Robert Knox's Blog, page 13

May 13, 2019

The Garden of the Seasons: The Perfect Day

On the second Saturday of May, we had what anyone would call a perfect dayIt fell between a month of rain and craggy skies It fell to show the truth to liesIt happened on a clear, cool, crisp and vernal dayspring-like because -- if any day we like in spring --on Saturday we had the thing itself.

On the second Saturday of May, we had what anyone would call a perfect dayIt fell between a month of rain and craggy skies It fell to show the truth to liesIt happened on a clear, cool, crisp and vernal dayspring-like because -- if any day we like in spring --on Saturday we had the thing itself.

It happened in a time of record breaking rain,Enough, almost, to go insane. And when we had that special one to blow the rain awayWhat happened next was Mother's DayAs almost every one of us recalls: A paradigm of weather that universally appalls.

Ah, but to go back to the recollection of that perfect Saturday (especially as Monday kind of stinks as well) here's the unrhymed poem I wrote after encountering my neighbor about a half block away from where our houses abut -- he was walking his dog, I was merely walking myself -- who said to me simply, "So this is perfect." Here's the poem, in praise of a perfect day.

Selling Points

It's just perfect todayThis place, season, day Folks outdoors waving their hands and jumping up and downspraying another layer of 'just beautiful' on everything Every few minutes something new: Dawn Encounter! Morning Magic! High on Life at Noon!Evening Splendor, coming to you in both sun and shade

The birds entertain, imitating themselves, spying on their competitors Each little house in a postwar burg parked up against its neighborperforms its own vernal rendition of the golden hour shineon the fruit tree blossomsHeavy on those closely packed ranks of low phlox, in alternating shades of violetAn ancient border, from some other Era of House-holding relaxing into lilac lust,or, just now, in the door-shade blooms

Modest houses, unfashionable in their want of many spacious open-plan rooms,push up to the quiet street Our own simple squeeze-box of empty-nester clutterNo need for carpet lawns of alien grasses, low on staying power, high on chemical appetitesInstead, perhaps, a single tree blossoming with the coin of the vernal realm,its simple symmetry cupping the sky,instills its nature on an entire front its fat-lady diva hour, clasping deep double-handfuls of ornamental cherry

Other, nearly tree-less blocks compete to border the worldwith open-hearted handiworkChinese gardeners finding narrow strips of dirt wide enough to grow bok choy or leafy style, both prosperous descendants of the humble turnip,where others see mere muddy footprintsor something to pave Melons in later weeks rising like torpedoes on handwoven frames

No shadows in this sun fest No traffic jams, or barking doors,or thoughtless teens, or angry bikers Wrinkled hands untangling a hose A sky finding a quiet place for a gossamer moonmocking bird warming upConcert at seven

Earth gave us a continent an ocean of green, a rainbow of cunning, experimental hues to dazzle butterfliesAnd so many gentle hands to trim the ribbons, tie the bows.

Published on May 13, 2019 21:19

May 2, 2019

The Garden of Verse: The Stirrings of Spring in the Age-Old Human Heart

I was so moved by a couple of the poems I read in the previous issue of Verse-Virtual.com that I found myself attempting to write in the same key. Was this a good idea? Second thoughts aside, I simply did it.

I was so moved by a couple of the poems I read in the previous issue of Verse-Virtual.com that I found myself attempting to write in the same key. Was this a good idea? Second thoughts aside, I simply did it. The result was the poem "At the Ivy Gate," which attempts to communicate the sense that nature's annual revival, rebirth -- all that marvelous starting over again -- triggers some deep, universal tristesse in the soul. Even as we open our hearts to all that new growth and beauty, all those new beginnings opening up around us, we know that our own beginnings, and renewals, are a limited set. We all come with a shelf-life.

We all know that one day a spring will come without us (or someone we love) to greet it. To paraphrase that most memorable line from T.S. Eliot, spring may be the "cruelest" season, in addition to the sweetest.

The phrase I borrowed from my colleague and friend Robert Wexelblatt's "The Last Poem of Chen Hsi-wei" is an old poet's characterization of his early poems as 'wind-borne chaff.' I used that image to begin my own poem, below.

At the Ivy Gate*

Such wind-borne chaff I write today,

the gate blowing listlessly in the wind

Ah, love! -- ah, spring --

Once more you rouse me from this calm

passage, a sail boat drifting on the open sea

to the final port

on the gray misty ocean where

the fantasy heroes await us with sad smiles

Ah, spring! -- ah, time

Always we think we are riding you, fine beast

of animal flesh between our thighs

But you are riding us

to that final stable

where we lay in the bed of old straw,

on our side, breathing to the gait of the final beats --

Oh, song of my heart...

a petitioner for some heavenly hail-ride service,

I wave and stand on tiptoes

at the end of the avenue

while the parade goes by

*Title borrowed from a song by Brian Cain; heard at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wSVyWIzoHPA

You can find this poem and others in the May issue of Verse-Virtual at https://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-and-articles.html

Published on May 02, 2019 22:01

April 30, 2019

Mueller's Report Laid Out a Road Map to Impeachment, But Only Congress Can Drive That Road..

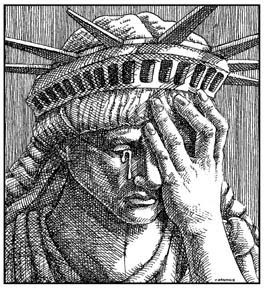

It's smack-in-the-face obvious that the current Pretender to the Oval Office attempted to obstruct justice. The Mueller report makes that point again and again. Acts of obstruction by the Pretender to the Oval Office -- I'm heavily tempted here to use the convenient and telling abbreviation POO -- include hindering a criminal investigation by pressuring others to lie to investigators or conceal facts, and by seeking to have the investigators removed from the job. All of these actions fall squarely under the category of criminal behavior called "criminal obstruction of justice." What's not so obvious to almost every one of us who is not a criminal prosecutor or a Constitutional authority is why special investigator Robert Mueller did not charge the Pretender with a crime. Mueller's report gives the answer to that question as well, but he states it in lawyerly language. For us non-lawyers, it's fortunate that some commentators familiar with the lingo have provided the translation for us. Here's the bottom line: Mueller did not charge the Pretender with committing crimes or seek to indict him because the current federal government policy (authored by the Department of Justice) is that you can't indict a sitting President for a crime -- under any circumstances. You can't charge him with X number of violations of such and such a felonious crimes and bring him to court, as you can to literally anybody else in the country. According to the Department of Justice, it's not permitted under our Constitutional system to charge a sitting President with a crime, for what many people believe are sensible reasons. We'll get to these later. First, here's a quick consensus summary of what Mueller report analysts had to say on the subject of obstruction. According to Michael A. Cohen, a veteran political columnist for the Boston Globe: "...Mueller has laid out clear and unambiguous evidence that the president attempted, on repeated occasions, to interfere with the Russia investigation and obstruct justice." Most of us who follow national news, especially in the days after the redacted report was made public, are familiar with these "repeated occasions" on which the Pretender pressured subordinates to lie for him, or to fire Mueller as his investigation probed the Trump campaign-Russian connection during the 2016 Presidential campaign The instances include Trump's repeated attempts to have one of his appointees fire Mueller -- attempts that were deflected, the report states, by the President's legal counsel Don McGahn. Trump tired to get other government officials including his staff members to stall or put roadblocks in the way of Mueller's investigators, even urging them to leak "fake news" that would play down his acts of obstruction. He tried to persuade former FBI head James Comey to drop his investigation into guilty campaign operative Mike Flynn. He tried to pressure then Attorney General Sessions to "un-recuse" himself in order to fire Mueller. Some of the other lies and acts of obstruction Trump engaged in (detailed in Mueller's report) include lying about the dirty-tricks Trump Tower meeting in order to conceal the fact that it was about getting dirt about the Clinton campaign. Also lying about the reason he fired Comey, including the whopper that he was ditching Comey because his reversals on the email issue during the campaign were widely regarded as unfair to Hillary! As if the Pretender would ever waste crocodile tears over that. Further (according to Mueller) Trump pressured a national security adviser to lie to the Washington Post about the contact between the felonious Flynn and the Russian ambassador. His director of national intelligence did lie to the Mueller investigation and to Congress about what Trump asked him to do. And serial liar Sarah Sanders wins her place in the Roll of Infamy by telling the whopper that FBI agents offered Rump a "way to go" backslap for firing their boss. Commentators in national newspapers such as The Washington and The New York Times pointed out that the Pretender's attempts to obstruct the investigation failed only because various aides, notably McGahn, refused to go along since they did not wish to be guilty of breaking the law themselves. So, the question remains, if these many attempts to obstruct a criminal investigation into possible violations of election law and other crimes are so clearly documented in the Mueller report, why didn't Muller charge the President of the United States with committing crimes? Here's the Mueller report's own answer. The report's authors state they chose “not to make a traditional prosecutorial judgment” -- that is, seek a criminal indictment -- "because of the Department of Justice regulations forbidding an indictment or criminal prosecution of a sitting president." Trumpets for Trump! Enter the Watergate connection. (What fine company our current administration is keeping.) Forty-plus years ago Watergate commission investigators asked the same sort of question that Mueller's team was forced to consider. If you have evidence that a President has broken a law, what do you do? The conclusion drawn then was that too many strains would be placed on a Constitutional system based on "The Separation of Branches and Powers" if a President's enemies were permitted to charge him with a crime and haul him into court. In Nixon's era the Department of Justice termed that possibility "unthinkable." How can a President do his job -- a big job in a dangerous world -- they asked, if he was sitting in a dock in Alabama or a Alaska and trying to defend himself against a charge such as lying to Congress about whether -- just to imagine a wildly improbable scenario -- he ever "had sex with that woman"? More seriously, the Department of Justice considered, imagine that the Russians were getting up to something -- back then, the White House considered them dangerous enemies. Would you want the President trying to deal with war or peace decisions with a criminal trial going on? The result is that ever since Watergate, the Department of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel has maintained a policy on its books that "a sitting President" cannot be asked to face a criminal charge. The question of the sitting President's immunity is not intended to place him "above the law," the experts say, but to protect our system of government from politically motivated charges of wrongdoing that would hinder him in exercising powers that the Constitution has given solely to him -- such as acting as Commander in Chief. The policy says nothing about whether the person serving as President could be made to face those charges once he steps down from office. The central point -- the sitting President's immunity from criminal prosecution -- can still be argued. Some legal minds contend there are other ways to shield him from partisan manipulation of the court system without giving him a complete pass, and legal scholars have debated it since Watergate. But for the moment, the Mueller report concluded, correctly in accord with federal law and precedent, that charging the President -- as a prosecutor would ordinarily charge anyyone else -- was simply not something within its power to do. It's unclear to me how widely the general public has grasped that point. But it's hard to see how anyone would fail to see that the claim that the report "exonerated" Trump from committing the crime of obstruction -- as the current scoundrel in the attorney general's office has wrongly claimed -- is simply a bold-faced lie. What the Mueller report does say is this: “If we had confidence after a thorough investigation of the facts that the President did not commit obstruction of justice, we would so state.” But the report did not so state. You have to be blind -- or a paid liar like the Pretender's fake attorney general -- to miss that. Michael Cohen, in his Globe piece, sums up the report's conclusion this way: "Mueller seems to be taking the view that (a) it’s not his place to pass judgment on whether the president engaged in criminal wrongdoing, (b) it’s up to Congress to make that determination, and (c) the evidence his team assembled suggests that the president did in fact obstruct justice." Many commentators have since described the evidence assembled by the Mueller Commission as "a road map" for Congress to begin the impeachment process... if that's what Congress chooses to do. The bottom line is this. In order to protect the President from specious, partisan-driven criminal charges -- that could quite possibly keep him from performing his Constitutional duties and therefore screw up the correct functioning of our political system -- (leaving aside, for the moment, the very real question of whether our political system is not already wholly screwed up and seriously dysfunctional for other, very serious reasons ) -- the only court in the land that can hold a President responsible for criminal misbehavior is the United States Congress. That's what Impeachment is. Impeachment is not the same thing as Conviction. The best synonym for "impeachment" is the common enough word "trial." Congress put Nixon on trial, for very good reasons. In the '90s Congress put Bill Clinton on trial for very stupid reasons in a blatantly partisan attempt to weaken his political party. Although a conviction was not won, that gambit may have paid off at the polls when a weak Republican candidate (W), who knew little about the functioning of the federal government and paid his job as little attention as possible, subsequently defeated a much more experienced and prepared Democratic candidate, who was perhaps less successful in his imitation of a frat boy (Gore). Back in the 70s, Congress would have convicted Nixon, but that particular 'crook' resigned first. Back in the years after the Civil War, Congress impeached Andrew Johnson in an earlier partisan quarrel, but failed to convict him by a single vote. Congress failed to convict Clinton (as mentioned), but the attempt to manipulate the system arguably weakened the functioning of our system of government. It turns out that our 'political system' is based not only on what is stated in the Constitution, and its interpretation to meet present needs, but on high standards of ethical conduct by those who are elected, or appointed, to office. Federal officials swear to put the interests of the country before their personal and party interests. But, increasingly, they don't. This is obvious to all. And the more frequently, habitually, office holders lie, cheat, and sell their votes to the super-rich corporations, the more likely they make it that our government will be led by fatuous baboons such as the present fake-President. Somebody has to say that the country comes first. That the public interest comes first. That the welfare of Americans is more important than the career, wealth or egos of its so-called "public servants." And somebody has to stand up for the integrity of the American system of government. When it comes to criminal wrongdoing by the President of the Unites States, even a faker like the current fool on the hill, the only body that can do that job is Congress. Congress has to impeach -- even if a conviction may not be won -- to show that some branch of government is still trying to make the system work.

It's smack-in-the-face obvious that the current Pretender to the Oval Office attempted to obstruct justice. The Mueller report makes that point again and again. Acts of obstruction by the Pretender to the Oval Office -- I'm heavily tempted here to use the convenient and telling abbreviation POO -- include hindering a criminal investigation by pressuring others to lie to investigators or conceal facts, and by seeking to have the investigators removed from the job. All of these actions fall squarely under the category of criminal behavior called "criminal obstruction of justice." What's not so obvious to almost every one of us who is not a criminal prosecutor or a Constitutional authority is why special investigator Robert Mueller did not charge the Pretender with a crime. Mueller's report gives the answer to that question as well, but he states it in lawyerly language. For us non-lawyers, it's fortunate that some commentators familiar with the lingo have provided the translation for us. Here's the bottom line: Mueller did not charge the Pretender with committing crimes or seek to indict him because the current federal government policy (authored by the Department of Justice) is that you can't indict a sitting President for a crime -- under any circumstances. You can't charge him with X number of violations of such and such a felonious crimes and bring him to court, as you can to literally anybody else in the country. According to the Department of Justice, it's not permitted under our Constitutional system to charge a sitting President with a crime, for what many people believe are sensible reasons. We'll get to these later. First, here's a quick consensus summary of what Mueller report analysts had to say on the subject of obstruction. According to Michael A. Cohen, a veteran political columnist for the Boston Globe: "...Mueller has laid out clear and unambiguous evidence that the president attempted, on repeated occasions, to interfere with the Russia investigation and obstruct justice." Most of us who follow national news, especially in the days after the redacted report was made public, are familiar with these "repeated occasions" on which the Pretender pressured subordinates to lie for him, or to fire Mueller as his investigation probed the Trump campaign-Russian connection during the 2016 Presidential campaign The instances include Trump's repeated attempts to have one of his appointees fire Mueller -- attempts that were deflected, the report states, by the President's legal counsel Don McGahn. Trump tired to get other government officials including his staff members to stall or put roadblocks in the way of Mueller's investigators, even urging them to leak "fake news" that would play down his acts of obstruction. He tried to persuade former FBI head James Comey to drop his investigation into guilty campaign operative Mike Flynn. He tried to pressure then Attorney General Sessions to "un-recuse" himself in order to fire Mueller. Some of the other lies and acts of obstruction Trump engaged in (detailed in Mueller's report) include lying about the dirty-tricks Trump Tower meeting in order to conceal the fact that it was about getting dirt about the Clinton campaign. Also lying about the reason he fired Comey, including the whopper that he was ditching Comey because his reversals on the email issue during the campaign were widely regarded as unfair to Hillary! As if the Pretender would ever waste crocodile tears over that. Further (according to Mueller) Trump pressured a national security adviser to lie to the Washington Post about the contact between the felonious Flynn and the Russian ambassador. His director of national intelligence did lie to the Mueller investigation and to Congress about what Trump asked him to do. And serial liar Sarah Sanders wins her place in the Roll of Infamy by telling the whopper that FBI agents offered Rump a "way to go" backslap for firing their boss. Commentators in national newspapers such as The Washington and The New York Times pointed out that the Pretender's attempts to obstruct the investigation failed only because various aides, notably McGahn, refused to go along since they did not wish to be guilty of breaking the law themselves. So, the question remains, if these many attempts to obstruct a criminal investigation into possible violations of election law and other crimes are so clearly documented in the Mueller report, why didn't Muller charge the President of the United States with committing crimes? Here's the Mueller report's own answer. The report's authors state they chose “not to make a traditional prosecutorial judgment” -- that is, seek a criminal indictment -- "because of the Department of Justice regulations forbidding an indictment or criminal prosecution of a sitting president." Trumpets for Trump! Enter the Watergate connection. (What fine company our current administration is keeping.) Forty-plus years ago Watergate commission investigators asked the same sort of question that Mueller's team was forced to consider. If you have evidence that a President has broken a law, what do you do? The conclusion drawn then was that too many strains would be placed on a Constitutional system based on "The Separation of Branches and Powers" if a President's enemies were permitted to charge him with a crime and haul him into court. In Nixon's era the Department of Justice termed that possibility "unthinkable." How can a President do his job -- a big job in a dangerous world -- they asked, if he was sitting in a dock in Alabama or a Alaska and trying to defend himself against a charge such as lying to Congress about whether -- just to imagine a wildly improbable scenario -- he ever "had sex with that woman"? More seriously, the Department of Justice considered, imagine that the Russians were getting up to something -- back then, the White House considered them dangerous enemies. Would you want the President trying to deal with war or peace decisions with a criminal trial going on? The result is that ever since Watergate, the Department of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel has maintained a policy on its books that "a sitting President" cannot be asked to face a criminal charge. The question of the sitting President's immunity is not intended to place him "above the law," the experts say, but to protect our system of government from politically motivated charges of wrongdoing that would hinder him in exercising powers that the Constitution has given solely to him -- such as acting as Commander in Chief. The policy says nothing about whether the person serving as President could be made to face those charges once he steps down from office. The central point -- the sitting President's immunity from criminal prosecution -- can still be argued. Some legal minds contend there are other ways to shield him from partisan manipulation of the court system without giving him a complete pass, and legal scholars have debated it since Watergate. But for the moment, the Mueller report concluded, correctly in accord with federal law and precedent, that charging the President -- as a prosecutor would ordinarily charge anyyone else -- was simply not something within its power to do. It's unclear to me how widely the general public has grasped that point. But it's hard to see how anyone would fail to see that the claim that the report "exonerated" Trump from committing the crime of obstruction -- as the current scoundrel in the attorney general's office has wrongly claimed -- is simply a bold-faced lie. What the Mueller report does say is this: “If we had confidence after a thorough investigation of the facts that the President did not commit obstruction of justice, we would so state.” But the report did not so state. You have to be blind -- or a paid liar like the Pretender's fake attorney general -- to miss that. Michael Cohen, in his Globe piece, sums up the report's conclusion this way: "Mueller seems to be taking the view that (a) it’s not his place to pass judgment on whether the president engaged in criminal wrongdoing, (b) it’s up to Congress to make that determination, and (c) the evidence his team assembled suggests that the president did in fact obstruct justice." Many commentators have since described the evidence assembled by the Mueller Commission as "a road map" for Congress to begin the impeachment process... if that's what Congress chooses to do. The bottom line is this. In order to protect the President from specious, partisan-driven criminal charges -- that could quite possibly keep him from performing his Constitutional duties and therefore screw up the correct functioning of our political system -- (leaving aside, for the moment, the very real question of whether our political system is not already wholly screwed up and seriously dysfunctional for other, very serious reasons ) -- the only court in the land that can hold a President responsible for criminal misbehavior is the United States Congress. That's what Impeachment is. Impeachment is not the same thing as Conviction. The best synonym for "impeachment" is the common enough word "trial." Congress put Nixon on trial, for very good reasons. In the '90s Congress put Bill Clinton on trial for very stupid reasons in a blatantly partisan attempt to weaken his political party. Although a conviction was not won, that gambit may have paid off at the polls when a weak Republican candidate (W), who knew little about the functioning of the federal government and paid his job as little attention as possible, subsequently defeated a much more experienced and prepared Democratic candidate, who was perhaps less successful in his imitation of a frat boy (Gore). Back in the 70s, Congress would have convicted Nixon, but that particular 'crook' resigned first. Back in the years after the Civil War, Congress impeached Andrew Johnson in an earlier partisan quarrel, but failed to convict him by a single vote. Congress failed to convict Clinton (as mentioned), but the attempt to manipulate the system arguably weakened the functioning of our system of government. It turns out that our 'political system' is based not only on what is stated in the Constitution, and its interpretation to meet present needs, but on high standards of ethical conduct by those who are elected, or appointed, to office. Federal officials swear to put the interests of the country before their personal and party interests. But, increasingly, they don't. This is obvious to all. And the more frequently, habitually, office holders lie, cheat, and sell their votes to the super-rich corporations, the more likely they make it that our government will be led by fatuous baboons such as the present fake-President. Somebody has to say that the country comes first. That the public interest comes first. That the welfare of Americans is more important than the career, wealth or egos of its so-called "public servants." And somebody has to stand up for the integrity of the American system of government. When it comes to criminal wrongdoing by the President of the Unites States, even a faker like the current fool on the hill, the only body that can do that job is Congress. Congress has to impeach -- even if a conviction may not be won -- to show that some branch of government is still trying to make the system work.

Published on April 30, 2019 20:06

April 27, 2019

The Garden of Verse: Ancient China, Faraway Places, Skinned Knees and Personal Bests in April's Verse-Virtual

So many excellent poems in the April issue of Verse-Virtual. April may be National Poetry Month, but each page of the calendar makes for a very good month of poetry for Verse-Virtual. The optional theme for poets in April was, again, 'your best poem,' a choice that enabled poets to share some of their old favorites with readers. (Find them all at https://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-and-articles.html ) Robert Wexelblatt's "The Last Poem of Chen Hsi-wei" completes a series of stories, with embedded poems, featuring the adventures of the fictional peasant-poet Chen Hsi-wei. The parable-like tale tells of a visit to an aging poet by a youthful aspirant who recites to him verses that the aging bard does not recognize as his own -- leading to a reflection that is no less affecting for being inevitable: "Strange too to think of the poems I wrote long ago

So many excellent poems in the April issue of Verse-Virtual. April may be National Poetry Month, but each page of the calendar makes for a very good month of poetry for Verse-Virtual. The optional theme for poets in April was, again, 'your best poem,' a choice that enabled poets to share some of their old favorites with readers. (Find them all at https://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-and-articles.html ) Robert Wexelblatt's "The Last Poem of Chen Hsi-wei" completes a series of stories, with embedded poems, featuring the adventures of the fictional peasant-poet Chen Hsi-wei. The parable-like tale tells of a visit to an aging poet by a youthful aspirant who recites to him verses that the aging bard does not recognize as his own -- leading to a reflection that is no less affecting for being inevitable: "Strange too to think of the poems I wrote long agoand can no longer remember. They too will become so

much wind-borne chaff, having also served their uses." I found these lines intensely moving -- mentally jumping into stacks of that 'wind-borne chaff' and over-identifying the way good poems make us do.

Poet Robin Helweg-Larsen responded with three nominations for her best poem, including "This Ape I Am" -- a poem with a brilliant premise worked out with inventive rhyme and formal patterning. An example of the poem's playful verse: "Under our armored mirrors of the mind

Where eyes watch eyes, trying to pierce disguise,

An ape, incapable of doubt, looks out,

Insists this world he sees is trees, and tries

To find the scenes his genes have predefined." I love the internal rhyme and sibilance of "Insists this world he sees is trees, and tries..." The line might also serve as a good one-sentence definition of apishness. The whole poem is as fine as it is fun.

Another putative best, Judy Kronenfeld's "Time Zones" links images from different cities at a single moment in time on an ordinary Old World evening: "rooftop squatters" in Cairo; a robed figure "scuttles from cenotaph to cenotaph" in Egypt's "Cities of the Dead"; a queue forming for bread in Bucharest; "someone weeps" in "rain-smudged" Istanbul; and in the market place of Classical Athens "a gypsy child/ hangs on a tourist’s hand." Oh, the humanity, I think, but the poem is braver, allowing the ghosts of all our evenings to gather "in my own room, some press/ against my shoulder," retaining (like Homer's 'shades') their interest in life. This is a poem with a wide and moving vision.

Another reflective offering, Mary Makofske's "Milk Teeth" is an effort, the poet states, "to capture the complexity and ambivalence of motherhood." Too much time has passed for the speaker to distinguish whose milk teeth are whose, but the effort produces this lovely and fitting image of 'those years' -- "when time slowed to a leaf

seen on our walks, unfolding day by day,

or repeated itself like sandbox castles." I haven't thought of sandbox castles in a long time. This poem restores the memory of parenting days.

Another possible personal best is Penelope Moffett's "Leavening." Something life sustaining rises up in this poem's images of what I take to be the memories of a crucial day: "Five hummingbirds hover in fountain spray.

Green and purple, with lacy wingtips,

coming in for midair gulps.

They chase each other off and circle back. Noon. A dust-colored moth quivers up a screen

above the table, confused by some imagined glow

where all heat, all light swirl in." The vivid images of the existence we share with other living things introduces the poem's conclusion, which I will not spoil by citing here.

Not all of April's poems are offered as personal bests, but so many are plenty good. I love the vitality of the imagery and diction in Steve Klepetar's "Old Neighborhood." I read it with a kind of anxious pleasure in the poem's evocation of a kids' wilderness neighborhood with trees you could climb, sighing with relief at the absence of visitations by EMTs or the cops. "We knew every shortcut

through the trees, leapt over roofs

without once breaking our legs

on the long way down." Today people call this behavior 'limits testing,' if they let their kids outdoors at all. But the poem doesn't moralize. It's simply full of action verbs and vivid kid stuff: "We blew smoke rings at the moon.

Girls giggled as wind tangled their hair.

Our skinned knees throbbed and bled. " If you haven't had a chance to read this or the poet's two other fine April offerings, treat yourself.

Donna Hilbert's beautiful sonnet "Dark Spring" wonderfully captures the contradictions in its title in a rich, densely written appropriation of a classical form, as in these sonorous and happy-sad lines: "Some happiness mistakes a cry for song.

So too, some misery’s notes are crossed

with joy, and life and death belong

to the same mad throng. ..." A marvelously executed poem.

Among the rich pleasures of its form, Marilyn Taylor's "First Day in London" works in a super helping of Brit-speak. For example, this quatrain of ear-openers: "I’ll chat you up, I’ll mind the gap,

I’ll not forget my bumbershoot;

I’d love to stay till Boxing Day—

My haversack is in the boot!" I could probably find the haversack in the boot, but I have forgotten my bumbershoot too often to pass for a proper Anglophile -- just a Yank after all. Gee whiz! Many more fine poems to reward our attention in this issue of Verse-Virtual. And when April's "perhaps hand" wipes away the month's final days, they will still repay a reading.

Find all the poems and articles here:

https://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-and-articles.html

Published on April 27, 2019 21:48

April 17, 2019

The Garden of the Seasons: April Flowers -- Our Pilgrimages and Chaucer's

In April we are raking it in. That blanket of last year's dried, brown leaves, I mean, the remnant of which you see hanging about the daffodils in the top photo, and crocuses in the second photo, and in pretty much all of the other photos as well.

In April we are raking it in. That blanket of last year's dried, brown leaves, I mean, the remnant of which you see hanging about the daffodils in the top photo, and crocuses in the second photo, and in pretty much all of the other photos as well.  And this is how the ground looks after I've already done the wide-rake heavy volume removal, to clear enough space around, and leaves off, the early round of bulbs. So we can see them. These places, and everywhere else in the garden will need a second round of small-rake leaf removal when the other ground covers and flowering plants begin showing up in force.

And this is how the ground looks after I've already done the wide-rake heavy volume removal, to clear enough space around, and leaves off, the early round of bulbs. So we can see them. These places, and everywhere else in the garden will need a second round of small-rake leaf removal when the other ground covers and flowering plants begin showing up in force.  I can't remember a poem about spring raking. Spring planting, maybe -- that's for farmers, and for vegetable gardening. Almost all vegetable plants are annuals, at least in northern climates. Maybe this humble, yet labor- and time-taking ritual has yet to receive its proper attention. Most everyone associates leaf raking with the season in which they do it: autumn. But those of us growing more flowering plants than lawn (none in our case) know better. Yes, we rake in autumn as well, clearing walks and a car park area. But spring raking is our version of spring cleaning. Not for the faint of heart.

I can't remember a poem about spring raking. Spring planting, maybe -- that's for farmers, and for vegetable gardening. Almost all vegetable plants are annuals, at least in northern climates. Maybe this humble, yet labor- and time-taking ritual has yet to receive its proper attention. Most everyone associates leaf raking with the season in which they do it: autumn. But those of us growing more flowering plants than lawn (none in our case) know better. Yes, we rake in autumn as well, clearing walks and a car park area. But spring raking is our version of spring cleaning. Not for the faint of heart. So while I rake I'm thinking about April poems.

The really big one is the first one, by one of the inventors of English poetry, the diplomat and courtier Geoffrey Chaucer, whose Middle English epic exploration of the various ranks of English society in his time is called "The Canterbury Tales." The organizing principle (and hook) of this immense achievement is the vernal pilgrimage his host of characters is making to the holy shrine of the tomb of Thomas a Beckett in Canterbury. Here are the first 18 lines:

Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote,

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licóur

Of which vertú engendred is the flour; Whan Zephirus eek with his swete breeth Inspired hath in every holt and heeth The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne Hath in the Ram his halfe cours y-ronne, And smale foweles maken melodye, That slepen al the nyght with open ye, So priketh hem Natúre in hir corages, Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages, And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes, To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes; And specially, from every shires ende Of Engelond, to Caunterbury they wende, The hooly blisful martir for to seke, That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.

We were assigned to memorize these lines in my freshman year, giving them the Middle English pronunciation. Most of these words are close, or even identical, to their modern form. But we all need 'editorial' help to understand all the words. Quizzing myself today, here's what I remember:line 1, "shoures soote" is 'soft showers,' the adjective following the noun in French fashion. 2. 'droghte' is drought. Our professor pointed out there is no drought in March; the poet is pointing to a wintry 'spiritual drought'; an arid heart. 'roote,' though pronounced differently is our root. Spring rain, that is, pierces our heart to the root. 3. 'veyne' is vine. 'swich licour' is 'such liquid.' It's neat to see where our word 'liquor' comes from.

4. 'vertu' is virtue, meaning strength or power. 'flour' means 'flower' here; an interesting connection to what we make bread from. 5. 'Zephirus' is the wind, the west wind (I believe) that brings mild spring weather. 'eek' is 'also'. 'swete breeth' are our words, spelling and sound slightly altered.6. 'inspired' is 'breathed in'; again good to see the root of our modern word. 'holt and heeth' is wood and field (the latter word is 'heath' for us). 7. 'croppes' is our 'crops,' meaning new plants here; 'yonge sonne' is simply 'young sun.'8. 'Ram' signifies the month of April; astrologers pick this right up. 'The sun has run halfway through April.'9. 'smale foweles' are small birds (fowls); 'maken melodyes' is a lovely phrase for 'singing.'10. The line means 'that sleep all night with open eye,' apparently a bit of folklore.11. This line means 'so Nature pierces them in their hearts'; interestingly 'corage' means heart.

12. All the words are close to modern equivalents; 'goon' is 'go.'

13. 'Palmers' are pilgrims, because Crusaders carried them. 'straunge strondes' is 'strange shores'; we have 'strand,' British for shoreline, from the latter word.

14. The Middle English here translates to

'distant shrines, known in various lands.'

15. We have 'shires ende,' words still used, but Americans no longer say 'shire' for county.

16. The old spelling of England, land of Engles, or Angles (or maybe angels). 'wende' sounds to me like 'wind their way.'

17. Old spellings for words we still use.

18. 'hem' is 'them' (where did 'th' come from?). 'holpen' is 'helped,' what martyrs do when you pray to them. Interesting that 'seeke' is 'sick.' How different this language sounds when spoken.

Enough words more pics below. The bottom photo shows hyacinths in the process of unfolding their petals.

Published on April 17, 2019 09:02

April 11, 2019

The Garden of History: From Shakespeare's Plays to Cable News: Portrait of the Tyrant

In his new book, "Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics," Stephen Greenblatt writes that in "Richard III," the history play about the last of England's pre-Tudor monarchs, Shakespeare develops the personality features "of the aspiring tyrant."

In his new book, "Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics," Stephen Greenblatt writes that in "Richard III," the history play about the last of England's pre-Tudor monarchs, Shakespeare develops the personality features "of the aspiring tyrant." Here are those features: "the limitless self-regard, the law-breaking, the pleasure in inflicting pain, the compulsive desire to dominate. He is pathologically narcissistic and supremely arrogant. He has a grotesque sense of entitlement, never doubting that he can do whatever he chooses. He loves to bark orders and to watch underlings scurry to carry them out. He expects absolute loyalty, but he is incapable of gratitude. The feelings of others mean nothing to him. He has no natural grace, no sense of shared humanity, no decency."

Does this remind you of anyone?

Greenblatt's book makes no overt reference to contemporary politics and its leading 'characters' -- not a single word. But here is his further discussion of the psychology and behavior of the tyrant Richard III, the man who would be king: "He is not merely indifferent to the law; he hates it and takes pleasure in breaking it. He hates it because it gets in his way and because it stands for a notion of the public good that he holds in contempt. He divides the world into winners and losers. The winners arouse his regard insofar as he can use them for his own ends; the losers arouse only is scorn. The public good is something only losers like to talk about. What he likes to talk about is winning."

Winning? What's that about winning? Is there anything more we need to know about this 'winning' personality? Yes, there is:

"He has always had wealth; he was born into it and makes ample use of it. But though he enjoys having what money can get him, it is not what most excites him. What excites him is the joy of domination. He is a bully. Easily enraged, he strikes out at anyone who stands in his way. He enjoys seeing others cringe, tremble, or wince in pain. He is gifted at detecting weakness and deft at mockery and insult. These skills attract followers who are drawn to the same cruel delight, even if they cannot have it to his unmatched degree. Though they know that he is dangerous, the followers help him advance to his goal, which is the possession of supreme power." This is all very convincing, very comprehensive -- and somehow strangely familiar. I wonder why that it is.Yet there is more. "His possession of power includes the domination of women, but he despises them far more than desires them. Sexual conquest excites him, but only for the endlessly reiterated proof that he can have anything he likes. He knows that those he grabs hate him. For that matter, once he has succeeded in seizing the control that so attracts him, in politics as in sex, he knows that virtually everyone hates him..." Stephen Greenblatt's intriguing biography of Shakespeare ("Will of the World") -- the world's best known writer, and yet a man of whose personal life, habits, opinions, politics, comings and goings so little detail is known that a gang of pseudo-scholars has arisen to disprove his existence -- gave me my first living portrait of what a relatively quiet man with a very loud genius may have been like. His new book, "Tyrant," might have been called "Will of the Real World," when that adjective (as in 'real politic') has the meaning cynics and dirty fighters have always attributed to it. Richard III was not the only one of his Shakespeare's characters that the word tyrant applies too. Another king who becomes a tyrant, Macbeth, begins his play as a hero. He's not a gangster don, or, like Richard, a twisted psycho with a grudge against existence. He has both depth and imagination and the physical courage that recommends him to the king he serves, poor Duncan. But there is an inward twist that turns Macbeth to the way of the tyrant: "driven by a range of sexual anxieties: a compulsive need to prove his manhood, dread of impotence, a nagging apprehension that he will not be found sufficiently attractive or powerful, a fear of failure. Hence the penchant for bullying, the vicious misogyny, and the explosive violence." This, too, has a familiar ring, doesn't it? The bullying, misogyny, and vulnerability to taunts, in particular.

As is this observation on Macbeth's complaining about his bad dreams and constant anxiety: "the tyrant's course of behavior is fueled by a pathological narcissism. The lives of others do not matter..."

Macbeth's erratic behavior soon draws attention to his guilty conscience, a problem our author tells us is "recurrent and almost inescapable in tyrannies: observers, particularly those with privileged access, see clearly that the leader is mentally unstable."

Insecurity, over-confidence and murderous rage may seem "strange bedfellows" but they coexist in the tyrant's psychology because all personal and institutional restraints are gone. In another telling observation, Greenblatt notes "The internal and external censors that keep most ordinary mortals, let alone rulers of nations, from sending irrational messages in the middle of the night or acting on every crazed impulse are absent."

Personally, I try to keep a rein on my crazed impulses until at least after that first cup of coffee. Some other people, apparently, find that hard to do.

But who would choose, or seek, to become a tyrant? In Macbeth's famous "tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow" soliloquy, one of the most quoted passages in Shakespeare, the playwright is not describing the human condition, Greenblatt argues, but the tyrant's condition. In the tyrant's own words: "[Life] is a tale told/ by an idiot, full of sound and fury,/ Signifying nothing."

Didn't we hear a few of those tales in the 2016 campaign? Haven't we been hearing them ever since?

This book finds outbreaks of tyranny in other plays, including some of the greatest. Lear's blind narcissism leads to the destruction of his realm. The temptation of absolutist power leads to Caesar's death and civil war in Rome. Coriolanus's autocratic longings destroy the career of a hero who had once saved Rome.

Shakespeare undoubtedly saw a lot of tyrannical tendencies in his own Elizabethan and Jacobean times. He probed "the ways that communities disintegrate," Greenblatt tells us, "and he deftly sketched the kind of person who surges up in troubled times to appeal to the basest instincts and to draw upon the deepest anxieties of his contemporaries."

Hmmm, what would that kind of person would be like today?. Methinks I spy the like.

The only comfort I can find in this timely book's analysis of the kind of moral monster who 'surges up in troubled times' is the author's final summary of the career of the tyrant:

"Sooner or later, he is brought down. He dies unloved and unlamented. He leaves behind only wreckage."

It's the scope of the potential wreckage that keeps me awake.

Published on April 11, 2019 21:57

April 2, 2019

The Garden of Verse: The Last Man Prophesies the End of the World, Henry David Thoreau Speaks for the Wild, and Other Thoughts on April

The theme for this month's issue of Verse-Virtual is "your best poem." This is like being asked to name your favorite child, so we crafty poets, knowing how to read between the lines, came up with various ways to play with this idea without ever committing to a clear answer to this question. Sort of like a witness responding to the Mueller investigation.

The theme for this month's issue of Verse-Virtual is "your best poem." This is like being asked to name your favorite child, so we crafty poets, knowing how to read between the lines, came up with various ways to play with this idea without ever committing to a clear answer to this question. Sort of like a witness responding to the Mueller investigation. So here is the 'note' I wrote introducing my two linked-poems in the April issue:

"I'm copping out on the difficult task of offering an unambiguous selection of 'my best poem,' a voluntary theme for this issue. Long ago, writing poems before I published any, I produced a poem with a favorite title: "The Last Man." It was an image befitting my youthful central themes of solitude and estrangement, a perceived alienation from most of my fellow humans inhabiting both tiny rural hamlets and big cities. I'd sampled both. I don't have that poem any more. Instead, I've tried updating that loner stance through imagining the condition of a solitary, de-gendered survivor in a world ravaged by the climate apocalypse toward which we are stumbling, eyes wide-blinded.

I then attempted to rhyme these notions against a vision of "the last man" both to know from experience and to prophesy in behalf of the American wild, Henry David Thoreau."

Here's an excerpt from the first poem, titled "The Last Man":

He cleans his shoes with dusty walks, fills his lungs with every hour's darkling spite, hides in his bed of unwashed rags lest anyone (but who?) observes that his sheets have stood up and left, giving up on him as he has given up on so many things

his ineptitude his car sobs in the night his stars pick his pocket he follows the eyes of yesteryear's teenagers in imaginary streetcars hours so late that no one notices where they go, or where he goes, or where shee/ goes without him

A here's an excerpt from the poem about Thoreau, titled "The Last True Man," which I should better describe as a prose-poem:

He knew railroad men and lawyers, local farmers, doctors

with their bad news

and perhaps not the last, but one of the finest exemplars of the last generation

of Penobscot hunters and fishers, the newspaper-reading Polis,

who butchered before him the carcass of the moose he had killed,

sickening Henry

while winning the white nature-lover's respect for his native mastery of the wild.

He knew scientists, botanists, zoologists to whom he served up

a new species of fish, which they neglected to name

for him.

He corresponded with European naturalists

on the life and death of forests, pioneering the science of forest succession

You can find these poems at: http://www.verse-virtual.com/robert-knox-2019-april.html

And find the issue's full contents at

http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-and-articles.html

Published on April 02, 2019 12:05

March 31, 2019

The Garden of Tears: Ask Afghanistan, Iraq, Venezuela, and now Yemen About America's 'Gifts' to the World

America needs to change the way it does business with the rest of the world.

America needs to change the way it does business with the rest of the world. And there's one business in particular we should get out of: Selling arms to tyrants who wish to kill their neighbors. In fact, to judge our intentions by our actions, the United States is no longer

building weapons of war for the purpose of defending ourselves against potential enemies. We're inventing wars in order to sell weapons.

building weapons of war for the purpose of defending ourselves against potential enemies. We're inventing wars in order to sell weapons. That's the conclusion drawn by Kathy Kelly, who has visited our war zones all over the world, founded the nonprofit Voices for Creative Nonviolence (www.vcnv.org), and in recent weeks has been speaking to small groups meetings in Massachusetts churches.

Here is one of her conclusions: "We in the United States have yet to realize both the futility and immense consequences of war even as we develop, store, sell, and use hideous weapons. The number of children killed is rising." We heard Kelly speak at a church in Walpole, Mass., where she came to put a spotlight on the current, ongoing example of America's willingness to support a war by a rich country on a poor country -- for no justifiable cause -- but out of an apparent desire to keep business flowing for our prosperous armaments industry. The victim of this war is Yemen, a poor Middle Eastern country of nearly 30 million people, often described as 'backward,' that has the misfortune to the be the neighbor of a large, wealthy, disastrously governed sheikdom called Saudi Arabia. A few days after we heard Kelly, she posted this news: "At 9:30 in the morning of March 26, the entrance to a rural hospital in northwest Yemen supported by Save the Children was teeming as patients waited to be seen and employees arrived at work. Suddenly, missiles from an airstrike hit the hospital, killing seven people, four of them children." Those missiles and the explosives inside them were almost certainly supplied to the Saudi government by the US. We also sold the Saudis the absurdly expensive aircraft which poured death upon patients waiting at a hospital to see a doctor. One might ask: How do we live with that? When we heard Kelly speak in a church hall in Walpole, a Boston suburb, she also suggested this motivation for America's continued and destructive meddling in the affairs of other countries. Since the end of the Cold War we have assumed the right to throw our weight around, both openly and covertly when and wherever we choose: If a government doesn't run its country in a way we approve of, the United States will do what it can to take that government down. And we don't care what the damage is. Ask Afghanistan. After the Taliban government of that country provided protection for Al Queda terrorists who attacked America on nine-eleven, we had cause to invade and overthrow a terrorist-protecting government. But once that goal was accomplished, we refused to go home. We're still there today, throwing fuel on that unhappy country's domestic fires in the form of endless weaponry, protection money and occasional bribery, while holding out the delusional hope of crushing the Taliban opposition. Afghanistan has paid a steep price for our continued intervention. In the eighteen years of what Afghans call 'the American war' more than 150,000 Afghans have been killed, an estimated 40,000 of them civilians. American casualties are almost 2,400 military deaths, plus another 1,700 civilian and contractor deaths. The financial cost is measured in the trillions. Last year the Congressional Budget Office put the cost at $2.4 trillion. Ask the Venezuelans. Because Washington disapproved of their popularly elected Socialist government that raised the standard of living for the country's poor and even provided low-cost heating oil for American fuels assistance programs in the 1990s, the Bush administration took part in a failed coup attempt to remove President Hugo Chavez, back in 2002. Under Obama, American sanctions exacerbated Venezuela's economic problems (initially caused by falling oil prices and its government's mismanagement of currency exchange rates), even though current President Maduro was popularly elected in 2013 to continue Chavez's policies. Now, of course, we have a bombastic blowhard-in-chief who has basically called for a military coup by Maduro's opponents. Meanwhile civilians line up for food. Many seek to flee the county and become refugees. Or, ask the Iraqis. Because some Islamic country (other than Afghanistan) had to pay for the nine-eleven attack by an terror organization founded and headed by Saudi leaders, and mounted by Saudi nationals, GW Bush invented a pretext to invade Iraq. That country is still trying to recover from the war's disastrous consequence. Estimates of Iraq's death toll range from half million dead to a catastrophic 2.4 million. ISIS, which arose after the US war threw the country into chaos, contributed some of these. On the American side, the casualty toll is 4,425 deaths and near 32, 000 wounded in action. The financial cost to the US taxpayers is again estimated in the trillions of dollars. Now it's Yemen's turn. What did Yemen do to us? (you may ask). Absolutely nothing. Why then do we support with airplanes, armaments, active support for combat missions, and huge war machinery and armament transfers to the blatant aggressor state, Saudi Arabia, in its wholly unjustified war intentionally waged on Yemen's civilian population. Estimates by international organizations with worldwide credibility such as Save the Children estimate that 85,000 children under age 5 alone have been killed by Saudi attacks and disruptions of Yemen's economic and social system. Thousands of children have starved to death. According to UNICEF, Doctors Without Borders, and other international organizations, a cholera epidemic has killed more than 2,000 people and infected almost a million. The famine caused by Saudi attacks on Yemen's food supply system has put millions of people, including 400,000 children on the edge of starvation. Only recently, after three years of war on children and other living things, has the obscene slaughter moved the American Congress to express its disapproval of our role in enabling these daily war crimes. After decades of visiting overseas war zones, protesting wars and weapons of mass destructon, and backing humanitarian measures, Kathy Kelly came to Massachusetts with a local message. The conflagration in Yemen may appear far way, she told us, but its fires are lighted "right in our backyard. Massachusetts-based Raytheon Company is a key player in the war crimes being committed in this epic human disaster." Raytheon has headquarters in Waltham, and weapon-making factories in Cambridge, Burlington, Woburn and five other Eastern Massachusetts communities. It's as American as apple pie. Only the pies blow up in people's faces, and kill them. After a laser-guided 500-pound bomb stuck a water-drilling site in Yemen, killing 31 civilians, the debris included a piece of the bomb's wing assembly, with a stock number and date of date of manufacture that showed it was built by nobody but Raytheon. Proud supplier of this murderous moment, we ask: What do you say when history calls you to account for the use made of your fine products? As 'host' to this hub of America's military industrial complex, Massachusetts is the technology hive for preparing the deadly bombs, missiles, planes and targeting systems for Saudi Arabia's war crimes against people who pose no threat to America. Nor, for that matter, have they done any harm to the Saudis -- except to refuse to knuckle under. In this last respect, Saudi Arabia has done nothing more than model its egregious might-makes-right policies on those of other powerful countries -- a leading example being the USA. American 'foreign policy' needs a complete top-to-bottom shake-out. It didn't happen during eight years of the Obama administration. In mitigation of the former the former President's backing of Saudi Arabia's war on Yemen, Kelly said that Obama had reduced American support for Saudi aggression before the end of his term. The arrival of the current bellicose Pretender, however, signaled a green light for war-makers of all description. Saudis, Israel, CIA contractors and clients: Take what you want, kill all you need to. Even better if you're willing to buy our latest, high-priced, deadly swag.

A final thought from Kathy Kelly:‘Every War Is a War Against Children.’

Published on March 31, 2019 21:16

March 24, 2019

The Garden of Verse: Poets Bring Their 'Bests' to March Issue of Verse-Virtual

For the March issue of Verse-Virtual editor Firestone Feinberg chose "my best poem" as a voluntary theme. He reports receiving "some terrific responses."

For the March issue of Verse-Virtual editor Firestone Feinberg chose "my best poem" as a voluntary theme. He reports receiving "some terrific responses." Here's one: "Deer Crossing," by Penny Harter, relates the disturbingly frequent daytime appearances of a local deer population, including carcasses on the highway, to the hidden processes of human consciousness. After reporting sightings of a a dead buck and doe on the highway, the poem takes a strong psychological leap:"I only know the boundaries are blurring:

that buck whose antlers flowered on his head

like found money,

slept in your bed last night,

that doe in mine,

while we stumbled in our nakedness,

running on all fours..." I love the image of the flowering of the antlers "like found money," and the feeling the whole poem give me that, yes, this is how dreams work.

Donna Hilbert's offering of 'a best' is the short poem "Gravity" that serves "as a sort of foreword" to her book of the same name. This poem has me on its first line "What binds me to this earth..." Its four appearances by the word "mother" anchor the poem to a spiritual gravity and the culminating "miracle" that is its message. If you haven't read the poem, please do.

I'm not sure if the poem "To the Mother of a Dead Marine" by Marilyn Taylor is offered as a 'best poem,' but it certainly belongs to that discussion. A sonnet, the poet tells us, is the suitable form for distancing the self in order to "write genuinely difficult poems." And its context of confronting the mother of "a dead marine" surely meets that threshold. In its packed 14 lines we find such images as "Could I have been the beast he rode to war?

The battle mounted in his sleep, the rounds

of ammunition draped like unblown blossoms

round his neck?" These 'unblown blossom' are not found money, or anything beautiful, but something closer to 'fleurs du mal.' Amazingly strong writing in one of those poems that, as the poet tells us, "scare" us to write.

It can't be a complete accident, can it, that so many of these strong poems speak of death? When Scott Waters' poem "capitulation" begins with mention of soldiers, we are prepared to cross the border to that final country again, but this poem takes us elsewhere. Its formal elements -- the repetition of the line "these soldiers on the hill," and the delayed rhyme that concludes each stanza -- are highly satisfying. The poem feels like a prayer -- of thanks, or appeal.

Poet Alan Walowitz presents what he describes as "my best recent poem about getting old. " Sometimes a good poem is a really good story told really well. Here's the money shot in the poem titled "Road Kill":"Like when you finally--and against your better judgment--say, I love you

to one so dear you’d even be willing to bear the silence

such a proclamation might inspire.

Then the voice of the lady from Waze, seductive as a Siren,

wakes you soft and sweet, and without the heavy breathing

you’d counted on any time you used to be lashed to the mast,

and finds a new way to make you listen:

Roadkill on road ahead, she sings,

and there you are, looking for the corpse,..." The poem makes very good use of this magic technological moment in exploring the complexities of the aging human condition. I'm beginning to think the "lady from Waze" deserves to be acknowledged as a player in many of our stories. Her three-word title sounds like something out of a contemporary "Idylls of the King."

Among the many other fine poems in the issues, Joan Mazza's ekphrastic poem "Blown Away" speaks eloquently to the power of a female figure: "assembledof gears and sinuous metal scrap,windswept yet holding firm to form." You have to see the photo of the sculpture by Penny Hardy and read the rest of the poem to appreciate its evocation of the figure's "self-made light."

Steve Klepetar's poems continue to put to rest any questions I may have had about the impact of winter in Berkshire County, or I suspect, in any other piece of country in the northern states outside the big cities. The answer is intense, sometimes spooky, and always metaphysical. In a poem titled "Halfway Through the Month" we encounter these aspects of the wintry mix and more. "Night has fallen, and you have

returned through the yard,

your face pressed cold against

window glass.

In the streetlight you look

so pale and old, shrunk

to a child’s body, and then,

when I look again, no body at all..." Nor do I ask who the "you" is in these lines, or why "you look so pale and old," and "shrunk to a child’s body," or why that body is almost immediately transformed to "no body at all." The reference is to everything 'out there' -- and probably everything 'in here' as well.

Robert Wexelblatt's poem "Naming and Dividing" belongs to a discussion of anybody's best poems. It's an encyclopedia of finely wrought lines and provocative lists, from the first stanza's "Newborns need milk, love, and names" ...to its demonstration of why classification is a purely, and essentially human task: "The droning plains and rhyming

hills, the singular salt ocean and the

immeasurable eons, these care nothing

for our dividing and naming, no more than

a pack of wolves padding across some line drawn

to fix Wyoming south of Montana..."...to the poem's tangy lists of places and names -- "Baltimore, Bamako, Bryn Athyn, the Bronx" -- to pick just a very few. And its culminating sense of completion through rhyme: "Give us latitudes and longitudes

and we’ll make a map and scribe a border,

we’ll christen streets, name neighborhoods

to limn a reassuring order." More good verses surely lay ahead. Editor FF has roped the April issue into the best poem rodeo

Published on March 24, 2019 18:02

March 19, 2019

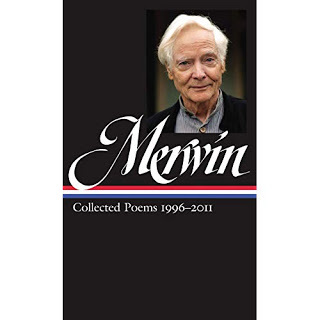

The Garden of Verse: W.S. Merwin and the Postwar Poets

The death of the poet W.S. Merwin last week caused me to think about matters that I haven't recalled in a long time. I felt bad, of course, that an important voice in a form of human expression I love has gone quiet, just as if a star blinked out in the firmament. Yes, there are other stars... but, still. My first response to news of his death -- and the full page, beautifully researched and written obituary the New York Times published last Saturday, March 16 -- was regret that I had failed to find my way to his poetry in recent years. And that, in fact, I would have to go back a long way back in the storehouse of memory to summon recollections of encounters with someone so widely acknowledged as a force in American poetry. But this was not my only slight. That storehouse librarian of the past, unreliable as he no doubt is, also revealed empty shelves where the books of other important poets should be. And certainly could be. We are losing their witness. The poets who saw the last World War, and the years of recovery from it, are dying off. We know that American WWII veterans -- my father among them -- are now largely gone, so this expanding vacuum should not be news to anyone (even me). But when I read about the poets that Merwin knew personally, studied under, or otherwise encountered, I came across much of the roster of the American and English poets whose works I read in the late sixties and seventies. Back when I began quietly, mostly privately, auditioning for the role of poet. To start with, Merwin (as I read in www.poets.org) was born in 1927, which means he was only 18 when World War II ended. He was not of an age of those called upon to serve in the military for that war, but those whose adolescence fell under its shadow. (My father, for comparison, was 21 when he enlisted in 1942.) According to poets.org, Merwin was part of a poetry hot spot at Princeton University, where he arrived just at the war's end and studied under the influential critic R.P. Blackmur, one of the major lights in the school of thought known as New Criticism. That was still the fashion in my college years and was explained to me as restricting criticism's role to a "close reading" of poetic texts while avoiding biography or other other concerns -- perhaps, it occurs to me now, as a way to avoid the ideological struggles of the earlier decades of the 20th century, when Marxism, social realism, and reactions such as McCarthyism, were the lenses through which literature was often regarded. In view of the return to the ideological approach of "critical studies" criticism in recent decades, a destructive academic fashion in my view, maybe the 'new critics' were on to something. I discovered in the same source that Blackmur's teaching assistant at Princeton was John Berryman. There's a name I can recall with enthusiasm. I loved Berryman's "Dream Songs," some of them new published when I read them. I was fascinated by the device of filtering the poet's own thoughts and experiences through an invented poor schmuck of a character ("Henry") to achieve the detachment perhaps necessary to write lines such as:

The death of the poet W.S. Merwin last week caused me to think about matters that I haven't recalled in a long time. I felt bad, of course, that an important voice in a form of human expression I love has gone quiet, just as if a star blinked out in the firmament. Yes, there are other stars... but, still. My first response to news of his death -- and the full page, beautifully researched and written obituary the New York Times published last Saturday, March 16 -- was regret that I had failed to find my way to his poetry in recent years. And that, in fact, I would have to go back a long way back in the storehouse of memory to summon recollections of encounters with someone so widely acknowledged as a force in American poetry. But this was not my only slight. That storehouse librarian of the past, unreliable as he no doubt is, also revealed empty shelves where the books of other important poets should be. And certainly could be. We are losing their witness. The poets who saw the last World War, and the years of recovery from it, are dying off. We know that American WWII veterans -- my father among them -- are now largely gone, so this expanding vacuum should not be news to anyone (even me). But when I read about the poets that Merwin knew personally, studied under, or otherwise encountered, I came across much of the roster of the American and English poets whose works I read in the late sixties and seventies. Back when I began quietly, mostly privately, auditioning for the role of poet. To start with, Merwin (as I read in www.poets.org) was born in 1927, which means he was only 18 when World War II ended. He was not of an age of those called upon to serve in the military for that war, but those whose adolescence fell under its shadow. (My father, for comparison, was 21 when he enlisted in 1942.) According to poets.org, Merwin was part of a poetry hot spot at Princeton University, where he arrived just at the war's end and studied under the influential critic R.P. Blackmur, one of the major lights in the school of thought known as New Criticism. That was still the fashion in my college years and was explained to me as restricting criticism's role to a "close reading" of poetic texts while avoiding biography or other other concerns -- perhaps, it occurs to me now, as a way to avoid the ideological struggles of the earlier decades of the 20th century, when Marxism, social realism, and reactions such as McCarthyism, were the lenses through which literature was often regarded. In view of the return to the ideological approach of "critical studies" criticism in recent decades, a destructive academic fashion in my view, maybe the 'new critics' were on to something. I discovered in the same source that Blackmur's teaching assistant at Princeton was John Berryman. There's a name I can recall with enthusiasm. I loved Berryman's "Dream Songs," some of them new published when I read them. I was fascinated by the device of filtering the poet's own thoughts and experiences through an invented poor schmuck of a character ("Henry") to achieve the detachment perhaps necessary to write lines such as: There sat down, once, a thing on Henry’s heartso heavy, if he had a hundred years& more; & weeping, sleepless, in all them timeHenry could not make good.

Third-person indirect is a common technique in writing fiction, but using it in verse seemed to me to deliver an extra power, abetted of course by Berryman's powerful, funky voice (as in "in all them time").

Young, impossibly talented, tragically destined: we read her cries and whispers and asked how can we live in a world where nobody stepped in to save Sylvia Plath? I could not wait to try this out on my own, though I don't remember if I did. Frankly just reading these lines, and the following two to end the stanza -- "Starts again always in Henry’s ears/ the little cough somewhere, an odour, a chime." -- makes me want to go there again. Merwin's career then crosses other intriguing paths. At Princeton he was a classmate of Galway Kinnell, another highly regarded poet in that 'just-after' world war generation, whose Selected Poems (1980) won both a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Kinnell, who died in 1984, is another poet on my guilt list; I've never read him except for accidental crossings in a publication. Some time after graduating from college, publishing his first book, and winning a major prize, Merwin was awarded a fellowship that brought him to Cambridge, Mass. Living in Boston, the source tells us, "he entered the circle of writers that surrounded Robert Lowelland decided to concentrate on poetry." When it comes to postwar American poets, Lowell has always been the leader in the clubhouse. He's the only poet of this generation whose work I came across in an "American Studies" course. Poems from "Life Studies" and "For the Union Dead" provided my first experience of a contemporary voice on contemporary issues, including the poet's own 'problems.' World War II is both subject and experience for this poet, who became a conscientious objector because of the war and spent time in jail for draft refusal. Lowell's first 'major poem' was an elegy for the death of his cousin, who enlisted and drowned in the North Atlantic after his ship was targeted and sunk by the enemy. "The Quaker Graveyard at Nantucket" draws on the tradition of 'elegy' in English poetry, but then expands it by alluding not to classical elegies (as Milton and Shelley did) but to classic American texts. Poet Robert Haas (in "A Little Book on Form") points out that Lowell echoed lines and imagery from Thoreau's book "Cape Cod." Thoreau was describing his search for remains and personal effects from the wreck of a ship from Galway, Ireland, carrying many immigrants and some Americans (including Margaret Fuller): "I saw many marble feet and matted heads as the clothes were raised, and one livid, swollen, and mangled body of a drowned girl..." Lowell wrote: "Flushed from his matted head and marble feet..." Merwin and his first wife left then Boston for Europe and lived in London where they encountered -- who else but Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes? Plath, born in 1932 and still a child in Depression America when the world war began, was already dead when late sixties young people discovered her work. In my experience, she was the only poet read by non-English majors. She was on the top of my list for 'contemporary' poets in those days because of the linguistic intensity of her confrontations with her own experience; that sense of shouting in the dark that we all sometimes feel, perhaps particularly when young.

Young, impossibly talented, tragically destined -- we read the poet's cries and whispers and asked how can we live in a world where no one stepped in to save Sylvia Plath. Hughes, born in 1930, was a highly regarded postwar poet in England. Though I tried to admire the poems in his book "Crow," Hughes never really moved the needle for me. I have read recently that in postwar England only three poets mattered: Phillip Larkin, Hughes, and Thom Gunn. My attempts at reading Gunn, born in 1939 and apparently regarded as an 'anti-establishment' working class voice, left me wondering what the fuss was about. Possibly, his 'outsider' stance paled in comparison to the vitality of the American protest and social criticism poetry of Ginsberg and the other Beats, that fed other voices of the Sixties. Phillip Larkin, in contrast, is exactly the other kind of poet, so rigorous and exacting that his poems appear at times to hover right on the edge between brilliant and precious. Yet Larkin is famous in the macro-culture for a single Sixties-sounding line: "They fuck you up, your mum and dad.."

I'll get out the way here and allow two of Merwin's poems ("Thanks," and "Yesterday") to speak for themselves:

Thanks

Listen with the night falling we are saying thank you we are stopping on the bridges to bow from the railings we are running out of the glass rooms with our mouths full of food to look at the sky and say thank you we are standing by the water thanking it standing by the windows looking out in our directions

back from a series of hospitals back from a mugging after funerals we are saying thank you after the news of the dead whether or not we knew them we are saying thank you

over telephones we are saying thank you in doorways and in the backs of cars and in elevators remembering wars and the police at the door and the beatings on stairs we are saying thank you in the banks we are saying thank you in the faces of the officials and the richand of all who will never changewe go on saying thank you thank you