Raph Koster's Blog, page 10

July 15, 2015

MMORPG.com interview

Wherein I whine in a most entitled way about people who want me to make games for them:

Something like 95% of the games I’ve done over the last 20 years has never been seen by the public at all. Puzzle games have been a key part of what I’ve done for a decade and a half, and only two of them were visible on Metaplace for a little while. Most players don’t know that has been a passion of mine for a long time and always has been a part of what I do. There just hasn’t been a way for them to get to market. So, sure, people think “this is what that person does,” but it’s because, well, that’s what happened to make it out the door. And MMOs happen to be what I was lucky enough to get paid to make…

Being 100% beholden to an audience and doing only what they expect of you can feel like a straitjacket…

June 30, 2015

Games affecting people

This comes up, especially in relation to questions about free speech. It comes up, in terms of working with compulsion loops some might term addictive. It comes, in terms of whether or not game designers worry about what they do.

The most common answer is “no,” likely because it’s an uncomfortable question people would rather not think about, or one that positions games as somehow an implicitly risky medium and vulnerable to censorship, or because of a disclaimer of responsibility embodied in the notion that we’re just providing entertainment and anything past that is the player’s problem. Sometimes there’s an implicit idea that mere entertainment cannot have any effect.

So do designers worry?

Yes. I have, personally.

When working on Ultima Online, it was an active concern of mine. I had seen many players of MUDs get hooked on them to the exclusion of studies, or watched them damage their real life personal relationships while favoring the virtual ones.

When we reached the point of a much larger market with UO, I worried that the same things would happen, and further, that we were failing to model human society well enough to encourage good behavior towards one another. I worried that we were building virtual societies that taught people to take advantage of one another, to dehumanize one another, and to engage in antisocial practices.

Based on the research I did, I ended up concluding the following:

The people who were getting hooked on online games were finding them meeting a need that they weren’t meeting elsewhere. To pick the commonest example, people whose social needs for basic human contact weren’t being met in meatspace, and who therefore sought friendships in MUD/MMO space. In this sense, the participation was basically therapeutic, and was often even vital to their happiness or survival. It is no accident that early MUDs and MUSHes were so often safe spaces for a variety of people whose real lives were difficult. There is an enormous body of literature of the use of alternate genders in virtual spaces, for example.

That there was some proportion of people who got hooked because they were susceptible to getting hooked on things, period, and that there wasn’t much that could be done about it.

That mentally, the notion of “telepresence” and a variety of aspects of how our senses function means that players will take interactions in a virtual space as “real,” including having involuntary emotional reactions to things like abuse, violence, affection, and really, any other human interaction. Some people are able to distance themselves from this, but many more will simply treat the game as mediating the experience, like any other channel of communication. In other words, just as people can hurt one another, or fall in love, over the phone or with the written word, they can hurt one another or fall in love via a game.

That periods of “addiction” to virtual spaces, or at the least, intense involvement in them, often seemed to have a standard lifecycle: a couple of years, then naturally over as people “graduated” from the hobby altogether. This may be attributable to Dr. Richard Bartle’s theory that virtual worlds are about learning about oneself, about self-actualization in a sense. Learn enough, and you move on.

That games, like any other medium, are capable of teaching behavior, moral lessons, and patterns to emulate. In this, they are no different than anything else. If a game portrays violence as the proper solution to problems, it is providing the same sort of moral lessons as a book or film that argues that violence is the proper solution to a problem. We have used stories as a means of teaching lessons for millenia, and there’s every indication that they work.

Further, unlike most media, games do have an entraining component, whereby reflexes can be conditioned. These reflexes are not only physical, but are also mental reflexes, the building of intuition through accreted knowledge. This has been explored in books such as Sources of Power and Thinking Fast and Slow. This entraining component is powerful (it “rewires brains” just like other forms of learning do), is sometimes hard to see (because we do not think about the decisions it leads us to logically, that’s the whole point), and in designing a game we are creating learning patterns in players whether we mean to or not.

So, my conclusion was that creators of games are correct to worry. But not in the sense that “games are bad for you.” Instead, in the following ways:

be aware, if creating an immersive virtual space, that some substantial proportion of your audience is using it as a theurapeutic tool when in difficult circumstances. Think about what sort of people these are, and how your design affects them. Think about the ways in which your design will be misused, and the ways in which it may impact a player emotionally.

realize that you are creating and moderating a channel of communication and a venue of interaction, and that therefore you have an awesome and large-scale responsibility, not dissimilar to the burden carried in terms of liability of those who operate public venues, not dissmilar to the post office’s ethical emphasis on privacy, not dissimilar to the role of a government who should work towards the welfare of its citizens.

be aware that you are in part a storyteller, and stories have always had an aspect of shaping their viewers and readers. You encode morality into your stories, almost inevitably, and it is quite possible to do well or do poorly, and there’s plenty to learn on the subject.

know in your bones that game design is a powerful way of imprinting behaviors on people, and that it is entirely possible to imprint behaviors you didn’t want. Just as you can train a firefighter’s instincts through fire drills, just as you can train a people to grow up racist, you can train players to react in certain ways to certain situations. Games are always pretty abstracted from reality, so this training may not be happening in at all the ways you think it is. But it is always happening. Games teach, and you are teaching something.

In the end, sure, games might well ruin someone’s life, but not much more so than a book might (depending on your philosophical bent, consider Ayn Rand, or the Bible, or Mein Kampf!), or an all-consuming hobby. But in the end, they can also hugely improve a life. So like any tool, like any cultural artifact, their virtue lies not in themselves but in what the medium is used for. That’s an awesome responsibility —

— but also an utterly quotidian one. The same one faced by any writer, any playwright, any musician, any theme park designer, any architect, any musician, any painter, any coursework designer, any…

Saying games can’t affect people is to denigrate them. It is to call them lesser. They are not lesser. And that means it is proper to worry. And also to work in them anyway. There isn’t anything worth doing that doesn’t carry the risk of ruining someone’s life in some way. It’s called “making a difference.”

June 29, 2015

Game design vs UX design

Short form: UX design is about removing problems from the user. Game design is about giving problems to the user.

In both cases you look at users’ cognitive reasoning and process capacity. And these days, we have UX designers on game teams, and they are incredibly valuable. But they are in a different discipline from game design.

Most UX designers don’t work in games. They work in website design or application software. They focus almost entirely on interfaces. In general, a UX designer’s job is to create a great experience when using something for a purpose. They therefore do as much as possible to make the interface

transparent, so that the user needs to think as little as possible

affordant, so that the user knows what possibilities it offers

scalable, so that it unfolds as the user develops skills

feedback-rich, so that the user knows when they did something

constraining, so that the user can’t do things that get them in trouble

What they do not do is

actually specify the inner workings of whatever is being used. They are usually working to provide an experience to a system already designed by an engineer, or specifying an interface to a system that an engineer will then go design.

make interfaces revelatory of the inner workings of the tool. Usually, we don’t want you thinking too much about car guts or lexical parsers when driving or using a word processor.

UX design in non-game applications is absolutely not about teaching the player how the guts of the software works. It’s about getting them to build a mental model that helps them get their work done. Classic examples might be the steering wheel of a car, or the entire desktop metaphor. The steering wheel is actively hiding from the user the fact that there’s a pretty complex mechanism in between the wheel and the tires. It’s instead trying to get the user to think “turn the wheel, turn the car.” This is an intentional elision of most of the actual workings of the steering mechanism. Similarly, the desktop metaphor in operating systems is intentionally trying to hide quite a lot of stuff about how the file system actually works, in order to build a consistent skeumorphic metaphor in the user’s mind, one that ties back to known cognitive patterns and is therefore easily understood.

In general a game designer’s job is to create a great experience when playing a game. They therefore do as much as possible to make the game

challenging. Often, we want the game to make the user think a lot.

explorable. We usually want the user to think there are always more possibilities in there.

scalable, so that players learn better play as they play.

crazy juicy, so that players are captivated by spectacle, well beyond the needs of feedback from a UX perspective

inviting of error. We want players to learn through mistakes.

In addition, game designers

typically do specify the inner workings of what is being used — not just the interfaces, but data structures, algorithms, formulas, and so on (often indirectly; it may be the gameplay engineer who writes the technical spec). They are intentionally creating a problem-rich environment.

are trying very hard to make the game experience revelatory of some of the inner workings of the game. Where UX tries to provide a likely false but useful mental model of the interior workings to the user, game design tries to guide the player towards a fairly accurate mental model.

In general, these lines get blurry. We want the way to fire your gun in the wrong direction to be as transparent as possible, so in games we try to layer great UX design on top of something that is in fact the opposite.

In game design, you’re usually trying to give players an understanding of the “machine” inside the game system. Typically, you have an interface to the game system that does in fact follow traditional UX principles: for example, moving the mouse to the edge of the screen resulting in panning a camera. That’s pretty traditional UX for an RTS. But understanding things like the overall build rates of different types of structures, so that the player ends up mastering complex supply chains and dependencies — not only is that a piece of game system design, but the intent is to get the player to actually understand supply chains. A UX approach would hide supply chains (as in fact they are hidden from our shopping experience).

UX is about clarity that hides complexity, and game design is about clarity that teaches complexity.

These days, we see UX designers who work designing UX at the game systems level. Until game teams got big enough, that’s how all designers were.  The splitting off of UX as a separate discipline that an individual performs on a game team is a result of large teams. Originally, we just had “game developer.” As teams grew and specialization started occurring, first we got content designers, then UI designers, and now we have UX designers. (I remember when designers at Origin were just called “technical design assistants.”)

The splitting off of UX as a separate discipline that an individual performs on a game team is a result of large teams. Originally, we just had “game developer.” As teams grew and specialization started occurring, first we got content designers, then UI designers, and now we have UX designers. (I remember when designers at Origin were just called “technical design assistants.”)

Historically, though, ownership of the overall UX has fallen to whoever the game’s “director” is, who ideally is someone who has a solid grasp of every subdiscipline in the game design field; enough to manage people who are more expert than they, anyway.

June 22, 2015

Games vs Sports

From a game design “formalist” point of view, they are not different. A rules-centric view of games doesn’t care whether the interface is computerized, mediated via apparatus, or physical, so it makes no distinction between computer chess and physical chess; similarly, it makes no distinction between the rules of, say, baseball, implemented within a computer or by players on a field. They’re both still recognizably baseball. You can diagram them; you can port the higher level rules between media; you can implement even a phsyical version with a ruleset that requires everyone to play on their knees, or in wheelchairs.

From a game design “formalist” point of view, they are not different. A rules-centric view of games doesn’t care whether the interface is computerized, mediated via apparatus, or physical, so it makes no distinction between computer chess and physical chess; similarly, it makes no distinction between the rules of, say, baseball, implemented within a computer or by players on a field. They’re both still recognizably baseball. You can diagram them; you can port the higher level rules between media; you can implement even a phsyical version with a ruleset that requires everyone to play on their knees, or in wheelchairs.

The major distinction arises with subgames and interfaces present within the rules. For example, baseball-the-sport makes use of extensive implementations of physics, thanks to the real world providing a very robust physics engine. It also has a very rich set of subgames regarding mastering the controls of the human physical body. Computerized baseball is relatively limited on that front, mostly requiring mastery of just your hands as they manipulate the controller.

Sports historically refers to physical games, but of course even many non-sport games have large physical components involving either strength or dexterity. Many children’s games, such as jacks and tiddlywinks immediately come to mind (not that jacks was always a children’s game…).

Similarly, many apparently physical sports are heavily mediated by technological objects. At the highest end perhaps are various forms of car racing, but it’s a sliding scale downwards from there through bicycling, golfing, tennis, the effect of swimsuits or sneakers on physical capabilities, and so on down to a true “naked” sport (of which there are actually very few).

Etymologically speaking, “sport” being associated with physical activity is a 500-year old usage tacked onto a 1000-year old word root. Like other such words (“fun” being an obvious one) it therefore has very fuzzy boundaries.

So, from a game designer’s point of view, they aren’t that different.

Some theorists use the competitive nature as a way to classify games that fit the description; under this definition, backgammon, Blokus, Monopoly, and Pong are sports. But better words exist for this sort of thing, such as “contest” up through “game” (used by Keith Burgun) or “orthogame” (used by Elias, Garfield, & Gutschera [affiliate link]). This is additionally complicated by the fact that it is remarkably easy to turn a non-competitive game into one simply by measuring players asynchronously (high score tables) or in parallel (as is done with footraces). It seems to have become clear that the broad swath of games that can serve as contests is quite large, and therefore, the commonest division is actually “toy” (lacking goals), “puzzle” (has one predetermined solution), and “game” or “contest” or whatever, which is “everything else.” (And by implication, admits of strategy, typically unitary goals, multiple solutions, etc).

So… your answer is not going to be found in game design theory. Instead, we have to leave formalism behind and look at people.

In cultural practice, sports has come to mean competitive games played in front of spectators. It’s hard to think of a sport that doesn’t involve spectation. Even sport fishing is about relative competitive measures of skill and prowess in an arbitrary ruleset, quite distinct from fishing for food. The practice of snapping pictures of the size of the catch reveals that spectation is the driving force there.

Conversely, it’s fairly easy to think of competitive games not played as a sport.

Once spectation is involved, so is money. And so a sport is most typically characterized by infrastructure: tiers of amateur to semipro to professional; training; regulating bodies; teams that fans can ascribe loyalty to, etc. Culturally, some contend that sports are effectively safety valves sublimating the impulse towards warfare, permitting tribal affiliations to express themselves in a safe way.

The acceptance of eSports is largely due to the fact that competitive play of first-person shooters and RTS games acquired fans, an audience, and then venues and broadcast television channels in South Korea. In the US, a similar path was followed by the fighting game community, or FGC, albeit with different access to mass media, followed by FPSes and now MOBAs. The audiences for League of Legends matches now number in the millions, quite comparable to physical sports, and athlete visas have been granted for competitors.

On the flip side, there are many physical games that are not treated as sports typically; ringing the bell at a carnival is one example, despite the fact that it is not that dissimilar to a weightlifting competition (consider the difference between this, and say, the caber toss or other folk sports). With the increasing nichification of mass media, there is room for more and more sorts of sport activities to arise, and we have seen the development of numerous new ones in the last few decades. Some have been driven by new technological apparatus (better roller skates enabled new sports; same with skateboards). Some have arisen out of non-sport competitions such as TV shows, and have gradually acquired the emphasis on training, expertise, and professionalism that characterizes a sport, such as the various Ninja Warrior competitions.

On the flip side, there are many physical games that are not treated as sports typically; ringing the bell at a carnival is one example, despite the fact that it is not that dissimilar to a weightlifting competition (consider the difference between this, and say, the caber toss or other folk sports). With the increasing nichification of mass media, there is room for more and more sorts of sport activities to arise, and we have seen the development of numerous new ones in the last few decades. Some have been driven by new technological apparatus (better roller skates enabled new sports; same with skateboards). Some have arisen out of non-sport competitions such as TV shows, and have gradually acquired the emphasis on training, expertise, and professionalism that characterizes a sport, such as the various Ninja Warrior competitions.

Bottom line: the difference between any old game and a sport is largely in whether the right cultural practices have accreted around it. This is largely driven by the right sort of cultural acceptance: ways to select champions as proxies with which we can measure the physical or mental prowess of groups.

Adapted from an answer on Quora.

June 11, 2015

Some thoughts on recent industry events

The FTC imposes a fine on a board game creator who failed to deliver their Kickstarter.

Developers publicly wring their hands about the reports of high refund rates on Steam.

Everyone looks to VR, but there’s already people asking whether it is a bubble.

What’s going on?

There are two business models: sell something in advance using promises, and persuade a lot of people who might not like a product a lot; or give the product cheaply and charge after the fact.

Here are some basic facts of life regarding these two models.

Selling in advance relies on persuading people who aren’t actually a great fit for the product that it is the best thing for them. This is the model that packaged goods have always used. The fact is that any given product is only perfect for a small percentage of its actual audience. Most of the others are more like 80% fits, or occasional users, or whatever. Few people need to buy a wood chipper; it’s smarter to rent one. Few people need to buy most things, actually.

The cheap to free model relies on the idea that you can give the product to a zillion people, and then get from them the amount of money they are actually willing to spend. It has the wonderful virtue that you get to extract small dollar amounts from people below the price sensitivity threshold of the packaged goods price. It has also revealed, in games anyway, that in practice, 95-99% of people think your game isn’t worth anything even if they play it every day. This model inevitably leads towards service businesses.

Of course, these two broad methods have a lot of gray area in between them. You have to sell people in advance on the idea of even trying your free product, for example. (If you want to learn more about how to “sell in advance” (which is also known as “marketing”) you can read this post of mine here.) Or, in the case of service businesses, we quickly find bundles and packages and service tiers, a way to sort of sneak in aspects of the packaged goods model into the other model. Either way, though, the pure fact is that capitalism often depends on getting people to pay for stuff they don’t really need.

To protect consumers, the “sell in advance” model typically offers refunds. However, refunds are often not available for goods which are consumed, easily copied, etc. It varies by jurisdiction. One doesn’t return a book, for example, because they didn’t like it. (There’s much chatter about Steam’s new policy being driven by the new EU rule on being able to “withdraw” from digital purchases within 14 days, but that’s actually a somewhat muddled thing and not as straightforward as “you can do refunds for 14 days, no questions asked.”)

The “sell for a price” business model learned over time that demos reduce sales. This may be because people find that they don’t like the game. It may also be because the typical player just doesn’t play a given game for very long. Metrics showed years ago that any AAA game longer than around eight hours was hugely overspending in content for the typical user, for example. This is why games started getting shorter.

Particularly narrative games, of course. Games with narrative have become, in aggregate, the largest segment of AAA. (Most all the FPS, action-adventure, and RPG categories are linear story games now, for a bunch of reasons which I recently wrote about).

As narrative games have grown, of course, some people have stories to tell that are by nature short. This is an artistic freedom thing, and also a response to changing markets that have, as technology has grown ubiquitous, made games accessible in really short sessions. One can debate pricing, of course, but…

In general, the industry has seen massive downwards price pressure. This pressure has hit mobile first, with the race to zero as the price point. The typical pay upfront game simply fails, period. Often regardless of quality, because the market is so glutted with free content that players don’t need to pay upfront for anything, really. At the same time, costs for quality, competitive content has risen as the market matures. (Costs at the low end haven’t, they’ve fallen. But basically, everything I wrote in this piece from ten years ago is still valid, and quite a lot of the predictions came true):

The cost to consumers for a minute of content has been dropping steadily over time

The cost to create and package a minute of content has been rising steadily over time.…If there’s one thing that the Web makes possible, it’s enough content to make the typical content creator superfluous. Oh, plenty of people will be willing to play, read, or hear their content. The question isn’t whether they can find an audience — on the Internet, everyone can find an audience. No, the question is whether all forms of fixed content will effectively be donations to the common weal.

(For a more modern summary of the same phenomenon, try this excellent article here.) One result of this price pressure is the move to free to play. Without it, the median mobile game makes zero in revenue. A game that would have cost anywhere from $15 to $60 not long ago, like say a puzzle game, is now free or 99 cents.

Steam has been a bastion of higher prices that actually pay for development costs. That said, it has also experienced downwards price pressure, though less. The Steam sale’s about to start. We all know how that goes. If Steam succumbs to the same trend as mobile, the only financially viable games will be the free to play ones and the genres that fit that model.

This is all a natural business evolution, and dev, pubs, and yes, players, are all complicit in it.

That said, the reason devs are worried by the refunds is because there are many verified reports of refunds being given for games played

for longer than two hours

for longer than two weeks

This might just be a shakedown period though. So there is a lot of wait and see going on. Reports between devs to date do in fact have lots of cases of 30% returns cited as a figure (which to be clear, is a recipe for bankruptcy), but there are also others saying they haven’t seen an impact.

Lastly, the concern about people demanding refunds for short games is a very real fear. Or for games that they just didn’t like. Refunds for disliking content as opposed to lack of functionality (like say, not working on your computer) is new territory for the industry as a whole. It definitely undermines the “upfront sale” model fairly dramatically if the percentage turns out to be more than a couple of percentage points.

A lot of devs do not want to move to free to play models. They see it as a far greater threat to ethical and creative game design than most anything else. So high refund rates combined with rapidly rising budgets and downwards price pressure raises a lot of fears about margins and sustainability.

For many, the way in which they thought they could evade this and go straight to the “thousand true fans” was to use Kickstarter. Kickstarter basically is a way to reach the (relatively few) people who do actually love your product idea, and do pre-sales on them so that you can build it in the first place rather than financing it out of pocket. All of the marketing costs remain intact. Basically, it means Kickstarter is strongly tilted towards “incumbents” of various stripes. Worse, we see some of the remaining “sell in advance” companies using Kickstarter as market validation before taking on publishing roles.

And of course, there’s that whole “risks” section. Kickstarter lets you pre-order so far in advance that the risk is always very high. It turns out that a lot of consumers don’t like these risks. The way-early reveals are basically showing the world how much gets cut from a typical game product, and all of a sudden it seems like you’re getting ripped off. In some cases, you might be.

So everyone turns their eyes towards a new step in the lifecycle: a new platform. Sure, plenty of people are excited by VR because of its promise in terms of creativity, immersion, and plain technological coolness. But… Just so we’re clear, we’re talking about a device that

requires a PC fewer and fewer people have, and can’t use the PCs most people are getting (laptops)

has a relatively high dev barrier to entry to make content that doesn’t cause actual physical illness

cannot run the sort of content the people who have high end PCs want (high-speed visceral content) because it causes actual physical illness

causes actual physical illness in an apparently irreducible substantial fraction of the population

is being marketed around a standing experience that has serious risk of serious bodily harm and requires a large empty space few consumers have

requires mass market adoption to succeed

is actually best experienced sitting down watching a movie

I think it’s fair to make the case that the message is muddled, and I say that as someone who is a believer in VR!

Two clearer messages:

“this is a high end luxury thing for core gamers with non-traditional tastes, and someday it will lead to something cooler.”

“This is a mass market device for the best movie-watching and virtual tour/visit experience EVAR.”

This article comparing VR to swimming pools was suggesting message #1. I think message #2 is probably more honest in some ways, but it of course alienates the early adopters who are driving the tech — and the path to the mass market lies through them.

In either case, though, it doesn’t look to me, at least, like the new platform is going to reset development costs by a large enough degree to make it a green field for low-end development.

So what happens in maturing markets? Well, smart distributors find ways to keep their top content providers hungry and their top charts varied by engaging in ever-heavier curatorial practices. Unsurprisingly, Apple just switched their App Store to a much more curated model. Curation has biases too: personal relationships, whatever favors the platform owner’s marketing story, high budget and polish.

So where does it leave us?

Refunds aren’t a bad thing. Devs are right to be concerned until there’s more data. Steam is probably watching their data very closely. The race to zero continues. The market value of entertainment continues to fall. A lot of small or midsize devs are going to fold or be bought. I don’t see a platform shift that saves the low end anytime soon. This also means now’s the right time to be building personal audience connections and the skills that go with it. And to learn to run very lean. Or alternatively, to go pile up large buckets of money from some source and shoot bigger: right now, money can be had, for the right dream. Oh, and master the service skills, because the sell-in-advance model is looking sickly. And the marketing skills, so you can persuade the curators you are worthy, because we are basically back to an editorially controlled world.

It’s easy to read change as negative. But change is change. If anything, the new landscape probably makes many folks who are more comfortable in the big business side of things very happy, just because it’s a familiar landscape.

June 4, 2015

Online Game Pioneers at Work

If you are interested in online game history, you probably want to check out Online Game Pioneers at Work

If you are interested in online game history, you probably want to check out Online Game Pioneers at Work . Morgan Ramsay managed to corner a whole bunch of people who were key figures in online game development over the last several decades, and interviewed all of us at great length. It’s a follow-up to his earlier book Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play

. Morgan Ramsay managed to corner a whole bunch of people who were key figures in online game development over the last several decades, and interviewed all of us at great length. It’s a follow-up to his earlier book Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play .

.

Among the people in the book:

Emily Greer telling the story of Kongregate

Victor Kislyi explaining how World of Tanks came to be

The entire incredible story of Richard Garriott

John Romero and the birth of the online FPS

Jason Kapalka explaining how PopCap was built

Ian Bogost being, well, Ian

And way more… Funcom, Supercell, CCP, King, ng:moco… with a foreword by Dr Richard Bartle.

My own chapter starts clear back with MUDs, and goes up through departing Disney, including the business saga of Metaplace. The book has an emphasis on the business side of things, more so than the design side, so it often gets into telling the nitty-gritty stories of how companies get built and manage to stay alive.

Here’s the book blurb and contents:

In this groundbreaking collection of 15 interviews, successful founders of entertainment software companies reflect on their challenges and how they survived. You will learn of the strategies, the sacrifices, the long hours, the commitment, and the dedication to quality that led to their successes but also of the toll that this incredibly competitive market has on even its most brilliant minds. For the hundreds of thousands of game developers out there, this is a must read survival guide. For those who simply enjoy games and know of some of these founders, this will be a most interesting read.

Foreword by Richard Bartle, co-author of MUD;

David Perry, cofounder of Shiny Entertainment and Gaikai;

Emily Greer, cofounder of Kongregate;

Doug Whatley, cofounder of BreakAway Games;

Ian Bogost, cofounder of Persuasive Games;

Victor Kislyi, founder of Wargaming;

Richard Garriott, cofounder of Origin Systems, Destination Games, and Portalarium;

Gaute Godager, cofounder of Funcom;

Ilkka Paananen, cofounder of Sumea and Supercell;

Jason Kapalka, cofounder of PopCap Games;

John Romero, cofounder of id Software, Ion Storm, and Gazillion Entertainment;

Ray Muzyka & Greg Zeschuk, cofounders of BioWare;

Raph Koster, cofounder of Metaplace;

Reynir Harðarson, cofounder of CCP Games;

Riccardo Zacconi, cofounder of King; and

Neil Young, cofounder of Ngmoco.

June 2, 2015

An Industry Lifecycle

A new platform on which to play games is invented. It might be a new graphics technology (Vector graphics! Color! 3d! VR!). It might be a technical advancement of a different sort (Modems! Servers! Streaming! D-pads! Small screens! Big screens! Touch screens!). It might just be a new marketing channel (Games in bars! Games at home! Games in restaurants! Games in stadiums!).

A new platform on which to play games is invented. It might be a new graphics technology (Vector graphics! Color! 3d! VR!). It might be a technical advancement of a different sort (Modems! Servers! Streaming! D-pads! Small screens! Big screens! Touch screens!). It might just be a new marketing channel (Games in bars! Games at home! Games in restaurants! Games in stadiums!).

Its distinguishing characteristic is that it is worse at the old sorts of games than the existing platforms, but better at something new.

It’s still cheap to make something for it, usually, and it’s risky. Big companies stay away, or they try porting over something that has worked before. It doesn’t do great because it’s a mismatch for the new capabilities — and restrictions — of the new platform.

Small companies make something that fits the new platform well. Maybe it has the right controls, because the new platform offers something new. Maybe it has the right interface, or the right play session length, because of the new platform demands on the player.

It’s almost inevitably something new in mechanics, with fresh game system design in some fashion. It has to be, you see, to take advantage of what the new platform offers.

Other people quickly start to make more things like that game: they clone it. Quickly, the best executed one of these takes off and founds a genre. It might even be the first one. New inventions are everywhere. Genres are born. People refer to it as a golden age of creativity and innovation in games. Wacky experiments abound that people fondly remember. A whole generation of players grows up thinking this is what games are.

As the platform grows, these early movers can get users very cheaply. The game cost relatively little, and the people with money from the other platforms are fumbling around thinking they know everything.

Because they make lots of money, and they are more worried about little guys than big guys, they start spending more of their cash on production values and on marketing, to freeze out smaller competitors. This manifests as things like buying up ads or users as intentionally high prices that smaller shops cannot afford; pushing higher art costs as they work to extend a technological lead so that smaller groups cannot compete; and buying some smaller guys outright. One of these people eventually makes the game that defines that genre forever. They “win.” And are rewarded with even larger swimming pools of money.

They quickly discover that mechanics innovation doesn’t drive loyalty and is very expensive. Brands and stories, however, are relatively cheap once established, and do drive loyalty. So they divert their spending from innovation towards narrative elements. In particular, they find that characters drive the most, followed by narrative worlds users can imagine themselves in. Soon they discover the idea of the brand extension, where they push these characters into many different (and usually cloned) mechanics and systems in order to extend their reach to new markets.

They also become the new big guys, and quickly succumb to all the same practices that they despised in the previous generation of big guys: exploitative pricing strategies, long crunch hours, aggressive marketing tactics, freezing out competitors using cash, etc. After a while, inertia starts to hold them at the top, simply because they have so much money they can buy their way to staying there. After all, visibility comes with cash, and visibility trumps everything.

Some of the dinosaurs from the older platforms that haven’t run out of money (most did, and died) figure out that the new platform now runs just like the old one, and they join the party.

Pretty soon all the games are heavily narrative brand-building exercises based on the mechanics that were invented in the first few days of the new platform. Genres which cannot sustain the profit margin required to operate the big teams (too small an audience; too expensive to build) are quietly left to die. A whole generation of players grows up thinking that this is what games are.

The two groups of players with radically different pictures of what games are spend a lot of time squabbling on the Internet.

Worn out from working at an increasingly less creative shop, or never having worked at it at all because it seemed like a soulless marketing machine, a group of devs start to develop small things on alternate platforms that the big guys have decided are not worth their time.

One day, one of them hears that a new platform on which to play games has been invented…

April 27, 2015

Did Star Wars Galaxies Fail?

Read the other posts in this series:

Read the other posts in this series:

PvP and temporary enemy flagging

A Jedi Saga

SWG’s Dynamic World

Designing a Living Society, part one

Designing a Living Society, part two

This is the last post on SWG for, well, a while. I am sure there are plenty of other things to say and more questions that could be answered, but… it feels like a natural stopping point. I must say, the response to these essays has astonished me. Here’s hoping you’ll all care as deeply about the next game I make…

Why now?

I’ve gotten a lot of questions as to why I am writing this series of posts about Star Wars Galaxies now. Do I have something to sell?

No, I don’t have anything to sell. This past week was the fifteenth anniversary of that small SWG team first forming in Austin, refugees from Origin. We were a bit over a half dozen. It’s also ten years since the NGE, and in the last few years, we have seen a lot of changes for a lot of parties involved. I was asked some questions by a former player, and for once, it just felt like the time to answer them.

So, was it a failure?

Well yes, of course. And also, no. It depends how you ask the question. There are a lot of assumptions out there about how the game did, particularly in its original form. So, let’s start by tackling some of those:

Galaxies actually had the best one-month conversion of any game at SOE, by a double-digit percentage. More new players decided to stick it out past one month. Given the one-month period, you can’t attribute that just to the Star Wars license. (In addition, the newbie experience was redone many times, including four times just in the first two years; none of these changed the conversion at all).

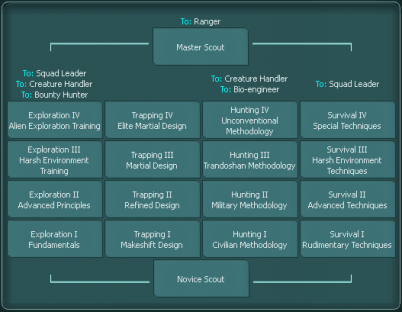

SWG also had the shortest play session lengths of any RPG at SOE (action games, including Planetside, had shorter). This had very much been a design goal: mission terminals, offline crafting and harvesting, etc., were designed to provide exactly this result in order to make MMOs more accessible. Time sinks had historically been a huge barrier to adoption of MMOs by audiences beyond the core. It also had a lot of features designed to attract players beyond the core. These things seem to have worked as intended. These days, people think of SWG as grindy, but it actually had the fastest advancement of any MMO at the time it came out.

However, at the same time, it also had the highest total hours played per week. In other words, it was the least grindy per session, and the most sticky on a week or month basis. Note that lower session lengths naturally equals lower concurrency numbers. But the bottom line is that SWG had the highest percentage of its user base logging in every month out of any SOE game, again by double-digit percentages.

SWG did not sell a million units instantly, and then lose them all, as many claim. It took two years for it to hit a number that big (unlike WoW, which shot up incredibly fast). Early reviews and launch buzz were mixed at best. That said, it was picking up more new users a day than all other SOE games combined, even after the CU. It did have a churn problem, and exit surveys showed all the top answers for why people left were “lack of content.” This was largely attributable to things like the combat balance, the lack of quests, and so on.

WoW didn’t kill SWG. In fact, SWG lost less users to WoW than any other SOE game. (This makes sense — it was the least like WoW, after all). It did lose some of its conversion rate — probably something we can credit to WoW’s buttery smooth experience.

Lastly, SWG was a lot cheaper to make than what was about to be its competition. Like, 1/4 of the budget or less of a WoW.

But…

But…But there are expectations. In SWG’s case, they were damn high. We didn’t do anything to reduce them either.

Some of these expectations in hindsight can be seen as plain erroneous. For example, if you look at the power of licensed IP game genres outside of sports, it’s really not very clear that a license can or will imply a massive increase in game trials or purchases. Certainly the history of Star Wars games doesn’t suggest that just because a game is Star Wars, it will be a hit, or sell disproportionately solely on that basis. (you have to scroll pretty far down on the list of best-selling PC games before you find one that is an intellectual property from outside games).

Licensed IPs also imply revenue splits. This likely made all parties involved have to have a higher bar for success. The game made money; I don’t know whether it made enough.

There is, of course, the fact that the game delivered did not match many players’ expectations of what a Star Wars game is like.

Then there are oddities. For example, EverQuest, our benchmark at the time, didn’t have a vendor system. Players therefore ran second accounts as bots in order to have vendors. This meant that EQ’s sub numbers were pretty inflated. When EQ did add vendors, there was a mass cancellation event that was at first mysterious. I ran surveys on the user base to find out how many accounts a given player typically had, since a credit card database is too noisy (lots of CC numbers per individual) to determine uniques. I did the math, and comparing unique actual people, SWG may well have had about as any players as EQ did!

Really, though, the bulk of the problems over time resulted from Live operations.

The error of good intentions

I think everyone had good intentions towards me in promoting me to Chief Creative Officer. I certainly was into the idea of a big promotion!

I think everyone had good intentions in trying to make the game more Star Warsy for that audience. They wanted to make the game more fun. This includes the Holocron drops, and the NGE, and CU too.

I think everyone had good intentions in adding an auction house, or reducing the group size, or trying to fix the fact that there was an egregious math error in the grouping XP bonus.

I think everyone had good intentions in trying to reduce deployment costs by reusing hardware. Or in choosing to make a more sandbox game rather than a linear adventure experience. Or in reducing development costs using cutting edge procedural techniques that didn’t fit our hardware scope quite well enough. Or in attempting to cater to a broader audience than what MMOs traditionally had.

But many choices had ripple effects far beyond everyone’s good intentions. Really, all of these are decisions that sound good from one angle, but maybe don’t take into account every variable.

My moving off the team resulted in a massive loss of institutional knowledge, and most importantly, left the team without a clear vision of what the game was. You can’t make changes faithful to the experience if you don’t know. This is my fault for failing to convey the vision adequately to everyone; I can only plead enormous scale, and yes, inexperience in working at that scale. I’ve often gotten the critique that I over-collaborate, for example, instead of providing firm direction. That can easily turn into a splintered image of the game. I was also given the normally excellent advice, “Don’t hover over your old team, they need to learn to lead themselves.” Under most circumstances, it’s utterly true. The fact that it wasn’t in this case can be attributed to the fact that I didn’t really train a replacement. It wasn’t until there was more team turnover and the developers were active players of the game who really loved it and therefore understood it, that we saw some things change.

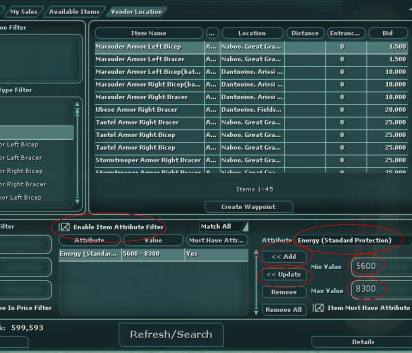

Among the pieces of institutional knowledge lost was how to run the right sorts of metrics queries. Choices like the change to the auction house (which caused one of the single largest single-week drops of subs in SWG’s history) were the result of asking the wrong question: “how many Master Merchants are there?” rather than “how many people run a shop?” There was an almost identical situation with Creature Handlers (how many Masters, versus how many had a pet). Reducing the group size helped combat balance but devastated Entertainers. And so on.

Among the pieces of institutional knowledge lost was how to run the right sorts of metrics queries. Choices like the change to the auction house (which caused one of the single largest single-week drops of subs in SWG’s history) were the result of asking the wrong question: “how many Master Merchants are there?” rather than “how many people run a shop?” There was an almost identical situation with Creature Handlers (how many Masters, versus how many had a pet). Reducing the group size helped combat balance but devastated Entertainers. And so on.

Something like the group XP change was almost certainly an attempt to fix the extreme overpower of players (I mean, sum this to buffs and the rest of the combat problems, and it’s a recipe for running out of content really fast, which was the top reason for exit…). But it went to test, was loudly objected to by players, then was propped live with very little notice, then reverted too late, after it had already caused an uproar. This single event doubled the churn rate of the game, and even after it was all put back, it stayed 50% higher than it had been ever after. In fact, it was worse, in percentage terms, than the NGE was.

CU and other changes each had similar issues. A change would be made on faulty data, would not help matters, and then would trigger more hasty action as people demanded that trend lines be reversed. You can’t fly a plane in the fog with bad instruments. Eventually, the team rediscovered the metrics system, and started to right the course, but it took a while.

In short…

The game wasn’t doing as badly as people seem to think. It didn’t fail in the market. It did just fine, even by the standards pre-WoW. But there were huge expectations that we didn’t push against, it launched with serious problems, and the team wasn’t really equipped to fix them. This resulted in a series of errors that damaged the game’s ongoing viability, which resulted in more hurried changes.

Plenty of the choices made, or the omissions, were my decision; in that sense, SWG didn’t fail. I failed it. Certainly its impacts on me personally were that it drove me to explore both plain old “fun,” something that I felt I had failed at — I got a book out of that; and it drove me to keep looking at ways in which players could own their own spaces, which eventually became Metaplace. Oh, and it made me try to be way more practical, and also made me reluctant to just manage, something which actually hurt Metaplace badly because I spent too much time on raw implementation and getting my hands dirty.

Another But!

And yet here you are, reading about it, fifteen years after we started. Twelve years after we launched it. Ten years since it was “ruined.” Four since it was shuttered. It has clearly had an impact; I get emails about it on a regular basis. Some elements within it have unquestionably helped shape the MMO landscape. Others have perhaps constrained MMOs, as people took away the wrong lessons from why it underperformed.

And in that sense, if it was a failure or a success, it was a glorious, ramshackle, bumbling stumbling mess of one. An improbability from start to finish that never should have worked, but somehow did, and perhaps suffered because that was hard to believe.

Happy anniversary, SOE Austin. I think we actually did make something great. Maybe just not quite great enough? But great nonetheless.

Thanks, everyone, for reading this massive series, and for caring for all these years.

In memoriam: Ben Hanson, Jeff Freeman, John Roy.

April 22, 2015

Designing a Living Society in SWG, part two

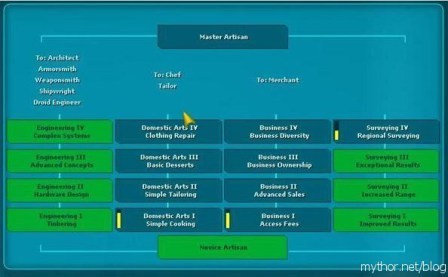

Last time, I talked about the basic skill and economic infrastructure that Star Wars Galaxies provided. Fundamentally, these were about equality. They made the different roles played by players have the same standing in the game. However, it’s still a game, after all — players are going to engage in radically different sorts of activities, probably some will be more fun than others, and nobody is going to just “work a job” for their leisure time.

Last time, I talked about the basic skill and economic infrastructure that Star Wars Galaxies provided. Fundamentally, these were about equality. They made the different roles played by players have the same standing in the game. However, it’s still a game, after all — players are going to engage in radically different sorts of activities, probably some will be more fun than others, and nobody is going to just “work a job” for their leisure time.

There was every expectation that combat was still going to be at the heart of the game. Few social MMOs were out there at the time, though they were achieving impressive numbers. Second Life did not yet exist when we began (they actually came to visit me at the office during the early development of SWG, to talk social design and tech). The skills and actions available were dominated by fighting, and this was by and large what the market expected.

However, we could still try to reinvent what people thought fighting meant. In the classic Diku model that players were used to, you basically had classes that were alternate types of damage-dealers. Some dealt it fast, some slow. Some could take a lot of hits, some only a few. Today we think of these as tanks and nukers. The lone support class was the healer type, who basically replenished the combatants so that they could keep going: basically, an indirect damage-dealer more than someone who actually healed.

Given our emphasis on making a social web, we needed to think in terms of different kinds of support.

A knife in a gunfight

SWG combat was originally modeled after tactical combat using modern weaponry. The proto-SWG that had existed before we rebooted the project (described in “A Jedi Saga”) was an RPG, but with a “cone of fire” style FPS-like system, actually not that different in intent from what came much later in the NGE. At the time, Planetside was in early early development and its combat didn’t even work yet. Doing action-based combat fell out for two major reasons:

SWG combat was originally modeled after tactical combat using modern weaponry. The proto-SWG that had existed before we rebooted the project (described in “A Jedi Saga”) was an RPG, but with a “cone of fire” style FPS-like system, actually not that different in intent from what came much later in the NGE. At the time, Planetside was in early early development and its combat didn’t even work yet. Doing action-based combat fell out for two major reasons:

First, it was unproven. Oh, there was Neocron , eventually in 2002, but it had real issues. The timeline was already insanely risky.

Second, and more important given that we were taking on absurd risks in other areas, was the fact that FPSes had crappy retention.

This may seem insane in these days of massive FPS communities, e-sports, and the like. But games driven by skill, as opposed to RPGs, had always suffered greatly in the online games space. They tended to have a fraction as many users as the RPGs did, because the skill barrier, particularly in player-vs-player games, was very high and newbies were chased away. Stats showed that for the RTS and FPS genres, when online play was offered, only a fraction of users would actually engage in it on a regular basis. Not only was it much more latency-sensitive than an RPG combat system with phase-based combat, but if you had a bad spot, you lost.

So, for the sake of a larger audience, we made the counter-intuitive choice to go with RPG combat rather than action. Bear in mind that during this time period we had quite an active group playing Unreal Tournament in the office after hours, and two team members were veteran FPS people: Nick Newhard, designer from Monolith, and Justin Randall, programmer from Ion Storm. These two guys each reached the number one ranking on different worldwide leaderboards in UT during SWG’s development. We also had a bunch of Wing Commander veterans and we had, as a team, actually recently implemented network-based space combat on Privateer Online.

I spent a few weeks reading up on military tactics for snipers, for assault teams using semi-automatic weapons, and (since pistols were obviously important to the setting, even if somewhat obsolete in modern warfare). Worse than pistols, of course, we had to account for the license’s affection for swordfighting and martial arts, which extended well beyond Jedi and into things like vibroblades and Teras Kasi, a Star Wars martial art.

Based on those materials, I tried to set up as many rock-paper-scissors relationships as I could. Each of these things — melee, pistols, carbines, and rifles — got a different “optimal range” for their combat. Like, rifles were actually pretty useless at carbine range and below. Even pistols were useless when closed at by pistols. The deadliest thing a rifleman could or should expect was a vibroblade between the ribs, as a commando snuck up on him while he was in a sniper’s nest.

Based on those materials, I tried to set up as many rock-paper-scissors relationships as I could. Each of these things — melee, pistols, carbines, and rifles — got a different “optimal range” for their combat. Like, rifles were actually pretty useless at carbine range and below. Even pistols were useless when closed at by pistols. The deadliest thing a rifleman could or should expect was a vibroblade between the ribs, as a commando snuck up on him while he was in a sniper’s nest.

To help this along, there was an inverse relationship between mobility and optimal combat distance. Rifles were great at huge distances, but they were most effective if you couldn’t move. Melee or pistols needed to keep moving, chasing down enemies because their range wasn’t great.

To accomplish this, we added a system of “stances.” These would play into a set of attacks which were based around forcing the opponent into disadvantageous stances. Sniping was best when prone, for example.

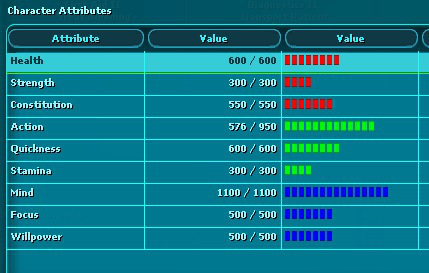

Lastly, given that we had those three sorts of mana/hp, Health, Action, and Mind, I tried to push each of the combat professions towards one of them.

The result should have been not unlike a tactical card game: executing specials targeted at trying to undermine your opponent, pushing into stances, getting skills that allowed you to tumble from prone to standing quickly again, and so on. Riflemen standing well back, sniping carefully into the melee, with stealthed commandos sneaking around back to take them out. As you burned through your bars using your specials you made yourself briefly vulnerable, as your HAM bars bounced back up quickly, so an attacker looked to hit your weak spot right after you did something cool; basically, every attack you could make “lowered your shields.” And as you were hit, you’d gradually run out of ability to use specials, as your HAM bars’ maximum shrank from actual “wounds.” If someone hit zero, they were only temporarily stunned, and others could run in, drag them to safety or stim them back up with some quick field medicine before an opponent rushed in to give a killing blow.

Right about now, to any player of SWG, what I have described in tandem with the “bouncy” nature of HAM as I originally pictured it, is probably sounding completely unfamiliar to them. And that’s because combat in SWG was a disaster.

Right about now, to any player of SWG, what I have described in tandem with the “bouncy” nature of HAM as I originally pictured it, is probably sounding completely unfamiliar to them. And that’s because combat in SWG was a disaster.

With the loss of long-range server updates (the result of a lack of CPU power on the deployment servers), the distinctions between the professions turned to mush. HAM never had any bounce, and timing attack made no sense. You could incapacitate yourself with a special.

We never paper gamed combat. We never prototyped it and built it up from first principles. Like so much in SWG, it was over-designed on paper, because we had to give a 500 page design bible to LucasArts (it was glossy and full color, very pretty). To be honest, I am not sure that any of the people who worked on combat actually liked the system and its ideas. We held testing sessions, and we limited ourselves mostly to seeing if stuff worked at all. Looking back, I feel ashamed and incompetent. The very first item in the vision document was, after all, exciting adventures and thrilling battles.

Third places

Players did find things in that messy muddle that they enjoyed, or that they even thought of as tactical. But it wasn’t long before any hint of combat challenge was destroyed anyway, when buffs got incredibly out of control.

SWG featured several professions that in part provided buffs to players. These were designed as the first stage in a social loop. We had noticed in UO that people reacted very differently to “downtime” aka “time not spent actually doing something” depending on when or where the downtime occurred. Players spoke fondly of the community that formed waiting in line to get your sword repaired at the blacksmith’s, and spoke rather harshly about the “bank scene.” Prep time versus after-action time seemed very different, and chores that made you feel powerful as opposed to chores that were just getting you back to where you were felt very different as well (this link goes to a post from the original SWG forums, explaining our thinking at the time).

World of Warcraft is very explicitly designed to move you forward, not to carry you back to older places. As you advance through a level, the mobs get tougher as you go in, and when you get to the end, the doorway to the next zone is on the other side. In SWG, we were designing in loops instead: sending players out into the wilderness, then bringing them back. We wanted people to bump into each other in “water cooler” areas, and we wanted there to be “third places” in the world, where you voluntarily went for your downtime because you liked to go there.

Because of this, our building list included things like bars, theaters, parks, areas fully intended to one day host player weddings or guild induction ceremonies, and so on. I read books like Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language

Because of this, our building list included things like bars, theaters, parks, areas fully intended to one day host player weddings or guild induction ceremonies, and so on. I read books like Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language (recommended to me by Will Wright) and tried to learn the basics of urban planning and architecture so that we would provide the sorts of facilities and spaces that would encourage players to meet and talk.

(recommended to me by Will Wright) and tried to learn the basics of urban planning and architecture so that we would provide the sorts of facilities and spaces that would encourage players to meet and talk.

Buffers in many cases had roles in these places. So did healers. Wounds, you see, were something that could only be healed in specific places: hospitals, and the camps that rangers could build (I had pictured camps behind the battle lines of major skirmishes, the last place you needed to defend, because with the loss of the camp, you’d lose all support).

More controversially, we modeled PTSD in the game. We used the old WWII name, “battle fatigue” (the WWI name, “shell shock,” didn’t seem to fit). After a while, taking wounds wore you down in a more permanent way, a way that mere medicine packs wouldn’t help. You would need to find an entertainer — a dancer or a musician — to get your mind off of the stresses of battle. And heck, the entertainer would need a venue, and musicians, and a barkeep — read, player vendor in a player-run cantina — with custom food provided by a player chef…

The idea was that battle fatigue would create a natural arc to a combat session. Start out, buff up, and head out, ideally with a ranger, maybe even the equivalent of a USO performer with you. Set up camp as a base of operations. Head out of it and engage in battles that were tactical and strategic, yet still pretty fast paced. Return to camp when hurt, to be fixed up and sent back out. And after a couple of hours of play, break camp, head back to the bar and swap stories while a role-player cracked jokes, sang Star Wars filk songs, and re-enacted scenes from Jabba’s Palace for you. Of course, we were never able to really make this cycle work — we couldn’t tell how long a session was. So battle fatigue didn’t really work out, I think.

The folks at PARC ended up writing a research paper on whether or third places in SWG really worked out. Their conclusion was that no, but that the game as a whole ended up serving that role, in a way. To this day, the fact that there was an entire dancing profession is still one of the things that draws ridicule. But it also draws a lot of affection, too, and dancing is now a staple in MMOs.

Some years later, when I met J. K. Rowling, she asked me whether in a new game, she’d be able to be a fat dancing Wookiee.

The Arts

Dancing wasn’t original to SWG; a “dance emote” had been present in MUDs since near the beginning, and the club scene in Anarchy Online was regarded by many as one of its best features. However, what was new was attempting to actually represent the arts within the game.

Dancing wasn’t the only one. Originally, there were three. For dancing, and player animations in general, particularly facial expressions, I had originally hoped to leverage some more work by my friend Ken Perlin: his work on procedural facial animations and procedural walk cycles. In the days before large-scale IK calculations were plausible in a game, he was doing things like getting across emotional expression via animations that were generated on the fly (these ideas, as well as some of the social architecture work done on There.com by Amy Jo Kim, an old friend from the Ultima Online days, would prove to be profoundly influential anyway, as we’ll see). But it was way too hard to crack the animation problem for that for dances, and way out of scope considering what a small part of the game dancing was supposed to be. So it ended up being loops along with some special moves called flourishes.

Dancing wasn’t the only one. Originally, there were three. For dancing, and player animations in general, particularly facial expressions, I had originally hoped to leverage some more work by my friend Ken Perlin: his work on procedural facial animations and procedural walk cycles. In the days before large-scale IK calculations were plausible in a game, he was doing things like getting across emotional expression via animations that were generated on the fly (these ideas, as well as some of the social architecture work done on There.com by Amy Jo Kim, an old friend from the Ultima Online days, would prove to be profoundly influential anyway, as we’ll see). But it was way too hard to crack the animation problem for that for dances, and way out of scope considering what a small part of the game dancing was supposed to be. So it ended up being loops along with some special moves called flourishes.

Little did we know that when you ask motion capture actors to do a few dances, they would deliver an astonishing and goofy fun set of moves. I’m not kidding when I say that dancing grew in scope in large part because the motion capture came back with so much, well, fun stuff.

Music proved to be a much trickier problem. The spec was actually originally for a skill tree that was broken into performance and composition. Performers could take a score and perform it, on the instruments they had learned. Composers were sort of a crafting skill set: they would unlock keys and scales, and the ability to enter notes in themselves. They could perform these on the fly, or they could boil them down into scores, which could then be sold to performers. And on top of that, the composers would earn performance royalties when people played their music!

This all ran afoul of legal issues. I actually spent time while at a conference in New York City visiting the ASCAP offices trying to figure out how we could be legal about players entering in the music to hit songs and performing them in public places using MIDI notes. Both Sony and Lucasfilm were nervous about copyright issues and performance royalties, and it only got worse when ASCAP raised the possibility that making scores might also imply having to talk to the Harry Fox Agency about virtual sheet music, and that “fixing” the performance as a score might also means compulsory licenses as if we were doing a cover recording (!).

So instead, we went with a system more inspired by loop-based composition as seen in MOD music or loop music studio DAWs like ACID. The system came to life when it was realized that groups needed to coordinate what they were doing. We added in he ability for a concert master, more or less, to direct both dancers and musicians, with a common tempo shared across all the accounts. It took some slightly tricky network programming that has a lot in common with something like NINJAM, but it worked. Eventually, we would see touring bands with cover charges, large sets, dancing troupes, acrobats, light shows and stage shows.

Lord British meets the Golden Brew Players, UO’s theater troupe.

Theater was another profession that I had hoped for early on but went away. Scripts would once again be craftables. Players would follow the stage directions, and of course, we had built actual theater stages into the handcrafted cities in the game. Yes, of course players could (and did) do this all themselves, but again, following the idea that “players do, and respect, what the game rewards” I wanted to provide infrastructure to the sort of things that had been done by hand by groups such as the Golden Brew Players in Ultima Online.

One of the professions I most regretted losing was that of Writer. Quite simply, I wanted to provide in-game feeds for the entire fansite community. I wanted the web fandom inside the game. If you were a prolific blogger writing about the game, it seemed to me that you were a truly material and significant addition to the game community, a massive driver of loyalty, and incredibly important. You should be earning XP for that. You should be earning money for that. Let each writer have a channel on the Galactic HoloNet; let them earn money by either setting a fee to read a piece (like Patreon!) or by letting them ask for a tip via a thumbs-up mechanism when the article was read. Popularity and readers would drive Writer XP.

I thought of this as “Lum the Mad’s profession,” created specifically for Scott Jennings, today a designer on Shroud of the Avatar, and those like him. I pictured the UO book system (a method whereby people could write books and they could get “published” into random books on shelves all over the game) writ large.

It turned out the copyright issues were a contributor to this one going away too. Plus, it was a lot of work that was rather oddball at the time (”can we even hook up an RSS feed into a game server?”). There are no visible writers nor theater troupes in the Star Wars Universe, whereas we definitely see music and dancing. So those stayed, and the others went. We never got to see Writer happen, and to my knowledge it never has been done by a game.

Being you

The intent behind all of these was , of course, to make players provide each other with entertainment, but more critically, to weave them together from disparate groups into an actual community. With the benefits of performance skills tied to locales, you’d have a neighborhood bar. But there were also other little things we did to make players interact on a regular basis.

For example, we allowed players to teach each other things. In fact, earning a certain amount of XP from mentoring another player was actually a required step in Mastery of skills. There had been forms of “learning by watching” in Ultima Online that didn’t pan out and were removed, but this was a more active choice. We even had a whole profession, subject of much derision (”the hairdresser profession”) that was about character customization.

SWG pioneered the use of 3d morph targets for character customization. In UO, we had been one of the first 2d RPGs ever to actually show on your avatar what you really wearing, and in SWG we were determined to do the same. Everquest didn’t do it and indeed, WoW didn’t either. There.com did a little bit, maybe one of the Elder Scrolls games, and I was determined to go way past it.

SWG pioneered the use of 3d morph targets for character customization. In UO, we had been one of the first 2d RPGs ever to actually show on your avatar what you really wearing, and in SWG we were determined to do the same. Everquest didn’t do it and indeed, WoW didn’t either. There.com did a little bit, maybe one of the Elder Scrolls games, and I was determined to go way past it.

We developed a system whereby there were a large group of sliders you could adjust. We let you be fat. We let you be malnourished. After much open discussion with the female playerbase on the forums, we implemented a slider for adjusting breast size, and we ensured that it allowed the full human range of cup sizes. (LucasArts was very nervous about calling it a “breast slider,” so I believe it went in under the name of “torso.”) We created hairstyles and skin tones for every ethnicity, and then we invented ethnicities within the various alien species present in Star Wars. We even got to largely settle the canonical appearance of Bothans, which were famously referenced in Episode IV, but had contradictory visuals in the comics.

We provided clothing from modest to the canonical ludicrous gold bikinis and dancing tights made out of ribbons and hope. We enabled players to make all of this stuff, and sell it and trade it and color it any color they wanted, because above all, we wanted you to find you. (The artists, just as on UO, were really not crazy about letting players do any color combo they chose). And for those times when you decided you weren’t you anymore, you could go to another player, and they could change your character customization permanently. There was even discussion of allowing changes in the avatar’s sex, but in the end I think that didn’t happen, which is a pity.

SWG’s character customization has since been trumped by games like City of Heroes, and the sliders and modifiability that we did are now found in games all over the place. But back then, man, it was magical. You could actually recognize someone’s in-game face.

We also tried to make those faces expressive. Back on LegendMUD, I had developed an elaborate system for chat which allowed players to attach moods to their words. In SWG we pretty much ripped off that system, and extended it to avatar body language. You could set yourself to have a hangdog look in SWG. It would affect how you looked. Your facial expression would change. Taking a cue from roundtable discussions we had had with developers of other virtual worlds of various sorts, I leveraged a small idea from Microsoft’s Comics Chat and turned it into a parser that detected a large array of keywords, punctuation, and other cues and used them to affect your avatar’s body language. Avatars had eye gaze, and we talked about doing what There was doing in terms of automatically positioning chatters into natural circles, with eye contact towards the most recent speaker, but this was a bridge too far.

We even tailored chat logging modes and text output in the game so that you could be an achiever number cruncher and log straight math for combat obsessives, or turn your chat into roleplayer-esque prose, with automatically punctuated speech and “Tom Swifties” throughout.

Roleplayers played this system like a piano.

It tied into the chat bubble system as well. We had noticed that the player behaviors in isometric and 2d overhead MMOs and first-person MMOs was pretty different, and that seeing your avatar or not had a psychological impact on the player. A decent number of potential players also suffered from motion sickness when in first person. We spent a fair amount of time on designing a camera that went seamlessly from first person to chase cam to overhead isometric, so that players could take the camera not only to the kind of camera they preferred, but so that different sorts of social situations could make use of them (for example, we made a point of allowing movement while panning the camera around you, so that screenshots and even player movies could get better visuals).

The chat box was a fairly unimmersive thing, clearly not in the world. It reminded you that you were playing a game. There was something intimate about the over-the-head text in a game like UO, On the other hand, we also knew from MUDs that basically recreating everything from IRC and allowing you to play from the keyboard only as also very powerful. So the chat system did both. I went through comics and websites and built up a reference of the standard chat bubble art techniques that conveyed different emotions, tones, and types of speech. These were also invokable via commands, or through automatic parsing. For a little while, a case was made that we should do our own styles, something that looked more science-fictional or Star Warsy… but in the end, thought balloons and the like carried the day because anyone who has ever read the funny papers knows how to parse them.

Glue

A pic from a Miss Valcyn pageant.

The social dimension of these things is hard to overstate. One example: combine the availability of venues plus tailoring to that scale plus performance skills, and players invented beauty pageants. I remember my shock and delight a year or two later when one of the main organizers of said beauty pageants actually perfectly performed the top-level exotic dance spontaneously on the show floor of E3. That player was now-famous cosplayer Becky Young, also known as Aktrez. (Unfortunately, she was working marketing at Mythic at the time, and her performance therefore took place in the booth for their game. I am not sure that helped her career there).