Chris Gavaler's Blog, page 8

May 27, 2024

Reboot Culture & Revising Reality

I think it’s fair to say that William Proctor is the world authority on reboots. I’ve followed his articles for a few years, and he’s now written the definitive book on the topic. Reboot Culture was published last November — after Nat Goldberg and I had submitted the final draft of our Revising Reality, which launches at the end of May.

Though we couldn’t cite Reboot Culture, Revising Reality does build on it by applying its fiction-based narrative revision approach to the real world. I recently reached out to William Proctor — who goes by Billy in his emails — to praise his work and share ours. I enjoy what they have in common and where they diverge.

Billy opens by noting the “surge in alternate uses of the computer term ‘reboot,’ a surge that has seen the term deployed in new contexts and new signifying practices. Most pronounced in press discourse, the term has taken on a dizzying array of applications, employed for all manner of purposes and topics.” For his purposes (made explicit in his subtitle Comics, Films, and Transmedia), even “as a narrative concept” the term “remains one of the most widely misused, misunderstood, and misinterpreted concepts in recent years.”

Nat and I noticed the same when first writing about comics reboots for a chapter in our first book, Superhero Thought Experiments (Iowa 2019). We therefore offered an especially precise definition when revisiting and significantly expanding our analysis in Revising Fiction, Fact, and Faith (Routledge 2022). Revising Reality is friendlier to non-academics, so offers a simpler approach. We also swap terms, as we explain in our intro:

“Though ‘remake’ used to refer to new versions generally dates to at least 1890, its primary use now relates specifically to film and related media. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, it may have been first applied to the musical The Desert Song in a 1936 Variety article about a new stage production of the 1926 Broadway show. The term ‘reboot’ entered the vernacular in the 1970s, referring then only to computers, until its meaning was in its own way sequeled to include films. The OED cites the possible first usage in a 1998 Cedar Rapids Gazette article about ‘the reboot of Superman that wiped away nearly 50 years of continuity.’

“’Reboot’ is the preferred term in comics and may have first appeared in print in a 1994 post on a DC UseNet message board. Some use ‘remake’ and ‘reboot’ interchangeably. In a 2023 New York Times review of recently rebooted TV shows (Night Court, Scooby-Doo, That ‘70s Show), Elizabeth Nelson notes both the ambiguity and overlap in terms: ‘’Reboot” is one of those coinages that burrows into the lexicon without ever being fully explained (at least to me), but it has clearly supplanted ‘remake,’ migrating over from the language of computing.’ Respecting precedence, however, we opt for the earlier term.”

Billy of course opts for “reboot,” clearly distinguishing it from “remake”:

“Unlike remakes and adaptations, both of which function as ‘announced and extensive transposition[s] of a previous work’ (Hutcheon 2006, 7), what ‘may be said to identify a reboot is the fact that it initiates a series of texts’ (Gil 2014, 25–26, my italics).”

The “series of texts” is a smart point, which Nat and I set aside for the overall shared point that Billy describes:

“Unlike other serial processes, however, each of which extend ‘an already existing narrative sequence’ (Wolf 2012, 381), reboots instead ‘restart an entertainment universe that has already been established, and begin with a new story line and/or timeline that disregards the original writer’s previously established history, thus making it obsolete and void’ (Willits 2009).”

He also goes well beyond narrative, exploring the concept as an “economic strategy mobilized to discard, supplant, or nullify an established serial continuity by beginning again from square one.”

Nat and I explore a range of entertainment universes (Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, Marvel, DC, Ghostbusters, and even Roseanne) in our first chapter, noting how fans wield the power to reject remakes/reboots and other revisions, before applying thems to nonfiction for the rest of the book. Billy’s definition reveals the core challenge: in the real world, you can’t “nullify an established serial continuity by beginning again from square one.” You can only pretend to by passing off a new set of details as historical facts.

So where Reboot Culture delves into the multi-reboot histories of fictional characters like Superman and Batman, Nat and I look at the remade histories of real people like Paul Revere and Ronald Reagan.

According to current mythology, Ronald Reagan cut taxes, reduced the deficit, shrunk government, and punished illegal immigrants. The actual Ronald Reagan instead raised taxes eleven times, grew the federal deficit by 142%, increased the U.S. gross domestic product, and proudly granted amnesty to three million undocumented immigrants. The mythological Reagan is a work of fiction that remakes or reboots the actual Reagan by replacing him.

That reboot doesn’t start from “square one” though. It instead inserts the fictional Reagan into the past. Reboot Culture describes a related phenomenon from the Batman franchise:

“Batman V Superman may reboot the Dark Knight as diegetically independent from Nolan’s films, but it does not ‘begin again’ by reproducing the origin story. In fact, Affleck’s Batman has been in operation for some time, yet another reference to Miller’s DKR and its depiction of a grizzled, battle-worn Dark Knight. From this perspective, I would argue that it is a different type of reboot, one that begins a third wave of Batman films midway through the story, or at least midway for Batman as Man of Steel rebooted Superman from ‘year zero.’ For these reasons, I would describe Affleck’s Batman as an in media res reboot, with Batman V Superman enacting a double function as both sequel to Man of Steel and a reboot of Batman.”

The Reagan myth isn’t exactly an “in media res reboot,” since it occurs entirely in an imagined past — arguably the same nebulous golden age evoked by the “Make America Great Again” slogan. Since it doesn’t start either at the origin or in the middle, maybe we should call it an “aftermath reboot”?

Whatever the term, I wish it intruded only in fiction.

May 20, 2024

Retcon Game & Revising Reality

In his 2017 Retcon Game: Retroactive Continuity and the Hyperlinking of America, Andrew Friedenthal explores the role played by retconning in popular culture, before turning in his final chapter to Wikipedia and its perpetually revisable entries. Friedenthal focuses on Paul Revere’s Wikipedia entry, which was revised (and revised and revised) in 2011 after former Alaska governor and Republican vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin made erroneous comments that her supporters then inserted, until the editors blocked further revision by freezing the page.

“Our own, real-world continuity,” concludes Friedenthal, “is constantly retroactively changing, and the fact that increasingly we accept this as the way of the world (and of the past) goes to show just how well our media and escapist entertainments have prepared us for this important moment.”

Of course, our own, real-world continuity is not retroactively changing. History in the sense of past events doesn’t change. The stories we tell about it, the history of history, does. Exploring that interplay is the focus of Nat Goldberg’s and my new book Revising Reality.

Because we are not culturally accustomed to thinking about revisions in the real world—or rather we are accustomed to only one kind of real-world revision, sequels—understanding revisionary changes in the history of history requires the tools of fictional revision. While the taxonomy is helpful, the concepts are essential. We can best understand reality through the lens of sequels, remakes, retcons, and rejects.

Revising Reality is available at the end of May. Because our research builds on his (the above paragraphs appear in the intro), I reached out to Andrew Friedenthal to offer him a copy. He revealed that not only did he know about our book but he had already read it as an external reviewer for Bloomsbury and given it a rave review (which I posted in “Some Extremely Nice Things That People I Don’t Know Said About What Will Now Be My Next Book“).

Since Andrew is arguably the world expert on retcons, he was an ideal reviewer. The Retcon Game is all about “retroactive continuity,” which he defines as: “a narrative process wherein the creator(s) and/or producer(s) of a fictional narrative/world—often, but not always, the same person or people—deliberately alter the history of that narrative/world such that, going forward, future stories reflect this new history, completely ignoring the old as if it had never happened.”

He subdivides retcons into a three-part taxonomy:

“reinterpretation, changing how an earlier work is seen and interpreted, but in a less-than definitive way, allowing for some choice on the part of audience members to determine which history is still considered canonical to the narrative.”“reinscription, which is a more solidified change to how an earlier work is viewed, concretely and canonically changing that work’s meaning going forward.”“revision, wherein an older work is not only viewed differently, but even altered through republication, editing, new editions, and so forth, such that the material text itself is now different in the physical world, not just in the minds of characters and/or audience members.”After offering a painstaking definition in our previous book, Revising Fiction, Fact, and Faith, Nat and I are simpler in Revising Reality: “While a prequel fills in past information, a retcon does the same while also causing an audience to reinterpret and discard some previous impression.”

And I think we look mainly at Andrew’s first subcategory, “reinterpretation,” and possibly “reinscription” too, but “revision” we would move into the reboot bin.

The terms aren’t important, but what they describe is. Like Andrew, Nat and I also look at Paul Revere (who I originally blogged about over a decade ago in “Paul Revere: Superhero or Jihadist?”, a post which has since received a surprising 4,300 views). Nat and I write in Revising Reality:

Paul Revere died in 1818 but was reborn—or remade—in fictional form in 1861. That (fictional) rebirth gave him the strength of three men and the power of bilocation: on the evening of April 18, 1775, he was both in the church tower swinging a lantern and on his horse across the river receiving the message. Fellow riders, William Dawes and Samuel Prescott, stumbled and vanished into the white space between the stanzas of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride,” the poem that created the larger-than-life American hero. When the actual, human-sized Revere died, his obituary didn’t even mention that not-yet-legendary midnight ride.

In the case of Revere, fiction replaced fact—or, more specifically, mythology replaced history. While any account of a historical figure differs, sometimes significantly so, from that figure’s actual life, historical myths do more than misreport. They are works of fiction. They are fictional histories, or stories, of actual histories, or past events. Longfellow knew he was not reporting on Revere correctly, and not incorrectly either. He was creating a new and different Revere, inspired by the actual person, but also distinct.

If Revere were Batman, we would call Longfellow’s poem a “remake” or “reboot.” Except in the Batman case, the original was fictional also, while in Longfellow’s, the original was factual. Remakes of Batman remake stories about him, which, because Batman’s fictional, amount to remaking the character too. Christopher Nolan’s 2005 Batman Begins remakes Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman, each telling a story about a similar but ultimately distinct Bruce Wayne’s superheroic adventures in a similar but ultimately distinct world. More recent DC movie installments do the same. Remakes of Revere also remake stories about him, but, because Revere’s factual, they don’t actually remake the historical figure. Longfellow read historical accounts of the historical Revere, selecting, discarding, and altering details to create his own, fictional version.

All historical fiction remakes actual historical accounts—stories of past events, not the events (or individuals) themselves—into fictional historical ones. Longfellow wasn’t trying to pass his poem off as fact, but some authors of fictional remakes do. They’re called hoaxes.

In 2016, social-media users claimed Hillary Clinton was running a pedophile sex ring in the basement of a DC pizzeria. The Pizzagate conspiracy theorists convinced other people, including a gunman who entered the building planning to liberate the children, that what they said was true, even though those who initiated the false alarms must have known otherwise.

Andrew’s analysis of Paul Revere instead stems from Sarah Palin, who said while campaigning:

“he warned the British that they weren’t going to be taking away our arms, by ringing those bells and making sure, as he is riding his horse through town, to send those warning shots and bells, that we were going to be secure and we were going to be free.”

Andrew writes:

“Pundits and analysts—particularly liberals who were opposed to Palin’s views and her close association with the conservative Fox News network—were quick to point out that Revere had actually rode carefully and quietly through the Boston area, warning colonists as to the arrival of British troops without alerting either Loyalists or the British themselves. In response, Palin’s supporters visited the Wikipedia page for Paul Revere, editing it so that it related her statements, rather than the research of credited historians, as the truth. Palin encouraged these changes by doubling down on her inaccuracy.”

Applying Andrew’s taxonomy, that looks like a “revision retcon,” since the facts about Revere are “not only viewed differently, but even altered through republication, editing, new editions, and so forth, such that the material text itself is now different in the physical world.”

Nat and I call that a kind of “remake” or “reboot,” because Palin’s supporters altered the Wikipedia entry with false information that they were passing off as true. It was a hoax. Perhaps Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride” is too. Worse, unlike Palin’s supporters, his fictional remake has successfully replaced facts about the actual person.

Palin said: “I didn’t mess up. I answered candidly and I know my American history.”

She must have meant Longfellow’s rebooted American history, where, unlike the actual Revere, his more famous fictional counterpart rode very loudly:

So through the night rode Paul Revere;

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

To every Middlesex village and farm,—

A cry of defiance, and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo forevermore!

“Just like in our fictional universes,” concludes Andrew, “our historical reality does not continually stay the same.”

May 13, 2024

Will Eisner’s Memory is a Cartoon (and so is yours)

The Eisners, the comic book industry’s equivalent of the Oscars, is named after Will Eisner, arguably the most highly regarded U.S. comics artist of the twentieth century. Eisner also has the distinction of appearing as a witness in the first comic book lawsuit. According to the 1940 decision reached in Detective Comics, Inc. v. Bruns Publications, Inc., one of Eisner’s first creations, Wonder Man, published by Victor Fox’s comics company, infringed on DC’s copyrighted Superman.

Eisner agreed with the verdict, telling his biographer Bob Andelman: “Victor described the character exactly the way he wanted him in a handwritten memo. Obviously, a complete imitation of Superman.” Andelman continues that Eisner “decided that he couldn’t commit perjury and, when called to the witness stand, he testified that Fox literally instructed Eisner & Iger to copy Superman.”

Andelman published Will Eisner: A Spirited Life in 2015, a decade after the artist’s death. Though we don’t know the date Eisner reported his account of the court scene, it was likely more than a half century after the event.

Eisner also gave interviewer John Benson a similar account in 1979: “when I did get on the stand and testified under oath, I told the truth, exactly what happened.” Eisner’s 1985 graphic novel The Dreamer includes a thinly veiled fictional account of the court scene too.

When the prosecutor asks, “Did he specify the nature and design of each you did for him,” Eisner’s counterpart answers truthfully if irrelevantly: “Well, not every one.”

“But in the case of ‘Heroman,’ did he specify in detail what costume to use?”

“Yes.”

Yet the actual court transcripts that Ken Quattro (who also noted Eisner’s 2015 and 1979 versions) discovered in 2010 show that Eisner testified that he had never read, seen, or even heard of Superman before creating Wonder Man. Eisner committed perjury in 1940 and lied about it in 1979 and afterward.

Unless he didn’t.

A lie requires knowing that something is false and presenting it as true. And there’s reason to think that Eisner believed he was telling Andelman, Benson, and his readers the truth.

Neuroscientists Lisa Bortolotti and Ema Sullivan-Bissett in a 2018 study describe clinical memory distortions of people with dementia:

“the distortion can be construed as motivationally biased, and the distortion can be seen as part of a defense mechanism. . . The person enhances the past by denying something unpleasant or providing an embellishment or a rationalization of it,” such as a woman with amnesia “who ‘rewrote’ the story of her family relationships to emphasize love and cohesion and downplay tension and disagreement.”

People with dementia, they continue, “often undergo a change in their personality traits as a result of the illness,” but they “may have no awareness of these changes and tend to describe themselves as they were before the illness.”

The distorted reports have benefits, increasing “self-confidence by providing an illusory sense of competence” and increasing a “sense of self-worth by enabling the construction of a better self and of a better reality.” The more advanced the memory impairment, the greater the increase in well-being, perhaps because “there are fewer reality constraints operating on memory, and people enhance their own image, more radically reconstructing their past selves more freely.”

Was Eisner suffering from dementia when he spoke to his biographer late in his life? Maybe. Was he when he spoke to his interviewer in 1979? Probably not. He was sixty. Only 5 percent of Alzheimer’s sufferers show symptoms before they’re sixty-five.

Social psychologists Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson provide an explanation unrelated to dementia, calling memory “the Self-justifying Historian” in their 2007 Mistakes Were Made (but not by me):

“most of us, most of the time, are neither telling the whole truth nor intentionally deceiving. We aren’t lying; we’re self-justifying. All of us, as we tell our stories, add details and omit inconvenient facts; we then give the tale a small, self-enhancing spin; that spin goes over so well that the next time we add a slightly more dramatic embellishment; we justify that little white lie as making the story better and clearer—until what we remember may not have happened that way, or even happened at all.”

This kind of sequeling, reinterpreting, replacing, and inserting fits Eisner’s case. In 1979 he reported generally that “I told the truth, exactly what happened.” In 1985 he added some details in his graphic novel version. It was only in his final version to his biographer that “he testified that Fox literally instructed [him] to copy Superman.”

Evoking George Orwell’s novel 1984 novel about nightmare totalitarianism, Tavris and Aronson continue:

“when we write our own histories, we do so just as the conquerors of nations do: to justify our actions and make us look good about ourselves and what we did and failed to do. If mistakes were made, memory helps us remember that they were made by someone else.”

Memories are like cartoons.

We take actual events and simplify and exaggerate them.

Neuroscientist Valerie F. Reyna calls the simplifying “gist memory,” that “tendency to connect the dots of meaning and then to report that rather than just the verbatim reality.”

Neuroscientist Yufei Zhao demonstrated an example of the second cartoon quality, exaggeration, in a 2021 study: “when remembering highly similar objects, subtle differences in the features of these objects are exaggerated.”

Both are invaluable for remembering—but not remembering actual events, which the memory revises.

Later memories then revise those revisions. Neuroscientist Donna Bridge explained in 2012:

“memory is not simply an image produced by time traveling back to the original event—it can be an image that is somewhat distorted because of the prior times you remembered it… Memories aren’t static. If you remember something in the context of a new environment and time, or if you are even in a different mood, your memories might integrate the new information… When you think back to an event that happened to you long ago—say your first day at school—you actually may be recalling information you retrieved about that event at some later time, not the original event… Your memory of an event can grow less precise even to the point of being totally false with each retrieval.”

Minds are partisan, even hyper-partisan, about themselves. Without the intervention of verifiable facts, each tends to assume its recollections and impressions are actual and accurate, and that other people’s contradictory recollections and impressions are mistaken.

Revisions of memories aren’t quite sequels, retcons, remakes, or rejects. They’re their own thing, which happens to share elements of each.

[excerpted from Chapter 7: “Changing Minds” of Nat Goldberg’s and my Revising Reality]

May 6, 2024

Transgender Sequels vs. Transgender Retcons

People don’t like retroactivity. That’s one of my main discoveries from co-writing my new book, Revising Reality, an application of fiction revision types (sequels, reboots, retcons) to real-world narratives (history, science, law, memory). A late chapter analyzes the personal histories of name changes, including trans names. And that’s the one place we found a preference for retroactive revision.

I’m reading Sarah Thankam Matthews’ excellent All This Could Be Different, and came across a passage about a nonbinary character. The novel was published in 2022 but is set during the Obama years, back when trans was a seemingly new idea. Two friends are talking about a girl one of them likes:

“Sorry, not girl, Emily uses they pronouns.”

“They pronouns? What in the world. Is this person a hermaphrodite?”

“You know, like a trans person. Well, nonbinary gender. Which is a subset, I think, of being transgender. Or maybe a superset. I’m not sure.”

“Oh come on.”

“What”?

“I get, I really get like, if you want to transition to living your truth as a woman or a man if you were born the wrong thing. I support that completely. Anything beyond that is elitist leftist American nonsense, honestly.”

The transphobic character divides trans people into two categories: “born the wrong thing” and “nonsense.”

She supports the first and ridicules the second. Why?

To answer, first analyze what kind of revision each performs.

If you’re transitioning to your true gender because you were “born the wrong thing,” meaning your body does not match your gender identity, then transitioning reveals who you actually are and always were from birth. That’s a retcon. Short for retroactive continuity. A new revelation reinterprets a past impression as false. Others (including perhaps yourself at some moments) thought you were one gender based on your appearance, but now that past impression is revealed to have been wrong.

The term comes from superhero comics, where characters routinely die and come back to life. Except they don’t. Because that would be a sequel. If Captain America was dead and later he was alive again, that’s a sequence of events. A retcon instead reveals that Captain was never dead, we just thought he was. His apparent death is retroactively erased. A trans person’s previous apparent gender is retconned in a similar sense. They never were that gender, you just thought they were.

Matthews’ possibly-not-transphobic character has no problem with that. She supports trans retcons. It’s trans sequels that upset her, reporting in hindsight how she was “hissing like a goose, surprised by my own anger.” She continues:

“This shit is hard for everyone! Do people think so-called cis people don’t, or haven’t, struggled with this shit? Feel fucking weird in their own bodies? … I spent all my teens wishing I could slice my breasts off, have a flat and smooth body. I cut up my bras with nail scissors. Got thrashed for it. Does that entitle me to a they? Can I opt out of gender now?”

The answer (in my opinion) is yes. That’s because, unlike the fictional character, I also support trans sequels. If the character, who is a queer woman, decided to “opt out of gender,” that would be a new event in a sequence of events. Previously she was a woman and now they would be nonbinary. No retroactive claim involved. And that apparently is what angers her.

The underlying logic is that gender identity is always fixed from birth, and so it can be retconned if that identity is bodily mismatched, but it can’t be sequeled. You are whatever you are, no opting out permitted. No options period. You decide whether to reveal your gender, but your gender doesn’t change as a result. That’s the point of retconning. And since the character had to persevere as a woman, Emily and all other people assigned female at birth have to persevere too. No sequels allowed.

Matthews’ character is fictional, and so no actual gender identity is involved, but here’s an excerpt from another author’s personal written in 2020 that expresses related attitudes:

“The writings of young trans men reveal a group of notably sensitive and clever people. The more of their accounts of gender dysphoria I’ve read, with their insightful descriptions of anxiety, dissociation, eating disorders, self-harm and self-hatred, the more I’ve wondered whether, if I’d been born 30 years later, I too might have tried to transition. The allure of escaping womanhood would have been huge.… I believe I could have been persuaded to turn myself into the son my father had openly said he’d have preferred.… I remember how mentally sexless I felt in youth…. As I didn’t have a realistic possibility of becoming a man back in the 1980s, it had to be books and music that got me through both my mental health issues and the sexualised scrutiny and judgement that sets so many girls to war against their bodies in their teens. Fortunately for me, I found my own sense of otherness, and my ambivalence about being a woman, reflected in the work of female writers and musicians who reassured me that, in spite of everything a sexist world tries to throw at the female-bodied, it’s fine not to feel pink, frilly and compliant inside your own head; it’s OK to feel confused, dark, both sexual and non-sexual, unsure of what or who you are.”

Based on that passage, that author sounds either nonbinary or genderfluid to me. Like Matthews’ fictional character, she also supports (some) trans retcons:

“I know transition will be a solution for some gender dysphoric people … I happen to know a self-described transsexual woman who’s older than I am and wonderful. Although she’s open about her past as a gay man, I’ve always found it hard to think of her as anything other than a woman, and I believe (and certainly hope) she’s completely happy to have transitioned.”

But the author rejects trans sequels, especially ones in response to misogyny, noting that we’re “living through the most misogynistic period I’ve experienced,” and homophobia, aligning herself with “the mother of a gay child who was afraid their child wanted to transition to escape homophobic bullying,” and calling attention to trans men who “say they decided to transition after realising they were same-sex attracted, and that transitioning was partly driven by homophobia, either in society or in their families.”

The author rejects a person sequeling a female gender identity to escape discrimination.

Why?

Maybe she’s just patronizing: I know what’s best for you.

Maybe, like Matthews’s fictional character, because the author wasn’t able to sequel her own female gender identity, no one else should be able to either: What didn’t kill me made me stronger, and therefore it should be required for you.

Maybe there’s a feeling of betrayal in there too: you sequeling your female gender identity hurts me.

And maybe a panicked need for allies: you sequeling your female gender identity hurts everyone with female gender identities.

Matthews of course is setting up a different kind of sequel: the growth arc. Her fictional character is called “judgemental” by her friend, and she later narrates: “Perhaps I was a man all along, and this was the heart of my problem, my inability to be soft like a fruit, open like a flower.” When her closest friend announces she wants to be “free from gender,” that they are now genderfluid, she responds: “Listen, I may not understand everything to do with this– But like, respect is free. Costs me nothing to call you what you want to be called, like maybe I’ll forget, but I love you.” And then she calls them “they” for the rest of the novel. Does the same for Emily too.

If that other author is climbing her own character arc, she’s still in the disturbingly steep foothills of change.

Matthews’ fictional character goes unnamed for much of the novel.

Any guesses about the other author’s name?

April 29, 2024

Paper is Skin

In an interview with Hilary Chute, Allison Bechdel said “paper is skin” (Chute 2011: 112). Since she also said ink is blood, the metaphor doesn’t seem to be intended racially. Bechdel’s not saying white paper is White skin. However, her approach to color in her 2021 The Secret to Superhuman Strength both literalizes the “paper is skin” metaphor and illustrates its racial complexities.

Bechdel’s first memoir, Fun Home, includes shades of blue added to her black line art, creating gradations without denoting hues. The effect is similar to grayscale art, since everything colored blue isn’t meant to be actually blue in the story world.

Her second memoir, Are You My Mother?, combines grayscale and shades of red, again leaving actual hues unknown, while emphasizing thematic connotations: the previous blues for her father are replaced by pinks in her mother’s story.

For her third memoir, Holly Rae Taylor, Bechdel’s personal and artistic partner, painted Bechdel’s line art in a range of mostly primary colors that appear to directly represent the colors of their subject: Bechdel’s red shirt, for example, is both discursively and diegetically red.

The same is not true of skin.

Taylor uses a light blue for facial shadows but otherwise leaves skin areas the unmarked color of paper. Because she applies the norm to all characters regardless of race, page whiteness represents all skin colors. While that’s a norm in black-and-white comics, the approach is unusual in color art, giving page whiteness the ability to represent multiple diegetic colors only when representing skin. Other instances of unmarked negative spaces within images represent only white or lightly colored objects.

Bechdel’s cast of characters is predominantly White, so the representational tension is rare and occurs only when depicting potentially dark-skinned characters.

At roughly the midpoint of the narrative, Bechdel’s narrator describes feeling “a hand grope my butt” in a subway entrance, later describing the “young man” as someone who “had clearly been [fighting] all of his life” after he returns Bechdel’s ineffective punch with a literally colorful “SOCK!” (109-110).

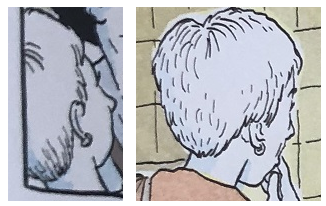

Setting aside the potentially racialized assumption about a life of violence, the two-page sequence includes six recurrent images of the “young man” whose features contrast Bechdel’s style of representation for herself and Taylor.

Where Bechdel typically draws mouths as single straight lines and sometimes dots, the man’s mouth consists of three lines, each conveying more realistic shapes of his lips. Rather than a variation on Bechdel’s simplified two-sided nose triangle, the curving lines of his nose also suggest nostrils, and his hair is tightly curling black lines in contrast to Bechdel’s solid black hair shape. Bechdel represents his Afrocentric features naturalistically and so in visual opposition to her slightly more simplified and exaggerated cartoon style.

That contrast is contradicted by the figure’s non-naturalistically paper-white skin, which viewers presumably interpret as representing a different color than Bechdel’s and Taylor’s paper-white skin.

Before his entrance, page whiteness could be understood to represent only light colors, including not only White skin but Taylor’s indeterminate but apparently light hair color, which, like her skin, she leaves uncolored.

The rule is violated during the two-page scene if his skin is understood to be some darker shade of brown, which Bechdel’s rendering of Black phenotype suggests. Understanding his skin to be a beige similar to Bechdel’s disrupts that phenotype, making his character not only racially ambiguous but contradictory.

Whether or not Bechdel and Taylor intend that effect, it’s produced by the white paper.

After drafting this post as a chapter subsection for my work-in-progress, The Color of Paper, I noticed a further complication of the color art:

Taylor visually casts the “young man” as the protagonist.

For almost all other scenes, Taylor paints Bechdel in red and blue, beginning with the opening pages. But in the subway sequence, Bechdel enters in a very light pink, and the “young man” in her standard colors.

Keeping in mind that the memoir is titled The Secret to Superhuman Strength, this is standard superhero differentiation. Stan Goldberg, Marvel’s primary colorist during the 1960s, told an interviewer:

“I always used red, yellow, and blue for the super-heroes. Green, browns, shades of red, and purples were the colors I saved for the villains. It was a formula, and it worked. The colors I picked for the villains made for a better contrast with the heroes. I certainly didn’t want to use the same colors for the villains that I used for the heroes, because when they came in contact with each other, it’d have been harder to visually separate them” (16-17).

Taylor doesn’t paint Bechdel as a green or purple villain, but her colors do disrupt the usual dichotomies during the center scene of the memoir. The literally white-skinned Black man who groped and then punched Bechdel’s White and literally white-skinned character is visually separated by the same Superman-evoking red-and-blue color design previously assigned only to Bechdel.

April 22, 2024

Retconning Law

I spent seven hours in England earlier this month, zooming to the “Literatures and Laws Online Symposium” at Bournemouth University. I had the pleasure of presenting an extremely condensed chapter from Nat Goldberg’s and my forthcoming book, Revising Reality. Fifteen minutes is tight, but I covered the basics of how the term “retcon” has recently entered the U.S. legal system and how the concept of retconning has always existed in it. In other words, “Rectonning Law” retcons retconning into law.

Instead of writing my talk, I’m uploading my slides — which I think is the same thing. To me, the challenge of presentation slides is streamlining them to the sweet spot of succinct and sufficient: a viewer should almost be able to follow the whole argument without the distraction of my yammering voice. Almost. In this case, let me explain the color coding: retcons are in green, and rejects (of retcons) are in red. Sequels are also in red because retcons are often rejected because they’re read as sequels.

The virtual Q&A is ongoing, so contact me anytime.

Any questions? Email or read the long version, AKA “Chapter 5,” in Revising Reality, due out next month.

April 15, 2024

Blue May No Longer Be the Warmest Color

I checked my old syllabi, and Jul Maroh’s Blue is the Warmest Color is tied for my most-taught graphic narrative. Beautiful Darkness will likely move to a lone number one slot next time I teach Intro to Graphic Novels though, because my current class has convinced me to retire Blue is the Warmest Color.

First, a quick author update:

The novel was first published in 2010, and Maroh revealed that they are non-binary in (I think) 2022. Their various publishers are still catching up — most distressingly their English-language publisher, which means Maroh is still being dead-named on some of their covers.

If you’re curious, you can track the evolution of their first name from its original appearance, to its contracted abbreviation at their former blog, to its current non-abbreviated “Jul.”

The author’s gender identity doesn’t excuse the catastrophe of the 2013 film adaptation by Abdellatif Kechiche.

I show the trailer in class, while discussing Laura Mulvey’s 1975 classic essay on the male gaze.

I share Maroh’s critique too:

“It appears to me this was what was missing on the set: lesbians. I don’t know the sources of information for the director and the actresses (who are all straight, unless proven otherwise) and I was never consulted upstream. Maybe there was someone there to awkwardly imitate the possible positions with their hands, and/or to show them some porn of so-called “lesbians” (unfortunately it’s hardly ever actually for a lesbian audience). Because — except for a few passages — this is all that it brings to my mind: a brutal and surgical display, exuberant and cold, of so-called lesbian sex, which turned into porn, and me feel very ill at ease.”

I also share Maroh’s thoughts about the novel’s intended audience:

“I didn’t make a book in order to preach to the choir, nor only for lesbians. Since the beginning my wish was to catch the attention of those who:

“–had no clue

“–had the wrong picture, based on false ideas

“–hated me/us”

And that’s when class discussion moved in an unexpected direction.

The room coalesced around three central critiques.

First, the age difference between the characters begins their relationship with an imbalanced power dynamic. When they meet, Clementine is 15, and Emma is in college. They have sex for the first time when Clem is 17. Someone googled “age of consent in France” (it’s 15), but that defense felt (literally) legalistic.

I thought discussion of the second half of the novel would soften the criticism. I was wrong. Yes, they’re older (Clem is 30 by the end), but the room felt the relationship remained fundamentally co-dependent. They were described as addicts, and when Clem is without Emma, she becomes literally addicted to a (substitute) drug.

Third critique: the relationship seems much more about physical sex rather than emotional depth. Given the “explicit sex” content warning I put on my syllabus, it’s hard to argue against that.

I suggested that all of the critiques may have more to do with rejecting romance genre tropes (love at first sight, I can’t live without you, etc.), but that only reinforces the fact that Maroh employs them. I also pointed out that a lot has changed since 2010. But, again, that only reinforces the fact that it’s 2024.

So now I have to ask myself: Why have I taught the novel so many times?

It may sound superficial, but I love its formal approach to layout. Not just in the abstract, but how Maroh employs layout effects to express her characters’ emotional lives, complexly merging form and content.

Also, it’s a lesbian romance.

The combination seemed ideal to me. Still does. Though now, yes, I also fully acknowledge that imbalanced power dynamics, emotional co-dependence, and an overemphasis on sex are all traits of an unhealthy relationship. They always were, but I previously ignored them as less significant genre qualities, content to focus instead on how the novel flouted the primary romance trope of heterosexuality.

After drafting this post, I reported the class discussion to one of my English department colleagues and visiting novelist Sarah Thankam Matthews (whose All This Could Be Different I’m dying to read as soon as I clear my digital desk of final papers and exams, but whose short story “Rubberdust” you should read right now). They were both describing similar class discussions, alarmed by what they called the legalistic reaction of students objecting to the sexual behavior of fictional characters on ethical grounds. I would need more data to speculate on how widespread the trend is or isn’t, but it sounded like they’d both been eavesdropping on my comics class.

But one more unexpected turn: on the last day of class I asked the room which novels they recommend I keep or replace, and several students (including two who were among the most adamant in their critiques) lobbied to keep Blue is the Warmest Color on my future syllabi. Yes, the relationship is problematic, but they found it engaging despite — and possibly because of — those problems. In short, they really enjoyed analyzing the novel so thoroughly, something its flaws encouraged.

Meanwhile, their top two must-keeps were happily the same as mine:

April 8, 2024

The Expanding Speech Balloon

First a quiz.

Each of the following images includes one or more speech balloons. What do the images mean?

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Before I give the answers, here’s a micro-history of the speech balloon.

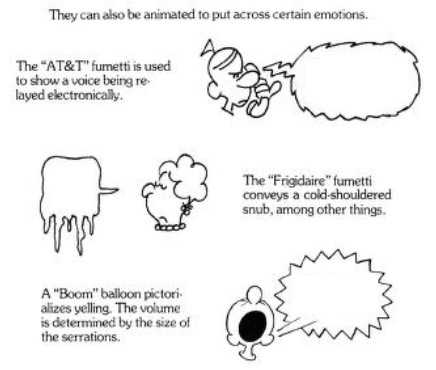

In his unexpectedly canonical The Lexicon of Comicana (1980), cartoonist Mort Walker categorizes speech balloons as a kind of “fumetti” (Italian for “clouds” or “smoke” though Walker says “balloon”): “the things that float above a character’s head and contain what he’s thinking or saying.”

But the convention dates back at least to medieval manuscripts, AKA “speech scrolls.”

Standard-looking speech balloons predate the comics medium too, especially during the nineteenth century. Here’s an 1860 editorial cartoon featuring Abraham Lincoln:

The speech balloon took hold in the comics medium as the comics medium took hold in the 1890s. Richard Outcault’s Yellow Kid provides a transitional example, with the Kid’s shirt functioning as a speech container too:

The convention was so prevalent in 20th-century comics that in 2000 philosopher David Carrier used it as the key to his definition: “a narrative sequence with speech balloons.”

Carrier is wrong (some comics don’t include speech balloons), but the convention remains prevalent in comics and — the point of this blog post — increasingly outside of them.

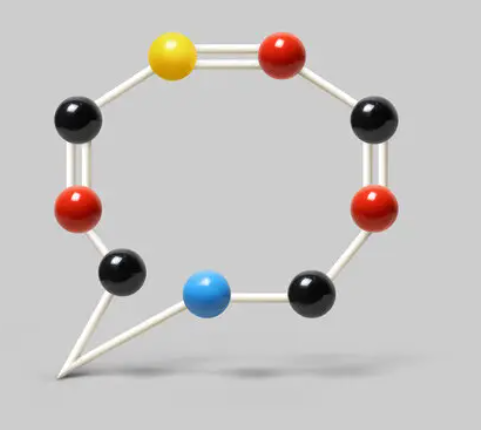

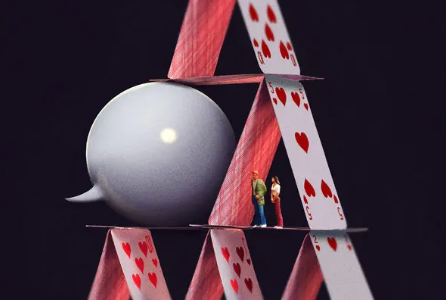

And not just speech balloons, but their paradoxical sibling: wordless speech balloons.

Based on Walker’s definition, a wordless speech balloon should communicate only one thing: that a character is speaking. But Walker also illustrates how the lines that construct the balloon convey additional information.

Remove the words, and the images still convey much of the same meanings:

All of the examples from the opening quiz are wordless too, but their meanings are more complex. Each also illustrated an article from the New York Times.

1.

Gabriel Carr’s illustration for Art Cullen’s “We Were Friends for Years. Trump Tore Us Apart.”

2.

Nathalie Lees’ illustration for Catherine Pearson’s “It’s Tough to Talk to Your Partner About Sex. Here’s How to Start.”

3.

Doug Chayka’s illustration for Carl Zimmer’s “A.I. is Learning What It Means to Be Alive.”

4.

Brian Rea’s illustration for Courtenay Hameister’s “We Were the ‘Fat Couple’?“

5.

Nicolas Ortega’s illustration for Jancee Dunn’s “8 Things You Should Never Say to Your Partner.”

6.

Nicolas Ortega’s illustration for Jancee Dunn’s “How to Bargian Like a Kidnap Negotiator.”

While each image illustrates its article’s core idea well, all six speech balloons share two other qualities: they were all published between December 2023 and March 2024, and they’re all objectified.

I borrow the term from comics philosopher Roy T. Cook’s 2012 essay “Why Comics Are Not Films: Metacomics and Medium-Specific Conventions”:

“A balloon is objectified when it is placed in such a way as to force the reader to interpret the balloon as part of the physical universe inhabited by the characters and the objects depicted …”

I’m leaving out Cook’s final phrase, “in a particular panel,” because the above examples are from the New York Times, which is not a comic, and so the objectified balloons do not appear in comics panels.

The fact is significant because Cook also argues that speech balloons, when they appear in a medium other than comics (such as film), “are a non-standard feature, typically functioning as an explicit reference to comics.”

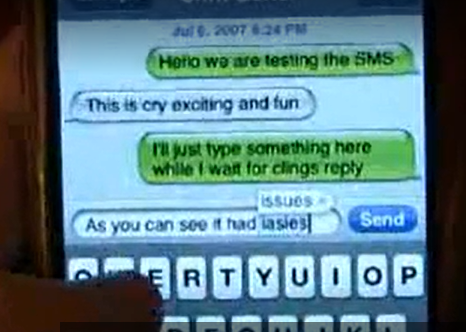

That was twelve years ago. Based on the six examples appearing within a very recent four-month period, the speech balloon may no longer be primarily identified as a comics convention.

Speech balloons may just be speech balloons.

The best evidence for that claim has been around since 2007 when Apple released the first iPhone. The designers used speech balloons for texting.

They added thought-balloon reactions in 2016.

Perhaps most definitively, the identifying symbol for texting is a wordless speech balloon:

Though it might be debatable whether a text screen is in the comics form, your phone is definitely not in the comics medium. I also seriously doubt you think at all about comics while texting.

That’s because speech balloons have expanded beyond them.

After drafting the above, the New York Times ran another more complex example. Erik Carter’s illustration for A. O. Scott’s “Like My Book Title? Thanks, I Borrowed It” includes animation as the three-panel row spins bodies behind Walt Whitman’s head and speech balloon.

Here are three snips, the middle one caught mid-motion:

Though in this case we can restore Cook’s phrase “in a particular panel,” I don’t think Carter’s panels evoke comics panels, which conventionally include a vertical gutter between them. The animation further reduces a sense of the image “functioning as an explicit reference to comics.” Though the balloons aren’t objectified with the same three-dimensional techniques as the first six examples, the animation does create the illusion of two surfaces, with the heads and speech balloons placed “above” the moving background, which means the overall image still creates a three-dimensional effect.

Now I need to post this before the speech balloon expands again.

April 1, 2024

Resurrecting the Zombie Life

My zombies are back and coming to campus.

After a pandemic-related online preview in 2020, the play world-premiered at Richmond’s Firehouse Theatre in 2021, was restaged in Williamsburg with a new cast in 2023, and now appears in Lexington on April 6 for the first time before returning to Williamsburg for a performance the following weekend.

I loved the first performance (and wrote about it here and here), but I love the current production even more — in part because we condensed the zombies from a horde of five to a cohesive team of four, and this round we really figured out who the therapist leading them is all about. The action scenes are tighter too:

A local reporter asked me some questions about the show, which I’ll share:

What is The Zombie Life about?A therapist is presenting a series of seminars encouraging people to become zombies because it’s the best way to avoid the emotional pain of living. As evidence, he tours with a team of trained zombies that he enables to speak and explain to the audience their reasons for converting. Although disturbingly well-intentioned, it’s all a terrible idea – which becomes increasingly obvious as an unplanned convert struggles but fails to adjust to the zombie life on stage during the seminar.

Why zombies?The play began as a short story titled “The Zombie Monologues” and consisted of a dozen or so long paragraphs, each from the perspective of a zombie. Zombies are nominally alive but mindless and emotionless, which I imagined could feel like a kind of reprieve from the hard work of living. The point though was that each explanation was gut-wrenchingly wrong, revealing the necessity of struggling as the only way to find any meaning.

I began turning that disconnected series of textual monologues into a play with my sister, who is a dancer, dance instructor, choreographer, and now director. We first had to figure out why the free-floating monologues existed, which made us invent the new character of the tragically wrong-minded therapist. And the necessity of plot made us create the audience member who unexpectedly steps forward and converts at the start of the play.

At a personal level, our mother had recently died of Alzheimer’s. I’d been visiting her Williamsburg nursing home almost monthly for several years, which also kept me in touch with Joan. I was worried that we would drift apart without the struggles of taking care of our fading mother keeping us connected. A play collaboration was my solution. Probably any play would have been fine, but maybe it’s more than coincidence that we settled on one about grief.

It’s being performed at a college — where a lot of people struggle with their mental health, especially after the pandemic. How might your play resonate with students?My anxiety is that the therapist’s surface message – which is essentially an endorsement of suicide – could be mistaken as sincere and actually convincing. The goal is overwhelmingly the opposite. Each zombie has made the most horrific and irreversible mistake possible, and though they think their reasons justify their giving up, the point is to reveal the absolute need of struggling despite all the pain it requires. It’s an anti-suicide message presented as a horrifyingly flawed pro-suicide message.

What do you hope the audience will take away?I want them to feel uncomfortable while watching the play. I want that discomfort to release itself in laughter, tears, and occasional flinching while in the theater. Afterward, I hope the discomfort lingers and haunts in productive ways. Maybe they will keep thinking about the characters’ rationalizations. Or maybe just the emotions of the experience will continue to resonate as they reenter their lives just a little less zombie-like.

I wasn’t asked, but I’m also really happy about my redesign of the poster art:

My original version was fun, but also cluttered and less clear in tone:

Apparently, the more you work at something the better it gets. And that’s not a bad description of our zombies either. Unlike TV zombies (though, yes, I’m somehow still watching The Walking Dead spin-offs), our zombies get a second chance at life.

March 25, 2024

Fear of a Black Phenotype

This image makes me a little nervous. I created it through an idiosyncratic digital process, where the final image is largely unrelated to the initiating set of marks, and no clear authorial intention controls the outcome. In other words:

I didn’t set out to draw a Black woman.

That I think (and think others will think) it’s a drawing of a Black woman makes me a little nervous — because so much of the history of white artists depicting Black people is horrific, and the image places me in that history.

But if my authorial intention doesn’t make it a drawing of a Black woman, what, if anything, does?

I think (and I think others will think) it resembles a Black woman. Resemblances is distinct from racist caricature, but it’s still problematic since the image isn’t of and so doesn’t resemble any one specific person who happens to be Black. It’s an invented image, and so for it to resemble “a” Black woman, Black women would have to have some common appearance that the image somehow imitates.

Setting aside the considerable issues of gender and focusing just on race, the image would have to resemble a Black phenotype.

In 2022, I received a reader’s report for an essay submission, “Reading Race in the Comics Medium,” that I’ve since revised and was just published in Closure #10. The reader reported:

“You must take into account how logics of race inform linguistic constructions, while also bearing in mind that racial phenotype is a very, very real thing. You seem to express tacit reservations about its existence … It is a very well-established and researched fact that Black phenotype is real, and consequential – even deadly – in white supremacist systems.”

I think the reader misread me. (The essay draft discussed, among other things, how men with Black phenotype receive harsher sentences and the specific attributes of noses drawn to represent Black faces.) But it also seems likely to me that I indirectly and unknowingly communicated, not a tacit reservation about the existence of Black phenotype, but a discomfort with talking about it. In other words:

Black phenotype makes me a little nervous.

And that nervousness apparently occurs whether I’m addressing the subject in words or image.

Being a little nervous isn’t a problem, especially if the nervousness results in my being more careful. As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, I’m working on a book manuscript tentatively titled “The Color of Paper: Representing Race in the Comics Medium.” Tacit reservations or not, I’m drafting a section about Black phenotype. It helps that I’ve been exchanging work with Jo Davis-McElligatt.

Here’s a passage I’ve been working on:

In her essay “Black Looking and Looking Black: African American Cartoon Aesthetics,” Joanna Davis-McElligatt uses the term “Black phenotype” three times. Though the phrase may communicate an immediate surface meaning (brown skin, black tightly curled hair, lips larger and nostrils wider than typical of non-Black people), no phenotype can simply be “Black” because phenotypes do not match racial categories. “Phenotypic traits have been used for centuries for the purpose of racial classification,” explains John H. Relethford, but “the boundaries in global variation are not abrupt and do not fit a strict view of the race concept; the number of races and the cutoffs used to define them are arbitrary. The race concept is at best a crude first-order approximation to the geographically structured phenotypic variation in the human species” (). As a result of that crudeness, the term’s adjective-noun combination is oxymoronic. “Phenotype” references physical qualities and “Black” references a socially constructed category, resulting in the impossibility of socially constructed physical qualities. To avoid that extrinsic-intrinsic contradiction, “Black phenotype” could mean physical qualities belonging to members of a socially constructed racial group. While technically accurate (group members necessarily have physical qualities), the phrase implies a unique subset of physical qualities that is consistent across members and therefore ultimately defining of the group – which then redefines “Black” as that set of physical traits and redefines “race” as not a social construction. To avoid that essentialist definition, I understand “phenotype” to mean: physical qualities perceived as belonging to members of a socially constructed racial group. The perception may be by members, non-members, both, or some combination, and the perception is always socially constructed. Since an individual whose appearance does not match a Black phenotype may still be Black, racial constructions also extend beyond phenotypes to include socially constructed perceptions of other qualities (such as speech, clothing, names, and social environment). Davis-McElligatt therefore references an artist’s rendering of a character’s “Black phenotype—his Black curly hair, dark eyes, rich brown skin, and wide nose and lips” and lists such “portrayals of Black phenotype” as distinct from both “Black expressive culture” and “the conventions of Black being,” as well as distinguishing “Black phenotype, or looking Black” from “Black behavior, or acting Black.”

This next bit may end up on the cutting floor, but it still seemed worth drafting:

My white phenotype includes beige skin, blue eyes, brown hair, a thinner than average nostril width, and smaller than average lip size. Distinguishing qualities of my white expressive culture, conventions of white being, and white behavior are too numerous and complex to easily list – though all align with my phenotype, and so a visual depiction of my phenotype may be sufficient to evoke them.

Weaving back to my digital art, I created this last image shortly after creating the image at the top of this post, using the same emergent process I described there.

I think it’s a drawing of a white person.

Is it?

Chris Gavaler's Blog

- Chris Gavaler's profile

- 3 followers