Michelle Cox's Blog, page 33

April 6, 2017

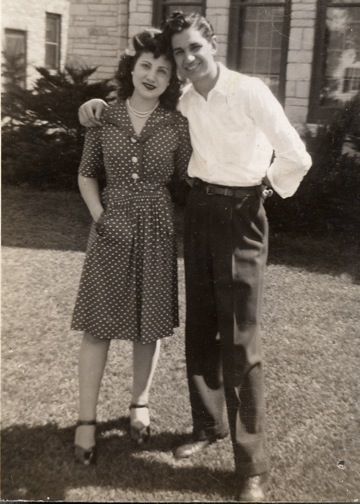

He Asked His Family to Find Him a Bride

Francisco Alvarez was born on September 8, 1913 in Cuba to Felipe Alvarez and Maria Acosta. Felipe worked as a chef in Havana, and Maria cared for their nine children, of whom Francisco was the oldest.

Francisco Alvarez was born on September 8, 1913 in Cuba to Felipe Alvarez and Maria Acosta. Felipe worked as a chef in Havana, and Maria cared for their nine children, of whom Francisco was the oldest.

Francisco was an extremely intelligent child and was able to attend a couple of years of high school before he was forced to quit and help his father in the kitchens of the restaurants where he worked. It wasn’t a job Francisco particularly enjoyed, but he did love good food. As a young man, he also loved playing the saxophone and listening to classical music. “He was very much a loner,” however, reports his sister, Eldora. He was always “hot-tempered,” she says, and “he didn’t have many friends.” He worked a variety of jobs in Cuba, mostly in restaurants, before deciding to try his luck in the United States.

Francisco arrived in Chicago in 1956 and got a job working for Hart, Schaffner and Marx in one of their downtown warehouses. He continued to be a loner, however, and over the years only managed to make two friends with whom he sometimes met up to play dominoes. When he wasn’t working, he took some trips around the United States, and especially liked going to see New York. Eldora says the family was always urging him to settle down and get married, but Francisco always ignored them, saying that there was plenty of time to get “tied down.” They were hopeful, Eldora says, that when he left to come to the United States, he would perhaps find someone there.

After three years in the United States, however, and at age forty-six, he was still single. His family was surprised, then, to get a letter from him one day in which he expressed his desire for them to find him a bride. This of course caused much excitement in the family, as they set about looking for a potential mate for Francisco. Finally, they were able to set him up with Bonita Delgado, who was the daughter of a friend with whom Felipe worked. Francisco returned to Cuba for a visit and to meet his potential wife. He went on several dates with Bonita and, finding her agreeable, promptly proposed to her.

His family was surprised but delighted when she said yes. The two were married quickly in Cuba and then returned to Chicago. Bonita found work in a factory, and Francisco continued at Hart, Schaffner and Marx. It proved not to be a happy marriage, however. Francisco was still hot tempered and was apparently verbally abusive to Bonita, so after only a couple of years, the marriage broke up and Bonita returned to Havana.

Shortly after his divorce, Francisco’s parents, Felipe and Maria, decided to immigrate to the United States, as well, and came to Chicago to be near Francisco and two of their daughters, Eldora and Flores, who had also moved here. It was Felipe’s plan to get a job in a restaurant, but he died unexpectedly after only being in Chicago for about a month. After Felipe’s death, Maria moved in with Francisco and became completely devoted to him. Endlessly she urged him to find another wife, so he continued to date various women, if only to please her.

According to Eldora, Francisco loved to buy women expensive gifts, but he hated being thanked for them. As soon as a woman gushed her thanks to him for a gift he had bought, he “dropped her immediately,” Eldora says. He would then become acerbic and abusive, and the relationship would end. Meanwhile, his mother continued to pamper him and cooked beautiful, elaborate dinners for him until she died at age 97 in 1989.

Francisco was devastated by his mother’s death and repeatedly expressed his desire to “kill himself” and that he wanted “to die.” Eldora and Flores both suspect that he may have actually tried to kill himself at one point but that the attempt wasn’t successful.

To make matters worse, within a couple of years of his mother dying, his only two friends also died. From that point on, Francisco started having health problems and described his legs as suddenly “crippling up.” He began having difficulty walking, so his sisters took him to Miami, “where the climate is better,” and helped him move into a nursing home there. “It was a nice one,” Eldora says, “right on the beach.” Francisco hated the food at that particular facility, however, and soon switched to a different one. Eventually his legs improved, and he returned to Chicago for a visit in 1995 and was able to walk with just the aid of a cane. When he returned to Miami, however, he unfortunately slipped and fell and was then confined to a wheelchair.

After his fall, Eldora and Flores rarely heard from their brother, and they became more and more worried about him. They had been in the habit of talking on the phone with him once a week, but even that ceased. Finally, they decided to go down and visit him. They were shocked when they discovered he was now “drugged” and on a “locked ward.” They protested to the administration and the nurses, who all said that Francisco was violent, abusive and out-of-control. Both Eldora and Flores, who “don’t believe in doctors” insist that their brother is “not crazy, he just has a bad temper.”

They promptly removed him from the nursing home in Miami and admitted him to a different nursing home on Chicago’s NW side, close to where they live. Francisco is not adjusting well here, either, and is verbally abusive to the staff as well as other residents. Eldora and Flores come to visit him regularly and do not seem affected by his verbal abuse, which they dish back to him, suggesting that this behavior was “normal” in their family. Eldora provided all of the above information, as Francisco refuses to answer any questions posed to him by the staff. He is able to speak and understand English, but he usually refuses to do so. Eldora reports that he is confused, thinking he is still in Miami and that he has his days and nights mixed up. She and Flores want him to be happy here, but they do not have much hope, as he has always been such a negative person.

(Originally written September 1996)

The post He Asked His Family to Find Him a Bride appeared first on Michelle Cox.

March 30, 2017

The “Poison Powder”

Dariya Zelenko was born on September 1, 1914 in a small village in the Ukraine. Not much is known about her early life except that her maiden name was Dariya Kozel and that her parents were farmers. She apparently did not have any siblings and received little to no formal education at all, instead helping her parents on the farm as she grew up.

Dariya Zelenko was born on September 1, 1914 in a small village in the Ukraine. Not much is known about her early life except that her maiden name was Dariya Kozel and that her parents were farmers. She apparently did not have any siblings and received little to no formal education at all, instead helping her parents on the farm as she grew up.

When World War II broke out, the family was rounded up by the Germans and taken to a labor camp in Germany. At the camp, Dariya was somehow separated from her parents and tragically never saw them again. She was put to work on a remote farm and there met another prisoner, Kliment Sewick, with whom she eventually fell in love and “married,” though whether it was really official or not is unknown. Dariya had a baby, Simon, but shortly after his birth, Kliment was shot and killed by the Germans. Dariya was never sure why. Dariya grieved for Kliment, but later met another man on the farm, Martin Zelenko, and married him. Martin had befriended the German guards and was able to considerably lighten Dariya’s workload. He was also able to get them some extra food from time to time.

After the war was over, Martin immediately applied to come to America, and, finally, in 1951, he and Dariya and Simon arrived in Chicago looking for work. Martin found a job as a machine operator in a factory, and Dariya worked in a laundromat. Simon says that his mother had no hobbies besides gardening. She did not make any friends and did not ever really like to leave the house. She was very much a loner her whole life, Simon reports, and spent her time obsessively cleaning the house, sometimes scrubbing the floor three times a day. Simon believes this was the only thing his mother had that made her feel happy or worthwhile. Often she would say, “I never went to school, but I’m not stupid!” She was anxious, he says, unless she was working or constantly doing something and was perpetually trying to prove her worth through work.

Apparently, Dariya and Martin were never very close and argued frequently. Martin would often want her to go out with him, even just for a picnic on Sundays, but Dariya would always refuse, saying that she had too much work to do. Simon thinks that the reality was that she had an actual fear of leaving the house. She refused to even go to church, though she would get angry at Simon if he didn’t go every Sunday.

Finally, in 1974, Martin left Dariya and filed for a divorce. Simon had long since moved out and gotten married and says that the divorce didn’t really seem to faze his mother. He says that while his stepfather had his faults, he could see that as the years went on, Dariya became more and more unreasonable and withdrawn and that his stepfather had finally had enough of it.

After the divorce, Dariya remained alone, content to stay at home, cleaning and gardening. Things continued this way until 1991, when Dariya fell and broke a bone in her spine and had to go live with Simon. It was at this point that she began to rapidly decline mentally. Simon says that his mother then became extremely paranoid and began accusing him of trying to poison her. She would scream constantly at the top of her lungs, saying that Simon was putting poison in her food and throwing “poison powder” on her. She developed a persistent itch and subsequently took to hiding her clothes so that Simon wouldn’t throw poison powder on them.

Wanting to help and reassure her, Simon installed a lock on her bedroom door on the inside, so that she could lock herself in and feel secure. It didn’t work, however, as she then accused him of spraying the powder under the door. No matter what Simon did to try to alleviate his mother’s fears, it seemed to backfire.

Even when he was at work, Dariya thwarted him by going out into the yard and screaming at the neighbors, accusing them of also trying to poison her. She would shout that she knew that Simon was paying them to do it and would then throw mud on their windows. Dariya even chased her own grandson out of the house once because she was convinced he was part of the “plot” as well. This continued for three more years until Dariya fell and broke another bone, this time her leg. At that point, Simon decided it was a good opportunity to place her in a nursing home.

Simon feels guilty about putting his mother in a nursing home and stops by every night after work to check on her, but he is relieved as well, as it was just too difficult having her home. For her part, Dariya is not making a smooth transition. She seems not able to speak in a normal tone of voice and is instead always screeching and screaming at both the staff and the other residents, frequently shouting “shit!” as loud as she can. This disrupts the other residents, who in turn usually start shouting back at her or simply leave the current house activity to go back to their rooms.

The staff are trying to work with Dariya one-on-one, as an alternative to having her disrupt the other residents, but she appears very confused and unable to hold a normal conversation. Even though she can speak English, she will only answer questions asked of her in English with a response in Ukrainian or sometimes Polish. She seems unhappy most of the time and can usually be found trying to wheel herself up and down the hallways, wanting to keep moving, and becomes agitated if left alone in one spot.

(Originally written: July 1995)

The post The “Poison Powder” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

March 23, 2017

“Little But Mighty”

Minnie Conrad was born on November 2, 1905 in Florence, South Carolina to Irvin Julian Wentworth Lewis, who was of English descent, and Victoria Edmundson, who was of Swedish descent. Irvin, it seems, was quite the Renaissance man and worked as a musician, a music teacher, a photographer and even a pharmacist at times, making and selling his own ointments. Victoria stayed at home and cared for their ten children: Roger, Elva, Jerome, Perry, Roscoe, Leola, Geraldine, Minnie, Marshall and Clinton. Surprisingly, all ten children lived to adulthood, though Victoria herself died when Minnie was just four years old. Unheard of at the time, Irvin kept and raised all ten of the children on his own. Minnie says that her father had a real zeal for life. He was always energetic, busy, and outgoing and had a “larger-than-life” personality, which, Minnie says, she had the good fortune to inherit.

Minnie Conrad was born on November 2, 1905 in Florence, South Carolina to Irvin Julian Wentworth Lewis, who was of English descent, and Victoria Edmundson, who was of Swedish descent. Irvin, it seems, was quite the Renaissance man and worked as a musician, a music teacher, a photographer and even a pharmacist at times, making and selling his own ointments. Victoria stayed at home and cared for their ten children: Roger, Elva, Jerome, Perry, Roscoe, Leola, Geraldine, Minnie, Marshall and Clinton. Surprisingly, all ten children lived to adulthood, though Victoria herself died when Minnie was just four years old. Unheard of at the time, Irvin kept and raised all ten of the children on his own. Minnie says that her father had a real zeal for life. He was always energetic, busy, and outgoing and had a “larger-than-life” personality, which, Minnie says, she had the good fortune to inherit.

Minnie managed to graduate from high school and then moved to Evansville, Indiana to live with her older sister, Leola. Minnie found a job as a telephone operator and went to beauty school at night. After that, she went to Branwell’s Business School and hoped to open her own beauty shop someday. Along the way, she met Wayne Philip Conrad, who was a journalist with the Evansville Courier. He was much older than Minnie, and Leola advised her to stay away from him, but Minnie was intrigued. Wayne pursued her, often taking her dancing or out with his reporter friends from the Courier, and Minnie soon fell head-over-heels for him.

The two got married, and soon after, Minnie had a baby girl, Elizabeth. When Elizabeth was just 18 months old, however, Minnie discovered that Wayne was having an affair, so she divorced him. Wayne insisted that the affair meant nothing, but Minnie wouldn’t listen. They went ahead with the divorce, but neither of them ever married again and they kept in touch for the rest of their lives until Wayne died in 1974.

After the divorce, Minnie pursued her dream and opened her own beauty shop, working long hours to make a living for her and Elizabeth. When she wasn’t working, she loved horseback riding and going to beauty shows and horse races. She also loved to play the piano and sing and late in life decided to learn to swim. Her real passion, though, she says, was dancing, and she still likes to dance even now in her eighties!

Minnie remained in Evansville until the 1960’s when many of her friends began moving away to other locales. Elizabeth had likewise long ago left home, having gotten married and moved to Chicago. Thus, Minnie decided to sell her shop and also move to Chicago to be near Elizabeth and her three children. Once there, she set about applying for an Illinois beauty license. Once in hand, she was hired by Helene Curtis as a hair color representative and was then accordingly sent all over the United States. Minnie adored this job and loved every second of her travels. “They treated me like the Queen of Sheba!” she says proudly.

Minnie is a charming, fascinating lady who loves to talk, especially about her career and her many adventures, both as a rep for Helene Curtis and as a business owner, and will willingly introduce herself to anyone. Elizabeth describes her mother as “a survivor,” and that raising a child alone in the South in the thirties and forties was “no easy task.” Elizabeth says that her mother had a strict routine and never varied from it and that she had two favorite sayings: “Little But Mighty!” and “Poor But Proud!” Elizabeth says that her mother was a great inspiration to her and to many other women in the South at that time. She also believes that Minnie never stopped loving her estranged husband, Wayne, but that both of them were too proud to ever reconcile. It is a source of her great sadness, Elizabeth says, that she grew up without her father.

Minnie lived a full, active life on her own until just about six years ago when she started to mentally slip a bit. Elizabeth’s son, Adam, went to live with Minnie for a number of years to help her and make sure she was okay. In the last year, however, Minnie has become more and more forgetful, including forgetting how to open the front door with her key, leaving the stove on, forgetting to eat, and even forgetting her own face. Adam says that many times, his grandmother became hysterical, saying that a stranger was in the apartment when it was merely her own reflection in the mirror. When Adam eventually moved out to pursue a job in another state, Minnie’s paranoia and anxiety increased so much that she had to move in with Elizabeth.

For a while Elizabeth coped by having Minnie go to adult daycare, which helped somewhat, but she needed constant attention in the evenings. Finally, Elizabeth made the decision for her to come to a nursing home and says that she does not feel guilty, as she believes she did everything she could for her mother.

Minnie, for her part, seems to be making a relatively smooth transition. At times she is capable of having an intelligent conversation and loves to join in activities, but at other times, she seems to experience episodes of confusion, particularly regarding Elizabeth. Perhaps because she spent two years in a day facility, she often becomes irritated when Elizabeth does not arrive to pick her up and “take me home.” She needs frequent reminders that this is her permanent home now. Overall, however, she is a sweet, zestful lady and is usually happy and content.

(Originally written: March 1995)

The post “Little But Mighty” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

March 16, 2017

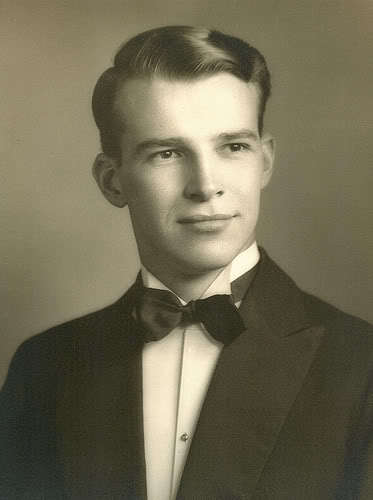

“Rats as Big as Cats!” and Other Stories from the Wonderfully Philosophic Oscar S. Cohen

Oscar S. Cohen was born on June 11, 1921 in New York City to David Cohen, an immigrant from Czechoslovakia, and Gladys Feldt, a native New Yorker. David worked as a shoe salesman, and Gladys cared for their two children: Oscar and Oliver. Oscar describes his parents as extremely intelligent and remembers that his mother spoke beautifully. She could speak to anyone, he recalls, “doctors, lawyers, the woman down the street.” Oscar believes he inherited his parents’ intelligence, but that he discovered it too late. He feels that he was not given enough guidance or encouragement and didn’t realize his potential until later in life. He learned a lot in grammar school under his strict, old-fashioned Irish teachers, but when he went to high school, he “didn’t learn a damn thing.”

Oscar S. Cohen was born on June 11, 1921 in New York City to David Cohen, an immigrant from Czechoslovakia, and Gladys Feldt, a native New Yorker. David worked as a shoe salesman, and Gladys cared for their two children: Oscar and Oliver. Oscar describes his parents as extremely intelligent and remembers that his mother spoke beautifully. She could speak to anyone, he recalls, “doctors, lawyers, the woman down the street.” Oscar believes he inherited his parents’ intelligence, but that he discovered it too late. He feels that he was not given enough guidance or encouragement and didn’t realize his potential until later in life. He learned a lot in grammar school under his strict, old-fashioned Irish teachers, but when he went to high school, he “didn’t learn a damn thing.”

After high school, he began working for an accountant and took business classes at City College of New York, the same school, he adds, that General Powell attended. When World War II broke out, he quit his job and school and reported to the war office. He got a deferment, however, because he was caring for his parents, so they asked him what other skills he had. He then described his love for mechanics and how he was in the habit of building various things at home as a hobby. Oscar believes it was this answer and his “beautifully printed application,” that landed him a job with the army working at Ford Instruments, which built, among other things, naval gunfire control units and later helped to develop computers.

Oscar worked at Ford Instruments until the war ended and then got a job working at Schlater’s Bar near where Rockefeller Plaza now stands. Oscar did everything there, from watching the floor to bartending to being a manager of sorts. In the role of manager, he had all the best musicians come in and play, including Dizzie Gillespie, his personal favorite.

During those years, Oscar saw all of the “seedy parts of life” and watched “prostitutes, pimps, and muggers” working the poor side of town where the bar was located. The best part of the job, he says, was the “free lunch of salted herring” and “free cigars.” After about five years of this, however, Oscar and his brother, Oliver, deiced to buy a liquor store together. They did not adequately research the neighborhood, though, Oscar says, as they discovered after the fact that there were five other liquor stores nearby. Business was extremely slow, except at Christmas time, and they made very little money.

The last straw occurred when the neighboring fish shop was torn down and a colony of huge rats was unearthed. Oscar found himself “eye to eye with rats as big as cats every time I took out the garbage! I couldn’t take it anymore,” he says, and so he and Oliver sold the shop. Besides the rat incidents, he was all the while becoming more and more disgusted with the whole cut-throat nature of the business, anyway. He couldn’t stand cheating customers in order to make a profit, especially since he saw so much of that happening all around him.

So for the next year or so, he “knocked around,” doing jobs here and there. He had several bigger opportunities, but he turned them all down, as most of them again involved him “taking advantage of people” in some form or another. The fact that his job prospects seemed to be going nowhere, plus the fact that he was also diagnosed at this time with diabetes, convinced Oscar that he had to search for a new career. He took some courses in lithography to become a film stripper, but realized that his eyesight was too poor to do that kind of work. Instead, he opted for the printing side of things. He worked in a couple of shops, learning the business and working in various positions until he became a pressman. He then got a job at a bigger company, where he joined a printers union, and continued working there as a pressman for sixteen years. It turns out that he was very well-suited to printing, and learned many tricks over the years on how to be organized, fast and efficient. Unfortunately, however, despite the fact that he had found a career he really liked, he had to retire when he was fifty-one due to arthritis in his hands.

He was living in the same apartment he had grown up in, having cared for his parents and his father’s cousin until they all passed away. He did a little bit of traveling, taking trips to Philadelphia and the White Mountains, and liked to go out to hear live music. He says he was never a heavy drinker, having seen enough of that during his years at Schlater’s Bar. He smoked until he was seventy and then quit, though he doesn’t think he did much damage because he “never inhaled deeply.” He also spent a lot of time at home listening to his collection of big band records and reading voraciously. He is a avid fan of classic literature, Shakespeare and Cyrano De Bergerac being his favorites. He enjoyed mechanical projects of any nature and did quite a bit of woodworking over the years, as well. Despite the solitary nature of his hobbies, however, he is a very, very social person. He attended the synagogue in his neighborhood in New York for years and had many friends there, but he never married.

His brother, Oliver, however, did get married, and just around the time Oscar was retiring, decided to move his family to Chicago. Oliver and his wife, Judy, urged Oscar to come, too, but Oscar wanted to remain in New York and stayed there alone for another seventeen years. At that point, in 1989, Oscar fell and broke a hip and was finally convinced by Oliver to move to Chicago so that he would be near family. Oliver helped him to find an apartment in Rogers Park in a building for Jewish senior citizens. Oscar enjoyed his new apartment and his new city, though over the next seven years, his health continued to deteriorate.

In that time, he had two more hip surgeries, cataract surgery, two operations on his intestines, a colostomy, prostrate surgery and is now on dialysis. His doctor calls him “a medical miracle” to still be alive. He was recently hospitalized for various reasons for about six months, after which time his doctor recommended nursing home placement. Knowing that he could no longer care for himself, Oscar agreed. Before he was discharged, then, Oliver and his daughter, Pam, helped to find a place for him in the current facility, where he is making a smooth adjustment.

Despite all of his physical ailments, Oscar’s mind is crisp and sharp. He loves words and loves to talk, but despises small talk. He craves in-depth, intellectual conversations, and like his mother, Gladys, can speak on any subject—from the latest news, to Eleanor Roosevelt’s abilities to run the country during the Depression, to Shakespeare, to the national debt. He calls himself a “chain thinker” because “one thought leads to another and another.” Oscar credits his vast knowledge to reading every day on the bus back and forth to work, which, he says, was his “real education.” Reading, he says, “is the secret to education and the secret to writing.”

Politically, Oscar describes himself as a liberal and doesn’t believe the current thinking that today’s problems are the result of problems in the family. He believes that society’s problems are caused by poor educations and the lack of discipline in today’s youth. He feels that “too much freedom is bad.” On the other hand, he thinks minds can become closed with “too many rules and regulations. They become warped somehow.” People, he says, “are only interested in following an instruction book at work and have no room for initiative or invention.”

Despite these somewhat depressing theories, Oscar is not a bitter, negative, cynical man in any way. He says, “Some people come out crying. I was born laughing.” He says that throughout his life, he was prone to worry, but he tried very hard to control it. He handled stressful situations by “fumbling through them.” He once read that the secret to happiness is to “keep laughing and keep in a good humor,” a philosophy he whole-heartedly adopted. Indeed, Oscar is always laughing and has a wonderful sense of humor. He is aggravated when people “blame God for everything.” His theory is that “man shares 50/50 with God in ruling this world, and if something gets screwed up, it’s not God’s fault.” Oscar is a delightful, charming man who loves to engage with all around him.

(Originally written: July 1996)

The post “Rats as Big as Cats!” and Other Stories from the Wonderfully Philosophic Oscar S. Cohen appeared first on Michelle Cox.

March 9, 2017

A Life of Watching From Afar

Vlasta Di Stefano was born on January 21, 1910 in Chicago to Bela Hrabe and Lazar Dragic. Bela was an immigrant from Czechoslovakia, and Lazar emigrated from Yugoslavia. The two apparently met at Ellis Island and, though they initially went their separate ways, they wrote letters to each other for the next year or so. Eventually, they somehow met up again and married, settling in Chicago on Harding Avenue. After a few years, however, they left the city and moved to a farm in Minnesota. Besides farming, Lazar worked delivering lumber, and Bela cared for their seven children, of which Vlasta was the fourth.

Vlasta Di Stefano was born on January 21, 1910 in Chicago to Bela Hrabe and Lazar Dragic. Bela was an immigrant from Czechoslovakia, and Lazar emigrated from Yugoslavia. The two apparently met at Ellis Island and, though they initially went their separate ways, they wrote letters to each other for the next year or so. Eventually, they somehow met up again and married, settling in Chicago on Harding Avenue. After a few years, however, they left the city and moved to a farm in Minnesota. Besides farming, Lazar worked delivering lumber, and Bela cared for their seven children, of which Vlasta was the fourth.

Vlasta attended grade school, but at age thirteen, she decided to move back to Chicago, where her older sister and her husband had already returned. Vlasta lived with them and got a job at Union Linen Supply and there met her future husband, Ruben Alvardo, a Mexican immigrant. Ruben liked Vlasta immediately and often took her on picnics to a picnic grove at Devon and Milwaukee, which was still a wooded, green area back then. He eventually proposed to Vlasta, and they married when she was just nineteen.

Ruben continued working at Union Linen, and Vlasta quit once she became pregnant with their first child. Ruben and Vlasta had a total of six children, and when the youngest, Sandalio, was a toddler, Vlasta went back to work. Union Linen Supply had no openings, however, so she instead got a job at a company called Cromane, which did silver plating.

According to her daughter, Viola, Ruben and Vlasta were very private people. They did not have friends, nor did they associate with either of their families. They even refused to go to any school functions, including their own children’s graduations. Their only pastime, says Viola, was drinking. In fact, when Vlasta decided to return to work, she dumped all of the household cleaning, management and cooking unto Viola, the oldest girl, who was roughly eleven at the time. From that point on, Viola became the mother-figure for the whole family and remains so even today.

Tragically, in July of 1950, Ruben was hit by a car and killed while walking home from work. He was not yet 50 years old. Vlasta continued working, doing her best to make ends meet and eventually met and married David Di Stefano. She only had about ten years with David, however, before he died of cancer. After that, Vlasta lived alone, watching her neighborhood slowly decline, and was attacked twice coming home from the shops. She put her name in to get a place in North Park Village, but had to wait ten years for a spot to open up.

When Vlasta did finally move into the North Park Village senior apartments about seven years ago, she was still relatively independent, but as time has gone on, she has relied more and more on Viola to again help her with cleaning, laundry and shopping. Recently, though, things have become worse, with Vlasta not being able to care for herself at all. Viola has been in the habit for the last several months of coming to Vlasta’s apartment twice a day to feed her and clean up urine and feces that is usually found on the floor or furniture. Viola has been beside herself with worry, as she has often come to the apartment and found the stove on and pans burnt through. Fearing that she would possibly have a nervous breakdown from the stress of the situation, Viola finally decided to admit Vlasta to a nursing home.

Viola, in the role of mother since age eleven, feels incredible guilt at not being able to still care for Vlasta, but they are both adjusting to the new living arrangements. Viola predicted that Vlasta would be extremely angry at being placed in a home, and was therefore pleasantly surprised by Vlasta’s easy transition. Vlasta is confused at times and does not talk a lot, but she enjoys sitting among the other residents. Though not always eager to participate in activities, she very much likes to watch what is going on, perhaps a life-long behavior. Viola claims that her mother never had any hobbies and never wanted to “get involved.” She says that Vlasta “watched everything from afar. She was content, but never really that happy, even on birthdays or holidays.” The only time she appeared happy, says Viola, is when she had a drink in her hand, preferably a Tom Collins.

(Originally written May 1996)

The post A Life of Watching From Afar appeared first on Michelle Cox.

March 2, 2017

A Sort of Hansel and Gretel Story . . .

Hana Jezek was born on September 25, 1922 in Brezova, Czechoslovakia to Bartholomew Jezek and Irena Vedej. Bartholomew was a soldier and was always on the move with the army. It was in one of the little villages he traveled through that he met Irena and fell in love with her. They eventually married and had two children: Hana and Bartholomew, Jr., or Bart, as he came to be called.

Hana Jezek was born on September 25, 1922 in Brezova, Czechoslovakia to Bartholomew Jezek and Irena Vedej. Bartholomew was a soldier and was always on the move with the army. It was in one of the little villages he traveled through that he met Irena and fell in love with her. They eventually married and had two children: Hana and Bartholomew, Jr., or Bart, as he came to be called.

In 1929, when Hana was seven and Bart five, the situation in Czechoslovakia was so bad that Bartholomew and Irena decided to try a new life in America. Bartholomew had brothers and sisters who had already made the journey and had settled in Chicago. They were constantly urging Bartholomew and Hana to join them, and, finally, the two decided to go. Once the decision was made, one of Bartholomew’s brothers wrote and advised them to come without the children, as they would be unburdened that way and could make more money. At first, Irena refused to leave Hana and Bart, but after much pleading, Bartholomew finally convinced her to leave them with a grandmother. Irena cried and sobbed when it was time to leave and was often depressed and inconsolable on the ship bound for America.

Once in Chicago, Bartholomew got a job with his brother at the Brach Candy Company on the night shift, and Irena found work at S. K. Smith, which was a lithography company. After four long years of working, they were finally able to send for Hana and Bart, who arrived in America on December 15, 1933. They travelled on a ship in the care of several other people from their village who were immigrating, too. Irena was overjoyed to see her children, never having forgiven herself for leaving them behind. Irena always said that it was their best Christmas ever. From that point on, she spoiled her children completely.

In 1940, the family had saved enough to buy a little house on Karlov Avenue, where Hana has lived ever since. When she graduated from high school, Hana got a job at the Zenith radio factory and worked there for 42 years, never missing a day. Her parents were similar in that they remained at the original jobs they found upon arrival in Chicago – all the way until the day they retired. Hana says that her family was just like that. “Once they had a thing,” she says, “they always stuck to it,” whether it was a job or a house or a car. “They didn’t like change.”

Perhaps that is the reason why Hana never married, though she says it was because the right fellow never came along. She instead devoted herself to working and to her hobbies, which included travel. Hana loved travelling and went all over the United States with her mother. Bartholomew never wanted to go, saying that he had travelled enough as a soldier when he was a young man. He called himself “a homebody,” preferring to stay and take care of the house while his wife and daughter went on their trips. He adored both of them and always had a hot meal waiting for them when they returned from their travels.

Hana enjoyed knitting and crocheting and was very active in their church, Trinity Lutheran. Later in life, she developed a passion for going to the movies and went to see all the new films, either with girlfriends or her mother, at the Gateway, the Karlov, the Tiffin or the Logan. Hana lived with her parents her whole life on Karlov Avenue, caring for them as they aged until they died in their eighties. Bartholomew died of congestive heart failure at age 82, and Irena died after a stroke at age 86 in 1990. Since then, Hana has lived alone in the house, though Bart and his family live close by.

Hana very recently began experiencing chest pains and was hospitalized with what she thought was heart problems. It turned out to be a respiratory condition, however, requiring oxygen, and her doctor felt she should be admitted to a nursing home until her condition clears and her health improves. Hana agrees with her doctor’s advice, but she fully plans to return to her home on Karlov as soon as she can. Bart and his wife, Dorothy, likewise feel this is a realistic goal and are very supportive.

Hana and Bart have remained close over the years. When WWII broke out, Bart enlisted in the army, and Hana wrote to him every week with the news from home. When he came back from the war, he married the girl who lived down the street, and they eventually bought a house on Karlov as well. Hana loved her sister-in-law, Dorothy, and was very involved in the lives of her nieces and nephews. They visit her often even now, bringing their own children to see “Great Aunt Hana.” They appear to be a very loving family and concerned with Hana’s well-being and comfort.

Until she can go home, Hana is patiently biding her time, careful to follow her doctor’s instructions to the letter. She is very cheerful and friendly, and seems to genuinely like talking with the other residents and participating in almost every activity the home has to offer.

(Originally written: December 1994)

The post A Sort of Hansel and Gretel Story . . . appeared first on Michelle Cox.

February 23, 2017

“He Was Never The Same.”

Felix Dubicki was born on July 12, 1928 in Chicago to Izaak Dubicki and Anontia Grzeskiewicz, both immigrants from Poland. It is thought that Izaak and Antonia met and married in Chicago, but Felix isn’t sure. He knows that his father worked here in a tannery and that his mother cared for their four children: Andrew, Danuta, Felix and Felicia. Felix does not recall much about his parents, but Felicia relates that Izaak and Antonia “suffered many hardships” in Poland and that they were very poor. According to Felicia, they had “a different mindset, a different outlook on life.” Children were not beloved priorities to them, but were instead seen as accidents. For Izaak and Antonia, life was not about providing a loving, happy environment for their children, it was about surviving, and each child that came along made surviving that much harder. Felix is especially bitter about his childhood and has no deep love for his parents.

Felix Dubicki was born on July 12, 1928 in Chicago to Izaak Dubicki and Anontia Grzeskiewicz, both immigrants from Poland. It is thought that Izaak and Antonia met and married in Chicago, but Felix isn’t sure. He knows that his father worked here in a tannery and that his mother cared for their four children: Andrew, Danuta, Felix and Felicia. Felix does not recall much about his parents, but Felicia relates that Izaak and Antonia “suffered many hardships” in Poland and that they were very poor. According to Felicia, they had “a different mindset, a different outlook on life.” Children were not beloved priorities to them, but were instead seen as accidents. For Izaak and Antonia, life was not about providing a loving, happy environment for their children, it was about surviving, and each child that came along made surviving that much harder. Felix is especially bitter about his childhood and has no deep love for his parents.

Felicia explains that this is probably because when she was eleven and Felix was twelve, Izaak and Antonia divorced. Andrew and Danuta were old enough, apparently, to fend for themselves, but Felix and Felicia were sent by their parents to live in an orphanage. Felicia says that though it was difficult, but she managed to make it through relatively unscathed. Felix, on the other hand, was quickly nicknamed “Jammy” by the other orphans because he was always getting himself into “jams” and subsequently punished. According to Felicia, Felix was a very outgoing, fun-loving child, but after his experience at the orphanage, he “crawled into a shell” and became very quiet and introverted for the rest of his life.

After several years, Antonia was financially stable enough to bring Felicia and Felix back home to live with her and consequently enrolled them in high school. After only two years, though, Felix came down with rheumatic fever and had to quit. When he eventually recovered, he gave up school altogether and became what was known as a paper handler in a printing company called Chicago Roller Print on Fulton Street.

Felix continued to live with his mother, even after Felicia married and moved out. Eventually, however, Felix moved into his own apartment because Antonia was “too hard to take,” though he continued to financially support her. Felicia confirms that Antonia was a very difficult person to get along with. Once he was on his own, Felix began to drift from the family and became more and more of an introvert. Even Felicia, to whom he was the closest, lost contact with him. Life continued this way for the next twenty years, with Felix living a separate existence from his family. He never married, and Felicia says she never knew him to ever even have a girlfriend.

Over the years, Felix continued working for various print shops, including the Sun Times, the Tribune and Irving Berlin Press. His passions in life seemed to have been listening to opera, watching football, and going to the Lincoln Park Zoo. He apparently visited the zoo almost every day, saying that he much preferred the company of animals to humans. In his late forties, however, he did finally reach out to Felicia, who was surprised but happy that he had contacted her. Over the next decade, they had sporadic communication, Felicia suspecting that not only was she his only friend during those years but that he was an alcoholic as well.

When Felix was 55 years old, he was diagnosed with diabetes and was off work for a significant period of time. Unfortunately, this coincided with a shift that was occurring in the printing industry as a whole. It was becoming more and more automated, almost eliminating the need for manual paper handlers; thus, Felix found himself out of a job. Not knowing what else to do and still suffering from complications due to his diabetes, Felix went to live with Felicia. Felicia reports that in the beginning, when he was only receiving a small unemployment check, his drinking subsided significantly, but then when he began receiving larger disability checks, he went back to drinking heavily.

Felicia says that having Felix live with her wasn’t too much of a burden, as he stayed mostly in his room. He seemed depressed and unhappy most of the time, and she suspects that in 1993 he may have even tried to kill himself. Felicia does not elaborate on the details of what exactly happened, but says that Felix wound up in the hospital and was then discharged to a nursing home. He stayed in that particular facility for about a year before returning to live with Felicia. It was short-lived, however, because he needed so much more assistance than he had before, and Felicia, herself getting up in years, couldn’t help him or afford to hire anyone.

Felix was determined to not go back to a nursing home, however, so he decided to move into the Lorali apartments on Lawrence Avenue on his own. This arrangement only lasted about three days, however, before he became dizzy and fell. Felicia says it is probably because he didn’t eat right. His eyesight, she says, is also so bad that he cannot correctly read the numbers on his insulin syringe. When admitted to the hospital again, his numbers were so severely off that his doctor would only agree to release him to a nursing home, saying that he was lucky to even be alive.

Felix has thus far made a relatively smooth transition to his new placement, but he remains quiet and withdrawn. He never speaks to the other residents, even if they ask him a question. He appears “in his own world,” much of the time, something he has been doing since he was “a little kid,” Felicia says. Though it is hard for her to get around, Felicia visits regularly. She seems very concerned for Felix and thinks that he is still very depressed. She is at a loss on how to help him, however, saying that Felix “has never been happy.” He was as a little boy, she says, but having to go to the orphanage changed something in him. “He was never the same.”

(Originally written: July 1996)

The post “He Was Never The Same.” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

February 16, 2017

“I Had Too Many Problems at Home”

Aurora Sienkiewicz was born on April 5, 1911 to Giovanni and Rosa Corvi, both of whom were immigrants from the same small village in Italy. Giovanni and Rosa knew each other from the time they were little, and, in fact, one day when Giovanni was passing by, Rosa pointed to him and told her mother that someday she was going to marry Giovanni. Giovanni and Rosa did indeed get married and had a son, Marco.

Aurora Sienkiewicz was born on April 5, 1911 to Giovanni and Rosa Corvi, both of whom were immigrants from the same small village in Italy. Giovanni and Rosa knew each other from the time they were little, and, in fact, one day when Giovanni was passing by, Rosa pointed to him and told her mother that someday she was going to marry Giovanni. Giovanni and Rosa did indeed get married and had a son, Marco.

When Marco was just five years old, Giovanni decided to go to America and look for work and a new life. He soon found a job in New York, so he sent for Rosa and Marco to join him. They came by ship with many people from their village, so they were not alone on the journey. Once is New York, Rosa got pregnant several times, but always miscarried. They were all girls, and Rosa named them all Aurora after Giovanni’s mother, as was the custom.

From New York, the family moved to Louisiana, where another son, Frank, was born. The Corvi’s did not stay long in Louisiana, however, before moving to Chicago. Chicago was supposed to be a temporary stop, as their final destination was California, which was Giovanni’s dream place to settle. Once in Chicago, however, Giovanni got a good job in a cigar factory and Rosa found work sewing buttons on trousers at home, so they decided to stay. After that, Rosa was finally able to conceive and carry a girl, Aurora, and then had another boy, Vincent.

Aurora went to school through the 8th grade and then got a job in a paper box factory at age fourteen. She worked in various factories during her teen years, but she especially liked working at a stencil factory because they got to use chemicals. She found chemistry very interesting, and she became friends with one of the factory chemists, John Petronka. Aurora says that she is pretty sure John had a crush on her, but he was already engaged to someone. Thus, he introduced her to his good friend, Thaddeus Sienkiewica. Though Thaddeus was of Polish descent, not the Italian Giovanni hoped she would find, he and Aurora hit it off right away and soon married.

Thaddeus worked at Western Oil for over forty-five years, and Aurora cared for their four children: Gloria, Phyllis and the twins, Roman and Roy. Like her mother before her, Aurora had many miscarriages over the years, and finally, after the twins were born, her doctor advised her to have a hysterectomy, to which Aurora agreed. When all of the children were in school, Aurora decided to go back to work and got a job as a kitchen aide in various hospitals until she was sixty years old.

Sadly, Aurora’s marriage was not a happy one, as Thaddeus turned out to be an alcoholic. Aurora says that this is why she was always a loner and had no friends or hobbies. “I had too many problems at home to worry about,” she says of that time. Having no one else to turn to, Aurora would sometimes confide in her mother, Rosa, regarding her marital woes, but Rosa, and Giovanni, for that matter, refused to ever talk badly about Thaddeus and stood by the marriage.

Finally, however, Aurora could no longer stand how Thaddeus’s behavior was effecting the children, so she separated from him. It was an extremely difficult thing to do, especially as her parents disapproved and would not support her, financially or emotionally. Thaddeus moved into his own apartment, and though she had some contact with him over the years, she pretty much raised the family on her own.

After her divorce, Aurora still stayed home much of the time in the evenings, but felt freer to make friends and invite them over. Occasionally, she would venture out to a movie or bingo at St. Philips, where she was a faithful parishioner. Only once did she take a trip, which was to go to California to see her brother, Vincent.

Tragically, when Aurora was in her mid-seventies, she had to endure the death of her son, Roman, who was forty-five at the time. He died of complications due to his colitis condition. Aurora says that he was not married and didn’t take care of himself as he should have. “He lost the will to live,” she says. After his death, Aurora refused to ever talk about Roman, though she says that she still mourns his loss.

Up until very recently, Aurora was living alone and was still active and able to care for herself. About a year ago, however, she had a small stroke and fell. As Phyllis is the only one of Aurora’s children still living in the area, much of the burden of caring for Aurora fell to her. The staff at the hospital suggested that Aurora be discharged to a nursing home, and Aurora reluctantly agreed with this decision.

While Aurora seems resigned to her fate, Phyllis does not. Because of her own health problems, she cannot care for Aurora at home and seems to feel very guilty about this. In just the last year, Phyllis has changed nursing homes for Aurora three times, as Phyllis—not necessarily Aurora—has been very unhappy with each placement, including the current one. Phyllis frequently lashes out at the staff, accusing them of a variety of things and can even be verbally abusive at times. Already she has threatened to remove Aurora yet again.

Meanwhile, Aurora seems not aware of Phyllis’s distress. She appears to be content, her favorite activity being bingo. At times she is confused and believes that her clothes are missing, which causes her to complain repeatedly to the staff. Once she becomes upset, she then tends to bring up Thaddeus and the anger she still feels towards him. “He’s living alone, free and easy, and here I am!” she will say, over and over. Normally, however, she is a pleasant woman who enjoys having conversations with the other residents or watching TV with them. It is not yet known if Phyllis will leave Aurora to finally settle into a place or if she will move her again, as she has warned she intends to do.

(Originally written August 1996)

The post “I Had Too Many Problems at Home” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

February 9, 2017

“I Didn’t Have the Best Life, But I Made It.”

Chester Williamson was born on July 18, 1930 in Greenwood, Mississippi to Walter Williamson and Ethel Jones. In the early 1940’s, the family moved to Chicago to look for work. Walter found a job in a steel mill and worked at night at a restaurant while Ethel cared for their nine children, of which Chester was the second youngest.

Chester Williamson was born on July 18, 1930 in Greenwood, Mississippi to Walter Williamson and Ethel Jones. In the early 1940’s, the family moved to Chicago to look for work. Walter found a job in a steel mill and worked at night at a restaurant while Ethel cared for their nine children, of which Chester was the second youngest.

The Williamsons moved around the city a lot as Chester was growing up, never staying in any one apartment for long. Chester struggled with school, and, finally, after 6th grade, he quit. He couldn’t find a job, however, and spent his days roaming the streets and getting into trouble. He was eventually arrested and sent to the state penitentiary until he was released in 1951 at age 21.

It was also at this time that Chester discovered that he had some sort of infection in his right lung, which resulted in him having to have part of it removed. Knowing that he would never be able to do hard labor, he enrolled in barber school and earned his certificate after a year. He proceeded to find work at different shops around the South Side and eventually met Lorraine Davis, who was the sister of one of his customers. Chester and Lorraine hit it off right away and married soon after. They moved into one of the newly built high-rises of Cabrini-Green and had twin girls: Sandra and Suzanne.

Chester says he was happy with Lorraine overall, but something inside him just couldn’t stick to any one person or thing. He left, then, and became what he called “a floater.” This continued for a couple of years before he realized that he still loved Lorraine. It was too late, however, and when he returned to her, she filed for divorce.

Chester then went back to his “floating” lifestyle for the next thirty years, spending his time at the racetrack, listening to music in clubs, and traveling throughout the US and Canada. He had some contact with Lorraine and his girls over the years, but not much. To his knowledge, Lorraine is still living in Cabrini-Green, and he knows he has at least one granddaughter.

In the early ‘80’s, after a lifetime of working on and off in various barber shops, Chester decided that he really wanted to have his own shop. He hadn’t the slightest idea of how to go about it, though, nor anyone to consult with. He was determined, however, perhaps for the first time in his life, so he began the long process of waiting in line, filling out forms, getting approvals, and passing inspections to make his dream come true. Finally, after a couple of years of getting organized, he was able to open “Chester’s Cuts” on Broadway.

Chester’s Cuts was apparently a success, and Chester even expanded it into a neighboring storefront. After seven or eight years, however, it got to be a little too much for him, and he began to struggle with managing everything. When he fell and broke his hip in the early ‘90’s and the building owner simultaneously raised his rent, Chester decided to give it all up and sell the shop. With the little money he made, he decided to move into a retirement community in the suburbs, where it was discovered he had kidney failure due to his lifetime use of alcohol.

Chester remained at the retirement home for about a year before deciding to move into a nursing home in the city. So far he has made a relatively smooth transition and gets along with his roommate, Mr. Kim. Chester says that he dealt with stress throughout his life by drinking, but at some point, he realized that stress and alcohol will always be around, so he had to make a conscious decision to quit. He says the key to success is to “approach things honestly.”

So far no family members have come forward to visit Chester, though he hopes his sister, Clara, his only living sibling of the original nine, will appear at some point.

Chester is extremely proud of the fact that he owned a barbershop, that he persevered through so much to attain it. Upon reflection, he says, “I didn’t have the best life, but I made it.”

(Originally written: August 1995)

The post “I Didn’t Have the Best Life, But I Made It.” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

February 2, 2017

“He’s All I Have”

Frieda McLeod was born on April 9, 1917 in Chicago to Robert Curran and Eileen Walsh, both immigrants from Ireland who came looking for a new life. Robert found work on the railroads and also delivering coal and flour, while Eileen worked as a cleaning lady in private homes and cared for their five children: Ruth, Charlie, Mary, Frieda and Ina.

Frieda McLeod was born on April 9, 1917 in Chicago to Robert Curran and Eileen Walsh, both immigrants from Ireland who came looking for a new life. Robert found work on the railroads and also delivering coal and flour, while Eileen worked as a cleaning lady in private homes and cared for their five children: Ruth, Charlie, Mary, Frieda and Ina.

Tragically, when Frieda was just five years old, Eileen contracted tuberculosis and died at age thirty-seven. Grief-stricken, Robert “fell apart” and was unable to cope with caring for the family. The first of his problems was the newborn baby, Ina, who had also been born with TB and was still in the hospital even as Eileen was dying. Ina languished in the hospital for two more years before she was well enough to be released. By that time, however, there was no one to come home to, so Robert arranged for her to be placed directly into foster care from the hospital. Ruth, the oldest, had begun having seizures shortly after Eileen died, which the doctors diagnosed as mental illness, and she had accordingly been sent away to a mental institution. Charlie had been sent to a foster home, and Mary and Frieda had been sent to live at the Sisters of Mercy Home in Des Plaines. Mary had hated it there, however, and was eventually released into foster care as well. Frieda, just five, hadn’t minded the Sisters of Mercy Home and stayed until she was eighteen. Frieda says she only remembers her father visiting once. Frieda completed the 8th grade at the Home and even finished a two-year business degree there.

Upon graduation, she left the Sisters and got a job working at Navy Pier as a secretary in the WPA offices. Frieda enjoyed her new surroundings and her new freedom very much. Through friends, she was eventually introduced to a man by the name of Guy Knowles. Guy was an engineer in his thirties, and though Frieda was young, they began dating. Frieda fell in love with him very quickly, and she was still just eighteen when they married. They had a baby, Dewey, together, but the marriage soured soon after that. Apparently, Guy had been married several times before and found it hard to stay with one woman. When Dewey was just 18 months old, Guy left to pursue a “business opportunity” in Connecticut, leaving Frieda and Dewey to fend for themselves.

In desperation, Frieda turned to her sister, Mary, and went to live with her. She and Dewey remained there for several years, Frieda taking jobs in various factories and offices until she landed a job at Sears, Roebuck, where she remained for over thirteen years. It was extremely difficult to care for Dewey and work full time, however, especially during the war years, so Frieda eventually placed him in foster care until she could manage better.

Frieda eventually remarried, this time to a man named Roland Cooke, who worked as a mechanic. Frieda sent for Dewey to come home and live with them, but he had a hard time adjusting to life with his new stepfather, who turned out to be an alcoholic and abusive. Dewey became a delinquent and was frequently in trouble with the police. He began taking drugs and became addicted to heroin. Finally, he was put into a series of juvenile homes until he became an adult and was then sent to prison. Dewey admits that he has led “a bad life” and regrets that he caused Frieda so much grief over the years.

Frieda, he says, has “a heart of gold,” and despite all of her own troubles and poverty through the years, always had an open-door policy. For the time he did live at home with her, Dewey remembers that their house was always open to anyone who needed a place to stay until they could get back on their feet again. Frieda, he says, was a true “good Samaritan,” never worrying about herself.

Frieda eventually divorced Roland and then married Gordon McLeod, a retired fire lieutenant, but it, too, broke up after a few years. Frieda then went to live with her sister, Ina, for a little while and from there moved in with Dewey. For the few years they lived together at that time, Frieda and Dewey seemed to have gotten along, their favorite pastime being to go and watch various Chicago sporting events. Frieda is a big fan of all the Chicago teams: Bears, Bulls, Blackhawks, Cubs and Sox and would go to see any of them at any time.

Eventually, however, Frieda’s declining health got to be too much for Dewey to handle, considering his own long list of problems and issues. Somehow the State Guardian’s office got involved in Frieda’s case and appointed her a public guardian, Karen Vargos. Karen then helped arrange for Frieda’s admission to a nursing home, where she has been now for about six months.

Frieda is a quiet, pleasant woman, but she appears depressed and apathetic. She has no interest in forming any new relationships or joining in any activities, nor does she really seem to want to converse with the staff. She enjoys smoking and watching sports on TV and waits for Dewey’s visits, which are infrequent. She misses him, she says. “He wasn’t a very good son, but he’s all I have.”

(Originally written January 1995)

The post “He’s All I Have” appeared first on Michelle Cox.