Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 21

June 20, 2022

“Lives, Fortunes, Sacred Honor:” Whatever Became Of 56 Signers? (1st in a series)

(Post updated 6/20/2022)

Now that Juneteenth has become a national holiday observed as the other “Independence Day,” it is time to look back on the first Independence Day –July 4th, 1776. As the nation is going through an examination of the role slavery played in American History, it is important to recognize its role to the Founders at Philadelphia.

You cannot teach American History without acknowledging the role slavery played. And talking about the men who signed the Declaration is one way to do that.

Read: “The American Contradiction: Conceived in Liberty, Born in Shackles” (Social Education, March/April 2020)

This is the first in a series of posts about the men who signed the Declaration of Independence and what became of them. Most of these men remain somewhat obscure. They have also been mythologized in some online forums. Many of them played a significant role in the early republic before, during, and after July 4, 1776.

(Read through all eleven posts in this website’s Blog Category)

Slavery existed in all thirteen of the future states and at least 40 of the 56 signers enslaved people or were involved in the slave trade. One focus of the series is to show which of these men enslaved people or otherwise participated in the slave trade. A “YES” after their listing means they enslaved people; a “NO” means they did not.

They pledged:

“... our Lives, our Fortunes, and our Sacred Honor.”

Then what happened?

The Grand Flag of the Union, the “first American flag,” originally raised in 1775 and later by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

Those strong words concluded the Declaration of Independence when it was adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776.

There is little question that men who signed that document were putting their lives at risk. The identity and fates of a handful of those Signers is well-known. Two future presidents — Adams and Jefferson— and America’s most famous man, Benjamin Franklin, were on the Committee that drafted the document.

But the names and fortunes of many of the other signers, including the most visible, John Hancock, are more obscure. In the days leading up to Independence Day, I will offer a thumbnail sketch of each of the Signers in alphabetical order. Some prospered and thrived; some did not: How many of those Signers actually paid with their Lives, Fortunes, and Sacred Honor?

–John Adams (Massachusetts) Aged 40 when he signed, he went on to become the first vice president and second president of the United States. By 1790, Adams was convinced that his place in the history to be written would be diminished.

“The history of our Revolution will be one continued lie from one end to the other,” he wrote fellow Founder Benjamin Rush in 1790.

“The essence of the whole will be that Dr. Franklin’s electrical rod smote the earth and out sprang General Washington. That Franklin electrified him with his rod –and thenceforward these two conducted all the policies,

Portrait of John Adams at age 88 by Jane Stuart, after Gilbert Stuart, 1824.(National Park Service)

negotiations, legislatures, and war.”

Adams died on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration in 1826 at age 90. (Jefferson died that same day) NO

The Adams house is a National Historical Park.

–Samuel Adams (Mass.) Older cousin to John, Samuel Adams was 53 at the signing. He went on to a career in state politics, initially refused to sign the Constitution because it lacked a Bill of Rights, and was governor of Massachusetts. He died in 1803 at 81. NO

–Josiah Bartlett (New Hampshire) Inspiring the name of the fictional president of West Wing fame on TV, Bartlett was a physician, aged 46 at the time of the signing. He helped ratify the Constitution in his home state, giving the document the necessary nine states to become the law of the land. Elected senator he chose to remain in New Hampshire as governor. Three of his sons and other descendants also became physicians. He died in 1795 at age 65. YES

–Carter Braxton (Virginia) A 39-year-old plantation owner, Braxton was looking to invest in the slave trade before the Revolution. Initially reluctant about independence, he helped fund the rebellion and lost a considerable fortune during the war — not because he was a signer, but because of shipping losses suffered during the war itself. He later served in the Virginia legislature and died in 1797 at age 61, far less wealthy than he had been, but also far from impoverished. YES

–Charles Carroll of Carrollton (Maryland) A plantation owner, 38 years old and one of America’s wealthiest men at the signing, Carroll was the only Roman Catholic signer and the last signer to die. With hundreds of enslaved people on his properties, Carroll considered freeing some of them before his death and later introduced a bill for gradual abolition in Maryland, which had no chance of passage. At age ninety-one, he laid the cornerstone of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad as a member of its board of directors. He died in 1832 at age 95. YES

Update: Carroll’s cousin was John Carroll, a Jesuit priest, first Roman Catholic bishop in the United States, and a founder of Georgetown College. The New York Times has reported how, in 1838, Georgetown sold 272 enslaved people to keep the college financially afloat.

GREAT SHORT BOOKS: A Year of Reading–Briefly

Bound galleys of Great Short Books have arrived!

COMING FROM SCRIBNER BOOKS

NOVEMBER 22, 2022

GREAT SHORT BOOKS:

A YEAR OF READING — BRIEFLY

Available for pre-order from Scribner/Simon & Schuster

During the lock-down, I swapped doom-scrolling for the insight and inspiration that come from reading great fiction. Inspired by Boccaccio’s “The Decameron” and its brief tales told during a pandemic, I read 58 great short novels –not as an escape but an antidote.

“A short novel is like a great first date. It can be extremely pleasant, even exciting, and memorable. Ideally, you leave wanting more. It can lead to greater possibilities. But there is no long-term commitment.”

–From “Notes of a Common Reader,” the Introduction to Great Short Books

The result is a compendium that goes from “Candide” to Colson Whitehead, and Edith Wharton to Leila Slimani. And yes, Maus and many other Banned Books and Writers.

Advance Praise for Great Short Books: A Year of Reading—Briefly

“GREAT SHORT BOOKS is a fascinating, thoughtful, and inspiring guide to a marvelous form of literature: the short novel. You can dip into this book anywhere you like, but I found myself reading it cover-to-cover, delighting in discovering new works while also revisiting many of my favorites. GREAT SHORT BOOKS is itself a great book—for those who are over-scheduled but want to expand their reading and for those who will simply delight in spending time with a passionate fellow reader who on every page reminds us why we need and love to read.”

–Will Schwalbe, New York Times bestselling author of THE END OF YOUR LIFE BOOK CLUB

“This is the book that you didn’t know you really needed. I began digging into this book as soon as I got it, and it was such a delight to read beautiful prose, just a sip at a time, with Kenneth Davis’ notes to give me context and help me more fully appreciate the stories. Keep this book near your bed or on your coffee table. It will be read and loved.”

–Celeste Headlee, journalist and author of WE NEED TO TALK and SPEAKING OF RACE

A Year of Reading–Briefly

From hard-boiled fiction to magical realism, the 18th century to the present day, Great Short Books spans genres, cultures, countries, and time to present a diverse selection of acclaimed and canonical novels—plus a few bestsellers.

Like browsing in your favorite bookstore, this eclectic compendium is a fun and practical book for any passionate reader hoping to broaden their collection—or anyone who is looking for an entertaining, effortless reentry into reading.

I can’t wait to start talking about this book with readers everywhere.

June 12, 2022

Don’t Know Much About the Lovings-50 Years Later

Richard and Mildred Loving at their home in Central Point, Va. with their children, Peggy (from left), Donald and Sidney, in 1967. Free Lance-Star, via Associated Press

[2022 repost of a 2017 revision of an earlier post]

When the the Supreme Court made its historic ruling in two cases in 2015 related to marriage equality (“Highlights from the Supreme Court Decisions on Same-Sex Marriage,” New York Times), the decision drew upon the case of Loving v. Virginia –decided by the Supreme Court on June 12, 1967 –50 years ago.

The case involved the law in Virginia, and other states, which prohibited interracial marriage, or “miscegenation.”

Loving v. Virginia changed that. And America.

“Today, one in six newlyweds in the United States has a spouse of a different race or ethnicity, according to a recent analysis of 2015 census data by the Pew Research Center. That is a five-fold increase from 1967, when just 3 percent of marriages crossed ethnic and racial lines.” (Source: New York Times)

Richard Loving, a white man, married Mildred, a 18-year-old woman of African-American and Native American descent, in Washington, D.C. When they returned to their native Virginia, they were arrested in the middle of the night and the Lovings were forced to leave Virginia. A few years later, young Mildred asked Robert F. Kennedy, the new Attorney General, for help. He suggested the American Civil Liberties Union and she wrote to them. Two young lawyers decided to take the case. They brought suit which eventually found its way to the Supreme Court

The Court ruled that anti-miscegenation laws, such as those in Virginia, violated the Due Process Clause (“No person shall be … deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law….” ) and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (“nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law …”).

In the unanimous majority opinion, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote:

“Marriage is one of the ‘basic civil rights of man,’ fundamental to our very existence and survival.”

Change in American history is often slow. And it usually comes from the bottom up –not the top down. Whether it was abolition, civil rights, or even independence itself, when it comes to most of the great social upheavals of our past, the politicians and “leaders” have generally had to be dragged kicking and screaming in the direction of change. It may be glacially slow, but it will happen, in part because there is a generational change that made same sex marriage prohibitions on the books seem as antiquated –and as wrong —as the now-unconstitutional bans on interracial marriage.

Before her death in 2008, Mildred Loving, the young woman who brought the suit against Virginia, issued a statement on the 40th anniversary of the decision. She wrote:

“Surrounded as I am now by wonderful children and grandchildren, not a day goes by that I don’t think of Richard and our love, our right to marry, and how much it meant to me to have that freedom to marry the person precious to me, even if others thought he was the ‘wrong kind of person’ for me to marry. I believe all Americans, no matter their race, no matter their sex, no matter their sexual orientation, should have that same freedom to marry. Government has no business imposing some people’s religious beliefs over others. I am still not a political person, but I am proud that Richard’s and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness, and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That’s what Loving, and loving, are all about.”

The January/February 2012 issue of Humanities magazine featured the Lovings as did a recent HBO documentary, The Loving Story.

There is a more complete discussion of the history of the Lovings, their case and its connection to the same sex marriage debate in the new, revised edition of Don’t Know Much About History: Anniversary Edition.

[image error]Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

June 8, 2022

Juneteenth: The “Other” Independence Day

(June 8, 2022: Revise of a post first published June 2015)

Monday June 20, 2022 will mark “Juneteenth National Independence Day.” On Thursday, June 17, 2021, President Biden signed a Juneteenth holiday into law.

How will you celebrate?

I have been writing and speaking about Juneteenth for many years. And I must admit when I discussed it back in 2011 and again in a New York Times oped in 2015, I honestly did not envision a day when this celebration of freedom would become a federal holiday. So for those still uncertain, here is the background.

Each year, JUNE 19 is a day to mark “Juneteenth” –a holiday celebrating emancipation at the end of the Civil War in 1865.

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free…” –General Gordon Granger, June 19, 1865

“SOME two months after Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, effectively ending the Civil War, Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger steamed into the port of Galveston, Tex. With 1,800 Union soldiers, including a contingent of United States Colored Troops, Granger was there to establish martial law over the westernmost state in the defeated Confederacy.

On June 19, two days after his arrival and 150 years ago today, Granger stood on the balcony of a building in downtown Galveston and read General Order No. 3 to the assembled crowd below. “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free,” he pronounced.”

Read more of the complete story of Juneteenth in my 2015 New York Times Op-ed, “Juneteenth is for Everyone”.

TO the emancipated people of Texas, the day would be celebrated as “Juneteenth,” a festive holiday marking liberation. It would become a widely shared day of picnics, barbecue, singing, and joy in the African-American community, gradually spreading across the former Confederacy and eventually moving north.

I believe that we have two histories in this country — one white, one black — and they have largely been separate and unequal. The story of Juneteenth is a perfect example of how one of these histories has largely been hidden when we teach American history.

Now more than ever, it is time to fix that.

The official Juneteenth Committee in East Woods Park, Austin, Texas on June 19, 1900. (Courtesy Austin History Center, Austin Public Library)

For centuries, slavery was the dark stain on America’s soul, the deep contradiction to the nation’s founding ideals of “Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” and “All men are created equal.”

When Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, he took a huge step toward erasing that stain. But the full force of his proclamation would not be realized until June 19, 1865—Juneteenth, as it was called by enslaved people in Texas freed that day.

“Juneteenth: Our Other Independence Day” My article in Smithsonian (June 15, 2011)

The question of how we teach and talk about enslavement is also the subject of my recent article in Social Education, the Journal of the National Council for the Social Studies. (NCSS). Read: The American Contradiction: Conceived in Liberty, Born in Shackles.

Foods on the Juneteenth altar include beets, strawberries, watermelon, yams and hibiscus tea, as well as a plate of black-eyed peas and cornbread. Credit Jim Wilson/The New York Times

The celebration of the holiday and its traditions of foods is highlighted in this New York Times article, “Hot Links and Red Drinks”

June 6, 2022

When Robin Hood Was Blacklisted

UPDATE: “Virginia Legal Action Threatens the Freedom to Read” (National Coalition Against Censorship)

“This legal action could profoundly limit the availability of books in the Commonwealth of Virginia. No book has been banned for obscenity in the United States in more than 50 years. Prohibiting the sale of books is a form of censorship that cannot be tolerated under the First Amendment.”

Robin Hood was a Commie.

That, at least, is what an Indiana state textbook commissioner thought back in 1953. This official called for schools to ban books mentioning Robin Hood for the simple reason that Robin and his Merry Men robbed from the rich and gave to the poor. Their antics reeked suspiciously of godless Socialism.

It is easy to laugh off this overlooked history as an amusing bit of trivia. Except the Hoosier state assault on Robin Hood was part of a larger nationwide effort to ban books and suppress intellectual freedom. It was led by Senator Joseph McCarthy during the anti-Communist “witch hunts.” It targeted books, writers, and libraries both at home and around the world. And it holds pointed lessons about safeguarding democracy from the forces threatening it today.

After the 1947 blacklisting of the “Hollywood Ten” screenwriters by the House Un-American Affairs Committee (HUAC), Senator McCarthy emerged as the face and unrelenting voice of a crusade against Communist influences in America. In 1950, McCarthy claimed to possess an extensive list of Communists who worked in the State Department. Launching his war on alleged Communist infiltrators as chairman of a Senate committee on government operations, McCarthy was abetted by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. To be labeled a Communist was an accusation from which there was no escape. Claims of innocence or invoking the Fifth Amendment were tantamount to confession.

Set against the Korean War begun in 1950, and with the convictions of Alger Hiss that year for perjury over espionage and the Rosenbergs in 1951 for atomic spying, America’s fear of Communism spread like wildfire. Gaining an army of rabid followers, McCarthy’s crusade to root out subversives widened to focus intently on libraries, which were pressured to purge their collections of works by Marx. By 1952, the New York Times described a pervasive wave of educational book censorship in America. Around the country, self-appointed local committees— “volunteer educational dictators” in the words of one librarian—were coercing librarians to remove books considered “un-American,” the Times found.

This anti-Communist juggernaut was not only steam-rolling domestic libraries. McCarthy sent it on a road trip. In April 1953, McCarthy’s underlings, attorney Roy Cohn and associate David Schine, were dispatched to Europe. Part of their mission was to scrutinize U.S. Information Service libraries, created to provide war-ravaged countries with American books. McCarthy claimed that these collections held thousands of works by Communists. Targeting suspect authors, just as Hollywood had been purged of “Red” screenwriters, Cohn and Schine succeeded in intimidating foreign service officials. No fires were set, but titles by Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, and Howard Fast, among others, were pulled from the shelves.

Inaugurated in January 1953, President Eisenhower was hesitant to challenge McCarthy. But he discreetly fired back. He told a Dartmouth commencement audience in June of that year:

“Don’t join the book burners. Don’t think you are going to conceal faults by concealing evidence that they ever existed. Don’t be afraid to go in your library and read every book, as long as that document does not offend our own ideas of decency.”

–President Eisenhower, “Remarks at the Dartmouth College Commencement”

Unfortunately, Eisenhower’s defense of reading was less than full-throated. Ultimately, his State Dept. folded to McCarthy’s men.

“Only reckless men, under these conditions, could choose to take steps offensive to McCarthy since the President and the Secretary [of State John Foster Dulles] have rarely backed up their subordinates whom McCarthy has singled out for attack.”

—The New Republic June 29, 1953

But America’s librarians were not about to be silenced. Despite the stale caricature of an old lady in a bun shushing the patrons, many librarians spoke out, daringly, given the nation’s fearful mood and threats to their jobs. Responding to this mounting pressure, the American Library Association (ALA), in concert with the American Association of Publishers, issued in June 1953 a “Freedom to Read” statement –since revised several times—that begins, “The freedom to read is essential to our democracy. It is continuously under attack.”

Unfortunately, the ALA was right then—and now. Ike’s “book burners” are back—or perhaps it is more accurate to say they never left. Across America, a concerted effort to purge school and public libraries of “offensive” literature has found new vigor and a louder voice. There is a long history of attempts to rid libraries of books considered objectionable—it is the reason the ALA launched its annual Banned Books Week forty years ago to highlight local challenges to books. But these perennial community-level attempts to challenge books deemed “subversive” or “indecent” have reached a new level of intensity.

Currently, in America’s riven political ecosystem, the hyper-charged urge to purge has been fused with anger over vaccinations and mask mandates and the assault on teaching any American history that doesn’t fit a suitably patriotic mold. In such states as Florida, Texas, and Virginia, the backlash has grown intense and been wrapped in the pretense of giving parents “control” over their children’s education. The bullseye has moved from Robin Hood, The Communist Manifesto, and The Catcher in the Rye to a new set of targets. Many of the books now under fire deal with race, slavery, gender issues, and of course, sexuality.

Raising the fever pitch are books exploring gay relationships and gender identity. In November 2021, a Virginia school board member was quoted in press reports as saying, “I think we should throw those books in a fire.”In February, a Tennessee pastor went further, leading a book burning that saw Harry Potter and Twilight consigned to the flames—both among the usual suspects in recent book bans and challenges.

We’ve seen these flames before. In fiction, they raged in Ray Bradbury’s dystopic Fahrenheit 451 in which “firemen” burn outlawed books. But they have also roared more frighteningly in fact. Book burnings are actually older than books, dating to ancient times in Greece and China. After Gutenberg’s printing revolution, the Vatican created the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, a catalog of banned books, some of which were burned, sometimes along with their authors—like Giordano Bruno in 1600.

Most notoriously in pre-World War II Germany, some 25,000 “un-German” books were consigned to Nazi bonfires in May 1933. Targeted by Hitler’s loyal disciples were works by German Jews and Marx, Freud, and Einstein. Books by German novelists Thomas Mann and Eric Maria Remarque—author of the World War I classic All Quiet on the Western Front— went into the flames along with such American writers as Ernest Hemingway, Jack London, and Helen Keller.

Book Burning May 10, 1933 Image courtesy US Holocaust Memorial Museum https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/conten...

Can it happen here? It has.

Nearly a century before the Nazi book burnings, a concerted effort to flood the slaveholding states with abolitionist literature was met with fire. In the summer of 1835, an angry mob raided a Charleston, South Carolina post office and consigned thousands of abolitionist pamphlets to a bonfire. The book burning was topped off with an effigy of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison being set ablaze. Garrison was lucky. Tragically, abolitionist publisher Elijah Lovejoy was not. Two years later, a mob intent on burning anti-slavery literature in Alton, Illinois murdered Lovejoy as he tried to defend his presses. A century later, in 1939, California growers burned Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Grapes of Wrath.

Scrubbing the nation’s public square of “offensive” materials and torching books—despite the protections in the Bill of Rights—are as American as apple pie, lynch mobs, burning crosses, and now, tiki torches.

But there’s something new in the equation. The latest wave of book suppression is not simply about “subversion” or “dirty words.” Scratch the surface of recent book bans and it is clear that the assault on free expression cannot be separated from the larger Orwellian effort to sanitize American history, delegitimize literature by gay writers and people of color, and undermine democracy.

This revitalized onslaught carries the distinct whiff of white, Christian nationalism. This is the racial, cultural, and political ideology that once reared its head as nineteenth-century Nativism, the reinvigorated Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s, and the America Firsters of the 1930s.

Claiming that the United States is a “Christian nation,” this strand of anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic American DNA is older than the nation itself. Time has not diminished its power. Now adding “globalists” to their enemies list, white Christian nationalism has been tied to the Charlottesville rioters who chanted “You will not replace us” and the January 6 insurrection by experts who study the movement.

America has no monopoly on this historically powerful faction. A form of white Christian nationalism, with its claims of racial superiority, certainly fed Hitler’s rise in Germany.

And that is why this revived wave of book suppression is a piece of a much larger development. The reason that Maus, a Pulitzer-Prize winning graphic novel-memoir about the Holocaust, was ostensibly pulled from schools in Tennessee was for some of its language and a discreet cartoon illustration of the author’s mother—an Auschwitz survivor—naked in the bathtub where she had committed suicide. But its critics apparently sought a kinder, gentler discussion of the Holocaust, although any attempts to soften that history tiptoe dangerously toward denialism. This is how history goes down 1984’s “Memory Hole.”

It is more than a little ironic that this onslaught of suppression comes as many on the Right decry the so-called “cancel culture” of the Left. Claiming their right to free speech is under attack, modern-day “book burners” crush that freedom under their boot heels as they attempt to distort or erase history and silence unwelcome voices. When such voices and ideas are deemed a threat and suppressed by the government, religious authorities, or a political party, we teeter on the thin ice of authoritarianism. The ice cracks when a fictional character is attacked—whether it is Homer Simpson, Huckleberry Finn, or Robin Hood. All three have come under fire over the years.

Banning books, legislating against “divisive concepts” in history class, and purging diversity all come straight from the playbook of the Strongman. He knows the power of the pen. Books make us think. Literature cultivates the free mind. Writers are truth-tellers. In 1917, Soviet leader Lenin ordered a “Decree on Press” threatening closure of publications critical of the Bolsheviks. Authoritarians know the danger posed by truth. And they are more than willing to use sword and flame to cut it down.

The question is what can we do about it?

“The antidote to authoritarianism is not some form of American authoritarianism,” Cooper Union librarian David K. Berninghausen told the Times in 1952. “The antidote is free inquiry.”

When Robin Hood was threatened by a textbook commissioner in 1953, some Indiana State University students fought back. Five of them gathered chicken feathers, dyed them green, and spread them across campus. Their protest caught on at other colleges, including UCLA, where two hundred students dressed up as Sherwood Forest’s Merry Men for a Green Feather drop. A clever, well-aimed protest, the Green Feather movement broke no windows or legs. Robin Hood was spared.

But those more innocent days are gone. In the internet age, the lines are more sharply drawn, sides set in stone, and the stakes much higher.

That is why dumping some green feathers or wearing an “I READ BANNED BOOKS” t-shirt will not be enough for this moment. If we care, we must take to heart Ike’s advice and “read every book.” We must firmly resolve to read. But buying and reading Maus or Toni Morrison’s Beloved are only the first steps.

We have to make sure that others can read these books. We must be audacious in support of free libraries and vigorously support all teachers who want to encourage students to read, debate, and think for themselves. And we must vigilantly push back on politicians and schoolboards purging libraries of uncomfortable truths. A few loud voices dominating a schoolboard or town hall meeting do not a majority make. To allow a noisy minority to dictate what we read and teach is skating on that thin ice of totalitarian loyalty oaths typical of a Mussolini or Stalin.

On this final note, history is clear. When you have succeeded in marking a writer as “degenerate” or “immoral”—as the Nazis did—you have moved towards dehumanizing them. It is a few short perilous steps from censorship to suppression to a conflagration far worse. In Berlin, on the spot where Nazis threw books into a bonfire, there is a plaque citing German playwright Heinrich Heine’s 1820 words, which read in part: “Where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people as well.”

The road to Hell is lit by burning books.

© Copyright 2022 Kenneth C. Davis All rights reserved

June 5, 2022

Don’t Know Much About® D-Day

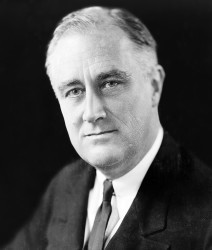

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “D-Day Prayer” in an announcement to the nation of the invasion of Normandy (June 6, 1944)

Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933

My fellow Americans: Last night, when I spoke with you about the fall of Rome, I knew at that moment that troops of the United States and our allies were crossing the Channel in another and greater operation. It has come to pass with success thus far.

And so, in this poignant hour, I ask you to join with me in prayer:

Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our Nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity.

Lead them straight and true; give strength to their arms, stoutness to their hearts, steadfastness in their faith.

They will need Thy blessings. Their road will be long and hard. For the enemy is strong. He may hurl back our forces. Success may not come with rushing speed, but we shall return again and again; and we know that by Thy grace, and by the righteousness of our cause, our sons will triumph.

They will be sore tried, by night and by day, without rest-until the victory is won. The darkness will be rent by noise and flame. Men’s souls will be shaken with the violences of war.

Franklin Roosevelt’s D-Day Prayer Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum

“Into the Jaws of Death – U.S. Troops wading through water and Nazi gunfire” by Robert F. Sergeant (National Archives)

In the largest amphibian assault in history, Allied armies crossed the English Channel to land on five beaches in Normandy in northern France. The invasion force involved 700 ships, 4,000 landing craft, 10,000 planes, and some 176,000 Allied troops from twelve countries. The allied forces were commanded by future President, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The day was chaotic, brutal and bloody.

Steven Spielberg’s World War II epic, Saving Private Ryan, brought the reality of combat home to millions, but many moviegoers did not know which battle the film depicted, or when and why it happened. The assault, code-named Operation Overlord, occurred June 6, 1944, against Hitler’s Germany.

By the end of the day on June 6, 1944, the allies had taken all five beaches that had been targeted. The combined allied losses on that day have been recently stated at 4,415 dead, according to the National D-Day Memorial.

The German army did not formally surrender until May 7, 1945. May 8, 1945 was declared V.E. (Victory in Europe) Day.

More D-Day resources can be found at the FDR Library and Museum

Read more about FDR’s life and administration and World War II in Don’t Know Much About® History and Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

Don’t Know Much About ® the “Marshall Plan”

(Originally posted in 2012)

“Foreign aid” is not just “do-gooder” national policy. It is an effective means to influence future outcomes. There is no better example than the program that came to be called the “Marshall Plan.”

Seventy-five years ago, on June 5, 1947, Secretary of State George C. Marshall gave Harvard’s commencement address, introducing and justifying the European Recovery Program, which became known as the Marshall Plan.

Marshall (born December 31, 1880) had been the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army during World War II and Winston Churchill hailed him as the “true organizer of victory.” The plan, part of the Cold War program of “Containment” championed by George F. Kennan, and put forth by President Harry S. Truman, is credited with restoring the economies of post-World War II western Europe. At Harvard, Marshall said:

The truth of the matter is that Europe’s requirements for the next three or four years of foreign food and other essential products—principally from America—are so much greater than her present ability to pay that she must have substantial additional help, or face economic, social and political deterioration of a very grave character. …Aside from the demoralizing effect on the world at large and the possibilities of disturbances arising as a result of the desperation of the people concerned, the consequences to the economy of the United States should be apparent to all. It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos.

Conceived by Undersecretary of State Will Clayton and first proposed by Secretary of State Dean Acheson, the Marshall Plan pumped more than $12 billion into selected war torn European countries during the next four years. (The countries participating were Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, West Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and Turkey.)

It provided the economic side of President Truman’s policy of “Containment” by removing the economic dislocation that might have fostered Communism in Western Europe. It also set up a Displaced Persons Plan under which some 300,000 Europeans, many of them Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, were granted American citizenship. By most accounts, the Marshall Plan was the most successful undertaking of the United States in the post-war era and is often cited as the most compelling argument in favor of foreign aid.

By most measures, the Marshall Plan must be considered an enormously successful undertaking that helped return a devastated Europe to health. allowing free market democracies to flourish while Eastern Europe, hunkered down under repressive Soviet controlled regimes, stagnated socially and economically.

Marshall was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953 before his death on October 16, 1959. For more about Marshall, here is a link to the nonprofit Marshall Foundation.

You can read more about the Marshall Plan and the Cold War era in the newly revised and updated edition of Don’t Know Much About History.

June 4, 2022

STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy

Read more about this devastating moment in Chinese history in STRONGMAN.

An audiobook is available from Penguin Random House

Strongman named among Washington Post Best Children’s and Young Adult Books of 2020 Named to “Best Children’s Books of the Year-2021”

by the Bank Street College of EducationNamed to “Best Young Adult Books of the Year” by Kirkus ReviewsNamed to “Best YA Books of 2020 for Understanding the US Today” Kirkus ReviewsStarred review from Kirkus Reviews: “History’s warnings reverberate in this gripping read about five dictatorial strongmen. A pitch-perfect balance of nuanced reflection and dire warning.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Publishers Weekly: “A fascinating, highly readable portrayal of infamous men that provides urgent lessons for democracy now.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Shelf Awareness: “Kenneth C. Davis…conveys his plentiful knowledge of dictators in this powerful, spine-tingling biographic work that covers five of the world’s most horrifying autocrats. Grounded in thorough research, Strongman expertly explores the fragility of democracy …” Read the full review here

Named to “Best Children’s Books of the Year-2021”

by the Bank Street College of EducationNamed to “Best Young Adult Books of the Year” by Kirkus ReviewsNamed to “Best YA Books of 2020 for Understanding the US Today” Kirkus ReviewsStarred review from Kirkus Reviews: “History’s warnings reverberate in this gripping read about five dictatorial strongmen. A pitch-perfect balance of nuanced reflection and dire warning.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Publishers Weekly: “A fascinating, highly readable portrayal of infamous men that provides urgent lessons for democracy now.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Shelf Awareness: “Kenneth C. Davis…conveys his plentiful knowledge of dictators in this powerful, spine-tingling biographic work that covers five of the world’s most horrifying autocrats. Grounded in thorough research, Strongman expertly explores the fragility of democracy …” Read the full review here•2021 YALSA Nonfiction Award nominee

A review in Booklist says, “Davis does not sugarcoat his material, inviting long thoughts with his assertion that this is a decidedly human story that points to real people as evidence that evil exists in this troubled world.”

In addition to telling how these men took unlimited power, brought one-party rule to their nations, and were responsible for the deaths of millions of people, the book offers a brief history of Democracy and discusses the present threat to democratic institutions around the world.

In a time when Democracy is under assault across the globe, it is more important than ever to understand how a Strongman takes power and how quickly democracy can vanish –even as millions cheer its death.

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR STRONGMAN

“I found myself engrossed in it from beginning to end. I could not help admiring Davis’s ability to explain complex ideas in readable prose that never once discounted the intelligence of young readers. It is very much a book for our time.”

—Sam Wineburg, Margaret Jacks Professor of Education & History, Stanford University, author of Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone).

“Strongman is a book that is both deeply researched and deeply felt, both an alarming warning and a galvanizing call to action, both daunting and necessary to read and discuss.”

—Cynthia Levinson, author of Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws That Affect Us Today

“A wake-up call to democracies like ours: we are not immune to despots . . . Strongman demonstrates that democracy is not permanent, unless it is collectively upheld. This book shakes that immortality narrative.”

—Jessica Ellison, President of the Minnesota Council for the Social Studies; Teacher Education Specialist, Minnesota Historical Society

Rarely does a history book take such an unflinching look at our common future, where the very presence of democracy is less than certain; even rarer is a history book in which the author’s moral convictions incite young readers to civic engagement; rarest of all, a history book as urgent, as impassioned, and as timely as Kenneth C. Davis’ Strongman.

—Eugene Yelchin, author of the Newbery Honor book Breaking Stalin’s Nose.

May 28, 2022

Who Said It (5/29/2022)

John F. Kennedy, born on May 29, 1917: “Remarks at Amherst College upon receiving an Honorary Degree,” October 26, 1963, Public Papers of the Presidents: John F. Kennedy, 1963.

President John F. Kennedy (1961)

“We must never forget that art is not a form of propaganda; it is a form of truth….”

“….It may be different elsewhere. But democratic society – in it, the highest duty of the writer, the composer, the artist is to remain true to himself and to let the chips fall where they may.”

Source: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Who Said It (5/29/2017)

John F. Kennedy, born on May 29, 1917: “Remarks at Amherst College upon receiving an Honorary Degree,” October 26, 1963, Public Papers of the Presidents: John F. Kennedy, 1963.

President John F. Kennedy (1961)

“We must never forget that art is not a form of propaganda; it is a form of truth.”

Source: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum