Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 28

July 29, 2021

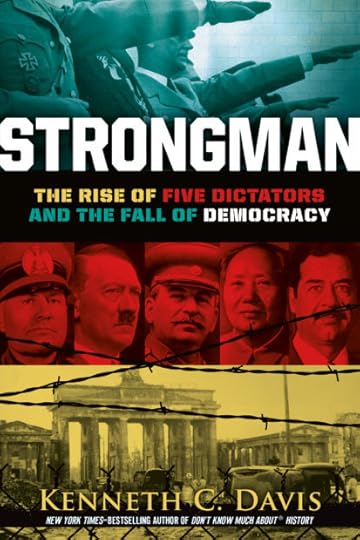

STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy

Born on July 29, 1883 in Predappio Italy: Benito Mussolini– Fascist dictator and wartime ally of Adolf Hitler

“Julius Caesar entered Rome in a blaze of glory, in a chariot, leading his loyal Roman legion. Benito Mussolini arrived in a sleeper compartment on an overnight train.”

–From Strongman, excerpted in October 2020 Social Education magazine

STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy published on October 6, 2020

Order the hardcover and e-book from Holt Books

An audiobook is available from Penguin Random House

A pitch-perfect balance of nuanced reflection and dire warning.”

Starred Review from Publishers Weekly “A fascinating, highly readable portrayal of infamous men that provides urgent lessons for democracy now.”Read the full review hereStarred Review from Shelf Awareness “Kenneth C. Davis…conveys his plentiful knowledge of dictators in this powerful, spine-tingling biographic work that covers five of the world’s most horrifying autocrats. Grounded in thorough research, Strongman expertly explores the fragility of democracy …”Read the full review here•2021 YALSA Nonfiction Award nomineeSTRONGMAN tells the story of the rise to power of five of the most deadly dictators of the 20th century — Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Saddam Hussein.

A review in Booklist says, “Davis does not sugarcoat his material, inviting long thoughts with his assertion that this is a decidedly human story that points to real people as evidence that evil exists in this troubled world.”

In addition to telling how these men took unlimited power, brought one-party rule to their nations, and were responsible for the deaths of millions of people, the book offers a brief history of Democracy and discusses the present threat to democratic institutions around the world.

In a time when Democracy is under assault across the globe, it is more important than ever to understand how a Strongman takes power and how quickly democracy can vanish –even as millions cheer its death.

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR STRONGMAN

“I found myself engrossed in it from beginning to end. I could not help admiring Davis’s ability to explain complex ideas in readable prose that never once discounted the intelligence of young readers. It is very much a book for our time.”

—Sam Wineburg, Margaret Jacks Professor of Education & History, Stanford University, author of Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone).

“Strongman is a book that is both deeply researched and deeply felt, both an alarming warning and a galvanizing call to action, both daunting and necessary to read and discuss.”

—Cynthia Levinson, author of Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws That Affect Us Today

“A wake-up call to democracies like ours: we are not immune to despots . . . Strongman demonstrates that democracy is not permanent, unless it is collectively upheld. This book shakes that immortality narrative.”

—Jessica Ellison, President of the Minnesota Council for the Social Studies; Teacher Education Specialist, Minnesota Historical Society

Rarely does a history book take such an unflinching look at our common future, where the very presence of democracy is less than certain; even rarer is a history book in which the author’s moral convictions incite young readers to civic engagement; rarest of all, a history book as urgent, as impassioned, and as timely as Kenneth C. Davis’ Strongman.

—Eugene Yelchin, author of the Newbery Honor book Breaking Stalin’s Nose.

July 27, 2021

“Two Societies, One Black, One White”

(Revised post 7/27/2021; originally published on February 29, 2016)

As Congress convenes an investigation into the insurrectionist events of January 6, 2021 and the “Capital Riot,” it is useful to remember what President Lyndon B. Johnson said when he announced another formal investigation of rioting in 1967:

–What happened?

–Why did it happen?

–What can be done to prevent it from happening again and again?

-President Lyndon B. Johnson in announcing the formation of a commission to investigate urban violence in 1967.

Once again, it is necessary to revisit the Kerner Commission, formed fifty-four years ago to address violence in American cities.

On July 27, 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson established an 11-member National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. He was responding to a series of violent outbursts in predominantly Black urban neighborhoods in such cities as Detroit and Newark.

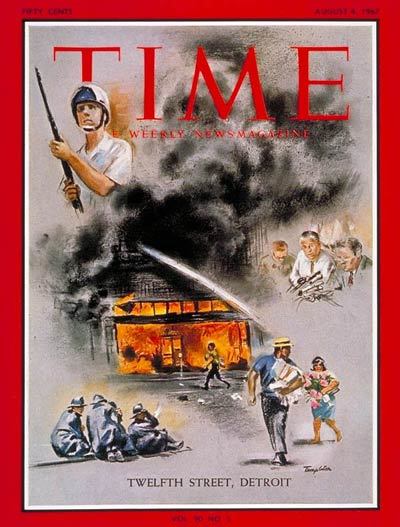

Time Magazine cover August 4, 1967

On July 29, 1967, President Johnson made remarks about the reasons for the commission:

The civil peace has been shattered in a number of cities. The American people are deeply disturbed. They are baffled and dismayed by the wholesale looting and violence that has occurred both in small towns and in great metropolitan centers.

No society can tolerate massive violence, any more than a body can tolerate massive disease. And we in America shall not tolerate it.

But just saying that does not solve the problem. We need to know the answers, I think, to three basic questions about these riots:

–What happened?

–Why did it happen?

–What can be done to prevent it from happening again and again?

Source:Lyndon B. Johnson: “Remarks Upon Signing Order Establishing the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders.,” July 29, 1967. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

On Feb. 29, 1968, President Johnson’s National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, later known as the Kerner Commission after its chairman, Governor Otto Kerner, Jr. of Illinois, issued a stark warning:

“Our Nation Is Moving Toward Two Societies, One Black, One White—Separate and Unequal”

Governor of Illinois Otto Kerner, Jr., meeting with Roy Wilkins (left) and President Lyndon Johnson (right) in the White House. 29 July 1967 Source LBJ Presidential Library

The Committee Report went on to identify a set of “deeply held grievances” that it believed had led to the violence.

Although almost all cities had some sort of formal grievance mechanism for handling citizen complaints, this typically was regarded by Negroes as ineffective and was generally ignored.

Although specific grievances varied from city to city, at least 12 deeply held grievances can be identified and ranked into three levels of relative intensity:

First Level of Intensity

1. Police practices

2. Unemployment and underemployment

3. Inadequate housing

Second Level of Intensity

4. Inadequate education

5. Poor recreation facilities and programs

6. Ineffectiveness of the political structure and grievance mechanisms.

Third Level of Intensity

7. Disrespectful white attitudes

8. Discriminatory administration of justice

9. Inadequacy of federal programs

10. Inadequacy of municipal services

11. Discriminatory consumer and credit practices

12. Inadequate welfare programs

Source: “Our Nation is Moving Toward Two Societies, One Black, One White—Separate and Unequal”: Excerpts from the Kerner Report; American Social History Project / Center for Media and Learning (Graduate Center, CUNY)

and the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (George Mason University).

Issued half a century ago, the list of grievances reads as if it could have been written today.

July 26, 2021

Don’t Know Much About Executive Orders 9980 and 9981

[Repost; originally posted 7/26/2013; revised 7/26/2021]

When Lloyd Austin III, a retired general, was confirmed by the Senate as defense secretary in January 2021, he became the the first Black Pentagon chief.

This historic landmark is a reminder that on July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman issued two Executive Orders that ended official discrimination in the United States military and the federal workforce.

[image error]After Truman’s order. the U.S. military was desegregated and integrated units fought in Korea. (Photo: U.S. Army-November 1950)

It is hereby declared to be the policy of the President that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin. This policy shall be put into effect as rapidly as possible, having due regard to the time required to effectuate any necessary changes without impairing efficiency or morale.

Coming in an election year, it was a daring move by Truman, who still needed the support of southern segregationists. It was also a controversial decision that led to the forced retirement of the Secretary of the Army when he refused to desegregate the Army.

President Truman, the first President to speak to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), had based part of his platform on civil rights. Successfully elected but stymied by the 80th Congress, President Truman—armed with documentation from his Committee on Civil Rights—called for a special session for Congress. They were to convene on July 26, 1948.

On that hot, summer day in July, Truman signed his name to two documents: Executive Orders 9980 and 9981, integrating the Armed Forces and the Federal workforce.

Truman’s decision reflected the deep racist discrimination that plagued the country, including the celebrated G.I. Bill, passed to help veterans of World War II with education, housing, and job training. The program, while profoundly significant in American history, was largely closed to Black veterans.

Civil rights groups, frustrated by the lack of progress, continued to press Truman on legislation for racial equality. Knowing that civil rights legislation would stall in Congress, and with the reputation of the United States as a great democratic nation being questioned as racism continued to flourish during a nascent Cold War, on July 26, 1948, Truman signed two Executive Orders, 9980 and 9981, desegregating the federal work force and armed services — practices that would take years to be fully carried out.

Source: “Returning From War, Returning to Racism,” New York Times (July 30, 2020)

As historical documents go, ““Executive Order 9980” and “Executive Order 9981” don’t have quite the same ring as “Emancipation Proclamation” or “New Deal.” But when President Harry S. Truman issued these Executive Orders, he helped transform the country. The first desegregated the federal workforce, segregated by President Woodrow Wilson.

The second order began the gradual official process of desegregating America’s armed forces, which was a groundbreaking step for the American civil rights movement.

It is worth noting that many of the arguments made at the time against integration of the armed services — unit cohesion, morale of the troops, discipline in the ranks– were also made about the question of homosexuals serving in the military, a policy effectively ended when “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was overturned in 2011.

In a Defense Department history of the integration of the Armed Forces, Brigadier General James Collins Jr. wrote in 1980:

The integration of the armed forces was a momentous event in our military and national history…. The experiences in World War II and the postwar pressures generated by the civil rights movement compelled all the services –Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps — to reexamine their traditional practices of segregation. While there were differences in the ways that the services moved toward integration, all were subject to the same demands, fears, and prejudices and had the same need to use their resources in a more rational and economical way. All of them reached the same conclusion: traditional attitudes toward minorities must give way to democratic concepts of civil rights.

Integration of the Armed Forces: 1940-1965 (U.S. Army Center of Military History)

Here is the text of the Executive Order 9981 (Source: Harry S. Truman Library and Museum; dated July 26, 1948)

July 13, 2021

Today in History: Don’t Know Much About® New York’s Bloody Draft Riots

(Originally posted on July 13, 2010; reposted July 13, 2021)

On July 13, 1863, New York City exploded in a four-day long murderous riot, still considered one of the deadliest urban riots in American history. The cause of the riots–violent opposition to the Civil War draft law.

Since poverty has been our crime,

We bow to the decree.

We are the poor who have no wealth

To purchase liberty.

If your picture of draft dodgers is one of 60s-era hippies shouting “Hell No, We won’t go,” the ditty above offers another vision.

It comes from the Civil War era, when the United States passed its first federal draft, the Enrollment Act, in March 1863. (A Confederate Draft had actually preceded the federal draft by two years.)

Under the rules of the law, there were certain exemptions –telegraph operators and railroad engineers were excused, as were certain government employees.

Then there were the rich. They were different. Under the terms of the Civil War draft, a man could avoid the draft by paying $300 or hiring a substitute. J.P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, and future President Grover Cleveland all did it. So did the wealthy father of Teddy Roosevelt.

The practice led to the complaint that the Civil War was “A rich man’s war, but a poor man’s fight.”

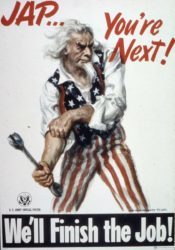

Coming on the heels of the Emancipation Proclamation announced in January 1863, the draft law was bitterly resented. By the summer of 1863 angry protests had taken place in nearly every union state. The headline of one Pennsylvania newspaper read: “WILLING TO FIGHT FOR UNCLE SAM BUT NOT FOR UNCLE SAMBO.”

And resistance to the draft soon turned ugly. Nowhere was the opposition greater or more violent than in New York City where Lincoln was despised by the powerful Democratic party which was openly critical of his administration. The working class Irish were particularly resentful of policies that allowed the wealthy to buy their way out of the draft, and they were hostile toward blacks, many of whom had been used to replace striking Irish longshoreman at New York’s docks.

The anger spilled over into violence in July 1863. On Saturday morning, July 11, the first draftees’ names were pulled in a lottery and announced. They were published alongside the casualty lists from the recent battle of Gettysburg, fought from July 1-3, 1863.

The following Monday, July 13, the draft office at Third Avenue and Forty-sixth Street was attacked by a mob of men armed with clubs who set the building afire. The fire brigade, angry that their jobs were not entitled to an official exemption, joined the mob instead of putting out the fire.

This was the beginning of a four-day spree of looting and arson that ended with murderous rioting.

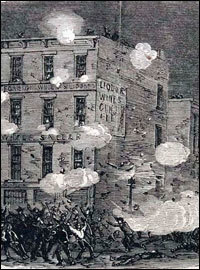

The Draft Riots depicted in Harper’s Weekly August 1, ,1863 Source: New-York Historical Society

Singled out for deadly attacks was the city’s black population. The rioters, many of them too young for the draft got caught up in the frenzy. Hundreds of mostly Irish rioters burned and pillaged their way down Third Avenue, en route to an armory where they seized hundreds of rifles. Another mob attacked an orphanage where black children lived. The anger boiled over into grotesquely savage atrocities. A crippled black coachman was lynched and his body burned. After his genitals were cut off, the mob dragged the body through the streets

One newspaper account published by the African Methodist Episcopal church, read:

“Many men were killed and thrown into the rivers, a great number were hung to trees and lamp-posts, numbers shot down; no black person could show their heads but that they were hunted like wolves. These scenes continued for four days.”

The riots left at least hundreds dead –some estimates range to two thousand—of course, most of them black. Order was eventually restored when troops arrived, some of them from West Point, others returning to New York from the Gettysburg battlefield.

The New-York Historical Society has an excellent overview of the riots and the Civil War period in New York:

New York Divided

July 9, 2021

Who Said It (7-17-2021)

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

President Harry S. Truman (Diary Entry July 17, 1945)

“Promptly a few minutes before twelve I looked up from the desk and there stood Stalin in the doorway. I got to my feet and advanced to meet him. He put out his hand and smiled. I did the same. . . . After the usual polite remarks we got down to business. I told Stalin that I am no diplomat but usually said yes or no to questions after hearing all the argument. It pleased him. I asked him if he had the agenda for the meeting. He said he had and that he had some more questions to present. I told him to fire away. He did and it is dynamite—but I have some dynamite too which I’m not exploding now. . . . I can deal with Stalin. He is honest—but smart as hell.”

(Source: The National Archives)

Stalin and Truman

Source: National Archives, Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer [111-SC-209221-S]

The meeting between Truman and Stalin took place in a suburb of the devastated city of Berlin just before the opening of the Potsdam Conference. Truman, Stalin, and Great Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill, leaders of the three largest Allied nations, were gathered there to discuss the political future of Europe and the conduct of the war still raging in the Pacific.” (Eyewitness: The National Archives)

The day before this meeting, the atomic bomb had been successfully tested in New Mexico. A week later, on July 24, Truman informed Stalin of a “new weapon of unusual destructive force.” Through his network of spies, Stalin already knew about the atomic bomb.

Read my post, “The Month That Changed the World,” a complete account of events in the final days of World War II.

I discuss Truman’s presidency in greater detail in Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents and the post-World War II beginnings of the Cold War in Don’t Know Much About History and The Hidden History of America at War. For more about Stalin read Strongman: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy.

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

The Month That Changed The World: July 16-August 15, 1945

[Originally posted last year to mark the 75th Anniversary of the end of World War II and the transformation of the modern world. Revised and reposted July 9, 2021]

Formal surrender aboard USS Missouri Sept. 2. 1945 https://www.history.navy.mil/our-coll...

From “Trinity” Test to Hiroshima and Nagaskai

The Month That Changed the World

The following timeline summarizes the extraordinary series of events that helped make the modern world between July 16 and August 15, 1945.

The Atomic Bomb Dome-Hiroshima (Photo Courtesy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered)

On August 6, 1945, the New York Times asked:

“What is this terrible new weapon?”

(New York Times, August 6, 1945: “First Atomic Bomb Dropped on Japan”)

The story followed the announcement made by President Harry S. Truman:

“SIXTEEN HOURS AGO an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of T.N.T. It had more than two thousand times the blast power of the British ‘Grand Slam’ which is the largest bomb ever yet used in the history of warfare.”

August 6, 1945

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

(“Statement by the President Announcing the Use of the A-Bomb at Hiroshima”: Truman Library and Museum)

ON July 16, 1945, the first atomic device, nicknamed “the Gadget,” was detonated in the “Trinity” test at Alamogordo, New Mexico. Read this excellent account of the test in National Geographic.

In the course of the next weeks, the world would be transformed, with the arrival of the Atomic Age, Japan’s surrender, the end of World War II, the charter of the United Nations, and the beginning of the Cold War.

July 17 In Potsdam, near Berlin in defeated Germany, Harry S. Truman came face to face with the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. Truman had taken office upon the death of President Roosevelt on April 12 without knowledge of the Manhattan Project or the atomic bomb’s existence. After being told about the potential weapon, Truman was informed of the successful “Trinity” test while meeting Stalin with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the European postwar conference.

“I told Stalin that I am no diplomat but usually said yes or no to questions after hearing all the argument.”

–Read Post on Potsdam and Truman meeting Stalin.

Following the successful test in New Mexico, the components of the atomic bomb were loaded on the USS Indianapolis and transported to an airbase on Tinian Island in the Pacific. Many of the crew of nearly 1,200 men had no idea what the ship was carrying.

Jul7 24 Truman informed Stalin of a “new weapon of unusual destructive force.” But Stalin already know about the atomic bomb because of a network of spies inside the Manhattan Project.

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

The race to capture Berlin in April and May 1945 by the Soviet Red Army was motivated in part by Stalin wanting to secure German scientists working on the atomic bomb and tons of uranium held in a Berlin lab. This episode is recounted in the “Berlin Stories” chapter of my book The Hidden History of America at War.

July 26: Prime Minister Winston Churchill was defeated in the general election and replaced by Clement Attlee as Prime Minister.

“The landslide victory comes as a major shock to the Conservatives following Mr Churchill’s hugely successful term as Britain’s war-time coalition leader, during which he mobilised and inspired courage in an entire nation.”

U.S. Propaganda poster (Source National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/513563)

–BBC

At the Potsdam Conference, the Potsdam Declaration demanded “Unconditional surrender” by Japan. Issued by Great Britain, China, and the U.S., it threatened:

“The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

The Indianapolis reached Tinian that day.

USS Indianapolis 10 July 1945, after final overhaul and repair of combat damage. Photograph from the Bureau of Ships Collection in the U.S. National Archives (Naval History and Heritage Command https://usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.m...)

“Indianapolis departed San Francisco on 16 July 1945, foregoing her post-repair shakedown period. Touching at Pearl Harbor on 19 July, she raced on unescorted and reached Tinian on 26 July, covering some 5,000 miles from San Francisco in only ten days.”

After delivering the atomic bomb components, the ship sailed for Guam and the Philippines. On July 30, the ship was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine and sank in twelve minutes.

“What followed was an ordeal of hell on earth for those who survived the sinking. For a whole host of reasons, many related to the secrecy of her atom bomb mission, the rest of the Navy did not know that Indianapolis was missing.”

— Sam Cox (Rear Adm., USN, Ret.), “Lest We Forget: USS Indianapolis and her sailors”

July 29 The Japanese government rejected the surrender demand.

July 31 The assembly of the atomic bomb, code named “Little Boy,” was completed. The final arming of the bomb would be done in-flight.

In Potsdam, Truman was notified of the bomb being ready. He wrote a message that concluded:

“Release when ready, but not sooner than August 2. HST”

According to the Truman Library:

The actual reply that President Truman wrote on July 31, 1945 (Photo taken by Dawn Wilson at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library)

“No known written record exists in which Harry Truman explicitly ordered the use of atomic weapons against Japan. The closest thing to such a document is this handwritten order, addressed to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, in which Truman authorized the release of a public statement about the use of the bomb. It was written on July 31, 1945 while Truman was attending the Potsdam Conference in Germany. In effect, this served as final authorization for the employment of the atomic bomb, though the expression ‘release when ready’ refers to the public statement.”

August 1 The atomic bomb was ready and flight orders were prepared. But weather delayed the mission. Of four potential target cities, Hiroshima was chosen as the primary target.

In Potsdam that day, the Big Three were wrapping up their meetings and discussed plans for the trials of war criminals that later become known as the Nuremberg Trials.

In the Pacific, hundreds of survivors from the Indianapolis were desperately trying to stay afloat in the shark-infested waters.

“In that clear water you could see the sharks circling. Then every now and then, like lightning, one would come straight up and take a sailor and take him straight down.” – Survivor of the Indianapolis sinking to the BBC.

August 2 The U.S. Navy was still unaware that the Indianapolis had gone down. About 800 men had gone into the water and the survivors were spotted by a reconnaissance plane four days after the sinking; 317 survivors were rescued.

The Big Three at the end of the Potsdam Conference: Front row (Left to Right) Prime Minister Attlee, President Truman, Generalissimo Stalin. Source: Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives.

Shortly after midnight on August 2, the Potsdam Conference concluded with a joint communique. It included reference to the United Nations, whose organization and charter had been completed on June 26 at a conference in San Francisco.

Truman spoke of a future Washington meeting, but he and Stalin never met again.

What was clear was that the Conference had solidified the Soviet Union’s domination over much of Eastern Europe, including the eastern half of a divided Germany. Admiral William D. Leahy, Truman’s Chief of Staff, later wrote:

“The Soviet Union emerged at this time as the unquestioned all-powerful influence in Europe….”

August 4 Colonel Paul Tibbets briefed the men of the 509th Composite Group -the weapon delivery arm of the Manhattan Project. Tibbets was the commander of the unit. His men do not know the nature of the bomb they will carry.

August 5 The bombing mission was confirmed and Colonel Paul Tibbets announced he would pilot the plane which he named “Enola Gay,” after his mother.

Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr., Pilot of the Enola Gay, the Plane that Dropped the Atomic Bomb August 6, 1945 (National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/535737)

August 6 8:15 AM local time: The first atomic bomb was detonated over Hiroshima.

“In less than one second, the fireball had expanded to 900 feet. The blast wave shattered windows for a distance of ten miles and was felt as far away as 37 miles. Over two-thirds of Hiroshima’s buildings were demolished. The hundreds of fires, ignited by the thermal pulse, combined to produce a firestorm that had incinerated everything within about 4.4 miles of ground zero.”

Source: Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered.

“In the street, the first thing he saw was a squad of soldiers who had been burrowing into the hillside opposite, making one of the thousands of dugouts in which the Japanese apparently intended to resist invasion, hill by hill, life for life; the soldiers were coming out of the hole, where they should have been safe, and blood was running from their heads, chests, and backs. They were silent and dazed.

Under what seemed to be a local dust cloud, the day grew darker and darker.”

–John Hersey, “Hiroshima,” New Yorker (August 24, 1946)

In Hiroshima, the estimated death toll was eighty thousand people killed instantly; as many as 90 percent of the city’s nurses and doctors also died instantly. By 1950, as many as 200,000 had died as a result of long-term effects of radiation.

In his official announcement, President Truman said,

It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.

Read Don’t Know Much About Hiroshima for more details about the bombing and its aftermath.

August 7 On Guam, the decision to use a second device was made and the mission date set for August 10, then moved to August 9 over weather concerns.

Fat Man being lowered and checked on transport dolly for airfield trip Image Source: Heritage Foundation https://www.atomicheritage.org/histor...

August 8 Fulfilling a pledge Stalin made earlier at the Yalta conference, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Manchuria the next day, sending more than one million troops into Japanese-held territory.

The Japanese military leadership was still divided over the surrender demand, with some leading generals vowing to fight to the death. A coup against Emperor Hirohito began to be planned by members of the Japanese military.

A plutonium bomb code named “Fat Man” is prepared on Tinian. It will be carried by a B-29 called “Bockscar.” The primary target was the city of Kokura, home to a large munitions plant.

The crew of the B-29 called “Bockscar” taken after the Nagasaki bombing (Image: U.S. Air Force)

August 9 When clouds and smoke from nearby fires obscured Kokura, “Fat Man” was instead dropped over the secondary target, the city of Nagasaki, with a population estimated at 263,000, a city that was home to two Mitsubishi military plants. It is also the site of a prisoner of war camp.

“Nagasaki was a city on the west coast of Kyushu on picturesque Nagasaki Bay. It was famous as the setting for Puccini’s beautiful opera Madame Butterfly. It was also home to two huge Mitsubishi war plants on the Urakami River. This complex was the primary target, but because the city was built in hilly, almost mountainous terrain, it was a much more difficult target than Hiroshima…

Fat Man exploded at 1,840 feet above Nagasaki and approximately 500 feet south of the Mitsubishi Steel and Armament Works with an estimated force of 22,000 tons of TNT.

Unlike Hiroshima, there was no firestorm at Nagasaki. Despite this, the blast was more destructive to the immediate area, due to the topography and the greater power of Fat Man.”

—Hiroshima & Nagasaki Remembered

The death toll in Nagasaki also reached 80,000 by the end of 1945. Read a full account of this mission in “Nagasaki: The Last Bomb” by Alex Wellerstein (New Yorker, August 7, 2015)

The National Archives “Unwritten Record” blog also offers resources on the atomic bombings.

August 10 After Nagasaki was bombed, Truman ordered no more strikes without his authorization. Another plutonium core for a third weapon was prepared for shipment.

September 24, 1945, 6 weeks after Nagasaki was destroyed by the world’s second atomic bomb attack. Photo by Cpl. Lynn P. Walker, Jr. (USMC) National Archives FILE #: 127-N-136176

Although an unofficial surrender message was sent by a Japanese news agency, the Japanese cabinet was divided and no decision was made. The Emperor would not surrender his sovereignty.

August 11 The U.S. Secretary of State James Byrnes rejected any conditional surrender and stated that the Emperor and Japan’s government will be subject to the Allied Powers and declared that any future Japanese government must reflect the will of the people.

Soviet troops invade South Sakhalin island, Japanese-held territory.

August 12-13 Soviet troops advanced into the Korean peninsula.

Emperor Hirohito agreed to accept the terms of Secretary Byrnes’ note and ordered the suspension of military activity. He recorded a surrender announcement. Military officers began to plot against Hirohito in a coup known as the “Kyujo incident.”

August 13 The bombing of Japan, including firebombing, resumed with more than 1,000 B-29s taking part.

Japanese officers continued to seek allies in their planned coup against the Imperial government.

Residential section of Tokyo after the March 1945 air raids. (Wikimedia commons http://www.kmine.sakura.ne.jp/kusyu/k...

August 14 (August 15 in Japan): The military coup failed and several plotters committed suicide.

In an extraordinary address recorded earlier, the Emperor of Japan spoke on the radio for the first time and accepted the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration, agreeing to the unconditional surrender.

Read: “The Emperor’s Speech” by Max Fisher (The Atlantic, August 15, 2012)

At a White House conference, according to United Press International, Truman said:

“This is the day when Fascist and police governments cease to exist in the world. This is the day for democracy.”

-Source: “Japan Surrenders Unconditionally, World At Peace” UPI archives

Truman announces Japan’s surrender to reporters in Oval Office.

Credit: Rowe, Abbie National Park Service Harry S. Truman Library & Museum.

Across America and England, jubilant crowds filled the streets once more for an unofficial V-J (Victory over Japan) Day, as they had three months earlier on VE Day, May 8,1945, after Germany’s surrender ended the war in Europe.

A video clip of Truman’s August 14 announcement from C-Span.

V-J Day Times Square August 14, 1945 Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c19650

September 2, 1945 A formal surrender ceremony was performed in Tokyo Bay and that date is also referred to as V-J Day.

Almost since the day the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, critics have second-guessed Truman’s decision and motives. A generation of historians and commentators have defended or repudiated the need for unleashing the atomic weapon. Admiral William D. Leahy, who was with Truman at Potsdam, later wrote in a memoir:

Once it had been tested, President Truman faced the decision as to whether to use it. He did not like the idea, but he was persuaded that it would shorten the war against Japan and save American lives. It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan.

–William D. Leahy, I Was There (1950)

In China, however, the Japanese surrender ended the wartime alliance between the Communists and Nationalists. The Chinese civil war began anew, with the US supporting Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Stalin’s USSR backing Mao Zedong’s Communists.

Many historians contend that preventing death and casualties in an invasion of Japan was only a partial explanation for the use of the two atomic bombs. The United States was already wary of Stalin and his designs on Japan’s wartime territory. They argue that the use of the two devices was meant to end the war quickly to prevent Stalin from capturing territory held by Japan. It may have also been a signal to Stalin and the Soviet Union that the United States possessed these weapons and was willing to use them.

In other words, the dropping of the atomic bombs became the first volley in the Cold War.

READ about the debate in this Smithsonian article.

In 1952, Albert Einstein –whose 1939 letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt had set the Manhattan Project in motion — wrote a brief essay published by a Japanese magazine Kaizo in which he stated:

I was well aware of the dreadful danger for all mankind, if these experiments would succeed. But the probability that the Germans might work on that very problem with good chance of success prompted me to take that step. I did not see any other way out, although I always was a convinced pacifist. To kill in war time, it seems to me, is in no ways better than common murder.

He concluded:

Gandhi, the greatest political genius of our time has shown the way, and has demonstrated the sacrifices man is willing to bring if only he has found the right way. His work for the liberation of India is a living example that man’s will, sustained by an indomitable conviction is stronger than apparently invincible material power.

–Source Hiroshima & Nagasaki Remembered

You can read more about Hiroshima and the dropping of the atomic bombs in Don’t Know Much About History and more about President Truman in Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents and in The Hidden History of America At War. Read more about Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin in STRONGMAN which will be published on October 6, 2020.

July 6, 2021

When Irish Eyes Were Not Smiling-The Bible Riots

(This is a revised version of a post that originally appeared on March 17, 2012)

On July 6, 1844, a second round of deadly anti-Catholic violence took place right after Independence Day in the City of Brotherly Love.

A reminder once more that the “dangerous, dirty, job-stealing” immigrants were once Irish and Catholic.

Once upon a time, the Irish –and specifically Irish Catholics– were vilified by the majority in White Anglo-Saxon Protestant America. The Irish were considered the dregs by “Nativist” Americans who leveled at Irish immigrants all of the insults and charges typically aimed at every hated immigrant group: they were lazy, uneducated, dirty, disease-ridden, a criminal class who stole jobs from Americans. And dangerous. The Irish were said to be plotting to overturn the U.S. government and install the Pope in a new Vatican.

One notorious chapter in the hidden history of Irish-Americans is left out of most textbooks — the violently anti-Catholic, anti-Irish “Bible Riots” of 1844.

In May 1844, Philadelphia –the City of Brotherly Love– was torn apart by a series of bloody riots. Known as the “Bible Riots,” they grew out of the vicious anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiment that was so widespread in 19th century America. The second round of mob violence began on July 6, 1844.

Families were burned out of their homes. Churches were destroyed. And more than two dozen people died in one of the worst urban riots in American History.

You can read more about America’s history of intolerance –religious and otherwise– in this Smithsonian essay, “America’s True History of Religious Tolerance.”

July 4, 2021

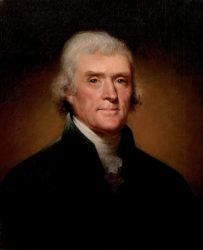

Don’t Know Much About® Thomas Jefferson

(Original post of 2011; revised July 4, 2021)

Among America’s iconic Founding Fathers, is there a more complicated and contradictory figure than Thomas Jefferson?

Scientist, humanist, Enlightenment thinker, writer, architect, politician. He was all these things. The confusion over this genius comes from one basic question: How could the man who wrote, “All Men are Created Equal” and “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness” go home to a Monticello plantation, completely dependent upon enslaved labor?

Even Jefferson’s birthday is confusing. History books say he was born on April 13,1743. But the grave marker at Monticello says he was born on April 2. That one is easier to answer than some of the larger contradictions in Jefferson’s life. Jefferson was born while the old Julian calendar was still in use in Protestant England and its American colonies. So the April 2 date is called “Old Style” (O.S.). When Great Britain and America finally came around and adopted the Gregorian (named for Pope Gregory) Calendar in 1758, Jefferson’s birth date was changed to April 13.

Birth date aside, Thomas Jefferson more than anyone embodies the “Great Contradiction” in American history. How could a nation dedicated to ideals of freedom and liberty continue a system that enslaved human beings in the cruelest of ways?

That contradiction is nowhere more evident than in Jefferson’s original draft of Declaration of Independence.

A few years ago, at the New York Public Library, I had the thrill of seeing Jefferson’s handwritten copy of his original draft of the Declaration of Independence. We may take the words for granted now. But Jefferson gave full voice to the idea that we all possess “inalienable rights.” That we are “created equal.” That we have basic rights to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” That governments exist to advance those human rights, and only with the “consent of the governed.”

“Fair Copy” of The Declaration of Independence (Source: New York Public Library)

This document was written on both sides of two pieces of paper. In his careful, flowing script, Jefferson included all of his original wording to show what the Congress in Philadelphia had changed, underscoring words and phrases that had been deleted. Those alterations, Jefferson, thought were “mutilations.” Distressed by the editing, he made these “fair copies” of his original some time after July 4th.

The most startling of these changes is a paragraph about what Jefferson calls “this execrable commerce” — slavery. Jefferson charged that King George III was responsible for the slave trade and was preventing American efforts to restrain that trade. The section was deleted completely. But it is striking to see Jefferson’s bold, block lettering when he describes:

an open market where MEN should be bought & sold

He clearly wanted to underscore his belief that enslaved people were “MEN.”

The contradiction is troubling and difficult to resolve. Jefferson knew slavery was wrong. He believed, like fellow slaveholder George Washington, that it would end. But both were inextricably tied to a society and economy, built on enslavement, even though they believed that the “peculiar institution” would gradually die out.

Of course, part of the cynicism in Jefferson’s case is due to the relationship between Jefferson and an enslaved woman Sally Hemings. Monticello now acknowledges that relationship existed, a contention first raised publicly in 1802 by muckraking newspaperman James Callender. In recent years, Monticello has also gone a long way in addressing the question of enslaved life at the plantation.

Jefferson, who died on July 4, 1826 –the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration– and his deep contradictions are the perfect reminder that politicians are people –even the marble gods like Washington and Jefferson. Their all-too human flaws are proof of that as well as the fact that history books once tried to hide these flaws by pointing to the past with pride and patriotism.

Thomas Jefferson’s Grave Marker at Monticello (Photo: Kenneth C. Davis, 2010)

Those flaws are explored in several of my books, including Don’t Know Much About History, Don’t Know Much About the Civil War and most recently, In the Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents and Five Black Lives.

July 2, 2021

Who Said it? (7/2/2021)

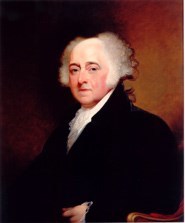

John Adams in a letter to Abigail Adams (July 3 1776)

But the Day is past. The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America….It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

(Source: Massachusetts Historical Society- Adams Electronic Archive)

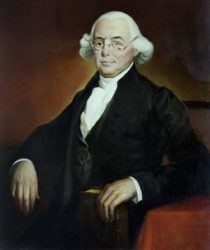

John Adams portrait by Gilbert Stuart

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress had passed a resolution of independence for America. The next day, Adams wrote to his wife expressing his optimistic view that the date would go down in history and be cause for great celebrations.

He was off by two days.

After considerable debate, Congress adopted Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence and July 4th was quickly established in the American imagination as “Independence Day.”

June 30, 2021

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (11 of 11)

[Post revised 6/30/2021]

The Declaration Mural by Barry Faulkner (National Archives)

Key to Numbers in “The Declaration Mural” by Barry Faulkner

The final entry in a blog series profiling the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence. The series begins here. The previous posts can be found in the website Blog category.

AS THE NATION examines the role slavery played in its history, it is important to recognize that slavery was an issue in 1776. Among the men who eventually signed the Declaration, at least forty of them enslaved people or took part in the slave trade. A “YES” following the entry means the Signer enslaved people; “NO” means he did not.

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

A New Hampshire slaver. A forgotten founder who died in debt and disgrace. A college president. A legendary bullet maker. Jefferson’s teacher –and a murder victim. Last but not least among the 56 signers.

–William Whipple (New Hampshire) Often described as a 46-year-old “merchant,” he was more precisely a sea captain who made a fortune sailing between Africa and the West Indies — in other words, the merchandise was human cargo.

He also enslaved people and one of those men, known as Prince, accompanied Whipple throughout his illustrious career as an officer in the Revolution. It was thought that Prince was the Black man depicted in the famous “Washington Crossing the Delaware” painting, but that is not accurate because Prince and Whipple were far from the action that night. Whipple later served in a variety of state offices in New Hampshire and legally manumitted Prince –who also went by the name of Caleb Quotum — in 1784. Whipple died in Portsmouth in 1785. YES

Gravestone of Prince Whipple https://www.blackpast.org/african-ame...

–William Williams (Connecticut) A 45-year-old merchant, he was a veteran of the French and Indian War who was under command of his uncle Ephraim Williams, who was shot and killed in the war. (Ephraim Williams’s will provided funds for the founding of what became Williams College in Massachusetts.) Planning to follow his father as a minister, he attended Harvard but instead opened a store and became a successful merchant.

Williams married Mary Trumbull, the daughter of Connecticut’s Royal Governor. Governor Trumbull was a Royal Governor who supported the patriot cause and was a friend and adviser of George Washington. One of Mary Trumbull’s brothers, John Trumbull, became the most famous painter of the American Revolution, and another later became Connecticut’s Governor.

William Williams was not present for the July vote but signed the Declaration and was a tireless supporter of the war effort. After a long career in public service, he died in 1811, aged 81. NO

–James Wilson (Pennsylvania) Scottish-born, he was a 33-year-old lawyer at the time of the signing and one of the most important Founding Fathers you probably never heard of. A key supporter of the Declaration, Wilson was among the signers and Philadelphia elites who were attacked in his home during the war in a riot over food prices and scarcity.

Wilson was also a key member of the Constitutional Convention, credited with several significant compromises. Although hopeful to be made Chief Justice of the new Supreme Court, he was appointed an associate by Washington. But land speculation ruined him and he ended up in debtor’s prison, like his colleague Robert Morris (See previous post #7) before his death in disgrace at age 55 in 1798, an embarrassment to his Federalist friends and colleagues. NO

The official portrait of Supreme Court Justice James Wilson.

–John Witherspoon (New Jersey) Another profoundly influential immigrant, the Scottish-born minister was the 53-year-old president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) where his hatred of the British influenced many students including notable schoolmates Aaron Burr and James Madison. He lost a son at the battle of Germantown in 1777, but continued his career in Congress. After the war, he attempted to rebuild the college and was a prime mover in the growth and organization of the Presbyterian Church. He died in 1794 in Princeton, where he is buried, at age 71. YES

A photograph of Maclean House, also called the President’s House, at Princeton University. Built 1756. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...

–Oliver Wolcott (Connecticut) A 49-year-old lawyer, he was also a veteran of the French and Indian War who was not present for the vote and signed at a later date. Wolcott was in New York when Washington’s troops tore down a statue of King George III after hearing the Declaration of Independence read. He is credited with the plan to melt down the lead statue and turn it into bullets for the war effort. He served in the Connecticut militia during the Revolution and held a series of state posts after the war including as governor of Connecticut at his death in 1797, aged 71. YES

–George Wythe (Virginia) A 50-year-old lawyer at the signing, he may have made his greatest mark as a teacher of law to Thomas Jefferson who lived with Wythe while at the College of William and Mary –as well as later students including James Monroe, future Chief Justice John Marshall, and congressman Henry Clay, earning him the title “America’s first law professor.”

He died in 1806 , around 80, apparently murdered by a nephew by arsenic poisoning. The nephew was perturbed that Wythe had emancipated his enslaved people and planned to give half his estate to one of those emancipated people. The nephew was acquitted of murder after the testimony of a formerly enslaved woman was disallowed because she was black. The nephew was convicted of forging his uncle’s checks. YES

George Wythe, Signer of Declaration of Independence New York Public Library Digital Gallery (Digital Image ID: 484381)

Read the story of James Wilson and the Philadelphia Riot in America’s Hidden History.

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah