Elizabeth Lunday's Blog, page 7

March 8, 2012

Genius, misery, and Mozart: Allegri’s “Miserere”

This blog may give the impression that I’ve been goofing off. Playing around. Neglecting my responsibilities. Failing my sacred posting duty.

Aha! But it is not so. Or, not exactly. I got all inspired and stuff and decided that what the blog really needed was some fancy-pants video. Some of that multimedia all the kids are talking about these days. And what better topic to multimedia-ize than Michelangelo, on the occasion of his birthday.

Yeah. That was Tuesday. I kinda unestimated–make that VASTLY underestimated–how hard this would be and how long it would take.

As of this instant, I have 2 minutes and 11 seconds out of what I estimate will end up about five minutes of video, and it’s doing odd things here and there that will no doubt require a great deal of head-scratching and Google searching. I’m getting there, but I’m thinking that next Tuesday is a more reliable estimate at this point, considering the other stuff I have going on.

But I wouldn’t want to leave you entirely stranded, so I’m recycling again from one of my books–Secret Lives of Great Composers this time.

Writing about Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel got me thinking about another work associated with the chapel, Gregorio Allegri’s Miserere. This is a gorgeous choral work that has a great story.

Back in 1638, shortly after Allegri composed his Miserere–a setting of Psalm 51 intended for the Good Friday service of Tenebrae–Vatican authorities decided the choral work was so magnificent that all reproduction of the score was forbidden, as was performance of the work outside the Sistine Chapel. Any musician who broke the ban faced excommunication, the ultimate punishment of the church.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, ca. 1780

That didn’t stop the adolescent Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. While on tour with his father at age twelve, one of the duo’s first visits was to the Sistine Chapel, where they heard the work performed. Mozart immediately returned to his inn and wrote down the score from memory. A few days later, Mozart had a private concert for the pope, during which he played his version of Allegri’s Miserere. Fortunately for the Catholic Mozarts, the pope was more impressed than annoyed by the precocious musical feat and praised rather than punished the genius child.

The whole stunt reeks of Leopold Mozart, the composer’s father, who loved nothing more than showing off his child’s talent. Leopold probably cooked up the whole thing and likely helped with the transcription.

Even though Miserere dates from nearly a century after Michelangelo’s Last Judgment–the focus of my putative video–I decided to go ahead and use it as intro music. It’s just so gorgeous.

I poked around YouTube and found several versions. This one is somewhat shortened, but it’s stunning. Enjoy–and check back in a few days for my Michelangelo video, if I don’t give up and attack my own computer with my newly purchased microphone first!

Genius, misery, and Mozart: Allegri's "Miserere"

This blog may give the impression that I've been goofing off. Playing around. Neglecting my responsibilities. Failing my sacred posting duty.

Aha! But it is not so. Or, not exactly. I got all inspired and stuff and decided that what the blog really needed was some fancy-pants video. Some of that multimedia all the kids are talking about these days. And what better topic to multimedia-ize than Michelangelo, on the occasion of his birthday.

Yeah. That was Tuesday. I kinda unestimated–make that VASTLY underestimated–how hard this would be and how long it would take.

As of this instant, I have 2 minutes and 11 seconds out of what I estimate will end up about five minutes of video, and it's doing odd things here and there that will no doubt require a great deal of head-scratching and Google searching. I'm getting there, but I'm thinking that next Tuesday is a more reliable estimate at this point, considering the other stuff I have going on.

But I wouldn't want to leave you entirely stranded, so I'm recycling again from one of my books–Secret Lives of Great Composers this time.

Writing about Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel got me thinking about another work associated with the chapel, Gregorio Allegri's Miserere. This is a gorgeous choral work that has a great story.

Back in 1638, shortly after Allegri composed his Miserere–a setting of Psalm 51 intended for the Good Friday service of Tenebrae–Vatican authorities decided the choral work was so magnificent that all reproduction of the score was forbidden, as was performance of the work outside the Sistine Chapel. Any musician who broke the ban faced excommunication, the ultimate punishment of the church.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, ca. 1780

That didn't stop the adolescent Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. While on tour with his father at age twelve, one of the duo's first visits was to the Sistine Chapel, where they heard the work performed. Mozart immediately returned to his inn and wrote down the score from memory. A few days later, Mozart had a private concert for the pope, during which he played his version of Allegri's Miserere. Fortunately for the Catholic Mozarts, the pope was more impressed than annoyed by the precocious musical feat and praised rather than punished the genius child.

The whole stunt reeks of Leopold Mozart, the composer's father, who loved nothing more than showing off his child's talent. Leopold probably cooked up the whole thing and likely helped with the transcription.

Even though Miserere dates from nearly a century after Michelangelo's Last Judgment–the focus of my putative video–I decided to go ahead and use it as intro music. It's just so gorgeous.

I poked around YouTube and found several versions. This one is somewhat shortened, but it's stunning. Enjoy–and check back in a few days for my Michelangelo video, if I don't give up and attack my own computer with my newly purchased microphone first!

March 1, 2012

Looking at Art: Sandro Botticelli’s “Primavera”

Apparently we’re not going to have winter in North Texas. It’s now March, and while there’s still a chance we could get one more cold blast, nature apparently doesn’t believe it. Daffodils are in full bloom, my irises are budding, and the Bradford Pear Tree in the front yard is almost done flowering and most of the leaves are out.

It is, officially or not, spring.

I noticed that today was the birthday of Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) (or at least his proposed birthday according to some scholars, record-keeping in Renaissance Florence not always being up to contemporary standards), and that info combined with the blooming and spring-ing all around me prompted a pretty obvious choice for today: Botticelli’s Primavera:

[image error]

Sandro Botticelli, "Primavera," ca. 1482 (Click image for a larger version.)

Isn’t it luscious?

And isn’t it also mysterious? What the heck is going on?

The short answer is that we don’t know. The long answer is that we sort of know about some of it but that the details are pretty fuzzy.

Understanding the painting requires at least a quick look at the environment in which it was created. Botticelli was a favorite of the Medici family, the incredibly wealthy and powerful Florentine family that more or less invented international banking while subsidizing the Renaissance. The artist formed part of the circle of poets, sculptors, and scholars that made up the Medici court. Head of the family Lorenzo the Magnificent even wrote a short poem mocking Botticelli’s habit of indulging himself at the Medici dinner table; he makes a play on Botticelli’s name, which translates to “little bottle,” noting that the artist arrives a little bottle but leaves a big one. Botticelli paid tribute to the Medicis in his work and generally devoted himself to their interests.

The Medici court whiled away the hours reading ancient Roman poetry and debating Greek philosophy; scholars such as Marsilio Ficino and Agnolo Poliziano were particularly interested in the writings of Plato and invented a sort of Neoplatonism that emphasized the role of beauty in the world. It’s believed that Primavera was commissioned by a member of the Medici family–perhaps even Lorenzo–to represent the ideas floating around Florence. It might even illustrate a poem by Poliziano, although the poem itself has been lost.

At the center of the painting, positioned slightly behind the other figures (although Botticelli largely ignored linear perspective in the work) is Venus, the goddess of Love:

Sandro Botticelli, Detail from "Primavera," ca. 1482

Notice how the grove of orange trees forms an archway over and behind her and how the foliage is shaped to create a sort of halo around her. These elements serve to emphasize her centrality in the painting. They also set up an interesting parallel that would have been readily apparent to the audience of the day: Renaissance art habitually positioned the Virgin Mary with an archway or apse. Odd as it might seem to us, Venus and the Madonna shared a great deal of symbolism–they are both associated with love, beauty, and birth.

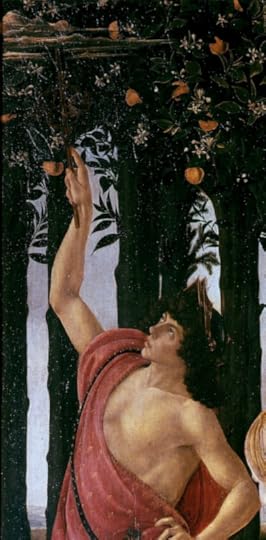

Above Venus is her son, Cupid:

Sandro Botticelli, Detail from "Primavera," ca. 1482

He is blindfolded and aims his arrows toward the Graces.

The Graces stand to the left of Venus:

Sandro Botticelli, Detail from "Primavera," ca. 1482

The Graces traditionally were part of the retinue of Venus. They were the goddesses of charm, beauty, nature, creativity and fertility. They were often shown naked, although here Botticelli has given them diaphanous, transparent draperies. Each have Botticelli’s trademark elegance and beauty, along with his characteristic bonelessness. The way they stand is improbable–they seem almost to be floating. But look at their magnificent hair, the flow of their garments, and their hands:

Gorgeous.

To the left of the Graces is Mars, the God of War:

Sandro Botticelli, Detail from "Primavera," ca. 1482

We know this is Mars from his sword and helmet, but note that the sword is sheathed. Violence has no place in the sacred grove of Venus. We can make a case for Mars’ attendance; he and Venus were traditionally lovers, and Botticelli even did a painting of the two of them together around the same time. What’s not clear is what he’s doing in this painting. He’s holding a branch or wooden wand and seems to be poking at some improbable clouds edging into the grove. One theory is that he is holding back the clouds, or shooing them away, since it is always sunny in the presence of Venus. Honestly, no one knows.

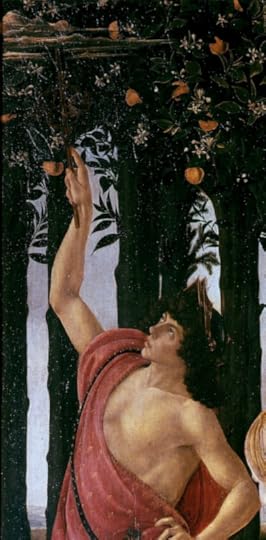

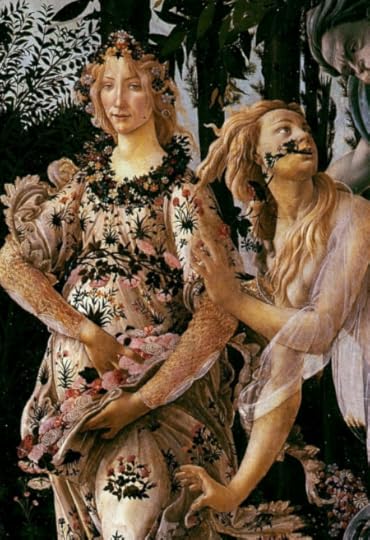

Moving to the other side of the painting, and moving from right to left we see this weird blue guy:

Sandro Botticelli, Detail from "Primavera," ca. 1482

That’s Zypherus, the west wind and the wind of March. That’s why his cheeks are all puffed out–the gods of winds are always shown that way, to indicate they blow the winds. And of course he can fly. Zypherus was often associated with Venus; he’s also seen in The Birth of Venus, rushing in from the side to lift Venus from the sea and take her to land.

He’s seizing a young woman, who, you’ll notice has vines springing from her mouth. This is Chloris, a nymph associated with flowers and spring. The story goes that Zypherus fell in love with her, chased her down and raped her. That explains her terrified expression.

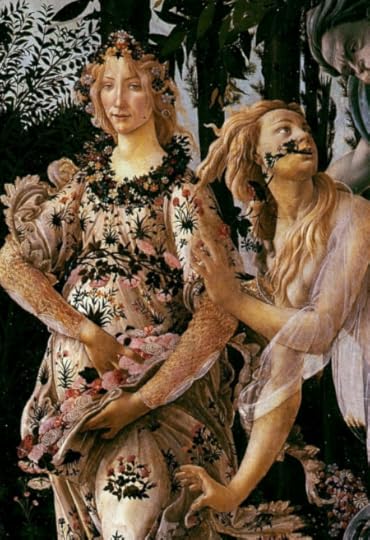

However, the myths go on to say that as apology, Zypherus then transformed Chloris into the goddess of flowers, Flora:

Sandro Botticelli, Detail from "Primavera," ca. 1482

So really the two figures are one, at different stages. The flowers emerging from Chloris’ mouth trail over to Flora, who is bedecked with flowers and tossing roses on the ground. (I don’t know why Flora’s gown has those oddly scaled sleeves. Hm.)

It would be nice to sum all of this up with a general statement about the painting as a whole. But it’s just not possible. Various scholars have come up with various theories, but none of them are entirely satisfying. I personally think we’re missing a key piece of evidence–probably a poem–that tied it all together. Without that, we can only conjecture. Clearly, the painting is about the power of love and beauty and the coming of spring. Transformation must be significant–through love (as disgusting as we see it, Zypherus’ rape would have been interpreted as an act of love), Chloris is transformed into a goddess of fertility, flowers, beauty.

With the information we have, we can’t really dissect the painting. We can only enjoy it in all its beauty and oddness. There are good discussions of the painting online; I particularly like this video from SmartHistory.

So what do you think? What does the painting mean–if not to Botticelli, then to you?

And happy spring, if it’s reached you yet–and if not, know that it soon will.

Looking at Art: Sandro Botticelli's "Primavera"

Apparently we're not going to have winter in North Texas. It's now March, and while there's still a chance we could get one more cold blast, nature apparently doesn't believe it. Daffodils are in full bloom, my irises are budding, and the Bradford Pear Tree in the front yard is almost done flowering and most of the leaves are out.

It is, officially or not, spring.

I noticed that today was the birthday of Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) (or at least his proposed birthday according to some scholars, record-keeping in Renaissance Florence not always being up to contemporary standards), and that info combined with the blooming and spring-ing all around me prompted a pretty obvious choice for today: Botticelli's Primavera:

[image error]

Sandro Botticelli, "Primavera," ca. 1482 (Click image for a larger version.)

Isn't it luscious?

And isn't it also mysterious? What the heck is going on?

The short answer is that we don't know. The long answer is that we sort of know about some of it but that the details are pretty fuzzy.

Understanding the painting requires at least a quick look at the environment in which it was created. Botticelli was a favorite of the Medici family, the incredibly wealthy and powerful Florentine family that more or less invented international banking while subsidizing the Renaissance. The artist formed part of the circle of poets, sculptors, and scholars that made up the Medici court. Head of the family Lorenzo the Magnificent even wrote a short poem mocking Botticelli's habit of indulging himself at the Medici dinner table; he makes a play on Botticelli's name, which translates to "little bottle," noting that the artist arrives a little bottle but leaves a big one. Botticelli paid tribute to the Medicis in his work and generally devoted himself to their interests.

The Medici court whiled away the hours reading ancient Roman poetry and debating Greek philosophy; scholars such as Marsilio Ficino and Agnolo Poliziano were particularly interested in the writings of Plato and invented a sort of Neoplatonism that emphasized the role of beauty in the world. It's believed that Primavera was commissioned by a member of the Medici family–perhaps even Lorenzo–to represent the ideas floating around Florence. It might even illustrate a poem by Poliziano, although the poem itself has been lost.

At the center of the painting, positioned slightly behind the other figures (although Botticelli largely ignored linear perspective in the work) is Venus, the goddess of Love:

Sandro Botticelli, Detail from "Primavera," ca. 1482

Notice how the grove of orange trees forms an archway over and behind her and how the foliage is shaped to create a sort of halo around her. These elements serve to emphasize her centrality in the painting. They also set up an interesting parallel that would have been readily apparent to the audience of the day: Renaissance art habitually positioned the Virgin Mary with an archway or apse. Odd as it might seem to us, Venus and the Madonna shared a great deal of symbolism–they are both associated with love, beauty, and birth.

Above Venus is her son, Cupid:

Sandro Botticelli, Detail from "Primavera," ca. 1482

He is blindfolded and aims his arrows toward the Graces.

The Graces stand to the left of Venus:

Sandro Botticelli, Detail from "Primavera," ca. 1482

The Graces traditionally were part of the retinue of Venus. They were the goddesses of charm, beauty, nature, creativity and fertility. They were often shown naked, although here Botticelli has given them diaphanous, transparent draperies. Each have Botticelli's trademark elegance and beauty, along with his characteristic bonelessness. The way they stand is improbable–they seem almost to be floating. But look at their magnificent hair, the flow of their garments, and their hands:

Gorgeous.

To the left of the Graces is Mars, the God of War:

Sandro Botticelli, Detail from "Primavera," ca. 1482

We know this is Mars from his sword and helmet, but note that the sword is sheathed. Violence has no place in the sacred grove of Venus. We can make a case for Mars' attendance; he and Venus were traditionally lovers, and Botticelli even did a painting of the two of them together around the same time. What's not clear is what he's doing in this painting. He's holding a branch or wooden wand and seems to be poking at some improbable clouds edging into the grove. One theory is that he is holding back the clouds, or shooing them away, since it is always sunny in the presence of Venus. Honestly, no one knows.

Moving to the other side of the painting, and moving from right to left we see this weird blue guy:

Sandro Botticelli, Detail from "Primavera," ca. 1482

That's Zypherus, the west wind and the wind of March. That's why his cheeks are all puffed out–the gods of winds are always shown that way, to indicate they blow the winds. And of course he can fly. Zypherus was often associated with Venus; he's also seen in The Birth of Venus, rushing in from the side to lift Venus from the sea and take her to land.

He's seizing a young woman, who, you'll notice has vines springing from her mouth. This is Chloris, a nymph associated with flowers and spring. The story goes that Zypherus fell in love with her, chased her down and raped her. That explains her terrified expression.

However, the myths go on to say that as apology, Zypherus then transformed Chloris into the goddess of flowers, Flora:

Sandro Botticelli, Detail from "Primavera," ca. 1482

So really the two figures are one, at different stages. The flowers emerging from Chloris' mouth trail over to Flora, who is bedecked with flowers and tossing roses on the ground. (I don't know why Flora's gown has those oddly scaled sleeves. Hm.)

It would be nice to sum all of this up with a general statement about the painting as a whole. But it's just not possible. Various scholars have come up with various theories, but none of them are entirely satisfying. I personally think we're missing a key piece of evidence–probably a poem–that tied it all together. Without that, we can only conjecture. Clearly, the painting is about the power of love and beauty and the coming of spring. Transformation must be significant–through love (as disgusting as we see it, Zypherus' rape would have been interpreted as an act of love), Chloris is transformed into a goddess of fertility, flowers, beauty.

With the information we have, we can't really dissect the painting. We can only enjoy it in all its beauty and oddness. There are good discussions of the painting online; I particularly like this video from SmartHistory.

So what do you think? What does the painting mean–if not to Botticelli, then to you?

And happy spring, if it's reached you yet–and if not, know that it soon will.

February 23, 2012

Looking at art: Pieter Breughel’s “Netherlandish Proverbs”

So yesterday on Facebook, a friend of mine was telling a story about her kids–how they’d had a really bad week, things weren’t going well, and the youngest, the kindergartener, even had “his fish moved into next week.”

To which all her friends replied, “He had his fish moved into next week???”

It turns out the kindergarten class uses some sort of discipline system where everyone has a fish, and based on his or her behavior, one’s fish can be moved around, thus earning or losing various privileges. Having one’s fish moved into next week is bad news.

I immediately declared that moving one’s fish into next week should be a new catchphrase, describing an annoying and inconveniencing situation. Like, “Man, that two-hour staff meeting really moved my fish into next week.”`

And since I have this platform, I, of course, am promoting this new phrase and expect all of you to start using it in conversation. Someday, my friends, we are going to cause enormous confusion and bafflement for linguists. And we will not have lived in vain.

This got me thinking about other obscure proverbs, and that led me directly to a fantastic piece of wacko art: Pieter Breughel the Elder’s Netherlandish Proverbs.

Pieter Breughel the Elder, "Netherlandish Proverbs," 1559 (Click on the image to enlarge.)

Is that not weird and wonderful?

Breughel is famous for his earthy, realistic depictions of peasant life in the Renaissance-era Netherlands. His mastery of detail is remarkable–if you want a sense of what life was like in a village in Northern Europe in the 1550s, spend some time with Breughel.

He created Netherlandish Proverbs at the height of his career, and it was evidently hugely popular. His son Pieter Breughel the Younger painted some 20 copies of the work, many slightly differing in the proverbs they depict. More than 100 common sayings are illustrated.

While many of the sayings exist in English–”swimming against the tide,” for example–others are completely unknown in our language, and others are so tied to their time as to be meaningless now.

I couldn’t possibly show them all–if you’re curious, let Google work its magic–but here are some of my favorites:

“To having the world spinning on your thumb” – To have every advantage. Look at that swanky gown and be-feathered hat–he’s certainly got every advantage, doesn’t he?

“To have the roof tiled with tarts” – To be extremely wealthy. I guess if you’re super-rich, you’ve got so many tarts you don’t know what to do with them and you don’t care if your roof leaks?

“To barely reach from one loaf to another” — To have difficulty living within one’s means. The poor guy sure looks uncomfortable. Also seen here, sitting on the table, is “a hoe without a handle,” describing something useless. Underneath the table we see “To look for the hatchet” – To look for an excuse.

“To piss against the moon” – To waste time in a futile endeavor. And lest you worry this poor chap is in pain, he also represents “to have a toothache behind the ears” – to deceive or malinger. I guess claiming to have a toothache–probably a common complaint–was a good way to avoid work.

“A pillar-biter” – a religious hypocrite.

Nope, I can’t make sense of that one. But it’s marvelous.

Speaking of religious sayings:

“To tie a flaxen beard to the face of Christ” – To hide deceit under a veneer of Christian piety. Notice the person doing the tying is dressed in a monk’s brown habit and holds rosary beads. The Reformation didn’t take hold in the Netherlands for nothing.

“She could even tie the devil to a pillow” – She’s so obstinate she can accomplish anything. I love the expression on the woman’s face. It must take a lot of commitment to tie the devil to a pillow, although I’m wondering why you’d try.

“To see bears dancing” – To be starving. I guess if you get hungry enough, you start hallucinating dancing bears???

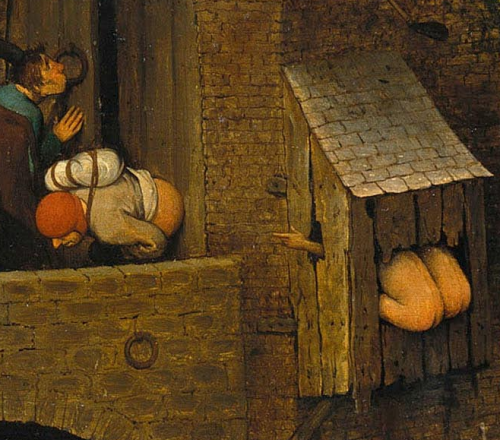

These are all great, but this has to be my favorite part of the image, if only because it emphasizes the reality that great art can be earthy, crude and marvelous, all at the same time:

“They both crap out of the same hole.” – To be in agreement. Well, they would certainly have to be, wouldn’t they?

At the same time, we see “To wipe one’s ass on a door” – To treat something lightly. The guy to the far left represents “To kiss the ring of the door” – To be obsequious.

I could go on all day. Spend some time poking around this painting–it’s endlessly rewarding. And it may add to your stock of sayings–I’m going to try to work “tying the devil to a pillow” into my day-to-day conversation.

But remember: priority goes first to “moved my fish into next week.” I expect status reports.

Looking at art: Pieter Breughel's "Netherlandish Proverbs"

So yesterday on Facebook, a friend of mine was telling a story about her kids–how they'd had a really bad week, things weren't going well, and the youngest, the kindergartener, even had "his fish moved into next week."

To which all her friends replied, "He had his fish moved into next week???"

It turns out the kindergarten class uses some sort of discipline system where everyone has a fish, and based on his or her behavior, one's fish can be moved around, thus earning or losing various privileges. Having one's fish moved into next week is bad news.

I immediately declared that moving one's fish into next week should be a new catchphrase, describing an annoying and inconveniencing situation. Like, "Man, that two-hour staff meeting really moved my fish into next week."`

And since I have this platform, I, of course, am promoting this new phrase and expect all of you to start using it in conversation. Someday, my friends, we are going to cause enormous confusion and bafflement for linguists. And we will not have lived in vain.

This got me thinking about other obscure proverbs, and that led me directly to a fantastic piece of wacko art: Pieter Breughel the Elder's Netherlandish Proverbs.

Pieter Breughel the Elder, "Netherlandish Proverbs," 1559 (Click on the image to enlarge.)

Is that not weird and wonderful?

Breughel is famous for his earthy, realistic depictions of peasant life in the Renaissance-era Netherlands. His mastery of detail is remarkable–if you want a sense of what life was like in a village in Northern Europe in the 1550s, spend some time with Breughel.

He created Netherlandish Proverbs at the height of his career, and it was evidently hugely popular. His son Pieter Breughel the Younger painted some 20 copies of the work, many slightly differing in the proverbs they depict. More than 100 common sayings are illustrated.

While many of the sayings exist in English–"swimming against the tide," for example–others are completely unknown in our language, and others are so tied to their time as to be meaningless now.

I couldn't possibly show them all–if you're curious, let Google work its magic–but here are some of my favorites:

"To having the world spinning on your thumb" – To have every advantage. Look at that swanky gown and be-feathered hat–he's certainly got every advantage, doesn't he?

"To have the roof tiled with tarts" – To be extremely wealthy. I guess if you're super-rich, you've got so many tarts you don't know what to do with them and you don't care if your roof leaks?

"To barely reach from one loaf to another" — To have difficulty living within one's means. The poor guy sure looks uncomfortable. Also seen here, sitting on the table, is "a hoe without a handle," describing something useless. Underneath the table we see "To look for the hatchet" – To look for an excuse.

"To piss against the moon" – To waste time in a futile endeavor. And lest you worry this poor chap is in pain, he also represents "to have a toothache behind the ears" – to deceive or malinger. I guess claiming to have a toothache–probably a common complaint–was a good way to avoid work.

"A pillar-biter" – a religious hypocrite.

Nope, I can't make sense of that one. But it's marvelous.

Speaking of religious sayings:

"To tie a flaxen beard to the face of Christ" – To hide deceit under a veneer of Christian piety. Notice the person doing the tying is dressed in a monk's brown habit and holds rosary beads. The Reformation didn't take hold in the Netherlands for nothing.

"She could even tie the devil to a pillow" – She's so obstinate she can accomplish anything. I love the expression on the woman's face. It must take a lot of commitment to tie the devil to a pillow, although I'm wondering why you'd try.

"To see bears dancing" – To be starving. I guess if you get hungry enough, you start hallucinating dancing bears???

These are all great, but this has to be my favorite part of the image, if only because it emphasizes the reality that great art can be earthy, crude and marvelous, all at the same time:

"They both crap out of the same hole." – To be in agreement. Well, they would certainly have to be, wouldn't they?

At the same time, we see "To wipe one's ass on a door" – To treat something lightly. The guy to the far left represents "To kiss the ring of the door" – To be obsequious.

I could go on all day. Spend some time poking around this painting–it's endlessly rewarding. And it may add to your stock of sayings–I'm going to try to work "tying the devil to a pillow" into my day-to-day conversation.

But remember: priority goes first to "moved my fish into next week." I expect status reports.

February 17, 2012

George Washington's toenails! More details of Horatio's Greenough's Neoclassical goof-up.

Friends, I have been slapped down by the Head Cold of the Damned and have spent the last two days in bed. I have the sort of raging sore throat that feels like wild badgers have been brawling in my esophagus. And, lo, I am cranky.

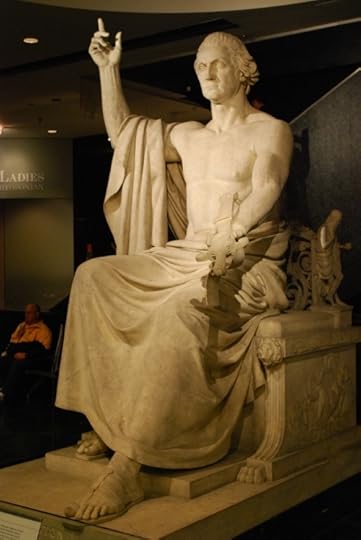

But the internet never stops, and it washed to my shores this week a fantastic page of resources all about one of our favorites works here at Chez Lunday: Horatio Greenough's statue of George Washington.

I wrote about this wacky and wonderful sculpture back in 2010, and that one post remains the most popular on my site. I can't explain it, except to guess that other people find the bare chest of the Father of Our Country just as giggle-inducing as I do.

The site is brought to you by the Beaux-Arts Atelier, a program of study in classical art and architecture sponsored by the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art. I'm going to lift images from it here, but I encourage you check out the full juicy goodness there.

The site does a fantastic job of collecting images of the Washington statue from multiple angles, including the back and sides. I hadn't appreciated the extent to which Greenough poured on the classical iconography. He was really doing everything in his power to transform Washington into a Roman Emperor channeling a Greek God.

Horatio Greenough, Detail from "George Washington," 1832

For example, Washington sits on a marble seat that resembles nothing less than a Roman sarcophagus. The seat is decorated within an inch of its life. On each side, Greenough evoked two Classical classics. On this side, it's the baby Hercules, who strangled a serpent in his crib, proving his heroism even in his infancy.

Horatio Greenough, Detail from "George Washington," 1832

On the opposite side, we see Apollo driving his chariot. Apollo was the Sun God–you can see the rays surrounding him–and he daily drove the sun across the sky. There are no better images of strength, power and heroism than Hercules and Apollo.

Here's more of the chair, this time from the back:

Horatio Greenough, Detail from "George Washington," 1832

The two figures on the side are interesting.

On the left we have:

Christopher Columbus, holding a globe. I wouldn't have known this one unless I had read it. I don't usually picture Columbus in a toga, but then I don't picture Washington in one either. Guess it wouldn't have made since to gussy him up in Renaissance garb alongside the half-nude Washington.

On the right we see:

A Native American! Didn't see that one coming. The idea was to situate Washington in between the Old and the New Worlds, a mediator joining the two.

The Beaux-Arts site also has some great examples of where Greenough got his inspiration, including Roman depictions of Zeus:

Jupiter, ca. 1st century AD, with 19th century additions

As well as Roman portrayals of emperors as gods:

The Emperor Augustus as Jupiter, 1st century A.D.

Greenough adopted all of these Roman idealizations and icons to the service of Washington, meaning only the highest respect. He wanted to portray the United States as a new Rome, a better Rome, dedicated to freedom and governed by a new Augustus, one who honored liberty and justice. An important detail of the sculpture is the sword, which Washington holds away from himself:

Greenough wants to emphasize that Washington gave up the sword after battle–that after successfully leading his people, he returned to private life. He did this twice, first as a general and then as president, when he could have instead held onto power and continued to rule even after the Revolutionary War or his two terms as president. This is a major difference between Augustus and Washington, since Augustus made himself Emperor for life.

But for all of its nobility and high ideals, the fact remains that the sculpture is, alas, ridiculous. A bare-chested Augustus is one thing–presumably his society was accustomed to seeing him that way. A bare-chested Washington? Absurd!

Not to mention that Washington himself would have been affronted at the thought of deifying himself. He was at pains to present himself as Mr. President, even when those around suggested terms such as "Your Excellency."

At the end of the day, it is this image that captures all that is off-key about Greenough's Washington:

Those are George Washington's toes. In sandals. And that's just wrong.

February 14, 2012

Looking at Art: Bronzino's "Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time"

Happy Valentine's Day! Earlier while drive down a not-very-classy street near my house, a guy was selling Valentine's gift baskets out of the back of a truck. Because nothing says "I love you" like a gift basket bought out of the back of a truck in front of a grungy strip mall.

In honor of the day, I thought we'd take a look at a love-themed work of art, one that features the hero of the day, Cupid himself. Although this painting, alas, has a sting in its tail–both figuratively and literally.

I recent happened upon Prezi, a relatively new online presentation program, and I thought it would be a fun way to do my posts every now and then. It allows you to zoom in and out on text and images, and isn't that how we really look at art, focusing on a detail and then stepping back to see the whole? I don't know how often I'll try this–it took umpteen times as long as a regular post, but it was fun, and seriously, I could tweak this thing forever. Let me know if you have any trouble viewing it and if you like or dislike the approach.

So here goes–Bronzino's "Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time." (FYI, click on the arrow button. Once the file loads, you can move forward back with the arrows. For a better look, click on "More" and then "Fullscreen."

.prezi-player { width: 550px; } .prezi-player-links { text-align: center; }

February 8, 2012

Flinging a pot of paint in the public's face: On the life of John Ruskin

John Ruskin

Art criticism is a career that generally leads to prompt obscurity–it's the rare critic indeed who is remembered after his or her death, and usually only then for passing misguided judgment on art later deemed hugely significant.

John Ruskin is the rare exception–an art critic remembered for his contributions to interpretations of art, his promotion of artists still considered masters and his overall influence on the culture. Ruskin, born on this day in 1819, shaped the course of art in 19th-century Britain more than any other single figure.

And even better, for our entertainment, he embroiled himself in several scandals along the way.

Ruskin was one of those wealthy, well-connected Englishmen of his era who spent his childhood reading Shakespeare and touring Europe with his indulgent parents. He began writing art criticism, not out of any need or desire for a career but simply to express his thoughts. These thoughts centered largely on the role of nature in art.

European art at that period worshipped at the altar of the Renaissance. Michelangelo and Raphael had achieved the pinnacle of art and everyone else was just mucking about in their wake. That meant when nature and the Renaissance conflicted, the Renaissance won. Dante Gabriel Rossetti (on whom more later) once got in trouble in art school for painting grass a vibrant green, which, as you may have noticed, it usually is. He was sternly reprimanded, since in Old Master works grass was a muddy shade of brown. This was actually the consequence of truly filthy paintings and the oxidation of green paint, but the fact remained: if Raphael's grass was brown, so much be yours.

Artists were beginning to rebel against this sort of rote acceptance of Academic truisms, and Ruskin supported them wholeheartedly. He celebrated the work of these rebels and argued that they were actually better than the Old Masters because they captured the truth in nature instead of following pictorial convention. The job of the artist, Ruskin argued, was to observe the reality of nature and recreate the truth of that reality, ignoring all the conventions of composition and color theory.

Ruskin's case in point was the Englishman J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), who over the years transformed from a fairly convention landscape painter to a stylistic innovator who captured atmosphere like no one else.

J.M.W. Turner, "Juliet and her Nurse," 1836

After an 1836 exhibition at the Royal Academy, one Reverend John Eagles attacked Turner and particularly the above work by Turner as "a composition as from different parts of Venice, thrown higgledy-piggledy together, streaked blue and pink and thrown into a flour tub." An outraged Ruskin rushed to Turner's defense, although at the request of the reticent Turner, his response to Eagles didn't appear in print until after Ruskin's death. However, the incident prompted Ruskin to begin writing about art in general and Turner in particular, and before long he was recognized as a significant critical voice.

As well as championing Turner, Ruskin also became a prominent supporter of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (P.R.B.) and its followers. Founded in 1848 by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, the group sought to cast off the conventions of art that they believed dated from the Renaissance, hence the time of Raphael, hence the name "Pre-Raphaelite." (They didn't actually have a beef with Raphael, just what his name at that time stood for: stodgy, narrow-minded, formulaic art.)

Ruskin began defending the Pre-Raphaelites in 1851, lauding their attention to nature. The P.R.B. had a dedication to realism unmatched by others of their era, sometimes going to extreme ends. Take for example this work by Millais:

John Everett Millais, "Ophelia," 1852

Millais hired the model Elizabeth Siddal (who later married Rossetti) to pose for the work, but to capture the details of the half-submerged maiden he insisted she lie fully dressed for hours in a full bathtub. In chilly London, this was an unpleasant chore, so Millais lit a lamp and placed it under the tub to keep the water warm. On one occasion, however, Millais didn't notice the lamp had gone out, and Siddal lay for several hours in increasingly cold water. She ended up coming down with a nasty cold that turned into pneumonia.

Another Millais is this lovely work, which I've seen many times at the Kimbell:

Whistler painted the work at a Thames-side pleasure garden known for its magnificent fireworks displays, and it is intended to show rockets exploding at night over the dark waters–although the title "Nocturne in Black and Gold" was intended to emphasize that the point of the work was not a story about rockets or a lesson about fireworks or anything narrative or edifying in nature. Just a musical nocturne has no meaning outside of itself, neither does the painting.

Well. Ruskin may have rejected Academic cliche, but he still believed that art should have a purpose. He wrote a review of the work in which he sniped, "[I] never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public's face."

Whistler, one might say, lost it. He had disgraceful temper at the best of times, an alarming tendency to denounce people in letters to The Times and a passion for lawsuits, so he sued Ruskin for libel. The charge was ridiculous, but neither Ruskin nor Whistler was willing to back down, so in a hugely publicized trial, the critic and the artist battled in court over the nature of art and the meaning of beauty. Whistler counted on winning the case–he was up to his eyeballs in debt–but grew increasingly frustrated as one artist friend after another begged off testifying; Ruskin, on the other hand, was able to call on old Pre-Raphaelite friends to argue on his side of the case. In the end, the jury found Ruskin guilty of libel but only awarded Whistler one farthing (a quarter of a penny) in damages. Whistler went bankrupt soon after.

Ruskin's scope was enormous. He helped shape the Arts and Crafts movement, became the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford, and wrote extensively about social equality and reform. He influenced writers such as George Eliot and Marcel Proust. He even invented the term "pathetic fallacy." His last years were tormented by mental illness, and he died, incurably insane, in 1900, but honored and esteemed by many. His reputation declined in the early 20th century, but in recent years his significance has been recognized and his writing rediscovered.

Happy Birthday, John Ruskin. As a humble writer of the arts myself, I hope I can be half as insightful.

February 2, 2012

Star light, star bright: when art and astronomy meet

I'm reading the most wonderful book called The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science by Richard Holmes–I highly recommend it. I just finished the chapter on William Herschel, who discovered the planet Uranus, and it got me thinking about when art and astronomy mix.

Early Christian art, not surprisingly, drew upon mentions of celestial phenomena in the Bible. One of the most famous of these is the Christmas Star, believed to have guided the Three Wise Men to Bethlehem:

Giotto di Bondone, "No. 18 Scenes from the Life of Christ: 2. Adoration of the Magi" 1304-06

This is from Giotto's famous frescos, and above the simple stable we see a glowing red sphere followed by a blazing trail. It's been proposed that Giotto was inspired by Halley's Comet, which had appeared only a few years before, in 1301.

Other Biblical stars do more unsettling things than point the way to a miraculous birth, as in this painting:

Hans Memling, St John Altarpiece (right wing), 1474-79

This altarpiece depicts the vision of St. John the Evangelist, the vision that inspired that most weird of Biblical books, The Revelation. John on sitting writing on the isle of Patmos and sees above and beyond him his amazing vision. In the middle ground are the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse:

In the upper left we see Heaven, and in the upper right the Earth is plunged into its last battle:

Stars are falling from the heavens, with one striking rivers and streams and poisoning them. The other whacked-out details are amazing: that's a seven-headed beast in the sky, pursuing the Virgin Mary, who hovers in a protective ball of light. (For a complete explanation, read about it at the Web Gallery of Art.)

Here's weirdness of another stripe altogether:

Peter Paul Rubens, "The Birth of Milky Way," ca. 1637

Rubens is depicting a moment from Greek Mythology in the life of the hero Heracles. Zeus attempted to protect his son, born of a moral woman, by placing her in the arms of Zeus's wife Hera and having him suckle from her while she slept. That's Hera, nude, with her chariot pulled by peacocks behind her. The enthusiastic Heracles bit Hera, and she pulled back in shock. Milk spilled from her breast and across the sky, forming the Milky Way. Zeus is watching on behind the chariot, his firebolt at his feet. This has all the whackadoo elements of Rubens' mythological paintings, particularly the complete lack of gravity. I know they're supposed to be dieties, but I always find the absence of recognizable physics disturbing.

Other artists made useful yet beautiful astronomical tools:

Michael Ostendorfer, Astronomicum Caesareum, 1540

This gorgeous colored woodcut is part of an instructional manual on astronomy written by the court astronomer to Emperor Charles V. It gave details on how to use an astrolabe for calculating the altitude of stars as well as other astronomical instruments.

An entirely different artistic tradition used stars as geometric elements, to remarkable effect:

Tiles from the Alhambra, ca. 14th Century

Islamic art forbade naturalistic representation, so art instead focused on calligraphy, arabesques (curving, branching lines and forms) and geometric patterns. Star shapes were used repeatedly, in endless, fascinating variation.

Caspar David Friedrich, "Two Men Contemplating the Moon," ca. 1825–30

The book I'm reading focuses on the Romantic era and it's reaction to science and the natural world, which was one of great wonder and amazement. You can't get much more Romantic than Caspar David Friedrich, a German artist who specialized in depictions of men staring at some sublime natural scene. By placing the figures with their backs to us and the luminous moon in the center of the painting, the viewer is invited to join in the wonder at the landscape.

Probably the most famous painting of the heavens continues to have a powerful emotional effect on most audiences:

Vincent Van Gogh, "The Starry Night," 1889

The painting shows the view from Van Gogh's window over the village of St.-Remy. This was the window of the insane asylum to which he had been committed after his psychotic break a few months earlier.

The power of it is remarkable. The sense of swirling displacement induces a sort of vertigo–the same vertigo that one can feel while gazing into the stars. I remember lying on the back of car in the mountains of New Mexico looking into a clear night sky far from any city lights and feeling for an instant as if I were going to fall up into the stars. I'm not the first to have felt this way. Here's a quote from the Holmes book, from the writer Thomas Hardy:

At night . . . there is nothing to moderate the blow which the infinitely great, the stellar universe, strikes down upon the infinitely little, the mind of the beholder; and this was the case now. Having got closer to immensity than their fellow creatures, they saw at once its beauty and its frightfulness. They more and more felt the contrast between their own tiny magnitudes and those among which they had recklessly plunged, till they were oppressed with the presence of a vastness they could not cope with even as an idea, and which ung about them like a nightmare.

Beauty and frightfulness: isn't that the sense that Van Gogh's work conveys? It's stunningly beautiful, but it's also terrifying. And isn't that the sense that we get when contemplating the universe, which is so vast and awesome we cannot comprehend it.

Which brings me to the final image, not art per se but pure science:

The Hubble Ultra-Deep Field

In 2003 and 2004, scientists pointed the Hubble Space Telescope at a tiny bit of the sky, a minute little sliver of darkness in which nothing had ever been detected. Over the course of months, they opened the lens, waiting to see if anything could be seen. They got this: a view of more than 10,000 objects, most of them galaxies–not stars, but groups of stars–so old and so far away it hurts your brain to think about it. The image looks back in time approximately 13 billion years.

Beauty and frightfulness, indeed.