Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 26

October 19, 2021

Who Said It? (10/18/2021)

George Washington, in a letter to William Morris (April 12, 1786)

In this letter, written nearly five years after the surrender of the British at Yorktown in October 1781, Washington wrote to William Morris, his friend and wealthy financier of the Revolution, about the problems caused by an Abolition society in the city of Philadelphia.

Washington objected to the society attempting to free the enslaved people brought to the city. He expressed his belief that there should be a plan to abolish slavery, but that taking “property” –meaning enslaved people– from their owners was “oppression.”

“I hope it will not be conceived from these observations, that it is my wish to hold the unhappy people who are the subject of this letter, in slavery. I can only say that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it—but there is only one proper and effectual mode by which it can be accomplished, & that is by Legislative authority: and this, as far as my suffrage will go, shall never be wanting.

But when slaves who are happy & content to remain with their present masters, are tampered with & seduced to leave them; when masters are taken at unawar[e]s by these practices; when a conduct of this sort begets discontent on one side and resentment on the other, & when it happens to fall on a man whose purse will not measure with that of the Society, & he looses his property for want of means to defend it—it is oppression in the latter case, & not humanity in any; because it introduces more evils than it can cure.”

Source: National Archives, “Founders Online”

For more on Washington at Yorktown, read my post “What did Washington get when the British surrendered at Yorktown?

October 18, 2021

Pop quiz: What did Washington get when the British surrendered at Yorktown?

(Original post updated 10/18/2021)

Answer: All of the enslaved people in Yorktown who had escaped to the British in hopes of freedom.

Surrender of Lord Cornwallis by John Trumbull (Source: Architect of the U.S. Capitol)

When the British forces under Cornwallis surrendered to George Washington and his French allies on October 19, 1781, the terms of capitulation included the following phrase

It is understood that any property obviously belonging to the inhabitants of these States, in the possession of the garrison, shall be subject to be reclaimed.

(Article IV, Articles of Capitulation; dated October 18, 1781. Source and Complete Text: Avalon Project-Yale Law School)

That “property” clearly meant the thousands of escaped enslaved people who had flocked to the British army during Cornwallis’s campaign in Virginia in what has been called the “largest slave rebellion in American history.”

They had come in the belief that the British would free them. Cornwallis had put them to work on the British defense works around the small tobacco port, and when disease started to spread and supplies ran low, Cornwallis forced hundreds of these people out of Yorktown. Many more died from epidemic diseases and the shelling of American and French artillery during the siege.

Nearly five years later, in April 1786, Washington wrote to financier Robert Morris regarding the problems for enslavers caused by Abolitionists in Philadelphia:

“I hope it will not be conceived from these observations, that it is my wish to hold the unhappy people who are the subject of this letter, in slavery. I can only say that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it—but there is only one proper and effectual mode by which it can be accomplished, & that is by Legislative authority: and this, as far as my suffrage will go, shall never be wanting.

But when slaves who are happy & content to remain with their present masters, are tampered with & seduced to leave them; when masters are taken at unawar[e]s by these practices; when a conduct of this sort begets discontent on one side and resentment on the other, & when it happens to fall on a man whose purse will not measure with that of the Society, & he looses his property for want of means to defend it—it is oppression in the latter case, & not humanity in any; because it introduces more evils than it can cure.”

Source: National Archives “Founders Online”

The African Americans in Yorktown included at least seventeen people who had left Washington’s Mount Vernon plantation with the British, as well as members of Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved community also captured earlier in 1781. They were all returned to bondage, along with thousands of others as Virginian slaveholders came to Yorktown to recover their “property.”

Isaac Granger Jefferson at about age 70 (Courtesy: Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

Among them was Isaac Granger Jefferson, a five-year-old boy who was returned to Monticello and later told his story.

The stories of some of the people “reclaimed” by Washington are told in my book, IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives.

The Battle of Yorktown and role of African-American soldiers there –as well as the fate of the enslaved people in the besieged town — are featured in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah.

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

“A fascinating exploration of war and the myths of war. Kenneth C. Davis shows how interesting the truth can be.” –Evan Thomas, New York Times-bestselling author of Sea of Thunder and John Paul Jones

October 9, 2021

Pop Quiz: Who first used the words “Wall of Separation” in talking about church and state?

Answer: Roger Williams, the dissident minister banished by the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony on October 9, 1635. Williams was told to leave the colony within six weeks. If he returned, he risked execution. He eventually went on to found Rhode Island, with a written constitution guaranteeing freedom of religion, approved by Parliament in 1644.

Williams died in Rhode Island in 1683. Learn more at the Roger Williams National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service).

As Williams biographer John M. Barry wrote:

Williams described the true church as a magnificent garden, unsullied and pure, resonant of Eden. The world he described as “the Wilderness,” a word with personal resonance for him. Then he used for the first time a phrase he would use again, a phrase that although not commonly attributed to him has echoed through American history. “[W]hen they have opened a gap in the hedge or wall of Separation between the Garden of the Church and the Wildernes of the world,” he warned, “God hathe ever broke down the wall it selfe, removed the Candlestick, &c. and made his Garden a Wildernesse.”

Read more: “God, Government and Roger Williams’ Big Idea” by John M. Barry in Smithsonian magazine

The phrase, “wall of separation between church and state” does not appear in the United States Constitution as many people think. But it was used in a famous letter written by Thomas Jefferson in 1802.

As I wrote in a 2011 essay, “Why U.S. is Not a Christian Nation,”

The idea was not Jefferson’s. Other 17th- and 18th-century Enlightenment writers had used a variant of it. Earlier still, religious dissident Roger Williams had written in a 1644 letter of a “hedge or wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world.”

Williams, who founded Rhode Island with a colonial charter that included religious freedom, knew intolerance firsthand. He and other religious dissenters, including Anne Hutchinson, had been banished from neighboring Massachusetts, the “shining city on a hill” where Catholics, Quakers and Baptists were banned under penalty of death.

According to the Library of Congress:

This phrase has become well known because it is considered to explain (many would say, distort) the “religion clause” of the First Amendment to the Constitution: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion …,” a clause whose meaning has been the subject of passionate dispute for the past 50 years.

Read more about Jefferson’s letter and the phrase: “A Wall of Separation” by James Hutson, a curator at the Library of Congress.

And read more about traditions of tolerance in my article in Smithsonian, “America’s True History of Religious Tolerance.”

October 1, 2021

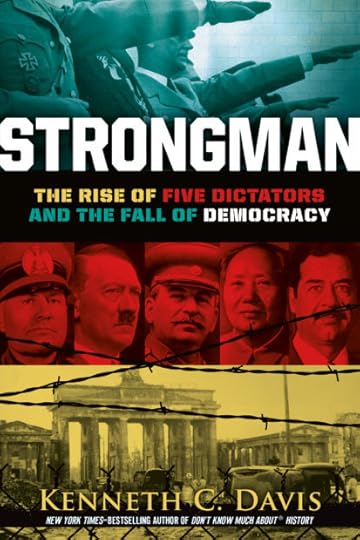

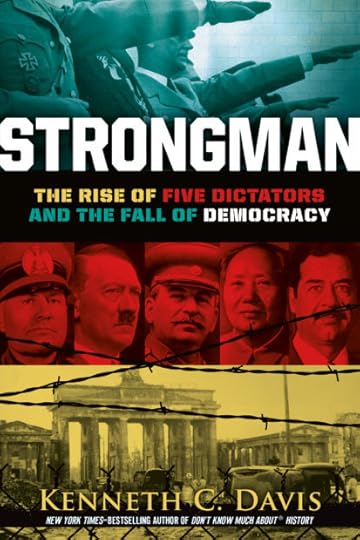

STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy

Mao Proclaims the People’s Republic of China (Wiki Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...)

On October 1, 1949 Mao Zedong, chief architect of the Chinese Communist Revolution, proclaimed the People’s Republic of China. Mao was responsible for the deaths of tens of millions while transforming China into a world power. His story is told in Strongman. STRONGMAN has been named one of the “Best Children’s Books of the Year-2021” by the Bank Street College of Education.STRONGMAN tells the real stories of the lives and times of five of the most deadly dictators of the 20th century — Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Saddam Hussein.Order the hardcover and e-book from Holt Books

STRONGMAN has been named one of the “Best Children’s Books of the Year-2021” by the Bank Street College of Education.STRONGMAN tells the real stories of the lives and times of five of the most deadly dictators of the 20th century — Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Saddam Hussein.Order the hardcover and e-book from Holt Books An audiobook is available from Penguin Random House

Strongman named among Washington Post Best Books of 2020Named to “Best Young Adult Books of the Year” by Kirkus ReviewsNamed to “Best YA Books of 2020 for Understanding the US Today” Kirkus ReviewsStarred review from Kirkus Reviews: “History’s warnings reverberate in this gripping read about five dictatorial strongmen. A pitch-perfect balance of nuanced reflection and dire warning.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Publishers Weekly: “A fascinating, highly readable portrayal of infamous men that provides urgent lessons for democracy now.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Shelf Awareness: “Kenneth C. Davis…conveys his plentiful knowledge of dictators in this powerful, spine-tingling biographic work that covers five of the world’s most horrifying autocrats. Grounded in thorough research, Strongman expertly explores the fragility of democracy …” Read the full review here•2021 YALSA Nonfiction Award nominee

A review in Booklist says, “Davis does not sugarcoat his material, inviting long thoughts with his assertion that this is a decidedly human story that points to real people as evidence that evil exists in this troubled world.”

In addition to telling how these men took unlimited power, brought one-party rule to their nations, and were responsible for the deaths of millions of people, the book offers a brief history of Democracy and discusses the present threat to democratic institutions around the world.

In a time when Democracy is under assault across the globe, it is more important than ever to understand how a Strongman takes power and how quickly democracy can vanish –even as millions cheer its death.

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR STRONGMAN

“I found myself engrossed in it from beginning to end. I could not help admiring Davis’s ability to explain complex ideas in readable prose that never once discounted the intelligence of young readers. It is very much a book for our time.”

—Sam Wineburg, Margaret Jacks Professor of Education & History, Stanford University, author of Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone).

“Strongman is a book that is both deeply researched and deeply felt, both an alarming warning and a galvanizing call to action, both daunting and necessary to read and discuss.”

—Cynthia Levinson, author of Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws That Affect Us Today

“A wake-up call to democracies like ours: we are not immune to despots . . . Strongman demonstrates that democracy is not permanent, unless it is collectively upheld. This book shakes that immortality narrative.”

—Jessica Ellison, President of the Minnesota Council for the Social Studies; Teacher Education Specialist, Minnesota Historical Society

Rarely does a history book take such an unflinching look at our common future, where the very presence of democracy is less than certain; even rarer is a history book in which the author’s moral convictions incite young readers to civic engagement; rarest of all, a history book as urgent, as impassioned, and as timely as Kenneth C. Davis’ Strongman.

—Eugene Yelchin, author of the Newbery Honor book Breaking Stalin’s Nose.

Don’t Know Much About® Halloween–The Hidden History

(Video directed and produced by Colin Davis; originally posted October 2015)

When I was a kid in the early 1960s, the autumn social calendar was highlighted by the Halloween party in our church. In these simpler day, the kids all bobbed for apples and paraded through a spooky “haunted house” in homemade costumes –Daniel Boone replete with coonskin caps for the boys; tiaras and fairy princess wands for the girls. It was safe, secure and innocent.

The irony is that our church was a Congregational church — founded by the Puritans of New England. The same people who brought you the Salem Witch Trials.

Here’s a link to a history of those Witch Trials in 1692.

Rooted in pagan traditions more than 2000 years old, Halloween grew out of a Celtic Druid celebration that marked summer’s end. Called Samhain (pronounced sow-in or sow-een), it combined the Celts’ harvest and New Year festivals, held in late October and early November by people in what is now Ireland, Great Britain and elsewhere in Europe. This ancient Druid rite was tied to the seasonal cycles of life and death — as the last crops were harvested, the final apples picked and livestock brought in for winter stables or slaughter. Contrary to what some modern critics believe, Samhain was not the name of a malevolent Celtic deity but meant, “end of summer.”

The Celts also saw Samhain as a fearful time, when the barrier between the worlds of living and dead broke, and spirits walked the earth, causing mischief. Going door to door, children collected wood for a sacred bonfire that provided light against the growing darkness, and villagers gathered to burn crops in honor of their agricultural gods. During this fiery festival, the Celts wore masks, often made of animal heads and skins, hoping to frighten off wandering spirits. As the celebration ended, families carried home embers from the communal fire to re-light their hearth fires.

Getting the picture? Costumes, “trick or treat” and Jack-o-lanterns all got started more than two thousand years ago at an Irish bonfire.

Christianity took a dim view of these “heathen” rites. Attempting to replace the Druid festival of the dead with a church-approved holiday, the seventh-century Pope Boniface IV designated November 1 as All Saints’ Day to honor saints and martyrs. Then in 1000 AD, the church made November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to remember the departed and pray for their souls. Together, the three celebrations –All Saints’ Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls Day– were called Hallowmas, and the night before came to be called All-hallows Evening, eventually shortened to “Halloween.”

And when millions of Irish and other Europeans emigrated to America, they carried along their traditions. The age-old practice of carrying home embers in a hollowed-out turnip still burns strong. In an Irish folk tale, a man named Stingy Jack once escaped the devil with one of these turnip lanterns. When the Irish came to America, Jack’s turnip was exchanged for the more easily carved pumpkin and Stingy Jack’s name lives on in “Jack-o-lantern.”

Halloween, in other words, is deeply rooted in myths –ancient stories that explain the seasons and the mysteries of life and death.

Columbus Day-The World Is a Pear

(Video edited and produced by Colin Davis; originally posted October 2011.)

Add me to the list. I think it is well past time that we ditched Columbus Day.

I found it (the world) was not round . . . but pear shaped, round where it has a nipple, for there it is taller, or as if one had a round ball and, on one side, it should be like a woman’s breast, and this nipple part is the highest and closest to Heaven.

–Christopher Columbus, Log of his third voyage (1498)

“In fourteen hundred and ninety-two/Columbus sailed the ocean blue.”

We all remember that much. But after that basic date, things get a little fuzzy. Here’s what they didn’t tell you–

*Most educated people knew that the world was not flat.

*Columbus never set foot in what would become America.

*Christopher Columbus made four voyages to the so-called New World. And his discoveries opened an astonishing era of exploration and exploitation. But his arrival marked the beginning of the end for tens of millions of Native Americans spread across two continents.

* On his third voyage, he wrote that the world was not round but pear-shaped, like a woman’s breast. They did not tell us that in Geography class.

In 1892, the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Columbus inspired the composition of the original Pledge of Allegiance and a proclamation by President Benjamin Harrison describing Columbus as “the pioneer of progress and enlightenment.” (Source: Library of Congress, “American Memory: Today in History: October 12”)

That was the patriotic American can-do spirit behind the Columbian Exposition—also known as the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893.

In 1934, the “progress and enlightenment” celebrated in the Columbus narrative was powerful enough to merit a federal holiday on October 12 – a reflection of the growing political clout of the Knights of Columbus, a Roman Catholic fraternal organization that fought discrimination against recently arrived immigrants, many of them Italian and Irish.

Once a hero. Now a villain. Cities and states around the country are changing the name of the holiday to “Indigenous People’s Day” or “Native American Day” to move this holiday away from a man whose treatment of the natives he encountered included barbaric punishments and forced labor.

“Indigenous Peoples’ Day recognizes that Native people are the first inhabitants of the Americas, including the lands that later became the United States of America. And it urges Americans to rethink history.”

–National Museum if the American Indian

Here are more resources on “Indigenous People’s Day” from the Teaching Tolerance organization

September 16, 2021

Constitution Day Pop Quiz: Who was the first man to sign the Constitution?

[Originally posted September 17, 2017]

Answer: On September 17, Washington signed the parchment copy first, as President of the convention.

On September 17, 1787, 39 delegates to the Constitutional Convention meeting in Philadelphia, voted to adopt the United States Constitution.

United States Constitution (Image Courtesy of the National Archives)

To recap these events:

Working from May 25, when a quorum was established, until September 17, 1787, when the convention voted to endorse the final form of the Constitution, the delegates gathered in Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania State House were actually obligated only to revise or amend the Articles of Confederation. Under those Articles, however, the government was plagued by weaknesses, such as its inability to raise revenues to pay its foreign debts or maintain an army. From the outset, most the convention’s organizers, James Madison chief among them, knew that splints and bandages wouldn’t do the trick for the broken Articles.

The government was broke –literally and figuratively– and they were going to fix it by inventing an entirely new one. James Madison had been studying more than 200 books on constitutions and republican history sent to him by Thomas Jefferson in preparation for the convention. The moving force behind the convention, Madison came prepared with the outline of a new Constitution.

A reluctant George Washington, whose name was placed at the head of list of Virginia’s delegates without his knowledge, was unquestionably spurred by recent events in Massachusetts (Shay’s Rebellion, a violent protest by Massachusetts farmers). Elected president of the convention, he wrote from Philadelphia in June to his close wartime confidant and ally, the Marquis de Lafayette:

I could not resist the call to a convention of the States which is to determine whether we are to have a government of respectability under which life, liberty, and property will be secured to us, or are to submit to one which may be the result of chance or the moment, springing perhaps from anarchy and Confusion, and dictated perhaps by some aspiring demagogue.

On September 17, Washington signed the parchment copy first, as President of the convention. He was followed by the remaining delegates from the twelve states that sent delegates in geographical order, from north to south, beginning with New Hampshire. (Rhode Island was the only state that did not send a delegation.) When the last of the signatures was added –that of Abraham Baldwin of Georgia– Benjamin Franklin gazed at Washington’s chair, on which was painted a bright yellow sun. He then spoke, as James Madison recorded it:

I have, said he, often in the course of a session, and the vicissitudes of my hopes and fears as to its issue, looked at that behind the President without being able to tell if it was rising or setting: But now at length I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting sun.

In another perhaps more apocryphal tale, Franklin left the building and was confronted by a lady who asked, “Well Doctor, do we have a monarchy or a republic?” The witty sage of Philadelphia replied,

“A republic, madam, if you can keep it.”

This post is excerpted from America’s Hidden History, which offers fuller account of the Convention and the events that led to it. You can also read more about the Constitutional Convention and the Constitution in Don’t Know Much About History: Anniversary Edition, Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents and In the Shadow of Liberty.

For more about the Constitution, visit these sites:

The National Constitutional Center in Philadelphia and James Madison’s Montpelier

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion paperback-April 15, 2014)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

New York Times Bestseller

America’s Hidden History

September 6, 2021

Don’t Know Much About the “First Pilgrims”

[Entry originally posted on September 20, 2015]

September 8, 1565 is traditionally noted as the date that the Spanish arrived and settled St. Augustine, identified as the first permanent European settlement in the future United States. But what were they doing there?

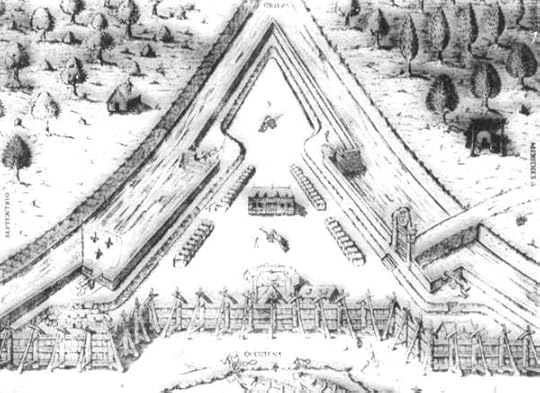

They had come to eliminate a French Protestant settlement called Fort Caroline. That is a piece of America’s Hidden History.

Old etching of Fort Caroline, from the Florida State Archives.

On September 20, 1565, America’s first Pilgrims were wiped out in a dawn raid –a religious bloodbath — in what was then Spanish Florida. Leaving their base at the newly established St. Augustine, Spanish troops led by Admiral Menéndez assaulted the small French colony of Fort Caroline –near present-day Jacksonville,

Attacking before dawn on September 20, 1565 with the frenzy of holy warriors, the Spanish easily overwhelmed Fort Caroline. With information provided by a French turncoat, the battle-tested Spanish soldiers used ladders to quickly mount the fort’s wooden walls. Inside the settlement, the sleeping Frenchmen—most of them farmers or laborers rather than soldiers—were caught off-guard, convinced that no attack could possibly come in the midst of such a terrible storm. But they had fatally miscalculated. The veteran Spanish harquebusiers swept in on the nightshirted and naked Frenchmen who leapt from their beds and grabbed futilely for weapons. Their attempts to mount any real defense were hopeless. The battle lasted less than an hour.

Although some of the French defenders managed to escape the carnage, 132 soldiers and civilians were killed in the fighting in the small fort. The Spanish suffered no losses and only a single man was wounded. The forty or so French survivors fortunate enough to reach the safety of some boats anchored nearby, watched helplessly as Spanish soldiers flicked the eyeballs of the French dead with the points of their daggers.

Excerpt from America’s Hidden History

[Admiral] Menéndez had many of the survivors strung up under a sign that read, “I do this not as to Frenchmen but as to heretics.” A few weeks later, he ordered the execution of more than 300 French shipwreck survivors at a site just south of St. Augustine, now marked by an inconspicuous national monument called Fort Matanzas, from the Spanish word for “slaughters.”

Fort Matanzas Courtesy National Park Service

A brief account of this story is told in this New York Times Op-Ed, “A French Connection.”

The full story is recounted in “Isabella’s Pigs,” the first chapter of America’s Hidden History. An excerpt from this book, “America’s First True ‘Pilgrims,'” was published in Smithsonian magazine (May 2008).

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

September 1, 2021

STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy

STRONGMAN tells the real stories of the lives and times of five of the most deadly dictators of the 20th century — Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Saddam Hussein.Order the hardcover and e-book from Holt Books

STRONGMAN tells the real stories of the lives and times of five of the most deadly dictators of the 20th century — Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Saddam Hussein.Order the hardcover and e-book from Holt Books An audiobook is available from Penguin Random House

Strongman named among Washington Post Best Books of 2020Named to “Best Young Adult Books of the Year” by Kirkus ReviewsNamed to “Best YA Books of 2020 for Understanding the US Today” Kirkus ReviewsStarred review from Kirkus Reviews: “History’s warnings reverberate in this gripping read about five dictatorial strongmen. A pitch-perfect balance of nuanced reflection and dire warning.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Publishers Weekly: “A fascinating, highly readable portrayal of infamous men that provides urgent lessons for democracy now.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Shelf Awareness: “Kenneth C. Davis…conveys his plentiful knowledge of dictators in this powerful, spine-tingling biographic work that covers five of the world’s most horrifying autocrats. Grounded in thorough research, Strongman expertly explores the fragility of democracy …” Read the full review here•2021 YALSA Nonfiction Award nominee

A review in Booklist says, “Davis does not sugarcoat his material, inviting long thoughts with his assertion that this is a decidedly human story that points to real people as evidence that evil exists in this troubled world.”

In addition to telling how these men took unlimited power, brought one-party rule to their nations, and were responsible for the deaths of millions of people, the book offers a brief history of Democracy and discusses the present threat to democratic institutions around the world.

In a time when Democracy is under assault across the globe, it is more important than ever to understand how a Strongman takes power and how quickly democracy can vanish –even as millions cheer its death.

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR STRONGMAN

“I found myself engrossed in it from beginning to end. I could not help admiring Davis’s ability to explain complex ideas in readable prose that never once discounted the intelligence of young readers. It is very much a book for our time.”

—Sam Wineburg, Margaret Jacks Professor of Education & History, Stanford University, author of Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone).

“Strongman is a book that is both deeply researched and deeply felt, both an alarming warning and a galvanizing call to action, both daunting and necessary to read and discuss.”

—Cynthia Levinson, author of Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws That Affect Us Today

“A wake-up call to democracies like ours: we are not immune to despots . . . Strongman demonstrates that democracy is not permanent, unless it is collectively upheld. This book shakes that immortality narrative.”

—Jessica Ellison, President of the Minnesota Council for the Social Studies; Teacher Education Specialist, Minnesota Historical Society

Rarely does a history book take such an unflinching look at our common future, where the very presence of democracy is less than certain; even rarer is a history book in which the author’s moral convictions incite young readers to civic engagement; rarest of all, a history book as urgent, as impassioned, and as timely as Kenneth C. Davis’ Strongman.

—Eugene Yelchin, author of the Newbery Honor book Breaking Stalin’s Nose.

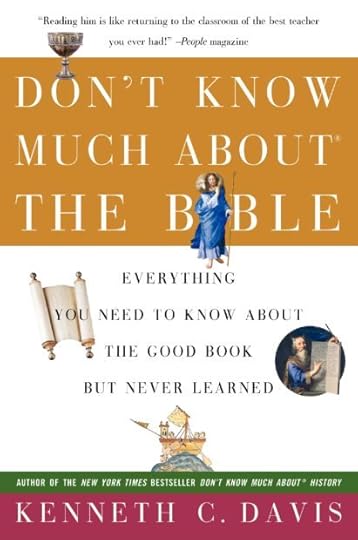

Don’t Know Much About® the Bible

The Devil can scripture for his own purpose.

–Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice

Throughout history, the Bible has been used to justify many arguments. Often those biblical citations are mistaken, taken out of context, based on a mistranslation –or simply misused. These myths and misconceptions about what is in the Bible led me to write Don’t Know Much About® the Bible.

In American history, the Bible was cited to both justify slavery and call for its abolition. For centuries, slavers pointed to a passage in the book of Genesis to justify the cruel, murderous enslavement of millions of Africans. It is a part of the story of Noah that is not usually told in Sunday school.

After building the ark, loading the animals two by two, and weathering the Flood, Noah and his family reach dry land. Noah begins to plant and grows some grapes to make wine:

20 And Noah began to be an husbandman, and he planted a vineyard:

21 And he drank of the wine, and was drunken; and he was uncovered within his tent.

22 And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without.

23 And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward, and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces were backward, and they saw not their father’s nakedness.

24 And Noah awoke from his wine, and knew what his younger son had done unto him.

25 And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren.

26 And he said, Blessed be the Lord God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant.

27 God shall enlarge Japheth, and he shall dwell in the tents of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant.

–Genesis 9:20-27 King James Version

The passage is a bit garbled. But the “curse of Ham” was used to justify the enslavement of people of African ancestry, who were believed to be descendants of Ham, through his son Canaan. This theory was widely held during the eighteenth to twentieth centuries to justify both slavery and the racist notion of the inferiority of Blacks, and added to the many biblical references used by Christians to justify enslavement.

Gradually, other Christians argued that to enslave another human was a basic contradiction of Jesus’s teachings, including the Christian version of the “Golden Rule”:

Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them: for this is the law and the prophets.

–Matthew 7: 12 (King James Version)

There are many other instances of the Bible and religion being used as a weapon throughout American history, including the anti-Catholic “Bible Riots” in Philadelphia in 1844, which I wrote about in A Nation Rising.

Read more about the traditions of religious intolerance in my Smithsonian article “America’s True History of Religious Tolerance.”