Yeah, you like Shakespeare–but will you die for him?

On this date in 1849, a riot rocked New York City, leaving 120 injured and at least 25 dead. The cause of the disturbance?

Different interpretations of Macbeth.

Really.

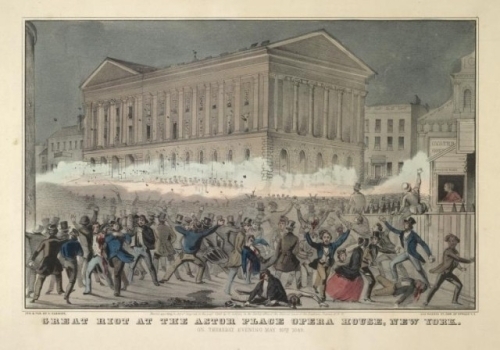

This is the anniversary of the Astor Place Riots, possibly the strangest theater-related civic disturbance in history. Macbeth usually doesn’t generate this much controversy. Usually people don’t kill each other over Shakespeare.

Of course, the riot was about more than Shakespeare. The riots were the result of a complicated situation involving class, race, religion and immigration, but nevertheless Shakespeare was the in there all along, and the consequences for American culture were lasting.

So here’s what happened.

On May 7, signs went up all over New York announcing rival performances on the same night of Macbeth. At the Astor Place Opera House, William Charles Macready would be playing the Scottish king. At the Broadway theater, the part would be played by Edwin Forrest.

Now, Forrest and Macready were two very different types of actors who appealed to two very different kinds of audiences.

William Charles Macready as Macbeth

Macready was an Englishman of relatively upper-class origins who had earned a reputation as the greatest British actor of his generation. Macready spent most of his career in England, but he toured the United States several times to great acclaim.

Macready’s greatest fans were established residents of the East Coast, generally of English or Dutch origin. Think Mayflower descendents, old money.

Macready was set to perform at the Astor Place Opera House, which had been established as the theater of the New York upper class. The theater was far more comfortable–and therefore expensive–than competing theaters, and the goal from day one was to attract an upper-class audience. It was described as “a refined attraction which the ill-mannered would not be likely to frequent, and around which the higher classes might gather.” Astor Place enforced a dress code of evening dress and kid gloves and featured only the finest performers from Europe.

Edwin Forrest, daguerreotype by Mathew Brady

Forrest was a very different type from Macready, and he performed in very different venues. Forrest was a native of Philadelphia and was raised in humble circumstances. He made his reputation on tours through the rough West and South and had enormous success in blackface (!!!).

He was particularly associated with the Bowery Theater in New York, which catered to a lower-class population of Irish and German immigrants. These rough-and-tumble New Yorkers became his greatest fans. They didn’t show up in evening dress and kid gloves to the theater; they sat on rough benches and enjoyed melodramas, animal acts and minstrel shows.

They also LOVED Shakespeare.

This is hard for us to get our heads around. Today Shakespeare is the highest of high art. Seeing a Shakespeare play is one step removed from opera. Famous actors turn to Shakespeare to prove they’ve got the chops. Shakespeare is considered great, but hard and inaccessible.

That attitude couldn’t have been farther from that of mid-19th century America. Everyone knew Shakespeare, and everyone loved his work. Memorizing Shakespeare was a major portion of every child’s education; even grammar school kids were expected to recite Shakespeare and the Bible. Shakespeare’s play were the second-most likely book owned by an American family, behind the Bible. In hardscrabble camps in California, impoverished miners whiled away winter months reciting Shakespeare from memory and putting on plays.

Shakespeare was the ultimate popular culture.

(And it makes sense, really–Shakespeare wrote for a general audience. The audience at the Globe Theater was crammed with peasants as well as aristocrats.)

Forrest represented this populist tradition of Shakespeare productions. Macready, on the other hand, represented something new: high-class Shakespeare, targeted at an upper-class audience.

The two actors appeared in New York at a tense time. Emotions were running high between recent immigrants, mostly Irish, and upper-class Americans. The largely Protestant upper-class despised the Catholic Irish and disdained them as lazy, dirty job-stealers. Irish were pouring into the country, fleeing the Potato Famine. For their part, the immigrants hated the British, their traditional oppressors, who weren’t lifting so much as a finger to save the starving Irish. Anyone who appeared even remotely Anglophile immediately attracted their anger.

It didn’t help that Forrest and Macready had a long-standing personal feud, largely fueled by Forrest. On a previous tour, Forrest followed Macready from city to city appearing in the same plays to challenge him. Newspapers took up the fight and argued patriotically for the superiority of the native Forrest. Macready, for his part, publicly stated that Forrest lacked “taste.” This caused such uproar that at one point someone flung half the carcass of a dead sheep at Macready on stage.

On the night of May 7, Forrest supporters packed the top levels of Astor Place and halted the production by throwing rotten eggs and potatoes at the stage, hissing and shouting and tearing up seats. Macready and the rest of the cast valiantly tried to carry on, although forced to perform in pantomime since they couldn’t be heard. Macready announced the next day that he would leave for Britain immediately, but a petition by wealthy Astor Place fans persuaded him to stay, and he prepared to take the stage on May 10.

Both sides prepared for the conflict, with the mayor calling out the militia and Forrest backers handing out free tickets and posting handbills that read “SHALL AMERICANS OR ENGLISH RULE THIS CITY?” By the time the curtain rose, 10,000 people surrounded the theater. The mob began lobbing stones and setting fires. The audience inside cowered in their seats and the actors attempted to carry on over the sound of shouting from outside. Macready managed to escape from the back in disguise.

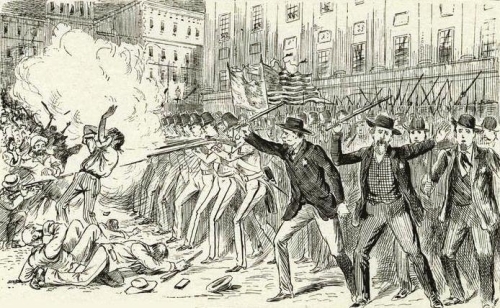

Authorities called in the troops, who fired first in the air, then point-blank into the crowd.

When it was all over, some 25 people lay dead, most of them Irish immigrants. Soldiers and police were among the seriously wounded. It took two days to get the city back under control.

The riot had long term results. It marked the high point for Shakespeare in popular culture. Forrest’s reputation was badly damaged; he was seen as instigating the bloodshed and was condemned across the country. His declining fame tarred the entire field of popular theater with which he was represented.

Over time, Shakespeare fell out of favor in popular entertainment. The causes for this shift are complicated; the reverence with which the Bard was held actually contributed to the decline of popular productions, as Shakespeare became seen as too important, too good to be trusted to amateurs.

I love this story, despite the violence, because of all it tells us about a past we’ve forgotten. How many Americans know that the Irish were once a despised immigrant community, hated without cause and deeply discriminated against? How many of us remember a time when being Catholic was considered alien and distrustful? How many know 25 people died–in part at least–because of Shakespeare?

So remember the Astor Place Riots, and remember this as well: if you think America is weird and mixed-up today, study American history. We’ve been weird and mixed-up from day one.