Christopher Steiner's Blog, page 6

September 6, 2013

Cofounder Of Square Thinks Finance Is Ripe For More Disruption

Jim McKelvey, who co-founded mobile payment company Square, is making a large bet that more innovation is around the corner in finance—and he doesn’t mean “innovation” like Goldman Sachs means “innovation” (no quad-armed collateralized muni-bond interest rate swaps, please). McKelvey’s new accelerator, SixThirty, will launch this fall with its first class (applications due today) of four financial technology startups. St. Louis will be home to SixThirty, which also serves McKelvey’s interest in giving his hometown a boost in tech.

Startups will be given $100,000, which will comprise an equity investment in the company belonging to SixThirty. Most of these stakes will range from 5% to 10% and will be negotiated on an individual basis. The St. Louis Regional Chamber, keen on getting more young engineers and entrepreneurs to St. Louis, is supplying the cash. The hope is that some of the financial biggies in town—Edward Jones, Stifel Bank and Scottrade, among others—provide some exits for startups that hit upon effective products. Silicon Valley companies will be watching, especially Google, which is always searching for new features for its payment platform, Google Wallet.

Startups will be given $100,000, which will comprise an equity investment in the company belonging to SixThirty. Most of these stakes will range from 5% to 10% and will be negotiated on an individual basis. The St. Louis Regional Chamber, keen on getting more young engineers and entrepreneurs to St. Louis, is supplying the cash. The hope is that some of the financial biggies in town—Edward Jones, Stifel Bank and Scottrade, among others—provide some exits for startups that hit upon effective products. Silicon Valley companies will be watching, especially Google, which is always searching for new features for its payment platform, Google Wallet.

Many people, myself included, always always cringe when we hear finance and innovation linked together—as it’s usually to some unholy end. I caught up with McKelvey and asked him about that as well as some other aspects of SixThirty and life as an entrepreneur. The good news, it seems, is that the next financial apocalypse won’t be coming from St. Louis:

Q: Innovation within finance means different things to different people. Wall Street for instance, claimed CDOs were innovations, and it takes the same stance regarding a lot of the sophisticated derivatives that have been created in recent years. What kinds of “innovation” do you want to see out of SixThirty?

McKelvey: I love simplicity and transparency. The big problem with CDOs was that they were so complicated that people misunderstood what they were buying. One of the things technology does well is to simplify complex systems, examples range from intuitive graphs of byzantine datasets to Artificial Intelligence detecting fraudulent behavior. If SixThirty helps companies bring more understanding and fairness to the world of money, that would be great for everyone.

Q: Wall Street and the financial sector have taken their shares of elite engineers from the job pool, especially in places such as New York and Chicago where prop trading shops and quant funds tend to be headquartered. Silicon Valley has traditionally viewed these hiring trends as corrosive to the tech sector and the economy in general—the thinking being that these companies aren’t actually building anything. What’s your view on that and how will the companies reared at SixThirty be different?

McKelvey: Zero-sum games are not much fun to play for years on end. Giant paychecks are great, but people like seeing the positive results of their work over time. The people I know who build homes are happier than those who sell homes, and so it is with engineers. I encourage the companies at SixThirty to solve real problems for ordinary people, there is a massive opportunity there and the work is extremely satisfying.

Q: Will SixThirty actively search for solutions to crack the quasi-opoly held by Visa, MasterCard and Amex on payment networks? Square democratized access to these networks, but they still remain quite expensive at an average 3% fee per transaction. It seems to be one of the ripest items yet to be disrupted yet.

McKelvey: No, we are not targeting any particular vertical within the financial sector. Payment network fees may be above international norms, but I can think of a dozen more commonplace abuses. Just look at the fees banks charge for basic accounts or go try to refinance a car loan.

Q: What kind of companies that have launched in last five years would have been ideal fits for SixThirty?

McKelvey: Square would have been a great candidate, we may have been able to launch a year sooner if we had had the sort of connections that SixThirty provides. I think Kabbage would have also been a great company. In general, any startup with big ambitions in the financial sector is going to need partnerships with major firms.

Q: Are you worried about companies leaving St. Louis at the completion of the program?

McKelvey: We are not requiring any of the firms to stay in St. Louis, so some will choose to leave and that’s fine. Companies should locate where they have the best chance to thrive. That said, any startup partnering with St. Louis firms would have a strong incentive to stay.

Q: Why is something like this needed and what does company from say, Scotland or the Middle East, get from participating in SixThirty ?

McKelvey: Fintech startups are unlike other tech companies because they need access to the financial world. Banks, money transmitter licenses, ACH access, insurance, capital reserves – the list goes on. St. Louis has the largest concentration of financial companies beside New York. And since access to that ecosystem is easier in St. Louis, we thought SixThirty could be the onramp.

Q: There are accelerators all over. Why it is in the interests of these startups to come to St. Louis?

McKelvey: The key is really the easy access to the big companies. St. Louis has a unique ecosystem in that it’s a big city that functions like a small town.

Q: Tell me a bit more about LaunchCode which pairs inexperienced coders with expert developers at local companies.

McKelvey: It’s a pretty simple concept. Take two coders with two keyboards working together on one monitor. It’s much faster and flexible than the typical higher education model and has been proven to work and increase productivity at Square and other tech companies in Silicon Valley.

Q: One questions about Square — how can Square be better positioned in terms of spreading to the broader market?

McKelvey: Square began with a solution for the smallest merchants. Gradually, our products have become more popular with larger sellers. We see this trend with most new technologies, even the Internet itself. The early adopters are always on the fringes and then adoption moves into the mainstream. It’s not a question of position, it’s a question of evolution.

Christopher Steiner is the cofounder of Aisle50, which came out of Y Combinator, an accelerator in Silicon Valley. Follow him on Twitter.

July 31, 2013

The Facebook of Sports? Yes, Actually

Part of Yahoo’s success in the late 1990s and early 2000s came from its breadth and its ability to fill product voids with its engineering team. Yahoo parlayed its status as a hub destination on the web into market-leading positions in search, email, news, fantasy sports, instant messaging, personal websites and even classified ads. But as websites specializing in each of these domains gained momentum, Yahoo’s offerings fell behind. Its polyglot approach faltered.

Some have predicted the same kind of fate for Facebook, arguing that social media sites built for niches, from politics to parental topics, will nip one audience off at a time, draining Facebook of its might and its serve-all, be-all status. Hundreds of startups have taken this logic and built on it, but few have built anything people care about or visit frequently. One exception is Lockerdome, which set off to become the Facebook of sports. After tweaking its model for more than two years—a lesson in persistence for any startup—the St. Louis Company has found ways to make this approach work.

Gabe Lozano, the founder and CEO, likes to say that “Facebook is for who you know and Lockerdome is for who you like.”

After lots of tweaks and a tech renaissance in his home city, Lozano has found traction.

Friends and family, Lozano explains, enter our lives for different reasons and at different times. Facebook, he says, isn’t the best place to discuss one’s love of the Chicago Blackhawks or of, say, Mies Van der Rohe-designed buildings. Although it’s true that both the Blackhawks and even Mies might have dedicated fan pages on Facebook, the depth and quality of interaction here, Lozano argues, is limited.

Lockerdome leverages content such as quizzes, contests and open discussions on pages dedicated to one topic to drive traffic and visits from people its clients are trying to reach. Lockerdome now has 1,700 of what it calls publishers—who regularly push out content to their dedicated pages at Lockerdome.com. The approach is catching the eye of major sports teams, as the St. Louis Blues became the first big franchise to put up a dedicated page for their fans on Lockerdome.

Lozano’s approach has also caught on with investors. Lockerdome has raised $8 million from a bevy of venture capitalists and had offers to double the investment of its last round, which Lozano eventually limited to $6 million.

The money helps Lockerdome expand on a product that’s designed to help brands like the Blues reach its most ardent fans—and help that group all meet each other. “How do I take Chris and turn him into 10 people like Chris,” Lozano says.

Lozano is finding more than a few Chrises: Lockerdome’s traffic has topped 12 million unique visitors a month with a growth chart—hockey-stick style—that any startup would envy.

It wasn’t long ago, though, that Lockerdome had few visitors, no money and no fans who cared. “Not even my mom would sign up for an account,” remembers Lozano.

Lockerdome’s first model allowed small sports teams—like local baseball clubs—to license a generic, editable Lockerdome platform to be the team’s website for $99 a month. “For two years, all we did was knock on doors for 99 bucks,” Lozano says.

But in early 2012, Lockerdome made a small strategy tack that would eventually set it up for far larger successes: drop the fee altogether and go after big fish—like major sports teams, brands and star players.

Ray Lewis has his own network on Lockerdome.

The new approach didn’t bring instant returns. The turning point, though, came when the social media manager for Troy Polamalu, safety for the Pittsburgh Steelersand star of Head & Shoulders Shampoo commericials, heard about Lockerdome. Polamalu wanted to run a weekly contest for different prizes—jerseys, footballs, dandruff-fighting shampoo—each week. After that promotion launched, other sports notables began taking note.

Paul Jonff, who handles digital media at Rawlings, the St. Louis company that supplies every Major League Baseball team with balls and helmets, as well as 52% of majors players’ fielding mitts, heard about Lockerdome from a friend and was intrigued.

“St. Louis is a relatively small big town, so you’re going to eventually run into any other group that’s in involved in sports,” Jonff says.

Rawlings spun up a campaign with Lockerdome that consisted of a contest that would run the entire baseball season. Contests like quizzes comprise some of Lockerdome’s most popular widgets. Clients can easily drop the widget code into a landing page on the web or Facebook and drive engagement with fans. Rawlings is getting more than 5,000 entries per day.

“It keeps people involved and coming back to our Website,” Jonff says.

That many of Lockerdome’s biggest advocates sprout from its hometown of St. Louis isn’t surprising. There has been a collective pull within this Mississippi River Metro to hang its economic identity on tech as it searches for a way to bring life and jobs to an inner city fighting the second highest violent crime rate of any big city in America.

As Lockerdome grew, Lozano was often frustrated by the lack of a tech scene within his city. Leaving St. Louis almost seemed inevitable.

“As of just a couple years ago, the tech startup scene here was dead,” says Lozano. “It was better to tell people that you were unemployed than to say you were a tech entrepreneur, as it as least implied the desire to have a real job.”

But the last 18 months, because of Lockerdome and a coterie of others, has brought real progress to St. Louis. People are noticing.

The difference, says Lozano, is startling. “You can walk into almost any downtown coffee shop and you’ll run into fellow entrepreneurs working on and pitching their startups. We just hosted an all-night hackathon called Code Until Dawn and more than 30 people from the local tech community showed up.”

With 23 employees, a just-opened New York sales office and a cadre of investors interested in getting any available equity, Lozano isn’t changing the formula now.

May 20, 2013

The Most Undervalued Brand In The World

Most companies take their best asset and wring it for every drop of sales possible. Some take it too far, in fact, and end up diluting the very brand that built their empire. The venerable Hershey Company, maker of its eponymous chocolate and other keystone treats, has been doing the opposite, however. It’s been shielding from the world its best asset, a mightily delicious, addicting candy bar that doesn’t get its fair due from its parent company.

The Take 5 has been limited by little marketing support, a bad name and banal packaging

Let us introduce to you the ill-named, mis-marketed and diminutive masterpiece known, regretfully, as the Take 5 Bar. Oh, you’ve never heard of the Take 5? Join the club that, sadly, numbers in the billions. What kind of world do we live in that finding the prosaic and tasteless Necco Wafers at an average convenience store is far more predictable and easy than finding an exquisitely delicious Take 5 bar?

It’s sad. It’s sad for the world. And it’s especially sad for Hershey and its shareholders because the Take 5 can be and should be Hershey’s iPhone. Hershey’s stock has been an outperformer and we’re proud of the candy maker for that—but we think it can be an even bigger star.

And we know what you’re thinking: these are the words of a huckster, a pumper and dumper, somebody looking to get a big rise out of the markets tomorrow with talk of this magical candy bar. But we did our homework here. We called the heavyweights in on this. We even called Hershey.

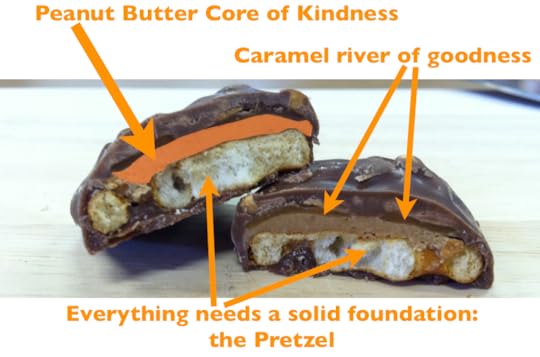

First, let’s examine what comprises candy greatness. Like many tech companies that strike upon innovation by fusing the power of data and the web with social connectivity or ecommerce, the greatness of the Take 5 stems from a fusion of salty and sweet. The pang of saltiness comes from the sturdy foundation of a pretzel topped with a dollop of peanut butter and peanuts. From there Hershey took a leap by daring to layer caramel atop the peanut butter. And just like Jonas Salk or Gottfried Leibniz, Hershey didn’t stop at “great enough.” It brought the thunder, adding a layer of its milk chocolate—not too thick, not too thin—around the entire works.

The composition of pure genius can be seen in profile view in the schematic picture on this page. As seen here, the Take 5 bar has several masses emitting their own centers of gravity, all of them coalescing to put eaters in an orbit of happiness never before achieved by a mass-produced candy bar.

The Take 5 is a sophisticated and nuanced beast

So why doesn’t Hershey’s push this thing? Why has the Take 5 been doomed to groveling behind brands like York Peppermint Pattie and Mounds? Don’t bother going to the website for the Take 5—it doesn’t have one. Hershey’s did build a website dedicated to its so-called “Iconic Brands.” Almond Joy, apparently, is iconic. Twizzlers, iconic. Kit Kat, iconic. But the one bar that should rule them all? Not iconic, says Hershey.

This is like watching The Beatles be the first of three opening bands for Nickelback. Anybody with half an eye for talent wouldn’t let the Take 5 ride the bench while Mr. Goodbar remained in the starting lineup.

So we brought the question right to Hershey: why bury a star?

“We agree that Take 5 candy bar is a fantastic product,” said Jeff Beckman, head of communications at Hershey. “However, as a company that is building a large portfolio of more than 80 brands around the world, we have to make decision as to which brands receive marketing support.”

In other words, Take 5 doesn’t get marketing support. Hershey says that it uses a “wide range of proprietary research tools and marketplace insights to understand which products best meet the evolving demands of customers.” Hershey calls its supported brands “activated.”

One of Hershey’s products that recently gained “activated” status is Rolo, which is now drawing a significant amount of advertising support for the first time since 1987—more than 25 years ago.

So here’s a brand in Rolo that is essentially a commodity—caramel covered in chocolate—stuck with a name and packaging from when Ronald Regan was president, and it’s being supported in a big way by Hershey while Take 5 lurks in the shadows, a sleeping giant.

“Many organizations fail to effectively put themselves in the minds of their customers and it would seem Hershey has drastically undervalued the reality that Take 5 bars are delicious, nutritious, sumptuous and scrumptious,” says Aaron Perlut, founding partner of digital marketing and PR firm Elasticity, who has carried out campaigns for Miller Lite, H&R Block, UPS and Papa Johns.

Even without support, Take 5 has grown on the backs of grass roots volunteers. It’s now an $11 million brand, according to Nielsen research, having grown 10% in the last 12 months. Not bad for a brand with zero marketing. Even better for Hershey: Take 5 indexes highly with households making more than $100,000—its distribution here is 89% higher than with households making less than $100,000.

“Putting it all together, Take 5 is a brand with a lot of potential—especially in more urban and affluent areas,” says Dr. Vanitha Swaminathan, a professor of marketing at the University of Pittsburgh who has cooperated on several research projects with Hershey.

Swaminathan believes that the Take 5 could benefit from social media campaign waged on the Web to reach bloggers and foodies who haven’t yet tried it. Before hearing about it from a reporter, Swaminathan had never tried the candy herself. But now she’s a big believer.

“It’s quite amazing—all of those flavors come together and really explode in your mouth,” Swaminathan says.

To be fair to Hershey, we think we know what it’s guarding against by keeping its best asset muffled beneath feeble marketing. It’s afraid. All companies, of course, are tempted to extend their best franchise into new arenas and new customer pools. This can work: Patagonia’s pricey outerwear was once the sole province of mountain folk and hippies, but it now occupies space in 50% of Manhattan closets.

February 28, 2013

Groupon’s Andrew Mason Did What Great Founders Do

When I met Andrew Mason in 2007, Groupon didn’t exist. Mason was driving a startup called ThePoint that gathered people on the Web to unite behind particular causes. He had cleverly created a stir by soliciting pledges from normal people to build a dome over the entire city of Chicago that would be deployed during the cold months of winter. Mason bubbled with confidence; he would need it.

When I met Andrew Mason in 2007, Groupon didn’t exist. Mason was driving a startup called ThePoint that gathered people on the Web to unite behind particular causes. He had cleverly created a stir by soliciting pledges from normal people to build a dome over the entire city of Chicago that would be deployed during the cold months of winter. Mason bubbled with confidence; he would need it.

Mason has been pelted with disapproval from the tech world ever since Groupon turned down a $6 billlion acquisition offer from Google during the fall of 2010. Some of that was jealousy, some of it came from true incredulous disbelief that a company so young could spurn such an offer, and some of it came from the Silicon Valley set that saw Groupon as a company that had done nothing innovative with its Webapp and whose business didn’t scale on the back of code, but on the backs of sales people (not the preferred method of growth in the Valley). When Groupon went public in 2011, Mason drew yet more sets of critical eyes, now in the form of Wall Street analysts and the journalists they run with.

But what nobody talked about was the fact that Mason took Groupon from a tiny startup to a billion-dollar web business in less than two years—and then, when the company seemed most vulnerable, he helped it stamp out competition and build the most valuable email list in the world.

It may have been time for a change at Groupon. But Mason did what great founders do: he innovated and he built.

Mason had already exhibited the innovative nose of a great founder when he struck up the original Groupon model—a method that doesn’t get its fair due as a marketing tool. Before Groupon came along, there was nothing that brought such power to small, local businesses. It may not work for everyone, but judging by some of the repeat business I witness in my own neighborhood, it works quite well for a wide swath of different companies. In addition to innovating, Mason did some of his best work in building Groupon and strengthening its platform in the two years after he and the Groupon board turned down Google.

One of the common barbs people threw at Groupon, especially in Silicon Valley, was that its business offered no natural barriers of entry. All a person needed, the detractors shrilled, was a website and a telephone. At one point, there were 500 Groupon copycats, serving up the same kind of deals in the same kind of format, in the United States. Almost all of those are gone now.

Living Social, once thought to be the favored challenger, has sailed into even rougher waters lately, a recent $100 million investment allowing it to keep on. Groupon, though, continues to grow. Its email list, built originally to connect people with local deals, now serves as an efficient conduit to sell anything and everything—as evinced by the rapid growth of Groupon Goods.

Mason left Groupon with the most powerful email marketing engine in the world, a growing income statement and a balance sheet with $1.2 billion in cash. The music major from Northwestern has been sprinting since 2007; now is probably a good time to rest.

Going back to when I met Mason in 2007, his original venture, ThePoint, didn’t turn the corner as a revenue-generator. But in the summer of 2010 when I walked over to Groupon for an afternoon chat with Mason, what I saw astounded me. Six hundred people hammering keyboards in front of big screens spread out across an old warehouse in Chicago’s River North neighborhood. I knew Groupon was doing a nice job – but I hadn’t known its scale.

Andrew that day confided to me that Groupon was on pace to break a $1 billion revenue run rate by the end of the year. No publication, I knew, had been able to put a finger on Groupon’s revenue. Nobody knew it was this big. I called my editors in New York and laid out an idea for a story. Two weeks later, Andrew Mason posed on the cover of Forbes magazine, with the proclamation: “The Next Web Phenom.”

We weren’t wrong. Andrew Mason was the Web’s next phenom.

Christopher Steiner is the Author of Automate This, How Algorithms Came to Take Over Our World.

Follow Christopher on Twitter.

More On Forbes:

see photosDavid Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty Imag

see photosDavid Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty ImagClick for full photo gallery: Tech Wreck: The Fall Of Social Web Billionaires

February 22, 2013

The Top 5 New Gear Pieces for This Winter

Each year, we’re asked to throw aside our carefully assembled wares, trinkets and garb for the outdoors in favor of newer models that will make us drier, faster and braver. The industry of adventure gear is built on its ability to coerce you into buying something that, at best, is incrementally better than whatever might be in your closet at that moment.

The strategy works. It’s rare that you see a recreational skier, even one that may get on the snow only two or three times a year, sporting a Gore-Tex parka so threadbare that it requires replacement, lest the user get wet.

The strategy works. It’s rare that you see a recreational skier, even one that may get on the snow only two or three times a year, sporting a Gore-Tex parka so threadbare that it requires replacement, lest the user get wet.

We buy new gear because new gear, we hope, will imbue our own outdoor games with a sense of freshness, a renewed vigor or, quite simply, the look of somebody who knows what they’re doing.

I am as guilty of soulless gear worship as anybody. Probably more so, in fact. Just to pluck one example from what is an embarrassing array of unnecessary upgrades: I still have the first ski pack I ever purchased, in the 1990s. It’s a red North Face model with a stout hip belt and a healthy 30-liters of space. There’s not a thing wrong with it. But I’m now on the fourth or fifth generation of pack since, having long since left the North Face bag to a closet corner where humans don’t venture.

I don’t want to completely miss the point, of course, that getting new gear is fun—and getting to use it even more so. The right piece can rejuvenate a stale pursuit or, in the best cases, it can elevate our own game like the way a lighter bike frame can get us up the mountain or a better-shaped pair of skis can get us down it.

From one year to the next, manufacturers often tweak their best gear with a color update, an extra feature or a slight form change. And that’s just fine. What else is Patagonia to do with its impeccable Down Sweater? The 800-fill insulator is efficient, handsome and classic.

What’s more interesting, however, is the annual batch of gear that’s wholly new, completely redesigned and, in those rare occasions a piece of outdoor schwag can earn such a distinction: innovative. Every year brings a few such items to the fore. And while many places are now chirping about the best of next year’s gear (the stuff you can’t yet buy), here’s our top 5 pieces of best new gear for this year, 2013:

The Tov: Down that stays dry.

1. Sierra Designs DriDown Tov Jacket $259

There aren’t many products that come along and utterly improve an entire class of gear, but that’s what Sierra Designs managed to do with their DriDown line.

For decades, climbers, skiers and hikers who faced the prospect of damp conditions had to hedge away from using down as an insulation in their gear for fear of it getting wet and losing its loft and insulating power. The answer has always been water-resistant synthetic insulation, which has come miles from where it was and now provides an excellent option—but only down insulates as well as down.

With DriDown, unveiled this season, Sierra Designs gives us a new option—600-fill down that’s treated with a polymer that coats to the molecular level, giving each down plume a hydrophobic finish. The result is down that, while holding on to its best-in-nature volume-to-weight ratio and insulating properties, also stays dry 10 times longer, retains 170% more loft and dries 33% faster when exposed to moisture compared with normal, untreated down.

Sierra Designs is also putting the stuff in sleeping bags (bye, bye, lumpy synthetic fill bag!), but we love the Tov Jacket for its versatility as a go-alone winter piece or, on really cold days on the mountain, a layering piece that holds up even if we do a little sweating on a hike or a boot-pack.

Other manufacturers are scrambling to follow Sierra Designs’ lead, so expect to see competitors to DriDown on the market next year. But they’ll be hard-pressed to pick a better name than DriDown—and Sierra Designs will be one year smarter than the rest of the pack. Bravo to SD and their Tov.

2. North Face Powder Guide ABS Vest $1,379

TNF ABS Vest: light, efficient and potentially life-saving.

A few years ago, some bizarre looking packs began showing up on the backs of the most hardcore of skiers. The packs had burly shoulder straps and a conspicuous handle—something like a parachute pull—sticking out from the wearer’s left strap. And just as pulling a parachute cord saves the user from splatting into terra firma, the pull on these packs deploys a single or double balloon that’s supposed to keep the user from getting buried in an avalanche.

To be fair, a parachute cord is supposed to be pulled on every jump. These avalanche packs are the last line of defense; it’s best not to test their efficacy. But they do work – they won’t save anybody from going over a cliff, but they can help keep a user on top of a churning flow of snow, decreasing the odds of deep burial. The balloons also provide the wearer extra visibility to rescuers amongst the avalanche debris and, in the event of a burial they can form pockets of air inside the snow, giving the user a longer lifeline until help arrives.

The only nit on some of these packs is their size and heft; the mechanisms and gas canisters fill up a lot of room and can be unwieldy, especially for ski patrollers or side-country users who ski uncontrolled terrain just outside a resort’s gate. The innovative answer to these problems comes in the form of The North Face’s Powder Guide ABS Vest, which packs all of the functionality of a normal ABS pack into a nifty package that sits evenly on a user’s torso.

Like a good side-country pack, the vest includes pockets for an avalanche probe and shovel handle, as well as exterior storage for the shovel’s blade. The vest has straps for carrying skis as well, so it makes for a good mate on steep boot-packs.

December 3, 2012

The Top 10 Ski Resorts in the United States for 2013

Rankings have become so ubiquitous in our world – top colleges, top cities, top jobs, top sandwiches – that they’ve begun to lose value. Everybody has a ranking about everything. Making matters more confusing, most rankings get so granular that nearly every person, place and thing is ranked No. 1 for something.

Wear a helmet: The home to Corbet's Couloir retained its No. 1 ranking for 2013.

In the ski world, there’s been a bit of this specialization ranking creeping in as well. To be sure, some of it is fair. Winter Park, for instance, can’t compare its terrain to that of Snowbird, but the Colorado resort does offer some of the greatest access to disabled and adaptive skiers in the world – and it deserves credit for that. Other outlets rank snow, grooming, family friendliness, food, lodging, customer service and even the quality of the booze on mountain.

All of those things matter to somebody. But here we only rank one thing: Awesomeness. It’s the most important thing we can measure. If you can know a place’s awesomeness, do you need to know anything else?

Answer: No.

We measure awesomeness with strict adherence to quantitative and scientific methods. The rankings you see here are the product of the most honed algorithms ever unleashed on the ski world. Being on this list means something. It means awesomeness. We don’t rank 50 resorts, we rank only ten — and we’ve included extended and 100% new material on the top six.

There’s nothing east of the Rockies on the list because no resort east of the Rockies has the snow or terrain to crack our awesomeness rankings–something that matters for both beginners and experts (soft western snow >> eastern ice). Not that there isn’t fun to be had in the East or even the Midwest. Ski wherever you can. We plan to do a separate, eastern list next year.

Again, we rank awesomeness and awesomeness only. If you want to find out what ski resort has the best hot chocolate and marshmallow bar, you’ll find that list elsewhere. If you want the hard facts on what ski mountain gives you the best possibility of a soul-moving experience on and off the snow, then you need rankings based on our patented Pure Awesomeness Factor. In the ski business, this is known as PAF. It’s not something that resorts make public, but every mountain knows where it stands. Most big resorts employ at least three data scientists who spend their days looking for methods to raise the resort’s PAF score. Boost that score, and you get closer to excellence.

Awesomeness is the only proxy for awesomeness. It’s the critical path to a vacation that becomes legendary. So for the second time ever, here are the top ten resorts in the United States according to PAF:

Everything is big--and awesome--at Jackson Hole.

1. Jackson Hole, Wyoming (PAF = 98.5):

The lift lines at Jackson Hole Mountain Resort are like those at a highway rest area bathroom at 2:00 a.m.: Almost nonexistent, except when they exist. And just like that line at the bathroom, if a queue has grown large at Jackson Hole, then there is probably a great reason to get in it immediately.

One of the few spots where lines used to bubble up at Jackson was at the Thunder chairlift, which gets skiers to the hairier southern side of the resort. On a powder day, Thunder was to be avoided; you planned your morning around it. JHMR is a place run by skiers and they were more than aware of the choke point Thunder created.

So before last season, the people in charge installed a new chairlift, Marmot, whose base sits adjacent to that of Thunder’s. It functions as a pressure-release valve for Thunder and provides the dual purpose of getting skiers back to the top of the Bridger Gondola for a snack or lunch without forcing them to ski to the bottom of this very tall mountain. One medium-sized lift, one huge improvement.

All of the other things that made Jackson No. 1 in last year’s rankings remain true. It’s still the best skiing mountain in North America. It still has the best continuous fall line, the best terrain and the best backcountry of any mountain not in the Himalayas. And there’s that $30-million ascending jam fest of music, sweat and rollicking cheers, also known as The Tram, which offers the best return on 10 minutes of standing that you’ll ever be offered (all 4,139 feet of vertical, at once).

Jackson gets extra points for coming through with decent snow last winter (the winter that wasn’t) when most of the country’s ski resorts were still putting up with random patches of brown grass on January 15. And it never hurts to have the most famous ski run in the world – Corbet’s Couloir – inside the boundaries.

On top of skiing, Jackson has come into its own as a culinary destination, a nifty feat for a place so small and thinly populated. The area is awash in new and creative eateries: Roadhouse Brewing Co., the Handle Bar at the Four Season (a Michael Mina concept), a great contemporary spot in town in The Kitchen, and the reincarnation of a longtime local favorite, Billy’s Burgers. On the mountain, don’t miss waffles stuffed with Nutella and bananas at Corbet’s Cabin.

A minor gripe on the foot front (very minor): one of this column’s favorite restaurants in Jackson, Trio, made the mistake last winter of messing with one of the best burgers in America when it switched its meat patty from local bison to ho-hum angus beef. It remains a fine burger, but it no longer stands out from stalwarts in New York and Chicago.

No time to eat? You can still have it all: Stuff your pockets with Tram Bars, the most delicious energy bar in the world, sold all over at Jackson Hole and made just over the ridge in Victor, Idaho.

Snowbird: Best snow, epic terrain, epic lift.

2. Alta and Snowbird , Utah (PAF = 97):

For most people, these two resorts that occupy a splendid apron of Little Cottonwood Canyon just 35 minutes from downtown Salt Lake should be the default ski vacation. Direct flights to Salt Lake can be had from most cities and the trip from the airport to the snow here is a leisurely stroll compared with the white-knuckle pilgrimage between Denver and Colorado’s resorts.

We rank Snowbird and Alta together because they are together. They share a boundary line and even, for those who choose to purchase it, a joint lift ticket. If you go to one, you should go to the other. Unless you’re a snowboarder, in which case Alta won’t allow you to plow through its chutes and trees—and what glorious chutes and trees they are.

The terrain at Alta and Snowbird is the terrain against which all others are measured. Snowbird’s tram, which, like Jackson‘s, also traverses from the base of the resort to the top, is the only lift that compares with the tram at Jackson Hole. The lift line for the Snowbird tram on a prime powder day can get ugly—one of the drawbacks of being on top of a greater metropolitan area of 2 million people.

The good news is that not all of those people ski and, even better, this place has a lot of powder days—it gets 600 inches a year—more than anywhere outside of Alaska. The snow is dependable and comes in a density that’s user friendly, like a stiff dollop of whipped milk on a cappuccino. If you’re going on a trip for three days or less, it’s hard to go anywhere but Utah. We can’t stress enough how awesome the skiing is here. If you haven’t been, just go.

Not to be missed: Snowbird’s Cliff Lodge, a wonderful modern building whose raw, reinforced concrete edifice evokes the work of architect Paul Rudolph, a brilliant shaper of glass and poured stone.

November 13, 2012

The 86-Year-Old Startup Guru

Y Combinator's startup school is awesome. But maybe we should get some old school wisdom up there. Really old.

Two years ago, just before Thanksgiving, one of the 100-year-old sewer pipes in my yard collapsed. I thought I could hack a solution at a reasonable cost, so I hired two men to dig up the broken pipe.

It was brutal work in the cold. About halfway through the first day of the project, while the diggers took a break, I noticed there was now a third man in the hole. It was my neighbor, Chuck, who was asking the workers about the dense soil at the bottom of the pit. Chuck had the pickaxe in his hands and was preparing to take a swing.

I put a stop to the whole thing and helped Chuck, who was wearing the clothes of a laborer, out of the hole. Chuck is 86 years old and he will crawl up your roof to find a leak in a snowstorm if you let him. He can also tell you everything you need to know about hiring people, pitching big companies for sales, and creating a healthy culture at your startup. As it turns out, the things we value at contemporary tech startups—values that many of us assume sprouted with the tech boom 15 years ago—are the same things that helped companies thrive thirty, forty or fifty years ago.

Creating a culture

The first thing Chuck told me when he heard about our startup, Aisle50, was, “Treat your employees how you’d want to be treated.”

When he told me that, his eyes gauged my reaction. He knew it sounded trite.

“I mean it’s the simplest thing in the world, but that’s why it’s so great” he explained. “That’s really all you have to do—and it’s what you owe your employees.”

Do that, Chuck said, and much of your company culture will take care of itself.

Startups hold working environments dear. Free lunches, beer fridges and nonexistent dress codes help put a demonstrative line between startup culture and that of big companies. At the heart of this culture there’s the essence of a cubicle-dweller saying to himself : “If I had a company, here’s how I would do things.”

The man in the trenches would treat others how he wants to be treated. It really is that simple. But this isn’t about not working hard or piles of free sandwiches. The right people want to work hard, they just want opportunities to go along with that. This is about giving people the things you want out of your own career: true responsibility and the opportunity to grow. Giving people these chances results in a better company, a better product and better and happier employees. Since we hired our first employee about a year ago, Chuck reiterates this point every time I see him: “Treat people like you want to be treated.”

Chuck graduated from the Illinois Institute of Technology with a degree in mechanical engineering 60 years ago and went to work for a large manufacturer designing hydraulic valves. Full of ideas, Chuck regularly brought new designs to upper management, thinking he could greatly improve the company’s devices. The problem, though, was that nobody cared. Just as Clayton Christensen would inform us of 50 years later, Chuck found for himself how hard it is to innovate at big companies. So he left.

Clayton Christensen learned what Chuck knew a long time ago.

Building on his designs, Chuck eventually secured 12 U.S. patents and began manufacturing his own hydraulic valves. By the time he was 40, his company was 75 people. At the age of 41, Chuck sold to United Technologies and hasn’t needed to work since. That was in 1969.

Chuck still lives in the same modest brick house he bought 40 years ago with a yard so small there isn’t room for a garage. One recent fall day, as I walked home from the train, I ran into Chuck as he was finishing the job of applying a second coat of stain to his fence, which has several layers of cedar slats all the way around. It’s an impressive task to see to completion for an 86-year-old.

More impressive, though, was the 600-square-foot concrete parking slab Chuck poured for a neighbor the summer before. He excavated the area by hand with a spade, built the forms, spread out gravel and laid steel reinforcing bars. When the concrete truck showed up, he stood in the gray muck, raking it into place and then, on his knees, smoothing its surface with a trowel in 95-degree heat. He charged the neighbor nothing, not even for materials. After another neighbor complimented his work, Chuck then replaced part of the second neighbor’s sidewalk the following week. This is a man who still brims with the energy of a 25-year-old startup founder.

Make that last call

When my cofounder and I quit our jobs and made our startup “official,” some of our friends and relatives were skeptical, some were inspired, and some were incredibly happy for us because, over the years, we had fooled them into having more confidence in us than we had in ourselves.

September 27, 2012

As Europe, Canada Try To Control Bot Traders, The U.S. Falls Behind

Word that Europe, Canada and now Australia are taking steps to curb the power of high-speed algorithmic traders should be of little surprise. Aside from last decade’s explosion of bot trading in the United States, European markets and others have normally been a step ahead of the American markets in utilizing and understanding technology.

Europe was the place Thomas Peterffy, the programmer who made himself into a billionaire, turned to after hacking the Nasdaq in 1987. Frustrated with the collusive forces that controlled American markets and kept technology out of them in the early 1990s, he began taking on markets in Germany, the UK and other spots. Back then, there was still a great amount of utility to be gained by automating some aspects of trading. Doing this brought trading to the normal man’s laptop for $7 a trade.

Automated trading is taking us to strange place.

But we’ve had cheap trades for more than a decade. The utility of going faster, faster and faster, at this point, has been exhausted. We may have not reached terminal velocity, but we’ve reached terminal efficacy as it relates to speed. Shaving a millisecond—or, as some technologies seek to do, a mere microsecond—benefits nobody except the guy stepping in front to make the trade.

Additional speed, at this point, only introduces more risk into our markets. Risk of catastrophic failure, rick of chaos, risk of circus displays like the flash crash of 2010 that, while some market people call the episode harmless as the market did recover most of its losses rather quickly, they underestimate the steady erosion of the public’s trust in our markets. When retail and institutional orders taper off, the algo traders cease to have anybody to play with; algos can only trade nickels amongst each other for so long. Such an outcome is bad for everybody – including the companies that normal people want to own: Apple, Google, Wal-Mart, Exxon Mobile.

European regulators have suggested making rules that make traders keep a bid or offer live for at least half a second, which amounts to an eternity to U.S. algo traders, most of whom spend more time faking out opponents by cancelling trades as soon as they’re offered than actually offering trades they want executed. The deluge of orders, most of them irrelevant, has pushed our exchanges to the breaking point. Data pipes are overbuilt to the point of hilarity. By making people offer trades that they actually want executed, which is what a half-second minimum would do, the Europeans could restore some sincerity to their markets.

Canadian regulators also have a novel approach: they’ve suggested charging traders for the amount of data they fire at exchanges. A “fake” order will no longer be free, which will discourage the strategy of “quote stuffing” to overwhelm competitors who employ inferior hardware and software that can’t parse the data fast enough.

The free-markets-forever crowd will yell that these strategies somehow threaten our markets’ freedom, but that claim seems rather hollow. The markets charge traders now for all matters of things: co-location, faster data feeds, trades that are actually executed. Taking a fee for every trade fired at an exchange would remove some of the haze that surrounds our market structures that have grown so esoteric that big trading firms must woo particle and quantum physicists to its fold.

The stock markets were designed to get money to growing companies that could put it to best use and, in the process, give normal people a way to invest their cash in vehicles with the potential for growth. There’s always been risk involved, but that risk came purely from the company being invested in, not from a labyrinthine market structure that requires a Ph.D. to navigate.

A couple of simple rule changes could go a long way toward healing the foibles of our markets while retaining the efficiencies of the algorithm-driven bots that have come to rule them.

So now, strangely, the United States can sit back and observe the leadership of Canada.

Christopher Steiner is a former Forbes magazine staff writer and the author of the new book, Automate This, How Algorithms Came to Rule Our World.

September 19, 2012

The Original Hacker and Why His Work, 300 Years Ago, Matters Today

Note: The following is adapted from Automate This, How Algorithms Came to Rule Our World, a book just released by Penguin-Portfolio.

Alan Turing is often given the unofficial title of being the original hacker. He’s a worthy choice. His 1950 essay, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, is still consulted today by those contemplating the gap between software and human brains.

But Turing was able to use machines that were built on the work of others as decades of hardware progression continued to push toward the semiconductor age. And what of the theory behind the hardware? Some form of it had to come first, of course. George Boole, for one, conceived of devices—Boolean operators—that still dot programming today. Their roots trace to Boole’s 1854 paper, An Investigation of the Laws of Thought, on Which Are Founded the Mathematical Theories of Logic and Probabilities.

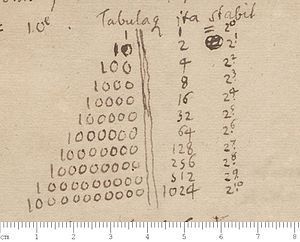

Binary numeral system - "Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz" first draft in his new years letter (january 1697) to "Herzog Rudolf August von Wolfenbüttel" (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Before Boole there were others: Euclid, Euler, Newton and the Bernoullis. They all contributed. Naming one of them the original hacker requires a dash of subjective judgment. A case could be made for a dozen people. But none of them, in this writer’s opinion, quite so fill the role as does Gottfried Leibniz, a German who preceded iOS by 360 years.

Leibniz, like Newton, his contemporary, was a polymath. His knowledge and curiosity spanned the European continent and most of its interesting subjects. On philosophy, Leibniz said, there are two simple absolutes: God and nothingness. From these two, all other things come. How fitting, then, that Leibniz conceived of a calculating language defined by two and only two figures: 0 and 1.

Leibniz developed this system to express numbers and all operations of arithmetic—addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division—in the binary language of 1s and 0s. The mathematician defined the language in his 1703 paper Explanation of Binary Arithmetic.

Leibniz was born in Leipzig in 1646 on a street that now bears his name. An overachiever from the start, he began university at fifteen and had his doctorate by the time he was twenty. Known for being gregarious, he chatted up his physician on the subject of alchemy as he lay dying in bed at the age of seventy. The large shadow of Leibniz in this story traces to his convictions about the breadth with which his binary system could be applied. He thought far beyond the erudite world of math theorems and the Newtonian wars of calculus theory.

All physical changes have causes, Leibniz said. Even people, to some degree, have their paths set by the outside forces acting upon them, a fact that game theory, developed long after Leibniz’s time, exploits. Leibniz therefore believed that the future of most things could be predicted by examining their causal connections. This is what much of the modern Wall Street titans have realized better than anybody else.

Before anyone else, Leibniz conceived of something reaching toward artificial intelligence. The mathematician stipulated that cognitive thought and logic could be reduced to a series of binary expressions. The more complicated the thought, the more so-called simple concepts are necessary to describe it. Complicated algorithms are, in turn, a large series of simple algorithms. Logic, Leibniz said, could be relentlessly boiled down to its skeleton, like a string of simple two-way railroad switches comprising a dizzying and complicated national rail network. If logic could be factored to a string of binary decisions, even if such sequences stretched for miles, then why couldn’t it be executed by something other than a human? Leibniz’s dream of reducing all logical thought to mechanical operations began with a machine he designed himself.

Great hackers are competitive. Leibniz was no different. After hearing of an adding machine built by Blaise Pascal, Leibniz set out to best him. His machine would perform addition and subtraction more smoothly and could also solve multiplication and division problems, something Pascal’s machine couldn’t do at all. Putting the design down on paper, Leibniz hired a Paris clockmaker to make the device a reality in 1674.

August 30, 2012

How the Nasdaq Got Hacked

ON A DAY IN EARLY 1987, a man who worked for the Nasdaq stock market—let’s call him Jones—showed up in the lobby of the World Trade Center. He found the appropriate elevator bank for his floor and pressed the up button. He was making a routine visit to one of the Nasdaq’s fastest-growing

customers.

A receptionist greeted him and retreated to another room to fetch his host. When she returned, a short, dapper man with a full head of silvering hair accompanied her. Thomas Peterffy’s blues eyes warmly greeted Jones. He spoke with an accent.

Jones couldn’t have known that Peterffy would later become a man worth more than $5 billion, one of the richest people in America. He was still at that point a Wall Street upstart. But his trading volume had been streaming upward, and so had his profits. Jones was always curious as to how people like Peterffy figured out ways to beat the market so consistently. Had he hired the sharpest people? Did he have a better research department? Was he taking giant risks and getting lucky?

What Jones didn’t know was that Peterffy wasn’t a trader at all. He was a computer programmer. He didn’t make trades by measuring the feelings of faces in the pit, the momentum of the market, or where he thought economic trends were leading stocks. He wrote code, thousands of lines of computer language—Fortran, C, and Lisp—all of it building algorithms that made Peterffy’s trading operation one of the best on the Street, albeit still small. He was chief among a new breed on Wall Street.

As Peterffy led the way onto his trading floor, Jones grew confused. The more he saw—and there wasn’t much to see—the more flummoxed he became. He had expected a room bursting with commotion: phones ringing, printers cranking, and traders shouting to one another as they entered buy and sell orders into their Nasdaq terminals. But Jones saw none of this. In fact, he saw only one Nasdaq terminal. So who was making all those trades?

“Where is the rest of the operation?” Jones demanded. “Where are your traders?”

“This is it, it’s all right here,” Peterffy said, pointing at an IBM computer squatting next to the sole Nasdaq terminal in the room. “We do it all from this.” A tangle of wires ran between the Nasdaq machine and the IBM, which hosted code that dictated what, when, and how much to trade. The Nasdaq employee didn’t realize it, but he had walked in on the first fully automated algorithmic trading system in the world.

With the hacked data feed coming from the Nasdaq terminal, Peterffy’s code was able to survey the market and issue bids and asks that could easily capture the difference between the prevailing price at which buyers would buy and sellers would sell. That difference, called the spread, could grow past 25 cents a share on some Nasdaq stocks at that time, so executing a pair of 1,000-share orders—one to buy at $19.75 and one to sell at $20.00—resulted in a near-riskless $250 profit.

Peterffy’s operation marked a new dawn on Wall Street, as programmers, engineers, and mathematicians mounted a two-decade invasion in which algorithms and automation, sometimes incredibly complex and almost intelligent, would supplant humans as the dominant force in our financial markets.

Jones stood agape. Where Peterffy saw innovation, Jones saw somebody breaking the rules with a jury-rigged terminal.

“You can’t do this,” Jones said.

Christopher Steiner's Blog

- Christopher Steiner's profile

- 21 followers