Michelle Cox's Blog, page 29

January 4, 2018

Around the World and Back Again: The Nearly Unbelievable Life and Times of Alek Kozel – Part III

(Our exciting story concludes . . . ! Make sure to read Part I and Part II first!)

(Our exciting story concludes . . . ! Make sure to read Part I and Part II first!)

Part III: In which our hero makes his way to America, helped by a long string of strangers along the way; finally finds work as a master tailor at Marshall Fields; and then meets Anna, the love of his life . . .

Alek Kozel’s first step in attempting to achieve his new goal was to go to the American embassy in Prague. He showed them his crumpled, tattered American birth certificate, but they informed him, after careful inspection of it, that it was too torn and illegible to be used and that he would have to send away for a new copy.

Not to be deterred, Alek wrote a letter to St. Andrew’s, the Catholic church in Christopher, Illinois, where he had been born, to obtain a new copy of his birth certificate, a task he accomplished with the help of an acquaintance in Prague, one Frank Svoboda, who knew how to read and write in English.

Alek waited months for a reply, which finally came in the form of a letter from one Donald Novotny. Donald Novotny was apparently a very prominent Czech living in Christopher, Illinois who had been given Alek’s letter by the pastor of St. Andrew’s. In his letter, Mr. Novotny explained to Alek that the church had burned down several years before and that all the church records had been destroyed. Mr. Novotny, however, vowed to help Alek to obtain a new birth certificate and had indeed already started the process, but informed Alek that it might take a very long time.

As promised, though, after eight months of waiting, the new birth certificate finally arrived along with a letter from Donald Novotny explaining that he had had to track down Alek’s godmother, whom he found living in Indiana, to sign a document verifying his birth. Once found, however, she proved to be too old and crippled to sign, so her son had to then be located to sign for her. Also, Mr. Novotny explained, he had applied to the United States Government to become Alek’s sponsor and had been approved, so all was in order for him to finally come.

Overjoyed, Alek then hurried to the embassy in Prague to obtain his visa to leave and began his preparations for his new life in America. Before he left, he went to say goodbye to his old employer, Mr. Navratil, and to the old woman he had lived with, Mrs. Dubala. He had a little farewell gathering at the pub he used to go to and there said goodbye to Dusan, Evzen, and his friend, the policeman, among others. Sadly, Mr. Skalicky had already passed away. It was at his farewell party that two sisters living in that same town asked him if he would carry some packages and letters to their sister, one Tamara Fiala, who was living in Chicago. Alek agreed, and the two sisters ran home to get the packages and a little card with their sister’s address written on it.

Alek also went and said a last goodbye to all of the people working in the food ticket office, many of whom he had gotten to know so well over the years. They then told him that they had known all along that his employment notes from the farms had been falsified, but that they had given him the tickets anyway. They liked him very much, they told him. He was a smart man and a good talker, and though they would miss him, they wished him well.

Alek was informed that he could have immediate passage on a cattle ship, but he wanted to wait for a regular passenger ship, even though there wasn’t one leaving for another three weeks from Le Havre, France. Alek decided to spend his last weeks hanging about Prague until closer to the date of departure, sleeping outside and getting what food he could.

It was during this short, three-week period that Alek happened to meet a young woman, Bessie Beranek, who was working as a waitress in a café. She had been married to a German who had died in the war, and Alek fell madly in love with her, the first woman he had ever fallen for. He spontaneously asked her to marry him and come with him to America. She said she would, but she had no money and Alek had only enough for his own passage. He promised to send for her once he got settled and had earned some money, and so they sadly said goodbye when it was time for him to take the train to Paris and then on to Le Havre to board the ship. For a long time after, Alek continued to write to her from America and to send her gifts—things she wouldn’t be able to readily get in Europe at the time, he said—such as a bathing suit or a beach towel. Eventually, however, her letters stopped coming, and Alek finally gave up hope of them ever being together.

Once on board the ship that was to carry him away from war-torn Europe and toward his new life in America, he met a Yugoslavian man who could speak English very well and who was bound for Canada. He took an instant liking to Alek and helped him in many ways. For example, when the ship finally docked, there was an announcement for all Americans to disembark first. The Yugoslavian interpreted the message for Alek and prodded him to go, since he had American papers. Alek followed the man’s directions, but the ship officials tried to stop him because he couldn’t speak English. The Yugoslavian man stuck up for him, though, and they eventually let Alek through. Not knowing where to go first, Alek sat and waited for the Yugoslavian man to disembark, which took a long time as he had a big crate of gifts that the officials insisted on rifling through. Surprised to still see Alek sitting there with his little case once he finally disembarked as well, the man bought him some dinner and then took him to the train station and bought him a ticket for Chicago. Alek asked for his address where he could send money to repay him, but the man refused.

Once on the train bound for Chicago, Alek was again fortunate in meeting a friendly stranger who helped him. The man only spoke English, but he bought Alek some food and a pillow and tried to find someone on the train who could speak Bohemian. Finding no one, however, the man tried his best to communicate with Alek himself. Once they arrived in Chicago, Alek showed him the address of Tamara Fiala. The man seemed to understand and put him in a cab, gave the address to the cab driver and paid Alek’s fare for him.

When the cab finally pulled up to the building indicated on the card, the cab driver helped Alek find the right apartment, banged on the door and yelled, “Hey! You got someone from Europe here!” The woman who opened the door was not Tamara Fiala, however, but instead was Mrs. Fiala’s daughter and her husband. They took Alek in, however, and gave him a much-needed bath and one of the husband’s t-shirts—several sizes too big—to wear for the night. The next day, they took him to Berwyn, where Mrs. Fiala was living, and Alek was able to finally deliver all the little packages from her sisters that he had been carefully carrying this whole journey.

Mrs. Fiala promptly took Alek in, overjoyed to see someone from her old town, and collected money from the Czech community in Berwyn to pay for his train ticket to Christopher, Illinois, where Donald Novotny was supposedly waiting to collect him. Once procured, Mrs. Fiala pinned the ticket to his lapel, explained his situation to the train conductor and asked him for his help in getting Alek to his destination. The conductor willingly agreed and and thus accordingly told Alek when to get off.

As promised, when Alek descended from the train, there was his sponsor, Donald Novotny, waiting to take him to Christopher, Illinois, fourteen miles away, the very place he had been born back in 1913. Though none of it looked familiar, Alek admits that he cried, so overcome with emotion was he. Mr. Novotny was very kind to him and took him in to live with him and his wife. They put him in their guest bedroom and gave him a bath, and then Donald promptly took him to get a hair cut and out to dinner to a restaurant, where Alek ordered a strange delicacy—spaghetti and meatballs.

Donald introduced him to the Czech community in Christopher, many of whom either remembered his parents or recognized the Kozel name. They took turns having him to dinner, washing his clothes for him and attempting to teach him some English. Alek was comfortable in his new surroundings, but after a while he began to realize that he had no prospects. Likewise, it seemed that things were getting a little tense with the Novotny’s. Indeed, one day, Donald’s wife, who worked at a local tavern, exploded in fury when she discovered that the money she was giving Donald to supposedly give to Alek was actually going to Donald’s mistress.

Alek tried to steer clear of the Novotny’s domestic troubles, but it was difficult since he was living in their house. As it turned out, a Yugoslavian woman living in Chicago happened to show up just as all the trouble was brewing, to collect her husband’s pension check. Donald Novotny was somehow involved in the pensions of the mine workers in Christopher. This woman’s husband had been badly burned in the mine, and she did not trust the mail system; therefore, she came and collected his checks in person. Donald introduced her to Alek, and when she had heard his whole story, she invited him to come and stay with another Yugoslavian family she knew of in Chicago. As his official sponsor, Donald was hesitant to let Alek go to such a big city as Chicago to live and work, but after much thought, especially considering the marital troubles he was now having, it seemed to make the most sense.

So, back Alek went to Chicago to stay with the Yugoslavian family. The family had two sons, the younger of whom, Ivan, especially befriended Alek. The two of them would sit outdoors in the evening, and Ivan would try to teach Alek bits of English. Alek was surprised and delighted to learn that Ivan was interested in becoming a tailor, but he attempted to talk him out of pursuing such a career, telling him that the pay was no good. Ivan decided to listen to his new friend and eventually chose a different path, but he did take Alek to Marshall Fields to inquire about a job for Alek in the tailoring department.

As it turned out, the foreman of the tailoring department at Fields at the was a Bohemian man as well, and he agreed to give Alek a try. Within a couple of months, Alek was recognized as the best tailor in the department— perhaps the best tailor they had ever had!

Alek had been hired at fifty-five dollars a week, but when he found that everyone else was making sixty-five a week, he demanded a raise. He didn’t care if he was fired, as he didn’t have any dependents and he knew he could get a job doing just about anything. The foreman agreed, though, and Alek continued working at Marshall Fields for the next twenty-seven years. For Alek, this was indeed the pinnacle of his career, the position it seemed he had been training for and working at for years and years while still in Europe. He was immensely proud of his position at Marshall Fields, and accordingly, he thought it essential that he dress the part. Each day, then, he would come to work dressed in a fine suit, tie and hat just as any business man would go to work in. Once at Fields, he would change into his work clothes, but then would change back into his suit for his trip home.

Alek only stayed with the Yugoslavian family for a short time. After only three weeks, the mother of the family felt it to be a strain to not only feed and care for her own two sons but Alek as well, so she asked her husband to find another place for Alek to live. The husband appealed to a Slovak friend of his who agreed to rent him a room for a year. After that first year, Alek then rented a room from the man’s mother, who lived in Cicero, which meant Alek had to commute to Marshall Fields from Cicero each day.

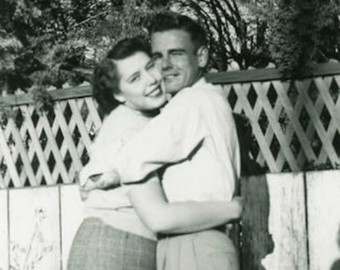

Alek didn’t mind living in Cicero, however, as there was a huge Czech community there, and he felt at home. Now that he had a place to live and a great job, he decided to try to socialize more and meet some new friends and so joined many Czech clubs and fraternal organizations. It was at one such club that he met a woman named Anna Hajek, the same given name as his mother. The club was having a dance once night, and after catching his eye from afar, Anna approached him and asked him to dance. Alek was taken aback by her forwardness, but he accepted and then spent the rest of the night talking with her. He escorted her home, chivalrously paying her fare on the El for her, where she lived alone with her mother, she told him. Alek and Anna enjoyed talking so much that Alek asked her out on a date for the following Saturday, and she accepted. There was an immediate spark between them, and they began to see each other more and more. Alek was mesmerized by Anna, and he quickly fell in love with her.

He was shocked and outraged, then, when one day he showed up at Anna’s house in Cicero, only to find a young man in the house with her. His old temper flaring, he demanded to know who the man was. Anna quickly explained that the young man was actually her son, William! She then explained that she had gotten pregnant with William when she was only fifteen. She refused to talk about the circumstances, merely saying that she never saw the father again, and that she and her mother had raised William on their own. A few years after William’s birth, Anna explained that she had met another man, one Mike Kennedy, whom she fell in love with and assumed she would marry. When she got pregnant, however, Mike deserted her. After she had the baby, whom she named Robert, Mike unexpectedly showed up again, took Robert and gave him to his mother to care for.

Anna grieved for her baby, but she felt she had few options, especially as she needed to continue working to support her aging mother and little William. Over the years, she told Alek, friends had told her that she should fight to get Robert back, but though she missed him, she wasn’t sure her mother could care for another child anyway. Her mother had several health problems as it was, and from a young age, William was actually more a caregiver to her than the other way around. Sadly, Anna explained that though Robert was now fifteen, she barely knew him and only usually saw him at the holidays, as Mike made it very difficult for her to be involved in his life in any way. William, meanwhile, at age nineteen, was off at college now and was merely home at the moment for a visit. She had planned on telling Alek everything, she told him, just that she had been waiting for the right moment, afraid that if she revealed too much, she would scare him away.

Alek, it seems, was a little thrown off by all of this and took a couple of weeks away from Anna to absorb it all. Initially, he felt deceived by her, but in the end, he realized that he was acting stupidly. After all, he hadn’t shared all of the details of his life yet, either, he reasoned, including his “affair” with Bessie Beranek. He loved, Anna, he decided, and didn’t want to lose her. Thus, instead of breaking it off with her, he proposed to her, and she accepted. Alek was thirty-eight years old at the time, though he felt he had already lived many lives. Anna, too, at age thirty-four, had been through much. They had both been in love before, but this was the first marriage for both of them, and they very much felt that they were beginning a new chapter and starting yet another new life, this time together.

They married in 1951, and one of Anna’s friends had a little reception for them at her home. Alek says it was a small affair, but they had a nice dinner, beer, whiskey and a cake. They sold the house in Cicero and rented an apartment in Berwyn, another big Czech community, and naturally brought Anna’s mother to live with them. After only a year of working hard, they saved one thousand dollars, enough to put down to buy a dry-cleaners on Euclid in Berwyn and moved into the apartment above it. Anna ran the dry-cleaning business while Alek still worked at Marshall Field all day.

Alek and Anna never had any children, but after only a year or so of marriage, a child came to them in a different way. On their second Christmas together, Anna’s son, William, showed up unexpectedly at their apartment with his two-and-a-half year old daughter, Evelyn. Right at about the same time that Alek had entered the scene, William had married a young woman named Ruth Herbst, whom he had met at college. Neither Anna nor her mother had a good feeling about Ruth and tried to warn William, but he had married her anyway, saying that a baby was on the way, and he didn’t want to repeat the mistakes made by his own father and his brother’s father, Mike Kennedy, by having the baby born out of wedlock.

Shortly after Evelyn was born, however, Ruth demanded that they move to California to be near her family, so William reluctantly agreed. He got a job there and continued trying to get his college degree at night. William explained to his mother and Alek that he soon discovered that Ruth was leaving the baby alone during the day while she went out. He suspected her of having an affair, so he hired a detective, who soon produced the evidence confirming William’s suspicions. William divorced her and hired a babysitter to watch little Evelyn, who was now a toddler. William then discovered that the babysitter and her husband were severely punishing Evelyn for wetting her pants, which was the last straw for William. In desperation, he packed Evelyn up and went back to Chicago, arriving the day after Christmas to appeal to his mother and Alek for help.

He was desperate, he explained, and begged Anna and Alek to take Evelyn in while he finished his degree. Anna was hesitant to do so, but Alek was captivated by Evelyn and convinced Anna to care for her. Thus, Alek and Anna began a little family together, both of them adoring Evelyn. They gave up the dry-cleaning shop after only a couple of years because it failed to make any money, so they moved to an apartment on Springfield Street in Berwyn, where they stayed for nine years before they moved again to Avery Avenue.

After only about a year of Evelyn being with them, William remarried in California, but neither he nor his new wife showed any interest in coming to get Evelyn. Thus, Evelyn remained and grew up with Anna and Alek, whom she called her grandma and grandpa, for the next twelve years. Alek continued working at Marshall Fields, and Anna, for the first time in her life, stayed at home as a housewife to care for Evelyn as well as her mother, who unfortunately died not long after.

When Evelyn turned fourteen, William again appeared at Christmas time to visit, the first time he had done so in several years. Evelyn was enraptured with her father, and though she loved Anna and Alek, she begged him to take her to California so that she could meet her step-mother and her three half-brothers. William reluctantly agreed, much to the utter heart-break of Anna and Alek. They only wanted the best for Evelyn, but they were utterly crushed when she left and missed her terribly. Nothing was the same after she left, Alek explains, though she wrote to them faithfully.

But Evelyn was not their only source of sorrow over the years. One other reason that Anna quit working when Evelyn came to live with them is because she had been diagnosed with cancer in 1955. She received extensive treatments, and the cancer went into remission, though it left her extremely ill at times. Even after Evelyn left, Anna did not go back to work and remained at home. Alek began planning their retirement very early on and over the years had saved enough to buy a little parcel of land and a trailer in New Concord, Kentucky. By 1976, he was ready to retire, but his foreman at Marshall Fields asked him to stay on for one more year. Alek discussed this proposal with Anna, but she told him that if she had to wait another whole year, she wouldn’t make the move at all. Thus, Alek gave up his position of master tailor at Marshall Field, and they moved to New Concord.

They had several years there together and enjoyed puttering about with different hobbies and made new friends. They were truly happy, Alek says, despite everything that had happened to them over the years. Only once did Alek ever hear from the family he fled from in Czechoslovakia. In 1978, he received a letter from a younger sister who had been born after he had run away. This sister informed him that their father had died years ago and implored Alek to return home to visit their mother one last time, as she was old and blind and sick and was asking for him. Anna told him that he should go, but Alek instead threw the letter into the fire and never saw or heard from any of them again.

Unfortunately, in 1984, Anna’s cancer came back with a vengeance. She again took up the battle to fight it, but on April 13, 1989, she finally died. Alek was devastated by Anna’s death and for many, many months had trouble sleeping. He would awake in the middle of the night and, unable to get back to sleep, would get up and work on the trailer, fixing things inside and out. He ran himself ragged to escape his sadness, and on December 12, 1993, he suffered a stroke and was taken to a hospital in Murray, Kentucky and then transferred to Lourdes Hospital in Paducah. From there he was transferred for some reason to a rehab center in Marion, Illinois, very near the Kentucky boarder and, in an ironic twist of fate, not far from Christopher, Illinois, where he had been born, completing a nearly eighty-year journey around the world and back.

At the nursing home in Marion, Alek made little progress toward his rehabilitation and remained in a deep depression. The social service staff were eventually able to locate and reach out to his step-sons: William, still living in California, and Robert, still living in Chicago. The two half-brothers then eventually came together and found a Bohemian nursing home in Chicago where they thought Alek might be happier. They arranged for the transfer to the nursing home and were both on site when he arrived at his new home. He was grateful and happy to see them both, but he lives in hope that Evelyn might some day visit, though she is living with her husband and children in California.

So far, Alek seems to be making a fairly good transition to the new facility. He enjoys being able to talk to people in Bohemian, though the stroke has affected his ability to speak clearly. This frustrates and angers him, as he has a lot to say and wishes to tell anyone who will listen his long, long story. Most people cannot understand him, though, as he slurs his words a lot and drools constantly. He participates in some activities but prefers to talk to the staff. He is very pleasant and courteous, though he always seems to have a bit of a chip on his shoulder. He sees himself as a victim of life’s misfortunes in many ways, despite having thwarted life’s curve balls so many times. He seems desperate to tell his epic adventures and loves to tell about his work at Marshal Fields in particular, which seems, in his mind, to be his crowning achievement, though the love of his life, he says, was, and always will be, Anna.

The end.

(Originally written April 1994)

The post Around the World and Back Again: The Nearly Unbelievable Life and Times of Alek Kozel – Part III appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 28, 2017

Around the World and Back Again: The Nearly Unbelievable Life and Times of Alek Kozel – Part II

(Our exciting story continues…to read Part I first, click here.)

(Our exciting story continues…to read Part I first, click here.)

Part II: In which our hero finally finds work as a tailor, nearly dies of a mysterious illness, has a run-in with the German SS and then the Russians, and hurriedly decides to flee…

After being fired by Mr. Chvatal, Alek went back to Mr. Kratochvil’s boarding house, where he had run up a pretty large debt, not having made enough at the mill to pay for his lodging each week. He searched endlessly for a job until he finally found work several towns over with another tailor, one Mr. Navratil. Mr. Navratil’s shop had an apartment above it, which he rented out to Alek, the only condition being that he had to share it with an old woman who was already living there. Alek gladly took the job and his share of the apartment and began working in earnest. After only a short time, he had saved enough to pay his debt at the boarding house and to buy Mr. Kratochvil many packs of tobacco to repay him for all of his help.

Next followed a rather steady patch in life for Alek. Not since he had lived and worked and trained with his master, Mr. Skalicky, did he feel such contentment. He worked for Mr. Navratil for five years, saving money and making some friends—his first ever, really. His new group of friends were an odd mix of people and included a policeman, a dentist, a pharmacist, a banker, a shoemaker and himself, a tailor. They enjoyed meeting up at the pub each night to play darts, discuss the politics of the day or sometimes just to sing old Bohemian songs together. It was his friend the policeman that he got to know best and who encouraged Alek to buy a newspaper each day and try to teach himself to read. Alek took his advice and, after a while, was able to pick out a little bit and learned to sign his name.

Eventually, however, old Mr. Navratil grew tired of Alek coming home late each night. He feared that he was becoming a drunkard and considered evicting him from the apartment. The old woman Alek lived with, however, Mrs. Dubala, had become quite fond of Alek and spoke up for him. She argued to Mr. Navratil that even though it was true that Alek went each night to the pub to drink, he never came home drunk. She described the way his hand was always steady when he lit the lamp late at night after he came home and how he meticulously laid out his clothes each night for the next day’s work. Begrudgingly, then, Mr. Navratil agreed to let him stay.

Not long after this, however, Alek became very ill. He soldiered on working, despite his illness, for about two months before he told Mr. Navratil that he just couldn’t go on. He went upstairs and asked Mrs. Dubala to bring him some water, drank it, and asked for more and then even more. When he started coughing up blood, he finally told her to go and get the doctor. When the doctor arrived (the same doctor, oddly, that had treated his blistered hands in exchange for his golden curls), he merely touched his forehead and told Mrs. Dubala that if Alek was to live, he would have to immediately be taken by ambulance to the hospital in the next town. So the ambulance was called, and Alek lay between death and life for about twelve hours in the hospital before his fever finally broke.

When Alek awoke, he found himself in a long, dark ward and urgently needed to use the bathroom. He crept out of bed, and even now he remembers how icy the floor felt. His fellow ward mates, alarmed that he was awake and out of bed, called for the nurses, who then ran into the ward and scolded Alek, saying how dare he get out of bed after they had worked so hard to save him. They chastised him severely and threatened to tie him to the bed if he didn’t stay there and rest. Alek obeyed and remained in the hospital for over two months.

When he was finally allowed to go home, the doctors told him to eat lots of bacon and drink wine to enrich his “weak blood” and to stay off from work for one more week. Alek tried to follow these directions and also swore off going out with his friends anymore. But after a few weeks, he was soon back to going to the pub with them and singing the old Bohemian songs.

In 1939, however, Alek’s contented, stable life came to an end with the German invasion.

After the Germans took over, Mr. Navatril’s business dwindled to almost nothing. He tried to stretch the work as far as he could, but in the end, he finally had to let Alek go. Alek understood Mr. Navatril’s dilemma and actually felt sorry for him. He hated to leave him and old Mrs. Dubala and the few friends that were still left, but there was no more work in that particular town. He began to search for a new job and happened to see an ad in the newspaper for a steel mill a short distance away that was desperate for workers. He went and applied for a job and was immediately hired to shovel coke into wagons or the furnace.

When he showed up for his first day, his fellow employees snickered at Alek’s scrawny body and made lots of jokes. Though he was small and thin, somehow Alek had retained his upper body strength and proved that he could throw his load farther than anyone. Soon all of the men wanted him on their team, some of them even offering him food from the farms as an incentive to stay with them. The foreman, however, seeing Alek’s skills, made him move around to all the parts of the factory so that all areas could benefit from his strength.

There was one man, however, by the name of Evzen, who continued to tease Alek about his skinny, scrawny body, though he had heard the rumors about his strength. Evzen, an amateur boxer, was hoping to fight him and continued to goad Alek until he agreed to box him. The resultant boxing match was well attended with many bets being placed, and the workers were shocked when Alek not only beat Evzen, but beat him very badly. Enraged, Evzen swore that he would get his brother to fight Alek. Alek replied that he didn’t want to fight anymore and would rather be friends than enemies. Evzen was apparently taken off guard by Alek’s response, and eventually accepted Alek’s hand in friendship.

Not long after this incident, it was discovered that someone was cutting the train hoses in the steel yard, and somehow Evzen came under suspicion. Alek was one of the few who stood up for Evzen, but in the end he (Evzen) and several others were rounded up and sent to a German prison camp. For a while, Alek was in contact with Evzen, who says that the Germans gave the prisoners “shots” to make them stronger. In reality, though, says Alek, these mysterious shots made all the prisoners sick. Evzen was eventually released, but he was forever ill afterward. When Alek eventually left the country several years later, he sought out Evzen before he left and gave him a new pair of gloves—a very good gift, says Alek, at the time. He heard later that Evzen had died shortly afterwards.

Meanwhile, Alek had his own problem with the Germans. He recalls that on one particular day, after finishing his usual twelve-hour shift at the steel factory, he was packing up his few things to go home, filthy and exhausted, when there was suddenly a commotion in the factory and several German SS soldiers and dogs appeared. They singled out Alek and commanded him to unload a wagon for them. Alek protested, saying that he had already finished his team’s quota and then some. For his insolence, the SS grabbed him and beat him and threw him out on the

Though he had been badly beaten, he still turned up the next day for work, but was told by his foreman that he was fired. Alek protested and accused him of letting him go because he was afraid of the Germans. The foreman did not deny it and remained silent, whereupon, Alek, outraged now, grabbed him and threatened to throw him into the furnace if he didn’t let him keep his job. The foreman then reluctantly let him keep his job, but reassigned him to working outdoors in the yard, though Alek did not have a very thick coat or even proper boots or gloves. When two young boys on Alek’s team tried to stick up for him, the foreman reassigned them to the yard as well. None of them had proper clothing to be working all day outside, but they tried to make the best of it by building little fires from scraps to keep warm.

Several months after this incident, Alek started receiving letters from the main office, three hours away by bicycle, saying that he should report to the office to be reassigned to work in the mines. Alek suspected the interference of the resentful foreman and consequently destroyed the letters. He then discovered that his two young partners were also receiving letters to go to the office to be reassigned. Alek told them they should go if they felt they should, but since they looked to Alek for guidance, they likewise refused to go and destroyed their letters, too.

Finally after Alek had destroyed three such letters, a company officer showed up to interrogate him. He asked Alek about the letters, which Alek denied ever having received. The officer then tried another tactic, imploring him to trust him as he would a father and to tell the truth. Alek, always angered by any reference to his father, then hotly told the officer that he had no father! He admitted, then, however, that not only had he indeed received the letters from the main office but that he had destroyed them. The officer then commanded him to report to the office the next day and to bring the two boys with him. When Alek tried to protest having to bring along two innocent boys, the officer declared that they were now Alek’s responsibility and that he would have to bring them.

Not seeing any way out, Alek decided to go and report to the office the next day with the two boys in tow. There, they were informed that they were going to be sent to Germany to work. Alek, thinking quickly, pretended to laugh and said that in fact he had tried dozens of times to run away to Germany and beyond, but that he had always been stopped at the border because of his American birth certificate, which he always carried on him and which the officer now demanded to see. As Alek showed them the tattered birth certificate, he explained that he was always mistaken for a spy and was thus always denied access. Miraculously, Alek’s plan worked, at least initially, and the three of them were assigned to work on the rail yard instead.

Before long, however, the Russians invaded and took over from where the Germans had left off. Alek decided that working in the steel company’s rail yard was getting much too dangerous and feared that the Russians, who were always hanging about the rail yard, would eventually send him off to work in Siberia. Before that could happen, he again went to the company office and this time informed them that he was quitting and that he wanted his back pay. Their surprising response was that he could not quit. Alek hotly told them that they had no authority over him and demanded his back pay, which they eventually gave him, but not without much stalling and delay.

When the two boys heard he was leaving, they begged him to take them with him. By this point, however, Alek was tired of them constantly clinging to him and feeling responsible for them. They begged for his help, however, so he finally agreed to help the younger one, David. He gave him a little money for the train ride back to his parents and told him not to come back, that it was too dangerous. The older of the two boys, Dusan, stayed working in the rail yard, and he and Alek became friends and sometimes met up in the pub at night.

Since Alek was out of a job now, he could not get “tickets” from the government for food. His old policeman friend, however, came to his rescue and took him around to some of the farms, where they signed notes saying that he was employed there, which allowed him to still get government food tickets while he looked for a real job.

As it turned out, one night while he was in the pub with Dusan, some Russian soldiers came in. Alek and Dusan began talking with them, and they learned that one of the soldiers was a tailor back in the Ukraine. When Alek revealed that he, too, was a tailor, the young soldier suggested that Alek return with him after the war to set up a shop, especially as they were both Ukrainians. Alek then made the mistake of saying that he didn’t fancy living under Communism. The soldier, offended and drunk now, told Alek to shut his mouth. Alek retorted that he certainly would be leaving Czechoslovakia, but that he wouldn’t be going to Russia or the Ukraine, but to America instead!

It was an idea blurted out in the heat of the moment, but it slowly began to take hold in Alek’s mind. Perhaps he really should go to America, he thought. As time went on, it made more and more sense—he had no job, was in constant danger due to the war and had no real options or prospects. And just like that, he decided to try to make it happen, just as his father, ironically, had fled a generation before for mostly the same reasons.

Next week, read Part III, the exciting conclusion: In which our hero flees to America and his many trials and tribulations there . . .

The post Around the World and Back Again: The Nearly Unbelievable Life and Times of Alek Kozel – Part II appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 21, 2017

Around the World and Back Again: The Nearly Unbelievable Life and Times of Alek Kozel

Part I: In which our hero is born in Cristopher, Illinois; finds himself “a slave” on a Ukrainian farm; and becomes a master tailor in Czechoslovakia—all before the age of one and twenty

Alek Kozel was born on September 17, 1913 in Christopher, Illinois to Anton and Anna Kozel, both of whom were Ukranian immigrants. Anton’s father was a shoemaker in a small town near Kiev, and he very much wanted Anton to become one, too. Not only did Anton not wish to become a shoemaker like his father, but he was afraid of the impending threat of war hanging over Europe. In haste, then, he asked his sweetheart, Anna, to marry him, and they ran off to America together.

Anton and Anna somehow found their way to the little town of Christopher in southern Illinois, where Anton was able to get a job in a coal mine. Their first baby, a little girl they named Larisa, died at two months of whooping cough. Their next baby was Alek, who, though small, was healthy and lived. In total, they had eight children who lived past infancy—four boys and four girls.

Anton and Anna struggled to make a life in their new country, Anton toiling in the mines and Anna caring for the children. At one point, however, Anna started getting distressing letters from her mother back in the Ukraine, begging them to return. Anna wrote back faithfully, telling her mother that it was not possible to return, but each time she would enclose a little bit of money for her. Not being able to read, Anna’s mother had to rely on neighbors to read her daughter’s letters to her. Years later, Anna discovered that while the neighbors had indeed read her letters to her mother, they had meanwhile kept all the money for themselves.

As time went on, Anna’s mother’s letters grew more and more desperate, and more than once, Anna attempted to persuade Anton to go back to the Ukraine for a long visit. Anton refused, saying that it he could not leave his job in the mine, and tried to instead persuade Anna to take the children on her own and go. Anna was afraid to go alone, however, so the two continued to argue about what to do. Anton, having been badly burned in the mines twice already, finally began to waver a bit and eventually offered Anna an ultimatum of sorts. He would go back to the Ukraine, he said, if Anna would agree to it being a permanent move. If they returned, he said, it would be for good. Anna was not sure she wanted to give up her life in America, but she was so worried about her mother and her family in the Ukraine, that she agreed.

So, in 1920, Anton and Anna packed up their belongings and their six children at the time (two more would later be born in the Ukraine) and went back. Anton decided to try his hand at farming and rented a farm from the Catholic Church for two years until he found a fourteen-acre farm that he could purchase.

This is when young Alek’s life began to take a downward turn. Alek was just six years old when they took up farming in the Ukraine, but being the oldest, he shouldered a lot of work once they got there. Anton had him working from sunup to sundown beside him on the farm and frequently referred to him as “the slave,” even in front of other people, who sometimes commented to Anton that he was working the boy too hard.

Alek says that his father seemed to love all of his children except for him. He believes this is because he was short with blond, curly hair like his mother, while all of the other children were tall and dark like Anton. Regardless of whether this was true or not, Anton worked Alek ceaselessly and was very short tempered with him. Alek says he doesn’t remember much about his father during the time they lived in America, but his mother, Anna, once confided to him that Anton was like a different man after they came back. It was as if something had “broken” in his mind, and he was now obsessive, irritable and impatient all of the time. To Alek, as the years passed, it always seemed as though his father had a chip on his shoulder, as if he had something to prove.

Thus, poor Alek was required to work all day beside his father. By the age of only eight or nine, he was also required to go into the forest in the evenings after his daily chores to chop wood, half of which Anton sold for extra money. When he finished chopping wood for the evening, Alek then had to go into the barn to shovel out the manure and put down fresh hay before he was allowed to quit for the night.

Alek remembers that one day when he was just nine, he was so exhausted from the day’s chores that he sat down to rest before going out to do his evening chores. When Anton saw him sitting there idly, he became enraged and grabbed a piece of wood and hit Alek on the head with it. Alek remembers doubling over with the pain, but he managed to stumble out to the barn to continue working, though he couldn’t hear anything in his right ear for the rest of the night. In fact, he had permanent hearing damage in that ear and later in life had several surgeries to try to correct it.

There’s no doubt that Alek had a terrible life on the farm in the Ukraine. No matter how hard he worked, his father still seemed to despise him. He was still small for his age but very strong from all of the manual labor. As time went on, however, he became thinner and thinner and had what he calls “weak bones.” He recalls one winter when he was sent out to lead the bull from one pasture to the next and was having a hard time getting the animal to go through the gate. Anton noticed and came over to chastise him and to show him how to properly do it. Neither of them realized that they were standing on a patch of ice, apparently, and when Anton pulled on the bull, the bull slipped and went down, taking Anton and Alek down as well. Somehow, Alek was trampled underneath Anton, and he ended up with a broken sternum, which healed improperly and still sticks out awkwardly today. He also recalls how he didn’t even have shoes, and if stepped on something and cut himself, he was not allowed to stop working. He would have to wrap his bleeding feet with rags and keep going. Needless to say, he never went to school or learned to read or write.

Finally, in 1928, when he was just shy of 15, Alek decided to run away. Anna, discovering his plan, cried and begged him not to go, but Alek couldn’t take it anymore. “I am a slave,” Alek told her. “I have no father,” and set off one night for Czechoslovakia. At some point along the way, the Red Cross came upon him and gave him a set of clothes: two shirts, one pair of short pants, one pair of long pants, shoes and two stockings.

Once in Czechoslovakia, one of the first people he met was a man by the name of Honza Skalicky, who was a tailor by trade. Mr. Skalicky gave the nearly starving boy he saw before him some food and eventually offered to take him on as an apprentice, to which Alek readily agreed. Because he had never gone to school and because he did not know the language, Mr. Skalicky sent him to a sort of school for two years at night in the winters. Meanwhile, he lived with the tailor and was expected to do odd jobs around the house and tend the garden in exchange for his training as a tailor. After what he had been through at the hands of his father on the farm, however, this was almost like heaven. The tailor’s house was a half-hour walk from the shop, and each morning before he set off on his walk to the shop, he was required to wash himself at the well outside the house, whether it was hot or cold, summer or winter.

Besides learning to sew, one of his duties was to deliver the repaired clothing to the customers, and he was delighted when he got tips. The tailor, however, soon discovered this and confiscated these tips, saying that by rights, he should pocket them to cover the cost of the clothes he provided Alek to wear. Alek declared this to be unfair because the tailor was supposed to provide food and clothes as part of their initial agreement. The tailor was resolute, however, saying that he needed the money to buy buttons and accessories, not included in the deal, and Alek had no choice but to turn over the tips.

Alek was not Mr. Skalicky’s only apprentice. In all, Mr. Skalicky employed three or four apprentices at any one time, all at various stages in their training. They all worked together to make one suit at a time and were able to produce fourteen suits per week this way, which was a lot, Alek says. It took Alek four years to learn enough to become a master tailor “with papers.” Just one month short of his “graduation,” however, an unfortunate incident occurred one day which prevented him from doing so.

One that particular day, Alek walked into the work room and witnessed the tailor screaming at a new apprentice for something he had done and hitting him on the head. Memories flooded Alek’s mind of his own father hitting him on the head with the block of wood, and something “just snapped,” Alek says. He became enraged and picked up a nearby pair of scissors and threatened to kill Mr. Skalicky if he didn’t stop. Apparently terrified, the tailor rushed out of the shop with Alek pursuing him before Alek came to his senses and let Mr. Skalicky go. Horrified by what he had done, however, Alek stayed away from the tailor’s house and shop for over a month before he realized what he needed to do. He was nothing without his “papers,” which he had worked for for over four years. So, gathering his courage, he slunk back to the tailor and apologized. The tailor took him back, and Alek was able to finish his apprenticeship and graduate.

At the time, it was 1932, and Czechoslovakia was in a severe depression. Alek set off trying to find a job as a master tailor, but no jobs were to be found. It was as though he had done all of that work for nothing. He travelled around a bit, looking for work, before he finally went back to see his old master, Mr. Skalicky. The tailor offered him a position in his shop in exchange for room and board only, no money—an offer Alek was insulted by. The conversation between the two became heated, with Alek declaring that he’d rather shovel manure. A neighbor overheard them arguing and told Alek he was a fool not to take the tailor’s offer, but Alek retorted, “Don’t worry, I’ll never come begging at your door!” and left.

As it turned out, Alek did come very close to begging after several months of wandering from town to town in search of work. Eventually he had to eat his words and really did get a job shoveling out the contents of outhouses into a wheelbarrow and spreading it on fields for farmers. He also got jobs cutting grass with a long sickle. He slept in parks and ate whatever rotten fruit he found on the ground under trees.

Eventually, as would be expected, his health began to decline and his hands became covered in blisters. Not being able to work with blisters all over his hands, he decided to seek out a doctor for help. Before the doctor examined him, however, Alek told him that he had no money to pay him. After studying him for a few moments, the doctor said he would treat his hands and charge it to a rich customer of his who wouldn’t know the difference if Alek would agree to cut his long curly blond hair and give it to him. Though this seemed an odd request, Alek agreed, knowing he could always grow his hair back, and so had it cut accordingly in exchange for treatment for his hands. He was also losing his teeth due to his poor diet, so he asked the doctor what he could do about it. The doctor advised him to rub lemons on his gums from time to time, which Alek laughed at—as if he had access to lemons!

Alek then went on his way and continued to sleep in parks until one day he saw an older man pasting up posters in the park. The man asked him where he was living, and when Alek told him he was basically living in the park, the man offered to let him stay at his boarding house. Alek informed him that he didn’t have any money to pay, but the man said not to worry, that he would find him a job. The man’s name was Josef Kratochvil and he lived in a basement apartment of the boarding house, where he spent much of the day smoking tobacco. He had a son and a daughter living in some of the rooms above him. His son, Mr. Kratochvil explained, was apprenticed to a baker, which made sense when Alek eventually met him, as he was very large and was also losing his teeth, both of which Alek put it down to sampling too many of the bakers’ wares.

Being the owner of the building, Mr. Kratochvil offered Alek a place to stay, which Alek accepted, promising to pay as soon as he could. Alek eventually met all the tenants in the building, including a man by the name of Mr. Chvatal on the top floor, who had grown quite wealthy from buying wheat from local farmers and reselling it in Prague. He offered Alek a job sewing patches in wheat sacks where mice had chewed through. It was a messy, dirty job, but Alek readily took it. After only a short time of working for him, Mr. Chvatal was impressed with Alek’s hard work and began to trust him more and more. Eventually, he arranged to have Alek sleep in the office to guard the safe at night and gave him a small raise as compensation for this extra duty.

Things were going along pretty well until one day when Mr. Chvatal left for Prague as usual to sell another load of wheat. Not long after he was gone, Mrs. Chvatal called Alek in from the mill and asked him to come upstairs to help her carry the laundry. Alek obeyed, but when he got upstairs, he found Mrs. Chvatal, dressed only in a housecoat. To his dismay, she then untied the belt to reveal her underthings to him. Stunned, Alek quickly told her he wasn’t that type of man and wanted no part of this and then ran out of the house. When Mr. Chvatal returned several days later, his wife, apparently stinging from Alek’s rejection, informed him that Alek had made advances to her and insisted he be fired. Mr. Chvatal seemed reluctant to lose his best worker, but he ultimately listened to his wife and fired Alek. At this point he was just twenty-one years old . . .

Read Part II next week: In which the Germans and then the Russians invade, and our hero finds himself escaping the clutches of many different foes . . .

The post Around the World and Back Again: The Nearly Unbelievable Life and Times of Alek Kozel appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 14, 2017

“All I Know Is Horses”

Leon Carter, Jr. was born on September 21, 1950 in El Dorado, Arkansas to Leon Carter, Sr. and Norma Jones. Leon, Sr. and Norma knew each other from little on. Not only did they go to school together, but their families were good friends and they were often together. Leon and Norma eventually fell in love and married. Leon worked in construction and did odd jobs, and Norma was a housewife. Shortly after their first child, Leon, Jr. was born, however, Norma abandoned them both and ran off to Chicago. She eventually married another man, Mario Sanchez, and had one daughter, Donna, with him. Later she married a third man, Reed Bryant.

Leon Carter, Jr. was born on September 21, 1950 in El Dorado, Arkansas to Leon Carter, Sr. and Norma Jones. Leon, Sr. and Norma knew each other from little on. Not only did they go to school together, but their families were good friends and they were often together. Leon and Norma eventually fell in love and married. Leon worked in construction and did odd jobs, and Norma was a housewife. Shortly after their first child, Leon, Jr. was born, however, Norma abandoned them both and ran off to Chicago. She eventually married another man, Mario Sanchez, and had one daughter, Donna, with him. Later she married a third man, Reed Bryant.

Leon Sr. did his best to raise “junior,” but when young Leon was about nine years old, his mother, Norma, reappeared in El Dorado, Arkansas and insisted on taking him back with her to Chicago. Norma put him in school here, and in the summers, he worked at the racetrack. After he finished tenth grade, he quit school and began working at the track full-time.

Leon says that he started at the bottom and worked his way up to being a groomsman. He began his career as a “hot walker,” which meant that he walked the hot horses after a race until they cooled down. He was a fast learner, he says, and quickly learned the best way to cool a horse, how much water to give them, etc., and how to care for them in general. He became an expert at horses, and his services were much sought after through the years.

Leon didn’t have much time for hobbies, but he did enjoy fishing, baseball, and playing cards or dominoes. He lived with his mother and his half-sister, Donna, until one day he met a young woman by the name of Patricia Woods, who was a co-worker of his mother’s. Leon and Patricia hit it off right away, and Leon soon moved in with her and her three daughters: Beverly, Cynthia and Deborah. Leon and Patricia never married, but they lived together for over fifteen years and had two sons together, Leon III and Robert.

Leon continued working at the track during the summers, but in the winters, he would head to New Orleans, where he worked at a track there. It turns out that in New Orleans, Leon had another girlfriend, Darlene Hayes, whom he lived with each winter for over twenty years.

Meanwhile, back in Chicago, Patricia was getting tired of Leon being gone half the year while she cared for five kids alone, and she decided to leave him. Leon claims that she was an alcoholic who was growing increasingly paranoid and suspicious of everything around her, including Leon and his double life in New Orleans.

Unfortunately, right at about the time when Patricia officially left him, Leon began experiencing some serious health problems. His legs were beginning to swell, and after going to the hospital, he was diagnosed with diabetes and kidney problems. He was in Chicago, so he couldn’t rely on Darlene, his New Orleans girlfriend/common-law wife, and his mother, Norma, had died several years before. Likewise, his father had since moved to California and had become a minister. His only choice seemed to be to go and live in Cabrini Green with his half-sister, Donna, his mother’s child with Mario Sanchez, and her six children, the oldest of whom was eighteen. Unbeknownst to Leon, however, Donna was a drug addict and soon stole all of his possessions and sold them for drug money, though she swore it wasn’t her.

Leon managed to put up with this living situation for a couple of years. Sadly, during that time, he got word that Patricia also died. He would have liked to go to the funeral, he says, but he didn’t know about it and blames his sons for not telling him. Both Leon III and Robert had apparently become estranged from their father over the years. Leon III had long since moved out of Patricia’s house and was living with his fiancé, and Robert was sharing an apartment with his half-sister, Cynthia, Patricia’s daughter by another man.

Leon was very upset by Patricia’s death, but he soon had other things to worry about. Right at about that time, Donna decided to jump ship as well and left Leon with her six children in the Cabrini Green apartment. Leon was still working on and off at the track, though he was limited in what he could do because of his health and did not get many hours. He tried to take care of his nieces and nephews as best he could, but the older ones especially did not appreciate their Uncle Leon’s involvement and blamed him for their mother, Donna’s, mysterious disappearance. Leon tried to teach them how to cook and fend for themselves, but often they rebelled against him and, as his health grew worse and he became weaker, they sometimes even refused to give him food.

Leon’s health continued to decline, and he eventually had to have his left leg and his right foot amputated due to complications with his diabetes. He then went blind and had to rely entirely on whatever care or scraps his nephews or nieces would give him, the two youngest girls—Pamela, age twelve, and Jennie, age ten—being the most sympathetic to him.

Then out of the blue one day, Donna magically reappeared, apparently “strung-out,” says Leon, and threatened to go away again and take all of the children with her this time so that he would have to care for himself. As it turned out, however, as he ended up going to the hospital yet again and had to have extensive dialysis.

While in the hospital this time, Darlene, his girlfriend from New Orleans, appeared, saying that she wanted to be back in his life and take care of him. They soon fought, however, before he was even released from the hospital, and she declared their relationship over and went back to New Orleans. The staff at the hospital tried to reach his two sons, but they were not responsive. The hospital social worker then suggested that Leon be admitted to a nursing home, and, not having any other choice, he reluctantly agreed. He is hoping for prosthetic limbs, however, and a chance to get his own apartment.

While Leon says he is grateful to be somewhere getting care, he is dealing with a lot of conflicting emotions, especially anger. He says that his life’s motto has been to “grin and bear it,” but he admits to having a “hot temper,” which has affected many of his relationships in life. “I guess I screwed up my life,” he says. “All I really know is horses.”

Leon is depressed and sad that not one member of any of his various families have come to see him, nor has he gotten one card or phone call. He does not like to mix with the other residents because he sees himself as so much younger than them, but he is likewise bored and irritable. He is not accepting of the diabetic diet the staff have put him on, among other things, and is often verbally abusive to staff members because of it. He says he is biding his time until he can get his own place, sadly choosing to believe that Darlene might still come through for him.

(Originally written: May 1996)

The post “All I Know Is Horses” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 7, 2017

A Brilliant Team—Married for 65 years!

Jan Marek was born on October 13, 1903 in Chicago to Zavis Marek and Valerie Reha. Zavis and Valerie were both immigrants from Czechoslovakia, but they met in Chicago and married here. They had three children that lived: Jan, Victor and Teresa. Jan says that he often heard whisperings that his mother had had six miscarriages, but both parents refused to talk about it, even if asked directly. They also refused to talk about their life in Czechoslovakia.

Jan Marek was born on October 13, 1903 in Chicago to Zavis Marek and Valerie Reha. Zavis and Valerie were both immigrants from Czechoslovakia, but they met in Chicago and married here. They had three children that lived: Jan, Victor and Teresa. Jan says that he often heard whisperings that his mother had had six miscarriages, but both parents refused to talk about it, even if asked directly. They also refused to talk about their life in Czechoslovakia.

Zavis owned a butcher shop, which the whole family helped to run, on Chicago’s northwest side. Jan and Victor worked there from a young age, and Jan had to learn to kill chickens, ducks and geese even as a little boy. Jan says it was “hard, hard work,” especially before they had refrigeration or automobiles. Neither Jan nor his brother Victor enjoyed working as butchers, and one day, they finally worked up the courage to tell Zavis that they had no desire to inherit the shop or to help keep it running once they were grown. Zavis was apparently saddened by this news, but he agreed to let his sons pursue their own livelihood. When it was time for him to retire, he sold the shop, then, instead of passing it down to them.

Jan meanwhile graduated from 8th grade and got a job delivering groceries. His parents made him pay room and board from that point on. Jan worked hard, however, and managed to still save some money, even after having to pay his parents most of his salary. He continued to get various jobs, each one paying a little bit more, until, when he was twenty-one, he had saved enough money to put a third down on a hardware store.

Thus, young Jan became the proud owner of a hardware store, and he put his all into making it a success. He was a very social young man and knew from his many years working in his father’s butcher shop, how to treat customers. He loved board games and sports and had a lot of friends. He was usually “the life of the party,” and could be found playing the piano and singing and dancing at get-togethers. It was at one such party at a friend’s that he was introduced to a young woman, Sonia Dusek, and the two immediately hit it off. They dated for a year and then got married and moved into the apartment above the hardware store.

Jan and Sonia were a brilliant team, apparently, both of them working very closely together to make the store a success. They worked hard all day and then would lock up the shop at closing time and go out dancing or catch a show. They both loved movies and saw almost every one that came out. They were always socializing with friends or family and often went to Jan’s parents to play cards.

The Mareks never had any children, however. Even though they were a very close couple, Jan says they never really discussed it. To his understanding, Sonia never really wanted any children, speculating that it might have had something to do with the fact that she was from a big family. “It was probably for the best,” Jan says now, though there is perhaps the tiniest hint of regret in his voice.

When they were just short of fifty years old, Sonia one day declared that they should sell the hardware store and retire early. Jan was caught off guard by this sudden announcement, but after he had “time to think about it,” he decided that it wasn’t a bad idea. So they put the store up for sale, and it sold very quickly. The Mareks then bought a small bungalow on Pulaski Avenue to move into, having to give up their little apartment above the shop, and then began traveling. They also continued to go out dancing and to movies as well as to socialize extensively with friends and family, including Jan’s parents, whom they saw each week to play cards with.

Jan’s father, Zavis, died when he was eighty-six of esophageal cancer. He had been diagnosed with it two years before, but refused to have any kind of treatments. He died after a night of card-playing with Jan and Sonia. As he was going up to bed, he had a horrible coughing fit, and as Jan helped him to bed, “both of us knew he wasn’t going to make it through the night,” and they said their goodbyes. Jan’s mother, Valerie, then came to live with Jan and Sonia for the next fifteen years. She died at age one hundred in Jan’s arms.

Jan and Sonia continued to live in the bungalow on Pulaski until their own health began to fail a bit. It was Sonia’s idea to move to the Momence Retirement Center in Momence, Illinois, where one of her sisters lived. Jan agreed to go, and they attempted to start a new life there. After only one year, however, Sonia passed away. She and Jan had been married for sixty-five years.

It was Sonia’s last wish to be buried by her parents in the Bohemian National Cemetery in Chicago, so Jan honored that with the help of the staff at the retirement community. Not wanting to return to Momence to live, however, without Sonia, he decided to move to a nursing home near the cemetery. He was able to do this mostly on his own, despite being ninety-one years old, though he had some help from his niece, Donna, who flew in from Seattle, Washington to help him get situated. She is his closest relative and is concerned for her Uncle Jan, but she is obviously not able to participate very much in his care. Jan remains very independent, however, and much of the admission process was handled by himself.

Jan is making a relatively smooth transition to nursing home life, though he is somewhat quiet and withdrawn. When asked, he says that he still misses Sonia, but he is “trying to make the best of it, the way she would have,” he says. He interacts well with other residents one-on-one, but seems to shy away from big group activities or events, saying his eyesight is too poor to enjoy much. He does still love music, though, and can often be heard singing to himself.

(Originally written: May 1995)

The post A Brilliant Team—Married for 65 years! appeared first on Michelle Cox.

November 30, 2017

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

Glenn Brown was born on June 26, 1909 to Calvin Brown and Elaine Edwards, both of whom were immigrants from Australia. Calvin was a construction worker, and Elaine cared for their nine children: Timothy, Glenn, Charlotte, Theodore, Ida, Pearl, Leon, and Martin and Mary, who were twins. Glenn went to school until the eighth grade, but then quit to begin working construction alongside his father. Unfortunately, however, Calvin died young of a heart attack, and it fell on Glenn and Timothy to support the family.

Glenn Brown was born on June 26, 1909 to Calvin Brown and Elaine Edwards, both of whom were immigrants from Australia. Calvin was a construction worker, and Elaine cared for their nine children: Timothy, Glenn, Charlotte, Theodore, Ida, Pearl, Leon, and Martin and Mary, who were twins. Glenn went to school until the eighth grade, but then quit to begin working construction alongside his father. Unfortunately, however, Calvin died young of a heart attack, and it fell on Glenn and Timothy to support the family.

Glenn worked construction all his life and is proud of the fact that he worked on the “giants of the city,” including the Tribune Tower, the Chicago Board of Trade, The Prudential Building, and even the Hancock. He was not afraid of heights, he says, and enjoyed working “in the clouds.”

Glenn’s one hobby in life was playing baseball, and he joined quite a few local leagues in his youth. One year, the team he was on was sponsored by a tavern which had an adjoining liquor store. After each game, the team would frequent the tavern, with Glenn stopping at the liquor store afterwards before going home. The liquor store was managed by a young woman by the name of Wanda Ardelean, and Glenn began looking forward to seeing her each week, as “she was so easy to talk to.” Each time he went into the store, Glenn asked Wanda out on a date, but each time she said no. Finally, Glenn decided that he would ask her just one more time, and if she again said no, he would stop going to the liquor store altogether and just give up.

So, “on August 3, 1942,” he remembers clearly, he walked into the liquor store and again asked Wanda to go to the pictures with him. Expecting her to reject him, he was shocked and thrilled when she said yes! From that time on, the two began dating and eventually married. Not long after their wedding, however, the war broke out, and Glenn had to report for duty in the navy. He served for two and half years in Europe while Wanda continued to live with her parents and work at the liquor store.

When Glenn came back from the war, the couple got their own apartment on Belmont, and Glenn went back to working construction. Wanda continued at the liquor store, planning to quit as soon as she got pregnant, but, sadly, she never did. Glenn says he was disappointed not to have any children, especially as he came from such a big family, but “it couldn’t be helped,” he says. “It wasn’t meant to be.” He and Wanda instead became a favorite aunt and uncle to his many nieces and nephews. They also joined various bowling and card leagues over the years. He and Wanda never traveled much, he says, because “I was too busy working.” When he did have spare time, Glenn says that he “did a little gardening,” and he liked to read, especially the paper.

Glenn and Wanda lived in the apartment on Belmont their whole married life, both of them astoundingly working the same jobs they had when they first met. Glenn worked until he was sixty-five, when he had to retire after he got “laid up” after having various minor surgeries. Then, in 1988, his beloved Wanda passed away, which was terribly hard on Glenn. After that, he lived alone in the apartment on Belmont, but he relied heavily on his sisters, Ida and Pearl, and their families for help. His sister, Charlotte, had already passed away, and Mary became a nun early in life. All of his brothers were either dead or living in another state, so it fell on Ida and Pearl, or their children, to stop over to make sure Uncle Glenn was okay or to help him shop or clean.

This arrangement worked for several years until just recently. Glenn fell earlier in the year in his apartment and was taken by some neighbors to the hospital, where it was discovered that he was also suffering from pneumonia. After spending several weeks there, recovering, the discharge staff at the hospital did not feel he would be able to adequately care for himself at home, so nursing home placement was recommended. Glenn is upset at being admitted and blames the doctor for putting him here. His sisters have tried to explain that they cannot care for him, having their own health issues, and that it is safest for him here. He accepts this, but he sometimes forgets and then gets frustrated all over again. His family is extremely supportive of him, though, and someone visits at least once per week, and often more.

Meanwhile, Glenn seems to be trying to make the best of his situation. “You have to work hard and keep busy,” is his motto for getting through hard times, “like now,” he says. He enjoys watching baseball on TV with other male residents and playing bingo, but at times can be found clearing tables or straightening chairs in the dining room for “something to do.”

(Originally written: June 1996)

The post Standing on the Shoulders of Giants appeared first on Michelle Cox.

November 23, 2017

A Leap of Faith

Simona Novotny was born on November 25, 1901 in Blatnice, Czechoslovakia to Joseph Novotny and Pavla Adamik and was the youngest of nine children. Joseph was a flax farmer who routinely traveled to Germany in the off months to sell his flax. Simona says he made a good living this way because the Germans were eager to buy flax to make carpets “for the long winters.” Both of her parents were very healthy, Simona says, and lived into their nineties when they both died of “old age.”

Simona Novotny was born on November 25, 1901 in Blatnice, Czechoslovakia to Joseph Novotny and Pavla Adamik and was the youngest of nine children. Joseph was a flax farmer who routinely traveled to Germany in the off months to sell his flax. Simona says he made a good living this way because the Germans were eager to buy flax to make carpets “for the long winters.” Both of her parents were very healthy, Simona says, and lived into their nineties when they both died of “old age.”

Both of Simona’s brothers became butchers, and her six sisters all married tradesmen of some sort. Phyllis, however, after completing the eighth grade, wanted something else. She and her girlfriends wanted to go to America. Many people from her village had already made the journey, and, since she was the youngest of nine, Simona explains, her mother finally relented.

So it was, then, that the summer after Simona turned eighteen, she and four of her friends set sail for America. The sea voyage took twenty days. When they got to America, they made their way to Detroit, Michigan, where a sister of one of the girls lived. Simona quickly found a job as a maid in a church rectory.

Oddly, after only a couple of months of being in this new country, she happened to run into a young man she knew from her village of Blatnice. He was older than her and had been in the same class as one of her brothers. Simona didn’t know him all that well, but it was nice to see someone she recognized. His name was Joseph Novotny, the same as her father. Simona wasn’t too surprised by the coincidence of his name, as it is a very common one, she says, in Czechoslovakia. She was surprised, however, when Joseph asked her to marry him not long after they became reacquainted. “He was very persuasive,” says Simona, and, almost on impulse, she decided to take a chance and marry him. They went to the justice of the peace to get married, but later had their marriage blessed in the Catholic Church.

After only a few months, Joseph suggested they move to Chicago, where he said he had many friends. Simona wasn’t so sure she wanted to leave all of her friends, but she decided to trust Joseph and agreed to move to Chicago. As it turned out, they were quickly enveloped by the Czech community there, many people from their village having immigrated to Chicago after the war.

The Novotnys found an apartment on the northwest side, and Joseph got a job with a company that made auto parts for General Motors. Simona remained at home as a housewife and cared for their three sons: Frank, Joseph, and David. Simona was an avid gardener and was also very involved in her church, St. Sylvester’s, in Logan Square. She was part of the St. Vincent DePaul society and also the Altar and Rosary. She and Joseph never travelled much, except once to Detroit and once to Niagara Falls, preferring instead to stay at home.

Simona and Joseph apparently had a very happy marriage. They were a very social couple and had many friends. They often invited people over to their house for parties, and they always had a big Thanksgiving dinner, especially since it was usually on or around Simona’s birthday, and would invite lots of people from the neighborhood who had nowhere else to go.

The only real tragedy that befell the Novotnys was when their son, David, died at age twenty in a freak car crash. David’s death was particularly devastating to Simona because he was her favorite. She went into a depression for quite some time, but she eventually came out of it. “You have to stay positive, no matter what,” she says, even now. Her sons say that it was her intense faith that got her through that time, though how Joseph coped, they don’t know, as he refused to ever talk about David after the funeral. Simona, on the other hand, says that she takes comfort in knowing she will see David again someday in heaven.

In the early 1970’s, Joseph again persuaded Simona to move, this time to Union Pier, Michigan to retire. There they again made many friends, and Simona had a very big yard in which to garden, despite the fact that she had just turned seventy. After only four years of being there, however, Joseph died suddenly one morning of a heart attack while shoveling snow. He was seventy-eight. Simona remained in Union Pier for another sixteen years. Recently, however, at age ninety-two, she has become afraid to stay there any longer on her own. She is in remarkably good health, but she decided that she wanted to come back to Chicago and move into a Czech nursing home where her friend, a Mrs. Cerveny, resides.

Simona’s two sons, Frank and Joseph Jr. helped her to make the arrangements, and she is making a very smooth transition to nursing home life. She is extremely cheerful and positive and is enjoying having all of her meals prepared for her, especially some of her Czech favorites, though she says she herself makes them a little differently. Still, she says, she is grateful. She seems very interested in all of the activities the home has to offer, but so far spends most of her free time visiting and talking with Mrs. Cerveny, who is delighted to have her old friend back.

The post A Leap of Faith appeared first on Michelle Cox.

November 16, 2017

Outfoxed

Anna Fox was born on April 12, 1918 in Russia to Aron and Riva Kaplan. Aron was a shoemaker, and Riva cared for their five children: Anna, Lev, Isak, Boris, and Klara. All but Klara survived childhood. Like many people of that era, Aron and Riva were desperate to leave Russia, but they could not obtain visas to the United States. Instead, they opted to go to Cuba, hoping that they would eventually find a way into America.

Anna Fox was born on April 12, 1918 in Russia to Aron and Riva Kaplan. Aron was a shoemaker, and Riva cared for their five children: Anna, Lev, Isak, Boris, and Klara. All but Klara survived childhood. Like many people of that era, Aron and Riva were desperate to leave Russia, but they could not obtain visas to the United States. Instead, they opted to go to Cuba, hoping that they would eventually find a way into America.

Anna was only about four or five when the Kaplans arrived in Cuba. She attended school and learned Spanish very quickly. She even graduated from high school, after which she found various jobs around Havana, which is where the Kaplans had settled. In 1944, when she was twenty-six years old, Anna was finally granted permission to go to America, though the exact details of how that came about have been lost over the years. Apparently, it had something to do with Aron having a brother and a sister-in-law living in Chicago, and Anna was allowed to go and live with them. She quickly found a job in a factory that made envelopes and tried to learn English. Not long after, her brother, Lev, arrived and after finding a job, he and Anna were able to get their own little apartment, working and saving to eventually bring the rest of the family over.

Anna was apparently a quiet girl who had few hobbies beyond knitting and crocheting. She had few boyfriends, so when some friends from work introduced her to a handsome soldier just back from the war, Anna was quickly smitten. Bert Fox swept Anna off her feet and asked her to marry him not long after they started dating. He had a good job at Allied Appliance in the shipping department, and Anna said yes to him, despite the fact that they did not know each other all that well.