Rod Collins's Blog, page 17

June 17, 2014

The Enablers of Great Work Cultures

By Rod Collins

The recent mismanagement scandals that have plagued General Motors and the Veterans Administration are unfortunate examples of what happens when work cultures go awry. The silence that prevailed among the many who were aware of the deep problems in both of these organizations offends our human sensibilities. Why didn’t more people speak up sooner? How could so many passively sit on the sidelines while people literally were dying because of their organizations’ flawed operations? What caused these two organizations to create cultures that seemed to bring out the worst in so many people? And how can we make it better so organizations are designed to bring out the very best in all their workers?

For more than fifty years, we have known that participative management—where managers deeply respect their employees and empower them to do their very best work—is far superior to top-down, “keep your mouth shut and do what you’re told” command-and-control management. Beginning in the 1960s with Douglas McGregor’s identification of Theory X and Theory Y and with Abraham Maslow’s penetrating insights into the higher reaches of human nature, we have understood that when managers involve employees in defining the work to be done, the workers are more engaged in their efforts and more committed to excellent performance. Unfortunately, this knowledge has had little real impact on organizations. When it comes to implementing the insights of the human relations discipline spawned by McGregor and Maslow, management’s accommodations, until recently, have been far more about style than substance.

Creating Great Workplaces

Despite the recent misadventures of GM and the VA, substantive change is beginning to take hold in some management circles, and it’s not coming from the insights of the organizational specialists or the usual management players, but rather from the innovative practices of a rather unlikely group: engineers. The current #1 company on Fortune magazine’s list of the “Best Companies to Work For” was founded by two engineers, and the world’s first bossless company—W. L. Gore and Associates, a perennial presence on the Fortune list—was also started by an engineer. The Agile Management movement, which has revolutionized software development by leveraging the power of collaboration, was started by a group of software engineers. And it was an engineer who created the first wiki, which became popularized with the rapid growth of Wikipedia. How is it that engineers, who are not normally known as the champions of the “touchy-feely” have had more success than the human relationship experts when it comes to effecting real change in the way management works?

One group that may be interested in the answer to this question is the pioneers who have banded together to champion the Great Work Cultures initiative. Their mission is “to create deep, broad workplace culture change so that all workers can expect and experience a respectful work environment.” The group’s tagline is “Moving from Command and Control to Respect and Empower.” Their hope is that by banding together, they will create the gravitas that will result in a new norm for workplace cultures. Implicit in this notion is the expectation that this new norm will radically transform the way individual leaders think in leading the work efforts of their employees. As the group pursues its noble purpose of reinventing management on a large scale, it may benefit from understanding how the engineers have been successful in bringing substantive change to management.

Discovering the Key to Great Performance

About the same time that McGregor and Maslow were expanding our understanding about human motivation in organizational work, W. Edwards Deming was introducing systems thinking into the practice of management. An engineer by training, Deming recognized that the dysfunctional behavior that often plagues top-down organizations is more likely to result from the dynamics of the overall management system than from the behavior of individual managers. Thus, he cautioned managers that when most of the people engage in the wrong behavior most of the time, the problem is more likely the system not the people. This may explain why the engineers have been so successful in creating organizations known for their great cultures.

Engineers tend to think in terms of systems. They understand that system design is the key to great performance. When Sergey Brin and Larry Page started Google, they didn’t just build a great search engine; they also built a great company. As they designed their organization, they were very mindful that they were not going to build another top down bureaucracy that amplified the voices of the few and silenced the many. Instead, they would build an organization that, like their search engine, would leverage the collective intelligence of everyone in their organization.

Keeping Pace with Accelerating Change

Brin and Page also understood that the fundamental work of business leaders was being transformed by the sudden need to keep pace with the speed of accelerating change. The work of the business leader can be summed up in three words: strategy and execution. Whether business leaders succeed or fail depends on how well they perform these two fundamental management tasks. For over a century, strategy was accomplished by planning and the key to execution was effective control. Planning and control can be effective organizing principles when the world is relatively stable. They may not necessarily work best, but they usually work well enough when change is incremental.

However, when the pace of change accelerates, fixed plans and rigid controls are poor guides for navigating the turbulent waters of constantly shifting seas. Iterative adaptability and creative collaboration are better organizing principles in times of great change. In designing Google’s organization, Brin and Page shifted the fundamental dynamics of strategy and execution from “Plan and Control” to “Iterate and Co-create.” As a consequence, their new organization became more of a peer-to-peer network than a top-down hierarchy. With practices such as a 60-to-1 ratio of managers to workers and its well-publicized 20% rule—employees spend twenty percent of their time on self-managed projects—Google’s organizational system naturally reinforces iteration and co-creation.

Building Networks, Not Hierarchies

When organizations are designed as networks, advocating for respect and empowerment is unnecessary because, in networks, respect is earned rather than ascribed, and power comes from being connected rather than from being in charge. One of the problems with the notion of empowerment is that it assumes that hierarchies are a given. The voluntary delegation of power from a person in authority to his or her subordinates is something that can only happen in a hierarchy. In networks where power stems from one’s initiative to make connections, the notion that one has the capacity to ascribe power from one person to another is irrelevant.

Respect and empowerment are not the enablers of great cultures; they are the natural byproducts of a great management system. The true enablers of great cultures are the two dynamics that define the peer-to-peer network: iterate and co-create. As the leaders at GM and the VA seek to turnaround their troubled organizations and as the members of the Great Cultures Initiative pursue their noble cause, they might all benefit from the management wisdom of the engineers who learned that when you want most of the people to engage in the right behavior most of the time, you build a network, not a hierarchy.

Rod Collins (@collinsrod) is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, 2014).

June 10, 2014

Does Going “Bossless” Create an Accountability Vacuum?

By Rod Collins

In December 2013, Zappos created quite a buzz in the business community when they announced that, by the end of 2014, they would go “bossless” and adopt an egalitarian organizational model called holacracy. In their new organization, there will be no titles, no managers, and no hierarchy. Instead their organization will be transformed into a network of approximately 400 self-managed teams where people can assume various roles based upon the changing needs of their particular projects.

While Zappos is not the first company to go bossless—W. L. Gore and Associates, the makers of Gore-Tex, has been bossless since it inception in 1958—it’s the first company to draw broad attention to an alternative management model that, while highly successful, has nevertheless remained hidden in plain sight for literally decades.

In a recent article in the Gallup Business Journal, Elizabeth Kampf questions the wisdom of Zappos’ decision by speculating that employee engagement—which correlates highly with positive business outcomes—is likely to suffer in the absence of traditional managers. Kampf’s doubts about holacracy are based upon Gallup’s extensive body of research, which identifies managers as the essential variable in employee engagement. Kampf postulates that the elimination of managers at Zappos could lead to an accountability vacuum that would be detrimental to employee engagement, and in turn, future business outcomes. Kampf suggests that, rather than eliminating their managers, Zappos’ best move might be to replace bad managers with great ones.

Kampf’s suggestion, however, might be shortsighted because, while Gallup’s research is indeed extensive, it may nevertheless be limited. By her own admission, Kampf acknowledges that Gallup hasn’t studied the holacracy model. In all likelihood, Gallup’s research presents a picture of what works and what doesn’t work in the typical hierarchical organization. Because hierarchies, by design, are populated by an array of supervisors—all of whom have the positional authority to kill good ideas and keep bad ideas alive—it is not surprising that Gallup recently reported only 30 percent of U.S. workers and 13 percent of workers worldwide are engaged at work. It’s clear that traditional organizations have an engagement problem.

Kampf also notes that Gallup’s research shows that great managers are rare. In other words, in the typical organization, great managers are the exception rather than the rule. This brings to mind the saying attributed to W. Edwards Deming that when most of the people engage in the wrong behavior most of the time, the problem is the system not the people. Perhaps great managers are people who have learned how to work around a bad system. If that’s the case, great managers will always remain rare, and suggesting to companies that the pathway to better managers is to recruit from this very limited pool doesn’t alleviate the larger employee engagement problem. If the prevalent management system consistently spawns bad managers, perhaps a better solution is a better system.

Kampf incorrectly states that, with more than 3,000 employees, Zappos is the largest company yet to embrace going bossless and implies that the online shoe retailer may be moving into uncharted territory. However, W. L. Gore and Associates, which today has over 10,000 employees in 30 countries around the world, has been a very successful self-managed company for over 56 years. Gore has made a profit in every year of its existence and is a permanent fixture on Fortune’s list of the “Best Companies To Work For.” Employee engagement is not a problem at Gore. Nor is there an accountability vacuum.

When Bill Gore decided in 1958 that he would build a company without managers, he knew it could only work if people were directly accountable for the company’s results. This meant that people had to have an incentive to do more rather than less work and the right work rather than the wrong work. His solution was to hold people accountable to their peers by creating a performance system where people evaluated and were evaluated by 20 colleagues. Based on Gore’s longstanding record of success, one could argue that accountability to many peers is more effective than accountability to single supervisors.

Zappos isn’t embracing holacracy because they have bad managers or an employee engagement problem. At number 38 on Fortune’s “Best Company To Work For” list, it’s clear that employee engagement is not an issue. Zappos is adopting holacracy as a natural part of its evolution. Since its founding, it has actively spurned traditional management practices and has placed a high value on building the outstanding culture for which it is well-known. Zappos is going bossless because it understands that if you want most of the people to engage in the right behavior most of the time, you build and continually improve a great system.

Rod Collins (@collinsrod) is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, 2014).

June 3, 2014

Change Management for DAM

By John Horodyski

“It may be hard for an egg to turn into a bird: it would be a jolly sight harder for it to learn to fly while remaining an egg. We are like eggs at present. And you cannot go on indefinitely being just an ordinary, decent egg. We must be hatched or go bad.” — C.S. Lewis

The month of May brings with it great evidence of change. Spring’s effects finally can be seen in the colorful blooms in our gardens. Everything smells better with the newfound flora. Everything feels better with the welcome change to warmer weather. And the students graduating from colleges and universities enter a world filled with new change and opportunity. Change is everywhere and we are unable to stop it. We must change, we allow it, we embrace it and let it happen.

Another great reminder of change was evident in the annual Henry Stewart DAM New York conference that took place on April 30 – May 2. For three days, DAM (Digital Asset Management) practitioners, professionals and vendors came together to share their wisdom, engage in vigorous debate and exhibit the latest and greatest that DAM has to provide.

With such a gathering of intellect and passion, there are always key talking points that resonate with the crowd and rise to the top of conversations. DAM issues such as metadata and rights management were there to be heard and argued by the crowd. The issue of “change” and in particular “change management” was there in force, receiving greater buzz than in previous years. Besides those who were seeking to change their old DAM to a new DAM, and others debating the conundrum of whether or not to upgrade, the idea of “change management” resonated for many for a much more holistic and enterprise point of view. Change was (and is) a topic of a much bigger degree and scale.

Change is Everywhere

“The world as we have created it is a process of our thinking. It cannot be changed without changing our thinking.” — Albert Einstein

Technological innovation results in a constantly evolving business environment. Social media is a great example of how technology and communication has created change in our work. Human beings possess an innate desire to interact and socialize. Over the past few decades, new communication technologies — such as email, the Internet and mobile devices — have become widely adopted. These tools allow us to communicate faster, more frequently and to a larger audience than previously possible.

Social media represents the latest evolution of communication technology and employees may have a variety of social media technology tools at their disposal. Executives are watching to determine whether corporate social media technology use is merely a passing fad or a process and business technology that will ultimately improve the bottom-line or extend reach.

In another example of present-day change, the “semantic web” allows data to be shared and reused across application, enterprise and community boundaries. This evolution of the web is changing the existing flow of information within the modern business organization transforming it into a place where, “learning with and from others encourages knowledge transfer and connects people in a way consistent with how we naturally interact.” This evolution of the modern business organization may be seen as a fulfillment of the definition of the semantic web as a conduit in data sharing thus transforming business. DAM is central to this change.

Information and all its data and digital assets has become more available, accessible and in some ways more accountable in business. We live in a big data world with so much data at our discretion and under considerable watch and scrutiny from our content creators, users and stakeholders alike. Our organizations need to change as well and not only be prepared for the change, but respond well and be comfortable with our solutions.

Change Management

“I put a dollar in one of those change machines. Nothing changed.” — George Carlin

Change management is an approach to transitioning or changing people, groups of people, processes and technology to a desired, future state within an organization. The concept and practice of change management was born in the consulting world in the 1980s driven by the need to understand performance and adoption techniques to allow for greater innovation and organizational adoption methods. One of the premier researchers and thought leaders on change management, Dr. John Kotter, reminds us all that

“70 percent of all major change efforts in an organization fail … because organizations often do not take the holistic approach required to see the change through. ”

Change management is a structured approach to ensure changes are made in order to achieve some form of long-term benefits. DAM is all about change: changing the way we understand what is an asset, digital and physical, in our organizations and how its value may be transcended throughout all layers of the organization. With such change, the contemporary business organization is motivated by exterior factors (e.g., competition and innovation) to adapt quicker than their competitors to avoid getting left behind.

John Horodyski @jhorodyski is a Partner within the Media & Entertainment practice at Optimity Advisors, focusing on Digital Asset Management, Metadata and Taxonomy.

May 27, 2014

Surge in Inaugural Exchange Enrollment Sets the Stage for 2015

by Sneha Chiliveru

Despite its much publicized rocky start, enrollment in health plans through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) insurance exchanges surpassed 8 million enrollees in its inaugural open enrollment period, beating initial budget forecasters’ projections by more than one million subscribers.

After accounting for potential nonpayment of premiums, roughly half of the states met or exceeded enrollment expectations after the surge in enrollment during March and early April. Florida, California, Texas, and Idaho led the pack with the highest percentage of enrollments compared to expectations.

Participation in the exchanges increased from 61 percent of projected enrollment, as of March 1, 2014, to 115 percent by April 19, 2014. Marketplaces have enrolled 24 percent of projected 2016 enrollment and 13 percent of their target populations. In addition, both State Based Exchanges (SBMs) and Federally Facilitated Marketplaces (FFMs) have also exceeded Marketplace projections by 121 percent and 113 percent, respectively. However, within these categories, projections vary widely among states, with some states already exceeding projected 2014 enrollment figures, and others enrolling less than 25 percent of their projections.

As the data indicate, enrollment numbers for the exchanges have significantly passed projected targets. If these initial trends are harbingers of the exchanges growth potential, states can expect to see substantial enrollment increases in the coming years.

These data trends are anticipated to be even more favorable once final numbers are released with updated paid member rates. This is an exciting time for the healthcare industry as it looks forward to the 2015 enrollment kickoff. If premium rates hold or increase minimally, as analysts forecast, we can expect even greater gains in enrollment as enthusiastic early adopters spread the word about the value provided them by the new exchanges.

Sneha Chiliveru is an Associate at Optimity Advisors.

May 20, 2014

Why Companies Struggle With Innovation and Collaboration

by Rod Collins

In a recent survey of over 1,700 CEOs, IBM reported the need to innovate and collaborate as uppermost on the minds of business leaders in both the public and the private sectors. Three out of every four CEOs in the study identified collaboration as the most important trait that they are seeking in their employees, and, in the face of an increasingly complex world brought about by the sudden emergence of the technology revolution, many chief executives realize that they need to make significant changes if their organizations are to respond to market pressures to innovate. In short, the business survival strategy for a market landscape where technology now tops the list of external forces impacting organizations is a simple mantra: “Innovate and collaborate.”

However, what is simple is not necessarily easy. While chief executives recognize they need to dramatically improve their capacities for both innovation and collaboration, it appears that few of them know what to do to accelerate their performance in these two critical strategic competencies. This may explain why, in his analysis of a recent study by economists Robert Litan and Ian Hathaway, Richard Florida notes that a reduction in business dynamism has led to the troubling condition where “business deaths now exceed births.” Perhaps the reason developing an effective capacity for innovation and collaboration is so hard is that many, if not most, business leaders are unaware of the defining elements of these two competencies.

When people think of innovation, they usually think of inventions, such as the Apple iPhone, Google glasses, or Wikipedia. While these products are indeed the outcomes of innovation, they are not the essential ingredients that make these companies masters of managing change. Often, when business leaders decide innovation is an important strategic initiative, their first move is to set up a department, put somebody in charge, and hold that person accountable for coming up with ideas for innovative products. Unfortunately, these initiatives rarely produce real results. Innovation is not a department. It is a way of thinking and acting that alters the fundamental DNA of a business and its management so that creativity—which Steve Jobs defined as the simple act of connecting things—becomes the core fabric of the enterprise.

The essential element of innovation is serendipity, which is the capacity to make unusual connections. These connections are the incubators for innovative product ideas. Serendipity is something that is more likely to happen when people from various disciplines exchange ideas than from isolated activity inside a bureaucratic department. People working in silos “doing their part” are far less likely to come up with the idea of combining your telephone and your music collection into one device than a collection of workers from multiple perspectives. That’s why, for example, Google provides free meals for its workers. While many laud the company for its progressive approach to employee perks, the real reason for Google’s free food is to enable opportunities for serendipitous encounters.

When we think of collaboration, what usually comes to mind is a picture of a highly cooperative and coordinated group who really enjoy working together. We tend to think that group collaboration is a primarily a reflection of individual willingness on the part of different people to support each other. With this understanding, many leaders feel the key to improving collaboration is to train individuals to be more cooperative and are surprised when their training investment yields far less than expected. While cooperation and coordination are indeed important elements of collaboration, neither is the essential element. Jane McGonigal, in her insightful book Reality is Broken, defines collaboration as the intersection of three kinds of efforts: cooperation, coordination, and co-creation. Of the three the most important element is co-creation because when workers have the opportunity to co-create what they do, cooperation and coordination are likely to follow. The simple reality is without co-creation, collaboration is not possible.

The reason why, despite their best intentions, so many companies struggle with innovation and collaboration is that their organizations are usually top-down hierarchies, and thus, are not designed to cultivate these two competencies. In fact, they are designed to unwittingly squash both innovation and collaboration. The defining attribute of the top-down hierarchy is the chain of command, which means, in every traditionally organized company, there is an army of supervisors who tend to be heavily invested in the status quo and have the positional authority to kill good ideas and keep bad ideas alive. Serendipity doesn’t stand a chance against this army because new ideas tend to threaten the status quo. And when the fundamental organizational dynamic is “to do what you’re told” inside fragmented silos, hierarchical bureaucracies are not places where co-creation is even remotely possible.

If CEOs are serious about improving their companies’ capacity for innovation and collaboration, they need to transform their organizations from top-down hierarchies to peer-to peer-networks and model themselves after companies, such as Google, Amazon, Whole Foods, Morning Star, and Zappos. The leaders of these companies understand that, if you want your organization to be highly competent at innovation and collaboration, you design your organization for serendipity and co-creation. That’s why they build peer-to peer networks rather than top-down hierarchies.

Rod Collins (@collinsrod) is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, 2014).

May 13, 2014

Spring Cleaning – Your Records Management Checklist

By Gretchen Nadasky

When you make something, cleaning it out of structural debris is one of the most vital things you do. – Christopher Alexander, architect and design theorist

This is the time of year when lifestyle gurus publish their tips and techniques for cleaning the house, putting away last year’s tax return documents and organizing the gear in the garage for summer fun. At Optimity Advisors, we are busy helping clients spruce up the corporate house with Information Management. Here are some questions to see if it’s time for your company to do some spring cleaning.

It’s 2014, do you know where your risk is? – The first few years of this century may someday be thought of as the Era of E-Discovery. Huge lawsuits from competitors and whistle-blowers have been won and lost with the smoking gun of a careless e-mail or leaked e-document. But did you know that the bigger risk might be lurking in off-site storage? Since physical documents are more costly to access, a new strategy of plaintiffs is to demand large swaths of physical documents in digital form. Companies that don’t know the location and contents of boxes in off-site storage waste millions of dollars on law associates to cull boxes and scan (mostly irrelevant) documents. The process is risky, expensive and adds no enterprise value. Has your company developed and maintained a retention and destruction schedule to minimize this risk? Are the officers of your company aware of the nature of the archived documents so they can make educated risk assessments about that information?

Is there a place for everything… and everything in its place? – Pop quiz: In your company, where are the corporate records located? Today, the answer for most companies is “everywhere.” Workers, managers and corporate officers are now expected to create documents wherever they are. In response to that pressure and others they also store them wherever it is convenient. In addition, third party vendors may be holding important corporate information that only they can access. Cloud solutions can help rein in the digital diaspora but only if the documents can be located in the first place. Lastly, if there is no place to store records employees are more likely to keep multiple copies for convenience, increasing overall storage costs. Does your company know where its records are being held? Is there a policy in place to help employees avoid common pitfalls like storing vital records on their hard drive? Do agreements with third party vendors include provisions for the return of your own information?

Plan to go abroad this year? - With the international news cycle full of stories about security breeches of individuals and companies in the United States, European and Asian companies are becoming hesitant to expose their own citizen’s information in the US. Safe Harbor talks are heating up the backchannels of diplomacy and are likely to result in stiffer international rules. Is your company thinking about expanding or hiring abroad? What systems and procedures are in place to protect electronic Personally Identifiable Information (PII) from hacking or misuse? A good spring cleaning program would include an assessment of PII in everyday workflows to ease the flow of international trade.

What would the CEO do? – Launching a corporate-wide spring cleaning initiative will take a directive or guidance from the top. Most employees want to be good information stewards. Clear direction from the top will give employees permission to take time from their day-to-day role to manage their own information. With the amount of content being generated everyday, it takes a little effort from the entire company to make sure that information is properly handled, but the key to success is clear and concise directives. Does your company have an executive mandate for information governance?

Do you fight for your rights – or even know what they are? – At most companies content creation in king. Business moves at lightening speed and often the priority is to get the next campaign on-line or content out for the e-commerce site. In the haste to make something new the rights and permissions for images or talent can get separated. A good digital asset management system can keep the records together with the assets and allow for re-use that saves time and money later. Is there a place in your company to store rights information for the expensive content that is purchased? Do users know where to find internally created content so they don’t have to keep re-inventing the wheel?

Optimity Advisors can help to start with one initiative to get your company moving on the path toward controlling digital and physical information and protect important corporate records. Once people see the success of the project they will have ideas of their own to increase efficiency, lower costs and decrease risk. Happy spring cleaning!

Gretchen Nadasky @GNadasky is a Senior Associate at Optimity Advisors.

May 6, 2014

Innovative Leaders Think Outside-In, Not Inside-Out

by Rod Collins

Traditional business leaders often assume that everything that is needed to be successful out in the marketplace is contained inside their organizations. As a consequence, these managers tend to think inside-out and view the outside world more as a conceptual market than as a collection of human customers.

Inside-out thinking reinforces the notion that bosses are more important than customers. This explains why traditional corporate cultures seem to be more interested in pleasing bosses than delighting customers. In the inside-out organization, the focus of business is on the transaction. As a result, we sometimes find that traditional managers don’t attach any real value to their customers because consumers are viewed merely as market mechanisms for the transaction of products into profits.

Innovative leaders, on the other hand, think outside-in. That’s because they put the customer at the center of everything they do. They understand that, if they want to truly know what’s most important to customers, they will never have everything they need to succeed within their walls. Outside-in organizations understand that managing in a rapidly changing world means that managers cannot rely solely on the knowledge of their inside experts. They assume that market reality is subject to accelerating change and that management’s first job is to continually align its strategies and its products with what’s most important to customers. In the outside-in organization, the focus of business is on the customer experience. Thus, if customer values are at odds with management policy, the first step of managers who think outside-in is usually to reconsider the value of the policy.

LEGO is a company that is thriving today because more than a decade ago, its people learned the value of thinking outside-in when they responded in an unusual way to a security breach. In the late 1990s, four weeks after the release of the first version of LEGO’s Mindstorms kits, a student hacker cracked the software code for the new product and created a better version. Rather than defensively protecting its copyright and beefing up its security, LEGO realized that the hacker meant no harm. In fact, the student was a loyal LEGO enthusiast who was only interested in making the product better. So, LEGO’s managers decided to think differently by choosing to embrace rather than to fight the hacker and reaching out to all LEGO enthusiasts to invite them to co-create the next generation of Mindstorms kits.

Today, LEGO supplements its 120 paid designers with 100,000 loyal enthusiasts. Thinking outside-in has literally brought the company free resources. There’s no better way to understand what’s most important to customers than by inviting them to become voluntary co-creators, especially when they care about your products.

Rod Collins (@collinsrod) is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, 2014).

April 29, 2014

Make DAM Your Single Source of Truth

By John Horodyski

A wise educator once proclaimed that there is “a place for everything and everything in its place.” Not only is this true today, but it’s an absolute necessity where rich media assets compete for attention and use within a multichannel distribution framework. Assets are located, changed into different formats and delivered to television, mobile, print and social media with various degrees of accompanying metadata. To speed the process there needs to be a place — and specifically a central place — where all rich media assets may be managed for specific use and distribution. A Digital Asset Management (DAM) system can be that place: the Place of Everything (PoE).

A variety of clever acronyms have been word-smithed for our collective enjoyment over the last couple of years. In particular, Cisco defines the Internet of Everything (IoE) as, “bringing together people, process, data and things to make networked connections more relevant and valuable.” We were also introduced to the Internet of Things (IoT) — uniquely identifiable objects and their virtual representations in an Internet-like structure.

DAM and its placement within the content industries and solutions can be seen as combining these definitions to be a valued structure within an organization — a “place of everything.” This article argues that in order to exact this PoE, a great deal of consideration needs to be paid to the foundational structures of the DAM to ensure that it is intentional, grounded in good design, always striving to adhere to the business requirements at hand and provides an organized solution for its users.

What is Digital Asset Management (DAM)?

As a refresher, DAM consists of the management of tasks and technological functionality designed to enhance the inventory, control and distribution of digital assets (rich media such as photographs, videos, graphics, logos, marketing collateral). DAM enables the ingestion, annotation, cataloguing, storage, retrieval and distribution of digital assets for use and reuse in marketing and business operations. A digital asset is any form of content or media that has been formatted into a binary source and includes the right to use it.

And by design, DAM is intentional and purposeful. The practice of managing digital assets achieves operational control of your organization’s information and intellectual property and leverages their growth potential. DAM may also enhance other mission-critical systems such as e-commerce and online shopping experiences. DAM must be grounded in strategy and supported by business decisions driving the program. DAM as the PoE serves as the single source of truth for all assets within an organization.

DAM Considerations

It’s commonly known but worth repeating: technology should never lead the decision making process for DAM demands — the business sets the foundation for strategy first. Technology is incredibly important and the vendor review and selection process is a critical step, but that step must follow the business requirements and digital strategy.

Deciding to implement a DAM system is a step in the right direction to gaining operational and intellectual control of your digital assets, and it is a decision to be taken seriously. Any successful DAM implementation requires more than just new technology — DAM requires a foundation for digital strategy. Creating the whole DAM solution and connecting it throughout your business means that assets can generate revenue, increase efficiencies, and meet new and emerging market opportunities.

DAM is more than a sum total of its parts. Digital Asset Management must include a detailed review and analysis of all the contributing factors: digital assets, organization, workflow, security, etc. It takes a considerable effort to get everything in its place, there is no magic here.

Foundation for DAM

Every strategy needs to start with a foundation, a solid base upon which some form of structure rests and where meaning may be established. Intention starts when you build the business case for DAM and the foundations soon follow. A successful DAM strategy uses key foundational structures to ensure that everything can get into its place:

Foundation #1 — Assets

Foundation #2 — Metadata

Foundation #3 — Taxonomy

Foundation #4 — Workflow

Foundation #5 — Digital Rights Management

Foundation #6 — Work in Progress / Digital Preservation

Foundation #7 — Governance

Great content isn’t really great until it gets found, consumed and shared. We can thank metadata for most of that organization, but there needs to be a central initiative to create and support that single source of truth. The opportunity for content owners, marketing technologists and all those managing content lies in understanding the value metadata provides their assets, and how it can empower their digital operations from creation, to discovery, through distribution.

John Horodyski @jhorodyski is a Partner within the Media & Entertainment practice at Optimity Advisors, focusing on Digital Asset Management, Metadata and Taxonomy.

April 22, 2014

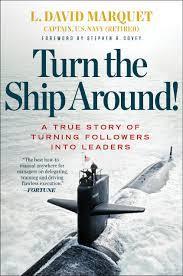

Turning Followers Into Leaders

by Rod Collins

The most unlikely place where you might expect a radical reinvention of management is the U.S. Navy. After all, command-and-control is synonymous with the military. As in most organizations, rank divides people into unequal strata where those with higher rank are the leaders and those at the bottom of the chain-of-command are the followers. The dynamics of top-down structures are very clear: The leaders give the orders and the followers do what they’re told. In traditional organizations, compliance is the ultimate virtue. One former submarine captain, however, doesn’t agree. He believes there’s a better way to run a ship, and he has the experience to back up the belief.

The most unlikely place where you might expect a radical reinvention of management is the U.S. Navy. After all, command-and-control is synonymous with the military. As in most organizations, rank divides people into unequal strata where those with higher rank are the leaders and those at the bottom of the chain-of-command are the followers. The dynamics of top-down structures are very clear: The leaders give the orders and the followers do what they’re told. In traditional organizations, compliance is the ultimate virtue. One former submarine captain, however, doesn’t agree. He believes there’s a better way to run a ship, and he has the experience to back up the belief.

In his book, Turn the Ship Around!, L. David Marquet tells an engaging story of how he used a radically different management model to transform his crew’s submarine from worst to first. When he took command of the Santa Fe in early 1999, the ship had the unenviable reputation of being the joke of the Navy. No one wanted to be on this ship because it could kill careers, which may explain why the Santa Fe had the worst retention rate and one of the lowest promotion rates in the submarine force.

One advantage to being asked to turnaround a deteriorating situation is that the leader often has a lot of latitude as long as the job gets done. Marquet took advantage of this latitude and used it as an opportunity to consider a radically different way to lead a submarine. He would disregard the ultimate virtue of compliance—the fuel of what he calls the “leader-follower” model—and instead embrace the value of collaboration as the organizing principle for his new assignment. He would turn the ship around by displacing the “leader-follower” model and employing a “leader-leader” model. In other words, on his new ship, everyone would learn how to lead together.

Implementing leader-to-leader meant changing the fundamental dynamics of the ship’s operating system. It meant people needed to take the initiative rather than wait for instructions, focus on what needed to be done over blindly following procedures, communicate frequently when dealing with the unexpected, and—a truly radical idea—questioning the ranking member when he or she was wrong. In short, the crew would need to behave very differently if they were going to leverage the power of collaboration.

In considering the strategy for how he would implement the leader-to-leader model, Marquet knew he had to change both the thinking and the acting of the ship’s crew. His challenge was deciding which to change first. Often, when implementing culture changes, leaders mandate everyone to participate in training programs where people are instructed in new ways of thinking. This theory assumes people are highly rational and that new ways of thinking will inevitably lead to new ways of acting. Unfortunately, people aren’t always rational and often resist mandatory training by being present in body only and leaving the programs with their old thinking firmly intact. Recognizing this, Marquet decided on a different approach. Instead of trying to change the crew’s thinking as a pathway to new action, he would change the operating system and require people to act differently, hoping that the new thinking would follow. Whether or not changed thinking actually resulted was less of a concern to the captain. Marquet understood that, when it comes to culture change, what matters most is that people act differently.

In changing the ship’s operating system, he introduced innovative practices and mechanisms that were designed to improve the ship’s overall state of control by delegating control and decision-making authority to those actually doing the work. One such practice was a discipline Marquet calls “deliberate action,” where the crew would state what they intended to do before they would do it. So, for example, an officer on the bridge might announce, “Captain, I intend to submerge the ship,” to which the captain would usually respond, “Very Well.” However, if a member of the crew noticed something was amiss, he was encouraged to share his observation so the crew could process the information as a team before the action was taken.

To illustrate the power of deliberate action, Marquet relates the story of how, while participating in a drill, he unknowingly became confused about the ship’s direction and instructed the ship to make what would have been an incorrect maneuver. The benefits of the leader-to-leader operating system became apparent when, the ship’s quartermaster simply stated, “No, Captain, you’re wrong.” The captain quickly recognized his error and averted a serious mistake because of the new ways of acting that he put in place. On how many ships is it safe to tell the captain he’s wrong? When collaboration rather than compliance is the guiding principle, the captain’s confusion never becomes a ship error.

Marquet’s experiment in shared leadership was immensely successful because, as the Navy inspectors pointed out after assigning the Santa Fe the highest grade that anyone had seen, “Your guys tried to make the same number of mistakes as everyone else. But the mistakes never happened because of deliberate action. Either they were corrected by the operator himself or by a teammate.” As Marquet astutely observes, “Many people talk about teamwork but don’t develop mechanisms to actually implement it.” Deliberate action is a mechanism that transforms teamwork from wishful thinking to reliable action. It’s a valuable lesson for any organization that takes teamwork seriously.

Rod Collins (@collinsrod) is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, 2014).

April 8, 2014

Revolutionizing the Way Power Works in Organizations

by Rod Collins

Whether an organization is effective or not is all about power. Effective organizations are powerful players with the wherewithal to shape the world when they can and to quickly adapt when they can’t. Ineffective organizations are those that are powerless in the face of difficult or challenging circumstances. If you want to be the leader of an effective organization, you need to be highly skillful in the use of power.

Unfortunately, power generally has a bad reputation. While social scientists define power, achievement, and affiliation as the three fundamental orientations in human social relationships, most of us are much more comfortable with calling ourselves achievement-oriented or affiliation-oriented than we are with owning up to being power-oriented. If someone strives to be successful at an art or a craft, we think of her as wanting to be accomplished. If a person is good at making friends, we call him popular. But if people are driven by a need to be continually in charge of things, we often describe them as power hungry. Most of us tend to think of power in a negative light. That’s because most of our experiences with power are inside hierarchical organizations where power is equated with control.

The notion of power is actually neutral; it is neither good nor bad. Whether we experience power as positive or negative often reflects the quality of our relationships. That’s because power is always interpersonal and only exists within the context of relationships. In hierarchical organizations, power is generally ascribed by position, with those few in higher positions having more authority than the many in the lower ranks. Thus, most of us perceive the exercise of authority as about being in charge and having power over people.

The technology revolution, however, is radically reshaping the way power works, especially in large organizations. The late psychologist Abraham Maslow observed that the most effective leaders invest in power with rather than power over people. Our early experiences with online collaborations are demonstrating that Maslow’s observation holds true for organizations as well. Wikipedia, Craigslist, Linux, eBay, and Google are not interested in exerting control or having power over people. These 21st century businesses understand that, in today’s fast-paced world, the best companies are those who build platforms to share power with people. By building networked structures to aggregate and leverage the collective intelligence of the many, these mass collaboration enterprises are able to redefine whole industries and easily outperform their traditional counterparts.

The leaders of these innovative enterprises understand that power with people is much more effective than power over people, especially when organizations have to manage at speed of change to remain competitive in a hyper-connected world. They also understand that, in a post-digital world, the basis for power for effective leadership is rapidly shifting from “being in charge” to “being connected.” Executive power no longer comes from dominating the thinking or directing the work of others; it now comes from integrating the best of everyone’s ideas and leveraging platforms of mass collaboration. In contrast to traditional hierarchies, which limit the interpersonal influence of the many through the ascription of authority, the power structures of digital age companies amplify the opportunities for the development of relationships across all the people within an organizational network. The more connections there are, the quicker a business can access and leverage its collective intelligence.

In our hyper-connected world, power does not come from amassing control, but rather from co-creating a shared understanding. When co-creation rather than control is the fundamental way things get done, being in charge is meaningless because an effective shared understanding can never be mandated. Shared understanding is something that has to be facilitated and created by consensus.

The most significant leadership challenge for today’s corps of business leaders is making the shift in the way they approach power. If they continue to insist that power is a function of being in charge, they are likely to fall victims to the consequences of a world that is changing much faster than their organizations. If they can accept that power in a hyper-connected world is a function of being connected, both they and their organizations will become highly skilled in the exercise of power in a rapidly changing world. That’s because when you have the capacity to leverage your organization’s collective intelligence, nobody is smarter or faster than everybody.

Rod Collins (@collinsrod) is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, 2014).

Rod Collins's Blog

- Rod Collins's profile

- 2 followers