Carl Zimmer's Blog, page 16

February 7, 2014

How Do You Know When You’ve Found Them All? A Question That Applies To Beetles and Cancer Genes Alike

A big part of what biologists do is to catalog the diversity of life. That diversity can take many forms. There are hundreds of thousands of species of beetles on Earth, for example. There are also some untold number of genes in the human genome that play a part in cancers of different types.

In his early years, the Nobel-Prize winning biologist James Watson infamously derided nature’s catalogers as “stamp collectors.” Simply creating lists didn’t seem to get at the heart of things–like the structure of DNA, which Watson helped decipher. But it’s impossible to fully understand nature only by taking it apart into its smallest parts. An organism is a sum of those parts, as is an ecosystem or a biosphere. Watson implicitly acknowledged that fact when he became the first director of the Human Genome Project, which sought to sequence all our genes. The catalog itself–whether it’s a catalog of plant species in a forest, or bacteria in a microbiome, or genes in a genome–doesn’t automatically reveal insights on its own. But scientists can explore a catalog to test their ideas about large-scale biology.

Right now, cancer biologists are in the midst of a similar catalog project. They are spotting cancer genes by examining the genomes of cancer cells and comparing them to the genomes of normal ones. So far, they’ve identified roughly 150 such cancer genes. Presumably there’s a finite number of such cancer genes, and some scientists argue that knowing them all would give cancer research a huge boost. We could, in effect, get to know all the tricks in cancer’s bag.

But, as I write in my latest “Matter” column in the New York Times, scientists may have a long way to go to finish such a catalog. A new study suggests that scientists will need to examine 100,000 cancer samples–about ten times the number they’ve looked at so far–to get close to finishing it.

One thing that I found fascinating in working on this column is the method that the scientists used to estimate how much work remains. You might think that was an unknowable answer. It’s as if cancer biologists are walking on a foggy road at night, with a flashlight casting a beam that only reaches a few feet ahead. How can they know how far they have left to go until they get to the end of the road?

What the scientists did in this case is look at the genes they had found so far. They randomly picked out cancer samples, creating sets of various sizes. If they were close to finding all the cancer genes, they’d expect that the more samples they looked at, the fewer new genes they’d add to their list.

It turns out that other scientists use similar methods to gauge how much diversity remains to be discovered. Scientists who are cataloging the residents of our gut chart their curve of discovery to see if it’s reaching a plateau. And, as I wrote in the Times in 2011, biologists use a similar method to estimate the total number of species on Earth, based on the history of discovery up to this point.

I was surprised to discover this link between these different catalogs. But in hindsight, it makes sense. Cancer biologists and beetle experts are not all that different when you think about it. They walk the same foggy road together, a long way from the end.

February 4, 2014

A Living Nest?

When we think of a nest, we think simply of a natural piece of construction. A bird gathers together twigs and stems and leaves and assembles them into a shelter for its eggs. We don’t think much about the plants it uses. They’re just building material.

But in at least some cases, there may be more to a nest than meets the eye. It may be a cooperative breeding project, produced by two partners–animals and plants.

Firecrown hummingbird in nest. Copyright Felipe Rabanal

Francisco Fonturbel, an ecologist at the University of Chile, and his colleagues study the green-backed firecrown hummingbird, the range of which stretches across the forests of Chile and Argentina. As you can see from this picture, it builds a peculiar nest that looks as if it’s made of green, glistening noodles.

It turns out that the hummingbird builds its nests mainly out of ferns and mosses. This might seem rather fussy on the part of the bird. In reality, it’s even fussier. When Fonturbel and his colleagues examined 30 nests, they found that the birds had selected material from just a handful of species of ferns and mosses, while passing over other species growing on the trees in their forests.

And when the hummingbirds visit their favorite fern or moss, Fonturbel and his colleagues found, they don’t just pick any random piece of the plants.

Ferns and mosses evolved before the emergence of seeds. To reproduce, they produce male and female sex cells that act like animal sperm and eggs. The sperm fertilize the eggs, which then develop into structures (called sporangia or sporophytes) that produce spores. The ferns and mosses then release the spores, which can then float away in the wind or in water to produce new plants.

Fonturbel and his colleagues found that the firecrown hummingbird prefers to take the spore-filled structures from particular species of ferns and moss to build their nests. These pieces of the plants stayed alive after the bird made them part of its nest. When the scientists revisited 21 of the nests a year later, the plant fragments were still making new spores.

The scientists propose that the firecrown hummingbird and the ferns and mosses it prefers are entwined in an intimate give and take. The ferns and mosses supply the birds with the material they need to build their nests. But this is not a botanical act of altruism. The ferns and mosses may be benefiting because the birds are selecting the parts of their anatomy that contain their genetic legacy.

A bird picking up a piece of a fern or moss can potentially transport it further than it could on its own. It may be especially valuable for the plants to end up in nests that sit high in trees. Their spores can then rain down on a wide patch of the forest floor. Spreading across a bigger range, the plants may be able to mate with a wider range of other plants, and become more resistant to becoming extinct.

Plants depend on animals to spread their seeds in many ways. Some plants, for example, grow fleshy structures on their seeds that attract ants. The ants take the seeds to their nests and eat the fleshy parts, leaving the seeds to sprout. Other plants produce big fruits that mammals or birds can feed on. The seeds survive the journey through the gut and get spread out in the droppings of the animals.

The hypothesis that birds can also spread plants by building living nests will need to be tested. Are the plants better off with the birds picking their reproductive anatomy than if there were no birds? Have the plants evolved any strategies to make their spore-bearing structures better material for nests? Do they lure the hummingbirds with special odors?

If these investigations bear out, it might be worth checking out other species of birds. Perhaps there are more nests out there that are producing not just new birds, but new plants.

Reference: Osorio-Zuniga et al., “Evidence of mutualistic synzoochory between cryptogams and hummingbirds,” Oikos 2014

January 29, 2014

Neanderthals: Intimate Strangers

For my new “Matter” column in the New York Times, I look at the latest advance in our understanding of Neanderthal DNA. Neanderthals and humans interbred about 40,000 years ago, and their DNA is still in human genomes today. Scientists are mapping those Neanderthal genes we carry, and figuring out which ones have benefited us and which have made us sick.

One thing I didn’t have room to discuss is a question that I keep asking and to which scientists always respond with intriguingly noncommittal answers: Are Neanderthals members of our own species? Are they Homo sapiens? Are they a subspecies–Homo sapiens neanderthalensis? Or are they a separate species–Homo neanderthalensis?

For much of the 1900s, many scientists saw Neanderthals as the ancestors of living Europeans. But then in the late 1900s, some researchers argued that living humans descended from a small group of Africans that expanded out to the rest of the world. The discovery of Neanderthal DNA has wonderfully muddled that dichotomy. Humans and Neanderthals, the DNA suggests, share a common ancestor that lived 600,000 years ago. After hundreds of thousands of years, they came into contact and interbred. The fact that we carry some Neanderthal DNA shows that their hybrid offspring could have children of their own. One could argue that this ability to breed means that we belong to the same species. Perhaps we’re just subspecies that came to look different because we adapted to different conditions–Africa versus Eurasia.

But the latest evidence adds a new twist. Many genes from Neanderthals appear to have reduced the number of offspring that hybrids could have. That would explain why big segments of the human genome are free of Neanderthal DNA.

Why these genes were harmful isn’t yet clear, but the clues are fascinating. Take FOXP2, a gene involved in language in humans. Neanderthals have FOXP2 as well, but natural selection appears to have eradicated their version from the human gene pool. Did humans with the FOXP2 have trouble speaking? There are other clues that Neanderthal genes created infertile male hybrids. These effects didn’t have to be catastrophic to lead to the disappearance of Neanderthal genes. They might have just eroded away over many generations.

There are no known reproductive barriers between any living humans, no matter how distantly related they are to each other. These barriers are crucial to the origin of new species (although they can still allow some populations to interbreed even after millions of years). So perhaps we can say that Neanderthal, while not a separate species, were well on their way to separating.

January 25, 2014

Memoirs by Scientists: A Crowd-Sourced List

I’m reviewing a memoir by a scientist, and it’s gotten me reflecting on this peculiar sub-genre. I started thinking about especially good examples–in particular, ones that manage to balance the personal experiences of the author with the professional accomplishments. I ended up thinking aloud about it on Twitter, and ended up with a spontaneous reading list that had some usual suspects but also some intriguing surprises. Here it is (Note: Please be sure to click the blue bar labeled “Read Next Page.” There are a lot more!)

[View the story "Memoirs by scientists that successfully combine the professional and the personal" on Storify]

January 24, 2014

Stepping off the Spaceship

Recently a producer from the radio show Studio 360 called me up to talk science fiction. They wanted to throw a light on some of the artists who gave us the pictures we have of other worlds–of what we see when we step off the spaceship.

It just so happens that I grew up knowing one of them, named Jack Schoenherr, so I threw his name in the hat. It turns out that Studio 360 also runs a series of pieces called “Aha Moments” about experiences with art that change people’s lives. So we decided to combine the two, and I talked about what it’s like to be a ten-year-old boy walking into a barn studio full of giant sandworms and elephants and astronauts.

The piece is airing this week. You can listen to it on the Studio 360 web site and check out a slide show of a few of Schoenherr’s paintings. I’ve also embedded the piece below [Note--the sound isn't working in this embedded version on Safari at the moment, but it is in Chrome and on the show site.]:

For more on Schoenherr, see this remembrance I wrote when he died in 2010, or head over to a blog maintained by his son Ian, himself an accomplished children’s book illustrator.

[image error]

John Schoenherr, “The Flight through the Shield Wall.” Courtesy of Ian Schoenherr

January 23, 2014

How A Dog Has Lived For Eleven Thousand Years–In Other Dogs

When I was eleven, we buried my first dog under an apple tree. We got another one soon after, and he died about a decade later while I was away at college. That was a pretty typical experience when it comes to kids and dogs. In a study published last year, British researchers found that the median lifespan of a pet dog was all of twelve years. Dogs can be fine companions over the course of a human childhood, but they are hardly Methuselahs.

There is, however, one remarkable exception. A dog that was born 11,000 years ago stumbled across the elixir of life, and is still alive today. It didn’t find immortality through a diet of mung beans or daily doses of resveratrol. Instead, that ancient dog employed a more radical solution. Some of its cells became cancerous and invaded other dogs, and those dogs then spread its cells to still other dogs. That ancient dog lives on today in the bodies of countless dogs around the world today.

The first record of this immortal dog appeared over 200 years ago in a book called A Domestic Treatise on the Diseases of Horses and Dogs, published in 1810 by a British veterinarian named Delabere Pritchett Blaine. Blaine had seen dogs with a kind of cancer that he described as “an ulcerous state, accompanied with a fungous excrescence” that arises in “organs concerned in generation.”

Veterinarians became more familiar with the cancer in the following decades. A tumor the shape of a cauliflower would appear around a dog’s genitals, growing quickly and becoming prone to bleeding. Some dogs died from the cancer, although many of others experienced a remarkable cure: after a few months, the tumors spontaneously shrank and vanished on their own, never to return.

In 1871, a Russian veterinarian proved that these tumors were actually infections. He cut off a bit of a tumor from one dog and then rubbed it around the genitals of another. The second dog got cancer, too. Like the bacteria that cause syphilis or the virus that causes AIDS, the cancer took advantage of sexual contact to spread to new hosts. Since then, canine Transmissible Venereal Tumor, or CTVT for short, has turned up in dogs on every continent.

CTVT remained an obscure condition known only to vets for decades. But it has gained a scientific celebrity in recent years, as scientists have started to examine the DNA in the cancer cells. If CTVT was an ordinary form of cancer, the DNA in a tumor would be a modified version of the DNA in the dog’s healthy cells. But CTVT is far from ordinary. The DNA in one tumor is very similar to the DNA in other tumors–even tumors growing in dogs on the other side of the world.

To get a deeper understanding of this cancer’s remarkable history, a team of scientists led by Elizabeth Murchinson of the University of Cambridge has now sequenced two entire CTVT genomes for the first time. They published their analysis of the genomes today in the journal Science.

Murchison and her colleagues selected two sick dogs from opposite ends of the canine universe for their study: one is a so-called “camp dog” that that live alongside Australian Aborigines. The other dog is a cocker spaniel in Brazil.

As distant as the two dogs might be, their cancer cells are very similar. Murchison and her colleagues found that their genomes share about two million mutations in common that are not found in ordinary dog cells That staggeringly huge collection of mutations is a powerful arsenal of evidence that the tumors descend from a common ancestor, rather than having evolved independently from normal cells in different dogs.

Those mutations also gave Murchison and her colleagues a molecular clock they could use to estimate how long ago the cancer originated from an ordinary dog cell. When cancer cells grow and divide, some of their DNA mutates at a roughly regular rate. In an ordinary tumor in humans, a few thousand of these mutations might accumulate. The two million mutations found in the CTVT genomes show that they’re far older than a few years. In fact, they suggest that the cancer originated in a dog 11,000 years ago, just as the Ice Age was ending.

In the past, scientists have debated whether CTVT got its start in a dog or a wolf, which then mated with a dog. This new research settles that debate in favor a dog. And not just any dog. The cancer cell genomes are most similar to those of huskies and Alaskan malamutes, which belong to one of the oldest lineages of domesticated dogs.

Here, then, is how it seems that a malamute-like dog got to live forever. One of its immune cells turned cancerous and grew into a tumor somewhere around its genitals (Murchison and her colleagues can’t say if the dog was male or female). Inside that original dog, the cancer accumulated hundreds or thousands of mutations. When the dog mated, some of the cancer cells from the bleeding tumor slipped into the body of its partner.

Normally, this should have been the end of the story. Immune cells in the second dog should have recognized the foreign cancer cells and wiped them out. Murchison and her colleagues suggest that this didn’t happen because the dogs belonged to an early population that was very small. Small populations can also be very inbred, with little genetic diversity. That similarity may have made it hard for the immune system of the second dog to distinguish the cancer cells from itself. The cancer cells exploited this loophole and grew in their new host. When the second dog mated with a third, the cancer spread further.

Along the way from dog to dog, the cancer continued to evolve. As the cells divided, some picked up mutations that allowed them to grow faster than others. The cancer adapted to its new way of life as a parasite. As it spread out of its original population, it evolved new deceptions to escape the notice of other immune systems, enabling it to infect other breeds. And it has never lost its ability to grow, even as a thousand generations of dogs it inhabited have died. (One source of its immortality may be its ability to steal energy-generating factories from the cells of its hosts.

Intriguingly, Murchison and her colleagues found that relatively few mutations are unique to the two tumors. The scientists estimate that the two tumors share a common ancestor that lived just 460 years ago. That’s around the time that dog breeders produced many of today’s breeds. It’s also when Europeans started colonizing many parts of the world, bringing their cancer-laden dogs with them. We have created propitious conditions for the global spread of a contagious cancer.

As sinister as CTVT may seem, it could be a lot more dangerous. You need only compare it to the only other known example of contagious cancer in the wild–a facial tumor that is spreading among Tasmanian devils. Like CTVT, the devil’s tumor spreads by taking advantage of the contact Tasmanian devils make with each other–instead of mating, they spread when the devils bite each other in the face during fights. But they’re drastically different in how they affect their host. CTVT typically disappears spontaneously from dogs. The devil’s tumor can balloon so fast that it often kills a Tasmanian devil in a matter of months.

While CTVT arose 11,000 years ago, the devil’s tumor only evolved in the 1980s. And yet its virulence is now threatening to drive Tasmanian devils to extinction within the next few decades unless the epidemic can be halted. It’s possible that dogs suffered such a brutal outbreak when CTVT first emerged, but the cancer has evolved a different strategy, spreading without being so deadly. It’s possible that Tasmanian devils will be saved by the same taming of their cancer. Unfortunately, we’ll know within a couple generations whether that happens or not.

Here are two videos about contagious cancer–first a talk I gave last year in San Francisco, and then a TED talk by Murchison

January 22, 2014

Let Us Take A Walk In the Brain: My Cover Story For National Geographic

White-matter connections in my brain ( Van Wedeen and colleagues at Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging)

Over the past year, I’ve spent a lot of time around brains. I’ve held slices of human brains preserved on glass slides. I’ve gazed through transparent mouse brains that look like marbles. I’ve spent a very uncomfortable hour having my own brain scanned (see the picture above). I’ve interviewed a woman about what it was like for her to be able to control a robot arm with an electrode implanted in her brain. I’ve talked to neuroscientists about the ideas they’ve used their own brains to generate to explain how the brain works.

This has all been part of my research for the cover story in the current issue of National Geographic. You can find it on the newsstands, and you can also read it online.

On Monday, I was interviewed on KQED about the story, and you can find the recording here.

National Geographic has been doing a lot of interesting work to adapt their magazine stories for the web and tablets. For my story, the great photographs from Robert Clark are accompanied by some fine video.

Here’s one of my favorites–an interview with Jeff Lichtman, a neuroscientist Harvard. He’s one of the people I interviewed for the story, and it was an inescapable torture to have to boil down our conversation to fit there. In this video, an unboiled Laitman talks about his project to see everything in the brain, with some of the mind-blowing visualizations he and his colleagues have created. I think these images are the clearest proof of just how big a task neuroscientists have taken on in trying to map the brain and understand how it works.

January 21, 2014

X Marks The Genetic Mystery

In today’s New York Times, I have a feature about the X chromosome. The X chromosome is one of those things that we learn about early on in school, and yet it still contains mysteries–ones that potentially have a direct impact on our health. Men have one X chromosome and one Y, while women have two X’s. This imbalance has led to all sorts of remarkable things–most remarkable of which is the fact that women shut down one of their X chromosomes–but which chromosome (mom or dad’s) depends on the cell.

I explore several lines of research in this piece, but the original nudge came from one new study in particular. Jeremy Nathans of Johns Hopkins and his colleagues came up with a way to light up cells based on which X chromosome they used. The complexity is gorgeous.

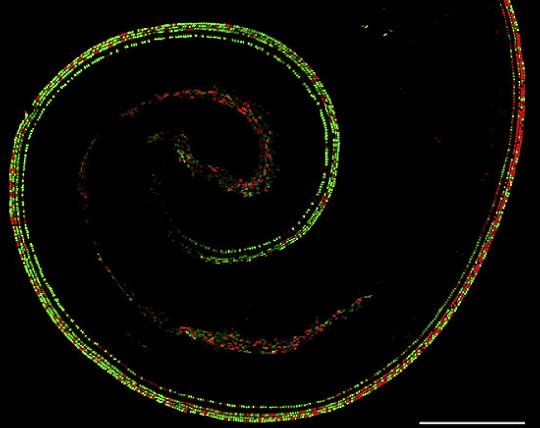

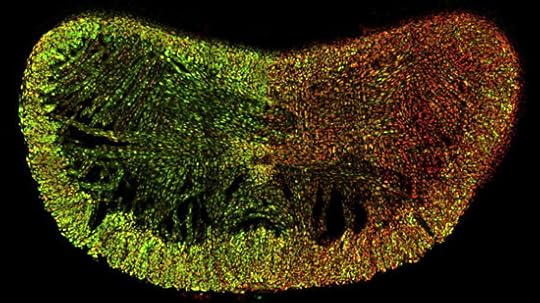

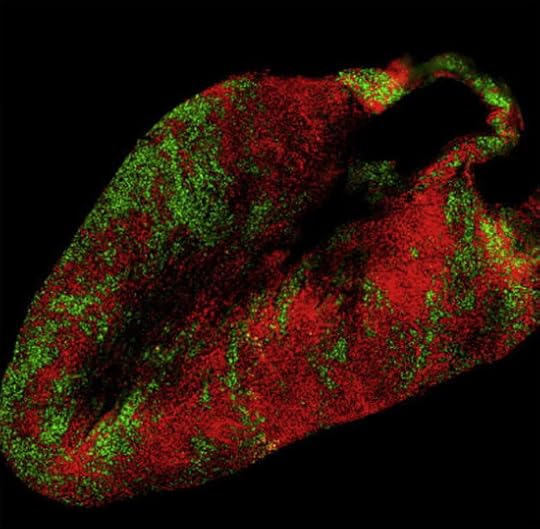

Here are three images that we didn’t have room for in the news article. Red cells use the father’s X, green cells the mother’s. Bear in mind that each chromosome carries different versions of the 1,000+ genes on the X. What these patterns mean for female biology is anyone’s guess.

First, an auditory hair cell from the inner ear of a mouse:

Jeremy Nathans and Hao Wu/Neuron

Then the tongue in cross-section (note the side-to-side differences):

Jeremy Nathans and Hao Wu/Neuron

And, finally, the heart:

Jeremy Nathans and Hao Wu/Neuron

January 20, 2014

Opening the Black Box with Radiolab

It’s always a pleasure to talk with Jad Abumrad and Robert Krulwich and their crew at the show Radiolab. For their latest episode, “Black Box,” we talked about the mystery of consciousness and how I got in an argument with my anesthesiologist before I had my appendix taking out.

I’ve embedded the whole episode here:

Anesthesia is deeply fascinating, even if you’ve never gone under, because it brings us face to face with the mystery of consciousness. I’ve written about it here and here.

January 19, 2014

The Predicted Tattoo (Science Ink Sunday)

This is an image of a hawk moth and Darwin’s orchid. It spoke to me for its history, beauty, and simplicity, as well as its significance in demonstrating the predictive power of Darwin’s theory of evolution by means of natural selection. This orchid (Angraecum sesquipedale) is endemic to Madagascar and has an unusually long spur (20-35cm), where it keeps its nectar. Charles Darwin predicted in 1862 that even though a moth with an equally lengthy proboscis had not yet been discovered, one must exist in order to pollinate the orchid. Alfred R. Wallace supported this hypothesis in an 1867 paper. The moth, Xanthopan morganii [praedicta] was discovered in Madagascar in 1903, well after both men had passed.

I have been a lover of biology practically since birth. I got a BS in Physiological Science and am now completing a PhD in History of Science. While my specific work is not in the history of biology and evolution, it’s my A-#1 nerd passion (well… a tie with science fiction). A little less quietly, I’m a little proud of myself for getting this beauty in Texas, the week the State Board of Education asked a panel of reviewers (many of whom believe in or are sympathetic to creationism) to review biology textbooks.

The BBC told the story of this remarkable moth (and remarkable prediction) in their show, Museum of Life:

You can see the rest of the Science Tattoo Emporium here or in my book, Science Ink: Tattoos of the Science Obsessed. (The paperback edition comes out in May; you can pre-order here.)

(Tattoo artist: El Sando at Dovetail Tattoo, Austin, TX)