Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 24

March 11, 2022

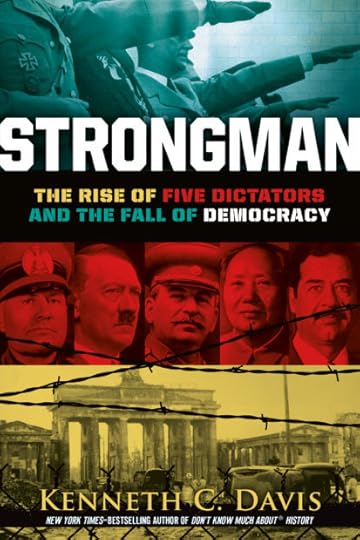

STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy

Cheering crowds greet the Nazis in Vienna. (Wikimedia Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anschlu... German Federal Archive

STRONGMAN has been named one of the “Best Children’s Books of the Year-2021” by the Bank Street College of Education.STRONGMAN tells the real stories of the lives and times of five of the most deadly dictators of the 20th century — Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Saddam Hussein.Order the hardcover and e-book from Holt Books

STRONGMAN has been named one of the “Best Children’s Books of the Year-2021” by the Bank Street College of Education.STRONGMAN tells the real stories of the lives and times of five of the most deadly dictators of the 20th century — Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Saddam Hussein.Order the hardcover and e-book from Holt Books An audiobook is available from Penguin Random House

Strongman named among Washington Post Best Books of 2020Named to “Best Young Adult Books of the Year” by Kirkus ReviewsNamed to “Best YA Books of 2020 for Understanding the US Today” Kirkus ReviewsStarred review from Kirkus Reviews: “History’s warnings reverberate in this gripping read about five dictatorial strongmen. A pitch-perfect balance of nuanced reflection and dire warning.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Publishers Weekly: “A fascinating, highly readable portrayal of infamous men that provides urgent lessons for democracy now.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Shelf Awareness: “Kenneth C. Davis…conveys his plentiful knowledge of dictators in this powerful, spine-tingling biographic work that covers five of the world’s most horrifying autocrats. Grounded in thorough research, Strongman expertly explores the fragility of democracy …” Read the full review here•2021 YALSA Nonfiction Award nominee

A review in Booklist says, “Davis does not sugarcoat his material, inviting long thoughts with his assertion that this is a decidedly human story that points to real people as evidence that evil exists in this troubled world.”

In addition to telling how these men took unlimited power, brought one-party rule to their nations, and were responsible for the deaths of millions of people, the book offers a brief history of Democracy and discusses the present threat to democratic institutions around the world.

In a time when Democracy is under assault across the globe, it is more important than ever to understand how a Strongman takes power and how quickly democracy can vanish –even as millions cheer its death.

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR STRONGMAN

“I found myself engrossed in it from beginning to end. I could not help admiring Davis’s ability to explain complex ideas in readable prose that never once discounted the intelligence of young readers. It is very much a book for our time.”

—Sam Wineburg, Margaret Jacks Professor of Education & History, Stanford University, author of Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone).

“Strongman is a book that is both deeply researched and deeply felt, both an alarming warning and a galvanizing call to action, both daunting and necessary to read and discuss.”

—Cynthia Levinson, author of Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws That Affect Us Today

“A wake-up call to democracies like ours: we are not immune to despots . . . Strongman demonstrates that democracy is not permanent, unless it is collectively upheld. This book shakes that immortality narrative.”

—Jessica Ellison, President of the Minnesota Council for the Social Studies; Teacher Education Specialist, Minnesota Historical Society

Rarely does a history book take such an unflinching look at our common future, where the very presence of democracy is less than certain; even rarer is a history book in which the author’s moral convictions incite young readers to civic engagement; rarest of all, a history book as urgent, as impassioned, and as timely as Kenneth C. Davis’ Strongman.

—Eugene Yelchin, author of the Newbery Honor book Breaking Stalin’s Nose.

March 2, 2022

Remembering the Nuremberg Trials: A Don’t Know Much About® Audiominute

(Originally posted January 26, 2021; latest revision 3/2/2022)

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine continues and the question of war crimes is in the air, it is instructive to look back at the most famous war crimes in history, the Nuremberg Trials of Nazis in the aftermath of the defeat of Nazi Germany. The U.S. delegation was led by Robert H. Jackson

For over a month, during the summer of 1945, representatives of the Soviet, French, U.S. and U.K. governments attempted to reconcile their conflicting legal concepts and devise a workable procedure for the trial. At the core of these intense negotiations was Robert H. Jackson. Jackson refused to back down on certain legal principles, most importantly, the position that aggressive warfare was an international crime.

‘Our view, is that this isn’t merely a case of showing that these Nazi Hitlerite people failed to be gentlemen in war; it is a matter of their having designed an illegal attack on the international peace.’ ”

The Nuremberg Trials — A Don’t Know Much About® Audiominute

On November 20, 1945, in the aftermath of World War II, the first trials of Nazi war criminals began. This military tribunal, the Nuremberg Trials, as they came to be known, was convened by the four victorious Allies—Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

Listen to this audiominute.

https://dontknowmuch.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/New-Recording-9.m4a

Defendants in the Dock at the Nuremberg Trials (Image: National Archives)

“That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of the law is one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason.

What makes this inquest significant is that these prisoners represent sinister influences that will lurk in the world long after their bodies have returned to dust. We will show them to be living symbols of racial hatreds, of terrorism and violence, and of the arrogance and cruelty of power.”

-United States Prosecutor Robert Jackson, Opening Statement (11/21/1945)

Read Robert Jackson’s full opening statement here

This is a timeline of the Nuremberg Trials from the Robert H. Jackson Center.

On November 29, 1945, Day 8 of the Nuremberg Trials, a documentary film of the liberated concentration camps taken by American military photographers was shown. (Graphic images).

These resources on the Nuremberg Trials are from the Library of Congress.

This is an article about the Nuremberg Trials I wrote in 2005 for the Rutland (VT) Herald.

February 27, 2022

STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy

February 27, 1933

The Burning of the Reichstag (Image: National Archives)

STRONGMAN has been named one of the “Best Children’s Books of the Year-2021” by the Bank Street College of Education.STRONGMAN tells the real stories of the lives and times of five of the most deadly dictators of the 20th century — Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Saddam Hussein.Order the hardcover and e-book from Holt Books

STRONGMAN has been named one of the “Best Children’s Books of the Year-2021” by the Bank Street College of Education.STRONGMAN tells the real stories of the lives and times of five of the most deadly dictators of the 20th century — Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Saddam Hussein.Order the hardcover and e-book from Holt Books An audiobook is available from Penguin Random House

Strongman named among Washington Post Best Books of 2020Named to “Best Young Adult Books of the Year” by Kirkus ReviewsNamed to “Best YA Books of 2020 for Understanding the US Today” Kirkus ReviewsStarred review from Kirkus Reviews: “History’s warnings reverberate in this gripping read about five dictatorial strongmen. A pitch-perfect balance of nuanced reflection and dire warning.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Publishers Weekly: “A fascinating, highly readable portrayal of infamous men that provides urgent lessons for democracy now.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Shelf Awareness: “Kenneth C. Davis…conveys his plentiful knowledge of dictators in this powerful, spine-tingling biographic work that covers five of the world’s most horrifying autocrats. Grounded in thorough research, Strongman expertly explores the fragility of democracy …” Read the full review here•2021 YALSA Nonfiction Award nominee

A review in Booklist says, “Davis does not sugarcoat his material, inviting long thoughts with his assertion that this is a decidedly human story that points to real people as evidence that evil exists in this troubled world.”

In addition to telling how these men took unlimited power, brought one-party rule to their nations, and were responsible for the deaths of millions of people, the book offers a brief history of Democracy and discusses the present threat to democratic institutions around the world.

In a time when Democracy is under assault across the globe, it is more important than ever to understand how a Strongman takes power and how quickly democracy can vanish –even as millions cheer its death.

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR STRONGMAN

“I found myself engrossed in it from beginning to end. I could not help admiring Davis’s ability to explain complex ideas in readable prose that never once discounted the intelligence of young readers. It is very much a book for our time.”

—Sam Wineburg, Margaret Jacks Professor of Education & History, Stanford University, author of Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone).

“Strongman is a book that is both deeply researched and deeply felt, both an alarming warning and a galvanizing call to action, both daunting and necessary to read and discuss.”

—Cynthia Levinson, author of Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws That Affect Us Today

“A wake-up call to democracies like ours: we are not immune to despots . . . Strongman demonstrates that democracy is not permanent, unless it is collectively upheld. This book shakes that immortality narrative.”

—Jessica Ellison, President of the Minnesota Council for the Social Studies; Teacher Education Specialist, Minnesota Historical Society

Rarely does a history book take such an unflinching look at our common future, where the very presence of democracy is less than certain; even rarer is a history book in which the author’s moral convictions incite young readers to civic engagement; rarest of all, a history book as urgent, as impassioned, and as timely as Kenneth C. Davis’ Strongman.

—Eugene Yelchin, author of the Newbery Honor book Breaking Stalin’s Nose.

February 19, 2022

Don’t Know Much About® Executive Order 9066

(Post revised 2/19/2022)

Eighty years ago, on this date- February 19, 1942 – a different kind of infamy

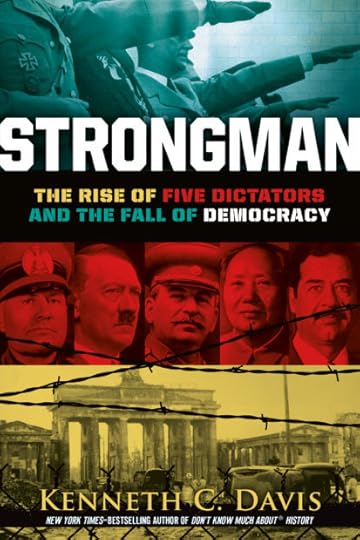

“The Masuda family, owners of the Wanto Grocery in Oakland, California, proclaimed that they were American, even as they were forced to sell their business before they were incarcerated in August 1942.” National Museum of American History. Photo by Dorothea Lange (Source: National Archives)

Franklin D. Roosevelt famously told Americans when he was inaugurated in 1933:

The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.

But on February 19, 1942 –a little more than two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor— President Roosevelt allowed America’s fear to provoke him into an action regarded among his worst mistakes. He issued Executive Order 9066.

It declared certain areas to be “exclusion zones” from which the military could remove anyone for security reasons. It provided the legal groundwork for the eventual relocation of approximately 120,000 people to a variety of detention centers —“internment camps” — around the country, the largest forced relocation in American history. Nearly two-thirds of them were American citizens.

The attitude of many Americans at the time was expressed in a Los Angeles Times editorial of the period:

“A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched… So, a Japanese American born of Japanese parents, nurtured upon Japanese traditions, living in a transplanted Japanese atmosphere… notwithstanding his nominal brand of accidental citizenship almost inevitably and with the rarest exceptions grows up to be a Japanese, and not an American…” (Source: Impounded, p. 53)

On March 23, 1942, the United States government began taking away the liberty of more than one hundred thousand people–the Japanese Americans viewed as a threat after Pearl Harbor. On that date, the U.S. Army began removing people of Japanese descent from Los Angeles. (Smaller numbers of Americans of German and Italian descent were also detained.)

See this exhibit on Internment from the National Museum of American History.

Some of the most famous photographs of the period were taken by Dorothea Lange. Read this piece from the National Archives. The FDR Library and Museum offers resources on teaching Executive Order 9066 and photographer Ansel Adams also documented the period.

Roy Takano [i.e., Takeno] at town hall meeting, Manzanar Relocation Center, California Photo by Ansel Adams Source: Library of Congress

The National Constitution Center offers an excellent overview of the order and its impact.February 17, 2022

What Do We Do About George?

Portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart (Source: Clark Institute Williamstown, Mass.)

[Originally posted July 2, 2020; revised February 17, 2022]

It is George Washington’s Birthday (not President’s Day). Seeing as the holiday falls in February –Black History Month– it is a good time to bring these two crucial pieces of history together.

Like many of the Founders, the Father of Our Country enslaved people. Inheriting ten people from his father at age eleven, Washington held more than three hundred men, women, and children in bondage at the time of his death in 1799. While one man was freed in Washington’s will, the others had to wait for Martha Washington to die. And roughly half of those people remained enslaved, parceled out among the Custis family, as part of the estate of Martha’s first husband.

In other words, George Washington was an enslaver from childhood to grave. And we have the receipts.

He once raffled off whole families in lots, including small children separated from parents. He later purchased four children at an estate sale, sending two dark-skinned boys to do fieldwork while two “mulatto” boys became house servants. Frank Lee became Mount Vernon’s butler and his brother Billy Lee served as Washington’s valet, his “loyal manservant,” for some thirty years.

The last remaining set of Washington’s dentures (Courtesy: Mount Vernon Ladies Association)

Washington’s own journal records that he purchased teeth pulled from the mouths of enslaved people, presumably to be fitted into his dentures. In exchange for a grocery list of rum, molasses, fruits, and sweetmeats, he once shipped off a man named Tom, a repeat runaway, and at least two other men to the cane fields of the West Indies.

And then there is the heroic Washington’s actions at Yorktown. After his signal victory over the British in 1781, General Washington wasted no time in recovering Esther, Lucy, Sambo Andersen, and fourteen others who had escaped Mount Vernon when offered the chance. They were among thousands of enslaved people who had fled to the British in hopes of emancipation. While Washington won America’s liberty, they lost theirs.

Did this inconsistency trouble Washington? The contradiction between his devotion to freedom while enslaving people did seem to prick his conscience. In 1786, he confided to fellow Founder Robert Morris, “there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it [slavery].”

But he did precious little to make it happen, either while presiding over the convention that cemented slavery in the Constitution, or as first president. After Philadelphia became the nation’s capital in 1790, President Washington shuttled enslaved servants in and out of the city to evade a Pennsylvania law that called for the emancipation of enslaved males residing in the state for more than six months. In 1793, he signed the Fugitive Slave Act, making assistance to runaways a federal offense.

When Ona Judge, Martha Washington’s enslaved maid, learned she would be given away as a wedding gift, she escaped from the home of the president in 1796. He advertised a ten-dollar reward for her return and spent the next three years trying to track down and recover a woman who had risked all for freedom.

For more than two centuries, these contradictions were given little weight by Washington’s admirers. The little boy who couldn’t tell a lie was immortalized as “First in the hearts of his countrymen.” The enslavement of human beings, especially by one of America’s most admired presidents, remained the dirty secret long concealed by textbooks and popular culture.

But a stunning moment of correction has arrived. It begs the questions:

Will George Washington’s picture be removed from the currency?

Will protestors project the images of African-American heroes onto Washington’s stern visage carved on Mt. Rushmore, as Harriet Tubman’s face now adorns Robert E. Lee’s statue in Richmond?

Washington Monument (Courtesy National Parks Service https://www.nps.gov/wamo/learn/histor...)

What about the Washington Monument?

We are now in a teachable moment. What we do is limited only by our creativity and the courage to be honest. We won’t take a chisel to the Washington Monument or spray paint it with graffiti. But draping the pristine obelisk with a “Black Lives Matter” banner in a moment of national reflection? That would let students and all Americans know that Washington was a flawed man who committed a crime against humanity while also building the nation. This was the “gross injustice and cruelty” that Frederick Douglass famously called out in his 1852 speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

Remaining silent on that injustice and cruelty is no longer an option. Because this is one of those “self-evident” truths. The United States was “conceived in liberty,” but born in shackles. We can no longer honor Washington’s indispensable achievements without recognizing his original sin.

What better occasion than Washington’s Birthday to do that.

February 12, 2022

It is NOT Presidents Day. Or President’s Day. Or Even Presidents’ Day.

(Earlier post updated 2/17/2022)

So What Day Is it After All?

Okay. We all do it. It’s printed on calendars and posted in bank windows. We mistakenly call the third Monday in February Presidents Day, in part because of all those commercials in which George Washington swings his legendary ax and “Rail-splitter” Abe Lincoln hoists his ax to chop down prices on everything from mattresses and linens to SUVs.

But, this February holiday is officially still George Washington’s Birthday.

I wrote My Project About Presidents in 3rd Grade when I was 9. Even then I was asking questions about history and presidents

But Washington’s Birthday has become widely known as Presidents Day (or President’s Day, or Presidents’ Day). The popular usage and confusion resulted from the merging of what had been two widely celebrated Presidential birthdays in February —Lincoln’s on February 12th, which was never a federal holiday– and Washington’s on February 22, which was.

Created under the Uniform Holiday Act of 1968, which gave us three-day weekend Monday holidays, the federal holiday on the third Monday in February is technically still Washington’s Birthday. But here’s the rub: the holiday can never land on Washington’s true birthday because the latest date it can fall is February 21, as it did in 2011.

There is a wealth of information about the First President at his home Mount Vernon.

Washington’s Tomb — Mt. Vernon (Photo credit Kenneth C. Davis 2010)

Read More About the creation of the Presidency, Washington, his life and administration in DON’T KNOW MUCH ABOUT® THE AMERICAN PRESIDENTS. Washington’s role in the American Revolution is highlighted Chapter One of THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR.

And George Washington’s role as an enslaver is fully explored in my book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives.

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion paperback-April 15, 2014)

January 29, 2022

Whatever Became of Thomas Paine?

[Originally posted December 2020; revised 1/29/2022]

Thomas Paine was born in England on January 29, 1736 (in the Old Style; his birth-date is also listed as February 9, 1737 in the New Style).

“These are the times that try men’s souls…. Tyranny, like hell is not easily conquered.”

–Thomas Paine, The American Crisis (December 19, 1776)

Thomas Paine ©National Portrait Gallery London copy by Auguste Millière, after an engraving by William Sharp, after George Romney oil on canvas, circa 1876

Of more worth is one honest man to society and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.

-Thomas Paine Common Sense

Text via Thomas Paine National Historical Association

Thomas Paine’s essay Common Sense is widely credited with helping to rouse Americans to the patriot cause. Its sales were extraordinary at the time; given today’s American population, current day sales would reach some 60 million copies.

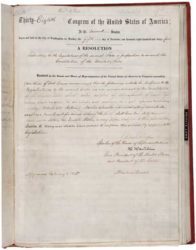

Common sense; addressed to the inhabitants of America, on the following interesting subjects (Library of Congress)

The pamphleteering Paine is best known for Common Sense, which appeared in January 1776 and The Crisis — first published on December 19 1776 — among other works that supported the cause of independence. But after the Revolution, Paine returned to his native England and later went to France, then in the throes of its Revolution.

Paine was caught up in the complex politics of the bloody Revolution there, eventually winding up in a French prison cell, facing the prospect of the guillotine. After eventually being freed, Paine wrote an open letter in 1796 angrily denouncing President George Washington for failing to do enough to secure his release.

“Monopolies of every kind marked your administration almost in the moment of its commencement. The lands obtained by the Revolution were lavished upon partisans; the interest of the disbanded soldier was sold to the speculator…In what fraudulent light must Mr. Washington’s character appear in the world, when his declarations and his conduct are compared together!”

Source: George Washington’s Mount Vernon

This was a serious case of bridge-burning and Paine swiftly fell from grace in America. But apart from dissing the Father of the Country, Paine had also fallen from favor for his most famous work after Common Sense. In 1794, he had published The Age of Reason (Part I), a deist assault on organized religion and the errors of the Bible.

In it, Paine had written:

I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.

All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit.

(Source: USHistory.org)

After returning to the United States, which owed so much to him, Paine was regarded as an atheist and was abandoned by most of his friends and former allies. He died in disgrace, an outcast from the United States he had helped create. The Quaker church he had rejected refused to bury him after he died in Greenwich Village (New York City) in 1809. He was buried on his farm in New Rochelle, New York. A handful of people attended his funeral.

An admirer brought his remains back to England for reburial there, but they were lost.

Today he is honored in New York City by a small park named in his honor.

“This park in the heart of New York City’s civic center is named for patriot, author, humanitarian, and political visionary Thomas Paine (1737-1809). The land that is now Thomas Paine Park was once part of a freshwater swamp surrounded, ironically, by three former British prisons for revolutionaries.

His most famous work, Rights of Man (1791), was written after the French Revolution and proposes that government is responsible for protecting the natural rights of its people. Many of Paine’s ideas were strikingly far sighted. He advocated for the abolition of slavery, defended freedom of thought and expression, and proposed an association of nations to avert the spread of conflicts.”

You can read more about Thomas Paine, his relationship with Washington and his ultimate fate in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents.

“A lover’s quarrel with the world”-Robert Frost

(Updated January 29, 2022; Originally published August 2009; video edited and created by Colin Davis. One correction: I no longer have a home in Vermont mentioned in the video, but have not lost my admiration for Robert Frost.)

America’s Poet, Robert Frost, died on January 29, 1963, in Boston. After his death, an unsigned editorial in the The New York Times, entitled “Ending in Wisdom,” noted:

Robert Frost was more than America’s best-known poet. He was a national figure, almost an institution, a man who went up and down the land saying his poems wherever, it sometimes seemed, two or three Americans were gathered together. He spoke in the language of the common man.

New York Times, January 31, 1963

Robert Frost (Courtesy Library of Congress)

This is a brief video tribute to Robert Frost.

I had a lover’s quarrel with the world

–Robert Frost’s epitaph

One of my favorite places in Vermont is the Frost grave-site in the cemetery of the First Church in Old Bennington -just down the street from the Bennington Monument. This video was recorded there.

Apples, birches, hayfields and stone walls; simple features like these make up the landscape of four-time Pulitzer Prize winner Robert Frost’s poetry. Known as a poet of New England, Frost (1874-1963) spent much of his life working and wandering the woods and farmland of Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire. As a young man, he dropped out of Dartmouth and then Harvard, then drifted from job to job: teacher, newspaper editor, cobbler. His poetry career took off during a three-year trip to England with his wife Elinor where Ezra Pound aided the young poet. Frost’s language is plain and straightforward, his lines inspired by the laconic speech of his Yankee neighbors.

But while poems like “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” are accessible enough to make Frost a grammar-school favorite, his poetry is contemplative and sometimes dark—concerned with themes like growing old and facing death. One brilliant example is this poem about a young boy sawing wood, Out, out–

The buzz-saw snarled and rattled in the yard

And made dust and dropped stove-length sticks of wood,

The first poet invited to speak at a Presidential inaugural, Frost told the new President:

Be more Irish than Harvard. Poetry and power is the formula for another Augustan Age. Don’t be afraid of power.

–“Poetry and Power,” Poets.org

A brief biography of Robert Frost can be found at Poets.org, where there are more samples of his poetry. It includes an account of Frost and JFK.

Robert Frost died on January 29, 1963. He had written his own epitaph, “I had a lover’s quarrel with the world,” etched on his headstone in a church cemetery in Bennington, VT.

January 24, 2022

Don’t Know Much About® Edith Wharton

(Originally posted on 1/24/2013; revised 1/24/2021)

Photo courtesy The Mount https://www.edithwharton.org/discover...

You may have been assigned to read Ethan Frome in high school. Or you have read or seen the grand dramas of New York Society, House of Mirth or The Age of Innocence. That’s how you know the name Edith Wharton.

[image error]

A plaque honoring Edith Wharton in Paris (Photo: Courtesy of Radio France International)

Born in New York City, January 24, 1862: Edith Newbold Jones, who achieved fame as Edith Wharton, the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1921 (for The Age of Innocence).

But the other lesser-known aspect of Wharton’s life is her experience in France during World War I, where she founded hospitals and refugee centers for women and children.

Romance, scandal and ruin among New York socialites—long before this was the stuff of People, and “Gossip Girl,” it was the subject matter for Edith Wharton’s most famous works. In such novels as The House of Mirth (1905) and The Age of Innocence (1920), Wharton painted detailed, acid portraits of high society life. In doing so, she created heartbreaking conflicts beneath the façade of wealth and manners. Again and again, characters like Newland Archer and Lily Bart were forced to choose between conforming to social expectations and pursuing true love and happiness. Her most famous work set outside the realm of high-tone New York was Ethan Frome (1911), set in wintry, rural Massachusetts.

Edith Wharton in France during World War I (Photo: Courtesy The Mount Edith Wharton’s Home)

Wharton had spent years in Europe as a child and teenager. But she moved to France in 1910 while war in Europe was on the horizon and her marriage to socialite Teddy Wharton deteriorated.

Once the war broke out, she also wrote urging the United States to join the war. Then she saw the hardship caused as the fighting that tore across Europe starting in August 1914 created masses of refugees.

American novelist Edith Wharton set up workshops for women all over Paris, making clothes for hospitals as well as lingerie for a fashionable clientele. She raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for refugees and tuberculosis sufferers and ran a rescue committee for the children of Flanders, whose towns were bombarded by the Germans. Her friend and fellow author Henry James called her the “great generalissima”.

Source: Radio France International: “Edith Wharton-The American novelist who joined France’s WWI effort”

She started in her neighborhood with sewing workshops that eventually employed more than 800 women, opened hostels for tuberculosis patients and refugee children, hosted benefit concerts, sent dispatches from the war front.

–Elaine Sciolino, “Edith Wharton’s Paris,” New York Times

In the first year of her work, her Children of Flanders Rescue Committee could record:

Refugees assisted: 9,229

Meals served: 235,000

Refugees for whom employment has been found: 3,400

Garments distributed: 48,333

For her wartime work, in 1916 Wharton was awarded France’s highest decoration – a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur.

Edith Wharton died in Paris in 1937 and is buried in Versailles. Here is her New York Times obituary.

The Mount is Wharton’s restored home in the Berkshires in Massachusetts.

January 10, 2022

Don’t Know Much About® “Common Sense”

(Originally posted 1/10/2012; revised 1/10/2022)

Society in every state is a blessing, but Government, even in its best state, is but a necessary evil; in its worst state, an intolerable one.

–Thomas Paine, January 10, 1776

Image Library of Congress Thomas Paine (1737–1809). Common Sense. Philadelphia: R. Bell, 1776. American Imprint Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (003.00.00) //www.loc.gov/exhibits/books-that-shape...

You know that saying about the pen being mightier than the sword? As the American Revolution haltingly began, an anonymous writer helped prove it true.

The battles at Lexington and Concord in 1775, the easy victory at Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775, and the devastating casualties inflicted on the British army by the rebels at Bunker (Breed’s) Hill in June 1775 had all given hope to the patriot cause a full year before independence was declared.

But the final break—Independence—still seemed too extreme to some. It’s important to remember that the vast majority of Americans at the time were first and second generation. Their family ties and their sense of culture and national identity were essentially English. Many Americans had friends and family in England. And the commercial ties between the two were obviously also powerful.

The forces pushing toward independence needed momentum, and they got it in several ways. The first factor was another round of heavy-handed British miscalculations. First, the king issued a proclamation cutting off the colonies from trade. Then, unable to conscript sufficient troops, the British command decided to supplement its regulars with mercenaries, soldiers from the German principalities sold into King George’s service by their princes. Most came from Hesse-Cassel, so the name Hessian became generic for all of these hired soldiers.

The Hessians accounted for as much as a third of the English forces fighting in the colonies. Their reputation as fierce fighters was linked to a frightening image—reinforced, no doubt, by the British command—as plundering rapists. (Ironically, many of them stayed on in America. Benjamin Franklin gave George Washington printed promises of free land to lure mercenaries away from English ranks.) When word of the coming of 12,000 Hessian troops reached America, it was a shock, and further narrowed chances for reconciliation. In response, a convention in Virginia instructed its delegates to Congress to declare the United Colonies free and independent.

The second factor was a literary one. On January 10, 1776, an anonymous pamphlet entitled Common Sense came off the presses of a patriot printer. Its author, Thomas Paine, had simply, eloquently, and admittedly with some melodramatic prose, stated the reasons for independence. He reduced the hereditary succession of kings to an absurdity, slashed down all arguments for reconciliation with England, argued the economic benefits of independence, and even presented a cost analysis for creating an American navy.

With the assistance of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine had come to America from London and found work with a Philadelphia bookseller. In the colonies for only a few months, Paine wrote, at Franklin’s suggestion, a brief history of the upheaval against England.

Thomas Paine (National Portrait Gallery: NPG.2008.5)

It is almost impossible to exaggerate the impact and importance of Common Sense. Paine’s polemic was read by everyone in Congress, including General Washington, who commented on its effects on his men. Equally important, it was read by people everywhere. The pamphlet quickly sold 150,000 copies, going through numerous printings until it had reached half a million. (Approximating the American population at the time, including slaves, at 3 million, a current equivalent pamphlet would have to sell more than 35 million copies!) Paine donated the proceeds to Washington’s army.

For the first time, mass public opinion had swung toward the cause of independence.

Adapted from Don’t Know Much About History which discusses the Revolution and Thomas Paine’s unhappy fate. In Paris during the French Revolution, Paine was imprisoned by revolutionary authorities. Upon his eventual release, he wrote an angry open letter to his old comrade George Washington, in which he skewered Washington for not having done enough to secure his release from the French prison. Paine later returned to America but when he died in 1809, no church in American would accept his body for burial as he was an atheist. The man who influenced history Paine was buried with a handful of people in attendance at his farm in New Rochelle, New York. His remains were then removed to his native England for reburial but were later lost.