Elizabeth Lunday's Blog, page 5

June 6, 2012

So who’s this Venus chick anyway?

I’m a day late, alas, but I can’t let the week go by without noting the Transit of Venus.

Is that not what it looked like?

We tried to get all low-tech astronomical at our house. The pin-hole camera thing was a bust. My husband rigged up a lens and some cardboard, and we saw a dark smudge that we declared to be Venus but which might have been a spot on the lens. We then retired to the house to watch astronomical phenomena the way God intended, on television. The NASA channel, which I did not know until yesterday even existed, had the cutest groups of astronomers standing on top of Mauna Kea freezing their butts off but so excited they could hardly speak in complete sentences.

But of course all this talk about Venus opens up such art historical possibilities that I can’t simply let them go. There are few more popular subjects in the history of art than the Goddess of Love.

So who was Venus, anyway?

So-called “Ludovisi Throne”: main panel, Aphrodite attended by two handmaidens as she rises ouf the surf. Thasos marble, Greek artwork, ca. 460 BC (authenticity disputed).

To begin with, she was Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of Love. The Greeks considered her an old god, older than most, and this probably reflects historical fact, that the worship of a love and fertility goddess was incredibly ancient.

The stories of Aphrodite’s birth reflect both her great age and her exoticism. According to Hesiod’s Theogony, an ancient poem about the origins of the gods, the god Kronos battled with his father Uranus for control of the heavens; Kronos cut off Uranus’s genitals and threw them into the sea. (Greek myths are not for sissies.) From the sea foam from where the, er, bits landed, Aphrodite arose.

Fresco from Pompei, Casa di Venus, 1st century AD. Excavated in 1960.

For those keeping up at home, that makes Aphrodite older than Zeus, who was the son of Kronos. The family tree isn’t important: what is important is that the idea of worshipping the female force of sex, passion, and fertility is incredibly old.

The Romans appropriated all of the Greek gods, Aphrodite included. Her name in the Roman pantheon became Venus, a noun in Latin that means “sexual desire.”

Several motifs became associated with Venus, one, of course, the motif of her rising from the sea. She is also frequently depicted bathing, simply because this gave artists an opportunity to get her clothes off:

“Venus de Milo” (Aphrodite from Melos). Parian marble, ca. 130-100 BC? Found in Melos in 1820.

The Venus de Milo, for example, is believed to have been a standard depiction of Venus emerging from her bath. It’s likely this statue was originally positioned in a Roman bath house, which were central hubs of the community that combined the functions of basic hygiene, workout and worship. Hoards of tourists surrounded this statue, which is, no joke, incredibly beautiful.

What I find interesting is that this was not a work by a great master–it was a knock-off of a far more famous work called the Aphrodite of Cnidos by the great Greek sculptor Praxiteles. Praxiteles was the first to show Venus nude, and the statue was so hugely popular that people came from all over the Greek world to Cnidos (a city in what is now Turkey) to see it. The citizens of Cnidos constructed a special temple just to house the work, a circular temple that allowed people to gaze on the beauty of the goddess from a full 360 degrees. Rumor had it Praxiteles used the famous Athenian courtesan Phryne as his model, which gave the statue an added touch of scandal. In any case, the Aphrodite of Cnidos was lost centuries ago and all we have are the knock-offs. They’re pretty darn marvelous, which makes you wonder what the original looked like.

Depictions of Venus became scarce in the Middle Ages, but with the Renaissance artists threw themselves into painting her with gusto. Botticelli, of course, made her a favorite subject:

Sandro Botticelli, "The Birth of Venus," ca. 1485-86

This famous painting shows Venus emerging from the sea on her clamshell. Two wind gods, the fierce Zypherus and mild Aura, blow her ashore. Horae, goddess of the seasons, rushes foreward with a gown to clothe her. Botticelli also depicted Venus in his work Primavera, which I’ve talked about before. Renaissance Florence in the time of Botticelli was obsessed with myth, and Venus was an obvious subject.

Once Botticelli paved the way, Italian artists went to town with portrayals of Venus.

Titian, "Venus of Urbino," 1538.

This unapologetically erotic work was hugely influential and began a motif of its own, the reclining Venus. (I talked a little about it here.) It was duplicated all over the place by all kinds of people–but that’s a subject for another day.

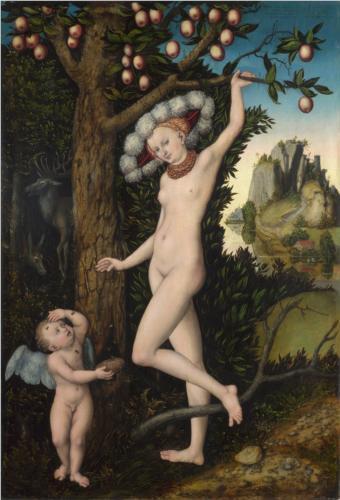

Northern European artists were less likely to paint Venus, with the prominent exception of Lucas Cranach the Elder, who seems to have painted Venus every chance he got:

Lucas Cranach the Elder, "Cupid Complaining to Venus," 1525.

Notice that Venus is naked as the day she was born, except for that marvelous hat. Cranach did this a lot, for some reason. You’ll see Venus, nude, but in a hat. It was kind of his thing.

Anyhoo, the young Cupid is holding a honeycomb, from which he presumably stole sweet, sweet honey, but now he is being stung by bees. He is complaining to his be-hatted mother, who doesn’t seem to be the least concerned. Cranach’s work can be taken as an allegory that pleasure in life always comes with pain. Notice as well that Venus is holding on to an apple tree, which reminds us of Eve and the ultimate cost of temptation. (You can find a great discussion of this work here from the Khan Academy.)

Artists over the ages returned to the image of Venus, with each era giving her the attributes and aura of the age.

Francois Boucher, "Venus and Cupid," 1769

Boucher’s Venus is all Rococo elegance, with a hairstyle that would have been entirely appropriate for the court of Marie Antoinette.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, "Venus Verticordia," 1868

Rossetti’s Venus is all flowing hair and soulful eyes, a typical Pre-Raphaelite heroine.

Alexandre Cabanel, "The Birth of Venus," 1863.

Cabanel’s Venus is luscious and erotic verging on soft-core porn. Cabanel was a hugely popular French Academic artist–he was said to be Napoleon II’s favorite painter. This was the sort of sticky-sweet art that the French Academy was churning out in the 1860s, so you can imagine with the Realists and Impressionists started showing up what a shock it must have been.

Edouard Manet, "Olympia," 1863

Yeah. Different. This isn’t technically a Venus, but scroll back up to Titian’s Venus of Urbino and you’ll see the connection immediately. Manet painting Olympia the same year Cabanel did his Venus. The two men were not friends.

The modernists took Venus in all sorts of different directions.

Odilon Redon, "The Birth of Venus," 1912

Redon’s Venus is all softness, color and vague shapes.

Amadeo Modigliani, "Venus (Standing Nude)," 1917

Modigliani takes the traditional pose of Venus (look back at Botticelli) and transforms it into the simple lines and volumes inspired by Cezanne.

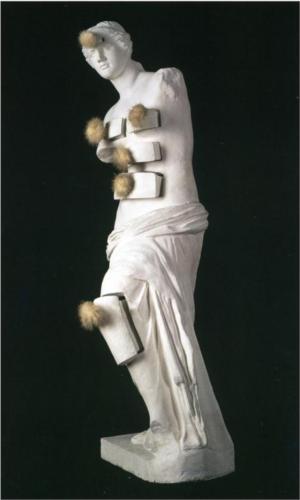

Salvador Dali, "Venus de Milo with Drawers," 1936

And then there’s Dali.

What can you say except, yep, that’s Dali.

By now, Venus has lost most of her meaning as a powerful goddess of passion. At this point, Venus is a blank slate on which artists can sketch their own notions of beauty and/or explore connections and responses to Western artistic heritage.

This is only a fraction of the Venuses out there–did I forget your favorite? Let me know in the comments. And I hope you got a chance to see the Transit, even if it really was just a smudge on the lense.

June 4, 2012

Looking at Art: The radical modernist Natalia Gonchorova

One of the joys of a museum visit is encountering art and/or artists that are completely new to you. So it was for me at MoMA when I noticed for the first time the work of Natalia Gonchorova.

One of the joys of a museum visit is encountering art and/or artists that are completely new to you. So it was for me at MoMA when I noticed for the first time the work of Natalia Gonchorova.

I’ve been meaning to study up on Gonchorova since I got back, and today is the perfect opportunity to do so since it’s her birthday. So here’s a quick overview of this fascinating woman who made significant contributions to modernism and yet is now almost forgotten.

Gonchorova was born in 1881 and studied in Moscow. She seems to have been born into the Russian artistic class–she was the great-neice of the wife of poet Alexander Pushkin. She and her partner, artist Mikhail Larionov, were at the forefront of the Russian avant-garde. They helped organize avant-garde exhibitions in Russia and exhibited with Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) German expressionism group.

Gonchorov’s early work takes inspiration from two sources: Cezanne and Russian folk culture. From Cezanne, Gonchorov developed an interest in strong, pure colors and concrete geometric construction. From folk culture she borrowed themes and motifs.

Natalia Gonchorova, "Khovorod," 1910 (Click for larger image)

Notice the strong sense of volume in the dresses of the women, combined with the simplicity of a peasant dance.

Gonchorova also used images from the Orthodox religious tradition and was inspired by motifs from religious icons.

Natalia Gonchorova, "Nativity," 1910

The Medieval simplicity here is deliberate. I like the detail of the red halos around the heads of the Virgin and the Christ Child–typical touches from icons.

The interest in traditional Russian folk culture was in the air at the time. Russia had looked to the West for culture for centuries–Peter the Great tried to “civilize” Russia by creating new cultural traditions based on those of France. Around the turn of the century, many Russia artists rejected this attitude looked East to peasant culture, dress, art and stories for inspiration. In the same period, Stravinsky drew on the same vein of cultural heritage to write The Rite of Spring.

Around 1912, Gonchorova and Larionov attended a series of lectures by the Italian Futurist artist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. They were greatly inspired by Futurism’s emphasis on modernity, motion and mechanical forces. Gonchorova’s work took on a definite Futurist style for a time:

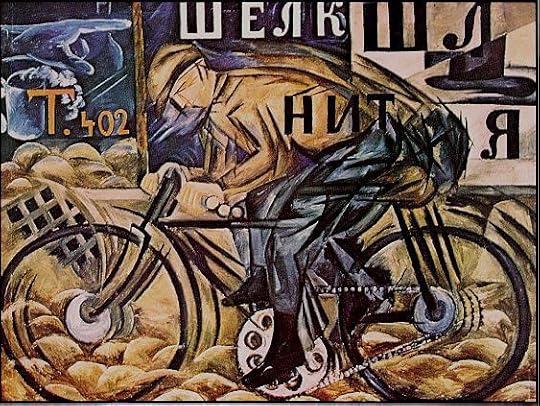

Natalia Gonchorova, "The Cyclist," 1913

The sense of movement in the wheels and the repeating lines of the body all contribute to the sense of forward momentum. It’s classic Futurism. The letters and images in the background are passing signs and advertisements glimpsed by the rider on his way.

However, Gonchorova and Larionov weren’t satisified to simply adapt Italian Futurism. They took the movement in another direction, into greater abstraction, with what they called “Rayonism.”

Natalia Gonchorova, "Green Forest," 1913

In typical modernist fashion, they wrote a manifesto for their movement, which they unveiled at the Rayonist exhibition of 1913.

The style of Rayonnist painting that we advance signifies spatial forms which are obtained arising from the intersection of the reflected rays of various objects, and forms chosen by the artist’s will. The ray is depicted provisionally on the surface by a colored line. That which is valuable for the lover of painting finds its maximum expression in a rayonnist picture. The objects that we see in life play no role here, but that which is the essence of painting itself can be shown here best of all–the combination of color, its saturation, the relation of colored masses, depth, texture.

Got that?

Basically, they were trying to depict rays of color reflecting off of objects and therefore to depict the essence of an object rather than its surface appearance.

(Incidentally, “Green Forest” is the work that I saw at MoMA and got me started down this path to begin with.)

Natalia Gonchorova, "Cats (Rayonist perception in rose, black and yellow)," 1913

So the point isn’t to depict a cat itself but the essence of a cat via reflected light. It’s a dynamic form of composition.

Rayonism made Gonchorova famous in Russia, as did her outrageous behavior. She and Larionov openly lived together, shocking traditional Russian society. Larionov was fascinated by tattoos and body art, and he often painted Gonchorov and himself all over; the two would then go parading, Gonchorova invariably topless, down busy streets.

The couple didn’t limit themselves to art. They briefly operated cabarets that were less spots for entertainment than live-action, interactive art installations heavy on Symbolism and interactive dance.

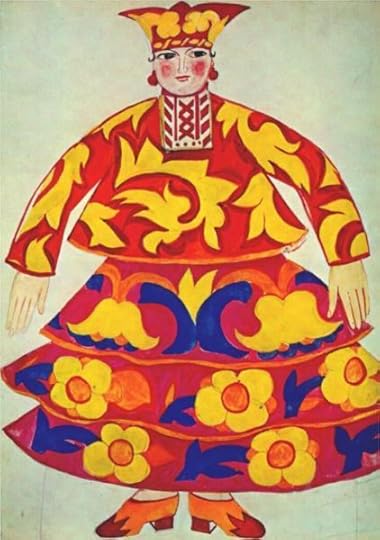

They also got involved in the Ballets Russe, the dance company run by Sergei Diaghilev. In 1914, before the war, the couple went to Paris with Diaghilev to design the sets for a production of “Le Coq d’Or.” Gonchorov also designed costumes for other Diaghilev ballets.

When the war broke in August of 1914, the pair returned to Russia for Larionov to do his military service, but they made it back to Paris in 1917. They continued to work for Diaghilev, with Gonchorov painting sets for “The Firebird.”

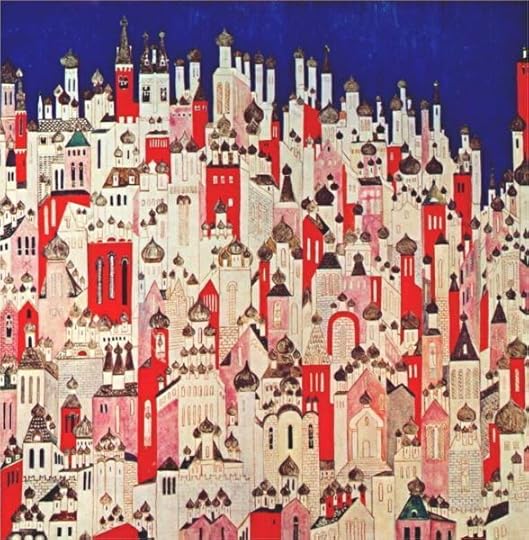

Natalia Gonchorova, Backdrop for "The Firebird," 1926

Gonchorova also taught art classes and met numerous members of the avant-garde in Paris after the war. Among her students were Gerald and Sara Murphy, the American couple who were the center of the Lost Generation artistic community and the model for the lead character’s in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night. Gonchorova introduced the Murphys to Diaghlilev and Stravinsky.

After Diaghilev’s death, Gonchorova and Larionov struggled financially. They fought to get their art back from Russia, where they had left it in 1917. They finally married toward the end of her life to ensure that they could inherit one another’s work.

Gonchorova died in Paris in 1962. She’s remained relatively unknown in the West, in part because most of her art is still in Russia and becomes available at auction only rarely. One recent sale met with unexpected success–in 2007 her painting Picking Apples was auctioned at Christie’s for $9.8 million, setting a record for any female artist.

So here’s to Natalia Gonchorova, pioneer of the avant-garde. She must have stared down endless disparaging looks. She held her own in the high pressure world of the artistic elite. It must not have been easy, but she did it with style.

May 31, 2012

Arcimboldo and the Art of the Weird

The study of art history is sometimes reduced to the study of links. Artist A transitions to Artist B which leads, apparently inevitably, to Artist C. A great deal of effort goes into getting all the movements in the right order and tracing the connections between them.

The approach works, but it has its limitations. Namely, what do you do with the artists who don’t lead anywhere? What if an artist is a stylistic dead end, wandering off in his or her own direction while the main highway of art history moves forward at a right angle?

Art history doesn’t know what to do with these anomalies, so it mostly ignores them on the grounds that they aren’t “significant.” As if all that mattered was how much influence you had on the future.

That’s a shame, because some really weird and fascinating art isn’t “significant,” but wow, is it interesting.

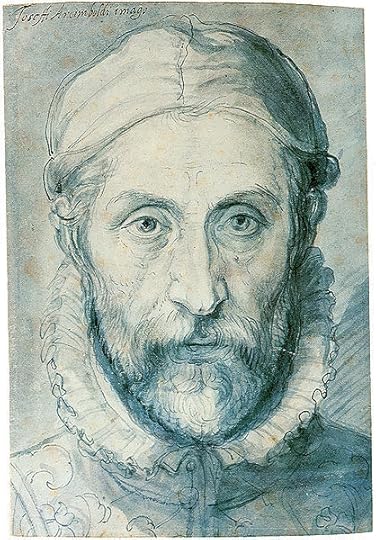

Take, for example, this esteemed gentleman. He looks mild-mannered enough. His name was Giuseppe Arcimboldo, and he had possibly the weirdest imagination this side of Salvador Dali.

Take, for example, this esteemed gentleman. He looks mild-mannered enough. His name was Giuseppe Arcimboldo, and he had possibly the weirdest imagination this side of Salvador Dali.

You wouldn’t have expected it. Archimboldo was born in 1526 in Milan, and his father was an artist. He followed a predictable Renaissance path, apprenticing, training, design cathedral windows and painting portraits. He landed a job with Maximilian II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in Vienna in the early 1560s.

He completed standard portraits and religious scenes, but his taste tended toward the capricciosa–“whimsical.”

And so it was on New Year’s Day 1569 that Archimboldo presented to Maximilian a series of paintings on the theme The Four Seasons.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Spring," 1569

It’s a guy’s head, made of flowers.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Summer," 1569

Or fruit.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Winter," 1569

Or a battered tree.

That is some seriously weird art. There’s nothing else like it in Italian art. There’s nothing like it anywhere.

And they were an immediate hit. The Hapsburg court loved them. At a 1571, Maximilian and other members of the court actually dressed up as the paintings in a festival designed by Arcimboldo. The emperor himself played Winter.

Historians note that works were more than just amusing. They also held potent symbolism about the power of the ruling family over everything, even nature. Under the Hapsburgs, the paintings hint, nature itself overflows with bounty.

Similarly, in a series on the Four Elements, the royal family exerts its influence over the fundamental forces of nature.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Water," ca. 1566

Look at those details–how the oyster shell becomes an ear. If I look at this one too long, it gives me the heebie-jeebies, imagining all those fish and turtles and squid moving around. Gah.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Fire," ca. 1566

The symbolism of “Fire” is particularly pronounced. The nose and ear are fire strikers, one of the symbols of the Habsburg family. The muskets and cannons of the body are bold representations of power. On the chest is the double-eagle seal of the Holy Roman Empire.

So Arcimboldo was a sophisticated court painter, currying to the whims and egos of his patrons. I see him in the same vein as the English playwrights such as Ben Jonson who wrote silly yet sophisticated masques that both stimulated smart courtiers and stroked their egos. Wealthy courts in time of peace have always tended toward the lavishly ridiculous. Think of the clothing of the court of Marie Antoinette.

The Hapsburg court ate it up. Maximilian’s successor, Rudolf II, even had Archimboldo paint his portrait in his unique style:

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Rudolf II as Vertumnus" (Roman god of the seasons), ca. 1590-91

There’s a lot of sly humor here–notice that the ears are actually ears of corn. The flowers and fruits are all recognizable varieties, and the interesting thing about the corn is that it was newly imported from the Americas.

Once he mastered his unique gimmick, he kept at it, his works becoming more and more detailed and clever. He did another series on the seasons:

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Autumn," 1573

Notice that the Adam’s apple is actually an apple.

He played around:

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "The Greengrocer," ca. 1590

Like this work, which has more than one way of looking at it:

He did several works of types of individuals or professions, created out of their working materials:

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "The Librarian," ca. 1570

(I wish I knew if Picasso was familiar with this work. It’s very Cubist, don’t you think?)

Arcimboldo eventually retired from court service and returned to his hometown Milan. He died there in 1593. And his works were quickly forgotten. After all, it’s not like an entire school of art grew up around the gimmick of make faces out of other objects.

And forgotten he remained until the 1930s and his rediscovery by the Surrealists. The French Surrealist magazine Minotaure reproduced his work and Alfred Barr featured him in an Museum of Modern Art exhibition titled “Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism.” Man Ray, Rene Magritte and Dali all claimed Arcimboldo as inspiration, and Dali declared him the Father of Surrealism, 300 years earlier.

Arcimboldo has a secure spot in museums, where his works hang uneasily next to super-serious Mannerist portraits and religious scenes. That we know about him at all is due to the Surrealists, who established a link with the artist and turned his dead end into a by-way.

Link or not, Arcimboldo’s work is worth a look–if for no other reason that it’s seriously weird. He’s funny, yes, but also unsettling. I think it has to do with the sense of “the uncanny”–that feeling that something is familiar and yet completely strange. I get the joke when I look at his work, but I don’t want to linger on it. Spenting too much time looking at his paintings gives me the screaming heebie-jeebies.

What do you think about Arcimboldo? Worth a serious look? Or too frivolous to bother? And what about the creepy factor? Does he weird you out, or is that just me?

May 25, 2012

Great art, greater propaganda: Art in the service of politics

A belief has taken root that all artists are rebels. Every single one of them, throughout history, has been on the side of freedom and rebellion with a wee bit of anarchy thrown in, and if you look hard enough at their art you can find signs of their radicalism.

I think the theory is nonsense. The Artist as Rebel idea has historic roots and can be clearly traced to a specific point in time with specific cultural origins. The Romantics made artists rebels. They freed artists from the constraints of ordinary morality and imbued them with all sorts of higher motives; they were prophets, pointing the way to the future. This entitled them to sleep around, wear a great deal of black and stare moodily into the distance while standing on rocky crags.

Modern artists, starting with the Impressionists, enshrined notion by rebelling against establishment art. For the last century or so, then, artists have made it their business to rebel against the establishment. For many artists of the past fifty years, rebellion is art’s entire raison d’etre.

However, if you look back before Romanticism, I think few artists fit the “rebel” mode as currently defined. Many artists, in fact, willingly served established institutions and seemed not have the least problem with it. They didn’t expose corruption or poke fun at pretentiousness; instead, they positively encouraged it. And I don’t think it was an act. I see no reason to think these artists were walking around with contemporary notions of freedom, individuality, democracy, equality, etc. in their heads. They were as much products of their ages as the institutions they supported.

Peter Paul Rubens, for example, spent most of his career in the employ of royalty and was so trusted that he conducted diplomatic missions. He seems to have handled the French queen Marie de’ Medici with enormous diplomacy, despite her notoriously cantankerous personality. She certainly commissioned to create one of the greatest ego-strokes of all time:

Peter Paul Rubens, "The Presentation of Her Portrait to Henry IV," 1622-25

This is one of a series of 24 enormous paintings on the life of Marie. They take up an entire room at the Louvre, a room that I dragged my family around while laughing hysterically. (My family is very tolerant of my art affliction.) They are, without doubt, some of the silliest paintings in the history of art.

The goal of the entire cycle is to present Marie as, quite literally, god’s gift to the King of France. In this painting, the King of France, Henri IV, is shown Marie’s portrait and falls in love immediately. The painting is shown to him by Cupid and Hymenaios, god of marriage, while the loving couple Jupiter and Juno smile down upon them. The figure in the helmet looking over Henri’s shoulder is a personification of France; oddly, France is androgynous, mostly male in appearance but with boobs.

The entire cycle is just as obnoxious. Marie was an arrogant, power-hungry woman who seized control of the throne after Henri died; she refused to let her son, Louis XIII, have any power, and he ended up fighting a civil war, exiling his own mom, and generally doing everything in power to get her out of his hair. Rubens portrays all of these events from Marie’s point of view, making her into a wise, benevolent queen who is only separated from her beloved son by petty rumor-mongers. The paintings were Marie’s attempt to buff up her reputation for posterity, since everyone in her own era knew the truth.

Skip ahead two hundred years, and Rubens has his match in Jacques-Louis David. David began producing art with a political message for the French radicals, including his famous Death of Marat. But when the Reign of Terror ended, David swore to give up politics. Ah, but then he met the magnetic Napoleon Bonaparte. Before long, he was producing remarkable paintings for the rising hero of the French:

Jacques-Louis David, "Napoleon Crossing the Alps," 1801 (Click to enlarge)

This work commemorates the general’s heroic dash across the Alps to retake Italian territory that had been seized by the Austrians. It’s magnificent, isn’t it? The rearing horse, the resolute hero, the jagged terrain. Notice the bottom left corner, where “Bonaparte” has been scratched in a rock. Barely visible are other names—Hannibal and Karolus Magnus, aka Charlemagne. Both of these heroes crossed the Alps themselves, Hannibal in attempt to conquer Rome and Charlemagne to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor. The implication is that Napoleon is going where only these magnificent figures of history have gone before.

What stamps the work as propaganda is that it bears no relationship to reality. Yes, Napoleon crossed the Alps with his army. But he didn’t lead them in full dress uniform on a white charger. Instead, he followed the bulk of the army the day after the soldiers crossed. Plus he rode on a donkey. It’s hard to look heroic on a donkey.

Napoleon commissioned five different versions of this painting to spread the message around and hired David to complete more paintings of his meteoric rise. One of the most magnificent shows Napoleon, newly crowned Emperor of the French, crowning the Empress Josephine. David would have done more but for the Empire’s unfortunate habit of neglecting to pay him. Well, that and Napoleon’s downfall.

About that downfall—propaganda gets complicated with politics get complicated. Check out this work by Francisco Goya, a contemporary of David:

Francisco Goya, "Allegory of the City of Madrid," 1810 (Click to enlarge)

The story of this painting is complicated, and I can only summarize it here. Try not to get confused. In 1808, Napoleon conquered Spain and installed his brother Joseph as king. Goya sided with the Spanish patriots in the resulting Civil War (check out his masterpiece Third of May), but a few years later Joseph seemed safe as ruler and a bankrupt Goya accepted a commission for a portrait. He actually schemed never to meet the king but copied an engraved profile in the medallion that the angels are heralding.

However, Joseph fled Madrid before an invading British army only two years later, so Goya painted over Joseph and wrote the word Constitucion in the medallion, since the Spanish were pretty darn excited about the prospect of some basic human rights. Then Joseph came back, so Goya repainted him. A few months later, he fled again, and again Goya repainted the medallion.

In 1814, the son of the Spanish king Napoleon had deposed established himself in the capital. Goya washed his hands of his troublesome painting, so King Fernando had his favorite court painter put his portrait in the medallion. But everyone hated Fernando, so in 1843, ten years after his death—and long after Goya’s death–the words Libro de la Constitucion put in the oval. By 1872, the idea of honoring the constitution was hopelessly partisan, and Dos de Mayo was inscribed instead, honoring the same invasion commemorated in Goya’s Third of May (it was a busy month.)

Did you get that?

So don’t run away with the notion that all artists were sticking it to the Man. Some of them hung out with the Man, accepted his checks and generally kow-towed to his wishes. Does that mean they were lesser artists? Or that these works are lesser creations? Not at all. They were products of their times.

May 22, 2012

Looking at Art: Mary Cassatt

It’s Mary Cassatt’s birthday today. Cassatt fascinates me–she had a stern and famously prickly personality, yet her art is so soft and comforting. This is a woman who never had children and by all accounts wasn’t that affectionate with kids, yet painted the most warm depictions of children and their mothers. She’s a case study of contradictions.

I don’t have time for a full post this morning, but I wanted to share some of my favorite Cassatt pieces, most of which are famous but one or two that aren’t as well known.

And tell me: what do you like or dislike about Cassatt? What would you like to know about her or her art? Maybe we can delve further into the art of this fascinating woman.

Cassatt and Degas were good friends, although the two strong personalities often clashed. This is a sketch by Degas in preparation of a painting of Cassatt at the Louvre, where, in fact, they first met. I include it here because in a remarkably economical way, it captures her personality. Her clothes are smart, elegant, the height of fashion—Cassatt loved fine clothes. He figure is trim—she cared about her shapely waist. She leans on an umbrella and studies the art with a discerning eye. There’s no sense of humility or reverence; she approaches the art at the Louvre as an equal, as ready to judge as to praise.

So happy birthday, Mary Cassatt. You left a remarkable legacy.

May 21, 2012

The case of the “naive” artist Henri Rousseau: who was playing whom?

Henri Rousseau, "Self Portrait of the Artist with a Lamp," 1903

Today is the birthday of one of the oddest artists to have influenced the course of art history: Henri Rousseau.

Rousseau’s nickname Le Douanier points to the oddity of his reputation: it means “the customs agent,” and points to his job as a toll collector for the Paris customs service.

Rousseau seems to have always been a dreamer who wanted his modest Parisian life to be more exciting than it really was. He played violin–enthusiastically, if not well–composed songs, and wrote plays. He also painted–entirely from his own imagination and without any instruction whatsoever. The results are predictably uneven. He never learned techniques such as modeling or perspective. His portraits are wince-inducing.

And yet his works have a unique intensity.

Henri Rousseau, "A Carnival Evening," 1886

They are striking, evocative. Look at those silhouetted trees and the way the white of the moon echoes the white of the comedia dell’arte figures below.

Rousseau would have likely died in the same obscurity in which he worked had not Pablo Picasso discovered one of his canvases around the turn of the century. The story–which may be apocryphal–goes that Picasso saw one of Rousseau’s paintings lying in a heap in a junk shop. The owner offered to sell it cheap and told Picasso, “You can paint over it!” Instead, Picasso sought out Le Douanier and befriended him.

He introduced Rousseau to his own circle of avant-garde artists and poets, and they adopted the much older man as their mascot. In November 1908, Picasso hosted a famous dinner party in honor of Rousseau with a guest list that included Georges Braque, Max Jacob, Guillaume Apollinaire, Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas and Leo Stein. Apollinaire read a poem, Braque played the accordion, and the Stein’s friend Harriet Lane Levy, then on a visit from San Francisco, shouted the UC Berkeley Oski Wow Wow spirit yell.

Henri Rousseau, "Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Surprised)," 1891. (Click for a larger image.)

Picasso and his circle promoted and encouraged Rousseau, and there’s no question that their support is why you find Rousseau’s work in the most significant museums today. But the situation has always made me uncomfortable. Here’s how Levy described it:

Everybody loved Rousseau. Everyone smiled when they spoke of his paintings, as if they were patting him on the shoulder. Not as if he were a real artist, more like a little brother who painted things in a way that made everybody tender towards him.

There’s always a note of patronage in the descriptions of Picasso’s interactions with Rousseau. To some degree, this is natural–Picasso had been hailed as a genius since he was a child, had studied at top art academies and was on his way to become the first mega-star artist. But still–why patronize an aging, paunchy, uneducated Frenchman who liked to paint jungles? There’s something malicious about all these young, beautiful, talented people plucking this man out of obscurity and “honoring” him at their parties. Apollinaire and Picasso liked to praise Rousseau’s innocence and naivete, but weren’t they taking advantage of that same innocence? “Everyone smiled when they spoke of his paintings,” Levy says. Doesn’t that make you cringe?

Henri Rousseau, "The Sleeping Gypsy," 1897. (Click for a larger image.)

And yet, and yet. Maybe Rousseau wasn’t as innocent as he liked people to think. When I studied Rousseau to write his chapter in Secret Lives of Great Artist, I learned that on at least two occasions he had been involved in criminal fraud. The first time was when he was a young man working at a law office; he stole some cash and a large quantity of stamps from his employer. He was sent to prison, then volunteered for the military to shorten his sentence. Incidentally, he liked to tell long stories about his military exploits in exotic locations; in fact, he spent four undistinguished years at decidely unexotic regional posts.

The second case took place many years later in 1907 when Rousseau was already making a name for himself as an artist. He got involved in an elaborate case of bank fraud, partnering with a bank clerk friend to open accounts under false names and passing forged bank certificates. The crime was almost immediately discovered, and Rousseau was charged and tried. At the trial, his lawyer pleaded that the naive Rousseau had been taken advantage of because of his simple, innocent nature. The jury didn’t buy it and imposed a fine and a suspended sentence.

Maybe he was innocent and had been taken advantage of. Maybe Picasso was taking advantage of him as well–perhaps not maliciously, perhaps with a combination of appreciation and the subtle cruelty of youth, talent and ego. Or maybe Rousseau knew very well what he was doing. Maybe he knew what Picasso was doing as well, and played along because, why not? It got him recognition, offers to exhibit at the best shows and invitations to fantastic parties.

I like to think it’s the latter.

May 14, 2012

The milk of human kindness! As in literal milk. Of kindness.

So by now you’ve seen the Time magazine cover, right? I don’t have to show it to you again? Because I’m not.

I was doing my best to ignore the whole kerfuffle, because I feel judged enough as a mom–not least by my own offspring (apparently I ruined my son’s life this morning through improper toast preparation .) (Don’t. Get. Me. Started.).

But then I read an article in the Washington Post Style section in which the photographer claimed that he drew on religious imagery of the Madonna and Child for inspiration.

So you want to drag art history into it, huh?

Game on.

The fact is that images of breastfeeding are common throughout art history, going back far before Christianity. And not surprisingly so, when you think about it. After all, producing milk from your body that can feed a whole human, albeit a small one, is a pretty nifty trick.

And while most of these images are of wee little babies, some are of kids more of the age on the Time cover:

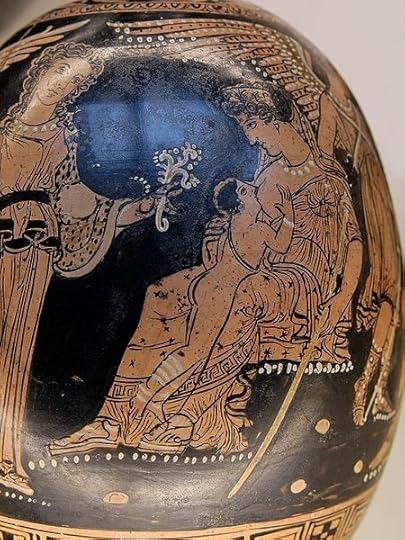

Hera suckling the baby Heracles at her breast, surrounded by Aphrodite and Eros (not visible here), Athena (on the left), Iris (on the right) and a woman, perhaps Alkmene (not visible here). Detail from an Apulian red-figure squat lekythos, ca. 360-350 BC

Again, this is not particularly surprising, since it’s likely that ancient societies breastfed their babies far longer than we typically do today in the West.

With Christianity and the rise of veneration of the Virgin Mary, breastfeeding becomes a popular and potent image. The entire mystery of the Incarnation is at work here–a human woman is nourishing the Son of God. Many of the nursing paintings and sculptures are lovely, although some artists seem to be bewildered as to what real boobs actually look like:

Paolo di Giovanni Fei, "Madonna and Child," ca. 1370s

Or where they are positioned on a woman’s body:

Hans Memling, "The Virgin nursing the Christ Child," ca. 1487-1490

In time, however, reams of doctrine were developed around the idea of the Nursing Virgin. Nursing was a representation of her charity, generosity, love, grace. The Virgin’s Milk was a potent symbol, and a powerful relic. Churches and cathedrals claimed to possess vials of the holy fluid, and the faithful came to pray before it. (Martin Luther denounced trade in the Virgin’s Milk in his Ninety-Five Theses.)

The result was paintings like this weird creation:

Pedro Machuca, "La Virgen y las ánimas del Purgatorio," 1517

That, friends, is the baby Jesus helping the Virgin sprinkle milk on the souls in Purgatory (the dark crowded figures underneath the cherubs.) The idea is that through the Virgin’s intervention, here depicted literally as milk from her breasts, the tormented will reach Heaven.

It gets weirder. In the early 1100s, the story goes, Bernard of Clairvaux particularly venerated the Virgin Mary and identified himself with the Christ Child. He prayed to the Virgin to show herself as a mother to him, and thereupon a statue of her–or maybe a vision, stories differ–appeared and doused him with her milk. You cannot make this stuff up.

Master Iam van Zwoll, "The Lactation of St. Bernard (detail)," ca. 1480-1485

In one version, she squirted him in the eye, thus curing an eye ailment from which he suffered.

Flemish School, "Lactation of Saint Bernard Flemish School," ca. 1480

In another version, the milk is the wisdom of God, which he is now ready to receive. Usually, Bernard is shown at a distance to the Virgin, but in other depictions he’s right . . . there.

Unknown Peruvian Artist, "Virgin of the Milk with Christ Child and St. Bernard Clairvaux," 1680

(Many artists over the ages painted this scene. If you’re curious, a quick search will reveal dozens.)

At the same time paintings of Bernard were achieving popularity, a similar image from another era also took hold. The story of Pero and Cimon is Roman and is found in a book of stories about ancient life written about 30 AD. In the tale, Cimon is sentenced to death by starvation, but his daughter Pero visits him in jail and secretly breastfeeds him to save his life. She is caught by the jailers, but her selfish act impresses jailers and they release Cimon. Several depictions of the scene have been discovered in Roman art.

Pero and Cimon became a hugely popular theme in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly in Catholic Europe, where the resonances with the Virgin Mary were obvious. Peter Paul Rubens painted it several times:

Peter Paul Rubens, "Roman Charity," ca. 1612

Peter Paul Rubens, "Roman Charity," ca. 1630

I don’t know why he liked it so much, but right now he’s really grossing me out.

Ahem. Caravaggio also included Pero and Cimon in The Seven Works of Mercy:

Michelangelo Merisi da Cavaggio, "The Seven Works of Mercy," ca. 1607

Here’s the detail:

(Sorry about the lousy quality–I couldn’t find better.) (The poor woman looks like she has a skin disease.)

This deeply doctrinal work was commissioned by a church and demonstrates in one panel the seven works of mercy as defined by the Catholic Church. Pero is illustrating two, visiting the imprisoned and feeding the hungry, although poor Cimon is going to have a terrible crick in his neck.

So, yeah. The imfamous Time cover has some precedent, but the meaning is completely different. In all of depictions of a woman nursing, whether a child or adult, the act is one of love, compassion, grace. I don’t question that the mother on the magazine cover nurses her child with all of those motivations, but the point of the cover is to shock and antagonize. In that photograph, nursing has become an act of aggression.

So not the same at all. But as good excuse as any to look at some weird art.

******* Special thanks to both WTFArthistory and Ugly Renaissance Babies for making my search for these paintings SO much easier! You guys rock.

May 10, 2012

Yeah, you like Shakespeare–but will you die for him?

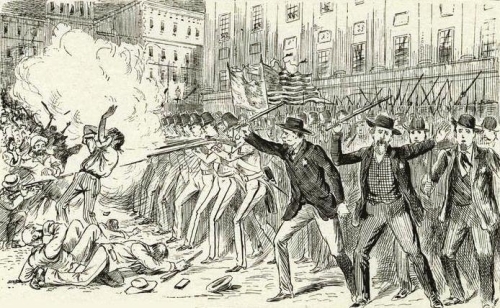

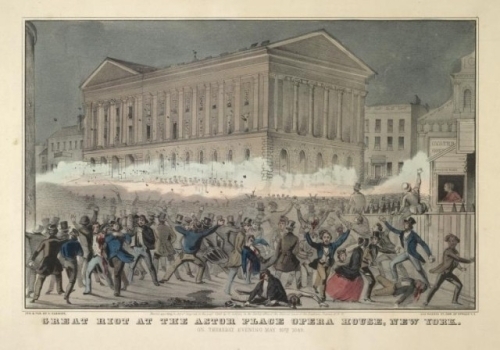

On this date in 1849, a riot rocked New York City, leaving 120 injured and at least 25 dead. The cause of the disturbance?

Different interpretations of Macbeth.

Really.

This is the anniversary of the Astor Place Riots, possibly the strangest theater-related civic disturbance in history. Macbeth usually doesn’t generate this much controversy. Usually people don’t kill each other over Shakespeare.

Of course, the riot was about more than Shakespeare. The riots were the result of a complicated situation involving class, race, religion and immigration, but nevertheless Shakespeare was the in there all along, and the consequences for American culture were lasting.

So here’s what happened.

On May 7, signs went up all over New York announcing rival performances on the same night of Macbeth. At the Astor Place Opera House, William Charles Macready would be playing the Scottish king. At the Broadway theater, the part would be played by Edwin Forrest.

Now, Forrest and Macready were two very different types of actors who appealed to two very different kinds of audiences.

William Charles Macready as Macbeth

Macready was an Englishman of relatively upper-class origins who had earned a reputation as the greatest British actor of his generation. Macready spent most of his career in England, but he toured the United States several times to great acclaim.

Macready’s greatest fans were established residents of the East Coast, generally of English or Dutch origin. Think Mayflower descendents, old money.

Macready was set to perform at the Astor Place Opera House, which had been established as the theater of the New York upper class. The theater was far more comfortable–and therefore expensive–than competing theaters, and the goal from day one was to attract an upper-class audience. It was described as “a refined attraction which the ill-mannered would not be likely to frequent, and around which the higher classes might gather.” Astor Place enforced a dress code of evening dress and kid gloves and featured only the finest performers from Europe.

Edwin Forrest, daguerreotype by Mathew Brady

Forrest was a very different type from Macready, and he performed in very different venues. Forrest was a native of Philadelphia and was raised in humble circumstances. He made his reputation on tours through the rough West and South and had enormous success in blackface (!!!).

He was particularly associated with the Bowery Theater in New York, which catered to a lower-class population of Irish and German immigrants. These rough-and-tumble New Yorkers became his greatest fans. They didn’t show up in evening dress and kid gloves to the theater; they sat on rough benches and enjoyed melodramas, animal acts and minstrel shows.

They also LOVED Shakespeare.

This is hard for us to get our heads around. Today Shakespeare is the highest of high art. Seeing a Shakespeare play is one step removed from opera. Famous actors turn to Shakespeare to prove they’ve got the chops. Shakespeare is considered great, but hard and inaccessible.

That attitude couldn’t have been farther from that of mid-19th century America. Everyone knew Shakespeare, and everyone loved his work. Memorizing Shakespeare was a major portion of every child’s education; even grammar school kids were expected to recite Shakespeare and the Bible. Shakespeare’s play were the second-most likely book owned by an American family, behind the Bible. In hardscrabble camps in California, impoverished miners whiled away winter months reciting Shakespeare from memory and putting on plays.

Shakespeare was the ultimate popular culture.

(And it makes sense, really–Shakespeare wrote for a general audience. The audience at the Globe Theater was crammed with peasants as well as aristocrats.)

Forrest represented this populist tradition of Shakespeare productions. Macready, on the other hand, represented something new: high-class Shakespeare, targeted at an upper-class audience.

The two actors appeared in New York at a tense time. Emotions were running high between recent immigrants, mostly Irish, and upper-class Americans. The largely Protestant upper-class despised the Catholic Irish and disdained them as lazy, dirty job-stealers. Irish were pouring into the country, fleeing the Potato Famine. For their part, the immigrants hated the British, their traditional oppressors, who weren’t lifting so much as a finger to save the starving Irish. Anyone who appeared even remotely Anglophile immediately attracted their anger.

It didn’t help that Forrest and Macready had a long-standing personal feud, largely fueled by Forrest. On a previous tour, Forrest followed Macready from city to city appearing in the same plays to challenge him. Newspapers took up the fight and argued patriotically for the superiority of the native Forrest. Macready, for his part, publicly stated that Forrest lacked “taste.” This caused such uproar that at one point someone flung half the carcass of a dead sheep at Macready on stage.

On the night of May 7, Forrest supporters packed the top levels of Astor Place and halted the production by throwing rotten eggs and potatoes at the stage, hissing and shouting and tearing up seats. Macready and the rest of the cast valiantly tried to carry on, although forced to perform in pantomime since they couldn’t be heard. Macready announced the next day that he would leave for Britain immediately, but a petition by wealthy Astor Place fans persuaded him to stay, and he prepared to take the stage on May 10.

Both sides prepared for the conflict, with the mayor calling out the militia and Forrest backers handing out free tickets and posting handbills that read “SHALL AMERICANS OR ENGLISH RULE THIS CITY?” By the time the curtain rose, 10,000 people surrounded the theater. The mob began lobbing stones and setting fires. The audience inside cowered in their seats and the actors attempted to carry on over the sound of shouting from outside. Macready managed to escape from the back in disguise.

Authorities called in the troops, who fired first in the air, then point-blank into the crowd.

When it was all over, some 25 people lay dead, most of them Irish immigrants. Soldiers and police were among the seriously wounded. It took two days to get the city back under control.

The riot had long term results. It marked the high point for Shakespeare in popular culture. Forrest’s reputation was badly damaged; he was seen as instigating the bloodshed and was condemned across the country. His declining fame tarred the entire field of popular theater with which he was represented.

Over time, Shakespeare fell out of favor in popular entertainment. The causes for this shift are complicated; the reverence with which the Bard was held actually contributed to the decline of popular productions, as Shakespeare became seen as too important, too good to be trusted to amateurs.

I love this story, despite the violence, because of all it tells us about a past we’ve forgotten. How many Americans know that the Irish were once a despised immigrant community, hated without cause and deeply discriminated against? How many of us remember a time when being Catholic was considered alien and distrustful? How many know 25 people died–in part at least–because of Shakespeare?

So remember the Astor Place Riots, and remember this as well: if you think America is weird and mixed-up today, study American history. We’ve been weird and mixed-up from day one.

May 8, 2012

Art, science, history, politics, and the magic of a portrait

When you visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art and walk up that magnificent staircase to the second floor, one of the first paintings that greets you upon entering the European paintings collection is this magnificent work:

Jacques-Louis David, "Portrait of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier and His Wife," 1788 (Click to see at larger size.)

I love this painting, and not just for the artistry. No, this is a work I love for the story. And what a story. This painting combines art, science, history and politics in a fascinating mix.

Depicted here are Antoine Lavoisier and his wife and collaborator Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze. Lavoisier is known as the Father of Chemistry–he gets the credit for making chemistry a science and hauling it out of the mists of alchemy. He pioneered a rigorous, measurement-based approach that revealed amazing and foundational insights.

Line engraving by Louis Jean Desire Delaistre, after a design by Julien Leopold Boilly

One of his most important areas of research was in the science of burning things. Scientists had figured out the basic fact that some things burn (e.g., wood) and others don’t (stone.) To account for this, they developed the theory of phlogiston. Phlogiston was believed to be an element present in some substances but not in others. Wood was believed to be high in phlogiston and therefore burns readily; stone has no phlogiston and so doesn’t burn. Since you can no longer burn wood once it has been reduced to ash, the wood has been “dephlogisticated”–that is, all the phlogiston has been removed.

Phlogiston was a pretty nifty theory that explained a lot of things, but of course it was absolute nonsense. The first holes were poked in phlogiston when it was discovered that many substances when burned increase in weight, which wouldn’t make sense if they were losing phlogiston. Aha, said the phlogiston-ites, phlogiston must have negative weight! At this point, everyone else tilted their heads to one side and asked, “What the heck is negative weight?”

Lavoisier settled the question through a series of painstaking experiments where he burned substances in closed containers. He would carefully weigh all of the substances first, including the air, and then weigh them again after burning. And every time, the weight before and after was exactly the same. In fact, weight is neither gained nor lost in burning; gases are either absorbed or released, but the net amount of stuff remains the same. There’s no such thing as negative weight, and no phlogiston is being added or removed from anything.

So in a single maneuver, Lavoisier both disproved the phlogiston theory and established the Law of Conservation of Mass, a fundamental basis of science that says mass can neither be created nor destroyed.

Lavoisier’s experiments were time-consuming and meticulous and would not have been possible without the assistance of his wife Marie-Anne. Lavoisier married Marie-Anne when he was 28 and she 13, which is creepy but was typical. She became intensely interested in her husband’s work and in time became his lab assistant, taking detailed notes while he worked. They were by all accounts a supremely happy couple, spending hours together in the lab.

The painting captures the warmth of their relationship with her gentle hand on his shoulder and his inquiring look up at her. They are surrounded by their scientific equipment, which the painter, David, captures exquisitely. Look at the delicate curve of the glass bottle by Lavoisier’s feet and the reflection off the brass instruments on the table. I’ll note that the table appears to be covered with a red velvet cloth, which I have to question. Surely even French aristocrats didn’t conduct scientific experiments on red velvet.

Because in between all this scientific discovery, Lavoisier was a full-fledged member of the French elite. He wasn’t from the hereditary aristocracy and certainly didn’t have a title, but his family were wealthy bourgeois on their way up. Lavoisier significantly increase his wealth and status through intelligence, hard work and smart investments. He was heavily involved and invested in both the government monopoly on gunpowder production in France and the Ferme generale, essentially an outsourcing operation that collected customs and taxes on behalf of the king. The Ferme generale was notoriously corrupt, despite efforts at reform, and those running the operation grew enormously wealthy.

[image error]

Jacques-Louis David, "Self portrait," 1794

It was during these good times that Lavoisier commissioned this portrait by David. Selecting David was a bold move–the couple could have chosen a much more conventional artist. David was on his way up. His clean, rigorous style, inspired by his study of Classical sculpture and Renaissance painting, was considered cutting-edge as opposed to the frilly, soft-edged Rococo that had dominated for the last few decades.

Lavoisier’s personal politics were on the liberal side–he argued for reform and gave generously to the poor from his own pocket. But none of that mattered to those who saw him as a member of the hated aristocracy and one of the despised tax collectors. Lavoisier argued that he used his wealth for the advancement of science, but starving peasants weren’t particularly sympathetic. Lavoisier initially embraced the Revolution. He got directly involved in efforts to reform the old system of measurements and participated in the committee that developed the basis of the metric system.

Nevertheless, as the Revolution grew more heated and the radicals came to power, Lavoisier came under fire. He was denounced as a traitor by Maximilien Robespierre during the Reign of Terror in 1794. Within a few days, he was tried and convicted. According to a possibly apocryphal story, he appealed to the judge for his life so that he could continue his scientific experiments. The judge replied, “ “La République n’a pas besoin de savants ni de chimistes ; le cours de la justice ne peut être suspendu.”–“The Republic needs neither scientists nor chemists; the course of justice cannot be delayed”.

By this point, Lavoisier would have received no sympathy from David, who had become a radical himself. David allied himself with Robespierre and voted for the execution of Louis XVI. He became the Revolution’s propagandist, creating public spectacles to Liberty and making martyrs of the most rabid Revolutionaries, such as Jean-Paul Marat:

Jacques-Louis David, "The Death of Marat," 1793

Marat ran a extreme newspaper that regularly denounced those Marat perceived as counter-revolutionaries. Lavoisier had been on Marat’s list. Marat held a grudge against Lavoisier for years, ever since Lavoisier had publicly pointed out the flaws in a scientific invention of Marat’s and blocking his admission to the Academy of Science. Marat gave crucial testimony at Lavoisier’s trial and ensured his conviction. Conviction meant the guillotine.

It’s a tangled web.

Marat obviously got what was coming to him. He was assassinated by a young woman named Charlotte Corday who opposed the extremes of the Revolution. (She, of course, lost her head as well.) As for the bathtub, Marat suffered from a painful skin condition and liked to work while semi-submerged.

David nearly went to the guillotine himself, when his BFF Robespierre met his downfall at the collapse of the Reign of Terror. He was arrested, but he claimed that he had been swept up Revolutionary fervor and now saw the error of his ways. Eventually they let David go, figuring the artist was ultimately a political lightweight without any power beyond his brush.

Within a year and a half of Lavoisier’s execution, the French government regretted the decision and exonerated him. This was likely little consolation to his widow. Marie-Anne, incidentally, fought hard for her husband’s legacy and arranged for the publication of his memoirs. She lived to be 78.

Lots of people stand before this painting every year, and certainly it has power even if you don’t know its story. I wonder, however, if some of the appeal of the work for me is what I know what came after. This is a snapshot of the good times for the Lavoisiers, when they were safe and productive and rich. In 1788, they could have no idea what the next few years would bring. They couldn’t know the artist working before them would denounce them. They couldn’t know all would be lost.

Antoine Lavoisier was executed on this day, May 8, in 1794. When you walk up that long staircase at the Met and catch a glimpse of this painting, remember him and the complicated interweavings of art, science and history this painting represents.

May 3, 2012

Five things I learned at the museum

You’ve just got to see art in person.

I wasn’t going to tell my Toulouse-Lautrec story, because I was going to focus on my recent insights, but what the heck, I’m telling my Toulouse-Lautrec story. Back in the day, by which I mean the mid-90s, I was working for an engineering firm, which sent me to Chicago for a conference. I had one afternoon to myself–just a few hours–and I escape the conference hotel for the Art Institute of Chicago.

I was bebopping along, when I walked into a gallery was struck to stone by a painting–this one:

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, "At the Moulin Rouge," ca. 1892/95

Now, I had studied this painting in college. I remembered it well. I remember the discussion of the setting, the people, the overall vibe. And I remember thinking that this was the ugliest painting it had been my misfortune to study. Just look at that woman with the green face. The professor told us how the green light was cast by the gas lamps used in theaters at the time, and I dutifully noted it down, but the work did nothing for me. In fact, it actively repulsed me.

Even now, looking at it on the screen, I feel . . . bleh.

Oh, but that’s not the reality of this painting. This painting has nothing to do with reproductions. In person, in real life with with real light and real color, this painting is . . . transfixing.

That woman’s face in garish green? That is exactly what her face should look it. What is wrong in reproduction is utterly and completely right in reality. You can almost smell the alcohol and hear the dance music. It is a remarkable painting.

And I would never have known that if I hadn’t seen it in the flesh.

Most revelations aren’t as stark as my Toulouse-Lautrec moment. But nevertheless, every time I see paintings and sculptures in person, I see things that I never noticed in reproductions. And here are some things I never would have known without my trips to the Met and MoMA last weekend.

1. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is super big and super bright.

I’ve written here about Les Demoiselles before. It’s a transformational work in the life of Picasso and the history of art. But I had never seen it in person before. Two things immediately struck me.

First, it’s HUGE.

Brauner? Don’t know a thing about him. I was captivated by this painting. I hung out in front of it for a long, long time. The color is much brighter and more pure in person, and it combines totemic power with what I can only call whimsical charm.

I learned more, of course. I had a sort of moment in front of Picasso’s La Coiffure where I simply could not put together in my head how he painted a skirt of a woman with how that skirt looked. That combination of lines and colors should not have added up to a skirt, except they did. That’s why they call him a genius, I guess.

So go to a museum. It doesn’t have to be MoMA or the Met or anywhere huge. You’ll have the same sorts of revelations at any exhibition. And let me know: what have you learned at museums? What works surprised you? What was your Toulouse-Lautrec moment?