Rod Collins's Blog, page 14

February 24, 2015

Managing Content? Start With Metadata

by John Horodyski

To effectively manage and exploit a company’s knowledge, you need a metadata plan. The successful implementation of any content-related strategy — be it data, digital assets or text — requires implementation of a holistic metadata schema that is supported by technology, people and process.

Building a DAM or CMS without a metadata plan is akin to throwing papers in an unmarked box. The systematic organization that metadata provides increases the return on investment of a content system by unlocking the potential to ingest, discover, share and distribute assets.

What is Metadata?

“Metadata is a love note to the future.” — unknown

Simply stated, metadata is information that describes other data — data about data. It is the descriptive, administrative and structural data that define assets

Simply stated, metadata is information that describes other data — data about data. It is the descriptive, administrative and structural data that define assets

1 Descriptive metadata describes a resource for purposes such as discovery and identification (i.e., information you would use in a search). It can include elements such as title, creator, author and keywords.

2 Structural metadata indicates how compound objects are put together, for example, how a digital image is configured as provided in EXIF data, or how pages are ordered to form chapters (e.g. file format, file dimension, file length).

3 Administrative metadata provides information that helps manage an asset. Two common subsets of administrative data are rights management metadata (which deals with intellectual property rights) and preservation metadata (which contains information needed to archive and preserve a resource).

As a structural component of a DAM or CMS, metadata becomes an asset unto itself — and an important one, at that. It provides the foundation needed to make assets more discoverable, accessible and, therefore, more valuable. In other words: Metadata transforms content into “smart assets.” Simply digitizing video, audio, graphic files provides a certain convenience, but it is the ability to find, share and distribute files with specific attributes that unlocks their full potential and value.

Search, and You Shall Find Happiness

“This search for what you want is like tracking something that doesn’t want to be tracked. It takes time to get a dance right, to create something memorable.” — Fred Astaire

Research shows that workers waste more than 40 percent of their time searching for existing assets and recreating them when they are not found. This lost productivity and redundancy from the non-discovery of assets is expensive. Inefficiency only increases over time as a system grows, evolves and is exposed to new kinds of content and users.

It’s estimated that every year, 800 neologisms (new words and phrases) are added to the English language. Metadata is a snapshot representing the business processes and goals at a particular time. In an ever-changing business environment, metadata must be able to evolve over time. If maintained and governed well, metadata will continue to contribute to expanding business needs.

The best way to plan for future change is to apply an effective layer of governance to metadata. Remember that metadata is a “snapshot” in time. Take the time to manage language, and control the change.

Why Metadata

Metadata is the best way to protect and defend digital assets from information overload and mismanagement. Invest the time, energy and resources to identify, define and organize assets for discovery. Metadata serves asset discovery by:

Allowing assets to be found by relevant criteria

Identifying assets

Bringing similar assets together

Distinguishing dissimilar assets

Giving location information

You know that assets are critical to business operations. You want them to be discovered at all points within a digital lifecycle from creation, to discovery and distribution. To accomplish this, establish systems that inspire trust and certainty that data is accurate and usable. Metadata increases the return on investment on the assets and is also a line of defense against lost opportunities. Think about the digital experience for users and ensure they identify, discover and experience brand the way in which it was intended. It is a necessary defense.

Metadata Design: Where to Start?

“Your present circumstances don’t determine where you can go; they merely determine where you start.” — Nido Quebin

The path to good metadata design begins with the realization that digital assets need to be identified, organized and made available for discovery. The following questions serve as the beginning of that design:

1. What problems do you need to solve?

Identify the business goals of the organization and how metadata may contribute to those goals. The goal is to be “cohesive,” not “disjointed”

2. Who is going to use the metadata and for what?

Consider the audience for the metadata and decide how much metadata you need. The best strategy is accurate intelligence

3. What kinds of metadata are important for those purposes?

Be specific about today and plan for flexibility in the future by developing an extensible model that will allow for growth and evolution over time.

Metadata is the foundation for every digital strategy. It is needed to deliver an optimized and fully engaging consumer experience. There are other critical steps to take as well, including building the right team, making the correct business case, and performing effective requirements gathering — but nothing can replace an effective metadata foundation. The goal of storing assets is discovery — they want to be found. Metadata will help ensure that you are building the right system for the right users.

An Ongoing Effort

“A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step” and there is no greater journey upon which to embark than that of managing content. Metadata is never really done, it’s continuous; an ongoing improvement and development that needs time and effort. As with all good governance practices, it demands full attention to change. The sophistication of metadata lies in its evolution within an organization.

Metadata matters. It’s neither a trend, nor a buzzword. Metadata is the most real application of asset and data management that enables creation, discovery and ultimately to distribution and consumption. Start now!

This article was originally published in CMSWire.com

John Horodyski @jhorodyski is a Partner within the Media & Entertainment practice at Optimity Advisors, focusing on Digital Asset Management, Metadata and Taxonomy.

February 17, 2015

The New Role Of The 21st Century CEO: The Chief Enabling Officer

by Rod Collins

Several years ago, the future CEO of what is today a Fortune 100 company had a problem. The staff at the then young company had been working on the development of a major product line that its leaders hoped would become the major revenue stream for the business. This revenue source was to be a prime attraction that would entice investors in its upcoming IPO. As the future CEO inspected the product prototype one Friday afternoon, he wasn’t happy with what he saw. The prototype was seriously flawed.

In most companies, these developments would have triggered a highly directed management response. In all likelihood, the CEO would have convened an emergency meeting of key leaders on Monday morning to develop an urgent corrective action plan with milestone expectations and an ambitious completion date several weeks out. A special ad hoc work group would have been assigned responsibility for solving the problem, an oversight steering committee would have been formed to monitor the progress of the work group, and a single senior executive would have been held accountable for completing the critical corrective action plan.

A Simple But More Effective Approach

But that’s not what happened in the young company because by the time everyone was returning to the office the following Monday morning, the problem was essentially solved. The CEO in this case didn’t then and still doesn’t today believe in corrective action plans—or any plans, for that matter—because he sees plans, and their related monitoring activities, as limiting factors that hold people back and slow people down. He believes fixed plans are actually counterproductive, especially when the task at hand is extremely urgent.

The young company was Google and the CEO was Larry Page. The prototype Page was examining was an early version of AdWords, and the problem was an application that was presenting useless and unrelated ads with its user searches. Page’s response to correcting the flawed prototype, described by Eric Schmidt and Jonathan Rosenberg in their book How Google Works, was a simple—but a far more effective—approach that you won’t learn in business school. Before going home on that Friday evening, Page printed a sample of the pages containing the useless ads, posted them on the bulletin board on the wall of the company kitchen, and wrote “These Ads Suck” across the top of the pages.

Over the weekend, Page didn’t call or e-mail anyone, nor did he schedule an emergency meeting. Instead, five Google colleagues, who had seen Page’s note and agreed with his assessment, voluntarily worked on a fix over the weekend. They did a detailed analysis of the dynamics of the problem, crafted a collective solution, and created a new and greatly improved prototype that was ready for examination on Monday morning. And what’s perhaps most astonishing about this story is that none of the five volunteers had responsibility for the ads project.

Leading by Being in Charge

Traditional leaders go into a highly directive mode when critical problems happen because that’s the way their organizations work. For over a century, the fundamental assumption that has served as the cornerstone of management practice is the notion that the smartest organizations leverage the intelligence of their smartest individuals. That’s why traditional organizations have been designed as top-down hierarchies. Hierarchical management assumes that the smartest individuals will rise up the corporate ladder, and that, by giving the supposed smart people at the top the power to command and control the work of their subordinates, the whole organization will perform smarter than if everyone were left to his or her own devices.

Traditional leaders go into a highly directive mode when critical problems happen because that’s the way their organizations work. For over a century, the fundamental assumption that has served as the cornerstone of management practice is the notion that the smartest organizations leverage the intelligence of their smartest individuals. That’s why traditional organizations have been designed as top-down hierarchies. Hierarchical management assumes that the smartest individuals will rise up the corporate ladder, and that, by giving the supposed smart people at the top the power to command and control the work of their subordinates, the whole organization will perform smarter than if everyone were left to his or her own devices.

At the top of the ladder is the CEO, which is the common acronym for the Chief Executive Officer. In the typical company, the CEO is the “big boss,” the person who has the authority to direct the efforts of the entire company. As such, the CEO is responsible for making the key decisions about how and what the company does, and is expected to be “on top” of all critical issues affecting the health of the business. When something major goes wrong, the chief executive is expected to take charge, and like the proverbial captain of the ship, direct the flow of the critical work of the special workgroups and oversight committees as they navigate the business through troubled waters. When companies are designed to leverage the intelligence of the smartest individuals, there is a clear chain of command responsible for assigning and monitoring the work of those whose jobs are to follow directions.

A Different Way of Leading

Larry Page, however, is not a traditional leader. While he relishes and successfully hires smart people at Google, he doesn’t believe that the smartest organizations leverage individual intelligence through the ascription of command authority. That’s because the fundamental strategy of the business he co-founded with Sergey Brin is based on a radically different assumption: The smartest organizations are those that know how to aggregate and leverage collective intelligence.

This alternative assumption explains why, although it was the last search engine to enter a crowded field of upstarts, Google quickly became the application of choice for the vast majority of Internet users. What separated Google from other search engines was an algorithm that used the wisdom of the crowd rather than the judgments of editorial experts to rank the pages in a web search. Page and Brin turned the notion that nobody is smarter or faster than everybody into a highly successful operating system. But even more powerfully, as they built their company, they used the logic of their operating system to guide the design of their organization. Rather than building a top-down hierarchy that leveraged the individual intelligence of the few, they created a collaborative network that leveraged the collective intelligence of the many. The essence of Page’s management philosophy is to hire good people and to stay out of their way by providing them the space to self-organize their own work. When self-organization is the norm and companies are designed to leverage collective intelligence, people don’t wait around to be told what to do. If they see a problem, they form their own teams, put their heads together, and find a solution. Without the constraints of bureaucracy, they have the wherewithal to solve the problem in a fraction of the time that would be possible under the best-formulated plan of action.

Managing Change Means Changing How Manage

As the technology revolution continues to transform the business landscape, business leaders are under increasing pressure to keep pace with a rapidly changing world. This challenge is exacerbated by the troubling fact that the world is changing much faster than most organizations. If business leaders want to close this gap, they need to accept that the only way they will be able to manage at the pace of change is to change how they manage. And that challenge begins with the CEO.

As the technology revolution continues to transform the business landscape, business leaders are under increasing pressure to keep pace with a rapidly changing world. This challenge is exacerbated by the troubling fact that the world is changing much faster than most organizations. If business leaders want to close this gap, they need to accept that the only way they will be able to manage at the pace of change is to change how they manage. And that challenge begins with the CEO.

Larry Page is effectively leading an organization that is at the forefront of change because, in his role as the CEO, he behaves more like a chief enabling officer than a chief executive officer. He and Brin have created an organization that enables anyone in the company to initiate an idea, organize a team, or solve a problem without waiting for permission or direction. In a rapidly changing world, the role of the CEO is a sharp departure from what most of us learned in business school.

Chief executive officers are leaders of hierarchies whose main job is to make decisions and to oversee the execution of those decisions. The chief executive officer is responsible for planning, organizing, directing, coordinating, and controlling the efforts of the many departments under his charge. Thus, the powerful CEO in the top-down hierarchy is proficient in the competencies of command-and-control and knows how to exercise power by skillfully taking charge.

Chief enabling officers, on the other hand, lead not by amassing power to themselves, but rather by enabling the practice of power throughout the entire organization. They do this by designing their organizations as highly connected collaborative networks where people are primarily accountable to their peers rather than to single supervisors. Chief enabling officers understand that, in a hyper-connected world, power is more about being connected than being in charge. They understand that, in a rapidly changing world, no single person can process everything happening in the marketplace in real time, and they appreciate the wisdom that nobody is smarter or faster than everybody. That’s why they don’t construct bureaucratic barriers to getting things done, and they encourage all their smart people to self-organize themselves when they see that something needs to be done. When people have the freedom to get things done, the time to solution is reduced from weeks to days.

If business leaders want to manage at the pace of change, those who are still leading top-down hierarchies will most likely need to change the fundamental ways that their organizations work. They will need to learn how to effectively build and lead collaborative networks by understanding and embracing the new role of the CEO, the Chief Enabling Officer.

Rod Collins (@collinsrod) is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, 2014).

February 5, 2015

Payoffs, Purpose, and Meaningful Work

by Rod Collins

When I was an undergraduate student, I recall a psychology professor relating a story about Sigmund Freud in the final years of his life. Freud had fled his native Austria to settle in London to escape the Nazi oppression. According to the story, a young psychiatrist had traveled from the continent to London to ask the father of psychoanalysis a burning question. When he met Freud, the young man explained that, in studying the pioneer’s work, he had learned much about the abnormal personality, the factors that lead to neurotic disabilities, and the ways to treat people to relieve them of their disorders through psychoanalysis. But what he hadn’t come across in his training was an understanding of what factors contribute to the natural development of the healthy personality. Expecting a long and comprehensive discourse from the celebrated scholar, the young psychiatrist was surprised by Freud’s simple three-word answer: “Love and work.”

One of the attributes of true wisdom is that it is often found in a profound and simple statement. When you think about it, when adults have the capacity to love the significant people in their lives and the good fortune to do work that adds real value to the lives of others, they have the ingredients for what can be arguably described as a meaningful life.

The Millennials Preoccupation with Meaning

Interestingly, in a recent New York Times column, “The Problem With Meaning,” David Brooks questions the current preoccupation of today’s millennials in their pursuit of meaningful lives. While Brooks aptly describes a meaningful life as one where a person finds “some way of serving others that leads to a feeling of significance,” he bemoans that the term meaning has been coopted by a new generation whose use of the word is “flabby and vacuous, the product of a culture that has grown inarticulate about inner life.” He implies that millennials are motivated by a self-regarding emotion and superficial sentiment that tries to replace the foundation of “structures, standards and disciplines” that define our basic moral systems. Brooks concludes, “Because meaningfulness is based solely on emotion, it’s contentless and irreducible…. subjective and relativistic.”

In his response in a subsequent Forbes column, “David Brooks Misconceives The Meaningful Life,” Stephen Denning challenges Brooks’ conclusions about the current cultural evolution, and more importantly, his implied assumptions about the desirability of traditional institutions. Denning writes:

“Rather than lamenting the allegedly narcissistic failings of our culture and the younger generation, Brooks might do better to cast a critical eye at ‘the structures, standards, and disciplines’ that his own generation has created and that he is suggesting that we all embrace.”

Denning argues the real narcissism in our culture is more likely a product of the skewed incentives and the asymmetrical payoffs of a traditional leadership class who are extracting more value than they create. Because the millennials, at this point, are not in a position to transform the institutions of “a world that is not of their own making,” the one thing they can do to prepare for the future when the leadership mantle is passed to them, is to learn to lead differently so they may actualize the much needed transformation of traditional institutions ill-equipped for the challenges of a twenty-first century world. Denning lauds the new generation for “seeking meaning in the sense of finding ways in which their own lives can make a positive difference.”

Institutions Are Creations of Their Times

David Brooks’ implicit faith in traditional institutions may be misplaced. That’s because we suddenly find ourselves confronted by a new world with new rules. The structures, standards, and disciplines that most of us are familiar with are creations of the Industrial Age, which, in its seminal years, transformed the institutions of its time and defined the contours of the twentieth century. Today, the world is being transformed once again by the rapid emergence of the new Digital Age and we are discovering that the context of twenty-first century living is very different from that of the previous century. We are especially experiencing this transformation in the world of work, where an emerging new and radically different operating model is reshaping the institution of management.

David Brooks’ implicit faith in traditional institutions may be misplaced. That’s because we suddenly find ourselves confronted by a new world with new rules. The structures, standards, and disciplines that most of us are familiar with are creations of the Industrial Age, which, in its seminal years, transformed the institutions of its time and defined the contours of the twentieth century. Today, the world is being transformed once again by the rapid emergence of the new Digital Age and we are discovering that the context of twenty-first century living is very different from that of the previous century. We are especially experiencing this transformation in the world of work, where an emerging new and radically different operating model is reshaping the institution of management.

Traditional management is a creation of the Industrial Age as a response to the then new need to organize the work of large numbers of people as the locus of work moved from the family farm to the burgeoning factories. From its earliest days, the fundamental model has been the top-down hierarchy, which assumes that the smartest organizations are those that effectively leverage the individual intelligence of their smartest individuals by giving them the authority to command and control the work of their subordinates. This institution, while far from perfect, was nevertheless highly effective for well over a hundred years. Hierarchical management has been so ingrained into the cultural mindset that most of us cannot conceive of any other way to structure a large organization.

Hierarchical Structures Disconnect People From Meaningful Work

Despite its role in advancing the economic well being of society by providing the means for vast number of people to move from poverty into the middle class, hierarchical structures have taken a toll on the individual lives of people by disconnecting them from meaningful work. In hierarchies, only the voices of the few at the top matter; the rest learn that a steady paycheck comes to those who keep their mouths shut and do what they are told. These paychecks are essentially transactional payoffs in organizations where the fulfillment of transactions is the basic context of business activity. It’s not surprising that, according to a recent Gallup study, only a mere 13 percent of people are engaged at work. If large numbers of people are disengaged, then chances are they are finding very little meaning at the place where they spend most of their time. When the focus of work is on discreet transactions, few people understand how their work adds value to the lives of others. They work for economic payoffs, but they have little passion for the places where they work.

From Payoffs To Purpose

On the other hand, the recent technological revolution has created the need for a very different management model—one that is better designed for navigating a business world transformed by the accelerating change, escalating complexity, and ubiquitous connectivity spawned by the revolution. This model assumes that the smartest organizations are those that have the capacity to quickly aggregate their collective intelligence. And the leaders who embrace this innovative management model understand that you can’t leverage collective intelligence unless all voices in the organization have the ability to be heard. That’s why these vanguard leaders eschew hierarchies and prefer to design their organizations as peer-to-peer networks.

On the other hand, the recent technological revolution has created the need for a very different management model—one that is better designed for navigating a business world transformed by the accelerating change, escalating complexity, and ubiquitous connectivity spawned by the revolution. This model assumes that the smartest organizations are those that have the capacity to quickly aggregate their collective intelligence. And the leaders who embrace this innovative management model understand that you can’t leverage collective intelligence unless all voices in the organization have the ability to be heard. That’s why these vanguard leaders eschew hierarchies and prefer to design their organizations as peer-to-peer networks.

The leaders of these innovative networks see the fundamentals of business very differently from their hierarchical counterparts. For them the primary purpose of a business is not about creating shareholder wealth, but rather about creating customer value. This is not to say that shareholder wealth is not important. Indeed, it is very important because, without positive cash flow, no business can survive for very long. Rather, the vanguard leaders understand that shareholder wealth is not the rationale for doing business, but rather the reward that markets give companies when they do business well by consistently creating customer value. This explains why companies such as Google, Zappos, W.L. Gore and Associates (the makers of Gore-Tex), Amazon, and Morning Star consistently outperform their traditional counterparts.

When the purpose of a business is to create customer value, the focus of the organization is not about processing discreet transactions but rather about creating delightful customer experiences and long-term customer connections. And the best way to assure that the organization is connected to its customers is to make sure that everyone in the organization is connected to the true purpose of the business by creating a shared understanding around how each person can make a contribution to the customers they serve. This shared understanding is both an individual and a collective experience of meaning that is rooted in the emotional connection that comes from knowing that those who serve are making a difference in other people’s lives.

When the emotional foundation of work has more to do with the fulfillment of a long-term purpose than short-term payoffs, then work stands alongside love as the passionate pillars of an emotionally rich and meaningful life. Maybe that’s why so many of the vanguard companies are listed on Fortune’s “Best Companies To Work For” and why the millennials, the first generation raised in the hyper-connected Digital Age, are preoccupied with living meaningful lives.

While Brooks’ lament of the millennials’ disregard for traditional systems may be true, his conclusion that the younger generation’s focus on meaning is more superficial than substantive may be more reflective of his lack of understanding than theirs. Denning’s assessment—that the millennials search for meaning is part of a journey to make a positive difference in the way institutions will enhance the human experience in the future—is likely a more accurate depiction of the initial work of a generation that is likely to dramatically change the ways we work together and more likely to realize the simple wisdom of Freud’s advice for a healthy life.

Rod Collins (@collinsrod) is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, 2014).

February 3, 2015

Payers And Provider Engagement…It Is More Than Sending Letters And Faxes!

by Samir Mistry, Pharm.D.

I have worked in the managed care payer space long enough to understand that most payers across the country struggle with provider engagement. But in their defense, provider engagement is not a simple process to manage, and for large national or multi-state payers this task is nearly impossible. There truly is significant untapped opportunity to lower pharmacy and medical costs and improve quality through better engagement with providers. Generally, most payers communicate with providers via letters, faxes and emails, but this is not considered engagement. Provider engagement, or any engagement for that matter, involves two-way conversations. Generally, when a payer makes a decision that involves providers, the provider input is left out, and the decision is communicated via letters or faxes. The only time a discussion occurs is when there is a written or verbal complaint that requires a response. Moving down the path of provider engagement is not simple, but ultimately the rewards are worth the effort. Ultimately, engagement can lead to adoption and endorsement, which can then drive more effective execution of strategies.

Break the Seal and Meet with a Provider, but Start with a Happy Provider

The worst situation possible is to initiate this process by working with an angry set of providers. Providers have to deal with many payers’ patients, maneuver through each plan’s prior authorizations for medications and procedures while trying to provide appropriate care to patients. It is a daunting process. To initiate contact with a provider, it is best to start with a provider who sees a large number of your plan’s members. It is also recommended that you meet the provider after business hours, away from work to prevent distractions. During the meeting, you want to focus on the following critical topics: discussing new strategies, asking for insight, and inquiring about the challenges and frustrations the provider is experiencing with the members. The most important component of the engagement is to follow-through on any topics discussed by scheduling follow-up meetings. Like any friendship, provider engagement involves maintaining contact, so make sure to keep regular meetings either in person or via phone.

The worst situation possible is to initiate this process by working with an angry set of providers. Providers have to deal with many payers’ patients, maneuver through each plan’s prior authorizations for medications and procedures while trying to provide appropriate care to patients. It is a daunting process. To initiate contact with a provider, it is best to start with a provider who sees a large number of your plan’s members. It is also recommended that you meet the provider after business hours, away from work to prevent distractions. During the meeting, you want to focus on the following critical topics: discussing new strategies, asking for insight, and inquiring about the challenges and frustrations the provider is experiencing with the members. The most important component of the engagement is to follow-through on any topics discussed by scheduling follow-up meetings. Like any friendship, provider engagement involves maintaining contact, so make sure to keep regular meetings either in person or via phone.

Don’t be Afraid to Ask for Recommendations and Try to Make Adjustments to Accommodate Recommendations where Possible

A well-executed strategy becomes more effective if there is endorsement from those impacted by the strategy. If you create a collaborative atmosphere during the engagement and are willing to accept fair suggestions from the providers, then there is a strong chance your program will have better results and fewer complaints. If you can provide a better provider experience to the strategy, then the adoption will be much faster, which will lead to more timely results.

Develop Regular Focus Groups of Your Highest Volume Practices

When implementing a large-scale program that will impact many providers, it is important to develop a focus group comprised of impacted providers. This will help in designing the best solution and executing it effectively. The focus group should consist of practicing providers who see many of your members and are respected in your region. They will provide a great deal of value in creating the program as well as endorsing your program once it is implemented. It is also important to continue holding these meetings as the program progresses in order to make adjustments to strategies, develop pay-for-performance programs, and potentially drive better results.

Engaging providers in a payer’s program development can create a sense of ownership, which is extremely important to the success of any initiative. Payers do not need to be Staff Model HMOs or Accountable Care Organizations to achieve high levels of provider engagement. Payers can be successful if they are committed to effectively and frequently engaging and communicating with the providers, appropriately using providers’ feedback and suggestions, and improving the overall provider experience. Engaged providers will be happier providers. They will deliver better care to your members, and collaborate to successfully implement your plan’s strategies. The ultimate winner of provider engagement is your plan’s membership.

Samir Mistry, Pharm.D. is a Senior Manager and the chief pharmacy expert in the healthcare practice at Optimity Advisors.

January 29, 2015

Financial Data Analytics: A Core Element Of Business Strategy

by Vipul Parekh

In today’s complex business environment, financial services firms are collecting data from numerous sources both internally through transactional systems, operations workflows, and application logs. as well as externally through customer interactions and social networking sites. Additionally, in the regulatory arena, new financial oversight rules have expanded the categories of data that financial services firms need to capture, manage and disseminate. Examples include the capital requirements and risk analytics needs for BASEL III, Dodd Frank, and EU Solvency II regulations. Large financial organizations are also facing constant pressure to achieve operational efficiency and reduce operating costs due to thinner margins.

Overall, industry wide regulatory developments, increased sensitivity to regulatory breaches, pressure to reduce costs, recent technology advancements, and customer behavior are all converging to stage big challenges and significant opportunities to enable data driven decisions for financial services firms. The best way for financial services firms to meet this challenge is by providing efficient data analytics capabilities to key decision makers, creating an excellent opportunity to start treating financial data analytics as a core element of business strategy.

Overall, industry wide regulatory developments, increased sensitivity to regulatory breaches, pressure to reduce costs, recent technology advancements, and customer behavior are all converging to stage big challenges and significant opportunities to enable data driven decisions for financial services firms. The best way for financial services firms to meet this challenge is by providing efficient data analytics capabilities to key decision makers, creating an excellent opportunity to start treating financial data analytics as a core element of business strategy.

Reality of Current State

In reality, however, key decision makers and operations staff in most financial services firms still rely heavily on traditional reports-based analytics solutions. These solutions mostly generate reports with historical data, with users performing manual analysis using tactical dashboards and Excel spreadsheets. Additionally, with the rapid rate of increase in data volume, these solutions have several key bottlenecks:

3 Vs Challenge

The volume, velocity and variety of data have far exceeded the capacity of manual analysis, degrading the strength of traditional databases.

Lack of Metadata and Data Quality

The data attributes are not well tagged and analyzed, in addition to having significant quality issues that make them difficult to use for analytics.

Storage Space Issues

Most of the reports have fixed sets of attributes and overlapping information, causing unnecessary waste of storage space. This is becoming a very big issue considering the amount of data collected by financial services firms.

Limited Insight

Historical data only allow descriptive analyses (what has happened) by looking at ad-hoc analysis or dashboards. There is no easy way to perform diagnostics analytics (why it has happened), predictive analytics (what will happen) and prescriptive analysis (what should happen) on data, which is key to enabling more effective data driven decisions.

Lack of standardization

The data analysis and metrics used for decision-making are ad-hoc and lack standardization at the department or firm level, resulting into different interpretations of same data attributes.

Flexibility Issues

Expansion of reports to add more information or generate new metrics requires enhancements and further developments by technology teams.

Bringing Change

So, how do firms drive their data analytics initiatives for better decision-making? At the highest level, the key is to approach data analytics as an enterprise-wide initiative in a coordinated manner. That means business decision makers from various departments need to clearly articulate key performance metrics and requirements that will enable better decisions. The organizations should establish an enterprise-wide data analytics program to build a framework that brings key people (data experts, decision makers, IT teams) and processes (data governance, quality, analytics) together. The framework should broadly cover standardization of key performance metrics, data quality rules, data governance processes, data dictionary, analytical data model, metadata and visualization to bring consistency in implementation across all departments.

The data framework should support multiple decisions across various departments. For example, observation of transactions volume spikes would be important for operations in studying underlying market events as well as potential capital and counterparty risks. Whereas the IT team may be looking to analyze system performance and capacity needs on high volume days. So, it is important to recognize nuances by building flexibility into the framework rather than trying a one size fits all style solution for all departments. Additional points to work towards include:

Get to know your data

Catalog data sources and tag data housed across all business lines to develop enterprise-wide taxonomy and data dictionaries.

Data Quality

Bad data leads to bad business decisions. So, having better data governance processes to produce better quality data plays a crucial role in usability and success of data analytics initiatives.

Running data quality initiatives with data experts from each department can help immensely in defining key quality metrics, identify root cause of quality issues, provide feedback in data governance processes, and improve overall data quality.

Analytics Model

Having a separate data model for analytics can help immensely in adding flexibility required for data analytics initiatives.

Selection of data attributes, understanding data quality needs, identifying right data sets, and correct formatting of data are all crucial in designing a flexible analytical data model.

Support for various views of data and different analytics methodologies are important as decision makers interpret data differently.

Roles and Responsibilities

Clearly define the roles and responsibilities of sponsors and all stakeholders involved in data analytics initiatives. The success of an initiative depends heavily on close collaboration between business stakeholders, data experts, data modelers, and technology teams.

New Skills

Data driven decisions and analytics solutions require resources with better artistic, graphical, and analytical skills. The firms can hire data analysts with specific skills from outside or train existing data experts to develop required skills.

Analytics User Interface

Technology teams should focus on building infrastructure that allow data experts and decision makers to perform ad-hoc analysis on underlying data, create new metrics visualizations to best represent data, and the ability to drill down in detail as required.

The UI should have provisions to perform what-if analysis and forecast varying outcome of performance metrics.

Iterative Development

Data analytics solution development is very iterative in nature. Most of the requirements change significantly after the first phase when the business starts analyzing data and builds deeper insights. Careful planning should be done to easily add or update functionality while limiting throwaway work.

Data Security

Processes need to be in place to limit liberal use of data, as well as to enforce roles- and responsibilities-based entitlements to control who has access to data, as well as what and how much can be seen in order to avoid any violation of sensitive data.

Bottom Line

With the increasing importance of data quality and regulatory developments, the challenges financial services firms face are creating the need for maintaining quality data in-house. Ultimately, having sophisticated data analytics to produce high quality data can give deeper insights into new opportunities through a more comprehensive understanding of market trends, customer behavior, risks assessment, capital efficiency, and operations efficiency, as well as providing the ability to perform futuristic analysis based on what-if scenarios. Data is truly a sizable and important asset and having strong data analytics capabilities as a core element of business strategy will be the key to the future success for financial services firms.

Vipul Parekh is a leader of Financial Services practices at Optimity Advisors.

January 22, 2015

The Problem With Empowerment

by Rod Collins

Many, if not most, businesses today share a common and troubling problem: The vast majority of the people who work for their organizations are disengaged. According to a recent Gallup study, worldwide, a meager 13 percent of workers are engaged at work. In other words, only one out of every eight employees are motivated to make positive contributions to their organizations. While 63 percent of workers described themselves as “not engaged” in the workplace, an alarming 24 percent are “actively disengaged” and may actually be thwarting the productivity of their companies.

Although there are regional differences, no area is experiencing outstanding results when it comes to leveraging the talents of their workers. In the top-performing region—the United States and Canada—the level of engaged workers is still a dismally low 29 percent. These results are not good news for business leaders struggling to keep pace with fast-moving markets that are changing much faster than their organizations. If they are to have any hope of closing this change gap, business leaders are going to need to find a way to get the vast majority of their employees committed to the success of their companies.

A Limited Solution

One solution that some business leaders are embracing is to retrain their managers in the principles and practices of empowerment. The thinking is that, if managers get better at including workers in defining what needs to be done and how to do the work, the level of engagement will dramatically improve. While the logic seems to makes sense and the practices often produce short-term results, empowerment is usually limited as a long-term worker engagement strategy because it is overly dependent upon the voluntary cooperation of the managers. Thus, micromanagers who succeed empowering basses can undo the benefits of engagement in a matter of months, or even days.

The problem with empowerment is that it assumes that hierarchies are a given. The voluntary delegation of power is something that can only happen in a hierarchy. If business leaders want a reliable long-term strategy for fostering high levels of worker engagement, Doug Kirkpatrick, the author of Beyond Empowerment: The Age of the Self-Managed Organization, recommends they begin by eliminating the great enabler of worker disengagement: the corporate hierarchy. Kirkpatrick points out that “employee empowerment” implies that one person has the authority to transfer power to another person. It also implies that “what is given can be taken away,” which is why Kirkpatrick prefers what he calls “self-management” over empowerment as a more effective organizational strategy for enabling worker engagement.

Beyond Empowerment

Beyond Empowerment is a fictionalized account of a company that designs itself as a peer-to-peer network rather than a top-down hierarchy. It is based on the true story of the innovative management model used by the California company Morning Star to propel itself into becoming the world’s largest tomato processor. Kirkpatrick makes a convincing case that self-management is more effective than hierarchical management because it moves beyond empowerment by vesting organizational power in those who actually do the work. In self-managed organizations, every worker is a manager because very worker is directly accountable for delivering value to customers. That’s why the workers at Morning Star are not called “employees,” but rather “colleagues.” Employees are people who work for others for pay, while colleagues are people who unite with others in a common pursuit.

Beyond Empowerment is a fictionalized account of a company that designs itself as a peer-to-peer network rather than a top-down hierarchy. It is based on the true story of the innovative management model used by the California company Morning Star to propel itself into becoming the world’s largest tomato processor. Kirkpatrick makes a convincing case that self-management is more effective than hierarchical management because it moves beyond empowerment by vesting organizational power in those who actually do the work. In self-managed organizations, every worker is a manager because very worker is directly accountable for delivering value to customers. That’s why the workers at Morning Star are not called “employees,” but rather “colleagues.” Employees are people who work for others for pay, while colleagues are people who unite with others in a common pursuit.

Self-management is based upon two primary principles. The first is that “people should not use force against others or their property.” In other words, no one should have the authority to unilaterally impose his or her will upon another person in the company. The second is that “people should keep their commitments to others.” This means that workers are accountable to their peers in meaningful ways. Put simply, self-management is a peer-to-peer structure built upon two core values: freedom and responsibility. Workers are free to associate with anyone else in the company in creating value, and they are free from the coercive behavior that is taken as a given in many traditional management arrangements. With this freedom comes high expectations for acting responsibly on behalf of the customers served by the company. Thus, colleagues are responsible for negotiating internal commitments, measuring their performance against those agreements, and ultimately delivering what they have promised.

Core Values

Freedom is a core value because, according to Kirkpatrick, freedom is “the way humans are wired.” People want to have a say in what they do; they want to help create a world that is better for themselves and others through the work they do together. This is what engagement is all about: having the freedom to shape what we do and collaborate with colleagues to make a real difference in the lives of those we serve. Few workers in traditional organizations have this freedom, which may explain why their engagement levels are dreadfully low.

Responsibility is a core value because, without it, nothing would be accomplished. Self-management is not a structureless approach to designing an organization, but rather a different—and an arguably far more effective—way to design how work gets done. At Morning Star, the primary tool for aligning responsibilities is the “Colleague Letter of Understanding.” Before the beginning of each year, colleagues in each business unit gather to discuss business strategy for the upcoming year and negotiate agreements around measurable deliverables that form the basis of the shared understanding that directs the coordination of the individual efforts of each of the workers. Throughout the year, detailed business information is updated twice a month so that workers can track their own as well as their colleagues’ metrics. This metrics-based peer accountability structure is the foundation for both high worker engagement and sustained business success.

A Better Solution

If business leaders are serious about improving and sustaining high levels of worker engagement, they should reconsider if they are contemplating an employee empowerment initiative. Such initiatives are likely to go the route of other managerial “flavors of the month” for the simple reason that when managers have the authority to give, they also have the authority to take away. Solidifying high worker engagement into the fundamental DNA of the organization will not be accomplished by incremental organizational philosophies that can easily be undone on a managerial whim. Developing robust high engagement work cultures requires a fundamental structural change in the way that power works in organizations. Rather than attempting to build an empowered hierarchy—which is probably an oxymoron—a better solution for business leaders would be to follow Kirkpatrick’s advice by redesigning their organizations as peer-to-peer networks where no one has the authority to empower or disempower anyone else because power comes from being connected rather than from being in charge.

Rod Collins (@collinsrod) is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, 2014).

January 19, 2015

Competition And Consumer Choice In Health Insurance Marketplaces: Reading The Tea Leaves For 2015 And Beyond

by Vince Volpe

As we enter the final stretch in this year’s open enrollment season, it’s clear that 2015 will be a landmark year in the history of healthcare reform. Competition among insurers in the exchanges is resulting in a highly dynamic marketplace with new options for many consumers. While some insurers are raising rates, others are reducing rates to gain share, expanding their product offerings, and entering new markets. Although these are promising developments, the reality is that there is long way to go before we have a true consumer-driven health market. To be successful in this rapidly evolving landscape, insurers must optimize their strategies to the market today, while building entirely new capabilities necessary to shape the future.

A New Consumer-Driven Marketplace

While competition and choice is certainly good for the consumer, the unanswered question is how they will actually respond to these new choices. Will they take the time to research options and make an informed decision, or will they simply select the plan with the lowest premium? Alternatively, consumers might forego shopping entirely, with automatic re-enrollment the default option in most states. The answer to this question carries significant implications for both insurers and policy-makers. Indeed, the Obama Administration has been actively urging consumers to shop around to ensure they get the best value. According to HHS, over 70 percent of 2014 enrollees could save on premiums by selecting a new plan.

For insurers, it is critical to understand consumers’ sensitivity to premium price and willingness to consider tradeoffs in benefit design such as higher deductibles or more limited provider networks. Since most Americans have historically had healthcare benefits provided by their employer or the government, consumer-purchasing behavior is less understood than it is for other goods and services. To understand how these dynamics might play out in 2015, Optimity conducted a market-level analysis to illustrate the choices and trade-offs that individual consumers are being faced with during open enrollment.

The View from the Market

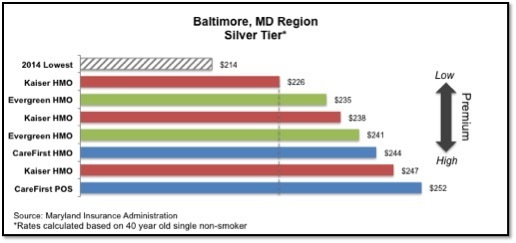

The state of Maryland offers a microcosm of the forces at play across the country. In 2014, CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield captured 95% of all enrollments. The state’s troubled exchange website, eventually replaced, complicated matters for insurers seeking a foothold in the market, such as Evergreen Health CO-OP. However, the competitive landscape looks quite different in 2015. Citing a sicker than expected population, CareFirst increased rates an average of 9 to 17 percent, whereas Kaiser Permanente and Evergreen Health CO-OP both reduced rates.

In the Baltimore metro area, CareFirst offered the lowest priced plan in 2014 in the Silver metal tier (nationally the most popular with ~65% of enrollees). However, in 2015 its plans will fall to fifth and seventh lowest. As a result, consumers who selected the lowest priced plan last year could save 7 to 10 percent by switching from their current plan to Kaiser or Evergreen. The takeaway is that these consumers must now decide how much they value keeping their existing health plan and what price they are willing to accept to avoid the pain of switching insurers.

Understanding the Consumer

New consumers on the exchanges are highly sensitive to price, as evidenced by the fact that 65 percent of enrollees in 2014 selected the lowest or second lowest priced plan. A recent McKinsey survey found that 48 percent of consumers already intending to renew their current coverage would shop around if faced with a premium increase of 5 to 10 percent, and this increases to 70 percent if the increase were greater than 10 percent.

However, once enrolled in a health plan, the evidence suggests that consumers may be quite “sticky” and less willing to switch plans, even if doing so would provide significant savings. A recent study of the Medicare Part D program found that 87 percent of enrollees kept their existing drug plan each year, even when most had cheaper options available. Perhaps most significant, many enrollees may not shop around at all. As of December 30, HHS estimated that only 40 percent of 2014 enrollees had returned to Healthcare.gov to make a selection for 2015. As CMS and individual states continue to adjust auto-reenrollment policies, the implications for consumers and insurers may be highly meaningful if these trends continue.

Among those consumers who do shop around, there is an increasing willingness to consider new plan design options, such as limited physician networks, provided the premium savings is sufficient to justify the tradeoff. A recent survey from Liazon, a private exchange provider, found 83 percent of consumers were willing to consider a more restrictive network for less expensive premiums. While historically not popular with plan sponsors, insurers are increasingly using narrow networks as a lever to control costs. Since consumers selecting these plans may have to change their current providers, transparency and engagement will be critical success factors in ensuring the acceptance of these plans by both consumers and regulators.

The Bottom Line

Although the post-ACA individual market is still in its infancy, 2015 is shaping up to be a landmark year in the evolution towards a true consumer-driven healthcare market. Insurers are now competing vigorously on price and introducing new product innovations that will ultimately create value for consumers. While these developments are encouraging, the promise of a consumer-driven marketplace will not be realized unless consumers themselves become more engaged and informed purchasers of health insurance. For insurers seeking to grow in this market, it is crucial to develop a sophisticated approach to understanding consumer behavior and to tailor pricing and product strategies accordingly. Ultimately, the biggest winners will be those who not only understand and deliver on the needs of their customers today, but also effectively influence and shape their expectations of what the healthcare products of tomorrow can and should be.

Vince Volpe is a Senior Associate at Optimity Advisors.

January 13, 2015

State Of DAM 2015

by Bridget Garraty & Reid Rousseau

As the Digital Asset Management (DAM) marketplace changes and grows to meet new expectations, let’s start 2015 the right way by reaffirming what DAM is. DAM consists of the management tasks and technological functionality designed to enhance the inventory, control, and distribution of digital assets for the ingestion, annotation, cataloguing, storage, retrieval, and distribution of digital assets that are used and reused in marketing or business operations. The unique and distinguishing aspect of DAM, versus other approaches, is that it can serve as the single source of truth for digital assets that demand use and reuse via file format conversions and accessible discovery.

The Market for DAM

The market for DAM systems is convoluted by alternative system offerings (workflow, content management, etc.) often broadly labeled as DAM.

Enter DAM Vendors. The DAM market is filled with DAM sales representatives offering a range of solutions from genuine cutting edge DAM systems to systems with pieces of DAM behavior mixed with other functionality and billed simply as a “DAM System.”

Enter corporate DAM buyers. Companies often mistake a business need for a comprehensive DAM strategy for a simple need capable of being fulfilled by an off the shelf technology system. While DAM vendors provide one piece of the puzzle—technology—a DAM strategy must incorporate more than that; it must weave people, process and technology into a comprehensive DAM approach.

The Right Recipe: People and Process, Then Technology

Enter 2015, the time to assess your DAM strategy. Are you still using a document management site like SharePoint or a local shared drive as your “DAM solution”? Are you just beginning to identify a need for DAM in your organization? To avoid missteps and find the right system, it is important to first start with the people and process components of your DAM strategy. In order to avoid DAM implementation pitfalls, you need to understand and define your users, integration and business needs, and then shop for your DAM system. You cannot shop for an oven (technology) before knowing who you’re cooking for (people) and what recipe (process) you’re following.

Enter 2015, the time to assess your DAM strategy. Are you still using a document management site like SharePoint or a local shared drive as your “DAM solution”? Are you just beginning to identify a need for DAM in your organization? To avoid missteps and find the right system, it is important to first start with the people and process components of your DAM strategy. In order to avoid DAM implementation pitfalls, you need to understand and define your users, integration and business needs, and then shop for your DAM system. You cannot shop for an oven (technology) before knowing who you’re cooking for (people) and what recipe (process) you’re following.

The 2015 Vision

The people and process elements of a successful DAM ecosystem are driving what’s to come in 2015 and beyond. Vendors are pushing the boundaries of their user interface development with cleaner, more intuitive user experiences, to align with expectations set by consumer level offerings.

Enter 2015 system users. Expectations fueled by the daily experiences with Google, online shopping, and consumer driven social media sites set a high bar for search experience. In their personal lives, these users expect to find a product in 3 clicks, they expect progress within 10 seconds of searching, and they demand intuitive design. These expectations typically exceed DAM technology offerings. Consumer technology is somewhat different for corporate / enterprise / business technology. However, will this change over time?

The middle ground between consumer level expectation and realistic DAM technology offerings can be reached by complementing intuitive user interface solutions from vendors with strong process in the form of user education. Educational initiatives focused on metadata’s critical role in search and search functionality in typical DAM systems, with some explanation of how DAM system search differs from “Google-esque” search, will help set realistic user expectations and empower users themselves to improve the system.

2015 is the year to start thinking of DAM as more than an IT solution. The best DAM strategy is a harmony of people, process and technology.

Bridget Garraty is a Senior Associate at Optimity Advsiors.

Reid Rousseau is a Senior Associate at Optimity Advisors.

State of DAM 2015

by Bridget Garraty & Reid Rousseau

As the Digital Asset Management (DAM) marketplace changes and grows to meet new expectations, let’s start 2015 the right way by reaffirming what DAM is. DAM consists of the management tasks and technological functionality designed to enhance the inventory, control, and distribution of digital assets for the ingestion, annotation, cataloguing, storage, retrieval, and distribution of digital assets that are used and reused in marketing or business operations. The unique and distinguishing aspect of DAM, versus other approaches, is that it can serve as the single source of truth for digital assets that demand use and reuse via file format conversions and accessible discovery.

The Market for DAM

The market for DAM systems is convoluted by alternative system offerings (workflow, content management, etc.) often broadly labeled as DAM.

Enter DAM Vendors. The DAM market is filled with DAM sales representatives offering a range of solutions from genuine cutting edge DAM systems to systems with pieces of DAM behavior mixed with other functionality and billed simply as a “DAM System.”

Enter corporate DAM buyers. Companies often mistake a business need for a comprehensive DAM strategy for a simple need capable of being fulfilled by an off the shelf technology system. While DAM vendors provide one piece of the puzzle—technology—a DAM strategy must incorporate more than that; it must weave people, process and technology into a comprehensive DAM approach.

The Right Recipe: People and Process, Then Technology

Enter 2015, the time to assess your DAM strategy. Are you still using a document management site like SharePoint or a local shared drive as your “DAM solution”? Are you just beginning to identify a need for DAM in your organization? To avoid missteps and find the right system, it is important to first start with the people and process components of your DAM strategy. In order to avoid DAM implementation pitfalls, you need to understand and define your users, integration and business needs, and then shop for your DAM system. You cannot shop for an oven (technology) before knowing who you’re cooking for (people) and what recipe (process) you’re following.

Enter 2015, the time to assess your DAM strategy. Are you still using a document management site like SharePoint or a local shared drive as your “DAM solution”? Are you just beginning to identify a need for DAM in your organization? To avoid missteps and find the right system, it is important to first start with the people and process components of your DAM strategy. In order to avoid DAM implementation pitfalls, you need to understand and define your users, integration and business needs, and then shop for your DAM system. You cannot shop for an oven (technology) before knowing who you’re cooking for (people) and what recipe (process) you’re following.

The 2015 Vision

The people and process elements of a successful DAM ecosystem are driving what’s to come in 2015 and beyond. Vendors are pushing the boundaries of their user interface development with cleaner, more intuitive user experiences, to align with expectations set by consumer level offerings.

Enter 2015 system users. Expectations fueled by the daily experiences with Google, online shopping, and consumer driven social media sites set a high bar for search experience. In their personal lives, these users expect to find a product in 3 clicks, they expect progress within 10 seconds of searching, and they demand intuitive design. These expectations typically exceed DAM technology offerings. Consumer technology is somewhat different for corporate / enterprise / business technology. However, will this change over time?

The middle ground between consumer level expectation and realistic DAM technology offerings can be reached by complementing intuitive user interface solutions from vendors with strong process in the form of user education. Educational initiatives focused on metadata’s critical role in search and search functionality in typical DAM systems, with some explanation of how DAM system search differs from “Google-esque” search, will help set realistic user expectations and empower users themselves to improve the system.

2015 is the year to start thinking of DAM as more than an IT solution. The best DAM strategy is a harmony of people, process and technology.

Bridget Garrity i a Senior Associate at Optimity Advsiors.

Reid Rouseau is a Senior Associate at Optimity Advisors

January 6, 2015

Pharmaceutical Companies And Payer Relationships: An Approach To Success!

by Samir Mistry, Pharm.D.

Pharmaceutical companies depend a great deal on their relationships with payers to leverage formulary access for their branded products. Having strong relationships with payers can allow a pharmaceutical company the ability to present clinical and safety data on their products, understand the formulary placement of their products compared to brand and generic competitors, present and leverage value added programs, and most importantly, have an open line of communication with key clinical leadership within payer organizations. More often than not, representatives from pharmaceutical companies underestimate the importance of these relationships, and this can be potentially harmful to the company. Not having strong relationships with payers could lead to unfortunate situations related to negative formulary changes or clinical edits placed on products that can negatively impact the market share of the company’s products. These changes could be related to recommendations from the payer’s pharmacy benefit manager (PBM), negotiations made by a competitor product’s company with the payer, or the entrance of a new generic product within a  brand drug’s therapeutic category. Having a strong relationship with a payer’s clinical leadership team and maintaining a proactive communication channel can either open opportunities for product advancement or prevent negative impact to a drug’s formulary status or market share penetration. The following are “best practices” and “key insights” account executives can use to develop and maintain relationships with payers.

brand drug’s therapeutic category. Having a strong relationship with a payer’s clinical leadership team and maintaining a proactive communication channel can either open opportunities for product advancement or prevent negative impact to a drug’s formulary status or market share penetration. The following are “best practices” and “key insights” account executives can use to develop and maintain relationships with payers.

Know the Key Contacts and Leadership

The availability of online resources such as LinkedIn or Google helps pharmaceutical companies identify the clinical leadership within the payers’ organizations. These leaders can be Chief Medical Officers (CMO), Medical Directors, Vice Presidents (VP), Directors of Pharmacy or Clinical Pharmacists. It is a good practice to review the leaders’ LinkedIn profiles to better understand their work history and experience, which could provide important insights into how they think and what approach to use when presenting products.

Schedule Meetings Well in Advance

Scheduling meetings with a CMO or VP of Pharmacy can be a very frustrating experience. They are extremely busy individuals and their calendars are often completely booked with meetings. This can be a good test of one’s patience, so it’s a good practice to plan ahead. If there are critical timelines for meetings with a VP of Pharmacy, the best idea is to book at least one or two months in advance. It is important to consider that the average pharmaceutical account executive is competing with at least five other pharmaceutical manufacturers for potentially a one-hour weekly time slot at best. Some pharmacy departments do allocate time for meetings with pharmaceutical companies, but this is not a normal process. It is equally important to build a good relationship with the executive assistants for the CMO or VP of Pharmacy. From personal experience as a VP of Pharmacy for a very large payer, the executive assistant is either the biggest ally or the worst enemy for any account executive to have access to meetings. It is a good practice to always act professionally and be flexible with the dates and times provided.

Do Your Research

A true best practice when meeting with a payer’s CMO or VP of Pharmacy is to do the appropriate research before any meeting. These are some key areas to understand:

What are the demographics of the payer, such as lines or business, lives, competitors and any recent news related to the payer or its competitors?

What is the contracted PBM? And do they use the PBM’s national formulary or a custom formulary?

What is the status of your product on their formulary (ies)? And the status of your competitors’ products?

Are there any clinical edits on your product(s), and your competitors’ products?

Walking into any meeting completely unprepared could be costly. It is important to not waste anyone’s time, doing so could significantly delay or even prevent future meetings. Being knowledgeable of the payer truly helps building the relationship with the leadership. They will have more respect for the account executives and will be more willing to share information than with someone who is unprepared.

No Surprises

This topic is a huge “pet peeve” for CMOs and VPs of Pharmacy. If a pharmaceutical company has scheduled a meeting, the worst thing to do is to have a surprise visitor or surprise topic of discussion. If there is a need to invite a new individual or discuss another topic, the best practice is to request this prior to the meeting and confirm that there is no issue with it. Ultimately, the best practice for a meeting would be to provide a list of attendees along with the purpose of the meeting during the time of scheduling, and then adhering to the agenda.

Graciously Take Bad News

For any pharmaceutical account executive, nothing is worse than being made aware that your product was removed from formulary or placed on a higher copay tier than a competitor’s product. More often than not, this leads to an internal meltdown and issuance of blame. There are many reasons for negative formulary decisions, and most of them are not within the control of an account executive. The best practice in this type of situation is to have a constructive discussion with the pharmacy leadership related to why the decision was made, to see if there is any opportunity to reverse the decision, and to learn whether or not the change could have been prevented. The worst response would be complaining about the change, reaching out to other members of leadership, or creating tactics and roadblocks to challenge the decision. I have seen many account executives essentially “black listed” by payers and unable to meet with any clinical leadership because of unprofessional behavior.

After many years working in payer leadership, I have seen the best and the worst of representatives from pharmaceutical companies. The best recommendation I can provide account executives is to focus on building and maintaining a strong relationship with the clinical leadership. Those who have maintained relationships are never surprised with negative decisions on their products and are usually granted the meetings they need. Those who fail to maintain strong relationships will not be treated with the same level of respect. There are two main premises for the above best practices: Be respectful and be prepared.

If you would like to learn more about the dynamics of the managed care market, Optimity Advisors routinely conducts a “Managed Care Pharmacy Workshop” to educate Managed Market Representatives on the forces and players shaping the Managed Care landscape. Our workshop provides insights into the challenges and needs of pharmaceutical customers (payers, patients, and health care providers), the factors driving payers’ formulary decisions, and the opportunities in the space of Managed Care Pharmacy.

Samir Mistry, Pharm.D. is a Senior Manager and the chief pharmacy expert in the healthcare practice at Optimity Advisors.

Rod Collins's Blog

- Rod Collins's profile

- 2 followers