Robert Knox's Blog, page 19

August 2, 2018

Garden of Verse: Trees for Me, Wearing Well for All Seasons

I'm still celebrating trees this month. I don't know how long this fixation will last, but the way I'm feeling these days I may ride it a some considerable time. As the dominant species on the planet Earth -- so dominant that even though we're still newcomers we now have a whole geological period named after us: the Anthropocene -- human beings have to figure out a way to live on earth without living off it to the destructive extent that we are currently indulging in.

I'm still celebrating trees this month. I don't know how long this fixation will last, but the way I'm feeling these days I may ride it a some considerable time. As the dominant species on the planet Earth -- so dominant that even though we're still newcomers we now have a whole geological period named after us: the Anthropocene -- human beings have to figure out a way to live on earth without living off it to the destructive extent that we are currently indulging in. We have already destroyed most of the world's old forests. Yet all terrestrial life, animals and other plants, depend on climate regulatory and other functions provided by trees.

This said, two of my poems in the August 2018 issue of Verse-Virtual.com are celebratory -- at least that's the intent. Gloom and doom in abeyance. The third is something else altogether

The poem "This Tree" begins with a quote from an ancient source:

"For you have five trees in paradisewhich do not change,either in summer or in winterand their lives do not fallHe who knows themshall not taste of death."-- the Gnostic gospel of Thomas

My poem continues:

This tree

From Adam's garden grew

And fed a world of green plant

eaters, tiny shrews that one day grew

into a race of limber primates,

a hungry crew

that ate green earth down to the bones

Five trees grew in Adam's garden

that do not change their clothes for winter

And their tribe lives on forever...

I would have them in my garden

Would they keep me in their world?

.... Please read the rest of this poem, and find many others, at Verse-Virtual.com http://www.verse-virtual.com/robert-knox-2018-august.html

The second poem in the August issue, titled "Influence of Earth," also begins with a quote, this one from Thoreau. Then, nothing shy, I jump right in:

Influence of Earth

"Live in each season as it passes; breathe the air, drink the drink,

taste the fruit, and resign yourself to the influence of the earth." --Thoreau

Build yourself a cathedral in the trees

Hear bluebells ring in "Campanula"

Hear the birds play in the mulberries

(knowing that it's work for them)

Drink down the shade from roofs of leaf-warp

weaving ceilings for the sky...

The third poem, "Hair: The Reunion," is a salute to the 'salon' that trims my personal growth.

You can find all the poems here:

http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-and-articles.html

See this poem, and many others, at Verse-Virtual.com http://www.verse-virtual.com/robert-k...

Published on August 02, 2018 12:52

July 31, 2018

Garden of the Seasons: Final Bows From a Star-Studded July

Friends, have I told you that I love July? I did? Oh, yeah, pretty much every day this month.

A lot of perennials appeared to be having a good time this month as well.

And, happily for me, they continued to find their own water. Today was the first time this month I thought about hauling out the old lawn sprinkler to make some of the drier patches of ground (I generally can't see too many because the plants block my view) look happier. This practice probably does the plants some good, especially if their leaves are visibly wilting. More often it just makes me feel better.

And, happily for me, they continued to find their own water. Today was the first time this month I thought about hauling out the old lawn sprinkler to make some of the drier patches of ground (I generally can't see too many because the plants block my view) look happier. This practice probably does the plants some good, especially if their leaves are visibly wilting. More often it just makes me feel better.  Happily a year of decent rains put enough water into the ground, relieving me (and the plants) from the anxieties of the typical midsummer drought. You know, think brown lawns. That doesn't mean that it won't happen in August.

Happily a year of decent rains put enough water into the ground, relieving me (and the plants) from the anxieties of the typical midsummer drought. You know, think brown lawns. That doesn't mean that it won't happen in August.

July is the big month for daylilies. After the familiar orange native variety finishes their bloom, cultivars such as the daylilies in the top photo take over the stage. To my shame I gave up trying to keep track of their names years ago. This plant produces blossoms that are big, striking, and numerous. If I had to name it, I might call it 'best seller.'

July is the big month for daylilies. After the familiar orange native variety finishes their bloom, cultivars such as the daylilies in the top photo take over the stage. To my shame I gave up trying to keep track of their names years ago. This plant produces blossoms that are big, striking, and numerous. If I had to name it, I might call it 'best seller.' The second photo down is a medium tall, white flowering herb called Achillea or, more commonly, yarrow. Herbs tend to be native plants that are hardy and make the best of the situation.

The third photo down is Balloon Flower, whose formal moniker (I'm told) is Platycodon grandiflorus. It's grand, all right in July. The 'balloon' name comes from the puffy buds, some of which you can see in this photo. It's their color and prolific quantity of blossoms that make them a winner for me. These happy flowers are shown in a tighter close-up in the page's second-to-last photo.

The third photo down is Balloon Flower, whose formal moniker (I'm told) is Platycodon grandiflorus. It's grand, all right in July. The 'balloon' name comes from the puffy buds, some of which you can see in this photo. It's their color and prolific quantity of blossoms that make them a winner for me. These happy flowers are shown in a tighter close-up in the page's second-to-last photo. The next photo down shows some of Black-Eyed Susans (Rudbeckia hirta) that proliferate this time of year. I've learned they are a member of the sunflower. We have tow varieties, one (pictured here) blooms a few weeks earlier than the second, which has somewhat darker green leaves and stems and has proved a real land-grabber, well adapted to our part-shade growing condition.

The sixth photo shows a group of these familiars hanging together. At its center are the Echinacea, sold as Cone Flower, another hardy herb. The violet variety pictured here is Echinacea purpurea. The purple and the white blossoming Echinacea are shown together in the fifth photo down.This grouping of flowering perennials (sixth photo) hangs together for about a month. The balloon flowers, pictured earlier, have begun drop out of the scene, all their splendid little buds having popped and faded in the familiar parade of the seasons.

The sixth photo shows a group of these familiars hanging together. At its center are the Echinacea, sold as Cone Flower, another hardy herb. The violet variety pictured here is Echinacea purpurea. The purple and the white blossoming Echinacea are shown together in the fifth photo down.This grouping of flowering perennials (sixth photo) hangs together for about a month. The balloon flowers, pictured earlier, have begun drop out of the scene, all their splendid little buds having popped and faded in the familiar parade of the seasons.  The seventh photo down centers on Liatris, a thistle-like flower growing on tall spikes. Also called Blazing Star, and (a name from an earlier day) Gay flower. Our spikes are not very tall, maybe because the situation gets a lot of shade. It's a another bee-attracter. We get a lot of bees.

The seventh photo down centers on Liatris, a thistle-like flower growing on tall spikes. Also called Blazing Star, and (a name from an earlier day) Gay flower. Our spikes are not very tall, maybe because the situation gets a lot of shade. It's a another bee-attracter. We get a lot of bees.  The back piece of garden gets good light on July afternoons. The eighth photo down pictures a high-noon gathering of the some of the perennials named above.

The back piece of garden gets good light on July afternoons. The eighth photo down pictures a high-noon gathering of the some of the perennials named above. The next photo depicts the angle of the so-called "Gooseneck Loosestrife." Another herbaceous perennial, this one from the Lysimachia family, this gang has expanded its territory in recent years.

Another shot taken in the high sun hours, the photo to the left centers on the pink-flowering tall phlox (Phlox paniculata), that bloom in July and stay with us all through August. These too eat up a lot of territory and hold on to a lot of color.

Another shot taken in the high sun hours, the photo to the left centers on the pink-flowering tall phlox (Phlox paniculata), that bloom in July and stay with us all through August. These too eat up a lot of territory and hold on to a lot of color.

Published on July 31, 2018 21:29

July 22, 2018

The Garden of Verse: Saluting Home-Grown Truths About Where We All Came From and Other Poems of Our Season

In the patriotic month of July, the idea of 'America' sent Verse-Virtual poets on a thematic dig through symbols, memories, generational retrospectives and hard looks at what I recently heard described as "our cultural moment." Gee, whatever could that mean? Maybe Uncle Sam can help. Jim Lewis's bracingly original take on a familiar icon in his poem "shaving america" makes this vivid appeal: "we need you, uncle sam/ need your rebellious hair/ waving white in the breeze/ need that familiar goatee/ flying like a white badge/ of courage..."

In the patriotic month of July, the idea of 'America' sent Verse-Virtual poets on a thematic dig through symbols, memories, generational retrospectives and hard looks at what I recently heard described as "our cultural moment." Gee, whatever could that mean? Maybe Uncle Sam can help. Jim Lewis's bracingly original take on a familiar icon in his poem "shaving america" makes this vivid appeal: "we need you, uncle sam/ need your rebellious hair/ waving white in the breeze/ need that familiar goatee/ flying like a white badge/ of courage..." Lewis's other poem in the July issue, "how long does it take," is a vivid verse essay on what could possibly be meant by the notion of a 'real' American... "not a fake, not an invader/ not an illegal, or undocumented/ but a real, good-as-a-gold-dollar american." Because, clearly, everyone's origins can be challenged on the grounds that we came from somewhere else. Even 'Indians,' the poem notes, are "a figment/ of some explorer's imagination." The implication from these few richly packed stanzas is that being 'real' is not a matter of where you or your ancestors were born.

Firestone Feinberg's marvelous poem "After School" asks us to confront one of those 'anthem' words that Americans, and the world (at least in other 'cultural moments'), associate with this country. I won't spoil the ending by mentioning it here. A lot gets rolled into this poem's relatively few words and short lines, besides those cigarettes the poet recalls smoking at age fourteen. Consider these lines, curt as a teenage brush-off: "And your mother/ Is dead and you/ Are left with/ A father you/ Can't talk to". The smoking takes place not only after school but "By the/ Waters of Babylon/ And you remember/ The songs of/ Zion." A further deepening context in a very affecting poem. In "Honoring Ancestors," Joan Mazza writes of ancestors in Canicatti: "No one learned to read,/ but they knew of schools, saved lira for a steamship to America." Guess what happens "three generations later" to great-grandchildren who graduate from college, teach, speak two languages? They also "go back to the earth," grow basil, buy "semolina flour/ heart of the wheat from Italy,/ to make pannetone and pasta..." Do stories like this one -- regardless of whether these brave ancestors came from Italy or anywhere else in the world -- not make the USA a 'great' country and much richer than it would otherwise be? Why is this history not taught in schools?

Too much winning? When it comes to immigrant ancestors you have to take the eccentric with the ordinary, as Michael Minassian's poem "Naked Toes, Naked Stars" suggests. After his Armenian grandfather lost a big toe to a lawnmower, the poet visited him in the hospital and found him "rattling off a litany of complaints/ in a swift combination/ of four languages,/ confusing the hell out of the/ Puerto Rican nurse & Indian doctor ..." They wrap his foot "like some 20th/ century mummy from the Bronx" but fail to cushion his "cursing abilities" among other colorful traits. The poet's search for the missing digit brings the poem wonderfully back to those "naked stars."

Tricia Knoll's poem "The Value of a Home" addresses the issue named by its title in terms both close to home and close to the heart. How do you put a value, the poem asks, to immaterial assets such as the "Christmas tree corner with green/ lights, a deck where poetry flowed/ into the woods, enough water/ in the creek it might be crying"--? This is a moving poem about the kind of migration we all make at one time or another from one someplace to live to another, and about the unquantifiable human value of 'home' to all of us fortunate to have one.

Penny Harter's poem "Healing the Wound With Honey" flows from one of those scientific findings that reads like a kind of curiously wonderful found artifact. Research, apparently, has shown that "difficult-to-heal wounds respond well to honey dressings." I'd say this sounds like the stuff only poets can make up. Harter's poem begins with this perfect jumping off point: "It must have been inflicted in another life,/ this wound we can’t remember, not even sure/ whose it may have been." The poet illustrates those difficult wounds by way of a beautiful image "a wound/ of the spirit that even the heavy blue dressing/ of the sky can’t fix." So we must "learn the names of honey," and where we must offer this healing provides a deeply fitting ending I don't wish to spoil here.

However strongly we may feel about America, our home is also the earth. Robbi Nestor's "Benediction to the Earth" is a prayer that both cites and summons the enduring blessings of the planet. An Ekphrastic poem accompanying an image by Ira Joel Haber on her V-V page, ("blue as a morpho" butterfly to quote from the poem), "Benediction" asks the rain clouds to "carry our heavy regrets" and drop them harmlessly on desert; and among other requests petitions the sun to bring us "the chambered face of the sunflower." I like sunflowers. I don't ask where they came from (earth is answer enough). I bless the rain that falls in New England, without wondering what other country or continent it may have visited. And I am glad that my country births so many wonderful poems. You can find these poems and many others at http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-and-articles.html

Published on July 22, 2018 21:06

July 18, 2018

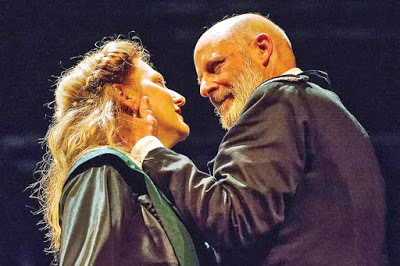

Shakespeare's Garden: 'Macbeth' in Our Season

Some aspects of Shakespeare's great political tragedy "Macbeth," director Melia Bensussen writes in her notes to the current production at Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, Mass., "resonated... with our cultural moment." Indeed. Would that 'moment' be the one when our current Usurper sells out his country's interests, alliances, values, and national pride to the two-bit totalitarian gangster who currently runs the long-running catastrophe generally known as Russia? "I thought about what moves and frightens us as contemporary audiences," Bensussen writes, and cites "how Macbeth's ambition, and belief in his imagination, lead to his destruction." She quotes the estimable literary critic Harold Bloom: "(The Macbeths) delight in their wickedness... Shakespeare rather dreadfully sees to it that we are Macbeth; our identity with him is involuntary but inescapable." Since 2016 there has been only one dominating influence on our 'cultural moment.' I won't say the name of the devil, but you know who I mean. What else can be meant by the 'cultural moment'? Me-too? The sins exposed there don't appear to have a precursor in this play since the only woman who matters, Lady Macbeth, is more actor than victim. You can see the "delight" Bloom speaks of in Bensussen's direction when Lady M. laughs in the course of her encouragement of her husband to murder and usurp. To throw caution to the winds and have the 'courage' to risk all for the prize of royal power, and be ruthless in obtaining it. They're playing the game of houses (or "Game of Thrones" as the TV series called it). Among other contenders for the Scottish crown we must count the head (Duncan's) currently wearing the crown, whose necked is saved by Macbeth's defeat of the rebels. Banquo, Macbeth's comrade in arms, is another rival. When we first meet Macbeth, he is triumphant in a just cause and likable. A furiously competent warrior, he takes pains to share the credit for the victory with Banquo. But Banquo must be eliminated because of the witches' prophecy. Though he will not become king himself, they prophesy, his descendants will. Our hero-villain naturally prefers his heirs to sit on the throne (even though he doesn't appear to have any). Other threats to his power include Duncan's son Malcolm. Suspecting correctly that he's a likely target of the conspiracy that murdered his father, he flees the castle before the Macbeths can take a run at him. Then there's Macduff. Though he evinces no appetite for the game of thrones power, simply because he is a name, a power center that might some day ally with Macbeth's enemies gathering across the border in England, the logic of tyranny says he must be eliminated. Ask any tyrant in our own season. Ask North Korea's Kim. Ask Putin why the oligarchs must be cut down to size before they become too popular or influential. Ask the Chinese Communist Party why no religious groups may operate in their country, no dissenters question their policies. Unlike history's more famous tyrants, Shakespeare's Macbeth has something they don't -- a conscience. An unavoidable capacity to experience, to feel, the reality of what he's doing. After he has Banquo murdered, Banquo's ghost ("in his blood") turns up at the dinner table. Macbeth's pathetic breakdown at the appearance of this ghost is black humor. Bensussen's production plays it for all that it's worth -- and then some; running the entire scene through twice. First with Banquo's ghostly appearance viewed by the audience. A second time with no 'ghost' on stage; the way, that is, the other guests would have perceived the occasion of Macbeth's mad-guilty ravings. The word the play's scholars use for this inconvenient capacity in a ruthless usurper is "imagination." Bensussen writes, "Macbeth too strongly believes in his own imagination..." He can, clearly, imagine himself king. But he can't help seeing the cost. To go back to that quote from Bloom: "Macbeth suffers intensely from knowing that he does evil, and that he must go on doing ever worse." Those last few words nail it. It's not enough to kill Macduff; you must kill his wife and children as well. No potential enemy can be left alive. Just as, to take a current instance, it is not enough to deny refuge to frightened people fleeing a threat to their lives. You must separate them from their children when you throw them in jail. That will show them. They won't try coming here again. But Macbeth, as I see it, chooses the path he does because he convinces himself that 'destiny' accords with his own desire for the crown. And, of course, the three witches help with that convincing. "Hail to thee, thane of Cawdor!" they greet him, before Macbeth has learned that Duncan has bestowed this title on him -- and "All hail, Macbeth, that shalt be king hereafter!" But the witches are (as they do again in a later scene), "equivocating" -- to use a term of moment. Shakespeare's moment that is. In the aftermath of the infamous "Gunpowder Plot," a terrorist plot to destroy King James I and the leadership of England's Protestant government, investigators faced the pernicious doctrine of "Equivocation." The doctrine taught that it was morally lawful to swear to civil authorities that you are telling the truth, but also to hold back essential information if you have good reason to that accords with your religious faith. So if the sheriff asks you, "Did you hide a priest last night?" you can swear that you did not, because actually it was your son or your wife that hid him. And because, as a believer in the old religion -- Roman Catholicism -- you believe God's law smiles on this deed of withholding truth for a higher cause, rather than forbids it. This is why the word shows up in Shakespeare's play and why the director of this "Shakespeare & Company" production has her actors emphasize it so strongly that it becomes a laugh line. The witches equivocate to Macbeth by withholding the whole truth with a clear intention to mislead when they tell him that he has nothing to fear until "Birnham Wood comes to Dunsinane" -- an apparent impossibility. Until, in a fashion, it happens. And also when they tell Macbeth that he need fear "no man of woman born." Macbeth hears what he wishes to hear instead of considering the source and maintaining a healthy skepticism. It's a fitting fate for a once good man turned tyrant, and hollowed out morally as a result. Duncan's son Malcolm, -- born by Caesarean -- will run him through in the end. That's why I missed seeing these telling scenes with the proverbial three witches in this "Shakespeare & Company" production. Bunsussen's show gave us only bare snippets of these encounters, and the three witches were economized to one. This RIFing also cheapens the historic context, since James I, England's new Stuart ruler, was a famous hunter of witches. We may not have witches or witch-hunters among us today (though 'witch-hunt' is daily thrown about), but our world has no shortage of 'strongmen' who lust after power. And find confirmation of their greatness everywhere. The omission of the witch scenes also slights the historical context because Shakespeare's play connects "Macbeth" to his own day by pointing out that England's new Scottish king is among Banquo's many descendants. The point is made by a daring device as the witches show Macbeth a charmed mirror in which he glimpses portraits of the long line of Banquo's descendants on his country's throne -- including new boy on the throne Jimmy (or 'Hamish') Stuart. Macbeth is after all "the Scottish play." It's doubtful that this theme for a play would have occurred to Shakespeare if the throne of England had not recently passed to a Scottish king. And revealing a play's connection to its own time helps connect it to our time as well -- because the through-stories in human history are always the same. Shakespeare's time had dynasties, powerful lords, and rule by tyrants called kings or queens. We have dynastic families, billionaires -- our last election featured the wife of a former President against a tax-evading oligarch -- and an endless parade of celebrity egos who believe they're hearing destiny's call to greatness. Not for nothing did the Constitutional framers create a governmental structure pitted with restraints on power. I questioned the need for so many of these myself when our gentle Duncan sat in the White House and suffered political impotence by a thousand cuts. Now, however, we see how easy it is when a monster sits on the throne, surrounded by liars, thieves and toadies, to ignore all restraints simply by denying the claims of reason and fact and moral decency. Maybe that's what Bloom meant when he wrote "Shakespeare sees to it that we are Macbeth; our identity with him is involuntary but inescapable." Today the Great Equivocator sits on the throne and tells us that what he told the foreign dictator yesterday is not what he meant to say. Today he will say something different that plays better at home. His sycophants and enablers will rally around and say, "Yes, boss. Yes, boss." History echoes in all our present moments. Will no one rid us of this turbulent beast?

Some aspects of Shakespeare's great political tragedy "Macbeth," director Melia Bensussen writes in her notes to the current production at Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, Mass., "resonated... with our cultural moment." Indeed. Would that 'moment' be the one when our current Usurper sells out his country's interests, alliances, values, and national pride to the two-bit totalitarian gangster who currently runs the long-running catastrophe generally known as Russia? "I thought about what moves and frightens us as contemporary audiences," Bensussen writes, and cites "how Macbeth's ambition, and belief in his imagination, lead to his destruction." She quotes the estimable literary critic Harold Bloom: "(The Macbeths) delight in their wickedness... Shakespeare rather dreadfully sees to it that we are Macbeth; our identity with him is involuntary but inescapable." Since 2016 there has been only one dominating influence on our 'cultural moment.' I won't say the name of the devil, but you know who I mean. What else can be meant by the 'cultural moment'? Me-too? The sins exposed there don't appear to have a precursor in this play since the only woman who matters, Lady Macbeth, is more actor than victim. You can see the "delight" Bloom speaks of in Bensussen's direction when Lady M. laughs in the course of her encouragement of her husband to murder and usurp. To throw caution to the winds and have the 'courage' to risk all for the prize of royal power, and be ruthless in obtaining it. They're playing the game of houses (or "Game of Thrones" as the TV series called it). Among other contenders for the Scottish crown we must count the head (Duncan's) currently wearing the crown, whose necked is saved by Macbeth's defeat of the rebels. Banquo, Macbeth's comrade in arms, is another rival. When we first meet Macbeth, he is triumphant in a just cause and likable. A furiously competent warrior, he takes pains to share the credit for the victory with Banquo. But Banquo must be eliminated because of the witches' prophecy. Though he will not become king himself, they prophesy, his descendants will. Our hero-villain naturally prefers his heirs to sit on the throne (even though he doesn't appear to have any). Other threats to his power include Duncan's son Malcolm. Suspecting correctly that he's a likely target of the conspiracy that murdered his father, he flees the castle before the Macbeths can take a run at him. Then there's Macduff. Though he evinces no appetite for the game of thrones power, simply because he is a name, a power center that might some day ally with Macbeth's enemies gathering across the border in England, the logic of tyranny says he must be eliminated. Ask any tyrant in our own season. Ask North Korea's Kim. Ask Putin why the oligarchs must be cut down to size before they become too popular or influential. Ask the Chinese Communist Party why no religious groups may operate in their country, no dissenters question their policies. Unlike history's more famous tyrants, Shakespeare's Macbeth has something they don't -- a conscience. An unavoidable capacity to experience, to feel, the reality of what he's doing. After he has Banquo murdered, Banquo's ghost ("in his blood") turns up at the dinner table. Macbeth's pathetic breakdown at the appearance of this ghost is black humor. Bensussen's production plays it for all that it's worth -- and then some; running the entire scene through twice. First with Banquo's ghostly appearance viewed by the audience. A second time with no 'ghost' on stage; the way, that is, the other guests would have perceived the occasion of Macbeth's mad-guilty ravings. The word the play's scholars use for this inconvenient capacity in a ruthless usurper is "imagination." Bensussen writes, "Macbeth too strongly believes in his own imagination..." He can, clearly, imagine himself king. But he can't help seeing the cost. To go back to that quote from Bloom: "Macbeth suffers intensely from knowing that he does evil, and that he must go on doing ever worse." Those last few words nail it. It's not enough to kill Macduff; you must kill his wife and children as well. No potential enemy can be left alive. Just as, to take a current instance, it is not enough to deny refuge to frightened people fleeing a threat to their lives. You must separate them from their children when you throw them in jail. That will show them. They won't try coming here again. But Macbeth, as I see it, chooses the path he does because he convinces himself that 'destiny' accords with his own desire for the crown. And, of course, the three witches help with that convincing. "Hail to thee, thane of Cawdor!" they greet him, before Macbeth has learned that Duncan has bestowed this title on him -- and "All hail, Macbeth, that shalt be king hereafter!" But the witches are (as they do again in a later scene), "equivocating" -- to use a term of moment. Shakespeare's moment that is. In the aftermath of the infamous "Gunpowder Plot," a terrorist plot to destroy King James I and the leadership of England's Protestant government, investigators faced the pernicious doctrine of "Equivocation." The doctrine taught that it was morally lawful to swear to civil authorities that you are telling the truth, but also to hold back essential information if you have good reason to that accords with your religious faith. So if the sheriff asks you, "Did you hide a priest last night?" you can swear that you did not, because actually it was your son or your wife that hid him. And because, as a believer in the old religion -- Roman Catholicism -- you believe God's law smiles on this deed of withholding truth for a higher cause, rather than forbids it. This is why the word shows up in Shakespeare's play and why the director of this "Shakespeare & Company" production has her actors emphasize it so strongly that it becomes a laugh line. The witches equivocate to Macbeth by withholding the whole truth with a clear intention to mislead when they tell him that he has nothing to fear until "Birnham Wood comes to Dunsinane" -- an apparent impossibility. Until, in a fashion, it happens. And also when they tell Macbeth that he need fear "no man of woman born." Macbeth hears what he wishes to hear instead of considering the source and maintaining a healthy skepticism. It's a fitting fate for a once good man turned tyrant, and hollowed out morally as a result. Duncan's son Malcolm, -- born by Caesarean -- will run him through in the end. That's why I missed seeing these telling scenes with the proverbial three witches in this "Shakespeare & Company" production. Bunsussen's show gave us only bare snippets of these encounters, and the three witches were economized to one. This RIFing also cheapens the historic context, since James I, England's new Stuart ruler, was a famous hunter of witches. We may not have witches or witch-hunters among us today (though 'witch-hunt' is daily thrown about), but our world has no shortage of 'strongmen' who lust after power. And find confirmation of their greatness everywhere. The omission of the witch scenes also slights the historical context because Shakespeare's play connects "Macbeth" to his own day by pointing out that England's new Scottish king is among Banquo's many descendants. The point is made by a daring device as the witches show Macbeth a charmed mirror in which he glimpses portraits of the long line of Banquo's descendants on his country's throne -- including new boy on the throne Jimmy (or 'Hamish') Stuart. Macbeth is after all "the Scottish play." It's doubtful that this theme for a play would have occurred to Shakespeare if the throne of England had not recently passed to a Scottish king. And revealing a play's connection to its own time helps connect it to our time as well -- because the through-stories in human history are always the same. Shakespeare's time had dynasties, powerful lords, and rule by tyrants called kings or queens. We have dynastic families, billionaires -- our last election featured the wife of a former President against a tax-evading oligarch -- and an endless parade of celebrity egos who believe they're hearing destiny's call to greatness. Not for nothing did the Constitutional framers create a governmental structure pitted with restraints on power. I questioned the need for so many of these myself when our gentle Duncan sat in the White House and suffered political impotence by a thousand cuts. Now, however, we see how easy it is when a monster sits on the throne, surrounded by liars, thieves and toadies, to ignore all restraints simply by denying the claims of reason and fact and moral decency. Maybe that's what Bloom meant when he wrote "Shakespeare sees to it that we are Macbeth; our identity with him is involuntary but inescapable." Today the Great Equivocator sits on the throne and tells us that what he told the foreign dictator yesterday is not what he meant to say. Today he will say something different that plays better at home. His sycophants and enablers will rally around and say, "Yes, boss. Yes, boss." History echoes in all our present moments. Will no one rid us of this turbulent beast?

Published on July 18, 2018 08:54

July 12, 2018

The Garden of the Seasons: July Friends, a Colorful Group Coping with a Strong Sun and a lot of Shade

Anne and I were discussing what is meant by the term "midsummer." In England Midsummer day (or 'night' as Shakespeare reminds us) is a magical time because it's the summer solstice. The day on which the sun reaches its highest point of the year in the northern hemisphere. This usage had no regard for the public school calendar. Kids are just getting out for summer vacation, so mid-summer for them (and their teachers) is late July. For a perennial flower garden in Massachusetts, I would say it's right about now. The sun is high, but beauty is fleeting. Many plants have already flowered and gone back to making strong roots, stems, and leaves for continued success. Maybe they're bearing seeds that haven't scattered yet.

Anne and I were discussing what is meant by the term "midsummer." In England Midsummer day (or 'night' as Shakespeare reminds us) is a magical time because it's the summer solstice. The day on which the sun reaches its highest point of the year in the northern hemisphere. This usage had no regard for the public school calendar. Kids are just getting out for summer vacation, so mid-summer for them (and their teachers) is late July. For a perennial flower garden in Massachusetts, I would say it's right about now. The sun is high, but beauty is fleeting. Many plants have already flowered and gone back to making strong roots, stems, and leaves for continued success. Maybe they're bearing seeds that haven't scattered yet.

Others are hitting their stride. It's daylily month. Hydrangeas are flourishing. Many roses bloom through this month. And many of us indulge in summer annuals that take a month or two to reach their prime. One of these is the orange hibiscus, pictured in the top photo.

Others are hitting their stride. It's daylily month. Hydrangeas are flourishing. Many roses bloom through this month. And many of us indulge in summer annuals that take a month or two to reach their prime. One of these is the orange hibiscus, pictured in the top photo.

I buy these hibiscus and pot them for a season to help celebrate summer every year. They're tropical or semitropical flower. The big ones I bring indoors for the winter; some of them make it and are good for a second go-around outdoors, some don't. In either case they know they haven't spent the winter in Florida or southern California.

I buy these hibiscus and pot them for a season to help celebrate summer every year. They're tropical or semitropical flower. The big ones I bring indoors for the winter; some of them make it and are good for a second go-around outdoors, some don't. In either case they know they haven't spent the winter in Florida or southern California.

Spiderwort (second photo down) move in anywhere you let them. When they all bloom at once, on a dark morning or in blazing sunshine (doesn't seem to matter) they can be stunning. When they start to tire and the weather gets dry, they just flop all over the place. Now the question is whether to try put up with them in hopes of later bloom, or cut them down. I do a little of both.

Spiderwort (second photo down) move in anywhere you let them. When they all bloom at once, on a dark morning or in blazing sunshine (doesn't seem to matter) they can be stunning. When they start to tire and the weather gets dry, they just flop all over the place. Now the question is whether to try put up with them in hopes of later bloom, or cut them down. I do a little of both.

Astilbe, blooming red and white in the third photo down, are going good in early July. A plant widely recommended for shady spots. they're surviving here where it's shady more than half the time; but the high sun of late June and early July stays on them for a longer piece of the day. If only these blooms would last all summer -- that's what we say about most perennials.

Astilbe, blooming red and white in the third photo down, are going good in early July. A plant widely recommended for shady spots. they're surviving here where it's shady more than half the time; but the high sun of late June and early July stays on them for a longer piece of the day. If only these blooms would last all summer -- that's what we say about most perennials.

This Spirea (fourth down) blooms in a lovely dark pink to reddish color. Somehow they never last -- but you've just heard that story. However, if you conscientiously dead-head all the faded blooms, you may be rewarded with a good second show. That's my job for today.

This Spirea (fourth down) blooms in a lovely dark pink to reddish color. Somehow they never last -- but you've just heard that story. However, if you conscientiously dead-head all the faded blooms, you may be rewarded with a good second show. That's my job for today.

These daylilies (fifth down) have a lovely soft color. They tolerate neglect and crowding as you tell from this photo. And partial sun. I've been trying to collect different varieties of this remarkably versatile plant (though I forget to write down the names) so that the differences in blooming dates will keep the color flowing for over a month at least. The native orange daylilies start in late June. Some other varieties have yet to begin to bloom. The pale yellow ones here are finishing up. Rose Campion (sixth down) is another champion of midsummer, late June to early July. Their dark red flowers (that name them, I suppose) contrast nicely with the gray stems and leaves. I don't know anything more about them, but that's enough for me.

These daylilies (fifth down) have a lovely soft color. They tolerate neglect and crowding as you tell from this photo. And partial sun. I've been trying to collect different varieties of this remarkably versatile plant (though I forget to write down the names) so that the differences in blooming dates will keep the color flowing for over a month at least. The native orange daylilies start in late June. Some other varieties have yet to begin to bloom. The pale yellow ones here are finishing up. Rose Campion (sixth down) is another champion of midsummer, late June to early July. Their dark red flowers (that name them, I suppose) contrast nicely with the gray stems and leaves. I don't know anything more about them, but that's enough for me.

Another plant with a nice color contrast is the coral bell (seventh down), with delicate pink flowers above dark purplish-green leaves. Again, it's highly recommended as flowering perennial that blooms without too much sun. Most of all the plants growing here in our the back garden are labeled semi-shade. That's a cleome blooming in the lower right of this pic.

Another plant with a nice color contrast is the coral bell (seventh down), with delicate pink flowers above dark purplish-green leaves. Again, it's highly recommended as flowering perennial that blooms without too much sun. Most of all the plants growing here in our the back garden are labeled semi-shade. That's a cleome blooming in the lower right of this pic.

Lamium (sometimes sold as "spotted dead nettle") is shown here (eighth down) growing beside the newly reconstructed stone and gravel path. Everybody does their road work in summer Lace-cap Hydrangea (ninth down) shows in this photo exactly where its name came from. The plant grows expansively, but hard to believe, truly wilts in the sun. In our front garden sun is more prevalent, and in sunny, dry periods (like today) they require watering every day (yes, also on today's to-do list). A different daylily with a darker yellow color is pictured here in the last photo. I love this tint and should have kept that name tag for this cultivar. Remembering the names of plant varieties is one of those activities they recommend for improving your memory. I think I'm going in the wrong direction.

Lamium (sometimes sold as "spotted dead nettle") is shown here (eighth down) growing beside the newly reconstructed stone and gravel path. Everybody does their road work in summer Lace-cap Hydrangea (ninth down) shows in this photo exactly where its name came from. The plant grows expansively, but hard to believe, truly wilts in the sun. In our front garden sun is more prevalent, and in sunny, dry periods (like today) they require watering every day (yes, also on today's to-do list). A different daylily with a darker yellow color is pictured here in the last photo. I love this tint and should have kept that name tag for this cultivar. Remembering the names of plant varieties is one of those activities they recommend for improving your memory. I think I'm going in the wrong direction.

Published on July 12, 2018 12:52

July 11, 2018

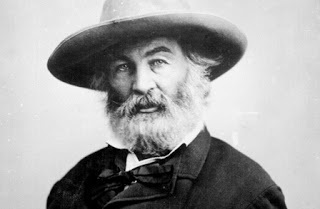

The Garden of Verse: Climbing the Heights of Long Island in Walt Whitman's Hills

Some people call the summit West Hill. Today it's called Jayne's Hill by the park department.

Some people call the summit West Hill. Today it's called Jayne's Hill by the park department.

Walt Whitman called it the highest point on Long Island, which it is, and spoke of its marvelous water views, a perspective nolonger available because the trees have grown up on all the low, rambling hills in this lovely spot now known as West Hills County Park.

Walt Whitman called it the highest point on Long Island, which it is, and spoke of its marvelous water views, a perspective nolonger available because the trees have grown up on all the low, rambling hills in this lovely spot now known as West Hills County Park.The poet who was born nearby, described a "view of thirty or forty, or even fifty or more miles, especially to the east and south and southwest: the Atlantic Ocean to the latter points in the distance - a glimpse or so of Long Island Sound to the north." We walked in West Hills for the first time ever on a lovely Saturday in June, the day of our niece Emily Knox's wedding. With a few hours to go before church time, we looked for some place near our Huntington motel to take a good walk. This wooded county park was it. Given the beautiful dry weather, we must have lucked into one of the best days of the year to hike in these gentle hills. The date was about a week before the Summer Solstice, and we found the wooded trail awash in mountain laurel in full bloom. The summit is marked by a boulder bearing a plaque inscribed with a reference to Walt Whitman's "Starting From Paumanok," a long autobiographical poem titled after the Indian name for Long Island. The poem appeared in the first edition of "Leaves of Grass." The Walt Whitman Birthplace, located at 246 Old Walt Whitman Road in Huntington Station, is a Federalist style farm house once owned by a family with roots in this part of Long Island dating back to the 17th century. While Walt's father moved the family to Brooklyn in his son's childhood, family connections brought the poet back to this part of Long Island frequently Generally regarded as America's greatest poet, and the most influential worldwide, Whitman became known as the poet of democracy. In an introductory essay to a comprehensive volume of the famous work, "Leaves of Grass," scholar Sculley Bradley pointed out that democracy for Whitman meant more than counting the votes. The poet regarded democracy "as the order of nature. It embraced every conceivable condition of life for mankind. Its essence was love, extending in universal justice around the world." For me, this conception of a mundane and what has become an almost meaningless word, Whitman's idea of democracy sounds like a humanistic interpretation of the theory of evolution. Whitman believed that democracy was moving purposively forward, despite all of humanity's flaws, toward an end Whitman called "amelioration," a term philosophers in his time used to mean "things are getting better" or at least less gruelingly bad. Age by age, Walt Whitman believed, human beings were working the kinks out of their society. Whitman was hardly blind to the imperfections of rowdy, self-serving 19th century America. A big city newspaper editor in New York (and, briefly, New Orleans), he witnessed political corruption, poverty, and bigotry. A volunteer nurse during the Civil War (wounds dresser, essentially) in a medically brutal time, he provided companionship and kindness for maimed and dying men. He worked as a civil servant in Washington D.C. to support his volunteer work and writing. In the climate of post Civil War America, a government job gave him a front-row seat on a corrupt era in national politics matched only -- dare I say it? -- by today's open market for purchasing Congressmen spawned by "Citizens United." After Whitman published the first, modestly sized edition of "Leaves of Grass" in 1855, his radically original poetry drew praise from America's reigning intellectual god, Ralph Waldo Emerson. In a famous letter Emerson wrote him, "I hail you at the beginning of a great career, which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere, for such a start." That foreground, Bradley writes in his essay, "was an opulent inheritance of American idealism that could survive the later disillusionments of journalism, the corruption of men, and the catastrophes of war." Sounds like a good summation to me; only I'm not sure journalists these days carry around any illusions to lose. Anne, Sonya and I were happy to find what may be the best nature walk on Long Island, even if we couldn't see scores of miles out to sea. That one of the most thrilling and influential voices in modern literature shared this perspective and on occasion this woodland ramble makes West Hills park especially memorable. "And what I assume you shall assume," Walt Whitman tells us in his great poem "Song of Myself." "For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you. From which I take it that -- good times or bad -- we're all in this together.

Published on July 11, 2018 20:58

July 3, 2018

The Garden of Verse: Hard This Year to Feel the Love on Our Nation's Birthday

Well it's July, and summer doesn't get more "mid" than this. It's a good time of year for a holiday to celebrate our country's birth, but this year what I'm feeling is -- well, what's the opposite of nostalgia? A sickness that is not composed of "longing"?

Well it's July, and summer doesn't get more "mid" than this. It's a good time of year for a holiday to celebrate our country's birth, but this year what I'm feeling is -- well, what's the opposite of nostalgia? A sickness that is not composed of "longing"? In America we proudly celebrate the birth of the first nation in modern times founded on a system of self-government.

But what if that system isn't working? As is rather spectacularly the case in 2018.

So when our editor at Verse-Virtual.com proposed the theme of "America" for the July issue, I felt the compulsion to -- 'rally around the flag'? Is that a phrase we can use when the flag has been taken prisoner by a scoundrel of the first order and a crew of pea-brained bullies?

Nevertheless before launching into my screed I began this poem with a reminiscent look at the conditions of life fifty years ago in America.

You. Me. RFK.

Fifty years ago,

not much time in the fossil record

(by contemporary measure we're all fossils now)

but a considerable bite in a lifespan

No phones, no careers, no parents to speak of

No job beyond short-term janitoring in college dormitories

Viewed in the antique light of old snapshots, recollected in selfish nostalgia

like something once seen in a movie

Days bumbling from pot party for lunch

to adolescent sulk over some fresh tease

What did anybody ever see in that early attempt at me?

...

To see what else was happening fifty years ago, and a screed on what's happening today read the rest of my poem at http://www.verse-virtual.com/robert-knox-2018-july.html.

Work by 39 poets in all can be found at http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-and-articles.html

And, regardless of my bad-mouthing, Happy Fourth!

Published on July 03, 2018 21:41

June 30, 2018

Trees Are Behind Everything: The One Book You Need to Read This Summer (or any other time of year) is "The Overstory" by Richard Powers

Richard Power's recently published novel, "The Overstory," a book about what the trees are trying to tell us -- and we're not listening -- could easily serve as the basis for a new religion. If my response to the book were any sort of reliable measure of popular feeling, it might do just that. But since I am never a good measure of popular opinion, it will probably just be another great book that fails to shake up human complacency sufficiently to save us from the destructive path human society is taking.

Richard Power's recently published novel, "The Overstory," a book about what the trees are trying to tell us -- and we're not listening -- could easily serve as the basis for a new religion. If my response to the book were any sort of reliable measure of popular feeling, it might do just that. But since I am never a good measure of popular opinion, it will probably just be another great book that fails to shake up human complacency sufficiently to save us from the destructive path human society is taking.In which case I'll proceed to talking it up in my usual fashion, and try to put a lid on the superlatives. Let's start with a statement by Powers made in an interview after he published this epic centered on a species-other-than-humans, a goal matched only by "Moby Dick," the difference being that this book is steadily readable: "Trees are among the very largest, longest-lived, most successful, and most collaboratively social forms of life on the planet. They live, all at once, in the sky, on the surface, and under the ground. They make the atmosphere, filter the Earth’s waters, and help to regulate the temperature... Deforestation, by the way, is the second largest contributor to greenhouse gasses, after burning fossil fuel." Trees made the world; our world, "The Overstory" tells us. Aside from the oceans, the normative state of Planet Earth is forest: "It's the earth's chief way of being." To summarize, the air we breathe evolved through the interaction of sky and green plants. All our food, fresh water, and medicines are the products of green plants. Trees are the most fully evolved organisms on our planet. This isn't "our world, with trees in it," playing a supportive role by being so "useful," as one of the main characters in "The Overstory" observes. "It's a world of trees, where humans have just arrived." And yet, as the same character points out to a lecture hall of well-educated politely attentive academics -- (but are they getting it?) -- "You and the tree in your backyard come from a common ancestor. A billion and a half years ago you parted ways.... You and the tree still share a quarter of your genes." Yes, human characters populate this book, as they do other novels. People do matter in this story. Characters are introduced in separate longish stories at the book's start. Their lives have interesting or even crucial intersections with trees, and they come together during the "eco-wars" in northern California in the late 1980s and '90s, when protestors tried to save the last American "old forest," with its stash of huge irreplaceable redwoods, from the lumber industry. It's shocking to me that I knew so little about these events. (I was reading newspapers then, wasn't it?) As Powers tells it, the eco-warriors lose these wars, or at least the big battles (though apparently some pieces of the forest were saved). This central crux of the novel holds most of the book's big dramatic action, and the author refrains from giving us big, last-minute changes at his book's conclusion. This is the narrative equivalent of writing "The Iliad" with Troy falling in the middle; then watching the scattered Trojan survivors try to get on with their lives. (That's actually the plot of the Vergil's "Aeneid"). So while people matter and human lives are always being lived on the page, it's what they learn about humankind's relationship with Planet Earth that's the central issue. That's why this is a different, potentially path-finding novel. We know the ending of any human being's story; people die. What of the trees' story? What of the future of life itself on Planet Earth? Patricia Westerford, the character who offers these large, scientific conclusions, is decades ahead of her time in discovering remarkable truths about the life of trees -- that they are social beings, they communicate, they form what Powers calls 'a neighborhood watch' to protect themselves against diseases and insect infestations -- that only in recent years have gave gained wide acceptance in the life sciences. Among Westerford's (and Powers') other messages and warnings: Earth's forests are disappearing at a rapid rate. "The annual loss: One billion trees.... Half the world's species will be gone by the century's end." Earth's "wild uncatalogued forests are melting away." Unidentified species in earth's Third World forests, in Brazil or Indonesia or other unstudied ecologies, are going extinct before they can be identified and studied: "Tens of thousands of trees we know nothing about." Some more: "One trillion leaves are lost every day." There are only "half as many trees in the world today," Westerford (and Powers) point out, "as when we climbed down from them." "It's like burning down the library, the art museum, pharmacy and hall of records, all at once." Another character is a Vietnam veteran who helped destroy tropical forests with Agent Orange. Back in the US, he is shocked at the loss of national forests on federally owned lands in Western states and dedicates a decade of his life to replanting, one at a time by hand, ten thousand trees cut down by lumber companies. Later, working as a solitary caretaker at a remote tourist site abandoned in the Montana winter, Douglas Pavlicek gazes on a wild mountain side and has this revelation: "We're cashing in a billion years of savings bonds and blowing it on assorted bling." "Why," he asks, "is it easy to see on a mountain, impossible to see when you join billions of people doubling down on the status quo?" The answer is what another character, who becomes a prominent academic psychologist, calls "the bystander effect." Example: If someone needs help, the more people nearby, the less likely he or she is to receive it because everyone assumes someone else will go help. If there's only a couple of people around, somebody will rush in. The extrapolation: The more time you spend with any group, the more likely you are to think like everybody else. A 'society' or nation or civilization or 'economy' is just that sort of group. So we keep cutting down forests, and otherwise consuming all of Earth's natural resources, assuming that it's somebody else's job to think about the consequences. Frankly, Powers' "The Overstory" is the most radical analysis of what the future holds for the human species (and life on Earth) that I've read anywhere. The current vogue for dystopian fiction, concentrating on the potential for human evil when things get tough, isn't half as searching. When human beings are being bad to other human beings, the possibility exists that some human beings will become better, or the good ones will somehow overthrow the bad ones. In "The Overstory," the implication is that human nature is itself the problem. In the scary future scenarios suggested by scientific analyses such as Elizabeth Kolbert's "The Sixth Extinction," the extrapolation of current trends of the current geologic age lately christened the "Anthropocene" -- a word meaning the planet's domination by humans -- focuses on the rapid, appalling extinction of other species because of environmental changes we have caused. "The Overstory" suggests we can't do anything but keep making things worse. "The only thing we know to do is grow," Westerford says. "Growth all the way up to the cliff and over. No other possibility." We're the problem. For the trees, the environment and, ultimately, for ourselves as well. To suggest some hope, I'll go back to that interview with Powers, in which he quotes from American's other great literary writer on the subject of trees -- Thoreau. "One way or another, we humans are on our way to becoming something else. The question is rather how gracefully or how violently we make that Ovidian metamorphosis. We will learn, as Thoreau says, to resign ourselves to the influence of the earth, or we will disappear."

Published on June 30, 2018 14:50

June 28, 2018

Garden of the Seasons: The Long Days and Happy Hearts of June

More updates from the Country of June.

More updates from the Country of June.  Lamium, or "spotted dead nettle," proved to be one of the year's best recovery projects. After I weeded everything else out of its designated patch, back beside the Goat's Beard and underneath the Japanese maple, the plant spread its two-toned leaves and held up its pink flowers in more abundance than I've noted in previous summers.

Lamium, or "spotted dead nettle," proved to be one of the year's best recovery projects. After I weeded everything else out of its designated patch, back beside the Goat's Beard and underneath the Japanese maple, the plant spread its two-toned leaves and held up its pink flowers in more abundance than I've noted in previous summers. Abetted by a selection of annuals (and, yes, a lot more weeding), a colorful patch in the back of the garden with midday sun. (esp in June when the sun's high). Here are the dark pink Dianthus, a few Cosmos with similarly tinted blooms, and blue Lobelia.

Spikes of a smaller Foxglove variety keep pushing up year after in a section of the back garden that grows shadier from a young expanding maple tree behind and above them.

Deep red blossoms from a traditional rose vine are blooming strongly this year. We found two of these vines straggling through the years when we moved in. After some pruning and fertilizing they have been pushing out classic roses every year.

Deep red blossoms from a traditional rose vine are blooming strongly this year. We found two of these vines straggling through the years when we moved in. After some pruning and fertilizing they have been pushing out classic roses every year.  Asiatic lilies, that's how they're marketed, have come back strong. Years ago, our "ornamental" lilies were decimated like everybody else's by the the plague of invasive red beetles. The beetles were actually beautiful to look at, but what they did to the plants was not.

Asiatic lilies, that's how they're marketed, have come back strong. Years ago, our "ornamental" lilies were decimated like everybody else's by the the plague of invasive red beetles. The beetles were actually beautiful to look at, but what they did to the plants was not.  The roses pictured beneath the lilies are a contemporary "knockout" cultivar. This photo was taken early in the month. The blossoms have ten-tupled since. Our neighbor has about six of these plants, all of them ferocious with color.

The roses pictured beneath the lilies are a contemporary "knockout" cultivar. This photo was taken early in the month. The blossoms have ten-tupled since. Our neighbor has about six of these plants, all of them ferocious with color. The white Shasta daisies go back to one of our earliest plantings. I transplanted them all over. This group grows on a bit of soil we call the "sidewalk strip, turning up those happy faces to the garbage men and other passing traffic. I wish they would bloom all summer, but I'm unable to get a second bloom from them even after assiduously dead-heading

Next down are the yellow flowers of the evening primrose. This plant came from my mother, via my sister Gwen. A strong June bloomer, that spreads itself all over creation, even blooming in some mostly-shade areas such as here, under a big maple.

Next down are the yellow flowers of the evening primrose. This plant came from my mother, via my sister Gwen. A strong June bloomer, that spreads itself all over creation, even blooming in some mostly-shade areas such as here, under a big maple.  The bottom photo is a selection of spider wort, a plant I'd never made the acquaintance of until it found us here. It too migrates everywhere, crowding in thick patches. The purple blooms concentrate in June. Then the leaves just hang around all summer, taunting you with the prospect of repeating bloomers.

The bottom photo is a selection of spider wort, a plant I'd never made the acquaintance of until it found us here. It too migrates everywhere, crowding in thick patches. The purple blooms concentrate in June. Then the leaves just hang around all summer, taunting you with the prospect of repeating bloomers. As the month draws to its end, and the days stay long, things are already starting to look a little different.

Time to pull some weeds and take some more pictures.

Published on June 28, 2018 22:09

June 27, 2018

Garden of the Seasons: More Cheers for June

The month of June, and this will not come as news to anyone, is a good time to be outdoors. We present first off here for your inspection, the juvenile member of the North American Robin. The bird-finder website suggests this identification. I naively assumed that robins had red breasts, or orangish ones, or else they didn't. But it appears they may also have "speckled" breasts in adolescence. If that's the case, I'm hoping this adolescent bird grows up soon, because I regularly encounter him on the ground, even on paved ground such as the patio, apparently looking for a menu or waiting for the serving-person to show up. And he's not in a hurry to get away.

The month of June, and this will not come as news to anyone, is a good time to be outdoors. We present first off here for your inspection, the juvenile member of the North American Robin. The bird-finder website suggests this identification. I naively assumed that robins had red breasts, or orangish ones, or else they didn't. But it appears they may also have "speckled" breasts in adolescence. If that's the case, I'm hoping this adolescent bird grows up soon, because I regularly encounter him on the ground, even on paved ground such as the patio, apparently looking for a menu or waiting for the serving-person to show up. And he's not in a hurry to get away.

In the next photo, we see the lower branches of the fruit-bearing mulberry tree, that provides evident reason for this bird's continuing presence. Others too, of course. Including a male cardinal yesterday. The best reason for having a tree that drops these messy berries all month is the level of chirping and calling that sometimes persists for whole sunny hours or longer on beautiful afternoons this month.

In the next photo, we see the lower branches of the fruit-bearing mulberry tree, that provides evident reason for this bird's continuing presence. Others too, of course. Including a male cardinal yesterday. The best reason for having a tree that drops these messy berries all month is the level of chirping and calling that sometimes persists for whole sunny hours or longer on beautiful afternoons this month.

Lots going on in the plant world as well this month, of course. The plant called the purple Penstemon, which I planted in one place years ago, has divided itself in half and now shows up in two places. I saw a bunch of these living large in full sun in a friend's front yard. That's what they like. This spot in our garden is definitely part-shade. Coral bells (at left). Too much sun when I took this photo to see the purplish stripes in the plant's dark green leaves. This light also washes out the color in the plant's delicate flowers.

Lots going on in the plant world as well this month, of course. The plant called the purple Penstemon, which I planted in one place years ago, has divided itself in half and now shows up in two places. I saw a bunch of these living large in full sun in a friend's front yard. That's what they like. This spot in our garden is definitely part-shade. Coral bells (at left). Too much sun when I took this photo to see the purplish stripes in the plant's dark green leaves. This light also washes out the color in the plant's delicate flowers.

A mid-sized Bell Flower, species name "Campanula," sends up a few blossoms in our part-sun, part-shade back garden. The daisies or asters in the next photo down, I'm not sure what they are, send up tall slender stems. When all the blossoms open at once in late June, it makes the show we see here. It may be Fleabane, an American wildflower.

A mid-sized Bell Flower, species name "Campanula," sends up a few blossoms in our part-sun, part-shade back garden. The daisies or asters in the next photo down, I'm not sure what they are, send up tall slender stems. When all the blossoms open at once in late June, it makes the show we see here. It may be Fleabane, an American wildflower.

Another anonymous contributor is pictured at the bottom of the post. A hardy groundcover, it creeps close to the earth and puts up yellow flowers for a couple weeks in June. Lady's Mantle, below the putative Fleabane, appears perfectly content with its ration of sunshine, offering plenty of pale yellow flowers in the months of May and June. Unlike most summer perennials, it spreads horizontally rather than shoots up vertically.

Another anonymous contributor is pictured at the bottom of the post. A hardy groundcover, it creeps close to the earth and puts up yellow flowers for a couple weeks in June. Lady's Mantle, below the putative Fleabane, appears perfectly content with its ration of sunshine, offering plenty of pale yellow flowers in the months of May and June. Unlike most summer perennials, it spreads horizontally rather than shoots up vertically.

Goat's Beard, pictured brightly against the dramatic shade of the background, grows below a shade tree. After the neighbor cut down his tree, it grew even better.

Goat's Beard, pictured brightly against the dramatic shade of the background, grows below a shade tree. After the neighbor cut down his tree, it grew even better.

Lamium, or "spotted dead nettle," is one of this year's top recovery projects. That is, I weeded everything else out its plot, and the obliging plant spread its two-toned leaves and held up its pink flowers. (The software apparently ate this photo; I'll include it in the next post.) Lots more June bloomers in the next post, which better come soon because I'm running out of June.

Lamium, or "spotted dead nettle," is one of this year's top recovery projects. That is, I weeded everything else out its plot, and the obliging plant spread its two-toned leaves and held up its pink flowers. (The software apparently ate this photo; I'll include it in the next post.) Lots more June bloomers in the next post, which better come soon because I'm running out of June.

Published on June 27, 2018 22:16