Chris Gavaler's Blog, page 6

October 14, 2024

Fripp vs. Vai

Adrian Belew’s Beat is not a King Crimson tribute band. Belew and bassist Tony Levin’s presence mostly guarantees that, but newcomer Steve Vai oddly does too. When I saw Beat perform in Richmond earlier this month (mostly fulfilling one of my adolescent dreams), I witnessed Vai’s exceptional performance of Robert Fripp’s portion of the 80s Crimson compositions.

Though seemingly note-for-note identical, the waves of hammer-ons, pull-offs, string bending, whammy barring, and — for the most twirling of Fripp’s signature counterpoints — finger tapping surprised me. The leg kicks, pelvic thrusts, and groovy body English surprised me too. Vai’s style is more Van Halen theatrical than Robert Fripp deadpan.

It would be unreasonable and, worse, uninteresting to expect Vai to not only play Fripp’s parts but also to imitate the idiosyncratic ways that Fripp played them. If he did, Vai might bend Beat into the embarrassment of a cover band, one that happened to include two members of the original quartet. Think Judas Priest c. 1996.

If Belew had wanted a Fripp clone, he could have enlisted a graduate of Fripp’s Guitar Craft, all of whom are intimately familiar with their mentor’s idiosyncratic guitar tuning. Vai instead gives Belew’s touring band its own integrity, which I both appreciate and find just a smidge disappointing.

“Lark’s Tongue in Aspic, Part 3,” the concluding anthem of the 80s band’s trilogy, ends with a Fripp lead that’s a startlingly slow and sparse sequence of one-note avalanches. An unfamiliar listener might not realize that a guitar was involved. Of all moments for Vai to untether himself from the recorded original, this seems both the most and least appropriate.

Vai’s lead was blistery in a bluesy way. He grooved. He may even have gotten a tiny bit funky.

Those are not Robert Fripp adjectives. Again, I appreciate Vai for interpreting without imitating. Vai is a member of Beat. Fripp is not. Yet it was also a pleasure to witness Vai’s interpretations because they revealed so much about their absent source material.

Fripp is as far from blues as any rock guitarist has gotten. He does not cavort in 4/4 time. His tuning isn’t conducive to minor riffs. Though his anti-showmanship showmanship might seem stiff or stoic to a casual observer, I would call it methodically tensionless. Rather than its impassioned embodiment, he’s his music’s impersonal conduit.

While I credit Levin’s stick and Bill Bruford’s synthetic drums (which newcomer Danny Carey has appropriately replaced) for so much of the 80s Crimson sound, the guitar duo was its defining premise. Belew brought boisterous virtuoso gimmickry to counterbalance Fripp’s affectless Zen earnestness. He also brought a slide tube, whistle, and power drill. Even watching Belew perform live with Beat, I couldn’t always decode how he produced some of those improbable noises. But having another guy on stage also wiggling his whammy bar maybe felt a smidge superfluous.

Half the fun of Belew is Fripp playing his straight man.

I’ve heard the pre-Belew Crimson called humorless, and maybe it was. But the post-1975 Fripp was something different. My wife and I saw him perform with the League of Crafty Guitarists in the late 80s, and she laughed out loud when he strummed a variation of Hendrix’s “Foxy Lady” in response to another guitarist’s Bach-like flutter of rhythmless atonic notes. “I never heard someone tell a joke with a guitar before,” she said.

Since this is already 80s-themed, think of comic Stephen Wright. While it’s perfectly possible to perform one of his one-liners with a wink and a giggle, he based his stand-up career on an ability not to crack a smile after saying things like: “I’d kill for a Nobel Peace Prize.”

Fripp is the musical equivalent.

Yes, perching motionlessly on a stool with perfect expressionless posture likely is the most efficient way to produce that blur of fingers up and down a fretboard. But it’s also the antithesis of rock ‘n roll flamboyance. Fripp knows that. Obviously he knows that. And he milks the contrast like Wright stretching a deadpan pause. It’s just funnier that way.

Vai, on the other hand, prefers a wink and a wiggle. And why not? The rest of the Richmond audience and I were there to roar regardless.

October 7, 2024

Election Meme Diary

Part I, Part II, Part III, and now Part IV:

The debate moderators did not fact-check all of Trump’s lies.

Can you imagine Trump or Vance sobbing with regret?

I predict the adults in the room will prevail again, but if the government shuts down in two weeks, it’s because of Trump and his House MAGA minions.

That word doesn’t mean what he thinks it does.

He’s no fan of Harris, but unlike Trump’s pro-life supporters, the Pope isn’t fooled by Trump.

For my fellow Virginians (and I think Vermonters and Mississippians too). Vote today!

Voted at 9:30. They said there was a line of 20 people when they opened at 9:00.

Should someone tell Grandpa?

Best line from the Oprah interview.

Other porn-site statements made by Trump’s candidate can’t be printed.

Local Trump supporters don’t care about the Senate and House races though?

It looks like House Dems will prevent another government shutdown this week, and once again Trump and Representative Cline of Virginia’s 6th District care more about spreading election lies than solving problems.

Is “delusional” a strong enough word?

From the same running mate who coined “America’s Hitler,” only four years ago instead of eight.

Vance is trying to rewrite history with lies about Trump supporting Obamacare. From last night’s debate:

VANCE: And I think that, you know, a lot of people have criticized this “concepts of a plan” remark. I think it’s very simple common sense. I think, as Tim Walz knows from twelve years in Congress, you’re not going to propose a 900-page bill standing on a debate stage. It would bore everybody to tears and it wouldn’t actually mean anything because part of this is the give and take of bipartisan negotiation. Donald Trump could have destroyed the program. Instead, he worked in a bipartisan way to ensure that Americans had access to affordable care.

WALZ: The first thing [Trump] was going to do on day one, was to repeal Obamacare. On day one, he tried to sign an executive order to repeal the ACA. He signed onto a lawsuit to repeal the ACA, but lost at the Supreme Court. And he would have repealed the ACA had it not been for the courage of John McCain to save that bill. Now fast forward. When Donald Trump said, “I’ve got a concept of a plan,” it cracked me up as a fourth-grade teacher because my kids would have never given me that. But what Senator Vance just explained might be worse than a “concept,” because what he explained is pre-Obamacare. You lose your pre-existing conditions. Your kids get kicked out when they’re 26. They’re going to let insurance companies pick who they insure. Those of you a little older, gray, you know, got cancer? You’re going to get kicked out of it.

Evidence from the new federal indictment that Trump knew and admitted that he lost the election but was still fighting to remain in power. That’s called an attempted coup. He doesn’t belong in the White House. He belongs in prison for treason.

I guess he didn’t bother reading his wife’s memoir?

The guy who says women should trust him to be their protector.

September 30, 2024

Beating King Crimson

I was fifteen when King Crimson released Discipline. I fell for it by accident. I borrowed a friend’s home-recorded cassette tape of the band’s 1969 premier, In the Court of Crimson King, which was all my AOR-addled brain was interested in 1981. Discipline was the flip side, which I never played. Then I lost the cassette. Feeling ethically obligated to replace it, I borrowed the first album from another friend and, because I didn’t know anyone else who had it, bought Discipline.

I won’t say it changed my life, but it certainly infected it.

Fast forward two decades, and there’s me, a young father, browsing the frozen food aisle, halting in awe when I recognize one of Robert Fripp’s frippertronics soundscapes droning over the Kroger loudspeakers. I don’t know how many minutes I swayed there listening. I was going to compliment the store manager’s improbable taste, but before making it through checkout, a saner area of my brain assumed control. To be fair, frippertronics, like most ambient compositions, would make excellent supermarket background music. How I could so thoroughly mistake the hum of multiple freezers for the slow cascade of Fripp’s guitar is another question.

I saw Fripp with the League of Crafty Guitarists twice in the late 80s. I saw Belew’s new and very brief band The Bears in the late 80s too. I tried to see the reformed double-trio Thrak version of King Crimson while on vacation in Prague in the 90s, but the arena show was sold out. I remember hearing “Dinosaur” the first time on the car radio driving back from a beach vacation, recognizing Tony Levin’s distinctive bass first, then Bill Brufford’s distinctive drumming, and finally Adrian Belew’s distinctive voice. I was surprised how long it took to find Fripp’s guitar in the mix. It wasn’t the twirling gyre of notes I remembered.

As a first-year college student, I scotch-taped a King Crimson poster above my bed. It was promoting the 80s band’s second album, Beat, a tribute to the beat writers I hadn’t read yet. Three of a Perfect Pair came out later that year. I inflicted the trilogy on family and friends. My sister choreographed a dance for her college’s undergraduate modern dance company titled “Five of a Perfect Square.” I remember my father remarking that “Heartbeat” was really just a standard rock song in comparison to the wheels-inside-wheels structure of “Absent Lovers.”

I followed the band members’ zigzagging paths through parallel ventures (Peter Gabriel’s fourth album would be unmoored without Levine’s bass stick, and Bowie’s best albums are a game of musical chairs for Belew and Fripp leads). I tried to like Crimson’s 70s albums, but they were too 70s, and not in that lovely way I increasingly relish now. I followed the post-Thrak Crimson for years too, but when even Below vanished from the line-up, I had to admit I’d lost interest too.

I still track Fripp’s branching solo projects, but none enthrall like the anarchic band of my late adolescence. While that obviously has a lot to do with me specifically and adolescence generally, I still think the 80s Crimson remains unrivaled (with possible exceptions of New Zealand’s Fat Freddy’s Drop, the 90s triptrop pioneer Portishead, and of course Tom Waits, but those would all be very different blog posts). Each Crimson song is a sonic puzzle of interlocking counterpoints punctuated with atonal upheavals, like a gear shivering loose and shattering in the maw of a relentlessly spinning machine. I listened for hours trying to pick apart the blade of each string, the impossible thwapping time signatures, the barbaric yawps of Belew’s absurdist lyrics. Crimson was that most-abused word of all: unique.

All of this is to say how throbbingly thrilled my teen heart was when I heard Belew had gathered a new iteration of the old band to take On The Road. Tony Levin signed on too, and new members Steve Vai and Danny Carey. They call themselves Beat, and while it’s not King Crimson, neither is the other band currently using that name.

I’ve got my ticket for the Tuesday October 8 concert in Richmond, VA.

September 23, 2024

Next Weekend is Vampire Weekend

Vampire Weekend (2008)

Probably the best of the five, the debut stands out as what I’m going to call a “performed band album.” The arrangements, the instrumentation, the shifts and turns and gaps and idiosyncracies, they all display the collaborative intelligence and locked-room logic of a foursome discovering and inventing their way through a playlist of evolving first-evers. The rhythm section, drummer Chris Tomson and bassist Chris Baio, is as defining as the sonic badminton between Ezra Koenig’s guitar and voice and Rostam Batmanglij’s oddly varied keys (exactly what kind of organ is that?). I think Batmanglij produced, but the album has the feel of a carefully recorded live performance, or rather the culmination of many many exploratory live performances documented in a studio finale. I remember the first time I heard “Mansard Roof” on the radio (or maybe it was the satellite equivalent) and feeling instantly intrigued, ears cocked like our cat’s. It wasn’t until years later that I learned how utterly afropop their sound was.

Contra (2010)

Batmanglij definitely produced and with one all-consuming mantra: This is absolutely not our first album. It’s at times aggressively unperformable, a layering of studio-only fits and quirks, which I deeply respect though don’t necessarily enjoy. The production style has the ethos of a Lego building. Not one of those meticulously designed movie tie-in kits, but the multi-kit bin of mismatched pieces that accumulated in the corner of my son’s bedroom over years and years. Just reach in and start snapping pieces together: a measure of drumbeats, a loop of found sound, a thrash of guitar, repeat chorus vocals here. It’s a good album, but my least favorite of the five. I’d thought the lyric was “drinking hot chocolate,” but I wasn’t really paying attention. I remember feeling sad when I read a pan by a pop-culture critic I admire. Most songs are better live.

Modern Vampires of the City (2013)

I drove my then-teen daughter and one of her then-best friends to see a show in Charlottesville, about an hour from our much much smaller small town. They opened with “Diana Young.” I may have very quietly teared up during “Unbelievers” for reasons that still remain obscure to me. Ariel Rechtshaid produced what I’m going to call a “performable album.” Here’s the difference: when Tomson isn’t heard drumming for any span on the first album, I still see him sitting there at his drumkit, counting, waiting, sticks poised for the next slap and shuffle. When Tomson isn’t heard playing for any span on the third album, it’s because Rechtshaid didn’t press a button. To be clear, Rechtshaid does and does not press many many buttons in really engaging and beautiful ways. This is a great album, my daughter’s favorite, maybe mine too. It’s only through contrast that I feel how its sonic puzzles are solved and structured by a logic of studio production that reduces the band to session players. Really really good sessions players on a really remarkable album. It was only live that I realized “Hannah Hunt” is too slow for an encore.

Father of the Bride (2019)

Six years is a long time, especially after a previous 2-3 year pace. To be fair, it’s not a Vampire Weekend album. Not only had Batmangli left (alas, his solo album didn’t hold up no matter how many times I played the CD), but Tomson and Baio aren’t on it either. It’s a Koenig solo album, and a pretty extraordinary one. Rechtshaid produced again, which provides a modicum of past consistency, though quickly wiped out by Koenig’s country plucking and Danielle Haim’s multiple guest duets (apparently she and Rechtshaid were dating?). There’s no band. It’s a mix tape of discordant hits and B-side gems that could have been recorded different years on different continents. I quibbled with the song order, but all of my imagined playlist reshufflings were equally flawed. There’s just more here than can be made logical through sequence. When I purchased a download (my first ever), I got a second copy of the CD for free, which I literally couldn’t give away. My son and some of his college friends saw them this tour. They opened with “Sympathy,” my favorite at the time.

Only God Was Above Us (2024)

Turns out five years isn’t all that long. The new album sounds like previous albums, only more so. Rechtshaid produces again, which may provide a little too much consistency. When Koenig’s songwriting hits a familiar turn, the production framing it calls back to the past too–those “Diana Young” drums again. I’m enjoying the panicked froth of Rechtshaid’s layering of even more instruments and orchestral gadgetry–how about a saxophone lead this time? I texted my kids links to “Pre-School Gangsters” and “Connect,” insisting they’re two of Vampire Weekend’s best songs ever, which they are. Though I just now realized while playing Spotify in the background as I type, it’s “Prep-School Gangsters,” which isn’t nearly as good a title, but I still admire Koenig (whose kid turned six last month) as one of the all-time best rock lyricists, and now I can actually understand the words as they scroll down my iPhone screen. I drive up to Philadelphia to see them with my daughter on Saturday. She lives in Philadelphia, has for years. My son was going the following week in New York with a former roommate, but that fell through in ways too complicated to report in a blog pretending to be about album reviews.

September 16, 2024

Memes! Memes! Memes! (part 3)

I’ve stopped calling these “political cartoons” because none are drawn, which is often considered a defining quality of a cartoon. They are certainly image-texts, but few non-academics use the word “image-text.” So even though none of them have been shared widely enough to satisfy the original meaning of “meme,” I’m sticking with that term and its increasingly generic usage. I also think the series (which starts here and continues here) might be a comic, since it is a sequence of image-texts, which also describes most comic strips, comic books, and graphic novels. If blogs count as publications, then the sequence is in both the comics form and the comics medium. The chronological order even tells a story: the last two weeks in election news, with a heavy dose of debate memes.

The first is from September 3rd and includes a longer-than-usual preamble:

On one hand, this is just funny: Someone (presumably an insider since they had access) derailed the Trump campaign with a $14 gadget that does nothing but occasionally beep. On the other hand, this is a guy who still wields massive influence on national security. In April Trump killed the compromise House bill to extend the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act by tweeting: “KILL FISA, IT WAS ILLEGALLY USED AGAINST ME, AND MANY OTHERS. THEY SPIED ON MY CAMPAIGN!!!” Barr, Trump’s former Attorney General, responded: “I think President Trump’s opposition seems to have stemmed from personal pique rather than any logic and reason. The provision that he objects to has nothing to do with the provision on the floor.” How is this guy running for president?

Another Trump business tumbling toward bankruptcy. Does anyone still remember Trump Steaks, Trump Vodka, Trump Mortgage, Trump Ice, Trump Magazine, Trump Airlines, Trump Entertainment Resorts, or GoTrump.com? Trump’s mini-Twitter Truth Social will soon join them. And yet we’re supposed to vote for him for his business skills?

Trump’s first cabinet member. He plunged the value of Twitter by 72%.

Current totals. The first one will change right after the election.

A question for superhero fans: Which is funnier, that Trump thinks he’s Superman, or that of all the major superhero movies of the last decade to photoshop, he picked the least popular and worst reviewed?

Trump’s been prepping for tonight’s debate.

So many extraordinary moments to choose from, but this is definitely my favorite from Trump’s deranged performance.

Even his post-debate performance was delusional.

The most important reality check from Trump’s fever dream.

Most instantly influential endorsement ever?

Oh, no! Not the geese too! Days after the debate, and he’s still on the same rant.

Not that I blame him. I wouldn’t get in a ring with Harris again either.

September 9, 2024

Judging Race in “Judgment Day!”

As folks who have visited my blog before probably know, I’ve been working on my book-in-progress The Color of Paper for a while now. I’m nearing a book contract, but I got some recent feedback that revealed that my introduction wasn’t doing the basic job of an introduction: introducing unfamiliar readers to the book

So I’m now beginning with an example that I hope encapsulates what the rest of the book explores in detail: how a material image composed of ink on paper conveys the culturally constructed concept of a racial category. I think the example is also one of the more prominent single-image racial representations in the history of the comics medium.

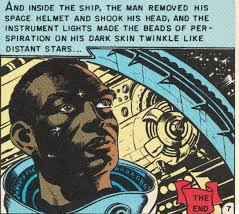

Qiana Whitted opens her Eisner-award-winning EC Comics: Race, Shock, and Social Protest with a discussion of scripter Al Feldstein and artist Joe Orlando’s science fiction comic “Judgment Day!” in Weird Fantasy #18 (March 1953). “When the space investigator removes his helmet in the final panel,” writes Whitted, “viewers see for the first time that [he] is a black man” (4). Whitted later describes Orlando’s framing, how the astronaut’s face is “positioned generously in the foreground against the ship’s machinery so that there is no mistaking him” (116), meaning no mistaking that he is “a man of color” (117). According to Orlando, his drawing is an especially effective rendering of “a black guy,” superior to any by fellow EC (Entertaining Comics) artist Wally Wood (116). Whitted agrees, noting generally that Orlando’s “line work was known for its precision and craftsmanship” (115) and specifically that this drawing “accurately reflects the features of a man of African descent in the texture of his hair, the physical rendering of his lips and nose, his deeply set eyes, and his cheekbones” (116).

Colorist Marie Severin assigns a medium brown to the area of the image representing the astronaut’s skin, contrasting the surrounding yellow and blues of the space suit and ship interior. Severin’s skin color choice also contrasts the inhuman gray-brown used by other comics publishers of the period, including Marvel’s predecessors Timely and Atlas, to denote Black skin. In 20th-century comics printing, the astronaut’s brown skin was produced by a combination of blue, magenta, and yellow percentage-sized dots on the off-white surface of pulp paper. Though the brown is printed uniformly and so unrealistically, combined with Orlando’s use of opaque black for hair and shaded facial areas, the effect is overall realistic. Whitted also suggests that the astronaut’s “dark skin becomes an expression of space itself” (128), though that effect is conveyed more textually than visually through narration printed in the final caption box: “the instrument lights made the beads of sweat perspiration on his dark skin twinkle like distant stars.”

According to Feldstein’s account, the head censor for the recently formed Comics Code Authority immediately recognized the image as representing a “Negro” (Hadju 322). Was it Orlando’s rendering, Severin’s color selection, the “dark skin” of Feldstein’s text, or some combination of the three?

Beginning in 1954, the Comics Code prohibited a range of offenses including the “ridicule” of any “racial group,” as was previously common in the medium’s drawing norms. Stanford W. Carpenter describes the astronaut’s “low angle head shot” as “quite handsome” and therefore not “caricatured according to traditional codes of cartooning and comics art” (29, 30, 20). Whitted terms Orlando’s style “an aesthetics of accuracy” (118), which means the astronaut’s Black racial identity is not conveyed through what Rebecca Wanzo calls “the phantasmagoric nature of stereotype” which contains “no relationship to real phenotype” (1). Orlando does not reproduce aspects of the minstrel tradition that dominated the visual representation of Black people in U.S. from the early 1800s to the mid-1900s. Had Orlando, for example, exaggerated the astronaut’s lips or nostrils to impossible proportions, viewers familiar with those racist visual tropes might recognize them as symbolizing Blackness. Viewers instead observe Orlando’s drawn image as though observing an actual individual, forming conclusions about the depicted figure’s race as they might form conclusions about any observed individual’s race.

Since the fictional astronaut is from Earth’s distant future and so outside contemporary U.S. race norms, those conclusions are based only on his physical features, the “real phenotype” Wanzo references above. In “Black Looking and Looking Black: African American Cartoon Aesthetics,” Joanna Davis-McElligatt uses “Black phenotype” to reference an artist’s rendering of a comics character’s “Black curly hair, dark eyes, rich brown skin, and wide nose and lips” (199). She places such “portrayals of Black phenotype” as distinct from both “Black expressive culture” and “the conventions of Black being,” as well as distinguishing “Black phenotype, or looking Black” from “Black behavior, or acting Black” (195, 206). The ending impact of “Judgment Day!” requires viewers not to have understood the astronaut as “acting Black,” and so not expressing Black culture or conventions, prior to the last panel where his racial identity is conveyed only through an appearance of “looking Black.”

Based on Orlando’s self-assessment, which Whitted confirms, his original black-and-white image suggests a Black phenotype prior to and so independently of Severin’s color additions. If so, viewers of Judgment Day and Other Stories, the 2014 black-and-white reprint edition of Orlando’s EC works, would still recognize the astronaut’s intended race. The same might not be true of other EC reprints. Whitted agrees with Orlando’s assessment of Wally Wood’s drawing of what appears to be “a white person with dark color,” meaning “racially indeterminate images of African Americans” (116). In such cases, the addition of brown would be racially determining, making color the defining element of phenotype-based racial judgments. Since blocks of colors are applied to paper without gradations or other naturalistic qualities, such as variations between members of the same racial group, color may denote a character’s race while paradoxically revealing little about that character’s diegetic skin color. Wanzo notes an extreme example in which a child with skin rendered entirely in black ink represents a historical figure known to have very light skin (1). Despite the crudeness of the period’s color printing, Severin’s brown when combined with Orlando’s naturalistic rendering might still create the impression of viewing the character’s skin color directly and so not communicate the astronaut’s race symbolically.

Removing Severin’s colors also removes, or at least reduces, the astronaut’s beads of perspiration, since the most noticeable beads are small areas of the off-white paper made legible through contrast. In Orlando’s black-and-white art, the interior of the beads and the astronaut’s visible skin are both represented by the color of the paper, which has the paradoxical ability to represent any color. That page whiteness does not, however, express the blackness of space, which is represented by Orlando’s opaque black ink. In Severin’s color version, only the interior spaces of the beads and the stars are the color of the paper, reinforcing the narrator’s verbal comparison. Even here though, the verbal differs from the visual, since the astronaut’s face is comprised of black and brown with beads of page whiteness, and outer space is comprised only of black and stars of page whiteness. To describe a Black figure’s skin as akin to black outer space is to understand “Black” as the literal color that the racial metaphor uses to produce a false logic of absolute oppositional difference, literally black and white. Whatever his race, the astronaut’s skin is brown.

The page areas surrounding the rectangular panels in “Judgment Day!” are also uncolored, allowing page whiteness to structure the relationship between images by representing a nothingness that is conceptually distinct from the physical page that each copy of the comic is printed on. The perspective of the final panel also establishes a point-of-view that appears to extend beyond the surface of the page and therefore as if into the bodily space of any viewer holding the comic. If a viewer is white like the Comics Code censor who objected to the astronaut being a “Negro,” then the ending revelation may also reveal that the image’s racially unspecified implied viewer, like the astronaut, is not necessarily white either.

Whitted’s analysis of “Judgment Day!” also provides a visual coda. The cover of her 2019 study features an illustration by Afro-futurist artist Marcus Kiser: an astronaut with a raised helmet visor framed and centered by white gutters. Like Orlando’s image which Kiser’s evokes, this astronaut appears to be Black. Unlike Severin, Kiser uses non-naturalistic hues: the astronaut’s skin and suit are the same blue, and the black of outer space behind him is yellow-orange. By destabilizing color as a racial marker, only the black ink delineating facial features can suggest race. Though non-exaggerated and so nothing like Wanzo’s phantasmagoric stereotypes, Kiser’s rendering of lips and nostrils are larger than Orlando’s, and Kiser’s lines are gestural rather than precise. Orlando’s astronaut also stares off at the distance beyond the top right panel corner, while Kiser’s stares directly forward, merging the image’s point of perspective with the position of an actual viewer.

September 2, 2024

More of My Memes

This series has evolved into a kind of national diary documenting the presidential campaign. This round of 14 began the week before the Democratic convention and ends with the Ronald Reagan reboot movie that opened over the weekend.

Each has a bit of text for context:

I am enjoying how hilariously dysfunctional Trump is about rally sizes. This is the guy who bragged that Germany’s Chancellor said his were as big as Hitler’s. He bragged last week that his were bigger than Martin Luther King’s. Now he’s claiming that Harris has no crowds? It’s like sitcom dialogue.

Kamala is coming for our … cows? It’s so much fun watching this man flail at the one thing he’s skilled at: attacking people.

Maybe the Trump campaign should consider asking Mr. Vance to stop saying so many things out loud?

Did Trump just set a new record for the fastest hypocritical flipflop? In 9 days he went from (falsely) claiming Harris should be prosecuted for election interference for supposed AI-fake photos to posting his own AI-fake photos.

I know I’m a snowflake and all, but I found this moment of the convention unexpectedly moving. And it made me wonder: has anyone in Donald Trump’s 78 years — daughters, sons, parents, wives — ever felt and expressed this sort of love for him?

Still two of my favorite joyful warriors.

Two of my favorite phrases from Michelle Obama’s speech.

Trump’s Fox News rebuttal to Harris proved her point: he’s “out of his mind.” Harris leads with women voters by 13 points, Hispanic voters by 25 points, and Black voters by 60 points.

Kennedy Jr. is hoping for a Trump cabinet position. He was also hoping for a Harris cabinet position, but Harris wouldn’t take his call. Is it too late for Trump to dump Vance for a Trump-Kennedy ticket? They belong together.

I’ve never understood the rules of “locker-room talk,” so could someone please confirm this: Trump tried to insult Harris by comparing her to his fashion-model wife who he was simultaneously insulting?

Because how else do you pose for a selfie?

I absolutely trust Vance on this. I mean, when has he or Trump ever lied or reversed themselves?

I’m not sure if Trump’s latest lie is delusional or grotesquely incompetent. Also, reproductive rights are not just about abortion. A new Trump government would dismantle contraception access too.

Remember this guy? Trump’s Republican Party doesn’t.

August 26, 2024

A Black and White Quiet Place

My favorite moment in John Krasinski’s 2018 A Quiet Place is the concluding shot of Emily Blunt’s character cocking her rifle before the film cuts to black. The gesture tells you everything you need to know — until Krasinski’s 2020 sequel ruined it.

Happily, Michael Sarnoski’s 2024 prequel avoids that flaw. I saw it over the summer, but was waiting till it appeared online to make sure my memories of several images were correct. They were. The film is visually a study in black and white and thematically a racial study of Black and white.

This is the sort of visual/racial analysis I’ve been doing while drafting my current book-in-progress, The Color of Paper: Representing Race in the Comics Medium, so my brain seems tuned to how the visual color dichotomy can be used to reflect on the metaphorical racial dichotomy.

A Quiet Place: Day One opens with Lupita Nyong’o’s character, Sam, as the lone Black person in an otherwise all-white place.

Sarnoski’s camera emphasizes that isolation.

I somehow missed this the first time, but Sam’s black-and-white cat, Frodo, is arguably the central embodiment of black-white and Black-White integration.

Frodo brings the two main characters, a Black woman and a white man (Joseph Quinn’s Eric), together, and the two become the cat’s joint protectors, ending with Sam giving Frodo to Eric to take care of permanently. (Spoiler: the cat lives. More spoilers below.)

It wasn’t until after the first alien attack that I noticed what Sarnoski was doing visually.

In the first image I posted at the top of this page, Sam’s face is covered in white dust from a collapsed theater building. The choice of location is not random. Sam has taken a bus to New York with members of her all-white nursing home community (she’s dying of cancer) to see a (surprisingly engaging) puppet show. The audience is a mixture of people of different races and ethnicities, and, in a familiar kind of monster-movie logic, that fact seems to bring down the walls as a far more otherly race descends.

Afterward, Sam stands in front of a bathroom mirror, staring at her whitened face.

It’s an inversion of minstrelsy blackface, and Sarnoski’s camera lingers as Sam removes the white layer as she would remove stage makeup.

There’s more to be said about that scene, but it sharpened my attention to the interplay between visual black/white and racial Black/white.

When the sound-sensitive aliens attack next, a Black man begs a white man to be quiet because his hysterical yelling is placing everyone in danger — most especially the Black man’s child. When the white man continues making dangerous noise, the Black man is forced to silence him lethally.

Hysterical white men are a Sarnoski motif. To be fair, it’s not all white men. The lead nurse selflessly risks and loses his life while helping the group, but soon another white man is clawing at Sam’s feet as she crawls under a car for safety while he screams for her to save him. How she could is unclear, but in his panic he seems to fall into a default assumption that others generally — or perhaps Black women specifically — exist to aid him. He gives no thought to how his behavior is endangering her. He is, like his predecessor, unsavable, but fortunately for Sam, the aliens soon drag him off-screen in a kind of white-male privilege purging campaign.

When Sam makes his first appearance, he is just as hapless but he’s also harmless. He needs Sam’s help, but he doesn’t endanger her in the process. And though he is white, Sarnoski also makes him British, his accent differentiating him from the hysterically lethal white men of Sam’s country. As an apparent result, he’s saveable and ultimately worthy of Sam’s pity and later her (non-romantic) affection, as he grows into a person willing and able to risk his life to help others — including her black-and-white cat.

It’s during this growth arc that Sarnoski drops in my favorite image.

It’s a quick shot, seemingly just an environment-building image during one of the lulls in action, but look closely.

Chess is the paradigmatic game of black vs. white. Except sometimes instead of white, the pieces that oppose black are light brown — which is also generally the color of white people’s skin. And Sarnoski’s “white” player is actually a combination: some of the “white” pieces are light brown and some are literally white. The two colors are interchangeable within the logic of the game, just as they are in the illogic of racial metaphors. Sarnoski is revealing that illogic to challenge.

When Eric does finally escape the city, while also craddling his newly earned black-and-white cat, a hand reaches down to help him.

That’s the same hand that lethally silenced a screaming man an hour earlier in the film.

Except this time the scene ends in unity. Eric and the father embrace.

Meanwhile, in a now very different kind of racially segregated New York, Sam looks at a photograph of herself and her father when she was a child. Some of the other faces in the jazz club are not as dark-skinned, but it’s a safe and unified community where she can smile and laugh joyously with her own father.

Sarnoski’s alien invasion is a paradoxical horror, one that is brutal and arbitrary (the monsters are literally blind and so Colorblind), but also one that produces an interracial unity for humanity’s endangered future — and its actual audience’s endangered present.

August 19, 2024

The First Comics Page?

“Comics” is a truncation of “comic strips,” a term that now names a whole medium but once named only a work that’s in both the humor genre and the “strips” form. A “comic strip” was just one kind of “strip.”

When Jerry Siegel wrote to Buck Rodgers artist Russell Keaton in 1934, he enclosed his proposed script for “the cartoon strip, SUPERMAN.” “Cartoon” sometimes references a work of humor genre drawn in a simplified and exaggerated drawing style, but since Superman was not humorous and Keaton’s style was not cartoonish, Siegel’s use of “cartoon” indicates something other than genre or style. But his use of “strip” is clear.

When Wonder Woman appeared on the cover of Sensation Comics #1 in 1941, the accompanying text identified her as a new “adventure-strip character.” In 1974, when Stan Lee described co-creating the Fantastic Four in 1961, he called the genre “the superhero strip” and Fantastic Four #1 “the opening strip.”

While always used loosely, “strips” and “comics” were synonyms for decades. It’s too bad that the clearer term, “strips” (which even resembles the French “drawn bands”), died out.

The meaning of “comics” has shifted in other ways. When Coulton Waugh published The Comics in 1947, his book title referenced only newspaper comic strips, AKA “the funnies” or “the funny pages.” The Oxford English Dictionary dates that meaning of “comics” to 1912: “the section of a newspaper containing” comic strips. But the 1892 meaning references not a section of a publication but any publication that contains comic strips. Moving further back, the 1860 meaning instead references a publication that contains “amusing and satirical articles and illustrations.”

The difference between a comic strip and an amusing illustration is debatable, especially since a “cartoon” can mean a single image and so not a strip despite being considered a kind of comic that appears on a comics page. The OED’s definition of “comic strip” also includes a “sequence of illustrations,” as first used in 1912, which means the comic strips that appeared in “comics” in 1892 and the two decades following were not called “comic strips.”

Is Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper a comic?

It began publishing in 1855, well before any of the OED’s first recorded usages. It does contain some “amusing and satirical articles and illustrations” (which suits the 1860 definition), and it does contain “sequences of illustrations” (which suits the 1892 definition), but I was most surprised that it also has a section containing comic strips (which suits the 1912 definition).

The above header, “Comic Department,” is from the May 31, 1856 issue. Here’s the full page:

At minimum the page should replace the OED‘s 1860 example of first usage, since the page includes “amusing and satirical articles and illustrations.” Specifically, the columns of text include unrelated jokes and vignettes, and five of the nine captioned images are single-image scenes meant to be funny. The other four, however, are a comic strip.

Though not laid out contiguously, their sequence tells a four-part story about Mr. Von Swagle buying a top hat for the opera, taking the top hat to the opera, using it as a serving tray for a woman’s drink, and then accidentally popping the hat, causing the drink to spill:

The first three images are arguably “illustrations” — images that merely illustrate the text by reproducing its content visually — but the last does more. In Scott McCloud’s terms, it produces an interdependent word-picture relationship, where the meaning of the phrase “direful consequences” requires the image to reveal it because the tall glass and its spilling are not described in the caption.

Though Mr. Von Swagle’s story suits the definition of a comic strip, the word “Comic” in “Comic Department” could only reference it as being comical. Arguably though, this is the moment when “comic” began its etymological journey toward “comic strip” before doubling back to “comics” in the contemporary sense. Since the “Comic Department” is only one section of the issue, the use of “comic” predates the 1912 meaning by over a half-century.

Leslie’s dropped the “Comic Department” header, but the July 12, 1856 issue follows a similar format:

The key difference is that all of the ten images on the page are part of the same sequence, titled “Mr. Winkey Fum’s Fourth of July.” Like the Mr. Von Swagle sequence, the images are divided by unrelated text, but combine into a single story:

As with Mr. Von Swagle, the word-picture relationships are sometimes interdependent, and so the sequence is not merely “illustrations.” The Mr. Winkey Fum comic strip does lack contiguous juxtaposition between its ten subsections, but that seems like a weak rationale for avoiding the term “comic” or “comic strip.”

Either way, I think the Mr. Von Swagle comic strip may be the first comic strip labeled a “comic” by its inclusion in Leslie’s 1956 “Comic Department” page. Should I alert the Oxford English Dictionary?

August 12, 2024

My Political Cartoons

What’s the difference between a political cartoon and a political meme? I’m not sure. I suspect I make both, and often simultaneously, though sometimes only one or the other — depending on your preferred definitions. I drew none of the images, so they aren’t “cartoons” in that sense, and according to my spouse’s definition, none of these are memes either (none have gone viral), so maybe I should just call them political image-texts?

Instead of diving down a definition rabbit hole, here’s a collection I’ve made this year — with a massive uptick in the last month.

First, the reason behind Biden is why I was always behind Biden:

I wrote a 350-word letter-to-the-editor that came down to this: Republicans spent two years declaring that the US was on the verge of recession and then two years blaming Biden for US inflation even though the US had one of the lowest inflation rates in the world in 2023 and ultimately saved the world economy. Now boil those already boiled-down facts further:

Meanwhile, “The Alitos” would make a great sitcom.

The most hilarious thing about this speech (delivered in Las Vegas on my birthday) isn’t just the lunacy of Trump’s ad-libbing when his teleprompter breaks, but that it’s an allegory about himself (before he tacks on a racist punchline). Even worse, it’s a song by civil-rights activist Oscar Brown from 1963.

It was Trump’s running mate who first called him “America’s Hitler.”

Maybe Trump just wanted to reuse the signs he found under the classified documents in his Mar-a-Lago bathroom?

Problem solved? (Obviously after the debate but before Biden withdrew)

Trump’s choice of Vance doubles down on the GOP’s opposition to reproduction rights. When a bill that would have protected the right to contraception came up in the Senate last month, 48 Republicans opposed it. If the GOP retake the Senate, they will instead pass their “Life at Conception Act,” making all abortions illegal. It was introduced in the House in 2023 and will move forward if the GOP takes control of both halves of Congress and has Trump in the White House to sign it into law.

Justice League of Childless Cat Ladies.

Also, my current Facebook profile image:

I’m not sure which is more amazing: Vance’s performance of complete transformation into a Trump fanatic, or Trump believing it.

Vance is such a comically flawed running mate, did Trump pick him to obscure his own flaws?

Multiracial. It’s confusing. For people born in 1946.

The 2008 Republican nominee defending his opponent against false racial attacks. What happened to that Republican party?

Can you blame him? I’d be scared too.

New York Times the day after Harris announced her running mate: “Mr. Walz’s ‘policies to allow convicted felons to vote, in Minnesota are evidence that he ‘is obsessed with spreading California’s dangerously liberal agenda far and wide,’ said Karoline Leavitt, a spokeswoman for the Trump campaign.”

Glad to have you on the ticket, Tampon Tim.

Taylor Swift fans are hoping she will endorse Harris soon. Until then I love the contrast between why Trump says she should endorse him (he signed a bill that he says made her more money) and what she says she actually cares about in a candidate (anti-discrimination).

Maybe Trump should rethink the whole press conference thing.

And these two New York Times photos from last week’s rallies say it all.

Chris Gavaler's Blog

- Chris Gavaler's profile

- 3 followers