Elizabeth Lunday's Blog, page 4

August 1, 2013

Armory Show artist Walt Kuhn

Without Walt Kuhn (1877 – 1949), there would have been no Armory Show.

Without Walt Kuhn (1877 – 1949), there would have been no Armory Show.

Some art historians think Kuhn’s role in the whole exhibition is overplayed–and they’re right, to an extent. It’s not fair to other artists who also played critical roles to focus on Kuhn exclusively. There would have been no Armory Show without Walter Pach and Arthur Davies, either.

Kuhn attracts attention because he’s colorful, he’s intense, and he was a pack-rat. He saved every single scrap of paper he ever wrote and the whole lot was donated to the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, so if you like you can sit at your desk anywhere in the world and read his letters to his wife. Other Armory Show organizers get far less attention because their papers have vanished. Treasurer Elmer MacRae saved all of the financial records for the show (And I mean all. Those were hours squinting at microfilm that I’ll never get back.) but hardly any letters. Arthur Davies’ papers were likely destroyed. So Kuhn gets the spotlight.

But Kuhn’s role was essential. He had the original idea for an organization of progressive American artists that would hold large annual exhibitions. His determination and sheer cussedness got the new group, the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS) off the ground. And his insistence on using modern promotional techniques got the Armory Show the publicity that turned it into a media sensation.

But what about Kuhn the artist?

He’s an interesting painter, one who took a long time to come to maturity. At the time of the Armory Show, his work really wasn’t very impressive. It was . . . nice. Well executed but not particularly distinctive.

[image error]

Walt Kuhn. “Moorings.” Oil on canvas. Ca. 1906-12. Avery Galleries.

He had drawn sketches and cartoons most of his life and made his living as a cartoonist and illustrator. I’ve seen the cartoons–they’re not particularly funny, in my opinion–but then cartoons from a century ago haven’t aged well. He trained as a painter in Munich under an instructor best known for his paintings of cows and other farm animals. (Really.) His early work is generally late-Impressionist with scenes painted in bright colors with large, visible brushstrokes.

[image error]

Walt Kuhn. “Morning.” Oil on canvas. 1912. Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Florida.

This is one of the paintings he submitted to the Armory Show. You know, it’s fine. But nothing to write home about.

Exposure to the modern art of Europe electrified Kuhn. He got a heavy dose of it all at once when he went to Europe in late 1912 to select art for the show. He learned modernism the way you learn to swim by being thrown in the middle of a lake. Over the course of little more than a month, he encountered Post-Impressionism, German Expressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism, often seeing paintings in their artists’s studios with the paint still wet on the canvas.

The years immediately after the show were highly experimental for Kuhn.

[image error]

Walt Kuhn. “Bathers on a Beach.” Oil on canvas. 1915. Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection on deposit at Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza.

I particularly like this one–notice how the paint is applied in flat panes of color, without shading or shaping? Everything’s been simplified and pared down to essential forms and colors. I think best part of the canvas is the near-abstraction of the top of the painting, with the intersecting triangles of the sails and flags.

However much I like this style, apparently it didn’t satisfy Kuhn, and he continued to try other styles.

[image error]

Walt Kuhn. “Commissioners” from “Imaginary History of the West.” 1918. Oil on canvas. Gift of Vera and Brenda Kuhn. Fine Arts Center, Colorado Springs.

This is from Imaginary History of the West, a series Kuhn painted from about 1918 to 1920 that ranges widely from the colorful near-abstraction above to works that look like paleolithic cave paintings and others that resemble his cartoons. It’s an odd series–and the title is deliberate. It’s not a factual look at the real West, but an imaginary evocation based on popular culture and the Western novels Kuhn read.

Kuhn did many things other than paint in these years. He was obviously a highly skilled organizer and stage manager, and he produced several vaudeville shows that were highly praised and commercially successful. These were mostly circus-type shows, with acrobats, clowns, bands, and trick horse riders. Kuhn loved the circus and attended as often as he could, and he adored created circus acts of his own.

However, in 1925 Kuhn nearly died of a duodenal ulcer. As he recovered, he fretted that he had never found his artistic voice and resolved to paint “at least one fine piece of art” before he died.

Choosing to paint what he knew, he began to create portraits of the performers he had worked with on his stage shows. And with that, everything fell into place. As neared fifty years old, he found his artistic voice.

[image error]

Walt Kuhn. “The White Clown.” Oil on canvas. 1929. National Gallery of Art.

Kuhn’s paintings of performers have an arresting quality. They are usually backstage, and they often fix the viewer with a direct gaze. They’re not “on” in these works–they’re usually not smiling, and you know that they will present an entirely different persona under the spotlight. Here they’re tired, or keyed-up, or ready to get it over with. Their makeup is too intense up close.

[image error]

Walt Kuhn. “Girl in Uniform.” Oil on canvas. 1936. Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri.

Often Kuhn used real performers as his models. The acrobats in this work were circus performers, two of whom, the Roma Brothers, were with Ringling Brothers.

[image error]

Walt Kuhn. “Trio.” Oil on canvas. 1937. Fine Arts Center, Colorado Springs.

Other times he used his daughter or even himself as a model. This is one of his most arresting works, featuring himself:

[image error]

Walt Kuhn. “Portrait of the Artist as Clown.” Oil on canvas. 1932.

Kuhn’s later years were successful artistically but also frustrating. He didn’t fit into any of the neat categories that artists and critics used to beat up on one another. He was seen as a promoter of modernism because of the Armory Show, but his work remained representational–that is, he never turned to abstract art–and so later generations of modernists considered him dated and conservative.

Even Kuhn’s passion for the circus failed him in the end. In the mid- to late-1940s his interest turned into obsession and began attending Ringling Brothers shows every single day. Kuhn had always had a certain amount of volatility–his letters show him alternating between non-stop work fueled by passionate conviction in his own success and periods of lethargy and depression in which he believed he would never succeed at anything. At the end of his life, his mood swings became more erratic and took on a dangerous note of paranoia. He was convinced, for example, that the American Medical Association had committed some kind of horrific crimes and was determined to “expose” them. His family had him committed at Bellevue in late 1948. Kuhn died the following summer of a perforated ulcer, still at the mental institution.

Kuhn’s end was sad, as was his neglect over the following decades. Museums and art historians paid little attention to his work, and he became an afterthought, remembered only for his role in the Armory Show. Fortunately, the centennial of the show has brought Kuhn much-deserved attention. Unlike Arthur Davies, whose work has dated quality that’s hard for contemporary audiences to overcome, Kuhn’s portraits have an intensity that seems just as relevant today as when they were painted.

So, how do you respond to Walt Kuhn? Do these paintings grip you as much as they grip me? Let me know what you think in the comments.

May 30, 2013

Happy birthday, Alexander Archipenko, founder of sculptural Cubism

Typically, we think of Cubism as a painting style. The most famous Cubists–Picasso, Braque, Duchamp, Leger–were all painters. But sculptural Cubism was just as innovative as painting, and just as significant in the development of modernism.

Today happens to be the birthday of one of the most interesting and important sculptural Cubists, Alexander Archipenko–a sculptor who made a big splash at the Armory Show.

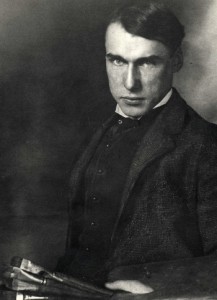

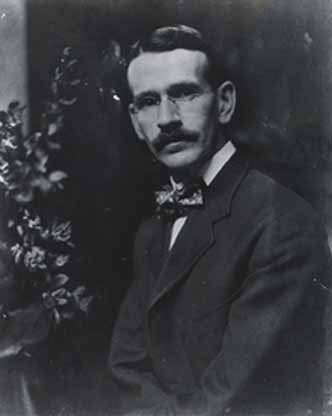

Alexander Archipenko, ca. 1920

Here’s Archipenko about 1920, looking all moody and artistic. Love the way he’s turned up his coat collar.

Archipenko was born in Kyiv (aka, Kiev) in the present-day Ukraine, then part of Russia, in 1887. He trained in Kyiv, then moved to Moscow in 1906. In 1908 he settled in Paris and quickly associated himself with an avant-garde circle of artists who lived together in a ramshackle circular building nicknamed La Ruche–the beehive–for its resemblance to, well, a beehive.

La Ruche catered to artists–rent was cheap, and no one was ever evicted. A nearby canteen operated by the relatively financially secure Russian artist Marie Vassilieff offered meals and wine for almost nothing. As a result, artists poured into the building, many of them immigrants from Russia and Eastern Europe. An amazing array of talent called La Ruche home, including Marc Chagall, Fernand Leger, Max Jacob, Robert Delaunay, Amedeo Modigliani, and Diego Rivera.

Archipenko exhibited with other avant-garde artists at exhibitions such as the Salon des Independants, and when the organizers of the Armory Show arrived from New York in the fall of 1912, Archipenko was immediately placed on the list of exhibitors.

He sent four sculptures to New York, along with several drawings. The work that attracted the most attention was his piece La Vie Familiale:

Alexander Archipenko, “La Vie Familiale,” 1912

This photo of the work is from a series of postcards that were sold at the Armory Show, and unfortunately it’s one of the only reproductions of the sculpture. The original was destroyed in World War I in a German bombardment of Paris.

It’s not a great picture, but you can get a sense of the simplication and streamlining that Archipenko brought to forms. He reduced them to their essential shapes. This was very much the theme of Cubist sculpture whether practiced by Archipenko, Constantin Brancusi, or Raymond Duchamp-Villon. Late 19th-century sculpture was all about emotion and drama–the most popular artist of the era was Auguste Rodin. Think about his contorted, emotional figures–his Thinker, his Kiss. Now contrast that with these pared down shapes. That’s what sculptural Cubism was all about.

His works only got more streamlined as time went on. Here’s a wonderful piece from the World War I period:

Alexander Archipenko, “Walking Soldier,” 1917

Such simple shapes, and yet so evocative. The droop of the cape makes the figure seem so worn down and tired. Somehow I envision it raining.

Alexander Archipenko, “Carrousel Pierrot,” 1913

However, while Archikpenko streamlined his shapes, he sometimes enlivened them in other ways, applying bright colors to his figures. Archipenko was interested in overlapping the arts of painting and sculpture–he didn’t see why a sculpture couldn’t be painted, or a painting be three-dimensional. He retained this fascination with crossing artistic boundaries his entire life. Here’s a late work from 1957 that incorporates both paint and objects:

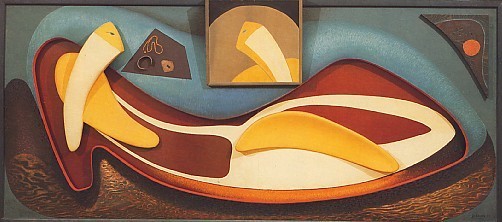

Alexander Archipenko, “Cleopatra,” 1957

However, I think my favorite works by Archipenko are his pure shapes, often of the human body.

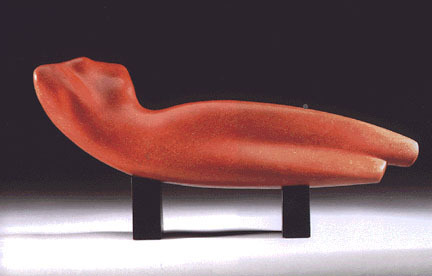

Alexander Archipenko, “Torso in Space,” 1936

He gives his figures such fluidity of movement.

My editor, god bless him, would hate that sentence. He spent most of my book highlighting things and writing “Too textbook-y!” He was absolutely right. Who in their normal life says things like “fluidity of movement”? It’s art-speak, and I apologize for it, but I’m going to defend it here for just a moment. There’s a sense of movement in that shape, in the way the hips twist, one shoulder twists, and one leg extends longer than the other. Even that I’m using words like “hips” and “shoulders” is part of the magic, because only the slightest bit of definition makes the shape of the body clear.

Alexander Archipenko, “Torso,” 1948

I also love the tactile nature of these works. These are both terracotta, but the finish gives them very different qualities. The black figure seems matte, dull, and heavy, while I image the red one feeling smooth and warm, like polished wood.

Alexander Archipenko, “Blue Dancer,” Conceived 1913, Cast ca. 1960

This is so wonderful–it reminds of dancing Hindu goddesses, yet simplified into its most essential elements. The balance is so complicated yet exactly right.

So happy birthday, Alexander Archipenko. And here’s to scuptural Cubism, which should be better remembered than it is.

May 22, 2013

Tonight we’re going to party like it’s 1565!

Busy week, friends, busy week—not so much with work (shh, don’t tell my clients or my editor. Oh, hi, clients and editor!) but because we’re having some friends over on Saturday. Now, this is not a particularly huge or involved event, so it shouldn’t take a full week to prep for it, except that I spent that last several months writing a book. During that time, I let certain things slide. Like the utility room, which was rapidly becoming hard to walk through. Or the yard, which remained mowed thanks to my yard guy (That would be my dad. My dad is my yard guy. He works cheap.) but untrimmed, unweeded, and generally unloved.

Entertaining is a great reason to generally spiffy up, put away, declutter, and vacuum all the crumbs out of the sofa cushions. And then there’s the fact my husband is turning 42, and as any fan of Douglas Adams knows, 42 is the most important number in the universe. Seems like as good as an excuse as any to invent people over. (Said husband has promised there will be Pan Galactic Gargle Blasters. I’m not sure how, as Ol’ Janx Spirit is unavailable in this solar system, but he will contrive.)

This got me thinking about parties in art, and there are many to choose from. Toulouse-Lautrec at the Moulin Rouge. The luscious riverboat parties of Renior. But the best parties for my money are those depicted by Pieter Breughel the Elder. There ain’t no party like a Breughel party. Those people knew how to get down.

I’ve looked at the work of Breughel before, in particular his Netherlandish Proverbs. He made a name for himself painting marvelously crowded and detailed paintings of peasants in his native Netherlands.

We’ll start out with a relatively restrained dinner celebration:

Pieter Breughel, “The Peasant Wedding,” 1567 (Click image to enlarge.)

What a wonderful composition. That long angle of the table, zig-zagging and extending to the door covered with plates, draws you into the work. The colors are wonderful–notice how he scatters red and green against the brown-gold floor and walls. The light yellow of the man in the foreground pops against the man in black and the green banner behind him.

The bride is sitting under that green banner. She looks quite satisfied with the festivities.

Pieter Breughel, Detail from “The Peasant Wedding,” 1567

Those are probably her parents sitting next to her. The question, of course, is where’s the groom? No one is quite sure, although some experts think he’s the man pouring out beef in the front:

Pieter Breughel, Detail from “The Peasant Wedding,” 1567

It’s important to note the poverty apparent in the event. They’re in a barn, hopefully well-cleaned for the evening. A door taken off its hinges is used to carry food. The food is incredibly simple—bread, porridge, and soup. There might have been a little meat in the soup, but not much.

But they’re having a good time. They’ve even got music from the two men playing pijpzaks, an early form of bagpipe:

Pieter Breughel, Detail from “The Peasant Wedding,” 1567

After the feast, the party got more raucous when the dancing started. Here’s another work by Breughel, The Wedding Dance, one of several versions he did on this subject.

[image error]

Pieter Breughel, “The Wedding Dance,” ca. 1566 (Click on image to enlarge.)

Now folks are really starting to loosen up. The entire village must be there, and maybe the village up the road as well.

The bride in this work is dressed in black, which was apparently popular at the time:

Pieter Breughel, Detail from “The Wedding Dance,” ca 1566

She’s not what you call svelte, is she? Neither am I, so I’m not judging her, just noting that there’s no attempt to make the bride conventionally (even conventionally for 1566) pretty.

And then there are the men. Oh, the men.

Pieter Breughel, Detail from “The Wedding Dance,” ca. 1566

And hello to you, too, sir!

Codpieces were essential fashion, even for peasants. You’ll notice all the men have them, and it’s just incredibly silly. Of course, so were acid-washed jeans.

A great deal of criticism of this piece focuses on the unrestrained dancing on display, which was the sort of thing that the authorities of this era frowned upon—even tried to outlaw. People weren’t supposed to swing their arms to widely or laugh too loudly. They were supposed to be restrained and modest. The upper classes would never have let themselves go like this (unless they were slumming it, I suppose, although that could result in many unfortunate diseases). The sort of people who could have afforded to buy this painting from Breughel would have tut-tutted and used the work as an example of the rowdy, unruly behavior of those damn peasants.

No one’s quite sure how Breughel felt, though. I don’t see either this painting or the one above as critical. I think they’re celebratory. Breughel seems like the kind of guy who would have jumped right in.

One last detail from this work—I love the background:

Pieter Breughel, Detail from “The Wedding Dance,” ca. 1566

There’s a couple making out at some distance from the party—and as best as I can tell, that’s a guy relieving himself on the tree in front of them. Love it.

Now, if you think the wedding party was wild, you ain’t seen nothing. Here’s what went down on St. Martin’s Day:

Pieter Breughel, Detail from “The Wine of St. Martin’s Day,” ca. 1565-68

St. Martin’s Day was a festival celebrated on November 11. It officially marked the saint’s day of St. Martin of Tours, but really it was a party. By this time, the harvest was in, and it was time to kill the pigs and enjoy the first wine of the season. Traditionally, a barrel of wine was distributed free to the people outside of the city gates.

So we’re seeing people who have worked and slaved all summer long and now are finally able to enjoy the fruits of their labor and relax a bit. They may not have had wine in a long time—they might not have been able to afford wine most of the time. Peasants drank beer.

Some of them are enjoying the wine a bit too much.

Pieter Breughel, Detail from “The Wine of St. Martin’s Day,” ca. 1565-68

They are imploring a rich man on a horse for alms. His response at first seems antagonistic:

Pieter Breughel, Detail from “The Wine of St. Martin’s Day,” ca. 1565-68

At first glance, it looks like he’s drawn his sword to threaten the beggars. But you need to know some background.

St. Martin of Tours was supposedly a soldier in the Roman army. One day while riding into a city, he encountered a scantily-clad beggar. Impulsively, he pulled his sword and cut his cloak in half to share with the beggar. That night, he dreamed he saw Jesus before him wearing the cut half of the cloak. When he woke the next morning, the cloak had been miraculously restored.

So that’s what we’re seeing: St. Martin about to cut his cloak—the rippling rose-colored cloth—and share it with the beggars. And no one is paying attention.

Critics of the era would have condemned the secular celebration of St. Martin’s Day even more harshly than the dancing at the wedding. It was essentially a drunken party that had nothing to do with religion, and upper classes would have been disgusted by the sort of behavior on display in this painting. It’s certainly a less-sympathetic portrayal of the peasantry. But I’m not entirely convinced Breughel doesn’t understand and empathize with these people. Notice how torn and ripped their clothing is–notice the broken potted and cracked pitchers they are using to get the wine. These were people who lived on the permanent edge of starvation and utter destitution. One bad harvest, one sickness, one accident, and you were among the beggars, or you were dead. I think Breughel understood that.

(BTW, this painting has an interesting history. It was part of the collection of the Prado Museum in Madrid for years and no one had any idea it was a Breughel. It was rediscovered, cleaned up, and now is hailed as a masterpiece. You can read about it and related issues here.)

I need to get back to party prep now—I need to go buy a bowl of petunias. (Readers of Hitchhikers will understand.) I hope our party is more along the lines of the wedding party or the feast. We are not starving peasants desperate for alcohol, so there will be no passing out and no hair-pulling.

And, um, no codpieces. OK, guys?

May 15, 2013

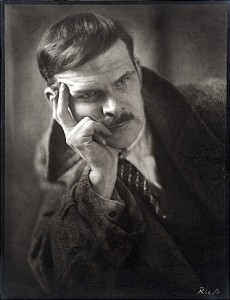

Today’s Artist You’ve Never Heard Of: John Sloan

John Sloan, 1891

John French Sloan didn’t make a big splash at the 1913 Armory Show, and in fact he was only marginally involved in the organization of the event. But he was a significant artist of his era and darned interesting guy. Sloan was an idealist, and he put in art in service of his ideals. He’s been criticized for rejecting modernism, and in fact he thought Cubism and other art from Europe was a waste of time. But his reasons were more complicated than you might think.

Sloan was born in 1871 and grew up Philadelphia, where he lived and studied art until he moved to New York in 1904. He was part of a circle of young, aspiring artists from Philadelphia that included William Glackens and Robert Henri. Many in this group believed American art needed to break away from the artificial and often frankly ridiculous academic art that had been imported from Europe. They despised the mythological scenes and heavy-handed morals of academic art. Instead, they wanted to paint real Americans leading real lives.

This artistic movement had parallels in wider cultural movements. Think about the muckracking journalists who investigated factories and tenements and slaughterhouses at this time. Ever read Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle? Same time period, same impulse to document working-class life.

The result was a desire to paint scenes from ordinary life in the rougher neighborhoods of New York. Sloan lived in Greenwich Village, then the home of Bohemian New York, and he devoted many paintings to scenes of the Village or nearby immigrant neighborhoods in the Lower East Side.

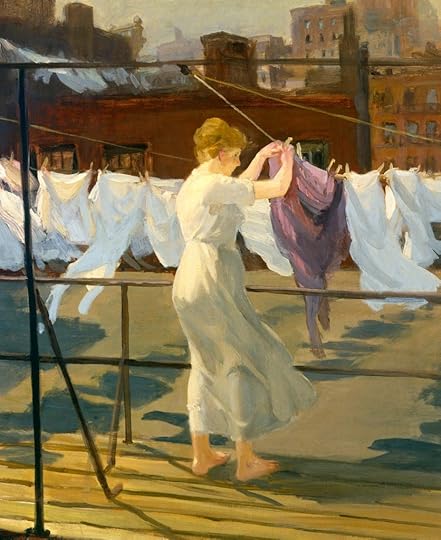

John Sloan, “Sun and Wind on the Roof,” 1915. (Click to see a larger version.)

Here, for example, is a woman hanging laundry out to dry on the roof of her apartment building. Sloan painted many views of rooftops–it was the only open space most people had. Tenements were awful, dark, crowded places. Getting up on the roof gave you some light, some sun, some air. And where else would you dry your laundry? Not in a damp tenement.

This doesn’t seem like a particularly radical painting today, but Sloan’s subject matter raised eyebrows in artistic circles. Paintings of ordinary life were unheard of. Paintings of poor people were unheard of.

In fact, Sloan and his fellow artists were criticized for their “inappropriate” and “vulgar” art. They were labeled the Ashcan School, and it wasn’t a compliment. Sloan hated the term.

But back to the roof pictures. There are tons of them.

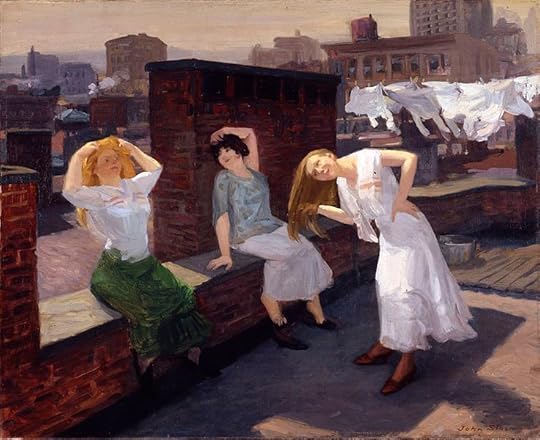

This painting, “Sunday, Women Drying Their Hair,” was Sloan’s contribution to the Armory Show. Once again, it’s a slice of ordinary life. Sunday you got a bath. (Can you imagine living in a filthy big city full of gas lamps, horses, and god knows what else and only getting a bath once a week?) Most women wore their hair long, and they certainly didn’t own hairdryers. But combing out your hair in the sunshine was a chance to talk to your friends, to laugh and relax on a bright sunny day.

John Sloan, “Sunday, Women Drying Their Hair,” 1912

Sloan also did lots of etchings–it was one of his favorite mediums. This is a very late work from 1941, Sunbathers on the Roof. It looks hot, the couple looks sleepy, and that cat looks like it needs a square meal.

John Sloan, “Sunbathers on the Roof,” 1941

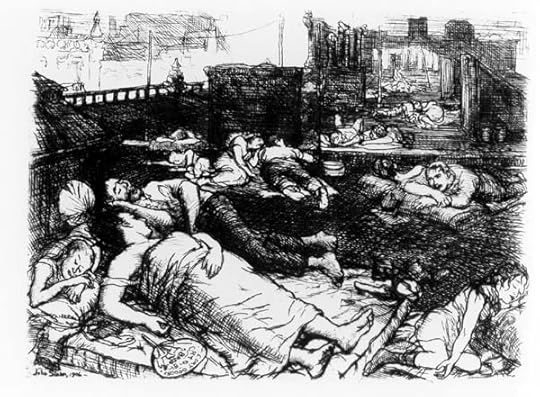

One more roof etching–this is much earlier, from 1906. In the summer, when it was hot, people of course didn’t have air conditioners–they didn’t even have fans. There are descriptions of people hauling mattresses onto fire escapes or even into Central Park to sleep. Of course they went to the roof. And then it turned into a building-wide slumber party, with all your neighbors sprawled out all around you.

John Sloan, “Roof, Summer Night,” 1906

Sloan also painted cityscapes, many from his studio in a high building in Greenwich Village.

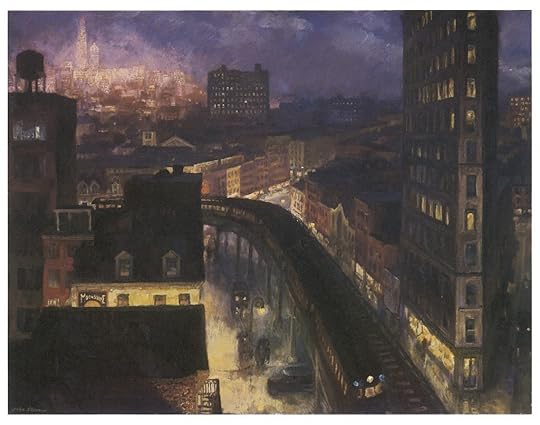

John Sloan, “The City from Greenwich Village,” 1922

The train is elevated, not yet a subway, and Midtown Manhattan seems far, far away, glittering like Oz on the horizon.

While many friends in Sloan’s circle of friends painted similar works of everyday life, Sloan had an added, political motive for his art. He was a committed Socialist. It’s hard to look at Socialism from a pre-World War I perspective. This was before the Russian Revolution, before Lenin and Stalin and Mao and all of the totalitarian baggage that Socialism and Communism picked up over the years. Sloan was reacting against the truly appalling behavior of Gilded Age plutocrats such as Rockefeller and Carnegie, who would seemingly stop at nothing, including shooting strikers from their own plants, to make more money.

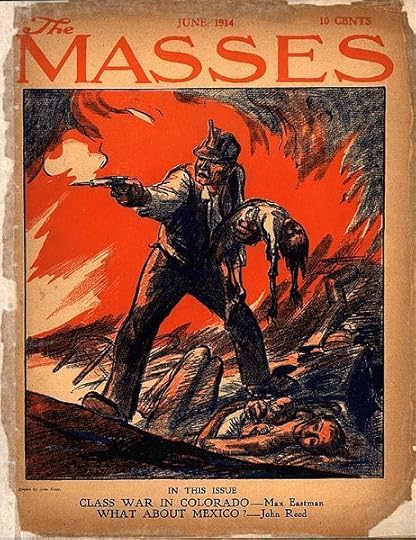

Sloan got involved with The Masses, a radical Socialist magazine published out of offices in Greenwich Village, soon after it was founded in 1911. He contributed numerous illustrations, cartoons, and covers for the magazine over the years. Probably this is the most dramatic and memorable:

Cover for the June 1914 Issue of The Masses by John Sloan

The cover commemorates the Ludlow Massacre, when Colorado National Guard troops and Colorado Fuel & Iron Company camp guards attacked striking miners and their families in Ludlow, Colorado in April 1914. Two women and eleven children were among the up to twenty-five people killed when troops and guards fired on strikers with machine guns and set fire to tents. It was an appalling incident, and Sloan milks it for all its worth.

The Masses and Sloan were naturally opposed to World War I, which they saw as a fight between imperalist capitalists fought with the lives of workingmen. Sloan contributed editorial cartoons in opposition to the war:

John Sloan, “After the war a medal and maybe a job.” 1914 (Click for a larger version.)

That’s a fat capitalist offering a dying soldier “maybe a job” after the war.” It’s kind of over the top, but the anger is clear. And considering the carnage of WWI and the shameful treatment of veterans after, it’s not too far off the mark.

Sloan was a member of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors that organized the Armory Show and took some part in running it, but not much. He devoted more time to running The Masses than at the Armory. And when the show took off and became the most popular subject of the press, he contributed a cartoon to his magazine on the subject of Cubism:

Some people have criticized Sloan for not embracing Cubism and other modern art movements with more enthusiasm. In fact, he had a thoughtful response to modern European art. He thought it was self-involved.

In modern art, the subject is less important than the style. Often the subject has very little inherent meaning–when Picasso painted a Cubist still life with a mandolin, the mandolin didn’t have any meaning or message–it was just an object of an interesting shape that Picasso could manipulate. Discarding meanings and messages was a critical part of most modern art. Modernists wanted to move art away from the ham-handed morals that were required of academic art.

But Sloan believed art should have a message. He rejected the false morality of academic art, but he wanted art to serve a social purpose. His rejection of modernism wasn’t knee-jerk conservatism–it was carefully reasoned and based on deeply held beliefs.

So what do you think–was Sloan right or wrong? And what do you think of his art? Personally, I think his political work is clumsy but his paintings and etching are insightful and all the more valuable today since they give a glimpse into a lost world.

May 8, 2013

Today’s artist you’ve never heard of: Arthur B. Davies

And lo! I have written a book.

It’s been a long few months, friends, with much fretting and editing and muttering to myself. I have drunk innumerable cups of chai tea at various coffee shops. I have developed a new-found passion for 3×5 cards and have scribbled upon and sorted and tossed out and rearranged them at length on the tables of the various coffee shops. I have done very little laundry, and what laundry was done was neither folded nor put away.

I had great plans to keep up the blog while working on the book, but that turned out to be as hopeless as keeping up with healthy eating while working on the book, or exercising, or dusting. But now it has been turned in, it is officially my editor’s problem, and I can pick up the pieces of my life. (Of course, there will still be copyedits and galleys and whatnot, but all that seems eminently manageable right now.)

So far, so good. I got the trash and recycling bins to the curb (you have no idea how many times I’ve missed trash day in the last six months), ate a healthy breakfast, went to yoga, cleaned my desk, and now am updating the blog. I feel so productive I may have to lie down.

The good news is that even after all this time, I still find the 1913 Armory Show a fascinating topic. One of the strongest feelings I’ve developed over these months is that it’s really a shame that so many artists associated with the show aren’t better known. Of course Marcel Duchamp is known–and Picasso and Matisse. But most of the American artists have been forgotten. And that’s unfortunate. So I will do all I can in my wee little way to make up for it.

Arthur B. Davies, American artist and organizer of the Armory Show

We’re going to start today with one of the most important artists for the Armory Show, the president of the association that organized the show, Arthur B. Davies.

Not a bad looking guy. Kind of distinguished.

He was born September 26, 1863 and died October 24, 1928. Prior to the Armory Show, he built a reputation as a well-known avant-garde artist. He exhibited with The Eight, a group of Americans headed up by Robert Henri, who would become his nemesis during the show.

This designation of Davies as “avant-garde” seems weird today, because his art doesn’t seem the least bit progressive or modern or radical. It looks, in fact, incredibly old fashioned–far more dated that the work of Cubists or Fauves produced at the exact same time in Europe.

I think this has to do with the way modern European art “won” in art history. If you think of art history as a river (stick with me here), at the time there were all these streams and rivulets existing at the same time and receiving equal attention. However, in the middle of the last century, historians decided the modernist stream was the most important–the stream that included Picasso, Matisse, Brancusi, etc. Instead of a bunch of equally valid waterways, from our perspective it looks there was a single dominant river with several little, unimportant streams running alongside and eventually dying out.

From that POV, Davies’s art is unimportant. But I disagree with this notion that holds art is only important if it led to other, even more important art. Davies was significant in his time, and he still has something to offer today.

Does that mean I’m a big fan? Well. No.

“Unicorns (Legend—Sea Calm),” ca. 1906

He painted unicorns, for crying out loud. Without a hint of irony. And I’m sorry, but his earnestness kind of makes me want to giggle.

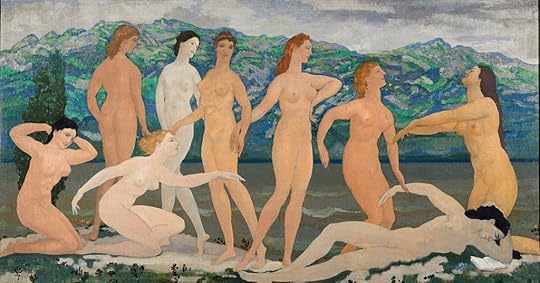

He really liked nude women. Really liked them. Liked them wandering through landscapes–you know, as you do. With your other nude friends.

“Rhythms,” ca. 1910 (For a larger version, click on the photo.)

It’s supposed to be about the beauty of the female form. I get that. But to me, many of Davies’s nudes seem awkward. Stiff. Posed.

I think I’m just too much a creature of my own time to really get Davies. I understand on an intellectual level. He’s of the same general strain as the Pre-Raphaelites–not in terms of artistic style, but in that mode of painting mystical, ethereal, beautiful women, the more the better. It’s got an element of objectification that I find disturbing. These aren’t real women with internal lives. They’re figures, types.

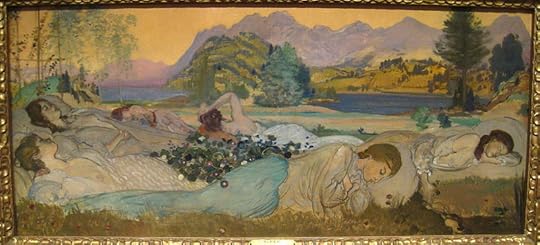

“Sleep Lies Perfect in Them,” ca. 1908

Davies was himself not always the most stand-up guy with respect to women, either. I’m going to save the full story for the book, and WOW, it’s a kicker. (You can find it online, of course, or you could wait until October and read it in my book!) He could be incredibly selfish. I think he had trouble with real women. His relationships always faltered when women became more than models and objects and started wanting their own lives.

However, I think when he painted real women, his work is much stronger than his artificial types.

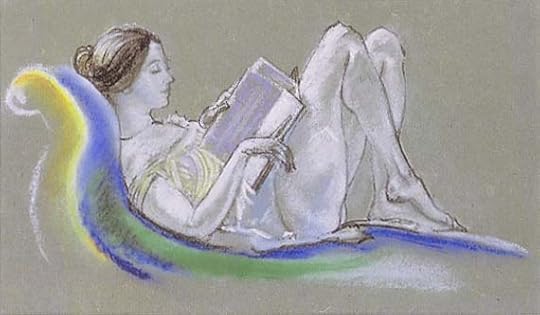

“Woman Reading,” 1911

This is my favorite Davies’s drawing. It’s of a real person, his model and lover Edna Potter, and I think it’s charming. Look at that pert little nose. And you’ll notice she’s nude from the waist down. Racy. But she’s a real person, not “Woman.”

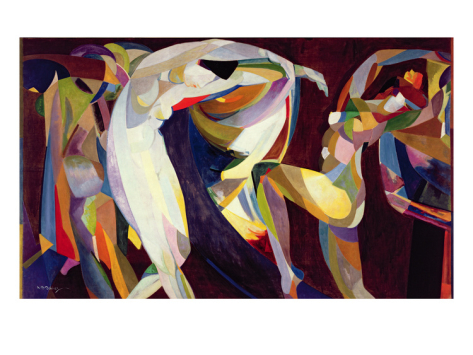

Immediately after the Armory Show and his encounter with Cubism, Davies experimented with Cubist-like art, with mixed success. What I like the most is that he was eager to try new things in his 50s as an established artist. Not many people have the confidence to take on something entirely new at that point in their career.

“Dances,” 1914/15

Still nudes in improbable poses, but here the emphasis on movement and rhythm is less icky because they’re so obviously, completely not real people.

Davies’s work is held in major museums around the world–the unicorn painting is at the Metropolitan in New York. But you won’t see it there because it’s not on display. This is the fate of many Davies’s paintings. You would probably have to go to a regional museum with a more limited collection to see Davies’s art in person.

So there you are: an artist you’ve probably never heard of. I’ve got dozens of ‘em–and I can’t wait to share. I’m glad to be back to blogging.

October 11, 2012

Amazing journeys in ancient times

Oof! It’s busy, busy days around here, my friends. Things should actually settle down once I start writing the actual book. Right now I’m juggling several other projects, trying to wrap them up as best as possible. I’m making progress, but it’s been wacky.

But I saw the most fascinating thing last night that I wanted to share.

Check out this little gem:

Helgo Buddha, 6th century A.D.

It’s a tiny–10 centimeter tall–bronze Buddha dating from the 700s. And it was found in Sweden.

Here’s the background: I was watching Nova on PBS (while paying bills–no time for leisure TV right now)–a show on Viking swords. I wasn’t honestly that interested, never having a particular interest in swords, Viking or otherwise. It seemed like perfect bill-paying background TV.

But these swords—known as Ulfberht—were made from remarkable steel that, as best anyone can tell, no one in Western Europe knew how to make. Europeans wouldn’t have this technology for nearly a thousand years. The high-grade steel made these blades particularly strong and sharp and far less prone to shattering in battle. The blades were so prized that they were, in effect, trademarked with the name Ulfberht, although today no one knows if Ulfberht was a family, a place or something else entirely. Of course, trademarking has its own risks, and numerous fake Ulfberhts have been discovered, usually broken to bits. Medieval blacksmiths could probably get a lot of money selling counterfeit swords, although I wouldn’t like to be the guy who fooled a Viking.

The question, of course, is where did the steel come from, if not Europe. The answer is surprising: Central Asia, possibly what is today Afghanistan. Which, you’ll note, is a long way from Sweden. Particularly if the only way you can get there doesn’t involve jet engines.

We tend to think about the Vikings heading out to rampage and pillage to the south and west. I associate the Vikings with the British Isles–with Lindisfarne and Dublin. With France and Belgium. With Iceland, Greenland and the far edge of North America.

But the Vikings traveled East as well as West. They conquered the hell out of Russia–the “Rus’,” likely meaning “men who row,” were Vikings. They sailed down rivers all the way to the Black Sea and then out to the Mediterranean. They made it all the way to Baghdad and brought back silver coins that have turned up from Gdansk to Greenland.

They also brought back this Buddha. Somehow it made it from Northwestern Indian to Helgo, Sweden, where it was excavated in the 1950s along with a Christian crozier from Ireland and an baptismal basin from Egypt.

So many questions! Did the owner know who the Buddha was? What he taught? It’s hard to image a way of life more at odds with the teachings of Buddhism than that of the Vikings. Was it just a pretty statue, valuable for its rarity? Or was it sacred? What was the story? Because you know there was a story. The story was essential to its worth.

Today I sit surrounded by objects made all around the world. I picked up a few things more or less at random and saw China, Taiwan, India, Malaysia, U.S.A. (huh!), China again, Japan, Mexico. We give it little thought.

But here is an object that traveled far fewer miles that most of the stuff in my office and yet was so rare and unique we still marvel at it 1400 years later. Amazing.

Oh, and just so you know, I didn’t finish the bill-paying. I’ll have to find something more boring to watch tonight.

(Curious about this story? You can read more at the PBS website and even—for now—watch the entire Nova episode online: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/secrets-viking-sword.html.)

October 3, 2012

Looking at Art: John Singer Sargent’s “Portrait of Madame X”

I love me some Pinterest. Not only can you find recipes for pull-apart pizza bread (which, seriously, has been re-pinned 80 million times), but you also see the art that people find particularly transfixing.

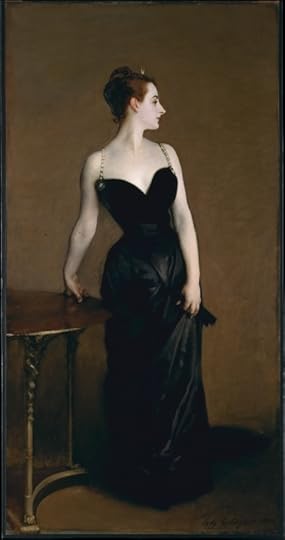

A favorite of mine popped up yesterday, and I decided it would make a good story today: Portrait of Madame X by John Singer Sargent:

John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Madame X,” 1884

It’s a famous work, one that caused a scandal when it was first shown at the Paris Salon of 1884. The figure’s bold beauty and plunging decolletage shocked Paris society. The model was a well-known social figure named Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, but Sargent departed from traditional society portrait painting by depicting a highly sexualized, if sophisticated, figure. The whole “Madame X” business was a futile attempt at keeping Geautreau anonymous.

One detail was particularly scandalous: the gold chain straps of her satin gown. In the original painting, the right strap had slipped down to reveal a bare shoulder. Proper French matrons had palpitations–a bare shoulder? Sacre bleu! Sargent eventually repainted the strap at the request of Gautreau and her family.

Notice the elegant turn of the neck and elevated chin. The pose reminds me of a ballet dancer’s–all elongated and heightened. The expression of haughty elegance is marvelous. If you search Google for this painting, you’ll find it’s a favorite of art students, who attempt to recreate it. The biggest challenge most have is with the facial expression. They make Gautreau look disdainful or remote; in the worst, she seems to be smelling something horrendous. Gautreau’s effortless sophistication is hard to pull off and even harder to paint.

The gold glint at the top of her head is hard to make out–it’s a tiny tiara with a gold crescent moon. The imagery alludes to the goddess Diana the Huntress, another powerful, beautiful woman.

The tilt of Gautreau’s nose is marvelous. Look at that determined chin and thin but elegant lips. Today’s beauties all pump their lips up so they look like they’ve been attacked by bees. Gautreau is more refined.

I love how Sargent used little swirls and strokes of paint to capture the fine curls of hair at her neck. And notice how the red of her ear stands out against the ivory of her skin. I also love how the coral red of the ear contrasts with the ruby of the lips. One is natural, the other artificial.

Sargent positioned Gautreau leaning against a table with her weight on one arm but turning away to the opposite side. This gives tension to her hand and arm, which is braced with the elbow turned out. This is an old painting trick known as contrapposto when you have a figure with weight off-balance and their body turning. (Leonardo did it with the Mona Lisa.) The pose gives the figure a sense of potential movement, of dynanism.

Look at that tiny waist–oh, what a corset could do! And how uncomfortable she must have been.

Sargent depicted Gautreau without any jewelry except her tiara and her wedding ring, which gleams gold against the black and ivory. The lack of jewelry was shocking to audiences, since the fashion was to be absolutely dripping with it. The implication is that Gautreau has returned home from an evening out and taken off her jewels. That makes this not a public moment but a private one. Add the slipped strap, and the implication is that Gautreau’s getting ready for some hanky-panky after a night of parties.

You may now clutch your pearls in horror.

Notice how Sargent created the draping of the dress with criss-crossing sweeps of the brush. It’s not easy to give depth and substance to a black dress–it would be easy for it to be a black blob. The careful gray highlights add three-dimensionality.

The floor may not seem that interesting, but there’s some fun art references going on here. Look behind Gauteau and the table at the background. Can you see the point where the floor ends and the wall begins?

You can’t, not clearly. It’s hinted by the shadow behind and to the right, but if that were the wall the space would be relatively shallow, and if you look at the entire painting we don’t sense Gautreau is standing with her back at a wall.

Sargent likely borrowed this technique of the floor-bleeding-into-the-wall from Diego Velazquez, the Baroque Spanish artist. In many of Velazquez’s portraits, the wall is indistinguishable from the floor except by shadows. (Check out this example.) The result is a sort of indeterminacy about the space. It’s not the sort of thing you notice until it’s pointed out, and then you realize Velazquez did it all the time.

Edouard Manet, a huge fan of Velazquez, picked up the trick in the 1860s, and here’s Sargent doing it in 1880s.

I’ve seen this painting at the Met, and it’s marvelous in person. The black is rich and luscious. Gautreau is stunning. It’s an amazing painting. If you find yourself in New York, don’t miss it. I suspect you’ll be more amazed than horrified.

October 2, 2012

Big news, big day! I may start making whooping noises without warning!

OK, y’all—I have a surprise for you.

Yes. It’s really that exciting.

I’ve been working on this for MONTHS. I don’t know how many times I thought the whole thing was dead in the water.

It’s OK. Don’t be so apprehensive. Everything has worked out fantastically.

So you know how I wrote those books, right? And it was amazing and wonderful and I loved it?

Quit looking at me like that. OK, yes, I complained about it A LOT, but the end result was AWESOME.

So . . .

I get to do it again. I’m under contract to write another book.

WHEEEEEE!

And the super-amazing part of this is that while the Secret Lives books were fun and cool, this book is my own idea, dreamed up in my own head, pitched via my own agent. The other two books were assignments—fabulous assignments, yes, but the product of someone else’s vision. This book? This is mine.

Hang on, I’m going to squeal again. WHEEEEEEE!

Sorry about that. I’ve been doing it randomly around the house all weekend. I had a cold and spent most of the last few days in bed, so sometimes it was a pathetic whee, muttered into a pillow, but still.

So what, you ask, is this alleged book?

The title right now—and this could totally change—is The Modern Invasion: Picasso, Duchamp and the Art Show that Scandalized America.

It’s about the famous Armory Show of 1913 that brought modern art to America and shocked everyone with Cubism and Fauvism and fractured nudes descending staircases. It was a turning point in American art, the start of the rise of New York as a cultural capital and a shift in how people thought about creativity.

The good news is that it will be published in the fall of 2013, in time for anniversary celebrations of the Armory show. The, er, stressful news is that my manuscript is due IN MAY. May is like, tomorrow.

So I will probably lose my mind a bit in the next few months. Posting may be even more erratic than before. But I want to share what I’m learning–the art, the stories, the fun details.

I couldn’t be saying this without the hard work of my agent, Russell Galen, or my new (!!!!) editor Jon Sternfeld at Lyons Press. Jon totally gets this project. I’m so psyched to be working with him.

So! There’s the big news. What do you think?

My thoughts exactly.

_________________________________

(The art from today’s post is drawn from the vast assortment of self-portraits by Rembrandt, who practiced painting facial expressions with a mirror.)

September 25, 2012

Mountains, the sublime, and where the heck I’ve been lately

So . . . I meant to take a week or so off. I meant, in fact, to post that I meant to take a week or so off. But it didn’t happen that way.

Sorry?

But hey! I’m back, and I’m finally finishing a post I started ages ago.

You see, part of my disappearing act involved a trip to the New Mexico and Colorado mountains. I’m from North Texas, and a summer trip to New Mexico and/or Colorado is practically required. We live in a very flat, very hot land, and there comes a point every summer where if you don’t get away you will have a meltdown in the driveway, by which I mean you will literally melt in your own driveway. The only cool locations within driving distance are Northern New Mexico and Southern Colorado, so everyone packs up the car, has breakfast in Wichita Falls and lunch in Amarillo, and fetches up in Santa Fe about dinner time.

View from Wolf Creek Pass near Pagosa Springs, Eric Voss. Members of my family have been taking variations of this photo for more than 60 years. I found this one online, thus proving other people also find this view irresistible.

This tradition is generations old. In lucky families, an earlier generation invested in a cabin. (No one in my family apparently had that sort of forethought, or perhaps capital.) The result is that Texas families have “their” mountains. Families have “always” gone to Red River, or Eagle’s Nest, or Raton. They go back every year or every few years and develop traditions. It becomes essential that they eat at certain restaurants, visit certain national parks, shop at certain gift shops.

In my family, our mountains are those surrounding Pagosa Springs in southern Colorado. My mom went there as a kid, and my husband and I took our honeymoon there. And this year, for the first time in ages, we got to go back.

It was fantastic. Our first day in Pagosa Springs, we drove out to the National Park and found “our” stream, a rushing mountain rivulet with an island in the middle. As long as I can remember, the mission has been to cross the stream and get on the island. The difficulty of the task changes every time based on the locations of rocks and fallen trees–this time it was a snap, but other years it’s been hair-raising. The first year I took my husband there, he asked “Now why are we crossing this stream?” and I honestly didn’t have a good answer other than that that’s what you do. It was proof that I married the right guy that he accepted this without question and entered into the stream-crossing enterprise with vigor.

My husband in the middle of "our" stream. Yes, he did in fact have a heck of time getting back to dry land.

Once we got onto the mystical island, there’s a spot you can sit with a waterfall in the foreground and towering mountains in the background and rushing water on either side. It’s magnificent. Everything’s pounding and roaring and soaring and it all leaves you breathless.

What does this have to do with art or culture? Well, the sense that I got sitting on that stream is surprisingly historical. It’s not universal but rather cultural.

Prior to the mid-18th century, most people had no appreciation for mountains at all. English writers and artists in particular found mountains nothing more than annoyances, hindrances to agriculture and a barriers to travel. Mountains were described in English literature as barren protuberances, insolent and inhospitable; as blisters, tumors or warts.

To some degree, these attitudes were borrowed by English writers from Roman writings; the Romans seemed to see mountains as inconveniences. For other English writers–particularly earlier ones–the negative view of mountains was largely based on ignorance. Shakespeare, for example, almost never mentions mountains, but then he probably never saw one. England is hilly but not mountainous, and he never ventured to more rugged portions of Wales and Scotland.

By the 17th century, however, many English writers had traveled and seen mountains. And they weren’t impressed. Andrew Marvell called mountains hook-shouldered and unjust, excrescences (love that word) that deform the earth and frighten the heavens.

This attitude started to shift in the 18th century, and by the 19th mountains were a favorite subject for poets and artists alike. So what changed?

What changed was Romanticism, which was more than a poetic movement. Romanticism was a whole worldview that, among other things, saw nature (Romantics would say Nature) as a source of inspiration and wisdom. Critical to all this was the concept of “the sublime,” which describes something vast, mysterious, awesome, terrifying yet wonderful. In other words, mountains.

In a space of a hundred or so years, people went from being annoyed by mountains to near worshipping them. Instead of being inconvenienced by the Alps, which made travel from France to Italy so difficult, people came and marveled at them. Mary Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron spent a summer near Geneva and went around appreciating the mountains like mad (when they weren’t telling each other ghost stories.) These were the same mountains that Voltaire lived amongst for 20 years and hardly noticed at all. (In his Philosophical Dictionary, the best thing Voltaire could say about mountains is that they were the source of streams and rivers that nourished life in the valleys.)

Wordsworth could hardly see a hill without swooning. Even the sober Jane Austen caught the fever, or at least conveyed it to her heroine Elizabeth Bennet. When Lizzy is invited to tour the Lake District with her aunt and uncle, it evokes a reaction twenty times more effusive even Mr. Darcy’s proposal of marriage:

“Oh, my dear, dear aunt,” she rapturously cried, “what delight! what felicity! You give me fresh life and vigour. Adieu to disappointment and spleen. What are young men to rocks and mountains? Oh! what hours of transport we shall spend! And when we do return, it shall not be like other travellers, without being able to give one accurate idea of anything. We will know where we have gone—we will recollect what we have seen. Lakes, mountains, and rivers shall not be jumbled together in our imaginations; nor when we attempt to describe any particular scene, will we begin quarreling about its relative situation. Let our first effusions be less insupportable than those of the generality of travellers.”

Notice that Lizzy is at pains to explain they will properly appreciate the landscape,unlike the “generality of travellers.” It was felt that most poor souls lacked the refinement to truly grasp the sublime.

Philosophers dwelt at length on the sublime, particularly German philosophers including Kant, Schopenhauer and Hegel. And artists started painting mountains in new ways.

Mountains had appeared in art all along, although usually in the background. Leonardo da Vinci created marvelously mysterious mountains:

Leonardo da Vinci, Detail from "The Virgin of the Rocks" (London version), 1498-1508

But with Romanticism, landscapes became increasingly important–and increasingly dramatic. Previous artists painted domestic scenes of land tamed by agriculture; Romantic artists painted wild, wondrous landscapes of mountains soaring–even erupting:

[image error]

J.M.W. Turner, "The Eruption of the Soufriere Mountains in the Island of St. Vincent, 30th April 1812," 1812

Gerhard von Kügelgen, "Portrait of Caspar David Friedrich," ca. 1810–20

The ultimate Romantic artist was undoubtedly Caspar David Friedrich. (It’s not clear if he really had such a piercing gaze or simply liked to think he did.) Friedrich is all about the subline. He routinely paints dramatic landscapes of mountains, oceans or barren hillsides. Sometimes ancient ruins haunt the scene–the Romantics adored ruins, particularly Gothic ones. (The contemporary idea of being Goth–that is, dark, emo, moody–can be traced directly to the Romantic love of all things Gothic–or Gothick, as the novelists spelled it. Jane Austen would have understood Gothic to mean old, creepy, mysterious, emotional, and dark.)

Against the landscape, one or two human figures stand in contemplation, dwarfed by the scene before them. They are caught in appreciation of the sublime.

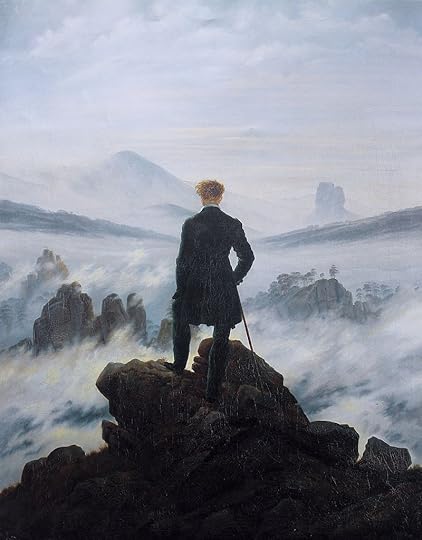

Caspar David Friedrich, "Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog," 1817

This is a vast subject, and I’ve only touched on it. American artists, for example, deserve their own discussion of how they painted the landscape of the West. If you’re curious, there’s a classic text on the Romantic discovery of mountains called Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory by Marjorie Hope Nicolson from back in 1959; you can read a large portion of the text online.

The temperatures are falling to reasonable levels here in Texas, and we won’t go back to the mountains until next year. It’s lovely to see traditions continue; my son now has “his” mountains outside of Jemez Springs in Northern New Mexico, where we’ve stayed the last several years with family.

But remember the next time a landscape makes you catch your breath and you stand still in wonder: Voltaire would have walked on by. Thank you, Romantics, for giving us the mountains.

June 13, 2012

The troubled eye of Monet

So I have an appointment with the eye doctor tomorrow, which I am awaiting with 90% relief and 10% trepidation. Relief predominates because, dudes, I desperately need new glasses. The squinting has gotten out of control.

The trepidation is mostly related to what I know is going to happen: the doctor is going to tell me that I need a new kind of glasses, the kind that begin with “bi” and end with “focals.” Now, it is simply not possible that I am old enough to need bifocals. Yes, technically, I’m over 40, but only in the sense that my birth was more than 40 years ago. I’m not actually in my 40s. That’s simply not possible.

There’s another tiny bit of trepidation to which I have to admit–a wee bit, a frisson if you will, of angst that my eyes might be troubled more than simply by myopia, astigmatism and that whole over-40 business. I come from a family with eye problems, both macular degeneration, which can be treated, and a weird genetic condition that can’t. We don’t know if I have the weird eye thing, it could never trouble me my entire life, but it’s scary enough that I go to an MD for my eye exams, not the optometrist at the mall.

Because, my friends, seeing is cool. I am pro-sight. I like looking at things. I kinda do it for a living, even. It’s hard to imagine writing about art if you couldn’t look at it.

Which leads me to Monet. Because if you think it’s hard being an arts writer with eye problems, imagine being an artist.

Let’s dispel some myths first. No, Monet did not paint the way he did his entire life because he had bad eyesight. When he was a young man, his eyes were perfectly fine. Check out this early painting of Monet’s future wife, which is clear and sharp and not blurry at all.

Claude Monet, Detail from "Camille (The Woman in the Green Dress)," 1866

The “fuzziness” of Monet’s style was deliberate and conscious. Monet was interested in atmosphere, light, space, air. He studied the way light revealed different colors under different atmospheric conditions, and the “blurriness” of his works was his way of representing that light and color.

Claude Monet, "Impression, Sunrise," 1872 (Click for larger image.)

This painting from 1872 (which, incidentally, gave the Impressionist movement its name) isn’t intended to be a detailed, sharp-edge depiction of boating in a harbor. It’s an impression of the effect of a sunrise on a foggy, cloudy setting.

Monet’s eyesight only became a problem late in his life, when, in his 70s, he began to develop cataracts. Today this wouldn’t be an issue. Cataract surgery is a quick out-patient procedure that you recover from in a day. Not so in the early 20th century. While surgery was available, it was painful, required a long recovery, and posed substantial risk.

Monet was first diagnosed with cataracts in both eyes in 1912, at the age of 72, but the condition had begun affecting his vision for at nearly a decade. Art historians and eye experts have traced a steady change in his color palette starting around 1905. He moved away from blues and greens. His canvases became dominated by reds and yellows, often pure pigments. This is consistent with the visual effects of cataracts, which desaturate colors and give all objects a yellow cast.

At his prime, Monet was a brilliant colorist—sensitive, subtle, delicate. Look at the incredibly blending and tone of this work:

Claude Monet, "Water lilies," 1908

Compare it to this:

Claude Monet, "Water lilies," 1923

It’s . . . horrifying. Red smudges with egg yolks. And terribly, terribly sad.

Another comparison—here’s Monet’s famous painting of the Japanese bridge over the lily pond at his house in Giverny:

Claude Monet, "Water Lily Pond," 1897

And the same scene a few years later:

Claude Monet, "Water Lily Pond," 1923

Monet realized what was happening. He considered giving up painting altogether and destroyed some of his canvases. Friends urged surgery, but he feared the results. Mary Cassatt, a long-time friend and colleague, had had cataract surgery on both eyes and been left essentially blind. Finally in 1923 he agreed to surgery on his right eye.

The results were mixed. Monet no longer saw the world as yellow but as blue—everything had a bluish cast. He realized this himself when he found he was going through blue paint faster than any other color. Here’s another version of the bridge from this last period:

Claude Monet, "The Japanese Bridge," 1924

Monet never consented to surgery on his left eye–it was simply too risky.

Monet wasn’t the only artist with vision troubles. Cassatt I’ve already mentioned. Degas’ vision began to decline even earlier than Monet’s, and from his 40s on he struggled with his sight. He died in near blindness.

I’m really not worried about my sight—I’m visiting the MD out of an excess of caution. It’s the kind of thing I might fret about at three o’clock in the morning, but generally I’m confident I have years of fantastic art-viewing ahead of me. Albeit in—oh, I can hardly bear to say it—bifocals.

As for Monet, I have to admire his persistence. He didn’t give up. He was an artist, and even in his literally darkest days, he made art. It would have been easy to throw away his brushes, go to bed and pull the covers over his head. I admire his commitment to the act of creation. Cezanne said of Monet that he was “only an eye—but what an eye!” How tragic that those eyes failed him in the end.