Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 18

September 1, 2022

STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy

An audiobook is available from Penguin Random House

Strongman named among Washington Post Best Children’s and Young Adult Books of 2020 Named to “Best Children’s Books of the Year-2021”

by the Bank Street College of EducationNamed to “Best Young Adult Books of the Year” by Kirkus ReviewsNamed to “Best YA Books of 2020 for Understanding the US Today” Kirkus ReviewsStarred review from Kirkus Reviews: “History’s warnings reverberate in this gripping read about five dictatorial strongmen. A pitch-perfect balance of nuanced reflection and dire warning.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Publishers Weekly: “A fascinating, highly readable portrayal of infamous men that provides urgent lessons for democracy now.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Shelf Awareness: “Kenneth C. Davis…conveys his plentiful knowledge of dictators in this powerful, spine-tingling biographic work that covers five of the world’s most horrifying autocrats. Grounded in thorough research, Strongman expertly explores the fragility of democracy …” Read the full review here

Named to “Best Children’s Books of the Year-2021”

by the Bank Street College of EducationNamed to “Best Young Adult Books of the Year” by Kirkus ReviewsNamed to “Best YA Books of 2020 for Understanding the US Today” Kirkus ReviewsStarred review from Kirkus Reviews: “History’s warnings reverberate in this gripping read about five dictatorial strongmen. A pitch-perfect balance of nuanced reflection and dire warning.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Publishers Weekly: “A fascinating, highly readable portrayal of infamous men that provides urgent lessons for democracy now.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Shelf Awareness: “Kenneth C. Davis…conveys his plentiful knowledge of dictators in this powerful, spine-tingling biographic work that covers five of the world’s most horrifying autocrats. Grounded in thorough research, Strongman expertly explores the fragility of democracy …” Read the full review here•2021 YALSA Nonfiction Award nominee

A review in Booklist says, “Davis does not sugarcoat his material, inviting long thoughts with his assertion that this is a decidedly human story that points to real people as evidence that evil exists in this troubled world.”

In addition to telling how these men took unlimited power, brought one-party rule to their nations, and were responsible for the deaths of millions of people, the book offers a brief history of Democracy and discusses the present threat to democratic institutions around the world.

In a time when Democracy is under assault across the globe, it is more important than ever to understand how a Strongman takes power and how quickly democracy can vanish –even as millions cheer its death.

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR STRONGMAN

“I found myself engrossed in it from beginning to end. I could not help admiring Davis’s ability to explain complex ideas in readable prose that never once discounted the intelligence of young readers. It is very much a book for our time.”

—Sam Wineburg, Margaret Jacks Professor of Education & History, Stanford University, author of Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone).

“Strongman is a book that is both deeply researched and deeply felt, both an alarming warning and a galvanizing call to action, both daunting and necessary to read and discuss.”

—Cynthia Levinson, author of Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws That Affect Us Today

“A wake-up call to democracies like ours: we are not immune to despots . . . Strongman demonstrates that democracy is not permanent, unless it is collectively upheld. This book shakes that immortality narrative.”

—Jessica Ellison, President of the Minnesota Council for the Social Studies; Teacher Education Specialist, Minnesota Historical Society

Rarely does a history book take such an unflinching look at our common future, where the very presence of democracy is less than certain; even rarer is a history book in which the author’s moral convictions incite young readers to civic engagement; rarest of all, a history book as urgent, as impassioned, and as timely as Kenneth C. Davis’ Strongman.

—Eugene Yelchin, author of the Newbery Honor book Breaking Stalin’s Nose.

August 29, 2022

Labor Day 2022

“Labor is the superior of capital and deserves much the higher consideration.”— Abraham Lincoln, “First Annual Message to Congress” (December 3, 1861)

To most Americans, the first Monday in September means a three-day weekend and the last hurrah of summer, a final outing at the shore before school begins, a family picnic. The federal Labor Day was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland during his second term in 1894.

With the enormous stresses placed on working people with the Covid pandemic now in its third year, lives have been altered with no end in sight. Work –labor– in America has been transformed.

“Americans worked less last year on average, but that was because mass layoffs in the spring meant fewer people were working at all. Among those who kept their jobs, there was little change in the amount of time spent working in a given day — about seven and a half hours in 2020, the same as in 2019.”

–“The Pandemic Changed How We Spend Our Time” New York Times (July 27, 2021)

And as Nobel Prize-winning New York Times columnist Paul Krugman wrote in August 2021:

“And workers are, it seems, willing to pay a price to avoid going back to the way things were. This may, by the way, be especially true for older workers, some of whom seem to have dropped out of the labor force.”

–“Workers Don’t Want Their Old Jobs on the Old Terms”

But as workers have begun on a grassroots level to organize unions at such places as REI, Trader Joe’s, Starbucks, Amazon warehouses, and a LA topless bar, Labor suddenly has more muscle. As we rethink work and life, it is a most fitting moment to consider how we labor and the history of Labor Day.

The holiday was born at the end of the nineteenth century, in a time when work was no picnic. As America was moving from farms to factories in the Industrial Age, there was a long, violent, often-deadly struggle for fundamental workers’ rights, a struggle that in many ways was America’s “other civil war.” (From “The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day”)

“Glassworks. Midnight. Location: Indiana.” From a series of photographs of child labor at glass and bottle factories in the United States by Lewis W. Hine, for the National Child Labor Committee, New York.

The first American Labor Day is dated to a parade organized by unions in New York City on September 5, 1882, as a celebration of “the strength and spirit of the American worker.” They wanted among, other things, an end to child labor.

In 1861, Lincoln told Congress:

Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights. Nor is it denied that there is, and probably always will be, a relation between labor and capital producing mutual benefits. The error is in assuming that the whole labor of community exists within that relation.

Today, in postindustrial America, Abraham Lincoln’s words ring empty. Labor is far from “superior to capital.” Working people and unions have borne the brunt of the great changes in the globalized economy.

But the facts are clear: In the current “gig economy,” the loss of union jobs and the recent failures of labor to organize workers is one key reason for the decline of America’s middle class.

Read the full history of Labor Day in this essay: “The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day” (2011)

Why Labor Day? Check out this Ted-Ed animated video

“Why do Americans and Canadians Celebrate Labor Day?”

This Ted-Ed animated video explains the history of the holiday is a few years old. But it still matters today. (Reposted from 9/1/2014)

You can also view it on YouTube:

You can read more about the history and meaning of Labor Day in this piece I wrote for CNN a few years ago:

“The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day”

Read more about the period of labor unrest in Don’t Know Much About® History.

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

Who Said It? (Labor Day edition)

(Reposted from 2014)

Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration.

Abraham Lincoln (November 1863) Photo by Alexander Gardner

Abraham Lincoln, “First Annual Message to Congress” (“State of the Union”) December 3, 1861

It is not needed nor fitting here that a general argument should be made in favor of popular institutions, but there is one point, with its connections, not so hackneyed as most others, to which I ask a brief attention. It is the effort to place capital on an equal footing with, if not above, labor in the structure of government. It is assumed that labor is available only in connection with capital; that nobody labors unless somebody else, owning capital, somehow by the use of it induces him to labor. This assumed, it is next considered whether it is best that capital shall hire laborers, and thus induce them to work by their own consent, or buy them and drive them to it without their consent. Having proceeded so far, it is naturally concluded that all laborers are either hired laborers or what we call slaves. And further, it is assumed that whoever is once a hired laborer is fixed in that condition for life.

Now there is no such relation between capital and labor as assumed, nor is there any such thing as a free man being fixed for life in the condition of a hired laborer. Both these assumptions are false, and all inferences from them are groundless.

Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights.

Source and Complete text: Abraham Lincoln: “First Annual Message,” Read more about Lincoln, his life and administration and the Civil War in Don’t Know Much About® History, Don’t Know Much About® the Civil Warand Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

And read about the history of Labor Day in this post.

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

August 26, 2022

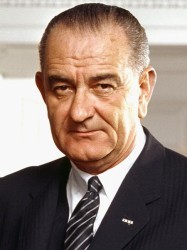

Don’t Know Much About® Lyndon B. Johnson

(Revise of 2013 essay)

Lyndon B. Johnson (March 1964)

(Photo: Arnold Newman, White House Press Office)

All I have I would have given gladly not to be standing here today.

Lyndon B. Johnson, in his first address as President to a joint session of Congress (November 27, 1963)

The 36th President, Lyndon B. Johnson, was born on August 27, 1908, in a small farmhouse near Stonewall, Texas on the Pedernales River. Coincidentally, it is also the date on which LBJ accepted the 1964 Democratic nomination for President. (Senator Hubert H. Humphrey was his Vice Presidential nominee.)

In some respects, history and time have been kinder to Lyndon B. Johnson than his tortured Presidency –and certainly the critics of his day—would have possibly suggested. A power broker extraordinaire during his days in Congress, especially during his twelve years in the Senate, Lyndon B. Johnson challenged John F. Kennedy for the Democratic nomination in the 1960 primaries, and then accepted Kennedy’s offer to become his Vice Presidential running mate. Johnson was credited with helping Kennedy win Southern votes and ultimately the election.

Lyndon B. Johnson taking the oath of office aboard Air Force One at Love Field Airport two hours and eight minutes after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Dallas, Texas. Jackie Kennedy (right), still in her blood-soaked clothes, looks on. Public Domain-Source White House

On November 22, 1963, history and America changed with Kennedy’s assassination. Johnson became President, taking the oath of office aboard Air Force One with Jacqueline Kennedy, the dead President’s widow standing beside him.

Driven by a rousing sense of social justice, born out of his youth and upbringing in hardscrabble Texas and Depression-era experiences, he had become one of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s most loyal New Dealers. First in a federal job, then in Congress and later as “Master of the Senate.” As President, Johnson set the country on a quest for what he called the “Great Society,” looking for ways to end the great economic injustice and bitter racial disparity that existed in America in 1963. But his vision for a “Great Society” was counterbalanced, and ultimately overshadowed by his doomed course in pursuing the war in Vietnam.

In the midst of the war, recently released White House tapes reveal Johnson confided–

I can’t win and I can’t get out.

Fast Facts-

•Johnson was the first Congressman to enlist for duty after Pearl Harbor.

Lyndon B. Johnson as Navy Commander (Photo Credit: Lyndon B. Johnson Library and Museum)

•Johnson was the fourth president to come into office upon the death of a president by assassination. (The others were Andrew Johnson after Lincoln, Chester A. Arthur after Garfield, and Theodore Roosevelt after McKinley.)

•Johnson appointed the first black Supreme Curt Justice, Thurgood Marshall.

The Johnson Library and Museum is in Austin, Texas. Lyndon B. Johnson died at the age of 67 on January 22, 1973.

Resources on Johnson from the Library of Congress

Read more about Lyndon B. Johnson, his presidency and the Vietnam War and civil rights movement in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents and Don’t Know Much About® History.

His Vietnam legacy is discussed in the Tet Chapter of The Hidden History of America at War.

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

August 23, 2022

STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy

An audiobook is available from Penguin Random House

Strongman named among Washington Post Best Children’s and Young Adult Books of 2020 Named to “Best Children’s Books of the Year-2021”

by the Bank Street College of EducationNamed to “Best Young Adult Books of the Year” by Kirkus ReviewsNamed to “Best YA Books of 2020 for Understanding the US Today” Kirkus ReviewsStarred review from Kirkus Reviews: “History’s warnings reverberate in this gripping read about five dictatorial strongmen. A pitch-perfect balance of nuanced reflection and dire warning.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Publishers Weekly: “A fascinating, highly readable portrayal of infamous men that provides urgent lessons for democracy now.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Shelf Awareness: “Kenneth C. Davis…conveys his plentiful knowledge of dictators in this powerful, spine-tingling biographic work that covers five of the world’s most horrifying autocrats. Grounded in thorough research, Strongman expertly explores the fragility of democracy …” Read the full review here

Named to “Best Children’s Books of the Year-2021”

by the Bank Street College of EducationNamed to “Best Young Adult Books of the Year” by Kirkus ReviewsNamed to “Best YA Books of 2020 for Understanding the US Today” Kirkus ReviewsStarred review from Kirkus Reviews: “History’s warnings reverberate in this gripping read about five dictatorial strongmen. A pitch-perfect balance of nuanced reflection and dire warning.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Publishers Weekly: “A fascinating, highly readable portrayal of infamous men that provides urgent lessons for democracy now.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Shelf Awareness: “Kenneth C. Davis…conveys his plentiful knowledge of dictators in this powerful, spine-tingling biographic work that covers five of the world’s most horrifying autocrats. Grounded in thorough research, Strongman expertly explores the fragility of democracy …” Read the full review here•2021 YALSA Nonfiction Award nominee

A review in Booklist says, “Davis does not sugarcoat his material, inviting long thoughts with his assertion that this is a decidedly human story that points to real people as evidence that evil exists in this troubled world.”

In addition to telling how these men took unlimited power, brought one-party rule to their nations, and were responsible for the deaths of millions of people, the book offers a brief history of Democracy and discusses the present threat to democratic institutions around the world.

In a time when Democracy is under assault across the globe, it is more important than ever to understand how a Strongman takes power and how quickly democracy can vanish –even as millions cheer its death.

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR STRONGMAN

“I found myself engrossed in it from beginning to end. I could not help admiring Davis’s ability to explain complex ideas in readable prose that never once discounted the intelligence of young readers. It is very much a book for our time.”

—Sam Wineburg, Margaret Jacks Professor of Education & History, Stanford University, author of Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone).

“Strongman is a book that is both deeply researched and deeply felt, both an alarming warning and a galvanizing call to action, both daunting and necessary to read and discuss.”

—Cynthia Levinson, author of Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws That Affect Us Today

“A wake-up call to democracies like ours: we are not immune to despots . . . Strongman demonstrates that democracy is not permanent, unless it is collectively upheld. This book shakes that immortality narrative.”

—Jessica Ellison, President of the Minnesota Council for the Social Studies; Teacher Education Specialist, Minnesota Historical Society

Rarely does a history book take such an unflinching look at our common future, where the very presence of democracy is less than certain; even rarer is a history book in which the author’s moral convictions incite young readers to civic engagement; rarest of all, a history book as urgent, as impassioned, and as timely as Kenneth C. Davis’ Strongman.

—Eugene Yelchin, author of the Newbery Honor book Breaking Stalin’s Nose.

August 20, 2022

Whose History Is It?

(Originally posted July 13, 2020; revised and reposted August 20, 2022)

“The first documented arrival of Africans to the colony of Virginia was recorded by John Rolfe: About the latter end of August, a Dutch man of Warr of the burden of a 160 tunes arrived at Point-Comfort, the Comandors name Capt Jope, his Pilott for the West Indies one Mr Marmaduke an Englishman. … He brought not any thing but 20. and odd Negroes, w[hich] the Governo[r] and Cape Merchant bought for victuall[s].’ “

–National Parks Service, Historic Jamestown, “African Americans at Jamestown”

Whose history it is? And who gets to shape the narrative?

This is the hottest of hot potato questions, currently dominating the conversation about which dates we mark on the national calendar, whose statues we honor while others are pulled from their pedestals, and how we teach America’s past in our schools,

The comfortable, traditional American history so many Americans were once taught –sort of – has come down for centuries as a bedtime story. It is complete with a happy ending, a rousing tableau for a school pageant, or an instructive morality tale. Columbus’s first voyage and Washington’s cherry tree being Exhibits A and B.

Or it was the exclusive property of one powerful group that wanted to venerate its particular vision of pride. That was the reassuring tale of the first Thanksgiving Happy Meal, or Puritans arriving to establish a “shining city on a hill,” leaving out the indigenous and the dissidents –Roger Williams, Anne Hutchinson, Quakers, and Catholics—who were unwelcome on that hill.

The conflict between that traditional telling of history as American Exceptionalism and a so-called “revisionist” version is boiling over in the wake of the former president’s discordantly curdled speech at Mount Rushmore on the eve of Independence Day in 2020.

“Our nation is witnessing a merciless campaign to wipe out our history, defame our heroes, erase our values and indoctrinate our children…” (New York Times, July 3, 2020)

Back in 1790, John Adams, who was present at the creation, offered a gloomy prediction of how the story would be told.

“The history of our Revolution will be one continued lie from one end to the other,” he wrote fellow Declaration signer Benjamin Rush. “The essence of the whole will be that Dr. Franklin’s electrical rod smote the earth and out sprang General Washington…. thenceforward these two conducted all the policies, negotiations, legislatures and the war.”

Adams was right. From the beginning, American history became a national myth. Controlling that narrative is a powerful tool. As Winston Churchill once remarked,

“History will bear me out, particularly as I shall write history myself.”

How we tell history and then drape it over national holidays or erect monuments to a selective account has always been subject to somebody’s agenda. Winners write history –usually. They tailored the story that became the national narrative, or the myth, depending on your perspective. But for the United States that proud, patriotic portrait came at the cost of the whole truth. And it left far too many people out of the picture.

The history widely celebrated on the Glorious Fourth rightly hailed a document that secured the timeless verities of “All men are created equal” and that all are entitled to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

In crafting that laudable lesson, however, some inconvenient truths were swept into history’s dustbin. When it comes to Independence Day, that meant concealing America’s Great Contradiction – that a nation “conceived in liberty” was also born in shackles.

READ my essay “The American Contradiction” Social Education, March/April 2020

In the current moment of reckoning, there is another agenda. We now acknowledge the purchase of captive Africans in Jamestown in 1619. The Mount Vernon plantation dedicated to honoring the first president now openly confronts the fact that Washington had enslaved more than 300 people at Mount Vernon at his death in 1799. Similarly, Jefferson’s Monticello no longer conceals that the author of the Declaration enslaved people, including his own offspring, born of an enslaved woman.

That history is messy. And the true beauty of American history is that it is not a tale that can be told in simple terms. It is complicated and nuanced. There are few neat answers which fit in a bubble on a standardized test form.

For instance, it is pointless to teach how Washington won the Battle of Yorktown in October 1781 without acknowledging that his first order of business after the surrender was to return thousands of enslaved people who had sought refuge with the British –including those from his Mount Vernon and Jefferson’s Monticello.

It’s absurd to teach a “melting pot” myth and a “religious freedom” narrative without talking about the deep vein of dominant anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiments in America’s past that produced such moments as Philadelphia’s 1844 “Bible Riots,” a deadly sectarian battle begun over which version of the Bible was used in public schools.

Those are also American history “facts.” And as John Adams also famously said,

“Facts are stubborn things…whatever may be our wishes and inclinations or the dictums of our passions…”

Adams said that as he was defending the “bad guys” –the British soldiers who shot at some Boston townies in what became heralded as the Boston Massacre. It is a reminder that America’s rebellion began with an assault on authority. Some snowballs and stones were chucked at those British soldiers. That was followed by act of vandalism and property destruction, now hailed as the Boston Tea Party. And then some rebels tore down a statue—that of King George III, in New York City on July 9, 1776. This is all hailed in the “winner’s history” so many have been taught for so long.

And those are extremely important American history lessons. The rock-throwers, the tea party vandals, and the riotous statue-topplers of the American Revolution were part of the unruly mob that sometimes changes history.

History doesn’t trickle down from the top. Most of the great social movements in this nation’s history came instead from the bottom up. Independence, abolition, suffrage, civil rights, and marriage equality were largely fashioned by those who demonstrated a clear disregard for the law, with the nation’s “leaders” being dragged, kicking and screaming all the way to the finish line.

This is a hard, uncomfortable lesson for some. But in that fact lies the essence of American Exceptionalism.

Letter to Benjamin Rush, April 4, 1790.

“In the Churchill Museum,” Timothy Garton Ash, New York Review of Books, 7 May 1987 also cited in Leonard Roy Frank Quotationary, p. 359.

August 16, 2022

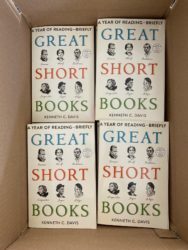

GREAT SHORT BOOKS: A Year of Reading–Briefly

Bound galleys of Great Short Books have arrived!

COMING FROM SCRIBNER BOOKS

NOVEMBER 22, 2022

GREAT SHORT BOOKS:

A YEAR OF READING — BRIEFLY

FIRST TRADE REVIEWS FROM KIRKUS, PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

“An entertaining journey with a fun, knowledgeable guide…. His love of books and reading shines through. From 1759 (Candide) to 2019 (The Nickel Boys), he’s got you covered.” –Kirkus Reviews

Full KIRKUS review here

“Davis’s conversational tone makes him a great guide to these literary aperitifs. This is sure to leave book lovers with something new to add to their lists.” FULL PUBLISHERS WEEKLY REVIEW here

Available for pre-order from Scribner/Simon & Schuster

During the lock-down, I swapped doom-scrolling for the insight and inspiration that come from reading great fiction. Inspired by Boccaccio’s “The Decameron” and its brief tales told during a pandemic, I read 58 great short novels –not as an escape but an antidote.

“A short novel is like a great first date. It can be extremely pleasant, even exciting, and memorable. Ideally, you leave wanting more. It can lead to greater possibilities. But there is no long-term commitment.”

–From “Notes of a Common Reader,” the Introduction to Great Short Books

The result is a compendium that goes from “Candide” to Colson Whitehead, and Edith Wharton to Leila Slimani. And yes, Maus and many other Banned Books and Writers.

Voltaire in Great Short Books

Art © Sam Kerr

Edith Wharton in Great Short Books

Art © Sam Kerr

Advance Praise for Great Short Books: A Year of Reading—Briefly

“GREAT SHORT BOOKS is a fascinating, thoughtful, and inspiring guide to a marvelous form of literature: the short novel. You can dip into this book anywhere you like, but I found myself reading it cover-to-cover, delighting in discovering new works while also revisiting many of my favorites. GREAT SHORT BOOKS is itself a great book—for those who are over-scheduled but want to expand their reading and for those who will simply delight in spending time with a passionate fellow reader who on every page reminds us why we need and love to read.”

–Will Schwalbe, New York Times bestselling author of THE END OF YOUR LIFE BOOK CLUB

“This is the book that you didn’t know you really needed. I began digging into this book as soon as I got it, and it was such a delight to read beautiful prose, just a sip at a time, with Kenneth Davis’ notes to give me context and help me more fully appreciate the stories. Keep this book near your bed or on your coffee table. It will be read and loved.”

–Celeste Headlee, journalist and author of WE NEED TO TALK and SPEAKING OF RACE

A Year of Reading–Briefly

From hard-boiled fiction to magical realism, the 18th century to the present day, Great Short Books spans genres, cultures, countries, and time to present a diverse selection of acclaimed and canonical novels—plus a few bestsellers.

Like browsing in your favorite bookstore, this eclectic compendium is a fun and practical book for any passionate reader hoping to broaden their collection—or anyone who is looking for an entertaining, effortless reentry into reading.

More early reviews from readers at NetGalley.com

“GREAT SHORT BOOKS is a wonderful, breezy but deep look at the outstanding short books of the last 150 years. Kenneth C. Davis is a genius at summarizing each book and making the reader want to read said book post haste. This is a book I didn’t know the world needed but the world did.” –Tom O., reviewer

“…an incredibly valuable tool for book clubs and readers everywhere! Some authors/titles are well-known and others will be new discoveries….HIGHLY RECOMMENDED for any book group looking to find new titles or any reader who wants to know what to read next.” –Ann H. reviewer

“I found over a dozen new authors or titles I want to now read that were included in his main list, and the Further Reading at the end of each chapter and at the end of the volume itself.

As others have suggested, this is a great tool for Book Clubs!

Not Lit Crit, it is mostly focused on necessary, just-the-facts-mam information on one person’s reading of short books over a year. Well worth a read, and great for browsing!” –Stephen B., Librarian

“What better way to introduce new readers to more than 50 ‘short’ books. This handy book is full of non-spoiler descriptions and cultural context that situate these stories within our world.” –Kelsey W., librarian

S0urce: Great Short Books via NetGalley

I can’t wait to start talking about this book with readers everywhere.

Teachers, Librarians, Book Clubs and Other Learning Communities:

Invite me for a visit to your school, classroom, library, historical group, book club or conference.

August 6, 2022

Don’t Know Much About® Hiroshima

Originally posted on August 6, 2020; updated August 6, 2022]

On August 6, 1945, the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. At 8:15 local time, the first atomic bomb was detonated 1,986 feet above the city.

The atomic bomb cloud over Hiroshima Source: National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/542192

Hiroshima before the war was the seventh largest city in Japan, with a population of over 340,000, and was the principal administrative and commercial center of the southwestern part of the country. As the headquarters of the Second Army and of the Chugoku Regional Army, it was one of the most important military command stations in Japan, the site of one of the largest military supply depots, and the foremost military shipping point for both troops and supplies.

-Source: U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, June 1946

Shortly afterwards, the White House released a statement from President Harry S. Truman that had been drafted while he was attending the Potsdam Conference. Truman called Hiroshima “an important Japanese army base.”

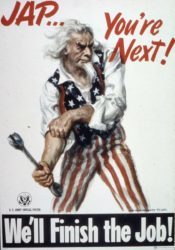

We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories, and their communications. Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan’s power to make war.

It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.

Read: The Month That Changed the World for a timeline of events leading up to the end of World War II.

By June 1, Truman had apparently made his decision to use the atomic bomb to end the war with Japan. But the bomb had not yet been tested. Once the bomb had been successfully detonated in the New Mexico desert, the decision to use it moved forward, a fateful choice that was set against the recent American experience on Okinawa, where more than 12,500 Americans and more than 100,000 Japanese had died in brutal combat.

When the Japanese said they would fight to the death rather than make an unconditional surrender, the final decision was cast. Winston Churchill later summarized the decision: “To avert a vast, indefinite butchery.”

-From Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents

After the war, a United States survey team assessed the impact of the Hiroshima bomb.

“Practically the entire densely or moderately built-up portion of the city was leveled by blast and swept by fire. A ‘fire-storm’, a phenomenon which has occurred infrequently in other conflagrations, developed in Hiroshima: fires springing up almost simultaneously over the wide flat area around the center of the city drew in air from all directions. The inrush of air easily overcame the natural ground wind, which had a maximum velocity of 30 to 40 miles per hour two to three hours after the explosion. The ‘fire-wind’ and the symmetry of the built-up center of the city gave a roughly circular shape to the 4.4 square miles which were almost completely burned out.

The surprise, the collapse of many buildings, and the conflagration contributed to an unprecedented casualty rate. Seventy to eighty thousand people were killed, or missing and presumed dead, and an equal number were injured. (Emphasis added)

—Source: U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, June 1946

What history has confirmed is that some of the men who created the bomb didn’t understand how horrifying its capabilities were. Of course, they understood the destructive power of the bomb, but radiation’s dangers were far less understood. As author Peter Wyden tells it in Day One, an account of the making and dropping of the bomb, scientists involved in creating what they called “the gadget” believed that anyone who might be killed by radiation would die from falling bricks first.

“The survivors, known as hibakusha, sought relief from their injuries. However, 90 percent of all medical personnel were killed or disabled, and the remaining medical supplies quickly ran out. Many survivors began to notice the effects of exposure to the bomb’s radiation. Their symptoms ranged from nausea, bleeding and loss of hair, to death. Flash burns, a susceptibility to leukemia, cataracts and malignant tumors were some of the other effects.

–“The Story of Hiroshima,” Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered

The heat was tremendous . And I felt like my body was burning all over. For my burning body the cold water of the river was as precious as the treasure. Then I left the river, and I walked along the railroad tracks in the direction of my home. On the way, I ran into an another friend of mine, Tokujiro Hatta. I wondered why the soles of his feet were badly burnt. It was unthinkable to get burned there. But it was undeniable fact the soles were peeling and red muscle was exposed.

—Mr. Akihiro Takahashi, who was 14 years old, when the bomb was dropped

On August 9, a second bomb, code named Fat Man, was detonated above Nagasaki.

Like Hiroshima, the immediate aftermath in Nagasaki was a nightmare. More than forty percent of the city was destroyed. Major hospitals had been utterly flattened and care for the injured was impossible. Schools, churches, and homes had simply disappeared. Transportation was impossible.

—Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered

Many historians contend that preventing death and casualties in an invasion of Japan was only a partial explanation for the use of the two atomic bombs. The United States was already wary of Stalin and his designs on Japan’s wartime territory. They argue that the use of the two devices was meant to end the war quickly to prevent Stalin from capturing territory held by Japan. It may have also been a signal to Stalin and the Soviet Union –which had declared war on Japan and moved troops into Manchuria– that the United States possessed these weapons and was willing to use them.

In other words, the dropping of the atomic bombs became the first volley in the Cold War.

August 6 and 9 should not be days to argue about the politics of the bomb. They should be days of solemn remembrance of the victims. And of contemplating the horrific power of the weapons we create.

The City of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and Museum offers an English language website with a history of Hiroshima and the effects of the bombing.

Photo of what became later Hiroshima Peace Memorial among the ruins of buildings in Hiroshima, in early October, 1945, photo by Shigeo Hayashi. (Source Wikimedia Commons)

In 1939, physicist Albert Einstein had written a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt that resulted in the creation of the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb. In 1948, Einstein was quoted by an interviewer as saying:

If I had foreseen Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I would have torn up my formula in 1905.

-Quoted in Einstein and the Poet : In Search of the Cosmic Man (1983) by William Hermanns

In 2016, President Barack Obama became the first sitting U.S. President to visit Hiroshima.

August 5, 2022

Who Said It? (8/5/2020)

“I deem this reply a full acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration which specifies the unconditional surrender of Japan. In the reply there is no qualification.”

–President Harry S. Truman, August 14, 1945 (Source: Harry S. Truman Library and Museum)

After the official statement announcing the surrender of Japan, made at 7 pm ET, Truman added:

“This is the day when Fascist and police governments cease to exist in the world. This is the day for democracy.”

“Japan Surrenders Unconditionally, World At Peace”

Truman announces Japan’s surrender to reporters in Oval Office.

Credit: Rowe, Abbie

National Park Service

Harry S. Truman Library & Museum.

For more on these events, see my post: “The Month That Changed the World”