Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 19

August 5, 2022

Don’t Know Much About® the Tonkin Resolution

[8/2016 post updated 8/5/2022]

What was the Tonkin Resolution?

USS Maddox Operating at sea, circa the early 1960s. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command

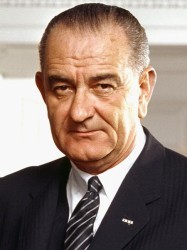

On August 5, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson put the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution before Congress. On August 7, Congress approved what soon became the legal foundation for Lyndon B. Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War.

It came in August 1964 with a brief encounter in the Gulf of Tonkin, the waters off the coast of North Vietnam where the U.S. Navy posted warships loaded with electronic eavesdropping equipment enabling them to monitor North Vietnamese military operations and provide intelligence to CIA-trained South Vietnamese commandos. One of these ships, the U.S.S. Maddox was reportedly fired on by gunboats from North Vietnam.

Lyndon B. Johnson (March 1964) Photo: Arnold Newman, White House Press Office

The reported attack came in the midst of LBJ’s 1964 campaign against hawkish Republican Barry Goldwater. President Johnson felt the incident called for a tough response and had the Navy send the Maddox and a second destroyer, the Turner Joy, back into the Gulf of Tonkin. A radar man on the Turner Joy saw some blips, and that boat opened fire. On the Maddox, there were also reports of incoming torpedoes, and the Maddox began to fire. There was never any confirmation that either ship had actually been attacked. Later, the radar blips would be attributed to weather conditions and jittery nerves among the crew.

According to Stanley Karnow’s Vietnam: A History,

“Even Johnson privately expressed doubts only a few days after the second attack supposedly took place, confiding to an aide, ‘Hell, those dumb stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish.’”

Johnson ordered an air strike against North Vietnam and then called for passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. This legislation gave the president the authority to “take all necessary measures” to repel attacks against U.S. forces and to “prevent further aggression.” The resolution not only gave Johnson the powers he needed to increase American commitment to Vietnam, but allowed him to blunt Goldwater’s accusations that Johnson was “timid before Communism.”

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution passed the House unanimously after only forty minutes of debate. In the Senate, there were only two voices in opposition. What Congress did not know was that the resolution had been drafted several months before the Tonkin incident took place. In June 1964, on LBJ’s orders, according to journalist-historian Tim Weiner,

“Bill Bundy, the assistant secretary of state for the Far East, brother of the national security adviser, and a veteran CIA analyst, had drawn up a war resolution to be sent to Congress when the moment was ripe.” (Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA, p. 280)

Congress, which has sole constitutional authority to declare war, had handed that power over to Johnson, who was not a bit reluctant to use it.

Testifying before the Senate, [Defense Secretary] McNamara lied, denying any American involvement in the Tonkin Gulf attacks: “Our Navy played absolutely no part in, was not associated with, was not aware of any South Vietnamese actions, if there were any.”

Three days after the announcement of the “incident,” the administration persuaded Congress to pass the Tonkin Gulf Resolution to approve and support “the determination of the president, as commander in chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression” — an expansion of the presidential power to wage war that is still used regularly. Johnson won the 1964 election in a landslide.

–“The Secrets and Lies of the Vietnam War, Exposed in One Epic Document,” New York Times (June 9, 2021)

One of the senators who voted against the Tonkin Resolution, Oregon’s Wayne Morse, later said,

“I believe that history will record that we have made a great mistake in subverting and circumventing the Constitution.”

After the vote, Walt Rostow, an adviser to Lyndon Johnson, remarked,

“We don’t know what happened, but it had the desired result.”

In January 1971, Congress repealed the Gulf of Tonkin resolution as popular opinion grew against a continued U.S. military involvement in Vietnam

Since Vietnam, United States military actions have taken place as part of United Nations’ actions, in the context of joint congressional resolutions, or within the confines of the War Powers Resolution (also known as the War Powers Act) that was passed in 1973, over the objections (and veto) of President Richard Nixon.”

The War Powers Resolution came as a direct reaction to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as Congress sought to avoid another military conflict where it had little input.

“The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and the Limits of Presidential Power” National Constitution Center

In 2005, the National Security Agency (NSA) issued a report reviewing the Tonkin incident in which it said “no attack had happened.” (Weiner, p. 280)

The National Endowment for the Humanities website Edsitement offers teaching resources on Tonkin and the escalation of the Vietnam War.

Read more about Vietnam, LBJ and his administration in Don’t Know Much About® History, Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents. The Vietnam War and the Tonkin Resolution are also covered in a chapter on the Tet offensive of 1968 in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR.

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

August 4, 2022

The Month That Changed The World: July 16-August 15, 1945

[Originally posted in 2020 to mark the 75th Anniversary of the end of World War II and the transformation of the modern world; Revised July 30, 2022]

From the “Trinity” Test to Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Japan’s Surrender:

The Month That Changed the World

Formal surrender aboard USS Missouri Sept. 2. 1945 https://www.history.navy.mil/our-coll...

The following timeline summarizes the extraordinary series of events that helped make the modern world between July 16 and August 15, 1945.

The Atomic Bomb Dome-Hiroshima (Photo Courtesy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered)

On August 6, 1945, the New York Times asked:

“What is this terrible new weapon?”

(New York Times, August 6, 1945: “First Atomic Bomb Dropped on Japan”)

The story followed the announcement made that day by President Harry S. Truman:

“SIXTEEN HOURS AGO an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of T.N.T. It had more than two thousand times the blast power of the British ‘Grand Slam’ which is the largest bomb ever yet used in the history of warfare.”

August 6, 1945

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

(“Statement by the President Announcing the Use of the A-Bomb at Hiroshima”: Truman Library and Museum)

The use of the first atomic bomb followed the successful test detonation –the goal of the wartime Manhattan Project — and the beginning of a series of world-changing events.

• July 16, 1945 the first atomic device, nicknamed “the Gadget,” is detonated in the “Trinity” test at Alamogordo, New Mexico. Read this account of the test in National Geographic.

New York Times reporter Dennis Overbye visited the site in 2021. His report “Touring Trinity, the Birthplace of Nuclear Dread”:

“The detonation created a crater eight feet deep, a half-mile wide and lined with glassy pebbles called trinitite: sand that had been swept up in the fireball, vaporized and then fell back down in molten radioactive droplets.”

The Trinity test, 15 seconds after detonation. Photo courtesy of David Wargowski Source: National Museum of Nuclear Science & History

In the course of the next weeks, the world would be transformed, with the arrival of the Atomic Age, Japan’s surrender, the end of World War II, the charter of the United Nations, and the beginning of the Cold War.

The development, testing, and use of atomic bombs is documented by the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History.

• July 17 In Potsdam, near Berlin in defeated Germany, President Harry S. Truman comes face to face with the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. Truman had taken office upon the death of President Roosevelt on April 12, 1945 without knowledge of the Manhattan Project or the atomic bomb’s existence. Having been told about the potential weapon, Truman is informed of the successful “Trinity” test while meeting Soviet Strongman Stalin with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the European postwar conference.

Harry S. Truman and Joseph Stalin at Potsdam (Public Domain: President Harry S. Truman Library and Museum)

“I told Stalin that I am no diplomat but usually said yes or no to questions after hearing all the argument.”

Read about Stalin’s rise to power in Strongman

Following the New Mexico test success, the components of the atomic bomb are loaded onto the USS Indianapolis in San Francisco for transport to an airbase on Tinian Island in the Pacific. Many of the crew of nearly 1,200 men have no idea what the ship is carrying.

•July 19 In the United States, Congress approves the Bretton Woods agreement, an international pact designed to avoid postwar financial crises like those that followed World War I. The agreement creates the International Money Fund and what later becomes the World Bank.

The Japanese cities of Choshi, Hitachi, Fukui and Okazaki are struck by 600 B-29 Superfortress bombers dropping some 4,000 tons of bombs — the largest employment of the bomber to date.

The USS Indianapolis reaches Pearl Harbor in the first leg of its voyage to deliver the atomic bomb components.

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/515009

• July 21 “A senior US Army Air Force intelligence officer in the Pacific distributed a report declaring: ‘The entire population of Japan is a proper Military Target . . . THERE ARE NO CIVILIANS IN JAPAN.’” Richard B. Frank via World War II Museum.

Truman and Churchill at Potsdam

https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/photogr...

In Potsdam, Truman and Churchill privately agree to use the atomic bomb if Japan does not surrender. Read about Truman’s decision from the National Park Service Harry S. Truman National Historic Site.

• July 22 In what is described as the last surface battle of World War II, the U.S. Navy sinks Japanese supply ships in the “Battle of Sagami Bay” (“Tokyo Bay”). Naval bombardments of the Japanese mainland continue, along with B-29 bombing raids striking Japanese cities.

In China, the American Far East Air Force attacks Japanese troops, airfields, and shipping near Shanghai.

• July 23 In Potsdam, Secretary of War Henry Stimson receives atomic bomb target list. In order of choice they are: Hiroshima, Kokura, and Niigata. He also receives an estimate of atomic bomb availability: “Little Boy” should be ready for use on Aug. 6, second “Fat Man-type” by Aug. 24. There are plans for a total of seven bombs available by December.

• July 24 Truman informs Stalin of a “new weapon of unusual destructive force.”

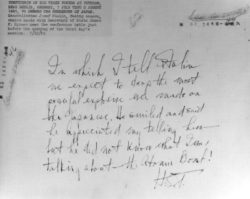

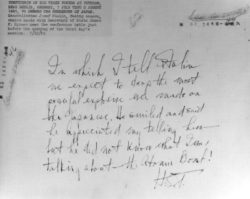

“In which I tell Stalin we expect to drop the most powerful explosive ever made on the Japanese. He smiled and said he appreciated my telling him–but he did not know what I was talking about–the Atomic Bomb! HST”

Truman’s note on back of photograph from Potsdam Conference describing his conversation with Stalin about the atomic bomb. Source: Truman Museum https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/photogr...

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

But Stalin already knows about the atomic bomb because of a network of spies inside the Manhattan Project. The Soviet push to capture Berlin in April and May 1945 was motivated in part by Stalin wanting to capture German scientists working on a Nazi atomic bomb and tons of uranium held in a Berlin lab. This episode is recounted in the “Berlin Stories” chapter of my book The Hidden History of America at War.

• July 25 Truman writes in his diary that he has made the decision to use “the most destructive bomb in the history of the world… I have told the Sec. of War, Mr. Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children.”

Sources: Truman Library and Museum National Security Archive, George Washington University

• July 26 British general election returns are announced; Prime Minister Winston Churchill is defeated and replaced by Clement Attlee.

“The landslide victory comes as a major shock to the Conservatives following Mr Churchill’s hugely successful term as Britain’s war-time coalition leader, during which he mobilised and inspired courage in an entire nation.”

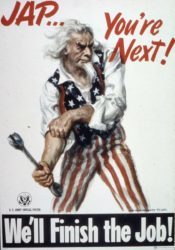

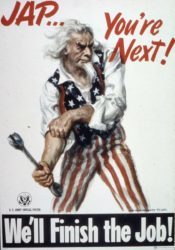

U.S. Propaganda poster (Source National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/513563)

–BBC

At the Potsdam Conference, the Potsdam Declaration demands an “Unconditional surrender” by Japan. Issued by Great Britain, China, and the U.S., it threatens:

“The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

The USS Indianapolis reaches Tinian that day.

USS Indianapolis 10 July 1945, after final overhaul and repair of combat damage. Photograph from the Bureau of Ships Collection in the U.S. National Archives (Naval History and Heritage Command https://usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.m...)

“Indianapolis departed San Francisco on 16 July 1945, foregoing her post-repair shakedown period. Touching at Pearl Harbor on 19 July, she raced on unescorted and reached Tinian on 26 July, covering some 5,000 miles from San Francisco in only ten days.”

After delivering the atomic bomb components, the ship departs for Guam and the Philippines.

• July 27 American B-29 SuperFortress bombers drop 600,000 leaflets over eleven Japanese cities warning that they are targets of bombings.

“But, unfortunately, bombs have no eyes. So, in accordance with America’s humanitarian policies, the American Air Force, which does not wish to injure innocent people, now gives you warning to evacuate the cities named and save your lives.” –from a “LeMay Leaflet,” named for General Curtis LeMay, architect of the Pacific bombing campaign (Atomic Heritage Foundation)

In England, Winston Churchill has a final meeting with his joint chiefs of staff.

• July 28 In New York City, an Army B-25 bomber on a routine mission flies into the Empire State Building –then the world’s tallest skyscraper. Three crew members and eleven people in the building are killed.

“B-25 Mitchell bomber smashed beyond recognition into Empire State Building. This is a picture of the wreckage-strewn 79th floor where the bomber tore a 18-foot hole in wall. Propeller is embedded in the wall at the left.” Source: New York Daily News

“I was at the file cabinet and all of a sudden the building felt like it was just going to topple over,” [office worker Gloria] Pall said. “It threw me across the room, and I landed against the wall. People were screaming and looking at each other. We didn’t know what to do. We didn’t know if it was a bomb or what happened. It was terrifying.” Source: National Public Radio

In Potsdam, newly-elected Prime Minister Clement Attlee of the Labour Party arrives to rejoin the talks which are nearly concluded. Attlee led post-war UK until 1951.

“As Prime Minister, he enlarged and improved social services and the public sector in post-war Britain, creating the National Health Service and nationalising major industries and public utilities. Attlee’s government also presided over the decolonisation of India, Pakistan, Burma, Ceylon and Jordan, and saw the creation of the state of Israel upon Britain’s withdrawal from Palestine.” Official UK Biography of Attlee.

• July 29 The Japanese government rejects the Potsdam Declaration surrender demand.

Just after midnight, the Indianapolis is struck by a Japanese torpedo.

• July 30 Torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, the Indianapolis sinks in twelve minutes. Between 800 and 900 of the crew of nearly 1,200 are plunged into the shark-infested waters.

“What followed was an ordeal of hell on earth for those who survived the sinking. For a whole host of reasons, many related to the secrecy of her atom bomb mission, the rest of the Navy did not know that Indianapolis was missing.”

— Sam Cox (Rear Adm., USN, Ret.), “Lest We Forget: USS Indianapolis and her sailors” (inactive link)

–Read “The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis” via the National Archives including a film clip from the classic scene in Jaws in which Captain Quint describes the sinking of the ship and the shark attacks that followed.

• July 31 The assembly of the atomic bomb, code named “Little Boy,” is completed. The final arming of the bomb will be done in-flight.

In Potsdam, Truman is notified of the bomb being ready. He writes a message that concludes:

“Release when ready, but not sooner than August 2. HST”

According to the Truman Library:

The actual reply that President Truman wrote on July 31, 1945 (Photo taken by Dawn Wilson at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library)

“No known written record exists in which Harry Truman explicitly ordered the use of atomic weapons against Japan. The closest thing to such a document is this handwritten order, addressed to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, in which Truman authorized the release of a public statement about the use of the bomb. It was written on July 31, 1945 while Truman was attending the Potsdam Conference in Germany. In effect, this served as final authorization for the employment of the atomic bomb, though the expression ‘release when ready’ refers to the public statement.”

• August 1 The atomic bomb is ready and flight orders are prepared. But weather delays the mission. Of four potential target cities, Hiroshima is chosen as the primary target.

In Potsdam that day, the Big Three wrap up their meetings and discuss plans for the trials of war criminals that later become known as the Nuremberg Trials.

Read my 2021 post on the Nuremberg Trials.

In the Pacific, hundreds of survivors from the Indianapolis desperately try to stay afloat in the shark-infested waters.

“In that clear water you could see the sharks circling. Then every now and then, like lightning, one would come straight up and take a sailor and take him straight down.” – Survivor of the Indianapolis sinking to the BBC.

• August 2

The Big Three at the end of the Potsdam Conference: Front row (Left to Right) Prime Minister Attlee, President Truman, Generalissimo Stalin. Source: Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives.

Shortly after midnight, the Potsdam Conference concludes with a joint communique. It includes reference to the United Nations, whose organization and charter had been completed on June 26 at a conference in San Francisco.

Truman speaks of a future Washington meeting with the Soviet leader, but he and Stalin never meet again.

What was clear was that the Conference had solidified the Soviet Union’s domination over much of Eastern Europe, including the eastern half of a divided Germany. Admiral William D. Leahy, Truman’s Chief of Staff, later wrote:

“The Soviet Union emerged at this time as the unquestioned all-powerful influence in Europe….”

The U.S. Navy is still unaware that the Indianapolis has gone down. More than 800 men went into the water and the survivors are spotted by a reconnaissance plane four days after the sinking.

“Marks’s crew dropped rubber rafts and supplies as they witnessed continuing shark attacks. Disregarding orders not to land at sea, the pilot touched down and began taxiing to pick up survivors.

As darkness set in, and as Marks waited for rescue vessels, he pulled men from the water into his aircraft. When the plane’s fuselage was at maximum capacity, survivors were tied to the wings with parachute cord. The pilot and his crew rescued a total of 56 men. Once signaled, a total of seven Navy ships converged on the site and rescued the remaining men. Only 317 sailors survived.” –National Archives, “The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis”

Indianapolis’ survivors en route to a hospital following their rescue, early August 1945. Source: Naval History and Heritage Command

“Looking for a scapegoat, the US Navy placed responsibility for the disaster on Captain McVay, who was among the few who managed to survive. For years he received hate mail, and in 1968 he took his own life. The surviving crew, including Cox, campaigned for decades to have their captain exonerated – which he was, more than 50 years after the sinking.” —“USS Indianapolis Sinking,” BBC

The commander of the Indianapolis, Charles B. McVay III, was the only World War II U.S. Navy captain to be court-martialed for the sinking of his ship. McVay died by suicide in 1968. In 2001, he was exonerated by an act of Congress.

• August 4 Colonel Paul Tibbets briefs the men of the 509th Composite Group -the weapon delivery arm of the Manhattan Project. Tibbets is the commander of the unit. His men do not know the nature of the bomb they will carry.

• August 5 The bombing mission is confirmed and Colonel Paul Tibbets announces he will pilot the plane which he names “Enola Gay,” after his mother.

Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr., Pilot of the Enola Gay, the Plane that Dropped the Atomic Bomb August 6, 1945 (National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/535737)

• August 6 At 0245 local time on Tinian,

“Enola Gay begins takeoff roll. [Pilot] Colonel Paul Tibbets says to co-pilot Robet Lewis, ‘Let’s go.’ He pushes all of the throttles forward. The overloaded Enola Gay lifts slowly into the night sky, using all of the more than two miles of runway.”

—Atomic Heritage Foundation, minute-by-minute timeline of Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings.

0730:

“Tibbets announces to the crew: ‘We are carrying the world’s first atomic bomb.’ He pressurizes the Enola Gay and begins an ascent to 32,700 feet. The crew puts on their parachutes and flak suits.”

0912: Control of the Enola Gay is handed over to the bombardier, Thomas Ferebee, as the bomb run begins. A Radio Hiroshima operator reports that three planes have been spotted.

0914 (0814 Hiroshima time): Tibbets tells his crew, “On glasses.”

–Atomic Heritage Foundation Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombing Timeline

8:15 AM (Hiroshima local time) The first atomic bomb is detonated over Hiroshima.

“In less than one second, the fireball had expanded to 900 feet. The blast wave shattered windows for a distance of ten miles and was felt as far away as 37 miles. Over two-thirds of Hiroshima’s buildings were demolished. The hundreds of fires, ignited by the thermal pulse, combined to produce a firestorm that had incinerated everything within about 4.4 miles of ground zero.”

Source: Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered.

“In the street, the first thing he saw was a squad of soldiers who had been burrowing into the hillside opposite, making one of the thousands of dugouts in which the Japanese apparently intended to resist invasion, hill by hill, life for life; the soldiers were coming out of the hole, where they should have been safe, and blood was running from their heads, chests, and backs. They were silent and dazed.

Under what seemed to be a local dust cloud, the day grew darker and darker.”

–John Hersey, “Hiroshima,” New Yorker (August 24, 1946)

In Hiroshima, the estimated death toll reaches eighty thousand people killed instantly; as many as 90 percent of the city’s nurses and doctors also die instantly. By 1950, as many as 200,000 die as a result of long-term effects of radiation.

“Historians say General Groves understood the radiation issue as early as 1943 but kept it so compartmentalized that it was poorly known by top American officials, including Harry S. Truman. At the time he authorized the Hiroshima bombing, President Truman, scholars say, knew almost nothing of the bomb’s radiation effects.”

Read: “The Black Reporter Who Exposed a Lie about the Atomic Bomb” New York Times

In his official announcement, President Truman said,

It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.

Read Don’t Know Much About Hiroshima for more details about the bombing and its aftermath.

•August 7 A report to the Japanese Imperial Army General Staff reads:

“The whole city of Hiroshima was destroyed instantly by a single bomb.” (Atomic Heritage Foundation)

On Guam, the decision to use a second device is made and the mission date set for August 10, then moved to August 9 over weather concerns.

Fat Man being lowered and checked on transport dolly for airfield trip Image Source: Heritage Foundation https://www.atomicheritage.org/histor...

•August 8 Fulfilling a pledge Stalin had made earlier at the Yalta conference, the Soviet Union declares war on Japan and invades Manchuria the next day, sending more than one million troops into Japanese-held territory.

The Japanese military leadership was still divided over the surrender demand, with some leading generals vowing to fight to the death. A coup against Emperor Hirohito began to be planned by members of the Japanese military.

A plutonium bomb code named “Fat Man” is prepared on Tinian. It will be carried by a B-29 called “Bockscar.” The primary target is the city of Kokura, home to a large munitions plant.

The crew of the B-29 called “Bockscar” taken after the Nagasaki bombing (Image: U.S. Air Force)

•August 9

0347: Bockscar, piloted by Major Charles Sweeney, lifts off from Tinian Island. The target of choice is Kokura Arsenal.

Clouds and smoke from nearby fires obscure Kokura, so “Fat Man” is dropped over the secondary target, the city of Nagasaki, with a population estimated at 263,000, a city that was home to two Mitsubishi military plants. It is also the site of a prisoner of war camp.

“Nagasaki was a city on the west coast of Kyushu on picturesque Nagasaki Bay. It was famous as the setting for Puccini’s beautiful opera Madame Butterfly. It was also home to two huge Mitsubishi war plants on the Urakami River. This complex was the primary target, but because the city was built in hilly, almost mountainous terrain, it was a much more difficult target than Hiroshima…

Fat Man exploded at 1,840 feet above Nagasaki and approximately 500 feet south of the Mitsubishi Steel and Armament Works with an estimated force of 22,000 tons of TNT.

Unlike Hiroshima, there was no firestorm at Nagasaki. Despite this, the blast was more destructive to the immediate area, due to the topography and the greater power of Fat Man.”

—Hiroshima & Nagasaki Remembered

The death toll in Nagasaki also reaches 80,000 by the end of 1945. Read a full account of this mission in “Nagasaki: The Last Bomb” by Alex Wellerstein (New Yorker, August 7, 2015)

The National Archives “Unwritten Record” blog also offers resources on the atomic bombings.

•August 10 After Nagasaki is bombed, Truman orders no more strikes without his authorization. Another plutonium core for a third weapon is prepared for shipment.

September 24, 1945, 6 weeks after Nagasaki was destroyed by the world’s second atomic bomb attack. Photo by Cpl. Lynn P. Walker, Jr. (USMC) National Archives FILE #: 127-N-136176

Although an unofficial surrender message was sent by a Japanese news agency, the Japanese cabinet was divided and no decision was made. The Emperor would not surrender his sovereignty.

•August 11 The U.S. Secretary of State James Byrnes rejects any conditional surrender and states that the Emperor and Japan’s government will be subject to the Allied Powers and declares that any future Japanese government must reflect the will of the people.

Soviet troops invade South Sakhalin island, Japanese-held territory.

•August 12-13 Soviet troops advance into the Korean peninsula.

Emperor Hirohito agrees to accept the terms of Secretary Byrnes’s note and orders the suspension of military activity. He records a surrender announcement. Military officers began to plot against Hirohito in a coup known as the “Kyujo incident.”

•August 13 The bombing of Japan, including firebombing, resumes with more than 1,000 B-29s taking part.

Japanese officers continue to seek allies in their planned coup against the Imperial government.

Residential section of Tokyo after the March 1945 air raids. (Wikimedia commons http://www.kmine.sakura.ne.jp/kusyu/k...

•August 14 (August 15 in Japan): The military coup fails and several plotters commit suicide.

In an extraordinary address recorded earlier, the Emperor of Japan is heard on the radio for the first time and accepts the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration, agreeing to the unconditional surrender.

Read: “The Emperor’s Speech” by Max Fisher (The Atlantic, August 15, 2012)

At a White House conference, according to United Press International, Truman says:

“This is the day when Fascist and police governments cease to exist in the world. This is the day for democracy.”

-Source: “Japan Surrenders Unconditionally, World At Peace” UPI archives

Truman announces Japan’s surrender to reporters in Oval Office.

Credit: Rowe, Abbie National Park Service Harry S. Truman Library & Museum.

Across America and England, jubilant crowds fill the streets once more for an unofficial V-J (Victory over Japan) Day, as they had three months earlier on VE Day, May 8,1945, after Germany’s surrender ended the war in Europe.

A video clip of Truman’s August 14 announcement from C-Span.

V-J Day Times Square August 14, 1945 Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c19650

•September 2, 1945 A formal surrender ceremony is performed in Tokyo Bay and that date is also referred to as V-J Day.

Almost since the day the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, critics have second-guessed Truman’s decision and motives. A generation of historians and commentators have defended or repudiated the need for unleashing the atomic weapon. Admiral William D. Leahy, who was with Truman at Potsdam, later wrote in a memoir:

Once it had been tested, President Truman faced the decision as to whether to use it. He did not like the idea, but he was persuaded that it would shorten the war against Japan and save American lives. It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan.

–William D. Leahy, I Was There (1950)

In China, however, the Japanese surrender ended the wartime alliance between the Communists and Nationalists. The Chinese civil war began anew, with the US supporting Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Stalin’s USSR backing Mao Zedong’s Communists.

Read about Mao’s rise to power in Strongman: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy.

Many historians contend that preventing death and casualties in an invasion of Japan was only a partial explanation for the use of the two atomic bombs. The United States was already wary of Stalin and his designs on Japan’s wartime territory. They argue that the use of the two devices was meant to end the war quickly to prevent Stalin from capturing territory held by Japan. It may have also been a signal to Stalin and the Soviet Union that the United States possessed these weapons and was willing to use them.

In other words, the dropping of the atomic bombs became the first volley in the Cold War.

READ about the debate in this Smithsonian article.

In 1952, Albert Einstein –whose 1939 letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt had set the Manhattan Project in motion — wrote a brief essay published by a Japanese magazine Kaizo in which he stated:

I was well aware of the dreadful danger for all mankind, if these experiments would succeed. But the probability that the Germans might work on that very problem with good chance of success prompted me to take that step. I did not see any other way out, although I always was a convinced pacifist. To kill in war time, it seems to me, is in no ways better than common murder.

He concluded:

Gandhi, the greatest political genius of our time has shown the way, and has demonstrated the sacrifices man is willing to bring if only he has found the right way. His work for the liberation of India is a living example that man’s will, sustained by an indomitable conviction is stronger than apparently invincible material power.

–Source Hiroshima & Nagasaki Remembered

You can read more about Hiroshima and the dropping of the atomic bombs in Don’t Know Much About History and more about President Truman in Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents and in The Hidden History of America At War. Read more about Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin in STRONGMAN published on October 6, 2020.

August 1, 2022

When Robin Hood Was Blacklisted

“Fifty-two books by 41 authors will be removed from the libraries of the Alpine School District in Utah, the state’s largest district, following a decision made by the district.” PEN America (August 1, 2022)

Robin Hood was a Commie.

That, at least, is what an Indiana state textbook commissioner thought back in 1953. This official called for schools to ban books mentioning Robin Hood for the simple reason that Robin and his Merry Men robbed from the rich and gave to the poor. Their antics reeked suspiciously of godless Socialism.

It is easy to laugh off this overlooked history as an amusing bit of trivia. Except the Hoosier state assault on Robin Hood was part of a larger nationwide effort to ban books and suppress intellectual freedom. It was led by Senator Joseph McCarthy during the anti-Communist “witch hunts.” It targeted books, writers, and libraries both at home and around the world. And it holds pointed lessons about safeguarding democracy from the forces threatening it today.

After the 1947 blacklisting of the “Hollywood Ten” screenwriters by the House Un-American Affairs Committee (HUAC), Senator McCarthy emerged as the face and unrelenting voice of a crusade against Communist influences in America. In 1950, McCarthy claimed to possess an extensive list of Communists who worked in the State Department. Launching his war on alleged Communist infiltrators as chairman of a Senate committee on government operations, McCarthy was abetted by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. To be labeled a Communist was an accusation from which there was no escape. Claims of innocence or invoking the Fifth Amendment were tantamount to confession.

Set against the Korean War begun in 1950, and with the convictions of Alger Hiss that year for perjury over espionage and the Rosenbergs in 1951 for atomic spying, America’s fear of Communism spread like wildfire. Gaining an army of rabid followers, McCarthy’s crusade to root out subversives widened to focus intently on libraries, which were pressured to purge their collections of works by Marx. By 1952, the New York Times described a pervasive wave of educational book censorship in America. Around the country, self-appointed local committees— “volunteer educational dictators” in the words of one librarian—were coercing librarians to remove books considered “un-American,” the Times found.

This anti-Communist juggernaut was not only steam-rolling domestic libraries. McCarthy sent it on a road trip. In April 1953, McCarthy’s underlings, attorney Roy Cohn and associate David Schine, were dispatched to Europe. Part of their mission was to scrutinize U.S. Information Service libraries, created to provide war-ravaged countries with American books. McCarthy claimed that these collections held thousands of works by Communists. Targeting suspect authors, just as Hollywood had been purged of “Red” screenwriters, Cohn and Schine succeeded in intimidating foreign service officials. No fires were set, but titles by Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, and Howard Fast, among others, were pulled from the shelves.

Inaugurated in January 1953, President Eisenhower was hesitant to challenge McCarthy. But he discreetly fired back. He told a Dartmouth commencement audience in June of that year:

“Don’t join the book burners. Don’t think you are going to conceal faults by concealing evidence that they ever existed. Don’t be afraid to go in your library and read every book, as long as that document does not offend our own ideas of decency.”

–President Eisenhower, “Remarks at the Dartmouth College Commencement”

Unfortunately, Eisenhower’s defense of reading was less than full-throated. Ultimately, his State Dept. folded to McCarthy’s men.

“Only reckless men, under these conditions, could choose to take steps offensive to McCarthy since the President and the Secretary [of State John Foster Dulles] have rarely backed up their subordinates whom McCarthy has singled out for attack.”

—The New Republic June 29, 1953

But America’s librarians were not about to be silenced. Despite the stale caricature of an old lady in a bun shushing the patrons, many librarians spoke out, daringly, given the nation’s fearful mood and threats to their jobs. Responding to this mounting pressure, the American Library Association (ALA), in concert with the American Association of Publishers, issued in June 1953 a “Freedom to Read” statement –since revised several times—that begins, “The freedom to read is essential to our democracy. It is continuously under attack.”

Unfortunately, the ALA was right then—and now. Ike’s “book burners” are back—or perhaps it is more accurate to say they never left. Across America, a concerted effort to purge school and public libraries of “offensive” literature has found new vigor and a louder voice. There is a long history of attempts to rid libraries of books considered objectionable—it is the reason the ALA launched its annual Banned Books Week forty years ago to highlight local challenges to books. But these perennial community-level attempts to challenge books deemed “subversive” or “indecent” have reached a new level of intensity.

Currently, in America’s riven political ecosystem, the hyper-charged urge to purge has been fused with anger over vaccinations and mask mandates and the assault on teaching any American history that doesn’t fit a suitably patriotic mold. In such states as Florida, Texas, and Virginia, the backlash has grown intense and been wrapped in the pretense of giving parents “control” over their children’s education. The bullseye has moved from Robin Hood, The Communist Manifesto, and The Catcher in the Rye to a new set of targets. Many of the books now under fire deal with race, slavery, gender issues, and of course, sexuality.

Raising the fever pitch are books exploring gay relationships and gender identity. In November 2021, a Virginia school board member was quoted in press reports as saying, “I think we should throw those books in a fire.”In February, a Tennessee pastor went further, leading a book burning that saw Harry Potter and Twilight consigned to the flames—both among the usual suspects in recent book bans and challenges.

We’ve seen these flames before. In fiction, they raged in Ray Bradbury’s dystopic Fahrenheit 451 in which “firemen” burn outlawed books. But they have also roared more frighteningly in fact. Book burnings are actually older than books, dating to ancient times in Greece and China. After Gutenberg’s printing revolution, the Vatican created the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, a catalog of banned books, some of which were burned, sometimes along with their authors—like Giordano Bruno in 1600.

Most notoriously in pre-World War II Germany, some 25,000 “un-German” books were consigned to Nazi bonfires in May 1933. Targeted by Hitler’s loyal disciples were works by German Jews and Marx, Freud, and Einstein. Books by German novelists Thomas Mann and Eric Maria Remarque—author of the World War I classic All Quiet on the Western Front— went into the flames along with such American writers as Ernest Hemingway, Jack London, and Helen Keller.

Book Burning May 10, 1933 Image courtesy US Holocaust Memorial Museum https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/conten...

Can it happen here? It has.

Nearly a century before the Nazi book burnings, a concerted effort to flood the slaveholding states with abolitionist literature was met with fire. In the summer of 1835, an angry mob raided a Charleston, South Carolina post office and consigned thousands of abolitionist pamphlets to a bonfire. The book burning was topped off with an effigy of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison being set ablaze. Garrison was lucky. Tragically, abolitionist publisher Elijah Lovejoy was not. Two years later, a mob intent on burning anti-slavery literature in Alton, Illinois murdered Lovejoy as he tried to defend his presses. A century later, in 1939, California growers burned Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Grapes of Wrath.

Scrubbing the nation’s public square of “offensive” materials and torching books—despite the protections in the Bill of Rights—are as American as apple pie, lynch mobs, burning crosses, and now, tiki torches.

But there’s something new in the equation. The latest wave of book suppression is not simply about “subversion” or “dirty words.” Scratch the surface of recent book bans and it is clear that the assault on free expression cannot be separated from the larger Orwellian effort to sanitize American history, delegitimize literature by gay writers and people of color, and undermine democracy.

This revitalized onslaught carries the distinct whiff of white, Christian nationalism. This is the racial, cultural, and political ideology that once reared its head as nineteenth-century Nativism, the reinvigorated Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s, and the America Firsters of the 1930s.

Claiming that the United States is a “Christian nation,” this strand of anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic American DNA is older than the nation itself. Time has not diminished its power. Now adding “globalists” to their enemies list, white Christian nationalism has been tied to the Charlottesville rioters who chanted “You will not replace us” and the January 6 insurrection by experts who study the movement.

America has no monopoly on this historically powerful faction. A form of white Christian nationalism, with its claims of racial superiority, certainly fed Hitler’s rise in Germany.

And that is why this revived wave of book suppression is a piece of a much larger development. The reason that Maus, a Pulitzer-Prize winning graphic novel-memoir about the Holocaust, was ostensibly pulled from schools in Tennessee was for some of its language and a discreet cartoon illustration of the author’s mother—an Auschwitz survivor—naked in the bathtub where she had committed suicide. But its critics apparently sought a kinder, gentler discussion of the Holocaust, although any attempts to soften that history tiptoe dangerously toward denialism. This is how history goes down 1984’s “Memory Hole.”

It is more than a little ironic that this onslaught of suppression comes as many on the Right decry the so-called “cancel culture” of the Left. Claiming their right to free speech is under attack, modern-day “book burners” crush that freedom under their boot heels as they attempt to distort or erase history and silence unwelcome voices. When such voices and ideas are deemed a threat and suppressed by the government, religious authorities, or a political party, we teeter on the thin ice of authoritarianism. The ice cracks when a fictional character is attacked—whether it is Homer Simpson, Huckleberry Finn, or Robin Hood. All three have come under fire over the years.

Banning books, legislating against “divisive concepts” in history class, and purging diversity all come straight from the playbook of the Strongman. He knows the power of the pen. Books make us think. Literature cultivates the free mind. Writers are truth-tellers. In 1917, Soviet leader Lenin ordered a “Decree on Press” threatening closure of publications critical of the Bolsheviks. Authoritarians know the danger posed by truth. And they are more than willing to use sword and flame to cut it down.

The question is what can we do about it?

“The antidote to authoritarianism is not some form of American authoritarianism,” Cooper Union librarian David K. Berninghausen told the Times in 1952. “The antidote is free inquiry.”

When Robin Hood was threatened by a textbook commissioner in 1953, some Indiana State University students fought back. Five of them gathered chicken feathers, dyed them green, and spread them across campus. Their protest caught on at other colleges, including UCLA, where two hundred students dressed up as Sherwood Forest’s Merry Men for a Green Feather drop. A clever, well-aimed protest, the Green Feather movement broke no windows or legs. Robin Hood was spared.

But those more innocent days are gone. In the internet age, the lines are more sharply drawn, sides set in stone, and the stakes much higher.

That is why dumping some green feathers or wearing an “I READ BANNED BOOKS” t-shirt will not be enough for this moment. If we care, we must take to heart Ike’s advice and “read every book.” We must firmly resolve to read. But buying and reading Maus or Toni Morrison’s Beloved are only the first steps.

We have to make sure that others can read these books. We must be audacious in support of free libraries and vigorously support all teachers who want to encourage students to read, debate, and think for themselves. And we must vigilantly push back on politicians and schoolboards purging libraries of uncomfortable truths. A few loud voices dominating a schoolboard or town hall meeting do not a majority make. To allow a noisy minority to dictate what we read and teach is skating on that thin ice of totalitarian loyalty oaths typical of a Mussolini or Stalin.

On this final note, history is clear. When you have succeeded in marking a writer as “degenerate” or “immoral”—as the Nazis did—you have moved towards dehumanizing them. It is a few short perilous steps from censorship to suppression to a conflagration far worse. In Berlin, on the spot where Nazis threw books into a bonfire, there is a plaque citing German playwright Heinrich Heine’s 1820 words, which read in part: “Where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people as well.”

The road to Hell is lit by burning books.

UPDATE: “Virginia Legal Action Threatens the Freedom to Read” (National Coalition Against Censorship)

“This legal action could profoundly limit the availability of books in the Commonwealth of Virginia. No book has been banned for obscenity in the United States in more than 50 years. Prohibiting the sale of books is a form of censorship that cannot be tolerated under the First Amendment.”

© Copyright 2022 Kenneth C. Davis All rights reserved

July 16, 2022

Who Said It (7-17-2022)

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

President Harry S. Truman (Diary Entry July 17, 1945)

“Promptly a few minutes before twelve I looked up from the desk and there stood Stalin in the doorway. I got to my feet and advanced to meet him. He put out his hand and smiled. I did the same. . . . After the usual polite remarks we got down to business. I told Stalin that I am no diplomat but usually said yes or no to questions after hearing all the argument. It pleased him. I asked him if he had the agenda for the meeting. He said he had and that he had some more questions to present. I told him to fire away. He did and it is dynamite—but I have some dynamite too which I’m not exploding now. . . . I can deal with Stalin. He is honest—but smart as hell.”

(Source: The National Archives)

Stalin and Truman

Source: National Archives, Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer [111-SC-209221-S]

The meeting between Truman and Stalin took place in a suburb of the devastated city of Berlin just before the opening of the Potsdam Conference. Truman, Stalin, and Great Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill, leaders of the three largest Allied nations, were gathered there to discuss the political future of Europe and the conduct of the war still raging in the Pacific.” (Eyewitness: The National Archives)

The day before this meeting, the atomic bomb had been successfully tested in New Mexico. A week later, on July 24, Truman informed Stalin of a “new weapon of unusual destructive force.” Through his network of spies, Stalin already knew about the atomic bomb.

Read my post, “The Month That Changed the World,” a complete account of events in the final days of World War II.

I discuss Truman’s presidency in greater detail in Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents and the post-World War II beginnings of the Cold War in Don’t Know Much About History and The Hidden History of America at War. For more about Stalin read Strongman: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy.

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

July 11, 2022

The Month That Changed The World: July 16-August 15, 1945

[Originally posted in 2020 to mark the 75th Anniversary of the end of World War II and the transformation of the modern world; Revised June 6, 2022]

From the “Trinity” Test to Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Japan’s Surrender:

The Month That Changed the World

Formal surrender aboard USS Missouri Sept. 2. 1945 https://www.history.navy.mil/our-coll...

The following timeline summarizes the extraordinary series of events that helped make the modern world between July 16 and August 15, 1945.

The Atomic Bomb Dome-Hiroshima (Photo Courtesy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered)

On August 6, 1945, the New York Times asked:

“What is this terrible new weapon?”

(New York Times, August 6, 1945: “First Atomic Bomb Dropped on Japan”)

The story followed the announcement made that day by President Harry S. Truman:

“SIXTEEN HOURS AGO an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of T.N.T. It had more than two thousand times the blast power of the British ‘Grand Slam’ which is the largest bomb ever yet used in the history of warfare.”

August 6, 1945

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

(“Statement by the President Announcing the Use of the A-Bomb at Hiroshima”: Truman Library and Museum)

The use of the first atomic bomb followed the successful test detonation –the goal of the wartime Manhattan Project — and the beginning of a series of world-changing events.

• July 16, 1945 the first atomic device, nicknamed “the Gadget,” is detonated in the “Trinity” test at Alamogordo, New Mexico. Read this account of the test in National Geographic.

New York Times reporter Dennis Overbye visited the site in 2021. His report “Touring Trinity, the Birthplace of Nuclear Dread”:

“The detonation created a crater eight feet deep, a half-mile wide and lined with glassy pebbles called trinitite: sand that had been swept up in the fireball, vaporized and then fell back down in molten radioactive droplets.”

The Trinity test, 15 seconds after detonation. Photo courtesy of David Wargowski Source: National Museum of Nuclear Science & History

In the course of the next weeks, the world would be transformed, with the arrival of the Atomic Age, Japan’s surrender, the end of World War II, the charter of the United Nations, and the beginning of the Cold War.

The development, testing, and use of atomic bombs is documented by the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History.

• July 17 In Potsdam, near Berlin in defeated Germany, President Harry S. Truman comes face to face with the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. Truman had taken office upon the death of President Roosevelt on April 12, 1945 without knowledge of the Manhattan Project or the atomic bomb’s existence. Having been told about the potential weapon, Truman is informed of the successful “Trinity” test while meeting Soviet Strongman Stalin with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the European postwar conference.

Harry S. Truman and Joseph Stalin at Potsdam (Public Domain: President Harry S. Truman Library and Museum)

“I told Stalin that I am no diplomat but usually said yes or no to questions after hearing all the argument.”

Read about Stalin’s rise to power in Strongman

Following the New Mexico test success, the components of the atomic bomb are loaded onto the USS Indianapolis in San Francisco for transport to an airbase on Tinian Island in the Pacific. Many of the crew of nearly 1,200 men have no idea what the ship is carrying.

•July 19 In the United States, Congress approves the Bretton Woods agreement, an international pact designed to avoid postwar financial crises like those that followed World War I. The agreement creates the International Money Fund and what later becomes the World Bank.

The Japanese cities of Choshi, Hitachi, Fukui and Okazaki are struck by 600 B-29 Superfortress bombers dropping some 4,000 tons of bombs — the largest employment of the bomber to date.

The USS Indianapolis reaches Pearl Harbor in the first leg of its voyage to deliver the atomic bomb components.

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/515009

• July 21 “A senior US Army Air Force intelligence officer in the Pacific distributed a report declaring: ‘The entire population of Japan is a proper Military Target . . . THERE ARE NO CIVILIANS IN JAPAN.’” Richard B. Frank via World War II Museum.

In Potsdam, Truman and Churchill privately agree to use the atomic bomb if Japan does not surrender. Read about Truman’s decision from the National Park Service Harry S. Truman National Historic Site.

• July 22 In what is described as the last surface battle of World War II, the U.S. Navy sinks Japanese supply ships in the “Battle of Sagami Bay” (“Tokyo Bay”). Naval bombardments of the Japanese mainland continue, along with B-29 bombing raids striking Japanese cities.

In China, the American Far East Air Force attacks Japanese troops, airfields, and shipping near Shanghai.

• July 23 In Potsdam, Secretary of War Henry Stimson receives atomic bomb target list. In order of choice they are: Hiroshima, Kokura, and Niigata. He also receives an estimate of atomic bomb availability: “Little Boy” should be ready for use on Aug. 6, second “Fat Man-type” by Aug. 24. There are plans for a total of seven bombs available by December.

• July 24 Truman informs Stalin of a “new weapon of unusual destructive force.”

“In which I tell Stalin we expect to drop the most powerful explosive ever made on the Japanese. He smiled and said he appreciated my telling him–but he did not know what I was talking about–the Atomic Bomb! HST”

Truman’s note on back of photograph from Potsdam Conference describing his conversation with Stalin about the atomic bomb. Source: Truman Museum https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/photogr...

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

But Stalin already knows about the atomic bomb because of a network of spies inside the Manhattan Project. The Soviet push to capture Berlin in April and May 1945 was motivated in part by Stalin wanting to capture German scientists working on a Nazi atomic bomb and tons of uranium held in a Berlin lab. This episode is recounted in the “Berlin Stories” chapter of my book The Hidden History of America at War.

• July 25 Truman writes in his diary that he has made the decision to use “the most destructive bomb in the history of the world… I have told the Sec. of War, Mr. Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children.”

Sources: Truman Library and Museum National Security Archive, George Washington University

• July 26 British general election returns are announced; Prime Minister Winston Churchill is defeated and replaced by Clement Attlee.

“The landslide victory comes as a major shock to the Conservatives following Mr Churchill’s hugely successful term as Britain’s war-time coalition leader, during which he mobilised and inspired courage in an entire nation.”

U.S. Propaganda poster (Source National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/513563)

–BBC

At the Potsdam Conference, the Potsdam Declaration demands an “Unconditional surrender” by Japan. Issued by Great Britain, China, and the U.S., it threatens:

“The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

The USS Indianapolis reaches Tinian that day.

USS Indianapolis 10 July 1945, after final overhaul and repair of combat damage. Photograph from the Bureau of Ships Collection in the U.S. National Archives (Naval History and Heritage Command https://usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.m...)

“Indianapolis departed San Francisco on 16 July 1945, foregoing her post-repair shakedown period. Touching at Pearl Harbor on 19 July, she raced on unescorted and reached Tinian on 26 July, covering some 5,000 miles from San Francisco in only ten days.”

After delivering the atomic bomb components, the ship departs for Guam and the Philippines.

• July 27 American B-29 SuperFortress bombers drop 600,000 leaflets over eleven Japanese cities warning that they are targets of bombings.

“But, unfortunately, bombs have no eyes. So, in accordance with America’s humanitarian policies, the American Air Force, which does not wish to injure innocent people, now gives you warning to evacuate the cities named and save your lives.” –from a “LeMay Leaflet,” named for General Curtis LeMay, architect of the Pacific bombing campaign (Atomic Heritage Foundation)

In England, Winston Churchill has a final meeting with his joint chiefs of staff.

• July 28 In New York City, an Army B-25 bomber on a routine mission flies into the Empire State Building –then the world’s tallest skyscraper. Three crew members and eleven people in the building are killed.

“B-25 Mitchell bomber smashed beyond recognition into Empire State Building. This is a picture of the wreckage-strewn 79th floor where the bomber tore a 18-foot hole in wall. Propeller is embedded in the wall at the left.” Source: New York Daily News

“I was at the file cabinet and all of a sudden the building felt like it was just going to topple over,” [office worker Gloria] Pall said. “It threw me across the room, and I landed against the wall. People were screaming and looking at each other. We didn’t know what to do. We didn’t know if it was a bomb or what happened. It was terrifying.” Source: National Public Radio

In Potsdam, newly-elected Prime Minister Clement Attlee of the Labour Party arrives to rejoin the talks which are nearly concluded. Attlee led post-war UK until 1951.

“As Prime Minister, he enlarged and improved social services and the public sector in post-war Britain, creating the National Health Service and nationalising major industries and public utilities. Attlee’s government also presided over the decolonisation of India, Pakistan, Burma, Ceylon and Jordan, and saw the creation of the state of Israel upon Britain’s withdrawal from Palestine.” Official UK Biography of Attlee.

• July 29 The Japanese government rejects the Potsdam Declaration surrender demand.

Just after midnight, the Indianapolis is struck by a Japanese torpedo.

• July 30 Torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, the Indianapolis sinks in twelve minutes. Between 800 and 900 of the crew of nearly 1,200 are plunged into the shark-infested waters.

“What followed was an ordeal of hell on earth for those who survived the sinking. For a whole host of reasons, many related to the secrecy of her atom bomb mission, the rest of the Navy did not know that Indianapolis was missing.”

— Sam Cox (Rear Adm., USN, Ret.), “Lest We Forget: USS Indianapolis and her sailors”

–Read “The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis” via the National Archives including a film clip from the classic scene in Jaws in which Captain Quint describes the sinking of the ship and the shark attacks that followed.

• July 31 The assembly of the atomic bomb, code named “Little Boy,” is completed. The final arming of the bomb will be done in-flight.

In Potsdam, Truman is notified of the bomb being ready. He writes a message that concludes:

“Release when ready, but not sooner than August 2. HST”

According to the Truman Library:

The actual reply that President Truman wrote on July 31, 1945 (Photo taken by Dawn Wilson at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library)

“No known written record exists in which Harry Truman explicitly ordered the use of atomic weapons against Japan. The closest thing to such a document is this handwritten order, addressed to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, in which Truman authorized the release of a public statement about the use of the bomb. It was written on July 31, 1945 while Truman was attending the Potsdam Conference in Germany. In effect, this served as final authorization for the employment of the atomic bomb, though the expression ‘release when ready’ refers to the public statement.”

• August 1 The atomic bomb is ready and flight orders are prepared. But weather delays the mission. Of four potential target cities, Hiroshima is chosen as the primary target.

In Potsdam that day, the Big Three wrap up their meetings and discuss plans for the trials of war criminals that later become known as the Nuremberg Trials.

Read my 2021 post on the Nuremberg Trials.

In the Pacific, hundreds of survivors from the Indianapolis desperately try to stay afloat in the shark-infested waters.

“In that clear water you could see the sharks circling. Then every now and then, like lightning, one would come straight up and take a sailor and take him straight down.” – Survivor of the Indianapolis sinking to the BBC.

• August 2

The Big Three at the end of the Potsdam Conference: Front row (Left to Right) Prime Minister Attlee, President Truman, Generalissimo Stalin. Source: Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives.

Shortly after midnight, the Potsdam Conference concludes with a joint communique. It includes reference to the United Nations, whose organization and charter had been completed on June 26 at a conference in San Francisco.

Truman speaks of a future Washington meeting with the Soviet leader, but he and Stalin never meet again.

What was clear was that the Conference had solidified the Soviet Union’s domination over much of Eastern Europe, including the eastern half of a divided Germany. Admiral William D. Leahy, Truman’s Chief of Staff, later wrote:

“The Soviet Union emerged at this time as the unquestioned all-powerful influence in Europe….”

The U.S. Navy is still unaware that the Indianapolis has gone down. More than 800 men went into the water and the survivors are spotted by a reconnaissance plane four days after the sinking.

“Marks’s crew dropped rubber rafts and supplies as they witnessed continuing shark attacks. Disregarding orders not to land at sea, the pilot touched down and began taxiing to pick up survivors.

As darkness set in, and as Marks waited for rescue vessels, he pulled men from the water into his aircraft. When the plane’s fuselage was at maximum capacity, survivors were tied to the wings with parachute cord. The pilot and his crew rescued a total of 56 men. Once signaled, a total of seven Navy ships converged on the site and rescued the remaining men. Only 317 sailors survived.” –National Archives, “The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis”

Indianapolis’ survivors en route to a hospital following their rescue, early August 1945. Source: Naval History and Heritage Command

• August 4 Colonel Paul Tibbets briefs the men of the 509th Composite Group -the weapon delivery arm of the Manhattan Project. Tibbets is the commander of the unit. His men do not know the nature of the bomb they will carry.

• August 5 The bombing mission is confirmed and Colonel Paul Tibbets announces he will pilot the plane which he names “Enola Gay,” after his mother.

Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr., Pilot of the Enola Gay, the Plane that Dropped the Atomic Bomb August 6, 1945 (National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/535737)

• August 6 At 0245 local time on Tinian,

“Enola Gay begins takeoff roll. [Pilot] Colonel Paul Tibbets says to co-pilot Robet Lewis, ‘Let’s go.’ He pushes all of the throttles forward. The overloaded Enola Gay lifts slowly into the night sky, using all of the more than two miles of runway.”

—Atomic Heritage Foundation, minute-by-minute timeline of Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings.

0730:

“Tibbets announces to the crew: ‘We are carrying the world’s first atomic bomb.’ He pressurizes the Enola Gay and begins an ascent to 32,700 feet. The crew puts on their parachutes and flak suits.”

0912: Control of the Enola Gay is handed over to the bombardier, Thomas Ferebee, as the bomb run begins. A Radio Hiroshima operator reports that three planes have been spotted.

0914 (0814 Hiroshima time): Tibbets tells his crew, “On glasses.”

–Atomic Heritage Foundation Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombing Timeline

8:15 AM (Hiroshima local time) The first atomic bomb is detonated over Hiroshima.

“In less than one second, the fireball had expanded to 900 feet. The blast wave shattered windows for a distance of ten miles and was felt as far away as 37 miles. Over two-thirds of Hiroshima’s buildings were demolished. The hundreds of fires, ignited by the thermal pulse, combined to produce a firestorm that had incinerated everything within about 4.4 miles of ground zero.”

Source: Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered.

“In the street, the first thing he saw was a squad of soldiers who had been burrowing into the hillside opposite, making one of the thousands of dugouts in which the Japanese apparently intended to resist invasion, hill by hill, life for life; the soldiers were coming out of the hole, where they should have been safe, and blood was running from their heads, chests, and backs. They were silent and dazed.

Under what seemed to be a local dust cloud, the day grew darker and darker.”

–John Hersey, “Hiroshima,” New Yorker (August 24, 1946)

In Hiroshima, the estimated death toll reaches eighty thousand people killed instantly; as many as 90 percent of the city’s nurses and doctors also die instantly. By 1950, as many as 200,000 die as a result of long-term effects of radiation.

“Historians say General Groves understood the radiation issue as early as 1943 but kept it so compartmentalized that it was poorly known by top American officials, including Harry S. Truman. At the time he authorized the Hiroshima bombing, President Truman, scholars say, knew almost nothing of the bomb’s radiation effects.”

Read: “The Black Reporter Who Exposed a Lie about the Atomic Bomb” New York Times

In his official announcement, President Truman said,

It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.

Read Don’t Know Much About Hiroshima for more details about the bombing and its aftermath.

•August 7 A report to the Japanese Imperial Army General Staff reads:

“The whole city of Hiroshima was destroyed instantly by a single bomb.” (Atomic Heritage Foundation)

On Guam, the decision to use a second device is made and the mission date set for August 10, then moved to August 9 over weather concerns.

Fat Man being lowered and checked on transport dolly for airfield trip Image Source: Heritage Foundation https://www.atomicheritage.org/histor...

•August 8 Fulfilling a pledge Stalin had made earlier at the Yalta conference, the Soviet Union declares war on Japan and invades Manchuria the next day, sending more than one million troops into Japanese-held territory.

The Japanese military leadership was still divided over the surrender demand, with some leading generals vowing to fight to the death. A coup against Emperor Hirohito began to be planned by members of the Japanese military.

A plutonium bomb code named “Fat Man” is prepared on Tinian. It will be carried by a B-29 called “Bockscar.” The primary target is the city of Kokura, home to a large munitions plant.

The crew of the B-29 called “Bockscar” taken after the Nagasaki bombing (Image: U.S. Air Force)

•August 9

0347: Bockscar, piloted by Major Charles Sweeney, lifts off from Tinian Island. The target of choice is Kokura Arsenal.

Clouds and smoke from nearby fires obscure Kokura, so “Fat Man” is dropped over the secondary target, the city of Nagasaki, with a population estimated at 263,000, a city that was home to two Mitsubishi military plants. It is also the site of a prisoner of war camp.

“Nagasaki was a city on the west coast of Kyushu on picturesque Nagasaki Bay. It was famous as the setting for Puccini’s beautiful opera Madame Butterfly. It was also home to two huge Mitsubishi war plants on the Urakami River. This complex was the primary target, but because the city was built in hilly, almost mountainous terrain, it was a much more difficult target than Hiroshima…

Fat Man exploded at 1,840 feet above Nagasaki and approximately 500 feet south of the Mitsubishi Steel and Armament Works with an estimated force of 22,000 tons of TNT.

Unlike Hiroshima, there was no firestorm at Nagasaki. Despite this, the blast was more destructive to the immediate area, due to the topography and the greater power of Fat Man.”

—Hiroshima & Nagasaki Remembered

The death toll in Nagasaki also reaches 80,000 by the end of 1945. Read a full account of this mission in “Nagasaki: The Last Bomb” by Alex Wellerstein (New Yorker, August 7, 2015)

The National Archives “Unwritten Record” blog also offers resources on the atomic bombings.

•August 10 After Nagasaki is bombed, Truman orders no more strikes without his authorization. Another plutonium core for a third weapon is prepared for shipment.

September 24, 1945, 6 weeks after Nagasaki was destroyed by the world’s second atomic bomb attack. Photo by Cpl. Lynn P. Walker, Jr. (USMC) National Archives FILE #: 127-N-136176

Although an unofficial surrender message was sent by a Japanese news agency, the Japanese cabinet was divided and no decision was made. The Emperor would not surrender his sovereignty.

•August 11 The U.S. Secretary of State James Byrnes rejects any conditional surrender and states that the Emperor and Japan’s government will be subject to the Allied Powers and declares that any future Japanese government must reflect the will of the people.

Soviet troops invade South Sakhalin island, Japanese-held territory.

•August 12-13 Soviet troops advance into the Korean peninsula.

Emperor Hirohito agrees to accept the terms of Secretary Byrnes’s note and orders the suspension of military activity. He records a surrender announcement. Military officers began to plot against Hirohito in a coup known as the “Kyujo incident.”

•August 13 The bombing of Japan, including firebombing, resumes with more than 1,000 B-29s taking part.

Japanese officers continue to seek allies in their planned coup against the Imperial government.

Residential section of Tokyo after the March 1945 air raids. (Wikimedia commons http://www.kmine.sakura.ne.jp/kusyu/k...

•August 14 (August 15 in Japan): The military coup fails and several plotters commit suicide.

In an extraordinary address recorded earlier, the Emperor of Japan is heard on the radio for the first time and accepts the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration, agreeing to the unconditional surrender.

Read: “The Emperor’s Speech” by Max Fisher (The Atlantic, August 15, 2012)

At a White House conference, according to United Press International, Truman says:

“This is the day when Fascist and police governments cease to exist in the world. This is the day for democracy.”

-Source: “Japan Surrenders Unconditionally, World At Peace” UPI archives

Truman announces Japan’s surrender to reporters in Oval Office.

Credit: Rowe, Abbie National Park Service Harry S. Truman Library & Museum.

Across America and England, jubilant crowds fill the streets once more for an unofficial V-J (Victory over Japan) Day, as they had three months earlier on VE Day, May 8,1945, after Germany’s surrender ended the war in Europe.

A video clip of Truman’s August 14 announcement from C-Span.

V-J Day Times Square August 14, 1945 Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c19650

•September 2, 1945 A formal surrender ceremony is performed in Tokyo Bay and that date is also referred to as V-J Day.

Almost since the day the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, critics have second-guessed Truman’s decision and motives. A generation of historians and commentators have defended or repudiated the need for unleashing the atomic weapon. Admiral William D. Leahy, who was with Truman at Potsdam, later wrote in a memoir:

Once it had been tested, President Truman faced the decision as to whether to use it. He did not like the idea, but he was persuaded that it would shorten the war against Japan and save American lives. It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan.

–William D. Leahy, I Was There (1950)

In China, however, the Japanese surrender ended the wartime alliance between the Communists and Nationalists. The Chinese civil war began anew, with the US supporting Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Stalin’s USSR backing Mao Zedong’s Communists.

Read about Mao’s rise to power in Strongman: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy.

Many historians contend that preventing death and casualties in an invasion of Japan was only a partial explanation for the use of the two atomic bombs. The United States was already wary of Stalin and his designs on Japan’s wartime territory. They argue that the use of the two devices was meant to end the war quickly to prevent Stalin from capturing territory held by Japan. It may have also been a signal to Stalin and the Soviet Union that the United States possessed these weapons and was willing to use them.

In other words, the dropping of the atomic bombs became the first volley in the Cold War.

READ about the debate in this Smithsonian article.

In 1952, Albert Einstein –whose 1939 letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt had set the Manhattan Project in motion — wrote a brief essay published by a Japanese magazine Kaizo in which he stated:

I was well aware of the dreadful danger for all mankind, if these experiments would succeed. But the probability that the Germans might work on that very problem with good chance of success prompted me to take that step. I did not see any other way out, although I always was a convinced pacifist. To kill in war time, it seems to me, is in no ways better than common murder.

He concluded:

Gandhi, the greatest political genius of our time has shown the way, and has demonstrated the sacrifices man is willing to bring if only he has found the right way. His work for the liberation of India is a living example that man’s will, sustained by an indomitable conviction is stronger than apparently invincible material power.

–Source Hiroshima & Nagasaki Remembered

You can read more about Hiroshima and the dropping of the atomic bombs in Don’t Know Much About History and more about President Truman in Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents and in The Hidden History of America At War. Read more about Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin in STRONGMAN published on October 6, 2020.

Don’t Know Much About® New York’s Bloody Draft Riots

(Originally posted on July 13, 2010; reposted July 11, 2022)

On July 11, 1863, the first Civil War draft lottery took place in New York City.

On July 13, 1863, New York City exploded in a four-day long murderous riot, still considered one of the deadliest urban riots in American history. The cause of the riots–violent opposition to the Civil War draft law.

Since poverty has been our crime,

We bow to the decree.

We are the poor who have no wealth

To purchase liberty.

If your picture of draft dodgers is one of 60s-era hippies shouting “Hell No, We won’t go,” the ditty above offers another vision.

It comes from the Civil War era, when the United States passed its first federal draft, the Enrollment Act, in March 1863. (A Confederate Draft had actually preceded the federal draft by two years.)

Under the rules of the law, there were certain exemptions –telegraph operators and railroad engineers were excused, as were certain government employees.

Then there were the rich. They were different. Under the terms of the Civil War draft, a man could avoid the draft by paying $300 or hiring a substitute. J.P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, and future President Grover Cleveland all did it. So did the wealthy father of Teddy Roosevelt.

The practice led to the complaint that the Civil War was “A rich man’s war, but a poor man’s fight.”