Arcimboldo and the Art of the Weird

The study of art history is sometimes reduced to the study of links. Artist A transitions to Artist B which leads, apparently inevitably, to Artist C. A great deal of effort goes into getting all the movements in the right order and tracing the connections between them.

The approach works, but it has its limitations. Namely, what do you do with the artists who don’t lead anywhere? What if an artist is a stylistic dead end, wandering off in his or her own direction while the main highway of art history moves forward at a right angle?

Art history doesn’t know what to do with these anomalies, so it mostly ignores them on the grounds that they aren’t “significant.” As if all that mattered was how much influence you had on the future.

That’s a shame, because some really weird and fascinating art isn’t “significant,” but wow, is it interesting.

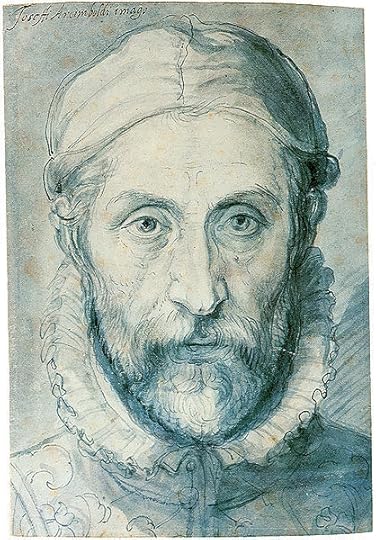

Take, for example, this esteemed gentleman. He looks mild-mannered enough. His name was Giuseppe Arcimboldo, and he had possibly the weirdest imagination this side of Salvador Dali.

Take, for example, this esteemed gentleman. He looks mild-mannered enough. His name was Giuseppe Arcimboldo, and he had possibly the weirdest imagination this side of Salvador Dali.

You wouldn’t have expected it. Archimboldo was born in 1526 in Milan, and his father was an artist. He followed a predictable Renaissance path, apprenticing, training, design cathedral windows and painting portraits. He landed a job with Maximilian II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in Vienna in the early 1560s.

He completed standard portraits and religious scenes, but his taste tended toward the capricciosa–“whimsical.”

And so it was on New Year’s Day 1569 that Archimboldo presented to Maximilian a series of paintings on the theme The Four Seasons.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Spring," 1569

It’s a guy’s head, made of flowers.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Summer," 1569

Or fruit.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Winter," 1569

Or a battered tree.

That is some seriously weird art. There’s nothing else like it in Italian art. There’s nothing like it anywhere.

And they were an immediate hit. The Hapsburg court loved them. At a 1571, Maximilian and other members of the court actually dressed up as the paintings in a festival designed by Arcimboldo. The emperor himself played Winter.

Historians note that works were more than just amusing. They also held potent symbolism about the power of the ruling family over everything, even nature. Under the Hapsburgs, the paintings hint, nature itself overflows with bounty.

Similarly, in a series on the Four Elements, the royal family exerts its influence over the fundamental forces of nature.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Water," ca. 1566

Look at those details–how the oyster shell becomes an ear. If I look at this one too long, it gives me the heebie-jeebies, imagining all those fish and turtles and squid moving around. Gah.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Fire," ca. 1566

The symbolism of “Fire” is particularly pronounced. The nose and ear are fire strikers, one of the symbols of the Habsburg family. The muskets and cannons of the body are bold representations of power. On the chest is the double-eagle seal of the Holy Roman Empire.

So Arcimboldo was a sophisticated court painter, currying to the whims and egos of his patrons. I see him in the same vein as the English playwrights such as Ben Jonson who wrote silly yet sophisticated masques that both stimulated smart courtiers and stroked their egos. Wealthy courts in time of peace have always tended toward the lavishly ridiculous. Think of the clothing of the court of Marie Antoinette.

The Hapsburg court ate it up. Maximilian’s successor, Rudolf II, even had Archimboldo paint his portrait in his unique style:

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Rudolf II as Vertumnus" (Roman god of the seasons), ca. 1590-91

There’s a lot of sly humor here–notice that the ears are actually ears of corn. The flowers and fruits are all recognizable varieties, and the interesting thing about the corn is that it was newly imported from the Americas.

Once he mastered his unique gimmick, he kept at it, his works becoming more and more detailed and clever. He did another series on the seasons:

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Autumn," 1573

Notice that the Adam’s apple is actually an apple.

He played around:

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "The Greengrocer," ca. 1590

Like this work, which has more than one way of looking at it:

He did several works of types of individuals or professions, created out of their working materials:

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "The Librarian," ca. 1570

(I wish I knew if Picasso was familiar with this work. It’s very Cubist, don’t you think?)

Arcimboldo eventually retired from court service and returned to his hometown Milan. He died there in 1593. And his works were quickly forgotten. After all, it’s not like an entire school of art grew up around the gimmick of make faces out of other objects.

And forgotten he remained until the 1930s and his rediscovery by the Surrealists. The French Surrealist magazine Minotaure reproduced his work and Alfred Barr featured him in an Museum of Modern Art exhibition titled “Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism.” Man Ray, Rene Magritte and Dali all claimed Arcimboldo as inspiration, and Dali declared him the Father of Surrealism, 300 years earlier.

Arcimboldo has a secure spot in museums, where his works hang uneasily next to super-serious Mannerist portraits and religious scenes. That we know about him at all is due to the Surrealists, who established a link with the artist and turned his dead end into a by-way.

Link or not, Arcimboldo’s work is worth a look–if for no other reason that it’s seriously weird. He’s funny, yes, but also unsettling. I think it has to do with the sense of “the uncanny”–that feeling that something is familiar and yet completely strange. I get the joke when I look at his work, but I don’t want to linger on it. Spenting too much time looking at his paintings gives me the screaming heebie-jeebies.

What do you think about Arcimboldo? Worth a serious look? Or too frivolous to bother? And what about the creepy factor? Does he weird you out, or is that just me?