Chris Gavaler's Blog, page 4

March 3, 2025

The Fascist Superhero

My article “The Rise and Fall of Fascist Superheroes” was published in the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics in November 2015 — a year before Donald Trump was first elected. I’ve blogged about Trump’s relation to superhero tropes since (rereading what I wrote four months before the 2016 election is unnerving), but most superhero fans aren’t aware of the fascist origins of the genre. The article evolved into “The Fascist Superhero,” a pivotal chapter in my 2018 Superhero Comics. Because it sadly suits our political moment, I’m sharing an excerpt from the introduction here.

Summarizing the character type from the vantage of the twenty-first century, Andrew Bolton describes superheroes as upholders of “American utopianism as expressed in the Declaration of Independence and Constitution” (47), but viewed in their original context, they also express the paradox that such utopianism can only be defended through the anti-democratic means of vigilantism and authoritarian violence. Comic book superheroes were conceived during the threat of fascism, reached their highest popularity with the expansion of a fascist-fighting war, and began to wane not at the close of that war but at the earliest signs of a still-distant victory.

Although fascism appears anathema to the popular understanding of superheroes, contemporary journalists have commented on the fascist aesthetics of the genre: in “The Real Problem With Superman’s New Writer Isn’t Bigotry, It’s Fascism,” The Atlantic’s Noah Berlatsky remarks that “superhero-as-oppressor is almost as much of a trope as superhero-as-savior”; “Superheroes,” writes Joe Queenan in The Guardian, “operate in a netherworld just this side of fascism”; and in his critique of The Dark Knight Rises, Andrew O’Herir declares that the character’s “universe is fascist,” arguing that the screenplay “pushes the Batman legend to its logical extreme,” a version of “the ideology that was bequeathed from Richard Wagner to Nietzsche to Adolf Hitler.”

Scholars have observed the character type’s fascist qualities for decades: Peter Coogan presented “F For Fascism: The Fascist Underpinnings of Superheroes” at the Midwest Popular Culture conference in 1989; Leonard Rifas, responding to a 1995 comics scholar survey, “suggested that the question asked by Time magazine in October 22, 1945, ‘Are [superhero] comics fascist?’ is due for reinterrogation” (Coogan 1995); Craig Fischer posed a similar question, can superhero comics “function as fascist propaganda?” (334), in 2003, the same year Scott Bukatman referred to superheroes as “innately fascist” (185); Geoff Klock explores “the degree to which superhero narratives boil down to a choice among various modes of fascism” (106); and as recently as 2014, Jose Alaniz described superheroism as “primary-color fascism” (9).

Such observations, however, typically treat fascism as a characteristic independent of historical fascism. Alaniz, for instance, responds to “the nature of violence in the genre as particularly reactive and reactionary” (9); Klock analyzes Alan Moore’s 1999 series Tom Strong; Bukatman looks at the contemporary character type as “authority and order incarnate” (185); and Fischer questions what effect comics could have on “kids from disenfranchised backgrounds” (334). Coogan explains the correlation between fascism and superheroism as expressions—one political, the other literary—of a shared central core, since both “mediate the same unreconcilables” for the “same audience” using “similar methods” and “similar if not identical justifications” (Coogan 1989). The focus is again on the current genre, not the circumstances of its development. Even O’Herir, despite a reference to Hitler, suggests that only now through Christopher Nolan has Batman reached his “logical extreme.” But if that fascist logic is embedded in the character type, and if the comic book genre was created and overwhelmingly popularized during a fascist crisis, then contemporary superheroes’ violent, nationalistic, anti-democratic, totalitarian heroism bears some relationship to historical fascism.

The ahistorical use of fascism as a generic term has also triggered scholarly backlash. Marco Arnaudo, for example, acknowledges that characteristics of superheroes’ “heroic code of ethics are also part of the fascist imaginary” but rejects “seeing such a sequence as necessarily and exclusively fascist” since then “all heroism is by definition fascist” (73). Arnoudo, like most other scholars, is not studying the genre’s historical roots, and his reasoning relies on a straw man of exclusivity and a slippery slope of generalized heroism. Similarly, for Jeffrey J. Kripal, “equating the Superman, much less the superhero, in toto with fascism” is “a half truth,” “a gross misrepresentation,” and even “a precise reversal of the truth”; and yet, while arguing that “the idea of the superman” has “no necessary connection to Nazism,” Kripal figures Superman as a “Future Human,” “a model for the future evolution of human nature” (74, 75), which was the precise aim of Nazi eugenics.

When historical fascism is mentioned, it is often presented in opposition to superheroism as the genre’s formative threat. For Christopher Murray, for example, the Depression and “the rise of Fascism” are why superheroes “struck a chord,” “demonstrating that, despite the hardships it faced, America” still had “the will to fight to protect freedom and justice” (10). Tom De Haven does briefly acknowledge that the “small-s superman” of Nietzsche was, among many other things, the stuff of “Nazi politics,” and so “the capital-S Superman was a product of that particular time and cultural tumult” (68), and Lance Eaton also notes that superheroes “were not understood as the nearly perfect moral characters that their creators slowly developed them into over time” and which gained popularity as the U.S. looked “towards Europe’s forthcoming war” (35). Lawrence and Jewett go further and identify the 1930s as “the axial decade for the formation of the American monomyth” in which “alien forces too powerful for democratic institutions to quell” require the rise of a violent, authoritarian hero, but they regard the period’s “unprecedented foreign threats to democratic societies” as merely “the background for the creative advance” and not its cause (36,132, 36). They also observe the “final extension of powers into the superheroic scale” with “a proliferation of superheroes . . . to complete the formation of the monomythic hero,” but they do not suggest why such an extension occurred at this particular historical moment nor do they analyze its social-political context to explain the completion (41, 43).

Analysis of the historical relationship between superheroes and fascism remains incomplete, but other scholars have focused on the comic book genre as a Jewish response to the period’s anti-Semitism abroad and at home. Danny Fingeroth asserts that “creation of a legion of special beings, self-appointed to protect the weak, innocent and victimized at a time when fascism was dominating the European continent from which the creators of the heroes hailed, seems like a task the Jews were uniquely positioned to take on” (17). To answer what lead him “into conceiving Superman in the early thirties,” Jerry Siegel’s 1975 response includes: “Hearing and reading of the oppression and slaughter of helpless, oppressed Jews in Nazi Germany” (“The Victimization” 8). Although Siegel’s explanation is partly anachronistic since he created the character before the Holocaust, Hitler’s government passed six anti-Jewish laws in 1933 when Siegel was beginning his collaboration with Joe Shuster.

To envision a figure capable of opposing the new Nazi regime, Siegel appropriated the central, anti-democratic symbol of eugenics. Sharing his name with his fascist-appropriated Nietzschean forebear, the comic book Superman may be analyzed as a reactionary fantasy figure who countered totalitarian might by paradoxically adopting it for opposite political purposes. Robert Weiner sees “irony” because Captain America and the Human Torch look like “the Master Aryan man of superior stature” (86), but the nature of the irony changes if superheroes are understood to intentionally reflect and co-opt their foes’ traits. John Moser, in his study of Nazis in Captain America Comics, asserts that Americans were “simultaneously repelled and fascinated by [the Nazis]; the ideas were too alien, of course, to be embraced by any significant portion of the population” (24). But with democracy under attack, a very large portion of comic book creators and buyers did embrace fascist-fighting heroes who were themselves fascist-like.

The relationship between Superman’s appeal and “our national aspirations of the moment” was argued in one of the first analyses of the genre. In 1940, psychiatrist and future Wonder Woman creator William Marston identifies two wish fulfillments behind “Superman and similar comics”:

to develop unbeatable national might, and to use this great power . . . to protect innocent, peace-loving people from destructive, ruthless evil. . . You don’t think for a moment that it is wrong to imagine the fulfillment of those two aspirations of the United States of America, do you? (Richards 22)

Marston, however, does not acknowledge the political complexities of wishing for the defeat of destructive might through an agent of destructive might—a continuing contradiction of the character type born during the fascist period. Other early 1940s writers— Brown, Vlamos, North, Doyle, Southard—link comics and fascism, a critique that even when cursory deepened the public impression of superheroes as unwholesome subject matter. After the fall of Germany, the threat of Communism did not maintain the figure’s popularity, and those few superheroes who survived the industry’s Wertham-led, anti-fascist purging in the mid-fifties no longer displayed anti-democratic, authoritative violence. The historical relationship between Golden Age heroes and fascism was further distanced in the early sixties when Silver Age creators reproduced the formulas apart from their original context. While superheroes are not exclusively a fascist phenomenon, and while their enduring popularity is a product of myriad factors, their fascist origins remain embedded in the genre and continue to influence the hero type.

February 24, 2025

Made for Each Other

The poetry comic “Made for Each Other” was originally published on Split Lip in August 2019. I created the eight images, Lesley Wheeler wrote eight stanzas in response, and I devised a font to letter them. It’s our first poetry comic collaboration. We reversed the process for “Rhapsodomantic“: Lesley wrote the poem “Rhapsodomancy” (which appears in her new book Mycocosmic), and I illustrated twenty-two tarot cards in response. Our styles have evolved in the six years between, but I still recognize every Wheeler-esque turn-of-phrase, and I’m still inexplicably infatuated with the limitations of Word Paint. I look forward to our future collaborations, but those will have to wait until after her Mycocosmic book tour (which begins next week with a March 4th book launch party at Lexington’s Downtown Books).

Meanwhile, please enjoy “Made for Each Other”:

For Lesley’s latest, check out Mycocosmic:

February 17, 2025

Open Letter to my Republican Congressman

Dear Mr. Cline,

I’m glad to see that your official “Congressman Ben Cline” Facebook page features an image of the U.S. Constitution, with the phrase “We the People” displayed for its 15,000 followers.

However, despite your using the Constitution for a background image, your behavior since taking office in the new Congress does not show a concern for the content of that founding document.

Donald Trump has repeatedly undermined the Constitution’s authority since beginning his second term. I realize this puts you and many other House and Senate Republicans in a difficult position: do you place your partisan and ideological preferences first or your constitutional duties?

I will detail three examples.

As you of course know, the Constitution is explicit about presidential term limits: “No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice.”

And yet Donald Trump has repeatedly lied by implying that there is a question of interpretation. He has said:

“I’ve raised a lot of money for the next race that I assume I can’t use for myself, but I’m not 100 percent sure because I don’t know. I think I’m not allowed to run again. I’m not sure. Am I allowed to run again?”“They say I can’t run again; that’s the expression. Then somebody said, I don’t think you can. Oh.”“I suspect I won’t be running again unless you say, ‘He’s so good we’ve got to figure something else out.’”“We’ll negotiate, right? Because we’re probably — based on the way we were treated — we are probably entitled to another four after that.”Trump supporters such as Stephen Bannon have also contributed to the lie: “Since it doesn’t actually say consecutive. I don’t know, maybe we do it again in ’28?”

Your constituents, most especially those who support Donald Trump, need you as their representative to clarify that any talk of a third term is a clear and intolerable attack on the Constitution.

Donald Trump has also stated through his White House press secretary that: “This administration does not believe that birthright citizenship is constitutional.”

As you of course know, birthright citizenship is a part of the 14th Amendment, the 14 Amendment is a part of the Constitution, and the Constitution defines what is “constitutional.” It is impossible for any part of the Constitutional to be “unconstitutional.”

There is, again, no ambiguity. The authors of the birthright citizenship clause were explicit about its meaning when it was debated in the Senate in 1866. Those who opposed birthright citizenship voted against the amendment; those who supported birthright citizenship voted for the amendment. All agreed that the amendment contained birthright citizenship, and the Supreme Court further clarified in 1898 that birthright citizenship extends to “all children born here of resident aliens.”

And yet Donald Trump’s unconstitutional executive order states: “citizenship does not automatically extend.”

Your constituents, most especially those who support Donald Trump, need you as their representative to clarify that Donald Trump’s executive order violates the Constitution and therefore cannot be tolerated.

Donald Trump has also stopped funding federal programs that he dislikes.

As you of course know, the Constitution states that the president “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” As you also know, an “Appropriation” is a “law of Congress that provides an agency with budget authority to obligate and expend funds from the U.S. Treasury for specific purposes” (as stated on your U.S. House of Representatives website). Congress establishes the exact amount of money the agency is obligated to expend, and the executive branch must then carry out that law.

And yet the Trump administration has violated the Constitution by halting funds and closing agencies, while making the unconstitutional claim that “the Constitution gave Congress the power to set a ceiling on spending, but the president had the authority to spend less.”

The Trump administration is also violating a law passed in 1972 that created a legal process for a president to defer or rescind funds, which Congress can then override. The Supreme Court established that the law is constitutional when it ruled in 1975: “the sole issue before us is whether the 1972 Act permits the Administrator to allot … less than the entire amounts authorized to be appropriated. We hold that the Act does not permit such action.”

Your constituents, most especially those who support Donald Trump, need you as their representative to clarify that Donald is attacking the checks-and-balances system established by the Constitution to prevent a president from assuming undemocratic power.

I understand how hard this must be for someone who supports Donald Trump’s political agenda. But if you or anyone else wishes to change the two-term presidential limit, birthright citizenship, the ability of Congress to obligate spending, or anything else in the Constitution, then you have a single option: constitutional amendments. You of course know that. But many of your constituents likely do not, and the president’s statements are deepening their ignorance.

You and your Republican colleagues are at a defining crossroads: are you loyal to the U.S. Constitution or are you loyal to Donald Trump?

Sadly, you have already stated on Mr. Musk’s X: “Birthright citizenship is a magnet for abuse. That’s why I support President Trump’s executive order to narrow its definition.”

It is not possible to support the Constitution and an executive order that a court has already ruled is “blatantly unconstitutional.”

If your Facebook page’s “We the People” banner is only a colorful graphic to you, please have the decency to remove it.

Sincerely,

Chris Gavaler

February 10, 2025

Zoe Thorogood and the Two-World Paradoxes of Graphic Memoir

First, a thank you to John Cunnally for inviting me to submit a paper proposal to his College Art Association Conference panel, “In Memoriam Trina Robbins: New Research in the History of Women Cartoonists,” which is scheduled Saturday, February 15, 11:00 AM at New York Hilton Midtown. I admit the location was especially tempting, since it means I can visit my son (who lives in Brooklyn) while there, and visit my daughter (who lives in Philadelphia) on my way driving back and forth from Virginia.

I met Trina Robbins at a comics conference at the University of Florida back in 2013, and I have two of her books on my shelves next to my desk where I’m typing this, so I also admired the call for papers:

“With the passing of Trina Robbins (1938-2024) we have lost not only an outstanding artist, writer and editor of comic strips and comic books by, for, and about women, but a prolific historian and curator, author of a dozen books and catalogues on that subject, from Women and the Comics (1985) to Flapper Queens: Women Cartoonists of the Jazz Age (2020). Signing herself just “Trina,” Robbins was the most productive of the ardent feminists who contributed to the underground comix movement of the 1960s and 70s, and a founder of the comics anthology Wimmen’s Comix which ran from 1972-1992. In remembrance of comics creator and feminist historian Trina Robbins, this session focuses on new scholarship about the struggles and achievements (often forgotten or misunderstood) of women, past and present, in the creation and production of comic strips, comic books and graphic novels.”

I was most interested in the “present” part and thought Zoe Thorogood would be an especially strong comics creator worth celebrating. So I submitted this abstract:

“Zoe Thorogood’s 2023 “auto-bio-graphic novel” It’s Lonely at the Centre of the Earth not only documents Thorogood’s personal and professional struggles and achievements as an emerging comics artist and winner of the 2023 Eisner’s “Most Promising Newcomer” award, it provides fundamental lessons in the “metanarrative” qualities of graphic memoirs specifically and the comics form broadly. From her norm-breaking approach of drawing multiple interacting self-representations that reference disparate corners of visual media, to her use of her personal Instagram feed to present the novel as an evolving and interactive work-in-progress produced in real-time, Thorogood challenges the traditional confines of comics as a publishing medium and as a form of artistic self-expression. The presentation will draw from Michael Chaney’s Reading Lessons in Seeing to analyze Thorogood’s multiple “I-cons,” as well as comics scholarship on metafiction, including essays by Roy Cook, Thomas Inge, and Orion Kidder, to construct a unified theory of metacomics that Thorogood both illustrates and augments. In prose memoirs, meta elements are either absent or are invisibly redundant because of the nature of nonfiction understands author and reader to exist within the same world. Because comics are multimodal and memoirists represent themselves both verbally and visually, the form reveals gaps between actual authors and the partial fictions of their nominally nonfictional self-representations. While many comics artists obscure these conceptual gaps, Thorogood exploits them to unique effects that push the comics medium into new twenty-first century terrain.”

As seems inevitable, my paper has evolved a lot since that initial description, but it’s still in the same ballpark. I’m in the process of expanding it into a publishable essay, but I think the panel slides cover the core ideas. Or at least I think they could be interesting to look at even without my voice droning in the background.

February 3, 2025

Trans rights are a “resounding” legal fact

The U.S. legal system recognizes trans people by their gender identity.

In 2020, the Supreme Court established that employment discrimination against trans people has been illegal since the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Court refers to the trans woman in the lawsuit by her preferred name and pronoun, stating that the employer “fired Aimee Stephens, who presented as a male when she was hired, after she informed her employer that she planned to ‘to live and work full-time as a woman.’“ The Bostock v. Clayton County majority opinion was written by Trump-appointee Gorsuch and joined by Bush-appointee Roberts, as well as Breyer, Kagan, Sotomayor, and Ginsberg in the 6-3 decision.

In 2021, the Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal to Grimm v. Gloucester County School Board, causing the two lower court decisions in support of a transgender student to stand as undisputed law. The student, now an adult trans man, is referred to by his preferred name and pronouns in both decisions: “Gavin Grimm’s birth-assigned sex, or so-called ‘biological sex,’ is female, but his gender identity is male. Beginning at the end of his freshman year, Grimm changed his first name to Gavin and expressed his male identity in all aspects of his life.”

These two recent decisions establish the legal status of trans people in the U.S.

No executive order can change that.

Yet Donald Trump declared that his administration will “recognize women are biologically female, and men are biologically male,” repeating the “so-called” terms already dismissed by the courts.

Donald Trump also declared that it “is the policy of the United States to recognize two sexes, male and female. These sexes are not changeable and are grounded in fundamental and incontrovertible reality.”

But the Supreme Court already established the opposite: that sexes are changeable, and that individuals not only have the right to change their assigned sex, but employers are prohibited from discriminating against them if they do.

Donald Trump declared that “ideologues who deny the biological reality of sex” have “a corrosive impact not just on women but on the validity of the entire American system.”

But one of these ideologues is the first justice he appointed to the Supreme Court and another is the Court’s Chief Justice. They are renowned conservative judges appointed by conservative presidents and approved by conservative-majority Senates because of their conservative interpretation of the Constitution.

Donald Trump, like every president before him, is free to issue executive orders stating literally anything he likes. And though his anti-trans order does have a profoundly negative impact on many people in many places across the U.S., it does not and cannot change the standing of trans people in our legal system.

Justice Gorsuch stated: “Because discrimination on the basis of homosexuality or transgender status requires an employer to intentionally treat individual employees differently because of their sex, an employer who intentionally penalizes an employee for being homosexual or transgender also violates Title VII.”

Circuit Judge Floyd stated: “At the heart of this appeal is whether equal protection and Title IX can protect transgender students from school bathroom policies that prohibit them from affirming their gender. We join a growing consensus of courts in holding that the answer is resoundingly yes.”

That’s the law.

January 27, 2025

Coloring “Yes, Roya”

C. Spike Trotman founded Iron Circus Comics in 2007 to publish a print edition of her Templar, Arizona webcomic. For Yes, Roya (2016), Trotman collaborated with artist Emilee Denich, who described their creative process to me in an email:

“This was our first project together. I can’t quite remember where she found my work, but she emailed me and asked if I wanted to work on an erotic graphic novel together, and I said of course! […] Spike had a completed script ready to go for me. I would draw pages in batches of 10 […] by first reading over the script and thumbnailing the 10 pages out. That then would be used as a springboard to sketch the pencils on top. […] Every step of the way I’d send what I was doing to Spike and get approval, so it went something like thumbs – approval – pencils – approval – inks – approval and then finally to grey tones and letters for the final approval. […] this approval process was super easy – mostly she’d say “Wylie’s hair is too big and fluffy here” or something like that for fixing … “

Denich’s description matches the production process that has dominated the U.S. comic book industry for decades. Denich’s images began as black-and-white line art, and she later added digital grayscale, which colorist Kelly Fitzpatrick replaced in the 2021 Yes, Roya: Color Edition. Denich clarified in a later email exchange: “I had no involvement in the color version of Yes, Roya. The writer selected a colorist without my input or acknowledgement, and so I had no involvement in the process.”

The primary Yes, Roya characters—Roya, Wylie, and Joe—first appeared in color on the original 2016 cover created by artist kinomatika, apparently based on Denich’s designs but rendered in greater detail (including Wylie’s semi-subliminal penis-like nose).

Wylie’s foregrounded face consists of multiple light shades suggesting both physiognomy and lighting effects similar to Joe’s, and Roya’s face and bare arms are comprised primarily of a light brown and a medium brown for shadows. Denich’s interior grayscale art is likely unaffected by kinomatika’s color choices because her gray tones already imply skin shades. Kinomatika’s skin colors also roughly match Denich’s choices and could be derived from them.

In the interior art, Denich represents White skin as unmarked paper with light gray shading and Black skin as medium gray with dark gray shading. Both are primarily uniform with minimal overlap. Denich also assigns dark grays to Roya’s hair and clothes and lighter grays or page white to Wylie, Joe, and other White characters, with the exception of Wylie’s uniformly black hair.

Since Roya is the only Black character of a cast of six, the grayscale art always distinguishes her. Trotman also textually distinguishes her not only as the title character but as the sole character identified solely by first name, and narratively she is the dominant in her sexual relationships with both Joe (Ahlstrom) and Wylie (Kogan). The domination is also professional, as Roya explains to Wylie: “Jospeh isn’t my husband. We’ve never married. He lives with me in my house and takes credit for my work. He does this with my permission. This has made my success easier than it might be.” As a Black female artist in the 1960s, Roya secretly produces a nationally syndicated comic strip under Joe’s name in a racist and misogynistic industry.

Denich further distinguishes Roya with the least cartoonish features. She draws Wylie, the most cartoonish, with a two-sided triangle nose and a mouth that often reduces to a single Charlie-Brown-like line of varying emotion-conveying shapes. Roya’s features never distort in cartoonish exaggeration. Her parted mouth consists always of four lines, suggesting full lips. Her nose does not appear overtly Afrocentric, perhaps because Denich’s style reduces nostril widths generally. Her hair is not overtly Black-looking either, though the choice likely reflects the historical setting.

In her 2018 Twitter thread “Black Hair for Non-Black Artists: a Cheat Sheet,” Trotman assembles photo references “for folks who want to draw/model black characters in their work, but aren’t confident they won’t make simple, obvious mistakes w/r/t black hair,” noting that previously “the only acceptable hair was a slicked-to-the-skull pomade look or ‘conk’ (chemically straightened with lye) look for men. Women also straightened their hair with heat/chemicals, or wore wigs. My very proper grandmother REFUSED to go wigless, for ex.” Beneath the tweet Trotman includes a 1967 photograph of Aretha Franklin with a flipped bob. Denich renders Roya’s hair with a similar length and curve.

Because the hair style preceded the “rise of black pride/identity” which Trotman explains “has slowly but surely made ‘natural hair’ […] more acceptable and popular,” and because Denich renders other features racially ambiguously, viewers might not perceive Roya as Black if viewing only the pre-publication line art. The addition of gray tones is likely clarifying.

I included a grayscale and a color rendering of Roya in a quantitive study I conducted over the past two summers. (I blogged about an initial stage of the study here and here.) Despite the gray tones implying a non-White skin color, a significant minority of respondents across study groups still identified the figure as White. A near majority selected Black, and nearly a quarter selected Latine. Despite some ambiguity, most viewers understood Denich’s Roya to be non-White.

Fitzpatrick’s Roya is instead overwhelmingly Black. Adding color roughly doubled Black impressions, while drastically reducing Latine, and essentially eliminating White. The perceptual changes are likely due to more than Fitzpatrick’s addition of brown hues, which are presumably inferable from Denich’s art. Fitzpatrick also darkened Roya’s skin and hair relative to Denich’s gray tones and also to kinomatika’s original cover colors.

Roya appears to have shifted from Type IV on the Fitzpatrick scale to Type V. (The skin color scale was created by Thomas Fitzpatrick in 1975; I don’t know, but I’m guessing that colorist Kelly Fitzpatrick is not related.) Since Trotman’s script accentuates Roya as the lone Black female character dominating the two leading White male characters during a period of heightened White supremacy and misogyny, Fitzpatrick’s colors intensify that isolating effect visually.

Perceptions of White characters varied less. Supermajorities identified a grayscale image of Wylie as White, with Asian as the next popular selection at roughly a quarter.

Adding color produced no significant changes, with slightly larger supermajorities still identifying the figure as White, and slightly fewer as Asian. In Fitzpatrick’s version, Wylie’s skin appears to be Type I on the Fitzpatrick scale, which is darker than the page white of Denich’s original art. Fitzpatrick primarily reserves unmarked page areas for nondiegetic objects such as the interiors of speech balloons. Wylie’s shirt, which Denich shaded a medium gray to offset his literally white skin, is now a very light gray. Like Roya’s skin, Wylie’s is darker in the color version—though only because Fitzpatrick cannot shade White skin equivalently to page whiteness. Though diegetically the two versions of Wylie may be identical, discursively pale beige replaces page whiteness which cannot represent Whiteness in a color context. The White characters must assume actual colors rather than unmarked negative space.

Trotman concludes the novel with Wylie inventing a new comic strip character: a dark-skinned Wonder Woman standing over a White man bound in her lasso. Though the man does not resemble Wylie or Joe except racially, Denich (or diegetically Wylie) draws the female superhero with hair similar to Roya’s. Her facial features are more cartoonish, including a two-sided triangle nose like Wylie’s, and the gray tones of her skin are slightly lighter than those Denich assigns to Roya.

Similar to perceptions of Denich’s grayscale Roya, roughly a majority of respondents identified the figure as Black, with identifications of Latine and White averaging a little below a quarter each. Similar to perceptions of Fitzpatrick’s Roya, adding color moved the Wonder Woman figure from predominately Black to overwhelmingly Black, again drastically reducing Latine impression, and nearly eliminating White. Colors intensify the effects achieved by the gray tones—though here they also make the visual allusion more explicit, with the implied red, white, and blue of Wonder Woman’s costume now those actual colors.

January 20, 2025

Trump’s “Landslide” Didn’t Happen. Trump’s “Mandate” Doesn’t Exist.

President-elect Trump calls his 2024 win a “landslide” and the “Greatest Election in the History of our Country.” While it’s not clear what exactly “Greatest” might mean, the answer should be mathematical. Rank all the presidential elections by the winner’s vote percentage, and Trump’s “Greatest” should be at the top.

It’s not.

That honor goes to George Washington, who, running unopposed twice, received 100% in both 1788 and 1792.

Since “the History of our Country” is long and electorally convoluted, let’s focus on just the past sixty years. Is Trump on top of that list?

No.

That’s Johnson in 1964. He won 61.1%, with a margin of 16 million votes.

And Nixon, not Trump, comes in for a close second in 1972, winning 60.7%. (Because turnout was higher, Nixon won by more votes, 18 million, but a smaller percentage than Johnson.)

Most presidential wins fall in the 50s. Is Trump’s “Greatest” at the top of that list?

No.

That honor goes to Reagan in 1984. He won by 58.8%. Again, because turnout varies, his margin of 17 million votes is above Johnson’s, establishing a clear top three.

The next seven fall in the 50-54% range. Surely Trump’s “Greatest Election” leads that list?

No.

Trump isn’t even on the list:

1988, Bush: 53.4%, +7M

2008, Obama: 52.9%, +9.5M

2020, Biden: 51.3%, +7M

2012, Obama: 51.1%, +5M

2004, Bush: 50.7%, +3M

*1980, Reagan: 50.7%, +7.5M

1976, Carter: 50.1%, +1.7M

Reagan’s first election earns an asterisk because third-party candidate Anderson received 5.7 million votes. Combine that with Carter’s count, and Reagan barely beats Carter’s 1976 win. Carter’s 50.1% is the lowest percentage of any president who still won more than half of the vote.

And who tops the below 50% list?

Donald Trump.

For his “Greatest Election,” Trump won 49.9%, with a margin of 2.3 million votes. Even if you triple that count, Trump’s win falls behind Biden’s and both of Obama’s.

Continuing down the list, Trump did beat Clinton:

*1996, Clinton: 49.2%, +8.2M

Clinton’s second election earns an asterisk though because his vote count advantage drops to .2 million if Dole and the third-party candidate (Perot earned 8 million votes) are combined, leaving Clinton the smallest winning majority count of the last sixty years.

But the next two presidents need double asterisks as non-majority-winners in races with no (significant) third-party candidates. That’s because they both lost the popular vote:

**2000, Bush: 47.9%, -.5M

**2016, Trump: 46.1%, -2.9M

And the bottom two are plurality (rather than majority) winners due to the two historically strongest third-party candidates:

*1968, Nixon: 43.4%, +5M

*1992, Clinton: 43%, +5.8M

If former-Democrat but pro-segregation Wallace hadn’t run in 1968, it’s unclear where his 9.9 million votes would have fallen. 1992 is also hard to analyze since the majority of Perot’s 19.7 million votes could have gone to either Clinton or Bush.

So where does that leave Trump’s “Greatest Election”?

It’s number 11 out 16, the very bottom of the non-asterisk elections. Trump is the smallest majority winner of two-candidate races in the last 60 years. Focus on just the past 7 presidential races of the 21st century, and he beat only his own and Bush’s popular-vote-losing victories.

2024 marks no significant electoral shift. Trump’s margin of victory is historically infinitesimal.

While that’s better than losing the popular vote by 2.9 million, Trump is also looking at much thinner Republican majorities in Congress. When he entered the White House in 2016, Republicans held 54 of the 100 Senate seats, with a 59-seat majority in the House. As Trump enters the White House this week, Republicans hold 53 Senate seats, with a 5-seat majority in the House. That’s an even smaller House majority than after the 2022 midterm elections, which had been the smallest since the 1930s. Since three Republicans are leaving for appointments in the White House, the majority shrinks to two until special elections.

Republicans should expect a range of Congressional dysfunction mixed in with several very tight legislative victories, ending in 24 months since midterm elections tend to favor the minority party. Democrats lost 63 House seats under Obama in 2010, and Republicans lost 40 under Trump in 2018. Biden lost only 9 seats in 2022, but even that would be enough to flip the House.

Republicans are likely to keep control of the Senate in 2026, though that’s not guaranteed either. They will be defending 20 Senate seats, while Democrats defend 13.

Meanwhile, the GOP has a two-year window with a historically thin House majority and the smallest majority-winning president in a quarter century.

That’s what Trump called “an unprecedented and powerful mandate” on election night and what his new press secretary continues to call “winning the election with a resounding mandate.”

January 13, 2025

Black Characters Colored Green

One of my all-time favorite essays, Zoe Smith’s “4 Colorism,” starts with a page from Gold Key Comics’ Brothers of the Spear #11 (December 1974) where “black people” appear “thoroughly and intensely green.”

Why?

Because, Smith concludes, “print methods adopted by the comics industry early in its history didn’t have any way to consistently reproduce the color brown” (2019).

That’s certainly true, but because the rest of Smith’s excellent essay is about printing accidents and then later trends in four-plate coloring, it never occurred to me that Gold Key Comics could have selected green intentionally.

Then Neal Adams experts Paul Michael Moon Rogers and Lee Hester shared a page from the Washington Star newspaper’s 1969 The Story of the Washington Star, a giveaway comic book drawn but not colored by Adams. It also features a green Black character.

When Smith first saw the green-skinned characters in Brothers of the Spear, she wondered: “Are they Skrulls or something?”

One of the commenters on the Neal Adams thread tried to identify the comic with a similar assumption: “Boy is green like Beast Boy so I’ll guess Teen Titans.”

Because the green is consistent across panels, I’m now thinking that, rather than a result of printing error, the green in both cases was selected with the intention of representing Black skin.

That sounds crazy (because it is crazy), but the historical context is even more complicated.

Until around 1968, Marvel and DC used taupe (AKA gray-brown) for all Black people, like Gabe Jones in Marvel’s Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos #1 (May 1963). I find the effect is even more jarring in digital recreations, what Smith calls “straight up gray.”

Like green, taupe is not a human color. Using an inhuman color to represent Black people is disturbing. Given that racist baseline, I’m trying to understand why these specific colors were repeated.

I’m guessing taupe was selected because it contained some brown but printed more consistently than brown or non-brown gray. When Marvel first published the Hulk in The Incredible Hulk #1 (May 1962), Stan Lee insisted on gray skin. Colorist Stan Goldberg: “I told him why it wouldn’t work, and it didn’t work, because we couldn’t keep the color consistent throughout the book. Sometimes The Hulk was different shades of gray, and even green in one panel” (Alter Ego #18, 16-17). Beginning with The Incredible Hulk #2 (July 1962), his skin was intentionally green.

Smith notes a similar problem in Hero for Hire #5 (1972): “In my copy, black skin is inconsistent from panel to panel … Luke Cage’s skin is almost the same shade of army green as the pants of the white man he’s fighting.”

Hulk’s 1962 skin was intended to be gray and accidentally turned green. Cage’s 1972 skin was intended to be brown and accidentally turned green. Assuming the colorists at the Washington Star in 1969 and Gold Key Comics in 1974 were aware of the difficulties of printing brown and gray, did they actually consider green to be a plausible alternative?

My short answer: yes.

My long answer is the chapter “Coloring Theory” I drafted for my book-in-progress, “The Color of Paper: Representing Race in the Comics Medium.”

Here’s a medium-length answer:

Neither colorist believed that green resembles the color of any person. But their goal wasn’t about resemblance. The racial logic of four-plate coloring requires members of different races to be represented by different colors. It’s an extension of the racial logic of a black/white color dichotomy. It doesn’t matter that the actual skin colors of white and Black people are overlapping ranges, and that most if not all of the colors in the combined range are some shade of brown. Four-plate coloring was used to fulfill the racial fantasy of absolute and visually determined racial differences. That requirement trumped any concern for resemblance. The beige of white skin was comparatively easy to produce on off-white paper, but since browns were generally avoided due to printing inconsistencies, colorists selected some other color to represent the color of Black skin.

Most comics companies used taupe before switching to a more human but less predictable brown in the late 1960s. Since Gold Key had only been around since 1962 (I think?), and the Washington Star wasn’t in the comics industry, their colorists may not have been as familiar with the taupe norm and went with green instead. Neither color has anything to do with resemblance. Both are used to communicate a racial category while paradoxically revealing nothing about the skin of the individual characters represented. For reasons I won’t go into here, I call that “linguistic color.”

But returning to Zoe Smith’s essay, the intent to use green as a linguistic color doesn’t preclude a range of other printing errors.

Look at that Neal Adams page again:

Whose left hand is drawn in the bottom right of the panel? The Washington Star colorist apparently thought it belonged to the second kid, but that’s anatomically impossible. It’s the foregrounded character’s hand, so (using the colorist’s deranged choice of green) the panel should look like this:

Or possibly this:

Which highlights the second printing error. The character’s face consists of two shades of green arbitrarily dividing his face:

I don’t know enough about what exactly happens with color plates during the printing process, but the green in the left half of the image looks browner to me, close to what Smith called “army green” when describing that Luke Cage panel:

The Brothers of the Spear page is inconsistent too. Setting aside the fact that the ground in the four panels changes from green to purple to orange and then back to green (that’s only slightly different from the green of the foregrounded characters), the green fluctuates within characters too.

I had assumed that was a mechanical printing error, but now I find myself wondering: did the colorist or a printer technician select slightly different greens?

I’m also wondering how many more green-colored Black characters appear in late 60s and early 70s comics.

January 6, 2025

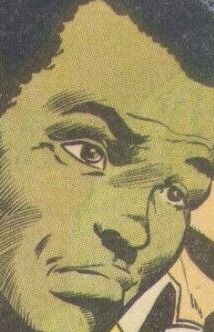

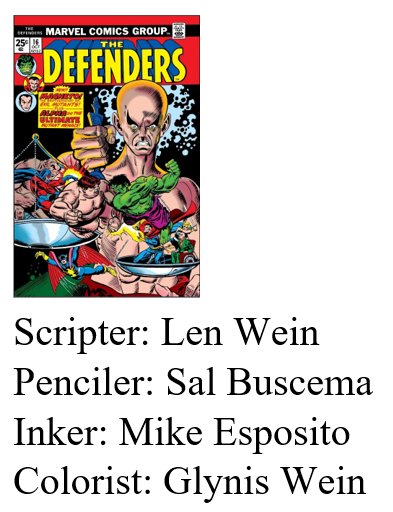

“What Horror Has Magneto Wrought?”: Coloring Marvel’s Racial Fantasies

I’ll be in New Orleans soon, presenting on the MLA panel “Envisioning Racial Futures: Race, Ethnicity, and Speculative Comics.” The Comics Forum organizers asked:

“How have science fiction, fantasy, and speculative graphic narratives imagined racial identity, ethnic conflict, social justice, and the future?”

My abstract answered:

Superhero fiction is an amalgam of science fiction and fantasy that reflects the real-world circumstances of its publications. With notable exceptions, superhero comics have applied speculative genre norms formulaically, while reinforcing racial thinking of white creators, viewers, and publishers. Rather than treating such a comic as the unified product of its multiple authors, I divide The Defenders #16 (October 1974) by its semi-independent contributions. Len Wein’s script features the supervillain Magneto’s plight to end “the vicious persecution” of mutants by using ancient alien technology to create “Alpha, the Ultimate Mutant,” who in his “Neolithic” stage penciler Sal Buscema renders as a racist caricature of a Black man but whom colorist Glynis Oliver assigns the color printing code for white skin. As Alpha evolves, Buscema draws white facial features and then alien ones, while Oliver maintains white skin. While it’s unclear who made the initial choices – Is Buscema’s caricature based on Wein’s descriptions? Did Oliver prefer white or did her editor require it? – the black-and-white reprint in Essential Defenders Vol. 2 (2006) alters them by requiring viewers to project Alpha’s skin color onto the diegetically meaningless gray-white paper. I have conducted a quantitative study to measure viewers’ racial impressions of the evolving character in both the color and black-and-white appearances, while also subdividing study participants according to their reported ethnoracial identities. While the science-fictional fantasies of Defenders #16 extend Marvel’s implicit criticism of the early 70s Black Power movement, they also reveal the incoherence of its racial thinking produced by its multi-author approach and larger historical context.

The previous issue, #15, is the first comic I ever read, and I first blogged about the story arc two and a half years ago. That post has since evolved into a chapter subsection in The Color of Paper: Representing Race in the Comics Medium, which is out for external review at a press right now.

To avoid reading aloud, I try to design slides that are almost sufficient if viewed silently. They’re never quite, but I think you can follow most of the argument:

I think that last slide leaves out the most, so here’s the accompanying conclusion:

No character in the issue is assigned Black-denoting skin color, and Alpha’s evolved features no longer evoke caricatural Blackness after the fourth page. Mutantkind then appears to be exclusively White. By preventing an understanding of Alpha as a mutant Black man, however racistly drawn, Oliver’s color art defines Homo Superior as non-Black across its evolutionary stages.

If Essential Defenders viewers instead understand Alpha to have Black skin in one or more of those stages, mutantkind is not exclusively White and so is not a racial category.

Oliver’s colors both obscure anti-Black imagery and literalize White supremacy.

December 30, 2024

A Farewell to Vinyl

I recently offered to drive my father’s vinyl collection to Goodwill for him. He declined. I don’t think he has a way to play them anymore, but that’s beside the point. He’s not ready to part ways.

I gave most of my collection to a friend in my department. That was a little over a year ago, and I haven’t played a single album from the third I kept since, but that’s fine too. He just got the row from the back of the bedroom closet, none of which had been played in the twenty-first century. Mostly for good reason. It’s a semi-eclectic mix of the pretty good, the quite bad, and the shockingly awful. My teenage self is (mostly) to blame.

As a relative newcomer to Spotify, I am still discovering the joys and horrors of a nearly bottomless online library. During one drive up to see my dad in Pittsburgh, I spun over five consecutive hours of Queen, way way past the recommended dose. My one-sentence rave: “an off-broadway musical soundtrack, but due to an obscure labor dispute, the orchestra was replaced at the last minute with a speed-metal guitarist.” Trying and failing to listen to Rush’s Hemispheres was one the most nostalgia-shattering experiences of my life. Aerosmith was, alas, in the dull middle of those extremes.

The existence of Spotify still bewilders me. Set aside the digital surface, and it’s a return of the 19th-century lending library. I don’t own anything, I just listen to it for a monthly fee? Of course texting bewilders me too: the wireless pocket telegraph replaced the wireless pocket telephone?

I decided to give away the bottom two-thirds of my vinyl when I saw that my much younger colleague had been spinning a remaindered copy of Blue Oyster Cult’s 1972 debut. That is NOT a good album, and I’m a guy who saw them twice in concert (they kept opening for Black Sabbath). He didn’t seem to really care WHAT vinyl he played. It was about the experience of listening to VINYL. In my philosophical / literary-critical terminology, that’s privileging discourse over diegesis. Or maybe medium over message? Either is hard to get my head around.

I started buying albums in the very very late 70s, and didn’t stop till the very very early 90s, after I belatedly accepted that CDs weren’t just some 8-track fad — though now apparently they were? In order to get over my own fatherly farewell reluctance, I staged a photoshoot on my dining room table before driving the stack to their adoptive parent. Most date back to my early 80s high school days, so it’s like bumping into my 17-year-old self, someone I’m not on very good talking terms with. I mean, Molly Hatchet? Seriously, kid? And yet there are a few accidental gems scattered in the batch.

I also owe a personal apology to Neil Young: we had a hell of run, old man. And I deeply respect your Spotify boycott — though I’m looking forward to it eventually ending and the marathon car trip that will follow. (Instant wish-fulfillment: just discovered Neil returned earlier this year! I just made a Playlist of my favorite oddities. I’ll go wider on my next Pittsburgh drive.)

Next dilemma: what do I do with my bookshelves of CDs?

Chris Gavaler's Blog

- Chris Gavaler's profile

- 3 followers