Robert Knox's Blog, page 23

February 23, 2018

The Garden of Wings: Episode of a Sparrow

I carry the bag of sunflower seeds by hand out to the feeder. A warm day, even by my soft standards. The first time I've felt that, said that, since I don't know when.

I carry the bag of sunflower seeds by hand out to the feeder. A warm day, even by my soft standards. The first time I've felt that, said that, since I don't know when. Approach the raspberry thicket, leafless all winter, to pass between the branches the ten feet or so to the feeder. I stop as the flutter of nearby wings scatters the local brunch crowd, the rhythm of small, brownish birds darting to the feeder, then darting back to the safety of densely branched, overgrown shrubs. But one of them heads the wrong way, landing on a bare raspberry cane a few feet away from me. One of the sparrows. Brown, as ordinary as a bird can be. Yet at this distance fascinating. I stand perfectly still. Then my eccentric bird hops-flies -- not away, but toward me -- to land on a bare horizontal-tending branch directly in front of my stomach, inches away from my body. Nearly touching me. I imagine myself a scarecrow. I am not a living creature to this bird. I cannot be, or he would fly away as his ancestors learned to do millennia ago, if they wished to go on being birds. Instead I am, perhaps, a shadow. A large, blank stillness, blocking his view in one direction. The bird adjusts its spatial orientation a little to one side, and then to another. It turns its constantly-scanning head to one side, and then to the other. As birds do. Watching for the signs. Watching to see how the others are moving. Or not. Or have hidden somewhere out of sight. The way all small birds seem to do, continually looking out. Where are the others? Where are the signals that would clue its next move. But though my bird moves his head continually, and I can see his greenish eye searching the world, he does not see me. He sees perhaps a wall. A grayish shadow. Perched on the horizontal branch, his tail feathers, angling one way and then the other, are about two inches from my fuzzy-clad stomach. I am tempted to extend a finger and touch those feathers. But I do not wish to frighten my wild visitor away. I watch its eyes as its head moves back and forth, I have never been this close to a bird in the wild. Its habitat, its world. Does this bird's vision have a blind spot? Not fatally, at least not yet, since it is alive. And in all other visible respects it appears to be identical to all the other sparrows who enjoy pecking at our feeder, and perching nearby, with great regularity. This is a 'special' bird, perhaps. Running, flying, surviving with its cohort. Mainstreamed with the flock. All the other birds give me the conventional wide berth when I approach their whereabouts. They are not pigeons, or domestic fowl, who might gather around a human feeder dispersing the seed. Still I am motionless. Still 'my' bird looks from side to side, but does not move away. I have never examined a bird at so minute a distance. I can see strands of brownish-color feather in wings that otherwise appear a single unified, feathered wing. Its color, for which I continue using the 'featureless' word 'brown,' reveals itself as a complex mass of variations in color. Intricate patterns. Lighter, darker, tan, black-brown; arrows, diamonds. Its perfect little head, the needle-sharp beak. And that unreadable eye that fails to see 'me.' I try to examine that eye for a flaw. Even at this range it's too small for a human eye to name its color, or parts. I sense something greenish, brighter than what I see at ordinary distances.It's still looking 'around' me. For something behind, or through, me. I'm not 'there' to it yet. As a creature. Something that moves and is best kept away from. I am tempted again to lift a finger, slowly, and try to touch this bird. But it seems more respectful to wait and watch what it does. It sweeps its head, yet again, from side to side. But nothing is moving in its world. Eventually it flies, or jumps -- the distance is so short that 'flies' doesn't seem the right word -- the three or four feet of distance to land on one of the feeder perches. Unmoving, I watch as its beak jams into the seed-hole and pulls out seed after seed. And then -- chews? The beak somehow grinds down on the sunflower shell sufficiently to loosen it. I have never observed this act closely enough to see this detail. Little bits of shell go flying out of the beak. Somehow that narrow tiny instrument is breaking the shell from the seed and discarding the chaff. It keeps pecking and eating. Left alone, it pokes and grinds. Is it hungry? Do birds' gullets know when they've had enough? Finally I cannot go on spoiling the natural sequence of events. What ordinarily happens is a bird abandons its feeder perch because another arrives too near. But nobody is coming now because I, the threateningly large creature, am standing there. I take a half-step toward the feeder. This movement apparently wakes 'my' bird to the presence of a large creature and it makes the swift and sudden leap and fly-away that I observe more often than I can count, day after day, all winter. My close encounter? A chance in a thousand?

Published on February 23, 2018 22:19

February 20, 2018

The Birds of Winter: Companions in All Sorts of Weather, Are they Harbingers of Change as Well?

We've seen cardinals in Massachusetts for years. Pretty much everyone does. At one time cardinals were a bird found widely in the South, but not in the Northeast. Bird feeders -- like us -- is one of the reasons the species was able to spread north. But so is the changing weather pattern. The last week is a good example.

We've seen cardinals in Massachusetts for years. Pretty much everyone does. At one time cardinals were a bird found widely in the South, but not in the Northeast. Bird feeders -- like us -- is one of the reasons the species was able to spread north. But so is the changing weather pattern. The last week is a good example.

As the first two photos on the left side suggest, cardinals (a female in the top picture), are extremely picturesque against New England snowfalls. But most winters snow comes and goes. Last Saturday night's snow was half melted by Sunday noon, and almost completely gone by Monday. Today's temperature topped off at a record-territory seventy. We used to call that an 'unseasonable' temperature -- but does that expression really make sense any more? As global warming makes our winters a little more welcoming for migrants from the south, it also causes more frequent and extreme fluctuations in weather conditions.

We see many egrets (top right) in Florida, where these wading birds are common. But we also see them in coastal New England, as in the photo here, enjoying a mild autumn afternoon in a salt marsh adjacent to Quincy's Wollaston Beach. Egrets often nest here in the summer; a few winter over along the estuarial waters of the Massachusetts shoreline.

We see many egrets (top right) in Florida, where these wading birds are common. But we also see them in coastal New England, as in the photo here, enjoying a mild autumn afternoon in a salt marsh adjacent to Quincy's Wollaston Beach. Egrets often nest here in the summer; a few winter over along the estuarial waters of the Massachusetts shoreline.  The chickadee in the next photo down has been a big fan of the bird feeder this year. They're quick to the feeder, competing with sparrows and other bigger birds, and quick to get out of the way when the next seating arrives. The chickadee's cousin, the Carolina chickadee, is reportedly on its way north.

The chickadee in the next photo down has been a big fan of the bird feeder this year. They're quick to the feeder, competing with sparrows and other bigger birds, and quick to get out of the way when the next seating arrives. The chickadee's cousin, the Carolina chickadee, is reportedly on its way north.  The perching bird with strong gray markings and a long tail (fifth photo down) is an occasional visitor. He stuck around recently long enough for us to try to identify him. Mockingbird is my best guess. Another relatively new Southern transplant, the mockingbird has sung in our summers fairly regularly, but if he's here this winter as well, that's a first.

The perching bird with strong gray markings and a long tail (fifth photo down) is an occasional visitor. He stuck around recently long enough for us to try to identify him. Mockingbird is my best guess. Another relatively new Southern transplant, the mockingbird has sung in our summers fairly regularly, but if he's here this winter as well, that's a first.  The osprey (seen perching above the nest) is not, to my knowledge, a winter visitor. This photo is from the end of last summer. Still, people build nesting platforms in Quincy and other towns these days to attract breeding pairs, and for the last three years, an osprey pair has found this one. The greatest number of osprey I've seen was in the shoreline preserves of St. Augustine, Florida.

The osprey (seen perching above the nest) is not, to my knowledge, a winter visitor. This photo is from the end of last summer. Still, people build nesting platforms in Quincy and other towns these days to attract breeding pairs, and for the last three years, an osprey pair has found this one. The greatest number of osprey I've seen was in the shoreline preserves of St. Augustine, Florida. I remember being told that the best time to see hawks was during the seasonal migrations. But in recent years I've encountered red-tailed hawks in all seasons. Some winters, though not this one, the encounters occur in the trees above our bird feeder. On one occasion, the "big bird" was simply standing in the middle of our neighbor's grassy lawn, a good perspective on the traffic around our feeder -- or maybe he was just tired. This year we hadn't seen one all winter, until a couple of weeks ago when we found him perched above, but not very high above, a walking trail in a city park. He saw no need to move as we stared for a while, then walked past him on the path. I stopped to take photos from both sides (I think this one was his better).

For really big birds, it's best to let them come to you. It's been a couple of years since the turkeys turned up on our street, but when they do it's always an occasion. Here they peck at a neighbor's lawn, looking for gleanings in the bare ground of a mild February week.

For really big birds, it's best to let them come to you. It's been a couple of years since the turkeys turned up on our street, but when they do it's always an occasion. Here they peck at a neighbor's lawn, looking for gleanings in the bare ground of a mild February week. I won't call it 'unseasonable.' Half of Boston was wearing shorts today.

Published on February 20, 2018 21:13

February 18, 2018

Garden of Death: Slaughter of the Innocents, Cheered on by Corrupt Gun-Loving Rulers

My poem on a nation's complicity in the unchecked serial murders of its young.

My poem on a nation's complicity in the unchecked serial murders of its young. Slaughter of the Innocents, Cheered on by Corrupt Gun-Loving Rulers

Nation of shame Monument of hate Begetter of falsehoods Despoiler of truth Bringer of early death Child-killer, Love-stealer, blood-spiller Eater of death, Denier of life, Destroyer of hope Extinguisher of the flame of life, Bringer of ash, Digger of graves Consumer of all that is good and kind and healthy, Cup-bearer of tears Cry, the once Beloved Idea, weep for the love that was, the honor, pride, and truth of a world, a place, a country any just soul would fly to in time of need. Now all we need is a shovel, a plot of bare earth, a tired muscle, a withered heart, to bury all that once we loved

Published on February 18, 2018 10:46

February 16, 2018

The Garden of Verse: Wisdom in Gurus, Mothers, Vermont, and Flecks of Cappuccino Foam

I found not only a lot of fine poems in the February edition of Verse-Virtual, but a lot of wisdom. Poems live in our thoughts not for what they say so much as how they say it. We may 'know' these truths, or realize we've been told them (or shown them) before, but now we feel them as well.

I found not only a lot of fine poems in the February edition of Verse-Virtual, but a lot of wisdom. Poems live in our thoughts not for what they say so much as how they say it. We may 'know' these truths, or realize we've been told them (or shown them) before, but now we feel them as well. In his poem "Mahayana in Vermont," Sydney Lea is telling us that 'nothing' happens in the course of a long hike taken "with three dogs through the rain." But we know what 'nothing' means after hearing about the grouse, and the deer flies, and the "late trillium," and the counted steps. We know that 'nothing' actually means 'everything,' and are not surprised, but in fact happily gratified when the poem sums this 'nothing' up as "a mystic sense of well-being/ in quietly chanted numbers."

In Alan Walowitz's poem "String Theory," a guru morphs into a Jewish mother when he responds to a bill of complaints with the advice "Things could be worse." It's a pleasing conjunction, offering an insight into both roles. Our guru may not know everything; and our mothers (Jewish or otherwise) are likely to know something valuable about their children. This recognition leads to a slightly shocking, but worthily eye-opening embrace of peace from an unconventional perspective (which I won't completely spoil by quoting it here). Aging brings complaints, but it beats the alternatives.

In Penelope Moffat's poem "My Cat is the Buddha," the pleasure lies in how the proposition is advanced.

Yea though I do call her Smoke

her name is God.

Though I murmur “silly child”

she is intellect made flesh.

Serious things can be said lightly, and the wonderfully ear-pleasing arcane vernacular of sacred texts is out there for us to play with, as this poem so pleasurably does.

The fleshly intellect of the cat called "Smoke" is realized in warm fur, a "nubbly tongue," and the virtue of breathing her "honest breath" into a bedside water glass. Animals too can be a sacred text. What pleasure to read about this one.

Playful and fun as well, Kate Sontag's poem “The Many Lives of Foam,” invents a new world of "karma," the February issue theme that got me noticing the wisdom of these poems. It turns out that foam gets around. It's "a fleck of cappuccino... a white mustache on my future lover’s upper lip," also the "lather on your father's face," and the bubbling creation of "soap & glycerin" that finds a kind of ultimate release in a "roving rainbow." And a lot of other stages in between. Sometimes in the karmic journey of rebirths, everything is relative. Sometimes the thing to do is just look at it from a different angle. Judy Kronenfield's moving and impressive series of poems "Saving the Dead" suggests to me that we 'save' them best by remembering them. I'm particularly moved by a poem about the acute memory loss in parents or other aged relatives (that many of us have already experienced in family members), a condition described in the acutely titled "The Withering of Their State."

"...the scales fall

from their eyes, and they fall asleep

in each other's chairs, and thine

is mine, and now is then, and mildly,

with the most gracious of oh?s,

they allow themselves to be

removed..."

The wisdom here consists of seeing things as they are, offering the compassion that we would wish shown to ourselves... and simply letting be. Tom Montag's fine contribution to the February issue of five concentrated reflections includes a couple of unblinking looks at the persistence of darkness in all lives. A kind of insight and wisdom that perhaps flows from "the stranger/ angel in my nature," to quote from his poem "The Sadness of Happiness." As this poem says, "between kiss and climax/

there is always this darkness." The somewhat longer lyric "Walking the Tracks on a Warm December Day" suggests a particulary Decemberish insight consistent with the time of year when the light is at its briefest, the dark its longest. The poem asks, "Train in the distance, or not?" But the poem knows the train is always out there, and will someday arrive. These are a few of the poems that spoke me in the February Verse-Virtual. Many other fine poems can found at

http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an...

Published on February 16, 2018 15:33

February 9, 2018

The Garden of Stories: Rikers Island Prison, Where White Boys Got 'Woke' to the Reality of Who Goes to Jail in America

My short story "Behind Bars," dating from a summer internship at Rikers Island, the famous and infamous New York City prison, is published on the internet short story journal, "Beneath the Rainbow (http://beneaththerainbow.com/behind-b...).

My short story "Behind Bars," dating from a summer internship at Rikers Island, the famous and infamous New York City prison, is published on the internet short story journal, "Beneath the Rainbow (http://beneaththerainbow.com/behind-b...).It's the summer I learned about who was 'behind bars' in America's large urban prisons. People of color. People from Latin America. People, some of them white, who grew up in certain densely populated inner city neighborhoods, with bad schools, too little family income, absent fathers, family histories including alcohol, domestic abuse, and possibly drugs. People who valued money because they didn't have enough of it. People who learned to get it in any ways I never thought of. Stealing, fencing, scamming, gambling, hustling, selling drugs. People who -- if and when -- they became drug users (heroin then; many choices these days) knew where to look for money: in their family members' hiding places, in the loose behavior of people (often white) who were less worried about keeping it, behind vulnerable locks on apartment windows and doors, unlocked or otherwise vulnerable vehicles, in the stores, workplaces, and warehouses where there was something lying around to steal.

Behind bars at Rikers, on a couple of occasions or twice, I tried to do something out of the routine to help people. One inmate was an admitted fence, but not a drug addict. His little brother, however, was a 'junkie' and was certain to break in and rob his apartment if he learned that he was in jail. To protect his home he needed to make a phone call; would I help him? I did.

On another occasion an inmate who ran an illegal high-stakes poker game, he admitted it, told me that he had been committed to prison without having appeared before the judge. No day in court? He told his guards about this omission, but no one would believe him. He knew he would end up jail for a few months after appearing before a judge, but it was the principle of the thing. He believed in the American 'justice system.'

I persuaded the prison authorities to look into it. The guy was right.

Here's how my story "Behind Bars" begins:

White summer interns in sports jackets and slacks, we’re assigned to assist the social services department in the Reception Center of the Rikers Island prison complex, run by the New York City Department of Correction. A set of the three big units (men, women, youth), the prison was built on an island in New York City like a harbor fortification, but Francis Scott Key never visited Rikers Island. It is one of the largest prison complexes in the world.

Undergraduates, newbies in the way of the world, we’re assigned to our little cement box of cell-like offices, each with his own desk, chair and yellow pad. Our work begins when a new shipment of convicts is dispatched to the island after their day — or, more likely, minute — in court. They arrive in big daily batches, like harvested crops or factory deliveries. Dominic, a neat, black-haired young man of Cuban descent a year my senior, and I sit in our office cells conducting formalized “reception interviews” for each new inmate, inking down their responses to a long series of intrusively personal questions on a four-page form.

Who are these men? Why are untrained summer interns, college kids, mere players in the fields of academe, entrusted to carry out these interrogations, however rote and bureaucratic? Who are we to ask such questions of men twice our age, sometimes older?

Here's a brief excerpt about my college kid naivety:

Though I myself was born in the Borough of Queens, [the inmates] speak of neighborhoods, or spawning grounds, by names I am unfamiliar with.

“They call it Hell’s Kitchen,” one fair-haired young man informs me.

“But you’re white,” I blurt, ignorantly.

He laughs. “They’re all Irish,” he tells me. “The kids I grew up with? They’re all in jail.”

To read the whole (not very long) story, see:

http://beneaththerainbow.com/behind-b...

Published on February 09, 2018 11:28

February 3, 2018

The Garden of Verse: When You Get What You Deserve, Now or Later, It's 'Karma'

Karma, the belief that our actions in this life, plus some steerage from whatever is hanging around from previous existence, determines our condition in our next life, is a word a lot of us use in informal ways. It's the theme of this month's Verse-Virtual.com, in homage to the recently deceased poet Dick Allen, who explored Buddhist ideas in some of his later work... And it's an idea that can go in a lot of directions. In the classical Hindu theory of reincarnation, the sum of your moral conduct will determine the state of your next incarnation. Will you be reborn as a higher-status individual, or a lower one? Or as an animal? Or possibly even an insect? So don't step on that ant; he may come back as your boss. In the American vernacular "karma" tends to be used loosely to suggest a cosmic connection of any sort between past events and present ones. Did the IRS send you an unexpectedly large refund just when you needed it, after you spent a lot of time last year volunteering at a nursing home? It's karma. On the other hand, if you've been nasty to someone at work, then someone is mean to you later that day, or the next day, or the next week. And a part of you feels, 'well, maybe I deserved that.' In response to Verse-Virtual's theme for the February issue, I contributed three poems on ways of thinking about karma.

Karma, the belief that our actions in this life, plus some steerage from whatever is hanging around from previous existence, determines our condition in our next life, is a word a lot of us use in informal ways. It's the theme of this month's Verse-Virtual.com, in homage to the recently deceased poet Dick Allen, who explored Buddhist ideas in some of his later work... And it's an idea that can go in a lot of directions. In the classical Hindu theory of reincarnation, the sum of your moral conduct will determine the state of your next incarnation. Will you be reborn as a higher-status individual, or a lower one? Or as an animal? Or possibly even an insect? So don't step on that ant; he may come back as your boss. In the American vernacular "karma" tends to be used loosely to suggest a cosmic connection of any sort between past events and present ones. Did the IRS send you an unexpectedly large refund just when you needed it, after you spent a lot of time last year volunteering at a nursing home? It's karma. On the other hand, if you've been nasty to someone at work, then someone is mean to you later that day, or the next day, or the next week. And a part of you feels, 'well, maybe I deserved that.' In response to Verse-Virtual's theme for the February issue, I contributed three poems on ways of thinking about karma.The poem "International Karma" connects the violence two communities inflicted upon one another in the past as warring allies of World War II enemies England and Japan to the assaults the Buddhist Burmese majority are currently inflicting on the ethnic minority Rohingya, who are Muslims. Here's the poem:

International Karma

The Rohingya may know little of karma

They follow a prophet whose law was furthered

by rounds of daily prayer

offered fresh from the oven of the soul

And though their persecutors are, formally, Buddhists

whose varied traditions of thought include the notion

that what you do here and now

affects who, or even what, you become then and there

and even in the undreamt future,

traditions of thought and belief

lose sway to the smarting remembrance of grievances

therefore doing onto others what the British and their allies

have done to you, and what you and the wartime Japanese,

have done to those whose mutilated communities

now flee, carrying their borders on their backs,

raising for those who look from afar the question:

Is karma but another word for history?

It may be, as the Vikings once believed,

that 'destiny is all'

But if karma bends to the wheel of fate,

it is the heft of human deed that pushes wheels along

and karma,

the fingerprint on the soul,

the DNA of conscience,

the golden template of deeds good and ill,

inscribes our souls in the book of eternal recurrence

... And so whatever dooms have befallen you,

courtesy of the British or the Japanese

it is hard of heart

to see how compunction requires the expulsion of a people

much like oneself

arms, legs, eyes that weeps, loins that

breed a miracle of life

from particular pieces of planet Earth,

where ways of life, or worship, or contemplation

are various in dress, but rooted all in home,

familiar food, happy smells, a well of communal expectations

entreating safe return for

love's meager, wounded, breakable body

To read my other poems, "Karma Falls From the Sky," and "Christmas Karma," go to http://www.verse-virtual.com/robert-k... Plenty of poems by many fine poets on a wide variety of subjects in the February 2018 issue can be found at: http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an...

Published on February 03, 2018 21:31

January 28, 2018

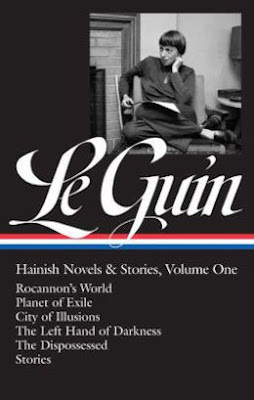

The Garden of Literature: Ursula Le Guin, Creator of Worlds Where People Can Find Themselves and, Possibly, Make Sense

Ursula Le Guin was not only America's best writer of imaginative literature, she deserved a seat on the Council of the Wise, the body I am currently imagining to replace the increasingly corrupt and anachronistic US Senate.

Ursula Le Guin was not only America's best writer of imaginative literature, she deserved a seat on the Council of the Wise, the body I am currently imagining to replace the increasingly corrupt and anachronistic US Senate. How many people do we have who invent universes of interconnected planets in order to explore basic problems of human existence such as loss, loneliness, the need for love, cloud control, societal conflict, war, interstellar communication, gender roles, youthful uncertainties, political dysfunction, and dragons -- to mention a few standout examples...?

My encounters with Le Guin began with the fittingly named short novel "The Beginning Place," in which an invented society with its attractions and dangers provides a perfect setting to explore the adolescent and early adulthood struggle for identity. The story takes place in a parallel-world forest that you enter simply by passing through some invisible gate in an 'our-world' forest. When I was younger I used to stumble into such places, which are of course places inside ourselves. In "The Beginning Place," Le Guin leads her characters (and readers) into a Medieval forest village setting. I love stories with faux-Medieval forest settings. We can all think of examples. The relentlessly popular film "The Princess Bride," for one, plays itself silly with one of these.

We can't spend all our lives in the presumably (though not really) safe worlds of our upbringings, even less so in mediated or 'virtual' versions of the world constructed for us by others. We have to get out of our other-conditioned selves to find our real 'selves' -- that is, the voice that tells us what we really think. We have to go where Stephen Sondheim does in that most philosophical of his musicals, "Into the Woods."

I think the books of the "Earthsea Trilogy" came next for me. Again, the hook that drew me is the story's unstated heart, the realization in the human soul of the young person's quest for self. We don't learn the deep personal truths by stories about people who are too much like ourselves, but those who strike us as really strange. That's probably why myths and legends and folk tales (sometimes called fairy tales) have lasted so long. Sophocles put the gods on stage. Wisdom teachers through the ages, Freud and C.S. Lewis, Tolkien, went back to the oldest stories we know.

The Earthsea Trilogy are the stories in which Le Guin gives us the wizard Ged -- who I think of as the 'interesting wizard' to distinguish him from that other too-popular 'wizard' who is more commercial vehicle than prince of literature. The book I remember best of these is the second (though maybe I read it first), "The Tombs of Atuan," in which a child is separated from her family and raised in some ritualized condition of darkness that -- for my own needs, perhaps, or imagination -- seemed to symbolize the darkness in which all human beings are 'thrown' into existence. "Thrown," a term I learned from the 20th century philosopher Heidegger, represents the impossible -- or wondrous -- condition of all human existence. We don't why we are here, where we came from, and what this business we find ourselves part of is all about. (Hence the eternal question: does it mean anything?)

In the "The Tombs of Atuan," when the heroine explores the obscure condition of her existence, actualized by Le Guin as a gloomy "Labyrinth," she has the good fortune to come across the wizard Ged. Most of us have to make do without anyone like him.

In these Earthsea stories as in her sci-fi novels set in deep space, we understand that these settings and situations are reflections of our own problematic times and places. All worthy scifi and fantasy settings are allegorical by nature. They are literary machines for barraging us with unstated questions: how do the dangers, hardships, pressures, bizarre customs, and mysteries of these imagined settings become dark mirrors for the circumstances -- social, anthropological, corporate, whatever -- in which people in our world are forced to contend with? Needless to add, the answers are unstated as well.

I'll mention a few of the books in the Hainish world, where some of her most widely read and enduring novels are set. "The Left-Hand of Darkness," the book most people mention first when they recall Le Guin's works, give us a human-enough race of people whose gender changes as a natural part of their biology. What would that do to sex roles? To personal identity? Le Guin stated long afterwards that she never solved the problem of creating a third-person pronoun that was free of gender -- and neither have we.

In "The Dispossessed," I was excited to find a novel based on the stunning premise of a "world," a small planet, based on the theories of a foundational anarchist. But it's not a book of theoretical arguments; Le Guin's stories always have a plot. In "The Dispossessed," the the anarchist society fights for survival while its earth-like neighboring planet overpopulates and the rich oppress the poor, and the novel's central figure, a genius scientist who's a committed product of the anarchist world, realizes he has made a discovery that may help both societies out of their crises.

Another story of the Hainish world, "The Winter King" was the first book to posit a peopled world forced to endure decade-long stretches of a single season, a life-threatening winter; its plot imagines the consequences for the various peoples who share the planet. We who live on our own little planet are living with the comparable threat of climate change, though we may be facing the opposite condition: a hot, rainy season that never ends. It turns out that Ursula Le Guin's prophetic storytelling is based on another human universal -- a love of our world. The natural one. "My poetry and my fiction are full of trees," she wrote only last year in her introduction to a re-publication volume of some of her books, under the title Ursula K. Le Guin: The Hainish Novels & Stories, Volume One. "My mental landscape includes a great deal of forest. I am haunted by the great, silent, patient presences we live among, plant, chop down, build with, burn, take for granted in every way until they are gone and do not return. Ancient China had our four elements, earth, air, fire, water, plus a fifth, wood. That makes sense to me. But China’s great forests are long gone to smoke. When we pass a log truck on the roads of Oregon, I can’t help but see what they carry as corpses, bodies that were living and are dead. I think of how we owe the air we breathe to the trees, the ferns, the grasses—the quiet people who eat sunlight."

[https://www.tor.com/2017/08/30/introd... ]

We eat sunlight too, only after it's been through the bodies of plants and, in many cases, animals.

Reading this great author's observations on her own canon makes me want to go get lost in the woods again. I wonder who I'll find there.

Published on January 28, 2018 10:33

January 23, 2018

Garden of the Seasons: Changing Faces of January

January is pretty much a black and white month. A very light, but pretty snowfall two weeks back turned our Quincy neighborhood into a 19th century village. Very quiet; nothing moving. Softly falling snow in big visible flakes, many of them dusting the exposed surfaces of the bare trees, a graceful effect magnified by the presence of evergreen trees and shrubs. We may not be able to count on a White Christmas very often these days, though all the old pictures and nostalgic movies always give people a white Christmas. But we generally have a lot of white days, and often weeks, in January.

January is pretty much a black and white month. A very light, but pretty snowfall two weeks back turned our Quincy neighborhood into a 19th century village. Very quiet; nothing moving. Softly falling snow in big visible flakes, many of them dusting the exposed surfaces of the bare trees, a graceful effect magnified by the presence of evergreen trees and shrubs. We may not be able to count on a White Christmas very often these days, though all the old pictures and nostalgic movies always give people a white Christmas. But we generally have a lot of white days, and often weeks, in January.

This year so far January has treated us to one full-day rocking blizzard, piling up snow walls on the gutters and hard-shoveling to liberate cars and driveways, in the midst of a wicked cold spell that locked in the accumulation. A week-long gradual meltdown finally reaching bare ground. Then the gentle picturesque minor snowfall pictured in the top three photos here.

This year so far January has treated us to one full-day rocking blizzard, piling up snow walls on the gutters and hard-shoveling to liberate cars and driveways, in the midst of a wicked cold spell that locked in the accumulation. A week-long gradual meltdown finally reaching bare ground. Then the gentle picturesque minor snowfall pictured in the top three photos here.The fifth photo down shows the first dose of blue sky we experienced after that fall. It wasn't warm enough, and the sun hasn't shined long enough to melt the snow off this path in the thin wood near the Quincy shoreline. But the return of the snow changed the face of the landscape and coaxed me out of the car for the first time in days.

Nights are still long in January, though we've picked up a half hour of daylight since the start of the month. That makes sunsets, lingering twilights, and the evening hush an even more attention-getting time of day than at other times. Inside a warm room we watch the sky turn color, then linger to monitor the fading tones as the darkness deepens. Posed against that twilight (fourth photo down), the red bloom of hibiscus, one of our summer annuals, gets to spend the winter indoor with us. Unfortunately we did not have space for the rest of the garden.

Nights are still long in January, though we've picked up a half hour of daylight since the start of the month. That makes sunsets, lingering twilights, and the evening hush an even more attention-getting time of day than at other times. Inside a warm room we watch the sky turn color, then linger to monitor the fading tones as the darkness deepens. Posed against that twilight (fourth photo down), the red bloom of hibiscus, one of our summer annuals, gets to spend the winter indoor with us. Unfortunately we did not have space for the rest of the garden.  The remains of the snowfall, and its effects, are still evident in the photos that follow. These were taken last weekend in the Blue Hills Reservation, the largest land preserve in the Boston area. It's accessible from Quincy, Milton and a couple other neighboring towns. While most of the footpaths were free of snow cover, some stretches in lower, shadier spots had crunchy, half-frozen tracts.

The remains of the snowfall, and its effects, are still evident in the photos that follow. These were taken last weekend in the Blue Hills Reservation, the largest land preserve in the Boston area. It's accessible from Quincy, Milton and a couple other neighboring towns. While most of the footpaths were free of snow cover, some stretches in lower, shadier spots had crunchy, half-frozen tracts. But the big news, in the woodland, was the presence of fast-flowing streams, overflowing at points into wetlands. We saw a couple of green shoots emerging from one of the boggier lowlands -- skunk cabbage, we wondered, already? The sounds of flowing, tumbling brooks provided the music of the winter thaw. It sounded much like the soundtrack to March and April in the New England forests. And we were reminded that "meteorological winter" is more than half over; that begins on Dec. 1 and ends with February.

The final three photos show the face of the thaw. Snow melting into stream and wetland, water feeding the groundwater reserve. The ground nourishing the forest, and all the other life that depends upon it.

We heard a few birds, saw almost none. Nothing else was moving that wasn't human, or canine. But the waters were moving. And the season. And the ancient revolutions of the earth behind it all.

Published on January 23, 2018 20:48

January 19, 2018

The Garden of Literature: Searching For Truth on "The Underground Railroad"

After reading "The Underground Railroad" by Colson Whitehead, awarded the National Book Award for Fiction in 2016, and being at least mildly surprised by the liberties the book takes with the historical record, I decided to see what facts I could learn about escaping slavery. Here's some of what I found out. The reality of the "underground railroad," as opposed to its legend, is that it was relatively unimportant in pre-Emancipation America. Contemporary historians looking at the records estimate that the number of white people who helped fugitive slaves free themselves from bondage throughout the lengthy period when slavery was legal numbered only in the hundreds. Despite the dramatizations of film and TV, no underground railroad 'stations' existed in the slave states; the so-called 'railroad' existed only in the North. And once an African American fleeing slavery managed to cross a state line into Ohio, or Illinois, or Indiana or Pennsylvania, any northerner willing to hide, enable, offer money, clothes, food, or a tip on where to go next was likely helping a runaway get to Canada. For in most places and at most times throughout the history of slavery in the United States, the North was not safe. Slave catchers routinely followed the trail of runaways over the border. And after the Fugitive Slave Act became law in 1850, slave catchers (or any white person) had the right to claim any black person (even free ones) as his lost property and go before a kangaroo court that was legally encouraged to find for the white claimant in all cases. Most whites turned their back on slavery, or shrugged their shoulders, or were of the opinion that black people belonged in slavery rather than living among white people. Outrage over the Fugitive Slave Act fueled abolitionist feeling in states such as Massachusetts, but abolitionists were never close to a majority anywhere in the North. So there is plenty of guilt for white Americans whose roots lie in the North to share with fellow Americans with southern roots when it comes to assessing our nation's slave-holding past. The popularity of the underground railroad, a concept more myth than practical reality, stems from Americans' need for a story of brave and moral conduct in defiance of "the peculiar institution" to point to as a moral beacon -- somewhat analogous to the way the Statue of Liberty serves as a national salute to our image as a welcoming home for immigrants and refugees, even though the true story is a lot more complicated and a lot less benign. There was nothing, of course, at all benign about the institution of African slavery in America. The emphasis current day culture places on the underground railroad is an attempt to lift the moral scale at least a notch off rock-bottom moral evil. But might it not be better simply to face the facts. Slavery persisted for so long in this country because of its economic benefit. It led to accumulations of wealth by a white-dominated society that would not have been possible without the abundant resource of unpaid slave labor. Slavery was a good deal for the white majority. The advantage goes way beyond the oft-noted fortunes made by northern ship owners from the slave trade. The young nation as a whole benefited from a robust agricultural economy: from the rapid development of untilled land, cleared of its native occupants by national policy, and then cleared for agricultural uses and productively farmed by enslaved African labor to raise cotton and other market crops. America's dominant export in the 19th century, the cotton trade was taxed and the funds raised turned to infrastructure development. Cotton exports played a major role in our trade balance with Europe. Texas and the American Southwest were taken by force of arms from Mexico by national policy under the impetus to seek new lands to 'open' for cotton production. So given that white Americans were in no hurry to abolish slavery -- as illustrated by the infamous compromises in our Constitution that recognized the 'peculiar institution' and established a slave's value as three-fifths of a person when it came to determining a state's representation in the House of Representatives -- how did slaves seek to escape their bondage? In a lengthy, statistically based article appearing in the New Yorker two years ago, Kathryn Schultz writes that "while fugitives did often need to conceal themselves en route to freedom, most of their hiding places were mundane and catch-as-catch-can—haylofts and spare bedrooms and swamps and caves, not bespoke hidey-holes built by underground engineers." The efforts of heroic "guides" such as Harriet Tubman were real enough, that is, but most runaways were faced with making it on their own without any systematic assistance. Not only did the underground railroad fail to penetrate into the slave states -- the Carolinas, the infamous black belt states of George, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana where cotton production caused slaves populations to rise sharply in the 19th century -- "most people who slipped the bonds of slavery did not look north," Schultz writes. In fact, despite its popularity today, she writes, "the Underground Railroad was perhaps the least popular way for slaves to seek their freedom. Instead, those who fled generally headed toward Spanish Florida, Mexico, the Caribbean, Native American communities in the Southeast, [and] free-black neighborhoods in the upper South" known as Maroon communities. It doesn't play well for white American audiences to watch fugitive slaves from the Carolinas struggling to reach Florida or Mexico rather than following "the drinking gourd" north with the assistance of brave black guides and white abolitionists. One of the reasons the United States forced a weakened Spain to cede Florida to us was the complaints of slaveholders that the sanctuary of the Spanish colony was attracting their valuable property. After Florida became a state, fugitive slaves living there as freedmen had to find somewhere else to go. And just to put the story of the 'escape' from slavery in a less dramatic, but still more realistic context, Schultz offers this assessment: "Moreover, most slaves who sought to be free didn’t run at all. Instead, they chose to pursue liberty through other means. Some saved up money and purchased their freedom. Others managed to earn a legal judgment in their favor—for instance, by having or claiming to have a white mother (beginning in Colonial times, slave status, like Judaism, passed down through the maternal line), or by claiming to have been manumitted." In many cases aristocratic slave owners followed the custom of freeing their slaves upon their own death in their will, in part as a reward for loyal service. This appears to have been a tradition in Virginia that father-of-our-country George Washington was unable to follow because most of his slaves actually belonged to his wife. Thomas Jefferson didn't free his slaves because his estate was in debt. Somehow, an analysis of available figures suggests, about ten percent of slaves found their way to freedom, only a very small percentage of these via the underground railroad. Colson Whitehead's invention of actual underground tunnels fitted with rails and small trains to assist runaway slaves in states such as Georgia and the Carolinas, while it appeared to please the critics who praised it as a bold device, to my mind serves no real purpose in his novel. It's hardly needed to tell the dramatic story of the challenges and dangers fugitive slaves faced, and even in the fictional context of the novel is shown to do very little good since it fails to help any of his characters reach freedom. The book's central character, the runaway Cora, is abandoned in one disconnected station after another. While the fiction of a 'real' railroad has charmed a lot of readers and critics, it strikes me as arbitrary, intrusive, inessential to the plot, and serves only to make this reader wonder what we do know about escaping slavery. Whitehead takes the same liberty in including other fictional and anachronistic elements into his story, including forms of racist discrimination and exploitation that took place beyond the era of slavery -- the Tuskegee experiment (involving untreated cases of syphilis in black men); research into schizophrenia; forced sterilization -- and belong to America's later, and often shameful post-Emancipation history. These inventions include the imagining of a paternalistic apartheid state in South Carolina, where such experiments take place, and a genocidal North Carolina where the worst, most murderous and sadistic examples of race hatred become a kind of statewide sport celebrated with regular execution festivals. The obtrusive presence of these fictional devices caused me to question my knowledge of American history. Did North Carolina actually practice genocide? Not really. Slave catchers of the sort the author places there operated everywhere. And executions of runaways took place throughout the Deep South, as they likewise did, for instance, in Haiti. I'm not sure what we can learn about the 'truth' of slavery in so fantasized a depiction. Many fiction writers do play with history, of course. Books are written on the premise of 'what if Germany had won the war.' Or what if the South had won the Civil War. Scifi-fantasy writer Orson Scott Card wrote a series of books on an alternative American history; in which, for example, William Blake turns up on the frontier in a pre-Civil War America. These books tend to be classified as genre works. National Book Awards, on the other hand, tend to go to books considered 'literature.' If Whitehead's book does have meaning for us that goes beyond the 'what if' sort, it has nothing to do with the underground railroad, and everything to do with the pure hatred shown by almost anybody white in this book (aside from a few railroad operators) to anybody black.

I'm not sure a writer has to make anything up to tell this tale about American history, this persistently dark strain in the American character, the country's second "original sin" (after the theft of the land from the Indians). Certainly writer James Baldwin made this point a half century earlier, as last year's eloquent documentary "I Am Not Your Negro" reminded us. His fear for his country's future, Baldwin told us, is that white Americans' hatred for black people has seriously warped their own character. It's a self-inflicted moral wound that -- even after MLK, civil rights, Obama, and everything else that has taken place in the 150 years since slavery -- white Americans have been unable to overcome. The strongest elements in "The Underground Railroad" -- how the constant presence of physical fear in the of life of slaves warps their relationships with one another and hamstrings their own plantation communities; and, to take another example, what it's like to spend months hiding in an attic room watching the world through a tiny hole in a wall -- come from the author's imaginative delving into the psychological and emotional realities of slavery. These qualities can be more widely applied in writing about slavery in America. The critical success of Colson Whitehead's book comes from an appetite for that kind of imaginative exploration of a true American story that still haunts us -- as it should. Exploring that terrible truth is the job of literature. I would have liked to see more such truth in this book.

Published on January 19, 2018 13:23

January 13, 2018

The Garden of Verse: Words That Roll Through These Marvelous Poems About Bicycles, Hard Times, and 'Guys Like Us'

Some poems make music; some words just work together. These virtues are on display in many of the fine poems appearing in the January 2018 issues of Verse-Virtual, the online poetry journal. As, for example, in these lines by William Greenway in his poem "as she watches through the window":

Some poems make music; some words just work together. These virtues are on display in many of the fine poems appearing in the January 2018 issues of Verse-Virtual, the online poetry journal. As, for example, in these lines by William Greenway in his poem "as she watches through the window":...There are kids, I guess,

who live in a money-feathered nest

of Magic Kingdoms, Disney days

and firework princess nights,

the jingle-belled hooves and snowy thump

of Santa’s’ boots on the roof, every day

three-rings of enchantment until, inevitably,

the circus leaves town.

"Jingle-belled hooves," a musical combination in itself, grooves our ears for the flowing long vowels of 'boots' and 'roof .' And the phrase "boots on the roof" ring in the ear just a like a "snowy thump." The language in Greenway's poem "At the Writers Conference" -- a lament that captures the essence of any 'big name' conference (writing or otherwise) I've ever attended -- effectively conveys the poem's sense of the event:

Finally, all this hoopla and high-mindedness

came down to a lobster roll and some tandoori chicken

for this hick from the sticks and the tapped-out steel mills.

'Hoopla' and 'tandoori chicken' strike me as the kind of words just aching to get into a poem on an oversold event. And the third of these three lines rolls at a pace and rhythm that a 'stick' might make 'tapping' its way home to the mills -- a folksy, fitting sound.

In Linda Fischer's "Digression," the magic lies in images that are just right to convey a wintry grinding down sensation. After whacking the snow off her conifers, the poet asks:

...What

would it take for the geese to change

their course mid-flight, the wind

swallow their cries and plow

them back to a creek swollen

with early snow? Or the sap

to gather itself for one last

shudder before the darkening day

surrenders to one long night?

The implicit answer, it appears, is 'nothing we could ever do.' The geese will not change their course, and the sap no longer flows.

In Christine Gelineau's "Nothing To It," the language of the lines below sounds to me just right for the sensation they're talking about: the temptation (and appeal) of the unforgiving gesture, the burned bridge.

Demolition is the instant payoff

—volatile, thrilling, an aphrodisiac

of power.

In contrast, building something up has a stop-and-go pace. as the words in the next lines suggest:

Creation drags along

in slo-mo, a chick flick

of unfolding and relationships

And the language of the lines that follow illustrate their meaning by their own aural attractiveness:

how we’re drawn to the swing, the bang,

the rubble, rubbernecking by the wreck

This final observation serving as the perfect summary of the lure of 'rubbernecking':

as if we thought

obliteration was some kind

of an accomplishment.

Sydney Lea's "1959" is an affecting poem about the power of certain moments to stay with us forever not because anything particularly wonderful has happened, but because their meaning cannot be captured by any clear message or storyline: they don't lead to happy endings, or new beginnings, or obvious crises, or moments of decision in which we take the right course, or the wrong one. They are simply (but also complexly) so real:

If I could just stay right there like that on that bench.

Those slight waves lisping. That gravel strand.

St. Jean de Luz. That breeze and mollusky stench.

That sun melting on the far Low Pyrenees.

If the people around me could just keep keeping quiet

like that, not because the music was good

but because it was long and awful

Sometimes -- this poem says to me -- people, or nature, or the world, or our own minds do manage, in this poem's superbly apt phrase, to "keep keeping quiet."

Another apt expression, "guys like us," appears in the poem of that name by Alan Walowitz. After a student is killed by a policeman in a minority neighborhood where the speaker teaches school, a previously friendly student begins to draw away:

I swear I saw him eyeing me each afternoon

as the cops escorted us to our cars which would take us home,

to a neighborhood safe for guys like us.

It's the 'the cops' escorting the teachers to their cars to go home to a 'safe' neighborhood that got to me. Though I was never faced with running that sort of gauntlet, I know I'm one of those 'guys like us.'

In a poem about the pleasures of cycling, "A Bicycle Poem" by Robert Wexelblatt, lines like these below convey the speed and pleasure and sensation of freedom involved in the ride.

Earbuds pumping out Brahms’ Second Serenade

or Soler’s Fandango as you outstrip mosquitos

on a Sunday morning—a moving Mass, solitary

Sabbath—biking past the SUVs arrayed outside

St. Aiden’s, communing with I-Pod, sky, and road,

the Camelbak preserving cold, sacramental water,

knees, hips, and muscles all in proper working order:

on the seventh day you pedaled and it was good.

All these elements, the pumping music (suggesting, of course, the petal-pumping muscles), leaving the heavy vehicles behind, the 'cold, sacramental water' of the biker-geeky Camelbak bottle, the glancing spiritual references, go together to sell the truth of the last line. We may at some moments in our life, this poem tells us, to be the god of our experience. And when that happens, as the poem persuades us, it surely is good. What a ride poems like these offer us. See these and more at http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an...

Published on January 13, 2018 16:48