Robert Knox's Blog, page 16

December 18, 2018

The Garden of Literature: In Defense of Reading -- Especially Good Books

A book reviewer, critic, and novelist in his own 'write,' William Giraldi writes longish magazine pieces for The New Republic and other mainstream journals. That occupation, unfortunately, is a ceaselessly declining niche, so his new book, titled "American Audacity: In Defense of Literary Daring," is particularly deserving of attention. Leaving aside the question of "daring," what I took from this book was a learned and insightful defense of good literature, period. It's a book full of memorable quotes and judgments, those of writers and other critics, and some assessments offered by Giraldi himself.

A book reviewer, critic, and novelist in his own 'write,' William Giraldi writes longish magazine pieces for The New Republic and other mainstream journals. That occupation, unfortunately, is a ceaselessly declining niche, so his new book, titled "American Audacity: In Defense of Literary Daring," is particularly deserving of attention. Leaving aside the question of "daring," what I took from this book was a learned and insightful defense of good literature, period. It's a book full of memorable quotes and judgments, those of writers and other critics, and some assessments offered by Giraldi himself.Of these last, the one that meant the most to me is this: "Storytelling was, remember, the first entertainment and our earliest font of information, our around-the-fire manna for those wide-eyed Paleolithic persons who became us." This comment appears in his lengthy essay on novelist William Gurganis, whose best known book is "Oldest Confederate Widow tells All." I haven't read that book -- some who have confided that 'all' rather more than a reader needed -- but Giraldi's assessment of the seminal role of the storyteller in human evolution appears to me to be worth repeating, and restating as often as possible. Those of us who read fiction, especially literary fiction, know why we do it: to confront once the nature of human existence, with all its secrets, endless variations and unplumbable depths. We need to plumb them anyway. We will die trying. Of course, not only do we get our fill of stories by reading books, we attend theatrical performances, and gorge ourselves on cinematic, televised and digitally streamed narratives of the actions and fates of human beings much like ourselves simply by being human. And we talk (some of us too much; others perhaps too little) about what happens in our lives. Because we need both to tell. And to listen. Storytelling saves us from isolation. It gets into our heads. It gives us ideas about how to cope with that terrible burden the 20th century gave us a name for that we are still using -- the "existential burden" of the human condition. Yes, it's a condition -- though people make fun of the term -- and yes, we're dying from it. In the meantime, we're here. What do we do with ourselves? How do we do it? And, just as important, how do we think about everything -- good, bad, and indifferent -- that happens in our lives and in our world? Stories give us models, examples, new horizons, ancient reinforcements, challenges, voyeuristic lives to live. Since the many-sided usefulness of stories and storytelling is an endless subject, I will arbitrarily cease pursuing it in order to offer a few shining moments from Giraldi's collection of commentaries. Some of these are quotations from the literary canon that also prove endlessly useful, such as this brief, but perfect description of one of the most commonplace events in human experience: "the violet hour, the evening hour that strives/ Homeward." This comes from (of all places) T.S. Eliot's "The Wasteland." The violet hour does arrive everyday, and it's always a wonder. If we lose sight of its magic, we are forgetting one those "fundamental things" that, as the song says, "apply." Critic Wendy Lesser supplies the phrase "the serious pleasure of books." Often in the course of his essays, Giraldi references the idea that the major inducement for reading is 'pleasure,' and near his volume's end he suggests it is life's greatest source of enduring pleasure -- an explanation for why people go on reading on their death beds. Since, clearly, there no longer appears to be any practical advantage to it. "(T)he knowledge of literature still gives the most pleasure of all," he writes. Human life offers many different kinds of pleasure. So even a simple adjective like 'serious' may go some way to explaining the uses of reading, literature, essays, stories, poetry -- the whole bookish shebang. At another point in his consideration of literature and death, Giraldi quotes from Walt Whitman: "Let me glide noiselessly forth." Whitman was old when he wrote that, but when he was young he had much to say about death as well, including these famous lines:“All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses,/ And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.” A famous tome from the Middle Ages (not mentioned in Giraldi's essay) is titled "The Consolations of Philosophy." The consolations of poetry may be even better. Many of the longer pieces in this book are essays that justify the book's subtitle "In Defense of Literary Daring" treat writers of our time that the author admires. Among these are contemporary writers such as Gurganus, Padgett Powell, Barry Hannah, and a half dozen others that I have not sampled at all (I tend to stick to my favorites). His insights into writers I am familiar with -- James Baldwin and classic 19th century masters Melville and Poe -- are interesting, and I found pieces on these authors well worth reading. Giraldi's assessment of some contemporary fiction writers I have read -- such as Dennis Johnson and Cormac McCarthy -- were interesting, though I think limited. His two essays on McCarthy struck me as narrowly hung up on the issue of violence in that author's work, especially since Giraldi acknowledged not having read the author's highly praised "Border Trilogy" which I found to be among the most affecting works of fiction published in the last three or four decades. The acts of tragic violence in these three books did not put their other virtues in the shade. Oedipus dies at the end of his trilogy, but that does make his story less engaging. So does Hamlet at the end of his short life -- but long-lived play. The book ends, anticlimactically, with a negative review of a book by Richard Ford that I've never encountered. Ford is capable of duds, and I read one (though not the one reviewed here), but for a period of years I waited eagerly for each new title by this prolific author. His works engaged contemporary American life in the latter decades of the 20th century in a meaningful, engaging way. I'd call them 'a serious pleasure.' And then there are the essays about 'the critics.' While I recognize the names of those to whom Giraldi devotes essays, I haven't read their tomes -- with one exception. And I whole-heartedly agree with Giraldi's assessment that the undisputed chief divinity of our era's literary critics is Harold Bloom, a good number of whose books I have read with pleasure and astonishment. Giraldi's summary of Bloom's career and his role in our era's academic controversies (where critics live) is intriguing, perceptive, and highly useful to anyone who is not a career academic in this field. Bottom line: in Bloom's view great literature is about love, beauty, and aesthetic pleasure. Some quotes from Bloom: "you will not become a better or more moral citizen by reading Emerson." You may, however, Giraldi summarizes the argument, "learn how to be yourself." Pursuing this point, he asks why is the "aesthetic" pleasure of literature essential? Because, Bloom answers, "we live by and in moments raised in quality by aesthetic apprehension." Our goal in life, as many have answered, is "more life." It's not a quantitative evaluation. Literature, and the other arts, offer us that "more." Bloom's early, groundbreaking criticism was encapsulated by the phrase "the anxiety of influence." Great writers, Bloom believed, were supremely aware of the works of the great writers who preceded them. But it's not writers suffering the burden of looking over their shoulders at the intimidating greatness of a Milton or a Shakespeare that is meant by "anxiety" in this theory, but the notion that something happens in their work to make it more original. "In this, my final statement on the subject," Bloom has stated, "I define influence simply as literary love, tempered by defense." Another of Bloom's contributions is the notion of "creative misreading" by "strong" poets of their predecessors' works. "Without Tennyson's reading of Keats, we would have almost no Tennyson," he states. Bloom's defense of the literary canon against narrow political interpretations of great works by those academics he christened "the School of Resentment" is clearly and strongly defended in turn by Giraldi. Again, this book offers a good explanation of the controversy for readers who may not have come across these terms, ideas, or academic battles. A few other judgments from Bloom out of the many major insights that Giraldi happily chose to share with us. On the first English Bible, produced and written by printer and literary genius William Tyndale: "Tyndale's New Testament affected all subsequent expression in the English language." He's responsible, scholars now say, for the beloved language of the famous King James Bible. Bloom's theory on Shakespeare's invention of the modern idea of a literary 'character' is summed up in this pertinent quote: Shakespeare's "characters change while overhearing themselves." Finally, Bloom's love of the pioneering American poet Walt Whitman is evoked in this beautifully learned encomium: "As Adam early in the morning, Walt is the unfailing God-man, our androgyne." I'm giving the last word here to author Giraldi. Keep in mind that you're hearing this from somebody who in addition to his critical essays writes works of literary fiction: "Publishing is a business in which writers of ironclad intelligence and integrity must watch in paralysis as second-rate crowd-pleasers are lavishly lauded and feted, and so these writers cheer themselves up by imagining that their laurels will arrive after their deaths, when society finally gets wise and realizes the injustices it heaped upon genius." For the record, he doesn't believe it happens often. "American Audacity" was published in 2018 by Norton. You can find it on Amazon. I found the copy I read in my library.

Published on December 18, 2018 14:32

December 17, 2018

Science and Politics: Trump is Not the Biggest Issue, He’s Only the Biggest Distraction. Climate Change is the True Apocalypse and Americans Are Limping Toward It Like Lambs to the Slaughterhouse

Anyone who doesn’t have his head up his posterior has probably noticed that humanity’s lease on Planet Earth is running out fast. Cataclysmic atmospheric warming, as a direct result of human activity, is the singular life-and-death threat the human race faces. That understanding, repressed or sublimated into comic book nightmares, is the reason why so many of our arts and entertainment narratives deal with apocalypses and dystopias, planetary disasters of all sorts: We know this. It’s in our dreams, our movies, and our books. Our time is running out, and our lease on Earth shortens every day in which we do nothing to change our ways. This knowledge is lodged firmly in our subconscious, even if the leaders chosen by fear of change refuse to acknowledge it.

Anyone who doesn’t have his head up his posterior has probably noticed that humanity’s lease on Planet Earth is running out fast. Cataclysmic atmospheric warming, as a direct result of human activity, is the singular life-and-death threat the human race faces. That understanding, repressed or sublimated into comic book nightmares, is the reason why so many of our arts and entertainment narratives deal with apocalypses and dystopias, planetary disasters of all sorts: We know this. It’s in our dreams, our movies, and our books. Our time is running out, and our lease on Earth shortens every day in which we do nothing to change our ways. This knowledge is lodged firmly in our subconscious, even if the leaders chosen by fear of change refuse to acknowledge it.

Our political and corporate leaders have known about the threat posed by rapid climate change for well over 30 years now. Our leaders simply behave as if denying the truth will somehow cause this reality to shrug and go away. It will not. No superhero can suck the greenhouse gases out of our atmosphere and our oceans. The aliens will not arrive to save us. The ‘rapture’ will give way to The Rupture, and our planetary lease will be permanently broken because we couldn’t be bothered to take care of the place. Face it, folks, barring some apparently super-human course correction we are living in what may prove to be the human centuries. Our descendants in subsequent centuries, if there are any, will no longer be living in the "Anthropocene," the era of human domination the planet. But in the era of human diminishment, as they struggle to survive increasingly hostile conditions. And even before the 21st century gets too much further along, our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren will likely be struggling with conditions those of us born in more fortunate (though careless) times would regard as unbearable and unimaginable. What are the countries of the world doing to mitigate the disaster? Making inadequate promises they fail to live up. What are our political and business leaders doing? Sticking their heads in the sand, on which they build their mansions of narcissistic self-absorption. “Vanity of vanities,” sayeth the preacher. “All is vanity.” We have known about the science of greenhouse gases and global warming for a long time. The recent death of George H.W. Bush puts our societal self-deception into perspective. The last Republican President with the semblance of a working brain, Bush helped create the ongoing governmental research project called the National Climate Assessment. The fourth edition of this assessment was issued (as required by law) a few weeks ago by the administration of a POTUS who believes his innate self-regard is a surer guide to policy than science, fact, or the requirement of an empirical basis for proclaiming truths about nature that Western Civilization has accepted since the time of Newton. This latest Climate Assessment basically confirms that human civilization is doomed in the absence of what amounts to the political miracle of a worldwide crash program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In 1988, the year Bush senior was elected president, the New Yorker published an essay titled “The End of Nature,” spelling out the predictable effect of continued rapid greenhouse gas poisoning of the earth’s atmosphere. Thirty years ago, that is, anyone who could read was likely to draw the conclusion that rapid atmospheric warming spelled major trouble for that planetary ‘nature’ of which we are all a part and for all the natural systems on which human society depends. The corporation in that day with the tightest hammerlock on the upper reaches of the American government, Exxon, had understood the seriousness of global atmospheric warming directly caused by the human burning of fossil fuels since way back in 1977, when one of its senior scientists told Exxon’s top execs that fossil fuels were driving up average global temperatures at a rate likely to produce disastrous consequences. Further research sustained this conclusion. Five years later Exxon scientists told company leaders that “potentially catastrophic events” would require “major reductions in fossil fuel and combustion.” [https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/20...] Exxon corporate execs did what corporate execs always do. They hid the facts and spun the issue in a way to keep government away from the problem, the public in the dark, and industry profits as high as possible. Earlier this year the New York Times devoted an entire issue of its weekly magazine to a story titled “Thirty years ago, we could have saved the planet.” Detailing the many opportunities industry and government leaders had to make policy choices to reduce the pace of global warming during the decade after scientific findings showed that human society was in trouble, the report offered this summary of the consequences of inaction: “Since 1989, the global mean temperature has increased by one degree Fahrenheit. By 2030, the number of people worldwide affected by floods is expected to triple. Between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected cause the deaths of roughly 250,000 people each year. By 2050, the Arctic Ocean is expected to be largely ice-free in the summer. By that same year, a million species will face extinction… By the turn of the next century, global sea levels will have risen by to four feet, potentially turning hundreds of million of people into refugees.”[https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/08/01/magazine/climate-change-losing-earth.html] Those refugee numbers will spike even higher when croplands parched by rising temperatures can no longer feed us. In fact, world agricultural output is already on the decline.These are impacts that well-meaning individuals cannot deal with by recycling more and driving cars with better mileage, or even electric cars. This is a crisis that requires a full national and international mobilization of human effort and resources such as that required to win a world war. To plan, initiate and organize that sort of effort, a large representative democracy such as ours relies on its leaders. Individuals can neither study the full extent of a life-or-death planetary crisis nor provide a solution. That’s what governments led by elected leaders are for. Our elected leaders have failed us. They go on failing us today. Becoming President in 1989, Bush senior supported legislation creating the National Climate Assessment, a project that brings 13 different federal agencies into play. The fourth iteration of that Assessment was issued on November 23 by the administration of a POTUS who claims for political reasons not to see what the problem is. In fact, no one can be quite that stupid. What he believes is that it will be someone else’s problem long after he’s gone. Frankly, that’s what everyone appears to believe. But ask the Californians whose homes went up in smoke last month. Ask the people of Florida, or Texas, or Puerto Rico who suffered similar losses in last year’s record-setting hurricane season. Ask the citizens of the Pacific island nations who watch their country washing away. The effects are already here, and they will inevitably get worse. After a good start on climate assessment, Bush senior ran away from the clearly identified problem by failing to support a government mandated program to reduce greenhouse emissions.He’s had plenty of company ever since. No carbon tax, calculated to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and make sustainable alternatives more attractive, can achieve political traction in Washington so long as the fossil fuel industry retains its hold on government by employing its financial power to influence the public and bribe fossil-fuel friendly Congresses against it. The environmental researcher and writer Alex Steffen describes the successful industry conspiracy to block efforts to reduce carbon emission as “perhaps the most consequential deception in mankind’s history.” The consequence being, of course, the undermining of human civilization. Cornering the stock market, or dumping bad mortgages on little banks, is child’s play in comparison. Human beings survived an Ice Age that ended a mere 12,000 years ago. Perhaps a few of our species will survive the current man-made polluting of the atmosphere and consequential cataclysmic disruption of the climate to which we contemporary humans and our societies have adapted — i.e. a livable planet, which soon we will make unlivable. It’s a slender hope. Bush senior’s son, Bush junior — H.W.s biggest single mistake — played his predictable dunderhead role in leading America down the garden path to environmental hell. When world leaders woke to the looming global warming disaster and held the Koyoto Convention in 1997 — twenty years after Exxon scientists identified the problem — they reached an “accord” on limiting carbon emissions from fossil fuels. But back in these United States lobbyists went to work on our weak-kneed politicians. George W. Bush, a dilettante in every field he ever entered, surrendered his thread-bare political manhood to the evil mastermind and oil-industry stooge Dick Cheney, who cared more about oil futures than little consequences such as the future of humanity. Cheney had a word with the newly (and falsely) elected President, and Bush junior obligingly dropped his election-year 2000 promise to back laws to reduce carbon dioxide pollution. In American politics, facts that get in the way of profits are simply made to go away. Now we are in thrall to a POTUS who does not believe in facts, except those alternate realities of his own invention. Total political irresponsibility in the face of an increasingly obvious threat of catastrophic climate change continued until Obama — America’s last legitimately elected President; will we ever have another? — signed the Paris Climate Accord, committing us to do something. The agreement’s goals were not stringent enough, and most countries have already failed to meet them, but at least the Paris Accord committed us to an international effort to mitigate the worst impacts of a looming societal breakdown. Ah, but this level of responsibility proved too much for self-indulgent Americans to bear. Our failing democracy promptly enabled the fraudulent election of a dunderhead and schoolyard bully, who straightway tore up the agreement and called for more drilling, digging, and all other means of rapid environmental desecration. But global warming is not simply a ‘political’ issue and you can’t put all the blame on the current POTUS since a long string of lies, obfuscation, greed and political corruption have undermined action on this singular crisis for the future of humanity for a clearly documented 40-year history. It’s a problem that won’t go away, because facts don’t. Since we can’t go back in time and change things — the only truly satisfying intellectual solution is time-travel; a theme on which we also keep getting screen and literary narratives — the only thing we can do now is kick away the obstructions and distractions. De Trompe, whose government is all obstruction and distraction, certainly has to be yanked off stage by the hook of rational self-interest. His supporters have to be invited to resume their displaced humanity, if they can find where they left it. And Americans have to elect and support leaders willing to tell corporations and other wealthy funders what to do, rather the long-endured other way around. I’m not sure our democracy is up to this job. Anybody know a good candidate for benevolent dictator?

Our political and corporate leaders have known about the threat posed by rapid climate change for well over 30 years now. Our leaders simply behave as if denying the truth will somehow cause this reality to shrug and go away. It will not. No superhero can suck the greenhouse gases out of our atmosphere and our oceans. The aliens will not arrive to save us. The ‘rapture’ will give way to The Rupture, and our planetary lease will be permanently broken because we couldn’t be bothered to take care of the place. Face it, folks, barring some apparently super-human course correction we are living in what may prove to be the human centuries. Our descendants in subsequent centuries, if there are any, will no longer be living in the "Anthropocene," the era of human domination the planet. But in the era of human diminishment, as they struggle to survive increasingly hostile conditions. And even before the 21st century gets too much further along, our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren will likely be struggling with conditions those of us born in more fortunate (though careless) times would regard as unbearable and unimaginable. What are the countries of the world doing to mitigate the disaster? Making inadequate promises they fail to live up. What are our political and business leaders doing? Sticking their heads in the sand, on which they build their mansions of narcissistic self-absorption. “Vanity of vanities,” sayeth the preacher. “All is vanity.” We have known about the science of greenhouse gases and global warming for a long time. The recent death of George H.W. Bush puts our societal self-deception into perspective. The last Republican President with the semblance of a working brain, Bush helped create the ongoing governmental research project called the National Climate Assessment. The fourth edition of this assessment was issued (as required by law) a few weeks ago by the administration of a POTUS who believes his innate self-regard is a surer guide to policy than science, fact, or the requirement of an empirical basis for proclaiming truths about nature that Western Civilization has accepted since the time of Newton. This latest Climate Assessment basically confirms that human civilization is doomed in the absence of what amounts to the political miracle of a worldwide crash program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In 1988, the year Bush senior was elected president, the New Yorker published an essay titled “The End of Nature,” spelling out the predictable effect of continued rapid greenhouse gas poisoning of the earth’s atmosphere. Thirty years ago, that is, anyone who could read was likely to draw the conclusion that rapid atmospheric warming spelled major trouble for that planetary ‘nature’ of which we are all a part and for all the natural systems on which human society depends. The corporation in that day with the tightest hammerlock on the upper reaches of the American government, Exxon, had understood the seriousness of global atmospheric warming directly caused by the human burning of fossil fuels since way back in 1977, when one of its senior scientists told Exxon’s top execs that fossil fuels were driving up average global temperatures at a rate likely to produce disastrous consequences. Further research sustained this conclusion. Five years later Exxon scientists told company leaders that “potentially catastrophic events” would require “major reductions in fossil fuel and combustion.” [https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/20...] Exxon corporate execs did what corporate execs always do. They hid the facts and spun the issue in a way to keep government away from the problem, the public in the dark, and industry profits as high as possible. Earlier this year the New York Times devoted an entire issue of its weekly magazine to a story titled “Thirty years ago, we could have saved the planet.” Detailing the many opportunities industry and government leaders had to make policy choices to reduce the pace of global warming during the decade after scientific findings showed that human society was in trouble, the report offered this summary of the consequences of inaction: “Since 1989, the global mean temperature has increased by one degree Fahrenheit. By 2030, the number of people worldwide affected by floods is expected to triple. Between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected cause the deaths of roughly 250,000 people each year. By 2050, the Arctic Ocean is expected to be largely ice-free in the summer. By that same year, a million species will face extinction… By the turn of the next century, global sea levels will have risen by to four feet, potentially turning hundreds of million of people into refugees.”[https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/08/01/magazine/climate-change-losing-earth.html] Those refugee numbers will spike even higher when croplands parched by rising temperatures can no longer feed us. In fact, world agricultural output is already on the decline.These are impacts that well-meaning individuals cannot deal with by recycling more and driving cars with better mileage, or even electric cars. This is a crisis that requires a full national and international mobilization of human effort and resources such as that required to win a world war. To plan, initiate and organize that sort of effort, a large representative democracy such as ours relies on its leaders. Individuals can neither study the full extent of a life-or-death planetary crisis nor provide a solution. That’s what governments led by elected leaders are for. Our elected leaders have failed us. They go on failing us today. Becoming President in 1989, Bush senior supported legislation creating the National Climate Assessment, a project that brings 13 different federal agencies into play. The fourth iteration of that Assessment was issued on November 23 by the administration of a POTUS who claims for political reasons not to see what the problem is. In fact, no one can be quite that stupid. What he believes is that it will be someone else’s problem long after he’s gone. Frankly, that’s what everyone appears to believe. But ask the Californians whose homes went up in smoke last month. Ask the people of Florida, or Texas, or Puerto Rico who suffered similar losses in last year’s record-setting hurricane season. Ask the citizens of the Pacific island nations who watch their country washing away. The effects are already here, and they will inevitably get worse. After a good start on climate assessment, Bush senior ran away from the clearly identified problem by failing to support a government mandated program to reduce greenhouse emissions.He’s had plenty of company ever since. No carbon tax, calculated to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and make sustainable alternatives more attractive, can achieve political traction in Washington so long as the fossil fuel industry retains its hold on government by employing its financial power to influence the public and bribe fossil-fuel friendly Congresses against it. The environmental researcher and writer Alex Steffen describes the successful industry conspiracy to block efforts to reduce carbon emission as “perhaps the most consequential deception in mankind’s history.” The consequence being, of course, the undermining of human civilization. Cornering the stock market, or dumping bad mortgages on little banks, is child’s play in comparison. Human beings survived an Ice Age that ended a mere 12,000 years ago. Perhaps a few of our species will survive the current man-made polluting of the atmosphere and consequential cataclysmic disruption of the climate to which we contemporary humans and our societies have adapted — i.e. a livable planet, which soon we will make unlivable. It’s a slender hope. Bush senior’s son, Bush junior — H.W.s biggest single mistake — played his predictable dunderhead role in leading America down the garden path to environmental hell. When world leaders woke to the looming global warming disaster and held the Koyoto Convention in 1997 — twenty years after Exxon scientists identified the problem — they reached an “accord” on limiting carbon emissions from fossil fuels. But back in these United States lobbyists went to work on our weak-kneed politicians. George W. Bush, a dilettante in every field he ever entered, surrendered his thread-bare political manhood to the evil mastermind and oil-industry stooge Dick Cheney, who cared more about oil futures than little consequences such as the future of humanity. Cheney had a word with the newly (and falsely) elected President, and Bush junior obligingly dropped his election-year 2000 promise to back laws to reduce carbon dioxide pollution. In American politics, facts that get in the way of profits are simply made to go away. Now we are in thrall to a POTUS who does not believe in facts, except those alternate realities of his own invention. Total political irresponsibility in the face of an increasingly obvious threat of catastrophic climate change continued until Obama — America’s last legitimately elected President; will we ever have another? — signed the Paris Climate Accord, committing us to do something. The agreement’s goals were not stringent enough, and most countries have already failed to meet them, but at least the Paris Accord committed us to an international effort to mitigate the worst impacts of a looming societal breakdown. Ah, but this level of responsibility proved too much for self-indulgent Americans to bear. Our failing democracy promptly enabled the fraudulent election of a dunderhead and schoolyard bully, who straightway tore up the agreement and called for more drilling, digging, and all other means of rapid environmental desecration. But global warming is not simply a ‘political’ issue and you can’t put all the blame on the current POTUS since a long string of lies, obfuscation, greed and political corruption have undermined action on this singular crisis for the future of humanity for a clearly documented 40-year history. It’s a problem that won’t go away, because facts don’t. Since we can’t go back in time and change things — the only truly satisfying intellectual solution is time-travel; a theme on which we also keep getting screen and literary narratives — the only thing we can do now is kick away the obstructions and distractions. De Trompe, whose government is all obstruction and distraction, certainly has to be yanked off stage by the hook of rational self-interest. His supporters have to be invited to resume their displaced humanity, if they can find where they left it. And Americans have to elect and support leaders willing to tell corporations and other wealthy funders what to do, rather the long-endured other way around. I’m not sure our democracy is up to this job. Anybody know a good candidate for benevolent dictator?

Published on December 17, 2018 15:16

December 13, 2018

Poetry and Politics: Poems on 'My America' Resonated at Reading

I had a great time reading poetry to a smart and responsive audience at Plymouth Public Library last Sunday afternoon -- a compliment I can't easily repay.

I had a great time reading poetry to a smart and responsive audience at Plymouth Public Library last Sunday afternoon -- a compliment I can't easily repay. I was reading some political commentary poems from the "Wild Ideas" section of my book "Cocktails in the Wild," when after concluding a long poem titled "My America," someone began clapping and the whole room immediately joined.

Poetry readings of the serious sort are not often interrupted by applause. That was certainly the first time it happened for me.

And that's reason enough for me to reprint the poem, "My America," parts i and ii, below. The poem was written during the Presidential campaign of 2016, when it appeared to me and many others that our system of electing leaders was exposing an ugly national underbelly, but well before the vote. The poem was originally published in Verse-Virtual.com in the fall of 2016.

My thanks for opportunity to read to Plymouth Public Library director Jen Harris, outreach librarian Tom Cummiskey; to author/poet pal Judy Campbell, who brought both friends and some unbeatable chocolate fudge (the friends were good too). And to Anne, who timed the photos in the power-point down to the second.

Some folks even bought copies of my poetry books for Christmas presents. Is that the holiday spirit of giving, or what?

My America (i) ("There died a myriad... For a botched civilization" -- Ezra Pound)

Looking at you these fallen days (or me in the mirror) I join the ranks of your disappointed admirersWe are no longer saving the worldwe are saving our jobsFrankly, I am sick of the whole 'greatest country in the world' chest-thumperyand if there were somewhere else to go I would go therebut (still true) if you are not part of the solutionyou are part of the problem and I know which part I am

America, my transcendental gender-free inamorata, you are my sole supportI am one of your pensioned ex-lovers, as glimpsed in the film version of what-we-now-really-are, walking the boardwalk somewhere desolate, like Atlantic City, the New Jersey Crimea, sucking up air like one of Chekov's washed-up emigres,after the rodeo, after the gold rush, after the film festival, the short-series Conventions,after the failed uprising, after the media has packed up and gone hometo spend a quiet evening in the hotel with their phones

one of your disappointed vampires in need of a bloody fix, scanning the pre-dawn streets for Ginsberg set-piece atrocities,the best minefields of America, dodging gunned-up, hyped-up, trumped-up scaredy-cops shooting black men because we are afraid of black men(why shouldn't we be? given all we have done to them?)and are of course still doing with fanny-pats of approval from race-card Republican judges

America, ghoulish dreamboat, ancient lover gone in the teeth,eager for wounds to lick cuz you like the tasteyou grow comfortable with the deaths of othersThey are dying in AleppoOther countries (nursing their own broken mirrors) ask, "What are they are thinking in America?"They are not thinking in AmericaThinking is not done in America,some calculation of course, some texting, some advertising,some truly boorish emotingIt's always about us, isn't it?If not, then why are you bothering me?

My America! after the big affair, after the ball is over, your kick-line of sulky dwarfs cleaning up behind the paradeYou were young onceWe were all young onceYour bright young men wore wigs and tight pants, showed a legLadies learned to smoke, swear, dance and dip to apocalyp-stick swingtime America, your century is overYou open your faded arms to tinpot dictators, make eyes at banana republics, don the latest looks from funhouse mirrors,worship pigs who despise everything you ever stood for ... all for a botched democracy, a menopausal male gone grouchy in the knees, stiff in the frontal lobe You have no use for carping critics who spend time spooning with their buddy Google, the single pop culture lightweight who can stand their companyWrite me a check and I'll get out of town

My America (ii)

My America, however, is a guy with a distinctly 'different' name that is to say clearly not Anglo-Saxon (a tongue with more than enough funny names of its own), for example banjo player 'Bela Fleck'combining Hungarian roots with the Appalachian mountain music that now defines his instrument,itself a melding of deep-flowing currents, Celtic, English, African-AmericanWho travels to Africa to trace the banjo's genealogy in hide-covered stringed instruments brought here by slaves In the film* you can see the respect in his eyes as his fingers work to copy a finger-picking rhythm pecked at hummingbird speed by a Malian guitar playerand the respect in the eyes of the African players of the akonting (a three-stringed, long-necked banjo antecedent)as they see what Fleck can do with the modern version

The country, that is, of Yo-Yo Ma, Lang Lang, my Quincy Chinese neighbors whose grandfathers visit to play basketball with preschool grandsons,the lady who shouts with the half-dozen words we share that I have planted my garden in the wrong place. 'What are these?' she points. 'Nothing to eat?' The country of my wife's grandfather Meier who escaped the czar's army to carry a sewing machine to work in BrooklynMy close-mouthed father, born here in unlucky times, who never once in our hearing spoke a word of his Depression childhood, but survived to give us what he lacked and carried his secrets to the graveThe Nisei soldiers who stormed up mountains in Italy to take Nazi fortswhile their parents were interned somewhere in the ambivalently 'Great' Plains,and those with names like DiMaggio whose mothers were forced to register each year as enemy aliens and whose travel-restricted fathers could no longer visit their sons' restaurantswhile they fought in Europe and the Pacific Of citizen Khizr Khan, whose officer son died protecting those who served under him in Afghanistan,a country much like this one in having too many wars. (My America can be improved.)And Zarif Khan, who founded an Afghani community in of all places Wyoming, by taking advantage of a collection of opportunities such as the ranch-hands' pent-up demand for fresh tamales, the stock market, freedom of travel, the right to vote, a collection found perhaps nowhere else but in these United States

Of Darlene Love who went from house cleaner, to backup singer, to contributing "Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)," to the nation's permanent holiday playlist The country where an author (Barbara Ehrenreich) could write a book titled "Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America"and not be hounded by Putin's police The country of Cesar Chavez, Joan Baez, Sonia Sotomayor, Roberto Clemente, Rita Moreno

A country of 'climbing-up' ordinary heroes, open minds, thinkers and doers, money makers and music makerswith names our own Moms and Dads never heard of,but learned to play nice with for the good of the whole, e pluribus unum transcending the clans and tribalisms that set other worlds on fire

because we were the others, the strangers, the newcomers once, the genuine alien nation

*"Throw Down Your Heart," 2008

links to my two poetry books:

http://www.unsolicitedpress.com/store/p139/robertknoxpoetry.html

https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/gardeners-do-it-with-their-hands-dirty-by-robert-knox/

Published on December 13, 2018 10:59

December 1, 2018

The Garden of Verse: Poems and Photos in December's Verse-Virtual

Pierce Pond, Pleasant Valley Wildlife Sanctuary, Mass Audubon, Lenox, Massachusetts. Seven short poems with accompanying photos are up today on the December issue of Verse-Virtual.com. My thanks go to editor Firestone Feinberg for turning these poems and photos of various sizes into the album-like presentation I hoped to achieve. The photo above is one I took on a chilly late October morning when Anne and I went for a walk in the Pleasant Valley Mass Audubon nature preserve in Lenox, Massachusetts in October. See http://www.verse-virtual.com/robert-knox-2018-december.html Anne was recovering from minor knee surgery and we often looked for modest outings in beautiful places, which, happily, were not at all that hard to find. Some other folks walking there that morning offered notes on the wildlife they'd glimpsed and shared their appreciation of the place's beauty this time of the year. The other subjects for the poems with photos included in the online journal are a wetland created by beavers who dammed a stream very close to a hardtop road and a house situated on it. Over a decade and a half we watched the beaver dam transform the landscape into a habitat that protected and fed them, as grass and woodland gave way to marsh grass, pools, dying trees, and wetland habitat for birds and fish. The beavers are gone now; the transformation goes on. Other subjects are another wetland that abuts a sizeable pond called Stockbridge Bowl, on the other side of a causeway. We walk there frequently to watch a sunset or simply gaze at the water. Also: a tiny cabin in the middle of a sloping green field. A fast-running stretch of the Housatonic River seen from the new River Walk park in Great Barrington. A view of mostly bared trees from a hillside cabin. And a view of a newly created preserve off Under Mountain Road, also in Lenox. You can see these photo-poems and work by 30 poets in all in the December issue of Verse-Virtual.com http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-and-articles.html

Published on December 01, 2018 21:58

November 28, 2018

The Garden of Verse: Desert Rain, the Man in the Moon, and Dali's Melting Clocks in November's Verse-Virtual

I tend to see everything through the lens of the seasons. Every season has not only its weather, but its mood and its landscape.

I tend to see everything through the lens of the seasons. Every season has not only its weather, but its mood and its landscape. The onset of winter in the desert is viewed through the memory of the "long, dry summer" in "A Day’s Rain" by David Chorlton, a poem that gives us both a vivid depiction of both landscape and mood."There go

the devils who fanned

the sun’s flames at noon. It’s the time

of starlings and Purple sage. And raindrops

hang in the melancholy air..."

Winters have their discontents. Barbara Crooker's POEM WITH AN EMBEDDED LINE BY SUSAN COHEN alludes to these (without naming them) in a reference to the "terrible politicians" and "their terrible politics," and then makes the political personal. "At my kitchen table, all will be fed. I turn

the radio to a classical station, maybe Vivaldi.

All we have are these moments: the golden trees,

the industrious bees, the falling light. Darkness

will not overtake us." Bees and trees and beautiful twilights: that's a recipe for survival.

The seasons of a human life are with us as well, as the striking first line of Frederick Feirstein's poem "Aging" reminds us:"After a while we learn to mourn ourselves." The poem then attunes our sensibility to the mood of the seasons and of those we care for in this lovely piece of word painting: "Downstairs our precious block was being lit

For Christmas, strings of lights on all the trees,

Snow falling bit by bit by bit.

You kneeled at the window, childlike on your knees." We know the scene is indeed 'precious,' because we remember that first line.

Linda M. Fischer's poem "The Persistence of Memory" offers us a depiction of the melting landscape "from the painting by Dali." Once more I'm startled by a first line, "This is no landscape for humans" with its echo from Yeats ("no country for old men"). And the word-painting imagery that follows: "the foreground ocherous or black,

a cheerless sky, the hanging tree—

and time beginning its slow descent,

dragging me, unwilling, into that airless

vortex. I feel myself shrinking..." A strong poem to share the page (and a title) with Dali's unforgettable image. For a change of mood, Jim Lewis offers a highly literate parody of the physical examination protocol in "the man in the moon gets an ultrasound," a poem that leaves me with a moon-faced smile. We turn from landscape to moonscape in lines like these:"history of present illness:

round-faced male, brought in by cloudless skies

presenting complaint—persistent headache

admits to receiving multiple blows to the face

remote onset, exact date unknown,

most recent occurrence earlier tonight

before he walked up the eastern stellar stairway.." The entire poem is a a witty appropriation of the oh-so-professional and de-humanized jargon of an encounter we have all experienced: up close and impersonal.

On the subject of lightening the mood, both personally and politically, Steve Klepetar's "I Reach a Plea Deal with Robert Mueller" explores the landscape of satirical self-revelation. The poem is a happy confessional of sinful self-indulgences combined with allusions to our ongoing national drama:"I plead guilty for snitching peanuts in the middle of the day.

I plead guilty for watching Game of Thrones.

When I admit reading all the books, Mueller sighs

and shakes his head. What depravity he has seen in his long career!

I plead guilty for posting my poetry publications on Facebook

and counting up the likes the way a miser would let gold coins

spill across his hands." I love the image of Mueller sighing and shaking his head (that hit long-form series coming to a screening service near you). And as for the Facebook confession, I am quite sure members of this jury would vote to acquit. A splendid comic poem.

It's holiday season, too, which inevitably brings thoughts of family. "The Greatest Generation," the just-right title of this poem by Alan Walowitz, belongs (in my mind at least) to the genre I call 'what our fathers would and would not talk about.' The opening lines --"My father didn’t need to go anywhere

since he’d done the continent all-expenses-paid—

they even gave him grenade and gun." -- reminded me of my father's expressed determination never to travel overseas: He'd already been there. The men who 'went to the war' paid a price, even if they came back in one piece. This poem, based on an attempt to please a father by sparking a memory, tells a story of about the price one of that 'greatest generation' paid. And, at the end, November's issue is graced by Marilyn Taylor "At the End." Too deep for many words here , the poem evokes the funerary rituals of another age in concrete images --"and a twist of her gray hair

been dipped in oil

and set alight, releasing the essence

of her life’s elixir, pricking

the nostrils of her children

and her children’s children"...

-- and then offers a final devastating image of one of our rituals. In completely objective perspective, tone and voice, the poem speaks to us of deeply personal matters. We can't evade its impact. Read these poems and the many other fine offerings in November's Verse-Virtual at http://www.verse-virtual.com/alan-walowitz-2018-november.html

Published on November 28, 2018 10:58

November 19, 2018

The Garden of Theater: Where Did Those Witches in Macbeth Come From? 'Equivocation' Tells the Truth

The ensemble cast of the Actors' Shakespeare Project performing "Equivocation" in Boston As performed by the Actors' Shakespeare Project, the play "Equivocation" by Bill Cain is enough to make me rethink my customary reluctance to go to see 'new' plays that I know nothing about and haven't even read the reviews. It's a brilliant play. It's a play about the historical background that led Shakespeare to compose, and his company to stage, "Macbeth": the Scottish play, the play with the witches in it, the play where unbridled ambition murders a rightful king and puts an illegitimate ruler on a throne... and turns a country into, in period lingo, "Another Hell Above the Ground."

The ensemble cast of the Actors' Shakespeare Project performing "Equivocation" in Boston As performed by the Actors' Shakespeare Project, the play "Equivocation" by Bill Cain is enough to make me rethink my customary reluctance to go to see 'new' plays that I know nothing about and haven't even read the reviews. It's a brilliant play. It's a play about the historical background that led Shakespeare to compose, and his company to stage, "Macbeth": the Scottish play, the play with the witches in it, the play where unbridled ambition murders a rightful king and puts an illegitimate ruler on a throne... and turns a country into, in period lingo, "Another Hell Above the Ground." It's also a play about a word that struck fear into the English establishment in 1605 -- "equivocation." But as the production's director notes, "Though the play is set in Jacobean England in 1606, it is about now -- both in language and character." In the first years of a new century (the 1600s), and under a new ruler, Shakespeare's Company confronted challenges to its survival. Under Elizabeth's reign, the company was the "The Queen's Men" -- but, alas, the queen has died and a new monarch, James Stuart, king of Scotland, and now James I of England, sat on England's throne. Would the company still be fostered and protected by the country's monarch? The company's issues of survival and direction were brought to a boil by the infamous "Gunpowder Plot." The plot to blow up Parliament and destroy the king and his family in one devastating coup d'etat was discovered late in 1605 when an armed man was found standing guard over a room filled with barrels of gunpowder (leaving a permanent imprint on the English calendar: Guy Fawkes Day). The discovery led to the uncovering of a plot by Catholic lords to destroy the government and return the country to the "old religion." My knowledge of the Gunpowder Plot and its effect on Shakespeare, his company, and the play "Macbeth" (produced the following year) comes from James Shapiro's book, "The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606," which I read a couple of years ago. His chapters on these issues include a history of "equivocation" -- short definition: the doctrine of the religious justification for lying -- that so worried the English government that high officials claimed it threatened the fundamental basis of human society. The Gunpowder Plot goes down as the last attempt to restore Roman Catholicism as the state religion of England. A look at the history of religious warfare in England and the rest of Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries is likely to convince anyone that America's founders showed great wisdom in insisting on "no establishment of religion" in our Constitutional framework. Religious conflict caused a state of warfare between Protestant England and Spain during Queen Elizabeth's reign and the famous invasion attempt made by the Spanish Armada. Fears of Catholic plots or rebellion caused Elizabeth to have her half-sister Mary Stuart, a Catholic, executed. And Mary's son, James, succeeded Elizabeth to the throne it was only after the English government was convinced that James was a bedrock Protestant. Both Elizabeth and James hunted down Catholic priests slipped into the country by England's enemies, France and Spain, to minister to the country's religious minority. That Catholic population did not significantly decline until the Gunpowder Plot discredited the Roman Catholic religion as the fixed enemy of the English state. In fact, "Equivocation" raises the possibility that the 'plot' was a government conspiracy to achieve that very purpose, the way Hitler set fire to his country's Reichstag (parliament) to scapegoat German Communists. The background of religious conflict and a new king on the throne throw light on the key elements in Shakespeare's "Macbeth" -- a Scottish king, a plot to murder a legitimate king, the role of duplicitous witches (an obsession of King James), and the murderous Macbeth and his Lady's reliance on secrecy and lies to carry out their conspiracy. And the 'hell on earth' that follows in a country ruled by murderous 'equivocators.' After reading Shapiro's account of the contemporary conflicts that influence "Macbeth," I thought, 'ah, someone could write a really good story' about these connections, those troubled times, and Shakespeare's enduring masterpliece.' Or, as it turns out, a good play. Author Bill Cain wrote "Equivocation" about a decade ago, and the Actors Shakespeare Theater performed its production for a month in greater Boston, closing a week ago. Here's the company's plot synopsis: "It is England,1605, and a terrorist plot to assassinate the King of England, James I, and blow up Parliament with barrels of gunpowder has been foiled. Prime Minister Robert Cecil commissions William Shakespeare to write a lasting history of the failed plot. King James wants a play and he wants witches. As Shakespeare wrestles with the dilemma of being a propagandist playwright in service to the Crown, his company of fellow actors at the Globe Theatre explore the new play and find the story might just be a political cover. Do the actors speak truth to power, the King and Cecil, and risk spending their lives in prison, or worse, lose their heads?" In fact, the play not only dramatizes the 'historical' circumstances in a way that makes them feel completely 'modern' -- Robert Cecil is both a ruthless operator, conspirator and "spinner" of issues, he's a sophisticated literary critic and historical analyst; while Shakespeare and his actors weigh considerations of fame, artistic independence, 'selling out' to the propaganda needs of the state, and the need for cold cash -- it raises moral, political, and interpersonal issues at a challenging, verbally clever and fast-moving pace. What might well serve as 'major revelations' in today's all-day cable news world pop up every minute or so in Cain's brilliant script. If you think you've missed something, you probably have. But let it go, because the next intellectual shocker is just around the corner. Now here's where the doctrine of "Equivocation" comes into play. While the word initially meant an 'ambiguous' expression, Shapiro tells us ("In the Year of Lear"): "By the time that Shakespeare used the word in the spring of 1606, familiarity with it was nearly universal... No longer neutral, it was now taken to mean concealing the truth by saying one thing while deceptively thinking another." It's not just lying. It's sophisticated, doctrinally justified lying, in behalf of a cause believers argue is a highly moral purpose. It had become a newly debated religious doctrine for England's Catholic population, who faced government inquiries -- or witch-hunts -- at a time when practicing their religion was against the law, keeping banned religious articles could get you sent to prison or worse, and hiding a priest (routinely burned at the stake if discovered) would definitely get you executed. So some followers of the 'old religion' were faced with cruel choices if the belief-police arrived at their door when they were concealing or otherwise secretly helping a priest. Either tell the truth and expose your co-religionists, and quite possibly yourself to torture, prison and execution. Or imperil your soul by lying. The issues gives us an insight into the chasm between the 17th century world view and our own. All law, policing, and jurisdiction in Christian England (and elsewhere) was based on the belief that no one was likely to dare lying under oath. "On your oath," the custodian of the law demands, "were you at home last night?" Your life, let us say, would be much simpler if you could say with a straight face "I was right here with the goodwife" rather than tell the truth, that were down at the tavern participating in an unlicensed "bear-baiting" -- an admission that might you fined and the bear-baiters shut down and perhaps imprisoned. But you simply can't lie "upon your oath," because to do so imperils your soul. It's a mortal sin. You will go to hell and burn forever. (Both the Catholic and Protestant religions apparently agreed on this point.) Then a few priests began teaching the doctrine that that if you withheld certain information for a good, morally pure reason, then God would understand. The sin of bearing false witness would be washed away. Therefore according to the doctrine of equivocation you might tell the real truth to God, while you told a more convenient version of the truth to the thought-police. This act of keeping back some of the truth was also called "mental reservation." "Yes I was at home last night." Mental reservation: as soon as I got back from the bear-baiting. Or, in a more pertinent vein: "No, there is no priest within my house." Reservation: We knew you were coming and so got him out of the house and hid him somewhere else. When we're sure you guys get have left the neighborhood, we'll bring him back. But Cain's play also makes the case for equivocation. One of the most appealing characters is the priest Henry Garnet, who under questioning (and likely torture) asks the inquisitors to consider a case: a foreign country has invaded your country and seeks to replace your king with their king. Your king seeks shelter in your house. The enemy pounds on the door and demands to know whether you are sheltering the king within. Would you 'lie' to protect him? Of course not, his accusers reply. We never lie. Well, in that case, you see the problem... In Cain's fiction, Shakespeare is given an opportunity to speak with Garnet, who explains that equivocation is more than mentally reserving part of the truth. What are the enemies of the king really asking? he says. Answer the realquestion. In this case the real question is "will you help us find the king so we can take him away and kill him?" In that case, the real, and justified answer, Garnet argues, is "No." Here are a few other examples of the twists and turns from the first couple of scenes to give an idea of this play's intellectual energy. When Cecil, the King's main man, presents Shakespeare with a commission to write a "true" play about the Gunpowder Plot, the playwright objects, "We don't do "current events," adding, pointedly, "Plays about current events have always been illegal." "We do histories," he says. "True histories." The scene deepens as Cecil confesses a left-handed admiration for Shakespeare. Your plays will last, he tells him. With any luck your plays will still be on the boards for, say, "fifty years." As the scene develops the two men become increasingly more candid. Cecil:"You master Shagspeare have discovered how to be all things to all people. To do this you have made yourself a pure vessel. You have shat out of yourself any trace of personal belief." This dialogue is clearly attuned to contemporary audiences, though traces of 17th century language remain. Cecil then calls the opportunity to write about the Gunpowder Plot "your one chance at posterity." When Shagspeare (as he's called here) returns to his playhouse, we find ourselves thrown into a high-pitched rehearsal of the famous 'storm scene' from "King Lear," in which the homeless King rages in the company of his fool and the apparent lunatic Tom O'Bedlam. When the rehearsal falls apart amid quarrels, the actor playing the lunatic complains that the play calls for him to perform naked and "covered with shit." He wants a costume. Shagspeare responds, "I'm asking you to go on stage without a costume to make a living breathing flesh and blood person." A brief silence, as everyone registers this revolutionary notion. When Shag gives them the news about the commission to write a play about the ongoing political crisis, his colleagues offer the same complaints he did. They all see the danger in getting involved with the life-and-death questions of contemporary politics. Shag sums up the change this way: "Current events --with witches -- are now compulsory." The king demands witches. From here, the play works its fast-paced moral and personal dynamics until, eventually, we get to "Macbeth." Will the king like it? The play's run by the Boston-based Actors' Shakespeare Project, unfortunately, is over. If, however, you get a chance to see this play anywhere, take it. We're living in Shakespeare's posterity.

Published on November 19, 2018 15:06

The Garden of Theater: Where Did Those Witches in Macbeth Come From? 'Equivocation' Tell the Truth

The ensemble cast of the Actors' Shakespeare Theater performing "Equivocation" in Boston As performed by the Actors' Shakespeare Project, the play "Equivocation" by Bill Cain is enough to make me rethink my customary reluctance to go to see 'new' plays that I know nothing about and haven't even read the reviews. It's a brilliant play. It's a play about the historical background that led Shakespeare to compose, and his company to stage, "Macbeth": the Scottish play, the play with the witches in it, the play where unbridled ambition murders a rightful king and puts an illegitimate ruler on a throne... and turns a country into, in period lingo, "Another Hell Above the Ground."

The ensemble cast of the Actors' Shakespeare Theater performing "Equivocation" in Boston As performed by the Actors' Shakespeare Project, the play "Equivocation" by Bill Cain is enough to make me rethink my customary reluctance to go to see 'new' plays that I know nothing about and haven't even read the reviews. It's a brilliant play. It's a play about the historical background that led Shakespeare to compose, and his company to stage, "Macbeth": the Scottish play, the play with the witches in it, the play where unbridled ambition murders a rightful king and puts an illegitimate ruler on a throne... and turns a country into, in period lingo, "Another Hell Above the Ground." It's also a play about a word that struck fear into the English establishment in 1605 -- "equivocation." But as the production's director notes, "Though the play is set in Jacobean England in 1606, it is about now -- both in language and character." In the first years of a new century (the 1600s), and under a new ruler, Shakespeare's Company confronted challenges to its survival. Under Elizabeth's reign, the company was the "The Queen's Men" -- but, alas, the queen has died and a new monarch, James Stuart, king of Scotland, and now James I of England, sat on England's throne. Would the company still be fostered and protected by the country's monarch? The company's issues of survival and direction were brought to a boil by the infamous "Gunpowder Plot." The plot to blow up Parliament and destroy the king and his family in one devastating coup d'etat was discovered late in 1605 when an armed man was found standing guard over a room filled with barrels of gunpowder (leaving a permanent imprint on the English calendar: Guy Fawkes Day). The discovery led to the uncovering of a plot by Catholic lords to destroy the government and return the country to the "old religion." My knowledge of the Gunpowder Plot and its effect on Shakespeare, his company, and the play "Macbeth" (produced the following year) comes from James Shapiro's book, "The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606," which I read a couple of years ago. His chapters on these issues include a history of "equivocation" -- short definition: the doctrine of the religious justification for lying -- that so worried the English government that high officials claimed it threatened the fundamental basis of human society. The Gunpowder Plot goes down as the last attempt to restore Roman Catholicism as the state religion of England. A look at the history of religious warfare in England and the rest of Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries is likely to convince anyone that America's founders showed great wisdom in insisting on "no establishment of religion" in our Constitutional framework. Religious conflict caused a state of warfare between Protestant England and Spain during Queen Elizabeth's reign and the famous invasion attempt made by the Spanish Armada. Fears of Catholic plots or rebellion caused Elizabeth to have her half-sister Mary Stuart, a Catholic, executed. And Mary's son, James, succeeded Elizabeth to the throne it was only after the English government was convinced that James was a bedrock Protestant. Both Elizabeth and James hunted down Catholic priests slipped into the country by England's enemies, France and Spain, to minister to the country's religious minority. That Catholic population did not significantly decline until the Gunpowder Plot discredited the Roman Catholic religion as the fixed enemy of the English state. In fact, "Equivocation" raises the possibility that the 'plot' was a government conspiracy to achieve that very purpose, the way Hitler set fire to his country's Reichstag (parliament) to scapegoat German Communists. The background of religious conflict and a new king on the throne throw light on the key elements in Shakespeare's "Macbeth" -- a Scottish king, a plot to murder a legitimate king, the role of duplicitous witches (an obsession of King James), and the murderous Macbeth and his Lady's reliance on secrecy and lies to carry out their conspiracy. And the 'hell on earth' that follows in a country ruled by murderous 'equivocators.' After reading Shapiro's account of the contemporary conflicts that influence "Macbeth," I thought, 'ah, someone could write a really good story' about these connections, those troubled times, and Shakespeare's enduring masterpliece.' Or, as it turns out, a good play. Author Bill Cain wrote "Equivocation" about a decade ago, and the Actors Shakespeare Theater performed its production for a month in greater Boston, closing a week ago. Here's the company's plot synopsis: "It is England,1605, and a terrorist plot to assassinate the King of England, James I, and blow up Parliament with barrels of gunpowder has been foiled. Prime Minister Robert Cecil commissions William Shakespeare to write a lasting history of the failed plot. King James wants a play and he wants witches. As Shakespeare wrestles with the dilemma of being a propagandist playwright in service to the Crown, his company of fellow actors at the Globe Theatre explore the new play and find the story might just be a political cover. Do the actors speak truth to power, the King and Cecil, and risk spending their lives in prison, or worse, lose their heads?" In fact, the play not only dramatizes the 'historical' circumstances in a way that makes them feel completely 'modern' -- Robert Cecil is both a ruthless operator, conspirator and "spinner" of issues, he's a sophisticated literary critic and historical analyst; while Shakespeare and his actors weigh considerations of fame, artistic independence, 'selling out' to the propaganda needs of the state, and the need for cold cash -- it raises moral, political, and interpersonal issues at a challenging, verbally clever and fast-moving pace. What might well serve as 'major revelations' in today's all-day cable news world pop up every minute or so in Cain's brilliant script. If you think you've missed something, you probably have. But let it go, because the next intellectual shocker is just around the corner. Now here's where the doctrine of "Equivocation" comes into play. While the word initially meant an 'ambiguous' expression, Shapiro tells us ("In the Year of Lear"): "By the time that Shakespeare used the word in the spring of 1606, familiarity with it was nearly universal... No longer neutral, it was now taken to mean concealing the truth by saying one thing while deceptively thinking another." It's not just lying. It's sophisticated, doctrinally justified lying, in behalf of a cause believers argue is a highly moral purpose. It had become a newly debated religious doctrine for England's Catholic population, who faced government inquiries -- or witch-hunts -- at a time when practicing their religion was against the law, keeping banned religious articles could get you sent to prison or worse, and hiding a priest (routinely burned at the stake if discovered) would definitely get you executed. So some followers of the 'old religion' were faced with cruel choices if the belief-police arrived at their door when they were concealing or otherwise secretly helping a priest. Either tell the truth and expose your co-religionists, and quite possibly yourself to torture, prison and execution. Or imperil your soul by lying. The issues gives us an insight into the chasm between the 17th century world view and our own. All law, policing, and jurisdiction in Christian England (and elsewhere) was based on the belief that no one was likely to dare lying under oath. "On your oath," the custodian of the law demands, "were you at home last night?" Your life, let us say, would be much simpler if you could say with a straight face "I was right here with the goodwife" rather than tell the truth, that were down at the tavern participating in an unlicensed "bear-baiting" -- an admission that might you fined and the bear-baiters shut down and perhaps imprisoned. But you simply can't lie "upon your oath," because to do so imperils your soul. It's a mortal sin. You will go to hell and burn forever. (Both the Catholic and Protestant religions apparently agreed on this point.) Then a few priests began teaching the doctrine that that if you withheld certain information for a good, morally pure reason, then God would understand. The sin of bearing false witness would be washed away. Therefore according to the doctrine of equivocation you might tell the real truth to God, while you told a more convenient version of the truth to the thought-police. This act of keeping back some of the truth was also called "mental reservation." "Yes I was at home last night." Mental reservation: as soon as I got back from the bear-baiting. Or, in a more pertinent vein: "No, there is no priest within my house." Reservation: We knew you were coming and so got him out of the house and hid him somewhere else. When we're sure you guys get have left the neighborhood, we'll bring him back. But Cain's play also makes the case for equivocation. One of the most appealing characters is the priest Henry Garnet, who under questioning (and likely torture) asks the inquisitors to consider a case: a foreign country has invaded your country and seeks to replace your king with their king. Your king seeks shelter in your house. The enemy pounds on the door and demands to know whether you are sheltering the king within. Would you 'lie' to protect him? Of course not, his accusers reply. We never lie. Well, in that case, you see the problem... In Cain's fiction, Shakespeare is given an opportunity to speak with Garnet, who explains that equivocation is more than mentally reserving part of the truth. What are the enemies of the king really asking? he says. Answer the realquestion. In this case the real question is "will you help us find the king so we can take him away and kill him?" In that case, the real, and justified answer, Garnet argues, is "No." Here are a few other examples of the twists and turns from the first couple of scenes to give an idea of this play's intellectual energy. When Cecil, the King's main man, presents Shakespeare with a commission to write a "true" play about the Gunpowder Plot, the playwright objects, "We don't do "current events," adding, pointedly, "Plays about current events have always been illegal." "We do histories," he says. "True histories." The scene deepens as Cecil confesses a left-handed admiration for Shakespeare. Your plays will last, he tells him. With any luck your plays will still be on the boards for, say, "fifty years." As the scene develops the two men become increasingly more candid. Cecil:"You master Shagspeare have discovered how to be all things to all people. To do this you have made yourself a pure vessel. You have shat out of yourself any trace of personal belief." This dialogue is clearly attuned to contemporary audiences, though traces of 17th century language remain. Cecil then calls the opportunity to write about the Gunpowder Plot "your one chance at posterity." When Shagspeare (as he's called here) returns to his playhouse, we find ourselves thrown into a high-pitched rehearsal of the famous 'storm scene' from "King Lear," in which the homeless King rages in the company of his fool and the apparent lunatic Tom O'Bedlam. When the rehearsal falls apart amid quarrels, the actor playing the lunatic complains that the play calls for him to perform naked and "covered with shit." He wants a costume. Shagspeare responds, "I'm asking you to go on stage without a costume to make a living breathing flesh and blood person." A brief silence, as everyone registers this revolutionary notion. When Shag gives them the news about the commission to write a play about the ongoing political crisis, his colleagues offer the same complaints he did. They all see the danger in getting involved with the life-and-death questions of contemporary politics. Shag sums up the change this way: "Current events --with witches -- are now compulsory."

The king demands witches. From here, the play works its fast-paced moral and personal dynamics until, eventually, we get to "Macbeth." Will the king like it? The play's run by the Boston-based Actors' Shakespeare Project, unfortunately, is over. If, however, you get a chance to see this play anywhere, take it. We're living in Shakespeare's posterity.

Published on November 19, 2018 15:06

November 12, 2018

The Garden of Verse: I'll Be Reading From My Two Poetry Books in Plymouth Next Month

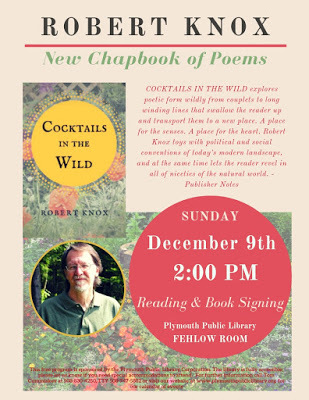

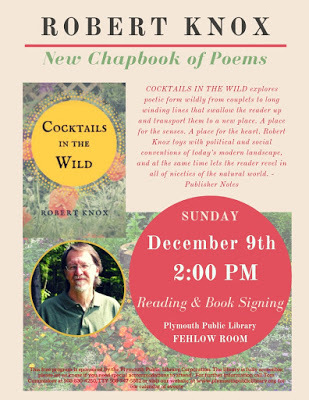

You're invited to a free poetry program at the Plymouth Public Library on Sunday, Dec. 9, at 2 p.m.

You're invited to a free poetry program at the Plymouth Public Library on Sunday, Dec. 9, at 2 p.m. I'll be reading from the poems in my collection, "Cocktails in the Wild," published earlier this year, and also from my previous collection, "Gardeners Do It With Their Hands Dirty," which has recently been nominated for a Massachusetts Book Award. Refreshments will be offered and I'll do a book-signing after the reading. As we say in the newspaper trade, "Mark your calendar." Here's what the publisher, Unsolicited Press, said about "Cocktails": COCKTAILS IN THE WILD explores form wildly from couplets to long winding lines that swallow the reader up and transport them to a new place. A place for the senses. A place for the heart. Robert Knox toys with political and social conventions of today's modern landscape, and at the same time lets the reader revel in all of niceties of the natural world. See http://www.unsolicitedpress.com/store/p139/robertknoxpoetry.html Here's my description of the book's contents: The poems take us from a balcony in Beirut, a place of beauty, history and danger, to the grim seasons of the American 2016 presidential campaign. We place a phone call to India, view a squawking peaceable kingdom in Florida (mind the alligators lurking below), raise a glass in homage to Keats and Philip Larkin, and remember that the way things were is not a recipe for tomorrow, but a gateway to today. Let's walk through it to the wildness in ourselves.

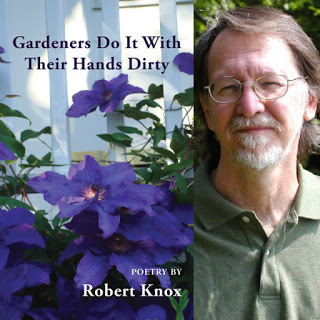

My previous book "Gardeners Do It With Their Hands Dirty," published last year by Finishing Line Press, includes poems drawn from the experience of planting a perennial flower garden in a backyard in Quincy, Mass. Here's an excerpt to the statement I wrote for the book's publisher: "Gardeners Do It With Their Hands Dirty" includes poems about plants, flowers, the craft of cultivation, talking to trees, getting stared at by hummingbirds. Seasons change and so do we. The second half of the collection encompasses poems about family and places near and far, including my father's near-fatal journey in World War II ("My Dad's Ship But One of Three"), "The Sacred Way" at Delphi in Greece, Syrian refugees in Beirut ("Sidewalk Madonnas"), and a quick dip into formal verse with "The Slow Tritina." See https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/gardeners-do-it-with-their-hands-dirty-by-robert-knox/

The book was nominated for The Massachusetts Book Awards, a program of awards made annually to books by Massachusetts residents published in the previous year. “The Massachusetts Book Awards," the program states on its website, "highlight the work of our vital contemporary writing community and encourage readers to do some 'close reading' of those imaginative works created by the authors among us." Plymouth Public Library is located at 132 South St. Again, the date is Sunday, Dec. 9, at 2 p.m. It's free. See you there.

Published on November 12, 2018 08:19

November 7, 2018

Garden of the Seasons: Marshes, Ponds, and Memories

The Beaver Marsh (top photo) The beavers have chewed the landscape into marsh Cattails along the edge, marsh grass within The masts of dead trees shrink into primeval oozeBirds nest in the margins hunt in the shallows This landscape, this point of view we would never have,all things considered,except the beaver ran through it.