Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 27

September 1, 2021

The Month That Changed The World: July 16-August 15, 1945

[Originally posted in 2020 to mark the 75th Anniversary of the end of World War II and the transformation of the modern world; Revised August 15, 2021]

From the “Trinity” Test to Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Japan’s Surrender:

The Month That Changed the World

Formal surrender aboard USS Missouri Sept. 2. 1945 https://www.history.navy.mil/our-coll...

The following timeline summarizes the extraordinary series of events that helped make the modern world between July 16 and August 15, 1945.

The Atomic Bomb Dome-Hiroshima (Photo Courtesy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered)

On August 6, 1945, the New York Times asked:

“What is this terrible new weapon?”

(New York Times, August 6, 1945: “First Atomic Bomb Dropped on Japan”)

The story followed the announcement made that day by President Harry S. Truman:

“SIXTEEN HOURS AGO an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of T.N.T. It had more than two thousand times the blast power of the British ‘Grand Slam’ which is the largest bomb ever yet used in the history of warfare.”

August 6, 1945

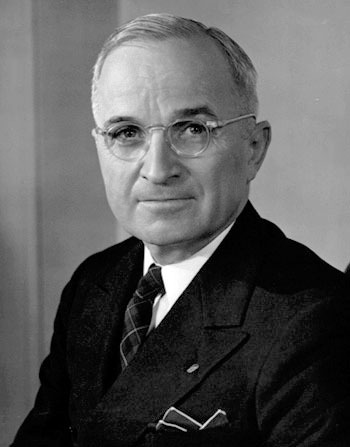

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

(“Statement by the President Announcing the Use of the A-Bomb at Hiroshima”: Truman Library and Museum)

The use of the first atomic bomb followed the successful test detonation –the goal of the wartime Manhattan Project — and the beginning of a series of world-changing events.

• July 16, 1945 the first atomic device, nicknamed “the Gadget,” is detonated in the “Trinity” test at Alamogordo, New Mexico. Read this account of the test in National Geographic.

New York Times reporter Dennis Overbye visited the site in 2021. His report “Touring Trinity, the Birthplace of Nuclear Dread”:

“The detonation created a crater eight feet deep, a half-mile wide and lined with glassy pebbles called trinitite: sand that had been swept up in the fireball, vaporized and then fell back down in molten radioactive droplets.”

The Trinity test, 15 seconds after detonation. Photo courtesy of David Wargowski Source: National Museum of Nuclear Science & History

In the course of the next weeks, the world would be transformed, with the arrival of the Atomic Age, Japan’s surrender, the end of World War II, the charter of the United Nations, and the beginning of the Cold War.

The development, testing, and use of atomic bombs is documented by the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History.

• July 17 In Potsdam, near Berlin in defeated Germany, President Harry S. Truman comes face to face with the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. Truman had taken office upon the death of President Roosevelt on April 12, 1945 without knowledge of the Manhattan Project or the atomic bomb’s existence. Having been told about the potential weapon, Truman is informed of the successful “Trinity” test while meeting Stalin with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the European postwar conference.

Harry S. Truman and Joseph Stalin at Potsdam (Public Domain: President Harry S. Truman Library and Museum)

“I told Stalin that I am no diplomat but usually said yes or no to questions after hearing all the argument.”

Read about Stalin’s rise to power in Strongman

Following the New Mexico test success, the components of the atomic bomb are loaded onto the USS Indianapolis in San Francisco for transport to an airbase on Tinian Island in the Pacific. Many of the crew of nearly 1,200 men have no idea what the ship is carrying.

•July 19 In the United States, Congress approves the Bretton Woods agreement, an international pact designed to avoid postwar financial crises like those that followed World War I. The agreement creates the International Money Fund and what later becomes the World Bank.

The Japanese cities of Choshi, Hitachi, Fukui and Okazaki are struck by 600 B-29 Superfortress bombers dropping some 4,000 tons of bombs — the largest employment of the bomber to date.

The USS Indianapolis reaches Pearl Harbor in the first leg of its voyage to deliver the atomic bomb components.

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/515009

• July 21 “A senior US Army Air Force intelligence officer in the Pacific distributed a report declaring: ‘The entire population of Japan is a proper Military Target . . . THERE ARE NO CIVILIANS IN JAPAN.’” Richard B. Frank via World War II Museum.

In Potsdam, Truman and Churchill privately agree to use the atomic bomb if Japan does not surrender. Read about Truman’s decision from the National Park Service Harry S. Truman National Historic Site.

• July 22 In what is described as the last surface battle of World War II, the U.S. Navy sinks Japanese supply ships in the “Battle of Sagami Bay” (“Tokyo Bay”). Naval bombardments of the Japanese mainland continue, along with B-29 bombing raids striking Japanese cities.

In China, the American Far East Air Force attacks Japanese troops, airfields, and shipping near Shanghai.

• July 23 In Potsdam, Secretary of War Henry Stimson receives atomic bomb target list. In order of choice they are: Hiroshima, Kokura, and Niigata. He also receives an estimate of atomic bomb availability: “Little Boy” should be ready for use on Aug. 6, second “Fat Man-type” by Aug. 24. There are plans for a total of seven bombs available by December.

• July 24 Truman informs Stalin of a “new weapon of unusual destructive force.”

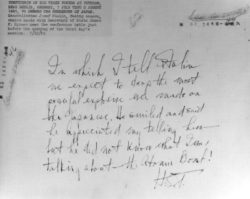

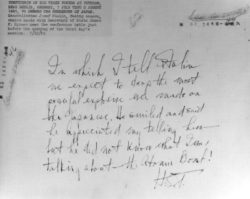

“In which I tell Stalin we expect to drop the most powerful explosive ever made on the Japanese. He smiled and said he appreciated my telling him–but he did not know what I was talking about–the Atomic Bomb! HST”

Truman’s note on back of photograph from Potsdam Conference describing his conversation with Stalin about the atomic bomb. Source: Truman Museum https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/photogr...

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

But Stalin already knows about the atomic bomb because of a network of spies inside the Manhattan Project. The Soviet push to capture Berlin in April and May 1945 was motivated in part by Stalin wanting to capture German scientists working on a Nazi atomic bomb and tons of uranium held in a Berlin lab. This episode is recounted in the “Berlin Stories” chapter of my book The Hidden History of America at War.

• July 25 Truman writes in his diary that he has made the decision to use “the most destructive bomb in the history of the world… I have told the Sec. of War, Mr. Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children.”

Sources: Truman Library and Museum National Security Archive, George Washington University

• July 26 British general election returns are announced; Prime Minister Winston Churchill is defeated and replaced by Clement Attlee.

“The landslide victory comes as a major shock to the Conservatives following Mr Churchill’s hugely successful term as Britain’s war-time coalition leader, during which he mobilised and inspired courage in an entire nation.”

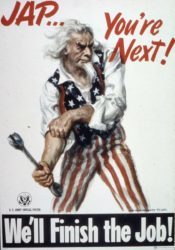

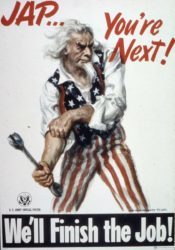

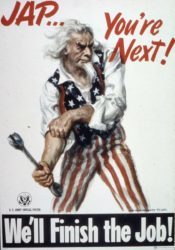

U.S. Propaganda poster (Source National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/513563)

–BBC

At the Potsdam Conference, the Potsdam Declaration demands an “Unconditional surrender” by Japan. Issued by Great Britain, China, and the U.S., it threatens:

“The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

The USS Indianapolis reaches Tinian that day.

USS Indianapolis 10 July 1945, after final overhaul and repair of combat damage. Photograph from the Bureau of Ships Collection in the U.S. National Archives (Naval History and Heritage Command https://usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.m...)

“Indianapolis departed San Francisco on 16 July 1945, foregoing her post-repair shakedown period. Touching at Pearl Harbor on 19 July, she raced on unescorted and reached Tinian on 26 July, covering some 5,000 miles from San Francisco in only ten days.”

After delivering the atomic bomb components, the ship departs for Guam and the Philippines.

• July 27 American B-29 SuperFortress bombers drop 600,000 leaflets over eleven Japanese cities warning that they are targets of bombings.

“But, unfortunately, bombs have no eyes. So, in accordance with America’s humanitarian policies, the American Air Force, which does not wish to injure innocent people, now gives you warning to evacuate the cities named and save your lives.” –from a “LeMay Leaflet,” named for General Curtis LeMay, architect of the Pacific bombing campaign (Atomic Heritage Foundation)

In England, Winston Churchill has a final meeting with his joint chiefs of staff.

• July 28 In New York City, an Army B-25 bomber on a routine mission flies into the Empire State Building –then the world’s tallest skyscraper. Three crew members and eleven people in the building are killed.

“B-25 Mitchell bomber smashed beyond recognition into Empire State Building. This is a picture of the wreckage-strewn 79th floor where the bomber tore a 18-foot hole in wall. Propeller is embedded in the wall at the left.” Source: New York Daily News

“I was at the file cabinet and all of a sudden the building felt like it was just going to topple over,” [office worker Gloria] Pall said. “It threw me across the room, and I landed against the wall. People were screaming and looking at each other. We didn’t know what to do. We didn’t know if it was a bomb or what happened. It was terrifying.” Source: National Public Radio

In Potsdam, newly-elected Prime Minister Clement Attlee of the Labour Party arrives to rejoin the talks which are nearly concluded. Attlee led post-war UK until 1951.

“As Prime Minister, he enlarged and improved social services and the public sector in post-war Britain, creating the National Health Service and nationalising major industries and public utilities. Attlee’s government also presided over the decolonisation of India, Pakistan, Burma, Ceylon and Jordan, and saw the creation of the state of Israel upon Britain’s withdrawal from Palestine.” Official UK Biography of Attlee.

• July 29 The Japanese government rejects the Potsdam Declaration surrender demand.

Just after midnight, the Indianapolis is struck by a Japanese torpedo.

• July 30 Torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, the Indianapolis sinks in twelve minutes. Between 800 and 900 of the crew of nearly 1,200 are plunged into the shark-infested waters.

“What followed was an ordeal of hell on earth for those who survived the sinking. For a whole host of reasons, many related to the secrecy of her atom bomb mission, the rest of the Navy did not know that Indianapolis was missing.”

— Sam Cox (Rear Adm., USN, Ret.), “Lest We Forget: USS Indianapolis and her sailors”

–Read “The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis” via the National Archives including a film clip from the classic scene in Jaws in which Captain Quint describes the sinking of the ship and the shark attacks that followed.

• July 31 The assembly of the atomic bomb, code named “Little Boy,” is completed. The final arming of the bomb will be done in-flight.

In Potsdam, Truman is notified of the bomb being ready. He writes a message that concludes:

“Release when ready, but not sooner than August 2. HST”

According to the Truman Library:

The actual reply that President Truman wrote on July 31, 1945 (Photo taken by Dawn Wilson at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library)

“No known written record exists in which Harry Truman explicitly ordered the use of atomic weapons against Japan. The closest thing to such a document is this handwritten order, addressed to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, in which Truman authorized the release of a public statement about the use of the bomb. It was written on July 31, 1945 while Truman was attending the Potsdam Conference in Germany. In effect, this served as final authorization for the employment of the atomic bomb, though the expression ‘release when ready’ refers to the public statement.”

• August 1 The atomic bomb is ready and flight orders are prepared. But weather delays the mission. Of four potential target cities, Hiroshima is chosen as the primary target.

In Potsdam that day, the Big Three wrap up their meetings and discuss plans for the trials of war criminals that later become known as the Nuremberg Trials.

Read my 2021 post on the Nuremberg Trials.

In the Pacific, hundreds of survivors from the Indianapolis desperately try to stay afloat in the shark-infested waters.

“In that clear water you could see the sharks circling. Then every now and then, like lightning, one would come straight up and take a sailor and take him straight down.” – Survivor of the Indianapolis sinking to the BBC.

• August 2

The Big Three at the end of the Potsdam Conference: Front row (Left to Right) Prime Minister Attlee, President Truman, Generalissimo Stalin. Source: Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives.

Shortly after midnight, the Potsdam Conference concludes with a joint communique. It includes reference to the United Nations, whose organization and charter had been completed on June 26 at a conference in San Francisco.

Truman speaks of a future Washington meeting with the Soviet leader, but he and Stalin never meet again.

What was clear was that the Conference had solidified the Soviet Union’s domination over much of Eastern Europe, including the eastern half of a divided Germany. Admiral William D. Leahy, Truman’s Chief of Staff, later wrote:

“The Soviet Union emerged at this time as the unquestioned all-powerful influence in Europe….”

The U.S. Navy is still unaware that the Indianapolis has gone down. More than 800 men went into the water and the survivors are spotted by a reconnaissance plane four days after the sinking.

“Marks’s crew dropped rubber rafts and supplies as they witnessed continuing shark attacks. Disregarding orders not to land at sea, the pilot touched down and began taxiing to pick up survivors.

As darkness set in, and as Marks waited for rescue vessels, he pulled men from the water into his aircraft. When the plane’s fuselage was at maximum capacity, survivors were tied to the wings with parachute cord. The pilot and his crew rescued a total of 56 men. Once signaled, a total of seven Navy ships converged on the site and rescued the remaining men. Only 317 sailors survived.” –National Archives, “The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis”

Indianapolis’ survivors en route to a hospital following their rescue, early August 1945. Source: Naval History and Heritage Command

• August 4 Colonel Paul Tibbets briefs the men of the 509th Composite Group -the weapon delivery arm of the Manhattan Project. Tibbets is the commander of the unit. His men do not know the nature of the bomb they will carry.

• August 5 The bombing mission is confirmed and Colonel Paul Tibbets announces he will pilot the plane which he names “Enola Gay,” after his mother.

Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr., Pilot of the Enola Gay, the Plane that Dropped the Atomic Bomb August 6, 1945 (National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/535737)

• August 6 At 0245 local time on Tinian,

“Enola Gay begins takeoff roll. [Pilot] Colonel Paul Tibbets says to co-pilot Robet Lewis, ‘Let’s go.’ He pushes all of the throttles forward. The overloaded Enola Gay lifts slowly into the night sky, using all of the more than two miles of runway.”

—Atomic Heritage Foundation, minute-by-minute timeline of Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings.

0730:

“Tibbets announces to the crew: ‘We are carrying the world’s first atomic bomb.’ He pressurizes the Enola Gay and begins an ascent to 32,700 feet. The crew puts on their parachutes and flak suits.”

0912: Control of the Enola Gay is handed over to the bombardier, Thomas Ferebee, as the bomb run begins. A Radio Hiroshima operator reports that three planes have been spotted.

0914 (0814 Hiroshima time): Tibbets tells his crew, “On glasses.”

–Atomic Heritage Foundation Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombing Timeline

8:15 AM (Hiroshima local time) The first atomic bomb is detonated over Hiroshima.

“In less than one second, the fireball had expanded to 900 feet. The blast wave shattered windows for a distance of ten miles and was felt as far away as 37 miles. Over two-thirds of Hiroshima’s buildings were demolished. The hundreds of fires, ignited by the thermal pulse, combined to produce a firestorm that had incinerated everything within about 4.4 miles of ground zero.”

Source: Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered.

“In the street, the first thing he saw was a squad of soldiers who had been burrowing into the hillside opposite, making one of the thousands of dugouts in which the Japanese apparently intended to resist invasion, hill by hill, life for life; the soldiers were coming out of the hole, where they should have been safe, and blood was running from their heads, chests, and backs. They were silent and dazed.

Under what seemed to be a local dust cloud, the day grew darker and darker.”

–John Hersey, “Hiroshima,” New Yorker (August 24, 1946)

In Hiroshima, the estimated death toll reaches eighty thousand people killed instantly; as many as 90 percent of the city’s nurses and doctors also die instantly. By 1950, as many as 200,000 die as a result of long-term effects of radiation.

“Historians say General Groves understood the radiation issue as early as 1943 but kept it so compartmentalized that it was poorly known by top American officials, including Harry S. Truman. At the time he authorized the Hiroshima bombing, President Truman, scholars say, knew almost nothing of the bomb’s radiation effects.”

Read: “The Black Reporter Who Exposed a Lie about the Atomic Bomb” New York Times

In his official announcement, President Truman said,

It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.

Read Don’t Know Much About Hiroshima for more details about the bombing and its aftermath.

•August 7 A report to the Japanese Imperial Army General Staff reads:

“The whole city of Hiroshima was destroyed instantly by a single bomb.” (Atomic Heritage Foundation)

On Guam, the decision to use a second device is made and the mission date set for August 10, then moved to August 9 over weather concerns.

Fat Man being lowered and checked on transport dolly for airfield trip Image Source: Heritage Foundation https://www.atomicheritage.org/histor...

•August 8 Fulfilling a pledge Stalin had made earlier at the Yalta conference, the Soviet Union declares war on Japan and invades Manchuria the next day, sending more than one million troops into Japanese-held territory.

The Japanese military leadership was still divided over the surrender demand, with some leading generals vowing to fight to the death. A coup against Emperor Hirohito began to be planned by members of the Japanese military.

A plutonium bomb code named “Fat Man” is prepared on Tinian. It will be carried by a B-29 called “Bockscar.” The primary target is the city of Kokura, home to a large munitions plant.

The crew of the B-29 called “Bockscar” taken after the Nagasaki bombing (Image: U.S. Air Force)

•August 9

0347: Bockscar, piloted by Major Charles Sweeney, lifts off from Tinian Island. The target of choice is Kokura Arsenal.

Clouds and smoke from nearby fires obscure Kokura, so “Fat Man” is dropped over the secondary target, the city of Nagasaki, with a population estimated at 263,000, a city that was home to two Mitsubishi military plants. It is also the site of a prisoner of war camp.

“Nagasaki was a city on the west coast of Kyushu on picturesque Nagasaki Bay. It was famous as the setting for Puccini’s beautiful opera Madame Butterfly. It was also home to two huge Mitsubishi war plants on the Urakami River. This complex was the primary target, but because the city was built in hilly, almost mountainous terrain, it was a much more difficult target than Hiroshima…

Fat Man exploded at 1,840 feet above Nagasaki and approximately 500 feet south of the Mitsubishi Steel and Armament Works with an estimated force of 22,000 tons of TNT.

Unlike Hiroshima, there was no firestorm at Nagasaki. Despite this, the blast was more destructive to the immediate area, due to the topography and the greater power of Fat Man.”

—Hiroshima & Nagasaki Remembered

The death toll in Nagasaki also reaches 80,000 by the end of 1945. Read a full account of this mission in “Nagasaki: The Last Bomb” by Alex Wellerstein (New Yorker, August 7, 2015)

The National Archives “Unwritten Record” blog also offers resources on the atomic bombings.

•August 10 After Nagasaki is bombed, Truman orders no more strikes without his authorization. Another plutonium core for a third weapon is prepared for shipment.

September 24, 1945, 6 weeks after Nagasaki was destroyed by the world’s second atomic bomb attack. Photo by Cpl. Lynn P. Walker, Jr. (USMC) National Archives FILE #: 127-N-136176

Although an unofficial surrender message was sent by a Japanese news agency, the Japanese cabinet was divided and no decision was made. The Emperor would not surrender his sovereignty.

•August 11 The U.S. Secretary of State James Byrnes rejects any conditional surrender and states that the Emperor and Japan’s government will be subject to the Allied Powers and declares that any future Japanese government must reflect the will of the people.

Soviet troops invade South Sakhalin island, Japanese-held territory.

•August 12-13 Soviet troops advance into the Korean peninsula.

Emperor Hirohito agrees to accept the terms of Secretary Byrnes’s note and orders the suspension of military activity. He records a surrender announcement. Military officers began to plot against Hirohito in a coup known as the “Kyujo incident.”

•August 13 The bombing of Japan, including firebombing, resumes with more than 1,000 B-29s taking part.

Japanese officers continue to seek allies in their planned coup against the Imperial government.

Residential section of Tokyo after the March 1945 air raids. (Wikimedia commons http://www.kmine.sakura.ne.jp/kusyu/k...

•August 14 (August 15 in Japan): The military coup fails and several plotters commit suicide.

In an extraordinary address recorded earlier, the Emperor of Japan is heard on the radio for the first time and accepts the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration, agreeing to the unconditional surrender.

Read: “The Emperor’s Speech” by Max Fisher (The Atlantic, August 15, 2012)

At a White House conference, according to United Press International, Truman says:

“This is the day when Fascist and police governments cease to exist in the world. This is the day for democracy.”

-Source: “Japan Surrenders Unconditionally, World At Peace” UPI archives

Truman announces Japan’s surrender to reporters in Oval Office.

Credit: Rowe, Abbie National Park Service Harry S. Truman Library & Museum.

Across America and England, jubilant crowds fill the streets once more for an unofficial V-J (Victory over Japan) Day, as they had three months earlier on VE Day, May 8,1945, after Germany’s surrender ended the war in Europe.

A video clip of Truman’s August 14 announcement from C-Span.

V-J Day Times Square August 14, 1945 Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c19650

•September 2, 1945 A formal surrender ceremony is performed in Tokyo Bay and that date is also referred to as V-J Day.

Almost since the day the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, critics have second-guessed Truman’s decision and motives. A generation of historians and commentators have defended or repudiated the need for unleashing the atomic weapon. Admiral William D. Leahy, who was with Truman at Potsdam, later wrote in a memoir:

Once it had been tested, President Truman faced the decision as to whether to use it. He did not like the idea, but he was persuaded that it would shorten the war against Japan and save American lives. It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan.

–William D. Leahy, I Was There (1950)

In China, however, the Japanese surrender ended the wartime alliance between the Communists and Nationalists. The Chinese civil war began anew, with the US supporting Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Stalin’s USSR backing Mao Zedong’s Communists.

Read about Mao’s rise to power in Strongman: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy.

Many historians contend that preventing death and casualties in an invasion of Japan was only a partial explanation for the use of the two atomic bombs. The United States was already wary of Stalin and his designs on Japan’s wartime territory. They argue that the use of the two devices was meant to end the war quickly to prevent Stalin from capturing territory held by Japan. It may have also been a signal to Stalin and the Soviet Union that the United States possessed these weapons and was willing to use them.

In other words, the dropping of the atomic bombs became the first volley in the Cold War.

READ about the debate in this Smithsonian article.

In 1952, Albert Einstein –whose 1939 letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt had set the Manhattan Project in motion — wrote a brief essay published by a Japanese magazine Kaizo in which he stated:

I was well aware of the dreadful danger for all mankind, if these experiments would succeed. But the probability that the Germans might work on that very problem with good chance of success prompted me to take that step. I did not see any other way out, although I always was a convinced pacifist. To kill in war time, it seems to me, is in no ways better than common murder.

He concluded:

Gandhi, the greatest political genius of our time has shown the way, and has demonstrated the sacrifices man is willing to bring if only he has found the right way. His work for the liberation of India is a living example that man’s will, sustained by an indomitable conviction is stronger than apparently invincible material power.

–Source Hiroshima & Nagasaki Remembered

You can read more about Hiroshima and the dropping of the atomic bombs in Don’t Know Much About History and more about President Truman in Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents and in The Hidden History of America At War. Read more about Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin in STRONGMAN published on October 6, 2020.

August 20, 2021

Labor Day 2021

“Labor is the superior of capital and deserves much the higher consideration.”— Abraham Lincoln, “First Annual Message to Congress” (December 3, 1861)

To most Americans, the first Monday in September means a three-day weekend and the last hurrah of summer, a final outing at the shore before school begins, a family picnic. The federal Labor Day was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland during his second term in 1894.

With the enormous stresses placed on working people with the Covid pandemic in its second full year, lives have been altered with no end in sight.

“Americans worked less last year on average, but that was because mass layoffs in the spring meant fewer people were working at all. Among those who kept their jobs, there was little change in the amount of time spent working in a given day — about seven and a half hours in 2020, the same as in 2019.”

–“The Pandemic Changed How We Spend Our Time” New York Times (July 27, 2021)

As Nobel Prize-winning New York Times columnist Paul Krugman wrote in August 2021:

“And workers are, it seems, willing to pay a price to avoid going back to the way things were. This may, by the way, be especially true for older workers, some of whom seem to have dropped out of the labor force.”

–“Workers Don’t Want Their Old Jobs on the Old Terms”

As we rethink work and life, it is a most fitting moment to consider how we labor and the history of Labor Day.

The holiday was born at the end of the nineteenth century, in a time when work was no picnic. As America was moving from farms to factories in the Industrial Age, there was a long, violent, often-deadly struggle for fundamental workers’ rights, a struggle that in many ways was America’s “other civil war.” (From “The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day”)

“Glassworks. Midnight. Location: Indiana.” From a series of photographs of child labor at glass and bottle factories in the United States by Lewis W. Hine, for the National Child Labor Committee, New York.

The first American Labor Day is dated to a parade organized by unions in New York City on September 5, 1882, as a celebration of “the strength and spirit of the American worker.” They wanted among, other things, an end to child labor.

In 1861, Lincoln told Congress:

Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights. Nor is it denied that there is, and probably always will be, a relation between labor and capital producing mutual benefits. The error is in assuming that the whole labor of community exists within that relation.

Today, in postindustrial America, Abraham Lincoln’s words ring empty. Labor is far from “superior to capital.” Working people and unions have borne the brunt of the great changes in the globalized economy.

But the facts are clear: In the current “gig economy,” the loss of union jobs and the recent failures of labor to organize workers is one key reason for the decline of America’s middle class.

This excellent essay by former Labor Secretary Robert Reich explores the vast inequities existing in America’s economy.

Read the full history of Labor Day in this essay: “The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day” (2011)

Labor Day

“Labor is the superior of capital and deserves much the higher consideration.”— Abraham Lincoln, “First Annual Message to Congress” (December 3, 1861)

To most Americans, the first Monday in September means a three-day weekend and the last hurrah of summer, a final outing at the shore before school begins, a family picnic. The federal Labor Day was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland during his second term in 1894.

With the enormous stresses placed on working people with the Covid pandemic in its second full year, lives have been altered with no end in sight.

“Americans worked less last year on average, but that was because mass layoffs in the spring meant fewer people were working at all. Among those who kept their jobs, there was little change in the amount of time spent working in a given day — about seven and a half hours in 2020, the same as in 2019.”

–“The Pandemic Changed How We Spend Our Time” New York Times (July 27, 2021)

As we rethink work and life, it is a most fitting moment to consider how we labor and the history of Labor Day.

The holiday was born at the end of the nineteenth century, in a time when work was no picnic. As America was moving from farms to factories in the Industrial Age, there was a long, violent, often-deadly struggle for fundamental workers’ rights, a struggle that in many ways was America’s “other civil war.” (From “The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day”)

“Glassworks. Midnight. Location: Indiana.” From a series of photographs of child labor at glass and bottle factories in the United States by Lewis W. Hine, for the National Child Labor Committee, New York.

The first American Labor Day is dated to a parade organized by unions in New York City on September 5, 1882, as a celebration of “the strength and spirit of the American worker.” They wanted among, other things, an end to child labor.

In 1861, Lincoln told Congress:

Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights. Nor is it denied that there is, and probably always will be, a relation between labor and capital producing mutual benefits. The error is in assuming that the whole labor of community exists within that relation.

Today, in postindustrial America, Abraham Lincoln’s words ring empty. Labor is far from “superior to capital.” Working people and unions have borne the brunt of the great changes in the globalized economy.

But the facts are clear: In the current “gig economy,” the loss of union jobs and the recent failures of labor to organize workers is one key reason for the decline of America’s middle class.

This excellent essay by former Labor Secretary Robert Reich explores the vast inequities existing in America’s economy.

Read the full history of Labor Day in this essay: “The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day” (2011)

Who Said It? (Labor Day edition)

(Reposted from 2014)

Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration.

Abraham Lincoln (November 1863) Photo by Alexander Gardner

Abraham Lincoln, “First Annual Message to Congress” (“State of the Union”) December 3, 1861

It is not needed nor fitting here that a general argument should be made in favor of popular institutions, but there is one point, with its connections, not so hackneyed as most others, to which I ask a brief attention. It is the effort to place capital on an equal footing with, if not above, labor in the structure of government. It is assumed that labor is available only in connection with capital; that nobody labors unless somebody else, owning capital, somehow by the use of it induces him to labor. This assumed, it is next considered whether it is best that capital shall hire laborers, and thus induce them to work by their own consent, or buy them and drive them to it without their consent. Having proceeded so far, it is naturally concluded that all laborers are either hired laborers or what we call slaves. And further, it is assumed that whoever is once a hired laborer is fixed in that condition for life.

Now there is no such relation between capital and labor as assumed, nor is there any such thing as a free man being fixed for life in the condition of a hired laborer. Both these assumptions are false, and all inferences from them are groundless.

Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights.

Source and Complete text: Abraham Lincoln: “First Annual Message,” Read more about Lincoln, his life and administration and the Civil War in Don’t Know Much About® History, Don’t Know Much About® the Civil Warand Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

And read about the history of Labor Day in this post.

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

August 12, 2021

Who is “An Enemy of the People?”

[Originally posted May 12, 2020. Revised August 12, 2021]

“At least 53 Texas hospitals had intensive care units that were at maximum capacity. Two in Houston have been so overwhelmed that officials ordered overflow tents to be erected outside. In Austin, intensive care units were running short of beds. And in San Antonio, virus cases reached alarming levels not seen in months, with infants as young as 2 months tethered to supplemental oxygen.”

–“Texas Hospitals Are Overloaded with Virus Cases,” New York Times August 12, 2021

“We have reached our Dr. Stockman moment.”

I wrote that in May 2020.

It is now mid-August, a year later. And we are so far past our Dr. Stockman moment in ways we could not imagine a year ago, or even months ago, especially after vaccines were made available. As Adam Serwer writes about the Governor of Texas:

“The Texas governor’s warped priorities are allowing an extremist minority to worsen the pandemic.”

“The larger issue is that the conservative media’s devotion to undermining vaccination encourages Republican elected officials with political ambitions to make irresponsible public-health decisions, because they understand how media coverage shapes the attitudes of the GOP’s voters. Vaccine mandates for things such as school and air travel are supported by more than 60 percent of Texans, despite the state’s conservative lean. But Republican elected leaders fear the wrath of the GOP primary electorate more than they fear thousands of residents of their states dying of COVID-19.”

—“Greg Abbott Surrenders to the Coronavirus,” The Atlantic

Henrik Ibsen by Gustava Borgen (public Domain via Wikimedia)

In Ibsen’s classic drama, An Enemy of the People, Dr. Thomas Stockman has discovered that the waters in his town’s famed spa are poisoning the guests. He pleads with his brother, the Mayor, to close the lucrative attraction. But Mayor Peter Stockman refuses to shut down and repair the toxic baths.

“Have you taken the trouble to consider what your proposed alterations would cost?” the Mayor asks his brother. “And do you suppose anyone would come near the place after it had got about that the water was dangerous?”[1]

And there it is. Ibsen brings us to that place where economic health trumps public health.

Sound familiar? It should. Because we face a similar conflict today. A president and his administration are pushing to “reopen” the economy despite express warnings from medical experts about the perils of premature action.[2]

We have been down this road before. This is not the first time that the common good and the bottom line have faced off. In the midst of one pandemic, we need only look to the history of the 1918 pandemic, a story told in my book More Deadly Than War.

What was later called the Spanish flu emerged in March 1918, blossoming into an epidemic on army bases where young Americans were training for Europe’s trenches. After slacking in summertime, the outbreak returned in a second wave, even more swift and lethal, hitting American ports like Boston in September 1918. Striking down soldiers and sailors by the thousands, it jumped from the military to the civilian population. Seeing “bodies stacked like cordwood,” army doctors wondered if they were witnessing a new plague. The Spanish flu was carried to other ports and military bases, including those near Philadelphia.

But to Philadelphia’s civil authorities, it was “just the flu.” And Philadelphia was planning a parade – a grandiose show of patriotism and pride to promote the sale of Liberty Loans. These war bonds were marketed through an intense nationwide propaganda campaign that made buying these bonds an act of allegiance. Woe to those “slackers” who didn’t “do their part.”

Read Philadelphia Threw a WWI Parade That Gave Thousands of Onlookers the Flu

As Philadelphia planned its spectacle, the city’s director of public health knew better. A gynecologist, and an appointee loyal to Philadelphia’s notoriously corrupt political machine, Dr. Wilmer Krusen was warned to cancel the parade. But Dr. Krusen allowed the show to go on. He assured the public that recent military deaths were from “old-fashioned influenza or grip.”[3] His words were a harbinger of the president’s in January. “It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s going to be just fine.”[4]

It wasn’t. As the parade got underway on September 28, 1918, some 200,000 people jammed Philadelphia’s main street, packed eight deep on the sidewalks. Within seventy-two hours of that parade, every bed in Philadelphia’s hospitals was filled.[5]

On October 3, most public spaces –schools, churches, theaters, and pool halls –were officially closed.[6] The delayed lockdown to “flatten the curve” was too little, too late for many in the City of Brotherly Love. Within weeks, more than 12,000 people died in Philadelphia before the epidemic crested there.

Dr. Krusen was aware of the risks posed when he allowed the parade to step off. But he was answering to political and economic concerns, much like the Mayor in Ibsen’s play, and so many economists and administration officials echoing the president’s call to reopen the economy.

History is replete with Dr. Krusen’s counterparts—those scientists and other people who dared challenge authority. Take Giordano Bruno for example. Born in 1548, Bruno became a priest and a learned mathematician. But he was also a free thinker and, in 1584, published his concept that the sun, not the earth, was at the center of Creation.

Bruno was arrested and tried for this and other heresies during the Inquisition. Refusing to recant, the rebellious priest was sentenced as an impenitent heretic on papal orders. In February 1600, he was taken to the Campo de’ Fiori, an open market in Rome, his tongue in a gag, and burned alive.

Today, there is a statue honoring Giordano Bruno in the Campo de’ Fiori. There are no statues of Dr. Krusen. In modern parlance, Bruno was an “Upstander,” Dr. Krusen a “Collaborator.”

Close up of the statue of Giordano Bruno in the Camp de Fiori, Rome (Public Domain Wikipedia Commons)

Giordano Bruno would not serve a master who demanded that he deny the science that contradicted faith. He served the truth. Dr. Stockman refused to serve a master who placed profits over life and was ultimately branded “an enemy of the people.” Dr. Krusen chose instead to answer to his political masters.

This is the essential question now facing both American leadership and every individual. If we are to survive the current coronavirus, we need to carefully choose and serve a worthy master.

TEACHERS: If you would like a virtual visit to discuss this topic or any of my work, please get in touch with me. Here’s the link: Contact page.

[1] Henrik Ibsen, An Enemy of the People, Act II.

[2] https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation...

[3] John M. Barry, The Great Influenza, p. 204

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/15/op...

[5] Gina Kolata, Flu, p. 20.

[6] Barry, p. 220.

August 11, 2021

Who Said It? (8/11/2021)

President Harry S. Truman on August 14, 1945 in remarks outside the White House after announcing the unconditional surrender of Japan.

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

“This is the day we have been waiting for since Pearl Harbor. This is the day when Fascism finally dies, as we always knew it would.”

Read more about the final days of World War II in this post “The Month That Changed the World.”

Here are Truman’s remarks after meeting Stalin in July 1945.

August 9, 2021

The Memory Hole

Whose history is it? Who gets to tell it? And whose truth ends up in schoolbooks?

I pondered these questions after hearing President Biden address the recent ceremony honoring the police officers who defended the Capitol on January 6, 2021. During the event, the president said:

“The tragedy of that day deserves the truth above all else. We cannot allow history to be rewritten. We cannot allow the heroism of these officers to be forgotten. We have to understand what happened — the honest and unvarnished truth. We have to face it. That’s what great nations do.”

President Biden’s words recalled something another president articulated five years earlier:

“A great Nation does not hide its history; it faces its flaws and corrects them. This museum tells the truth: that a country founded on the promise of liberty held millions in chains…that the price of our Union was America’s original sin.”

— George W. Bush in dedicating the National Museum of African American History and Culture (9/24/2016)

At this moment, the United States is in a war over who gets to tell two pieces of history with extraordinary relevance and resonance. The story of the January 6 insurrection to overturn an election and subvert American democracy at the behest of a defeated president is one battle. The other is the titanic, racially-charged struggle over how we teach our children, and ourselves, about the country’s “original sin” – the Great Contradiction that a nation “conceived in liberty” was also born in shackles. That is no “theory” but a powerful thread of facts, events, and documents that course through the nation’s historical fabric.

That “winners write history” is a well-worn adage. The United States has clearly had its share of a history composed largely by one group of winners. They were white, Anglo men who threaded together a proud, patriotic tale of the birth of a nation. It dropped a great many stitches. It was for that reason that Founder John Adams would write,

“The history of our country will be one continued lie from one end to the other. The essence of the whole will be that Dr. Franklin’s electrical rod smote the earth and out sprang General Washington.”

Adams was not far off. For much of the nation’s existence, its narrative has been crafted into a tidy legend by men who helped create the shibboleth now called “American Exceptionalism.”

The United States has no monopoly on the desire to promulgate a blemish-free narrative of its past. In Italy, Mussolini once said,

“Our myth is the Nation, our myth is the greatness of the Nation! And to this myth, to this grandeur, that we wish to translate into a complete reality, we subordinate all the rest.”

–From Herman Finer, Mussolini’s Italy (1935), p. 218; quoted in Franklin Le Van Baumer, ed., Main Currents of Western Thought (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978), p.748.

The Soviet Union was notorious for its vanishing generals – men wiped from Kremlin photographs following each Stalinist purge. Japan balks at any mention of its wartime atrocities, including the mistreatment of captive Korean “comfort women.” And as China celebrated one hundred years of the Communist Party, the erasure of such events as mass starvation and the Tiananmen Square massacre is complete.

One notable exception has been Germany, where Holocaust studies including visits to concentration camp sites are mandatory in high school. On the other hand, it is worth noting that right-wing nationalist groups have been pushing back on the requirement. In Germany, writes The Atlantic’s Emily Schulthies, leaders of Alternative for Germany, a right-wing party, “have sought to diminish the importance of the Nazi era to produce an argument for renewed national pride: The party’s co-leader Alexander Gauland referred to it as a ‘speck of bird poop’ in Germany’s otherwise admirable history….” (The Atlantic, April 10, 2019)

Of course, the man who understood the control of history better than anyone was George Orwell.

“When one knew that any document was due for destruction, it was an automatic action to lift the flap of the nearest memory hole and drop it in, whereupon it would be whirled away on a current of warm air to the enormous furnaces….

–George Orwell, 1984 (p. 35)

Orwell’s “memory hole” demonstrated the unconstrained power of the Party to shape both history and language. It is a lesson on display at this moment –not in darkened corridors but in broad daylight as January 6 has emerged in some accounts as an ordinary tourist day and America’s racist past is buried by state legislators who can’t stand the truth.

Strongmen and dictators of every stripe understand the central importance of Orwell’s “memory hole.” Tyrants know how to destroy a set of facts and create new ones –the “Big Lie” that demands complete submission. As Mussolini’s Fascist creed put it: “Believe Obey Fight.”

While part of the historian’s work is to recover and restore the true record of what happened, the facts should never be consigned to the memory hole’s furnace in the first place. Replacing truth with “Big Lie” partisan narratives or indoctrination sessions is the devious work of propaganda meant to sway people to “Believe” and “Obey.”

Instead, we must stay vigilant, dedicated to Truth. That, after all, is what sets us free.

© 2021 Copyright Kenneth C. Davis All rights reserved

August 7, 2021

Don’t Know Much About® the Tonkin Resolution

[8/2016 post updated 8/7/2021]

What was the Tonkin Resolution?

USS Maddox Operating at sea, circa the early 1960s. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command

On August 7, 1964, Congress approved a resolution that soon became the legal foundation for Lyndon B. Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War. (New York Times)

It came in August 1964 with a brief encounter in the Gulf of Tonkin, the waters off the coast of North Vietnam where the U.S. Navy posted warships loaded with electronic eavesdropping equipment enabling them to monitor North Vietnamese military operations and provide intelligence to CIA-trained South Vietnamese commandos. One of these ships, the U.S.S. Maddox was reportedly fired on by gunboats from North Vietnam.

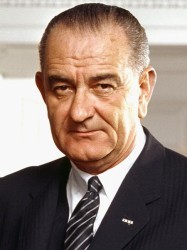

Lyndon B. Johnson (March 1964) Photo: Arnold Newman, White House Press Office

The reported attack came in the midst of LBJ’s 1964 campaign against hawkish Republican Barry Goldwater. President Johnson felt the incident called for a tough response and had the Navy send the Maddox and a second destroyer, the Turner Joy, back into the Gulf of Tonkin. A radar man on the Turner Joy saw some blips, and that boat opened fire. On the Maddox, there were also reports of incoming torpedoes, and the Maddox began to fire. There was never any confirmation that either ship had actually been attacked. Later, the radar blips would be attributed to weather conditions and jittery nerves among the crew.

According to Stanley Karnow’s Vietnam: A History,

“Even Johnson privately expressed doubts only a few days after the second attack supposedly took place, confiding to an aide, ‘Hell, those dumb stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish.’”

Johnson ordered an air strike against North Vietnam and then called for passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. This legislation gave the president the authority to “take all necessary measures” to repel attacks against U.S. forces and to “prevent further aggression.” The resolution not only gave Johnson the powers he needed to increase American commitment to Vietnam, but allowed him to blunt Goldwater’s accusations that Johnson was “timid before Communism.”

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution passed the House unanimously after only forty minutes of debate. In the Senate, there were only two voices in opposition. What Congress did not know was that the resolution had been drafted several months before the Tonkin incident took place. In June 1964, on LBJ’s orders, according to journalist-historian Tim Weiner,

“Bill Bundy, the assistant secretary of state for the Far East, brother of the national security adviser, and a veteran CIA analyst, had drawn up a war resolution to be sent to Congress when the moment was ripe.” (Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA, p. 280)

Congress, which has sole constitutional authority to declare war, had handed that power over to Johnson, who was not a bit reluctant to use it. One of the senators who voted against the Tonkin Resolution, Oregon’s Wayne Morse, later said,

“I believe that history will record that we have made a great mistake in subverting and circumventing the Constitution.”

After the vote, Walt Rostow, an adviser to Lyndon Johnson, remarked,

“We don’t know what happened, but it had the desired result.”

In January 1971, Congress repealed the Gulf of Tonkin resolution as popular opinion grew against a continued U.S. military involvement in Vietnam

Since Vietnam, United States military actions have taken place as part of United Nations’ actions, in the context of joint congressional resolutions, or within the confines of the War Powers Resolution (also known as the War Powers Act) that was passed in 1973, over the objections (and veto) of President Richard Nixon.”

The War Powers Resolution came as a direct reaction to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as Congress sought to avoid another military conflict where it had little input.

“The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and the Limits of Presidential Power” National Constitution Center

In 2005, the National Security Agency (NSA) issued a report reviewing the Tonkin incident in which it said “no attack had happened.” (Weiner, p. 280)

The National Endowment for the Humanities website Edsitement offers teaching resources on Tonkin and the escalation of the Vietnam War.

Read more about Vietnam, LBJ and his administration in Don’t Know Much About® History, Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents. The Vietnam War and the Tonkin Resolution are also covered in a chapter on the Tet offensive of 1968 in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR.

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

August 6, 2021

Don’t Know Much About® Hiroshima

Originally posted on August 6, 2020; updated August 6, 2021]

Seventy-six years ago on August 6, 1945, the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. At 8:15 local time, the first atomic bomb was detonated 1,986 feet above the city.

The atomic bomb cloud over Hiroshima Source: National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/542192

Hiroshima before the war was the seventh largest city in Japan, with a population of over 340,000, and was the principal administrative and commercial center of the southwestern part of the country. As the headquarters of the Second Army and of the Chugoku Regional Army, it was one of the most important military command stations in Japan, the site of one of the largest military supply depots, and the foremost military shipping point for both troops and supplies.

-Source: U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, June 1946

Shortly afterwards, the White House released a statement from President Harry S. Truman that had been drafted while he was attending the Potsdam Conference. Truman called Hiroshima “an important Japanese army base.”

We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories, and their communications. Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan’s power to make war.

It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.

Read: The Month That Changed the World for a timeline of events leading up to the end of World War II.

By June 1, Truman had apparently made his decision to use the atomic bomb to end the war with Japan. But the bomb had not yet been tested. Once the bomb had been successfully detonated in the New Mexico desert, the decision to use it moved forward, a fateful choice that was set against the recent American experience on Okinawa, where more than 12,500 Americans and more than 100,000 Japanese had died in brutal combat.

When the Japanese said they would fight to the death rather than make an unconditional surrender, the final decision was cast. Winston Churchill later summarized the decision: “To avert a vast, indefinite butchery.”

-From Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents

After the war, a United States survey team assessed the impact of the Hiroshima bomb.

“Practically the entire densely or moderately built-up portion of the city was leveled by blast and swept by fire. A ‘fire-storm’, a phenomenon which has occurred infrequently in other conflagrations, developed in Hiroshima: fires springing up almost simultaneously over the wide flat area around the center of the city drew in air from all directions. The inrush of air easily overcame the natural ground wind, which had a maximum velocity of 30 to 40 miles per hour two to three hours after the explosion. The ‘fire-wind’ and the symmetry of the built-up center of the city gave a roughly circular shape to the 4.4 square miles which were almost completely burned out.

The surprise, the collapse of many buildings, and the conflagration contributed to an unprecedented casualty rate. Seventy to eighty thousand people were killed, or missing and presumed dead, and an equal number were injured. (Emphasis added)

—Source: U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, June 1946

What history has confirmed is that some of the men who created the bomb didn’t understand how horrifying its capabilities were. Of course, they understood the destructive power of the bomb, but radiation’s dangers were far less understood. As author Peter Wyden tells it in Day One, an account of the making and dropping of the bomb, scientists involved in creating what they called “the gadget” believed that anyone who might be killed by radiation would die from falling bricks first.

“The survivors, known as hibakusha, sought relief from their injuries. However, 90 percent of all medical personnel were killed or disabled, and the remaining medical supplies quickly ran out. Many survivors began to notice the effects of exposure to the bomb’s radiation. Their symptoms ranged from nausea, bleeding and loss of hair, to death. Flash burns, a susceptibility to leukemia, cataracts and malignant tumors were some of the other effects.

–“The Story of Hiroshima,” Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered

The heat was tremendous . And I felt like my body was burning all over. For my burning body the cold water of the river was as precious as the treasure. Then I left the river, and I walked along the railroad tracks in the direction of my home. On the way, I ran into an another friend of mine, Tokujiro Hatta. I wondered why the soles of his feet were badly burnt. It was unthinkable to get burned there. But it was undeniable fact the soles were peeling and red muscle was exposed.

—Mr. Akihiro Takahashi, who was 14 years old, when the bomb was dropped

On August 9, a second bomb, code named Fat Man, was detonated above Nagasaki.

Like Hiroshima, the immediate aftermath in Nagasaki was a nightmare. More than forty percent of the city was destroyed. Major hospitals had been utterly flattened and care for the injured was impossible. Schools, churches, and homes had simply disappeared. Transportation was impossible.

—Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered

Many historians contend that preventing death and casualties in an invasion of Japan was only a partial explanation for the use of the two atomic bombs. The United States was already wary of Stalin and his designs on Japan’s wartime territory. They argue that the use of the two devices was meant to end the war quickly to prevent Stalin from capturing territory held by Japan. It may have also been a signal to Stalin and the Soviet Union –which had declared war on Japan and moved troops into Manchuria– that the United States possessed these weapons and was willing to use them.

In other words, the dropping of the atomic bombs became the first volley in the Cold War.

August 6 and 9 should not be days to argue about the politics of the bomb. They should be days of solemn remembrance of the victims. And of contemplating the horrific power of the weapons we create.

The City of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and Museum offers an English language website with a history of Hiroshima and the effects of the bombing.

Photo of what became later Hiroshima Peace Memorial among the ruins of buildings in Hiroshima, in early October, 1945, photo by Shigeo Hayashi. (Source Wikimedia Commons)

In 1939, physicist Albert Einstein had written a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt that resulted in the creation of the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb. In 1948, Einstein was quoted by an interviewer as saying:

If I had foreseen Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I would have torn up my formula in 1905.

-Quoted in Einstein and the Poet : In Search of the Cosmic Man (1983) by William Hermanns

In 2016, President Barack Obama became the first sitting U.S. President to visit Hiroshima.

August 3, 2021

The Month That Changed The World: July 16-August 15, 1945

[Originally posted in 2020 to mark the 75th Anniversary of the end of World War II and the transformation of the modern world; Revised August 3, 2021]

From the “Trinity” Test to Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Japan’s Surrender:

The Month That Changed the World

Formal surrender aboard USS Missouri Sept. 2. 1945 https://www.history.navy.mil/our-coll...

The following timeline summarizes the extraordinary series of events that helped make the modern world between July 16 and August 15, 1945.

The Atomic Bomb Dome-Hiroshima (Photo Courtesy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered)

On August 6, 1945, the New York Times asked:

“What is this terrible new weapon?”

(New York Times, August 6, 1945: “First Atomic Bomb Dropped on Japan”)

The story followed the announcement made that day by President Harry S. Truman:

“SIXTEEN HOURS AGO an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of T.N.T. It had more than two thousand times the blast power of the British ‘Grand Slam’ which is the largest bomb ever yet used in the history of warfare.”

August 6, 1945

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

(“Statement by the President Announcing the Use of the A-Bomb at Hiroshima”: Truman Library and Museum)

The use of the first atomic bomb followed the successful test detonation –the goal of the wartime Manhattan Project — and the beginning of a series of world-changing events.

• July 16, 1945 the first atomic device, nicknamed “the Gadget,” is detonated in the “Trinity” test at Alamogordo, New Mexico. Read this account of the test in National Geographic.

New York Times reporter Dennis Overbye visited the site in 2021. His report “Touring Trinity, the Birthplace of Nuclear Dread”:

“The detonation created a crater eight feet deep, a half-mile wide and lined with glassy pebbles called trinitite: sand that had been swept up in the fireball, vaporized and then fell back down in molten radioactive droplets.”

The Trinity test, 15 seconds after detonation. Photo courtesy of David Wargowski Source: National Museum of Nuclear Science & History

In the course of the next weeks, the world would be transformed, with the arrival of the Atomic Age, Japan’s surrender, the end of World War II, the charter of the United Nations, and the beginning of the Cold War.

The development, testing, and use of atomic bombs is documented by the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History.

• July 17 In Potsdam, near Berlin in defeated Germany, President Harry S. Truman comes face to face with the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. Truman had taken office upon the death of President Roosevelt on April 12, 1945 without knowledge of the Manhattan Project or the atomic bomb’s existence. Having been told about the potential weapon, Truman is informed of the successful “Trinity” test while meeting Stalin with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the European postwar conference.

Harry S. Truman and Joseph Stalin at Potsdam (Public Domain: President Harry S. Truman Library and Museum)

“I told Stalin that I am no diplomat but usually said yes or no to questions after hearing all the argument.”

Read about Stalin’s rise to power in Strongman

Following the New Mexico test success, the components of the atomic bomb are loaded onto the USS Indianapolis in San Francisco for transport to an airbase on Tinian Island in the Pacific. Many of the crew of nearly 1,200 men have no idea what the ship is carrying.

•July 19 In the United States, Congress approves the Bretton Woods agreement, an international pact designed to avoid postwar financial crises like those that followed World War I. The agreement creates the International Money Fund and what later becomes the World Bank.

The Japanese cities of Choshi, Hitachi, Fukui and Okazaki are struck by 600 B-29 Superfortress bombers dropping some 4,000 tons of bombs — the largest employment of the bomber to date.

The USS Indianapolis reaches Pearl Harbor in the first leg of its voyage to deliver the atomic bomb components.

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/515009

• July 21 “A senior US Army Air Force intelligence officer in the Pacific distributed a report declaring: ‘The entire population of Japan is a proper Military Target . . . THERE ARE NO CIVILIANS IN JAPAN.’” Richard B. Frank via World War II Museum.

In Potsdam, Truman and Churchill privately agree to use the atomic bomb if Japan does not surrender. Read about Truman’s decision from the National Park Service Harry S. Truman National Historic Site.

• July 22 In what is described as the last surface battle of World War II, the U.S. Navy sinks Japanese supply ships in the “Battle of Sagami Bay” (“Tokyo Bay”). Naval bombardments of the Japanese mainland continue, along with B-29 bombing raids striking Japanese cities.

In China, the American Far East Air Force attacks Japanese troops, airfields, and shipping near Shanghai.

• July 23 In Potsdam, Secretary of War Henry Stimson receives atomic bomb target list. In order of choice they are: Hiroshima, Kokura, and Niigata. He also receives an estimate of atomic bomb availability: “Little Boy” should be ready for use on Aug. 6, second “Fat Man-type” by Aug. 24. There are plans for a total of seven bombs available by December.

• July 24 Truman informs Stalin of a “new weapon of unusual destructive force.”

“In which I tell Stalin we expect to drop the most powerful explosive ever made on the Japanese. He smiled and said he appreciated my telling him–but he did not know what I was talking about–the Atomic Bomb! HST”

Truman’s note on back of photograph from Potsdam Conference describing his conversation with Stalin about the atomic bomb. Source: Truman Museum https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/photogr...

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

But Stalin already knows about the atomic bomb because of a network of spies inside the Manhattan Project. The Soviet push to capture Berlin in April and May 1945 was motivated in part by Stalin wanting to capture German scientists working on a Nazi atomic bomb and tons of uranium held in a Berlin lab. This episode is recounted in the “Berlin Stories” chapter of my book The Hidden History of America at War.

• July 25 Truman writes in his diary that he has made the decision to use “the most destructive bomb in the history of the world… I have told the Sec. of War, Mr. Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children.”

Sources: Truman Library and Museum National Security Archive, George Washington University

• July 26 British general election returns are announced; Prime Minister Winston Churchill is defeated and replaced by Clement Attlee.

“The landslide victory comes as a major shock to the Conservatives following Mr Churchill’s hugely successful term as Britain’s war-time coalition leader, during which he mobilised and inspired courage in an entire nation.”

U.S. Propaganda poster (Source National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/513563)

–BBC

At the Potsdam Conference, the Potsdam Declaration demands an “Unconditional surrender” by Japan. Issued by Great Britain, China, and the U.S., it threatens:

“The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

The USS Indianapolis reaches Tinian that day.

USS Indianapolis 10 July 1945, after final overhaul and repair of combat damage. Photograph from the Bureau of Ships Collection in the U.S. National Archives (Naval History and Heritage Command https://usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.m...)

“Indianapolis departed San Francisco on 16 July 1945, foregoing her post-repair shakedown period. Touching at Pearl Harbor on 19 July, she raced on unescorted and reached Tinian on 26 July, covering some 5,000 miles from San Francisco in only ten days.”

After delivering the atomic bomb components, the ship departs for Guam and the Philippines.

• July 27 American B-29 SuperFortress bombers drop 600,000 leaflets over eleven Japanese cities warning that they are targets of bombings.

“But, unfortunately, bombs have no eyes. So, in accordance with America’s humanitarian policies, the American Air Force, which does not wish to injure innocent people, now gives you warning to evacuate the cities named and save your lives.” –from a “LeMay Leaflet,” named for General Curtis LeMay, architect of the Pacific bombing campaign (Atomic Heritage Foundation)

In England, Winston Churchill has a final meeting with his joint chiefs of staff.

• July 28 In New York City, an Army B-25 bomber on a routine mission flies into the Empire State Building –then the world’s tallest skyscraper. Three crew members and eleven people in the building are killed.

“B-25 Mitchell bomber smashed beyond recognition into Empire State Building. This is a picture of the wreckage-strewn 79th floor where the bomber tore a 18-foot hole in wall. Propeller is embedded in the wall at the left.” Source: New York Daily News

“I was at the file cabinet and all of a sudden the building felt like it was just going to topple over,” [office worker Gloria] Pall said. “It threw me across the room, and I landed against the wall. People were screaming and looking at each other. We didn’t know what to do. We didn’t know if it was a bomb or what happened. It was terrifying.” Source: National Public Radio

In Potsdam, newly-elected Prime Minister Clement Attlee of the Labour Party arrives to rejoin the talks which are nearly concluded. Attlee led post-war UK until 1951.

“As Prime Minister, he enlarged and improved social services and the public sector in post-war Britain, creating the National Health Service and nationalising major industries and public utilities. Attlee’s government also presided over the decolonisation of India, Pakistan, Burma, Ceylon and Jordan, and saw the creation of the state of Israel upon Britain’s withdrawal from Palestine.” Official UK Biography of Attlee.

• July 29 The Japanese government rejects the Potsdam Declaration surrender demand.

Just after midnight, the Indianapolis is struck by a Japanese torpedo.

• July 30 Torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, the Indianapolis sinks in twelve minutes. Between 800 and 900 of the crew of nearly 1,200 are plunged into the shark-infested waters.

“What followed was an ordeal of hell on earth for those who survived the sinking. For a whole host of reasons, many related to the secrecy of her atom bomb mission, the rest of the Navy did not know that Indianapolis was missing.”

— Sam Cox (Rear Adm., USN, Ret.), “Lest We Forget: USS Indianapolis and her sailors”

–Read “The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis” via the National Archives including a film clip from the classic scene in Jaws in which Captain Quint describes the sinking of the ship and the shark attacks that followed.

• July 31 The assembly of the atomic bomb, code named “Little Boy,” is completed. The final arming of the bomb will be done in-flight.

In Potsdam, Truman is notified of the bomb being ready. He writes a message that concludes:

“Release when ready, but not sooner than August 2. HST”

According to the Truman Library:

The actual reply that President Truman wrote on July 31, 1945 (Photo taken by Dawn Wilson at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library)

“No known written record exists in which Harry Truman explicitly ordered the use of atomic weapons against Japan. The closest thing to such a document is this handwritten order, addressed to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, in which Truman authorized the release of a public statement about the use of the bomb. It was written on July 31, 1945 while Truman was attending the Potsdam Conference in Germany. In effect, this served as final authorization for the employment of the atomic bomb, though the expression ‘release when ready’ refers to the public statement.”

• August 1 The atomic bomb is ready and flight orders are prepared. But weather delays the mission. Of four potential target cities, Hiroshima is chosen as the primary target.

In Potsdam that day, the Big Three wrap up their meetings and discuss plans for the trials of war criminals that later become known as the Nuremberg Trials.

Read my 2021 post on the Nuremberg Trials.

In the Pacific, hundreds of survivors from the Indianapolis desperately try to stay afloat in the shark-infested waters.

“In that clear water you could see the sharks circling. Then every now and then, like lightning, one would come straight up and take a sailor and take him straight down.” – Survivor of the Indianapolis sinking to the BBC.

• August 2

The Big Three at the end of the Potsdam Conference: Front row (Left to Right) Prime Minister Attlee, President Truman, Generalissimo Stalin. Source: Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives.

Shortly after midnight on August 2, the Potsdam Conference concludes with a joint communique. It includes reference to the United Nations, whose organization and charter had been completed on June 26 at a conference in San Francisco.

Truman speaks of a future Washington meeting with the Soviet leader, but he and Stalin never meet again.

What was clear was that the Conference had solidified the Soviet Union’s domination over much of Eastern Europe, including the eastern half of a divided Germany. Admiral William D. Leahy, Truman’s Chief of Staff, later wrote:

“The Soviet Union emerged at this time as the unquestioned all-powerful influence in Europe….”

The U.S. Navy is still unaware that the Indianapolis has gone down. More than 800 men went into the water and the survivors are spotted by a reconnaissance plane four days after the sinking.

“Marks’s crew dropped rubber rafts and supplies as they witnessed continuing shark attacks. Disregarding orders not to land at sea, the pilot touched down and began taxiing to pick up survivors.

As darkness set in, and as Marks waited for rescue vessels, he pulled men from the water into his aircraft. When the plane’s fuselage was at maximum capacity, survivors were tied to the wings with parachute cord. The pilot and his crew rescued a total of 56 men. Once signaled, a total of seven Navy ships converged on the site and rescued the remaining men. Only 317 sailors survived.” –National Archives, “The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis”

Indianapolis’ survivors en route to a hospital following their rescue, early August 1945. Source: Naval History and Heritage Command

• August 4 Colonel Paul Tibbets briefs the men of the 509th Composite Group -the weapon delivery arm of the Manhattan Project. Tibbets is the commander of the unit. His men do not know the nature of the bomb they will carry.

• August 5 The bombing mission is confirmed and Colonel Paul Tibbets announces he will pilot the plane which he names “Enola Gay,” after his mother.

Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr., Pilot of the Enola Gay, the Plane that Dropped the Atomic Bomb August 6, 1945 (National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/535737)

• August 6 At 0245 local time on Tinian,

“Enola Gay begins takeoff roll. [Pilot] Colonel Paul Tibbets says to co-pilot Robet Lewis, ‘Let’s go.’ He pushes all of the throttles forward. The overloaded Enola Gay lifts slowly into the night sky, using all of the more than two miles of runway.”

—Atomic Heritage Foundation, minute-by-minute timeline of Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings.

0730:

“Tibbets announces to the crew: ‘We are carrying the world’s first atomic bomb.’ He pressurizes the Enola Gay and begins an ascent to 32,700 feet. The crew puts on their parachutes and flak suits.” (Atomic Heritage Foundation)

8:15 AM (Hiroshima local time) The first atomic bomb is detonated over Hiroshima.

“In less than one second, the fireball had expanded to 900 feet. The blast wave shattered windows for a distance of ten miles and was felt as far away as 37 miles. Over two-thirds of Hiroshima’s buildings were demolished. The hundreds of fires, ignited by the thermal pulse, combined to produce a firestorm that had incinerated everything within about 4.4 miles of ground zero.”

Source: Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered.

“In the street, the first thing he saw was a squad of soldiers who had been burrowing into the hillside opposite, making one of the thousands of dugouts in which the Japanese apparently intended to resist invasion, hill by hill, life for life; the soldiers were coming out of the hole, where they should have been safe, and blood was running from their heads, chests, and backs. They were silent and dazed.

Under what seemed to be a local dust cloud, the day grew darker and darker.”

–John Hersey, “Hiroshima,” New Yorker (August 24, 1946)

In Hiroshima, the estimated death toll reaches eighty thousand people killed instantly; as many as 90 percent of the city’s nurses and doctors also die instantly. By 1950, as many as 200,000 die as a result of long-term effects of radiation.

Hiroshima After Bombing (Source National Archives Identifier 148728174)

In his official announcement, President Truman said,