Rod Collins's Blog, page 21

July 29, 2013

Private Exchanges: A Good Time to Try the Waters?

By Robert F. Moss

As we sit just a few months out from the launching of the first public health insurance exchanges (if all goes well, of course), the interest among employers and insurers in private exchanges has continued unabated. Plenty of vendors have stepped up to offer software and services to help insurers and brokers set up their own private exchanges, but as of yet it is a very immature, fragmented market.

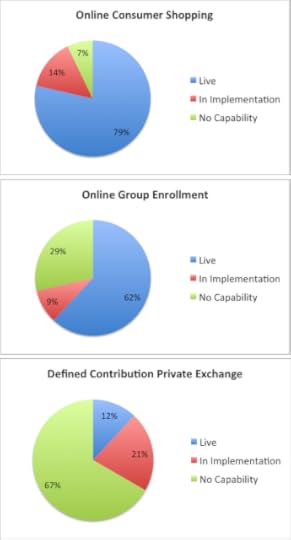

We recently conducted a market scan of 44 of the leading American health insurers (including the national carriers and the larger regional players, namely the Blue Cross & Blue Shield organizations) to get a sense of the current state of defined-contribution private exchanges and compare it to other varieties of online insurance tools. The charts below show the percentage of insurers who are either live on or in the process of implementing the following types of platforms:

Online Consumer Shopping: Allows consumers to shop for and purchase individual and family plans online directly from the insurer.

Online Group Enrollment: Allows employers and their brokers who have purchased group coverage from an insurer to manage the enrollment of their employees through an online portal, including managing open enrollment and making mid-year changes for new hires, terminations, and life changes.

Defined Contribution Private Exchange: Allows employers to specify a pre-defined amount to contribute for their employees premiums and then lets the employees shop for and enroll in the insurance plan of their choice through an online portal.

The end results? What our survey reveals is that, despite all the buzz around private exchanges, few insurers have actually gotten very far down the path, especially when you compare it to other online insurance sales and enrollment tools. We are still very much at the “toe-in-the-water” stage, though more and more insurers are starting to take the plunge.

A couple of key takeaways for insurers considering jumping in themselves:

While private exchanges are new, they are no longer bleeding-edge new. A small but growing number of insurers have already taken them live and worked through shaking out the inevitable first-mover kinks.

More and more insurers are starting to get onboard, so to stay competitive insurers need to be actively working on their defined contribution strategy.

It’s not too late. With more than half of the largest health insurers not yet underway with an actual implementation, it’s a prime time to get out ahead of the competition without having to be the initial guinea pig for unproven solutions.

We’ll be keeping an eye on these numbers and update them periodically as more insurers bring their initial offerings to the market.

Robert F. Moss is a Senior Manager at Optimity Advisors

July 22, 2013

The Interdependence of Strategy and Execution in a Rapidly Changing World

By Rod Collins

While the digital revolution and its incredible pace of change are dramatically altering the work we do and the ways we work, the two fundamental accountabilities for business leaders remain constant: strategy and execution. What is changing is how companies approach and carry out these two timeless tasks.

In traditional businesses, planning and executing are usually considered distinct functions requiring different core competencies. Planners are seen as the “big sky, out-of-the-box” thinkers who move the business forward while the operators are valued as the “down-to-earth” pragmatists who get things done. Unfortunately, one of the consequences of this longstanding functional segregation is that middle managers and workers often have little understanding about the connections between these two essential dimensions of the business. While this is troublesome in normal circumstances, it can become deadly in times of great change.

In its surveys of some five million people over the last 25 years, FranklinCovey has uncovered alarming evidence of persistent managerial deficiencies in the performance of both strategy and execution. While workers give managers high marks for their work ethic, they rate their leaders poorly for their capacity to provide clear focus and direction. Thus, the late Stephen Covey concluded, “people are neither clear about, nor accountable to, key priorities, and whole organizations fail to execute.”

Until recently, most organizations have been able to keep their heads above water, despite these deficiencies, because the relative stability and the slower pace of change before the advent of the Internet allowed enough time for their bureaucracies to make the necessary corrections and still keep pace with the market. Companies had time to learn from mistakes, to do rework, and still meet their market goals.

However, the sudden emergence of accelerating change over the past decade is challenging the wisdom of the functional segregation of management’s two core accountabilities. The most important thing to understand about the relationship of strategy and execution in fast changing times is that they are not separate activities; they are interrelated and interdependent responsibilities. Thus, any company today that organizes strategy and execution into different and distinct departments is making a serious error. In fast-paced markets, organizing effectively means a company’s organizational structure must foster and facilitate continual iteration between strategy and execution. Unlike in the Industrial Age, these accountabilities are not sequential events where strategy precedes execution. In the Digital Age, strategy shapes execution and execution, in turn, shapes strategy.

Strategy in a hyper-connected world begins and ends with customer value, which means the mission of a business has more to do with delighting customers than creating shareholder wealth. This is the secret behind Apple’s remarkable success and the impetus that distinguishes Apple from its many competitors. While shareholder wealth continues to be important, it is no longer paramount as was true during the twentieth century. In a post-digital world, pleasing the customer is the prime concern for the simple reason that you can’t have shareholder wealth if you don’t have any customers. And perhaps no company understands this wisdom better than Apple.

When the core mission is creating customer value, strategy is the identification of the core business infrastructure necessary to continually fulfill a company’s promise to its customers, and execution is the design and management of business processes to meet or exceed customer expectations. Because we are now living and working in a time of great change, customer expectations evolve at a far more rapid pace than was true in the relatively slower Industrial Age. This means that strategic infrastructure needs to be continually updated to keep up with ever-changing consumer expectations. The recording industry failed to understand this when they persisted in pushing CD’s despite the customers’ preference for digital downloading. Apple, on the other hand, recognized and embraced changing customer expectations to become a major player in the music industry.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, strategy was product-centric and execution was transactional. The goal of strategy was to devise great business models and then to exploit the related products for decades, if possible. The job of execution was to efficiently transact the sale, delivery, and servicing of the goods and services. In a product-centric transactional world, business isn’t about customers; it’s about profits. From this vantage point, customers are often viewed as the intermediate variable between products and shareholder profits.

All that has changed in the wake of the digital revolution. In twenty-first century business, strategy is customer-centric and execution is all about creating a superior customer experience. In today’s business world, shareholder profits are the reward that companies receive when their products delight customers. Maintaining a product edge has become increasingly difficult because the life of business models has shrunk from decades to years. The best strategies today are adaptive not exploitive strategies.

Because those who execute are closest to the customers, their real-time knowledge is critical to informing strategy formation in a rapidly changing world. When the mission of business shifts from maximizing shareholder wealth to delighting customers, you can’t afford to leave those who know the customers best out of the room when charting the course of the company. That’s why strategy and execution are now permanently intertwined.

Rod Collins is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of the upcoming book, Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, November 1, 2013)

July 15, 2013

Creating The Future in a Time of Great Change

By Rod Collins

In times of great change, managers can get themselves into serious trouble if they rely too heavily on past experience. Their extensive industry knowledge and thorough understanding of proven business models may actually become deadly liabilities if markets are suddenly and rapidly transformed by game-changing technologies. Unsuspecting market leaders can be quickly overtaken and even extinguished if they fail to understand that, in fast-changing times, past expertise is no guarantee of future performance. Border’s, Blockbuster, and the Encyclopedia Britannica are notable examples of market leaders who were summarily displaced by innovative upstarts that didn’t know much about the past but had a clear sense of the future.

The fundamental job of management is to create the future, and until very recently, managers have long used a reliable assumption to successfully deliver their key responsibility: The past is a proxy for the future. For more than a century, this prime assumption served as the core belief for navigating the business landscape. That’s why business leaders worship at the alter of data and analysis. The more they know about the past, the better they can forecast the future.

But what happens when the past is no longer a proxy for the future? What happens when the arc of change suddenly shifts from incremental to disruptive? These are questions that Gary Hamel ponders in his most recent book, What Matters Now: How to Win in a World of Relentless Change, Ferocious Competition, and Unstoppable Innovation. And if Hamel’s answers to these questions are correct, the survival of many corporations and their managers may very well depend upon their letting go of familiar assumptions and embracing the unprecedented realities that now define business in the twenty-first century. If they want a different future from Border’s, Blockbuster, and the Encyclopedia Britannica, they need to accept the increasing evidence that a nineteenth century management model is unsustainable in a twenty-first century world.

With the rapid convergence of accelerating change, escalating complexity, and ubiquitous connectivity spawned by the transformational power of the Internet, we have been suddenly thrust into a world where the past is indeed no longer a proxy for the future. And while the future may be very different, it is not necessarily unmanageable; it just needs to be managed differently. That’s because the future no longer begins with a managerial elite charged with orchestrating our institutions; rather, the future today is more likely to start on the fringes in a hyper-connected world far from the control of those who think that they are still in charge. Hamel points out that, while the future may no longer be an extrapolation from the past, it is nevertheless hidden in plain sight. Quoting the author William Gibson, Hamel reminds us “The future has already happened, it’s just not evenly distributed.”

According to Hamel, companies miss the future not because it’s unpredictable or unknowable, but because it’s unpalatable and disconcerting. They miss the future because both they and their leaders need to quickly learn that “organizations lose relevance when the rate of internal change lags the pace of external change.” This means the most important question for any organization is: “Are we changing as fast as the world around us?” If companies are to thrive in a world where the past is no longer a proxy for the future, they are going to need to change the way they change.

The sudden emergence of accelerating change means that everything now changes exponentially. Unfortunately, business leaders don’t have much experience with exponential change. They are much more seasoned in the ways of discipline and efficiency shaped by a management ideology where control is the principle preoccupation of most management systems. However, in times of accelerating change, it isn’t the most controlled or the most efficient organizations that survive, but those that are the most adaptable and resilient.

Traditional organizations are not designed to be adaptable or to manage at the pace of exponential change; they’re designed for maintaining the status quo and for steering incremental change. And when they do make large-scale changes, it’s often in the face of a traumatic crisis. As Hamel observes, “Review the history of the average corporation and you’ll discover long periods of incremental change punctuated by occasional bouts of frantic, crisis-driven change.” When exponential change supplants incremental change as the norm, the capacity to change without trauma becomes essential for the simple reason that the severe stress of never ending crises is unsustainable for most human organizations. That’s why Hamel advocates, “Building organizations that are as resilient as they are efficient may be the most fundamental business challenge of our time.”

The greatest impediments to building resilient organizations are the control systems that have served as the standard of management excellence. Resilience requires innovation, creativity, exploration and experimentation. To be resilient, managers must have a capacity for iterative learning, which means that they must have a willingness to take risks, to sometimes fail, and to learn from what are hopefully small failures. While embracing explorative failure may be a hard adjustment for control-oriented managers, they may not have a choice because avoidance of small failures in times of great change may turn out to be the fastest pathway to ultimate failure in a world where only the innovative survive.

If companies are to cultivate the innovation that they need to be resilient and adaptive, Hamel argues that they need to make sure that the senior leaders don’t dominate the strategy discussion. Instead, the conversation about company strategy needs to be shaped by individuals who are emotionally invested in the future rather than experienced in the past. This means expanding the diversity of those who shape strategy. Hamel suggests, “One simple way of increasing diversity is to overweight every team and decision-making body with individuals who are younger than the company average, have worked in other industries, and aren’t based in the head office.”

Creating the future in a twenty-first century world reshaped by change, connectivity, and complexity requires a paradigm shift in the ways we manage organizations. Managing great change is only possible if we change how we manage. Those business leaders who have the courage to embrace new assumptions and new ways of thinking by building organizations that are designed to adapt rather than to control will be better poised to create the future in a time of great change.

Rod Collins is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of the upcoming book, Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, November 1, 2013)

July 8, 2013

Google’s Secret: High Information/High Energy

by Rod Collins

Two of the most important scientific discoveries of the twentieth century are the identification of the double-helix molecular structure of DNA by James Watson and Francis Crick and the formulation of Albert Einstein’s famous formula e = mc2. Together these two revelations have greatly expanded our understanding of the world around us because they have uncovered the two key fundamental dynamics that explain how life develops and evolves: information and energy. The evolution of organic life is the continual interplay between the ability to process information and the energy to transform information into growth.

As business leaders struggle to survive in a hyper-connected world redefined by the technologies of the digital revolution, these two twentieth century discoveries may provide insight into how managers can master the new and unprecedented challenges of business in a post-digital world.

When you think about it, information and energy are also the two key fundamental dynamics that make organizations work. That’s because successful business organizations—especially in the early days of the digital revolution—are essentially information processing systems that have the necessary energy to realize timely growth in rapidly changing markets, Perhaps no business understands this better than Google, which may explain why the Internet giant keeps rising on the list of the Fortune 100 and currently tops Fortune’s list of the 100 “Best Companies to Work For.” Google is thriving in our fast-changing world because they are able to sustain both a high-information and a high-energy company.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, Google understands that being a high-information company entails more than having the best analytical software. While the engineers at Google certainly value the usual quantitative analytics, the high tech company also understands that there is a wealth of information beyond the numbers that can only be accessed through what can be best described as creative information processes. They also understand that if they are going to keep up with a rapidly changing world, they need to have everyone fully engaged in growing the company. You can’t have a high-energy company unless all your people feel fully engaged in the creation of your products and services. That’s why Google’s workplace looks more like a college campus than a traditional office.

Google’s facilities are designed to enable continual connections that promote both high information and high energy. People don’t work in offices or cubes myopically focused on narrow tasks. Instead, they sit in open spaces with their project teams so they can continually bounce ideas off each other. They share free meals with other Googlers where chance conversations among people who normally don’t work together can spark the unusual connections that are often the genesis of the innovative idea. They are encouraged to challenge the status quo and to follow their passions, which is why they get to self-direct 20 percent of their time on projects of their own choosing. And they are free to engage in conversations with whomever they please and never need to get one person’s permission to speak with another individual, as is the common practice in more traditional organizations. Google is a high-information and high-energy workplace because its leaders have designed their organization to be a collaborative network rather than a bureaucratic hierarchy.

Google’s innovative management approach is a sharp departure from the conventional practices of the typical business organization. Walk into any traditional workplace and it is highly unlikely that you will see anything resembling a high-information/high-energy environment. Instead, you will find rows of cubicles where workers are isolated from each other, key information is closely held and shared on a “need to know basis,” and people are reluctant to challenge the status quo or bring forward innovative ideas for fear of being “shot down.” In low-information/low-energy environments, safety rather than passion is the prime concern. No wonder, according to a recent Gallup survey, only 30 percent of workers are passionate about their jobs.

If businesses are serious about succeeding in a rapidly changing world, they need to embrace Google’s secret and design their organizations so that information flows freely, innovative ideas are welcome, and people are highly connected. Only in high-information and high-energy workplaces can passion prevail. And that’s most important because, in fast-changing times, passion is the only sustainable competitive advantage.

Rod Collins is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of the upcoming book, Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, November 1, 2013)

July 1, 2013

The Real Thing: What’s Most Important to Customers

By Rod Collins

Increasingly, business leaders are discovering the painful reality that what they think isn’t as important as it once was. In a hyper-connected, fast-changing world where customers have instant access to each other, what matters most is what’s most important to customers. Business leaders who assume that their years of experience provide them with special insight into the mind of the customer run the risk of falling victim to executive hubris. An important fact of our rapidly changing world is that the most important information business leaders need to know is probably not in the C-Suite. If executives find this hard to believe, they would do well to heed the timeless lessons learned by an American institution some thirty years ago.

In the early 1980′s, Coca Cola’s flagship product was in danger of losing its century old position as America’s most popular soft drink. Coke’s chief rival, Pepsi, had been steadily gaining market share on the strength of a very effective advertising campaign touting blind taste-tests that showed that even Coca Cola drinkers preferred the taste of Pepsi. Unfortunately for Coke, their own independent taste-tests validated their rival’s claim. With a sense of urgency, Coca Cola embarked on a comprehensive market research project using surveys and focus groups in combination with taste-tests to interview almost 200,000 consumers. However, the data yielded inconsistent results. While the remixed formula was handily beating Pepsi in blind taste-tests, the focus groups hinted that there could be widespread dissatisfaction with the reformulation of the world’s oldest soft drink. Putting their faith in the positive response to the taste-tests, on April 23, 1985, Coke’s executives unveiled the reformulated version of their flagship product, New Coke.

New Coke turned out to be one of corporate America’s biggest business debacles. The negative reaction among Coke’s customers was so widespread, that just 78 days after the lavish launch of New Coke, the original mix was brought back and reintroduced as Coca Cola Classic. While taste is important, many customers valued Coca Cola as a source of social connection and a personal reflection of their identities. Coca Cola wasn’t just a soft drink – it was a meaningful American icon that was an important part of people’s lives.

In the beginning, Coke’s executives ignored the mounting protests of their customers. Coke’s top brass had the data and they thought knew better. They were convinced that their taste-tests were correct and were confident the backlash would die down once the customers came to appreciate the improved taste. However, customer dissatisfaction continued to build to the point where the bottlers—who were much closer to the customers—prevailed upon Coca Cola’s senior executives and forced them to comes to terms with the reality that, for Coca Cola lovers, old Coke was the real thing. Sometimes what matters most isn’t found in corporate reports; it’s found in the minds and the hearts of customers.

If Coca Cola executives had paid more attention to their own bottlers and had involved them in correcting their diminishing sales, perhaps the New Coke fiasco could have been avoided. In all likelihood, the bottlers would have put the executives in touch with the customers’ true values and would have identified far more effective alternatives for addressing Coke’s declining market share. Fortunately for Coca Cola, both the customers and the bottlers found a way to make their voices heard before it was too late, and the executives were humbled by a valuable lesson: The market doesn’t care what the bosses think; like old Coke, what’s most important to customers is the real thing. Now that we live in a hyper-connected world, this wisdom has never been more fitting.

Rod Collins is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of the upcoming book, Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, November 1, 2013)

June 17, 2013

Innovation Is Intentional Evolution

By Rod Collins

There’s a familiar proverb in business circles: “What got you here today won’t get you there tomorrow.” When change happens, the best leaders understand the importance of recognizing dramatic market shifts and being able to implement innovative strategies to respond to new opportunities. With the sudden emergence of the accelerating rate of change spawned by the digital revolution, business leaders are becoming keenly aware that the survival of their companies may very well hinge on their ability to get innovation right.

Seth Kahan’s latest book, Getting Innovation Right: How Leaders Leverage Inflection Points to Drive Success, is a practical guide for business leaders who, while recognizing that innovation is a strategic necessity, are not quite sure what innovation is or how they go about improving their capacity to use innovation to successfully manage at the pace of change.

We live in a time of great change where a never-ending string of new technologies is radically transforming the familiar world of the past few decades. Kahan astutely observes, “As more advances roll out, there will be massive disruptions as industries struggle to build the infrastructure required to accommodate new technology.” One of the consequences of this continual parade of disruptions is that business leaders suddenly find themselves in a new world with a completely different set of rules. If they want to succeed in this new world, they need to learn new ways of thinking and acting. That’s why innovation is so important today.

Kahan defines innovation as “intentional evolution.” Successful leaders in fast-changing times don’t chase reality; they get in step with the pace of change, look for the dramatic shifts in the market—Kahan calls these “inflection points”—and position their companies to gain a powerful competitive advantage through timely adaptation to fast-changing markets. Kahan warns that, if companies fail to develop the ability to detect inflection points, they may suddenly find themselves “out of the game entirely.”

Kahan cautions that a strategy of intentional evolution is not easy because “innovation is bound to run at cross purposes with operational pressures.” Unless business leaders maintain a clear focus and make innovation a true priority, the pressures of the urgent will always trump the development of the important. A powerful positive consequence of intentional evolution is the creation of new ways of operating. Unless there is a balance of the important and the urgent, the old ways of operating never change until it’s too late.

When business leaders make a choice for intentional evolution, Kahan advises them to begin by accepting the uncomfortable reality that their beliefs don’t matter. That’s because their ways of thinking were shaped in a world that is rapidly fading away. If leaders want to recognize inflection points and shift perspective, Kahan urges them to begin by listening to their employees, partners, and customers. That’s because, in fast-changing times, the most important information is more likely on the fringe than in the C-Suite.

Getting innovation right is about aligning the company around the mission of creating value for its customers. Kahan insightfully observes, “The judgment of value takes place in the mind of the buyer, nowhere else.” As business leaders reach out to their employees and suppliers as a way to better understand what’s most important to their customers, Kahan counsels them not to confuse “customer service” with “customer experience.” The focus of customer service is about fixing problems with existing products, whereas understanding the customer experience is about knowing how customers use products to improve their lives. Market shifts and new opportunities are more likely to be gleaned from better ways to improve people’s lives than from fixing existing products. Kahan notes, “So few companies take customer experience seriously that the ones that do have an enormous advantage.”

Rod Collins is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of the upcoming book, Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, November 1, 2013)

June 9, 2013

The Key to Managing Complexity: Creative Management

By Rod Collins

Most businesses today continue to employ a management discipline that was initially formulated in the early twentieth century by the first management guru, Frederick Taylor. Taylor developed the fundamental management model that guided the evolution of the modern corporation throughout the twentieth century. Known as Scientific Management, this model was designed to catapult the efficiency and productivity of workers by applying scientific methods, such as time and motion studies, to discover the best ways for workers to perform the various tasks of production under the close supervision of a hierarchy of managers.

Taylor’s philosophy quickly became the gospel of management and provided the foundation for much of what many of us, over a century later, still consider to be the givens of professional management: top-down hierarchies, the sharp divide between managers and workers, centralized decision-making, and functional organization. When work was about running factories where the average worker had less than an eighth-grade education and business models could be sustained for 30 – 40 years, Scientific Management was a workable proposition.

However, today we suddenly find ourselves in a dramatically different business landscape where the old assumptions of the industrial age are rapidly giving way to new rules that are spawned by the three forces that have given birth to the digital age:

Accelerating change has shrunk the expected life of a business model down to 7 – 8 years. In the world of music, for example, we have witnessed, in a very short time span, the rise and the fall of the CD as consumers drove a preference for the digital download over the compact disc.

Ubiquitous connectivity has created a hyper-connected marketplace where the power to be connected now trumps the power to be in charge, as we recently saw when those in charge at Verizon could not sustain their $2.00 online payment fee over the objections of those who were connected.

Escalating complexity means that we now live in an exponential world where the most effective organizations are based on the operating principles of complex adaptive systems, which explains why Wikipedia is now the most popular reference work on the planet.

In a recent survey of over 1500 chief executives, IBM found that the top management concern among the CEO’s is the sudden appearance of escalating complexity, More importantly, the survey found that over half of the CEO’s indicated they had serious doubts about the ability of their organizations to handle the challenges of a more complex world. Thus, it’s no surprise that, when asked to identify the most important attribute for leadership success, it was creativity, and not problem-solving or analytical ability, that topped the list.

The late Steve Jobs defined creativity as the ability to connect things. Jobs understood that creativity in organizations is only possible if management structures encourage serendipity and emergence. These unplanned occurrences are what happen when people in companies are highly connected. They are also the building blocks of innovation. That’s why, at Apple, there are no business units. Jobs never wanted different areas of his company competing against each other or placing the parochial needs of the unit ahead of the best interests of the company. He designed his organization so that the engineers and the designers had to continually deal with each other to get things done. By keeping these disparate groups connected, serendipity and emergence enabled Apple to become one of the most, if not the most, creative company on the planet.

If creativity is indeed the most important leadership attribute, then organizations must be designed, not as hierarchies with fragmented silos and chains of command, but rather as hyper-connected agile enterprises that are able to innovate at market speed. Despite its longstanding track record of success, the principles and the practices of Scientific Management are no longer adequate to meet the challenges of a post-digital world. Instead, managers need to follow Apple’s lead and learn the innovative ways of thinking and acting of a radically different management model that can be best described as Creative Management.

Rod Collins's Blog

- Rod Collins's profile

- 2 followers