Chris Gavaler's Blog, page 3

May 19, 2025

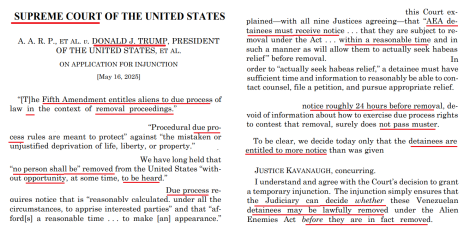

The Foundation of American Rule of Law

Brett Kavanaugh, Trump’s second Supreme Court appointee, said a week before being confirmed in 2018:

“Due process is the foundation of the American rule of law… We live in a country devoted to due process and the rule of law. That means taking allegations seriously. But if the mere allegation, the mere assertion of an allegation … is enough to destroy a person’s life … we will have abandoned the basic principles of fairness and due process that define our legal system and our country.”

The Fifth Amendment established due process in 1791: “No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury … nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law…”

The Fourteenth Amendment further enshrined it in 1868: “nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law…”

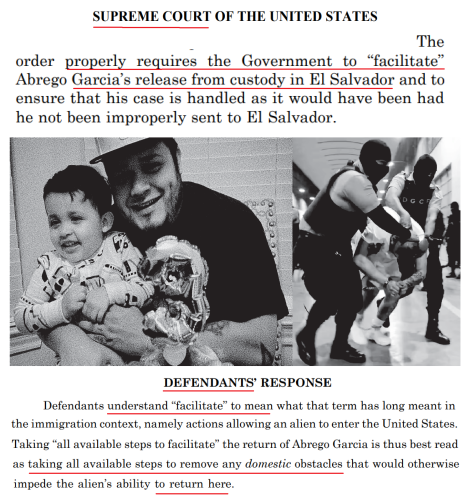

Yet the Trump administration has repeatedly violated the Constitution’s twice-stated due process requirement through illegal deportations, most prominently of Abrego Garcia who, the administration admitted on April 1, was deported through an “administrative error.”

As Justice Sotomayor later noted, Garcia is “a husband and father without a criminal record.” His wife, son, and brother are U.S. citizens. He has lived in Maryland for thirteen years, after committing the misdemeanor of improper entry as a teenager to escape threats of violence in El Salvador. In 2019, a judge barred the government from returning him because it would risk his “life or freedom.”

Six years ago, an anonymous police source asserted the allegation that Garcia is a gang member.

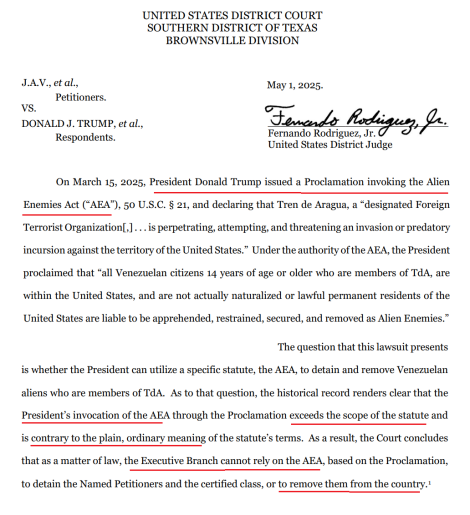

The Trump administration has attempted to justify its deportations through President Trump’s March 15 executive order, “Invocation of the Alien Enemies Act Regarding the Invasion of The United States by Tren De Araguaz.” All courts have rejected the unprecedented use of the Act to deny constitutionally mandated due process.

On April 6, Judge Xinis of the District Court of Maryland wrote: “because equity and justice demand it, the Court grants the narrowest, and daresay only, relief warranted: to order the Defendants return Abrego Garcia to the United States.”

On April 7, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals wrote jointly: “The United States Government has no legal authority to snatch a person who is lawfully present in the United States off the street and remove him from this country without due process. The Government’s contention otherwise, and its argument that the federal courts are powerless to intervene, is unconscionable.”

On April 16, Judge Boasberg of the District Court of DC wrote: “The Constitution does not tolerate willful disobedience of judicial orders – especially by officials of a coordinate branch, who have sworn an oath to uphold it. To permit such officials to freely annul the judgments of the courts … would make a solemn mockery of the Constitution itself.”

On April 17, Judge Wilkinson of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals wrote: “The government is asserting a right to stash away residents of this country in foreign prisons without the semblance of due process that is the foundation of our constitutional order. This should be shocking not only to judges, but to the intuitive sense of liberty that Americans far removed from courthouses still hold dear.”

On April 18, the Supreme Court ruled 7-2: “The Government is directed not to remove any member of the putative class of detainees from the United States until further order of this Court.”

On May 1, Judge Rodriguez of the District Court of Southern Texas ruled: “the President’s invocation of the AEA … exceeds the scope of the statute and is contrary to the plain, ordinary meaning of the statute’s terms… the Executive Branch cannot rely on the AEA … to detain the Named Petitioners and the certified class, or to remove them from the country.” Judge Rodriguez was appointed by Trump in 2017.

On May 9, Judge Sessions of the District Court of Vermont ordered Rumeysa Ozturk released: “Her continued detention potentially chills the speech of the millions and millions of individuals in this country who are not citizens. Any one of them may now avoid exercising their First Amendment rights for fear of being whisked away to a detention centre.”

On May 13, Judge Haines of the District Court of Western Pennsylvania wrote: “the notice that the Executive Branch is currently extending to individuals subject to removal under AEA is deficient under our Constitution … in light of … the Fifth Amendment.” Judge Haines was appointed by Trump in 2019.

And most recently, on May 16, the Supreme Court wrote again: “‘[T]he Fifth Amendment entitles aliens to due process of law in the context of removal proceedings.’ … We have long held that ‘no person shall be’ removed from the United States ‘without opportunity, at some time, to be heard.’ … In order to ‘actually seek habeas relief,’ a detainee must have sufficient time and information … notice roughly 24 hours before removal, devoid of information about how to exercise due process rights to contest that removal, surely does not pass muster.”

Justice Kavanaugh added: “The injunction simply ensures that the Judiciary can decide whether these Venezuelan detainees may be lawfully removed under the Alien Enemies Act before they are in fact removed.”

Still, there are some who reject due process. Republican Rep. Lauren Boebert claims: “If someone is in our country illegally, I don’t believe that there is much due process that is afforded to them. They do not have American citizens’ rights.”

Boebert is factually wrong. Justice Scalia wrote in the 1993 Supreme Court decision Reno v. Flores: “it is well established that the Fifth Amendment entitles aliens to due process of law in deportation proceedings.”

When asked, “Is everyone on U.S. soil, citizens and non-citizens, entitled to due process?” Secretary of State Rubio answered, “Yes, of course.”

Yet when President Trump was asked if he agreed, he answered, “I don’t know. I’m not, I’m not a lawyer. I don’t know.”

Despite not being a lawyer, Trump attacked the Supreme Court’s most recent 7-2 ruling against him, complaining that in order to get alleged criminals “out of our Country, we have to go through a long and extended PROCESS.”

Trump’s senior director for counterterrorism, Sebastian Gorka, suggests that anyone demanding due process is “aiding and abetting criminals and terrorists” which “is a crime.”

He added: “It’s not left and right, It’s not even Republican or Democrat. There’s one line that divides us: Do you love America or do you hate America? It’s really quite that simple.”

Gorka is inadvertently correct. Trump-appointed Justice Kavanaugh said seven years ago: due process defines America. Only those who hate our country disregard it.

.

.

May 12, 2025

Teaching Krazy Kat in a Modernist Poetry Course

The above strip was first published on January 6, 1918, and I placed it first in the selection of Krazy Kat dailies I assigned to Professor Lesley Wheeler’s Modern Poetry students earlier this spring. George Herriman doesn’t usually share syllabus space with T.S. Eliot, H.D., and Langston Hughes, but there are good reasons why he should.

I was subbing for a day because Lesley was at the AWP conference, but she’s taught Herriman’s Krazy Kat in previous iterations of the course too. Her ENGL 363 is continuously evolving, and this semester it was titled “Modern Poetry’s Media.” The comics medium isn’t a typical home for poetry, but Herriman’s verbal and visual experimentation offers an exception.

The homework reading included: Gabrielle Bellot’s “The Gender Fluidity of Krazy Kat” (New Yorker, January 19, 2017), and “Seth on Peanuts: Comics = Poetry + Graphic Design” (which excerpts passages from a 2006 interview in Carousel magazine). I culled fifteen Krazy Kate dailies from online archives (The Comic Strip Library is particularly useful), leaning more heavily on poetic allusions than I would when teaching Herriman in a comics course.

I’ll post my selection first, then my lesson plan below:

September, 1918

April 30, 1919

February 19, 1919

January 21, 1919

January 23, 1919

June 10, 1919

May 8, 1919

February 20, 1919

May 13, 1919

May 3, 1919

December 18, 1918

December 12, 1918

October 26, 1918

April 1, 1919

I also included five Sunday comics from the same 1918-1919 span:

This last one keeps Krazy Kat in its natural habitat, showing how the comic first appeared on a newspaper page:

As usual, my plan changed as soon as I entered the room. I asked everyone in the semi-circle of twenty students to introduce themselves and name one thing that personally interested them from the readings. That always takes more time than I expect (about ten minutes this time), but the brief back-and-forths are worth it, getting everyone’s voice heard and laying all kinds of helpful groundwork.

The students placed a couple of key biographical facts from the Bellot article front-and-center. One mentioned Herriman’s race. Bellot writes:

“Herriman was born in New Orleans, in 1880, to a mixed-race family; his great-grandfather, Stephen Herriman, was a white New Yorker who had children with a “free woman of color,” Justine Olivier, in what was then a common social arrangement in New Orleans called plaçage. George Herriman was one of the class of Louisianans known as blanc fo’cé: Creoles who actively tried to pass as white.”

The detail made the student go back and reread the “invisible in front of a black sheet” in new light (the Sunday strip is my personal favorite and grew into a section in the first chapter of my forthcoming The Color of Paper.)

Another student brought up Krazy Kat’s gender identity. Again, from Bellot:

“In an era when books depicting homosexuality and gender nonconformity could lead to charges of obscenity,“Krazy Kat,” Tisserand notes, featured a gender-shifting protagonist who was in love with a male character. Herriman would switch the cat’s pronouns, so Krazy’s gender, to the consternation of many readers, was never stable.”

Bellot published the article in 2017, and asking “what ‘Krazy Kat’ means at the dawning of a Donald Trump Administration,” a statement that resonates again at the dawning of a second Donald Trump administration. I also pointed attention to Bellot’s statement: “Reading ‘Krazy Kat’ in light of Herriman’s silent struggles with his identity layers a soft poignancy over its stories of a cat, a dog, and a mouse. As a trans woman who, like Herriman, is multiracial, the strip spoke to me in unexpected ways.”

There were plenty of other comments too, including (my favorite) how Herriman’s use of meta makes Krazy Kat feel especially modernist.

With a wide range of reactions fully voiced, we delved deeper into the comics. I “started” my lesson plan by dividing the room into pairs, assigning them the first ten strips to perform aloud as dialogues, including sound effects. I initially asked them to stand up, but reading from laptops proved clunky. One pair did construct a paper brick to “zip.” In addition to being really fun, the micro-performances voice Herriman’s language (which is often written in a kind of semi-phonetic dialect), including the back-and-forth rhythms.

We discussed what we heard a bit, and then I asked all of the Ignatz readers to raise their hands, then all the Krazy readers to raise theirs, telling each set to list their character’s key traits. We moved around the circle twice, hearing points of agreement, disagreement, and variations between. Personally, I’d never considered the Ignatz-Krazy dynamic in terms of older-younger siblings, and both characters were described as being both smarter and less smart than the other — which opened discussion into the contrasting ways each has their own kinds of authority.

A couple of students included visual qualities in their descriptions, which transitioned to my asking everyone to draw their character. After a minute or two, each shared their drawing with the students on either side of them, and we discussed details. Krazy’s tail provided the longest analysis — how Herriman sometimes renders it in a Z shape, and what that graphic quality means within each strip and overall.

Students were already describing the rhythmic role of panels, which segued to Seth likening comic strips to haikus — though I said quatrains may be a better parallel for four-panel strips. I mentioned that “stanza” means “room” in Italian (alas, no Italian speakers were present to draw out that fact), which is similar to the function of the panel. I asked everyone to pick a favorite passage from Seth’s article, write something down about it, then talk to their partner, before opening discussion to the whole room. I also wrote “Doot-doot-doot Doot” on the board, the rhythm Seth identifies for Peanuts strips. I thought we would get to the rhythmic differences between Herriman’s three- , four-, and five-panel strips, but it didn’t come up organically, and I wanted to explore some of the Sunday comics before the hour ended.

So reusing the Ignatz/Krazy division, I asked half the class to list ways the Sunday comics are similar to the dailies, with specific examples, and the other half to list ways the Sunday comics and the dialies differ, also with specifics. Many smart things emerged in the final ten minutes, including how the Sundays feature a narrator who combines qualities of Herriman-like omniscience with character-like narrative involvement. The Sundays are also like free verse compared to the rigid panel structure of the dailies.

More things were said, and many more could have been said, but time ran out. I of course overplanned, so never asked my culminating question: “In one (as long as you like) sentence, what is Krazy Kat about?”

Since Bellot emerged in the opening discussion, I had already jettisoned: “Apply Bellot to the KK selection; link a passage with a specific strip. Explain connection.”

And I never really thought we’d get to my final bit of fun: “Draw a new KK comic strip that illustrates/continues a central element.”

Maybe next year.

May 5, 2025

Recent Portraits

By “portraits” I mean photo-sourced drawings made in MS Paint.

Last fall, I started making “hazardous cut-outs,” which were fast and so very loose sketches, usually based on photos, though with little resemblance to the source. If I went back in and revised though, I could get them closer. Recognize this actor?

Then while trying to revise (based on a photo of my mother before radically diverting), I discovered how much further I could develop the digital woodcut effects:

I refined the technique on a photo of a fellow student in the drawing class I was auditing last fall. It doesn’t particularly look like her, but it proved to me that the approach could produce a level of realism:

That led to my first successful (meaning recognizable) self-portrait, which I detailed in “How I Make Non-Crappy Art in MS Word Paint.” It felt invasive to get other people’s faces wrong, so I kept picking on myself:

Annoyed about the election, I then drew every losing presidential candidate of the last forty years for an essay-in-progress tentatively titled “Losers I voted for and losers I didn’t vote for.” Here are two:

Illustrated essays became my new thing. The second featured drawings of actors from movies I watched with my father during visits home after the pandemic. The first is from Soylent Green, the second from Death by Murder:

Next I decided to commit to drawings as an equal element of the storytelling, ie “comics.” The first comic included portraits of two authors and one of my favorite comedians:

The second recounted my parents’ involvement in the civil rights movement in the early 70s, based on an essay my father wrote that I posted on MLK day back in 2015:

More portraits followed, often triggered by requests from family and friends:

I also started another series based on 19th-century photography:

And I’ll cap this with my latest self-portrait, based on a photo Lesley took of me in a Madrid cafe last month.

April 21, 2025

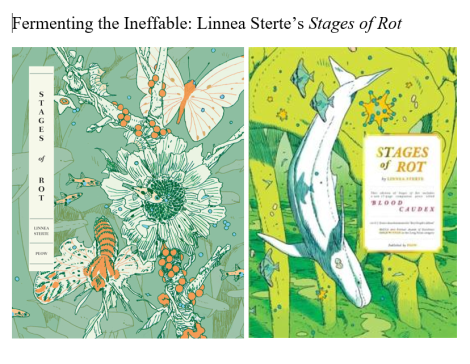

Fermenting the Ineffable

I will be presenting my paper “Fermenting the Ineffable: Linnea Sterte’s Stages of Rot” at the “Fermentation and Literature” conference held at Saint Louis University in Madrid later this week. It’s the first conference I know of that includes a thematically relevant visit to a brewery and winery.

The Call for Papers was also delightful:

“The 1516 German Purity Law (Reinheitsgebot) limited the ingredients of beer to barley, hops, and water. Yet, this restriction overlooks the invisible and essential agent behind fermentation: yeast. Only centuries later was yeast recognized as the microorganism that drives fermentation. Prior to its discovery, fermentation was often attributed to divine or spontaneous forces, with no understanding of the microbiological agents at play.

“Fermentation, however, extends far beyond yeast and beer. It is an alchemical process that transforms ingredients—grapes into wine, milk into cheese, or cabbage into sauerkraut—catalyzed by a range of organisms. Yeasts, molds, and bacteria work behind the scenes, shaping the flavors and properties of food and drink, while simultaneously altering how humans understand biology, culture, and society.

“In science, yeast has become one of the most widely used “model organisms,” employed across fields from genetics to synthetic biology. Its simplicity makes it indispensable in research, yet its identity as a specific fungus is often downplayed in favor of its utility. Despite its ubiquity in laboratories, yeast remains in the scientific background, a cellular factory rather than a subject of study in its own right. This anonymity mirrors the history of fermentation’s agents, often seen as natural or given, rather than as integral co-producers.

“Beyond biology, fermentation’s transformative process has been mythologized across cultures. From ancient brewing traditions to modern artisanal movements, fermentation is both practical and symbolic. It holds the power of transformation—not only of ingredients but of perceptions, as seen in the rise of slow food, fermentation festivals, and the ongoing rediscovery of pre-industrial methods.

“In the wake of the fungal turn, led by thinkers like Anna Tsing and Merlin Sheldrake, much attention has been given to mycorrhizal fungi and their capacity to interconnect ecosystems. However, the role of fermentation and its agents, particularly yeasts and bacteria, has been underexplored in both scientific and cultural analysis. Fermentation’s potential lies in its capacity to catalyze new ideas—how might fermentation as a process or metaphor reshape how we think about symbiosis, transformation, and agency in the Anthropocene?

“This CFP invites contributions that address the scientific, cultural, and metaphorical roles of fermentation and its agents in society. Topics might include:

– The hidden histories of fermentation’s agents in brewing, food, and medicine

– Yeast and bacteria as tools or metaphors in scientific inquiry

– The role of fermentation in sustainable food systems and climate change solutions

– Cultural representations of fermentation in literature, film, or art

– The intersections of fermentation, human health, and biotechnology

– Historical and contemporary myths surrounding fermentation and its agents

“We invite contributions from scholars, scientists, writers, and artists interested in exploring the role of fermentation and its agents across fields.”

I suspect I’m the only comics scholar to submit an abstract:

“Fermentation is a kind of decay or rot caused by microscopic organisms breaking down larger organic matter. Graphic novelist Linnea Sterte offers a new mythology for that process that radically alters the role of humans and challenges a wide range of fundamental narrative norms. Stages of Rot is set on an Earth-like world where impossibly massive whales swim weightlessly in an atmosphere far above a vegetation-less landscape. When a whale descends in death, the comparatively microscopic organisms waiting to break down its body are not yeast or bacteria, but humans, a whole culture predicated on such events. A mold- and mushroom-filled “forest without trees” blooms in the carcass landscape, the home of the next culture centuries later. It too is soon replaced by later evolutionary stages of lifeforms and civilizations, until the novel’s final protagonists rediscover the whale’s heart and reanimate the possibly divine being inside it. Despite its negative connotations, decay can be a beneficial transformation, understood as a mysterious and even ineffable process. Sterte’s story captures that transformative quality not just in its narrative events but in the deeper qualities of her storytelling. Sterte’s depiction is striking for its lack of words and therefore reliance on image sequences to communicate its complexities. Rather than merely illustrating the narrative, the artwork composes it. As a result, concepts that require verbal language are rendered irrelevant in the novel’s millennia-long scope. Words cannot capture the narrative’s literally ineffable meaning. Sterte’s application of the comics form is a unique visual translation of the inherently alien yet spiritual nature of transformative decay.”

I often post my paper slides without commentary, and in this case, that “ineffable” approach is thematically appropriate.

April 14, 2025

How not to ban a graphic (but not sexually graphic) novel

The Washington and Lee Law School’s Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice hosted its 2025 symposium, “Conflict in the Classroom and Beyond,” last month. When a member of the “Classroom Censorship and Book Bans” panel dropped out, I was asked to step in. I’m no expert, but I was one of several community members who opposed an attempt at our local middle school to ban a set of books from its library. I was asked on a Wednesday to prepare a 15-20 minute presentation for that Friday, which, because it’s me, also meant assembling an improbably fast-paced 35-image slideshow. Turns out the panel was a roundtable of moderated questions with no individual presentations. Since the miscommunication left me with an unpresented presentation, I’ve uploaded the slides here.

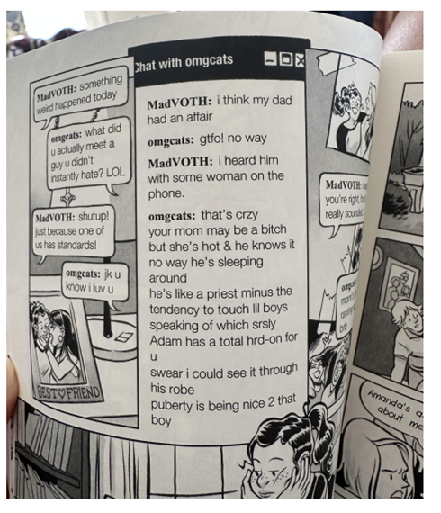

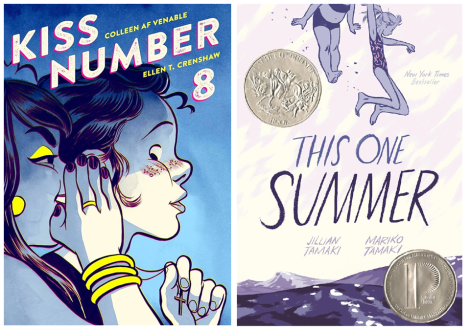

The attempted book ban started in September 2023 and concluded in early 2024. It included two graphic novels. One was already on my shelf, and the other I ordered and read.

This may have surprised me more than it should have, but based on what I could glean from public statements, none of the dozens of individuals who spoke in favor of banning had read either of the graphic novels.

I’m guessing Kiss Number 8 was initially targeted because it appears on lists of books banned elsewhere.

It is especially galling that Kiss Number 8 would be targetted as “anti-Christian” since the author intended the opposite:

You don’t have to read the novel to know that.

The protagonist is holding a cross on the cover:

If you read the front flap, you would know it’s about a teen named Mads who “is pretty happy with her life. She goes to church with her family and minor league baseball games with her dad.”

If you read the novel, you would know the church-going is shown early and often, including near the end, when her problems are at their worst. She never stops going to church. Though she’s angry with her mother early on, by the end they have grown close, and they attend church together through every phase. Church is portrayed as an unquestioned positive constant in her life.

But that didn’t stop a local non-reader from writing and distributing a misinformed and misleading three-page letter:

Some highlights:

The novel is over 300 pages. The letter included photos of two:

In the first, one of Mads’ friends, Cat, says she has “the hots for THAT SCULPTURE of Jesus.” Mads responds: “Ewwwwwww.” We are supposed to be grossed-out too. Readers identify with Mads, the narrator, not with Cat, someone just now being introduced. Cat is the most sexualized character, pressuring Mads not to be “prudish” and typing the other bit of dialogue included in the letter. Cat is also the most anti-gay character. When Mads’ bisexuality is revealed, Cat literally vomits, and the two never speak again.

Cat is the villain, a model of how NOT to be. But you would have to read the novel to know that.

Our local Republican party amplified the letter-writer’s call to action, adding more titles to the ban list, including This One Summer by Jullian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki.

I’ve taught two other Tamaki graphic novels, but not this one.

Again, I assume the book-banners targetted it based on seeing it targetted elsewhere:

I found out about all of this through a local activist organization I helped to co-found back in 2016.

Fighting the ban was a group effort, and having a network in place was key.

My part included: writing emails to the members of the Lexington School Board; writing letters-to-the-editor of the Lexington News-Gazette and Rockbridge Advocate; speaking at three school board meetings; and encouraging others to attend, speak, and write too:

I get absolutely zero credit for the Freedom of Information request that required the school to turn over all documents related to any of the books.

But I did study the documents afterward, including texts between two administrators:

Based on that text, the administrators never read Kiss Number 8 before removing it. This violated established school policy:

There was no committee. There wasn’t even a review. The administrators only read the misinformed and misleading letter of complaint.

They also relied heavily on a misleading phrase:

The term appears in other documents, including a list of supposedly “Sexually Explicit” library books:

And on a document stating that “Sexually Explicit” materials are labeled with YA stickers:

Here’s the logic problem.

While it’s true that “Young Adult” means “mature content,” and while it’s true that anything “sexually explicit” would be “mature content,” it is not true that anything “Young Adult” is therefore “sexually explicit.”

And yet when the administrator was interviewed by local reporters, she called the books “sexually explicit,” which is how the phrase ended up in headlines:

Though the focus was initially on Kiss Number 8, the FOIA request revealed that This One Summer was discussed similarly. An anonymous reader filled out a complaint form:

Since the writer called the material “R-rated,” here’s a quick detour to film rating standards:

Personally, I would say This One Summer is PG and Kiss Number 8 is PG-13. Neither is R because neither is sexually explicit.

Claiming either is sexually explicit also violated school policy:

Though the school policy document did not actually provide a definition, looking up the referenced line of state criminal code produces one:

I think the first and last items on the list are pretty clear, but the middle three need further clarification, which the next referenced line of code provides:

None of that describes Kiss Number 8. Here’s the novel’s most explicitly sexual scene:

And here’s the closest the novel gets to a sex scene:

Turn the page, and the next panel leaps forward in time to the protagonist getting dressed. The sex scene is implicit (it’s clearly implied) and so not sexually explicit. (Not a single person speaking in favor of banning Kiss Number 8 referenced this scene, presumably because they didn’t know it existed.)

I would do the same kind of analysis for This One Summer, but there’s nothing to analyze. No sex acts of any kind, implicit or otherwise, occur during the span of the narrative.

Therefore:

But all of that is just a long preamble required by the misleading use of the phrase “sexually explicit.”

Once the false claim is removed, a core question remains:

In other words, just because something is NOT sexually explicit doesn’t mean that it is approriate for a school library.

However:

What age range does the publisher of This One Summer identify?

There are many highly reputable book reviewers, and Kirkus is high on the list.

What age range do they identify?

Maybe the publisher was trying to widen its consumer base by a year? Whatever the intent, I would default to 13.

The same company published Kiss Number 8:

But in this case, it’s the reviewer that lowers the age by a year:

But whether starting at 12, 13, or 14, the age range suits what the administration identified as appropriate for its middle school library:

Now if only there were some way for a library to separate books written for young teens so that pre-teens wouldn’t be able to access them.

How about a sticker, database, and a form that parents can fill out if they don’t want their children to access those materials regardless of age?

In other words, if you leave the library exactly as it was before the attempted book ban, no problem exists.

Which is roughly what the Lexington City School Board did.

That was early 2024, and though I haven’t looked recently, I believe both graphic novels are currently on the shelves.

April 7, 2025

Concluding Race

First, some very happy news: my next book, The Color of Paper: Representing Race in the Comics Medium, has been accepted for publication.

The external readers had some very nice things to say:

“The Color of Paper is unique and groundbreaking in its efforts to link literal whiteness on the page to metaphoric Whiteness, focusing readers’ attention to the relationship between race, paper, ink, color, and text.”

Also:

“It will be a highly influential contribution to Comics Studies and Whiteness Studies.”

And:

“Gavaler draws on a diverse and broad group of scholars, thinkers, artists, and theorists. He is particularly skilled at breaking down theoretical concepts and demonstrating how they strengthen our reading and understanding of race in comics.”

And, what the hell, one more:

“Gavaler has admirable fluency, shifting between theoretical grounding, historical context, deep close reading, and adept analysis. The writing is both sophisticated and accessible, appropriate for undergraduates, graduate students, and advanced scholars.”

But the external readers did note one significant flaw:

“I do think that a stronger conclusion does need to be included.”

In this case “a stronger conclusion” is a polite euphemism for “any conclusion whatsoever,” since the version of the book I submitted ends with its final chapter and without the slightest gesture toward a culminating statement.

I think I needed to get the rest of the book fully in place before attempting a summary, but it is a little funny since in the version prior to this one, I wrote a peculiarly inept introduction (I later shared the opening of the much-improved version here). It seems I have trouble with doors: stepping in and stepping out. I seem reasonably capable while hanging out inside a room, so I hope it’s just a matter of cutting the right hole in the wall to guide readers in and out.

Summarizing the takeaways of The Color of Paper took me a long weekend and about 2,500 words, more than I’m going to post here, but I would like to share the final portion. As I was drafting the last paragraph, I remembered I had the perfect image to illustrate the ideas. I had it because it used to be the very first image in the manuscript — which I cut while revising the introduction because it was a part of my door problem. Beginning with a 1955 painting by an abstract expressionist is not a good way to signal a focus on the comics medium. I happily cut it. But I also happily added it to the end of the conclusion where a gesture out toward other media feels appropriate.

Or so I hope.

Here’s a draft of the last third of the conclusion:

Because black-and-white images tend to be black marks printed on white surfaces, they also highlight The Color of Paper’s second question: How does whiteness relate to Whiteness?

Though hatched and crosshatched areas produce various gray effects, the marks in black-and-white art are black ink spaced to optically combine with the white of a paper surface. Black ink (or less often a black surface) can represent skin (and has in the racist blackface minstrel tradition), but the dominant norm in and outside of the comics medium is for an unmarked and paradigmatically white surface to represent the skin of characters of all racial categories. That paradoxical range is possible because, rather than linguistically reading or spatiotemporally observing, viewers ignore paper color. They therefore typically treat the color of a page as meaningless when assessing the race of a drawn character.

The expectation that skin represented by white paper would be perceived as White skin reveals the illogic of racial categorizations. Viewers do not perceive white skin as White skin because White is not white. A more logical (though not necessarily accurate) assumption is that skin represented by beige paper would be perceived as White skin. The logical expectation is blocked and the illogical expectation is highlighted, because U.S. racial categorizations are grounded in an ink-on-paper metaphor that produces false racial binaries through the double visual dichotomies of white/black and white/color.

Because race is not a coherent concept, racial thinking appropriates and misapplies the materiality of black-on-white print and colors-on-white art to construct the illusion of coherence. The whiteness of paper allows black and color marks to be legible, and since white marks would be illegible, the interiors of white objects are represented by the negative spaces of unmarked paper. Racial illogic extends and combines that dual quality of whiteness to Whiteness: it is both one race among multiple races (just as white is one color among multiple colors visible on a page), and it is also the ubiquitous background necessary to make the concept of race legible. Because white requires no addition of marks, it is the unmarked default state of the page, which metaphorically naturalizes Whiteness as the unmarked default state of humanity which other races mar or obscure.

Though viewers do not interpret white paper visible in areas representing skin as White skin, the conflations of whiteness and Whiteness reverberate through a medium developed and still partially dependent on white paper. While not required, the negative spaces between images are the most pervasive device for structuring image-text relationships in the comics medium and perhaps print culture generally. The white frames of gutters produced by the absence of marks evoke Whiteness as a larger social system framing and controlling all other cultural content. Because paper may be perceived as outside authorial choice and so paradoxically not a part of works that exist only when printed on its surface, the color of paper is perceptually neutral. It is as if works exist in an ideal state where ink is printed on invisible surfaces. Because neutrality and invisibility are connotatively aligned with Whiteness, these deeper structuring qualities of whiteness further structure racial thinking. Whiteness partitions and juxtaposes other cultural elements in relationship to itself and within its all-encompassing frame. By misapplying the norms of ink-on-paper visual works, U.S. culture functions as a White page.

Previous illustrations included in The Color of Paper are representational images, most of or including faces. For a final example visualizing how whiteness and Whiteness relate, consider abstract expressionist Franz Kline’s 1955 black-and-white painting Untitled. The work hangs in the Virginia Museum of Fine Art, where curators include a statement by the artist on an accompanying plaque: “People sometimes think I take a white canvas and paint a black sign on it, but this is not true. I paint the white as well as the black, and the white is just as important.” Though a small portion of Kline’s beige canvas appears visible along its top edge, the misimpression is reinforced by the gallery wall surrounding the minimally framed painting. The seemingly unpainted white canvas of Untitled appears to be continuous with the white of the wall, expanding and reinforcing the illusion that the black marks are the only added marks, including to the white, black-lettered plaque beside it.

Untitled illustrates Whiteness.

March 31, 2025

Another United States

A version of this commentary ran in the Richmond Times-Dispatch last Tuesday as “editor’s pick” and “top story.”

When Donald Trump took office, he swore to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution.” The oath is essential, because the Constitution defines the United States, and the United States does not exist without it.

Another country called the “United States” existed for the decade following the Revolutionary War, but it resembled NATO more than a nation. Its constitution created a “league of friendship” between the former colonies “to assist each, against all … attacks made upon them, or any of them.”

That league was replaced by the United States as created by the U.S. Constitution. Its first president was George Washington – not John Hanson, the forgotten first president of that other “United States.”

The current president of the United States is Donald Trump. It is my profound hope that he will not be the last.

U.S. presidents testing the limits of their constitutional power spans the history of the office.

When President Obama issued a 2014 executive order deferring the deportation of undocumented immigrants who are parents of citizens, several states sued, claiming the order violated the Take Care clause of the Constitution. The courts stayed the order, preventing it from being implemented while the cases were heard. Whether the order was unconstitutional was never officially determined, because the Trump administration rescinded it in 2017.

In addition to passing legislation, holding hearings, and, in extreme cases, impeaching and convicting, Congress can reject anti-democratic bills that a president demands, as President Roosevelt’s party did when he tried to undermine the Supreme Court by adding six new appointees. The Democrat-controlled Senate Judiciary Committee responded: “The bill is an invasion of judicial power such as has never before been attempted in this country.”

Roosevelt served four terms, which violated precedent but not the Constitution. The 22nd Amendment created the two-term limit after his death.

Lawsuits, hearings, impeachment, legislation, amendments – these are the Constitution’s checks and balances on a president. What happens when a president takes unconstitutional actions and Congress does nothing?

President Trump issued an executive order contradicting the Supreme Court’s 2020 Bostock decision, which recognizes trans people by their gender identity and their preferred names and pronouns.

President Trump issued an executive order contradicting the birthright citizenship clause of the Constitution’s 14th Amendment and preventing newborn citizens from receiving social security numbers.

President Trump issued an executive order declaring diversity, equity, and inclusion “illegal,” a power specific to Congress and a violation of the 1st Amendment’s free speech clause.

President Trump created DOGE, an all-encompassing department not recognized by Congress, and appointed Elon Musk to head it without Senate confirmation, violations of the Constitution’s Appointments clause.

President Trump has closed multiple programs, including the entire Department of Education, mandated by Congress and halted funding appropriated by Congress, violations of the Constitution’s Take Care clause.

President Trump’s Department of Justice dropped a corruption and bribery case against the mayor of New York in exchange for his cooperation with deportations, itself an act of corruption and bribery.

President Trump has halted election security programs combatting Russian interference while normalizing relations with Russia’s dictator, actions short of “treason” as defined by the Constitution but that also overtly weaken U.S. elections.

The Trump administration has detained with the intent to deport legal residents who protested the killing of Palestinians, violations of the 1st Amendment’s free speech and the 5th Amendment’s due process.

President Trump is the only president not to concede election defeat, and he has repeated his intention of having a third term. Stephen Bannon was correct when he told CPAC: “A man like Trump comes along only once or twice in a country’s history.”

States and citizens have responded with over 130 lawsuits, with multiple stays issued against Trump’s orders and actions. But the courts are slow and have no means to force the executive branch to obey their rulings. The possibility did not occur to the authors of the Constitution when they created the United States.

Though oversight hearings and the consideration of articles of impeachment are constitutionally required, the GOP-controlled Congress has done nothing, and many of its members are instead undermining the courts by joining the Trump administration’s verbal attacks against the courts. They are also advancing new legislation to curtail the scope of lower court injunctions.

Since taking office, President Trump has declared seven national emergencies, each expanding his executive power. The House responded by eliminating its own power to revoke emergencies.

Midterm elections are nearly two years away.

In 1933, Germany’s congress passed a law giving legislative power to the executive branch, converting their democracy to a dictatorship. The name “Germany” remained.

In The Handmaid’s Tale, Canadian author Margaret Atwood imagined the United States government killed in a terrorist bombing and a new nation emerging in the aftermath. Most Americans didn’t realize until they noticed soldiers wearing uniforms with an unfamiliar flag.

Atwood was naïve. Gilead wouldn’t make a new flag. It wouldn’t even change its name. Gilead would call itself the “United States.”

March 24, 2025

Beyond Bullshit: Donald Trump’s Philosophy of Language

Nathaniel Goldberg and I wrote this short essay in December 2016, and Philosophy Now published it in 2017. Rereading, it seems little if anything has changed — except of course the scope keeps widening and widening. In short, Trump is a master of lying because he doesn’t lie. He systematically miscommunicates.

In 2005, philosopher Harry Frankfurt published a charming little book called “On Bullshit.” In it, Frankfurt distinguishes bullshit from humbug and lies.

Donald Trump, we submit, isn’t (usually) a humbugger or a liar. He’s a bullshitter. But he extends the qualities of bullshit beyond Frankfurt’s definition.

“Frankfurt gives an example of humbug:

“Consider a Fourth of July orator, who goes on bombastically about our great and blessed country, whose Founding-Fathers under divine guidance created a new beginning for mankind. This is surely humbug.”

Frankfurt explains that the orator isn’t lying:

“He would be lying only if it were his intention to bring about in his audience beliefs which he himself regards as false, concerning such matters as whether our country is great, whether it is blessed, whether the Founders had divine guidance, and whether what they did was in fact to create a new beginning for mankind. But the orator does not really care what his audience thinks about the Founding Fathers, or about the role of the deity in our country’s history, or the like…. He is not trying to deceive anyone concerning American history. What he cares about is what people think of him.”

Trump has also talked about the greatness of America’s past. Yet Trump’s statements aren’t humbug. He’s not in it only for self-aggrandizement, like Frankfurt’s orator. He’s trying to say something about America. Nor is Trump’s intention to bring about in his audience beliefs which he himself regards as false. Trump might really think that America was and will again be great. So he isn’t lying, either. Instead, Trump is bullshitting.

What’s bullshit?

Frankfurt considers an anecdote in which philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein chides his friend Pascal for saying “I feel just like a dog that has been run over.” According to Wittgenstein, Pascal doesn’t know how that would feel. “Her fault,” Frankfurt elaborates, “is not that she fails to get things right, but that she is not even trying.” Wittgenstein, Frankfurt contends,

“construes her as engaged in an activity to which the distinction between what is true and what is false is crucial, and yet as taking no interest in whether what she says is true or false…. That is why she cannot be regarded as lying; for she does not presume that she knows the truth, and therefore she cannot be deliberately promulgating a proposition that she presumes to be false: Her statement is grounded neither in a belief that it is true nor, as a lie must be, in a belief that it is not true.”

Frankfurt concludes: “It is just this lack of connection to a concern with truth—this indifference to how things really are—that I regard as of the essence of bullshit.”

Trump is a lot like Pascal.

After the heating and cooling giant Carrier announced it would keep jobs in Indiana due to tax incentives, Trump described watching an interview with a Carrier employee. The Washington Post quoted Trump describing the employee: “He said something to the effect, ‘No we’re not leaving, because Donald Trump promised us that we’re not leaving.”

Trump, however, added:

“I never thought I made that promise—not with Carrier. I made it for everybody else. I didn’t make it really for Carrier. And I said, “What’s he saying?” And they played my statement. I said, “Carrier will never leave.” But that was a euphemism. I was talking about Carrier, like all other companies from here on in. Because they made the decision a year and a half ago. But he believed that that was—and I could understand it.”

Aaron Blake, who included Trump’s quote in an opinion piece in the Post, rejoined:

“You can make an argument that Trump was perhaps speaking more generally and using Carrier as an example of the type of company that would no longer be leaving under his presidency.”

If so, Trump was employing a synecdoche, a part used to refer to the whole. “Carrier” meant all U.S. manufacturers. Except Trump meant “everybody else” except Carrier.

Blake continued:

“But this is a statement he made while in Indiana—in front of people who had a very strong interest in taking him literally. They did, and yet he was apparently surprised by that. Any studied politician would know that if you are in Indiana and you say Carrier won’t leave, you had better mean those exact words.”

By “exact words,” Blake is getting at what philosopher H. Paul Grice calls implicature. Speakers implicate, or communicate, the meaning of their words in one of two ways: conventionally, by the words themselves, or conversationally, by words plus context. Both require speakers and audience working together. All communication follows the Cooperative Principle:

“Make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged.”

Grice divides the Principle into four maxims:

Quantity: Make your contribution as, but only as, informative as required.

Quality: Try to make your contribution true.

Relation: Be relevant.

Manner: Be perspicuous by avoiding obscurity and ambiguity, and by striving for brevity and order.

Speakers routinely flout those maxims, which is part of Grice’s point. Flouting a maxim conventionally indicates that a speaker’s communicating conversationally. If I ask whether you had a good Thanksgiving, and you reply, “Beautiful weather we’re having!” you’re flouting (at least) Relation. Today’s weather isn’t relevant to my question. Taken conversationally, however, what you said makes communicative sense. Your Thanksgiving wasn’t good.

Does Trump follow the Cooperative Principle? According to journalist Salena Zito, “his supporters take him seriously, but not literally.” If so, Trump flouts maxims conventionally to communicate conversationally.

He flouted Quantity. Saying “Carrier” when he meant every U.S. heating/cooling giant besides Carrier gave his audience too little information. He flouted Relation. “Carrier” isn’t relevant to companies other than Carrier. He flouted Manner—embracing rather than avoiding obscurity and ambiguity.

And Quality?

If by “Carrier” Trump genuinely meant everyone except Carrier, he did try to make his contribution true. He just flouted the other maxims. But if by “Carrier” Trump meant what everyone took him to mean—namely, Carrier—he didn’t try to make his contribution true. Yet he didn’t lie, since he didn’t mean to deceive. Trump just said something that felt right at the time. He wasn’t concerned with the truth of what he was saying at all.

That’s the essence of bullshit.

But Trump one-ups Frankfurt’s notion. While Trump wasn’t concerned with the truth, and his intent wasn’t to deceive, he nevertheless was concerned with what his audience thought. He wanted people in Indiana to think he was going to make America great again, whether or not Carrier—or everyone except Carrier—had anything to do with it. Yet it’s hard to see what could have conversationally clued his audience into this meaning. As Blake observes, many in Indiana weren’t.

By flouting all of Grice’s maxims conventionally, and not clearly communicating conversationally, Trump wasn’t communicating with his audience so much as talking at them. His speech was governed by what we might call the Anti-Cooperative Principle:

“Make your conversational contribution seem such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged, even though it’s not.”

That’s beyond bullshit.

March 17, 2025

How is Trump destroying the Constitution? (A Survey of Political Cartoons)

Political cartoonists make their living on visual metaphors. How many different ways can you draw Donald Trump destroying the document he swore an oath to preserve, protect, and defend? Let’s start by narrowing it to four:

Trump _______________ the Constitution.

a) shreds

b) burns

c) urinates/defecates on

d) draws on

e) all of the above

The correct answer of course is “all of the above,” but the most repeated of the single responses is “shreds.” Thirteen cartoonists have drawn Trump ripping, scissoring, knifing, or paper-shredding the U.S. Constitution.

The second most repeated answer is “burns” (11 times).

Toilet references come in third (9 times).

And a respectful fourth place goes to “draw on” (6 times).

There are a dozen more, but aside from shooting the Consitution, all of the others are single occurances.

In total, I found 43 political cartoons depicting Donald Trump harming the Constitution.

I defy anyone to find half as many images of any other U.S. president doing anything like this.

Why do you think that is?

And do you think future generations will look back at 2025 and say, “I guess they didn’t realize”?

March 10, 2025

the right to remain silent

I made these images during Trump’s first term, documenting his actions and the protests against them.

Eight appeared as “the right of the people peaceably to assemble” on Empty Mirror in 2019.

I wrote then:

“The image-text sequence combines digitally manipulated photography, graphic design, and found language in a hybrid form that suits the technical definition of comics while violating comics’ conventions and connotations. The eight-piece sequence is part of a larger book-length project, Words Fail.”

I never finished that book, which combined the country’s political descent with my mother’s descent into Alzheimer’s.

Another six appeared as “American Descent” on Scoundrel Time in October 2019.

I wrote then:

“’American Descent’ began with images of Trump descending stairs: the elevator in Trump Plaza when he declared his candidacy (which didn’t end up in the final sequence); the bus steps when he was being recorded for Hollywood Access; stage steps after one of his rallies; and finally the mobile steps outside of Air Force One. I had Duchamp in mind too, and thought of Trump as embodying a kind of ultimate nakedness. The descent was initially infernal and encompassed all of America, but now that last image of him fading into nothingness might be prophetic of his leaving office.

“I was also working separately on a set of image-texts that explored his sexual scandals, and ended up combining the two sequences. Trump’s face is visible through the repeated figures of the women he denies having sex with, except for the first page, which references his relationship with Russia.”

I’m now combining the fourteen images into this current sequence, “the right to remain silent,” adding one unpublished image from a fourth sequence, “Classified & Redacted.”

Together they are a reminder of Trump’s first term and a renewed protest against his second.

Chris Gavaler's Blog

- Chris Gavaler's profile

- 3 followers