Christopher Steiner's Blog, page 3

November 17, 2016

The Top Gear Pieces For Winter 2017

This used to be called the Top 5 gear pieces, but we’ve expanded. We’re keeping the logo for posterity.

This is the gear that caught our eyes at trade shows and on the hill:

Arc Teryx Proton AR Hoody – $349

Arc Teryx has a knack for outerwear, especially jackets and insulation, that nobody else seems able to match. The company that started with harnesses and packs continues to set the agenda in the business of keeping warm and dry. The Proton hoody is part of that lineage. It’s the piece you need for a ski trip that gives your kit that extra kick of warmth for those 8:30 a.m. lift rides, but won’t kill you with your own sweat emissions after lunch. And when you’re chasing last chair toward 4:00 p.m. and the light is going dim and the temperature is dropping, this hoody stays warm, even if you’ve gotten a little damp. It does all of this with a mix of Coreloft™ Continuous 65 and Continuous 90 insulation. It’s also the perfect piece for throwing on as you heading to the store to grab fixings for a massive pot of chili or standing on the snow, after the closing bell, drinking tall boys. Swiss army knife of insulation.

Atomic Hawx 130 – $850

The best resort boots are stiff as hell, which allows riders to carve up groomers and make turns in tight glades on a dime. But what happens when that same skier wants to bootpack the headwall at Jackson Hole? They get hammered by their lead-filled Neil Armstrong-approved horseshoes. Their buddies, wearing their wimpy AT boots, scale up the ridge quickly and laugh and point at Mr. Alpine Boot. And then when it comes time to rip, when the alpine boots’ advantage can be fully leveraged, the skier is worn out from transporting an additional 20 tons on each foot up the side of a knife-edge boot pack at 11,000 feet. A sad situation. Enter the Atomic Hawx: restoring the balance of power for alpine booters. It’s the lightest four-buckle boot that skis like, yes, a four-buckle boot. And that 130 in the name? Yeah, that’s the stiffness quotient. These boots are far more tilted toward Hermann Maier than they are toward wanky dudes whose form is only good enough for backcountry powder turns. So get mean, and get light, and have it all.

Trew Midweight NuYarn Merino Chill Top – $115

Trew has developed a new way to make fabric that isn’t the same old thing that we’ve been doing since the industrial revolution. The reason you should care: Trew’s yarn has no twists in it, which is what makes wool, even the super soft stuff, just a tad prickly on the skin. Don’t tell us you don’t feel that little sting. It’s there. But not with this stuff: NuYarn is 38.9% loftier, 35% stretchier, 5x faster drying, 25% warmer and 16% stronger than normal wool yarn. This is the cold fusion of wool. The Chill Top brings together a blend of 58% NuYarn and 42% polyester to make the most fantastic next-to-skin insulation piece on the market. You can only buy Trew straight from Trew, which saves you all that margin that normally goes to some soulless e-commerce website.

Scarpa Freedom RS – $850

Need that AT boot that can double as an in-bounds ripper but still keep you fleet of foot skinning up? The Scarpa Freedom RS is the preeminent boot for doing it all. This won’t be as stiff as a burly alpine boot, but it will allow skiers to drive a big ski of more than 100 mm underfoot. In walk mode, the boots have lots of motion freedom and let tourers crank up the comfort. The liners are heat-moldable, which gives skiers a chance to get a good feel and packed-out impression of the boot early on. They come with a hefty power strap that reminds one of an old Nordica Doberman with that two-inch strap locking things down. Great boot for backcountry peeps concerned with performance but who aren’t bent on climbing 10,000 feet a day.

Getting to your destination

Part of the ski trip we don’t talk about much is the part that requires going to the airport, schlepping to and fro with 150 lb of *essential* gear, figuring out how to get that ski bag onto the subway, etc. First a tip on the ski bag: if you don’t have a way of checking your bag for free—airline status, airline credit card, premium ticket—then it’s not worth paying the airline. Just ship your skis via UPS or Fedex Ground to your destination. Give them four to five days of a head start, of course. Stuff your bag with everything it can hold. The goal here is to not take anything to the airport other than a small backpack. Anything bigger these days will cost you money, even on United, as it just announced.

When you arrive at your destination airport, you’ve nothing to pick up. Just keep rolling all the way to your lodging, be it a hotel or condo. Your bags will be waiting for you. That 50-lb limit thing? Not a problem, as the freight carriers don’t bother themselves with arbitrary weight limits. It should cost between $50 and $70 to ship your bag in each direction.

If you don’t have that luxury, or need to enter the airport with gear, consider these bags:

Patagonia Black Hole Wheeled Duffel Bag 120L – $349

This is the Death Star of all luggage. Take your other bags, add them together and you probably still won’t get to 120 liters. And this thing only weighs 8.5 pounds, thanks its construction of 15-oz 900-denier 100% polyester ripstop nylon. The wheels on this bag are indestructible, and they roll with the smooth cadence of graphite on on ball bearings, even if you’ve managed to jam this thing with 80 lb of whiskey bottles, ski boots, and Gore-Tex. Just be careful: it’s easy to blow past 50 lb just by packing one half of this bag. So cram it with the bulkiest, nuttiest stuff you’ve got. For instance, if you transport unwieldy equipment for smoking meat into the Rockies, then this is the bag for you. Or if you’re somebody who brings an alpine plus an AT setup, plus your kids ski kit, then you might want to think about hiring… The Black Hole Duffel.

September 29, 2016

How To Hire Better Engineers: Ignore School Degrees And Past Projects

Programmers in New York at a Google hackathon . (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan)

For most, the process of evaluating and hiring an engineer is something of an inexact art. Companies try to insert their own quantitative measures into the process, but they’re often misguided or not implemented with consistency. I know as I’ve been guilty of this myself.

Whether through luck or some thread of worthy evaluation, I have managed to hire talented and hardworking developers, but I’ve also made mistakes that, in hindsight, likely could have been prevented with a better process in place.

So what should that process look like? How do you properly evaluate an engineer’s readiness to contribute to your team and what you’re building?

It’s not easy. And it consumes time and energy; Sequoia Capital estimates that it takes the average startup 990 hours to hire 12 engineers.

Some founders find the exercise so difficult that they only hire people they know, at least to start. Max Levchin, the technical co-founder at PayPal and one of the most respected technical minds in Silicon Valley, built most of the early engineering team at PayPal out of his classmates at the University of Illinois.

Conducting technical interviews isn’t a straight-forward process. Many teams look for the wrong things, creating a bevy of false positives and false negatives, which leads to hiring candidates who won’t meet a company’s standards while also letting great candidates fall through the cracks.

But there are rules that companies and startups can incorporate to make their process more dependable. FundersClub did a deep dive on this with the help of Ammon Bartram, co-founder at Triplebyte, a Y Combinator company that evaluates engineers and recommends them for hiring at its client companies.

Triplebyte has been working on this problem for more than a year. It has five full-time interviewers who have now conducted more than 1,000 interviews with engineers as the company continues to hone its own regimented process.

The in-depth guide to interviewing engineers is here. For an overview, continue below.

September 8, 2016

International Startups Will Soon Draw More Venture Capital Than U.S. Ones

This picture taken on September 5, 2016 shows employees working inside the French IT company Linkbynet in Ho Chi Minh City. A decade ago app technology would likely have been developed in California’s Silicon Valley, but today those apps are being churned out by Vietnam’s startup sector — an industry driven by local techies trained overseas but returning home to prowl for opportunities. Credit: STR/AFP/Getty Images.

The United States has dominated the arena of technology startups since the beginning. There are a bevy of reasons for this, but chief among them is the venture capital infrastructure that has existed in the United States for decades. Across the rest of the world, venture capital simply didn’t exist as a major vehicle for investment.

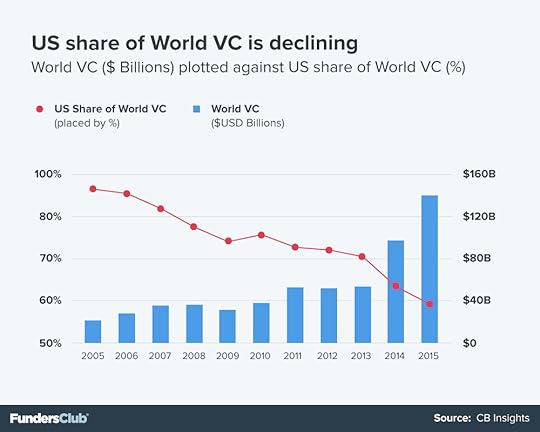

But that is changing quickly. Consider that in 2005, startups in the United States garnered 94% of the world’s deployed venture capital. Just a decade later, however, the U.S. share has decreased to 59%.

I did a deep examination of this topic at FundersClub, of venture capital trends and the cities and countries that now have the momentum, in a series of two pieces:

International Venture Capital Will Soon Pass That of The United States

International Cities with Venture Capital Momentum, and Emerging Hubs

We were surprised at how demonstrative the shift has been for international startups and VCs. That there had been a sharper growth internationally was apparent to anybody operating in the space, but the numbers make a case all by themselves.

The rest of the world is catching up to the U.S. startup and venture capital machine. Credit: Eli McNutt. Source: CBInsights.

August 11, 2016

Laughly, The Spotify Of Comedy, Gives Users Louis C.K. And Other Comedians On Demand

David Scott delivers his stand-up routine. Courtesy: Laughly

David Scott may be the perfect person to combine the on-demand capabilities of Spotify with the neglected listening genre of stand-up comedy. He’s an experienced founder who, after he sold his marketing technology company, Marketfish, in 2013, started writing his own comedy and landing stand-up gigs. At one point, he was performing two to three nights a week. He did more than 150 shows in all.

As Scott learned more about the comedy world, he realized how relatively difficult it was to for people listen to comedy via the web, despite its overall popularity. Pandora and Spotify both have some comedy content, but it’s never been a big focus for either company. On SiriusXM satellite radio, as many as 7 of its top 20 stations are ones that feature stand-up comedy. But satellite radio is largely limited to cars, and listeners can’t listen to particular tracks or comedians on-demand.

Gone are the days when people bought LPs and CDs of comedians’ work. In the early 1980s, Scott says, one out of five albums purchased was a comedy album.

“I realized that the distribution and consumption of comedy has changed greatly,” Scott says.

Scott saw an opening, and started serious work on Laughly early this year. The service, available via mobile app, launches today, with more than 20,000 tracks from 400 comedians available to people on-demand. Most of the biggest comedians are represented, including Kevin Hart, Louis C.K., Jim Gaffigan, Sarah Silverman, and Amy Schumer.

The model works like those of its musical peers. There’s a free platform that’s supported by advertising, and an ad-free version available for $4 per month. The revenue gets split 50/50 between Laughly and the comedy license holders. If a person listens only to one Jim Gaffigan album that month, then the license holder of that Gaffigan material would take home the entire $2. Otherwise, the money is split according to what was listened to by the user.

Subscribe Now: Forbes Entrepreneurs & Small Business Newsletters

All the trials and triumphs of building a business – delivered to your inbox.

Scott has funded the company himself up to this point, paying the bills for Laughly’s 11 employees, which include eight engineers and two people working full-time on licensing material.

Getting the rights to so many comedians so quickly hinged on landing perhaps the biggest holder of rights first—Comedy Central. Any comedian who has done a special with the cable station had that material licensed through the company. Comedy Central is owned by Viacom, whose executives saw potential in Laughly’s model. From there, other labels and comedians piled on.

Laughly also offers a conduit for comedians to self-publish their material as a way to make some money and to get their work noticed. Scott’s engineers are currently working on technology that transcribes every single joke on Laughly’s platform, so that the tracks can be catalogued by a matching algorithm. The idea is that, through machine learning, users in the future will be able to discover comedy through the app that’s similar to their current preferences.

July 26, 2016

For Startups, Raising Money Is Eight Times Easier In The Bay Area

Some startups find their beginnings organically, getting built slowly from years of effort. These kinds of companies can be anywhere, and they often are. Startups kindled with the intent of rapid iteration and quick growth, however, tend to be clustered in the kinds of places we expect: San Francisco-Oakland-San Jose, New York, Boston, etc.

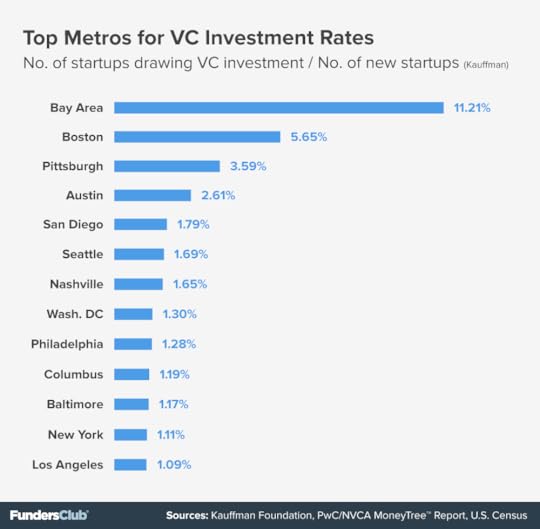

There exist many reasons for this, of course, but perhaps the top one is money. The Bay Area hosts the largest collection of venture capital wealth in the world. And while plenty of that money makes it out of the Bay, to places like Chicago, Austin and the East Coast, more of it stays local than anywhere else. Startups in the Bay Area, therefore, stand a better chance of raising some of this capital than if they were located elsewhere.

That’s not quite a declarative fact because there’s no way to conduct a truly scientific experiment with identical startups while only altering the location, but an examination of different datasets put out by FundersClub completes most of the picture, and offers some insight on the number of companies getting funded vs. the number of companies being started in a given city.

As part of a FundersClub examination of which U.S. cities are best for startups, FundersClub founders Alex Mittal, Boris Silver and myself tracked down three different datasets and combined them to express this ratio:

Number of startups in metro drawing venture capital investment in 1 year / Number of new startups in metro area during 1 year

Courtesy of Eli McNutt, FundersClub.

The results show that the Bay Area crushes all other places in this measurement, with a ratio of 11.21% of companies drawing VC investments to total number of new startups. The next closest metro was Boston, at 5.65%. The overall average among major metro areas in the United States was 1.4%, which puts the Bay Area at an 8:1 ratio compared with the rest of the company. The Bay Area and Boston skew the numbers quite a bit, so it’s also helpful to look at the median of 0.68% for U.S. metro areas. The Bay Area’s numbers are more than 16x the median.

An important note on this data is that while it’s certainly instructive, it does have some flaws. The total number of startups in a metro was derived from the Annual Kauffman Foundation Report, which lists something called Startup Density, which is the number of startup firms per 100,000 people. We get the the total number of startups in a metro by dividing the metro population by 100,000 and multiplying that number by Startup Density figure.

A startup, as defined by Kauffman, is a company that is less than one year old and has at least one additional employee to the founder/owner. The problem with this measurement is that it will include companies that aren’t tech startups or are the kind of company that can never draw a venture capital investment, like a carpentry shop. But it’s still a useful measurement that gives us the best data available on the number of startups in a given metro area.

Even with the caveats, it’s clear that companies in the Bay Area draw investments at a much higher rate than anywhere else in the United States. But companies will pay for that access to capital, as it’s far more expensive to run a company from the Bay Area.

June 13, 2016

Every City Wants To Be A Tech City

The First In An Ongoing Series: Every City Wants To be A Tech City

Aside from the general machinations with which every city must deal—schools, utilities, crime, etc.—the single effort, the single desire that seems to unite modern cities is the idea that local prosperity and economic invigoration can be realized through nurturing a movement that lures and retains tech companies, engineers and founders. The idea, of course, is that this will lead the way to more tech jobs, more local economic productivity, and more brains flowing into the metro, with the chance that the next Facebook or Microsoft takes root. No city, save the Bay Area, feels totally secure with its tech credentials. Tech-minded civic leaders are constantly searching for ways their city can continue to work at building out tech, and climb the ladder of significant tech metro areas.

This trend seemed to hit high gear about five years ago, as the economy climbed out of the Great Recession and people saw that the tech sector powered through the down period with minimal damage, evening managing to grow on many fronts. The leading edge of tech, startups and venture capital, fared well, as some of the transformational companies of this current era—Airbnb, Uber, Dropbox—found their footing during this otherwise dismal economic period. It only made sense, then, that all cities would want what San Francisco and Silicon Valley already had in spades. The movement, then, was fully afoot.

St. Louis and Kansas City have been grinding at tech for nearly 20 years. (Photo credit: KAREN BLEIER/AFP/Getty Images)

But fostering a vibrant tech scene is hard, and it’s not a science. The handbooks, as they exist, are vague and unproven. Startup tech ecosystems require three things to prosper: founders, preferably technical ones; money, preferably experienced venture capital; and engineering talent, preferably a deep pool with lots of experience in the latest web and mobile frameworks. The other ingredient, however, is less definable. Cities need to start with something. And more often than not, the cities that have seen some success with tech owe something to the flag bearers who have been grinding away at the cause for years, long before tech was pinned high on the agenda of every major city mayor and politician.

Subscribe Now: Forbes Entrepreneurs & Small Business Newsletters

All the trials and triumphs of building a business – delivered to your inbox.

St. Louis and Kansas City have never been known as major centers of startup and tech activity. But that perception has begun to turn. St. Louis was recently named one of the best cities for startups in America by Popular Mechanics, which cited the fact that eight makerspaces and accelerators opened here between 2011 and 2013. Business Insider ranked both St. Louis and Kansas City in the top 10 for startup deal growth during 2015 . But before all of this relative success, a forum called InvestMidwest had been buttressing the tech scenes in both cities since 2000.

InvestMidwest has been at this for 17 years, knocking on doors and urging capital and entrepreneurs to get together once a year at its event that alternates between St. Louis and Kansas City. When the tech bubble exploded in 2001 and many other tech events and movements ceased operating, InvestMidwest soldiered on. Part of that longevity comes from the simple fact that the tech scene in this heart of the Midwest never experienced the kinds of highs that existed on the West Coast. The crash wasn’t much of a crash, points out Nathan Kurtz, senior program officer at the Kauffman Foundation, a non-profit that has sponsored InvestMidwest since its inception.

There exist pilot lights of the startup movement all over the country that, like InvestMidwest, kept the movement leaning forward when others weren’t so sanguine about the future. In Chicago, undefinedTech Cocktail and its gatherings formed a base of activity before things truly took off. In Pittsburgh, which has seen tech ramp up during the last three years, Innovation Works has invested in local companies since 1999, keeping a valuable base of founders and engineers in the metro. In Minneapolis, the Minnesota Interactive Marketing Association has been pushing digital marketing since 1998, long before it was the giant industry it is today.

InvestMidwest, as an annual gathering of startup entrepreneurs and capital with focused tracks where startups can present their businesses, and experienced hands can explain the latest innovations in a space, came at just the right cadence back in 2001. It happened often enough to keep connections alive, but not something that was overburdensome during a time when tech was thought by some to have been a fading trend. InvestMidwest, and other events like it across the country, kept the coals of entrepreneurship and investment stoked just enough to allow for the tech expansion that cities like St. Louis and Kansas City enjoy today. By putting together all the ingredients—capital, founders, and new trends in tech—for two days, participants get enough time to make lasting connections and kindle the beginnings of relationships that can lead to company building.

May 27, 2016

Timing A Tech IPO Is Far More Complicated Than It Used To Be

FILE -A digital display board on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. (AP Photo/Henny Ray Abrams, File)

Word of Twilio’s planned IPO has mitigated some of the handwringing about the current class of so-called unicorns—companies that have topped $1 billion valuations—that have managed to persevere as private companies, squirreling away venture cash with rounds at ever-higher valuations. Twilio’s offering makes sense. The stock market has been climbing for three months, eradicating losses, and there has been some success with other recent IPOs, albeit not all of them in tech.

The roll of the stock market, and whether it’s been on a prolonged run or dive, still drives more of the IPO action than anything else. But it’s also true that companies have more levers at their disposal now to bring in cash and stay private longer. Coupling these two realities: that the stock market’s performance drives companies to list—and that there now exist so many attractive options for late-stage funding and forms of limited liquidity outside of an IPO—has created a world where the Ubers, the Airbnbs and the Palantirs just hang in and eschew picking their stock symbol.

Subscribe Now: Forbes Entrepreneurs & Small Business Newsletters

All the trials and triumphs of building a business – delivered to your inbox.

Just looking at the first part of the equation, the price of the market vs. IPO volume, yields a rather straight-forward relationship. I did a deep dive on this exact thing with FundersClub CEO Alex Mittal, where we weighed all of the factors playing into the companies’ current IPO considerations. Using data from CB Insights, we graphed the relationship between the S&P 500 and the number of tech IPOs in a given year. The tight binds of the relationship became quite apparent when viewed in a chart.

Tech IPOs vs. Performance of S&P 500. Courtesy: FundersClub, Eli McNutt

The biggest thing that founders have to keep in mind when deciding if, when and how to IPO: the preservation of pacts made with investors and employees. A company that finds success and creates large amounts of equity has to find routes to liquidity for its shareholders within a reasonable envelope of time. Failure to do this can cause unrest amongst employees, leading to unnecessary churn amongst the ranks, a factor that can greatly weaken companies, even those with the strongest products.

Fifteen to twenty years ago, the number of routes to liquidity were fewer. Getting a company to the IPO window was the default method of satisfying employees and investors, so founders were more apt to rush out and get offerings done when the time appeared right. Now, however, companies can lure large blocks of funding—$1 billion plus—from the private market, which was a far more difficult, if not impossible, task 15 years ago. Such amounts of willing and available private capital—at big valuations—allows companies to hyper-optimize the point at which they IPO. Some might argue that’s bad—as does Bill Gurley—and some might say it’s merely another distraction for CEOs who should be focusing on other things.

Investors demand IPOs because it’s through these vehicles that they can officially book winnings and add a trophy to the case in the foyer. Entrepreneurs may be focused on other things, however, and don’t consider an IPO the end of anything, but merely one step on a longer journey. So a divide in opinions on when an IPO should happen can always exist.

[dam_gallery]

It just so happens that now, at this moment, the size and availability of private financing options is at a peak in modern history, which, along with battered market during the latter stages of last year, has led to a dearth of tech IPO action.

Christopher Steiner is a Y Combinator alumnus and the New York Times Bestselling Author of Automate This, How Algorithms Came To Rule Our World. He’s on Twitter.

May 5, 2016

Do You Fit In With Company Culture? A New Algorithm Knows.

Society has come to accept algorithms as arbiters of love. Millions of marriages each year owe their genesis to the matching smarts of back-end code belonging to a dating app. Algorithms, in this way, have fundamentally changed how we find a mate, arguably the most important decision of our lives. If we’re willing to entrust algorithms with this essential task, then it only makes sense that algorithms and bots will continue leaking into our lives’ other seminal processes.

I wrote a book, Automate This, on how algorithms, AI and the like are taking over the world. But I wrote that before eHarmony brought its experience in relationship matching and applied it to the workplace. EHarmony wants to help companies and workers avoid mistmatches of personality and culture, decreasing what it calls “regrettable churn” in the workplace while aiming to double the average time an employee spends at a company. Lofty goals.

The intuitive view on this is that eHarmony is simply applying its relationship matching algorithms to a similar problem. But the riddle in this case, matching people to companies, is more complicated. EHarmony’s new product, Elevated Careers, which it is rolling out as a beta enterprise solution for some trial clients, has to search out worthwhile matches in an environment of one-to-many, where the one is the prospective employee and the many is some kind of representation of the company or team. Pairing people romantically, on the other hand, is a one-to-one match, a simpler comparison model that can be optimized and honed more easily.

The legacy dating solution also incorporates the powerful and immediate feedback of humans. Two people are unlikely to press forward with a serious relationship if they aren’t utterly compelled by its prospects. The feedback from job interviews and a feeling of true fit, for both employee and company, can be far more ambiguous, as anybody who has gone through a hiring process—from either side—knows well.

Steve Carter and Dan Erickson are behind eHarmony’s new foray into the workspace.

For eHarmony, solving the biggest part of the problem means forming some kind of profile of a company’s makeup and culture. As anybody who is well-read in business books and MBA fodder knows, company culture has been a favorite flavor within the business press for a number of years—and startups often stress its creation and maintenance from day one. But, as Dan Erickson, the general manager of Elevated Careers points out, there can exist a disconnect between what executives perceive or desire their company’s culture to be and what it actually is. “We are not allowing the HR dept or the C-suite to just say what the culture is—we’re using current employees to get a real reading,” Erickson says.

To determine a company’s true culture, eHarmony administers personality tests to a wide swath of current employees. The results, on a singular level, are anonymized, as it’s the aggregate data that tell the story in this case. With this holistic company profile in hand, eHarmony’s algorithms can get to work finding fits between applicants and a company’s existing culture.

The platform went live to job seekers and hiring companies in April. EHarmony partnered with SimplyHired to backfill its database with several million jobs. It doesn’t have extensive personality profiles of any of the listing companies, of course, because companies haven’t yet had the chance to participate in the personality testing for employees. The first company to go onto that platorm will be AT&T, which is having its employees at retail stores around the Bay Area participate. Once a solid personality and culture profile has been determined for each store by the eHarmony algorithm, AT&T will be able to try to hire new employees based on that data. The idea, of course, is to fit the right people to the right stores.

April 13, 2016

A South Carolina Startup That Hacked The Industrial Process To Reach $100 Million In Revenue

Rob Honeycutt’s success defies so many conventions within the entrepreneurial canon that it’s hard to pick which part of his tale merits telling first. As a salesman, he’s not supposed to be good with software. As somebody without a college degree, he’s not supposed to be able to, in a little over a decade, start and scale up a complicated set of businesses all under one holding company. As a company based in South Carolina, Honeycutt’s firm isn’t supposed to be able to recruit globally and draw engineering talent to what is, for tech, something of a desert, although it’s improving.

But Honeycutt has done all of that as the CEO of a nimble and growing manufacturing empire enabled by proprietary software that allows his salespeople to function as in-field engineers. Honeycutt’s holding company, SixAxis, in Andrews, S.C., includes ten companies that mostly involve the design, manufacture and distribution of industrial safety steps, platforms and cages. SixAxis also includes a full-on marketing agency, Red 7, that employs 20, and a 60-engineer software shop, Atlatl, that may hold the largest potential of any of the companies.

Subscribe Now: Forbes Entrepreneurs & Small Business Newsletters

All the trials and triumphs of building a business – delivered to your inbox.

Rob Honeycutt shows off his new product to Joseph P. Riley, right, the mayor of Charleston, SC.

Honeycutt, 44, had no thoughts of holding companies, computer code or digital marketing in 2001, when he quit his job after his employer made deep cuts in its sales budget and commissions. He had been selling metal safety fences that mounted to catwalks and platforms placed in factories and other industrial settings. He had no fallback plan.

“I could go start my own company or I could sell used cars,” he explains. “I didn’t have an education that could take me into different kinds of businesses and disciplines.”

So Honeycutt and another salesman who left at the same time, Fred Harmon, decided to keep selling the same kinds of equipment as did their former company. They put together a catalogue of product—none of which yet existed—and took it on the road. They figured when they got enough orders, they’d find out how to get the stuff built. Early on, there was little need to worry about manufacturing.

Today, Harmon and Honeycutt each own 50% of SixAxis, which doesn’t report revenues, but, based on my own estimates that aren’t disputed by Honeycutt, has an estimated $100 million in revenue. What we know: six years ago, SixAxis did $25.1 million in sales, and has enjoyed “double-digit growth” since. People with knowledge of the company estimate that growth rate to be near 25%, which, compounded, would put the company near $100 million in sales.

In the first year of the business, however, the founders were far away from even $100,000 in sales, as the men managed to sell only $20,000 worth of product their first year. For that, they found a contract fabricator to fashion what they needed.

The second year, however, brought more sales—just under $1 million—and the realization that contracting out the manufacturing on an ad hoc basis wasn’t a good solution. The welds were sloppy and the equipment, though it worked, wasn’t good enough to sell in bigger quantities. So Honeycutt leased the cheapest manufacturing building he could find—it had a dirt floor—and slowly started hiring tradesmen to weld, cut and bend steel into the products he sold.

March 31, 2016

Right Now Might Be The Best Time For VCs To Invest In Startups

The market for startup investing travels a curve that, at its peaks, triggers big valuations and relatively easy money for early-stage companies. We saw the height of this curve during the tech boom in 2000, during the early part of 2008, and again during the first three quarters of 2015. At the curve’s lows, in 2001, 2009 and, perhaps now, money can dry up. During these times even growing companies with great teams and the promise of paradigm disruption can find raising a Series A to be difficult.

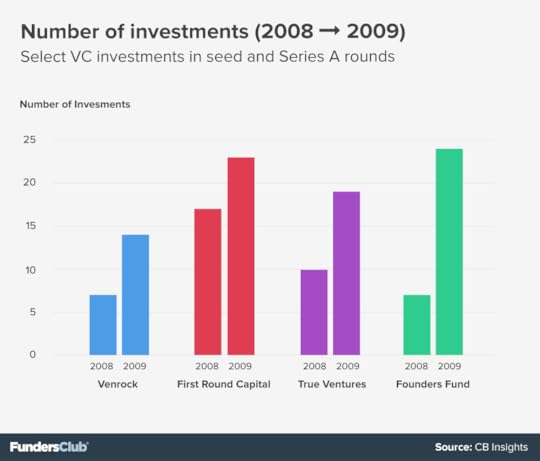

But it’s at this low period that startup investors should consider piling into the startup market. Many of the brightest young tech companies have found their footing and funding during these market slowdowns, when conditions force companies to operate leanly without the expectation of a plump venture capital check. FundersClub CEO Alex Mittal and I recently examined the relationship between market cycles and early stage venture capital investing.

Venture capital is not a new industry, but it’s young enough that in its current form, we’ve only been able to observe its machinations and the resulting trends through three demonstrative slow downs. Alex and I found, however, that some of the most successful investors of the last decade maintained their investment pace during the last slowdown. Those investors who stayed the course while others fled, have been rewarded. Airbnb, Twilio, Uber, Slack, Pinterest and Dropbox are among the headliners of a class of companies who drew early-stage funding during the last slow down.

Even as the rest of the market pulled back sharply—the total dollars in seed and A rounds decreased 36% from 2008 to 2009, according to CB Insights—First Round Capital, for one, increased its rate of investment in 2009. The VC firm went from $23 million in 17 investments in 2008 to $65 million in 23 investments in 2009. It was during this extended down period that First Round funded Uber’s seed round and Square’s Series A. We tracked down more examples, investment risks and rewards, such as emerging technology platforms, in the larger piece at FundersClub.

Graphic, Eli McNutt. Data, CB Insights. Courtesy of FundersClub.

Even with this experience, First Round recently told its startups and LPs that it expects the current slowdown to settle in for some time, referring to it as the “old normal.”

But which part of the curve should be considered normal? The lengthy periods of high valuations and big VC checks, or the sown periods? When I was exiting Y Combinator with my cofounder at Aisle50 in 2011, we were witnessing the start of a bull run in venture capital that would last four years. We received multiple term sheets for our Series Seed fundraising and we were able to work with an amazing set of investors at August Capital. Our Series A experience was similar, and we were lucky enough to work with the team at Origin Ventures in Chicago. Experts warned that the end was at hand many times during our funding cycles, but they weren’t right until the end of 2015.

It’s hard to state things declaratively about the present situation in venture capital, as we don’t have the trailing stats and data that make the examination of past periods more quantitative. But there does seem to be a relationship between pullbacks and the creation and funding of elite companies, something that investors such as First Round, Founders Fund and even Sequoia Capital seem to have internalized.

Christopher Steiner was cofounder and co-CEO of Aisle50, which was acquired by Groupon in February 2015. He’s a New York Times bestselling author of two books, including Automate This, How Algorithms Came to Rule Our World. He’s on Twitter.

Christopher Steiner's Blog

- Christopher Steiner's profile

- 21 followers