Robert Knox's Blog, page 32

March 19, 2017

The Garden of Time: Is There Life on March?

Is March the most changeable month of the year?

Is March the most changeable month of the year? Is it winter, or is it spring? Is it the month when things are growing? Or the month when it's still snowing? Wheels are turning? Sunsets burning? Will we see bulbs blooming? Or plows prowling? Snow blowing? Wind howling?

The top photo was taken earlier this month at the start of one our frequent snow events, before the garden began filling up with snow. I don't know if bulbs, ground cover plants like the Vinca Minor, or anything else is breaking earth, greening up, or growing new leaves, because if they are, they are doing it beneath the layers of snow or ices, accumulating or melting back over the last three weekends.

For color we have relied on the feathered flowers of the air, particularly the sharp contrast of red male cardinals against the monochrome white snow days. The second photo down, taken roughly a week ago is an example of the redbird phenomenon.

For color we have relied on the feathered flowers of the air, particularly the sharp contrast of red male cardinals against the monochrome white snow days. The second photo down, taken roughly a week ago is an example of the redbird phenomenon.  What about other Marches? Last year we were pretty much snow free. The red-tailed hawk, in the third photo, was setting up show in the Quincy shoreline salt marsh, looking for lunch in the increasingly active vernal life of birds, bugs, rodents, squirrels and rabbits. I found the hawk there for weeks. At home in the crocuses, white and violet, were breaking ground, along with the Lenten Rose (Helleborus), shown in the next three photos.

What about other Marches? Last year we were pretty much snow free. The red-tailed hawk, in the third photo, was setting up show in the Quincy shoreline salt marsh, looking for lunch in the increasingly active vernal life of birds, bugs, rodents, squirrels and rabbits. I found the hawk there for weeks. At home in the crocuses, white and violet, were breaking ground, along with the Lenten Rose (Helleborus), shown in the next three photos.

Two years ago, I took no photos of the garden at all in this putative first month of spring, as I was tired of looking at the snow cover which endured through all of February and March, until the last few days. The photo below the violet crocuses, shows the back garden as it appeared in the first few days of April. Bleak, brown, shorn, severe, with nothing showing of new green. It looked spared down for winter; or like a teenaged boy with a bad haircut.

Two years ago, I took no photos of the garden at all in this putative first month of spring, as I was tired of looking at the snow cover which endured through all of February and March, until the last few days. The photo below the violet crocuses, shows the back garden as it appeared in the first few days of April. Bleak, brown, shorn, severe, with nothing showing of new green. It looked spared down for winter; or like a teenaged boy with a bad haircut. The photo beneath that one, taken that same year, shows the first signs of green returning from the earth. Tulips and vinca emerging from the earth. I was clearly desperate to take a photo of something. We were a week or two into April.

The photo beneath that one, taken that same year, shows the first signs of green returning from the earth. Tulips and vinca emerging from the earth. I was clearly desperate to take a photo of something. We were a week or two into April. The year before that, March of 2014, we were visited with enough snow to cool my enthusiasm for signs of spring. I include one photo from March of that year, though not taken in the garden.

It was taken on the last day of the month in the sculptural gardens of Paris, actually in the Place de la Concorde. No flowers in this Place, though we found quite a few in the nearby public gardens, but I think a few of the goddesses depicted in this fountain sculpture are standing in for the bounties of nature.

It was taken on the last day of the month in the sculptural gardens of Paris, actually in the Place de la Concorde. No flowers in this Place, though we found quite a few in the nearby public gardens, but I think a few of the goddesses depicted in this fountain sculpture are standing in for the bounties of nature.

Published on March 19, 2017 20:52

March 15, 2017

A New Warning for the Ides of March: Beware the Weather!

We have had some wicked months of March lately.

Nobody around here will ever forget March 2015. Most everybody has already forgotten March 2016.

Two years ago, while February was the heavy snow accumulation month, the snow hung on the ground all through March because the weather never warmed up.

Last year, 2016, the "mean temperature" for the month of March was 42.5F with an average high of 50. (Fifty sounds pretty good in these chilly wind days we've been getting used to in March this year,) The photo above shows an early spring bloomer, the Lenten Rose (Hellebores) that bloomed in March of 2016.

In 2015 the mean temperature for the month of March was 33.3. That's a huge difference from last year's 42.5. Two years ago the snow pack sat on the ground refrigerating the air above it. Because the air temps seldom got much above freezing the snow melted very slowly. Because the snow didn't melt, the temperature stayed cool. A vicious cycle.

Last year's high temp recorded in March was 77F; two years ago, only 57.

The second photo, showing the Quincy shoreline, was taken in March of 2015. Not much green in the middle of March in our garden either; nothing blooming, nothing even showing.

The second photo, showing the Quincy shoreline, was taken in March of 2015. Not much green in the middle of March in our garden either; nothing blooming, nothing even showing. This changeable third month of the year is no longer proving a "comes in like a lion, goes out like a lamb" month. It's either an entirely lionish month, or a mostly lamb-like one. (Maybe some Marches will go back to registering somewhere in the middle -- sheepish, let's call them.)

The lowest temperature recorded in March last year was 21. The lowest in March of 2015 -- 9. With its coastal waters already beginning to warm (except for the old snow we kept dumping into them), Boston recorded a temperature of 9F.

[Data from Weather Warehouse: http://weather-warehouse.com/WeatherH...] This year, halfway through March 2017. tomorrow's predicted high is 32 -- not a lot of melting from Tuesday's snow dump to be expected. The historical for the date is 45. That's the way the last 10 days or so have been running -- well below average. The first day of march this year produced a high of 63F, 20 degrees over the date's average, and the month hasn't gone anywhere near that since. We've had a high of 58 a week ago, but also a couple of weekend storms, followed by arctic cold fronts, approaching record lows for their dates. Lows of 10 and 9 on the month's first weekend, followed by exactly the same two figures on the second weekend. Also lows of 16, 23, and 14 on Monday night, right before the arrival of Tuesday's blizzard. We're heading back down again.

[Data from Weather Warehouse: http://weather-warehouse.com/WeatherH...] This year, halfway through March 2017. tomorrow's predicted high is 32 -- not a lot of melting from Tuesday's snow dump to be expected. The historical for the date is 45. That's the way the last 10 days or so have been running -- well below average. The first day of march this year produced a high of 63F, 20 degrees over the date's average, and the month hasn't gone anywhere near that since. We've had a high of 58 a week ago, but also a couple of weekend storms, followed by arctic cold fronts, approaching record lows for their dates. Lows of 10 and 9 on the month's first weekend, followed by exactly the same two figures on the second weekend. Also lows of 16, 23, and 14 on Monday night, right before the arrival of Tuesday's blizzard. We're heading back down again. As I write Wednesday night the current temp is 23, with a predicted the overnight low of 17. Tomorrow, March 16, is predicted to warm up to a balmy 32. I don't think the frozen ice-cap on the my driveway will do a whole lot of melting under those conditions. [according to http://www.accuweather.com/en/us/bost...]

Given the amount of rain we got with the so-called blizzard that brought lots of wind, the very wet snow we received hardened overnight into un-removable state locally described as "it's a rock." Trapped behind the ice barricade left by the plows, our car was liberated only because neighbors arrived with a classic old-fashioned ice chopper and a heavier metal shovel than I possessed. A steady round of downward chopping created the impression of a three-guy work gang pounding stone. That's one dead metaphor that will come alive for me. The third photo I've posted here is my "calendar shot" so far for March of 2017. I don't know when I'll get to check on the progress of the Lenten Rose.

In today's newspaper I'm told that, one, we may get another snowfall this weekend. And, two, that overall this turn for the cold is a good thing for farmers and gardeners. According to Eric Fisher writing about weather for the Boston Globe , the record warmth of late February was posing threats to plant vitality.

Fisher writes: "If the record warmth had stuck around for another four or five days, peach buds would have swelled and more plant life would have surged into action much too early....We may have switched back to winter weather in time to keep everything asleep until the more appropriate late-March to early-April time frame."

OK. I'm very big on the early spring emergences of late March and early April and can wait another two weeks to enjoy them. Just don't tell me we're going to get another brontosaurus-long winter like the one two years ago any time soon. I have plants, a rhododendron and a boxwood to name two big ones, that will never be the same. And neither, I suspect, will I.

Published on March 15, 2017 21:52

March 12, 2017

The Garden of Verse: The Search for the Truth of America and Other Poetic Journeys

The prose introduction to Dick Allen's poem "I Was Eighteen" in the March issue of Verse-Virtual is a poem by itself: "So in the summer of 1958, I hitchhiked, train rode, bus rode, and walked about our nation. Ever since, I’ve doubted any truth about America that doesn’t stumble on rural dirt roads and stand under inner-city streetlights."

The prose introduction to Dick Allen's poem "I Was Eighteen" in the March issue of Verse-Virtual is a poem by itself: "So in the summer of 1958, I hitchhiked, train rode, bus rode, and walked about our nation. Ever since, I’ve doubted any truth about America that doesn’t stumble on rural dirt roads and stand under inner-city streetlights." The poetry of names rides along on this villanelle's refrain: Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska—

when I was eighteen I hitch-hiked across them,

trying to find out the truth about America.

I love this poem's candor and expansive innocence. The poet simply hitchhikes across the country "In sunlight and storm" -- imagine your son proposing to do that today? -- asking himself and those he meets for the "truth about America." The innocence of the boy -- "But I was eighteen, naïve as clam chowder" -- reveals something about the nobility of the quest, and the country in which he pursues it, even if by itself it does not lead to wisdom. In the poem's final stanza that last line becomes: they just smiled when I asked them the truth about America.

In the villanelle "So Easily Do Women Weep" by William Greenway, the formal repetitions of the refrain reveal meaning through shades of emphasis. Is the poem truly about how easily women weep, or is it (as the developing stanzas indicate) about what men hide from women? The first stanza foregrounds the alleged ease, and copiousness, of women's tears, and appends the reflection on male tears in a subordinate clause, the second of the two refrains. So easily do women weep

you wonder why the seas don’t overflow

and though a man may sorrow just as deep

But the emphasis shifts in later stanzas to: the depth of grief we keep

is something she must never know

so easily do women weep.

That ease of women's tears turns into men's excuse for keeping their grief unshared. (Face it, guys, we know this is true.)

Joyce S. Brown's "Villanelle to a Golfer" turns the form into a dialectic. At the start we learn "To me life seems more Hardy than Voltaire." She stakes out Hardy country by walking through the storm, while the golfer dresses for the links. Later, when the golfer exhibits some vulnerability, we learn: Now you’ve become more Hardy than Voltaire. But at the end poet and golfer are living in the universe after all: the dark, the light of Hardy and Voltaire.

Margaret Hasse's "Divorce Proceedings" modifies the refrain of the antagonistic couples -- "They burn with anger as they slam the door" -- to spell out the necessary corollaries of a couple who, as the poem says, "banish their better angels./ No,

they cannot live the life they had before." Every aspect of their prior life together goes out that slamming door: A signed decree and marriage is no more.

Wedding china, photos, the blue tent—go.

The final version of the refrain is the necessary conclusion of the "burning anger" we heard about in the first stanza, using most of the same words repurposed: They can never live the life they had before

everything burned and they closed the door.

The moral? Don't shut the door on the flexible value of the villanelle. You can read the rest of these poems, and all the others, at http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an...

Published on March 12, 2017 19:34

March 10, 2017

The Garden of Verse: Dancing the Villanelle

Here's the beginning of a poem by Michael T. Young in the current, March 2017 issue of Verse-Virtual, the online poetry journal. The title is "Expecting a Trump Presidency" which, right there, gives you some idea of what to expect from its content and, perhaps, its mood: It surely won’t be as bad as people say. The news plays on our fear, exaggerates. It’s not like they’ll be marching us away.

Here's the beginning of a poem by Michael T. Young in the current, March 2017 issue of Verse-Virtual, the online poetry journal. The title is "Expecting a Trump Presidency" which, right there, gives you some idea of what to expect from its content and, perhaps, its mood: It surely won’t be as bad as people say. The news plays on our fear, exaggerates. It’s not like they’ll be marching us away.The poem is written in the form called the villanelle. My only real knowledge of this form is that it was used by Dylan Thomas in a poem whose refrain is quoted as often as almost any poem produced in the 20th century. (Maybe a few lines from Robert Frost are a little bit ahead.) The refrain in Thomas's poem is: "Do no go gentle into that good night/ Rage, rage against the dying of the light." The villanelle format creates some structural impediments to keep those lines apart. The poem must have six stanzas, the first five consisting of only three lines. The two lines of the refrain are separated in the first stanza by a single, non-rhyming line. In the subsequent stanzas, the second stanza concludes with the first line of the refrain ("Do not go gentle into that good night"). The third stanza concludes with the second line of the refrain ("Rage, rage against the dying of the light"). The second line in each of these stanzas must rhyme with the second line in the first stanza. This pattern continues until the sixth, final stanza, when two new lines precede the two-line refrain. Only in this final stanza do those famous two lines follow one another, as they customarily are when people quote from the poem. Here's the final stanza of Thomas's famous poem:And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light. It's clear the formal structure of the villanelle puts a lot of weight on those two repeated lines. Given where we are politically in this country in the first months of a new administration, I think Michael Young has met (and exceeded) that challenge in composing his refrain: "It surely won’t be as bad as people say...It’s not like they’ll be marching us away." But the second hurdle, given he role that repetition must play in the poem, is to make those stanzas "go somewhere" beyond simply repeating the initial message. Repetition is a powerful effect -- some popular songs are built on almost nothing but a refrain (often repeated many, many times) -- but shades of emphasis, variation, and fuller meaning can be drawn from the same words as the poem progresses. In the third stanza of Young's poem the poet darkens the implication of the initial stanza by varying the wording of the refrain. You don't say "It's not like they’ll be marching us away" unless you wish to plant that very thought. It's like saying, "I won't mention my divorce." Now you've mentioned it. In the third stanza that "marching away" becomes more explicit: He wouldn’t dare to bundle us like hay,

mark those who wear hijab, open the gates,

rounding them up and marching them away. In the fourth stanza he darkens the implication further by expanding the range of potential victims: "It doesn’t matter if you’re straight or gay./ He can’t determine rights by who one dates...." In the final stanza the reader is advised to "Ignore the knocking. It’s just another day."... Now when the two refrain lines are paired directly, the end-rhymes fall like the closing of a trap: It surely won’t be as bad as people say.

It’s not like they’ll be marching us away. Joel Johnson's poem "Dear Camille" also introduces variations in the wording of the refrains to reveal a truth about the speaker of the poem. In the first stanza we have: Words belong in rows, even plain and clear,

a casual font on an ivory sheet.

I write because I cannot be sincere.

In the fourth stanza, at its second repetition, that first refrain becomes: "Words belong in rows, even cold and clear." We hear that 'cold' and know that the author of this letter to poor Camille is telling us more than he may intend. And in the following stanza, the second line of the refrain has become: "I write because I hate to be sincere." The final stanza makes the situation explicit. It begins "A letter, rewritten, is engineered," a comment that aptly applies to the entire letter-poem. And that second refrains has turned into the coldly revealing: "I write because I loathe to be sincere." To read these poems in their entirety, and many others -- including lots of villanelles offering many different approaches to tailoring this seemingly tight-fitting suit of poetic clothes -- see http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-an....

Published on March 10, 2017 21:52

March 5, 2017

The Garden of Images: History Repeats Itself in Anti-immigrant Hysteria

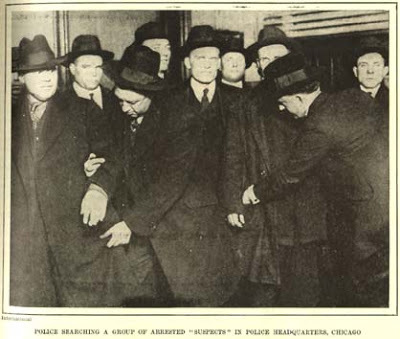

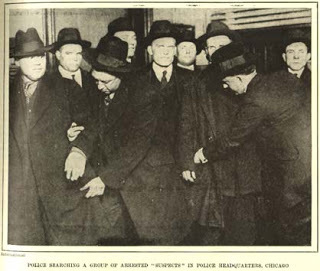

The photo above pictures a moment in the round-up of immigrants in America 100 years ago. The suspicious 'outsiders' are white-skinned people from southern and eastern Europe -- Italians, Jews, Poles, Russians, Greeks, Serbs, Ukrainians, Lithuanians. The mass round-up of immigrants took place during the period of political hysteria of targeting and removing the devils who live and conspire among us known as the Red Scare of 1919-20. Our government was convinced for that two-year period that 'radical' foreigners were plotting a revolution to turn the US into a Communist state such as Soviet Russia.

The second photo is a contemporary image of an ICE officer taking part in a roundup of "undocumented immigrants" today. The victims are likely Latinos or people from the Middle East. It's great to see that American democracy has made such progress over the last century, so that we don't keep making the mistake of blaming our problems on 'outsiders' who don't really belong here. This photo was taken as immigration agents took a handcuffed father away in a black car last Friday (March 3). He was driving his 13-year-old daughter to school when macho, black-clad agents "unleashed" by the liar in the White House seized him. According to KABC-TV in Los Angeles: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents pulled Romulo Avelica-Gonzalez’s vehicle over Tuesday about a half mile from a school where the undocumented immigrant from Mexico had just dropped off one of his daughters.

The second photo is a contemporary image of an ICE officer taking part in a roundup of "undocumented immigrants" today. The victims are likely Latinos or people from the Middle East. It's great to see that American democracy has made such progress over the last century, so that we don't keep making the mistake of blaming our problems on 'outsiders' who don't really belong here. This photo was taken as immigration agents took a handcuffed father away in a black car last Friday (March 3). He was driving his 13-year-old daughter to school when macho, black-clad agents "unleashed" by the liar in the White House seized him. According to KABC-TV in Los Angeles: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents pulled Romulo Avelica-Gonzalez’s vehicle over Tuesday about a half mile from a school where the undocumented immigrant from Mexico had just dropped off one of his daughters.The dad, 48, was driving daughter Fatima Avelica to another school in the northeast Los Angeles neighborhood of Highland Park when ICE stopped them. Left behind in the car with her mother, Fatima wept inconsolably as she captured video of her father’s detention. Rosary beads hung from the rearview mirror. A palm-frond cross rested on the dashboard.

I'm sure we're all feeling safer now that Fatima's father will be detained and deported. A man who works for a living, drives his daughter to school, and decks his car with rosary beads and palms is clearly a threat to America-First.

America First, btw, was an organization that cozied up with Hitler and tried to keep America out of World War II. Of course the current ignoramus occupying the White House knows nothing of history. Neither, unfortunately, do those who voted for him.

Some reality checks.

Immigrants contribute to the American economy and help it grow, rather than taking from it. They do the jobs we don't want. If you want to compete with them for office cleaning, house-cleaning, fruit-picking, McDonald's- serfing jobs they spend long hours on every week to sustain themselves, go ahead. Americans vote for charlatans who promise them 'good jobs,' not the ones that are out there. If more of us were willing to work for minimum wage -- and we're not -- maybe we would all get behind raising it.

Reality check number two. Studies show immigrant are far less likely to commit crimes than native-born citizens. Makes sense. Why would people who have risked everything to come here risk getting sent back to the hell-holes they worked so hard to escape?

Number three. Immigrants pay substantial taxes, paying out to the government more than they receive back. Undocumented immigrants in particular pay more taxes than they receive from public programs because they are not eligible for government services, including major programs such as social security, medicare and food stamps. They do not receive tax refunds because they do not file returns.

Life is hard without documents.That is why many of the undocumented acquire false Social Security cards -- many employers require a Social Security number to hire them. Ironically, using a false number is the "crime" that gives ICE the excuse to arrest and deport them since now they are 'breaking the law' by trying to work and live like the rest of us. Think about this: yes, they arrived her without documents, but now they are trying to play by all the rules.

So, final thought, wouldn't it be easier -- not to mention more humane -- to give them the Social Security card, put them on the books, license them to drive, etc., and harness the abilities and energy they have already demonstrated to help America grow as a prosperous and just society?

Published on March 05, 2017 12:29

February 26, 2017

The Garden of Shame: Are We Ready Yet for James Baldwin?

Photo: Magnolia Pictures

The film has no narrator. At times actor Samuel L. Jackson speaks words that American writer James Baldwin wrote. Sometimes Baldwin is seen on screen speaking on talk shows, at a Cambridge, England debate, or in brief clips from interviews given decades ago.

The film "I Am Not Your Negro" by Raoul Peck is not 'about' the life or work of James Baldwin, his life, his autobiography, his literary oeuvre. It's not a biopic. It's about what he said. What he said about America. Baldwin's words are more relevant, and revelatory, than ever. Reviewer Nicolas Rapold offers the best definition I've seen of this film: a "masterfully eloquent living essay on race and America." The title "I Am Not Your Negro"is something Baldwin said. Meaning, I take it, that neither he, nor any other person of color, of African ancestry, is to be seen from "your" perspective. Which is to say that white people invented the 'negro': that there is no such thing as a 'negro' without a white person to see a black one as the "other." Baldwin -- who was born in Harlem in 1924 and died in 1987 -- sees himself, as the film unquestionably demonstrates, as an "American." The movie asks us -- through the accumulation of images rather than bald statement -- where does all this hate from other Americans, the white ones, for people like Baldwin, come from? Since seeing this film I've been reminding myself of the dirty secret that has come to light so frequently in recent years: That American police shoot, kill, and otherwise mistreat African Americans as they would not dream of treating anyone else. And that America's public officials, its governing establishment, its courts, its mayors, its police chiefs, back them up -- no matter what they do. (With some exceptions, I suppose. But after the cavalcade of visually documented horrors that flash by in "I Am Not Your Negro" it's hard to remember them.) That could be us, could be me, white people think when some pathetic creature in a uniform explains why he had to kill an unarmed black man. A dirty little thing in our conscience offers us the answer: we don't really think these people are human, do we? We are afraid, we think. And we think we are right to be afraid. As another of the film's recent reviewers (Kenneth Turan in the "LA Times") pointed out, the film's message, insofar as it can be reduced, is encapsulated in its first few minutes. No narrative is offered. No titles tell you what you are seeing, or when, or the names of the images on the screen. If you are old enough to recognize the faces, you know that we're seeing footage from the "Dick Cavett Show." A liberal's show. The year (a review tells me) is 1968.

The wave of the "Civil Rights Era," the famous demonstrations, the landmark federal laws, has crested by 1968 and is on the way down, though that may not be obvious at the time. But that's the background, the legal gains of the Civil Rights era, for Cavett's question: “Why aren’t Negroes more optimistic — it’s getting so much better.” As a look of almost horror-movie 'weariness' overtakes his features -- and Baldwin's facial expressions can be as eloquent as his words -- he replies, “It’s not a question of what happens to the Negro. The real question is what is going to happen to this country.” What appears to be happening, we learn from a brief excerpt Baldwin's appearance at another public forum is that white Americans are allowing themselves to become “moral monsters” through unexamined bigotry. We see expressions of hatred, and hateful acts, more intense than we were allowed to see on TV or in film footage back in the sixties. The prospect of a female African American teenager integrating a high school turns white protestors into a mass of seething devils. They look, and behave, like something out of Bosch's medieval depictions of hell. These images are intercut with words from others, from Baldwin, from newscasters, white racists, politicians, exclamations of grief from the loved ones of victims. The film moves very fast, without regard to obvious chronology, narrative line, plot, or expository framework. It offers footage from the Civil Rights era; footage from the Ferguson demonstrations. No one is telling you how, but you know, you feel, how it all fits together. It's the densest hour and a half I can recall experiencing, on film or anywhere else. When you try to use words afterwards to explain its effect, you come up with something like this: Black Americans are not a faction, a racial group, or a census demographic, and they're certainly not a monolithic 'community.' They are Americans. You can't separate them out; they don't exist anywhere but here. And America is not America apart from them. And yet, white Americans can't seem to accept who we are as Americans. And that failure is killing us.

The film has no narrator. At times actor Samuel L. Jackson speaks words that American writer James Baldwin wrote. Sometimes Baldwin is seen on screen speaking on talk shows, at a Cambridge, England debate, or in brief clips from interviews given decades ago.

The film "I Am Not Your Negro" by Raoul Peck is not 'about' the life or work of James Baldwin, his life, his autobiography, his literary oeuvre. It's not a biopic. It's about what he said. What he said about America. Baldwin's words are more relevant, and revelatory, than ever. Reviewer Nicolas Rapold offers the best definition I've seen of this film: a "masterfully eloquent living essay on race and America." The title "I Am Not Your Negro"is something Baldwin said. Meaning, I take it, that neither he, nor any other person of color, of African ancestry, is to be seen from "your" perspective. Which is to say that white people invented the 'negro': that there is no such thing as a 'negro' without a white person to see a black one as the "other." Baldwin -- who was born in Harlem in 1924 and died in 1987 -- sees himself, as the film unquestionably demonstrates, as an "American." The movie asks us -- through the accumulation of images rather than bald statement -- where does all this hate from other Americans, the white ones, for people like Baldwin, come from? Since seeing this film I've been reminding myself of the dirty secret that has come to light so frequently in recent years: That American police shoot, kill, and otherwise mistreat African Americans as they would not dream of treating anyone else. And that America's public officials, its governing establishment, its courts, its mayors, its police chiefs, back them up -- no matter what they do. (With some exceptions, I suppose. But after the cavalcade of visually documented horrors that flash by in "I Am Not Your Negro" it's hard to remember them.) That could be us, could be me, white people think when some pathetic creature in a uniform explains why he had to kill an unarmed black man. A dirty little thing in our conscience offers us the answer: we don't really think these people are human, do we? We are afraid, we think. And we think we are right to be afraid. As another of the film's recent reviewers (Kenneth Turan in the "LA Times") pointed out, the film's message, insofar as it can be reduced, is encapsulated in its first few minutes. No narrative is offered. No titles tell you what you are seeing, or when, or the names of the images on the screen. If you are old enough to recognize the faces, you know that we're seeing footage from the "Dick Cavett Show." A liberal's show. The year (a review tells me) is 1968.

The wave of the "Civil Rights Era," the famous demonstrations, the landmark federal laws, has crested by 1968 and is on the way down, though that may not be obvious at the time. But that's the background, the legal gains of the Civil Rights era, for Cavett's question: “Why aren’t Negroes more optimistic — it’s getting so much better.” As a look of almost horror-movie 'weariness' overtakes his features -- and Baldwin's facial expressions can be as eloquent as his words -- he replies, “It’s not a question of what happens to the Negro. The real question is what is going to happen to this country.” What appears to be happening, we learn from a brief excerpt Baldwin's appearance at another public forum is that white Americans are allowing themselves to become “moral monsters” through unexamined bigotry. We see expressions of hatred, and hateful acts, more intense than we were allowed to see on TV or in film footage back in the sixties. The prospect of a female African American teenager integrating a high school turns white protestors into a mass of seething devils. They look, and behave, like something out of Bosch's medieval depictions of hell. These images are intercut with words from others, from Baldwin, from newscasters, white racists, politicians, exclamations of grief from the loved ones of victims. The film moves very fast, without regard to obvious chronology, narrative line, plot, or expository framework. It offers footage from the Civil Rights era; footage from the Ferguson demonstrations. No one is telling you how, but you know, you feel, how it all fits together. It's the densest hour and a half I can recall experiencing, on film or anywhere else. When you try to use words afterwards to explain its effect, you come up with something like this: Black Americans are not a faction, a racial group, or a census demographic, and they're certainly not a monolithic 'community.' They are Americans. You can't separate them out; they don't exist anywhere but here. And America is not America apart from them. And yet, white Americans can't seem to accept who we are as Americans. And that failure is killing us.

Published on February 26, 2017 11:22

February 21, 2017

One Hundred Years Ago: Flowers Planted in the Garden of Hate

At a time when Presidential orders seek to close doors on refugees and ban travelers from Muslim-majority countries, the infamous Sacco-Vanzetti case of a century ago illustrates the extremes anti-immigrant hysteria can reach in American politics.

At a time when Presidential orders seek to close doors on refugees and ban travelers from Muslim-majority countries, the infamous Sacco-Vanzetti case of a century ago illustrates the extremes anti-immigrant hysteria can reach in American politics.

I'll be speaking on my novel drawn from the Sacco-Vanzetti case, "Suosso's Lane," and reading from the book, at the Dedham Historical Society, 612 High St., on Thursday, Feb. 23, 7:30 p.m. I'll bring paperback copies for sale and signing.

I'll be speaking on my novel drawn from the Sacco-Vanzetti case, "Suosso's Lane," and reading from the book, at the Dedham Historical Society, 612 High St., on Thursday, Feb. 23, 7:30 p.m. I'll bring paperback copies for sale and signing."Suosso's Lane," dramatizes immigrant life in the early 20th century and traces the role the 1920 political panic over 'dangerous, radical' foreigners -- known as the Red Scare -- played in condemning two Italian immigrants to death.

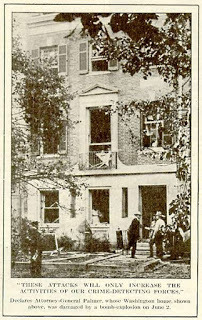

I believe there are lessons for our own time from the notorious Sacco-Vanzetti case. Especially now, a few weeks into a new administration, when the reins of power are in the hands of a president whose stated goals appear to signal a decline of democratic and egalitarian values, much like the period in which Sacco and Vanzetti were executed because of their beliefs and their ethnicity. American democracy has seen dangerous times before -- anti-democratic and surely anti-egalitarian national moods -- and it has recovered. But judging from the past, the potential for abuse is strongly present at such times. On top of a growing nativist resentment of new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe -- and a particular prejudice against Italians -- two major events transformed the nation's political climate in 1917: The United States entered World War I; and the Russian Revolution created a Communist regime hostile to America's capitalist economic system. Communist parties elsewhere predicted that Russia's radical transformation was the forerunner of a world-wide revolution, making other governments, including our own, nervous. America's entry into World War I led to a military draft. Reacting -- and over-reacting -- to anti-war opposition from the country's radical left-wing, Congress passed laws that criminalized political dissent, making criticism of the draft and the decision to fight the war illegal. (Compare this to the Vietnam period!) These stress points compounded growing fractures in American society because opposition to these wartime policies was strongest among the radical worker movements led by Socialists and Anarchists, many of whom were foreign nationals. Declaring that 'opposition' meant 'subversion,' the federal government created the first true national police (or spy) service, the FBI, to harass and prosecute war opponents such as the prominent Italian anarchist Luigi Galleani, founder of the Italian language newspaper Cronaca Sovversiva. Its subscribers included Nicolo Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. With more prejudice and ideology than cause, an exaggerated fear of violent revolution led U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer to obtain thousands of warrants to arrest radicals, search their premises, confiscate literature, and destroy presses. Influenced by the nation's jingoistic war mood and the dire prophecies of his own new security apparatus, Palmer and others demonized socialist and anarchist opposition to the war. Palmer stated: "The Red Movement" -- a extremist term du jour -- "is not a righteous or honest protest against alleged defects in our present political and economic organization of society… It is a distinctly criminal and dishonest movement in the desire to obtain possession of other people’s property by violence and robbery.” This was complete nonsense, but scare talk from high officials has its impact. Each 'Red' radical (according to Palmer) was therefore “a potential thief.”(25) If you believed that, and you found yourself on a jury, it was easy to believe that anarchists were likely to rob factory payrolls. In fact they were not. Some anarchists at this time chose violence. But when anarchists go to war against a government, they do not rob payrolls, or steal; what they do is plant bombs or otherwise attempt to assassinate leaders of the status quo. (Some acts of political violence are, of course, the work of lone nuts.) Denied legitimate means of protest, their press shut down, their subscription list confiscated, their freedom of speech, press and assembly criminalized, some hard-line supporters of Luigi Galleani -- who was tried and deported for opposing the draft -- turned to the only means they believed available to them: bombs. Bombs were mailed to government and big business targets in April of 1919; and hand-delivered to the homes and offices in June. One of the latter explosives destroyed half of Palmer's house, though no one there was hurt. These events were the immediate backdrop for the increased repressions of the "Red Scare." Palmer launched two series of raids, in November of 1919 and January of 1920. His agents arrested thousands of 'aliens' without warrants, holding many for deportation often in horrendous conditions and without due process of law. Ultimately, only 446 were actually deported (by administrative hearing), before the courts intervened and a reaction against abuses of executive power took place. But fourteen raids on leftists took place in Massachusetts, and in Boston five hundred aliens were marched through the streets in chains and taken to the Deer Island House of Correction, where they were isolated "in brutally chaotic conditions,” according to later government reports. It was against this backdrop that Sacco and Vanzetti -- two names federal agents knew from the subscription list to Galleani's anarchist newspaper "Cronaca Sovversiva" -- were charged with the robbery of a Braintree shoe factory payroll and the killing of two payroll officers despite any direct evidence, and convicted by a native-born Massachusetts jury that believed all foreign anarchists should be 'strung up,' according to the jury foreman. A time of "us" and "them." The Sacco-Vanzetti case appears to shine a light on the darker side of American society's historical treatment of immigrants of 'unfamiliar' ethnicities. Periodically -- especially in those periods when a 'new' group of foreign nationals arrives in large numbers -- the so-called 'nation of immigrants' has exhibited a desire to close doors and build walls. Forgetful of their own non-native origins, many Americans are quick to close the borders on the next group of newcomers, whose language or manners, or religion, or skin tone, or potential for economic competition, or imagined demand for public services, appears to threaten the well-being of those already comfortably settled in the United States. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, it was the turn of Italians to be the most numerous and visible of these presumed-to-be-problematic newcomers. The executions of Sacco and Vanzetti were a direct consequence -- and an international symbol -- of that fear of "the others."

I believe there are lessons for our own time from the notorious Sacco-Vanzetti case. Especially now, a few weeks into a new administration, when the reins of power are in the hands of a president whose stated goals appear to signal a decline of democratic and egalitarian values, much like the period in which Sacco and Vanzetti were executed because of their beliefs and their ethnicity. American democracy has seen dangerous times before -- anti-democratic and surely anti-egalitarian national moods -- and it has recovered. But judging from the past, the potential for abuse is strongly present at such times. On top of a growing nativist resentment of new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe -- and a particular prejudice against Italians -- two major events transformed the nation's political climate in 1917: The United States entered World War I; and the Russian Revolution created a Communist regime hostile to America's capitalist economic system. Communist parties elsewhere predicted that Russia's radical transformation was the forerunner of a world-wide revolution, making other governments, including our own, nervous. America's entry into World War I led to a military draft. Reacting -- and over-reacting -- to anti-war opposition from the country's radical left-wing, Congress passed laws that criminalized political dissent, making criticism of the draft and the decision to fight the war illegal. (Compare this to the Vietnam period!) These stress points compounded growing fractures in American society because opposition to these wartime policies was strongest among the radical worker movements led by Socialists and Anarchists, many of whom were foreign nationals. Declaring that 'opposition' meant 'subversion,' the federal government created the first true national police (or spy) service, the FBI, to harass and prosecute war opponents such as the prominent Italian anarchist Luigi Galleani, founder of the Italian language newspaper Cronaca Sovversiva. Its subscribers included Nicolo Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. With more prejudice and ideology than cause, an exaggerated fear of violent revolution led U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer to obtain thousands of warrants to arrest radicals, search their premises, confiscate literature, and destroy presses. Influenced by the nation's jingoistic war mood and the dire prophecies of his own new security apparatus, Palmer and others demonized socialist and anarchist opposition to the war. Palmer stated: "The Red Movement" -- a extremist term du jour -- "is not a righteous or honest protest against alleged defects in our present political and economic organization of society… It is a distinctly criminal and dishonest movement in the desire to obtain possession of other people’s property by violence and robbery.” This was complete nonsense, but scare talk from high officials has its impact. Each 'Red' radical (according to Palmer) was therefore “a potential thief.”(25) If you believed that, and you found yourself on a jury, it was easy to believe that anarchists were likely to rob factory payrolls. In fact they were not. Some anarchists at this time chose violence. But when anarchists go to war against a government, they do not rob payrolls, or steal; what they do is plant bombs or otherwise attempt to assassinate leaders of the status quo. (Some acts of political violence are, of course, the work of lone nuts.) Denied legitimate means of protest, their press shut down, their subscription list confiscated, their freedom of speech, press and assembly criminalized, some hard-line supporters of Luigi Galleani -- who was tried and deported for opposing the draft -- turned to the only means they believed available to them: bombs. Bombs were mailed to government and big business targets in April of 1919; and hand-delivered to the homes and offices in June. One of the latter explosives destroyed half of Palmer's house, though no one there was hurt. These events were the immediate backdrop for the increased repressions of the "Red Scare." Palmer launched two series of raids, in November of 1919 and January of 1920. His agents arrested thousands of 'aliens' without warrants, holding many for deportation often in horrendous conditions and without due process of law. Ultimately, only 446 were actually deported (by administrative hearing), before the courts intervened and a reaction against abuses of executive power took place. But fourteen raids on leftists took place in Massachusetts, and in Boston five hundred aliens were marched through the streets in chains and taken to the Deer Island House of Correction, where they were isolated "in brutally chaotic conditions,” according to later government reports. It was against this backdrop that Sacco and Vanzetti -- two names federal agents knew from the subscription list to Galleani's anarchist newspaper "Cronaca Sovversiva" -- were charged with the robbery of a Braintree shoe factory payroll and the killing of two payroll officers despite any direct evidence, and convicted by a native-born Massachusetts jury that believed all foreign anarchists should be 'strung up,' according to the jury foreman. A time of "us" and "them." The Sacco-Vanzetti case appears to shine a light on the darker side of American society's historical treatment of immigrants of 'unfamiliar' ethnicities. Periodically -- especially in those periods when a 'new' group of foreign nationals arrives in large numbers -- the so-called 'nation of immigrants' has exhibited a desire to close doors and build walls. Forgetful of their own non-native origins, many Americans are quick to close the borders on the next group of newcomers, whose language or manners, or religion, or skin tone, or potential for economic competition, or imagined demand for public services, appears to threaten the well-being of those already comfortably settled in the United States. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, it was the turn of Italians to be the most numerous and visible of these presumed-to-be-problematic newcomers. The executions of Sacco and Vanzetti were a direct consequence -- and an international symbol -- of that fear of "the others."

Published on February 21, 2017 21:56

February 14, 2017

The Garden of Verse: A Quiet But Unforgettable Poem About 'Winter Sundays'

A monthly column written by poet David Graham for Verse-Virtual, the online poetry journal to which I contribute each month, continues to contribute to my education. The column is called "Poetic License." This month David writes about one of his favorite poets, Robert Hayden, and shares some great poems including, to quote from the column, this "rather understated, rueful lyric about [his father], 'Those Winter Sundays,' which if not my favorite poem of all time, is certainly in my top five":

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

I'd wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he'd call,

and slowly I would rise and dress,

fearing the chronic angers of that house,

Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

of love's austere and lonely offices?

To read the rest of David Graham's column, see Verse-Virtual at:

http://www.verse-virtual.com/david-gr...

I have four new poems in the February issue, including one based on a photo of a Great Blue Heron by fellow poet Jim Lewis. Jim posted his photo on Facebook and challenged other poets who write for Verse-Virtual.com to write a poem inspired by looking this bird in the eye. My response to the challenge begins…

Courage of the Wind

(based on Jim Lewis’s photo of the Great Blue Heron)

You see me, as always, before I see you

You turn on a corner of the wind

where the air meets sky and the scent

of salt marsh bathes the hours

I know you by the killer eye in your bone arrow,

your linear head-piece head-on to the future

that houses both sense and brain, and the rapier jaw,

the needle of thought sewn through sky and brine,

the silvery flesh of life in the quick

and the ocular penetration,

right-angled from your dagger stab

… to read the rest of this poem and all the others in the February 2017 issue of Verse-Virtual.com, see http://www.verse-virtual.com/poems-and-articles.html

Published on February 14, 2017 20:58

February 8, 2017

Nation of Shame: Shutting Down Speech on the Senate Floor

The once was a piece of Old Diggery Who handed out lessons in piggeryHe stood up on a box his oaf song to sing Quashing a letter from Coretta Scott KingAnd birthed a whole nation of triggery

What's next? A caning on the Senate floor? In the years before the Civil War the attack on Massachusetts Senator Charlies Sumner by a racist Congressman from South Carolina drove an irreparable wedge between two parts of the country, as the North learned that the slave owners on the other side lacked all decent respect for human life. (For the whole story see Massachusetts author Stephen Puleo's book, "The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War," for the details. Here's the link for that book: http://www.stephenpuleo.com/book/the-...)

What's next? A caning on the Senate floor? In the years before the Civil War the attack on Massachusetts Senator Charlies Sumner by a racist Congressman from South Carolina drove an irreparable wedge between two parts of the country, as the North learned that the slave owners on the other side lacked all decent respect for human life. (For the whole story see Massachusetts author Stephen Puleo's book, "The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War," for the details. Here's the link for that book: http://www.stephenpuleo.com/book/the-...)These reflections are prompted by the Senate majority's attack on the freedom of speech of Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren, who opposes the nomination of Jeff Sessions for Attorney General. Jeff Sessions is a racist. His history is on the record; it's no secret. When he sought to prosecute Civil Rights activists, back in Alabama where the government did that sort of thing routinely, he attacked a white lawyer defending the activists by calling him "a traitor to your race."

I don't know about anybody else, but I don't want to be part of any "race" that Jeff Sessions is a member of.

Race is a fiction, a lie. There is no scientific basis for dividing human beings into races. There is only one human race. We are all in it. Unfortunately, some of our members are throwback degenerates, like Jeff Sessions.

Sessions, and every Republican senator who supports him, plus the despicable administration that proposed him (which appears to be government by White Supremacist Loose Cannon Bannon) are trying to drive America back to the pre-Civil Rights era when it's OK to slander members of "other" non-white groups whenever the need arises -- Muslims are terrorists; African-Americans are cop killers -- but illegal to point out that craven politicians appeal to white Americans' baser instincts by using racial slurs. That is, it's OK to be a racist, but it's not OK to call a white American a racist.

What Warren was doing when the Senate gagged her last night was reading a letter from Coretta Scott King, generally regarded as reliable source on civil rights, opposing Sessions's nomination for a federal judgeship back in 1986 on the grounds of his blatant, repeated opposition to Civil Rights after desegregation became the law of the land. Back then, the Senate defeated his nomination.

King's letter is straight-forward, but the language is civil. Her letter states: "Mr. Sessions has used the awesome power of his office to chill the free exercise of the vote by black citizens in the district he now seeks to serve as a federal judge.”

This is a factual claim.

Somehow Senate Republicans alleged it was an attack on one of their members -- Alabama voters having chosen to vote the racist Jeff Sessions to the US Senate -- that violated some kind of rule about saying not-nice things about one of their members.

Brain-dead Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell ruled she could no longer speak on the nomination and was supported by his ignorant clones.

Folks, we are increasingly two countries. I don't wish to be part of any country that allows Jeff Sessions, or McConnell, or the p.o.s. in the White House to govern us. (I expect the antipathy is returned.)

Published on February 08, 2017 09:00

February 6, 2017

The Garden of Verse: The Greatest Political Poem, Shelley's "The Mask of Anarchy"

On August 16, 1819, a public meeting of England's vast new industrial working class, then seeking more representation in Parliament -- and, perhaps, the vote for a few members of their own class -- that drew about 60,000 men, women and children to a site near Manchester was violently broken up by an attack of armed soldiers on horseback.

On August 16, 1819, a public meeting of England's vast new industrial working class, then seeking more representation in Parliament -- and, perhaps, the vote for a few members of their own class -- that drew about 60,000 men, women and children to a site near Manchester was violently broken up by an attack of armed soldiers on horseback. A sword-blow and trampling massacre of participants took a disputed number of lives -- the official total 11, the unofficial five times higher -- including a little girl trampled to death. Living in Italy, driven from England for his radical views -- chief among them being his atheism, a punishable crime under English law -- the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley received the news by mail, "and the torrent of my indignation has not yet done boiling in my veins," he wrote to his publisher in London. (My source for quotes and background information is "Shelley: The Pursuit" by Richard Holmes.) There was nothing liberal, democratic, civil libertarian or progressive about the government of England 200 years ago. Thirty years into its current Constitutional government and still adhering (as least as of the moment in 2017) to the protections of its hallowed First Amendment freedoms, the United States did not prosecute aetheists or make a habit of breaking up public meetings by government critics. American democracy was far from complete: only property-owning white males could vote, and half the country premitted slavery. But this country lacked a monarch or a social class system that enshrined certain people on the basis of birth alone with important rights and powers not shared by others. I can't really make a case for a connection between the situation faced by powerless working people in the early decades of the industrial revolution and the current political crisis in the United States brought on by the election of a "so-called president" who manages to meld everything that is wrong with our society, and much that always has been (such as racism), into one bloated, arrogant, narcissistic, ignorant personage... .... except to express my admiration over a great poet's ability to turn his "torrent of indignation" in great art. Nevertheless see this excerpt from Chris Hedges' recent discussion of the "moral monsters" of our own day: "Bannon and his followers on the 'alt-right,' self-declared intellectuals, ferret out facts and formulas that buttress their peculiar worldview and discard truths that contradict their messianic delusions. They mouth a few clichés and quote a few philosophers to justify bigotry, chauvinism and governmental repression. It is propaganda masquerading as ideology. These pseudo-intellectuals are singularly incurious. They are linguistically, culturally and historically illiterate about the Muslim world, and about most other foreign cultures, yet blithely write off one-fifth of the world’s population—Muslims—as irredeemable. ...The inability of white supremacists like Trump and Bannon to recognize the humanity of others springs from their spiritual impoverishment. They mistake bigotry for honesty and ignorance for innocence. They cannot separate fantasy from reality. Such people are, as author James Baldwin said, 'moral monsters.'"

Shelley knew about moral monsters too. The poet's response to the massacre, which took place at a site called St. Peter's Field (shortened by the vernacular to Peterloo), was the poem his impeccably informed biographer Richard Holmes calls "the greatest poem of political protest ever written in English." It's centered, Holmes writes, on "the most important single image Shelley took from the newspapers... that of the unarmed mother, whose child was trampled to death as the Yeomanry first charged." Many of Shelley's long poems, in a short life, are ambitious works based on classical mythological themes, such as "Prometheus Unbound," that presuppose the classical education of someone from his own upper-class background, or at least enough familiarity with 'great books' to recognize the names in their titles. In "Anarchy" nothing of the sort. Again, from Holmes: "He found himself writing immediately in the colloquial ballad stanzas he had not used since 1812.... The lines were terse, flexible, rapid, based on the simple four-stress verse of the broadsheets, sometimes end-stopping, sometimes running on unchecked for a whole stanza, using a bewildering variety of full rhymes, half rhymes, assonance, the curous minor-key of half-assonance, and sudden bursts of burtal, merciless alliteration. ... the reader has the sense of a mass of unconsciously prepared material leaping forward into a unity at a single demand." An armed minion of the state trampling a child in a heartless, indifferent assault on a mass protest for social justice symbolized for Shelley the evil of a system that financed the idle life of the rich by an oppressed class who lacked rights and power -- and sometimes enough to eat. He turns the facts on the ground into a poem that mimics the style and apparatus of a medieval allegory. The "Mask" -- a word also rendered as 'masque' and 'masquerade' -- was a theatrical entertainment in which costumes and facial masks suggested mythical characters, moral states, or other generalities of the human condition. At the Elizabeth and Stuart courts, for instance, the "masques" were the presentations of a court officer known as "master of the revels." Shelley's heavily moralistic figures (in the stanzas below), such as Murder and Fraud, suggest characters in Medieval Morality Plays, in which Vice and Virtue and Everyman, among others, frequently appeared. The proper names in the poem's opening stanzas (Castlereagh, Eldon) are chief ministers in the English "government" who approved the militia's behavior and arrested various protest leaders on charges of sedition. Also, for the record, the word "anarchy" here means a brutal chaos of unleashed passions. Shelley's classically based use of the term has nothing to do with the political philosophy called "anarchism," a product of the latter 19th century which argued for the dissolution of government as the answer to the injustices of power. In Shelley's poem "anarchy" is unleashed by power on the the powerless. The poem begins with an imagined poetic journey: I met Murder on the way--He had a mask like Castlereagh--Very smooth he looked, yet grim;Seven blood-hounds followed him: All were fat; and well they mightBe in admirable plight, For one by one, and two by two,He tossed them human hearts to chew Which from his wide cloak he drew.Next came Fraud, and he had on,Like Eldon, an ermined gown;His big tears, for he wept well,Turned to mill-stones as they fell. And the little children, whoRound his feet played to and fro,Thinking every tear a gem, Had their brains knocked out by them.

The clear implication is the English government has no regard for the little children, or any other human beings of the lower classes, who have their "brains knocked out" by a tyrannical government's callous acts and systematic repressions.

The "Mask of Anarchy" has 91 stanzas. In its last third, Shelley outlines, still in ballad-style metrical and rhymed verse, the path of massive nonviolent resistance to immoral authority that would in a later century be practiced by Gandhi in India and by the civil rights movement in the United States. Just face your armed oppressors bravely, the poet appears to say, and do not fight back. The movement created by this brave stance will grow and eventually succeed because a regime -- of any sort -- that uses force on nonviolent resistors eventually loses the support of its people. I would point out here the likelihood that some nonviolent resistors will lose their lives. Shelley's poem anticipated a violent response as well: With folded arms and steady eyes,

And little fear, and less surprise,Look upon them as they slayTill their rage has died away.

What will happen as a result, he says, is those who participate in killing unarmed protestors will be shunned by the rest of society. Every woman in the landWill point at them as they stand--They will hardly dare to greetTheir acquaintance in the street.

And ultimately the resistance of the oppressed to injustice will succeed. So Shelley in a final, brilliantly triumphant stanza concludes:

Rise like Lions after slumberIn unvanquishable number--Shake your chains to earth like dew 370Which in sleep had fallen on you--Ye are many -- they are few.

You win because the numbers are on your side. This was surely the case in India. It was the case in Iran, a country Americans tend to ignore given that its current government is no bargain, when demonstrators by the millions overthrew the Shah because his army would not fire on its own people. In India, of course, protestors were massacred at the Amritsar memorial in 1919. Yet Gandhi's movement (which, as I have just read, acknowledged the inspiration of this poem) ultimately succeeded in liberating his country from British rule. Civil Rights protestors were also beaten by white racists during the Civil Rights demonstrations (and some killed), not only in the South, but in places like Chicago, and also in Boston when black people faced racist taunts during the Boston school desegregation crisis. But the Civil Rights movement succeeded in changing the country, even if racism has clearly not disappeared from American society. What feels important about the example of "The Mask of Anarchy" to me -- in the present moment -- is that instances of extreme social injustice drive great poets (at least the best of them) mad with outrage. They are conductors of suffering. Outrageous abuses of authority such as the Peterloo massacre are lost to history after a century or two. Shelley's masterpiece of poetic response was lost to history for decades because nobody would publish it in 1819. No one had the courage to publish it then because the English government repressed dissent by prosecuting and jailing publishers, editors and authors responsible for printing criticisms of its policies, laws, and institutional injustices. In fairness, Shelley did not return to England to publish it under his own name and, probably, go to jail. He had left England, in part, to avoid that fate. While textbooks and university courses will routinely state that Shelley is regarded as one of England's "great" romantic poets, nobody much knows what he wrote beyond a few widely collected poems: "Ozymandias," with its useful moral that "fame is fleeting: "Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair." Or the Skylark, a short elegant lyric. Or, maybe, if they took college course that included it, "Ode to the West Wind," a middle-length poem which reads and feels like that breath of fresh air the poem promises will arrive. Most of us have heard its famous line: "If winter is here, can spring be far behind?" But most of his greater, more ambitious works were written to challenge the fundamental injustices of his own society. The genius of poetic response to injustice is a powerful weapon for resisting tyranny and oppression. We can find inspiration in the act of opening our souls and imaginations to the great prophetic works of the past.

Published on February 06, 2017 13:28