was McGrath. "The house was just down this way." He pointed to a part of West Bridgewater where an anarchist lived in 1920. Back then the 'house' was called Puffer's Place. Johnson's garage was still there too when he was growing up, the same person, a knowledgeable senior citizen, told me.Till some time in the Fifties, he thought. You could still see the sign: Johnson's Service Station. The woman stopped us as we came out of the Kingston senior center door. Is it over? she asked. She wanted to hear the author speak. I told her, happily, that I was the author. And, yes, the program was over, but I would gladly sell her a book if she had come to buy one. We spoke in the dark and I gave her my email address. Her family was connected to the case, she said. She gave me a name. Gardner. He worked for the Boston Globe too. He also worked for the defense committee, because they needed him when they began to get all that publicity. She told me who he was related to, and what he had done in the rest of his life after the case was over. I recognized the name, though his connection to the case was all I knew about him. A member of her family was one of the witnesses. I grew up on the street, she said. The case is special to me. I've always been interested in this subject, a man said. I've read about it. Anything about this case, another man said. I always want to come. I live in the shadow of the Plymouth Cordage Company. And look upon the chimney stack built by an ancestor of mine, daily. One of my husband's ancestors was a fish peddler too and told the story of meeting these men in North Plymouth, even on Christmas She said her grandmother never believed them. They said they were selling fish on Christmas. "But we never got any fish on Christmas," she said, so that's how she knew they were lying. He said they were terrorists. He said anarchists were responsible for bombings and killings all over the world. He said an anarchist even killed an American president. They killed the king of Italy. He said anarchists started World War I. Terrorists! How I could make them out to be victims? Later I looked for the name McGrath, which I recalled from my research, and found I was spelling it wrong. It was George Mcgrath. This is what I was trying to remember: The highly regarded medical examiner Dr. George B. Mcgrath performed the autopsy and said the four bullets fired into the body of payroll guard Berardelli were identical, hence fired from the same gun. This was a crucial point because the prosecution claimed that one of the bullets (called bullet number 3) was fired from a gun belonging to Sacco. The defense refuted this claim by pointing out that bullet 3 was a different kind of bullet from the other three, and therefore likely a substitution for the original bullet 3. Mcgrath repeated his testimony: the four bullets in the murdered man's body were of the same kind. This question is discussed at length in the book "Postmortem: New Evidence in the Case of Sacco and Vanzetti" (1985) by William Young and David E. Kaiser. "The custody of evidence was weak." I never found Puffer's Place, where the anarchist Mario Buda was living and from which he fled the local police. Or the house and garage of mechanic Simon Johnson, where Buda had left his car and where Sacco and Vanzetti, joined by Buda and a fourth anarchist, journeyed to pick up Buda's car on the fateful night when they fell into the Bridgewater police trap and were arrested. Held over night. Charged in the morning. Put on trial a year later; convicted. Executed seven years later in one of history's most infamous and long-running criminal cases. I found her family name on the witness list for the defense. The ancestor who did not receive fish for Christmas perhaps did not order any, since numerous other North Plymouth residents testified in court to receiving eels on Christmas Eve, a crucial piece of Vanzetti's defense in his Plymouth trial. The jury -- no immigrants, no people of Italian descent, no intellectuals, and no one who admitted to reading books; no African-Americans, and of course no women -- deliberated for 10 minutes before bringing back a verdict of guilty. The foreman said later that he didn't know if they were guilty of this crime but commented, "We oughta hang the whole lot of them." President McKinley was in fact killed by a professed anarchist, born here of Polish parentage. The assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, the proximate cause of World War I, was carried out by Serbian nationalists. Whether you consider it terror or not, political assassination has always been the weapon of the disenfranchised and it almost always backfires. But Sacco and Vanzetti were not on trial for a bombing or an assassination, but for a gangland style robbery of a shoe factory workers' payroll with accompanying murders, an act they would have regarded with horror and which they did not commit. The Globe reporter Gardner Jackson was hired by the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee in 1927 to manage publicity as the threat of execution grew near and the whole world was watching. After the executions Jackson gathered "The Letters of Sacco and Vanzetti" for publication in 1928, a lasting contribution to the case's history, since the collection still available today as a Penguin classic edition.

Published on August 23, 2017 09:54

The Garden of History: They Had a Connection to the Case: Sacco and Vanzetti at 90

One of his ancestors was called to serve on the jury, a man told me. For one of those trials. He was at the gates when the getaway car went through, another man on another night told me of his family member's connection to the case. The words spoken with a rueful laugh. They didn't try to stop them. He told the police what he saw. So did a dozen other guys. "They all said different things." Her ancestor, a woman told me after my talk, was "a very well known doctor." At Harvard. "He was involved somehow in the case." She spoke quietly, as others filed out of the room. The name was McGrath. "The house was just down this way." He pointed to a part of West Bridgewater where an anarchist lived in 1920. Back then the 'house' was called Puffer's Place. Johnson's garage was still there too when he was growing up, the same person, a knowledgeable senior citizen, told me.Till some time in the Fifties, he thought. You could still see the sign: Johnson's Service Station. The woman stopped us as we came out of the Kingston senior center door. Is it over? she asked. She wanted to hear the author speak. I told her, happily, that I was the author. And, yes, the program was over, but I would gladly sell her a book if she had come to buy one. We spoke in the dark and I gave her my email address. Her family was connected to the case, she said. She gave me a name. Gardner. He worked for the Boston Globe too. He also worked for the defense committee, because they needed him when they began to get all that publicity. She told me who he was related to, and what he had done in the rest of his life after the case was over. I recognized the name, though his connection to the case was all I knew about him.

One of his ancestors was called to serve on the jury, a man told me. For one of those trials. He was at the gates when the getaway car went through, another man on another night told me of his family member's connection to the case. The words spoken with a rueful laugh. They didn't try to stop them. He told the police what he saw. So did a dozen other guys. "They all said different things." Her ancestor, a woman told me after my talk, was "a very well known doctor." At Harvard. "He was involved somehow in the case." She spoke quietly, as others filed out of the room. The name was McGrath. "The house was just down this way." He pointed to a part of West Bridgewater where an anarchist lived in 1920. Back then the 'house' was called Puffer's Place. Johnson's garage was still there too when he was growing up, the same person, a knowledgeable senior citizen, told me.Till some time in the Fifties, he thought. You could still see the sign: Johnson's Service Station. The woman stopped us as we came out of the Kingston senior center door. Is it over? she asked. She wanted to hear the author speak. I told her, happily, that I was the author. And, yes, the program was over, but I would gladly sell her a book if she had come to buy one. We spoke in the dark and I gave her my email address. Her family was connected to the case, she said. She gave me a name. Gardner. He worked for the Boston Globe too. He also worked for the defense committee, because they needed him when they began to get all that publicity. She told me who he was related to, and what he had done in the rest of his life after the case was over. I recognized the name, though his connection to the case was all I knew about him. A member of her family was one of the witnesses. I grew up on the street, she said. The case is special to me. I've always been interested in this subject, a man said. I've read about it. Anything about this case, another man said. I always want to come. I live in the shadow of the Plymouth Cordage Company. And look upon the chimney stack built by an ancestor of mine, daily. One of my husband's ancestors was a fish peddler too and told the story of meeting these men in North Plymouth, even on Christmas She said her grandmother never believed them. They said they were selling fish on Christmas. But we never got any fish on Christmas, she said, so that's how she knew they were lying. He said they were terrorists. He said anarchists were responsible for bombings and killings all over the world. He said an anarchist killed an American president. They killed the king of Italy. He said anarchists started World War I. Terrorists! How I could make them out to be victims? Later I looked for the name McGrath, which I recalled from my research, and found I was spelling it wrong. It was George Mcgrath. This is what I read: The highly regarded medical examiner Dr. George B. Mcgrath performed the autopsy and said the four bullets fired into the body of payroll guard Berardelli were identical, hence fired from the same gun. This was a crucial point because the prosecution claimed that one of the bullets (called bullet number 3) was fired from a gun belonging to Sacco. The defense refuted this claim by pointing out that bullet 3 was a different kind of bullet from the other three, and therefore likely a substitution for the original bullet 3. McGrath repeated his testimony: the four bullets in the murdered man's body were of the same kind. This question is discussed at length in the book "Postmortem: New Evidence in the Case of Sacco and Vanzetti" (1985) by William Young and David E. Kaiser. "The custody of evidence was weak." I never found Puffer's Place, where the anarchist Mario Buda was living and from which he fled the local police. Or the house and garage of Simon Johnson, where Buda had left his car and where Sacco and Vanzetti, joined by Buda and a fourth anarchist, journeyed to pick up Buda's car on the fateful night when they fell into the Bridgewater police trap and were arrested. Held over night. Charged in the morning. Put on trial a year later; convicted. Executed seven years later in one of history's most infamous and long-running criminal cases. I found her family name on the witness list for the defense. The ancestor who did not receive fish for Christmas perhaps did not order any, since numerous other North Plymouth residents testified in court to receiving eels on Christmas Eve, a crucial piece of Vanzetti's defense in his Plymouth trial. The jury -- no immigrants, no people of Italian descent, no intellectuals, and no one who admitted to reading books; no African-Americans, and of course no women -- deliberated for 10 minutes before bringing back a verdict of guilty. The foreman said later that he didn't know if they were guilty of this crime but commented, "We oughta hang the whole lot of them." President McKinley was in fact killed by a professed anarchist, born here of Polish parentage. The assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, the proximate cause of World War I, was carried out by Serbian nationalists. Whether you consider it terror or not, political assassination has always been the weapon of the disenfranchised and it almost always backfires. But Sacco and Vanzetti were not on trial for a bombing or an assassination, but for a gangland style robbery of a shoe factory workers' payroll with accompanying murders, an act they would have regarded with horror and which they did not commit. The Globe reporter Gardner Jackson was hired by the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee in 1927 to manage publicity as the threat of execution grew near and the whole world was watching. After the executions Jackson gathered "The Letters of Sacco and Vanzetti" for publication in 1928, a lasting contribution to the case's history, since the collection still available today as a Penguin classic edition.

Published on August 23, 2017 09:54

August 19, 2017

The Garden of History: What if Your Heritage Is Hate?

The first time we drove through Virginia we could not help noticing, and being a little shocked by all the Confederate paraphernalia for sale in roadside stands. Confederate flags. Statues and statuettes of all sizes. Bumper stickers. The sign outside one such emporium established the rationale for all this merchandise to memorialize a failed secessionist rebellion: "Heritage, not Hate." You can try to convince yourself this is the case, but it's just not true. The Confederacy of States that sought to secede from the Union and set up their own slave-happy state was based, by its own account, on the belief of the racial superiority of white people to those of African ancestry; or, for that matter, to any people who did not appear 'white' to them. True, this was a widespread belief, back in 1861, not only in the American South but throughout North America and Europe. It was also a glaring contradiction to the philosophical basis of an Independent United States of America, as declared clearly, and for the ages, in the Declaration of Independence. "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal..." This was not a factual claim. It was a philosophical claim; what the study of logic calls a "major premise." When a proponent claims some point to be "self-evident," he is not arguing for it, he is drawing conclusions and implications from it. In terms of political philosophy, the statement 'all men are created equal and are endowed by their creator with the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" is, again, not a factual, scientific, or legal claim that is open to dispute. It is the basis for a social contract. Why are the English 'colonies' of North America entitled to declare their independence from the British crown and the British empire? Because, just like their English cousins, with whom they are 'created equal,' that have certain 'inalienable' rights -- including liberty. Inalienable means you can't take them from us. We can either choose to surrender our 'liberty' to you -- the British king -- or we can take it back and keep it for ourselves as the basis for a new social contract. Jefferson and the other signatories to the Declaration chose the latter. This reasoning, of course, creates a glaring contradiction when the status of African Americans held in slavery is considered. The only way to escape the logic of the Declaration of Independence is to contend that your slaves are not 'really' human beings. If they're not included in the phrase 'all men' ('men' in the 18th century meaning human beings), they they don't have a right to their liberty. However, no one knew better than slave owners themselves how undeniably and fully human their slaves were. If one population can mate successfully with another population, then they're all the same animal. Ask Thomas Jefferson for the answer to that question. Ask Sally Hemings. Ask Barack Obama's parents. So when certain slave-owning states declared their independence from the USA, their political theorists declared their own philosophical basis for creating a social union that was fundamentally different from the one they were leaving. Confederacy Vice President Alexander Stephens made this point very clear, right at the start in 1861. The United States, he said, had been founded in 1776 on "the false idea that all men are created equal." The Confederacy, by contrast, "is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and moral condition. This, our new Government, is the first, in the history of the world, based on this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth." There you have it, from the horse's mouth. So whatever Lee, Jackson and various other Southern "heroes" thought they were fighting for, they were in fact fighting for a bad cause. They were fighting for the preservation of slavery. And white supremacy. That's the "heritage" of the Confederate States of America, a mistaken idea now widely and accurately called "racism." So is that 'heritage' significantly different from 'hate'? Let's understand when and why those statues so may white people who today live in those states (and elsewhere) are so fond of were erected. They were erected around the turn of the 20th century -- the 1890s and the following decades -- at the same time the former Confederate states began to enact so-called Jim Crow laws designed to deprive Constitutionally freed population of former slaves and their descendants of equal rights -- that the monuments began to go up in public spaces. Jim Crow is the name given to the legal codification of segration -- separate white and black facilities. Separate schools, accommodations, bathrooms, water fountains. The formally legalized, institutionally superiority of white people: blacks go to the back of the bus. It happened when it did, more than a generation after the Civil War, two decades after the removal of the last US soldiers from the South, marking the end of Reconstruction, because Southern state governments recognized that Northern politicians were no longer interested in protecting the rights of black American citizens. Issues of class and money, unions, monopolies, Progressive legislation versus the oligarchic right to amass huge personal fortunes, now occupied the political parties who dominated the federal government. In the void created by the withdrawal of the federal government, Southern states were given a free hand to segregate African Americans and deny them civil rights and political rights such as the right to vote. A second wave of statues to the 'heroes of the Confederacy' went up during the Civil Rights era when state governments in the South were resisting pressures to desegregate schools and public facilities. To quote Southern Poverty Law Center, which documents the activities of hate groups and civil rights movements, "The civil rights movement led to a backlash among segregationists." (http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-cana...) The visceral hatred shown by many people in the South to Civil Rights activists and demonstrators has been pretty well documented. Anyone unclear about the blunt expression of hatred by whites in the South (and elsewhere) for Civil Rights advocates and integrationists is advised to view of any of the many documentaries on the period, including the recent film about Black author James Baldwin, "I Am Not Your Negro."

The first time we drove through Virginia we could not help noticing, and being a little shocked by all the Confederate paraphernalia for sale in roadside stands. Confederate flags. Statues and statuettes of all sizes. Bumper stickers. The sign outside one such emporium established the rationale for all this merchandise to memorialize a failed secessionist rebellion: "Heritage, not Hate." You can try to convince yourself this is the case, but it's just not true. The Confederacy of States that sought to secede from the Union and set up their own slave-happy state was based, by its own account, on the belief of the racial superiority of white people to those of African ancestry; or, for that matter, to any people who did not appear 'white' to them. True, this was a widespread belief, back in 1861, not only in the American South but throughout North America and Europe. It was also a glaring contradiction to the philosophical basis of an Independent United States of America, as declared clearly, and for the ages, in the Declaration of Independence. "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal..." This was not a factual claim. It was a philosophical claim; what the study of logic calls a "major premise." When a proponent claims some point to be "self-evident," he is not arguing for it, he is drawing conclusions and implications from it. In terms of political philosophy, the statement 'all men are created equal and are endowed by their creator with the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" is, again, not a factual, scientific, or legal claim that is open to dispute. It is the basis for a social contract. Why are the English 'colonies' of North America entitled to declare their independence from the British crown and the British empire? Because, just like their English cousins, with whom they are 'created equal,' that have certain 'inalienable' rights -- including liberty. Inalienable means you can't take them from us. We can either choose to surrender our 'liberty' to you -- the British king -- or we can take it back and keep it for ourselves as the basis for a new social contract. Jefferson and the other signatories to the Declaration chose the latter. This reasoning, of course, creates a glaring contradiction when the status of African Americans held in slavery is considered. The only way to escape the logic of the Declaration of Independence is to contend that your slaves are not 'really' human beings. If they're not included in the phrase 'all men' ('men' in the 18th century meaning human beings), they they don't have a right to their liberty. However, no one knew better than slave owners themselves how undeniably and fully human their slaves were. If one population can mate successfully with another population, then they're all the same animal. Ask Thomas Jefferson for the answer to that question. Ask Sally Hemings. Ask Barack Obama's parents. So when certain slave-owning states declared their independence from the USA, their political theorists declared their own philosophical basis for creating a social union that was fundamentally different from the one they were leaving. Confederacy Vice President Alexander Stephens made this point very clear, right at the start in 1861. The United States, he said, had been founded in 1776 on "the false idea that all men are created equal." The Confederacy, by contrast, "is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and moral condition. This, our new Government, is the first, in the history of the world, based on this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth." There you have it, from the horse's mouth. So whatever Lee, Jackson and various other Southern "heroes" thought they were fighting for, they were in fact fighting for a bad cause. They were fighting for the preservation of slavery. And white supremacy. That's the "heritage" of the Confederate States of America, a mistaken idea now widely and accurately called "racism." So is that 'heritage' significantly different from 'hate'? Let's understand when and why those statues so may white people who today live in those states (and elsewhere) are so fond of were erected. They were erected around the turn of the 20th century -- the 1890s and the following decades -- at the same time the former Confederate states began to enact so-called Jim Crow laws designed to deprive Constitutionally freed population of former slaves and their descendants of equal rights -- that the monuments began to go up in public spaces. Jim Crow is the name given to the legal codification of segration -- separate white and black facilities. Separate schools, accommodations, bathrooms, water fountains. The formally legalized, institutionally superiority of white people: blacks go to the back of the bus. It happened when it did, more than a generation after the Civil War, two decades after the removal of the last US soldiers from the South, marking the end of Reconstruction, because Southern state governments recognized that Northern politicians were no longer interested in protecting the rights of black American citizens. Issues of class and money, unions, monopolies, Progressive legislation versus the oligarchic right to amass huge personal fortunes, now occupied the political parties who dominated the federal government. In the void created by the withdrawal of the federal government, Southern states were given a free hand to segregate African Americans and deny them civil rights and political rights such as the right to vote. A second wave of statues to the 'heroes of the Confederacy' went up during the Civil Rights era when state governments in the South were resisting pressures to desegregate schools and public facilities. To quote Southern Poverty Law Center, which documents the activities of hate groups and civil rights movements, "The civil rights movement led to a backlash among segregationists." (http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-cana...) The visceral hatred shown by many people in the South to Civil Rights activists and demonstrators has been pretty well documented. Anyone unclear about the blunt expression of hatred by whites in the South (and elsewhere) for Civil Rights advocates and integrationists is advised to view of any of the many documentaries on the period, including the recent film about Black author James Baldwin, "I Am Not Your Negro." (see http://prosegarden.blogspot.com/2017/02/ ) If the determination to maintain legal superiority and social and economic power of one group of citizens over another -- to maintain the fiction we call "race," not to mention the fiction of innate superiority of one group over another based on the criterion of skin color -- is not a matter of "hate," what term would you prefer? What if your 'heritage' is hate? But, ah, those beautiful statues created as monuments to that noble race of traitors. It would be such a shame, the ignoramus in the White House laments, to tear them down. How can we bear to give them up? Third Reich architecture in Germany was also pretty impressive. How about all those statues of Lenin and Stalin the Soviets planted all over their conquered domains in Europe and Central Asia? Should we have worried about preserving them as well? And what piece of Iraqi history did we foolishly destroy by toppling the icons of Saddam? No statues yet to POTUS 45. I'd settle for consigning the thing itself to the dung heap of history, where he may join the images of his favorite white suspremacists.

Published on August 19, 2017 08:35

August 15, 2017

Garden of Verse: Singing the Catastrophic Climate Change Blues

It's still inconvenient. It's still the truth. If anything, more studies, more data, and more direct observation of the polar ice caps have only caused climate scientists to fast-forward their predictions of the catastrophic dislocations and probably disasters that rapid climate change will bring to human societies. Particularly crucial is the pace of sea-level rise.

Most of us, on encountering well-founded discussions of sea-level rise and other environmental impacts of climate change,

say, 'Wow, that's really true. That's really intense.' And go on living the way we've been living.

But how much accelerated coastal flooding will it take before those of us who live -- not simply on the seashore -- but somewhere near the coast... a category of the world's, and the USA's population, that proves to be a strikingly large percentage.... begin to realize that our governments will soon no longer be able to offer flood insurance at reasonable rates? When that recognition starts to settle in, that's the moment when either life styles start to change significantly; or humanity gives a colossal shrug and sighs, "Well, I guess it's really too late to do anything about it now."

Here's my shrug, written below in the form of a traditional blues song.

The poem appears in the August edition of Verse-Virtual.com. You can find some other poems by me and many poems by many other poets at http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an....

Ice Cap Blues

O, my temperature's rising

The kitchen fan's on the blink

My equanimity's oozing

I don't know what to think

If things don't get no cooler...

Gonna drown myself in the sink

Yeah the ice sheet is melting

And the temperature's zoomed,

But tell me, brother --

How does it help us if we know we're doomed?

O, the government's planning

They're gonna burn up some coal

They don't care if Paris is burning

Chill politics is the goal

Mister President don't know 'bout learning

He's got ice for his soul

Sure I know the ice sheet's melting

And the temperature's zoomed,

But tell me, brother --

How does it help me just to know we're doomed?

I'm going up to that Arctic

Where the weather is cool

Gonna find me a seal skin

Gonna chill in a pool

Don't sign me no more petitions

...Solo survival's the rule

Yeah I know the ice sheet's melting

And the temperature's zoomed,

But tell me, brother --

How does it help us just to we know we're doomed?

Published on August 15, 2017 20:41

August 8, 2017

The Garden of Verse: Seeing Things Fresh in the August 2017 Verse-Virtual

"I Could Write a Sonnet" Edmund Conti proposes in the August issue of Verse-Virtual, a phrase that sounds to me like a casual suggestion on the order of "I could run to the store" or "I could check the TV listings." But then his poem demonstrates that he not only 'could,' but in fact did in a poem that makes solid use of the given structure and delivers clever rhymes: "The waking up. (We thank the Lord for that!)

"I Could Write a Sonnet" Edmund Conti proposes in the August issue of Verse-Virtual, a phrase that sounds to me like a casual suggestion on the order of "I could run to the store" or "I could check the TV listings." But then his poem demonstrates that he not only 'could,' but in fact did in a poem that makes solid use of the given structure and delivers clever rhymes: "The waking up. (We thank the Lord for that!)The breakfast on the table. All non-fat." The poem pursues a theme that's both timeless and of moment: stay North or go South?

In his August group of poems Tom Montag offers reflections on seeing, and experiencing, what we always see, but seeing it new and living it fresh. Light and darkness are partners and intimates, his poem "How the Light" points out. It begins with these lovely lines " How the light

takes shadowand lays it

down gently" The poem concludes with a surprising and marvelous simile. Read it and see for yourself.

Ken Craft's vividly descriptive poem "Barnstorming the Universe" directs our attention to a familiar figure of the rural landscape and configures it anew with a fine image: "The white

paint, curly from reentry, looks

foolish as a washed cat." I don't know the last time I've thought about a washed cat. Yes, it looks foolish. In his poem "Provide, Provide," a farmer busy with his splitter reveals "the striated blond bellies of halved maple logs." One way or another I've seen a lot of split wood, but now I'll look again. A good poem always shows you something new.

Zen poetry-master Dick Allen shares a poem titled "Old Zen Master" in which the title figure reflects on the near invisibility of egg shells only to question what other unremarked wonders of the material universe he might easily have been blind to"like the tea-kettle whistle

at the end of the sound of 'Yes.'" I know I've missed that. Now I'll listen for it.

Joan Mazza's "Buzz" -- a title that offers the kind of buzzword the poem warns us against -- is a perfect storm of timely polemic. The poem contrasts the themes and terminology offered to us by the media 'buzz,' that nooz-room term for what commentators believe people are talking about (well, at least the people they talk to are) with subjects their time and attention would be better spent on:

"Don’t say moving forward

Don’t say pivot, fake news,

false flag. Don’t say migrants.

Don’t say, whatever, awesome.

Say Philandro Castile, Tamir Rice,

Sandra Bland, Trayvon Martin.

Say bees, bats, and butterflies.

Say clean water, clear skies."

I know I'm too predisposed to agree with the values inherent in this grouping of do's and don'ts to be an objective judge of how others may respond to this poem, but I would back any candidate whose platform includes the promise to "say bees, bats, and butterflies."

Firestone Feinberg's thoughtful and effective use of the extended metaphor in "Threads" results in a poem that addresses the fabric of ordinary life -- those "garments made of days/

Seemingly so comfortable and warm." The poem's arresting first line "The seams of life are not so tightly sewn" is likely to stay with all who read it.

Another poem brilliantly studded with arresting phrases takes up that subject the continuities of everyday life. David Graham's poem "My Monogamous Voice" draws its title from the "found phrase" of a student's malapropism. The student was apparently searching for the word "monotonous" but had misplaced it. "I am married to my mailbox,

toaster, windowscreens, and extra pillow," the poem's speaker tells us in his 'monogamous' voice. In a work dense with inventive phrasing, here's another wonderful example: "I am still/

on my first marriage to the music of what happens, and to grass, and pulling ticks from my hair,

and tiptoeing up a creaky set of stairs, careful

not to wake her." Just marvelous writing. Graham's short poem "My Hand" is an affecting evocation of a universal theme: our parents/ ourselves. A different sort of parental memory turns up in Donna Hilbert's concisely intense meditation "Friday Nights." The poet finds just the right words for a lasting depiction of a certain kind of human disaster in a memorable simile: "My father sat in his chair

like a storm sits on the horizon,

gathering flash and clap

to slam across the prairie." I love the awful flat monosyllabic intensity of that "flash and clap" Find all these poems and others in Verse-Virtual.com.http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an...

Published on August 08, 2017 07:57