Robert Knox's Blog, page 26

October 17, 2017

The Garden of Music and History: Tosca, Puccini, Napoleon and the Short-lived Roman Republic

I can sum up our recent Sunday afternoon at the opera -- the phrase doesn't quite have the ring of "night of the opera" -- in a single word: great.

I can sum up our recent Sunday afternoon at the opera -- the phrase doesn't quite have the ring of "night of the opera" -- in a single word: great.I have loved the music of Puccini's "Tosca" for years; and pretty much all of Puccini. Everything about the Boston Lyric Opera production was first rate, and clearly an opera company with the word 'Boston' in it (a rarity in recent decades) is extremely cheered by the strong reception its all-out staging of a 'big' classical opera has received from audiences, reviewers, and the city as a whole. World-class cities have opera; it's one of the requirements. Sunday's show was sold out, as was Friday night's opener at the Emerson Majestic Theater, a restored beaux arts theater that looks and performs perfectly for grand opera -- the musical genre in which the unaided human voice can fill every inch of a big hall.

The leads -- Elena Stikhina as Tosca, Jonathan Burton as her lover Cavaradossi and Daniel Sutin as the seriously despicable Scarpia -- were excellent both as singers and as actors. And the stage was inventively reconfigured to make space for a full orchestra (as opposed to a smaller 'pit orchestra'). Everything comes together in the quintessentially 'operatic' high point -- singing, lush orchestration, plot points, sacred setting and a thoroughly profane, confessional evil-dictator exulting by Scarpia -- of the emotion-wring "Te Deum"concluding the first act.

God is part of the plot line here. But as entrapped, devoutly Catholic Tosca asks in her heart-rending solo in the second act, where is he?

And then we come to the historical, real-world setting of "Tosca," a work based not on fable, myth, or romance, or even realistic fiction, but on a particular moment of history: Rome, in 1800, just after a great battle of Marengo, a crucial event in the Napoleonic Wars. The forces of the Roman church and state status-quo are rooting for Napoleon's defeat. The forces of liberty and modernity for his victory.

Blogging for the Boston Lyric Opera, Laura Stanfield Prichard describes 'Tosca' this way:

"A tempestuous tale of seduction, cruelty, and deception, this opera presents a fierce battle of wills set against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars."

Some reviewers have described its plot as "a political thriller."

Puccini based his work on an 1889 play by Victorien Sardou, whose surgeon grandfather served in Napoleon's army in Italy. Sardou wrote it for actress Sarah Bernhardt and the play proved a spectacular success at the box office.

In fact, the history of the Napoleonic era is all over this play. In the play's first scene the escaping political prisoner, Angelotti, re-introduces himself to onetime supporter Cavaradossi as the former premier "of the short-lived Republic of Rome." This was a government set up by the Revolutionary French Republic in 1798. The Army of the French Republic justified its wide-reaching campaigns of the 1790s as the liberation of other nations from absolutism, monarchy, hereditary social classes, and the tyranny of both church and state in the kingdoms of the Old Regime.

No unified country of Italy existed at this time. Rome was governed by the Pope, as were a collection of provinces called The Papal States. In much of the country the dominant power was the Austrian Empire. When the Army of the Republic defeated the armies of Austria, its ancien regime allies and the various kingdoms of Italy, it set up satellite states with new pro-French regimes. (It also took a captive Pope to France.) The new Roman Republic promptly absorbed the neighboring Papal States and claimed authority over a fair-sized chunk of the middle of the Italian peninsula.

But when the French army withdrew, most of these new regimes lacked enough local support to stay in power. In Rome an invasion from Naples overthrew the 'short-lived' republic, put the republicans like Angelotti in jail, and enlisted provincial bullies such as Scarpia to run the city as a police state. Torture, show trials, political executions, extortion, corruption. We're familiar with this apparatus from the bad times and places of the 20th and 21st century.

The situation remained fluid in the fragmented Italian peninsula. And Napoleon was still in the picture. When a fresh coalition of anti-republican states was formed against France, Napoleon again took command of The French Army of Italy (such a geographical name) and carried the war to the Austrians in the Alpine region.

The decisive battle of Marengo in the Piedmont region of Italy is the "victory" reported to Scapia and his reactionary government in the first act of "Tosca." In fact 'early reports' from the battlefield would have given the edge to the Austrians. Napoleon had divided his army, based on false reports of enemy intentions from a double-agent, and faced the Austrian attack with only a part of his forces. His commanders were able to give ground slowly and avoid a rout until later in the day when the rest of the French army arrived, positioned on the enemy's flanks. Under their unexpected attacks, the Austrians broke and fled.

A report of Napoleon's victory at Marengo arrives in the second act of the opera, causing the imprisoned Cavaradossi to rejoice. Whatever happens to him, this news seems to promise, revolutionary justice will win in the end.

The Battle of Marengo actually had bigger short-term consequences for Napoleon and France than it did for Rome. The decisive victory established Napoleon's popularity at home as the superstar who could do no wrong -- a path that led him a few years later to crown himself as Emperor.

Rome and the Papal States would see various regimes for more than half a century until they became part of the unified Italian Republic in 1870.

Great art depicts both individual tragedy and the ultimate triumph of forces greater than individuals -- love, heroism, and the arc of history. The only thing missing from the BLO's "Tosca" was a curtain call for Scarpia wearing a Trump mask.

Composer Giacomo Puccini based his Tosca on the 1889 play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou. He had seen a performance of it while working on Manon Lescaut (even Verdi was interested in it!), and was taken with the thriller. He began work in earnest in 1896, after asking his publisher Giulio Ricordi to wrangle the rights for Sardou’s play from Alberto Franchetti, another composer who worked with librettist Luigi Illica. A tempestuous tale of seduction, cruelty, and deception, this opera presents a fierce battle of wills set against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars. Conductor James Levine has described it as “Puccini’s glorious musical inspiration [combined] with the melodramatic vitality of one of the great Hitchcock films.” -- Laura Stanfield Prichard, blogging for the Boston Lyric Opera

http://blog.blo.org/finding-meaning-i...

Published on October 17, 2017 21:15

October 13, 2017

Garden of Literature: 'Petite Suites' for Readers with Big Appetites for Stories

Robert Wexelblatt, my poetry colleague at Verse-Virtual.com, where we both play the role of contributing editor, has published a new book a delicious, bite-sized stories under the musical title "Petite Suites."

Robert Wexelblatt, my poetry colleague at Verse-Virtual.com, where we both play the role of contributing editor, has published a new book a delicious, bite-sized stories under the musical title "Petite Suites."The author's "latest book," as the Boston University College of General Studies tellingly puts it in an article titled "Wexelblatt’s Petites Suites Stories Merge Music and Fiction," consists of "a series of charming, inventive short stories" about two or three pages long.

Wexelblatt is a professor humanities in the university's College of General Studies. The college newsletter article, a Q&A piece, gives Wex the opportunity to explain the origin of the collection and the reason for the musical titles. Here's his response to the question of how the inspiration from a musical structure

-- "short movements with loose thematic connections" — led to the storytelling.

Wex: "My object was to make a suite out of brief, brisk narratives resembling the movements of the French compositions that were my model. I gave each of the little stories in the suite fanciful but relevant musical titles, in French, and indicated the instruments that would perform them. I hoped the result would be an attractive hybrid of fiction and music. I was trying for something in fiction that would share some of the lively, tuneful, witty, and sardonic qualities of the little French suites that I see as ripostes to the serious, ponderous, solemn, sometimes bombastic and elephantine German music of the time. As Debussy’s or Fauré’s little suites are to, say, Wagner’s Ring or Bruckner’s symphonies, so these suites are to the five-hundred-page novel."

I have to acknowledge that, personally speaking, I tend toward the 500-page novel. (My novel "Suosso's Lane" is almost that long.) But I found these "suites" -- sharply, wittily written, quickly resolving -- a highly addictive reading experience. The structure plays out as compellingly as its musical inspiration. We're presented with a "hook" (or premise) -- I'm tempted here to borrow the Facebook phrase "fetching preview" -- followed in quick order by exposition, development, crisis, and resolution.

The structure never grows old, the stories never become predictable. In some cases the resolution -- as in the best fiction (and music? I'm not qualified to say) -- doesn't resolve. It may surprise, comment, or add a whole new level of complexity. Many of life's stories do just that. Sometimes characters behave the way we expect them to. Sometimes their choices show more wisdom than we expect of them. These are particularly satisfying because then we readers are learning something new as well.

Here is Wex's discussion of his use of the French, quasi-musical titles for his 'suite' stories.

Wex: "My model for the titles is Erik Satie, a composer who excelled at fanciful titles. Here are some translations: 'Sketches and Snares of a Large Wooden Fellow,' 'Dried-out Embryos,' 'Three Pieces in the Form of a Pear,' and the charming 'Sonatine Bureaucratique,' which needs no translation. I wanted titles that were similarly unexpected, fanciful, and amusing but at the same time revealing about the stories they head..."

You can find the article here: https://www.bu.edu/cgs/2017/09/22/wex...

I'll close by cribbing a bit of the 'advance review' (or blurb) I wrote after reading the book in proof copy:

The author’s fertile imagination offers scenarios, sketches, and movements for the mind on every theme and subject under the sun, families, artists, presidents for life, almost lovers, fading lions and hungry cubs. While the themes are stated with a musical precision, developments come smartly and the resolutions are sure and often subtle. A banker who knows where the bucks are hidden prevents a war. A GPS becomes the voice of wisdom. Odysseus confronts a different sort of fidelity.

I attempted in those comments to suggest the truly impressive range of the author's imagination. While his story structures reveal a pattern, this world-inside-the-covers-of-a-book takes us just about everywhere.

Here's a link to thing in itself:

http://www.blazevox.org/index.php/Sho...

Published on October 13, 2017 15:27

October 12, 2017

The Garden of Verse: A World of Gratitude in a Harvest of New Poems -- October's Verse-Virtual

It's harvest season. Here's a harvest of offerings from the October 2017 edition of Verse-Virtual.com.

As Joan Mazza's poem "Before the first bite" reminds us, when the harvest brings us to table,

Pause to see the colors

in front of you. Reflect

on those who grew

this wheat and ground

its heart, turned semolina

into pasta. Who tends

olive groves, presses

the fruit into oil, bottles it.

Grazie."

The poem's fine dining vocabulary, its active verbs (tends, presses, bottles) and compressed lines work together to focus our attention on the ides of gratitude. It's a good season for it.

On a similar theme, gratitude to the "ordinary saints" who serve us, both mind and body, is always in season. Joan Colby's fresh supply of praise poems for oft-overlooked occupations introduces us to facts about these jobs and those who do them are either ignored (meaning I ignore them) or simply unknown (a similar declaration of ignorance here). Such as the farm worker:

"attaching the vacuum tubes

To the teats so the milk will flow"

A second poem reminds me, painfully, how we call on the "Saint Geek" to address "the blue screen of perdition" -- god, naming the devil! I have to cross myself after naming that one.

As for the manicurist, see these brilliantly apt lines:

"How you nail us

With a styled creation

To indemnify against an

Onus of manual labor."

The onus is on us.

The cleverness of "You, Singular" by Edward Conti relies on its brief declaratives and witty rhymes. Its lyrics evoke not only singularity, but childhood, as in the unexpected final line of this stanza:

"You can make fun of me

I hope you do.

There’s only one of me.

How many are you?"

Only one, perhaps, but one can be more than enough. I also enjoyed the poem's reach into the "Thin Man" comedies to find an unexpected canine rhyme for "master." That line "I’ll be your Asta" may dog me for some time to come. And I'm grateful for it.

We're likely to find more than a measure of gratitude in Joe Cottonwood's "Autopsy of a Douglas Fir" as well. In the beautifully composed first stanza alone, the poem evokes not only the act of harvesting a tree, but the land, ecology and peoples of "three centuries of wooden wisdom."

"In your bleeding cross-section I count

three centuries of wooden wisdom

since that mother cone dropped

on soil no one owned.

Black bears scratched backs

against your young bark. Ohlone

passed peacefully on their path

to the waters of La Honda Creek."

I'm thankful also for the poem's introduction to me of the name "Ohlone," used for the surviving lineages of the indigenous peoples of the San Francisco Bay.

Gratitude for a certain kind of immortality is the theme of Marilyn Taylor's "The Day After I Die," expressed with a fine satirical eye.

"they will find the cure

for whatever got me,

and a unified theory

of physics will be announced

by a consortium

from M.I.T."

Those aren't the only wonders that will follow the demise of the speaker of this poem. Also predicted are answers to the age-old questions. Are we alone in the universe? What address do I plug into the GPS for the fountain of youth? The energy crisis? -- all resolved. Check out the final stanza for the greatest discovery of them all.

Alan Walowitz's moving poem "Anthony Peter Tumbarello" may remind us to be grateful for those who cross our paths in life, and keep re-crossing them. The poem tells the story of the poet's relationship with his childhood friend, and the cross "Tony" bore all his life, in a few perfectly chosen lines that pack a whole story into a sentence.

"When we walked

other kids would stare

and sometimes strangers’d

cross the street to inquire,Son, what’s wrong with your friend?

as if Tony couldn’t hear

for being so bent.

There's a world of tragedy in the stranger's thoughtlessly expressed inquiry, even if it was not ill-intended, and even if it was actually well meant. And a world of stubborn courage in Tony's response, delivered smartly at the end of this poem.

The title of Robert Wexelblatt's poem "Going to Bed with Jane Austen" has a ring of inevitability. We all go to bed from time to time with a favorite author. Where the poet takes this notion however is wholly original, satirical, revealing, and wise. A sort of compact novel in a concise lyric.

Something else that bedtime is good for, storytelling and its many uses, also comes in for an apposite nod (and wink?) -- "like that famous sultan, I finally fall asleep." A beautifully crafted poem.

My thanks, since we're handing out gratitude, also go Verse-Virtual's indefatigable editor Firestone Feinberg, who continues to put together such finely seasoned bounties of verse every month.

Find all these poems and others at http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an...

Published on October 12, 2017 21:34

October 11, 2017

The Garden of Literature: Walking With Thoreau

How can we let this year go by without doing something to recognize the bicentennial year of the birth of Henry David Thoreau? Apparently that year is more than three-quarters gone, while I am somehow under the impression that it is only just getting underway. I fear that events on “the national scene,” to use what now sounds like an antiquated phrase, have pretty much canceled 2017.

Can we get a do-over on this one?Nevertheless… Concord, Mass., the metaphysical heart of all things Thoreau, put together a website http://thoreaubicentennial.org/ with a full calendar of events around the town where the great American thinker lived and wrote, and where he spent the famous retreat in the woods along Walden Pond before discovering the necessity to go back to work in what most of us call, mostly by habit, the “real” world. In the great philosopher and writer’s case, he worked in his father’s pencil factory.Concord is surely ground zero for Thoreau commemorations. But we all can touch a little bit of the Thoreau legacy simply by talking a walk. Or reading pioneering works such as “Walden,” “Civil Disobedience,” or his essay about his favorite activity, “Walking.”My moment with Thoreau came this summer when I picked up a book published two decades ago that featured “Walden” in the title, “Walking Toward Walden” by John Hanson Mitchell. An ambitious intellectual project based on a physical challenge, the book attempted to evoke not only what Thoreau’s neighborhood was like back when he used to take daily walks in the woods outside of Concord, but also what it is like today — along with a fair representation of the Concord region before Europeans arrived in North America and in all the intervening eras since.Here is Mitchell’s take on the centrality of Concord and its role in Thoreau’s universe. “Drawn by the charismatic Ralph Waldo Emerson, who returned to his ancestral territory to live in 1834, other writers or thinkers began to visit or even settle in Concord so that by 1840, this small satellite of Cambridge and Boston had become the American center of intellectual activity.”Nathaniel Hawthorne, who referred to Concord as “Eden,” moved there in 1842, Bronson Alcott in 1848. Louisa May Alcott made the place a setting for “Little Women,” a pioneering publishing success. The poet Ellery Channing dwelled there. Feminist educator Margaret Fuller visited often to help prime the Transcendentalist pump.As for our famous prophet of simple living and love of nature, Mitchell describes him as “the sometime schoolteacher, pencil maker, surveyor and handyman named Henry Thoreau, whose oeuvre was all but unread until after his death in 1862.”Books about Thoreau are many. Books about walking his land are rare.When John Hanson Mitchell and his two eccentrically learned friends and traveling companions set out to walk from Westford, Mass. to Concord entirely through undeveloped land — in one day — the literary adventure goes forward but also backwards, with many frequent side trips into the major interests of the three hikers, their previous ventures together, and some references to their separate adventures as well. One of his companions knows everything about birds. The other knows — almost everything — about Native Americans. Mitchell knows Concords backwards and forwards and provides a mean recreation of the Revolution-sparking Battle of Lexington and Concord as well.Given that range of expertise, the book hangs together because of its concentration on to the unifying concept that was also at the center of Thoreau’s life and thinking, namely “the land.”Their single-day trek through land preserves, near impassable wetlands, over high bridges, through the backyards of new housing developments, and along dirt paths that once served long-gone farmsteads, succeeds in evoking a sense, however speculative, of what walking the land meant for Thoreau. We also learn what our contemporary three-some discover about the much-changed, much varied, and still-changing Concord region’s landscape. But even Thoreau himself was “passing through time” — that’s the way I’ve decided to think about it — when he walked the surrounds of beloved mid-19th century “Transcendentalist” Concord because the changes wrought by the European civilization planted there were already evident.The Colonial farms of an earlier day were being abandoned in Thoreau’s time. Farmlands that had been claimed from the wilderness at great cost — certainly in time and energy — in the 17th and 18th centuries had already been ‘farmed out’ by European methods. Their owners had headed west to find new lands to exploit, and the land left behind was going back (or had already gone back) to the wild. The abandoned fields were still far from the largely undisturbed old forest of the indigenous peoples displaced by the Europeans, but lots of land around Concord was heading in that direction. And in some parts of Mitchell’s journey, the same processes could be observed.In fact, pieces the landscape continue to go back and forth between development and reforestation. The book’s three travelers encounter shopping centers, factories, warehouses, railyards, technology think-tanks and corporate centers along Route 128 (“technology highway”). They pass through suburban subdivisions, protected wildlands with conservation restrictions in perpetuity, dried riverbeds and new wetlands. The beavers that disappeared before Thoreau’s time have now returned. As we know, more clearly than 20 years ago, deer are everywhere today.Thoreau observed the landscape changes of his own day, while celebrating what endures. What else Thoreau discovered on his daily walks includes — almost everything. Here’s how his famous essay “Walking” was described when it first appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in 1862. The author “explores: the joys and necessities of long afternoon walks; how spending time in untrammeled fields and woods soothes the spirit; how Nature guides us on our walks; the lure of the wild for writers and artists; and why ‘all good things are wild and free.’”(The essay is available today as a 60-page paperback. See https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/227113.Walking)Just reading words such as these makes me sad to realize that I cannot today leave my door and achieve by foot in any reasonable time frame “the lure of the wild.” I suspect that even on my best days I could not have kept pace with Thoreau’s habitual walks.How much philosophical weight Thoreau put on walking can be seen in statements such as these from his essay “Walking.”“We should go forth on the shortest walk, perchance, in the spirit of undying adventure, never to return; prepared to send back our embalmed hearts only, as relics to our desolate kingdoms. If you are ready to leave father and mother, and brother and sister, and wife and child and friends, and never see them again; if you have paid your debts, and made your will, and settled all your affairs, and are a free man; then you are ready for a walk.”

Can we get a do-over on this one?Nevertheless… Concord, Mass., the metaphysical heart of all things Thoreau, put together a website http://thoreaubicentennial.org/ with a full calendar of events around the town where the great American thinker lived and wrote, and where he spent the famous retreat in the woods along Walden Pond before discovering the necessity to go back to work in what most of us call, mostly by habit, the “real” world. In the great philosopher and writer’s case, he worked in his father’s pencil factory.Concord is surely ground zero for Thoreau commemorations. But we all can touch a little bit of the Thoreau legacy simply by talking a walk. Or reading pioneering works such as “Walden,” “Civil Disobedience,” or his essay about his favorite activity, “Walking.”My moment with Thoreau came this summer when I picked up a book published two decades ago that featured “Walden” in the title, “Walking Toward Walden” by John Hanson Mitchell. An ambitious intellectual project based on a physical challenge, the book attempted to evoke not only what Thoreau’s neighborhood was like back when he used to take daily walks in the woods outside of Concord, but also what it is like today — along with a fair representation of the Concord region before Europeans arrived in North America and in all the intervening eras since.Here is Mitchell’s take on the centrality of Concord and its role in Thoreau’s universe. “Drawn by the charismatic Ralph Waldo Emerson, who returned to his ancestral territory to live in 1834, other writers or thinkers began to visit or even settle in Concord so that by 1840, this small satellite of Cambridge and Boston had become the American center of intellectual activity.”Nathaniel Hawthorne, who referred to Concord as “Eden,” moved there in 1842, Bronson Alcott in 1848. Louisa May Alcott made the place a setting for “Little Women,” a pioneering publishing success. The poet Ellery Channing dwelled there. Feminist educator Margaret Fuller visited often to help prime the Transcendentalist pump.As for our famous prophet of simple living and love of nature, Mitchell describes him as “the sometime schoolteacher, pencil maker, surveyor and handyman named Henry Thoreau, whose oeuvre was all but unread until after his death in 1862.”Books about Thoreau are many. Books about walking his land are rare.When John Hanson Mitchell and his two eccentrically learned friends and traveling companions set out to walk from Westford, Mass. to Concord entirely through undeveloped land — in one day — the literary adventure goes forward but also backwards, with many frequent side trips into the major interests of the three hikers, their previous ventures together, and some references to their separate adventures as well. One of his companions knows everything about birds. The other knows — almost everything — about Native Americans. Mitchell knows Concords backwards and forwards and provides a mean recreation of the Revolution-sparking Battle of Lexington and Concord as well.Given that range of expertise, the book hangs together because of its concentration on to the unifying concept that was also at the center of Thoreau’s life and thinking, namely “the land.”Their single-day trek through land preserves, near impassable wetlands, over high bridges, through the backyards of new housing developments, and along dirt paths that once served long-gone farmsteads, succeeds in evoking a sense, however speculative, of what walking the land meant for Thoreau. We also learn what our contemporary three-some discover about the much-changed, much varied, and still-changing Concord region’s landscape. But even Thoreau himself was “passing through time” — that’s the way I’ve decided to think about it — when he walked the surrounds of beloved mid-19th century “Transcendentalist” Concord because the changes wrought by the European civilization planted there were already evident.The Colonial farms of an earlier day were being abandoned in Thoreau’s time. Farmlands that had been claimed from the wilderness at great cost — certainly in time and energy — in the 17th and 18th centuries had already been ‘farmed out’ by European methods. Their owners had headed west to find new lands to exploit, and the land left behind was going back (or had already gone back) to the wild. The abandoned fields were still far from the largely undisturbed old forest of the indigenous peoples displaced by the Europeans, but lots of land around Concord was heading in that direction. And in some parts of Mitchell’s journey, the same processes could be observed.In fact, pieces the landscape continue to go back and forth between development and reforestation. The book’s three travelers encounter shopping centers, factories, warehouses, railyards, technology think-tanks and corporate centers along Route 128 (“technology highway”). They pass through suburban subdivisions, protected wildlands with conservation restrictions in perpetuity, dried riverbeds and new wetlands. The beavers that disappeared before Thoreau’s time have now returned. As we know, more clearly than 20 years ago, deer are everywhere today.Thoreau observed the landscape changes of his own day, while celebrating what endures. What else Thoreau discovered on his daily walks includes — almost everything. Here’s how his famous essay “Walking” was described when it first appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in 1862. The author “explores: the joys and necessities of long afternoon walks; how spending time in untrammeled fields and woods soothes the spirit; how Nature guides us on our walks; the lure of the wild for writers and artists; and why ‘all good things are wild and free.’”(The essay is available today as a 60-page paperback. See https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/227113.Walking)Just reading words such as these makes me sad to realize that I cannot today leave my door and achieve by foot in any reasonable time frame “the lure of the wild.” I suspect that even on my best days I could not have kept pace with Thoreau’s habitual walks.How much philosophical weight Thoreau put on walking can be seen in statements such as these from his essay “Walking.”“We should go forth on the shortest walk, perchance, in the spirit of undying adventure, never to return; prepared to send back our embalmed hearts only, as relics to our desolate kingdoms. If you are ready to leave father and mother, and brother and sister, and wife and child and friends, and never see them again; if you have paid your debts, and made your will, and settled all your affairs, and are a free man; then you are ready for a walk.”And of course the most famous Thoreau quote of all is his evergreen sentiment “In wildness is the preservation of the world.”No doubt we find it harder today to encounter the transformative experience of “the wild” Henry David Thoreau regularly attempted. But in almost any city, state or continent, in any phase of life, we can still open the senses, and the mind, and the heart, to the “wildness” of the natural world. We may not be "walking toward Walden," but we can go a little way toward “preserving the wild.”

Published on October 11, 2017 14:06

October 10, 2017

The Garden of Stories:Haruki Murakami "MenWithout Women" -- Great Title, So-So Book

Haruki Murakami's "MenWithout Women" published this year in the US consists of stories in which not all that much happens, but what has happened is mulled over obsessively before either an unexpected event or, in most cases, nothing much at all happens to conclude the piece. It's not a good sign when, a week after finishing reading the book, I can't recall the events of the title story of this collection.

Haruki Murakami's "MenWithout Women" published this year in the US consists of stories in which not all that much happens, but what has happened is mulled over obsessively before either an unexpected event or, in most cases, nothing much at all happens to conclude the piece. It's not a good sign when, a week after finishing reading the book, I can't recall the events of the title story of this collection. The narrator laments, "We've become men without women," and I agree that's a truly horrible state to find oneself in, but I can't remember how it happened to this character. I do remember the final word, in this story, the final story in the collection, is "probably." That word is the leitmotif for the collection, his narrators across the stories use it repeatedly as they mull over events of the past, which is pretty much all they do. After analyzing some condition, or act, to death: offering thesis, critique of thesis, restatement of thesis, and concluding with an expression of belief that thesis is all that can be known of the matter under review, the whole business is then qualified with that most unsatisfactory of affirmatives, "probably." Because "probably" can only mean "possibly not." It's remarkable that Murakami can devote a whole book to stories in the key of "probably," but the lack of interesting development is a curious aesthetic choice, almost a stubborn decision to reign in the imagination, for an author whose unrestrained imagination has led to the grand, mythological novels his millions of fans worldwide adore. In my case, Murakami's "Kafka on the Shore" remains not a book I read, it's an experience. (I am currently having a similar 'experience' in the company of the novel "Jerusalem" by English novelist Alan Moore." I think of rare imaginative feats such as these as: 'the universe explained.') Perhaps an author capable of imaginative extravaganzas such as these needs to spend a few years, occasionally, walking around a familiar block in a familiar city, going over the same ground again and again in his head. Probably. The most imaginative leap in this collection is the story told by a female narrator of an adolescent crush that causes her to break into the house of the boy she is enamored of to steal articles from his room. It's psychologically acute. But nothing much develops from this premise. This is no more than to be expected -- probably. Most of these tales center on men who have for whatever reason one chance in life at a relationship that goes beyond sex -- there is plenty of emotionally detached sex in this book: can anything be more boring? -- and for whatever reason, it might not even be their fault, missed it. One character returns home early from a business trip and finding his wife in bed with a friend tactfully closes the bedroom door and moves out of his apartment. Is this a peculiarly Japanese response? I've looked it up, so here's how the narrator of that title story in "Men Without Women" explains what happened to his relationship with M. (that's all the name he gives her), the one woman in his life whose long-ago loss has condemned him to the dreary status of male-without-female. The narrator recalls: "But before I knew it, M. was gone. Where to, I have no idea. One day, I lost sight of her. I happened to glance for a moment, and when I turned back, she had disappeared." This is about the most disappointing piece of plot development one can imagine. It's a metaphor, not a story. At a polar opposite in aesthetic strategy, in the the most affecting of one of these stories -- the one about the man whose discovers his wife in bed with a friend -- the narrator, who has opened a small bar on a back street which he treats as a kind of hermit's retreat, develops a spot of trouble with local gangsters. He closes up one night and discovers snakes outside the bar, one of them curled up in a sidewalk tree. What happens to -- or because of -- those snakes? Nothing, in this little book. I'm looking forward to learning more about them, or their metaphysical equivalents, in a future 'big' book by Murakami. Probably.

Published on October 10, 2017 09:32

October 4, 2017

The Garden of the Seasons: When the Journey to the Sun Takes a Detour

Morning glories like the sun. Especially, as the name implies, in the first half of the day. To get closer to the sun they climb. They climb on whatever they can find, light pole, flag pole, nearby shrub or tree. If you put them along the wall of your house, they climb the wall. As a rule they need some sort of trellis, something they can wrap their viney claws ('tendrils,' I suppose) around.

Morning glories like the sun. Especially, as the name implies, in the first half of the day. To get closer to the sun they climb. They climb on whatever they can find, light pole, flag pole, nearby shrub or tree. If you put them along the wall of your house, they climb the wall. As a rule they need some sort of trellis, something they can wrap their viney claws ('tendrils,' I suppose) around. A few years back we tied strings from tacks in the wall to get them going. They do get going. Climb, baby, climb.

They're annuals. So you have to plant them from seed every year. Sometimes their seeds drop into a planter and they seed themselves.

They're annuals. So you have to plant them from seed every year. Sometimes their seeds drop into a planter and they seed themselves. A few years ago, when we had solar panels installed on the sunny half of our roof, a thin pipe protecting some sort of wiring was also installed to run from the hardware near the ground to the solar tap on the roof.

The climbing vines of the morning glory found that pipe a convenient stairway to heaven.

They are currently seeking the sun on the roof. Competition for the panels? I believe there is plenty of sunlight to go around.

They are currently seeking the sun on the roof. Competition for the panels? I believe there is plenty of sunlight to go around.This year, for the first time, a new route to the top attracted some of the vines.

We have old windows in most of our house. In the room I use for a home office, I lift the window on the hottest days of summer to let the breeze in. This requires pulling the screen down, lest the insect population discover a new habitat to explore for their possible benefit and our certain annoyance. And of course, lifting the storm window. Because of the imposition of a wide, hopelessly immobile writing table between my fingers and the window, I can only manage to lift the storm window a matter of inches, not feet.

We have old windows in most of our house. In the room I use for a home office, I lift the window on the hottest days of summer to let the breeze in. This requires pulling the screen down, lest the insect population discover a new habitat to explore for their possible benefit and our certain annoyance. And of course, lifting the storm window. Because of the imposition of a wide, hopelessly immobile writing table between my fingers and the window, I can only manage to lift the storm window a matter of inches, not feet. To lift it any higher would require extreme exertions such as climbing up on the desk and lying on my back with some portion of my anatomy, namely my head, stuck out the window. This would frighten the morning glories.

Or, perhaps, hanging by my feet from the ceiling so that I could get a natural purchase on the balky storm window and shove it the rest of the way up.

No matter. A six-inch screen exposure provides fresh air. And most days the inside window is closed.

No matter. A six-inch screen exposure provides fresh air. And most days the inside window is closed.This year, the first time ever, the morning glory vines found that gap.

They are now climbing, and blooming, in the inch or so of space between the lowered screen and raised storm window.

They are now climbing, and blooming, in the inch or so of space between the lowered screen and raised storm window.It's like having a greenhouse in the window of your home office.

The flowers that blossom in this space are of large size and a magnificent sky blue color.

I think, however, their ascent may have been stalled at this elevation unless they find a gap between storm window and frame sufficient to slip through. Perhaps they will be content to pack as much vine and leaf, plus occasional blossoms, into this protected space as possible.

Those I live with, however, have another explanation for this uncanny penetration of outdoor-growing plants into the indoor space occupied by yours truly.

They believe the flowers are coming in to get me. I trust their intentions are benign.

Published on October 04, 2017 08:27

October 2, 2017

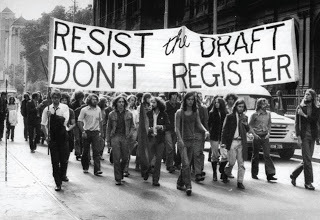

‘The War in Vietnam’ on the Homefront: Division, Resistance, A Bridge Too Far, and A Lesson in Self-Knowledge — My Story ‘Commitment’

"Commitment," a story based on my own fraught attempt at draft resistance during the Vietnam War, was published by the journal "3288 Review" two years ago. After watching most of the recent PBS documentary "The War in Vietnam," I decided to publish it again on Medium.com.

Ken Burns’ 18-hour “The War in Vietnam” was riveting TV, with previously unseen combat footage, a useful overview of American political history during that long and brutalizing war, and a commitment to let American veterans tells their own affecting stories. However — inevitably; no matter how long it was — the documentary left a lot out. The death and destruction inflicted upon the Vietnamese by ‘the American war’ was underplayed by a story that was much more about ‘us,’ not ‘them.’ Here’s a link to an article on that point https://theintercept.com/2017/09/28/the-ken-burns-vietnam-war-documentary-glosses-over-devastating-civilian-toll / The show also shorted the stories of the many young American men who chose — like Clinton, Bush, Trump, etc. — to avoid military service by any means available. And those of us, also many in number, who chose to confront the issue of whether to resist the war, rather than shelter in the privilege of deferment. I started off on that path, but found it hard to stay the course. Here’s the link to my story, titled “Commitment,” published on Medium:

https://medium.com/@rcknox2/the-war-i...

Published on October 02, 2017 10:01

September 25, 2017

The Garden of Nations: My Essay on Vanzetti in Plymouth Speaks Italian, Though I Do Not

My fascination with Bartolomeo Vanzetti's years in Plymouth, Mass. is going international. A version of an article I wrote more than a decade ago for a book about Plymouth history ("Beyond Plymouth Rock") has been published in the Italian language book "1927-2017 Sacco E Vanzetti." The essay appears under the title "L'indifferenza di Plymouth alla causa internationale." I don't read Italian. But last year, after "Suosso's Lane," my novel about Vanzetti's life in Plymouth, where he was living at the time of his arrest, was published, Italian editor and historian Luigi Botta asked me to contribute a piece for a collection of essays he was preparing in recognition of the 90th anniversary of the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti. I offered to trim the article I had written for the Plymouth history anthology to focus wholly on the attitude of the town's old guard to an internationally famous case involving one of its immigrant residents. I originally titled the piece "Trial of the Century: Local Amnesia," but the version need the word 'Plymouth' in the title. Hence the title that appears in the newly published volume, a thick paperback consisting of at least two dozen contributions by different authors. Needless to say, the case of the Italian immigrants who became international symbols of the oppression of the working class by rich and powerful, retains its hold on the Italian public, particularly those who share the general egalitarian orientation of the political radicals who died almost a century ago. I'm grateful to Senor Botta for including my work in this fine book. http://www.istitutoresistenzacuneo.it... I'm also grateful to the editors of two literary journals for including my work this work. My poem on "On Being Paris" is appearing in the first issue of a new literary journal called "Guinevere Revue." I wrote the poem almost two years ago, after the Charlie Hedbo shootings shocked the world. The poem points to terrorist attacks in third world countries, such as Lebanon, that did not receive the same attention or cause so many of us to pledge support. I'm happy to see the poem in print. The message, unfortunately, still applies.

My fascination with Bartolomeo Vanzetti's years in Plymouth, Mass. is going international. A version of an article I wrote more than a decade ago for a book about Plymouth history ("Beyond Plymouth Rock") has been published in the Italian language book "1927-2017 Sacco E Vanzetti." The essay appears under the title "L'indifferenza di Plymouth alla causa internationale." I don't read Italian. But last year, after "Suosso's Lane," my novel about Vanzetti's life in Plymouth, where he was living at the time of his arrest, was published, Italian editor and historian Luigi Botta asked me to contribute a piece for a collection of essays he was preparing in recognition of the 90th anniversary of the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti. I offered to trim the article I had written for the Plymouth history anthology to focus wholly on the attitude of the town's old guard to an internationally famous case involving one of its immigrant residents. I originally titled the piece "Trial of the Century: Local Amnesia," but the version need the word 'Plymouth' in the title. Hence the title that appears in the newly published volume, a thick paperback consisting of at least two dozen contributions by different authors. Needless to say, the case of the Italian immigrants who became international symbols of the oppression of the working class by rich and powerful, retains its hold on the Italian public, particularly those who share the general egalitarian orientation of the political radicals who died almost a century ago. I'm grateful to Senor Botta for including my work in this fine book. http://www.istitutoresistenzacuneo.it... I'm also grateful to the editors of two literary journals for including my work this work. My poem on "On Being Paris" is appearing in the first issue of a new literary journal called "Guinevere Revue." I wrote the poem almost two years ago, after the Charlie Hedbo shootings shocked the world. The poem points to terrorist attacks in third world countries, such as Lebanon, that did not receive the same attention or cause so many of us to pledge support. I'm happy to see the poem in print. The message, unfortunately, still applies.This journal does not have an electronic edition. For anyone interested in this new lit mag here's a link on Amazon: https://www.createspace.com/6711436

You can also read the poem here at: http://prosegarden.blogspot.com/2015/...

Finally, my short story about troubling days for a substitute high school teacher is up on the online journal "Beneath the Rainbow." The editors of this attractive online journal did a great job designing a page for the story and were very generous with space for a bio, including publication information and book cover photos. Here's the link:

http://beneaththerainbow.com/back-to-...

Published on September 25, 2017 21:52

September 22, 2017

The Garden of History: Vikings, Saxons, Christians Versus Barbarians, and Why What Happened in the Ninth Century Meant So Much For All of Us English Speakers Today

Speak to me not of thrones. Speak to me of Vikings. It’s the stories that matter. Stories teach us. They always have. So forget about endless wars, conspiracies and power rivalries by ruthless wannabes in Throne land — I bet you thought I was talking about D.C. — and learn about the stories that mattered. I’m talking about “The Last Kingdom.” Here’s the history behind what has become my favorite series in the era of Binge TV. Way back in the 9th century AD (habitually called ‘the Dark Ages’) the North men, or Norse — those traders, pirates and raiders who hailed in the lands we now call Scandinavia and are generally known today as Vikings — were well established in the northern part of England. In the latter part of that century fresh waves of raiders and invaders from the continental North, whom Saxon England simply called “the Danes,” began attacking the Christianized Saxon kingdoms of the relatively wealthy south of England. East Anglia, the southeast of England (where Danish influence is still felt today), fell to a Danish warrior king who then quickly moved against Mercia, the ‘heart of England.’ When Mercia, including London, fell as well, Wessex knew itself to be “the last kingdom” of the island’s seven kingdoms still under Saxon rule. After some four centuries of “owning the ground” (by Winston Churchill’s count)* the Saxons faced the prospect of losing the upper-hand in their country and possibly even extermination. Ninth century Saxons were well are that their own ancestors gained control of England (along with the Angles, who gave their name to the language and the country where it was spoken) in the same way the Danes were now doing it: raids, then full-scale invasions, then settlement. What happened next was the emergence of England’s true national hero, Alfred the Great. (St. George, for the record, is a fiction borrowed from the Middle East. King Arthur is a wonderful mythic — as opposed to historically founded — hero who supposedly rallied the Celtic Britons to fight off the then-barbarian Saxons while representing all that was noble in a lost age. The Britons’ struggle proved unsuccessful.) Alfred, one of whose most attractive qualities is his creation of the county’s first ‘library’ through his collection of scrolls containing reports assembled from intelligence agents throughout the country, managed to unify Saxons from all the kingdoms to stand against the fearsome invaders and persevere their nation in a lengthy struggle. At a low point in this struggle, after a surprise attack scattered his forces and deprived him of his capital ‘city’ (wooden huts within a surrounding wall), Alfred hid from the Danes in the marshes and was presumed dead. Recovering health, he put out a call for all men of England to rally at a point known to them, less apparent to the Danes, and his reputation proved sufficient to bring an army together on the spot. He then maneuvered the Danish warrior kings into a single defining battle on the plain of Ethandum and defeated them in the year 878 AD. That’s a long time ago. We know of these dates, and these events, because Alfred began the practice of instructing scribes to write down what happened. This victory did not permanently end the Danish threat and the island remained divided for much of a century between English rule and Danish rule (a region termed the Danelaw), but the England we recognize today — and the English language, which I confess is the single biggest point for me — was preserved from a worse fate by the actions of a single, outstanding leader. I can’t think of many other such examples. Rome fell. Ancient Greece faded. The United States was the product of a generation of gifted leaders. The story of how Alfred the Great saved England from Norse rule in those ‘dark’ early days is the story I expected to encounter in the BBC production and Netflix edition (which took over the second season) called “The Last Kingdom.” For anyone attracted by the challenge of depicting life in those hard to imagine “dark ages,” that seemed more than enough of a story. But then I didn’t know anything about a warrior called Uhtred, son of Uhtred, of Bebbanburg, who proves to be central figure in “The Last Kingdom.” That’s probably because he’s fictional. Perhaps he’s based on some actual figure of whom only fragmentary reports remain, or perhaps he is wholly the invention of the fertile pen of Bernard Cornwell, on whose historical novels this series is based. Either way, as the action hero of an historical saga, he’s a lord of attractions. First off, he’s an orphan. Orphans are unique, special cases, others. Lacking living parents and strong family connections, their survival is not guaranteed. They are self-made people by definition. Uhtred is the son of his town’s lord, a kind of minor king. When his father is killed by the Danes, Uhtred becomes the lost heir of a royal line: the click bait of a thousand romance tales. Shakespeare would have liked this plot. Further, he’s both Saxon and Dane. Born Saxon in Bebbanburg, in the nation’s unsettled north, he’s baptized as Christian, but determined from early boyhood to be a warrior. As the curtain opens on “The Last Kingdom,” a raiding party of Danes lands on the shore near his town and in a matter of a few minutes our hero loses his older brother (Bebbanburg’s heir apparent) and then sees his father and most of town’s fighting men mowed down in an open battle that shows the Saxons are no match for either the advanced tactics or fighting skill of the ferocious Danes. After this battle, Uhtred is taken as a slave by a prominent Danish warrior who raises him within his own family and comes to consider him a son. In this capacity, a Saxon who knows Danish ways, Uhtred arrives at Alfred’s court at just the right moment to advise him on how to meet the potentially fatal Danish threat. As Uhtred himself declares at the beginning of each episode: “Everything is destiny.” Uhtred is at liberty to play this role because at the dawn of his own brawny manhood, his adopted Danish family is slaughtered in a sneak attack by a rival warrior with a grudge. Yes, there are good Danes and bad ones. To its credit, this series takes a more nuanced view of its times and setting and characters of both nations than, I suspect, a straightforwarded hagiography of Alfred the Great — the story I initially expected — could have managed. And while “The Last Kingdom” is a story of kingship, it’s also a warrior’s story. Violence, revenge, sword fighting, long hair and beards, both cold and hot-blooded killing loom as the show’s themes and memes, and find play in in the story arcs that flow from its opening cries. Despite the often excessive, and sometimes distressingly casual bloodletting by barbarians (and Christians) wielding steel weapons against unarmored flesh, the show’s atmosphere seldom remains grim. In addition to being the archetypal gifted warrior (near-death escapes in every episode), our hero Uhtred has a sense of both humor and justice, an appreciation for women, and a bedrock loyalty to those to whom he is pledged likely to win emotional attachment from any viewer with a heart. And if we don’t wish our hearts attached, then why do we watch these things? Then, to add to its surface attractions, the show is landscaped in a beautiful unsullied England — green valleys and wooded hills (though the obsessive English gardening, I notice, hasn’t quite taken hold yet). The mood, among both Christians and pagans, is more often rough and ready rather than crude or nasty. Warrior-guys on both sides laugh a lot, tease each other, drink themselves silly, eye the women and are put in their place by them; while the leaders contemplate, plan, chronicle, and (in Alfred’s case) invent the use of the ‘letter’ as an effective means of communication. The main female characters are smart and capable, particularly the fighting nun who attaches herself to Uhtred’s most dangerous missions. And all this shouting, bonhomie, and bloody hand-to-hand combat serves the appealingly subversive notion of a ferociously embraced love of life, particularly evident in the Danes (who seem to accept their own will be short) and in our Saxon-born adopted Dane. The production even comes up with a weird, savagely sung and yodeled soundtrack that sounds to me absolutely like the world of our saga feels. All this works as entertainment and ‘story,’ but I make a case for the value of the history portrayed here as well. Though the Alfred depicted here is not always ‘good’ — his kingly virtues include a ruthless use of the few for the benefit of the many; and his Christian piety often comes across as ethical blindness, especially regarding the pagan Uhtred — his ‘greatness’ lay in saving a world of which we and many others are cultural inheritors. If Saxon England had disappeared into obscurity during the time of the Vikings, along with its laws, values, nascent civil society, infant institutions (such the ‘witan’ council, the seed of Parliament) and still forming language, I do not believe we would be better for it today. Admittedly, I cannot imagine what we would be. The United States of America, it is worth remembering, did not invent the world in 1789, despite out ceaseless clamor for ‘constitutional’ this and ‘founders’ that. This country, like all countries and all societies, owes its debts to the past. During Alfred’s time, at least in part because of his actions — and for that matter because of the Danish invasion — England had to get organized in order to survive. I believe that’s something this country is still trying to do.(*From “The Birth of Britain” by WinstonChurchill, 1956, Barnes and Noble edition.)

Speak to me not of thrones. Speak to me of Vikings. It’s the stories that matter. Stories teach us. They always have. So forget about endless wars, conspiracies and power rivalries by ruthless wannabes in Throne land — I bet you thought I was talking about D.C. — and learn about the stories that mattered. I’m talking about “The Last Kingdom.” Here’s the history behind what has become my favorite series in the era of Binge TV. Way back in the 9th century AD (habitually called ‘the Dark Ages’) the North men, or Norse — those traders, pirates and raiders who hailed in the lands we now call Scandinavia and are generally known today as Vikings — were well established in the northern part of England. In the latter part of that century fresh waves of raiders and invaders from the continental North, whom Saxon England simply called “the Danes,” began attacking the Christianized Saxon kingdoms of the relatively wealthy south of England. East Anglia, the southeast of England (where Danish influence is still felt today), fell to a Danish warrior king who then quickly moved against Mercia, the ‘heart of England.’ When Mercia, including London, fell as well, Wessex knew itself to be “the last kingdom” of the island’s seven kingdoms still under Saxon rule. After some four centuries of “owning the ground” (by Winston Churchill’s count)* the Saxons faced the prospect of losing the upper-hand in their country and possibly even extermination. Ninth century Saxons were well are that their own ancestors gained control of England (along with the Angles, who gave their name to the language and the country where it was spoken) in the same way the Danes were now doing it: raids, then full-scale invasions, then settlement. What happened next was the emergence of England’s true national hero, Alfred the Great. (St. George, for the record, is a fiction borrowed from the Middle East. King Arthur is a wonderful mythic — as opposed to historically founded — hero who supposedly rallied the Celtic Britons to fight off the then-barbarian Saxons while representing all that was noble in a lost age. The Britons’ struggle proved unsuccessful.) Alfred, one of whose most attractive qualities is his creation of the county’s first ‘library’ through his collection of scrolls containing reports assembled from intelligence agents throughout the country, managed to unify Saxons from all the kingdoms to stand against the fearsome invaders and persevere their nation in a lengthy struggle. At a low point in this struggle, after a surprise attack scattered his forces and deprived him of his capital ‘city’ (wooden huts within a surrounding wall), Alfred hid from the Danes in the marshes and was presumed dead. Recovering health, he put out a call for all men of England to rally at a point known to them, less apparent to the Danes, and his reputation proved sufficient to bring an army together on the spot. He then maneuvered the Danish warrior kings into a single defining battle on the plain of Ethandum and defeated them in the year 878 AD. That’s a long time ago. We know of these dates, and these events, because Alfred began the practice of instructing scribes to write down what happened. This victory did not permanently end the Danish threat and the island remained divided for much of a century between English rule and Danish rule (a region termed the Danelaw), but the England we recognize today — and the English language, which I confess is the single biggest point for me — was preserved from a worse fate by the actions of a single, outstanding leader. I can’t think of many other such examples. Rome fell. Ancient Greece faded. The United States was the product of a generation of gifted leaders. The story of how Alfred the Great saved England from Norse rule in those ‘dark’ early days is the story I expected to encounter in the BBC production and Netflix edition (which took over the second season) called “The Last Kingdom.” For anyone attracted by the challenge of depicting life in those hard to imagine “dark ages,” that seemed more than enough of a story. But then I didn’t know anything about a warrior called Uhtred, son of Uhtred, of Bebbanburg, who proves to be central figure in “The Last Kingdom.” That’s probably because he’s fictional. Perhaps he’s based on some actual figure of whom only fragmentary reports remain, or perhaps he is wholly the invention of the fertile pen of Bernard Cornwell, on whose historical novels this series is based. Either way, as the action hero of an historical saga, he’s a lord of attractions. First off, he’s an orphan. Orphans are unique, special cases, others. Lacking living parents and strong family connections, their survival is not guaranteed. They are self-made people by definition. Uhtred is the son of his town’s lord, a kind of minor king. When his father is killed by the Danes, Uhtred becomes the lost heir of a royal line: the click bait of a thousand romance tales. Shakespeare would have liked this plot. Further, he’s both Saxon and Dane. Born Saxon in Bebbanburg, in the nation’s unsettled north, he’s baptized as Christian, but determined from early boyhood to be a warrior. As the curtain opens on “The Last Kingdom,” a raiding party of Danes lands on the shore near his town and in a matter of a few minutes our hero loses his older brother (Bebbanburg’s heir apparent) and then sees his father and most of town’s fighting men mowed down in an open battle that shows the Saxons are no match for either the advanced tactics or fighting skill of the ferocious Danes. After this battle, Uhtred is taken as a slave by a prominent Danish warrior who raises him within his own family and comes to consider him a son. In this capacity, a Saxon who knows Danish ways, Uhtred arrives at Alfred’s court at just the right moment to advise him on how to meet the potentially fatal Danish threat. As Uhtred himself declares at the beginning of each episode: “Everything is destiny.” Uhtred is at liberty to play this role because at the dawn of his own brawny manhood, his adopted Danish family is slaughtered in a sneak attack by a rival warrior with a grudge. Yes, there are good Danes and bad ones. To its credit, this series takes a more nuanced view of its times and setting and characters of both nations than, I suspect, a straightforwarded hagiography of Alfred the Great — the story I initially expected — could have managed. And while “The Last Kingdom” is a story of kingship, it’s also a warrior’s story. Violence, revenge, sword fighting, long hair and beards, both cold and hot-blooded killing loom as the show’s themes and memes, and find play in in the story arcs that flow from its opening cries. Despite the often excessive, and sometimes distressingly casual bloodletting by barbarians (and Christians) wielding steel weapons against unarmored flesh, the show’s atmosphere seldom remains grim. In addition to being the archetypal gifted warrior (near-death escapes in every episode), our hero Uhtred has a sense of both humor and justice, an appreciation for women, and a bedrock loyalty to those to whom he is pledged likely to win emotional attachment from any viewer with a heart. And if we don’t wish our hearts attached, then why do we watch these things? Then, to add to its surface attractions, the show is landscaped in a beautiful unsullied England — green valleys and wooded hills (though the obsessive English gardening, I notice, hasn’t quite taken hold yet). The mood, among both Christians and pagans, is more often rough and ready rather than crude or nasty. Warrior-guys on both sides laugh a lot, tease each other, drink themselves silly, eye the women and are put in their place by them; while the leaders contemplate, plan, chronicle, and (in Alfred’s case) invent the use of the ‘letter’ as an effective means of communication. The main female characters are smart and capable, particularly the fighting nun who attaches herself to Uhtred’s most dangerous missions. And all this shouting, bonhomie, and bloody hand-to-hand combat serves the appealingly subversive notion of a ferociously embraced love of life, particularly evident in the Danes (who seem to accept their own will be short) and in our Saxon-born adopted Dane. The production even comes up with a weird, savagely sung and yodeled soundtrack that sounds to me absolutely like the world of our saga feels. All this works as entertainment and ‘story,’ but I make a case for the value of the history portrayed here as well. Though the Alfred depicted here is not always ‘good’ — his kingly virtues include a ruthless use of the few for the benefit of the many; and his Christian piety often comes across as ethical blindness, especially regarding the pagan Uhtred — his ‘greatness’ lay in saving a world of which we and many others are cultural inheritors. If Saxon England had disappeared into obscurity during the time of the Vikings, along with its laws, values, nascent civil society, infant institutions (such the ‘witan’ council, the seed of Parliament) and still forming language, I do not believe we would be better for it today. Admittedly, I cannot imagine what we would be. The United States of America, it is worth remembering, did not invent the world in 1789, despite out ceaseless clamor for ‘constitutional’ this and ‘founders’ that. This country, like all countries and all societies, owes its debts to the past. During Alfred’s time, at least in part because of his actions — and for that matter because of the Danish invasion — England had to get organized in order to survive. I believe that’s something this country is still trying to do.(*From “The Birth of Britain” by WinstonChurchill, 1956, Barnes and Noble edition.)

Published on September 22, 2017 19:31

September 19, 2017

The Garden of Verse: Ordinary Surprises, Metaphysical Stickers, and a Dream-Time Meeting in September's Verse-Virtual

These are some of the poems I enjoyed reading this month on September's Verse-Virtual. Robert Wexelblatt's affecting "Father and Daughter," a description presented with dreamlike clarity of a generational encounter that never took place. The details of the setting for the imagined meeting include

These are some of the poems I enjoyed reading this month on September's Verse-Virtual. Robert Wexelblatt's affecting "Father and Daughter," a description presented with dreamlike clarity of a generational encounter that never took place. The details of the setting for the imagined meeting include "...a wrought-iron bench that looks French,

dazzlingly white in a summer afternoon

saturated with sun. It could be a scene

from a technicolor film of a

Henry James garden party. The emerald

grass is smooth as a new pool table, not

one bald spot or weed." The scene is kind of paradise of lost possibilities. A visionary, moving poem. This poem also appears in the final story of Wexeblatt's new book of short fiction entitled "Petites Suites," just out from Blaze VOX. (Here's a link: https://www.amazon.com/Petites-Suites... ) The world of fathers and families also provides the material for Paul Brookes' "This Dad Never Only Considers," an account of a father's scrupulously systematic turn of mind that, we learn, is bequeathed to his son. The poet reveals, in a tonal mixture of confession and modest pride, "My dad and I bring the whole going on

to a brief stop as others

who wish to get on, hoot, cringe,

whistle and toot their dismay." I particularly like the fine run of edgy, cinematic of verbs "hoot, cringe, whistle and toot" in this stanza. I also admire the poem's long sentences, dotted with serial commas and subordinate modifiers, suggestive of the prose style of an earlier day.

Some writers like names. Some are phrase makers. An element of making and finding the comic and telling absurdities of our own days on the planet runs through Jefferson Carter's three September poems. In a poem about finding a wise "EAR" to tell your problems too, we read "So what if your third wife bought

a bottle of perfume called Shake It,

Shake It, Señora?" This piece of listening to the universe stops me short. Where can I find a bottle of perfume called "Shake it, Shake it, Senora"? I live too quiet a life. The poem titled "Sticker" begins by asking us how we imagine our prehistoric ancestors sitting around the campfire, and then to perform a similar hypothetical act of seeing our similarly reduced future selves. The poem concludes with the killer line: "Or did you imagine a sticker

on your war club, exhorting you

& your sleepy tribesmen to be kind?"

John Morgan's "November Surprise" depicts the emergence of a butterfly at what seems to be the wrong time of year in Fairbanks, Alaska, "ten below and ice-mist on the river." A butterfly in such circumstances inevitably assumes a large burden of meaning for a creature made almost of nothing. "Its wings," the poem tells,"like paisley, red and brown, quiver

as it paws the pane, embodiment of

summer in late fall." A beautiful piece of description. I leave the fine last line of this "November Surprise" unspoiled. Wings and weather take flight also in Kate Sontag's poem "Made of bee wings and the breath of sun” (the title attributed to V-V poet Michael Minassian). The poem conflates the "return" of a mother, two years departed, with the unseasonable presence of a wasp "appearing/

out of what winter crack in the world lightheaded?" Written in the high style of extended comparison, this poem reminds me (at least) of the poems of the Metaphysical school, elegant in tone and diction. Once again I'll leave the lovely concluding phrases for the reader to discover. I took considerable pleasure in reading Joan Colby's generous handful of "Ordinary Saints." What a great idea for a series of poems! For instance, "SAINT POSTAL CLERK," whose habits as enumerated by the poet are entirely familiar and yet have never struck me, the impatient customer-to-be, as anything but tedious -- one of those poor fellows evoked here: "Lines stamping with irritation as you calmly display

A catalog of offerings to the undecided." In "SAINT BARTENDER," the poet discover an embarrassment of verbal riches, similar to the bartender's own "forty eight kinds of Craft Beer." These oft-repeated acts of mixing and dispensing point to comparisons skillfully evoked in lines such as: "Saint of closing time

Stacking the glassware, standing like a priest

In the ornate mirrored altar... "

These are inspiring poems, these gifts of September, along with so many others. Here's a link to the issue: http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an...

Published on September 19, 2017 12:38