Michelle Cox's Blog, page 32

June 15, 2017

Her Dreams of Being a Nun Were Dashed!

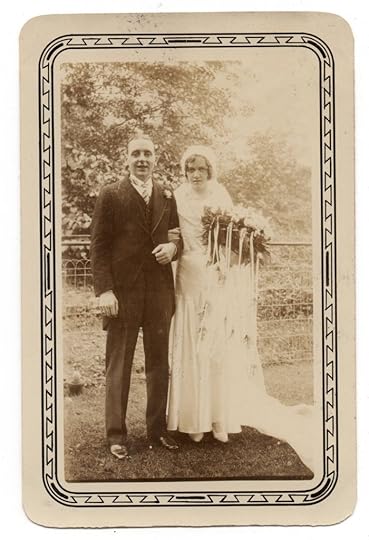

Nedda Scarsi was born on April 7, 1910 in Chicago to Giovi and Fara Mancus, both of whom had immigrated to the United States from Sicily as a newly married couple. Giovi made a living selling produce from a cart he pushed from street to street, and Fara cared for their seven children, of whom Nedda was the youngest. Nedda attended school until seventh grade and then quit to help her mother at home. From an early age, Nedda was a very religious child and dreamed of becoming a nun. Fara wouldn’t hear of it, however, Giovi having already passed away, and insisted she get married instead. When Nedda retorted that she didn’t know any men and didn’t really have an opportunity to meet any, Fara arranged for her to marry the son of some Sicilian friends. For a while, Nedda tried to resist, but, finally, when she was twenty years old, she agreed to marry Vincenzu “Vince” Scarsi.

Nedda Scarsi was born on April 7, 1910 in Chicago to Giovi and Fara Mancus, both of whom had immigrated to the United States from Sicily as a newly married couple. Giovi made a living selling produce from a cart he pushed from street to street, and Fara cared for their seven children, of whom Nedda was the youngest. Nedda attended school until seventh grade and then quit to help her mother at home. From an early age, Nedda was a very religious child and dreamed of becoming a nun. Fara wouldn’t hear of it, however, Giovi having already passed away, and insisted she get married instead. When Nedda retorted that she didn’t know any men and didn’t really have an opportunity to meet any, Fara arranged for her to marry the son of some Sicilian friends. For a while, Nedda tried to resist, but, finally, when she was twenty years old, she agreed to marry Vincenzu “Vince” Scarsi.

Vince worked at the Galvin Manufacturing Corp. factory, which later changed its name in the 1940’s to Motorola. Nedda stayed home and took care of their four children: Sonia (Sunny), Concetta (Connie), Antonio (Tony), and Francesca (Frannie). Sunny and Connie were born very close together right after Nedda and Vince married, but then ten years passed before Nedda became pregnant with Tony. Another five passed before she became pregnant with Frannie, thus the Scarsi children were spread across a large space of time.

Shortly after Connie was born, Nedda’s mother, Fara, passed away, which caused a rift in the family that still exists today. Apparently, by the time Giovi had passed away, he and Fara had managed to save enough money to buy three, three-flat buildings, which they rented out, and had considerable savings stuffed in mattresses around the house, having no trust in banks. When Fara, too, passed away, the seven children then began fighting over the assets. Oddly, the four brothers aligned themselves against Nedda and her two sisters. The finances were eventually somehow sorted out, but each “side” refused to forgive the other and went their separate ways. Thus, Nedda has never once spoken to any of her brothers since that time.

Nedda tried hard to make her own life with Vince, but they never really got along. In fact, they fought constantly. To make matters worse, in 1953 when Frannie, the youngest, was just five, Vince was diagnosed with nose cancer. The stress in the house worsened as a result, and the fighting intensified. Finally, after two years of this, Vince and Nedda separated. Nedda got menial labor jobs and went on welfare to support herself and the kids, but she became severely depressed. Eventually she was fired from her job and stayed in bed all day, sleeping constantly, forcing Sunny and Connie to care for both Tony and Frannie.

In 1962, Vince passed away, lifting some sort of burden from Nedda, and she began to “come around” again, says Tony. By the time Frannie graduated from high school and moved out of the house, Nedda began to “perk up” and would finally leave the house and do errands. Her favorite activity was to clip religious articles from the newspaper and put them in a box. She also loved watching television, especially magic shows. Eventually, Frannie got married and had a son, Frank, whom Nedda grew very close to and who became her favorite. Often, Nedda would take the two buses required to get to Frannie’s house so that she could help watch him. For years, she went to Frannie’s every Sunday for dinner. She never really had many hobbies except collecting religious artifacts. She only went on two trips in her lifetime: once to San Diego to see Sunny and once to Kentucky to visit Connie and her family.

As the years went along, Nedda was able to live independently until her mid-eighties when she began to experience a lot of problems with her bowels. Tony and Frannie arranged to take her to the hospital, where she had many tests, all of which were inconclusive. She was released back to her home, but she continued to get worse. Tony and Frannie took her back to the hospital, and it was determined that her colon was no longer working but that she was not a candidate for surgery. She was accordingly admitted to a nursing home, but after only a few days, she required emergency surgery for a colostomy. During the surgery, it was also discovered that she was suffering from a massive hernia, which was pushing all of her internal organs up into her chest cavity, creating breathing problems. Despite the doctors’ initial misgivings about the surgery, it was a success, and Nedda was able to return to the nursing home.

Tony and Frannie are both amazed that their mother is now more optimistic and outgoing than she has been in years. At times she is very disoriented and confused, though, often telling the staff that her husband, Vince, will be by soon to pick her up. At other times, she seems focused and has asked Frannie to bring all of her religious items from home so that she can hang them up in her room.

“She never got over wanting to become a nun,” Tony says. “She talked about it constantly,” so much so that they were all surprised that she didn’t enter the convent when Vince finally passed away. By that time, though, she was isolative and depressed, and when she did start to “come out of it,” she focused all of her energy, for some reason, on her grandson, Frank. In fact, she never spoke of being a nun again, but continued to clip religious articles from the newspaper or magazines all the way up to her first hospitalization.

Nedda is a very easy-going woman, but does not yet interact with the other residents. The staff are attempting to find some activities, such as saying the rosary, which might appeal to her.

(Originally written December 1995)

The post Her Dreams of Being a Nun Were Dashed! appeared first on Michelle Cox.

June 8, 2017

Unwilling to Give His Brother the Biggest Share of the Catch

Cal (Caolan) Maguire was born on May 21, 1916 in Ireland to Caolan Maguire, Sr. and Mary Brady. Caolan, Sr. was a fisherman in their little village by the sea near Balbriggen, and Mary cared for their thirteen children, of whom Cal, Jr. was the youngest. Cal went to school until about seventh grade when he quit to become a full-time fisherman with his father and brothers.

Cal (Caolan) Maguire was born on May 21, 1916 in Ireland to Caolan Maguire, Sr. and Mary Brady. Caolan, Sr. was a fisherman in their little village by the sea near Balbriggen, and Mary cared for their thirteen children, of whom Cal, Jr. was the youngest. Cal went to school until about seventh grade when he quit to become a full-time fisherman with his father and brothers.

When he was eighteen, Cal joined the Irish Merchant Marine. After five years, though, he went back to being a fisherman with his father and brothers. Sometime in his twenties, he married a girl he had met at a dance in the next town over, Skerries, by the name of Mary Brady, the same name as his mother, though she was apparently no relation. After their marriage, there were thus two sets of Cal and Mary Maguires living in the same area, which apparently sometimes caused confusion with the post.

Cal and Mary lived for one year with Mary’s parents until their first baby, Aidan, was born. By that time, they had saved up enough to get their own small house, where two more sons were born, Fergus and Keefe. Cal and Mary may very well have repeated their parents’ life, had not an incident happened one evening when Cal and his brothers were coming in from a day’s fishing. Their father having recently passed away, Cal’s oldest brother, Sean, declared that he should now be getting their father’s portion of the catch, which, of course, had been the biggest portion. Cal and his brothers protested, but Sean was adamant. Finally the other brothers agreed to let Sean have the biggest part of each day’s catch, but Cal would not be reconciled.

He was so infuriated by the situation that he wrote to his sister, Eileen, who was living in America with her husband, and asked if she would make a place for him. While he waited to receive word back, he shunned his brothers’ company and fished on his own until a letter from Eileen finally came. Yes, she told him, he could come and live, but there was not room for all of them. So after much debate, it was decided that he would leave Mary and their three sons behind while he went to try to make a new life in America.

Cal arrived in Chicago in the early 1950’s and first worked at a molasses factory. He could not contain his love for the sea, however, and a year later was able to find another job “on the boats” working for the Great Lakes Towing Co. where he continued to work until 1981. Just as he had promised, he eventually saved enough to get a house on Carmen Avenue on the city’s northwest side and was finally able to send for Mary and the boys. Cal became very involved in their parish, Transfiguration, which was right down the street from where they lived. He had many other past times as well, including playing the accordion in various neighborhood bars and pottering about the house and yard. He was an expert gardener and even won the neighborhood prize one year for his flowers.

In 1982, a year after he retired, his son, Aidan, arranged to take him back to Balbriggen in Ireland for a visit. The plan was to take Mary, too, but in the end she refused to go because she was afraid to fly. Thus, just Cal and Aidan went, and they had a wonderful trip together. The whole village threw what Cal describes as “a big do” and even had a small parade to welcome him back after so many years. Cal was astonished by the village’s reaction, but was sad that only three of his sisters were still living. Everyone else had passed away. Still, it was one of the highlights of his dad’s life, Aidan says, and he enjoyed seeing so many of his nieces and nephews and extended family.

Eventually father and son returned home, and Cal went back to pottering around the house and gardening until Mary died in 1987. At that point, Aidan noticed that Cal was getting more and more forgetful. Aidan would travel into the city from Bensenville each weekend to check on Cal and became more and more worried about his father’s safety. Often Cal would ask, “Where’s your mother?’ or “Where’s the boat today?” obviously forgetting that Mary had since died or that he and Aidan no longer worked on the boats. All three boys had worked with their father for Great Lakes at some point before they found their own careers, but that was years ago.

“He was living more and more in the past,” Aidan says, so much so that Aidan and his wife, Linda, decided to have him move in with them. After only three months, however, Aidan could no longer take Cal’s repeated questions and confusion. Regretfully, then, he placed him in a nursing home nearby, but was not satisfied with the care provided. Also at this time, Aidan was becoming increasingly frustrated by his brothers’ lack of involvement. Both Fergus and Keefe were living in the city, so Aidan decided to place Cal in a nursing home near them so that they would not have an excuse not to help out.

Fergus and Keefe do visit periodically, but Aidan is still the one coming faithfully twice a week to spend time with his dad. Cal, for his part, seems to be adjusting well. He is at times disoriented and asks repeatedly for Aidan or Mary, but is easily redirected. He does not mind sitting with other residents, though he does not really interact. His favorite thing seems to be listening to music.

(Originally written Oct. 1996)

The post Unwilling to Give His Brother the Biggest Share of the Catch appeared first on Michelle Cox.

June 1, 2017

“One More Christmas”

Angela Esposito was born on September 29, 1918 in Chicago. Her father, Leo Esposito, came to America as a young man from Florence, Italy. He made his way to Chicago and found work as a stone mason. After working at that for several years, he saved enough to open an ice cream parlor, making all the ice cream and candy himself. He met another Italian immigrant, Benigna Ricci, and they soon married in 1917.

Angela Esposito was born on September 29, 1918 in Chicago. Her father, Leo Esposito, came to America as a young man from Florence, Italy. He made his way to Chicago and found work as a stone mason. After working at that for several years, he saved enough to open an ice cream parlor, making all the ice cream and candy himself. He met another Italian immigrant, Benigna Ricci, and they soon married in 1917.

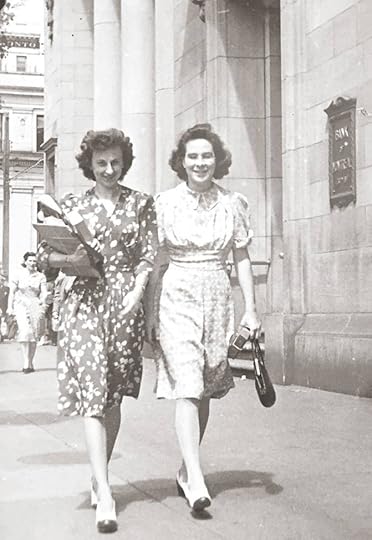

One year later, their first child, Angela, was born. The little family lived in Lakeview at Diversey and Wilbur, and it wasn’t for another seven years before another baby was born, Claudia. Angela and Claudia went to school in Lakeview and even attended high school.

Upon graduation, Angela got a job downtown as a secretary. Angela enjoyed her position, but after a few years, a friend encouraged her to look for work in the legal departments of companies because the salaries were higher. Angela, always shy and hesitant, deliberated this move for a long time, but then decided to take her friend’s advice. She switched to being a legal secretary and in that capacity worked for many years as a temp. This suited her because she made a lot more money, though she didn’t get benefits. Occasionally, a company she was temping for would offer a permanent position, and if she liked it, she took it.

Though she was “on the quiet side,” Angela was very social. She made some good friends at her various jobs and loved getting together with “the girls” after work. Their favorite activity was to go to dinner at the Italian Village and then head over to the Schubert or the Blackstone to see plays. Angela loved the theater and music of any kind. She also loved reading (mystery was her favorite!) and watching Westerns on TV. She also loved to play scrabble.

Though she had many friends and went out a lot, Angela never seemed to find a man she loved enough to marry, she says. There was one boy she met at school, but he was Polish. She didn’t think her parents would approve of him, so she never allowed a real relationship to develop. Angela says she went on a number of dates over the years, but she always had more fun with her girlfriends. Her parents were always offering to set her up with a nice Italian boy, but she always just laughed and said no.

As the years went on, however, her mother, Benigna, grew more and more impatient for a grandchild, so when Angela’s sister, Claudia, announced that she was getting married at age 23, Benigna was overjoyed. It was then that she confessed to Angela, simultaneously swearing her to secrecy, that she had recently been diagnosed with cancer. She kept it a secret from everyone, except Angela, and Leo, of course, until after the wedding and they had seen Claudia and her new husband off on their honeymoon to New Orleans. Later that same day, Leo drove her to the hospital for her first surgery.

Angela still lived at home, and caring for her mother then became her main priority outside of work. Angela spent the next year “watching her waste away,” until Benigna died at age 52 on Thanksgiving Day, 1949. Angela says that she has never been able to enjoy Thanksgiving since then. Four years later, her father, Leo, died of complications with diabetes, and Angela was left alone, Claudia having since moved to New Jersey with her husband. Angela was reluctant to stay in the family apartment by herself, so she moved in with a girl from work, who had a hotel apartment nearby, also in Lakeview.

Angela stayed there until the early 1960’s when she decided to get her own place and found a studio apartment in Rogers Park for $92 a month. She stayed there for fifteen years, but as the neighborhood grew more and more unsafe, she put her name on a waiting list for an apartment at North Park Village and moved to the northwest side for the interim. Finally, in 1990, she got a call saying that an apartment had opened up, and she moved in right away.

Angela enjoyed meeting her new neighbors and was able to live very independently for several years until she began to slow down in the summer of 1995 when she became very lethargic and lost a lot of weight. When she finally went to the doctor, she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. She was hospitalized for about four weeks and then made the move to a nursing home with the help of the hospital discharge staff.

Fortunately, Angela has a nephew, Tom, living in Chicago, and he and his family have become very supportive of Angela. Claudia has long since passed away, so Tom is all she has. Tom and family visit often and are trying very hard to make Angela’s remaining time as pleasant as possible. Angela, for her part, says she has never handled stress well, but realizes that “crying and going into hysterics” in light of her prognosis, “isn’t going to help anything.” At times, she is very sad, especially as she realizes she only has “one Christmas left,” but she is trying hard to be positive. She is a very sweet, down-to-earth woman who always seems to have a kind word for those who stop to talk to her. The staff encourage her to mingle with the other residents, but she mostly prefers to stay in her own room.

(Originally written December 1995)/(Photo: Angela Esposito, left)

The post “One More Christmas” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

May 25, 2017

“Don’t Help Me Anymore”

Samuel Werner was born on April 25, 1920 in St. Louis, Missouri to Arne Werner and Kathleen Murphy. Kathleen was born in Ireland and was just a baby when her family immigrated to Texas. When she was only three, the family moved again to St. Louis. Similarly, Arne had been born in Germany, and when he was a small child, his family immigrated to St. Louis as well. Arne and his brothers grew up in St. Louis and ironically ended up fighting in WWI on the American side. Together, Kathleen and Arne had ten children. Only one, James, died in childhood at eight months.

Samuel Werner was born on April 25, 1920 in St. Louis, Missouri to Arne Werner and Kathleen Murphy. Kathleen was born in Ireland and was just a baby when her family immigrated to Texas. When she was only three, the family moved again to St. Louis. Similarly, Arne had been born in Germany, and when he was a small child, his family immigrated to St. Louis as well. Arne and his brothers grew up in St. Louis and ironically ended up fighting in WWI on the American side. Together, Kathleen and Arne had ten children. Only one, James, died in childhood at eight months.

When Samuel was just two years old, the family moved to Chicago where Arne was able to find work as a sheet metal worker. Sam attended grade school and went to high school for a little while before he quit to attend a technical school to learn to be a sheet metal worker like his father. He was soon apprenticed, and when he completed his apprenticeship, he and Arne went into business together, owning their own shop for 34 years.

Sam’s mother, Kathleen, was never in great health and continued to have miscarriages. She was over 300 pounds and had what was called “dropsy.” She died when she was just forty-seven. It was Sam that discovered her. He had just come home from buying his sisters their Easter dresses and found his mother dead in her bed. Arne also died young, at age fifty-eight, of a ruptured spleen.

Sam took over the sheet metal shop and eventually married one of his sister’s friends, a girl by the name of Minnie Kunkle. He and Minnie had six children: Peggy, Janet, Doris, Gary, Roger and Arnold. Sam was a very outgoing man who loved music and singing and could play the harmonica, the piano and the organ, all of which he taught himself. His favorite forms of music were Irish ballads and country music because, he once said, the lyrics of both are so sad. For a time he even sang in the choir at his church, St. Timothy’s Lutheran, which was very near their house on Armitage. He was a real outdoorsy sort of man, as well, and also enjoyed hunting, fishing, camping, horseshoes, Ping-Pong, blackjack and sports of any kind. He had a real zest for life and was interested in many different things.

For some unstated reason, his marriage to Minnie did not work out, and they divorced in 1971. That same year, Sam decided to remodel a building he owned on Belden and hired a woman by the name of Maria Pasternak to come in and varnish the stairwell. Sam had not met her before, as he was only going on a recommendation from someone at work. He was waiting in the foyer of the building to let her in to start the work, and when he saw her, “something just clicked” between the two of them, Maria says. She was a divorced woman, twenty years his junior, with three kids. “It was not an ideal situation by any stretch,” says Maria, but they began dating anyway and married the following year.

Sam helped raise Maria’s three kids: Earl, Patsy and Roy, and became fiercely attached to them, almost more so than to his first six children with Minnie, who had all gone to live with her. He and Maria had a very close relationship and appear to love each other very much, even now. “He was a wonderful father,” Maria says. “He never, ever lost his temper” and seemed to have infinite patience.

Sam continued working at his sheet metal shop until the IRS caught up with him in 1985, and he lost it due to back taxes. It was sold to a new owner, who kept Sam on as an employee. Sam continued working in the shop for four more years until he quit because his arthritis was getting so bad. Then, in early 1995, he also lost his building on Belden due to back taxes and consequently went into a depression.

Maria believes the stress of these events caused Sam to have a heart attack. He spent many weeks in the hospital recovering, and was just about to be discharged when his doctor decided to do one more test. Maria believes they botched the test somehow because during it, Sam turned gray and stopped breathing. The staff immediately tried to counteract whatever they had done, says Maria, and whisked him off and put him on life support.

Sam spent five weeks in a coma, during which time Maria rarely left his side – talking and singing to him and remembering aloud all of the good times they’d had together. Indeed, Maria partially credits herself for Sam coming out of his coma, and was overjoyed that he “came back” to her. He was eventually released to a nursing home to fully recover, but Maria was not happy with the care and has since switched him several times to other facilities. Twice more he was put on life support, and after the third time, Sam supposedly told Maria, “don’t help me anymore,” which meant, Maria says, that he did not want to “go through all of that again.” Somewhat reluctantly, then, Maria agreed to put him in a hospice program at his doctor’s suggestion.

Maria seems satisfied with his current nursing care, but she is very sad and depressed, especially as her son, Roy, is also dying of cancer. She says that she is “utterly heartbroken” and doesn’t know if she has the “strength to go on.” Sam, meanwhile, does not appear agitated or distressed. His cognitive level appears to be very poor, but Maria claims he is still quite alert and responds intelligently to her, though the staff has not specifically witnessed this. At this time, he remains mostly in bed or in one of the day rooms. He does not interact with the other residents, as Maria rarely leaves his side and tends to speak for him.

(Originally written: November 1995)

The post “Don’t Help Me Anymore” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

May 18, 2017

“Everyone Died But Me”

Eliza Radic was born on May 3, 1906 in Chicago to Bert Jarvi and Miriam Jokela. Both Bert and Miriam were born in Chicago as well, though their parents had emigrated from Finland. Bert worked as a “refinisher” of sorts and did silver plating. Miriam was a housewife and took in sewing while she cared for their three girls: Ruby, Eliza, and Catherine.

Eliza Radic was born on May 3, 1906 in Chicago to Bert Jarvi and Miriam Jokela. Both Bert and Miriam were born in Chicago as well, though their parents had emigrated from Finland. Bert worked as a “refinisher” of sorts and did silver plating. Miriam was a housewife and took in sewing while she cared for their three girls: Ruby, Eliza, and Catherine.

The Radics were unfortunate in that they suffered many losses, some might even say tragedies. Their oldest daughter, Ruby, was diagnosed as a child with epilepsy and died as a teenager, though of what exactly it is unclear. Whatever it was, Miriam blamed herself, as the doctors recommended that Ruby be sent away to an institution when it was first discovered that she was an epileptic. Miriam, however, couldn’t bear to send her child away and vowed to care for her at home. So when Ruby died, possibly somehow in conjunction with a fit, Miriam could never forgive herself and succumbed and died soon after of tuberculosis.

After Miriam died, Bert met and married a woman by the name of Norma Fielding, whom he had met at a party. Eliza says that she didn’t mind her stepmother and that Norma was kind to her and her remaining sister, Catherine. Tragically, however, Norma died, too, in 1944 of a brain hemorrhage.

Eliza graduated from 8th grade and got a job working for Sears, Roebuck and Co. She worked there until she married Walter Radic, who worked in a paint factory. She met him at a carnival put on by her church, Our Lady of the Mount, and the two of them began dating. After a year, they married and moved into the bottom flat of the building her parents had owned in Cicero. Thus Eliza went from living in the upstairs apartment with her father and Norma to the downstairs apartment with Walter.

When WWII broke out, Walter enlisted in the army and was stationed in France. He was injured after only a few months of being there, however, and was shipped back home to recover. He was able to get his job back at the paint factory, but “he was never the same,” Eliza says.

Eliza and Walter very much wanted children, but “none came.” At first Eliza was very saddened by their childlessness and went into a brief depression. Eventually, however, she put it behind her and tried to concentrate instead on her job and her sister, Catherine, who still lived at home with Bert and Norma.

Catherine was always considered to be “a little slow,” and seemed destined to be a spinster. She surprised everyone, however, when she one day announced that she was getting married to a man who drove a bread delivery truck. They had met at the movies, she told everyone, though she was not known for a predilection for films. Nevertheless, at age fifty, Catherine got married, which was a nice bit of happy news for the family, despite any misgivings they might have had regarding Catherine’s ability to be a housewife and manage a home. Apparently, she did alright, and she and her husband, Jimmy, seemed happy with each other. It was not to last, however, as Catherine died just a year later of cancer.

Eliza was always a little bit shy, and it was Walter who encouraged her over the years to join many ladies groups at church and in the community. Eliza loved crocheting and volunteered to crochet a blanket for each new baby baptized at her church, which was still Our Lady of the Mount. She also loved to bake and to read and spent many hours volunteering at the library. She and Walter did a bit of traveling, though never too far from home, as Walter didn’t like to take off too much time from work. Eliza says she loved to travel and wished she could have done more. Their plan was to take a trip to Europe once Walter retired, but, again, tragedy struck, and Walter died suddenly of a heart attack in his fifties, not long after her sister, Catherine, had died.

After Walter passed away, Eliza lived alone in the apartment in Cicero and became increasingly paranoid as time went on, reports her long-time neighbor, Helen Simcek. Helen says that Eliza became convinced that someone was coming into the house and stealing items, which Helen later found hidden around the house. Eliza became increasingly confused, often repeating “everyone died but me,” over and over, among other things, so much so that Helen finally convinced her to let her take her to a doctor, who eventually diagnosed Eliza as having some sort of brain disorder. As Eliza has no family or friends left, Helen volunteered to help her settle into a nursing home and bring some of her things.

Surprisingly, Eliza is making a smooth adjustment to her new environment. At times she is confused, but overall she is pleasant and sweet. She was delighted when the activity staff brought her some crocheting needles and supplies, and she likes to read – out loud – the introductory materials she received from the home upon her admission, such as the Resident Bill of Rights or the letter from the administrator. She enjoys reading and commenting on this material very much and likes to discuss its finer points. She has yet to make any close friends but enjoys sitting with others.

The post “Everyone Died But Me” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

May 11, 2017

Forever His Bride…

Esther Andrews was born on February 14, 1910 in Chicago to Lester Simonis and Nellie Baird. It is thought that Lester was an immigrant from Latvia and that Nellie had been born in Scotland. According to family legend, shortly after Nellie arrived in America as just a baby, her parents both died, and she was placed in an orphanage. At fifteen, she began working as a maid, where she met Lester Simonis, who delivered the daily milk to the house she was employed at. Lester eventually proposed to Nellie, who accepted him, and they were married soon after. Nellie quit her job to care for their eventual four children: Verla, Clifford, Stella and Esther, while Lester continued working as a milkman. When Esther was just a baby, however, Lester died, though no one in the family seems to remember of what. Nellie took in washing for a while to make ends meet, and eventually ended up marrying Daniel Juric, a kind man, who worked in various factories around the city.

Esther Andrews was born on February 14, 1910 in Chicago to Lester Simonis and Nellie Baird. It is thought that Lester was an immigrant from Latvia and that Nellie had been born in Scotland. According to family legend, shortly after Nellie arrived in America as just a baby, her parents both died, and she was placed in an orphanage. At fifteen, she began working as a maid, where she met Lester Simonis, who delivered the daily milk to the house she was employed at. Lester eventually proposed to Nellie, who accepted him, and they were married soon after. Nellie quit her job to care for their eventual four children: Verla, Clifford, Stella and Esther, while Lester continued working as a milkman. When Esther was just a baby, however, Lester died, though no one in the family seems to remember of what. Nellie took in washing for a while to make ends meet, and eventually ended up marrying Daniel Juric, a kind man, who worked in various factories around the city.

Esther received a somewhat sketchy education, only attending school through the fourth or fifth grade. She quit school and got various odd jobs until she found a permanent place at the Excelsior Seal Furnace Company on Goose Island at age thirteen. Her job was to pack the parts in boxes to be shipped out.

When she was nineteen, however, her mother, Nellie, died unexpectedly of the flu. Esther was the only one still left at home, so for a while she and her grieving stepfather, Daniel, tried to make a go of it. Daniel, however, went into a deep depression, and Esther found it hard to cope with him just on her own. She appealed to her older sister, Verla, who agreed to take in both Esther and Daniel, provided that Esther “do her part” around the house. Esther, eager to be relieved of the sole responsibility of caring for their stepfather, agreed to her sister’s conditions, but soon lived to regret it. Verla gave Esther long lists of chores that she was expected to complete each day, including gardening, in addition to working at Excelsior Seal.

This continued for nine long years until Daniel met another woman, Mary Budny, at a dance. They married six months later, and Daniel finally moved out of Verla’s home, leaving Esther behind, who, at age 28, was beginning to think life had passed her by. She hated living with Verla and her husband, Bob, and being “their slave,” but she couldn’t see any other option.

Esther had nearly resigned herself to being a spinster until one day, September 14, 1938, to be exact, a young man by the name of Glenn Andrews walked into Excelsior Seal Furnace Company looking for a job. Glenn was hired on the spot, and it was Esther’s job to show him around. The two took a liking to each other, and before the day was out, Glenn asked her out on a date. Esther excitedly said yes, and Glenn took her to the Aragon ballroom.

Esther and Glenn dated for four years before they were married on January 22, 1944. Four days later, Glen left for the war. He served for 27 months in Japan and the Philippines and says that it was the many, many care packages of cookies and candy and letters from Esther that got him through. When he came back, miraculously “safe and sound,” he and Esther had to “relearn each other” all over again. Esther had spent the war still living with Verla and Bob, who had not altered their treatment of her despite the fact that she was now a married woman.

When he returned, Glenn got his job back at Excelsior, and he and Esther rented a little apartment on Sedgewick. Their neighbors were Ada and Dieter Kahler, a German couple with three kids, whom they got to know very well and whom they eventually bought a two-flat with. Both families lived there for the next 27 years and became best friends. Glenn and Esther never had any children, so they enjoyed helping with and watching Ada and Dieter’s children, whom they became very close to.

Glenn and Esther were very active over the years in the United Steel Workers Union and served on many, many committees. They enjoyed visiting with friends and playing poker and loved going to see movies. Their biggest passion, however, was traveling. They spent every vacation traveling, and in 1979, when Esther finally retired from Excelsior, after working there for 54 years, they decided to travel full-time. They spent the next 14 years traveling to such places as New York, Wisconsin, Mexico, Lake Louise, Niagara Falls, New Orleans, Florida, Mt. Rushmore, California, Hot Springs, the Grand Canyon, and many, many more. They traveled by car, train, and even bus on some occasions.

After so many years of enjoyment with each other, “Esther began to change,” says Glenn, in the early 1990’s. She became increasingly confused and was often found wandering the neighborhood. Also, says Glenn, she put on “layers of layers of clothes” and even once chased him through the house with a knife. Unable to understand her diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, Glenn tried to care for Esther himself for about eleven months before he finally gave in to the doctor’s suggestion that he admit her to a nursing home, heartbreaking though it was for him to be separated from her.

Technically, Glenn still lives in the two-flat that he and Esther purchased with the Kahlers, though only he and Ada are left, Dieter having died years ago and their children having since moved away, but he prefers to spend his days and evenings at the nursing home. Here he sits with his beloved Esther, 365 days a year, wheeling her about the home, taking her outside to sit in the gardens, or bringing her to various activities. Esther does not really participate in any of the home’s events, however, and just sits quietly with her eyes closed. If asked a question, she usually gives a garbled, nonsensical answer.

Glenn does the talking for her as he holds her hand. He knows every single resident and staff member. He loves to talk to whomever will stop long enough, and especially enjoys telling stories of he and Esther’s traveling days. When the staff ask him why he doesn’t just make it official and move here, too, Glenn says that he couldn’t do that to poor Ada. But he remains devoted to Esther, coming every day and always lovingly calling her “my bride,” though he often sadly states that she is just a shell of the lovely, sweet woman she once was.

(Originally written May 1995)

The post Forever His Bride… appeared first on Michelle Cox.

May 4, 2017

“Everyone Says I’m Crazy”

Cleo Newman was born on February 10, 1911 in Kewanee, Illinois to Peter Wyrick and Lorene Crawford. It is believed that Peter was a Polish immigrant and that Lorene was of English descent. Peter had apparently been a farmer in Poland and found work on various farms throughout the Midwest after he immigrated here. Eventually he married Lorene Crawford and was able to buy his own small farm in Kewanee. While he worked the farm, Lorene cared for their eleven children, only eight of whom lived to adulthood.

Cleo Newman was born on February 10, 1911 in Kewanee, Illinois to Peter Wyrick and Lorene Crawford. It is believed that Peter was a Polish immigrant and that Lorene was of English descent. Peter had apparently been a farmer in Poland and found work on various farms throughout the Midwest after he immigrated here. Eventually he married Lorene Crawford and was able to buy his own small farm in Kewanee. While he worked the farm, Lorene cared for their eleven children, only eight of whom lived to adulthood.

The Wyricks were extremely poor, and Cleo only went to school through the eighth grade before quitting to find a job. When she was 18, she decided to move to Chicago to look for work and stayed with an older sister. She worked in various factories and restaurants and eventually met a man by the name of Nelson Newman while she was waitressing.

Nelson was older than Cleo and had been married before, but the two of them began dating and were married soon after. Cleo was surprised to find that Nelson expected her to continue working as a waitress to support them while he went back to school to become a history teacher. After three years of this, Cleo became pregnant, which infuriated Nelson, as it interfered with his plans of finishing his degree. When the baby, Marcella, was born, Nelson was forced to stop school and find a job, which he very much resented. Cleo and Nelson fought constantly, and eventually, when Marcella was just three years old, they divorced. Nelson went on to finish his degree, become a history teacher, and marry two more times. He died on Memorial Day in 1984, and Cleo has never ceased to hate him.

In fact, Nelson became Cleo’s focal point for any bad thing that ever happened to her for many, many years. After the divorce, Cleo moved from Downers Grove back into the city with Marcella where she found work again, but she became increasingly angry and bitter as the years went on. Marcella says that it was after the divorce that her mother really “went off the wall,” though she was always “a bit off.” Frequently, Cleo would complain that “everyone says I’m crazy.” Cleo resented having to care for Marcella, saying that “no one’s going to want me with a kid.” Marcella always felt “in the way,” and was taught to hate her father, Nelson. Cleo often told Marcella outrageous stories about Nelson, which Marcella was sure were lies about him, such as the fact that he supposedly held Cleo by the ankles and bounced her on the floor while she was pregnant, hoping she would miscarry. Marcella, though she was allowed little contact with her father, refused to believe this of him.

As Marcella grew older, Cleo’s relationship with her daughter grew more and more troubled. Cleo became very suspicious and jealous of Marcella and would accuse her of many, many untruths. For one thing, Cleo accused Marcella of being jealous of her beauty, though it was Marcella that was growing into an increasingly beautiful girl. In reality, it was the opposite, Marcella says. It was her mother who was becoming increasingly jealous of her. “You could never talk to her,” Marcella adds. “You could never reason with her.”

When Marcella was in sixth grade, Cleo married a man named Nick Moretti, but by the time Marcella was in high school, they were already divorced. Marcella thinks it odd that even though Nick was also “no great catch,” Cleo’s anger and bitterness remained directed at Nelson. Though Nick could be cruel in his own way, Cleo hardly ever mentioned him in her rants, only Nelson, who Marcella believes became a sort of obsessing. Her mother had other obsessions, too, Marcella reports, one of them being health and fitness. She became a vegetarian, stopped going to doctors, and did calisthenics, including push-ups, into her 80’s. She abhorred doctors and claims to have cured herself of various illnesses and injuries, including cancer and a broken arm. Again, says Marcella, “no amount of reasoning ever worked with her.”

Cleo also became obsessed with Marcella’s social life, limited as it was. Cleo would constantly chastise Marcella for “sleeping around” and frequently called her a “pregnant slut,” even though Marcella had yet to ever even kiss anyone! After Marcella finished high school, she got two jobs to try to help support herself and her mother, as Cleo only worked sporadically during those years. When Marcella would come home late from her night job, Cleo was always waiting there to accuse her of “running around,” refusing to believe that Marcella was actually out working, not out sleeping with a guy. Finally, Cleo became so incensed at Marcella’s imagined behavior that she kicked her out of the house.

Marcella was then forced to find her own apartment and tried to make a life for herself separate from Cleo. Eventually, she met a nice man by the name of Joseph Mueller, and they married. Marcella says that they had to practically beg Cleo to attend the wedding, and when Marcella quickly became pregnant, Cleo’s response was “now she’ll find out what it’s all about to raise a kid.” As the years went on, Cleo showed little interest in Marcella or her grandchildren, as they came along, and the mother and daughter drifted even farther apart.

With Marcella out of her life, Cleo apparently became even more distrustful and suspicious of everyone around her. She spent her days riding downtown on the bus, going from lawyer to lawyer, attempting to sue people for stealing her money. The main recipient of her wrath and blame now became her accountant, one Mr. Shum, whom she decided had stolen all of her money. She also accused Marcella of somehow conspiring with Mr. Shum to steal her money. Marcella later laughed at this accusation when she heard it, saying she had never even met a Mr. Shum. Cleo persisted in her delusion, often saying that “Shum wants to ‘do’ me, though I know he’s already ‘doing’ Marcella.”

When not going from lawyer to lawyer, Cleo also spent time going from bank to bank, opening and closing her accounts, saying that someone had stolen her bank books. Years later, Marcella found boxes and boxes of old bank books tucked away around the house where Cleo had apparently hidden and then forgotten about them.

Likewise, Cleo began calling the police on a somewhat regular basis, claiming that she had been the victim of a robbery. Each time the police would come and point out that no locks were broken and no windows smashed. Still, however, Cleo would insist that something had been stolen, even a small thing like a box of tweezers. Or she would point to empty hangars in her closet as if to say, “See? There’s nothing on them, so the clothes must have been stolen!”

The only person in Cleo’s life at this time was her brother, Bill, who had been injured in a motorcycle accident at age twenty-one and who now came to live with Cleo. “Uncle Bill,” says Marcella, was also “a little on the crazy side.” Bill lived with Cleo, absorbing her strange stories and theories until he died in the early 1990’s. After that, Cleo latched onto his daughter, Mary, who, Marcella says, was “easily manipulated.”

After Bill died, Mary indeed became Cleo’s companion and would drive Cleo around to various law offices and banks, still accusing people of stealing from her. After a couple of years of this, however, even the sweet, gentle, accommodating Mary began to crack under the strain. Cleo sometimes called her five times in a half hour, wanting something or asking the same question over and over. Mary also began getting calls in the middle of the night from the police, saying that they had picked up Cleo, wandering, lost, around the neighborhood. Finally, in desperation, Mary called her cousin, Marcella, to appeal for help. Marcella, who had been out of her mother’s life for over thirty years, had no idea that Cleo had “gotten so bad.” She apologized to Mary for Cleo’s behavior and came back into the picture to help. When the police then began calling her in the middle of the night, she decided that it was time to put Cleo in a nursing home.

Needless perhaps to say, Cleo is very resentful of her placement here and remains angry, disoriented and depressed. She repeatedly accuses Marcella of dumping her here and complains that “I’m not sick. I don’t belong here.” Marcella is concerned for her mother’s safety and security, but is neither emotional nor affectionate with Cleo. She says that she feels sorry for her, as she has obviously been mentally ill all these years, but she has no emotion left for her mother and does not feel guilty about placing her here. Cleo refuses to acclimate or meet other residents and switches quickly between extreme anger and tears, often saying “I want to get out of here!”

The post “Everyone Says I’m Crazy” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

April 27, 2017

A Neighborhood Gem!

Herbert Jones was born on May 14, 1899 on a farm in Bolton, Mississippi. His parents, Jesse and Hattie Jones, owned the small farm they worked, which they were very proud of, as Jesse’s father had been a slave. There were thirteen children in the Jones’ family, and Herbert was the youngest boy. He went to school until the seventh grade and mostly helped his father and brothers around the farm.

Herbert Jones was born on May 14, 1899 on a farm in Bolton, Mississippi. His parents, Jesse and Hattie Jones, owned the small farm they worked, which they were very proud of, as Jesse’s father had been a slave. There were thirteen children in the Jones’ family, and Herbert was the youngest boy. He went to school until the seventh grade and mostly helped his father and brothers around the farm.

In his early twenties, he decided to go to Chicago and look for work. World War I had just ended, and he hoped to find something more than what the farm in Mississippi could offer him. He found a job at International Harvester and worked his way up over the years, eventually becoming a molder.

Herbert kept mostly to himself. He made a few friends and enjoyed working with electronics and carving wood. He joined a church, Apostolic Church of God, which was a Baptist church, and he lived in the South Shore neighborhood on the far south side. When he was in his forties, he happened to meet a young woman by the name of Pauline Everts at a prayer group at church. Pauline was only in her twenties, but Herbert quickly fell in love with her. He was very patient, and courted her very slowly, becoming her friend first and then tentatively asking her out on a date to an ice cream parlor. To his great surprise and excitement, she said yes. Pauline says she had no idea when they started dating that he was twenty years older than her or she would have said no! Herbert was one of those people, she says, who had a young face. By the time he told her he was in his forties, it was too late, however; she was in love with him. They dated for just six months and then got married. Some of his siblings from Mississippi came up for the wedding, but his parents had already passed away at this point. Together, Herbert and Pauline had five children: Herbert, Jr., Mae, Clifford, Lena and Lucille.

Pauline says that Herbert was a wonderful father, that he was a very patient, understanding man. He had a great sense of humor, but there was also a “no-nonsense” side to him, too. He was a great role model, she says, not just for their children, but for many of the neighborhood children. He knew all of them, and they all felt they could talk to him. Pauline says that when he spoke, he meant it, and all the children knew that, too. If he said something, they obeyed it. Pauline says that whenever Herbert was upset or troubled by something, he would sit quietly somewhere for a long time, thinking, until he came up with a solution.

Herbert had such a positive influence on his neighborhood that in 1992, Ebony magazine did a feature on him for a special father’s day edition, alongside Winston Marsalis. The article illustrated how many lives Herbert had touched beyond his own five children and how his “patient, honest, no-nonsense style” had contributed so directly to the success of so many kids in the neighborhood. Herbert was extremely proud of the accolades from Ebony Magazine, but he remained a very humble man, often saying throughout his life that he was really “just a farm boy at heart.”

Herbert and Pauline were still living in their apartment on South Shore Dr. until July of 1995 when Herbert came down with pneumonia at age 96. At the hospital, it was discovered that his kidneys were also not in the best shape, either. In November of that same year, he was diagnosed with CHF and anemia and was given a blood transfusion. His kidneys were also worse, but because of his CHF, the doctors felt that dialysis might be too hard on his heart. He was discharged home, but was readmitted within several months for being listless, tired and weak. This time, the doctors felt they had no choice by to attempt dialysis, which his heart managed to handle. He was discharged, however, to a nursing home, where he remains unresponsive most of the time.

Pauline and various members of the family visit daily, though Herbert does not interact with them. Pauline is upset by Herbert’s placement and does not seem to accept that it is permanent. She is still hopeful that he will return home. She loves to talk about her life with Herbert and the wonderful man he was. It is very difficult for her to see him this way, and she cries often. Her children and grandchildren have been very supportive, however, and visit frequently.

(Originally written February 1996)

The post A Neighborhood Gem! appeared first on Michelle Cox.

April 20, 2017

“Life Is What You Make of It”

Sadie Davis was born on December 2, 1920 to Ervin Olmskirk and Caroline Fredericks in Clarkson, Nebraska. Ervin worked in a bank, and Caroline cared for their ten children, Sadie being the oldest.

Sadie Davis was born on December 2, 1920 to Ervin Olmskirk and Caroline Fredericks in Clarkson, Nebraska. Ervin worked in a bank, and Caroline cared for their ten children, Sadie being the oldest.

Sadie was a bright child and after finishing high school, won a two-year scholarship to Wayne State College in Wayne, Nebraska. This was following the Great Depression, however, so when the two years were up, Sadie could not afford to stay longer, though she dearly loved her college experience and dreamed of becoming a teacher. She contemplated ways that she could earn the money herself, but before she could come up with any answers, she received word that her father had been killed in a freak accident, which caused her to have to hurry home. Ervin had apparently been out trimming trees when a large branch fell on him, crushing his skull and killing him instantly. He was only forty-six years old. At the time of her father’s death, Sadie was nineteen and her youngest sibling had just turned one. Sadie naturally then gave up all hopes of furthering her education and began looking for a job to help support her mother.

The family had barely time to recover from Ervin’s death when they received word that Ervin’s brother, Anthony, had also died in Chicago. With her husband recently deceased, ten children to take care of and little money, there was no way that Caroline could make the journey to Chicago for her brother-in-law’s funeral, though she fretted endlessly about who would represent the family. Finally, she decided that she would send Sadie with an aunt and uncle who lived in nearby Omaha and who were planning on travelling up to the funeral on the train. Sadie was chosen because she hadn’t yet found a job and because she was the same age as Aunt Betty and Uncle Tom’s only child, Imogene, who was also making the journey. That way, Aunt Betty said, Imogene would have someone to talk to.

On the long train ride to Chicago, Sadie and Imogene enjoyed getting to know each other again, having not seen each other for several years. Sadie told Imogene all about her college days at Wayne State, and Imogene told her all about living in the big city of Omaha. Together the girls schemed that if they could somehow find jobs in Chicago while they were there for the funeral, they might be allowed to stay.

The funeral, it turned out, was all the way north of the city in a small vacation village called Fox Lake. Many relatives showed up from out of town and rented small cottages rather than staying in hotels. Sadie and Imogene began to look for work right away, though not much could be found in Fox Lake. As it turns out, Imogene went to the beach one day without Sadie, who stayed behind in the cottage because she was feeling ill. Later in the day, feeling a little better, Sadie ventured out doors and was intrigued by a young man working on a sail boat in the yard next door. The two began talking over the fence and began a little friendship. His name was Lowell Davis.

Eventually, after many days of talking over the fence, Lowell asked Sadie out on a date, and she accepted. They had a wonderful time together and found it very easy to talk, but their new relationship threatened to be over just as it was beginning, as Aunt Betty and Uncle Tom were planning to return to Nebraska soon. Lowell decided drastic measures were in order, so he sold his boat to buy Sadie an engagement ring and proposed to her.

Sadie said yes and arranged to stay with other relatives in the city until the wedding could be planned. She found a job downtown in a millinery shop, and offered to help Imogene find something, too. Aunt Betty and Uncle Tom refused to hear of any such nonsense, however, and despite Imogene’s pleading, insisted that she return to Omaha with them.

Eventually Sadie and Lowell married and moved to the northwest side of Chicago. When WW II broke out, Lowell dutifully joined the navy. Left alone, Sadie considered moving back to Nebraska to live with her family for the duration of the war. In the end, however, she decided to stay in Chicago and found work in a millinery shop. When Lowell eventually returned from the war, unharmed, he got a job as a loan officer at a bank, oddly like her father, Ervin. Sadie continued working in the millinery shop until her first baby was born. In all, Sadie and Lowell had four children, all girls: Shirley, Gloria, Brenda and Virginia. Though she mostly remained a housewife, Sadie sometimes worked as a substitute teacher and also taught CCD classes at her church. She was also very involved in the Girl Scouts and other community organizations. Her hobby was writing the family history going generations back.

Lowell died in 1973, after which Sadie continued living alone, though she was very active. Only recently, when she has been diagnosed with Hodgkin’s, has she begun to need help. She was admitted to the hospital due to complications with her condition and was then discharged to a nursing home. All of her daughters live out of town, except Shirley, who visits regularly and is very concerned for her mom. She puts on a brave face in front of Sadie, but has been known to cry from guilt at not being able to care for her mom at home. Meanwhile, Sadie is making an excellent transition, though she is sometimes very weak and tired. She enjoys intellectual conversations or sitting and watching television with other residents. She does not appear distressed or upset, but says that “life is what you make it.” Indeed, this is a philosophy which Sadie seems to have lived by all her life, taking whatever circumstances she found herself in, and using them in a positive way.

(Originally written: March 1994)

The post “Life Is What You Make of It” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

April 13, 2017

“That’s What Happens When You Fly Too High…”

Ruby Fessler, far right

Ruby Fessler was born in Chicago on September 16, 1937 to Rudi Fessler, an immigrant from Vienna, Austria, and Ida Beldy, an immigrant from Hungary. Rudi worked for a trucking company. Ida cared for their four children and was also a breeder of Shih Tzu poodles. Ruby graduated from high school, but says she didn’t have any use for school, especially since she began working as a model at age twelve. She modeled primarily for Sables and Pat Stevens. Though she didn’t really like it, the money helped to support the family, and her mother made her continue.

When she was eighteen, Ruby entered a beauty contest at a night club in Logan Square and won. The management was so impressed by her that they offered her a job managing their “Opera Club.” It was at the night club that the young Ruby met Roger Kipman, a real estate broker who was, in her words, “a real mover and shaker.”

Roger soon took a liking to Ruby, who claims she married him “under duress” at age 24. After they were married, Ruby says she discovered that he had been indicted three times for six million dollars in government and international theft. Roger tried to get Ruby to sign some of his money into her name to help hide it. When she refused to cooperate, Roger beat her. Ruby says that she was hospitalized three times during their two-year marriage and that the stress and physical abuse left her permanently disabled.

Ruby says she was finally able to get away from Roger Kipman and filed for a divorce, though Roger vowed he “would always be around to get even with her.” The government apparently offered her political asylum, as did five other embassies, as Roger’s thefts included international schemes and bank accounts. According to Ruby, several of the employees she met with at the embassies claimed that they had never seen a woman so abused. “But,” says Ruby, “that’s what happens when you fly too high. You get your wings clipped.”

In the end, Ruby turned down all the offers from the embassies, as they could promise safe passage out of the country, but could not necessarily help her to get back in. As Ruby was still recovering at the time, she did not relish leaving the United States, so she turned down all the offers and went to live with and care for her mother, Ida.

For many years, Ruby had a quiet life with her mother and took many trips around the country with her. She also loved music, art, gardening, and studying ancient cultures. She even took a few classes in ancient history at the local community college because she was so interested in this subject. Though she did go out from time to time to the various “private clubs” of which she was a member, she tried hard to keep a low profile, as she was afraid that Roger was still out there looking for her.

When Ida passed away in 1990, Ruby moved into her own apartment. She had little money, however, and was forced to live in “slum apartments, surrounded by gangs, drug addicts and thieves.” Ruby somehow blames all of this on Roger, saying that because he was a “slum landlord,” he made her life a hell and had “bad people” follow her from apartment to apartment. At some point, she reached out to her brother, Rudy, who helped her find a decent apartment and stopped over from time to time to check on her.

Regardless of the better neighborhood Rudy helped her to find, Ruby, it seems, was still not safe. In 1992, four men apparently broke into her apartment and attacked her. They beat her severely, breaking one of her arms, a leg and her spine, and leaving her for dead. After a few days, however, Rudy found her lying unconscious and called for an ambulance. Though she cannot prove it, Ruby is convinced that Roger was behind the attack. She despairs that he was never brought to justice, first because she could never prove that he was involved, and secondly because she has since heard that Roger was killed shortly after the incident in a street fight.

Ruby spent over a year in the hospital recovering and was then released to a nursing home, where she spent another two years. In that time, her brother, Rudy, died, and she very much grieved for him. Ruby claims that she put her name on a waiting list at the nursing home to be moved into an assisted living apartment when one became available. After two years, she inquired about her status on the list and discovered that her name had never been added. Furious, she transferred to a different nursing home with the help of her sister, Peggy, who had been living in California but had relocated to Chicago after Rudy died.

Peggy has helped Ruby with her admission to this current nursing home, but she is very antagonistic to the staff and is at times verbally abusive. She appears to be somewhat mentally unstable herself and makes unrealistic demands on Ruby’s behalf. Ruby, however, though she tolerates Peggy’s presence, is quick to point out that Peggy has no authority over her and cannot sign any documents for her. They have never been close, Ruby says, and adds that “we don’t get along.” When asked about Ruby’s somewhat fantastical history, Peggy will not comment except to confirm that her sister was indeed beaten. With no children and no other living siblings or friends to question, there seems to be no way of easily corroborating Ruby’s story.

The previous nursing home provided some clues, however, saying that Ruby has a history of schizophrenia and suffers from panic attacks. They were also somehow able to determine that previous to her last hospital stay, she had been living alone in dirt and filth and that she had come in to the hospital with many bedsores.

Ruby is very alert and aware of her situation, but seems withdrawn and unmotivated. She does not appear to have any interests in the life of the home and does not interact with other residents except to ask them for cigarettes. She will engage somewhat in conversation with staff if prompted. She looks forward to Peggy visiting, but when she does come, they usually end up arguing.

(Originally written: February 1996)

The post “That’s What Happens When You Fly Too High…” appeared first on Michelle Cox.