Rod Collins's Blog, page 20

September 23, 2013

The Unsung Leaders of Self-Organization

by Rod Collins

Despite the unprecedented challenges of trying to keep pace with a the world that is changing much faster than their organizations, most business leaders are not yet feeling the full consequences of accelerating change. That’s because many of today’s knowledge and service workers are rescuing their organizations by finding ways to finesse their bosses and self-organize their work out of the sight of those who are supposedly in charge. The simple fact is that a significant amount of the most important work in many organizations today is self-organized. But because the business leaders are not part of the collaboration process, companies are not benefiting from the full potential of self-organization as a business practice to successfully navigate the white water of accelerating change.

Self-organization is only possible when there is a shared understanding. In those instances where workers clandestinely self-organize out of the bosses’ sight, they take the time to develop a consensus among themselves to get the job done in a politically acceptable way. However, because they are working “under the radar,” their innovative shared understanding is usually limited to the small group that created the consensus. These unsung leaders are often forced to go around the bosses, quietly access their own collective knowledge, and keep their shared understanding among themselves to avoid possible adverse political consequences. While this clandestine self-organizing may be saving some companies from themselves in these early years of the digital age, the limited collective knowledge and shared understanding crafted by small enclaves of workers “under the radar” will only work for so long. It’s just a matter of time before the digital revolution and mass collaboration will redefine business in the twenty-first century, just as the industrial revolution and mass production shaped the enterprise of the twentieth century.

Now that worker knowledge is the new means for creating economic value, the success of corporations in a hyper-connected, post-diigtal world is directly related to the quality of their knowledge management. This changes the fundamental challenge of organizing large numbers of people. Because the critical knowledge asset is owned by the workers, the fundamental relationship between companies and workers needs to evolve. As the digital revolution continues to reshape the world of business, it won’t be long before most companies will suddenly discover that they have to abandon the politics of control and embrace the politics of partnership if they want to remain connected to their most important economic asset. They will also quickly learn that bosses are not all that important when workers have both the technology and the capacity to self organize their work. As further developments in technology create more options for knowledge workers to employ their knowledge, companies will need to accept the new business reality that, in a post-digital world, workers are partners and not subordinates. When that happens, workers will no longer need to finesse the bosses to get things done.

Rod Collins is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of the upcoming book, Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, November 1, 2013)

September 16, 2013

Getting the Right Things Done When There’s Too Much to Do

by Rod Collins

The work of management can be summed up in three words: strategy and execution. Strategy is doing the right things and execution is doing things right. Although this work may sound relatively straightforward and simple, many, if not most, companies are challenged in fulfilling these two basic accountabilities. That’s because the “right things” are not always intuitively obvious and doing things right often involves the coordination of many people distributed throughout an organization. Given today’s accelerating pace of change, management’s job has become even more difficult, which may explain why the replacement rate for the Fortune 1000 has risen from 35 percent to 70 percent since the mid 1980’s.

The 4 Disciplines of Execution: Achieving Your Wildly Important Goals by Chris McChesney, Sean Covey, and Jim Huling is a timely contribution for business leaders who want to jumpstart their capacity to manage at the pace of change. The authors observe that the main obstacles to accomplishing key strategic goals are having too many goals and the press of day-to-day activities. The practice of maintaining an endless stream of initiatives as a response to changing markets may look good on paper but rarely works in reality because there are limits to the human capacity to do things with excellence. Furthermore, new initiatives always have to compete with what the authors call the “whirlwind,” which they define as “the massive amount of energy that’s necessary to keep your operation going on a day-to-day basis.” They also correctly point out that, without an effective discipline, the whirlwind will grab everyone’s time and attention, making it impossible to execute on anything new.

The four disciplines are a powerful framework for managing the twin accountabilities of strategy and execution. The first discipline is to Focus on the Wildly Important. The wisdom behind this discipline is accepting the counterintuitive notion that the way to do more is to focus on less. There is ample data and anecdotal evidence that the more business leaders try to do, the less they actually accomplish. It’s better to focus on only one or two really important goals and do them well because there’s no chance of accomplishing anything if business teams try to do a dozen goals at once. Focus is the only antidote to the whirlwind.

The second discipline, Act on Lead Measures, recognizes that all actions are not of equal value. Some actions are more valuable than others in driving execution. Discovering and tracking these key drivers is an important enabler of getting things done. The authors distinguish between two types of measures: lag and lead indicators. While most managers are riveted on lag indicators, such as profitability and market share, these measures are poor management tools because they are not actionable. Lag measures are like scores in a sporting event: They let you know whether you’ve won or lost the game, but they don’t help do anything about a game that’s already over. Management’s most important job is to affect performance before the game is over, and the best measures for doing that are leading indicators. According to the authors, a good lead measure has two characteristics, “it’s predictive and it can be influenced by the team members.” Lead measures are the keys to right action at the right time, which is why the authors consider lead measures to be the little-known secret of execution.

The third discipline is Keep a Compelling Scoreboard. The insight behind this discipline is the behavioral reality that people work differently when they are able to keep score for themselves. They shouldn’t have to rely on a supervisor’s opinion that all is going well. If managers want a high level of commitment and engagement from their people, these workers need to be able to judge for themselves whether they are winning or losing. That’s why the most compelling scorecards are the ones that are designed by the workers themselves.

The fourth and final discipline, Create a Cadence of Accountability, creates a rhythm of frequent periodic meetings where people feel accountable to each other. Oftentimes people are more responsive to peer pressure than to pleasing a supervisor. This discipline builds on that dynamic. In these regular, usually weekly, meetings, people report on whether or not they met commitments made at the prior meeting, what changes have occurred since the last gathering, and what commitments each team member will make for the next week. Because team members create their own commitments, there’s an increased likelihood that those commitments will be met.

In fast-changing times, the need to manage both change and the whirlwind has never been more challenging. This simple framework is a powerful tool for getting the right things done when there’s too much to do.

Rod Collins is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of the upcoming book, Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, November 1, 2013)

September 9, 2013

The Secret Sauce of Innovation: Emergence

by Rod Collins

Innovation is the new buzzword of twenty-first century business. As managers struggle to keep up with an ever increasing pace of change and watch established giants, such as the Encyclopedia Britannica, Blockbuster, Tower Records, and Circuit City fall victim to disruptive new business models, they are reluctantly acknowledging the clarion call of modern-day management gurus: Innovate or die!

Unfortunately, most managers don’t have much experience with innovation. They are more skilled in the disciplines of planning and control that are the foundation of a management ideology that has dominated management practice for well over a century. So, it comes as no surprise that when managers decide to get serious about innovation, their first move is often to set up a new department, put somebody in charge, and hold that person accountable for the new function. However, far more often than not, these so-called innovation departments rarely produce real results. That’s because innovation is not a function or a department; it’s a way of thinking and acting that values emergence over control and is radically different from everything managers were taught in business school.

If you don’t understand the power of emergence, you will never understand how to build an innovative organization because emergence is the secret sauce of innovation. Google, the video maker Valve, the tomato processor Morning Star, and W.L. Gore & Associates are examples of companies known for their mastery of innovation. Each of them has designed its business processes to leverage the incredible power of emergence.

In a recent blog post, Margaret Wheatley and Deborah Frieze, describe how emergence works, why it’s so difficult for traditional managers to grasp, and how it is the primary force behind radical change and taking things to scale. Emergence is a systematic process that happens when local actions become connected and form networks that, in turn, create systems with properties that were non-existent before the system was created. In other words, emergence—and thus, innovation—is a creative process. Wheatley and Frieze point out, “the system that emerges always possesses greater power and influence than is possible through planned, incremental change.” Unfortunately incremental change is the only way that most traditional managers know how to change.

Traditional management assumes that the most effective way to organize the work of large number of people is to build hierarchies. In the days before the Internet, there were no competing models for large group organization, and we all assumed that hierarchies were a necessary condition for managing the large enterprise. It wasn’t until the Internet that any of us had a practical experience of an alternative model for organizing large work efforts. Wikipedia and Linux, in particular, defied conventional wisdom by showing us that large self-organized groups can produce effective results leveraging the power of emergence. But perhaps, even more amazing, they can perform their work smarter, faster, and at much less cost. Despite the much-publicized success of these crowdsourced innovators, few companies have followed their lead because emergence isn’t something that can be planned or controlled and blatantly violates many of the assumptions of established management dogma.

Wikipedia and Linux, along with Google, Gore, Valve, and Morning Star, are definitive proof that building networks is a better organizational strategy when management’s primary challenge is keeping pace with accelerating change. If the management gurus are right about “Innovate or die,” then networks leveraging the power of emergence have a distinct competitive advantage over hierarchies. That’s because innovation is an emergent property that naturally flows when the velocity of the dynamic connections reaches a tipping point in a vibrant network. If managers are serious about innovation, they don’t need to set up new departments; they need to transform their organizations into vibrant networks and taste the secret sauce of emergence.

Rod Collins is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of the upcoming book, Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, November 1, 2013)

September 2, 2013

Do Less, Think More

By Carol Huggins

I recently came across a column in the August 17, 2013 issue of The Economist, suggesting that workers would be better off if they did less and thought more. The author observed that today’s business environment has too many distractions and disruptions, and speculated that a major component of what’s keeping us all busy (and distracted) is social media.

Before technological advancements moved from a steady cadence to an all-out gallop, most managers had secretaries to handle their daily minutiae, which gave them a lot of time to think. Nowadays, secretaries — like rotary phones and vinyl records — have become nostalgic relics. One of the consequences of a hyper-connected world is that managers do their own typing and answer their own phones.

The technology revolution has been both a help and a hindrance in balancing our work schedules. In addition to participating in meetings, attending to projects, and strategizing, most modern day workers juggle phone calls, text and instant messages, and emails as a part of their daily (and often nightly) routines. The workday is supposed to be our most professionally creative time, but it’s hard to be creative when we are bombarded by a steady stream of distractions, oftentimes leaving the actual work to be completed during off-hours when we should be focused on our families, hobbies, and other personal pursuits.

While social media has opened up unprecedented possibilities for expanding our access to all kinds of people, it is also a major culprit for why so many of us feel so overwhelmed. According to the Pew Internet & American Life Project, as of May, 2013 almost 72% of online US adults used social networking sites, up from a mere 8% in early 2005. This dramatic increase no doubt reflects the influence of social media gurus who preach that the more you are connected and the more you share, then the more your profile will rise, the more followers you’ll gain, and the more likes you will earn! If they’re not engaged, people fear missing out, not being on the leading edge, not being the first to know. However, for most of us, all this engagement can be overwhelming, leaving no time for what is becoming the lost art of thinking.

Not so long ago, most employers prohibited workers from browsing the web. Now, we encourage employees to retweet and post on behalf of our firms so much so that we have integrated this activity into our marketing plans. And, more and more, bring-your-own-device policies mean people are connected to work 24/7.

In considering solutions to reduce our sense of being overwhelmed and for bringing thought and reflection back to the workplace, I am not advocating that employees stop using social media. In fact, I’m campaigning for both coworkers and friends to adopt and embrace it. After all, social media is one of the defining technologies of our time. However, like any technology, it can be overused. No, what I am suggesting is that we schedule “digital detoxes.” It’s really quite simple and takes just a bit of planning.

As companies continue to embrace the web as a valid resource for connectivity, my hope is that they also will hold onto the values of thinking and reflection. While they exhort workers to leverage the power of social media, they should also encourage them to step away and put down the device regularly in order to focus, single-task, or maybe do a little thinking. This can only lead to a more enriched and balanced corporate culture.

Thinking is still an important business activity. If each of us would devote just one hour a week and unplug during normal working hours, consider how much more thinking we would do—approximately 55 million hours of thinking per week in the U.S. alone.

Carol Huggins is a Manager at Optimity Advisors

August 26, 2013

Why We Don’t Need Bosses Anymore

By Rod Collins

Whether we like it or not, the world where most of us grew up is quickly fading away. We now live in a wiki world where the power of networks and the speed of mass collaboration are redefining every aspect of our social lives, especially the work we do and the ways we work. There is little doubt that the technological innovations of the digital revolution will radically transform every industry. The only question is whether or not existing organizations will have the wherewithal to change as fast as the world around them. And that may be more challenging than business leaders realize, especially if present trends continue.

According to Nathan Furr, the replacement rate of the Fortune 1000 over a decade has recently doubled from 35 percent to 70 percent. If this rate were to remain constant, seven out of every ten companies on today’s Fortune 1,000 won’t be on the list in 2023. This means that it is highly doubtful that the vast majority of existing companies will have the capacity to change as fast as the world around them.

Getting in sync with the pace of change is challenging for so many companies because most organizations are designed as hierarchies, and even though many businesses have trimmed their layers of management, few have done away with their hierarchies. While there may be fewer bosses, the few who remain still call the shots in their organizations. When technology increasingly favors networks over hierarchies, the problem for business leaders isn’t that there are too many bosses, but rather that there are any bosses at all.

When we look around at the companies who are mastering the challenge of managing at the pace of change, there’s a strong likelihood that they won’t have hierarchies. For example, the tomato processor Morning Star, the video game developer Valve, and the makers of Gore-Tex—W.L. Gore & Associates—don’t have any supervisors. Each of these organizations is designed as a network where people are held accountable to their peers. Gore’s self-organized management approach is especially impressive because it has made a profit in every year since its founding in 1958. Over the past five years of financial turmoil, while others were cutting jobs, Gore added over 1000 associates to its payroll.

When technology strongly favors networks over hierarchies, an inevitable consequence is that we don’t need bosses anymore. In fact, the single greatest threat to the survival of most businesses today may very well come from their own bosses. While bosses have been a staple of hierarchical management, they have no place in the workings of a network. That’s because the new level efficiencies made possible by technologies of mass collaboration are only possible when workers have the tools to self-organize their work. In a hyper-connected world, professionals do not need supervisors overseeing the details of their work because today’s average knowledge worker knows the content of her job far better than her boss. In fact, the continual hovering of micromanaging supervisors is more likely to get in the way and slow things down than to add value and move things along. In the wiki world, power comes from being connected, not from being in charge.

The problem with most traditional companies is that those with the power are those who are in charge, and they will do everything they can to preserve their personal power within their organizations. Accordingly, they are reluctant to embrace any change that might diminish their corporate standing, which means they often unwittingly slow the company’s ability to keep pace with the world around them. While the strategy of preserving personal power may work in the short-term, it can be deadly for the company in the long-term if all the bosses make their personal positions a higher priority than their market positions.

In innovative companies, such as Morning Star, Valve, and Gore, those with power are those who are well connected with their teams. Thus, their focus is on making their teams as effective and powerful as possible in meeting the needs of their customers. As customer needs evolve and shift, they are more likely to respond to market movements because their power is directly derived from the ability of their teams to continually delight their customers. In networks, people work for customers rather than bosses, which is why they are able to more effectively change as fast as the world around them

If businesses leaders seriously want to manage at today’s accelerating pace of change, they cannot allow a good idea to be stopped by a single boss, or the value of a suggestion to be weighted by the position of the speaker, nor can they tolerate glacial bureaucracies that fail to keep pace with changing customer expectations or are too slow to recognize that customer values have shifted. The management architecture necessary to leverage the knowledge networks of mass collaboration only works when leaders derive their power from being connected rather than being in charge.

If business leaders want to make sure that their organizations can change as fast as the world around, they need to accept the new reality that you can’t lead twenty-first century businesses using a nineteenth-century management model. The digital revolution is not only changing the world around us; it’s also changing the way we manage that world. That’s why we don’t need bosses anymore.

Rod Collins is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of the upcoming book, Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, November 1, 2013)

August 19, 2013

Shifting Competitive Focus From Industries to Arenas

by Rod Collins

Few of us would dispute that we live in a time of great change. In recent years we have witnessed the sudden shrinking or even disappearance of established enterprises such as Blockbuster, Border’s, the Encyclopedia Britannica, Tower Records, and countless newspapers. Each of these once thriving companies became prisoners of their products while they were suddenly and rapidly disrupted by innovative start-ups leveraging the technologies of the digital revolution. While most business leaders readily acknowledge the wide-ranging impact of the technology revolution, too few grasp that this revolution has thrust us into a new world with a completely different set of rules. Consequently they fail to recognize that business in the digital age works very differently from the established norms that guided companies in the industrial age. This failure may represent the single greatest threat to the survival of many companies.

One of the most fundamental rules of industrial age business was the rule of sustainable competitive advantage. According to this rule, the secret to corporate growth and longevity is finding a way to differentiate your products from those of the competitors in your industry and exploiting that difference to sustain the advantage. In her most recent book, The End of Competitive Advantage: How to Keep Your Strategy Moving as Fast as Your Business, Rita Gunther McGrath explains why this industrial age rule no longer works in a rapidly changing world. McGrath points out that the old rule is based on two foundational assumptions that have become obsolete. The first assumption is that “industry matters most.” This premise is based on the conventional wisdom that a company’s competitors are the other players in its industry. Today, competition can come from anywhere, which is why McGrath proposes a new and broader level of strategic analysis she calls the “arena.”

In contrast to industries, which are prescribed by products made, arenas are defined by customer needs. In the relatively more stable times of industrial age business, company strategy followed the mantra that what we make is what we do. However, the companies who have figured out how to cope with accelerating change—McGrath calls them “outlier companies”—follow a different rule. They focus first on what’s most important to customers and subscribe to the principle that what the customer needs is what we do. McGrath explains, “Arenas are characterized by particular connections between customers and solutions, not by the conventional descriptions of offerings that are near substitutes for one another.”

This shift of focus from industry to arena is critically important because, in a rapidly changing world customer needs continually evolve in response to a steady stream of technological innovations. Thus, any competitive advantage gained is temporary at best. Accordingly, McGrath advises business leaders to become nimble at “transient competitive advantage,” by developing the skills to succeed in volatile and uncertain markets and by redesigning their organizations for speed and innovation.

Designing companies for innovation may be particularly challenging for business leaders seasoned in the ways of traditional management because they will need to radically change their thinking about the relationship of strategy and innovation. In the past, innovation was focused on creating new opportunities and was kept separate from the core operations of the business. Today, the core operations are likely to become the fuel of a company’s demise if they aren’t iteratively renewed or proactively displaced by company-grown innovations. When businesses focus on arenas, strategy and innovation continually reshape each other, products made evolve with the times, and, most importantly, customers don’t suddenly disappear to novel competitors.

Like it or not, we live in a new world with new rules. If business leaders want their companies to be sustainable in a rapidly changing world, they need to understand the most sustainable competitive advantage is not to have a sustainable competitive advantage. Only then will they make sure that their companies never become prisoners of their products.

Rod Collins is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of the upcoming book, Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, November 1, 2013)

August 12, 2013

Most Times Good Management Is “B-o-r-r-ring”!

By Rod Collins

Our picture of business leaders is influenced to some extent by the stereotypes continually reinforced by the mainstream media, who are especially fond of celebrity leaders because they often make for great entertainment. Unfortunately, entertaining leaders are prone to creating a great deal of consternation and confusion – a point that was poignantly brought home during a week-long management training course I attended several years ago.

At one point in the training, the instructor divided the class into two groups to complete the task of ranking a list of items in the order of their importance to the accomplishment of a prescribed mission. Each group was videotaped as they worked the exercise in separate breakout rooms. When we reassembled in the main training room, we weren’t long into the playing of the first recording before we were doubled over with laughter. The numerous attempts by an overbearing leader to take control and the jockeying for dominance by the different members of the group played out like a “Saturday Night Live” skit. Amazingly, despite their continual conflicts, the group somehow managed to complete the task while providing the class with a recorded vignette that was a truly entertaining experience.

When the laughter subsided, the instructor cued up the second recording. The leader of the second group opened the discussion by suggesting a process the team might use to complete the task. After several modifications by the group members, they proceeded to employ their agreed upon method and collaboratively began ranking the items. When the group was about half way through the list, the instructor paused the recording and asked the class, “What do you think?” After a couple of seconds, one person responded, “B-o-r-r-ring!” The instructor then turned to one of the members of this second group and asked her, “How were you feeling when you were working on this task?” She responded, “I was feeling pretty good. People were engaged and listening to each other, and we were getting the job done.” The instructor then asked one of participants of the entertaining first group the same question. He replied, “I know it was funny to watch us, but I was feeling awful while we were working on this. People were competing, not listening to each other, and talking over one another. I didn’t like it.” After a thoughtful pause, the instructor pointed out, “I think that we’re watching an important management lesson here. Good management is not very entertaining to the outside observer, but it feels good for the participants. Likewise, when management isn’t working well, it’s often more entertaining to the outside observer than it is for the participants.

Good management, unfortunately, doesn’t make it to the popular media because it has no entertainment value. The media prefers conflict and competition mixed in with a little dysfunctionality. The Apprentice, for example, would not have been a popular show if, week after week, we watched the participants discover new ways to achieve harmony and collaboration. People tuned in to see who as bickering with whom and to find out who was getting “fired” at the end of the hour. While shows like The Apprentice are indeed entertaining, they aren’t entirely representative of the way businesses, especially well-run businesses, work. Most times good management is “B-o-r-r-ring”!

Rod Collins is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of the upcoming book, Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, November 1, 2013)

August 5, 2013

Innovating the Performance Review

By Rod Collins

Like Thanksgiving and the Fourth of July, the ritual of the annual performance review is a longstanding tradition. But unlike these two holidays, few of us look forward to the annual corporate practice. In theory, performance reviews are supposed to acknowledge good performance and encourage underperformers to improve. However, a mountain of anecdotal evidence suggests that far too often performance reviews engender cynicism and mistrust, create bewilderment and discouragement, and unwittingly diminish the morale of high performing teams. Few would disagree that the performance review is a broken process.

Eric Mosley’s new book, The Crowdsourced Performance Review: How to Use the Power of Social Recognition to Transform Employee Performance provides insight into how twenty-first century managers can reengineer and renew the performance evaluation process. According to Mosley, a big problem with the traditional performance review is that it reflects an outdated paradigm of work that assumes jobs and performance are completely identifiable in advance. While that assumption might have been true for industrial workers on the old assembly lines, it doesn’t fit for the vast majority of knowledge workers who apply their evolving skills in rapidly changing markets.

Another problem with the traditional performance system is, while it purports to provide an objective assessment, its execution is often highly subjective because the review presents one manager’s observations at a single point in time. This is problematic in a time of great change where real-time adaptations of workers to dynamic business circumstances are more likely to be observed by one’s peers than one’s manager. Put simply, much of the work that matters most is performed out of the line of sight of the supervisor. When valuable work goes unrecognized, supervisors unwittingly create low-morale workplaces.

Mosley’s solution for fixing the broken process is the crowdsourced performance review. Based upon the insights contained James Surowiecki’s best-selling book, The Wisdom of Crowds, Mosley outlines a performance approach designed to supplement the traditional performance review with a real-time “social recognition” program that aggregates the opinions of the many peers who actually witness the day-to-day execution of work. Throughout the year employees rate and acknowledge positive performance as they see it happen. When it comes time for the annual review, managers have a rich database that provides “more accurate conclusions than one person could achieve alone.” According to Mosley, the aggregation of many subjective impressions averages out any individual biases, resulting in a more objective assessment from those who are closest to the actual work.

This new model of performance recognition is made possible by three innovations that have emerged from the recent digital revolution. The first is the sudden spread of crowdsourcing applications made popular by the dramatic performance of Wikipedia and Linux. The second innovation is the wide adoption of social media, which makes it easy and practical to gather real-time observations from co-workers. Finally, because we now live in a hyper-connected world, managers are increasingly discovering that a culture of collaboration is often a distinguishing competitive advantage. This third attribute is particularly important because it means, when collaboration is the key ingredient for creating extraordinary results, it is virtually impossible for a single person to accurately assess another’s performance.

In a business world that is continually reshaped by accelerating change, reliance upon an obsolete performance approach is highly problematic. Although it may defy conventional wisdom, peers are often better judges of performance than bosses. This has been the philosophy and the practice for over fifty years at W.L. Gore and Associates, the makers of Gore-Tex. Because there are no supervisors at Gore, they don’t have a traditional review process. The only process Gore has ever used is a peer-based review system. This may explain why Gore is perennially on Fortune’s list of the “Best Companies to Work For.” They understood the value of crowdsourcing long before the term was invented.

For those companies that are ready to update their performance review systems to better meet the challenges of a rapidly changing and more collaborative world, Mosley’s innovative approach is a simple and effective way to get a quick start.

Rod Collins is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of the upcoming book, Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, November 1, 2013)

July 29, 2013

Private Exchanges: A Good Time to Try the Waters?

By Robert F. Moss

As we sit just a few months out from the launching of the first public health insurance exchanges (if all goes well, of course), the interest among employers and insurers in private exchanges has continued unabated. Plenty of vendors have stepped up to offer software and services to help insurers and brokers set up their own private exchanges, but as of yet it is a very immature, fragmented market.

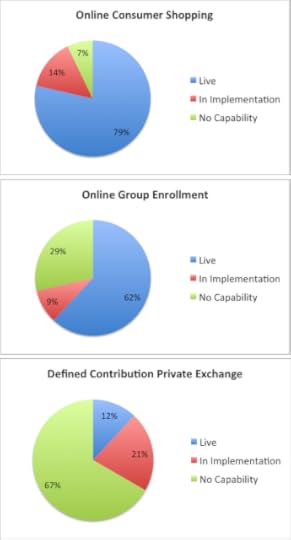

We recently conducted a market scan of 44 of the leading American health insurers (including the national carriers and the larger regional players, namely the Blue Cross & Blue Shield organizations) to get a sense of the current state of defined-contribution private exchanges and compare it to other varieties of online insurance tools. The charts below show the percentage of insurers who are either live on or in the process of implementing the following types of platforms:

Online Consumer Shopping: Allows consumers to shop for and purchase individual and family plans online directly from the insurer.

Online Group Enrollment: Allows employers and their brokers who have purchased group coverage from an insurer to manage the enrollment of their employees through an online portal, including managing open enrollment and making mid-year changes for new hires, terminations, and life changes.

Defined Contribution Private Exchange: Allows employers to specify a pre-defined amount to contribute for their employees premiums and then lets the employees shop for and enroll in the insurance plan of their choice through an online portal.

The end results? What our survey reveals is that, despite all the buzz around private exchanges, few insurers have actually gotten very far down the path, especially when you compare it to other online insurance sales and enrollment tools. We are still very much at the “toe-in-the-water” stage, though more and more insurers are starting to take the plunge.

A couple of key takeaways for insurers considering jumping in themselves:

While private exchanges are new, they are no longer bleeding-edge new. A small but growing number of insurers have already taken them live and worked through shaking out the inevitable first-mover kinks.

More and more insurers are starting to get onboard, so to stay competitive insurers need to be actively working on their defined contribution strategy.

It’s not too late. With more than half of the largest health insurers not yet underway with an actual implementation, it’s a prime time to get out ahead of the competition without having to be the initial guinea pig for unproven solutions.

We’ll be keeping an eye on these numbers and update them periodically as more insurers bring their initial offerings to the market.

Robert F. Moss is a Senior Manager at Optimity Advisors

July 22, 2013

The Interdependence of Strategy and Execution in a Rapidly Changing World

By Rod Collins

While the digital revolution and its incredible pace of change are dramatically altering the work we do and the ways we work, the two fundamental accountabilities for business leaders remain constant: strategy and execution. What is changing is how companies approach and carry out these two timeless tasks.

In traditional businesses, planning and executing are usually considered distinct functions requiring different core competencies. Planners are seen as the “big sky, out-of-the-box” thinkers who move the business forward while the operators are valued as the “down-to-earth” pragmatists who get things done. Unfortunately, one of the consequences of this longstanding functional segregation is that middle managers and workers often have little understanding about the connections between these two essential dimensions of the business. While this is troublesome in normal circumstances, it can become deadly in times of great change.

In its surveys of some five million people over the last 25 years, FranklinCovey has uncovered alarming evidence of persistent managerial deficiencies in the performance of both strategy and execution. While workers give managers high marks for their work ethic, they rate their leaders poorly for their capacity to provide clear focus and direction. Thus, the late Stephen Covey concluded, “people are neither clear about, nor accountable to, key priorities, and whole organizations fail to execute.”

Until recently, most organizations have been able to keep their heads above water, despite these deficiencies, because the relative stability and the slower pace of change before the advent of the Internet allowed enough time for their bureaucracies to make the necessary corrections and still keep pace with the market. Companies had time to learn from mistakes, to do rework, and still meet their market goals.

However, the sudden emergence of accelerating change over the past decade is challenging the wisdom of the functional segregation of management’s two core accountabilities. The most important thing to understand about the relationship of strategy and execution in fast changing times is that they are not separate activities; they are interrelated and interdependent responsibilities. Thus, any company today that organizes strategy and execution into different and distinct departments is making a serious error. In fast-paced markets, organizing effectively means a company’s organizational structure must foster and facilitate continual iteration between strategy and execution. Unlike in the Industrial Age, these accountabilities are not sequential events where strategy precedes execution. In the Digital Age, strategy shapes execution and execution, in turn, shapes strategy.

Strategy in a hyper-connected world begins and ends with customer value, which means the mission of a business has more to do with delighting customers than creating shareholder wealth. This is the secret behind Apple’s remarkable success and the impetus that distinguishes Apple from its many competitors. While shareholder wealth continues to be important, it is no longer paramount as was true during the twentieth century. In a post-digital world, pleasing the customer is the prime concern for the simple reason that you can’t have shareholder wealth if you don’t have any customers. And perhaps no company understands this wisdom better than Apple.

When the core mission is creating customer value, strategy is the identification of the core business infrastructure necessary to continually fulfill a company’s promise to its customers, and execution is the design and management of business processes to meet or exceed customer expectations. Because we are now living and working in a time of great change, customer expectations evolve at a far more rapid pace than was true in the relatively slower Industrial Age. This means that strategic infrastructure needs to be continually updated to keep up with ever-changing consumer expectations. The recording industry failed to understand this when they persisted in pushing CD’s despite the customers’ preference for digital downloading. Apple, on the other hand, recognized and embraced changing customer expectations to become a major player in the music industry.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, strategy was product-centric and execution was transactional. The goal of strategy was to devise great business models and then to exploit the related products for decades, if possible. The job of execution was to efficiently transact the sale, delivery, and servicing of the goods and services. In a product-centric transactional world, business isn’t about customers; it’s about profits. From this vantage point, customers are often viewed as the intermediate variable between products and shareholder profits.

All that has changed in the wake of the digital revolution. In twenty-first century business, strategy is customer-centric and execution is all about creating a superior customer experience. In today’s business world, shareholder profits are the reward that companies receive when their products delight customers. Maintaining a product edge has become increasingly difficult because the life of business models has shrunk from decades to years. The best strategies today are adaptive not exploitive strategies.

Because those who execute are closest to the customers, their real-time knowledge is critical to informing strategy formation in a rapidly changing world. When the mission of business shifts from maximizing shareholder wealth to delighting customers, you can’t afford to leave those who know the customers best out of the room when charting the course of the company. That’s why strategy and execution are now permanently intertwined.

Rod Collins is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of the upcoming book, Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, November 1, 2013)

Rod Collins's Blog

- Rod Collins's profile

- 2 followers