They do it with mirrors

Edouard Manet was born last Monday, and thinking about Manet got me thinking about his last masterpiece, which got me thinking about mirrors.

A mirror provides the background to A Bar at the Folies-Bergere and adds great mystery to this captivating painting. But Manet wasn't the first artist to have fun with mirrors in his art.

It all started–as did so many things–with Jan van Eyck, the great Flemish painter of the Renaissance. Van Eyck is credited with introducing or at least popularizing the use of oil paints in Northern Europe and mastering linear perspective. His paintings are masterworks of fine detail and painstaking composition.

He also, I think, had a sense of humor. Take this, one of his most well-known works:

Jan van Eyck, "The Arnolfini Portrait," 1434

I love the details. Notice the metal of the chandelier, the droop of the woman's gown, the fluff of the little dog's fur. The work depicts the Italian merchant Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his wife and is presumed to be a wedding portrait. The woman is not, as one might think, pregnant; having that much fabric in her gown was the fashion as well as a sign of wealth, since only the rich could afford such long dresses that they had to be hiked up to walk.

The sly touch of the painting is the back wall. Look directly between the couple and you see first writing and then a mirror. The writing is it's own quirk; it is van Eyck's signature, one of the first in Western art. It reads "Jan van Eyck was here 1434." The mirror, however, is the most fascinating element since it reflects, well, us. It is positioned to reflect the viewer's position exactly. What does it depict?

Jan van Eyck, Detail from "The Arnolfini Portrait," 1434

Behind the couple and the open window, both distorted by the convex shape of the mirror, very faintly you can see two figures standing in the doorway, right where we, the audience, would be standing. It's hard to tell from a web-quality image, but one of the figures is raising his hand as if to say hello. Art historians conjecture that one of the figures is the artist van Eyck himself, inserting himself unobtrusively into his own work. (Isn't the detail on the mirror frame magnificent? The circles around the frame show scenes from the life of Christ, barely visible and probably ignored by most viewers.)

Another artist to have fun with mirrors was Diego Velazquez in his masterpiece of 1656, Las Meninas. He knew The Arnolfini Portrait and was likely inspired by it:

Diego Velazquez, "Las Meninas," 1656

So much going on here. Basically, the work shows one of the crown princesses of Spain, the Infanta Margarita, surrounded by her maids, chaperone, bodyguards, dwarves, and dogs. On the left, we see the back of a picture frame and the artist himself, Velazquez, holding a brush and standing back to get a view of his work.

In the very back against the wall we see a mirror. Based on where the mirror is positioned, just as in The Arnolfini Portrait, the viewer–us–would naturally be what is reflected. Except take a closer look:

Diego Velazquez, "Las Meninas," 1656

The two shadowy yet glowing figures–notice how their pale faces stand out against the dark wall–are the king and queen of Spain, Philip IV and Mariana of Austria. (Check out this painting by Velazquez of the king should you have any doubts.)

How to interpret this? Many art historians believe the work depicts a moment in a time, a sort of snapshot, of the court. The artist, a favorite of the king, is at work on a portrait of the royal couple. The charming princess comes for a visit with her courtiers. The mirror reflects the king and queen smiling at their daughter as they pose.

Except, except . . . putting any ordinary viewer into the exact position of the king would have been a shocking breach of protocol, like letting a peasant borrow a crown. Velazquez not only survived by thrived at the Spanish court for decades and would have known better.

So what is going on? Maybe, some suggest, the mirror reflects not the actual king and queen but the painting of the king and queen. There's something to this. The mirror is actually offset slightly to the left, not in the direct middle of the painting, as is the frame. Or maybe, others propose, the painting was intended for the private view of the king, or at least the privileged view of the king. It was his work of his family, and any other audience taking his position was unimportant.

Maybe the meaning is more metaphorical than literal. Maybe the mirror reflects not the real image of the king and queen, but the idealized reflection of the ideal king and queen, thereby paying a subtle compliment to Philip. Maybe Velazquez is playing with the idea of the painting as a mirror on nature. If a painting is supposed to reflect reality exactly, then what does a reflection of a reflection do? (Or even a reflection of a reflection of a reflection, if the mirror is supposed to depict the unseen image on the artist's canvas instead of–or in addition to–reality.) Many critics make much of the fact that the artist, Velazquez, is looking directly at us and/or the king and queen; is the entire work conjured up by his brush, with the artist the master of illusion greater than reality? You can go around and around, and pretty soon art historians are making statements about how "the painter achieves a reciprocity of gazes that makes the interior oscillate with the exterior." Personally, I don't think there's any one explanation; I think Velazquez was brilliant, and brilliant artists sometimes confound their audiences on purpose.

Which brings us to the most confounding mirror image of all, Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergere, which was inspired by both van Eyck and Velazquez:

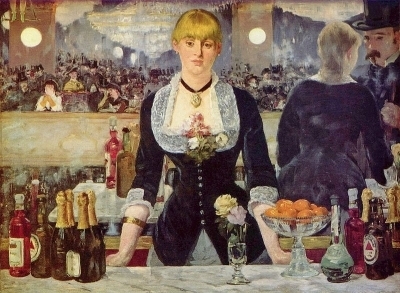

Edouard Manet, "A Bar at the Folies-Bergere," 1882

It's so deceptively simple at first glance. We see a well-dressed girl behind the bar at the fashionable nightclub. She rests her hands on the marble bar-top, while behind her a mirror reflects the busy club. Look in the upper left corner to catch a glimpse of the famous trapeze on which acrobats performed above the patrons' heads; enormous chandeliers flood the room with light. We can tell that the background is a mirror because we can see its gold frame just above the bar and about the level of the woman's hips.

Except–that can't be right. If this were a mirror, the woman's black gown would be reflect directly behind her. Instead, we see her rear reflection off to the right. Moreover, this reflected woman is leaning forward slightly and talking to the top-hatted man. Where did he come from?

Perhaps what we're seeing are two separate moments in time, one now (the woman alone, her face abstracted, closed, darkly pensive) and one earlier (talking to the man.) It was known that girls at the Folies Bergere were often prostitutes, or at least presumed to be so; some critics believe the man is propositioning the woman. She is as available as the wines and beers on her counter. Her later expression reflects her ambivalence about the encounter.

I have some quibbles with this interpretation; the man looks pretty darn neutral for someone soliciting sex. If Manet had intended him to be leering, surely he would have given us some clues.

He gave us other clues:

Edouard Manet, "A Bar at the Folies-Bergere," 1882

Manet was an excellent student of art history; he knew his symbolism. Roses and oranges have had meaning for centuries. Oranges were symbols of purity, chastity and generosity, while roses were symbols of love and purity. Both were traditionally associated with the Virgin Mary. So here in this crowded, glittering bar, which seems so dated to us but would, to Manet's audience, been completely modern and of the moment, we have a young woman, flowers at her breast, oranges and roses before her, a modern Mary–contemplative, isolated, beautiful.

To me, the image and the reflection don't have to take place at different times; they could just as well reflect different mental states. Anyone who has ever worked retail–anyone, in fact, who has found him- or herself in the middle of a crowd–has had the feeling of inner withdrawal, of internal retreat. Suddenly you are separate from the scene, observing it and yourself within it, while you continue to interact. I think Manet is painting an internal moment of abstraction, perhaps revealed by a split-second expression between customers. And his subject is a contemporary Madonna, singled out by the artist's vision but otherwise just a girl at a bar. Did he go the Folies Bergere and see her pausing for a moment, a fleeting look crossing her face that arrested his attention? Did he alone recognize her uniqueness and her beauty?

Three mirrors, three mysteries. What do you think? When you look at these reflections, what do you see?