Rod Collins's Blog, page 12

July 7, 2015

Scaling Agile To Create A Great Work Culture

by Rod Collins

If you heard there was this great company to work for where the leaders practiced an innovative management model that promoted fun at work, made sure that everyone’s voice matters, encouraged teams to initiate innovation, and resulted in thousands of applications being received for every job opening, you might think we were talking about Google. You would probably be surprised to learn that we are actually describing one of the oldest legacy companies in America, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska.

Founded in 1939, the midwestern health insurer has a long history of traditional management. However, over the past decade, under the leadership of its current CEO, Steve Martin, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska has quietly become one of the few legacy companies that has successfully transitioned the fundamental dynamics of its management operating system from a top-down hierarchy to a peer-to-peer network. The Blue insurer accomplished this cultural transformation by taking the bold step of scaling the Agile practices of its IT division to the entire organization.

The Best-Kept Management Secret

Agile is an innovative management methodology that was the inspiration of 17 software developers who had gathered at Snowbird, Utah in early 2001 to uncover better ways to do their work and overcome the intrusive and unproductive constraints of traditional management practices. The result of their efforts was the crafting of the one-page Agile Manifesto and the birth of a management movement that, according to the business author Steve Denning, is “the best-kept management secret on the planet.”

Agile management methodologies call for doing work in in self-organized, cross-functional teams. These teams generally work in iterative three-week phases, which are called “sprints,” with clear deliverables at the end of each phase. The interim deliverables are assessed in facilitated collaboration sessions and any needed changes are incorporated into the next sprint. Since it inception in 2001, this management movement has produced extraordinary results in the IT units of hundreds of companies around the globe under the labels Scrum, Agile, and Kanban.

Scaling Agile Beyond IT

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska’s IT area embraced Agile as its basic software development discipline in 2008 when Susan Courtney, the insurer’s CIO, brought it into the organization. The dramatic improvement in the ability to deliver complex IT projects consistently on time and significantly under budget caught the attention of Martin, who wondered what might happen if this new Agile methodology was scaled into the regular business units. Inspired by the opportunity to make a leap to extraordinary performance, the health insurer’s leadership team began an effort to train their managers and staff in Agile tools and practices.

One of the first things the staff learned is that the essential building block of work is not the individual, but the team. This doesn’t alleviate individual responsibility, but rather shifts the focus of responsibility from the performance of individual tasks to the performance of team contributions. Cameron Ludwig, the Vice President of Analytics and Data Strategy, explains this shift is important because, “Delivering customer value only happens when the whole team performs.” Accordingly, people are accountable to all members on their teams, and everyone is expected to keep their commitments and to help other team members when needed.

From Pyramids to Triangles

The scaling of Agile across Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska has shifted the paradigm on how leadership works. This paradigm shift is reflected in a common visual you will notice in the various meeting spaces where teams gather: the triangle. At first, the visual could be mistaken for the usual pyramid that is often used to depict the dynamics of top-down management. But a closer look at the organization’s triangle reveals that is a symbol for a network of relationships among the three corners of the figure, with a co-equal leader designated for each corner:

The Product Owner, who is responsible for providing clarity and focus to the team around the work to be done.

The Scrum Master, who is responsible for the health of the team and its adherence to Agile practices.

The Technical Lead, who is responsible for guiding the team on how the work is to be done and ensuring it aligns with the Enterprise Architecture.

The triangle is the fundamental fractal that serves as the key dynamic for how Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska works. It is reminiscent of the tripartite leadership approach that has fueled the success of two of the world’s most successful businesses: Google, with its team of Larry Page, Sergey Brin, and Eric Schmidt, and Intel, with its team of Gordon Moore, Robert Noyce, and Andy Grove. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska has found a way to scale this tripartite leadership model throughout its entire organization.

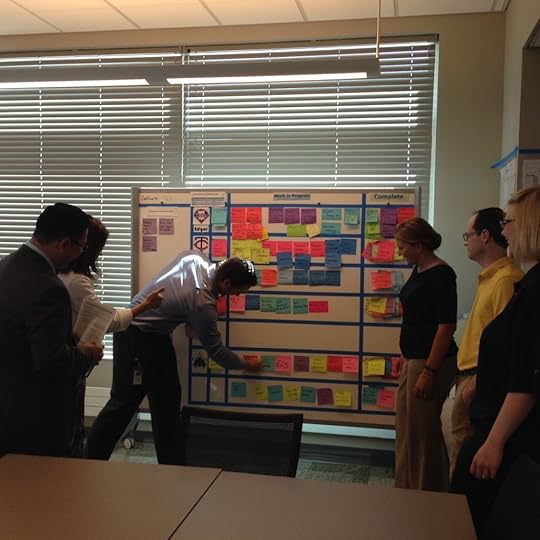

The Importance of Visualization

In addition to triangles, there are many other visuals displayed on the walls of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska. Walk around the building and you will see teams working in open work spaces with walls covered in Post-It notes arrayed in pictures that convey the stories behind their projects. Visualization is a core management concept at the health insurance company. “Visualization is powerful,” explains Courtney, “because it clearly conveys how everyone’s work is interconnected, fosters collaboration, and gives people the tools to effectively self-organize their work.” This concept delivered in a very big way a few years back when the insurer’s computer network went down for five hours while the leaders of the IT organization were attending an off-site meeting. Without waiting for direction, the various on-site teams self-organized their efforts and effectively resolved the computer outage.

In his recent book, How Google Works, Eric Schmidt explains the secret behind Google’s success is a commitment shared among the leaders to hire great people and get out of their way. The scaling of Agile is Blue Cross Blue Shield of Nebraska’s way of applying Google’s wisdom. As Jennifer Richardson, the Senior Vice President of Operations, points out, “We concentrate on providing our teams the vision, or the “what” we need and leave the “how” to the teams. Then it’s our job to build a container in which people are free to do their best work.”

This article was originally published in the Huffington Post.

Rod Collins (@collinsrod) is the Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and the author of Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books)

June 23, 2015

Metadata Maturity Helps You Maintain Business Relevance

by John Horodyski

“Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers” – Calvin Coolidge

Any organization looking to manage and exploit its knowledge more effectively can’t afford to ignore metadata creation. Metadata’s application, however, can’t stop at creation. Organizations must continually update, manage and exploit it in order to provide optimal content and knowledge management opportunities.

Applying the metadata maturity model to content management initiatives provides an agnostic framework through which to understand the current state of metadata, and prioritize its use and management into the future. The model outlines five maturity levels as benchmarks that provide an opportunity to discuss ongoing metadata development and improvement.

What is Metadata?

“Metadata is a love note to the future.” – unknown

Metadata is information that describes other data: data about data. Fundamentally, this includes Descriptive, Structural and Administrative metadataA well-planned metadata schema creates foundational value, providing the conceptual architecture needed to make content more discoverable, accessible and ultimately, more valuable. Metadata turns video, audio or graphic files into “smart content” that is available to re-use, re-purpose or simply to inspire.

Metadata is information that describes other data: data about data. Fundamentally, this includes Descriptive, Structural and Administrative metadataA well-planned metadata schema creates foundational value, providing the conceptual architecture needed to make content more discoverable, accessible and ultimately, more valuable. Metadata turns video, audio or graphic files into “smart content” that is available to re-use, re-purpose or simply to inspire.

The strength and relevance of the metadata associated with an asset is what makes it findable, and therefore usable. When done well, metadata is imperceptible and intuitive.

Providing a Clear Roadmap

A maturity model allows organizations to assess its methods and business processes against best practices by providing external benchmarks. Once an organization identifies where it falls on this course and where it wants to be, stakeholders will have a clearer view of the path to achieving goals.

Business and other enterprise requirements will dictate the importance of reaching the higher benchmarks. Applying a maturity model will not only establish an organization’s placement on the maturation grid but also, and more importantly, provide a precise, actionable roadmap for how to grow and improve.

The Metadata Maturity Model

The metadata maturity model highlights aspects of asset organization that businesses can use to increase information value in an electronic system or between systems. A useful first step in understanding the current state of metadata management is to compare an organization’s commitment level to each aspect.

By taking a self-assessment against five well-defined levels, organizations can start identifying the goals and tasks required to reach the desired future state.

The metadata maturity model includes dimensions of maturity across nine categories and five levels designed to provide a framework for understanding an organization’s use and progress with their metadata and their content. The model suggests graded levels of capabilities, ranging from rudimentary information collection and basic control, through improving levels of management and integration, to finally resulting in a mature state of continuous experimentation and improvement. The breakdown of this structure is as follows:

Maturity Levels

The five maturity levels:

1 Ad Hoc – Exposure to the application of metadata, including managing content and content workflows

2 Organize – Casual understanding of content technologies, often starting in the form of content management systems and centralized, shared document repositories

3 Measure – Demonstrated experience with implementation of content management systems (e.g. DAM, Web CMS, MAM) and core competencies, such as ingestion, cataloging, transformation, transcoding, distribution, etc.

4 Analyze – Managing repositories and workflow systems that are fundamental to business leadership with organized knowledge transfer

5 Optimize – Understanding and forecasting enterprise needs in preparation of future business requirements

Metadata Aspects

Nine aspects contribute to evaluating progress through the model:

1 Files and Folder Organization

2 User Permissions and Access Controls

3 Descriptive Keywords

4 Search Methods

5 Workflow

6 Standards, Policies and Business Rules

7 Rights Management

8 System Integration

9 Reporting and Usage

Metadata Dimensions – the Collections

The vertical columns in the metadata maturity model represent “Collection Levels” or the development levels within an organization where content is managed. This ranges from basic collections, where file-folder hierarchies and pre-assembled collections are the basis for meaning, to curated collections, where meaningful collections organized for anticipated user groups to access, to semantic collections, where audience-relevant content and experiences are assembled and managed as personalized finished digital goods.

Metadata Maturity Level Assessment

Apply the metadata maturity model as a framework to current practice(s) in an organization. Start by documenting the internal stakeholders — across functions and departments — who depend on metadata. Involve IT as early in the process as possible.

Develop and administer a set of questions for stakeholders to provide detailed feedback about their current and desired future state of metadata. These questions should focus on workflow, use, creation, distribution and management as well as key staff roles and responsibilities.

At the end of the exercise, the organization will know its place on the maturity continuum, its strengths and weaknesses and see a clear plan of action to prepare for advancement.

Metadata Serves the Business

“Nothing limits you like not knowing your limitations.” – Tom Hayes

Metadata demands attention for effective business solutions. This model provides a common framework through which organizations can understand the use and management of their content’s metadata.

Applying the model to content management initiatives allows for strategic understanding of current use and priorities for discovery, accessibility and preservation of content. Keeping metadata relevant, usable, clean, consistent and governed will assure that it serves the business.

This article was originally published in CMSWire.com.

John Horodyski @jhorodyski is a Partner within the Media & Entertainment practice at Optimity Advisors, focusing on Digital Asset Management, Metadata and Taxonomy.

June 9, 2015

Records and Information Management: At The Forefront Of Seismic Change

by Gretchen Nadasky

Musty archives and long-winded corporate policy statements can give people the impression that records management is staid and boring when in fact, 2015 is packed with dynamic changes and fundamental shifts that will make the discipline and profession exciting and—dare I say—cutting edge. As we speak, major seismic changes in the business landscape highlight the critical imperative of records management. Organizations that fail to see the importance of these changes will be at the peril of legal, competitive and talent risks. There are three major trends in place that have affected and will continue to impact the records and information landscape:

1) Legal: Changes to Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) effecting litigation expected in December 2015.

2) Big Data: The way organizations are gathering and transforming information into innovation is being repurposed as a competitive weapon. Advances in technology mean that information is being collected and stored on a broad array of devices from mobile apps to watches. Raw data sets, visualizations, dashboards and ‘truth-based decision making’ are tools that drive success in today’s competitive marketplace.

3) The Role of the Records Manager: The importance of having a professional Records Manager participate in business decisions has never been more critical. The role even has its own federal job occupational series codes—a signifier that the demand for records managers is expected to increase. The requirement for knowledge and talent in the field will continue to grow and competition for top talent will escalate.

The time to understand these changes is now!

Legal Change

Up until now, the law has not matched the pace of technological development. The ubiquity of electronically stored information (ESI) has not prompted serious and concerted effort by the Supreme Court to change the regulations around how information must be shared in the course of litigation. Litigators, custodians, and records managers generally agree that current protocols around e-discovery and the definition of spoliation (not producing information as requested) are outmoded and impractical, and have recently formed committees to re-write the rulebook. If approved as expected in December 2015, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure will be amended to balance the need for parties in litigation to produce evidence, taking into consideration the massive volume of information that must be managed.

Organizations should consult legal counsel in anticipation of how changes to concepts such as “proportionality” and production of evidence to support “issues at stake” will affect them and their current procedures. During this evaluation process, companies may also find it opportunistic to adjust outdated policies that have lead to an over-retention of records due to a “just in case” philosophy.

Big Data

It seems like just yesterday that “business intelligence” was the hot buzz phrase describing how companies compiled information into decision-making strategies. Today, “data analytics” more accurately defines how companies are working to digest the tsunami of information collected by sensors, web crawlers, data aggregators and even video feeds. Given the importance of the source data and processes that go into collecting, processing and analyzing what’s popularly referred to as Big Data, policies and procedures around its protection and security are paramount. In addition, with growth rates of data collection increasing exponentially, now is the time to strategize on a retention and disposition policy before the volume of data becomes unmanageable.

The Role of the Records Manager

When computing became ubiquitous, it was believed that computers would automatically self-organize information and that the need for human intervention to manage ESI would be negligible. Records Managers, archivists and librarians were shown the door and a period of digital anarchy ensued, thereby resulting in the information chaos that most organizations are struggling with today. While computers are great at creating and storing vast quantities of information, they neither understand the relative value of information nor have the ability to put information in places where people can readily find it again. The vast amount of information that companies collect and track can be an invaluable tool, but if left unkempt, it becomes a costly liability. Suddenly, organizations are looking for Chief Information Officers and other well-trained professionals to help them deal with the disarray that has become digital information.

Even the US Government has acknowledged that it needs help with its own records and has created both a new role for Records Managers as federal employees and insisted that all government agencies defer to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to help them manage their information. (This is a big deal considering NARA’s annual budget in 2013 was a paltry $391 million compared to another independent agency, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) at $7 billion.) As the role of information in our economy and society increases, the importance of having a professional records manager will be significant. Companies should be proactive in hiring and recruiting talent.

Preventing Mishaps in the Future

As the pressures and opportunities pertaining to the production, analysis and storage of corporate records and data increase, executives must get up to speed on the discipline of information governance. Policies and procedures for handling information must be incorporated with a company’s overall business strategy and planning. A clear understanding of the laws for records production helps frame an organizations responsibilities. Putting policies in place now in foresight of the creation of ever-more data will prevent mishaps in the future. Recruiting talent and placing experienced managers in roles of responsibility will position companies to leverage information and data for competitive advantage. These changes are happening fast and the time to react is today

Gretchen Nadasky is a Manager with Optimity Advisors with a wide-range of experience in leading large enterprise projects in records management, digital asset management and information governance.

June 2, 2015

How Telemedicine And Telehealth Are Improving Health While Cutting Costs

by Greg Cleary

I love hearing about the future of healthcare, even if it sometimes freaks me out. At the recent Workgroup for Electronic Data Interchange (WEDI) 24th Annual National Conference, discussions focused on health information exchange, data collection and emerging healthcare delivery models. At first glance, this appeared to be a standard techie conference with discussions on 834 file layouts and ICD-10 implementations. It turned out, however, to be a whirlwind of innovative discussions, stretching the minds of attendees to use different calculated models of change. Our new healthcare environment has a heavy push from regulators, C-suite executives and consumers to significantly reduce healthcare costs and improve health outcomes. Seemingly benign conversations about futuristic care models have morphed into discussions about evidence-based effects that technology like telemedicine/health have on improving care delivery, cutting costs, collecting health information through new devices, and aggregating information across payers, providers and physicians.

Tele-technologies are today’s reality. Growing sets of telemedicine services are reimbursed by Medicare and almost 90 percent of Medicaid programs and payers are seeing the benefits of implementing the right technologies for their organizations. United Health Group CEO, Stephen Hemsley, said that in an environment where every innovation in healthcare seems to add to costs, “telemedicine has a great future.” Hiliary Critchley of Optimity Advisors and Donald Graf of United Healthcare, teamed up at the WEDI conference to present important insights on the emerging use of these technologies, highlighting the factors healthcare organizations may want to consider when starting a program or expanding their existing programs.

Key Drivers

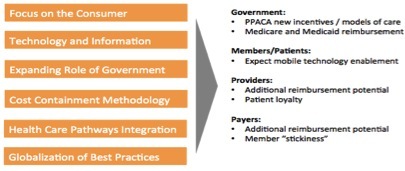

Having all players in an industry pushing for the same end results doesn’t hurt. Level setting our stage, Figure 1 shows key industry drivers that are increasing traction due to market forces and stakeholder dynamics.

Figure 1: Key Tele-technology Drivers

Market Expansion

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced in March that it will expand telemedicine coverage for the newly created “Next Generation ACOs.”

The federally funded State Innovation Model initiative, a creation of CMS, first awarded $300 million to 25 states to design and test “innovative healthcare payment and service delivery models”. Round Two provided more than $660 million to 32 states/territories to both design and test these models.

In addition, 52 percent of large employers plan to cover telemedicine in 2015. The main attraction of telemedicine is its potential to save money and streamline healthcare access. Beyond cost savings, employers can also look to telemedicine to improve employee productivity and reduce absenteeism. Telemedicine visits tend to be less time-consuming than taking time off from work for routine doctor appointments.

A recent online survey of American consumers indicated that 64 percent of consumers are willing to have doctor visits via video telehealth.

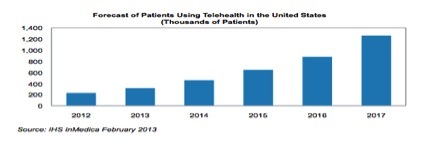

Figure 2: Forecast of Patients Using Telehealth in the US

Understanding Stakeholder Risks

There are concerns around the adoption of telemedicine and mobile health programs from all participants in the field. A few of the major concerns are shown in the figure below.

Figure 3: Major Concerns with Adopting Telemedicine and Mobile Health Programs

Telehealth Coverage by State

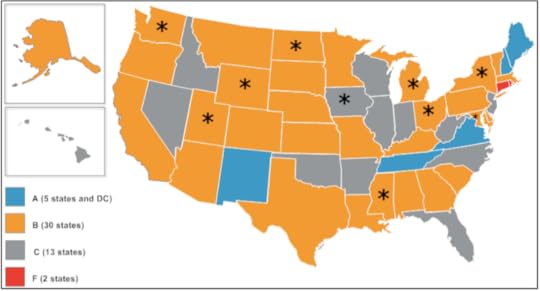

Forty-six states have some form of reimbursement for telehealth in their public program. Only three states currently do not have any written definitive reimbursement policies. Policies vary greatly from state to state. Additionally, strong HIPAA compliance measures need to be put in place to ensure telehealth sessions and/or patient data is not compromised.

Figure 4: American Telemedicine Association’s State-by-State Report Card

Defining Measureable Goals

Identifying and measuring results against a telemedicine program’s goals helps achieve the promise of improving quality and reducing costs.

An organization may want to adopt specific technologies, processes and programs that have measureable impacts to:

Admission diversion and readmission reduction

Disease management

Case management

Utilization management

Health and wellness (patient education and engagement)

Expanding primary care services (nutritionist, care coordination, access to nurse practitioners for urgent care and follow-up)

Adopting Telemedicine/Mobile Health and Telehealth

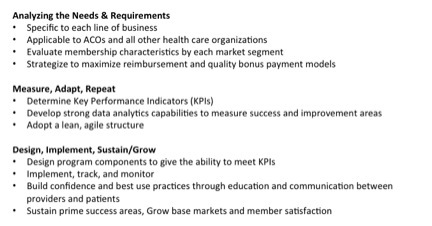

Strategizing, planning and maximizing revenue gain through minimizing costs and increasing quality care lead to valued results. A critical consideration for an organization adopting telemedicine is a clear approach with a clear evaluation of environment factors for each unique situation. Clearly understanding best practices and nuances within specific markets or among populations is a good place to gain some external perspective and insight. Figure 5 shows critical factors to consider when planning a telemedicine/telehealth program.

Figure 5: Critical Planning Factors For Telemedicine/Telehealth Programs

Accelerating developments in the areas of telemedicine, telehealth and mobile health mean it won’t be long before I will be sitting at home, in front of my computer, catching up with my doctor, while my smart watch transmits data to her so she can take a look at the results from the ingestible capsule I took a few days prior. The future of healthcare may be closer than we think.

Greg Cleary is a Senior Manager with Optimity Advisors with more than15 years experience in the healthcare industry specializing in payer operations and technical solutions.

May 26, 2015

Why Innovation Is A Necessity For Twenty-First Century Business

by Rod Collins

Today’s managers face a difficult and unprecedented challenge: The world is changing much faster than their organizations. Every industry, without exception has been overtaken by an accelerating pace of change that shows no signs of letting up any time soon. In a business world of increasing uncertainty, the one clear certainty is that the pace of change is only going to get faster.

As managers struggle to keep pace with a fast-forward world, they are increasingly becoming aware of a very troubling problem. They are discovering that methods and practices that have always delivered predictable results aren’t working anymore. Forecasts are suddenly unreliable as new disruptive technologies radically reshape markets. Cutting costs does not necessarily result in improved efficiencies and productivity. And proven analytical methods are now too slow and cumbersome to keep up with a fast-changing world. In a world where change is constant and longstanding rules don’t seem to work anymore, it’s not surprising that many managers feel overwhelmed by what appears to be a completely unmanageable state of affairs.

However, a fast-changing world it is not necessarily unmanageable; it just needs to be managed differently. According to the management thought leader Gary Hamel, many companies miss the future not because it’s unpredictable or unknowable, but because it’s unpalatable and disconcerting. Nevertheless, if companies are to thrive in world of accelerating change, they are going to need to learn how to manage differently. Rather than leading functional silos, they will need to become comfortable at building well-connected agile teams that are highly capable of innovation.

Innovation Is Connecting Things

Unfortunately, most managers don’t have much experience with leading innovation. They are much more seasoned in the ways of a management ideology where maintaining efficiency and control is the principle focus. However, in times of accelerating change, it isn’t the most controlled or the most efficient organizations that survive, but those that are the most adaptable and resilient. When accelerating change supplants incremental change as the norm, the capacity to innovate becomes essential for business sustainability.

When managers recognize the importance of innovation, their first move is often to set up a new department, put somebody in charge, and hold that person accountable for the new function. However well intentioned, the creation of an innovation silo is a flawed strategy. Innovation is not a department. It is an operating system that values customers over bosses, collective intelligence over individual experts, shared understanding over top-down direction, simple rules over bureaucratic procedures, and transparency over control.

Image courtesy of KROMKRATHOG at FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Becoming innovative means altering the fundamental DNA of a business and its management so that creativity, which the late Steve Jobs defined as the simple ability to connect things, becomes the fundamental fabric of the enterprise. Innovative companies are designed to accelerate the daily cross-pollination of ideas because they understand that innovation isn’t something that’s planned and manipulated; it’s something that’s facilitated and emerges. That’s why the strategic processes of truly innovative companies are inherently iterative and cross-functional.

Moving From Innovation To Innovation

Managing innovation is now a critical core competency for businesses across all industries. Whereas in the past, innovations tended to be more incremental and happened at a more measured pace, today innovation is more constant and clearly more disruptive. For example, in the mobile phone industry, we have had four different market leaders across the last four decades. In the 1980’s Motorola invented the cell phone with its brick-shaped DynaTac phone. The Finnish firm, Nokia, reengineered the product in the 1990’s by building a much smaller easy-to-hold version of the product. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, the Canadian company, Research in Motion, dazzled the market with the Blackberry and became a big hit with businesses by integrating e-mail and telephone into one device. And then, in 2007, Apple completely disrupted and redefined the market with the iPhone, creating a complete telecommunications portal in the palm of your hand.

While each of these four companies created a powerful innovation and quickly became market leaders, with the exception of Apple, none of these companies had the wherewithal to move from one innovation to another. The difference between being innovative and managing innovation is that, while any new entrant can be innovative by creating the next new thing, skillfully managing innovation is about moving from innovation to innovation.

A New World With New Rules

Management, as most of us know it, was invented in the late nineteenth century to guide business leaders in building and preserving sustainable business models, and maintaining highly efficient operations. Its disciplines were designed to support the core values of top-down hierarchical structures: planning, control, and efficiency. Accordingly, in the traditional management model, the fundamental work of the manager is to plan and control, and productivity is synonymous with efficiency.

The managers of today’s most innovative enterprises, however, loathe hierarchical management. The leaders at companies, such as Google, Amazon, and Zappos, are quite proactive in making sure that, as their organizations grow, they do not inadvertently slip into traditional management practices. Instead, they have created a different management model that is based on a completely different set of fundamental disciplines. This alternative model is designed for adapting and innovating rather than preserving and maintaining. Its disciplines support the prime values of learning, collaboration, and innovation. Thus, the fundamental work of the manager is not to plan and control, but rather to be the catalyst for collective learning and collaboration. And productivity is seen more as a function of innovation than efficiency.

A nineteenth century management model is unsustainable in a twenty-first century world. As the pace of change continues to accelerate, it is unrealistic to believe that a century-old management model will somehow endure while the rest of the world is reshaped by the technologies of the Digital Revolution. We live in a new world with new rules, and the old rules are fast becoming obsolete. That’s why innovation is a necessity for twenty-first-century business.

Rod Collins (@collinsrod) is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, 2014).

May 19, 2015

The Evolution of Management Structure: Why Innovative Companies Choose Networks Over Hierarchies

by Bianca Lesmana

During the Industrial Revolution, the manufacturing process rapidly evolved from manual to machine production. As a consequence, mom-and-pop shops gave way to big corporations that employed large workforces with prescribed processes. To sustain efficiency in this new way of working, employees had to be easily trainable and easily replaceable. Because workers were not responsible for designing the prescribed processes, individual autonomy declined.

This method of having workers only be responsible for a part of the production process was called division of labor. It was amazing innovation for its time. It allowed workers to specialize in the small tasks they were assigned and made the overall production process much more efficient.

And so traditional hierarchical structure rose to prominence…

The hierarchical structure of management, popularized during the Industrial Revolution, created a centralization of authority where only a select few were needed to determine the goals of the business. These bosses would instruct their next-in-line managers, who would then command their workers. This structure effectively distributed the production process through a clear chain of command. It was simple; it was structured; and most importantly, it allowed the substitution of autonomous employees for workers who served one function. Hierarchical management made division of labor possible.

In the early twentieth century, bringing people together to communicate was expensive and inefficient. Having information flow in only one direction—from bosses to workers—made things significantly easier to manage. This meant that out-of-the-box thinking was reserved for leaders. Creativity and idea sharing amongst lower level employees was simply not practical. Thus, aside from making division of labor possible, hierarchies allowed large companies to effectively organize themselves with little internal communication or employee feedback; it was the ultimate solution for effectively organizing the work of large numbers of people.

When the world evolved, however, traditional hierarchies could no longer keep up.

The rapid emergence of the internet, at the start of the twenty-first century, brought about a network society that connected markets, competitors, customers, and suppliers. Suddenly, communication became cheap and information flowed freely. Large groups of people from all around the world could easily connect to exchange information, news, and ideas. The arrival of Google, Yahoo, and Wikipedia empowered workers. People were no longer satisfied with being cogs in a machine. They had knowledge at their fingertips and began to crave responsibility and autonomy. The factors that had previously supported hierarchies were displaced by technological developments that strongly favored networks.

The rapid emergence of the internet, at the start of the twenty-first century, brought about a network society that connected markets, competitors, customers, and suppliers. Suddenly, communication became cheap and information flowed freely. Large groups of people from all around the world could easily connect to exchange information, news, and ideas. The arrival of Google, Yahoo, and Wikipedia empowered workers. People were no longer satisfied with being cogs in a machine. They had knowledge at their fingertips and began to crave responsibility and autonomy. The factors that had previously supported hierarchies were displaced by technological developments that strongly favored networks.

As a result, the top down flow of information became an illogical way of doing business. Because everyone had access to knowledge, bosses were no longer necessarily better informed than workers. A pure division of labor, where one worker was entirely disconnected from the tasks assigned to another, also no longer made sense. As communication became affordable and instantaneous, keeping departments siloed was not only unproductive, but, more importantly, inefficient.

The failure of the hierarchical structure in the Information Age led to the rise of the network structure of management.

By taking advantage of the internet’s ability to connect individuals, innovative organizations began building peer-to-peer networks that could quickly respond and adapt to change. The network structure is a more distributed management style that relies on self-organizing teams to make decisions. When problems pop up, workers can fix issues without having to go through multiple channels and are more efficient as a result. Also, because employees have more responsibility, access to more knowledge, and the power to control their own processes, less middle management is required and operational expenses decrease. Companies not only have better, faster, and more invested workers, but also lower costs and higher profits.

By taking advantage of the internet’s ability to connect individuals, innovative organizations began building peer-to-peer networks that could quickly respond and adapt to change. The network structure is a more distributed management style that relies on self-organizing teams to make decisions. When problems pop up, workers can fix issues without having to go through multiple channels and are more efficient as a result. Also, because employees have more responsibility, access to more knowledge, and the power to control their own processes, less middle management is required and operational expenses decrease. Companies not only have better, faster, and more invested workers, but also lower costs and higher profits.

The success of the network structure can be found in many industries, even in traditionally hierarchical ones. Nucor Corporation, a manufacturing company that displayed a very turbulent performance throughout its century-long history, is now one of the largest producers of steel in the United States. In the mid 1960s, Nucor went through an organizational redesign and came out stronger; their solution: network structure. Nucor empowers their workers. Those who actually perform the tasks are the ones who make operating decisions. By having the ability to make their own decisions, workers not only work smarter but also faster.

While building hierarchical structures may have been the logical solution for organizing workers in the Industrial Age, network organizations fare better in the Information Age. By making use of modern technology and communication strategies, the network structure of management is the most fitting organizational structure for the new challenges of a rapidly changing world.

Bianca Lesmana is an Associate at Optimity Advisors.

May 12, 2015

Optimity Advisors At Henry Stewart DAM NY

by Reid Rousseau, Holly Boerner, and Gretchen Nadasky

The annual Henry Stewart Digital Asset Management (DAM) NY conference was held on May 6-8, 2015, and Optimity Advisors was there. After several days of talking everything metadata, taxonomy, governance, and workflow—essentially, all things DAM—here is what stood out to us:

REID ROUSSEAU: As a first-time conference attendee navigating a sea of industry experts, technology vendors and attendees from across industries, I saw the dynamics of the DAM world first hand. I decided to focus on talking to as many vendors and seeing as many system demos as possible—and at the end of the day, here is what stood out:

1) DAMs with clean, modern user interfaces that will attract users to the system by providing an intuitive, friendly experience. Often DAM users are marketers or creatives who possess a sophisticated sense of design, and they bring those expectations to the technology they’re tasked with using.

2) Strong integration with commonly used creative software. Allowing creative users to complete work in their native applications while providing seamless connections to a DAM system is becoming not just a luxury, but a requirement

3) SaaS and Cloud vs. On-Premise solutions. While the energy seems to be trending toward cloud-based solutions, the jury is still very much out as to their long-term implications, the security risks, and asset preservation capabilities.

4) A huge market differentiator lies in systems that provide flexible workflow, approval and project management functionality in tandem with traditional DAM features. The space between an asset as work-in-progress and final, finished entity is rapidly collapsing, and the time when a DAM system could get away with functioning as a silo’d entity focused on final-state asset needs is over.

The most important takeaway is that the needs surrounding organizations’ digital asset strategies can vary immensely, and so organizations must conduct thorough requirements gathering to understand what they need from a system. I guess some of the well-established DAM truths remain firmly intact.

HOLLY BOERNER: I’ve attended the conference for many years and what struck me in 2015 was the maturity present in the presentations, panel discussions, and general conversations happening about DAM. For example:

1) Many conversations this year tilted towards the challenges of being two, five, even ten-plus years into a DAM program. There will always be a need and a place for discussing how to choose an enterprise’s first DAM system, but it is great to see the emphasis evolve toward “How to keep the program invigorated, or how to keep the system evolving along with all technology systems.”

2) Rights Management was everywhere—instead of being treated as a one-off topic, there were multiple sessions that explicitly addressed it, and it additionally popped up as a conversation point in other sessions and conversations. It is invigorating to finally see Rights Management being truly understood as integrally woven into the DAM initiative.

3) Some truths are evergreen: “You can’t underestimate the need for a Cybrarian” was a quote I heard at the conference’s start and it stuck. A DAM program without a dedicated manager and driver is one that faces serious challenges.

The DAM industry is showing its maturation and sophistication, which is thrilling to witness. I can’t wait to see what happens next.

GRETCHEN NADASKY: I found that many of our conversations at Henry Stewart focused on the ability to get funding and staff dedicated to DAM projects—whether just starting out or managing a DAM program many years in.

Garnering support requires a long-term commitment to measurement, communication and positioning the DAM as a key component of the corporate mission. To gain a place at the executive table where resources are allocated, DAM managers can employ several strategies:

1) Gather statistics demonstrating DAM success and document potential risks inherent in not supporting the initiative. Metrics can be woven into casual conversations and formal presentations to educate and build a base of enthusiasm for a DAM program.

2) Identify an advocate in senior management, and show them how the system can provide even more support for their own initiatives.

3) Study and incorporate the corporate mission statement into the DAM program’s roadmap. For example, if the organization strives to grow revenue internationally, focus on ways that the system helps to achieve those goals.

Just as the DAM manager deeply understands that the system doesn’t run itself, he or she must also be aware that institutional support isn’t a given. The place of DAM will only be assured if it is positioned as a key driver of success. It is the responsibility of all the system’s beneficiaries to take part in its promotion—and thus its success.

It was an incredibly successful few days, and we’re already looking forward to what future events will bring! See you all in London in June, Chicago in September, and Los Angeles in November!

Reid Rousseau is a Senior Associate at Optimity Advisors.

Holly Boerner is a Manager at Optimity Advisors.

Gretchen Nadasky is a Manager at Optimity Advisors.

May 5, 2015

User Experience and DAM

by Holly Boerner

I recently had an interesting conversation with a Digital Asset Management (DAM) manager about trying to onboard a new user who hadn’t received formal training. The user quickly became frustrated and the DAM manager in turn expressed annoyance that most DAM practitioners could probably relate to—people need to follow proper training practices and take the time to learn how to use the system if they want to use it successfully.

I’ve been that DAM manager, and I’ve expressed similar sentiments in the past. And on one level, I remain heartily in agreement with the manager’s strategy—user education efforts (along with program governance and communication initiatives) are key to acclimating users to DAM technology.

But on another level, the challenge described here evokes a bigger, longer standing issue native to DAM—why is the DAM user experience so complicated that it requires formal education and communication? Why can’t DAM provide a great native User Experience that is easy and intuitive?

User Experience (UX) is being talked about everywhere in technology these days, as it is increasingly recognized as a fundamental component in the development of websites, applications and general consumer products. User Experience should be understood as the breadth of elements that collectively influence the experience individuals have navigating technology. Ease of use is finally starting to catch on as a priority in DAM as well. DAM vendors and practitioners are coming to recognize UX as an important element with a unique power: the ability to draw users to a system, and by extension, decisively slay the user adoption dragon.

Currently, systems and applications, even more than consumer-facing websites, are being recognized as the entities that demand smart and anticipatory UX. This may seem paradoxical but it is actually quite logical: applications can run circles around websites when it comes to facilitating a wide, diverse functionality landscape. Good UX is key to providing users with that breadth of functionality in such a way as it can be intuitively learned, employed and adopted. For this reason, good UX should be a functional requirement in DAM programs. When user adoption is secured, DAM project goals can be achieved:

Asset discoverability and monetization

Asset use compliance to protect against legal and monetary risk

Analytics-driven insight into asset use and value

UX in DAM is critical to user adoption and DAM vendors are treating it as an 11 on a 1-10 priority development scale.

If you’re curious to learn more about DAM and UX, please read Optimity Advisor’s Orange Paper, UX in DAM. And if you’ll be attending the Henry Stewart DAM NY conference on May 7, come to the breakfast session Optimity will be hosting on DAM & UX.

The good news is that strong, pleasing UX is becoming an achievable goal. This is a welcome development, and a critical step in securing the user adoption and DAM program success that will drive overall business growth and achievement.

Holly Boerner is a Manager at Optimity Advisors

April 28, 2015

Choosing The Right DAM Vendor: Get The DAM Facts!

by Mindy Carner and Laura Kost

Is choosing the right DAM (Digital Asset Management) system akin to choosing the right wine for dinner? Reds with meats, whites with fish? In a word, no. Who says you must adhere to such conventions? Choosing the right vendor is about aligning your goals, vision and requirements so the vendor can become a partner that will provide the technology, vision and support to meet your business needs. While selecting a vendor can often be a complex, intricate process, keeping the below key elements in mind will help ensure you find the right DAM system for your business.

The Approach

When your business decides it’s time for a new DAM, it can be overwhelming to know where to start. But the first step is to define the goals of the DAM program, and use these goals to determine every requirement, criteria and decision throughout vendor selection activities. Once the program’s goals are set, you can proceed to gather business and technical requirements, write an RFI and RFP, and finally, decide a solution’s fit based on the vendor’s system demonstration.

Getting Started – Business Requirements

Requirements gathering is critical to accomplishing a successful DAM Request for Proposal (RFP), as a tool to help truly identify whether a system can meet the goals of the project. Without clearly understood requirements, it is easy to get distracted by a sleek user interface or flashy functionality described during vendor demonstrations. The requirements gathering process should involve interviewing stakeholders across the organization, observing end users conducting their day-to-day tasks, and of course performing general discovery about the assets the system is expected to manage. The requirements gathered during interviews might include:

Workflows

Metadata

User role definitions

Business needs

IT/security requirements

Search and browse

End user adaptability

Use case scenarios

Integration goals

SaaS vs On-Prem vs Private Cloud

Total Cost of Ownership

RFP Evaluation

Once you finalize requirements, it is time to write and distribute a RFP and prepare the business for the selection process. Respondent vendor proposals should be evaluated with a quantitative Scorecard that includes weighted scoring – giving more weight to must-have requirements. About four finalist vendors should be sent functional work packages outlining the Use Cases, Metadata examples, User Roles, and Workflows gathered during requirements, so they can prepare system demonstrations that speak to your business needs.

The Big Day – Vendor Demos

Finally, you will be ready to hold the vendor demonstrations. Here are a few key points to keep in mind for The Big Day:

Evaluating the Vendor Demos

Make sure you see everything you need to see during the demo. Highlight the most important requirements so you can ensure that these have been covered.

Don’t let a meandering, unprepared vendor derail your timeline. If it’s 90 minutes, then it’s 90 minutes … no extra time allowed.

Reformat Use Cases into a list with check boxes to easily track anything that gets skipped. Add space for making notes in case tasks are accomplished through work-arounds, or you need to go back to something.

Avoid evaluation team fatigue by dividing the scorecard into sections for different parts of the team to be responsible for. Evaluators will be overwhelmed if asked to follow along with all use case scenarios.

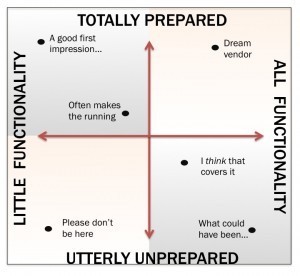

There is a quadrant that evokes the vendor preparedness/functionality fit universe to keep in mind while participating in system demos:

It’s More Than Functionality

Don’t be surprised if capabilities aren’t the only factors to influence the final vendor selection. We have seen clients select candidates based on cultural fit, or a vendor’s stellar customer service, over than system functionality.

Another element that plays a key role in decision-making is Price! An alluring price tag can mean that you end up with the system that doesn’t meet every functionality requirement, so be prepared to compromise, and know what requirements you cannot bend on.

Final DAM Thoughts …

We hope this high level review of an often very complicated and time consuming process helps you as you visit conferences like the upcoming Henry Stewart DAM NY Conference, May 7- 8. As you consider vendors and systems for your business, keep these concepts in mind as you roam the exposition hall. There will be many vendors around demonstrating beautiful user interfaces, optimal metadata capabilities, and even some dolling out fun treats and swag – remember that each vendor has a different ability to meet business needs, and yours are unique, so make sure to ask the right questions and get at the needs that matter most to your users.

Mindy Carner is a Senior Associate at Optimity Advisors.

Laura Kost is a Senior Associate at Optimity Advisors.

April 21, 2015

Four Key Lessons On How Innovation Works

by Rod Collins

There are few business leaders who would deny that we are living in a time of unprecedented innovation. Google and Wikipedia, Facebook and Twitter, iPhones and iPads, Spotify and Netflix—none of which existed a mere two decades ago—have radically changed the way markets work. Toward the end of his life as he contemplated the rapid developments of the emerging digital age, Peter Drucker astutely observed, “If you don’t understand innovation, you don’t understand business.” The need to innovate—and to innovate quickly—has become a business imperative for thriving in a post-digital hyper-connected world, and yet most businesses today struggle in the face of this challenge.

According to Steve Denning, the principle reason that many U.S. firms are struggling or dying is a failure to innovate that stems from a lack of commitment and resources to cultivate new ideas and pursue innovations capable of keeping pace with a more competitive global marketplace. If Drucker and Denning are right in their assessment of the importance of innovation, filling this resource gap may very well be job one for today’s business leaders.

Walter Isaacson’s latest book, The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution provides important insights into what business leaders need to do to install the processes that naturally enable innovative workplaces. Isaacson’s comprehensive overview of the emergence of the digital age is as much a story about management evolution as it is about technological revolution. While Isaacson chronicles the back-stories behind the development of physical devices, such as the transistor, the computer, and the Internet, he also sheds light on the creation of new organizational structures that serve as the incubators and the accelerators of innovation. The “invention of a corporate culture and management style that was the antithesis of the hierarchical organization” is the context, without which, the content of innovation may have never happened. Perhaps the reason so many companies struggle with innovation is because they are operating from the wrong context.

Walter Isaacson’s latest book, The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution provides important insights into what business leaders need to do to install the processes that naturally enable innovative workplaces. Isaacson’s comprehensive overview of the emergence of the digital age is as much a story about management evolution as it is about technological revolution. While Isaacson chronicles the back-stories behind the development of physical devices, such as the transistor, the computer, and the Internet, he also sheds light on the creation of new organizational structures that serve as the incubators and the accelerators of innovation. The “invention of a corporate culture and management style that was the antithesis of the hierarchical organization” is the context, without which, the content of innovation may have never happened. Perhaps the reason so many companies struggle with innovation is because they are operating from the wrong context.

Among the many lessons that Isaacson draws from understanding the dynamics of how innovation works, there are four key lessons that may help business leaders close their innovation gap.

1. Collaborative Teamwork

Innovation is a collaborative process and teamwork is its essential skill.

“Innovation comes from teams,” according to Isaacson, “more often than the lightbulb moments of lone geniuses.” This is perhaps the one most important observation about how innovation works. The context for innovation has more to do with leveraging the collective intelligence of the many than with relying on the individual intelligence of the few. Teams that excel at innovation tend to be collegial and typically bring together people with a wide diversity of skills. Whereas traditional organizations organize by departments of similarly skilled workers under the direction of single supervisors, innovative organizations tend to organize by project in more self-managed structures that are better suited for enabling the serendipity that is often the fuel of innovation.

Teamwork is the essential skill because innovation is, at its core, a collaborative process. While traditional leaders recognize the need for collaboration—as noted in a recent IBM CEO study that found that 75 percent of CEO’s identified collaboration as the most important organizational attribute—the same study found that most of them are not quite sure what to do to transform their organizations into collaborative enterprises. As long as they remain unsure, their organizations are likely to be disadvantaged in a rapidly changing world

2. Distributed Power

Innovation is more likely to thrive in organizations where power is distributed rather than centralized.

Isaacson notes, “The Internet was born of an ethos of creative collaboration and distributed decision making.” This ethos runs contrary to the fundamental norms of traditional hierarchical structures where power is centralized at the top. It is not surprising that leaders are challenged when it comes to building collaborative organizations because embracing collaboration inevitably means enabling distributed decision-making, which doesn’t come naturally to leaders schooled in the dynamics of command and control.

The problem with maintaining centralized power in fast-changing times is that business leaders are prone to miss innovative breakthrough opportunities because they are far more comfortable with attempting to preserve the status quo than they are with adapting to new emergent realities. Isaacson points to the example of Xerox, whose leaders were not equipped to handle a radically new innovation—a rudimentary personal computer—created by their own research and development team. If the Xerox organization had been more of a network of distributed authority, such as Google is today, the history of the personal computer could have been very different. According to Isaacson, “Xerox could have owned the entire computer industry.” Instead, they ceded this opportunity to Steve Jobs, who on a chance visit to the Xerox R&D facility, recognized the possibilities of an amazing new technology.

3. Complementary Styles

The best leadership of innovation comes from teams that bring together people with complementary styles.

A key finding that Isaacson observed in his study of innovative organizations is that, in building leadership teams, they were highly effective in pairing visionaries with people who could execute innovative ideas. Isaacson cites the example of Intel, founded by two visionaries—Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore—whose first hire was Andy Grove, a disciplined manager who knew how to install operating procedures and get things done.

The leadership at successful innovative enterprises rarely emanates from one strong leader. Instead, it “comes from having the right combination of different talents at the top.” In addition to the threesome at Intel, another example of effective tripartite leadership is at Google, where Larry Page, Sergey Brin, and Eric Schmidt have combined their skills to build one of today’s most innovative businesses.

Another way that leaders can bring together complementary styles is by building crowdsourced organizations, such as Wikipedia and Linux, that provide the framework for a diversity of people to combine their talents in self-organized structures where the leadership team emerges from the interactions of the participants. While Jimmy Wales and Linus Torvalds are the recognized leaders of their respective ventures, neither of these two visionaries maintains tight control over their innovative enterprises.

4. Learning Systems

The most important development of digital age innovation is the human-machine symbiosis that has transformed the essential orientation of all systems from programming to learning.

This fourth lesson is significant because it undercuts the fundamental dynamics that have defined the way large groups of people work together. Human-machine symbiosis began in the Agrarian Age when humans first built tools to ease the burden of physical work. This symbiosis catapulted to a new dimension with the advent of mass production. The human-machine symbiosis of the Industrial Age was almost Borg-like where large numbers of people interacted with their machines and each other in rigidly prescribed ways. This form of symbiosis led to the creation of the command-and-control structures that have defined the practice of management for over a century. The basic orientation of these management systems is prescribed programming where workers are presented with fixed plans and incentives are put in place to make sure they don’t deviate from the program.

With the advent of the Digital Age, the human-machine symbiosis has once again catapulted to a new dimension that can be best described as mass collaboration. Isaacson observes that today’s computer technology “augments human intelligence by being tools both for personal creativity and for collaborating.” As a result, the symbiotic relationship is an iterative learning partnership that combines the strengths of both humans and machines. While machines can collate information incredibly fast, humans are better at the intuitive skills of sense-making and pattern recognition. Isaacson points to the example of the Google search engine, which rapidly collates the individual judgments of billions of people to provide sensible search results. He notes, “the collaborative creativity that marked the digital age included collaboration between humans and machines.”

An Emerging New Management Model

Filling the innovation resource gap requires a rethinking of a century-old management model that has been the foundation for how things get done in large organizations. Fixed plans and tight controls are of little value in a world that is rapidly changing. Instead, business leaders need to heed the four key lessons of the innovators to guide them in transforming their management structures into highly effective learning systems where collaborative teams blend complementary styles to exercise distributed power in serving the needs of their customers. To do so, business leaders will need to operate from the right context, embrace the emerging new management model of the innovators, and organize themselves as collaborative networks rather than top-down hierarchies.

Rod Collins (@collinsrod) is Director of Innovation at Optimity Advisors and author of Wiki Management: A Revolutionary New Model for a Rapidly Changing and Collaborative World (AMACOM Books, 2014).

Rod Collins's Blog

- Rod Collins's profile

- 2 followers