Michelle Cox's Blog, page 30

October 26, 2017

“I’d Take Those Days Back in a Second”

Louis Dubois was born on March 6, 1913 in Chicago to Louis Dubois Sr. and Hilda Kempf. Both of Louis’s parents were also born in Chicago, though his father’s family had emigrated from France, and his mother’s family was an Irish-German mix. Louis Dubois Sr. was a star salesman for Armour Foods & Co., and the family lived on the south side near Comiskey Park. When Louis was just three years old, Hilda had another baby, William, but she died during childbirth. Louis isn’t sure, but he thinks his mother was probably only in her early twenties when she died. Louis Sr. began drinking heavily as a result, and Hilda’s mother had to step in to help raise Louis and Will. His father was able to “keep it together,” at work, but he became “a drunken idiot” at home each night. In that way, it was good that his grandmother frequently cared for them, but she was a “strict, hard woman,” Louis says.

Louis Dubois was born on March 6, 1913 in Chicago to Louis Dubois Sr. and Hilda Kempf. Both of Louis’s parents were also born in Chicago, though his father’s family had emigrated from France, and his mother’s family was an Irish-German mix. Louis Dubois Sr. was a star salesman for Armour Foods & Co., and the family lived on the south side near Comiskey Park. When Louis was just three years old, Hilda had another baby, William, but she died during childbirth. Louis isn’t sure, but he thinks his mother was probably only in her early twenties when she died. Louis Sr. began drinking heavily as a result, and Hilda’s mother had to step in to help raise Louis and Will. His father was able to “keep it together,” at work, but he became “a drunken idiot” at home each night. In that way, it was good that his grandmother frequently cared for them, but she was a “strict, hard woman,” Louis says.

Like so many others, the Dubois family was hit very hard during the Depression. Louis and Will would routinely walk along the railroad tracks and pick up stray bits of coal to help heat the house. They were terribly poor, Louis says, but he would “take back those days in a second.” Louis went to high school and eventually found work as a quality control clerk at Mills Novelty, a world leader in jukebox technology. He had a few hobbies, such as going to movies or watching sports, but mostly, he says, he just worked.

When he was twenty-eight, he met a young woman, Betty Rose, who was a waitress in a little diner he often frequented. Though she was only seventeen, he asked her out on a date to the movies, and they eventually started seeing more of each other. When Hilda turned eighteen, they got married. Unfortunately, Betty miscarried their first child and had to have a hysterectomy immediately following, so she and Louis never had any children. Betty continued waitressing over the years and sometimes cleaned offices at night. They weren’t particularly affectionate, Louis says, but he loved her, and he thought she loved him. “We made a go of it,” he says, and he still can’t understand why, after twenty years of marriage, Betty filed for divorce. “I guess she just went a little crazy.” When asked if the divorce was hard on him, he says, “No, not really. Well, a little bit.”

Louis describes himself as a loner and that he did not make many friends. His coworkers, he reports, always called him “negative.” His closest friend over the years was his brother, Will, who also divorced later in life and who also had no children. When Will died three years ago, Louis was left very much alone and took his death hard. “Our whole family died out,” he adds, sadly. “If you have friends today, you’re lucky.”

Louis has always been incredibly healthy, though he has been smoking for sixty years. He worked in a quality control position into his eighties and just recently had to quit his job at Cushing and Co., at age 83, after being diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. He explains that he went to the doctor for a routine check-up and was told he doesn’t have much longer to live. He does not seem to want to acknowledge or talk about his terminal illness. When asked if he is sad or upset, his response is “No, not really. Well, a little bit. I wish I was at work.” After a short stay in the hospital, he was admitted to a nursing home, which he helped to choose.

Louis is making a relatively smooth transition, but he does not seem to be bothered by much. He appears withdrawn and depressed most of the time despite his comments otherwise. “I’ve had a boring life,” he says. “All I did was go to work, come home and watch TV and then go to bed.”

His favorite thing to do seems to be talking about “the good ole days,” as he calls them. He is thoroughly disgusted with modern society and longs for the days when people knew their neighbors and smiled at people on the streets. “No one locked their doors back then,” he says. “In the summer time, we all slept on the beach for the breeze, and no one murdered you.”

He seems aware of his negativity, saying “no one wants to talk to me because I’m depressing,” but likewise doesn’t seem to be able to control it. He says he wants to die and “get it over with.” Staff at the home are attempting to connect him with other residents who might also like to talk or to watch sports on TV with him.

(Originally written: June 1996)

The post “I’d Take Those Days Back in a Second” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

October 19, 2017

He Made the Beautiful Wood Interiors of Luxury Train Cars

David Doubek was born on January 24, 1906 in Czechoslovakia to Dusan Doubek and Bessie Fiala. David does not remember what type of work his father did, just that he died when David was nine years old. Left alone with three children, Bessie tried for a few years to make it on her own before she decided to immigrate to America. Her brother, Paul, was living in Chicago and had written her many letters, urging her to come. Bessie finally worked up the courage to make the journey, taking David, who was then fourteen, and her youngest daughter, Simona, with her. Her oldest daughter, Renata, reluctantly stayed behind, as she was already married, and her husband’s health was too poor for them to make the journey.

David Doubek was born on January 24, 1906 in Czechoslovakia to Dusan Doubek and Bessie Fiala. David does not remember what type of work his father did, just that he died when David was nine years old. Left alone with three children, Bessie tried for a few years to make it on her own before she decided to immigrate to America. Her brother, Paul, was living in Chicago and had written her many letters, urging her to come. Bessie finally worked up the courage to make the journey, taking David, who was then fourteen, and her youngest daughter, Simona, with her. Her oldest daughter, Renata, reluctantly stayed behind, as she was already married, and her husband’s health was too poor for them to make the journey.

While still in Czechoslovakia, David had learned carpentry and cabinet making, as well as how to play the violin. When the family arrived in Chicago, he quickly got a job for Northwestern Railroad making all of the wood furnishings for their train cars and went to night school to learn English. He began as an apprentice and quickly worked his way up to being a foreman.

When David was twenty-three years old, he married Marie Horak, who was just eighteen. Marie was David’s first friend in America; she met him when she was nine and he was fourteen. Though their families lived on opposite sides of the city, they both went to the same Czech church, and David remembers teasing her by pulling her braids any chance he got.

By the time Marie was sixteen, however, they had progressed to going on dates, though they were infrequent, not only because they lived so far apart, but because neither of them had very much money to spare. Likewise, they both worked a lot. Besides taking care of her five younger brothers and sisters and her mother, who was ill much of the time, Marie sometimes worked, on and off, as a secretary or as a waitress. Usually, then, their dates consisted of simply walking in a park together or going to a free flower show or perhaps Riverside Amusement Park whenever they got the chance. Still, they managed to fall in love.

Unfortunately, the year David and Marie got married, 1929, the stock market crashed. David lost his job at the railroad, and Marie lost her job, as well, which, at the time, was in a factory. “It was a real shame,” says Marie, that David lost his job because he was a truly gifted carpenter. Sometimes on a Sunday, he would take her to the rail yard where he worked and show her some of the first-class cars he had worked on. “They were beautiful!” Marie says. “Like works of art.” But with the country plunged into the Depression, there was not as much of a need for wood-trimmed, luxury train cars. Thus, he and many other skilled carpenters were let go.

David and Marie lived with Marie’s family for about ten years until they could get back on their feet. David eventually got a job as the foreman of a maintenance crew at Butter Brothers downtown on Canal Street, and Marie found another secretarial job. Eventually, they were able to move into their own apartment, just down the street from Marie’s mother, where they remained for the rest of their married life. In fact, Marie, now age 81, lives there still.

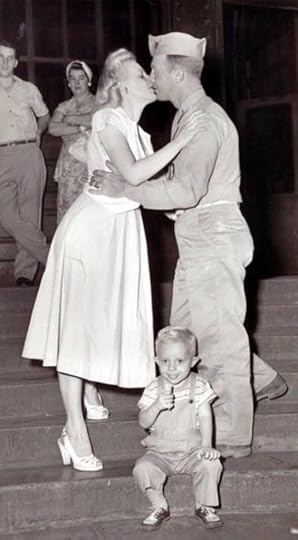

Not long after they moved to their new apartment, Marie got pregnant with their first child, David Jr. They had begun to think they weren’t able to have children, so they were overjoyed when David came along. Marie quit work to stay home with him. When the WWII broke out, however, David joined the army—against Marie’s wishes—and was eventually shipped off to Europe. Marie had no choice but to take a job in an airplane factory as a drill press operator, leaving David Jr and their new baby, Barbara, with her younger sister to watch. When the war ended, however, and David came home, Marie went back to being a housewife, and David was able to get his job back at Butter Brothers.

Marie says that they settled back into a routine and stayed at home mostly, though they were part of a card club later in life, once David Jr. and Barbara got married and left home. They dreamed of going on a tour of Europe and perhaps a cruise when they retired, but then, tragically, David had an accident when he was sixty, which altogether changed their plans.

It was 1966, and David was up on the roof, fixing a loose shingle, when he slipped and fell off. He shattered his leg, ankle and wrist and spent three and a half months in the hospital. He had a steel bar put in his leg, some bones in his wrist removed, and his ankle screwed together and was in successive casts for over a year and a half. He was forced, then, to go on full disability, and Marie had to go back to work. She was grateful that she was able to get some secretarial work, as she felt too old to work in a factory again. Laid up now, David turned to woodworking as a hobby to keep himself occupied and ended up making beautiful communion rails and pulpits for churches.

Eventually, Marie retired, too, but it was too difficult then for David to travel. To make matters worse, in 1992, when he was eighty-six, David had a stroke. He spent some time in the hospital and then one month further recovering in a Czech nursing home. Oddly, it was the same nursing home his mother, Bessie, had been admitted to at age eighty-six. Both David and Marie were thus already very familiar with the home, Marie actually having spent additional time there as a volunteer, even after Bessie, her mother-in-law, had passed away. Still, however, Marie was determined to care for David at home, so she arranged for him to be released after only being there for a month. Mostly due to her, she says, David made almost a full recovery.

Two years later, however, David had another stroke, this one much worse, which has left him unable to walk and unresponsive most of the time. He was again admitted to the nursing home, but his condition is now very serious. Marie, however, seems in denial of this and is still insisting that she will eventually take him home again like she did the last time. She spends most of the day at the nursing home, sitting by his bedside, and just recently celebrated Valentine’s Day here with him. The staff are attempting to help her process the true state of David’s health and likely prognosis. She remains dedicated, though, and says she is “optimistic.”

(Originally written: February 1994)

The post He Made the Beautiful Wood Interiors of Luxury Train Cars appeared first on Michelle Cox.

October 12, 2017

A Sicilian Immigrant With a Passion For Sports

Umberto Sartori was born on February 23, 1916 in Biscari, Sicily to Stefano and Lucia Sartori. Stefano and Lucia married very young and had six children, but when Lucia was just thirty-three, she caught pneumonia and died. Grief-stricken, Stefano decided to pack up the six children and move to America to start his life over. The Sartoris settled in Chicago, and Stefano took any job that came along until he eventually became an importer/exporter of cheese and olive oil. He died at age sixty-two when he was mysteriously hit by a car.

Umberto Sartori was born on February 23, 1916 in Biscari, Sicily to Stefano and Lucia Sartori. Stefano and Lucia married very young and had six children, but when Lucia was just thirty-three, she caught pneumonia and died. Grief-stricken, Stefano decided to pack up the six children and move to America to start his life over. The Sartoris settled in Chicago, and Stefano took any job that came along until he eventually became an importer/exporter of cheese and olive oil. He died at age sixty-two when he was mysteriously hit by a car.

Umberto attended high school and college, and even went on to get his masters in physical education from George Williams College. His first teaching job was at the University of Illinois, Chicago when it was still located at Navy Pier. When the university outgrew Navy Pier and a new facility was built at Harrison and Halsted, Umberto moved with them. While there, he continued to teach classes and also became the director of the intramural sports program, his favorites being basketball and softball.

In his free time, Umberto joined a bowling league, which is where he met his future wife, Estelle. Estelle was also on a team with her friend, Maria, and her sister, Ann, and Ann’s husband, Jim. Umberto happened to know Ann from the university and came to watch their team perform. Ann introduced Umberto to her sister, Estelle, and the two hit it off right away. They married and had two children, Tom and Nancy. “He was a good father,” Tom says. “He got us every sport under the sun and went to all of our games religiously. He had a real passion for sports. His dream when he was younger was to get into the big leagues in baseball, but he didn’t make it. So he decided to teach and coach instead.”

When Estelle died suddenly in 1973 of a heart attack, Umberto was grief stricken. He threw himself even more into his work and became almost a recluse, as Tom and Nancy had already moved out of the house. So when two years after Estelle died, Umberto began dating again, Tom and Nancy were delighted. They were happy, they say, that he seemed to be moving past the grief of their mother’s death and to seek out the company of other women. But they were a little shocked when he began to seriously date a woman by the name of Patty McConnell, who was thirty-two years his junior. Umberto met Patty at the University of Illinois, where he still taught and where Patty was also working on her masters in physical education. In 1975, when Umberto was fifty-nine and Patty was twenty-seven, they married.

After a few years together, Patty was offered a job in North Carolina, so she and Umberto and Patty’s daughter from a previous marriage, Jennifer, moved to Charlotte. After a few years there, they moved again to New Jersey for a new job for Patty. At this point, Umberto was retired. In all, they were together for about twelve years when Umberto started to show serious signs of aging and was eventually diagnosed with Parkinson’s. In the end, Patty could not deal with Umberto’s disease, and the two divorced. Patty and Jennifer remained in New Jersey, and Umberto returned to North Carolina. He lived there on his own for about four or five years until his Parkinson’s had progressed to the point that he could no longer care for himself.

Defeated and depressed, he returned to Chicago and moved in with his daughter, Nancy, who cared for him with the help of Tom and his wife, Leyla, who lived in the apartment below. Nancy and Tom tried valiantly for a year to care for their father, but it began to be too much. Whenever they would bring up the topic of a nursing home, however, with Umberto, he became very angry and was completely resistant to the idea. Nancy and Tom, struck with horrible guilt, sought out the help of a therapist to deal with their many feelings about Umberto and what to do.

Finally, they came to a decision and arranged for Umberto to be placed in a nursing home.

Umberto is not making the best transition to his new environment and is particularly frustrated by his limited physical and verbal abilities. He struggles to walk without assistance and has a hard time expressing himself now that his disease is so advanced. He is usually polite to the staff, but he has a lot of anger toward Nancy and Tom. He says that he feels abandoned and depressed, though he admits he cannot care for himself. He has yet to make any friends at the home and focuses, almost obsessively, on the physical exercise programs offered, though he is not able to fully participate. Nancy and Tom are heartbroken about their father’s condition, but continue to try to support him and visit multiple times a week, despite Umberto’s anger and sometimes indifference toward them.

(Originally written: November 1993)

The post A Sicilian Immigrant With a Passion For Sports appeared first on Michelle Cox.

October 5, 2017

From Golfing at the Country Club to Sleeping on Park Benches —The Odd Life of Joseph Hertz

Joseph Hertz was born on May 3, 1916 in Washington, D.C. to Victor Hertz and Lena Aerni. Victor was of German descent and worked as the head accountant in a large firm in Washington. Lena was of Swiss descent and cared for their two children, Joseph and Louisa, who were five years apart.

Joseph Hertz was born on May 3, 1916 in Washington, D.C. to Victor Hertz and Lena Aerni. Victor was of German descent and worked as the head accountant in a large firm in Washington. Lena was of Swiss descent and cared for their two children, Joseph and Louisa, who were five years apart.

When Joseph was very small, Victor was transferred to Columbus, Ohio. Joseph says he has only one memory from their time in Columbus. He remembers going to a park with his father and seeing some swans swimming on a small pond there. Joseph desperately wanted to pet them, so he wandered into the pond, not knowing how to swim. Miraculously, his father saw him just as he was going under and jumped into the pond to save him.

After only a few years in Ohio, Victor was again transferred, this time to La Grange, Illinois, where Joseph attended grade and high school. His father went golfing every Saturday at the country club, and when he was old enough, Joseph was allowed to go with him. Joseph was a hard worker and besides keeping his grades up, had various odd jobs, such as mowing lawns and weeding gardens. He eventually got a “real job” delivering groceries. Most of his time, however, was taken up in helping his “no good sister, Louisa.”

Louisa, five years Joseph’s senior, had married young and had a baby almost immediately. Louisa, it seems, was not the maternal type, and frequently insisted on Joseph coming over and watching the baby, Carolyn—or Carrie, as she was called—while she and her husband went out. Joseph said he loved Carrie and didn’t mind caring for her, but it was hard for him to balance everything. His dream was to go to Notre Dame and play football.

Just a few weeks shy of his high school graduation, however, a terrible accident occurred. There had been a school dance, which Joseph had attended. He had been set up with a date, and when the dance ended, he walked the girl safely home. As he was walking toward his own home, however, a car came around a curve and hit Joseph nearly head on. Joseph spent weeks in the hospital with a brain injury, and it wasn’t clear whether he would live or not. He finally came out of it, however, and began to mend, but his dreams of graduating from high school and going on to college were crushed.

His parents helped him at first, but eventually he was forced to move out on his own, though it is not clear why. With the help of his father, he was able to get a job in a laundromat, but when he didn’t show up for work one day and didn’t call, he was fired. He tried to explain to the manager that he had passed out and couldn’t call, but the manager didn’t believe him. He tried a variety of other jobs, but the same thing always happened. He would either pass out at home or on the job and would then be fired.

At one point he managed to get a job at Wallis Press, first on the cutting machine and then on the folding machine. He was very nervous that he might pass out while operating such heavy machinery, but he tried his best. Eventually, he did pass out and the owner insisted he go to a doctor. His foreman had taken a liking to Joseph and in the past had always covered for him, sometimes even punching him on and off the clock when he was really at home sick. Finally, though, when he passed out on the job and it was brought to the owner’s attention, he was forced to see a doctor. Not surprisingly, the doctor diagnosed him as “unfit to work” and said he would inform the foreman and the owner of the press that Joseph would not be coming back. Depressed, Joseph agreed and did not go back to say goodbye.

Several years later, while walking down a street in Chicago, Joseph felt a shove from behind and turned to see his old foreman from the press, who was clearly upset with him. He accused Joseph of walking off the job after he had done so much for him. Joseph hurriedly explained that the doctor he had been forced to go to had diagnosed him as “unfit to work” and that he was supposed to have sent some kind of a report to the factory verifying that. The foreman claimed that they had never received a phone call or a letter from this doctor, which had led them all, at the time, to believe that Joseph had merely quit. Joseph apologized for the misunderstanding, and the foreman felt so bad for him that he offered him a “light duty” job in the mail room if he wanted to come back. Joseph thanked him for the offer, but ultimately turned him down.

As it was, Joseph was at an all-time low. He claims that in his twenties and thirties, he was married two times, but that both wives had died. His first wife, Agatha, was a nurse he met while in the hospital after being hit by a car. He says that she died, however, soon after their marriage, and that he eventually met another nurse, Marion, whom he also married. Marion also apparently died, leaving Joseph alone in the world. His parents died young, and Louisa and family had since moved to Kansas and did not maintain contact with him.

Without a job or any hopes of ever being able to hold one down, Joseph became homeless and eventually began sleeping on park benches. One night, after some cops came by and tried to get him to move on, a strange man approached him and asked him if he needed a place to stay. Joseph said yes, but told the man that he had no money. The man asked him if he could stand living in the park for just one more night until he could get a place ready for him. Joseph said yes and the next day showed up at the man’s apartment, as instructed. Joseph says that there were many homosexual men living in the building, so he decided to stay with them for only a couple of nights. Whether through their help or on his own, he was eventually able to get a job at a restaurant and then at a newsstand.

Joseph seemed to be able to handle working at the newsstand pretty well. One customer became a sort of friend and eventually told Joseph that he knew a woman he would like to introduce him to if he was agreeable. Joseph said yes and, with his friend, went to meet the woman, Betty Lindh, who was living with her aunt, Thelma Kloburcher. Betty had been married before, Joseph learned, but her husband had routinely beat her, so she eventually divorced him. She worked at the Harvard Insurance Company, but, like Joseph, had been in a car accident, which left her “a cripple,” and she used a walker to get around.

Joseph and Betty took an instant liking to each other and married quickly, each one willing to overlook the other’s disability. Joseph accordingly moved in with Betty and Thelma, but it soon became evident that this arrangement wasn’t going to work out. Thelma became extremely jealous of any attention the Joseph and Betty gave each other, culminating in Thelma one day breaking a plate over Betty’s head.

After that, Joseph and Betty took a room at a boarding house at Clybourn and Fullerton for $16 a week, and later moved across the street to a one-bedroom apartment for $18 a week. According to Joseph, he and Betty had a very tumultuous sort of relationship. Joseph says that they loved each other very much, but that they had a lot of problems, the biggest one being Betty’s alcoholism. Joseph claims that she often did strange, unpredictable things, like waiting for him with a knife one night when he came home from work. She was furious with him for something, and Joseph thought she was waving the knife at him to make a point of scaring him. He was stunned, then, when she actually lunged for him and stabbed him in the side. He did not go to the hospital, however, not wanting to report it. Instead he bandaged it himself and waited for it to heal. He admits, though, that he was equally violent at times, and claims to have attempted to strangle her one night. Having violent, emotional battles, often involving some sort of physical abuse, followed by a speedy, dramatic make-up, seemed to be a recurring pattern in their relationship.

In 1987, Betty’s health began to go downhill, so much so that it became apparent that she needed to be admitted to a nursing home, as Joseph could no longer take care of her. Joseph couldn’t stand the idea of being parted from her, however, so he checked himself into the same nursing home. After only six months, however, Betty passed away, leaving a grieving Joseph behind. After her death, Joseph began to hate the facility and wanted to transfer to a different home. He appealed to the public guardian’s office, saying that he was a victim of elder abuse. A guardian was appointed, and though no proof of abuse was ever produced, the guardian was able to find a new placement for Joseph.

Joseph is currently enjoying his new surroundings, though he says he misses Betty terribly. He also misses some of the staff at the other nursing home whom he had gotten used to and who had befriended him. Still, he says, “you have to make the best of it.” His favorite thing to do is to watch baseball on T.V. and particularly enjoys it if a group of other residents sit near him.

(Originally written February 1995)

The post From Golfing at the Country Club to Sleeping on Park Benches —The Odd Life of Joseph Hertz appeared first on Michelle Cox.

September 28, 2017

“He Could Make Anyone Laugh”

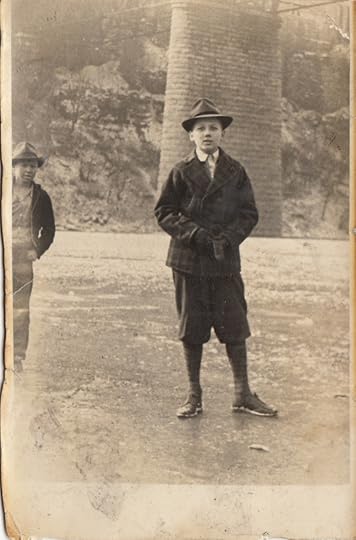

Brian Cullen, age 5, in Ireland

Brian Cullen was born on March 7, 1927 in Ireland to James and Moreen Cullen. He was the second child of five, with two brothers and two sisters. His father, James, worked in construction and on farms, and his mother, Moreen, was a housewife. Brian went to grade school and then went on to a trade school to learn to be a millwright. He eventually got a job in this field and worked in it steadily over the years.

Brian was the favorite amongst all his brothers and sisters and was always telling jokes and funny stories. He had various girlfriends, but he never married, which everyone thought odd, since he was so popular. It was just after he turned thirty that he shocked his family by telling them he was going to try his luck in America. They all thought this was another of his jokes and at first did not take him seriously. They were stunned and utterly saddened, then, when they finally realized that he was in earnest. He told them that there was no future for him—or any of them—in Ireland and that they should come with him to America. None of them wanted to leave, however, so they tearfully said goodbye to each other. Brian eventually did return, much later in life, but by then his parents and one brother had already passed away.

So in 1957, he made the journey alone to America and uncovered an aunt, Bridget Moran, who was living in Chicago. He joined a union and got a job fairly quickly, again working as a millwright and eventually found an apartment on the west side. Every Sunday, however, he would go to his aunt’s on the south side for Sunday dinner. It just so happened that next door to Bridget Moran lived a young couple, Tom and Eva, who also entertained on Sundays, usually Eva’s friend, Patsy Reid. Thus on many a Sunday, Brian and Patsy would see each other and talk. Sometimes, Brian would even drive Patsy home. They began dating and were married in 1966 when Brian was 39 years old. They moved to an apartment on the north side and eventually had one daughter, Connie.

Patsy says that Brian was a laid-back man in many ways with a wonderful sense of humor. “He could make anyone laugh,” she says, “but he liked to be in control.” Patsy says that Brian was very old-fashioned in many ways, very Victorian in his view of certain things, and was very stubborn. He saw himself as the man of the family, the provider, and thus it was his way or no way. He would not allow Patsy or Connie to get their ears pierced or to drive a car, for example, even though Connie took Drivers Ed in school. “It wasn’t that he was mean,” Patsy says, “it’s just that he thought that he should be responsible for everything. If Connie or I wanted to go somewhere, he thought it was his duty to drive us there.”

Brian was a devout Catholic who prayed the daily devotions and went to Mass each morning. He was a huge sports fan and loved basketball, baseball and hockey the most. He spent a lot of time doing yard work and always put in a big garden each year. As he got older, however, and he began to suffer from arthritis in his hip, he would have Patsy and Connie help in the garden, though only under his direction. When he retired, he and Patsy went on several trips to Ireland so that he could introduce Patsy to all the relatives and to see his home town. They also ventured to Yugoslavia, England and France. He was a heavy smoker, Patsy says, until the late 1970’s when he quit cold turkey after he accidentally lit two cigarettes at once. For some reason, that was a signal to himself to stop.

Patsy says that besides his arthritis, Brian was always in great health, which is why his recent stroke came as such a surprise. He had gone to the doctor for his annual checkup and had gotten a clean bill of health. Two days later he had a massive stroke and was hospitalized for nearly a month before being discharged to a nursing home, as Patsy cannot possibly care for him alone at home. Connie is likewise not able to help, as she now lives downstate with her husband and children. She has come up to visit once since Brian’s admission to the nursing home, but she had to return after only a few days due to her job and having her own family to care for.

Brian’s transition to the home has been relatively smooth, as he does not seem completely aware of where he is. He can answer some questions from time to time, but he is mostly unresponsive. When someone from the staff attempts to talk with him, he will look at them and take their hands, but seems unable to always answer. It is Patsy who is having a harder time dealing with her husband’s condition and rapid decline. She keeps saying over and over, “but the doctor said he was healthy. He’s not supposed to be this way.”

(Originally written: February 1996)

The post “He Could Make Anyone Laugh” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

September 21, 2017

Otto and the Cross-Country Journey to Get Back Their Girls

Otto Hutmacher was born on November 12, 1907 in Prussia to Poldi and Magda Hutmacher. Poldi was a carpenter, and Magda cared for their eight children. Otto only went to the equivalent of grade school and then got a job driving a team of horses for the government. “It was a life of starvation,” he says, so at age 23, he ran off to join his brother, Ernest, in America. Ernest and his wife, Marie, had already immigrated several years before and had written letters to tell the family that there were many jobs. Poldi refused to leave, however, and when Magda tried to plead with him, he beat her. All of his brothers lived in fear of Poldi, so Otto took off by himself to make the journey to America.

Otto Hutmacher was born on November 12, 1907 in Prussia to Poldi and Magda Hutmacher. Poldi was a carpenter, and Magda cared for their eight children. Otto only went to the equivalent of grade school and then got a job driving a team of horses for the government. “It was a life of starvation,” he says, so at age 23, he ran off to join his brother, Ernest, in America. Ernest and his wife, Marie, had already immigrated several years before and had written letters to tell the family that there were many jobs. Poldi refused to leave, however, and when Magda tried to plead with him, he beat her. All of his brothers lived in fear of Poldi, so Otto took off by himself to make the journey to America.

Once here, he found Ernest and Marie in Chicago, where they had already saved enough to buy a house. One by one, the siblings eventually all came, though Poldi and Magda stayed and eventually died in Germany.

Otto was able to immediately find a job at the Continental Can Company, where he worked for eight years. From there, he got a job at a place called Goodmans, which was a tannery. Otto enjoyed this work and stayed at Goodmans for over thirty years.

In his forties, Otto met a woman “from the neighborhood,” which was Southport and Clybourn, at a bowling alley—Otto’s one hobby. Vera Rudaski had been born in Poland and had immigrated here as a young girl. She received little schooling and worked in a variety of factories around the city. Otto finally worked up the courage to ask her out, and they began dating. He was shocked, however, when he stopped by her house one day as a surprise, to find two young girls living there with her.

It was then that Vera reluctantly explained to him that she had gotten pregnant when she was only seventeen and had a baby, Dorothy. The father of the baby abandoned Vera, and she never married. She was forced to then raise Dorothy on her own, as her parents would have nothing to do with her after they discovered she was pregnant out of wedlock. It was a difficult road, Vera told him, and Dorothy was often left alone at home while Vera worked. As she got older, Dorothy began to get into trouble, and Vera found it hard to control her as the years went on.

Vera was heartbroken, then, when Dorothy came home one day and told her she was pregnant. Vera tried to convince Dorothy to give the baby up for adoption, knowing firsthand how difficult it was to raise a baby alone, but Dorothy just laughed and said that that was what mothers were for. She wouldn’t hear of giving up her baby, especially after she unexpectedly gave birth to twin girls, whom she named Flora and Fern. Vera saw no choice but to help Dorothy care for the babies as much as she could, but it was difficult to do while still working.

To make things worse, when the twins were just over a year old, Vera came home from work one day to find the twins crying in their crib and Dorothy gone. Vera found a note from Dorothy which said that she was leaving with a boyfriend for Las Vegas and that she would be back when she had made some money. At that point, Vera didn’t have the heart to put the twins in an orphanage, so she struggled along as best she could. Only periodically did she ever receive a letter from Dorothy, but never with any money enclosed.

After Otto discovered the twins at Vera’s house, he asked her why she hadn’t told him about the girls in the first place. Vera replied that she didn’t think he would be interested in her if he knew she had little kids to take care of. Otto’s response was to ask Vera to marry him. She happily accepted, and he moved into the house with Vera and “their girls.” At the time, Flora and Fauna were six years old, and they took to Otto right away. The girls called Vera and Otto “mom” and “dad,” which suited the two of them fine. Vera was too old to have any more children, so they both enjoyed the girls as if they were their own.

Things went along well enough until, sadly, Dorothy reappeared on the scene out of the blue when the girls were just eleven years old. She had a new husband, Bill, she said, who had convinced her to come back and get the girls to live with them in Vegas. Not only was Dorothy angered by the girls’ shy reception of her, but she was outraged when she heard them calling Vera “mom” instead of “grandma.” Hurriedly she packed them up and took off with them, though Flora and Fern screamed and cried at being removed from Vera and Otto. Otto tried everything in his power to convince Dorothy to change her mind, but to no avail.

The girls stayed with Dorothy and their step-father, Bill, for almost a year, writing home constantly, saying that they were miserable. Their step-father was almost always drunk, they said, and they were afraid of him. Likewise, Dorothy had yet to enroll them in school.

Meanwhile, with every month that passed, Vera sank deeper into depression. Nothing seemed to interest or rouse her. It was at that point that Otto decided to take matters into his own hands and planned a trip across the country to Las Vegas to try to get their girls back. He eventually found Dorothy and the girls living in a filthy apartment, just as the girls had described in their letters. He offered Dorothy and Bill all of his savings in the bank if they would agree to let them have the girls back.

Bill, deeply in debt, agreed, and even Dorothy, though she protested some, didn’t seem to mind that much. Otto, on the other hand, was overjoyed. He drove almost non-stop to get back to Chicago and Vera.

When they arrived, Vera was beside herself with joy, but she was worried about what the girls must have been through with Dorothy and Bill. Likewise, while the girls were happy and relieved to be back home, they were not quite the same as they had once been. They were quieter now and more distrustful.

Things eventually progressed, however, and life went back to normal as much as possible. Otto and Vera had few hobbies and wanted to spend any free time at home with their girls. Flora and Fern eventually went to high school and then got married. Otto and Vera took a couple of trips when they retired, but they mostly stayed at home and enjoyed spending time with Flora and Fern’s children, whom they called their grandchildren, though they were really Vera’s great-grandchildren.

Otto and Vera lived on their own in the same house until 1992, when Vera died peacefully at age 85. Otto was able to care for himself for a while before he started to get very confused and wander. After he was repeatedly found lost in the neighborhood, Fern took him in for a time. When she herself was recently diagnosed with cancer, however, and it became too much for her to care for him as well. With a heavy heart, then, the girls—now getting up there in years themselves, placed Otto in a nursing home.

Otto seemed to be make the transition well at the beginning and enjoyed many of the activities involving music in particular, but he has since begun to decline a great deal. He is now confused and disoriented most of the time and sometimes does not even recognize Flora or Fern when they come to visit. Often he makes nonsensical comments, such as “I won’t die because I live in a mountain.” It makes Flora and Fern very sad to see him this way, but they are happy he is being cared for, as they are not able to have him live with them. They still call him dad.

(Originally written June 1996)

The post Otto and the Cross-Country Journey to Get Back Their Girls appeared first on Michelle Cox.

Otto and he Cross-Country Journey to Get Back Their Girls

Otto Hutmacher was born on November 12, 1907 in Prussia to Poldi and Magda Hutmacher. Poldi was a carpenter, and Magda cared for their eight children. Otto only went to the equivalent of grade school and then got a job driving a team of horses for the government. “It was a life of starvation,” he says, so at age 23, he ran off to join his brother, Ernest, in America. Ernest and his wife, Marie, had already immigrated several years before and had written letters to tell the family that there were many jobs. Poldi refused to leave, however, and when Magda tried to plead with him, he beat her. All of his brothers lived in fear of Poldi, so Otto took off by himself to make the journey to America.

Otto Hutmacher was born on November 12, 1907 in Prussia to Poldi and Magda Hutmacher. Poldi was a carpenter, and Magda cared for their eight children. Otto only went to the equivalent of grade school and then got a job driving a team of horses for the government. “It was a life of starvation,” he says, so at age 23, he ran off to join his brother, Ernest, in America. Ernest and his wife, Marie, had already immigrated several years before and had written letters to tell the family that there were many jobs. Poldi refused to leave, however, and when Magda tried to plead with him, he beat her. All of his brothers lived in fear of Poldi, so Otto took off by himself to make the journey to America.

Once here, he found Ernest and Marie in Chicago, where they had already saved enough to buy a house. One by one, the siblings eventually all came, though Poldi and Magda stayed and eventually died in Germany.

Otto was able to immediately find a job at the Continental Can Company, where he worked for eight years. From there, he got a job at a place called Goodmans, which was a tannery. Otto enjoyed this work and stayed at Goodmans for over thirty years.

In his forties, Otto met a woman “from the neighborhood,” which was Southport and Clybourn, at a bowling alley—Otto’s one hobby. Vera Rudaski had been born in Poland and had immigrated here as a young girl. She received little schooling and worked in a variety of factories around the city. Otto finally worked up the courage to ask her out, and they began dating. He was shocked, however, when he stopped by her house one day as a surprise, to find two young girls living there with her.

It was then that Vera reluctantly explained to him that she had gotten pregnant when she was only seventeen and had a baby, Dorothy. The father of the baby abandoned Vera, and she never married. She was forced to then raise Dorothy on her own, as her parents would have nothing to do with her after they discovered she was pregnant out of wedlock. It was a difficult road, Vera told him, and Dorothy was often left alone at home while Vera worked. As she got older, Dorothy began to get into trouble, and Vera found it hard to control her as the years went on.

Vera was heartbroken, then, when Dorothy came home one day and told her she was pregnant. Vera tried to convince Dorothy to give the baby up for adoption, knowing firsthand how difficult it was to raise a baby alone, but Dorothy just laughed and said that that was what mothers were for. She wouldn’t hear of giving up her baby, especially after she unexpectedly gave birth to twin girls, whom she named Flora and Fern. Vera saw no choice but to help Dorothy care for the babies as much as she could, but it was difficult to do while still working.

To make things worse, when the twins were just over a year old, Vera came home from work one day to find the twins crying in their crib and Dorothy gone. Vera found a note from Dorothy which said that she was leaving with a boyfriend for Las Vegas and that she would be back when she had made some money. At that point, Vera didn’t have the heart to put the twins in an orphanage, so she struggled along as best she could. Only periodically did she ever receive a letter from Dorothy, but never with any money enclosed.

After Otto discovered the twins at Vera’s house, he asked her why she hadn’t told him about the girls in the first place. Vera replied that she didn’t think he would be interested in her if he knew she had little kids to take care of. Otto’s response was to ask Vera to marry him. She happily accepted, and he moved into the house with Vera and “their girls.” At the time, Flora and Fauna were six years old, and they took to Otto right away. The girls called Vera and Otto “mom” and “dad,” which suited the two of them fine. Vera was too old to have any more children, so they both enjoyed the girls as if they were their own.

Things went along well enough until, sadly, Dorothy reappeared on the scene out of the blue when the girls were just eleven years old. She had a new husband, Bill, she said, who had convinced her to come back and get the girls to live with them in Vegas. Not only was Dorothy angered by the girls’ shy reception of her, but she was outraged when she heard them calling Vera “mom” instead of “grandma.” Hurriedly she packed them up and took off with them, though Flora and Fern screamed and cried at being removed from Vera and Otto. Otto tried everything in his power to convince Dorothy to change her mind, but to no avail.

The girls stayed with Dorothy and their step-father, Bill, for almost a year, writing home constantly, saying that they were miserable. Their step-father was almost always drunk, they said, and they were afraid of him. Likewise, Dorothy had yet to enroll them in school.

Meanwhile, with every month that passed, Vera sank deeper into depression. Nothing seemed to interest or rouse her. It was at that point that Otto decided to take matters into his own hands and planned a trip across the country to Las Vegas to try to get their girls back. He eventually found Dorothy and the girls living in a filthy apartment, just as the girls had described in their letters. He offered Dorothy and Bill all of his savings in the bank if they would agree to let them have the girls back.

Bill, deeply in debt, agreed, and even Dorothy, though she protested some, didn’t seem to mind that much. Otto, on the other hand, was overjoyed. He drove almost non-stop to get back to Chicago and Vera.

When they arrived, Vera was beside herself with joy, but she was worried about what the girls must have been through with Dorothy and Bill. Likewise, while the girls were happy and relieved to be back home, they were not quite the same as they had once been. They were quieter now and more distrustful.

Things eventually progressed, however, and life went back to normal as much as possible. Otto and Vera had few hobbies and wanted to spend any free time at home with their girls. Flora and Fern eventually went to high school and then got married. Otto and Vera took a couple of trips when they retired, but they mostly stayed at home and enjoyed spending time with Flora and Fern’s children, whom they called their grandchildren, though they were really Vera’s great-grandchildren.

Otto and Vera lived on their own in the same house until 1992, when Vera died peacefully at age 85. Otto was able to care for himself for a while before he started to get very confused and wander. After he was repeatedly found lost in the neighborhood, Fern took him in for a time. When she herself was recently diagnosed with cancer, however, and it became too much for her to care for him as well. With a heavy heart, then, the girls—now getting up there in years themselves, placed Otto in a nursing home.

Otto seemed to be make the transition well at the beginning and enjoyed many of the activities involving music in particular, but he has since begun to decline a great deal. He is now confused and disoriented most of the time and sometimes does not even recognize Flora or Fern when they come to visit. Often he makes nonsensical comments, such as “I won’t die because I live in a mountain.” It makes Flora and Fern very sad to see him this way, but they are happy he is being cared for, as they are not able to have him live with them. They still call him dad.

(Originally written June 1996)

The post Otto and he Cross-Country Journey to Get Back Their Girls appeared first on Michelle Cox.

September 14, 2017

From Mexican Theater Performer to Chicago Nanny

Eduardo Hernandez was born on November 7, 1922 in Mexico to Juan and Rosita Hernandez. Eduardo says that he was the youngest of seven children and that his mother died giving birth to him. His father worked as some type of laborer and, according to Eduardo, was a drunk who beat him and his siblings for even the smallest infraction. He was particularly hard on Eduardo, whom he constantly blamed for Rosita’s death.

Eduardo Hernandez was born on November 7, 1922 in Mexico to Juan and Rosita Hernandez. Eduardo says that he was the youngest of seven children and that his mother died giving birth to him. His father worked as some type of laborer and, according to Eduardo, was a drunk who beat him and his siblings for even the smallest infraction. He was particularly hard on Eduardo, whom he constantly blamed for Rosita’s death.

Eduardo did not go to school and spent most of his time roaming the streets and looking for work, though jobs were almost impossible to fine. His family was “very, very poor,” Eduardo says, and adds that “Mexico was terrible then. You can’t imagine.”

Eventually, when Eduardo was thirteen or fourteen, he could no longer stand his father’s beatings, so he ran off with a theater group, where he spent many years dancing, singing and performing with them. He lived a nomadic life, never having any money, but at least with the theater group, he had a place to stay, usually in tents, and a little bit of food. He repeatedly tried to find a more stable job, but there were very few of those. Finally, when he was in his early forties, he decided to try his luck in America.

Eduardo made it to San Antonio, where he found work in a kitchen. He didn’t like the work, but he did not have a lot of choices, he says, not only because he could he not speak English, but because he had never been to school and was ignorant of the most basic things. He worked in San Antonio for a long time and then made his way north to Chicago, where he again found work in various restaurants. On his days off, he would walk up and down State Street, marveling at the buildings and the people, and enjoyed taking everything in. One day he saw a “help wanted” sign in the window of a small hotel, so he went in and applied. The owner was a man named Robert Neilson, who would go on to become Eduardo’s lifelong friend.

After only three months of working in the kitchen of Robert’s hotel, Robert’s wife, Cathy, gave birth to a little girl, Amanda. The nanny that they had arranged to babysit her quit at the last minute, so the Neilsons asked Eduardo to fill in until they could hire someone new. Time passed, however, and soon the Neilsons and Amanda had grown attached to Eduardo, so they had him move in with them to their home in Park Ridge to become Amanda’s full-time nanny. Eduardo did this for the next ten years until Amanda didn’t really need a nanny anymore.

Eduardo moved out, then, and found an apartment over a restaurant in the city, where he had found a job, again working in the kitchens. He never got married, he says, because he didn’t have enough money or a good enough job. For many years, he continued to visit the Neilsons, though, whom he says were like a family to him, and sometimes did odd jobs for Robert while there. Meanwhile, Eduardo met another Mexican man at the restaurant by the name of Enrique Garcia. Enrique and Eduardo became good friends, and before long, Enrique offered to have Eduardo move in with him and his wife, Emily. Eduardo accepted and lived with the Garcia’s for about five years until he had a sort of stroke and was hospitalized.

From the hospital, he was discharged to a nursing home, but was told, as was Enrique and Emily, that it would be a temporary arrangement until he was well enough to go home. As the weeks progressed, however, Eduardo began to suspect that he was expected to permanently stay at the nursing home and, agitated, tried to walk out of the facility in an attempt to get back to Enrique’s apartment, telling the staff that Enrique was his son. When the staff tried to stop him, they claim he became violent and thus sent him to the psychiatric ward of a nearby hospital.

The hospital staff were eventually able to track down Robert Neilson, who then got involved in Eduardo’s plan of care. He helped the discharge staff to arrange for him to be released to a different nursing home. Robert says that he has a hard time believing that Eduardo became violent and is trying to help him to make a better transition to this current facility. He says that Eduardo “is a good man at heart; he’s just a little crazy now.” He says he has spoken to Enrique, who also says Eduardo is a good man, but that it was becoming too much for him and his wife to continue caring for him. They felt guilty but relieved when he was admitted to a nursing home after his stroke. Robert has now listed himself as Eduardo’s official contact and says he is committed to visiting him and making sure Eduardo is adjusting.

Eduardo is making a relatively smooth transition. He does not exhibit any problem behaviors, but he seems depressed a lot. He speaks little English, so it is difficult for him to interact with the other residents. He spends most of his time in the day rooms watching TV or talking to any staff members who speak Spanish. They have asked him, from time to time, to sing some songs from his performing days, but Eduardo waves them away, saying that all that is past now. “I don’t remember,” he says.

The only time he perks up is when Robert comes to visit. Recently, Robert surprised Eduardo by also bringing Amanda and her two children to the home to visit with him. Eduardo was delighted and spent the afternoon showing them around and introducing Amanda to the staff and calling her “his girl.”

(Originally written: March 1996)

The post From Mexican Theater Performer to Chicago Nanny appeared first on Michelle Cox.

September 7, 2017

“She Lost an Eye as a Baby”

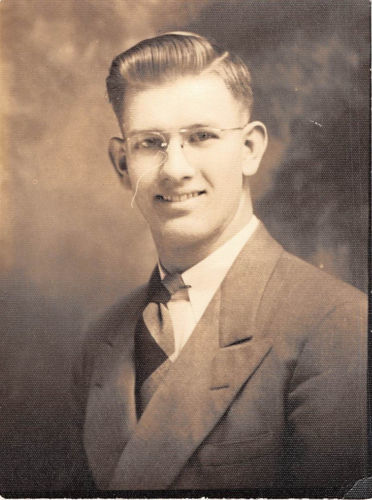

Celeste Salvail (right) with her sister, Gina

Celeste Salvail was born on February 29, 1920 in Chicago to Vincenzo Salvail and Angela Potenza. Vincenzo and Angela were Italian immigrants who had met and married while still in Italy. In fact, they had already had two children, Apollonia and Christina, when they set sail for America, but Christina, who was just a baby, died on the voyage over. Vincenzo found a job in Chicago working for the railroads. It was his job to raise and lower the gates and to blow the whistle when a train was approaching. Angela was a housewife who cared for their nine children: Apollonia, Tito, Gina, Ines, Celeste, Manny, Silvio, Bianca and Rocco.

Unfortunately, when Celeste was still a baby, an accident occurred in which Celeste lost an eye. The family was at a 4th of July celebration, having a picnic outdoors. Some kids nearby were shooting off fireworks, one of which went out of control and exploded near baby Celeste’s face. As a result, she lost her left eye. She wore a patch over it until she was twenty, when she had an operation and was fitted with a glass eye.

Despite only having one eye, Celeste enjoyed school, though she was often teased. She also loved playing sports, especially with her brothers and sisters in the streets in their neighborhood. She was forced to quit school, however, after graduating from eighth grade, as the family needed money. Celeste found a job fairly quickly and says that she had so many jobs in her lifetime that she can’t remember them all. One of her favorites, though, was working on the assembly line at the Nabisco Cookie Company. Celeste worked there for sixteen years and was responsible for packing the cookies. She thought it was a very interesting job, and she really enjoyed it.

Celeste never married. She had a boyfriend, Alfred, for many years and says that she was in love with him. He asked her to marry him, but she turned him down in the end and broke off their relationship. “He was an alcoholic,” she says. Though she loved him, she was afraid of what a marriage to him might mean and that she would end up supporting him and any children they might have. After that, she “tried to get a rich one,” she jokes, “but they were hard to come by!”

Celeste remained single and devoted herself to her nieces and nephews. Her parents died relatively young: Vincenzo of double pneumonia and Angela of a heart attack. For a long time, Celeste lived with her sister, Ines. She loved to garden and spend time with her family playing games. Later in life, she lamented the “good ole days,” when she would take her nieces and nephews on a picnic virtually every weekend of the summer.

In the mid 1980’s, Ines unfortunately passed away, so Celeste got her own place, where she has lived alone until recently. All of her siblings, except Bianca, have passed away as well, so it has fallen on Bianca and her daughter, Judy, to be checking in on Celeste the most. In December of 1993, Celeste fell and broke her hip and was hospitalized for over a month, where she was a very willing participant in physical therapy and social activities. It was decided, then, between the discharge staff at the hospital, Bianca and Celeste that she would be admitted to a nursing home, at least to continue her physical therapy.

After being here for several weeks, however, Celeste is accepting that this is now her permanent home and is working hard at making a smooth transition. She has a very positive attitude and says “you have to make the best of it”—a mantra she seems to have adopted early in life. She has made several friends already and enjoys, in particular, exercise class, arts and crafts, bingo and smoking cigarettes in the smoking room. She also says she would be interested in helping with the gardens in the spring.

Bianca and Judy, as well as many of her other nieces and nephews, come to visit her often and have been extremely loving and supportive of their aunt/great aunt. “There’s no use crying over spilled milk,” Celeste says, “you just have to keep trying.”

(Originally written January 1994)

The post “She Lost an Eye as a Baby” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

August 31, 2017

A Postal Theft, Two Vaudeville Actors, an Unsolved Murder, a Little Girl, and The Best Thing That Ever Happened!

Andrew Pokorny was born on October 20, 1912 in Chicago to Branislav Pokorny and Maria Tesar, both of whom were immigrants from Slovakia. Andrew is not sure whether his parents met and married in Slovakia or if they met here, but he remembers his father working as a coppersmith. His mother was a housewife and cared for their three children: Andrew, Danka and Martina.

Andrew Pokorny was born on October 20, 1912 in Chicago to Branislav Pokorny and Maria Tesar, both of whom were immigrants from Slovakia. Andrew is not sure whether his parents met and married in Slovakia or if they met here, but he remembers his father working as a coppersmith. His mother was a housewife and cared for their three children: Andrew, Danka and Martina.

The Pokornys lived in various apartments on Chicago’s north side and never did own their own home. Andrew went to school until the seventh grade and then began working. He jumped from job to job, mostly in factories or sometimes as a delivery boy. Though he had quit school early, he was clever, and he eventually found himself working at the post office in the mail room. This was a job Andrew really enjoyed, and he was proud to have it. His goal was to eventually be promoted to mail carrier, so he worked hard and tried to learn as much as he could.

On his days off, Andrew was fond of riding his bicycle around the city and in some of the city’s bigger parks, like Humboldt, Garfield and Douglas. One day, as he was riding through Garfield Park, he came upon a young woman sitting on a bench knitting. He stopped to ask her name, and they began talking. From there they began dating, and a year later, Andrew and Elizabeth Newman were married. Andrew had been raised Lutheran, and Elizabeth was Catholic, so Andrew converted to Catholicism for the wedding. He took it seriously, though, and remained devoutly Catholic his whole life. Elizabeth worked at Marshall Fields behind the cosmetics counter, with the understanding that when she became pregnant, she would quit to stay home and be a housewife. Sadly for both of them, however, they were never able to have children.

When they eventually realized that they were probably not going to have a family, Andrew and Elizabeth tried instead to get involved in their parish and joined various bowling leagues over the years. They also loved going to the movies and baseball games. Neither of them, it seemed, liked the idea of traveling.

Things stayed this way for about ten years and may have continued as such had a crisis not occurred at Andrew’s place of work, which was still the post office. Unbeknownst to Andrew, his best friend at work, a man by the name of John Davis, had been stealing mail for years. He was finally caught and arrested, and Andrew, by association, was suspected as well and was fired pending an investigation. John Davis ended up going to jail, while Andrew was cleared of any wrong-doing. He permanently lost his job, though, and thus his hopes of a career in the postal service.

Andrew began drinking heavily to deal with his grief and could not find another job. After a couple of years of this, Elizabeth announced that she was divorcing him. She had run into an old boyfriend, she said, and was leaving Andrew for him. Andrew begged her not to go, but she eventually moved out of the apartment, remarried, and went to live with her new husband in Wisconsin.

With no job and no money, Andrew was forced to leave the apartment, too, and moved into a cheap motel. His sister, Danka, had died of cancer several years before, and he had been estranged from Martina from a young age. “We never got along,” Andrew says, and he eventually lost touch with her. Even now, he has no idea where she is living or if she was even alive. Thus, at the time of his divorce, he was very alone and really had nobody. He had lost his best friend, his job, his wife and his immediate family. He got odd jobs here and there, enough to buy cigarettes and alcohol with, but not much more.

He was eventually befriended by his next-door neighbors at the motel, a couple called Leo and Nellie, who claimed they had once been vaudeville entertainers and that they still made most of their money by acting or performing in various travelling shows. Andrew had never met anyone like them and was amazed by their talents. He loved it when they showed him magic tricks or did their juggling routine for him, and he especially took a shine to their little daughter, Josephine, or “Josie.”

Over the next several years, Andrew got to know his neighbors well and often even babysat for Josie when Leo and Nellie were travelling. One summer, however, Leo and Nellie did not come home, and Andrew later learned that they had been both been killed, apparently murdered. Leo and Nellie’s deaths were never solved, but Andrew thinks that it might have had something to do with gambling. Andrew took Josie in, though she was already fourteen at the time, and found it difficult to control the grieving, rebellious girl.

When she was just sixteen, Josie got pregnant and moved into her boyfriend’s apartment because Andrew was drinking so heavily. She had the baby, a little boy she named Leo, but she became quickly disillusioned with her relationship with her boyfriend. Eventually she went back to Andrew’s, with the baby on her hip, as Andrew now tells the story, and demanded that he choose between “the bottle” and them.

Andrew, astonished that Josie had returned, says that he gave up drinking and smoking from that day forward. He sobered up, got a job as a punch press operator, and moved into a decent apartment. Josie and little Leo stayed with him for several years until Josie met someone new and got married. They moved into their own apartment nearby on Pulaski, and Josie had two more children. She and Andrew stayed very close, however. Andrew says she is like a daughter to him, and, in turn, Josie refers to him as “Pops.”

Andrew says he is so very thankful that he made the choice he did, and that Josie didn’t give up on him. Andrew was able to live on his own until 1992, when Josie found him unconscious on the floor of his apartment. She called an ambulance, and he was diagnosed as having had a stroke. He was then admitted to a neighborhood nursing home near where Josie and her family still live.

Andrew has made a brilliant transition to the home and often says, “This is the best thing that ever happened to me.” He fully participates in every activity the home provides, and Josie and her children often come and volunteer, of which Andrew is very proud. His favorite duty is calling the bingo numbers. Besides helping with activities and visiting residents who are bed-bound, each day he sits near the entrance of the home and greets people as they come in. He is so helpful to visitors coming in, as well as to current residents, that the staff had a badge made for him, designating him as a top volunteer and ambassador to the home. He is extremely proud of his badge and wears it everywhere. He is a wonderful example of someone who turned his life around, albeit a bit late, for the benefit of not only himself, but of many. He is very much an inspiration to all who are lucky enough to know him.

(Originally written: May 1995)

The post A Postal Theft, Two Vaudeville Actors, an Unsolved Murder, a Little Girl, and The Best Thing That Ever Happened! appeared first on Michelle Cox.