Michelle Cox's Blog, page 36

September 8, 2016

Orphaned at Age Eight

Maria Kumiega was born on June 7, 1913 in Poland to Albert and Milena Gajos. Milena’s maiden name was also Gajos, though she says her parents weren’t related. Albert owned a small farm, and Milena cared for Maria, who was just a baby when World War I broke out. Albert was soon rounded up to serve in the Russian navy, and tragically never returned. Milena eventually remarried, but while giving birth to her first child with her new husband, both she and the baby died. Maria’s new stepfather could not even stand to look at her, so Maria was essentially an orphan at age eight.

Maria Kumiega was born on June 7, 1913 in Poland to Albert and Milena Gajos. Milena’s maiden name was also Gajos, though she says her parents weren’t related. Albert owned a small farm, and Milena cared for Maria, who was just a baby when World War I broke out. Albert was soon rounded up to serve in the Russian navy, and tragically never returned. Milena eventually remarried, but while giving birth to her first child with her new husband, both she and the baby died. Maria’s new stepfather could not even stand to look at her, so Maria was essentially an orphan at age eight.

Eventually it was arranged for her to go live with an uncle in a distant village. Her life with her uncle wasn’t terrible, she says, though she was not treated like the other children in the family and was made to work very hard. She received only a couple of years of schooling, but she was eager to learn and taught herself to read and write, despite the long hours she put in around the house and farm.

It is not surprising, then, that she married very young—at sixteen—to Daniel Kumiega, a boy she had grown up with in her uncle’s village. Daniel, a few years older than her, saw how difficult it was for Maria, living with her uncle, and he was subsequently very kind to her. Often he would bring her a sweet wrapped in his handkerchief on a Sunday. Maria had to hide her gifts from the family, but she looked forward to his visits very much. She grew to love him, even from a young age, so when he asked her to marry him, she didn’t have to think about it at all, and said yes. She had hoped to use the land owned by her parents as a dowry, but it had unfortunately been confiscated, by whom Maria isn’t sure. Instead, Daniel found work on a nearby farm, and Maria soon had a baby, Marta, to care for.

Maria does not like to talk about the Second World War and does not say how the little family survived it, just that when it was over, there was little opportunity to make a living. They did not want to stay in Communist Poland, so in 1948, they escaped to France. Daniel found work on farms there, and they remained for thirteen years, during which time another child, Bosko, was born.

When the French economy took a downturn, however, Daniel could no longer find any work. He was forced to take a job in the mines, though the conditions were grueling. Daniel couldn’t take the back-breaking work and, likewise, found it especially hard to be underground all day when he had spent his life working outdoors in the fields. Desperate, they decided to immigrate to America and applied to the Catholic League for help. Finally, around 1961, they made it to Chicago. Their son, Bosko, came with them, but Marta remained behind as she was already married. Daniel found work as an unskilled laborer in factories, and though it wasn’t outdoor work, he was grateful that he was no longer in the mines. Eventually, Marta and her husband and children made their way over, too.

After saving for a long time, Maria and Daniel were able to buy a small house in Humboldt Park, which was Maria’s pride and joy. Unfortunately, however, Daniel died in the early 1970’s, making it very hard for Maria to hold onto the house with only a job as a cleaner. Bosko and Marta were not able to help financially, as they both had their own family and house to care for. Finally, as the neighborhood grew worse and worse and Maria became more and more afraid, she sold the house for much less than it was worth and bought another one closer to Bosko.

Maria has remained independent until very recently. She was a member at St. Hyacinth and spent her later years gardening, her favorite being roses. When she was diagnosed with renal failure at age 83 and was having trouble getting around, it was suggested by Marta and Bosko that she go to a home. When Maria asked if she might instead live with one of them, Bosko explained that everyone works and that there would be no one home with her all day. Reluctantly, then, Maria agreed to go to a nursing home.

Both Marta and Bosko visit her and offer what support they can, though they do not get along with each other. Indeed, they claim to hate each other, though Maria does not seem to know this. For example, Bosko was the one to accompany Maria during her admission, and when he was asked for Maria’s family history, he neglected to even acknowledge his sister’s existence at all. The staff were very surprised, then, when Marta appeared saying that she was Maria’s daughter. Bosko then later admitted he did have a sister, but stated that she is “too stupid” to be of much help. On the other hand, Bosko frequently smells like alcohol when he visits, even if it is a morning visit.

If Maria was once aware of her family’s dysfunction, it seems lost on her now as she is trying her best to fit into the home. She prefers to stay in her room, but can be coaxed out occasionally to talk with other Polish residents, attend Mass or play bingo. If the weather is very warm, she can sometimes be found sitting in the gardens on her own.

(originally written May 1996)

The post Orphaned at Age Eight appeared first on Michelle Cox.

September 1, 2016

“She Lived to be 100!”

Tereza Hlavacek was born on August 15, 1895 in what was then called Bohemia, the part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that later became Czechoslovakia. Her parents were Dobroslav and Marie Cipris, about which little is known. Tereza was one of four children and attended grammar school before she quit to start earning money, which the family desperately needed. She didn’t have much luck, however, so when she was just fifteen or sixteen, she decided to follow her older sister to America, hoping to get a job there. She made the journey alone and traveled to Chicago, where her sister was living in a boarding house. An uncle, Joseph Krall, also lived nearby, and he gave Tereza a job working in his tailor shop.

Tereza Hlavacek was born on August 15, 1895 in what was then called Bohemia, the part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that later became Czechoslovakia. Her parents were Dobroslav and Marie Cipris, about which little is known. Tereza was one of four children and attended grammar school before she quit to start earning money, which the family desperately needed. She didn’t have much luck, however, so when she was just fifteen or sixteen, she decided to follow her older sister to America, hoping to get a job there. She made the journey alone and traveled to Chicago, where her sister was living in a boarding house. An uncle, Joseph Krall, also lived nearby, and he gave Tereza a job working in his tailor shop.

Not long after she arrived, Tereza was introduced to Bernard Hlavacek, who did odd jobs for her uncle and also worked as a delivery man. Bernard, a quiet, shy boy, supposedly fell in love with Tereza right away, impressed by her ability to work hard and the way she always comported herself. He was nervous to ask her out, however, fearing what her uncle would say, and spent a year worshipping her from across the shop. Finally, Joseph pulled him aside one night and asked what he was waiting for. Bernard, stunned with relief and overcome with joyful hope, asked Tereza the very next day to walk with him in Humboldt Park, to which she said yes. They began dating in earnest, then, and married shortly after.

Once married, Tereza stayed home to be a housewife, and Bernard continued working with her uncle, having been elevated now to a full tailor. Eventually the young couple was able to buy a small house with a big yard, which Tereza converted into a huge garden and diligently worked in every day. They had two sons, Joseph and Simon, both of whom Tereza was very attached to.

Tereza toiled endlessly for her little family and was reportedly a very strong, independent woman. She was apparently very stubborn and wanted her own way in most things, but she was also very appreciative of any little thing anyone ever did for her or gave to her. Her daughters-in-law report that Tereza was also a little bit vain, her appearance always being very important to her. Though they had little money, Tereza made it a point to always be nicely dressed. There is a family story that once when an acquaintance was about to leave on a trip to Europe, Tereza was disgusted by her friend’s old, tattered hat, so much so that she apparently whipped off her own hat and gave it to the friend, saying “Here! Take mine!” Even in her nineties, Tereza always donned a sweater because she was unhappy with how her arms looked.

Though Tereza has always been a strong woman, she has also been a very nervous person, especially as the years have gone on. Apparently, when Joseph and Simon both went into the army, Tereza became so fraught with worry that her ears “started draining” and she went deaf in one ear.

The worst blow to her nerves, however, was when Bernard passed away at age 57. He had had a stroke and was taken to Cook County Hospital. Tereza visited him faithfully each day, but on the third day, when she arrived to see him, she was shocked to find his bed empty. When she asked where her husband was, she was told nonchalantly that he had died in the night. From that point on, she says, she developed “the shakes.”

After Bernard’s death, Tereza threw herself into community and church activities. She still gardened and traveled daily from Cicero to the Bohemian National Cemetery in Chicago to lay flowers on Bernard’s grave, a ritual she kept up for six years. In addition, she began cooking for the Bohemian club she belonged to and also started crocheting again. She had always enjoyed crocheting as a hobby, but after Bernard’s death, it became almost a frenzied obsession. Her daughter-in-law, Rita, says that she must have produced thousands of baby booties over the years. She also found solace in traveling and went to Oregon, Florida, Hawaii, and to Europe twice. Sometimes she used a travel planner, but sometimes she made all her own arrangements.

Tereza continued to live independently until 1982, when she had to have a hip replacement. It was then that her son, Joseph, persuaded her to move in with him and Rita. This seemed appropriate to Tereza, Joseph being the oldest, though her favorite was Simon, whom she always referred to as “my baby.” Tereza’s hip mended well, though she continued to have pain on and off through the years. It didn’t stop her from being active, however, and she continued to garden until she was 94.

Unfortunately, Joseph passed away from cancer in 1985, just three years after Tereza had moved in. It was a terrible blow, again, for Tereza and for Rita, but they helped each other get through it. Tereza, now in her 90’s, began to get progressively weaker, however, and needed more and more help. Simon would stop over to try to help Rita, but it was becoming too much for all of them. Rita was beginning to experience her own health problems and was becoming increasingly nervous that something would happen to Tereza while in her care. The suggestion of Tereza moving to a nursing home was finally brought up amongst them all, Tereza realizing that she really had “no other choice.” The only consolation about the move to the nursing home was its close proximity to the Bohemian Cemetery and the fact that many of the residents would be able to speak Czech to her.

Tereza apparently made a relatively smooth transition to life in the home, though there were a few bumps along the way. At first, perhaps to deal with the stress of the move, Tereza spent all of her time in her room, furiously crocheting. When the staff attempted to intervene and limit her time spent crocheting so that she could meet other residents and participate in the facility’s activities, she grew angry and refused to crochet any more. She wanted complete control of her hobby, she said, or she didn’t want to do it all. She called Simon to come pick up all of her crochet materials and hasn’t engaged in this activity since, though many people have tried to persuade her.

Tereza eventually began to acclimate to the home, but she looked forward to Simon’s visits, which were two or three times per week. Simon seemed to have a special relationship with his mother and was able to calm her in any situation. He often took her walking in the facility’s gardens and would sit outdoors with her, just talking or laughing. He was always able to understand her and was likewise always able to get her to listen to him, despite her hearing loss. According to Simon’s wife, Norma, the two of them had a very special connection in that he would always appear at the nursing home just when Tereza seemed to need him most.

Sadly for all, Simon passed away in 1994 of bone cancer. His dying request to Norma was to never tell Tereza that he had died, to keep his death from her. Norma and all the rest of the family agreed, though it is very painful for them to keep up the pretense. Norma visits her now, and when Tereza predictably asks why Simon hasn’t been coming, Norma lies and says he is at home in bed with a bad back. Each time, Tereza accepts this story, but she is saddened by it and seems to feel his loss deeply.

(Originally written: May 1995)

The post “She Lived to be 100!” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

August 25, 2016

The Colorful Life of Irene Diefenbach

Irene Diefenbach was born on September 2, 1910 in Pennsylvania to Slovak immigrants, Karol and Danica Dalibor. The Dalibors worked on a small dairy farm, but when Irene and her two siblings were still very young, the family moved to Phillips, Wisconsin, which had a large Slovak population and many dairy farms in the surrounding area. Karol was able to purchase his own farm there, which Danica helped to run.

Irene Diefenbach was born on September 2, 1910 in Pennsylvania to Slovak immigrants, Karol and Danica Dalibor. The Dalibors worked on a small dairy farm, but when Irene and her two siblings were still very young, the family moved to Phillips, Wisconsin, which had a large Slovak population and many dairy farms in the surrounding area. Karol was able to purchase his own farm there, which Danica helped to run.

Irene attended grammar and high school, but as there were few job prospects for her in Phillips, it was decided that she should go to Chicago to find work. Somehow it was arranged that she would stay with an old German lady, a Mrs. Glockner, who lived on the Southside while Irene worked cleaning houses for the wealthy residents of the North Shore. In her free time, Irene attended a design school to learn how to design clothes. She became quite skilled at this and actually designed some dresses for Mrs. Glockner and her friends.

Irene was apparently very attractive in her day and had many beaux and would-be suitors. She was forever going on dates, and a routine was quickly established. Irene’s date for the evening was required to pick her up at Mrs. Glockner’s and sit for a time and make polite conversation before he was allowed to leave with Irene. The next morning, Irene would then tell Mrs. Glockner all about her evening out, and then the two would discuss what they both thought of the young man in question.

One time, so the story goes, Irene brought home a young man by the name of Gilbert Diefenbach, whom Irene thought so boring on their first date that she didn’t even bother to bring him up at breakfast the next morning. Mrs. Glockner spoke up, though, and, based on what she had gleaned from Gilbert when he had come to pick her up the night before, told Irene that he was the one she should marry. Irene was stunned by this announcement, but she regarded Mrs. Glockner’s opinion so highly that she reluctantly gave Gilbert another chance. Apparently, he was not as boring the second time, and they started dating regularly after that. They eventually married in 1939, when Irene was 29 and Gilbert was 32.

The young couple moved to what was then a little country town called Mount Prospect and had their first baby, Phyllis. Following Phyllis, Irene had three miscarriages before she finally gave birth to another daughter, June. Right at about this time, Irene’s parents’ health began to fail severely, and Karol found he could no longer farm. Gilbert himself had grown up on a farm, so he suggested that he and Irene and the two girls move up to Phillips to help her parents and to prevent the farm from being sold. They tried their best for four years to run the farm, but it was too difficult for Gilbert to do on his own and they couldn’t afford outside help.

Eventually, Irene and Gilbert had to give up, and the farm was sold. They moved back to Chicago, then, and found an apartment in Andersonville. Their building was nicknamed “The Castle” and was apparently very beautiful. The Diefenbachs rented the first floor apartment, which happened to be the one which contained the door leading to the cellar. Apparently, the woman who had previously owned the building had made her own liquors in the basement during prohibition and converted the basement into a huge wine cellar. When the woman vacated the building, she apparently left behind all the wines and liquors, assuming they had all spoiled, as did everyone else. Irene, however, was determined to investigate the cellar herself. As predicted, most of the wine had indeed spoiled, but she did come across some excellent cherry cordial. Irene took great delight in discovering these hidden treasures. She says they were an excellent vintage and used most of them as gifts over the years.

After June was born, the doctors told Irene that she shouldn’t have any more children, as it would be too risky, but seven years after June, Sophie was unexpectedly born. Irene was happy staying home with her girls while Gilbert worked as an insurance salesman. Irene was a very active member of the community and of her church, St. Joan of Arc. She was a member of Opus Dei, the Catholic Ladies Slovak Union, a neighborhood gardening club, and was a leader in the Girl Scouts. She designed and sewed all of her own clothes and the children’s and loved dancing, music and intellectual conversations.

1963 proved a year of great upheaval for Irene. Not only was that the year that Gilbert passed away, but that was also the year that Phyllis got married and moved to New York. A year later, June married as well and moved to Boston, leaving Irene and Sophie alone. Irene decided to go back to work and got a job at Marshall Field’s doing alterations. She also worked on the side, producing her own designs, and was also a swimming instructor. Later she left Fields for Carson’s, and worked there until 1970, when Sophie got married and moved away, too.

At that point, Irene was sixty, and Phyllis, worried about her mom being all alone, persuaded Irene to come and live with her in New York. Irene agreed, but insisted on driving her car all the way to New York, on her own, so that she would still have a car at her disposal at Phyllis’s. After only a couple of years, however, Phyllis’s husband was transferred to Naperville, Illinois, so they all moved back to the Chicago area. Irene got her own apartment, then, at Four Lakes in Lisle, where she stayed for fourteen years. In that time, Phyllis and her husband were transferred again, this time to Washington, but Irene remained behind in Lisle.

In 1980, Irene suffered a stroke, which paralyzed her whole right side. She was determined, though, “to make a comeback” and live independently. Amazingly, she did indeed learn to walk, read and write all over again and even managed to make a wedding dress for a family friend, a huge personal achievement.

Irene remained on her own until 1993 when she began to finally need more assistance, and Sophie helped her to move into a retirement complex, which Irene subsequently hated. Irene, herself 83 at the time, was disgusted that she was surrounded by “old people” and became depressed. Her daughter, Sophie, believes that this was “the beginning of the end.” At the retirement home, Irene experienced six more mini-strokes and a seizure. Likewise, while attempting to get out of bed one morning, Irene fell and fractured several vertebrae. She was transferred to the hospital and then released to a nursing home under hospice care.

Irene is currently not able to communicate very well, though she seems alert. Sophie is convinced that her mother does not realize she is in a nursing home and that it would “instantly kill her” if she knew. Sophie is racked with guilt and sorrow regarding the whole situation and continuously urges the staff to provide intellectual stimulation for her mother. Irene, for her part, when awake, seems very pleasant and amiable, happy with whatever is given to her.

The post The Colorful Life of Irene Diefenbach appeared first on Michelle Cox.

August 18, 2016

He Had “A Complex” About Being Around People

Albert Daelman was born on September 5, 1916 on a farm in LaSalle, Illinois to Ernst and Willemina Daelman, Dutch immigrants. Ernst was a farmer and was what Albert describes as “a hard-working man.” His mother, Willemina, cared for their six children. Albert managed to attend high school for a year and a half before he quit to get a job. When the WWII broke out, he enlisted in the army and was stationed in the Philippines.

Albert Daelman was born on September 5, 1916 on a farm in LaSalle, Illinois to Ernst and Willemina Daelman, Dutch immigrants. Ernst was a farmer and was what Albert describes as “a hard-working man.” His mother, Willemina, cared for their six children. Albert managed to attend high school for a year and a half before he quit to get a job. When the WWII broke out, he enlisted in the army and was stationed in the Philippines.

Upon being discharged and returning home, Albert decided to move to Chicago and found work as a machinist in various factories. At one point, he decided to take a vacation to San Francisco and happened to meet a beautiful young Mexican woman, Benita Caldera, who was also vacationing there. Albert took her out to dinner and afterwards asked her if he could write to her. Benita agreed to give him her address, though she had a boyfriend back in Mexico. She lived in a small town there and worked as a manager of a furniture store. She and her sister lived together with their invalid mother, whom they both took care of.

True to his word, Albert wrote to Benita as soon as he got back to Chicago and continued to write to her every week. The problem, however, was that his letters were mostly in English with a few Spanish words thrown in for good measure. Benita was unable to read them, so she had to have a friend or sometimes the parish priest interpret them for her. Pretty soon the whole village knew of Benita’s American “lover,” which prompted Benita to begin taking English lessons.

Things continued this way until Benita’s mother suddenly died, and Albert went to Mexico to attend the funeral. He stayed for two weeks, at Benita’s sister’s insistence, so that he could get a good picture, she said, of who they were and how they lived. It didn’t take long for Albert to propose to Benita, and she accepted him. At first they planned to get married in her local church, but Albert refused to pay the steep fee the parish priest was requiring, so they went to Chicago and got married at St. Viator’s.

Benita tried hard to adjust to her new life in America, but it was difficult at first. She says that a German couple who lived next to them were very kind to her, but even so, each evening she would sneak out onto the porch and cry with homesickness. Eventually Benita got used to being Albert’s wife, however, and things settled down. She managed to get a job working in accounting at the Lions International Headquarters, and Albert continued working as a machinist, his longest employment being with Victor Products. They never had any children, though Benita says she would have liked to.

Benita vehemently states that Albert was “a good, good man—an honest man,” but, she adds, “he was not very friendly.” Albert, she says, had “a complex” about being around people. He was very shy and nervous and angered easily. Benita says that he had no hobbies and no friends and dealt with stress by drinking a lot and complaining about every little thing.

His routine was to go out to the local tavern on Friday nights after work, where he proceeded to drink away the majority of his paycheck. When he came home drunk, Benita would put him to bed and then go through his pockets to see if there was any money left. This went on until he retired, and Benita finally persuaded Albert’s doctor to tell him that if he didn’t stop drinking he would die. Apparently, this convinced Albert, and he stopped drinking cold turkey. Albert went on to get a job as a security guard at Colonial Bank on Belmont, where he worked for five years until he was diagnosed with lung cancer.

Despite having treatments, Albert’s lung cancer has spread to his brain, which seems to have further effected his personality and has caused him to be disoriented and confused. Benita tried to care for him at home for several years, but when Albert became at times verbally and possibly physically abusive to her, she could no longer cope. Not knowing what else to do, Benita recently placed him in a nursing home, which he is not adjusting well to. He continually blames Benita for bringing him here and becomes agitated whenever she visits. Indeed, on one occasion, he attempted to strangle her. His two obsessions seem to be sneaking off to bed or repeatedly saying “get me out of here.”

All of this is particularly hard on Benita, who claims that she loves him still, despite his verbal abuse. “It is not the real Albert,” she says, and is overwhelmed with grief and guilt that she cannot help him more.

(originally written 3/96)

The post He Had “A Complex” About Being Around People appeared first on Michelle Cox.

August 11, 2016

“Well, It Wasn’t Sweet 16!”

Celina Abelli was born on August 18, 1898 in a small Polish village to Wera Pakulski and Olek Zuraw. Celina says the family lived on a farm with wonderful fruit trees. Olek also worked as a carpenter and cut hay on local farms. Her mother cared for the six children, of which Celina was the youngest. There was a total of nine children, but three died of typhus fever before Celina was born: Konrad, who was seven, and Lew and Marek who were twin baby boys.

Celina Abelli was born on August 18, 1898 in a small Polish village to Wera Pakulski and Olek Zuraw. Celina says the family lived on a farm with wonderful fruit trees. Olek also worked as a carpenter and cut hay on local farms. Her mother cared for the six children, of which Celina was the youngest. There was a total of nine children, but three died of typhus fever before Celina was born: Konrad, who was seven, and Lew and Marek who were twin baby boys.

When Celina was just four and a half, her father died as well at age forty-four of pneumonia. Celina has just one memory of him, which was of him lifting her up into the fruit trees to pick a piece of fruit for herself. After Olek’s death, all of the children had to find work. Celina went to grammar school and then found work sewing or doing “any little thing that came along.”

As a family, they would often go into town where dances were frequently held. It was there that they met a young man, Emil Brzezicki, whom Celina’s sister fell madly in love with. Unfortunately, however, Emil only had eyes for Celina, who for some reason hated him. Emil wouldn’t give up, however, and began following Celina everywhere she went and even brought her flowers. Celina won’t say exactly why she didn’t like Emil or why she then mysteriously agreed to marry him when she was twenty-one. The fact that she does not want to talk about it at all suggests something dark may have happened between them, and no one in the family can shed any light on it. When asked if she grew to love Emil, she says, “I didn’t hate him, but I didn’t love him, either. It was something in between. We got by.”

For the first year of their marriage, Celina and Emil lived with Wera before moving to a neighboring town. They eventually had eight children, but two died when they were small. Celina doesn’t have much to say about their life in Poland during the war, just that after it was over, the whole family moved to America around 1950. One son was delayed in Poland for a time, but then joined them in Chicago, where they had managed to settle, before he left again to join the American army.

Now in Chicago, Emil found a job working in a furniture factory, but had to quit after only four years because he was diagnosed with emphysema. Realizing that his prognosis was not good, Celina knew she had to find some sort of employment and managed to buy a little corner grocery shop. She ran the store and nursed Emil, who eventually died seven years later in 1961. Celina kept the store running even after Emil died, but she says it was hard because it was the era when big chain grocery stores were buying up all the little neighborhood shops. After two years, she gave in as well and sold it. After that, she found work as a nurse’s aide to not only pay the bills, but to pay off Emil’s funeral costs.

In 1970, Celina married again—this time to a quiet, mild-mannered Italian man, Stefano Abelli, who was eight years her senior. When asked if she loved Stefano, if he was perhaps the love she had always been waiting for, her reply was “Well, it wasn’t sweet 16!” The relationship was short-lived, however, as Stefano died of cancer after only a year and a half of marriage. Following his death, Celina lived alone for many years. Two of her daughters died, one of a heart attack at age fifty-five and one of cancer in her forties. Her other children are scattered in other parts of the country, so that as her health has begun to decline, Celina has been relying more and more on her grandchildren.

In recent years she has had a stroke and a fractured spine, among other things, which has caused her to have to live with various grandchildren. When she needed an operation on her leg, however, she was hospitalized and then sent to a nursing home. She wishes she could go home to one of her grandchildren’s houses, but she realizes this is unrealistic. She is not making a smooth adjustment, however, and says she is in a lot of pain, calling out frequently because of it. However, if anyone sits and talks with her at length, even for an hour or longer, she never once complains of pain or cries out.

Celina says that she has no hobbies because she never had time for fun; she was always working. Occasionally she would enjoy a movie or music, but her biggest interest was probably the church. She says that she can recite the whole mass in Polish without one mistake. Celina says that she has always prayed from the time she was a little child and has gotten a lot of strength from prayer over the years. She says that “Jesus has always been with me,” and that “I’m very religious. Very deep. But I lost a lot of faith when I came here because it’s hard to stay religious in a country like this.” Indeed, she says that when she remembers how life used to be in Poland “I am bitter” and “I want to die.” She cries easily and seems particularly fixated on the space shuttle explosion. She mentions it often and cries about it frequently.

Attempts have been made to involve her children, but they are all older themselves and have their own health problems. One son recently sent her twenty dollars in a card, which she was thrilled with and proudly showed to all of the staff. Overall, however, Celina remains depressed and despondent, reluctant to make a new life, one more time, in the nursing home in which she currently finds herself.

The post “Well, It Wasn’t Sweet 16!” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

August 4, 2016

“It’s Not Hard to Learn if You’re Willing”

Gonzolo Rochez was born in Texas on February 2, 1908 to Fernando and Sonia Rochez “a few years” after the U.S. “took over” Texas from Mexico. This event, however, occurred in 1848, so he is off by a few years, though maybe he views it from a different perspective. Gonzolo says that “I had a horrible life” over and over but enjoys telling his life story to anyone who will listen.

Gonzolo Rochez was born in Texas on February 2, 1908 to Fernando and Sonia Rochez “a few years” after the U.S. “took over” Texas from Mexico. This event, however, occurred in 1848, so he is off by a few years, though maybe he views it from a different perspective. Gonzolo says that “I had a horrible life” over and over but enjoys telling his life story to anyone who will listen.

According to Gonzolo, his parents died when he was five or six years old, though he doesn’t remember them or know exactly what they died from. He was sent to live with his godmother in the same village, but she was old and poor and couldn’t care for him. Not knowing what else to do, she sent him to an orphanage run by nuns. Gonzolo hated life at the orphanage. He says that he was taught to read and write, but that he was always hungry, so he decided to run away. He became a street urchin, then, wandering from place to place and was constantly “bumped or kicked around.”

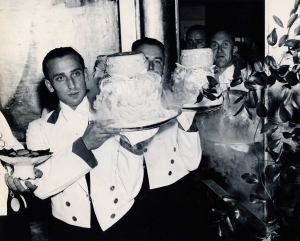

In his late teens or early twenties, Gonzolo made his way to Chicago with a few friends, where he found a job in a restaurant. Eventually, he found a place to live as well and sent for his girlfriend, Angelina Poblete, back in Texas to join him. Gonzolo and Angelina soon married, and Gonzolo began to look for a better job. Gonzolo eventually landed one at the Drake Hotel, “the best of the best” and began to earnestly “learn the trade” of being a professional waiter. For forty years, he worked as a waiter at only the best hotels: the Drake, The Blackstone, The Congress, and the Ritz-Carlton. Gonzolo says of this time period: “I was healthy; I didn’t complain; and I made a living.”

During WWII, Gonzolo joined the navy and was stationed for four years at Ottumwa, Iowa, where he quickly became the company bartender. He was apparently liked by everyone, especially the officers, and was “treated very well.” He and three other men became “untouchable” because they were so well liked by the officers and were given special favors. Once, he says, he confided to an officer that he didn’t feel like he was doing much to help the war effort and worried what he would tell people back home. The officer assured him that he was “helping as much or more with morale.” Gonzolo says that those four years in the navy were the best of his life. He would have stayed in if he didn’t have Angelina and two children, David and Eva, back at home. He did go home often to visit them, and after his four years were up, he returned to Chicago and took up his career as a waiter.

Besides being a professional waiter, Gonzolo’s other passion in life seems to have been painting. He says that one weekend he happened to be walking around State Street and saw a painter painting the crowd. Looking over the painter’s shoulder, he decided it didn’t look that hard, so he went to a dime store and bought some paint and brushes. He was impressed with what he produced and took up painting in earnest. It became his life-long hobby. Apparently, a wealthy business man who once saw Gonzolo’s paintings offered to pay for him to take art classes, but Gonzolo refused his offer, saying “I want to paint what I want to paint, not what they tell me.” Gonzolo claims that both the Drake and the Congress Hotels have some of his artwork.

Gonzolo’s daughter, Eva, “paints” a very different picture of her father from the story he provides. She says that he was a very controlling, domineering, manipulative man who beat Angelina and David, but never her. The story of refusing art classes, she says, proves how much control he needed, that he would never subject himself to any outside authority. “No one could tell him what to do,” Eva says. This is why, she says, he could never belong to a church. He was baptized Catholic, but doesn’t believe in God now. Gonzolo says that “religion is an invisible weapon of the government to control the masses.” Instead, he believes in “the supernatural power of the universe” and that “when you die, you go to the same place you go to when you sleep.” Eva says that he has always been hot-tempered and did not have many friends. Indeed, when asked about any significant friendships he has had in the past, he says “friends are make believe.” When asked how he has coped with problems over the years, he says simply “I never had any problems.”

Angelina died in the late 1980’s, so Eva has been caring for Gonzolo on and off over the last several years. David has been estranged from his father for the past twenty years and lives somewhere in California. When Gonzolo’s health began to fail recently, Eva took him in to her own home for a time, but quickly realized she could not endure his domineering, manipulative ways and brought him to a nursing home.

Gonzolo has not made the transition well and remains very depressed. “Why should I get better?” he asks. “So I can plunge down again? I’m old. I’m 88 years old. Let me die.” He has not participated in many activities, nor does he seem interested in forming any relationships with the other residents. His favorite thing is to do is to talk about the past with the staff. He admits to liking to learn new things, however, which he says he has always tried to do throughout his life. “It’s not hard to learn if you’re willing,” is his mantra.

The post “It’s Not Hard to Learn if You’re Willing” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

July 28, 2016

She Worked Until She Was 80!

Hedda Woods was born in Chicago on October 25, 1905 to Ulla Ostberg and Birger Haugen, both immigrants from Norway. Soon after they married, Ulla and Birger decided to come to America to try a new life. Family legend has it that when they came through Ellis Island, Ulla, the stronger of the pair, herself carried their trunk on her back! From Ellis Island, the Haugen’s made their way to the west side of Chicago. Birger got a job “working with figures,” meaning he was a sort of draftsman, designing machinery. Ulla cared for their seven children: Signe, Carl, Egil, Tanja, Erling, Finn and Hedda, all of whom survived childhood.

Hedda Woods was born in Chicago on October 25, 1905 to Ulla Ostberg and Birger Haugen, both immigrants from Norway. Soon after they married, Ulla and Birger decided to come to America to try a new life. Family legend has it that when they came through Ellis Island, Ulla, the stronger of the pair, herself carried their trunk on her back! From Ellis Island, the Haugen’s made their way to the west side of Chicago. Birger got a job “working with figures,” meaning he was a sort of draftsman, designing machinery. Ulla cared for their seven children: Signe, Carl, Egil, Tanja, Erling, Finn and Hedda, all of whom survived childhood.

Hedda was the youngest and says that she usually got her way, being a very stubborn child. She graduated from Austin High School and got a job as a secretary for the Pullman Railroad Company. From there she went to work for Great Western and then to the Milwaukee Railroad Company, where she worked until she was sixty-five. According to her nephew, Dennis, Hedda always took her job very seriously. She worked hard and was always on the lookout for ways to advance herself, both professionally and personally.

Birger passed away around 1932, and Ulla died nearly twenty years later in the 1950’s. At the time, Finn, Erling, Tanja and Hedda were still living at home, so they continued on this way, even after both parents died. It was right about this time, however, that Hedda met a man by the name of Dr. Nelson Woods at a dance. Hedda says that the group of friends she was with that night met up with another group, of which Nelson happened to be a part. The two hit it off right away and began dating. When Hedda was forty-six, they married and bought a home in Elmwood Park.

Hedda kept their house “neat as a pin” and joined many women’s groups, such as the Eastern Star, the 19th Century Women’s Group of Oak Park, and the Lyden Township Women’s Group. She also loved art, music, sewing, dancing and was a very good cook. Dennis reports that his aunt was an extremely intelligent woman but was stubborn and had a razor sharp tongue. Hedda was confirmed a Lutheran but later in life joined the Christian Science Church in Oak Park. Hedda and Nelson never had any children, and they apparently had a very happy marriage. They traveled all over the United States on vacations or attending conventions.

Hedda retired from the Milwaukee Railroad Company at age sixty-five. Her last day was on a Friday, and on the following Monday, she started at a new job at Continental Bank in the “corporate art” department. Apparently, the bank, or a division of the bank, owned a large collection of paintings, sculpture and select pieces of fine art that they rented out to various companies. Hedda was put in charge of this department and really loved it. She continued working in this position until she was eighty years old!

Hedda decided to finally retire for good in 1985 when she was walking to work one morning. She was crossing a bridge over the Chicago River when a strong blast of wind whipped through and nearly blew her over. Hedda grabbed onto a man who happened to be near her and managed not to fall. She is convinced that if the man had not been there at that moment, she would have been blown into the river and drowned. It was then that she decided she “couldn’t go to work anymore.”

Despite the fact that she was no longer working, Hedda continued to be active in her women’s groups, though she was living alone now. Nelson had passed away peacefully in 1978, when Hedda was seventy-three. She managed to continue on her own, though as time passed, she grew more alienated from people as her hearing got worse, her memory more unreliable, and her tongue sharper. Over the years, Hedda has likewise grown apart from her siblings, though several of them still live in the area. She has only remained close to her sister, Signe, and Signe’s son, Dennis, her favorite nephew. Dennis says that he has gotten along with his aunt all these years because he has always been able to ignore her critical comments. He says that she is actually a very strong, spiritual woman who got through troublesome periods in her life with prayer.

In 1992, Hedda fell and broke her hip. At that point, Dennis helped her hire a live-in nurse, an arrangement that lasted almost four years, until Hedda’s finances were almost exhausted and she likewise required more care. In bringing her to a nursing home, Dennis’s hope is that she might regain some social involvement.

For her part, Hedda seems to enjoy talking with the other residents, and is rarely anxious because each day she believes that Dennis is coming to pick her up and take her home. She is very forgetful, but loves talking about the past, during which her memory is crystal clear.

(originally written 3/96)

The post She Worked Until She Was 80! appeared first on Michelle Cox.

July 21, 2016

“No One Ever Helped Me”

Jacek Sadowski was born on July 4, 1914 in a small village in Poland. He was the youngest of eight children, and his parents, Gustaw Sadowski and Hania Nowak, were farmers. Unfortunately, Hania passed away when Jacek was just one year old, so his five older sisters raised him. He attended the village school until the equivalent of eighth grade and then quit to help his father on the farm full-time.

Jacek Sadowski was born on July 4, 1914 in a small village in Poland. He was the youngest of eight children, and his parents, Gustaw Sadowski and Hania Nowak, were farmers. Unfortunately, Hania passed away when Jacek was just one year old, so his five older sisters raised him. He attended the village school until the equivalent of eighth grade and then quit to help his father on the farm full-time.

Jacek and his father did not have much time together, however, as Gustaw died suddenly in his forties of a heart attack. The farm then passed to Jacek’s oldest sister, Maria, and her husband, Alfons, whom Jacek describes as a “mean, terrible man.” One by one the siblings left the farm to find their own way, as no one could stand Alfons, until only Jacek was left. At that point, Jacek’s situation went from bad to worse. Alfons began locking him out of the house, forcing him to sleep in the barn with the pigs. He was not even allowed any bedding and was told to sleep in the straw.

Jacek soon followed his siblings’ footsteps and left the farm as well. He set off for the neighboring farms, hoping to get hired as an extra hand. He eventually managed to find a place, but was still required to sleep in the barn, though he was at least given a cot and bedding. Things continued this way for a couple of years for Jacek, during which time his hatred for Alfons grew, until the Germans invaded and took Jacek captive. From there he was sent to a farm in Germany to work. He was thankful that he was not conscripted into the German army and explains that because all of the German men were away fighting, there was no one left on the farms to produce food for the army, much less the normal citizens. Many of the prisoners of war were thus sent to the farms to work.

Despite the fact that he was technically a prisoner, Jacek enjoyed his time in Germany and says that he had better living conditions there than what he had ever had in Poland. When the Allies arrived to liberate them, he was reluctant to go back to Poland. He was sent to various camps run by the Allies and in one of them met a young woman by the name of Rozalia Salomon. The two of them married while still in Germany and took a train ride for their honeymoon through the German countryside because Jacek thought the scenery so beautiful.

When they returned to the camp, Jacek and Rozalia decided to apply for immigration to the United States with the help of the Allies. A sponsor in America came forward and vouched for them, saying that an apartment and a job awaited them in Chicago. When they eventually arrived, however, there was no job or apartment for them at all. They were found wandering on Milwaukee Avenue by an old Polish woman who offered them an “apartment.” Desperate, Jacek and Rozalia took it and were shocked to discover that it was really just one room with a bed frame but no mattress.

Jacek quickly set out to find a job and was hired to make cabinets for a company at Milwaukee and Belmont. At the time, he was 36 years old, and he stayed at that job for 34 years, retiring when he was 70. Jacek and Rozalia were eventually able to find a series of better apartments until they moved to one on Greenview, where they stayed for over twenty years.

Jacek and Rozalia had two daughters, Maggie and Ruth. Rozalia stayed home with them and never worked outside the home, as she was always in very poor health. In fact, Jacek says bitterly, he had to do everything inside the house and out, including caring for the girls, because Rozalia was always so sick.

Jacek says that he never really had any hobbies because he never had time. His favorite thing used to be drinking a cold beer on a hot day. He says that people have no choice in their lives, that “things or fate just happen to you.” He says that “I’ve had a bad life” and can’t seem to shake his bitterness, which Maggie and Ruth say he has had all his life. He blames what he calls his “bad fortune” on the fact that his parents died so young and on his brother-in-law, Alfons, whom, he says, ruined his life. “No one ever helped me,” is his constant mantra.

Jacek has been living alone until very recently when he began falling frequently and then had a heart attack, which hospitalized him. His daughters, who both have families and work full-time, brought him to a nursing home to recuperate from surgery, though they believe this to be a permanent placement. Maggie and Ruth have tried to talk about this with him, but he is not interested in listening. They say that their father is very stubborn and has always had a negative attitude, which also has made it difficult for them to care for him as the years have gone on. As expected, Jacek is not adjusting well and says that he can’t enjoy himself here because “it’s not my home.”

The post “No One Ever Helped Me” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

July 14, 2016

Three Husbands, a Deceitful Son, and the Pigeon Club

Marie Bosko was born on July 4, 1912 in Chicago to Dusan Cizek and Alena Holub. Both Dusan and Alena were immigrants from Czechoslovakia, but they met and married in Chicago. Dusan worked as a cabinet maker for John M. Smythe, and Alena cared for their eight children, though two of them died. Their first baby, Alice, lived only one month, and their fourth child, Joseph, died as an infant as well. Alena joined them in their graves just two days before Christmas in 1939. She was only fifty years old, and no one seems to remember what she died of.

Marie Bosko was born on July 4, 1912 in Chicago to Dusan Cizek and Alena Holub. Both Dusan and Alena were immigrants from Czechoslovakia, but they met and married in Chicago. Dusan worked as a cabinet maker for John M. Smythe, and Alena cared for their eight children, though two of them died. Their first baby, Alice, lived only one month, and their fourth child, Joseph, died as an infant as well. Alena joined them in their graves just two days before Christmas in 1939. She was only fifty years old, and no one seems to remember what she died of.

Dusan eventually remarried, and his new wife, Olga, had three children of her own. Marie says she was “alright” as a stepmother, but that she “had her moments” and favored her own children over the six of them. There was never enough to eat, Marie says, though Olga somehow managed to remain obese. She was not surprised, she says, when Olga died young of a heart attack. Her father lived to be 86 and died, Marie says, of “a broken heart.” She doesn’t think her father ever really got over the death of her mother and that he never really loved Olga, but had married her just so that he would have someone to take care of the kids.

Marie went to school at St. John’s until seventh grade and then quit to get a job. She had to give some of the money to Olga, but she was eager to save up enough to move out on her own. At thirteen, she began working in a factory that made hairpins. At some point, she met Lester Soat, though she can’t remember exactly how. She thinks it may have been through friends. She eventually married Lester, who worked as a file clerk at GM. Marie continued working at the hairpin factory for a time before quitting to work at Arco, a factory that made playing cards. In all, Marie worked in factories for over 39 years, even after their son, Morris, was born in 1931.

Marie and Lester seemed to have a relatively quiet life. Marie says she loved him, but they were not overly expressive of their feelings for each other. “We didn’t need to show it,” she says. Marie does not say much about her years as a mother. She says that Morris was always a troubled boy and was often bullied. He left home at nineteen and traveled around the country. Marie says she tried to keep in contact with him over the years, but it was hard. Even after Lester died at age 43 in 1950, Morris did not come home.

Two years later after Lester’s death, Marie married Victor Lange, who had been a cook in the service. Marie says that he drank too much, but insists he wasn’t an alcoholic. They had a somewhat rocky relationship, and he died of cirrhosis of the liver after only five years with Marie.

Victor died in February of 1957, and by November of that same year, Marie was married again. This time to Charlie Bosko, who worked in a paint factory. Marie and Charlie had a much better relationship and enjoyed each other’s company very much. Charlie belonged to a pigeon club, and introduced the hobby to Marie. Marie joined the club as well, and the couple often spent their vacations traveling with their pigeons to different competitions. Marie is very proud of the fact that they even won some medals over the years. Her other pastimes were baking and crossword puzzles.

Charlie and Marie were together the longest—27 years—until he, too, died at age 67 of congestive heart failure in 1984. After that, Marie remained alone. She had retired from factory work in 1976, and struggled to find something to occupy her time, the pigeon club having disbanded years before. With Charlie gone, she seemed lost and unable to find a new hobby. She suffered a stroke in 1987 and another in 1988. At this point, her son, Morris, who had been absent from her life all these years, reappeared on the scene.

Morris managed to convince Marie to sell him everything, including the house, and to turn over all assets to him. Once all of the transactions were completed, Morris then proposed they move to Las Vegas and live together there. Marie was lonely and hoping to renew her relationship with her son, so she agreed. Not surprisingly, it only took a couple years for Morris to gamble it all away.

Both of them impoverished now, Marie was hospitalized in the early 1990’s with pneumonia. By a weird twist of fate, it was while she was in the hospital that Morris also contracted pneumonia and died of it at home. Marie was utterly crushed by his death. Although he had swindled everything from her and reduced her to poverty, she loved him still and had clung to him as the only thing she had left in the world. Marie managed to attend Morris’s funeral, though she was very weak, and then went to stay with her sister, Gladys, who was still living in Chicago. Gladys has tried her best to care for Marie, but the strain has recently become too much for her, forcing her to put Marie in a nursing home.

Marie seems to be adjusting relatively well, though she says she is lonely and often still cries for Morris. She is reluctant to form any new relationships and spends most of her day reading large-print books and watching “Days of Our Lives.”

The post Three Husbands, a Deceitful Son, and the Pigeon Club appeared first on Michelle Cox.

July 7, 2016

She Sold Her Paintings From Village to Village

Jadwiga Sokal was born on February 26, 1914 in Poland to Wladek and Kasia Majewski. Jadwiga went to grammar school only and then found a job in a pastry shop, where she often waited on a young man, Kasper Sokal, who came in to the shop quite often. Kasper was a widower with two older children and was 14 years Jadwiga’s senior. The two eventually fell in love, however, and married on July 25, 1935. Jadwiga was 21 by this point, and Kasper was 35.

Jadwiga Sokal was born on February 26, 1914 in Poland to Wladek and Kasia Majewski. Jadwiga went to grammar school only and then found a job in a pastry shop, where she often waited on a young man, Kasper Sokal, who came in to the shop quite often. Kasper was a widower with two older children and was 14 years Jadwiga’s senior. The two eventually fell in love, however, and married on July 25, 1935. Jadwiga was 21 by this point, and Kasper was 35.

Kasper worked for the railroads, and in the first years of their marriage, the young couple moved around a lot to avoid the Germans and the war in general. Kasper had served in WWI and had been wounded, for which he had received Poland’s highest medal. He was “drafted” for the Second World War, as well, because of his job with the railroad, but managed somehow to escape it. Kasper and Jadwiga moved to Dubno for a time, and there had their first child, Tomasz. After the war, however, Dubno became Russian territory, so they moved to Sanok and then later to Nysa, where their second son, Radek, was born in 1952.

Kasper continued working for the railroads his whole life. Jadwiga, besides caring for their two sons and Kasper’s two older children, made extra money by painting pictures and selling them from village to village. She was quite a talented artist, apparently, and became quite well known in the area for her pictures.

Jadwiga’s other passion in life, it seems, was cooking. Radek relates that their house was perpetually full of friends and neighbors, with Jadwiga in the center of it all, cooking for them. She also loved to crotchet. Jadwiga, according to her sons, was a very active, cheerful, pleasant woman who continually had to be doing something. She was always up for new things, and in her 60’s, she got her first paying job since her pastry shop days, working in a daycare—a job she loved.

In 1964, Tomasz decided to take a bold step and immigrate to America, eventually settling in Chicago. After a number of years, he returned to Poland, intending to stay, but after a couple of years decided to go back to America. In 1974, Radek joined him. Tomasz’s stories of America excited him, and he didn’t feel that Poland had much left to offer. Radek was reluctant to leave Jadwiga and Kasper on their own, however, but at that time they were still in good health and seemed happy, so he decided to go. Jadwiga was still working in the daycare, and though retired, Kasper continued to show up at the train yard every morning, unable to pull himself away.

In January 1975, however, Kasper died suddenly of heart and lung problems. Jadwiga mourned the loss of him, as they had truly been in love and had had a happy marriage. She continued to live on her own in Poland for another three years until Radek and his wife convinced her to move in with them in Chicago.

Jadwiga seemed happy living with Radek’s family and soon continued the tradition of cooking big meals and desserts and constantly inviting friends and neighbors to come and eat. Radek tried to persuade her to continue painting, but she always responded by saying “that part of my life is done now.” She still did her crocheting, though, and also loved music, singing, and pets of any kind. And much to everyone’s surprise, she got a job for a number of years caring for elderly people, a job she especially enjoyed because she could bake and bring them pastries.

Jadwiga has remained in good health until very recently when she required heart surgery at age 80. After her time in the hospital, she was transferred to a nursing home to recover. At first, Radek assumed this would be a temporary placement, but Jadwiga is significantly weaker now than she was and may require permanent help and placement. Jadwiga , however, is choosing to believe she is going back to Radek’s house at some point, and is therefore very content with her surroundings at the moment. She is happy to talk with the other Polish residents and very much enjoys bingo.

The post She Sold Her Paintings From Village to Village appeared first on Michelle Cox.