Transgender Sequels vs. Transgender Retcons

People don’t like retroactivity. That’s one of my main discoveries from co-writing my new book, Revising Reality, an application of fiction revision types (sequels, reboots, retcons) to real-world narratives (history, science, law, memory). A late chapter analyzes the personal histories of name changes, including trans names. And that’s the one place we found a preference for retroactive revision.

I’m reading Sarah Thankam Matthews’ excellent All This Could Be Different, and came across a passage about a nonbinary character. The novel was published in 2022 but is set during the Obama years, back when trans was a seemingly new idea. Two friends are talking about a girl one of them likes:

“Sorry, not girl, Emily uses they pronouns.”

“They pronouns? What in the world. Is this person a hermaphrodite?”

“You know, like a trans person. Well, nonbinary gender. Which is a subset, I think, of being transgender. Or maybe a superset. I’m not sure.”

“Oh come on.”

“What”?

“I get, I really get like, if you want to transition to living your truth as a woman or a man if you were born the wrong thing. I support that completely. Anything beyond that is elitist leftist American nonsense, honestly.”

The transphobic character divides trans people into two categories: “born the wrong thing” and “nonsense.”

She supports the first and ridicules the second. Why?

To answer, first analyze what kind of revision each performs.

If you’re transitioning to your true gender because you were “born the wrong thing,” meaning your body does not match your gender identity, then transitioning reveals who you actually are and always were from birth. That’s a retcon. Short for retroactive continuity. A new revelation reinterprets a past impression as false. Others (including perhaps yourself at some moments) thought you were one gender based on your appearance, but now that past impression is revealed to have been wrong.

The term comes from superhero comics, where characters routinely die and come back to life. Except they don’t. Because that would be a sequel. If Captain America was dead and later he was alive again, that’s a sequence of events. A retcon instead reveals that Captain was never dead, we just thought he was. His apparent death is retroactively erased. A trans person’s previous apparent gender is retconned in a similar sense. They never were that gender, you just thought they were.

Matthews’ possibly-not-transphobic character has no problem with that. She supports trans retcons. It’s trans sequels that upset her, reporting in hindsight how she was “hissing like a goose, surprised by my own anger.” She continues:

“This shit is hard for everyone! Do people think so-called cis people don’t, or haven’t, struggled with this shit? Feel fucking weird in their own bodies? … I spent all my teens wishing I could slice my breasts off, have a flat and smooth body. I cut up my bras with nail scissors. Got thrashed for it. Does that entitle me to a they? Can I opt out of gender now?”

The answer (in my opinion) is yes. That’s because, unlike the fictional character, I also support trans sequels. If the character, who is a queer woman, decided to “opt out of gender,” that would be a new event in a sequence of events. Previously she was a woman and now they would be nonbinary. No retroactive claim involved. And that apparently is what angers her.

The underlying logic is that gender identity is always fixed from birth, and so it can be retconned if that identity is bodily mismatched, but it can’t be sequeled. You are whatever you are, no opting out permitted. No options period. You decide whether to reveal your gender, but your gender doesn’t change as a result. That’s the point of retconning. And since the character had to persevere as a woman, Emily and all other people assigned female at birth have to persevere too. No sequels allowed.

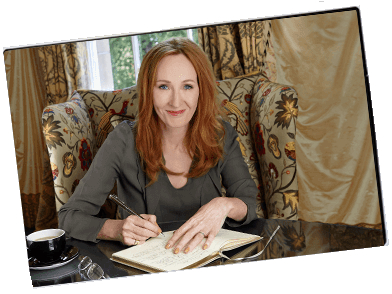

Matthews’ character is fictional, and so no actual gender identity is involved, but here’s an excerpt from another author’s personal written in 2020 that expresses related attitudes:

“The writings of young trans men reveal a group of notably sensitive and clever people. The more of their accounts of gender dysphoria I’ve read, with their insightful descriptions of anxiety, dissociation, eating disorders, self-harm and self-hatred, the more I’ve wondered whether, if I’d been born 30 years later, I too might have tried to transition. The allure of escaping womanhood would have been huge.… I believe I could have been persuaded to turn myself into the son my father had openly said he’d have preferred.… I remember how mentally sexless I felt in youth…. As I didn’t have a realistic possibility of becoming a man back in the 1980s, it had to be books and music that got me through both my mental health issues and the sexualised scrutiny and judgement that sets so many girls to war against their bodies in their teens. Fortunately for me, I found my own sense of otherness, and my ambivalence about being a woman, reflected in the work of female writers and musicians who reassured me that, in spite of everything a sexist world tries to throw at the female-bodied, it’s fine not to feel pink, frilly and compliant inside your own head; it’s OK to feel confused, dark, both sexual and non-sexual, unsure of what or who you are.”

Based on that passage, that author sounds either nonbinary or genderfluid to me. Like Matthews’ fictional character, she also supports (some) trans retcons:

“I know transition will be a solution for some gender dysphoric people … I happen to know a self-described transsexual woman who’s older than I am and wonderful. Although she’s open about her past as a gay man, I’ve always found it hard to think of her as anything other than a woman, and I believe (and certainly hope) she’s completely happy to have transitioned.”

But the author rejects trans sequels, especially ones in response to misogyny, noting that we’re “living through the most misogynistic period I’ve experienced,” and homophobia, aligning herself with “the mother of a gay child who was afraid their child wanted to transition to escape homophobic bullying,” and calling attention to trans men who “say they decided to transition after realising they were same-sex attracted, and that transitioning was partly driven by homophobia, either in society or in their families.”

The author rejects a person sequeling a female gender identity to escape discrimination.

Why?

Maybe she’s just patronizing: I know what’s best for you.

Maybe, like Matthews’s fictional character, because the author wasn’t able to sequel her own female gender identity, no one else should be able to either: What didn’t kill me made me stronger, and therefore it should be required for you.

Maybe there’s a feeling of betrayal in there too: you sequeling your female gender identity hurts me.

And maybe a panicked need for allies: you sequeling your female gender identity hurts everyone with female gender identities.

Matthews of course is setting up a different kind of sequel: the growth arc. Her fictional character is called “judgemental” by her friend, and she later narrates: “Perhaps I was a man all along, and this was the heart of my problem, my inability to be soft like a fruit, open like a flower.” When her closest friend announces she wants to be “free from gender,” that they are now genderfluid, she responds: “Listen, I may not understand everything to do with this– But like, respect is free. Costs me nothing to call you what you want to be called, like maybe I’ll forget, but I love you.” And then she calls them “they” for the rest of the novel. Does the same for Emily too.

If that other author is climbing her own character arc, she’s still in the disturbingly steep foothills of change.

Matthews’ fictional character goes unnamed for much of the novel.

Any guesses about the other author’s name?

Chris Gavaler's Blog

- Chris Gavaler's profile

- 3 followers