Elizabeth Lunday's Blog, page 8

January 31, 2012

The mysterious Bella Principessa–a knotty problem

This weekend I finally got to sit down and watch PBS's Nova on the DVR and thoroughly enjoyed the episode on a brewing art history controversy. The question: is this drawing by Leonardo da Vinci?

Young Girl in Profile in Renaissance Dress or "La Bella Principessa"

I won't go through the entire debate–you can watch the episode (at least for now) online or read the excellent summary by Hasan Nizazi at his site Three Pipe Problem. The short version is that the drawing, in chalk and ink on vellum, was sold at auction as a 19th-century German drawing. However, several scholars and collectors have proposed that it is a lost work by Leonardo da Vinci. The Nova episode does a good job of setting out the debate, although it leans heavily toward endorsing the view of the painting's advocates. It's darn convincing, in fact. My impression from reading online is that, for Renaissance experts, the case is still very much in the air, with more scholars refusing the authenticity of the work than accepting it.

The stakes are so high, Leonardo's name so big, and the money involved so stupendous that it will take a slam-dunk to convince everyone. I'm not the least bit qualified to offer an opinion. If it isn't by Leonardo, it's got to be a very clever fake; someone would have had to go to a lot of trouble. Tiny points have such an Leonardo-esque ring to them. Look at the details of the eyes, the hair. They're lovely, delicate, even exquisite. Even the oddity of the format–chalk and ink on vellum is a really weird combination–has the sort of experimental perversity that smacks of Leonardo. The man was never content to do things as they had always been done or as others did them.

One point that the documentary didn't go into but that I thought was interesting was the detail on the woman's sleeve:

I fiddled with the color and contrast to emphasize the detail of the knotwork. One thing that we know about Leonardo is that he loved designing intricate knot patterns.

Leonardo da Vinci, Ceiling of the Sala delle Asse, 1498

Look at the detail of the intertwining branches from the ceiling of the Sala delle Asse, a hall that he decorated during his time in Milan–just a few years after he is supposed to have completed La Bella Principessa. Here's another example:

Leonardo da Vinci, Ceiling of the Sala delle Asse, 1498

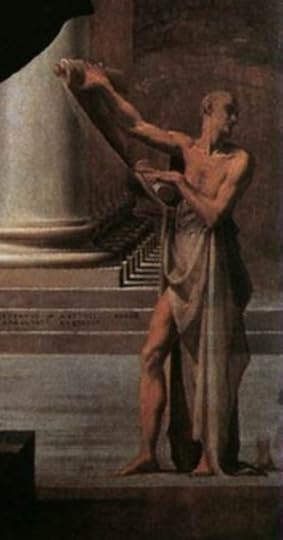

Leonardo's obsession with knot designs was famously recorded by Georgio Vasari, said (not very flatteringly–he found it baffling that the artist would "waste" his time so many things other than painting):

He even went so far as to waste his time in drawing knots of cords, made according to an order, that from one end all the rest might follow till the other, so as to fill a round; and one of these is to be seen in stamp, most difficult and beautiful, and in the middle of it are these words, "Leonardus Vinci Accademia".

Sketches of knots show up in the notebooks, and several were copied and printed. The original of one magnificent example has been lost, but the printed copy is believed genuine:

Knot design after Leonardo da Vinci, 1490-1500

(For another gorgeous knot design, check out this one at the British Museum.)

Of course I'm not the first person to notice the knot design on the disputed painting; scholar Martin Kemp notes the similarity as well, and he, unlike me, actually knows what he's talking about. And it hardly settles the debate. While the use of a knot design can be used to support Leonardo's authorship, one could also argue that a really clever forger would employ exactly such a characteristic element.

Nevertheless, the knots are beautiful. And the girl is beautiful. I have to admit the first time I saw it my reaction was "Don't be ridiculous–that's not a Leonardo." But now I look at it and think "Well, of course that's a Leonardo." What's almost impossible at this point is to simply look at the drawing and see it for itself, leaving aside the question of its creator.

So what do you think? Is it Leonardo–or isn't it?

January 25, 2012

They do it with mirrors

Edouard Manet was born last Monday, and thinking about Manet got me thinking about his last masterpiece, which got me thinking about mirrors.

A mirror provides the background to A Bar at the Folies-Bergere and adds great mystery to this captivating painting. But Manet wasn't the first artist to have fun with mirrors in his art.

It all started–as did so many things–with Jan van Eyck, the great Flemish painter of the Renaissance. Van Eyck is credited with introducing or at least popularizing the use of oil paints in Northern Europe and mastering linear perspective. His paintings are masterworks of fine detail and painstaking composition.

He also, I think, had a sense of humor. Take this, one of his most well-known works:

Jan van Eyck, "The Arnolfini Portrait," 1434

I love the details. Notice the metal of the chandelier, the droop of the woman's gown, the fluff of the little dog's fur. The work depicts the Italian merchant Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his wife and is presumed to be a wedding portrait. The woman is not, as one might think, pregnant; having that much fabric in her gown was the fashion as well as a sign of wealth, since only the rich could afford such long dresses that they had to be hiked up to walk.

The sly touch of the painting is the back wall. Look directly between the couple and you see first writing and then a mirror. The writing is it's own quirk; it is van Eyck's signature, one of the first in Western art. It reads "Jan van Eyck was here 1434." The mirror, however, is the most fascinating element since it reflects, well, us. It is positioned to reflect the viewer's position exactly. What does it depict?

Jan van Eyck, Detail from "The Arnolfini Portrait," 1434

Behind the couple and the open window, both distorted by the convex shape of the mirror, very faintly you can see two figures standing in the doorway, right where we, the audience, would be standing. It's hard to tell from a web-quality image, but one of the figures is raising his hand as if to say hello. Art historians conjecture that one of the figures is the artist van Eyck himself, inserting himself unobtrusively into his own work. (Isn't the detail on the mirror frame magnificent? The circles around the frame show scenes from the life of Christ, barely visible and probably ignored by most viewers.)

Another artist to have fun with mirrors was Diego Velazquez in his masterpiece of 1656, Las Meninas. He knew The Arnolfini Portrait and was likely inspired by it:

Diego Velazquez, "Las Meninas," 1656

So much going on here. Basically, the work shows one of the crown princesses of Spain, the Infanta Margarita, surrounded by her maids, chaperone, bodyguards, dwarves, and dogs. On the left, we see the back of a picture frame and the artist himself, Velazquez, holding a brush and standing back to get a view of his work.

In the very back against the wall we see a mirror. Based on where the mirror is positioned, just as in The Arnolfini Portrait, the viewer–us–would naturally be what is reflected. Except take a closer look:

Diego Velazquez, "Las Meninas," 1656

The two shadowy yet glowing figures–notice how their pale faces stand out against the dark wall–are the king and queen of Spain, Philip IV and Mariana of Austria. (Check out this painting by Velazquez of the king should you have any doubts.)

How to interpret this? Many art historians believe the work depicts a moment in a time, a sort of snapshot, of the court. The artist, a favorite of the king, is at work on a portrait of the royal couple. The charming princess comes for a visit with her courtiers. The mirror reflects the king and queen smiling at their daughter as they pose.

Except, except . . . putting any ordinary viewer into the exact position of the king would have been a shocking breach of protocol, like letting a peasant borrow a crown. Velazquez not only survived by thrived at the Spanish court for decades and would have known better.

So what is going on? Maybe, some suggest, the mirror reflects not the actual king and queen but the painting of the king and queen. There's something to this. The mirror is actually offset slightly to the left, not in the direct middle of the painting, as is the frame. Or maybe, others propose, the painting was intended for the private view of the king, or at least the privileged view of the king. It was his work of his family, and any other audience taking his position was unimportant.

Maybe the meaning is more metaphorical than literal. Maybe the mirror reflects not the real image of the king and queen, but the idealized reflection of the ideal king and queen, thereby paying a subtle compliment to Philip. Maybe Velazquez is playing with the idea of the painting as a mirror on nature. If a painting is supposed to reflect reality exactly, then what does a reflection of a reflection do? (Or even a reflection of a reflection of a reflection, if the mirror is supposed to depict the unseen image on the artist's canvas instead of–or in addition to–reality.) Many critics make much of the fact that the artist, Velazquez, is looking directly at us and/or the king and queen; is the entire work conjured up by his brush, with the artist the master of illusion greater than reality? You can go around and around, and pretty soon art historians are making statements about how "the painter achieves a reciprocity of gazes that makes the interior oscillate with the exterior." Personally, I don't think there's any one explanation; I think Velazquez was brilliant, and brilliant artists sometimes confound their audiences on purpose.

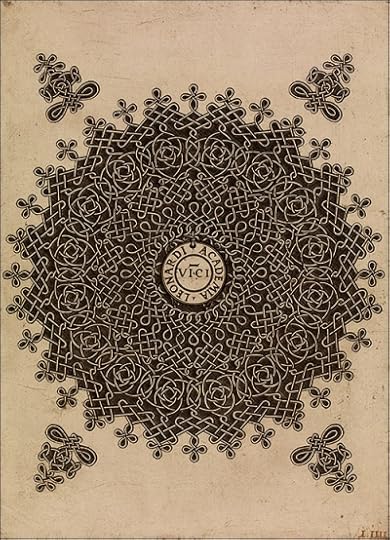

Which brings us to the most confounding mirror image of all, Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergere, which was inspired by both van Eyck and Velazquez:

Edouard Manet, "A Bar at the Folies-Bergere," 1882

It's so deceptively simple at first glance. We see a well-dressed girl behind the bar at the fashionable nightclub. She rests her hands on the marble bar-top, while behind her a mirror reflects the busy club. Look in the upper left corner to catch a glimpse of the famous trapeze on which acrobats performed above the patrons' heads; enormous chandeliers flood the room with light. We can tell that the background is a mirror because we can see its gold frame just above the bar and about the level of the woman's hips.

Except–that can't be right. If this were a mirror, the woman's black gown would be reflect directly behind her. Instead, we see her rear reflection off to the right. Moreover, this reflected woman is leaning forward slightly and talking to the top-hatted man. Where did he come from?

Perhaps what we're seeing are two separate moments in time, one now (the woman alone, her face abstracted, closed, darkly pensive) and one earlier (talking to the man.) It was known that girls at the Folies Bergere were often prostitutes, or at least presumed to be so; some critics believe the man is propositioning the woman. She is as available as the wines and beers on her counter. Her later expression reflects her ambivalence about the encounter.

I have some quibbles with this interpretation; the man looks pretty darn neutral for someone soliciting sex. If Manet had intended him to be leering, surely he would have given us some clues.

He gave us other clues:

Edouard Manet, "A Bar at the Folies-Bergere," 1882

Manet was an excellent student of art history; he knew his symbolism. Roses and oranges have had meaning for centuries. Oranges were symbols of purity, chastity and generosity, while roses were symbols of love and purity. Both were traditionally associated with the Virgin Mary. So here in this crowded, glittering bar, which seems so dated to us but would, to Manet's audience, been completely modern and of the moment, we have a young woman, flowers at her breast, oranges and roses before her, a modern Mary–contemplative, isolated, beautiful.

To me, the image and the reflection don't have to take place at different times; they could just as well reflect different mental states. Anyone who has ever worked retail–anyone, in fact, who has found him- or herself in the middle of a crowd–has had the feeling of inner withdrawal, of internal retreat. Suddenly you are separate from the scene, observing it and yourself within it, while you continue to interact. I think Manet is painting an internal moment of abstraction, perhaps revealed by a split-second expression between customers. And his subject is a contemporary Madonna, singled out by the artist's vision but otherwise just a girl at a bar. Did he go the Folies Bergere and see her pausing for a moment, a fleeting look crossing her face that arrested his attention? Did he alone recognize her uniqueness and her beauty?

Three mirrors, three mysteries. What do you think? When you look at these reflections, what do you see?

January 19, 2012

Does an apple move?

I had every intention of writing a thrilling post on Cezanne today–it's his birthday, after all! But The Headache has come back and today I have the writing chops of a chipmunk. So I'm borrowing from my own words, from the chapter of Secret Lives of Great Artists on Cezanne.

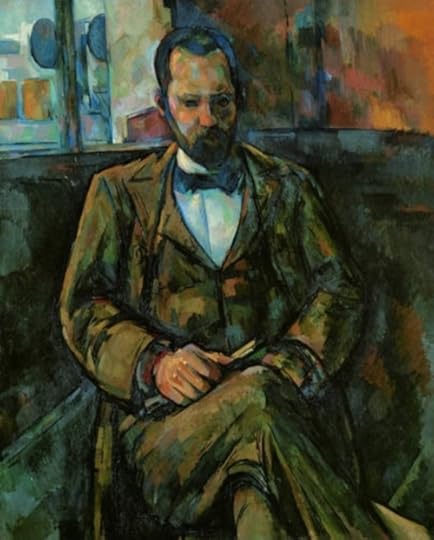

It's a story about the creation of this painting:

Paul Cezanne, "Portrait of Ambroise Vollard," 1889

Cezanne was particularly fond of painting still lifes such as his famous series of apple paintings. One of the reasons was that human beings were so much more trouble. He demanded that his models sit perfectly still, without talking, for hours on end. When painting a portrait of dealer Ambroise Vollard, Cezanne insisted Vollard sit on a kitchen chair atop a rickety packing case from 8 until 11:30 a.m. without a break. One day Vollard dozed off and lost his balance–the dealer, the chair, and the packing case all crashed to the floor. Cezanne was infuriated. "Does an apple move?" he shouted.

Henceforth Vollard drank massive amounts of black coffee before his sittings, but after more than one hundred sessions Cezanne abandoned the project. When Vollard asked if the artist was happy with the work, Cezanne's only reply was, "The front of the shirt isn't bad."

Not bad, indeed. Happy birthday, Paul.

January 18, 2012

The Headache

I had The Headache yesterday. This was my grandmother's phrase–"the headache," as if there was only one in the entire world. "Have you got The Headache?" she would ask. Or, "Poor Ruth's down with The Headache again, poor thing."

As a kid, I thought this was funny, as if "The Headache" was like the proverbial single fruitcake that has been exchanged over and over since the beginning of time. Perhaps it's like hot potato, with every sufferer trying desperately to pass it along. As an adult, I think she may have been more wise than I realized.

I've had migraines for years–I am, in the terminology of the condition, a migraineur, something I can't imagine ever calling myself with a straight face. Nevertheless, I'm in good company. People with migraines find each other out at parties and in offices, and I also notice My People in books and biographies. I can't help it. We have a bond, however tenuous.

In fact, my entire opinion of The Sound and the Fury shifted the moment Jason gets a migraine. If you've read the book, you hated Jason–I don't know anyone who doesn't hate Jason, he's despicable. But gasoline fumes give him migraines, and as I read the last section as he tries to drive (on a foolish and fruitless errand) as the pain increases to the point it almost blinds him, I felt only pity. Go lie down, I wanted to say. Go rest. (And then rent an apartment or something–you need to get out of that house.)

It seems like there would be good descriptions of migraines in print, considering it's such a common condition, but I haven't found many. Some of the most interesting attempt to describe the auras that some migraine sufferers experience at the start of a headache. Auras are visual disturbances including flashes of light, blind spots, zig-zag lines and even visual hallucinations–no one knows what causes them, although it might have something to do with pressure on the optic nerve, but then they don't know what causes migraines either. (I don't get auras, so I can't speak here from personal experience.)

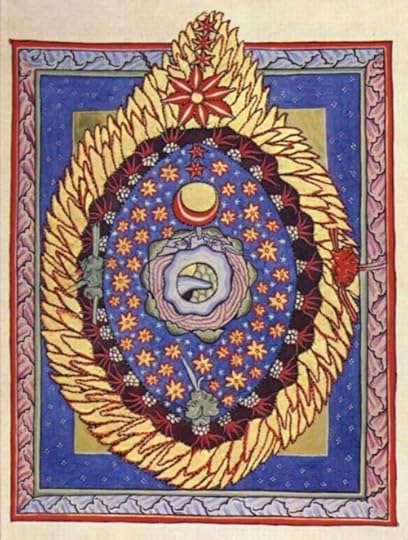

In A.S. Byatt's Possession, two separate women have migraines, and both seem to have auras, one the most common visual kind: "Things flicker and shift, they are indeed all spangle and sparks and flashes." Some artists have attempted to depict the effect of auras, including Hildegard of Bingen. Hildegard (1098-1179) was an abbess, composer, theologian and mystic, and her visions have been proposed to have been inspired by (or accompanied by) migraines. Take this illustration from her book Scivias, in which she describes her visions:

Hildegard of Bingen, Illustration from "Scivias," ca. 1151-1152

Experts say elements of this painting–including the flashing stars, narrowing point and black spots–are typical of an aura.

Sir John Tenniel, Illustrations from "Alice in Wonderland," 1864

Scholars propose another migraine patient, Lewis Carroll, aka Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, drew on his experience with auras to describe the physical transformations of his heroine. He even gave a syndrome its name, Alice in Wonderland Syndrome, in which people experience rapid and disturbing alterations of the size of the body or external objects. An arm might suddenly balloon to terrifying proportions, then just as rapidly diminish to a microscopic point. This is, apparently, fairly common during aura. (This happened to me once, not during a migraine but as a child when I had a high fever. It was terrifying.)

But auras are only the beginning of the headache. The pain comes next, and here words seem to fail almost everyone. People talk about "steel bands" around their foreheads. "Half my head," says a character in Possession, "is merely a gourd full of pain." (Many migraines only affect half of the head, which, when you think about it, is really weird.) Rudyard Kipling said in a letter:

Do you know what hemicrania is? It is a half headache and I have been having one for four days now. One half of my head, from the top of my skull to the cleft of my jaw, hammers, bangs, sizzles, and swears while the other half, serene and content, looks on at the agony next door.

One element of the migraine that comes up repeatedly is the sense of timelessness that accompanies it. "It is curiously impossible–once into this state–to imagine ever issuing out of it–so that the Patience required to endure it seems to be a total eternal patience," writes Byatt in Possession.

I understand this completely. I always feel as if The Headache has always been there, only I am just now entering it again. It never stops–it has no beginning or end, it simply is. It is, in fact, The Headache, eternal, unchanging, unrelenting. One migraineur (what a pretentious-sounding term!), Emily Dickinson, described it thus:

Pain has an element of blank;

It cannot recollect

When it began, or if there were

A day when it was not.

It has no future but itself,

Its infinite realms contain

Its past, enlightened to perceive

New periods of pain.

As such, patience is part of the cure. Sometimes you just have to lie there and have that headache. Now, of course, there are wonder drugs that directly treat migraines and are, in my opinion, miraculous. I don't think I realized how miraculous they were until one day Imitrex, which had worked like a champ for years, suddenly quit having any effect on my headaches. I was back in the days when a migraine meant three days lying in the dark. God, I hated it. I fought it. I would lie there trying to exert some control over this damn pain, all to no avail, until finally I would realize the only solution was to give in and let The Headache win. At least that way I would eventually fall asleep.

(Fortunately, I was able to switch to Zomig, and now I'm under control again.)

For all the writing and art, I still don't feel as if someone who had never had a migraine could have any sense of what it was like by reading about it. In a sense, this is true of all pain–we can only resort to metaphor and analogy. Perhaps this is related to the fact that we can't truly remember pain. (Speaking as someone whose @#$% epidural failed, I can only be thankful for this. Some moments I would rather not remember.)

Virginia Woolf

Which brings me to one of the best quotes about migraines, from someone who knew them well: Virginia Woolf. For all of her brilliant use of language, even she fell short when describing the experience of migraine.

"English," she wrote, "which can express the thoughts of Hamlet and the tragedy of Lear, has no words for the shiver and the headache… Let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry."

The Headache has abated. In fact, the pain was gone within an hour or so, thanks to the wondrous Zomig, although the lethargy and dopiness continued for the rest of the day. Migraines are like storms in the brain, similar in some ways to epileptic seizures, and they disrupt numerous systems. It takes time to reset the delicate balance of chemicals and neurotransmitters and electrical impulses, and I've learned there's no point in resisting this period of quiet. It is The Headache's due.

And now it has moved on. My sympathies, friend, to whoever landed The Headache next.

January 12, 2012

Looking at Art: John Singer Sargent's "Gassed"

I had hoped to do an entire post on John Singer Sargent today–his birthday–but alas! between a doctor's appointment and a spelling bee (my son, not me) (which is good–he's a better speller than I am) I don't have time.

So I'll just mention here one work that I think is hugely significant. Sargent made his fame with his portraits–his vivid, personality-filled portraits with their luscious skin tones and gorgeous fabrics. Is there anything richer than the velvet of Madame X's gown? His work is crammed with depictions of the wealthiest, most comfortable people–he was part of their luxurious milieu.

So when we come to this painting, it's a shock:

John Singer Sargent, "Gassed," 1919

I wish I could make it wider. Do a quick Google search for a bigger image to get a better sense of it. The actual painting is 20 feet long, so it's really impossible online to convey it's real impact.

Sargent was commissioned by the British War Memorials Committee to visit the Western Front in 1918. Near Arras and Ypres, he saw scenes such at these, the wounded and the blind lined up together. These men have suffered from a mustard gas attack, which burned their eyes and skin. They traveled to aid stations in lines, one holding on to the other so they wouldn't fall. Another group of men is lined up in the near distance as the weary sun sets behind them.

By 1919, Sargent was dismissed as past his time. His art was of another era, before modernism, before Cubism and Fauvism and all the other -isms. His very mode of work was dated–the society portrait was a relic of an age of unlimited wealth, of American girls marrying British aristocrats, of oil barons and steel barons and rail barons and unbusted trusts. By 1919, the world had changed.

You can quibble with the painting. Is it, perhaps, too soft-focused? Too gauzy? Is there not enough blood? Is it just a smidge too pretty?

You can argue that Sargent was a far better portrait painter than war artist.

You can argue that Sargent was painting a new scene of a new age of horror with the tools of yesterday. That the agonies of the 20th century required a new painting technique–that "Guernica" is better painting not only because it captures the shock of war but that it captures it in a mode appropriate to its era.

I'm willing to accept most of these arguments. Most. But I will still assert that this is a powerful, haunting painting–that the line of men against the sky evokes a religious procession that hearkens back to the sculpture of ancient Greece. These men are a frieze of horror, blinded, coughing and despairing. Some are going to their deaths.

I can't write about this subject without recalling the poem that describes so horribly and vividly the effects of gas, "Dulce Et Decorum Est" by Wilfred Owen. Owen was a man of his time, writing poetry suited to his time–but still, Sargent had something to offer.

Dulce Et Decorum Est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of disappointed shells that dropped behind.

GAS! Gas! Quick, boys!– An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And floundering like a man in fire or lime.–

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,–

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

January 11, 2012

Looking at Art: "Madonna with the Long Neck"

Imagine that you've got this big brother. He's AMAZING. In fact, he's the most remarkable guy anyone has ever met. He's handsome. He's brilliant. He's fascinating. Everyone you know adores him. No one ever shuts up about him.

You hate his guts.

How can you not? You're coming along, trying to do your own thing, but no matter how hard you try or how clever you are, HE will always be there ahead of you. What can you do except try to strike your own path as be as individual as possible? You're going to rebel. You don't have much choice.

This was, approximately, the situation of Italian artists in the generation immediately following the High Renaissance. Let's say you were born in 1503, about fifty years after Leonardo da Vinci, twenty-five years after Michelangelo and twenty after Raphael. By the time you take up brush and palette, these guys have completely reinvented art. They've perfected all that the previous hundred years of masters have been striving for. You want to throw up your hands in despair.

Parmagianino, "Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror," ca.1524

Pity, then, poor Parmigianino, aka Girolama Francesco Maria Mazzola, born on this date in 1503. (He came from the city Parma, like the cheese.) He was raised by artist uncles and showed significant talent as a young man, but by the time he arrived in Rome, the masterpieces of Michelangelo and Raphael were complete and Parmigianino had to figure out what on earth was left for him to do.

What he did was help invent Mannerism.

It's remarkable just how much art was created in reaction to what came before it. Impressionism was a reaction to Academic art, as was Pre-Raphaelite art; Post-Impressionism a reaction to Impressionism, and so on. Mannerism reacted against High Renaissance art by building on some elements and rejecting others. It took as its starting point the elegance and beauty of the Renaissance masters but discarded their naturalism in favor of a heightened, mannered approach.

It's a highly self-referential form of art, always looking over its shoulder, always borrowing from big brother while at the same time trying to do something new.

The epitome of Mannerist art is Parmigianino's art–and a truly bizarre painting–is his famous "Madonna of the Long Neck."

Parmagianino, "Madonna with the Long Neck," 1535-40

Of course, that's not what Parmagianino called it. A more formal name would be "Madonna and Child with Angels and St. Jerome." But look at that woman's neck. The nickname was inevitable.

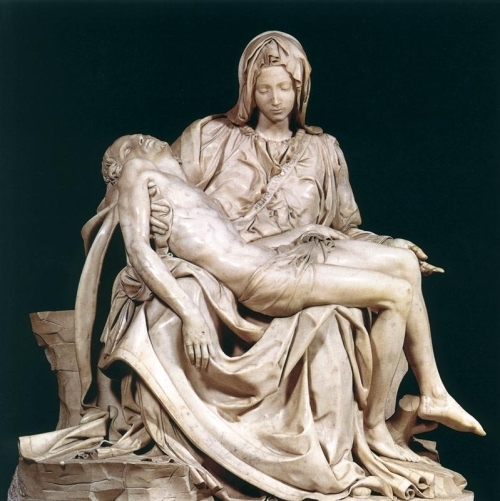

On the one hand, Parmagianino is drawing on clear Renaissance models. The Virgin's position–her tiny head on top of monumental hips and wide knees–echoes Michelangelo's Pieta:

Michelangelo, "Pieta," 1498-99

Notice how Michelangelo turns Mary into a sturdy pyramid to support the weight of her son. Parmagianino makes his Mary into more of a diamond, with her wide lap positioned to support the weight of that sprawling baby. Look, as well, as at the droop of the Christ Child's left arm in the Parmagianino and compare it with the hanging arm of Christ in the "Pieta." This is a deliberate way of reminding us of the end of the story at the beginning–the Nativity leads inexorably to the Crucifixion. It's also a way of paying homage to what came before.

(Parmagianino did this a lot. Look at this detail from his "Vision of St. Jerome:"

Compare it to Leonardo's "John the Baptist:"

Yeah. Pretty obvious.)

At the same time, Parmagianino is taking art in an entirely new direction. Look at the neck of the Madonna–that distinctive, swan-like neck:

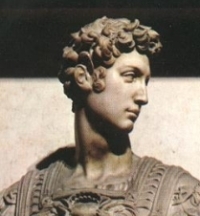

On the one hand, it is a bit of a quote of the twisting neck that Michelangelo gave Giuliano de' Medici:

On the other, it's completely exaggerated and impossible. She must have four or five extra vertebrae in there. The same goes for her fingers–those long, seemingly unjointed fingers. Neither the fingers or the neck are based on real life, on real fingers or real toes. They are instead an ideal of fingers, an ideal of the long, elegant neck. The reference is not to reality but to elegance and to art itself.

The same goes for the baby, who is enormous and in imminent danger of slipping off his mother's lap. I have wondered before if artists ever looked at actual babies before painting their children, cherubs and putti, and in the case of Parmagianino the answer is irrelevant. The baby has nothing to do with real babies but with the ideal of babies in Renaissance art and how that ideal can be exaggerated and emphasized.

The composition of the painting is perplexing in its own right. Notice how all the angels are crammed into one corner while St. Jerome is all alone in another. It's unbalanced. An artist of the High Renaissance would never have composed a work this way. They went for pyramids, triangles, squares–simple, balanced shapes that convey stability. There's a weird precariousness in Parmagianino's composition, and it's deliberate. As the artist historian E.H. Gombrich noted, "He [Parmagianino] wanted to show that the classical solution of perfect harmony is not the only solution conceivable."

The St. Jerome bit is definitely odd:

Presumably he was included in the painting as a requirement of the commission–that was common. Jerome, an early Christian scholar famed for his translation of the Bible, is depicted in his traditional rags that he wore while living in isolation in the desert. He's holding a scroll to symbolize his writings. That he has nothing to do with the rest of the scene isn't really the odd part. It's common to have groups of saints surrounding the Madonna and Child, all representing different eras, all garbed in their traditional clothes and carrying their traditional items. (Someday I'm going to do a post on St. Stephen, who wanders about forever with arrows sticking out of him.) What's strange about the image is the scale and proportion. He's impossibly far away from the Madonna, standing by the row of pillars that are impossibly tall. It's baffling.

Mannerism didn't last long as a movement. Caravaggio came along with his dramatic Baroque style and blew Mannerism out of the water. But the style is significant in part because of what it presages. Mannerism is the most modern of early art movements in the way it is based on reaction as well as in its self-referentiality. It is the first art movement where the primary focus is on art as art, not as a depiction of an outside reality.

And really, what else could we expect it to do, with the High Renaissance as its big brother?

January 5, 2012

Christmas Art Part III: Adoration of the Magi

Bet you thought Christmas was over, huh? In fact, the day is over, but the season is not. In Christian tradition, the season doesn't end until January 6th, aka Twelfth Night or Epiphany, the traditional date that the Three Wise Men visited the Baby Jesus.

Typically today, we slap the Wise Men around the manger on Christmas night–at least we arrange them and their requisite camels around the Nativity Scene. But, look, it took them awhile, what with looking up Herod and having dreams and finding forage for the camels. Have you ever traveled via camel? Well, I haven't either, but one imagines it isn't exactly swift.

As with all other aspects of the Christmas story, the Adoration of the Magi became layered with details that have nothing to do with the Bible. The whole bit about them being kings, for example, isn't Biblical at all. But the early church declared them kings, and furthermore gave them names: Balthasar, Caspar and Melchior. In time, the three kings came to represent the three known parts of the world, with Balthasar as a Moor or African, Caspar as Oriental (what we would now think of as Middle Eastern, anything further East being the most misty of rumors) or Persian and Melchior as Western. The symbolism was of the entire world coming to pay homage to their new king, and the positioning of the figures was that of a feudal subject giving obeisance to his lord.

This best part of this interpretation, to artists, was the fantastic opportunity it gave them to make the kings glorious and glamorous.

Fra Angelico and Fra Lippo Lippi, "The Adoration of the Magi," ca. 1490

Look at the gorgeous clothes Fra Angelico and Fra Lippo Lippi give their kings, as well as the vast retinue that accompanies them. Horses! Camels! Attendants! Gawking villagers! It's magnificent. For artists, these paintings were an opportunity to show off their handling of large scenes and enormous details.

Other details that show up in numerous Adoration paintings–particularly during this period in Italy–are also apparent here. For one thing, you'll almost always find a peacock somewhere in an Adoration painting.

Fra Angelico and Fra Lippo Lippi, Detail from "The Adoration of the Magi," ca. 1490

In the Medieval period, peacocks were believed to have incorruptible flesh–that is, the flesh of the peacock would never decay. This is, of course, simply not true–leave a dead peacock lying around and it will rot like anything else, but Medieval science isn't known for its accuracy. Nevertheless, the peacock became associated with Christ, because Christ was also incorruptible in the sense that after death he was resurrected. Just to remind you of the end of the story here at the beginning, artists frequently included peacocks.

Sandro Botticelli, "The Adoration of the Magi," ca. 1475

Another tradition was to place the stable in or near a ruin of some sort, which you can see in this Botticelli as well as in the Fra Angelico. Sometimes the ruin is explicitly Roman-looking, which gives you a hint to the meaning. The birth of Christ signified a new era of civilization, the Christian era, and the end of the previous Classical era, and representing this visually meant depicting the architecture of Rome in ruins. Historically, this is as much nonsense as the non-decaying peacock, since Roman architecture was still a going concern at Christ's birth, but again: this was an era not concerned with historical accuracy.

A few other points from this painting. See the old guy with his head on his hand behind Mary? That's Joseph. Medieval tradition always showed Joseph as an old man. The idea was that, as an eldery gent, perhaps even a widower, he would be content to let Mary remain a virgin, which in Medieval tradition, she did her entire life. A young man, they theorized, wouldn't have stood for such treatment. So Joseph usually shows up as a benign dottering figure in these paintings. At least in this one he's awake–often he's found snoring off in a corner.

The other cool thing in this painting is that Botticelli used the inclusion of the kings and their attendants as an opportunity to butter up some of his patrons. It was also an opportunity for the painting's sponsor, one Guasparre del Lama, a social upstart in Florence society where Botticelli worked. It's believed that del Lama requested Botticelli paint portraits of members of the powerful Medici family to demostrate his attachment to them. This would have been right up Botticelli's alley, as the Medici were his most important patrons.

Del Lama is likely the white-haired man in a blue robe looking at the viewer and pointing his finger. He's pointing at the man on the end in the orange robe who also looks at the viewer; this is Botticelli himself, working himself into the noble company.

And here is most important Medici, Lorenzo the Magnificent, literally looking down his nose at the scene. Behind him is Agnolo Poliziano, a prominent critic, scholar and poet and close friend of Lorenzo.

There are hundreds of treatments of the Adoration of the Magi–I'm only scratching the surface. Some of them have very odd elements:

Fiorenzo di Lorenzo, "The Adoration of the Magi," ca. 1490

Why the heck is the baby on the ground? This is bizarrrely common. Here's another one:

Robert Campin, "The Nativity," 1425

This is actually a Nativity scene, not an Adoration, but still: why is that baby on the ground?!?! Yes, he's divine, but couldn't you worship him on a less chilly and more hygienic surface? (Thanks to the wonderful folks at Ugly Renaissance Babies for introducing me to this fantastically weird work. And, yes, that is one ugly Renaissance baby.)

Even later Baroque works have their share of wtf moments, like this Rubens:

Peter Paul Rubens, "The Adoration of the Magi," 1624

It's pretty fantastic overall–the swirl of figures, the lush fabrics (the color is probably fantastic in real life), the matronly Madonna, the squirming baby. But the expressions on the faces of two of the kings are downright odd.

This guy seems terrified. It's a BABY! Run for your lives!!!!!!!

And this . . . . There are no words. What expression is that??? Outraged hobbit, maybe?

One last Adoration and then we can put Christmas behind us once and for all.

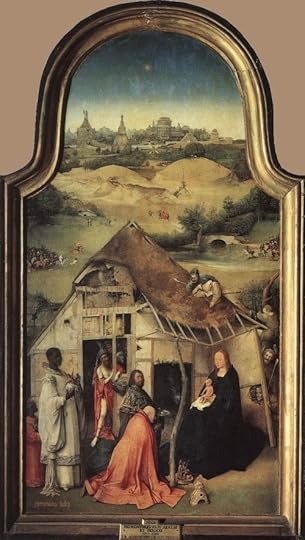

Hieronymus Bosch, "The Adoration of the Magi," ca. 1510

No Roman ruins or peacocks here–Bosch was working in Northern Europe, and those elements might not have made it to him. The stable looks like a pretty darn realistic stable. The details are fantastic and hard to see (check it out at the Web Gallery of Art where you can zoom in). For example, at the Virgin's feet is the gift of the kneeling king, a sculptured representation of the Sacrifice of Isaac, which was believed to prefigure Christ's sacrifice on the Cross. The embroidery on the collar of the second king depicts the Queen of Sheba visiting Solomon. A group of peasants has been attracted by the strange visitors; they peer around and through the stable on the right and even scramble on the roof.

The weirdest part of the painting is the man standing inside the stable. He's naked except for a crimson robe and odd crown. The figures behind him seem weirdly hostile. What the heck is going on? I'll just quote from the Web Gallery of Art explanation:

Because they stand within the dilapidated stable, time-honoured symbol of the Synagogue, these grotesque figures have been identified as Herod and his spies, or Antichrist and his counsellors. Although neither identification is quite convincing, the association of the chief figure with the powers of darkness is clearly suggested by the demons embroidered on the strip of cloth hanging between his legs. A row of similar forms can be seen on the large object which he holds in one hand; surprisingly, this can only be the helmet of the second King, and still other monsters decorate the robes of the Moorish King and his servant. These demonic elements undoubtedly refer to the pagan past of the Magi.

Not particularly satisfying, is it? But Bosch is known for his odd and vaguely sinister details–this is just another.

So enjoy Twelfth Night. Its celebration has never made much of an impact in America, but traditionally it was a time of parties, special desserts, and dancing.

And for the love of God, if you see a baby lying on the ground, PICK IT UP.

========================

One more thing: visitors to the site will see I've been doing a fair bit of mucking about, tidying up and generally spiffying. I hope you like it, and if you see anything weird or untoward, please let me know. I know enough about web design to be dangerous but not enough to be efficient.

And on that note,

Happy New Year!

December 20, 2011

Christmas Art Part II: The Annunciation

When we get to the Annunciation, we're in the realm of recognizable Christian art–particularly in comparison with the wacky Tree of Jesse depictions. Artists have loved this dramatic moment and have tackled it again and again through the years.

The story is taken directly from the Bible, from Luke 1:26-38:

. . . the angel Gabriel was sent from God unto a city of Galilee, named Nazareth, 27 To a virgin espoused to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David; and the virgin's name was Mary. 28 And the angel came in unto her, and said, Hail, thou that art highly favoured, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women. 29 And when she saw him, she was troubled at his saying, and cast in her mind what manner of salutation this should be. 30 And the angel said unto her, Fear not, Mary: for thou hast found favour with God. 31 And, behold, thou shalt conceive in thy womb, and bring forth a son, and shalt call his name Jesus. 32 He shall be great, and shall be called the Son of the Highest: and the Lord God shall give unto him the throne of his father David: 33 And he shall reign over the house of Jacob for ever; and of his kingdom there shall be no end. 34 Then said Mary unto the angel, How shall this be, seeing I know not a man? 35And the angel answered and said unto her, The Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the Highest shall overshadow thee: therefore also that holy thing which shall be born of thee shall be called the Son of God. 36 And, behold, thy cousin Elisabeth, she hath also conceived a son in her old age: and this is the sixth month with her, who was called barren. 37 For with God nothing shall be impossible. 38 And Mary said, Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to thy word. And the angel departed from her.

So what did artists do with such an inherently dramatic scene?

Icon of Annunciation, Church of St Climent in Ohrid, Macedonia, c. 14th century

They added a lot of extra stuff, for one thing. This Byzantine icon, for example, emphasizes the role of Mary as Queen of Heaven by positioning her on a throne.

Western artists usually emphasized Mary's wisdom rather than her divinity, and a tradition arose of having Mary interrupted while reading:

Simon Bening and assistants, Miniature from the Hours of Albrecht of Brandenburg, Flanders, Bruges, c. 1522-23

Mary is kneeling at a lectern, reading from the Old Testament. (In paintings where you can see the text, she is seen reading from Isaiah's prophecy of the coming of the Messiah.) This manuscript includes another standard feature of Annunciation scenes: the dove of the Holy Spirit spreading its light over Mary. This light was considered the, er, seed that impregnated her. Which is kind of weird. Anyway. The detail I love in this manuscript is the outer scene, which I think shows Mary on her way to visit her cousin Elizabeth. Apparently Gabriel went along to carry her purse.

Here's another reading Mary:

Melchior Broederlam, The Annunciation, The Dijon Altarpiece, 1393-99

I think what I love best about this painting are the absolutely Escher-like interiors. Perspective was only just being rediscovered, and clearly Master Broederlam was figuring it out as he went along.

Leonardo da Vinci continued the tradition of Mary reading in his version of the Annunciation from the 1470s:

Leonardo da Vinci and Andrea del Verrocchio, The Annunciation, ca. 1472–1475

Leonardo was a student in Verrocchio's workshop when he worked on this painting, and scholars can identify parts from both artists; the wings were later altered by another artist altogether. Mary's hair is marvelous, but the perspective of the lectern and Mary's knees is kinda wonky.

You'll notice the angel holds a blossom of lilies, one of the flowers traditionally association with Mary.

Sandro Botticelli, The Annunciation, ca. .1489-90

Botticelli features them prominently here. I love the graceful–although characteristically boneless–Madonna. Her expression is typically bland. The church emphasized Mary's acceptance of God's will, and artists' followed suit.

I mentioned the dove that often shows up in these works, like here in Perugino:

Pietro Perugino, The Annunciation of Fano, ca. 1488-90

Perugino positions God the Father in the circle above (holding, I think, the earth, and not, as one might assume, an orange) surrounded by creepy babies intended to be cherubim and seraphim. The dove is descending from God to Mary, who looks like she has a toothache.

But the best descending dove has to be that of Girolamo Santacroce–because he has company!

Girolamo Santacroce, The Annunciation, ca. 1540

It's a dive-bombing baby Jesus!

If that doesn't make you giggle, you have no sense of humor. I guess he popped into her womb from midair.

Annunciation paintings reached the height of popularity in the Renaissance, but that didn't stop Baroque artists from doing their best.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Annunciation, 1609

Rubens' Madonna is particularly queenly. She looks like she's granting a boon to a servant, not accepting the will of the Lord. Of course there are lots of frolicking angels. Rubens loved him some frolicking angels.

El Greco is, well, El Greco–like no one else ever.

El Greco, The Annunciation, 1596-1600

It's surreal–bizarre–nonsensical yet transformative. I would have to do a good chunk of research to begin to talk about what's going on. I get that the top section is heaven, with a band of angels playing joyfully. The dove and the angel break between the heavenly and the earthly spheres. But what are the floating head-things behind Mary? And what is lying at her feet? You've got me.

Religious art fell out of favor after the Baroque period, and Annunciation paintings are thin on the ground until they reappear in Pre-Raphaelite art.

John William Waterhouse, The Annunciation, 1914

Waterhouse painted this in 1914, which is extraordinarily late for a detailed religious painting–Picasso had been through several periods by then–but that was what Waterhouse did, so why stop? At least his Mary seems surprised.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ecce Ancilla Domini! (The Annuniciation), 1849-50

More than half a century earlier, Dante Gabriel Rossetti caused a scandal with his Annunciation. His adolescent Mary recoils from the angel and seems stunned by his message. Victorian audiences were horrified by the anemic, anexoric Virgin who looks as if a holy pregnancy is the last thing she wants.

You can quibble with the painting. The perspective on the bed isn't quite right, and something's wrong with Mary's arm and shoulders. (Rossetti never really grasped anatomy.) But it's probably the most honest of Annunciations. Mary accepted God's will, but that doesn't mean she was placid about it. Gabriel tells her not to be afraid, which implies that she was, in fact, afraid. And who wouldn't be? A divine spirit just appeared out of nowhere with earth-shaking news. I would recoil, too.

This is only the slightest scratching of the surface of Annunciation art. There are hundreds of them, including remarkable works from China, India and South America. I even found some amazing modern treatments of the Annunciation, but I knew this post was super-long already and I don't have time to read up on the artists. Google it yourself–you'll be impressed.

I leave you with this. Try not to think about it the next time someone reads Luke out loud:

WHEEEEEEEE!!!!!!!

December 14, 2011

Christmas Art Part 1: The (bizarro) Tree of Jesse

As we loom ever nearer to Christmas (good heavens, I need to do more shopping!), I thought it would be fun to look at some of the art of great moments in the Christmas story. I could have started with something obvious, but I thought, hey, why not begin where the Bible does? With genealogy!

Because when you flip open Matthew hoping to get to some dreams and angels and Wise Men, what do you get first? Begats. A whole bunch of them. At least Luke waits until after the baby is born to bore us with ancestors.

The point was that Jesus was descended from King David and David's father Jesse, and thence back all the way to Abraham. He is of royal lineage and the legitimate heir of the kingdom of Israel's greatest king. This is a little confusing, since after all Jesus is supposed to be God's son, not Joseph's, but the Biblical writers do a little arm waving and note that Joseph was Jesus' "earthly father." (Mary was also believed to be descended from Jesse, and sometimes the tree is shown leading to Mary and then Christ.) You can tie these two New Testament references back to the Old Testament, to Isaiah, who in verse 11;1 wrote, "There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of his roots." Jesus, therefore, is the "shoot of Jesse."

Modern churches spend little time with this passage, but in the Medieval period this was a big honking deal. Genealogies mattered immensely to Medieval people, particularly powerful aristocratic ones, since inheritance and therefore wealth and power were all derived from family. If you've ever tried to figure out the War of the Roses, you'll grasp the point immediately–who was descended from whom took on vast importance. And so the people of the era found the family tree of Jesus relevant and fascinating.

What is so marvelous about these images is the Medieval literalness with which they are interpreted. The Bible says a shoot shall come forth from Jesse, so by golly a shoot comes forth from Jesse:

Detail of Jesse Window, Chartres Cathedral, c.1150

In other words, dude, there is a tree growing out of your crotch!

Jesus' descendants sprang from Jesse's loins, so that's exactly where the tree, er, arises.

Illustrator of 'Speculum humanae salvationis', Cologne, c. 1450

So many jokes. So completely inappropriate. Particularly here, where the flower blooming from Jesse's wood (heh) is the red rose of Mary on which rests of the dove of peace/Christ/the Holy Spirit. This simple depiction is unusual; most are much more complicated:

Master of James IV of Scotland Flemish, Bruges and Ghent or Mechelen, 1510 - 1520

The number of ancestors varied and seems to have depended on the space available and the artist's creativity. The manuscript above only shows a handful. Others go all out:

Herrad of Hohenburg, Hortus Deliciarum, c. 1195

At least here Jesse is sitting next to his tree, rather than having it grow directly out of him.

Oh well, here's another snicker-worthy Jesse fully, er, sprouted.

Hrabanus Maurus, De laudibus sancte crucis, c. 1170-1180

It's unclear why Jesse usually seems passed out. Perhaps this is a visual reference to Adam, who slept while God removed the rib from which he would shape Eve. The allusion to Adam and Eve would make sense, because they are associated with another tree–the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil from which Eve at the apple. Trees had huge significance in Medieval art and theology, and connections were often made between Adam and Eve and their tree and Jesus' crucifixion on the Cross–i.e., another tree. The family tree of Jesse served as a bridge between the two and a pleasing third.

Jesse Tree, Lambeth Bible, c. 1150-1170

We'll end on this magnificent image from the Lambeth Bible with its sinuous Celtic figures. Mary becomes the focus here (dressed in blue, the color of virginity), with tendrils emerging from her head to hold Christ. The seven doves surrounding his head symbolize the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit. Four prophets are seen in the circles on the four corners of the page; you can tell they're prophets because they hold little scrolls (known as banderoles) and are shaking their fingers ("You kids get off my lawn!"). Notice how the figures in the different circles interact. (For a full explanation, see this discussion.)

So think of poor Jesse this season, and the remarkably literal Medieval mind.

December 6, 2011

Brrrrrrrr — the Art of Winter

Winter has come to Texas. Now, all you Northerners may scoff and pooh-pooh the idea, but it's 30 degrees and rainy, and that isn't pleasant anywhere. Yes, I know it gets much worse elsewhere, and yes, by the end of the week it will be 50 and sunny. Great swathes of Texas winters can be lovely, like those December days when it's 60 and bright and everyone walks around saying "Now THIS is why we live in this god-forsaken climate." But it can also be grim and miserable and dreary, and you've got to remember our homes aren't built for this.

At least we don't get this:

[image error]

"February," Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1413-1416

Check out the cat by the fire, and the women warming their legs.

And it's rarely this cold here:

[image error]

"The Hunters in the Snow," Pieter Brueghel, 1565

The hunters look so discouraged, and the dogs positively bummed.

This makes my hands cold just looking at it:

[image error]

Claude Monet, "Winter on the Seine, Lavacourt," 1879-1880

And while Van Gogh is primarily a painter of the summer, he didn't hang up his brushes in the winter:

[image error]

Vincent Van Gogh, "Landscape with Snow," 1888

It's rarely this bad in my neck of the woods:

[image error]

Everett Shinn, "Snow Storm, Madison Square N.Y.," 1898

I hope that poor woman is wearing long underwear, because the wind is blowing right up her skirt.

And while this is lovely, I'd rather look at it through a window with a cup of hot chocolate than be out in it:

[image error]

Ansel Adams, "Oak Tree, Snow Storm, Yosemite," 1948

Stay warm, friends.