Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 23

April 27, 2022

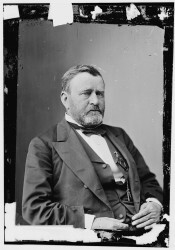

Don’t Know Much About U.S. Grant

Born on April 27, 1822 –2oo years ag0– the 18th President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant

April 27, 1822 Born in Point Pleasant, Ohio

1839-1843 Attended West Point

1843-1853 Served in the Mexican War and a succession of U.S. Army posts, then resigned his commission.

1854-1858 Farmed near St. Louis, Missouri

1860-1861 Clerked in tannery store at Galena, Illinois

1861-1865 Served in Civil War; commanded all Union Armies

1869-1877 18thPresident

1880 Unsuccessful candidate for Republican presidential nomination

July 23, 1885 Died at Mt. McGregor, New York, aged 63

The country having just emerged from a great rebellion, many questions will come before it for settlement in the next four years which preceding Administrations have never had to deal with. In meeting these it is desirable that they should be approached calmly, without prejudice, hate, or sectional pride, remembering that the greatest good to the greatest number is the object to be attained.

This requires security of person, property, and free religious and political opinion in every part of our common country, without regard to local prejudice. All laws to secure these ends will receive my best efforts for their enforcement.

–Ulysses S. Grant, First Inaugural (March 4, 1869

The conquering hero of the Union, Ulysses S. Grant did not look the part. He was short, scruffy, favored enlisted men’s uniforms, and was dogged by reports of his fondness for drink –a somewhat undeserved reputation. Grant clearly was a drinker at times in his life, but the image of him as a stumbling drunk is a caricature. One successor, Theodore Roosevelt later called him, “The Hammer of the North,” and wrote,

“Grant’s supreme virtue was his doggedness….He was master of strategy and tactics, but he was also a master of hard-hitting. …His name is among the greatest in our history.”

There is no question that he was a dogged, determined general whose command skills helped win the war for the Union. Unfortunately, those strengths did not translate into the complexities of leading the large, swiftly growing, and rapidly changing nation. Another of his successors, James A. Garfield, who served on the battlefield under Grant, once said,

“He has done more than any other President to degrade the character of Cabinet officers by choosing them on the model of the military staff, because of their pleasant personal relationship to him and not because of their national reputation and public needs.”

Garfield was right. Personally honest, Grant was notoriously inept when it came to surrounding himself with men who were corrupt, both in private and as president. Some of them blackened his Presidency; others would reduce Grant to bankruptcy. Finally, a third later successor, Woodrow Wilson, once wrote of him, “The honest, simple-hearted soldier had not added prestige to the presidential office. He himself knew he had failed… that he ought never to have been made president.”

One reason that Grant has been positively reevaluated as President, however, was his commitment to achieving the vote for African Americans. In his 1874 Message to Congress, he said:

Treat the negro as a citizen and a voter, as he is and must remain, and soon parties will be divided, not on the color line, but on principle.

Fast Facts

Religion: Methodist (Although raised Methodist, Grant never officially joined a church.)

Education: United States Military Academy (West Point)

Career before Politics: Soldier, farmer, leather shop clerk

Military Service: U.S. Army- Mexican War, Civil War

Political Party: Republican

First Lady: Julia Boggs Dent Grant (January 26, 1826-December 14, 1902) Grant’s best man was West Point classmate James Longstreet, later a Confederate general who attended Lee’s surrender in April 1865.

Children: Frederick, Ulysses S.Grant, Jr. (“Buck”), Ellen (“Nellie”), and Jesse Root Grant

Grant is the first of seven presidents born in Ohio (second-most from one state after Virginia).At age 46, Grant was the youngest president elected up to that time.After Grant’s death in 1885, more than 60,000 people marched and one million spectators watched the funeral procession to his burial in New York’s City Upper West Side.Twelve years later, Grant’s Tomb was dedicated. Built with $600,000 donated by more than 90,000 people, it is the largest mausoleum in North America. Once again, more than one–million people attended the parade and dedication ceremony when Grant was interred in the tomb on April 27, 1897. Grant’s wife, Julia, was also interred –not buried—in Grant’s Tomb, after her death in 1902. It is the site of the General Grant National Memorial (NPS).

April 26, 2022

How to Develop an Inquiring Mind–And Why We Must

Like the ancient Greeks who stood on the beach, looked at the night sky and asked questions about where the moon went in the daytime, or why the tides shifted, we all must open our minds to the power of curiosity.

We are living in an age of misinformation and disinformation. Today, the most basic notions of truth, science, sound medical advice, and historical facts are under assault at the highest levels of government around the world as well as in the mass media. Propaganda has become a weapon as powerful and poisonous as many of the conventional and unconventional threats we have long been made to fear.

The dangers posed to democracy and freedom, along with an existential climate crisis and the most deadly pandemic in a century, are the most dire threats America has experienced in my lifetime, far surpassing the Cold War’s risks. I write and say that without exaggeration. It ought to set off alarm bells for everyone.

The question is — what do we do about it?

To combat this assault on reality and truth, the skills of learning and thinking are more important than ever. To be better teachers, parents, students, and citizens requires all of us to become more inquiring and media literate. We need to seek quality information from reliable sources at the same time we embrace healthy skepticism. We need to exercise our curiosity—the basic human instinct that has driven progress, innovation, and invention. But we need to understand how to discern what is true.

I have spent my life asking questions, doing research, and seeking answers. And I would like to share some observations. I promise not to offer any pedagogy. I can’t even use the word in a sentence.

Here are some basic principles that are the backbone of the approach I use as a writer, historian, and classroom lecturer. I plan to expand on some of these points in this space during the coming weeks and months:

#1—Ask questions—who, what, when, where and why are words that can open doors

#2—Identify experts and reliable sources, and use primary documents

#3—Understand that learning is teaching and teaching is learning

#4—Create and adopt a learning demeanor and see life itself as a school

#5—Place books, reading, and libraries at the center of our personal education—resolve to read

#6—Explore media literacy and learn who and what you can trust

#7—Know what you don’t know

#8—Identify the threat of the “wisdom of the crowd” or “tribe”

#9— Beware the arrogance of certainty and those “experts” who profess they know the truth and even punish or kill those who disagree

#10—Avoid the pitfall of “following” and appreciate the value of “unfollowing”

These techniques will only grow more valuable as we move into a heightened era of misinformation possibly dominated by Artificial Intelligence. All the more reason to argue for Natural Intelligence.

We stand at a flashpoint of historical dimensions. Both in the United States and elsewhere around the world, there are basic challenges to democracy, freedom, human rights, and decency taking place. The moment seems to confirm H.G. Wells’s dire 1920 prediction that, “Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe.”

Only by learning, thinking, and knowing can we actually challenge those who would turn off the spigots of information. That may give us our best chance to avert catastrophe.

[Read my earlier essay “Democracy is Not a Spectator Sport” in Social Education (September 2019), the journal of the National Council for the Social Studies]

© Copyright 2022 Kenneth C. Davis All rights reserved

April 15, 2022

Greatest American Speech?

On March 4, 1865, Abraham Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address. Just 701 words long, Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address took only six or seven minutes to deliver. And yes, it is the greatest American speech.

One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war.

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Source and Complete Text: The Avalon Project

At a White House reception, President Lincoln encountered Frederick Douglass. “I saw you in the crowd today, listening to my inaugural address,” the president remarked. “How did you like it?” “Mr. Lincoln,” Douglass answered, “that was a sacred effort.” (Source: Gilder Lehman Institute of American History)

“The Martyr of Liberty” via Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/item/scsm000402/

On April 15, 1865 –weeks after he delivered that address– Lincoln died at the hand of assassin John Wilkes Booth.

(Linked resources via Library of Congress)

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

April 13, 2022

What do we do about Mr. Jefferson?

(Revision of April 13, 2012 post)

“That these are our grievances which we have thus laid before his majesty, with that freedom of language and sentiment which becomes a free people claiming their rights, as derived from the laws of nature, and not as the gift of their chief magistrate: …. (Kings) are the servants, not the proprietors of the people.”

–Thomas Jefferson, A Summary View of the Rights of British America (1774)

Born on April 13, 1743 at Shadwell, his father’s estate in Albermarle County, Virginia, Thomas Jefferson embodied what I call the “Great Contradiction”–that a nation “conceived in liberty” was also born in shackles.

Read my article on teaching the “American Contradiction” in Social Education.

Jefferson was the son of a planter and surveyor, Peter Jefferson and his wife, Jane Randolph Jefferson, who came from one of Virginia’s wealthiest families. Thomas Jefferson’s father had moved the family to the Tuckahoe plantation owned by William Randolph, which Peter Jefferson managed as executor.

The third child in a family of ten and oldest son, Thomas was a bookish boy who studied with a local clergyman and later at a school in Fredericksburg with Reverend James Maury who taught Jefferson the classics in their original languages. Thomas was fourteen when his father died, leaving the boy head of an estate with about 2,500 acres and thirty enslaved people.

The Declaration’s future author distinguished himself early as a scholar at the College of William and Mary, and gained admission to the Virginia bar in 1767. His literary prowess, demonstrated in A Summary View of the Rights of British America, prompted John Adams to put Jefferson forward as the man to write the Declaration, a task he accepted with reluctance.

Most of the war years were spent in Virginia as a legislator and later as governor, a period of some controversy as he was criticized for failing to aggressively defend Virginia against British attacks. He barely escaped capture in Richmond in 1781, a story told in my book In the Shadow of Liberty.

After his wife’s death in 1783, he served as ambassador to France, where he could observe firsthand the French Revolution. It was here that Jefferson is believed to have begun his relationship with Sally Hemings, the enslaved 14-year-old thought to be half-sister of Jefferson’s dead wife, Martha.

Returning to America in 1789, Jefferson became Washington’s secretary of state and began to oppose what he saw as a too-powerful central government under the new Constitution, bringing him into a direct confrontation with his old colleague John Adams and, more dramatically, with Alexander Hamilton.

Running second to Adams in 1796, he became vice president, chafing at the largely ceremonial role. In 1800, Jefferson and fellow Democratic-Republican Aaron Burr tied in the Electoral College vote, and Jefferson took the presidency in a tense and controversial House vote that required more than 30 ballots.

While President, Jefferson engineered the Louisiana Purchase and wrote what may be his second most famous lines in a letter addressing religious freedom under the new American government.

Jefferson to Danbury Baptists (Monticello)

i

“Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legislative powers of government reach actions only, and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between church and State. Adhering to this expression of the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience, I shall see with sincere satisfaction the progress of those sentiments which tend to restore to man all his natural rights, convinced he has no natural right in opposition to his social duties.”

–Thomas Jefferson

Letter to the Danbury Baptist Association, (January 1, 1802)

After two terms, he returned to his Monticello home to complete his final endeavor, building the University of Virginia. As he lay dying, Jefferson would ask what the date was, holding out, like John Adams, until July 4, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration.

With the advantage of hindsight, cynicism about Thomas Jefferson is easy. But the baffling question remains: How could a man who embodied the idealism of the Enlightenment enslave Black people –and it is widely assumed — father children by one of them? What do we do about Thomas Jefferson?

There is no satisfying answer. Earlier in his life, he had unsuccessfully argued against aspects of slavery. At worst, Jefferson may not have thought of slaves as men, not an unusual notion in his time. And he was a man of his times. He was completely dependent upon slavery for his financial life and the political power of his southern slave-holding class. Like other men, great and small, he was not perfect.

Jefferson’s life, writings, and politics are discussed in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents from which this material is adapted.

His relationship with the enslaved people of Monticello is explored in detail in my book In the Shadow of Liberty.

April 10, 2022

When Robin Hood Was Blacklisted

Robin Hood was a Commie.

That, at least, is what an Indiana state textbook commissioner thought back in 1953. This official called for schools to ban books mentioning Robin Hood for the simple reason that Robin and his Merry Men robbed from the rich and gave to the poor. Their antics reeked suspiciously of godless Socialism.

It is easy to laugh off this overlooked history as an amusing bit of trivia. Except the Hoosier state assault on Robin Hood was part of a larger nationwide effort to ban books and suppress intellectual freedom. It was led by Senator Joseph McCarthy during the anti-Communist “witch hunts.” It targeted books, writers, and libraries both at home and around the world. And it holds pointed lessons about safeguarding democracy from the forces threatening it today.

After the 1947 blacklisting of the “Hollywood Ten” screenwriters by the House Un-American Affairs Committee (HUAC), Senator McCarthy emerged as the face and unrelenting voice of a crusade against Communist influences in America. In 1950, McCarthy claimed to possess an extensive list of Communists who worked in the State Department. Launching his war on alleged Communist infiltrators as chairman of a Senate committee on government operations, McCarthy was abetted by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. To be labeled a Communist was an accusation from which there was no escape. Claims of innocence or invoking the Fifth Amendment were tantamount to confession.

Set against the Korean War begun in 1950, and with the convictions of Alger Hiss that year for perjury over espionage and the Rosenbergs in 1951 for atomic spying, America’s fear of Communism spread like wildfire. Gaining an army of rabid followers, McCarthy’s crusade to root out subversives widened to focus intently on libraries, which were pressured to purge their collections of works by Marx. By 1952, the New York Times described a pervasive wave of educational book censorship in America. Around the country, self-appointed local committees— “volunteer educational dictators” in the words of one librarian—were coercing librarians to remove books considered “un-American,” the Times found.

This anti-Communist juggernaut was not only steam-rolling domestic libraries. McCarthy sent it on a road trip. In April 1953, McCarthy’s underlings, attorney Roy Cohn and associate David Schine, were dispatched to Europe. Part of their mission was to scrutinize U.S. Information Service libraries, created to provide war-ravaged countries with American books. McCarthy claimed that these collections held thousands of works by Communists. Targeting suspect authors, just as Hollywood had been purged of “Red” screenwriters, Cohn and Schine succeeded in intimidating foreign service officials. No fires were set, but titles by Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, and Howard Fast, among others, were pulled from the shelves.

Inaugurated in January 1953, President Eisenhower was hesitant to challenge McCarthy. But he discreetly fired back. He told a Dartmouth commencement audience in June of that year:

“Don’t join the book burners. Don’t think you are going to conceal faults by concealing evidence that they ever existed. Don’t be afraid to go in your library and read every book, as long as that document does not offend our own ideas of decency.”

–President Eisenhower, “Remarks at the Dartmouth College Commencement”

Unfortunately, Eisenhower’s defense of reading was less than full-throated. Ultimately, his State Dept. folded to McCarthy’s men.

“Only reckless men, under these conditions, could choose to take steps offensive to McCarthy since the President and the Secretary [of State John Foster Dulles] have rarely backed up their subordinates whom McCarthy has singled out for attack.”

—The New Republic June 29, 1953

But America’s librarians were not about to be silenced. Despite the stale caricature of an old lady in a bun shushing the patrons, many librarians spoke out, daringly, given the nation’s fearful mood and threats to their jobs. Responding to this mounting pressure, the American Library Association (ALA), in concert with the American Association of Publishers, issued in June 1953 a “Freedom to Read” statement –since revised several times—that begins, “The freedom to read is essential to our democracy. It is continuously under attack.”

Unfortunately, the ALA was right then—and now. Ike’s “book burners” are back—or perhaps it is more accurate to say they never left. Across America, a concerted effort to purge school and public libraries of “offensive” literature has found new vigor and a louder voice. There is a long history of attempts to rid libraries of books considered objectionable—it is the reason the ALA launched its annual Banned Books Week forty years ago to highlight local challenges to books. But these perennial community-level attempts to challenge books deemed “subversive” or “indecent” have reached a new level of intensity.

Currently, in America’s riven political ecosystem, the hyper-charged urge to purge has been fused with anger over vaccinations and mask mandates and the assault on teaching any American history that doesn’t fit a suitably patriotic mold. In such states as Florida, Texas, and Virginia, the backlash has grown intense and been wrapped in the pretense of giving parents “control” over their children’s education. The bullseye has moved from Robin Hood, The Communist Manifesto, and The Catcher in the Rye to a new set of targets. Many of the books now under fire deal with race, slavery, gender issues, and of course, sexuality.

Raising the fever pitch are books exploring gay relationships and gender identity. In November 2021, a Virginia school board member was quoted in press reports as saying, “I think we should throw those books in a fire.”In February, a Tennessee pastor went further, leading a book burning that saw Harry Potter and Twilight consigned to the flames—both among the usual suspects in recent book bans and challenges.

We’ve seen these flames before. In fiction, they raged in Ray Bradbury’s dystopic Fahrenheit 451 in which “firemen” burn outlawed books. But they have also roared more frighteningly in fact. Book burnings are actually older than books, dating to ancient times in Greece and China. After Gutenberg’s printing revolution, the Vatican created the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, a catalog of banned books, some of which were burned, sometimes along with their authors—like Giordano Bruno in 1600.

Most notoriously in pre-World War II Germany, some 25,000 “un-German” books were consigned to Nazi bonfires in May 1933. Targeted by Hitler’s loyal disciples were works by German Jews and Marx, Freud, and Einstein. Books by German novelists Thomas Mann and Eric Maria Remarque—author of the World War I classic All Quiet on the Western Front— went into the flames along with such American writers as Ernest Hemingway, Jack London, and Helen Keller.

Book Burning May 10, 1933 Image courtesy US Holocaust Memorial Museum https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/conten...

Can it happen here? It has.

Nearly a century before the Nazi book burnings, a concerted effort to flood the slaveholding states with abolitionist literature was met with fire. In the summer of 1835, an angry mob raided a Charleston, South Carolina post office and consigned thousands of abolitionist pamphlets to a bonfire. The book burning was topped off with an effigy of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison being set ablaze. Garrison was lucky. Tragically, abolitionist publisher Elijah Lovejoy was not. Two years later, a mob intent on burning anti-slavery literature in Alton, Illinois murdered Lovejoy as he tried to defend his presses. A century later, in 1939, California growers burned Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Grapes of Wrath.

Scrubbing the nation’s public square of “offensive” materials and torching books—despite the protections in the Bill of Rights—are as American as apple pie, lynch mobs, burning crosses, and now, tiki torches.

But there’s something new in the equation. The latest wave of book suppression is not simply about “subversion” or “dirty words.” Scratch the surface of recent book bans and it is clear that the assault on free expression cannot be separated from the larger Orwellian effort to sanitize American history, delegitimize literature by gay writers and people of color, and undermine democracy.

This revitalized onslaught carries the distinct whiff of white, Christian nationalism. This is the racial, cultural, and political ideology that once reared its head as nineteenth-century Nativism, the reinvigorated Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s, and the America Firsters of the 1930s.

Claiming that the United States is a “Christian nation,” this strand of anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic American DNA is older than the nation itself. Time has not diminished its power. Now adding “globalists” to their enemies list, white Christian nationalism has been tied to the Charlottesville rioters who chanted “You will not replace us” and the January 6 insurrection by experts who study the movement.

America has no monopoly on this historically powerful faction. A form of white Christian nationalism, with its claims of racial superiority, certainly fed Hitler’s rise in Germany.

And that is why this revived wave of book suppression is a piece of a much larger development. The reason that Maus, a Pulitzer-Prize winning graphic novel-memoir about the Holocaust, was ostensibly pulled from schools in Tennessee was for some of its language and a discreet cartoon illustration of the author’s mother—an Auschwitz survivor—naked in the bathtub where she had committed suicide. But its critics apparently sought a kinder, gentler discussion of the Holocaust, although any attempts to soften that history tiptoe dangerously toward denialism. This is how history goes down 1984’s “Memory Hole.”

It is more than a little ironic that this onslaught of suppression comes as many on the Right decry the so-called “cancel culture” of the Left. Claiming their right to free speech is under attack, modern-day “book burners” crush that freedom under their boot heels as they attempt to distort or erase history and silence unwelcome voices. When such voices and ideas are deemed a threat and suppressed by the government, religious authorities, or a political party, we teeter on the thin ice of authoritarianism. The ice cracks when a fictional character is attacked—whether it is Homer Simpson, Huckleberry Finn, or Robin Hood. All three have come under fire over the years.

Banning books, legislating against “divisive concepts” in history class, and purging diversity all come straight from the playbook of the Strongman. He knows the power of the pen. Books make us think. Literature cultivates the free mind. Writers are truth-tellers. Authoritarians know the danger posed by truth. And they are more than willing to use sword and flame to cut it down.

The question is what can we do about it?

“The antidote to authoritarianism is not some form of American authoritarianism,” Cooper Union librarian David K. Berninghausen told the Times in 1952. “The antidote is free inquiry.”

When Robin Hood was threatened by a textbook commissioner in 1953, some Indiana State University students fought back. Five of them gathered chicken feathers, dyed them green, and spread them across campus. Their protest caught on at other colleges, including UCLA, where two hundred students dressed up as Sherwood Forest’s Merry Men for a Green Feather drop. A clever, well-aimed protest, the Green Feather movement broke no windows or legs. Robin Hood was spared.

But those more innocent days are gone. In the internet age, the lines are more sharply drawn, sides set in stone, and the stakes much higher.

That is why dumping some green feathers or wearing an “I READ BANNED BOOKS” t-shirt will not be enough for this moment. If we care, we must take to heart Ike’s advice and “read every book.” We must firmly resolve to read. But buying and reading Maus or Toni Morrison’s Beloved are only the first steps.

We have to make sure that others can read these books. We must be audacious in support of free libraries and vigorously support all teachers who want to encourage students to read, debate, and think for themselves. And we must vigilantly push back on politicians and schoolboards purging libraries of uncomfortable truths. A few loud voices dominating a schoolboard or town hall meeting do not a majority make. To allow a noisy minority to dictate what we read and teach is skating on that thin ice of totalitarian loyalty oaths typical of a Mussolini or Stalin.

On this final note, history is clear. When you have succeeded in marking a writer as “degenerate” or “immoral”—as the Nazis did—you have moved towards dehumanizing them. It is a few short perilous steps from censorship to suppression to a conflagration far worse. In Berlin, on the spot where Nazis threw books into a bonfire, there is a plaque citing German playwright Heinrich Heine’s 1820 words, which read in part: “Where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people as well.”

The road to Hell is lit by burning books.

© Copyright 2022 Kenneth C. Davis All rights reserved

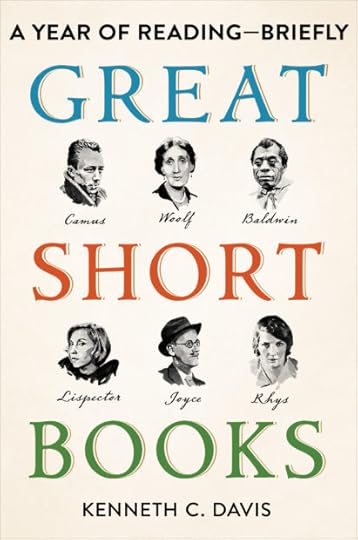

GREAT SHORT BOOKS: A Year of Reading–Briefly

COMING FROM SCRIBNER BOOKS

NOVEMBER 22, 2022

GREAT SHORT BOOKS:

A YEAR OF READING — BRIEFLY

During the lock-down, I swapped doom-scrolling for the insight and inspiration that come from reading great fiction. Inspired by Boccaccio’s “The Decameron” and its brief tales told during a pandemic, I read 58 great short novels –not as an escape but an antidote.

“A short novel is like a great first date. It can be extremely pleasant, even exciting, and memorable. Ideally, you leave wanting more. It can lead to greater possibilities. But there is no long-term commitment.”

–From “Notes of a Common Reader,” the Introduction to Great Short Books

The result is a compendium that goes from “Candide” to Colson Whitehead, and Edith Wharton to Leila Slimani. And yes, Maus and other Banned Books.

From hard-boiled fiction to magical realism, the 18th century to the present day, Great Short Books spans genres, cultures, countries, and time to present a diverse selection of acclaimed and canonical novels—plus a few bestsellers.

Like browsing in your favorite bookstore, this eclectic compendium is a fun and practical book for any passionate reader hoping to broaden their collection—or anyone who is looking for an entertaining, effortless reentry into reading.

I can’t wait to start talking about this book with readers everywhere.

Available for pre-order from Scribner/Simon & Schuster

March 26, 2022

“A lover’s quarrel with the world”-Robert Frost

(Updated March 26, 2022; Originally published August 2009; video edited and created by Colin Davis. One correction: I no longer have a home in Vermont mentioned in the video, but have not lost my admiration for Robert Frost.)

America’s Poet, Robert Frost, was born on March 26, 1874 –not in New England where so many of his greatest poems are set but in San Francisco.

The first poet invited to speak at a Presidential inaugural, Frost told the new President:

Be more Irish than Harvard. Poetry and power is the formula for another Augustan Age. Don’t be afraid of power.

–“Poetry and Power,” Poets.org

Apples, birches, hayfields and stone walls; simple features like these make up the landscape of four-time Pulitzer Prize winner Robert Frost’s poetry. Known as a poet of New England, Frost (1874-1963) spent much of his life working and wandering the woods and farmland of Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire.

As a young man, he dropped out of Dartmouth and then Harvard, then drifted from job to job: teacher, newspaper editor, cobbler. His poetry career took off during a three-year trip to England with his wife Elinor where Ezra Pound aided the young poet. Frost’s language is plain and straightforward, his lines inspired by the laconic speech of his Yankee neighbors.

But while poems like “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” are accessible enough to make Frost a grammar-school favorite, his poetry is contemplative and sometimes dark—concerned with themes like growing old and facing death. One brilliant example is this poem about a young boy sawing wood, Out, out–

The buzz-saw snarled and rattled in the yard

And made dust and dropped stove-length sticks of wood,

A brief biography of Robert Frost can be found at Poets.org, where there are more samples of his poetry. It includes an account of Frost and JFK.

Frost died on January 29, 1963, in Boston. After his death, an unsigned editorial in the The New York Times, entitled “Ending in Wisdom,” noted:

Robert Frost was more than America’s best-known poet. He was a national figure, almost an institution, a man who went up and down the land saying his poems wherever, it sometimes seemed, two or three Americans were gathered together. He spoke in the language of the common man.

New York Times, January 31, 1963

Robert Frost (Courtesy Library of Congress)

One of my favorite places in Vermont is the Frost grave-site in the cemetery of the First Church in Old Bennington -just down the street from the Bennington Monument, where this video was recorded.

I had a lover’s quarrel with the world

–Robert Frost’s epitaph

March 24, 2022

Don’t Know Much About® the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire on March 25, 1911 from front page of The New York World (Source: [Post revised from original on 3/25/2011]Cornell University ILR School Kheel Center © 2011)

[Reposted from original on 3/25/2011]Can anything positive or hopeful emerge from a terrible tragedy? That is a question we are all pondering as a pandemic sweeps the United States and the world.

We are also asking about the human costs of “business as usual.”

So it is a moment to consider of one of the greatest tragedies of modern American history.

On March 25, 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York caught fire and 146 people died, most of them women between the ages of 16 and 23, many were Jewish and Italian immigrants. They had been trapped inside the building, its doors chained shut.

“Look for the union label.”

If you are of a certain generation, you may recognize those words instantly. They are the first line of a song that became a 1970s advertising icon.

Sung by a swelling chorus of lovely ladies (and a few men) of all colors, shapes and sizes, it was the anthem of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union.

Airing as American unions began to confront the long, steady drain of jobs to cheaper foreign labor markets, the song implored us to look for the union label when shopping for clothes (“When you are buying a coat, dress or blouse”).

Seeing these earnest women, thinking of them at their sewing machines, made us race to the closet and check our clothes for that ILGWU tag. (“It says we’re able to make it in the USA.”)

The International Ladies Garment Worker Union was born in 1900, in the midst of the often-violent period of early 20th century labor organizing when brutal working conditions and child labor were the norm in America’s mines and factories.

One of the companies the union attempted to organize was the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory at what is now Greene Street and Washington Place in New York’s Greenwich Village.

A walkout against the firm in 1909 helped strengthen the union’s rolls and led to a union victory in 1910. But the Triangle Shirtwaist Company –which would chain its doors shut to control its workers— earned infamy when a fire broke out on March 25, 1911 and 146 workers were trapped in the flaming building and died. Some jumped to their deaths.

A police officer and others with the broken bodies of Triangle fire victims at their feet, look up in shock at workers poised to jump from the upper floors of the burning Asch Building. (Credit: Cornell University ILR School Kheel Center ©2011)

The two owners of the factory were indicted but found not guilty. The tragedy helped galvanize the trade union movement and especially the ILGWU.

On this anniversary of that dreadful event, it is worth remembering that American prosperity was built on the sweat, tears and blood of working men and women. Immigration and jobs are the issue again today, just as they were more than a century ago.

Cornell University’s Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation offers a web exhibit on the Triangle Factory Fire. The Library of Congress also offers numerous resources on the tragedy.

On February 28, 2011, American Experience on PBS aired a documentary film about the tragedy and the period.

The site is part of New York University and a National Historic Landmark.

March 16, 2022

Don’t Know Much About® Mr. Madison

March 16 marks the anniversary of the birth in 1751 of America’s fourth President, James Madison, also known as “The Father of the Constitution.”

Like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, his Virginia predecessors in the presidency, Madison embodied the “Great Contradiction”– that a nation “conceived in liberty” was also born in shackles.

READ MY ARTICLE “THE AMERICAN CONTRADICTION,” on teaching the history of American slavery in Social Education.

Small in stature and overshadowed by the more famous Washington and Jefferson, Madison is counted among of the greatest of the Founding Fathers for the breadth and influence of his contributions. Like many of the Founders, Madison had reservations about slavery as a contradiction to this ideals, but did little to end the institution. He hoped that slavery would end after the foreign trade was abolished and thought that enslaved African-Americans should be emancipated and returned to Africa.

The story of Paul Jennings, who was enslaved by Madison and wrote a memoir of working as a servant in the White House, is told in my book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.

Montpelier, home of James Madison (Photo: Kenneth C. Davis, 2010)

James Madison was born on March 16, 1751 in Port Conway, Virginia. The son of a tobacco planter and somewhat sickly as a child, he went north to study at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton). There he came under the influence of the college President, John Witherspoon, a future signer of the Declaration of Independence, and made a friend of fellow student, Aaron Burr, son of the College’s founder.

Returning to Virginia, Madison became involved in patriot politics and became a close colleague of his neighbor Thomas Jefferson, serving as Jefferson’s adviser and confidant during the war years while Jefferson was Governor of Virginia.

In 1794, he married the widow Dolley Payne Todd, having been formally introduced by his college friend Aaron Burr.

A few Madison Highlights:

•Secured passage of the Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom (1786), an act that is a cornerstone of religious freedom in America. As part of that effort, he wrote the influential Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments. (I discuss the “Remonstrance” in my article “America’s True History of Religious Tolerance” in the October 2010 Smithsonian.)

•Was the moving force behind the Constitutional Convention and was one of the principal authors of the Constitution. Madison’s support of the electoral system is laid out in this essay by Yale professor Akhil Reed Amar “The Troubling Reason the Electoral College Exists.”

•With Alexander Hamilton and John Jay was one of the authors of The Federalist Papers (Resources from the Library of Congress), arguments in favor of the ratification of the Constitution

•Was principal author of the Bill of Rights, which he originally thought unnecessary

Following ratification of the Constitution, Madison was a member of the House of Representatives from Virginia and a powerful Congressional ally of George Washington.

•Drafted the first version of Washington’s Farewell Address

•Supervised the Louisiana Purchase as Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of State

•Presided over the ill-prepared nation during the War of 1812, the “second war of independence”

I believe there are more instances of the abridgment of the freedom of the people by gradual and silent encroachments of those in power than by violent and sudden usurpations. –June 16, 1788

Madison’s grave at Montpelier (Author photo 2010)

Madison died on June 28, 1836 at Montpelier, at age 85. Enslaved servant Paul Jennings was at his bedside and later recalled in a memoir that Madison died, “as quietly as the snuff of a candle goes out.”

James Madison is buried at Montpelier.

LINKS:

The Library of Congress Resource Collection on James Madison.

Madison’s Major Papers and Inaugural Addresses can be found at the Avalon Project of the Yale Law School.

March 14, 2022

Don’t Know Much About® Eli Whitney (A TED-Ed “Lesson Worth Sharing”)

“Eli Whitney,” portrait of the inventor, oil on canvas, by the American painter Samuel F. B. Morse. 35 7/8 in. x 27 3/4 in. Courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

On March 14, 1794, Eli Whitney received a patent for the machine known as the Cotton Gin. Here is a short video about the Connecticut-born inventor’s most famous “invention,” the Cotton Gin. This was created as my first contribution to Ted-Ed: “Lessons Worth Sharing.”

This portrait of the inventor is by another inventor– Samuel F.B. Morse who was a well-known painter and art teacher before he gained fame for the development of the telegraph and the Morse Code.

The cotton gin changed history for good and bad. By allowing one field hand to do the work of 10, it powered a new industry that brought wealth and power to the American South — but, tragically, it also multiplied and prolonged the use of slave labor. In this video, I discuss innovation, while warning of unintended consequences.

Eli Whitney died in New Haven, Connecticut on January 8, 1825. You can learn more about Whitney and his inventions at the Eli Whitney Museum and Workshop.