Gennaro Cuofano's Blog, page 149

July 5, 2021

What happened to Vine?

Vine was an American video social networking platform with a focus on looping video clips of six seconds in length, founded by Dom Hofmann, Rus Yusupov, and Colin Kroll in 2012 to help people capture casual moments in their lives and share them with their friends. Vine went on to become a massively popular platform. Yet by 2016, Twitter discontinued the mobile app while allowing users to view or download content on the Vine website. It then announced a reconfigured app allowing creators to share content to a connected Twitter account only. This marked the end of Vine.

BackgroundVine was an American video social networking platform with a focus on looping video clips of six seconds in length.

The platform was founded by Dom Hofmann, Rus Yusupov, and Colin Kroll in 2012 who had the vision to help people capture casual moments in their lives and share them with their friends.

Hofmann, Yusupov, and Kroll pitched the idea for Vine to Twitter because they believed the short-form vlogging service would complement Twitter’s short-form microblogging platform. Twitter then acquired Vine for $30 million before the app was even launched.

Vine went on to become a massively popular platform, attracting 200 million users in the first two years including countless celebrities. Just four years after it was founded, Twitter discontinued the mobile app while allowing users to view or download content on the Vine website. It then announced a reconfigured app allowing creators to share content to a connected Twitter account only.

The original app was then renamed Vine Camera but faded into obscurity after suffering poor reviews and usage.

The reason for Vine’s demise is due to multiple factors. Let’s take a look at them now.

Growing competitionIn the words of a former Vine executive, ”Instagram video was the beginning of the end.”

When Instagram launched its video feature in 2013, users could create and share short-form videos of a maximum duration of fifteen seconds.

This caused a mass migration of users from Vine to Instagram for nothing else but increased video length.

Failure to understand the marketAs noted earlier, Vine was initially conceived as a microvlogging platform where users could share short videos with their friends.

After the platform was launched, it became clear that Vine was in fact an entertainment media platform. It was predominantly comprised of passive viewers who preferred to consume content in a similar vein to platforms such as YouTube.

This left the job of content creation to a very small percentage of users who would compromise the integrity of the whole platform if they decided to leave.

Unfortunately, Vine gave content creators two reasons to leave the platform and take their followers with them. First, it stubbornly adhered to a maximum video length of six seconds which was too short for a so-called microvlogging service. Second, Vine did not allow creators to monetize their sometimes large audiences.

Platform monetizationMonetization issues were not restricted to creators. Vine as a business was not making any money either.

Executives were reluctant to experiment with potential monetization methods during rapid growth periods. Funds that were flowing into the Vine ecosystem were mostly sponsorship deals for the very top content creators – there was no attempt to sponsor the platform itself.

Twitter made a belated attempt to monetize Vine by purchasing a social media talent agency, but the agency could not incentivize clients to remain on Vine in the face of better monetization on other platforms.

Parent company strategic directionTwitter acquired Vine before it was launched to use the platform to grow its own brand and business. Ultimately, Vine as a standalone brand was not a priority of Twitter shareholders.

This was exemplified when Twitter launched its own video creation feature, thereby invalidating the need for Vine entirely.

Key takeaways:Vine was a microvlogging platform founded in 2012. It quickly rose to prominence after acquiring 200 million users in the first two years of operation.Four years later, the service was progressively discontinued by Twitter. Competition from Instagram was one of the primary reasons for Vine’s demise because it offered longer video length for creators.Vine’s popularity was also unsustainable because of the high proportion of passive viewers when compared to content creators. Many such creators migrated to other platforms and took their audiences with them because of a lack of monetization functionality.What if it survived?By the 2020s, the short video format empowered by

TikTok makes money through advertising. It is estimated that ByteDance, its owner, made over $17 billion in revenues, for 2019. While we don’t know the exact figure for TikTok ads revenues, given it counted over 800 million users by 2020, it is a multi-billion company, worth anywhere between $50-100 billion and among the most valuable social media platforms of the latest years.

TikTok makes money through advertising. It is estimated that ByteDance, its owner, made over $17 billion in revenues, for 2019. While we don’t know the exact figure for TikTok ads revenues, given it counted over 800 million users by 2020, it is a multi-billion company, worth anywhere between $50-100 billion and among the most valuable social media platforms of the latest years.  Instagram makes money via visual advertising. As part of Facebook products, the company generates revenues for Facebook Inc. overall business model. Acquired by Facebook for a billion dollar in 2012, today Instagram is integrated into the overall Facebook business strategy. In 2018, Instagram founders, Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, left the company, as Facebook pushed toward tighter integration of the two platforms.

Instagram makes money via visual advertising. As part of Facebook products, the company generates revenues for Facebook Inc. overall business model. Acquired by Facebook for a billion dollar in 2012, today Instagram is integrated into the overall Facebook business strategy. In 2018, Instagram founders, Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, left the company, as Facebook pushed toward tighter integration of the two platforms.  Twitter is a platform business model, monetizing the attention of its users in two ways: advertising and data licensing. In 2018, advertising represented 86% of its revenue at over $2.6 billion. And data licensing represented over $424 million primarily related to enterprise clients using data for their analyses.

Twitter is a platform business model, monetizing the attention of its users in two ways: advertising and data licensing. In 2018, advertising represented 86% of its revenue at over $2.6 billion. And data licensing represented over $424 million primarily related to enterprise clients using data for their analyses. Evan Spiegel and Robert Cornelius Murphy are the co-founders and respectively, CEO and CTO of Snapchat. Evan Spiegel owns 5.9% of Class A stocks, 23.9% of Class B stocks, and 53.9% of Class C stocks for a 53.6% voting power where Robert Murphy owns 7.9% of Class A stocks, 23.9% of Class B stocks, and 46.7% of Class C stocks for a 46.5% voting power.

Evan Spiegel and Robert Cornelius Murphy are the co-founders and respectively, CEO and CTO of Snapchat. Evan Spiegel owns 5.9% of Class A stocks, 23.9% of Class B stocks, and 53.9% of Class C stocks for a 53.6% voting power where Robert Murphy owns 7.9% of Class A stocks, 23.9% of Class B stocks, and 46.7% of Class C stocks for a 46.5% voting power. Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsBlockchain Business Models FrameworkThe post What happened to Vine? appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

What happened to Palm?

Palm, Inc. was an American manufacturer of personal digital assistants (PDAs) and other electronics. founded in 1992 by Jeff Hawkins, its popularity tended to be restricted to early adopters. Despite the company revolutionizing mobile computing, it no longer exists today. Palm’s demise was caused by poor decision-making, squandered resources, and misplaced effort. The company got stuck in the “chasm.”

BackgroundPalm, Inc. was an American manufacturer of personal digital assistants (PDAs) and other electronics.

The company was founded in 1992 by Jeff Hawkins, who together with Donna Dubinsky and Ed Colligan invented the Palm Pilot. The Pilot was one of the earliest and indeed most successful PDAs of its time, making the Palm brand synonymous with technology and innovation.

Although a revolutionary product, the Palm Pilot was not a mass-market consumer item and its popularity tended to be restricted to early adopters. Nevertheless, it was less than half the price and more feature-rich than its main competitor the Apple Newton.

In his book, Crossing the Chasm, Geoffrey A. Moore shows a model that dissects and represents the stages of adoption of high-tech products. The model goes through five stages based on the psychographic features of customers at each stage: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggard.

In his book, Crossing the Chasm, Geoffrey A. Moore shows a model that dissects and represents the stages of adoption of high-tech products. The model goes through five stages based on the psychographic features of customers at each stage: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggard.Palm also created several versions of webOS – an operating system for smartphones, and the enyo.js HTML5 framework for apps.

Despite the company revolutionizing mobile computing, it no longer exists today. Palm’s demise was caused by poor decision-making, squandered resources, and misplaced effort.

Let’s tell that story below.

U.S Robotics Corp. acquisitionThe trouble began when the Palm founders sold the company to U.S. Robotics to fund their first product launch.

Unfortunately, securing the necessary funding came with a heavy added cost. Hawkins, Dubinsky, and Colligan lost control over the company and the product forever.

One year later, U.S. Robotics was acquired by 3Com. This caused the founders to resign and launch Handspring, the developer of the first mass-market smartphone called the Treo.

Meanwhile, 3Com made Palm an independent, publicly tradeable company in March 2000.

Spin-offs, mergers, and corporate mismanagementIn January 2002, Palm made the disastrous decision to spin out its software division into an independent company called PalmSource.

Just over twelve months later, Palm merged with Handspring and became PalmOne. In a rather convoluted process, PalmOne then spent $30 million buying the Palm trademark from PalmSource and subsequently changed its name back to Palm.

This was followed by another costly decision in December 2006 where Palm paid $44 million to access the Palm OS source code it developed and once owned.

Generic productsCorporate mismanagement also changed the very culture of the company. In the early years, Palm won multiple design awards for innovation with a laser-like focus on product quality and invention.

As the company started to become more successful, it became preoccupied with corporate partnerships, new markets, and bland product launches. Indeed, Palm products became progressively more generic and uninspired as control over the company shifted from product visionaries to executives in suits.

Competition and HP acquisitionWhile Palm smartphones were the first of their kind, they couldn’t compete with offerings from Blackberry and then Apple. Blackberry offered internet capability instead of just email, while Apple upped the ante significantly with the release of the first iPhone in 2007.

Importantly, the iPhone was a complete, standalone device that did not need to be synchronized with a computer like the Pilot. In response, Palm released the Palm Pre in 2009 which ran on a new operating system called webOS. The Pre was plagued with quality control issues, including screen cracking, faulty headphone jacks, and design issues with the slide-out keyboard. It was also built on underlying hardware which made it slower than the iPhone.

Palm could not compete with the emergence of Apple and was acquired by HP in 2010 for $1.2 billion. HP tried to address the quality control issues but was ultimately unsuccessful in increasing market share.

It later sold webOS to LG who now use it to power smart televisions. The Palm brand itself was later sold to a shelf corporation tied to the Chinese electronics company TCL.

Key takeaways:Palm was a revolutionary producer of personal digital assistants considered to be the precursors to the smartphone. Palm squandered its first-mover advantage because of poor decision-making and mismanagement. The company undertook a series of convoluted spin-offs, mergers, and acquisitions where funds were needlessly spent buying back its own technology and trademarks.Palm was also handicapped by a change in corporate culture that favored bland and uninspiring products instead of innovation. It could not compete with Apple who embodied the innovative traits Palm once stood for.Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsBlockchain Business Models FrameworkThe post What happened to Palm? appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

July 2, 2021

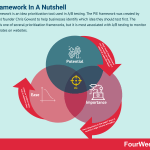

PIE Framework In A Nutshell

The PIE framework is an idea prioritization tool used in A/B testing. The PIE framework was created by WiderFunnel founder Chris Goward to help businesses identify which idea they should test first. The framework is one of several prioritization frameworks, but it is most associated with A/B testing to monitor conversion rates on websites.

Understanding the PIE frameworkThe business must understand where to focus its time and effort because it cannot test every idea at the same time. In other words, the PIE framework helps key decision-makers determine which website features should be tested now and which can be tested at a later juncture.

Without a proper prioritization framework in place, businesses become overwhelmed by the sheer number of choices and suffer from analysis paralysis. What’s more, they may end up focusing their efforts in the wrong areas which leads to significant opportunity costs.

The three components of the PIE frameworkThe PIE framework considers three factors that make up the PIE acronym: potential, importance, and ease.

When moving through the framework, the business can score each factor in a matrix according to how significant the impact of a proposed change may be. A scale of 1 to 5 or 1 to 10 is commonly used.

Let’s now take a look at each of three factors:

P is for Potential – how much improvement can be made on a page as a result of a specific idea? Here, the worst-performing pages should be given a higher score since they have the most room for improvement. Consider customer data, web analytics data, and heuristic analysis of user scenarios.I is for Importance – how important is the page? Does it receive a high volume of traffic? Will the change impact a visitor’s ability to complete a transaction? Note that some of the worst-performing pages identified in the previous section may be a low priority because they receive comparatively little traffic, so score accordingly. Web analytics can help identify important pages such as landing pages with high bounce rates. It’s also helpful to consider the financial cost of bringing visitors to a page. Indeed, pages with high-cost traffic sources are more important because conversion improvements have the potential to deliver a better return on investment.E is for Ease – how complex is the task, project, or idea? In other words, how easily will it be completed and how long will it take? Barriers to implementation include technical, organizational, or even political issues. Tasks deemed as easier to implement should be given a higher score.To determine which tasks should be prioritized, add the scores for each factor and divide by three to get the PIE value. For example, a task with a score of 7 for potential, 8 for importance, and 5 for ease receives a PIE value of 6.67.

Key takeaways:The PIE framework is an idea prioritization tool used in A/B website or page testing.The PIE framework helps businesses assign resources to initiatives with the most potential to positively impact their bottom line.The PIE framework is an acronym of three factors: potential, importance, and ease. Decision-makers must assign weighted scores to each factor and then sum each score to determine task priority.Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsBlockchain Business Models FrameworkThe post PIE Framework In A Nutshell appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

Brandjacking In A Nutshell

A business engaged in brandjacking assumes the identity of another brand to access its audience while also undermining its identity, integrity, authority, or messaging.

Understanding brandjackingIn simple terms, an entity engaged in brandjacking is pretending to be someone they are not to damage brand equity or reputation. Brandjacking is a portmanteau of “brand” and “hijacking” and was coined by domain management solution provider MarkMonitor.

The most obvious example of brandjacking can be seen in phishing scams. Between 2013 and 2015, Facebook and Google lost more than $100 million after being sent fake invoices via email. The invoices were sent by a Lithuanian hacker masquerading as an Asian manufacturer the companies regularly did business with.

Brandjacking is also prevalent on social media. Here, malicious actors create accounts with branded profile pictures to give the impression they represent the company they are trying to discredit. After Target announced it would remove gender descriptions from in-store signage, individuals posing as customer support representatives were rude and dismissive toward actual customer concerns. Similar instances of impersonation on Facebook have also targeted prominent figures such as Barack Obama, Sarah Palin, and many other politicians and major corporations.

Lastly, brandjacking may take the form of advertising campaigns. In 2010, Greenpeace campaigners created a video that parodied Nestle KitKats and highlighted the company’s use of unsustainable palm oil as an ingredient. Greenpeace also protested outside the Nestle UK headquarters with altered slogans using the Nestle typeface and brand colors.

How can businesses and consumers protect against brandjacking?With brandjacking attempts growing more sophisticated, it is unlikely any single action will prevent them from occurring in the future.

However, there are several preventative measures the exploited entity can take.

These include:

Using social listening tools – businesses should invest in tools enabling them to track conversations about their brand. This means they can go into damage control early should they be subject to brandjacking. After failing to monitor social media mentions, Heinz fell victim to an anonymous Twitter user who pitched the company’s products based on personal political opinions.Create a crisis management response – this helps the relevant department to respond and adapt to situations quickly. Purchase brand-related domains – in addition to the primary domain, businesses should register variations similar to their brand name or important keywords. They should also register common misspellings or alternative domain name extensions where possible. This prevents others from registering them with malicious intent.Become more discerning of incoming emails – consumers should avoid becoming victims by carefully analyzing emails asking them to upgrade credit cards or other sensitive information. Instead of clicking on dubious links within emails, the individual should contact the company directly to confirm whether a problem exists.File trademarks – while trademarks are not a panacea against brandjacking, they do act as a deterrent and deliver important benefits to the business. Chief among these include the right to sue a malicious actor in court and also entitlement to specific, brand-related damages. Key takeaways:Brandjacking involves an individual acquiring or otherwise assuming the identity of a brand or business under false pretenses. The goal is almost always to discredit or damage brand equity or reputation.Brandjacking can take multiple forms. The most obvious example is phishing, where malicious actors falsely represent companies for financial gain. Brandjacking is also seen on social media and in advertising campaigns.Brandjacking can be mitigated but never avoided completely. Social media listening tools and a crisis management response are effective ways for businesses to limit negative exposure. Consumers must also be wary and vigilant of emails asking them to disclose personal information.Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsBlockchain Business Models FrameworkThe post Brandjacking In A Nutshell appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

zk-SNARK Technology In A Nutshell

zk-SNARK technology is cryptographic proof allowing one party to prove it possesses information without having to reveal it. zk-SNARK is an acronym for Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge. More specifically, a zk-SNARK is a zero-knowledge proof protocol used to prove possession of certain information without revealing that information. This technology might play a key role in the future development of Ethereum.

Understanding zk-SNARK technologyThe first zero-knowledge proofs were developed in the late 1980s, with a seminal research paper entitled How to Explain Zero-Knowledge Protocols to Your Children released in 1990 by cryptographer Jean-Jacques Quisquater.

The paper explains zero-knowledge proofs in the context of a parable involving Ali Baba’s Cave. But for the sake of brevity, it’s important to understand that these proofs have one fundamental goal and three key players. The verifier must convince themselves that the prover possesses knowledge of a secret parameter called a witness. This witness must satisfy some relation without it being revealed to the verifier or indeed anyone else.

In a real-world scenario, imagine a patron wanting to enter a bar and having to prove they were over the legal drinking age of 21. The patron does not want to reveal their exact age, but the bouncer at the door must verify whether they are legally allowed to drink. Theoretically, the bouncer could use zero-knowledge proofs to scan the patron’s ID and determine whether they were over 21. Note that the exact age of the patron does not need to be revealed.

Today, zk-SNARK is commonly associated with cryptocurrency and blockchain. We will take a look at this association in the next section.

zk-SNARK technology and cryptocurrencyWhen cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin were first developed, privacy was less important than a need to create a trust-less system for maintaining the integrity of digital transactions.

Indeed, Bitcoin users assumed such transactions were anonymous because their real identities were not associated with user public keys. In recent years, concerted attempts by data scientists, hackers, and law enforcement proved it was relatively simple to identify people who had given pseudonymous information to multiple sources.

This put the spotlight back on privacy and lead to the development of coins such as Zcash that were backed by zk-SNARK technology. This technology is based on complex mathematical functions, but in the case of Zcash, zk-SNARKS can be verified nearly instantly without any interaction between the prover and the verifier. The identity of the prover and verifier are kept hidden, as is the payment amount. Importantly, zk-SNARKS usually take up much less data than a standard Bitcoin transaction and are more scalable as a result.

Future applications of zk-SNARKszk-SNARK has virtually limitless future applications because it is useful wherever verification is required without disclosing inputs or leaking information.

Having said that, its usefulness is somewhat limited since the generation of proofs for complex functions is resource-intensive. In cryptocurrency, the makers behind Zcash are working to optimize this process to make it more widely available.

In any case, zk-SNARKs can be added to any existing distributed ledger solution to add an extra layer of security for enterprise use cases. This solution is particularly attractive for multiple companies operating on the same blockchain with a desire to keep sensitive or proprietary business information private. Instead of revealing this information to other players, zk-SNARKS allow each business to store only the proof of each transaction on a given node.

Key takeaways:zk-SNARK technology is cryptographic proof allowing one party to prove it possesses information without having to reveal it.zk-SNARK technology is most commonly associated with blockchain and cryptocurrency, but it was coined as far back as the late 1980s by cryptographer Jean-Jacques Quisquater.zk-SNARK technology is a vital tool for multiple businesses operating on the same blockchain with sensitive information. The technology will become much more widespread once verification functions become less computationally intensive.Read Next: Blockchain Business Models Framework Decentralized Finance, Blockchain Economics, Bitcoin, Hard-Fork.

Read Also: Proof-of-stake, Proof-of-work, Blockchain, ERC-20, DAO, NFT.

Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsBlockchain Business Models FrameworkThe post zk-SNARK Technology In A Nutshell appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

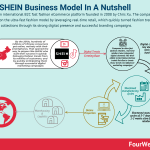

How Does SHEIN Make Money? The SHEIN Business Model In A Nutshell

SHEIN is an international B2C fast fashion eCommerce platform founded in 2008 by Chris Xu. The company improved on the ultra-fast fashion model by leveraging real-time retail, which quickly turned fashion trends in clothes’ collections through its strong digital presence and successful branding campaigns.

SHEIN Origin StorySHEIN is an international B2C fast fashion eCommerce platform founded in 2008 by Chris Xu.

After graduating from the Qingdao University of Science and Technology, Xu was hired as an SEO consultant for an online marketing company. There, he realized the commercial value of selling Chinese goods to international markets via the internet.

SHEIN was founded as SheInSide and exclusively sold wedding dresses. In the early days of the company, it operated like many other fashion retailers. Xu would scour the Chinese wholesale clothes market for items he thought had the potential to be popular in Western markets. Products were advertised on the website and purchased from the wholesaler once there was sufficient demand.

Using Xu’s SEO expertise, SHEIN experienced a high volume of sales – leaving little time to launch new products. In response, Xu decided to change direction by reimagining SHEIN as a women’s clothing brand with its own supply chain in 2014.

Two years later, the company had a design team consisting of 800 people. It uses Google Trends and other data to identify new clothing trends ahead of time. SHEIN now offers clothing for men and women including accessories such as bags and shoes.

In recent years, SHEIN has acquired multiple fashion rivals to become a truly global presence. The company claims to ship to 220 countries and territories with annual revenue estimated to be $10 billion. Like many online retailers, SHEIN has benefitted from the COVID-19 pandemic.

How SHEIN built upon the ultra-fast fashion model and into real-timeTo understand how we got to the SHEIN business model, it’s worth highlighting the evolution of the fashion industry, from a business standpoint, of the last decades.

Indeed, by late 1990s, early 2000s, a phenomenon driven by companies like Zara and H&M took over: Fast Fashion.

Fash fashion has been a phenomenon that became popular in the late 1990s, early 2000s, as players like Zara and H&M took over the fashion industry by leveraging on shorter and shorter design-manufacturing-distribution cycles. Reducing these cycles from months to a few weeks. With just-in-time logistics, flagship stores in iconic places in the largest cities in the world, these brands offered cheap, fashionable clothes and a wide variety of designs.

Fash fashion has been a phenomenon that became popular in the late 1990s, early 2000s, as players like Zara and H&M took over the fashion industry by leveraging on shorter and shorter design-manufacturing-distribution cycles. Reducing these cycles from months to a few weeks. With just-in-time logistics, flagship stores in iconic places in the largest cities in the world, these brands offered cheap, fashionable clothes and a wide variety of designs.Fast fashion was based on a few key premises. If we take a player like Zara, who most represented this phenomenon, the company leveraged fast following trends developed by high-fashion brands. It built its strengths on shorter manufacturing cycles, just-in-time logistics, and massive investments in flagship stores located in most city centers across the globe.

This model enabled the stores to operate at a fast turnover by offering a wide variety of inexpensive clothes that changed each week. This speed, variety, and convenience became the key strengths of fast-fashion players.

And this business model worked pretty well until the 2010s. Since then, e-commerce penetration has dramatically increased in most European countries, also favored by the birth of mobile commerce. And it’s worth noting that hundreds of millions of Chinese consumers, thanks to mobile commerce, got online, natively with their smartphones (as we’ll see, this would play a key role in developing ultra-fast fashion first and real-time retail then).

The Ultra Fashion business model is an evolution of fast fashion with a strong online twist. Indeed, where the fast-fashion retailer invests massively in logistics, warehousing, its costs are still skewed toward operating physical retail stores. While the ultra-fast fashion retailer mainly moves its operations online, thus focusing its cost centers toward logistics, warehousing, and a mobile-based digital presence.

The Ultra Fashion business model is an evolution of fast fashion with a strong online twist. Indeed, where the fast-fashion retailer invests massively in logistics, warehousing, its costs are still skewed toward operating physical retail stores. While the ultra-fast fashion retailer mainly moves its operations online, thus focusing its cost centers toward logistics, warehousing, and a mobile-based digital presence. Therefore, ultra-fast fashion really worked as an evolution from fast fashion. And its key strengths relied on a strong online presence, primarily driven by mobile e-commerce. That managed to create a feedback loop between users’ feedback about fashion trends, manufacturing, and the quick availability of these items on the digital properties of the ultra fast-fashion retailer.

In short, the ultra fast-fashion retailer invested most of its resources in capturing fashion trends even faster, by further shortening manufacturing cycles and making its items readily available on its online properties, and therefore investing massively in logistics to easily distribute these clothes to millions of customers across the world, without the burden to have to operate physical stores.

This leads us to the evolution that led to the SHEIN business model. With the further rise of social media platforms like TikTok by the 2020s, SHEIN further mastered the ability to grasp fashion trends while also further shortening cycles quickly.

This is at the core of real-time retail. The experience becomes so fast that in a few days, the cycle from fashion trends picking up to clothes collections; shortens to just a few days!

Real-time retail involves the instantaneous collection, analysis, and distribution of data to give consumers an integrated and personalized shopping experience. This represents a strong new trend, as a further evolution of fast fashion first (who turned the design into manufacturing in a few weeks), ultra-fast fashion later (which further shortened the cycle of design-manufacturing). Real-time retail turns fashion trends into clothes collections in a few days cycle or a maximum of one week.

Real-time retail involves the instantaneous collection, analysis, and distribution of data to give consumers an integrated and personalized shopping experience. This represents a strong new trend, as a further evolution of fast fashion first (who turned the design into manufacturing in a few weeks), ultra-fast fashion later (which further shortened the cycle of design-manufacturing). Real-time retail turns fashion trends into clothes collections in a few days cycle or a maximum of one week.In a way, SHEIN really mastered the digital distribution channels into its business model, to capture or create fashion trends faster, and to easily market them to its millions of shoppers.

The key digital channels SHEIN leverages to quickly create fashion trends and convert them into mobile shoppers. SHEIN’s brand popularity is the main strength of its digital marketing strategy (data source SimilarWeb).

The key digital channels SHEIN leverages to quickly create fashion trends and convert them into mobile shoppers. SHEIN’s brand popularity is the main strength of its digital marketing strategy (data source SimilarWeb). SHEIN’s brand has become increasingly popular by 2018, by leveraging digital marketing (data source: KeywordsEverywhere).

SHEIN’s brand has become increasingly popular by 2018, by leveraging digital marketing (data source: KeywordsEverywhere).  SHEIN also mastered social media channels, which as of now bring substantial traffic back to its site, without counting the further exposure from TikTok (data source SimilarWeb).

SHEIN also mastered social media channels, which as of now bring substantial traffic back to its site, without counting the further exposure from TikTok (data source SimilarWeb).  SHEIN also leverages display advertising, especially on YouTube, to create buzz, amplify the brand and lead conversion (data source SimilarWeb).

SHEIN also leverages display advertising, especially on YouTube, to create buzz, amplify the brand and lead conversion (data source SimilarWeb).  The SHEIN “plus-size” or “curve clothing line” has incredible success, and it seems among the most successful parts of the business (data source KeywordsEverywhere).SHEIN revenue generation

The SHEIN “plus-size” or “curve clothing line” has incredible success, and it seems among the most successful parts of the business (data source KeywordsEverywhere).SHEIN revenue generationSHEIN makes money by purchasing clothing from wholesalers and then selling items for a profit.

However, the company has several unique ways of maximizing its profits. Let’s take a look at them below.

Ghost factoriesMany argue that SHEIN behaves more like a food delivery company than a fashion company.

Food delivery apps that run so-called ghost kitchens appeal to consumers who prioritize price and convenience over the brand or name of the restaurant. These apps also control the order management system of the restaurant and provide real-time inventory level data.

Instead of ghost kitchens, SHEIN utilizes ghost factories. The company approaches factories with archaic inventory management practices and offers to install its own order system in exchange for guaranteed consumer demand. SHEIN then teaches factories how to respond to real-time consumer preferences and in the process, make the fashion retailer more money.

Targeted marketing and vertical integration Customer segmentation is a marketing method that divides the customers into sub-groups, that share similar characteristics. Thus, product, marketing, and engineering teams can center the strategy from go-to-market to product development and communication around each sub-group. Customer segments can be broken down in several ways, such as demographics, geography, psychographic, and more.

Customer segmentation is a marketing method that divides the customers into sub-groups, that share similar characteristics. Thus, product, marketing, and engineering teams can center the strategy from go-to-market to product development and communication around each sub-group. Customer segments can be broken down in several ways, such as demographics, geography, psychographic, and more.The fast-fashion retail model is most often utilized by those under the age of 25. SHEIN targets this demographic by offering on-trend clothing at competitive prices.

As we noted earlier, the company is increasingly vertically integrated. Through high-volume manufacturing, it also benefits from economies of scale. Both these factors allow SHEIN to undercut competitors such as H&M, Zara, and ASOS.

Brand awareness is focused on social media platforms such as Instagram and YouTube using influencers to produce videos with millions of views. Again, this targets the younger generation who tend to discover new fashion brands through real-life friendship networks and recommendations.

Gamification Gamification borrows key concepts from the gaming industry to encourages user engagement and experience. Some of those concepts include competitiveness, mastery, sociability, achievement, and status. With the application of game principles to the business context, companies can design products that are more enjoyable to users and customers.

Gamification borrows key concepts from the gaming industry to encourages user engagement and experience. Some of those concepts include competitiveness, mastery, sociability, achievement, and status. With the application of game principles to the business context, companies can design products that are more enjoyable to users and customers.SHEIN drives more revenue by gamifying the consumer purchasing experience. For one, there are so many different products for sale that finding a clothing item replicating a high-end look is like finding a needle in a haystack. This is made all the more difficult when one considers that many popular clothing items become sold out very quickly.

These factors have resulted in so-called “SHEIN haul” vlogs where satisfied customers proudly share their clothing finds with others. This drives brand loyalty and increases word-of-mouth advertising

Key takeaways:SHEIN is an international B2C fast fashion platform. The company was founded in 2008 by Chris Xu, who recognized the power of SEO to promote Chinese-made clothing to the world.SHEIN makes money by purchasing wholesale clothes and then selling them for a profit. It operates thousands of ghost factories that utilize proprietary inventory level management systems to increase supply chain efficiency.SHEIN maximizes profits by understanding its target demographic, becoming vertically integrated, and utilizing economies of scale. This makes the company ultra-competitive against the likes of ASOS and H&M.Read Next: ASOS, Zara, Fast Fashion, Ultra-Fast Fashion, Real-Time Retail.

Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsBlockchain Business Models FrameworkThe post How Does SHEIN Make Money? The SHEIN Business Model In A Nutshell appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

July 1, 2021

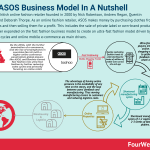

How Does ASOS Make Money? The ASOS Business Model In A Nutshell

ASOS is a British online fashion retailer founded in 2000 by Nick Robertson, Andrew Regan, Quentin Griffiths, and Deborah Thorpe. As an online fashion retailer, ASOS makes money by purchasing clothes from wholesalers and then selling them for a profit. This includes the sale of private label or own-brand products. ASOS further expanded on the fast fashion business model to create an ultra-fast fashion model driven by short sales cycles and online mobile e-commerce as main drivers.

BackgroundASOS is a British online fashion retailer founded in 2000 by Nick Robertson, Andrew Regan, Quentin Griffiths, and Deborah Thorpe.

ASOS was originally called As Seen on Screen and sold items used by celebrities in film and television. This included a diverse range of products, including a mortar and pestle used by celebrity chef Jamie Oliver and a wallet that appeared in the movie Pulp Fiction.

In 2002, the company became ASOS and was floated on the London Stock Exchange. While it continued to promote fashion items worn by celebrities, Robertson noted that own-brand fashion offered higher profit margins. Two years later, the first ASOS-brand womenswear was launched and the company made its first profit after endorsements from celebrities such as Rihanna and Michelle Obama. Beauty products, jewelry, accessories, and own-brand menswear soon followed.

In 2010, ASOS launched online shopping for consumers in the USA, France, and Germany. The following year, it opened its first international office in Sydney, Australia, and then another in New York City.

Today, ASOS has an active user base of approximately 24.5 million with revenue soaring to nearly £2 billion in the 6 months to February 2021.

Understanding the Ultra Fashion Business ModelThe Ultra Fashion business model is an evolution of fast fashion with a strong online twist.

Fash fashion has been a phenomenon that became popular in the late 1990s, early 2000s, as players like Zara and H&M took over the fashion industry by leveraging on shorter and shorter design-manufacturing-distribution cycles. Reducing these cycles from months to a few weeks. With just-in-time logistics, flagship stores in iconic places in the largest cities in the world, these brands offered cheap, fashionable clothes and a wide variety of designs.

Fash fashion has been a phenomenon that became popular in the late 1990s, early 2000s, as players like Zara and H&M took over the fashion industry by leveraging on shorter and shorter design-manufacturing-distribution cycles. Reducing these cycles from months to a few weeks. With just-in-time logistics, flagship stores in iconic places in the largest cities in the world, these brands offered cheap, fashionable clothes and a wide variety of designs. Zara had mastered this model. Its strength relied on:

Quickly replicating designs: Zara initially didn’t innovate in terms of design. Instead, it copied fashion trends. Therefore, it fast followed the existing trends created by high-fashion players.Mass manufacturing them: Zara also had mastered quickly and cheaply manufacturing its clothes to achieve extreme speed. Where competitors or existing players took six months to turn the design into clothes available at the store, Zara took this to another level, shortening the design-manufacturing cycle to as low as 2-4 weeks. Mass distribution and logistics: Another key element of this strategy was making logistics a core competency of Zara. As these clothes could be easily made available in all its stores. By leveraging a “just-in-time” process, Zara distributed clothes across the stores from its central warehouses (perhaps in Spain), making the clothes available within 48 hours in any of the European stores. Flagship retails: Zara also invested in a marketing/distribution strategy where stores would be located in iconic and central places in the major cities across the globe. This is both a marketing and distribution strategy as the millions of tourists checking Zara’s store every day also could get comforted by the fact of finding Zara anywhere they were going (not that dissimilar to finding a MacDonald’s restaurant anywhere in the world). And this strategy of flagship stores also worked as a distribution strategy as its clothes could be easily made available to millions of consumers each day. High turnover: Another key element of Zara’s strategy was the high turnover of clothes. In short, each week, fashion shoppers could find different styles of clothes, thus creating a sort of addicting shopping mechanism, where you could go shopping with more and more frequency.As the 2010s came, more and more shoppers turned to online retail. This brought to a further evolution where online players, or at least those able to leverage their online presence, could quickly gather the feedback of users, by further reducing the time from design to manufacturing/distribution.

Therefore, ultra-fast fashion is a further evolution of fast fashion. How did it evolve? By simply relying on online stores, rather than building a physical presence. For instance, in the case of ASOS all its efforts are invested in further shortening the design-to-sales cycles.

As ASOS highlights on its website:

We’re all about online at ASOS so you won’t find us in your local mall. We’ve got hundreds of brands and thousands of products that just wouldn’t fit into a store.

Instead we focus our efforts on bringing you thousands of new products each week and the latest fashion news and tips via our Women’s and Men’s homepages.

You don’t have to worry about opening and closing times or trying to find a parking spot – just log on from the comfort of your own home and start shopping. We’ve also got a mobile site and app so you can shop while on the go.

To better understand this transition from fast fashion toward ultra-fast fashion, we need to give a glance at ASOS’ financials.

The trend toward casual clothes has been accelerated by the pandemic and that has favoured ASOS. In fact, from a quick glance at its financials it’s possible to see how the company has further accelerated its sales and global customers acquisition:

Data Source: ASOS Financial Statements

Data Source: ASOS Financial StatementsWhen looking at the financials of ASOS, it’s interesting to note a few things:

The company has a high marginality, with most of its sales coming from retail. This is thanks to the fact that ASOS is online-only. Thus, it uses its cash to invest in shortening the design-sales cycles, rather than operating massive stores, as it has been in the past for fast fashion retails like Zara or H&M.Among its key metrics there are the total visits, conversions, and mobile device visits. As it’s clear from its KPIs, mobile shoppers represent the majority (they grew to 86.3% in 2021). With a strong mobile presence, ASOS has incorporated the social shopping experience into its process thus, managing to increase the average units per basket and the frequency to which mobile shoppers place orders (over 3 orders per year with an average selling price of 23 pounds, and an average basket value of 71 pounds as shoppers usually have three items at least in their baskets).More Like A Software CompanyAs the company highlights The ASOS Experience is a continuous process of “beta testing:”

At ASOS, we never settle. We have an always testing, “always in beta” philosophy, constantly improving every day. From free delivery and returns to innovative visual search tech, if it hasn’t been done before, we find a way to do it anyway.

Since ASOS is a online-only player, it’s critical that shoppers can trust it, as such its customer service must be much superior than a service you would expect from a physical retail.

That is why ASOS incentivises free delivery and returns. It also makes it easy to its internal visual search to match and find related items to improve the conversion per purchase.

ASOS Revenue ModelAs an online fashion retailer, ASOS makes money by purchasing clothes from wholesalers and then selling them for a profit. This includes the sale of private label or own-brand products.

It also makes money through usage fees, commission fees, and advertising revenue. Let’s take a look at each below.

ASOS MarketplaceVendors who wish to sell their products on the ASOS Marketplace are charged a monthly usage fee of £20.

For each successful sale, the company also takes a 20% commission.

The exact usage and commission fee will of course vary from country to country.

Private label salesPrivate label sales profits are maximized because ASOS designs and then delivers its own brands. This vertical integration allows the company to effectively manage inventory levels and collect 100% of the total amount of each sale.

Advertising revenueASOS also earns money by charging third-party businesses to advertise on its platforms. This includes the eCommerce site and ASOS Magazine.

Premier DeliveryPremier Delivery is a service giving members unlimited and free express delivery in metropolitan areas and standard delivery elsewhere. The service also offers free returns and in some cases, no minimum order spend.

Premier Delivery is available in fifteen countries worldwide and is available for a recurring yearly subscription fee. Again, pricing is variable and based on the country of origin.

In Australia, the service is AUD 39 per year. In the United Kingdom, Premier Delivery is worth £9.95 per year.

Key takeaways:ASOS is a British online retailer founded in 2000 by Nick Robertson, Andrew Regan, Quentin Griffiths, and Deborah Thorpe. Originally, ASOS sold items popularised by celebrities in film and television.ASOS drives revenue by charging vendors who wish to sell on its platform a commission fee and monthly usage fee. In the private label space, vertical integration allows the company to control more of the process and maximize profits.ASOS also earns money by offering advertising on its website and in its magazine. Premier Delivery is also offered to consumers who want access to free and unlimited shipping in fifteen countries.Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsBlockchain Business Models FrameworkThe post How Does ASOS Make Money? The ASOS Business Model In A Nutshell appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

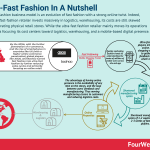

Ultra-Fast Fashion Business Model

The Ultra Fashion business model is an evolution of fast fashion with a strong online twist. Indeed, where the fast-fashion retailer invests massively in logistics, warehousing, its costs are still skewed toward operating physical retail stores. While the ultra-fast fashion retailer mainly moves its operations online, thus focusing its cost centers toward logistics, warehousing, and a mobile-based digital presence.

From Fast Fashion to Ultra-Fast Fashion Fash fashion has been a phenomenon that became popular in the late 1990s, early 2000s, as players like Zara and H&M took over the fashion industry by leveraging on shorter and shorter design-manufacturing-distribution cycles. Reducing these cycles from months to a few weeks. With just-in-time logistics, flagship stores in iconic places in the largest cities in the world, these brands offered cheap, fashionable clothes and a wide variety of designs.

Fash fashion has been a phenomenon that became popular in the late 1990s, early 2000s, as players like Zara and H&M took over the fashion industry by leveraging on shorter and shorter design-manufacturing-distribution cycles. Reducing these cycles from months to a few weeks. With just-in-time logistics, flagship stores in iconic places in the largest cities in the world, these brands offered cheap, fashionable clothes and a wide variety of designs. Zara had mastered this model. Its strength relied on:

Quickly replicating designs: Zara initially didn’t innovate in terms of design. Instead, it copied fashion trends. Therefore, it fast followed the existing trends created by high-fashion players.Mass manufacturing them: Zara also had mastered quickly and cheaply manufacturing its clothes to achieve extreme speed. Where competitors or existing players took six months to turn the design into clothes available at the store, Zara took this to another level, shortening the design-manufacturing cycle to as low as 2-4 weeks. Mass distribution and logistics: Another key element of this strategy was making logistics a core competency of Zara. As these clothes could be easily made available in all its stores. By leveraging a “just-in-time” process, Zara distributed clothes across the stores from its central warehouses (perhaps in Spain), making the clothes available within 48 hours in any of the European stores. Flagship retails: Zara also invested in a marketing/distribution strategy where stores would be located in iconic and central places in the major cities across the globe. This is both a marketing and distribution strategy as the millions of tourists checking Zara’s store every day also could get comforted by the fact of finding Zara anywhere they were going (not that dissimilar to finding a MacDonald’s restaurant anywhere in the world). And this strategy of flagship stores also worked as a distribution strategy as its clothes could be easily made available to millions of consumers each day. High turnover: Another key element of Zara’s strategy was the high turnover of clothes. In short, each week, fashion shoppers could find different styles of clothes, thus creating a sort of addicting shopping mechanism, where you could go shopping with more and more frequency.As the 2010s came, more and more shoppers turned to online retail. This brought to a further evolution where online players, or at least those able to leverage their online presence, could quickly gather the feedback of users, by further reducing the time from design to manufacturing/distribution.

Therefore, ultra-fast fashion is a further evolution of fast fashion. How did it evolve? By simply relying on online stores, rather than building a physical presence. For instance, in the case of ASOS all its efforts are invested in further shortening the design-to-sales cycles.

As ASOS highlights on its website:

We’re all about online at ASOS so you won’t find us in your local mall. We’ve got hundreds of brands and thousands of products that just wouldn’t fit into a store.

Instead we focus our efforts on bringing you thousands of new products each week and the latest fashion news and tips via our Women’s and Men’s homepages.

You don’t have to worry about opening and closing times or trying to find a parking spot – just log on from the comfort of your own home and start shopping. We’ve also got a mobile site and app so you can shop while on the go.

To better understand this transition from fast fashion toward ultra-fast fashion, we need to give a glance at ASOS’ financials.

The trend toward casual clothes has been accelerated by the pandemic and that has favoured ASOS. In fact, from a quick glance at its financials it’s possible to see how the company has further accelerated its sales and global customers acquisition:

Data Source: ASOS Financial Statements

Data Source: ASOS Financial StatementsWhen looking at the financials of ASOS, it’s interesting to note a few things:

The company has a high marginality, with most of its sales coming from retail. This is thanks to the fact that ASOS is online-only. Thus, it uses its cash to invest in shortening the design-sales cycles, rather than operating massive stores, as it has been in the past for fast fashion retails like Zara or H&M.Among its key metrics there are the total visits, conversions, and mobile device visits. As it’s clear from its KPIs, mobile shoppers represent the majority (they grew to 86.3% in 2021). With a strong mobile presence, ASOS has incorporated the social shopping experience into its process thus, managing to increase the average units per basket and the frequency to which mobile shoppers place orders (over 3 orders per year with an average selling price of 23 pounds, and an average basket value of 71 pounds as shoppers usually have three items at least in their baskets). Source: Inditex Financials

Source: Inditex FinancialsWhere a fast-fashion player like Zara has most of its operational costs skewed toward stores (which in Zara’s case are both a distribution and marketing tool), an ultra-fast fashion player like ASOS instead has most of its operational costs toward warehousing, logistics (delivery), and digital marketing/social media marketing.

Source: ASOS Financials

Source: ASOS Financials While also Zara is converting a good chunk of its activities to online, the main difference between a fast-fashion player and an ultra-fast fashion one is the online-only presence of the latter. Furthermore, the online presence is skewed toward mobile shoppers.

Fash fashion has been a phenomenon that became popular in the late 1990s, early 2000s, as players like Zara and H&M took over the fashion industry by leveraging on shorter and shorter design-manufacturing-distribution cycles. Reducing these cycles from months to a few weeks. With just-in-time logistics, flagship stores in iconic places in the largest cities in the world, these brands offered cheap, fashionable clothes and a wide variety of designs.

Fash fashion has been a phenomenon that became popular in the late 1990s, early 2000s, as players like Zara and H&M took over the fashion industry by leveraging on shorter and shorter design-manufacturing-distribution cycles. Reducing these cycles from months to a few weeks. With just-in-time logistics, flagship stores in iconic places in the largest cities in the world, these brands offered cheap, fashionable clothes and a wide variety of designs. Real-time retail involves the instantaneous collection, analysis, and distribution of data to give consumers an integrated and personalized shopping experience. This represents a strong new trend, as a further evolution of fast fashion first (who turned the design into manufacturing in a few weeks), ultra-fast fashion later (which further shortened the cycle of design-manufacturing). Real-time retail turns fashion trends into clothes collections in a few days cycle or a maximum of one week.

Real-time retail involves the instantaneous collection, analysis, and distribution of data to give consumers an integrated and personalized shopping experience. This represents a strong new trend, as a further evolution of fast fashion first (who turned the design into manufacturing in a few weeks), ultra-fast fashion later (which further shortened the cycle of design-manufacturing). Real-time retail turns fashion trends into clothes collections in a few days cycle or a maximum of one week.Read Also: Shein, Wish, Poshmark, Etsy, Fast Fashion, Real-Time Retail.

Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsBlockchain Business Models FrameworkThe post Ultra-Fast Fashion Business Model appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

Fast Fashion Business Model In A Nutshell

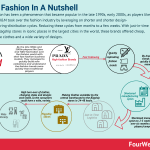

Fash fashion has been a phenomenon that became popular in the late 1990s, early 2000s, as players like Zara and H&M took over the fashion industry by leveraging on shorter and shorter design-manufacturing-distribution cycles. Reducing these cycles from months to a few weeks. With just-in-time logistics, flagship stores in iconic places in the largest cities in the world, these brands offered cheap, fashionable clothes and a wide variety of designs.

Origin StoryFast fashion players took over the industry around the late 1990s and the early 2000s; those players like Zara and H&M “innovated” in a few ways. The core strength of the fash fashion industry relied on the replication of trends from high-fashion designers. Thus turning these trends into clothes and making them readily available in most retail stores located in central, iconic places in the largest cities across the world.

Zara had mastered this model. Its strength relied on a few key elements.

Fast Following Fashion TrendsBy quickly replicating designs, Zara initially didn’t innovate in these terms. Instead, it copied fashion trends. Therefore, it fast followed the existing trends created by high-fashion players. The key here was quickly turning these trends into clothes available in its stores.

Here being quick meant reducing the time it took to bring to manufacturing clothes, as previously it took months.

Shortened Manufacturing CyclesZara also had mastered quickly and cheaply manufacturing its clothes to achieve extreme speed by mass manufacturing them. Where competitors or existing players took six months to turn the design into clothes available at the store, Zara took this to another level, shortening the design-manufacturing cycle to as low as 2-4 weeks.

Just-in-Time LogisticsMass distribution and logistics: Another key element of this strategy was making logistics a core competency of Zara. As these clothes could be easily made available in all its stores. By leveraging a “just-in-time” process, Zara distributed clothes across the stores from its central warehouses (perhaps in Spain), making the clothes available within 48 hours in any of the European stores.

Iconic, Flagship StoresFlagship retails: Zara also invested in a marketing/distribution strategy where stores would be located in iconic and central places in the major cities across the globe. This is both a marketing and distribution strategy as the millions of tourists checking Zara’s store every day also could get comforted by the fact of finding Zara anywhere they were going (not that dissimilar to finding a MacDonald’s restaurant anywhere in the world). And this strategy of flagship stores also worked as a distribution strategy as its clothes could be easily made available to millions of consumers each day.

Wide VarietyHigh turnover: Another key element of Zara’s strategy was the high turnover of clothes. In short, each week, fashion shoppers could find different styles of clothes, thus creating a sort of addicting shopping mechanism, where you could go shopping with more and more frequency.

Key TakeawaysIn the early 2000s, the fashion industry has been taken by storm by fast fashion players who mastered shorter cycles for manufacturing clothes by fast following fashion trends. Fast fashion players also mastered the process of cheap manufacturing of these clothes. They also distributed quickly across the iconic store located in the various major cities, drawing in millions of potential consumers each day. From Fast Fashion To Real-Time RetailAs the 2010s brought many more people online across the world, the fast fashion phenomenon became even more rapid, thus giving rise to the ultra-fast fashion first, then to real-time retail.

Fash fashion has been a phenomenon that became popular in the late 1990s, early 2000s, as players like Zara and H&M took over the fashion industry by leveraging on shorter and shorter design-manufacturing-distribution cycles. Reducing these cycles from months to a few weeks. With just-in-time logistics, flagship stores in iconic places in the largest cities in the world, these brands offered cheap, fashionable clothes and a wide variety of designs.

Fash fashion has been a phenomenon that became popular in the late 1990s, early 2000s, as players like Zara and H&M took over the fashion industry by leveraging on shorter and shorter design-manufacturing-distribution cycles. Reducing these cycles from months to a few weeks. With just-in-time logistics, flagship stores in iconic places in the largest cities in the world, these brands offered cheap, fashionable clothes and a wide variety of designs. Read Also: Zara, Wish, Poshmark, Etsy.

Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsThe post Fast Fashion Business Model In A Nutshell appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

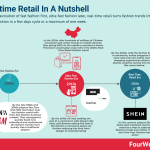

Real-time Retail: The Rising Of Real-Time Fashion

Real-time retail involves the instantaneous collection, analysis, and distribution of data to give consumers an integrated and personalized shopping experience. This represents a strong new trend, as a further evolution of fast fashion first (who turned the design into manufacturing in a few weeks), ultra-fast fashion later (which further shortened the cycle of design-manufacturing). Real-time retail turns fashion trends into clothes collection in a few days cycle or a maximum of one week.

Understanding real-time retailIn the digital era of instant gratification, consumers expect a seamless shopping experience from retailers on a variety of devices. But the preference for consumers to shop online also presents a huge opportunity for retailers who can gain a competitive advantage by meeting consumer needs in real-time.

E-commerce marketing is part of the digital marketing landscape, and beyond, where e-commerce businesses can enhance their sales, distribution, and branding through targeted campaigns toward their desired audience, convert it into loyal customers which can potentially refer the brand to others. Usually, e-commerce businesses can kick off their digital marketing strategy by mastering a single channel then expand for a more integrated digital marketing strategy.

E-commerce marketing is part of the digital marketing landscape, and beyond, where e-commerce businesses can enhance their sales, distribution, and branding through targeted campaigns toward their desired audience, convert it into loyal customers which can potentially refer the brand to others. Usually, e-commerce businesses can kick off their digital marketing strategy by mastering a single channel then expand for a more integrated digital marketing strategy.Using real-time technology in search, retailers can adjust their reach, competitiveness, and relevancy during critical times to boost conversion rates. For example, how might an air-conditioning business target search terms before a forecast heatwave? How might a fashion retailer identify the next fall trend before it comes mainstream?

The importance of real-time retail is also exemplified in delivery times. Giants such as Amazon are now making same and next-day delivery the new normal. This poses a problem for smaller, less efficient businesses that find it difficult to offer a level of service consumers now expect.

To that end, real-time retail increases efficiency in every aspect of a retail business. Practitioners of real-time retail note many processes that should be real-time or as close to real-time as possible. These include processes in areas such as supply chain management, inventory, marketing, advertising, product creation, and customer experience.

Real-time retail practicesLet’s now take a look at some of the more impactful real-time retail strategies:

Proximity marketing – in general terms, proximity marketing involves the use of streaming analytics and mobile infrastructure to locate customers in real-time and analyze their behavior. In a typical store, streaming analytics help retailers track the physical location of each customer and send them product offers when they are in a certain radius of a product or aisle. This form of promotion allows the retailer to avoid pushing out random and untargeted product offers that are unlikely to convert.Contextual recommendations – Amazon generates over a third of its total revenue through contextual recommendations based on products purchased by similar customers. Despite its effectiveness and perhaps through a lack of suitable data, some retailers have been slow to incorporate this real-time retail process. Ad optimization – in the previous section we noted the example of an air conditioning business changing its strategy to reflect periods of hot weather. Real-time analytics can help the company decide when to bid for digital ad space based on current trends, market penetration, and consumer purchasing behavior. Such analytics correlate views or clicks with user demographics and marketing budgets in real-time. In fact, real-time retail provider Experian uses streaming analytics to optimize ad placement in less than a millisecond.Personalized shopping experiences – real-time retail also makes a highly personalized shopping experience possible for consumers. Jewelry retailer Helzberg Diamonds developed an app for employees to enhance the experience of shopping for jewelry. Using the app, sales staff have real-time access to a customer’s purchase history, wish list, and contact details. The app also provides data on inventory levels and can display product information from the store catalog. Key takeaways:Real-time retail involves the instantaneous collection, analysis, and distribution of data to personalize the consumer shopping experience.Real-time retail applies to most aspects of a retail business, including marketing, distribution, advertising, inventory management, and product creation.One form of real-time retail is proximity marketing, where retailers track the physical location of customers in a store and send targeted offers. Streaming analytics data is also used to optimize advertising in response to fluctuating trends or events.Related Case Studies

Zara is a brand part of the retail empire Inditex. Zara business model, with over €18 billion in sales in 2018 (comprising Zara Home), and an integrated retail format with quick sales cycles. Zara follows an integrated retail format where customers are free to move from physical to digital experience.

Zara is a brand part of the retail empire Inditex. Zara business model, with over €18 billion in sales in 2018 (comprising Zara Home), and an integrated retail format with quick sales cycles. Zara follows an integrated retail format where customers are free to move from physical to digital experience. Wish is a mobile-first e-commerce platform in which users’ experience is based on discovery and customized product feed. Wish makes money from merchants’ fees and merchants’ advertising on the platform and logistic services. The mobile platform also leverages an asset-light business model based on a positive cash conversion cycle where users pay in advance as they order goods, and merchants are paid in weeks.

Wish is a mobile-first e-commerce platform in which users’ experience is based on discovery and customized product feed. Wish makes money from merchants’ fees and merchants’ advertising on the platform and logistic services. The mobile platform also leverages an asset-light business model based on a positive cash conversion cycle where users pay in advance as they order goods, and merchants are paid in weeks.  Poshmark is a social commerce mobile platform that combines social media capabilities to its e-commerce platform to enable transactions. It makes money with a simple model, where for each sale, Poshmark takes a 20% fee on the final price, for sales of $15 and over, and a flat rate of $2.95 for sales below that. As a mobile-first platform, its gamification elements and the tools offered to sellers are critical to the company’s growth.

Poshmark is a social commerce mobile platform that combines social media capabilities to its e-commerce platform to enable transactions. It makes money with a simple model, where for each sale, Poshmark takes a 20% fee on the final price, for sales of $15 and over, and a flat rate of $2.95 for sales below that. As a mobile-first platform, its gamification elements and the tools offered to sellers are critical to the company’s growth.  Etsy is a two-sided marketplace for unique and creative goods. As a marketplace, it makes money via transaction fees on the items sold on the platform. Etsy’s key partner is comprised of sellers providing unique listings, and a wide organic reach across several marketing channels.

Etsy is a two-sided marketplace for unique and creative goods. As a marketplace, it makes money via transaction fees on the items sold on the platform. Etsy’s key partner is comprised of sellers providing unique listings, and a wide organic reach across several marketing channels. Read Also: Shein, Wish, Poshmark, Etsy.

Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsBlockchain Business Models FrameworkThe post Real-time Retail: The Rising Of Real-Time Fashion appeared first on FourWeekMBA.