Michelle Cox's Blog, page 31

August 24, 2017

“A Little Slice of Heaven”

Floyd Vesela was born on January 14, 1911 in Chicago. His parents were Anton Vesela and Helena Starek, both of Czechoslovakian descent. It was always assumed that both of his parents were born in Chicago, but Floyd thinks his mother may have actually been born in Czechoslovakia and came here as an infant with her family. Either way, Floyd and his five siblings were raised to be proud of their Czech heritage.

Floyd Vesela was born on January 14, 1911 in Chicago. His parents were Anton Vesela and Helena Starek, both of Czechoslovakian descent. It was always assumed that both of his parents were born in Chicago, but Floyd thinks his mother may have actually been born in Czechoslovakia and came here as an infant with her family. Either way, Floyd and his five siblings were raised to be proud of their Czech heritage.

Anton worked as a bricklayer, and Helena cared for their six children, of whom Floyd was the youngest. They lived on St. Louis Avenue on the west side of Chicago. Tragically, when Floyd was still very little, one of his brothers, Herbert, climbed an electricity pole while they were playing and was electrocuted and died. Floyd was very much affected by his brother’s death and supposedly had terrible nightmares for a long time after. Even now, he doesn’t like to talk about the accident.

Floyd says that besides his brother’s death, he had what was probably considered a normal childhood for the time. He and his siblings attended grade school and mostly played in the streets, though he did join the local Boys Club and played a lot of sports there. When he graduated from grade school, he went on to attend high school and even graduated. Anton was very proud of the fact that Floyd went to high school, as he was the only one in the family who did so. All the others had had to quit to find work. Floyd then trained to become an electrician—an interesting career choice considering his brother’s death—and eventually found a job at Western Electric in Cicero.

Not long after, however, the family was again shaken when Anton was tragically killed in an accident at work. He was working on the construction of a building downtown when a load of bricks fell from the 30th story of the building and landed on top of him. He lived through the accident, but he had severe brain damage and only lasted a week before he died. All of his siblings had already moved out by then, so Floyd remained and cared for his mother.

One of the things Floyd enjoyed doing for fun was going out dancing after work. The Aragon Ballroom was his favorite, and he went nearly every weekend. It was there, in fact, that he met a lovely young woman by the name of Thelma Schultz. The two fell in love and eventually married and continued going to the Aragon every weekend for several years before they had children. They enjoyed going with two other couples with whom they shared expenses, namely gas and drinks. They would usually go on Sundays at 3 pm to practice before the “real thing” started. Wayne King and his orchestra would play, and Floyd says that to be there was like “a slice of heaven,” even if they didn’t dance and instead just sat and listened to the music.

Floyd and Thelma eventually had two children, Russell and Sadie. When they were first married, Floyd and Thelma lived in an apartment in the Pilsen neighborhood, but when Russell was about five, they bought a house in Berwyn. As the children got older, Floyd and Thelma mostly stayed at home, only occasionally going back to their old stomping ground at the Aragon. Russell relates that his father did not have a lot of hobbies and didn’t go out much with the guys. “He worked all day and then came home and watched TV.” He liked to make people laugh, though, says Russell, and he “had a genuine concern for other people’s welfare.” He always helped Thelma with the housework, and besides being a very skilled electrician, he was also an excellent craftsman at mechanics. He worked at Western Electric his entire life, retiring at age 68. In all, he had put in fifty years there.

According to Russell, Floyd never stopped being in love with Thelma, and he was likewise completely dependent on her. She pampered him completely, something he was used to as the youngest child of six kids. When she died of cancer, then, in 1984, Floyd was devastated, and he was left helpless. “He had no idea how to exist on his own,” says Russell. “He couldn’t balance a checkbook and had no idea how to pay bills.” Both Russell and Sadie stepped in to help him at this sad time and tried to teach him some basic skills.

Floyd eventually got the knack of living independently, but in 1991, he decided that it was getting too difficult. He sold the house in Berwyn that he and Thelma had bought back in 1940 and moved into a retirement community. After that, Floyd’s health continued to decline, and he was then transferred to the “nursing home” part of the facility. He was very unhappy there, however, and repeatedly asked Russell or Sadie to transfer him to a different nursing home. This was a difficult request, as Russell had moved to California at the same time that Floyd moved into the retirement community, and Sadie had been living in Georgia for years. Finally, however, Russell made time to fly back to Chicago to help his father transfer to his current nursing home, which has a high population of Czechs.

Floyd is happy with the change and delighted in his new home. At times he is confused and moody, but overall he seems happy. He likes to walk in the gardens and watch sports on TV in the dayrooms. He is also a big fan of the big band hour on Sundays, and says he loves the Czech food served in the dining room, especially the Czech beer served on weekends. He still misses Thelma, he says, but he is content knowing that she is waiting for him.

(Originally written: Sept. 1994)

The post “A Little Slice of Heaven” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

August 17, 2017

“No Place to Hang My Hat”

Franklin Wilson was born on August 24, 1931 to Lincoln Wilson and Ethyl Jackson, who worked a forty-acre farm near Chatham, Louisiana. The Wilsons had nine children: Calvin, Chester, Anita, Franklin, Roland, Ida Jean, Lily Mae, Hattie and Daisy Mae, all of whom lived into adulthood. Besides working their own farm, Lincoln also worked on the side as a logger, and Ethyl chopped cotton and did housework for “white people” in town. Franklin went to school through the ninth grade and then quit to help his dad on the farm. When he was eighteen, he was drafted and served for two years, fighting in Korea.

Franklin Wilson was born on August 24, 1931 to Lincoln Wilson and Ethyl Jackson, who worked a forty-acre farm near Chatham, Louisiana. The Wilsons had nine children: Calvin, Chester, Anita, Franklin, Roland, Ida Jean, Lily Mae, Hattie and Daisy Mae, all of whom lived into adulthood. Besides working their own farm, Lincoln also worked on the side as a logger, and Ethyl chopped cotton and did housework for “white people” in town. Franklin went to school through the ninth grade and then quit to help his dad on the farm. When he was eighteen, he was drafted and served for two years, fighting in Korea.

When he returned home, he married his childhood sweetheart, Rosalie Stump. They had a nice wedding, Franklin remembers. “All of the neighbors came” and even some of his friends from the army showed up. They took a honeymoon trip to Miami, Florida, which was their one and only vacation. They had two children, Minnie Jo and Nellie Jo, just one year apart. After that, Rosalie couldn’t seem to get pregnant again, though she supposedly wanted a big family.

Over the years, it was always difficult for Franklin to find a job. After the war, he found it hard to stick to any one thing and drifted from odd job to odd job. For a while he worked as a janitor in a school, but he was eventually fired for drinking. Franklin says that he began drinking more and more, often staying drunk for several days at a time. His marriage to Rosalie quickly dissolved, and she eventually divorced him.

Franklin was devastated by this and decided to move to Los Angeles, where several of his siblings had already relocated to. He was able to find odd jobs again, sometimes in factories, but he never found a job that stuck, nor did he ever remarry. He dated several women, but nothing was ever “for real” he says. Finally, when he was in his early fifties, he decided to move back to Louisiana to take up farming again, as that was the only thing he thought he was really good at.

At one point, however, an old school friend showed up for a visit, and he convinced Franklin that Chicago was where he should be. After much thought, Franklin decided to take his friend’s advice and once again decided to try his luck in a city. He moved to Chicago and almost immediately got a job at the Sunbeam Lighting Company and found an apartment on the north side. He worked at Sunbeam for eight years and then at another company for three more before he started having health problems and eventually “retired.” He says he didn’t have time for much in the way of hobbies, but he did enjoy fishing, hunting and movies.

Franklin has apparently been living alone all these years until about a month ago when he had some sort of seizure and fell and hurt his leg. He was admitted to a hospital, where he also went through alcohol withdrawal. Apparently the discharge staff at the hospital discovered that his apartment was not fit to live in, as it was filthy and full of roaches, and they were therefore hesitant to release him. They began a search for his family, then, and eventually tracked down Franklin’s daughter, Minnie Jo. She currently lives in Los Angles with her husband and children and is very near her many aunts and uncles—Franklin’s siblings.

Minnie and Franklin’s sister, Hattie, flew in, then, from California to help find a nursing home in which to place him. Though the two of them worked together on his admission, they are at times at odds now, as they are both vying for control of Franklin’s situation.

Meanwhile, though Franklin claims to be unmarried and have no serious girlfriend, a woman by the name of Vera Michaels has been visiting him daily at the nursing home, telling the staff that she is Franklin’s common-law-wife. Franklin’s daughter, Minnie, says that this is ridiculous, that Vera is just “a friend” with whom Franklin sometimes used to spend time. “She has never lived with him,” Minnie claims, and she is not his “common-law wife.” Franklin himself will not clarify any questions regarding his relationship with Vera and gives vague answers when asked about it. When Vera does show up, however, he seems happy to see her.

Franklin is making a somewhat smooth transition to the nursing home. At times he seems confused, but he is happy to spend time with other male residents, usually watching sports on T,V. He also loves bingo. He says he is not anxious now, though he describes himself as being a “worry wart” in the past. He always tried to hide it, he says, and drinking helped. Franklin does not appear anxious or depressed at this time, though he often involuntarily twitches. He says he would like to see his mother and his other daughter, Nellie Jo, before he dies. They both still live in Louisiana and are the only ones left there. The rest of the family has either died off or moved years ago to Los Angeles.

Minnie says she is trying to arrange a way for her mom and sister to come to Chicago to visit Franklin, but she doesn’t know how realistic this is. Neither she nor her sister were ever very close to their father, having very rarely saw him, except for his brief stints of living in Los Angeles and then back in Louisiana before permanently moving to Chicago. Minnie is sympathetic regarding her father’s situation, but she is not overly emotional. “He left when I was two,” Minnie says. “My mom raised me and my sister alone, and that was hard for her.”

When asked about his life, Franklin says it was a good one, though he never really found “a place to hang my hat.” He seems to take everything in stride and doesn’t react to much. “I was a drifter,” he says. “But it wasn’t all bad. There were some good times, too.”

(Originally written: May 1996)

The post “No Place to Hang My Hat” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

August 10, 2017

She Learned to Read Before She Went Blind

Louisa Berger was born on September 5, 1907 in Macedonia. Her parents, Martin Everhart and Liese Buhr were German farmers living in what was once called the Austro-Hungarian Empire in an area that later became Yugoslavia. There were originally nine children in the family, but three of them died of diphtheria. The rest of them worked very hard on the farm and suffered much under the hand of Martin, who was “a mean, cruel drunk,” whom they all hated. They lived in horrible poverty as things in Europe got progressively worse. At some point, Martin decided to abandon his miserable farm and immigrate to the United States, taking the family with him.

Louisa Berger was born on September 5, 1907 in Macedonia. Her parents, Martin Everhart and Liese Buhr were German farmers living in what was once called the Austro-Hungarian Empire in an area that later became Yugoslavia. There were originally nine children in the family, but three of them died of diphtheria. The rest of them worked very hard on the farm and suffered much under the hand of Martin, who was “a mean, cruel drunk,” whom they all hated. They lived in horrible poverty as things in Europe got progressively worse. At some point, Martin decided to abandon his miserable farm and immigrate to the United States, taking the family with him.

Louisa was just a small girl at the time, though she says she remembers the ship. Upon arrival in New York, the Berger family made their way to Chicago, where Martin had a cousin. He was able to find some work in a factory, but after about a year, he took the family to Minnesota, where they worked on a beet farm for many years. Martin eventually abandoned this, too, and again moved them all back to Chicago.

By this time, Louisa was roughly fourteen years old and had received almost no schooling. She got a job in a candy factory in Chicago and worked many hours to bring in money for her family. Louisa describes herself as being very shy back then, but that she managed to make a few friends at work. It was their routine to walk in Humboldt Park every Sunday, and they loved to hear the bands play in the band shell. On one of these Sundays, she met a young man by the name of Charlie Berger, who was also walking in the park with friends. Charlie, Louisa says, was very outgoing and easy to talk to. “Before I knew it,” she says, “I was on a date with him, and I didn’t even realize it!”

Charlie worked as a shoemaker, and the two of them married when Louisa was seventeen. They lived on the north side, and Charlie went to night school to become a realtor. Louisa continued working at the candy factory until she got pregnant. Together they had five children: Charles Jr., Clarence, Carl, Lillian and Irene. Once the children were older, Louisa sometimes worked as a cleaner in the evenings. “Charlie was the love of my life,” Louisa says. They were never separated except for when he served in the army during the war.

Louisa says she led a very simple life and didn’t go out much. “I never wanted to,” she says. She was happy listening to music and was mesmerized when they got a television. Most of her time, though, was spent gardening and baking. Charlie dug up almost the whole back yard for her to plant as a garden, and she often won prizes for her vegetables and flowers. “She was always baking,” says her daughter, Irene. Even after they all left, she would still bake several pies and cakes each week and bring them to church meetings or to the rectory for the priests to eat. She looked forward to Sundays when her two sisters would come over and they would play cards all afternoon.

Having never gone to school, Louisa was basically illiterate for most of her life, something she was very ashamed of. Charlie tried to teach her to read in the early years of their marriage, but it proved difficult for him to find the time between working and going to night school. Louisa, too, was busy with the five children and likewise couldn’t make learning to read her priority. Instead, Charlie took care of everything—all of the bills and finances and correspondences.

It was a particularly crushing blow, then, when Charlie fell off a ladder and died at age fifty-two. Louisa’s children stepped in to help her as much as possible, though most of them were already gone. Carl was still at home, though, and it was he that was successful in finally teaching Louisa to read. Louisa delighted in being able to read the newspaper, but it was short-lived, however, when she began to go blind several years later. She can still see a little bit, but has been declared legally blind and must now use a cane.

Remarkably, however, Louisa has been able to live independently until about two years ago when she turned eighty-nine and began needing more help. Irene, Carl and Lillian, the only children still in the area, tried taking turns going to assist her, but they are themselves somewhat advanced in years now, with various health problems and their own families to worry about. When it got to be too much to constantly go and check on her, they hired a caretaker to come in periodically and even tried adult daycare. Both of these things helped, but they did not prevent her from repeatedly falling when she was alone.

After this last fall, Louisa ended up in the hospital and became very disoriented, which prompted the hospital staff to recommend that she be discharged to a nursing home. Her children were reluctant to do so, but, ultimately, they felt it would probably be for the best considering her history of falls.

Louisa is adjusting to her new surroundings, but she is frequently confused about where she is and often asks for Carl or sometimes even her husband, Charlie. At other times, however, she is very clear and likes answering questions about her past. It is difficult for her to participate in activities because of her poor eyesight. She refers to sit amongst the other residents, however, rather than be alone in her room.

(Originally written: September 1996)

The post She Learned to Read Before She Went Blind appeared first on Michelle Cox.

August 3, 2017

“It’s Not Over Yet”

Britta Driessen was born on September 10, 1909 in Chicago. Her parents were Valdis Ozolinsh, an immigrant from Latvia, and Ebba Ahlstrom, an immigrant from Sweden. Valdis made his way to America alone, and Ebba came across the ocean to live with her sister, who had found work in Chicago. It is not certain how Valdis and Ebba met, but is thought to have been at a dance. They began courting and eventually married. Valdis worked making wooden boxes, and in the early days of their marriage, Ebba cleaned the offices of the gas company in the evenings. After she gave birth to their only child, Britta, however, she stayed home to care for her.

Britta Driessen was born on September 10, 1909 in Chicago. Her parents were Valdis Ozolinsh, an immigrant from Latvia, and Ebba Ahlstrom, an immigrant from Sweden. Valdis made his way to America alone, and Ebba came across the ocean to live with her sister, who had found work in Chicago. It is not certain how Valdis and Ebba met, but is thought to have been at a dance. They began courting and eventually married. Valdis worked making wooden boxes, and in the early days of their marriage, Ebba cleaned the offices of the gas company in the evenings. After she gave birth to their only child, Britta, however, she stayed home to care for her.

The little family lived on the south side, near 5400 S. Kedzie, and Britta was allowed to go to high school at Harrison High. She then went on to attend Morton Jr. College for two years, as well. While she was taking classes there, she worked in the evenings as a telephone operator for the phone company. Valdis and Ebba were extremely proud of their daughter when she finally graduated and began working as a secretary at Western Electric.

Britta very much enjoyed her job as a secretary and made many friends. One evening, the company held a dance for the employees, and Britta of course attended. She was surprised when one of the supervisors, Arthur Driessen, asked if he could walk her home. She said yes, and she even remembers what they talked about that night. He told her many amusing stories of growing up in Chicago with five siblings and how his grandparents had emigrated from Holland. When they reached her front door, he asked if she would like to have dinner with him some evening. Britta accepted, and the two began dating. They eventually married in 1938.

Britta continued working after their marriage, but not long after, there was a reorganization at Western Electric, and Britta was somehow transferred into Arthur’s division. Since there was a company rule which prevented family members working for other family members, Britta saw no choice but to resign. She stayed home and became a housewife, which Arthur seemed to prefer, anyway. They lived in the upstairs apartment above Valdis and Ebba, but when her parents decided to sell the building, she and Arthur decided to buy their own place in Park Ridge.

When the war broke out, Britta took over her cousin’s job at the Café Bohemia. It was supposed to be a temporary job in the office, but it stretched on for many years. She and Arthur never had any children, so it seemed to make sense at the time, especially as Britta enjoyed working. She also loved crocheting, making hook rugs, reading, and music. At one point, she tried taking piano lessons at one point, but she didn’t have enough time to practice, so she quit. She also loved bowling, and she and Arthur joined many leagues over the years. She was very active in the ladies auxiliary of the Elks, and served on the board of various charitable organizations.

When Arthur finally retired from Western Electric, he had to persuade Britta to quit work as well so that they could travel. She gave it up, reluctantly at first, but then threw herself into traveling. Together they went all over Europe and the United States, including Hawaii and Alaska, and even took a cruise.

Arthur and Britta had many happy years together until he died in the late 1980’s. Britta decided to sell the house and move into a retirement community, where she was able to live independently for about eight years. Then one day about a month ago, she woke up to find she couldn’t move her legs and called an ambulance. She was hospitalized for several weeks and then discharged to a nursing home for physical therapy and may yet go back to her home. Britta is a very patient, sweet woman who appears eager to please, but she has not completely acclimated to her new surroundings. She fully believes she is going to return home and concentrates on her physical therapy, often practicing walking with a walker up and down the hallways. “I’ve had a good life so far,” she says, “but it’s not over yet.”

(Originally written: August 1994)

The post “It’s Not Over Yet” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

July 27, 2017

An Obsession With the House on Strong Avenue

Zita Fodor was born on May 12, 1913 in Budapest, Hungary to David Fodor and Terezia Kozorus. It is unknown what type of work David did while still in Hungary, but when he and Terezia immigrated to America, he found work in Chicago as a tool and die maker. Terezia cared for their two children, Zita and Gyorgy (George). It is interesting to note that David was a Lutheran and Terezia a Catholic. Obviously, this did not stop them from marrying, and they raised their children this way, too. Zita followed her mother and leaned toward Catholicism, while George leaned toward being a Lutheran like his father.

Zita Fodor was born on May 12, 1913 in Budapest, Hungary to David Fodor and Terezia Kozorus. It is unknown what type of work David did while still in Hungary, but when he and Terezia immigrated to America, he found work in Chicago as a tool and die maker. Terezia cared for their two children, Zita and Gyorgy (George). It is interesting to note that David was a Lutheran and Terezia a Catholic. Obviously, this did not stop them from marrying, and they raised their children this way, too. Zita followed her mother and leaned toward Catholicism, while George leaned toward being a Lutheran like his father.

When the Fodors first arrived in Chicago, they rented a small apartment on Northwest Highway. Later they rented a place on Strong Avenue, and then finally purchased their own home just a few blocks up from where they had been renting. The Fodors lived on the first floor and rented out the upper floor for all the years that Zita and George were in school.

Zita graduated from eighth grade and then got a job as a nanny for a wealthy family. Sometimes she even traveled with them to their summer home in Michigan. She did this for several years, until her mother, Terezia died of liver cancer. Zita came back home, then, to care for her father and brother and got a job as an assembler in a factory that made televisions and radios. Later she quit to take a job at Switchcraft on Elston Avenue, again as a machine operator.

Zita was very devoted to her father and brother, but when the upstairs apartment became available, she surprised them by announcing that she was going to move into it herself. She would still cook and clean for them, she explained, but she wanted her own space. Not long after that, her brother, George, announced that he was getting married. Zita was extremely upset by this news, not wanting anything else to change, and tried to talk George out of it. When George informed her that he had every intention to go through with the wedding, Zita had no choice but to acquiesce, though she was cold to George’s wife, Marie, for many years after. In fact, says Zita’s niece, Donna, “the two of them never got along,” no matter what Donna’s mother, Marie, did to try to please Zita. “She was a person that hated change,” Donna explains. “It was very stressful for her.”

Zita was further upset when George and Marie announced that they planned to rent an apartment down the street after the wedding. Desperate to keep the family together, Zita offered to move back in with her father so that George and Marie could have the upstairs apartment. George, however, wanted his own place and declined, much to Zita’s disappointment. As it turned out, it wouldn’t have worked anyway, as David remarried soon after as well, and his new wife, Sophia, moved in. Again, Zita was very upset at the prospect of yet another change, and seemed to go out of her way to make life miserable for her new stepmother.

Though she was now the only single one in the family, Zita had no desire to ever get married and often loudly said so. She was fiercely independent and wanted to stay that way, claiming that the idea of marriage was “abhorrent” to her. Her father believed that perhaps she just hadn’t met the right man yet, and set about trying to find his daughter a husband. Eventually he introduced Zita to a young Hungarian immigrant by the name of Elek (Alex) Lukacs whom he knew from work and whom he was very fond of. Elek began to spend a lot of time at the Fodor house and eventually worked up the courage to propose to Zita, who promptly refused him. Her father was angered by this and tried to force Zita to marry Elek, but she refused and remained unmarried and independent her whole life.

One thing that the Fodors all had in common was a fierce attachment to their house on Strong Avenue and which for Zita became almost an obsession.

When Terezia died, David had a will drawn up in which he bequeathed the house on Strong Ave. to both Zita and George. He stuck to this decision even after he married Sophia. So when he died of a massive heart attack and Sophia discovered that she would not get the house, she was furious. There was not a lot of love between she and Zita and George, so she eventually was forced to move out and went to live with relatives.

Zita remained in the upstairs apartment, and she and George rented out the bottom floor. In addition, George decided to honor his father’s last wishes that he, too, bequeath his share of the house to Zita, should he die before her, instead of his wife, Marie. Years later, however, he discovered that Zita had not reciprocated, as she was supposed to have done. He somehow found out that she had in truth left her share of the house to the American Indians, her one true passion in life. Furious, he changed his will and left his share to Marie.

So when George also died of a heart attack, he and Marie’s daughter, Donna, moved into the first floor apartment. Donna eventually married and had two children, and still lives in the little house on Strong Ave. Over the years, she has managed to melt her eccentric’s aunt heart. Donna and her family have grown to love Zita and have been caring for her as she has aged.

Zita eventually retired from Switchcrraft but had little to do to fill her time. She had no hobbies besides reading about American Indians and had few friends. “She’s gotten more and more introverted and eccentric over the years,” says Donna. Her health has continued to get worse, and she has needed dialysis for several years now. Just recently, however, she has refused to have any more dialysis treatments and decided instead to go into a hospice program in a nursing home, as she now has so many problems that Donna cannot handle them all.

Donna has helped her to get settled into the nursing home, bringing her many of her things from home, but Zita is not making the adjustment well. She is depressed and irritable most of the time and will not get out of bed unless forced. She has no interest in the other residents or any of the activities offered. At times she can be pleasant with the staff, but usually she pretends to fall asleep while being spoken to. Donna and her family continue to visit as often as they can, but Zita seems to get no joy even from that.

When asked about her house on Strong Avenue, Zita says she has willed it to Donna and hopes she will never sell it. She says that “it was the first thing we owned in a new country and we were extremely proud of it.”

(Originally written: May 1994)

The post An Obsession With the House on Strong Avenue appeared first on Michelle Cox.

July 20, 2017

Her Favorite Job Was Working in an Ice Cream Parlor

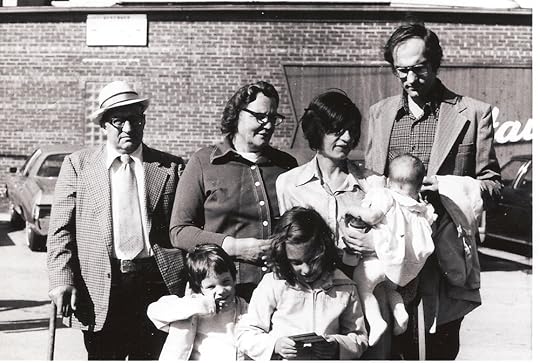

Apolonia Ruzicka (far right)

Apolonia Ruzicka was born on March 30, 1914 in Chicago to Jonas Horacek and Marie Blaha, both immigrants from Czechoslovakia, though they apparently met and married in Indiana. Marie lived with her family in South Bend, where Jonas had also immigrated to and had found a job working for the Studebaker Car Company. The two supposedly met at a church picnic. Marie fancied another boy, actually, but Jonas was persistent in asking her out. Marie finally gave in to him, and the two began dating. They eventually married and lived with Marie’s parents for several years. When the depression hit, however, Jonas lost his job, and the young couple decided to try their luck in Chicago. They found an apartment near Archer and Ashland, and Jonas got a job as a tool and die maker, while Marie cared for their two children, Apolonia and Helena. Eventually, in the 1930’s, the Horaceks had saved enough to buy a two-flat on 31st Street.

Apolonia only went to school through 8th grade and then got a job at the Schulze Baking Company. She was always outspoken and loud, the opposite of her younger sister, Helena, so when she announced that she was marrying Frank Marek, a young man she had met at the White City Ballroom, everyone was shocked. Frank was a quiet man who worked as a mechanic and didn’t seem to mind Apolonia’s strong opinions or outbursts. After they were married in 1935, they moved into the upper apartment of the Horacek’s two-flat and began a family right away.

Their first baby, Rose, lived for only one day. Heartbroken, Apolonia and Frank tried again, and Apolonia finally gave birth to a healthy baby boy, James, in 1939. He was quickly followed by Donald and Leo. Apolonia stayed home to raise her boys until after World War II when she got a part-time job in the mail order room at Sears and Roebuck, working evenings at Christmas-time.

By the 1950’s, Apolonia and Frank had finally saved enough to buy their own house and moved to Cicero. Apolonia got a permanent part-time job working the counter at the Prince Castle Ice Cream Co. and was a favorite among the customers. Tragically, however, in 1958, Frank died of lung cancer at age forty-nine. After his death, Apolonia could no longer pay the bills just by working part time, so she got a full-time job working as a cook at Morton West High School. Her son, Leo, says that this was a particularly hard time for his mother, as she grieved not only for Frank, but for her job as well, as she loved working at the ice cream parlor and had made many friends there.

After several years passed, Apolonia was introduced through a cousin to Peter Ruzicka, who worked as a carpenter’s assistant. The two hit it off and married in 1966. Apolonia sold her house, and she and Peter bought a different one, also in Cicero. They were happy together, says Leo, which wasn’t always the case with his mother. Peter wasn’t the most successful man, Leo explains, but they somehow made each other happy. It was nice period for her three sons, as she wasn’t as emotionally needy and demanded less from them after she married Peter. Sadly, however, they did not have many years together, as Peter died in 1978 of heart disease.

After his death, Apolonia lived alone and enjoyed crocheting, knitting, bingo and gardening and remained an active member of the Slovene Center, volunteering over the years for its many Bohemian picnics and dances. In later years, she also joined the seniors group, The Friendship Club, at her church, Our Lady of Charity. Apolonia, Leo explains, was always “as strong as a horse,” and never really ill. Indeed, she has been able to live on her own, even into her eighties, until very recently.

Several months ago, she was found unconscious on the floor of her home by a neighbor, who quickly called an ambulance. She remained in the hospital for over a month, though the family was never given a straight answer about her diagnosis. None of Apolonia’s sons live in the Chicago metro area, so it was hard for them to get information or to really assess what was wrong with their mother. Leo was finally able to fly in from New York and was shocked to find his mom on the psychiatric ward of the hospital. He also discovered that they had done “exploratory surgery” of her bladder, which had resulted in her being placed in intensive care.

Outraged, the family demanded that Apolonia be released back to her home, which she was, with the help of a caregiver. After only a few days, however, she was taken back to the hospital due to various complications. The hospital then discharged her to a nursing home, where she is making a difficult transition. She is angry and complaining most of the time. Leo explains that she has always been this way and consequently has had trouble in her latter years making and keeping friends. “Since she turned eighty,” Leo says, “she’s definitely gotten worse.” According to him, her depression and irritability has increased, and she has lost interest in a lot of her hobbies.

Predictably, then, Apolonia does not seem to so far enjoy any of the home’s activities and does not seem interested in forming new relationships. When the staff attempt to interact with her, she either shouts “get out!” when they enter the room, or she pretends to fall asleep while they are talking to her. It is hoped that she can eventually acclimate, especially as all three of her sons are unable to visit on a regular basis.

(Originally written: July 1994)

The post Her Favorite Job Was Working in an Ice Cream Parlor appeared first on Michelle Cox.

July 13, 2017

A Life Worth Living

Jan and Tekla Guzlowski, New Year’s Eve, 1958, Chicago

This week’s Novel Notes is a special edition! Author, John (Zbigniew) Guzlowski, was gracious enough to share with me the story of his parents’ fierce struggle to survive in war-torn Poland, their almost miraculous meeting, and their subsequent epic journey to these shores in hopes of building a better life.

John’s parents were Jan Guzlowski and Tekla Hanczarek.

Jan was born in December of 1920 in a small village north of Poznan where he and his brother lived with his aunt and uncle, who were farmers. Jan’s parents and little sister had died of tuberculosis, rendering him and his brother orphans until his aunt and uncle took them in to help on the farm. To John’s knowledge, Jan never went to school, but he taught himself to read well enough to follow along in the prayer book, though he never learned to write.

When the Germans invaded Poland, the Nazi’s began pushing from the west in an attempt to remove the Poles from their land so that it could eventually be repopulated by German citizens. Jan and his brother, like 50,000 others, were sent to Buchenwald in East Germany, where they became a slave laborers. John remembers his father’s terrible description of the Buchenwald camp, which was a huge enterprise, consisting of factories, farms and many sub camps. Jan was rotated through various factories and farms in his five years of captivity and was even conscripted towards the end of the war to dig out German citizens from the rubble once the Allies began bombing German cities.

John explains that there were over 800 slave labor camps with an estimated twelve to fifteen million slaves working in them and that one in six Polish people died in the war. His father managed to survive the war, but just barely. Near the end of the war, Jan was alive, but weighed only approximately seventy pounds. As the Allies pushed forward, Germany attempted to empty as many camps as they could in an attempt to destroy any evidence of war crimes, so in April, 1945, a month before the end of the war in Europe, Jan and his fellow prisoners were sent on a death march, headed west.

They didn’t get far, however, before coming upon another camp, which had also been abandoned of any guards. Women prisoners stood along the fence, looking out at the haggard corpses walking by in their striped uniforms. One of these prisoners was John’s mother, Tekla.

Tekla was born in November 1922 in south-eastern Poland, near Lvov, which had once been part of the Ukraine. Her father was a forest warden and her mother cared for their eight children, of which Tekla was one of the youngest. John says that his mother often told him wonderful stories of what it had been like growing up in a little cottage in the woods and how happy they had been in that life.

Living in the portion of Poland claimed by Russia, the war came later to Tekla than it had to Jan, that is until Germany turned on Russia and invaded them, too. The Germans then hired Ukrainian “killing squads” to cleanse eastern Poland as well. Some Ukrainians were directly enlisted into the German army, though a separate Ukrainian SS was also formed. Before long, Tekla’s father and all of her siblings, but one sister, Genja, were taken by the Ukrainians and either killed or sent to a slave camp. Tekla, her mother, Genja, and Genja’s baby managed to somehow to escape this first sweep. They weren’t so lucky the next time, however, when the Ukrainians returned. Tekla broke through a glass window and hid in the woods, watching as soldiers killed her mother, raped and killed Genja, and then kicked Genja’s tiny baby to death. Eventually, they discovered Tekla, too, and after brutally raping her, took her with them to a camp. Like Jan, Tekla was forced to work in the camps for years, witnessing the most horrific brutality and crimes.

As was the case in Buchenwald, towards the end of the war, the guards at her camp also abandoned their post, hoping to escape the country before the Allies inevitably arrived. So when Tekla and her fellow prisoners stood at the fence of their camp watching the skeletal survivors of Buchenwald walk past them on their death march, they feebly called to them and invited them in. The stragglers, including Jan, saw no reason to keep going, knowing they were near death anyway, so they abandoned their walk to meet these tattered, emaciated women.

In later years, Tekla often enjoyed retelling the story of Jan’s approach to her that day. Even in his shrunken seventy-pound state, Jan apparently took her hand and kissed it with such gentle tenderness and profound respect, that she assumed he was some sort of nobility, possibly a prince or a count. John explains that for both of his parents, after the abject suffering and brutality that they had been through, it was a moment of sublime humanity and grace, which sealed them together for the rest of their lives. Jan later described it as follows, “We all had something to eat and then got married.” To an outsider, this makes no sense, but to those living in that awful moment, it was perhaps the most logical thing that could have happened, as if there could be no other ending to that horrific chapter in their lives but a wedding, a coming together of two souls, as if they were the only two souls left.

However it is explained, Jan and Tekla were married and spent the next six years of their life in an Allied refugee camp, during which time they had two children, Donna (Danusa) and John (Zbigniew). They considered returning to Poland, but they were afraid to. The United Nations was trying to get people to go back to their native countries, offering people money to help them start over, but Jan and Tekla had heard terrible stories of people being shot by the Russians when they tried to get off the trains. Also, they had gotten word from Tekla’s brother, Walter, who had also managed to survive the war, that when he tried to return to their village in Poland, the Russians who were waiting there shipped him off to Siberia. Fearing that something like this might happen to them, Jan and Tekla decided to stay in the camp and wait for a sponsor in America.

Finally, when Jan was 31 years old, the Guzlowskis got word that a farmer in New York was willing to sponsor them, and they were eventually allowed to sail for the United States. When the little family arrived, they were taken to a farm just outside of Buffalo, NY where they worked for a year, one of their main jobs being to harvest strawberries. It was hard work, but nothing compared to what they had been through. John says that even though he was only three and his sister five, they were expected to work, too.

After their year was up, John says his parents were eager to move on, Jan saying that he never wanted to do farm work ever again in his life. It so happened that a friend he had made in Buchenwald was living in Chicago and wrote to Jan, encouraging him to come to Chicago where there were plenty of factory jobs for good wages. Jan and Tekla decided to follow this advice, and headed west for Chicago.

Jan was indeed able to almost immediately get a job in a factory that made string, but finding a place to actually live was harder. When they first arrived in Chicago, the Guzlowskis made their way to Wicker Park and lived in an apartment with four other families. They stayed there for a few weeks and then moved to different apartment with only three families, then one with two families, then even to a storage unit in the basement of an apartment building. John says that in those early years, they moved constantly from apartment to apartment, sometimes only staying in a place for a week or two, always searching for something better.

It was difficult, though, because they were looked down upon because they were “DP’s”—displaced persons—and often faced “No Polish wanted” signs in apartment windows next to “For Rent” signs. John says that he fondly remembers his long walks with his father through the neighborhoods of Wicker Park, Humboldt Park and Logan Square, looking for a new place to live. Even the existing Polish population, which had come over in previous generations, tended to shun the DP’s, whom they saw as degenerates and probably corrupt from their years in camps, both under the Germans or the Allies. Likewise, they did not appreciate that the DP’s would work for any wage, thereby threatening the status quo and their own jobs.

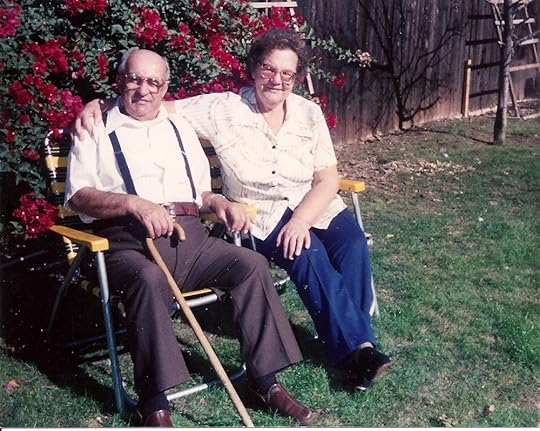

Jan and Tekla Guzlowski with John, Donna and grandchildren in 1979 outside of the Old Warsaw restaurant, Chicago

Amazingly, after only three years of living in America, Jan and Tekla had saved enough money to buy a five-unit building on Potomac in Humboldt Park. John describes it as a three-unit building separated by a small yard from a two story house in the back. It was a run-down structure, with no central heating, warmed only by kerosene heaters, but they owned it, something of which they were naturally very proud. John remembers that to save money, his parents used to block of all of the rooms in their unit except the kitchen and one bedroom, where they would all sleep together. John also remembers that one particular year he was excited when spring rolled around because it meant that they would soon unblock the front living room and he would be able to watch television again. He was crushed, then, when they found that it had gotten so cold in the front room over the winter that the TV tubes had frozen and shattered.

The Guzlowskis lived in this building from 1954 to 1960, when they sold it and bought a six-unit building on Evergreen where they lived until 1975. The neighborhood then began to get rough at about that time, so they moved to a two-flat on Diversey, near California, and from there to a single family house on Diversey and Rutherford.

Jan continued working in various factories, though he spent the most years at Resonite, which made the hardened, protective cardboard covers for TV and radio tubes. He worked double shifts for most of his life, never taking vacations or holidays off, reveling in the time-and-a-half or double pay that working on such days afforded. Tekla in turn worked night shifts, so that someone was always home with John and Donna. She worked for a time at the Motorola factory on Kimball, and then at the Helene Curtiss factory on North Ave. In the mid 1960’s, she quit factory work and started cleaning office buildings downtown.

John says that his parents’ life was mostly consumed with work and that they had no real hobbies or other interests beyond socializing with other Polish people, most of them DP’s who had shared the same sordid chapter in their lives. Friday and Saturday nights were the big social nights when they would gather with their friends, rotating houses each week, enjoying Polish food and drinks. Jan’s friend, Bruno, from Buchenwald, would often play on his mandolin. But instead of playing perhaps Polish folk tunes, he instead played Country and Western songs, which he had learned from an American soldier while in an Allied camp. John always found it amusing to hear “Red River Valley” sung in Polish to a mandolin.

Besides socializing, his parents spent any free time walking in the Chicago parks, which they loved, particularly Humboldt Park, often bringing a picnic along. Walking down by Lake Michigan or wandering through Lincoln Park Zoo was also a favorite. Though Jan had a fear of water, both he and Tekla loved sitting and watching the lake, and in their later years they went almost every day to Diversey Avenue beach, where they would often meet up with other refugees and talk. They enjoyed watching music shows on TV, such as Lawrence Welk, and Jan eventually took up gardening again, growing beautiful flowers and even bringing some of them into the house over the winter to keep them alive.

Both Jan and Tekla retired in their mid-fifties, their bodies broken from the many years of hard labor they had endured. Jan had severe emphysema, and Tekla had many health problems, including heart trouble and arthritis. Finally, in the mid 1990’s, Jan’s doctor advised them to move to Arizona where it would be easier for him to breathe.

So, once again, Jan and Tekla picked up stakes and moved west to Arizona, where they found an apartment near other Polish people and began to be a part of a whole new community. When Jan died in 1997 at age seventy-seven, John and Donna, both still in Illinois, thought for sure Tekla would return to Chicago and urged her to do so, but she would not. She had formed a new community there and didn’t want to leave. Even after battling two different types of cancers, she was able to live independently, with the help of a cleaning lady and Meals On Wheels, until the very end, when she died at age eighty-three.

Donna still lives in the Chicago suburbs with her family and is the keeper of many of the family stories, and John, living in Charleston, Il. is a retired academic and an author of many books of poetry, non-fiction and fiction, many of them featuring his parents’ story.

Jan and Tekla are not only an amazing example of the human will to survive, but a beautiful testament to human desire to love. May their story, and the stories of thousands of others like them, never be forgotten.

Jan and Tekla at their home in Sun City, Arizona, 1995

John Guzlowski’s writing appears in Garrison Keillor’s Writer’s Almanac, Rattle, Ontario Review, North American Review, Salon.Com, and many other journals here and abroad. His poems and personal essays about his Polish parents’ experiences as slave laborers in Nazi Germany and refugees making a life for themselves in Chicago appear in his memoir Echoes of Tattered Tongues (Aquila Polonica Press). Echoes of Tattered Tongues is the recipient of the 2017 Benjamin Franklin Poetry Award and the Eric Hoffer Foundation’s Montaigne Award. He is also the author of three novels.

John Guzlowski can be reached as follows:

Blog, Echoes of Tattered Tongues: http://lightning-and-ashes.blogspot.com/

Amazon: amazon.com/author/johnguzlowski

Twitter: @johnguzlowski

Facebook: http://bit.ly/2tfbh1Z

The post A Life Worth Living appeared first on Michelle Cox.

July 6, 2017

Married at Fifteen

Hai Bo Song was born on October 5, 1914 in China to Jie Fu Song and Jing Fen Chan, who were farmers. It is unclear how many siblings Hai had, as cousins in China were also referred to as brothers and sisters. Hai’s youngest son, Ning, explains that at that time in China, it was common for most of the people in a whole village to be related to each other. “That’s why two people from the same village were never allowed to marry.” In those days, Ning says, “people were very much tied to the land, and a family’s wealth and worth was determined by the amount of land they owned.” Thus, it was the custom for the man of the family to travel to the United States to work and to save money for a period of ten to fifteen years and then come back and buy another parcel of land to increase the size of the farm. He would then send his oldest son to America to begin another ten- to fifteen-year stint.

Hai Bo Song was born on October 5, 1914 in China to Jie Fu Song and Jing Fen Chan, who were farmers. It is unclear how many siblings Hai had, as cousins in China were also referred to as brothers and sisters. Hai’s youngest son, Ning, explains that at that time in China, it was common for most of the people in a whole village to be related to each other. “That’s why two people from the same village were never allowed to marry.” In those days, Ning says, “people were very much tied to the land, and a family’s wealth and worth was determined by the amount of land they owned.” Thus, it was the custom for the man of the family to travel to the United States to work and to save money for a period of ten to fifteen years and then come back and buy another parcel of land to increase the size of the farm. He would then send his oldest son to America to begin another ten- to fifteen-year stint.

Though they were already considered somewhat well off, Hai’s family was no exception to this practice, with Jie and several of his sons working in America in shifts. When Hai was fifteen, her parents arranged for her to marry Wu Hong Lim, who had been working in America with his father from age 12. When he turned eighteen, he was sent back to China to marry the girl his parents had selected for him, Hai Bo Song. He stayed long enough for Hai to give birth to a healthy son, Tai, and then returned to America to complete his stint.

Wu stayed in America beyond the normal fifteen years due to WWII. After the war ended and the Communists moved in to take over China, thousands of people fled, trying to get to America to be reunited with their fathers or husbands. Hai and Tai were among these and managed to make it out of China. They eventually met up with Wu in Chicago. There, Hai and Wu had two more sons, Shi and Ning. Tai was well over fifteen by the time Shi was born, but a fifteen-year gap between siblings was obviously common for Chinese families at the time. Wu and Hai lived for many years in Chicago’s Chinatown, with Wu working as a waiter and Hai eventually getting jobs in factories. In the 1960’s, the family moved to the north side of Chicago.

Ning says that Hai is a quiet woman and easily pleased. She enjoyed socializing with her Chinese neighbors when they lived in Chinatown and has never really learned to speak English well. She also liked crocheting, playing Mahjong, gambling, and watching Chinese soap operas. She only left Chicago once, and that was to go to Boston for a relative’s wedding. She also enjoyed going to Chinese funerals. Once they moved to the north side and had a small plot of land, she also took up gardening, something she hadn’t done since she her days in China.

Tai and Shi eventually married and moved to the suburbs, but Ning has remained all these years with his parents, caring for them as they aged. Except for a hairline fracture in her back after she fell in 1972, Hai has remained in good health until recent years. In the early 1990’s, Hai developed Shingles and, according to Ning, has slowly “gone downhill” since then. Ning says that whenever the weather changes, she still has twinges of pain. Two years ago, she fell again, this time breaking her hip, but she eventually recovered, slowly but surely. Ning says that his mother is amazingly strong, both physically and mentally, and that she has always been independent from a young age out of necessity. “She never gives up,” Ning says.

At the time that Hai broke her hip, however, Ning was also struggling in having to care more for his father, Wu, who was progressively becoming more confused. He was repeatedly found wandering in the neighborhood, lost, with the police bringing him back to the house nine times in the space of a month and a half. The police suggested that perhaps Wu be admitted to a nursing home, but, Ning says, “I couldn’t do it.” It would have gone completely against Chinese culture, Ning explains, in which the “children are obligated to care for their parents.” In an effort to keep Wu at home, Ning instead put high locks on the doors to keep Wu from wandering. This only seemed to incense Wu, however, and caused him to become combative. He even once drew a knife. This was the last straw for Ning, already worn out from caring for his mother. He took Wu to a doctor, who in turn diagnosed him with Alzheimer’s and insisted that he be admitted to a nursing home, which Ning reluctantly agreed to.

Ning was hopeful that he and his mother, slowly improving now, could get back to some sort of routine when she suddenly collapsed one day in severe pain. Ning called an ambulance, and it was discovered that part of her intestine had ruptured. During the resultant emergency surgery, the doctors further determined that she was also suffering from colon cancer.

Hai was accordingly discharged to a nursing home with hospice care, though not the same home where Wu is a resident. Ning thought it best for them to not be in the same place, as in their later years they had become very argumentative. Also, Ning reasoned, they would not be together, anyway, with Wu being on a separate Alzheimer’s unit. Ning wanted Hai to be in a smaller facility that could hopefully give her more attention. Tai and Shi and their families have started to become more involved and visit often, though it is Ning who continues to come twice a day, every day.

Hai seems accepting of her prognosis and seems to take her fate in stride. She is very alert, though she can only communicate through an interpreter. She says that she is not afraid to die and that she has lived a good life. She does not seem to enjoy sitting with the other residents, and prefers to sit alone in her room, waiting for Ning to come each day.

(Originally written: November 1995)

The post Married at Fifteen appeared first on Michelle Cox.

June 29, 2017

A Secret War-Time Affair

Adam Cerny was born on January 25, 1911 in Chicago to Teodor Cerny and Cecilie Klimek, both immigrants from Czechoslovakia. Teodor and Cecilie grew up in the same town in Bohemia and married there. Teodor worked as a farm laborer, and Cecilie cared for their four sons: Simon, Tomas, Radovan and Othmar. At some point, the Cernys decided to start a new life in America and made their way to Chicago, where another son, Adam, was born. Teodor found work in a warehouse for Marshall Fields and then got a job for a company that delivered coal, wood and ice. Ice was always the steadiest, Adam remembers.

Adam Cerny was born on January 25, 1911 in Chicago to Teodor Cerny and Cecilie Klimek, both immigrants from Czechoslovakia. Teodor and Cecilie grew up in the same town in Bohemia and married there. Teodor worked as a farm laborer, and Cecilie cared for their four sons: Simon, Tomas, Radovan and Othmar. At some point, the Cernys decided to start a new life in America and made their way to Chicago, where another son, Adam, was born. Teodor found work in a warehouse for Marshall Fields and then got a job for a company that delivered coal, wood and ice. Ice was always the steadiest, Adam remembers.

When the Cernys first arrived in Chicago, they lived in an apartment near Milwaukee and Grand, but later moved to a nicer place on Cornelia. Finally, in 1922, they had saved up enough to buy their own house on Hutchinson, which is where Adam has subsequently lived his whole life.

Adam graduated from Lane Tech high school and immediately got a job as a mail clerk with Lansing B. Warner, Inc., a specialized insurance company for the food industry. He was later promoted to purchasing clerk, and the only time he was ever absent from work was during WWII. When the war broke out, he joined the army and was stationed in Italy and Africa, serving from February 1942 until November of 1945. When he came home, he found his job at Lansing waiting for him, and he remained there until he retired at age fifty-five. From there, he got a job at Grant, Wright and Baker, which was an advertising firm. He began as a purchasing clerk, but to fully occupy his time, he also started proofreading the ads on the side in his spare time. He remained there until he retired again at age seventy-seven.

Adam never married, though his nephew, Frank, says that there has always been a story in the family that Uncle Adam had a love affair while he was stationed in Italy. It was something that he never spoke of, merely hinted at. One Christmas, however, when they had all been drinking heavily, Adam told Frank cryptic bits of the story, saying that he had fallen in love during the war with an Italian woman whose husband was also off fighting in the war. Apparently, Adam had kept up a correspondence with her for several years, during which he begged her to come to the United States, but she would not, and eventually her letters had stopped coming altogether. He never heard from her again, he told Frank, and never had a way of finding out what might have happened to her. Frank says that he has tried to bring up the subject several times over the years, but Adam does not want to talk about it, saying “that’s all in the past now” and almost seems embarrassed that he ever mentioned it in the first place. Frank urged him on try to find someone else, but Adam said there would only ever be one woman for him. “Anyway,” he apparently told Frank, “someone has to stay home” to care for Teodor and Cecilie, as all of his brothers had already married and moved away.

Thus, Adam remained at the house on Hutchinson and dutifully cared for his parents as they aged. Teodor eventually died at age eighty-four of what was probably prostate cancer, and Cecilie five years later. He was a good caretaker, Frank says, and even gave Cecilie her insulin shots in the later years. Adam continued, then, to live alone until the early 1990’s when he fell and broke a hip. He spent several weeks in the hospital, during which time it was also discovered that he had prostate cancer. He was determined to go home, but Frank convinced him to go to a nursing home, at least for a time. Adam agreed to come temporarily, though Frank and the rest of the family see it as a permanent move, given his prognosis.

Adam, for his part, says “there’s no place like home,” but seems to enjoy his new surroundings none-the-less. He is extremely alert and aware and is cognizant of the inner workings of the home itself and the various roles and schedules of the staff. He enjoys sitting with other male residents to watch any type of sports game, except soccer, which he says he “has no time for.” His favorite thing to do at home, when he wasn’t working, was to potter about the yard and have a beer with his friends. He religiously read the Chicago Tribune daily from “cover to cover” and still does, even here at the home, and loves doing the crossword puzzle, a lifelong habit.

Adam is a very pleasant, down-to-earth man who is not easily ruffled and seems to be taking his fate in stride. He believes in God, he says, but has never had much time for church. He seems fully aware of his terminal prognosis, but says he is determined to enjoy what time he has left.

(Originally written: July 1994)

The post A Secret War-Time Affair appeared first on Michelle Cox.

June 22, 2017

“He Wasn’t the Man I Married”

Grace Phillips was born on October 3, 1922 in Alder Point, Nova Scotia to Warren McAndrews and Mary Jane Wilson, both of whom were Scottish Canadians. Warren was a coal miner, and Mary Jane cared for their ten children: Margaret, Grace, Leon, Calvin, Rosemary, Dale, Katherine, William, Mattie and Lillie. Lillie was actually the daughter of Mary Jane’s best friend who had died during childbirth. Lillie’s father was overwhelmed and distraught and had no use for the baby that had somehow lived, so Mary Jane took her and raised her as their own.

Grace Phillips was born on October 3, 1922 in Alder Point, Nova Scotia to Warren McAndrews and Mary Jane Wilson, both of whom were Scottish Canadians. Warren was a coal miner, and Mary Jane cared for their ten children: Margaret, Grace, Leon, Calvin, Rosemary, Dale, Katherine, William, Mattie and Lillie. Lillie was actually the daughter of Mary Jane’s best friend who had died during childbirth. Lillie’s father was overwhelmed and distraught and had no use for the baby that had somehow lived, so Mary Jane took her and raised her as their own.

When Grace was about twelve or thirteen, the McAndrews decided to move to Chicago in hopes of a better life. Warren, desperate to get away from the mines, found a good job here as a carpenter. Grace only completed seventh grade and then stayed home to help her mother with their large family. In her teens, she got a job at a factory that made decorative braiding, a skill Grace became quite good at. It was one of the things, actually, that attracted her future husband, Gordon Phillips, to her. When he first met her, he noticed that even though the clothes she wore were simple and not expensive, she made them look elegant by adding braiding.

Grace and her sister, Rosemary, had the same set of friends and often socialized in the big dance halls around Chicago. It was at one such place, the Merry Gardens, that Grace was introduced to a mutual friend, Gordon Phillips. Gordon and Grace started dating and fell in love, but when the war broke out, Gordon immediately joined up. They decided to get married before he shipped out, so Grace bravely traveled to North Carolina where Gordon was stationed to get married, as he was not allowed to leave the base. Shortly after the wedding, Gordon was indeed shipped out to Europe, so Grace returned home to live with her parents and wait for Gordon to come back. She got a job in the meantime at a factory that made gold rings.

Unfortunately, the war did not go well for Gordon. He was captured by the Germans and spent eight months as a prisoner of war. When he finally came home, he was only 110 pounds. He got a job right away, however, in a tool and die factory, and Grace quit her job to be a housewife and then a mother. Together, she and Gordon had three children: Rosemary, Carol and Steven. They began their married life in a small apartment on the north side and moved from place to place until they settled in an apartment on Diversey, where they remained together until 1970.

Grace and Gordon’s marriage, however, was not a happy one. “He was never the same” after the war, Grace often said. “He wasn’t the man I married.” Grace tried hard to make it work, but Gordon began drinking more and more until she could no longer take it. Gordon moved out and eventually remarried, and Grace remained in the apartment with Steven, the only child still at home. Grace got a job as a purchasing clerk for the Society for Visual Education in Chicago and managed to support herself and Steven over the years.

Grace’s daughter, Rosemary, remembers Grace as being very submissive to Gordon, who suffered from severe mood swings, among other things. “But when she divorced him,” Rosemary says, her mother “became much more independent.” She went out more and became more social. She had always enjoyed reading, embroidering and croqueting, but she now took up walking, sometimes spending her entire day off out walking through the city. Once Steven got married and moved away, she likewise got more involved in her church, St. Bartholomew and volunteered many hours to the St. Vincent De Paul society.

In 1990, Grace decided to move to a new apartment, but after only two years in the new place, she was robbed twice and mugged once on the street. She decided at that point to retire from her job and move to a better apartment on Patterson. Grace continued with her hobbies and volunteering, though, until February of 1994, when she discovered that Gordon had died. He had had a quadruple bypass the year before and had been recently diagnosed with prostate cancer. While in the hospital having surgery to remove the cancer, there was apparently a mistake made that caused Gordon his life. His heart had begun to beat irregularly, so he was given a medication to slow it down a bit. Tragically, however, the nurse on duty accidentally administered 10x’s the amount prescribed, which stopped his heart completely, and he died.

Though Grace and Gordon had lived for years and years apart with little or no contact between them, Grace was very affected by Gordon’s death and went into a depression after he died. Rosemary believes that her mother never really stopped loving her father. According to Rosemary, Grace never once spoke negatively of their father, despite all that had gone on between the two of them. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that just two months after Gordon’s death, Grace suffered a stroke, which left her right side paralyzed. She spent five weeks in the hospital recovering. When it was time for discharge, her family suggested giving a nursing home a try. Grace agreed to this and believes her stay at the home to be temporary, though her daughter, Rosemary, confirms that she and the rest of the family feel it is a permanent move, as it is impossible for her to care for herself now.

Grace seems in relatively good spirits and has a great sense of humor, but she is very frustrated by her inability to effectively communicate because of the stroke. Her speech is severely limited. She can get simple things across, but relies on her daughters to give more lengthy explanations to the staff whenever they come in to visit, which is somewhat problematic for all concerned and for obvious reasons. Grace has been successful, however, in communicating to the staff that she wants to be up and about in her wheelchair and not lying in bed. Though she cannot really talk to the other residents, she prefers to be sitting among them and is eager to participate in activities if a staff member or a volunteer can sit and help her.

(Originally written May 1994)

The post “He Wasn’t the Man I Married” appeared first on Michelle Cox.