Raph Koster's Blog, page 2

July 24, 2024

SR Pillars three: the vibe!

The third post in the series on the game pillars for Stars Reach is up. This one is all about the vibe of the world, and the thematic goals for the game… and how those things then reflect into the game mechanics.

Stars Reach is a game about hope and optimism. The real world is grimdark enough. We want to capture that sense of possibility that was present in Golden Age sci-fi, that sensawunda (“sense of wonder”) that it evoked.

That doesn’t mean we have to shy away from serious themes or dark elements in the storylines. We need a world that can encompass many sorts of stories. But it should be presented in an overall spirit of optimism.

The blog post shares a few of the items from our “mood board” — this is a collection of imagery that represents some of the feelings and aesthetics that we were aiming at. In the blog post, I spend a lot of time talking about the optimism of old Golden Age science fiction, but that’s not the only source of the aesthetic we are aiming for.

The mood board also has in it stuff like screenshots from old arcade games, because they offer that sense of instant comprehensible fun that we are after — and because space spiders sound like something fun to encounter boiling out of an asteroid. We pull inspiration from the sheer wacky inventiveness of some of these older games, and translating a few of their mechanics into modern 3d has felt like a fun design challenge that ends up feeling fresh.

It’s also got plenty of Ghibli background art in it. It’s almost a cliche these days, I suppose, given how pervasive the influence has become. But we do really want to capture not just the pastoralism but also some of the weird. We look to some of the backgrounds from Bakshi’s animated films as well.

But overall, one of the bigger influences for me on this game is actually the original Valérian et Laureline comic albums, which first started getting published in 1967. This comic has had a big influence on media SF depictions of technology and the alien. There’s a strong claim for it having influenced a very large amount of the look of Star Wars, and of course, the artist, Jean-Claude Mézières, also worked directly on The Fifth Element.

I grew up reading these in the early 80’s, while living overseas. And, for that matter, watching early work by Miyazaki, such as his work on World Masterpiece Theater.

Sometimes creativity is just about recapturing the sense of wonder we had when we were ten years old.

Someday, we’ll do a blog post that is a much deeper dive on the mood board, influences, and so on. In the meantime, you can read this post, argue about it on Discord, and maybe if you want, sign up for testing or wishlist the game on Steam!

July 18, 2024

SR Pillars Part 2: Easy Surface, Much Depth

Yup, another week so I wrote another long post about the design pillars we are using for designing Stars Reach. (If you missed last week’s, it’s here, and I expanded on it on the blog here.)

This week, it’s all about the second set:

The Ease of Nintendo Meets the Depth of the Sandbox MMO

The game will be deep: a set of proven game mechanics brought together in one universe.Controls and interfaces will be intuitive and simple and familiar.We will support varied clients so that players can play on whatever device they choose.

I go into details on each of those over in the article on the Stars Reach website.

Something that I meant to dig into in that article, but totally forgot to, is that all this talk of forms of accessibility really needs to include a factor that has hugely affected the development of MMOs over the years: the time commitment.

MMOs are infamously time consuming. Twenty or so hours a week — who has that kind of time, in today’s interruptible, constantly busy world? Especially if you’re older now, as so many MMO fans are these days? Kids, jobs, other hobbies… Participating in an MMO really ought to be something available to everyone.

Because of this, one of the implications of these pillars is our attempt to make an MMO that you can play in sessions as short as five minutes. One where there are a lot of asynchronous ways to play and feel like you matter to the community, even if you can’t devote the continuous hours to it.

Sessions were shorter! People could squeeze in play sessions in smaller open blocks of time. This helps make the game more accessible to people with demands on their time.The peak concurrency actually fell some as a result.This can seem bad, because a lot of people like to measure a game’s popularity based on peak concurrency. But if you walk through the thought experiment, it’s easy to see that session length drives peak concurrency. (If you have 100 people play a five minute game in a day, you will probably have a peak concurrency of 1. If you the play session lasts 24 hours, you will have a peak concurrency of 100).Lower concurrency might seem worrisome for social reasons too… but a lot depends on whether players are participating in the game even while logged off. Which in a game with a robust player economy, offline crafting, and so on, they can be. (I talked about this somewhere in the middle of the talk on Small Worlds, long ago).The aggregated amount of time played over long time periods actually added up to more time than the games with longer sessions. Taking advantage of smaller blocks of time lets more blocks pile up.Even the research we did on the Trust Spectrum showed that players tended to prefer session lengths in the ten to thirty minute range, though longer sessions were considered to be fine.

A huge part of the explosion of mobile and casual gaming has just been that you can play the games in small snatches of time. If sandboxy play, as mentioned in the article, actually is something of broader appeal than people think, then that also suggests we should enable short sessions.

None of this says that the game can’t be deep at the same time. We’ve tried to build in a lot of things to make it easy to have a fun session in a short amount of time, but they all still tie into the deep systems we want from a game that can hold us for years. Stuff like being able to teleport to your friends for a session, but not being able to transport goods with you (so we don’t break the local economies). The way our combat works, or the way our crafting works, also play into this. And so on.

Really should have talked about this more in the article. Oh well!

July 10, 2024

Stars Reach Pillars

I have written a blog post about the core pillars of Stars Reach over on the SR website.

We have three big pillars, each of which decomposes down into a series of goals — three each — and then those provide a host of more specific design rules or guidelines that the game has to follow. It’s core to how we manage a large complex project like this, trying to keep everyone aligned towards the same goals.

It still isn’t always successful. It’s super easy to forget to refer back to them. For a while, we even had the requirement that if you were working on a design document, you had to look up the various design vision statements and paste them in at the top of the doc, in order to force you to have them top of mind.

If we were still in an office, I’d have them plastered on the walls. But it’s one of the tradeoffs from doing remote work, I suppose. Not the same thing at all to just have a pinned post in Slack.

These aren’t the only sorts of thing we have tried, or that game teams have tried, in order to unify vision. Lots of games think in terms of “an X.” Others have “USPs” or “unique selling points.” Plenty use the hoary old Hollywood method of “A meets B.”

In our case, we have used almost all of these. We certainly speak of the living world as a core USP for Stars Reach. I am also fond of “what the game is, and what it is not,” or “Yeses and No’s” tables, where you just list off things that the game must meet, and things that it must avoid.

But I still tend to start out with pillars, personally. Usually these are the third thing I write in a design one-sheet or proposal, right after a brief paragraph describing the game experience, and a brief bullet list of features.

The ones that I wrote about today are all centered around the living world:

The most alive online world ever created.

The game will run off simulation, rather than being built of handcrafted static set pieces.The game will be a true persistent state world so players can affect things for real.The game will be driven by player community and interdependence, including the economy.

Plenty more detail over at the SR website, and of course, you can sign up there to get in line for testing, which is coming up soon, or join the Discord or wishlist on Steam!

July 3, 2024

Wishlist STARS REACH and its living world

Over the years, I’ve tried many ways of making living worlds. This video here explains how we are doing it on Stars Reach. Which you can now wishlist on Steam.

The Living World of Stars ReachAs you can see if you watch the video, we’re already pulling off something a bit unusual: modelling a world at MMO scale using cellular automata. What that means: we know the humidity, the temperature, the material, the viscosity, the adhesion, for every cubic meter of the world.

In gameplay terms, it means that you can dig a pond, fill it with water, watch the plants around it green up, watch the dirt in the pond turn to mud, get slowed down by the mud when you trod through it, watch the pond freeze over in the winter and slip and slide when you walk on it.

It means you can drown a monster who breaks through the ice. You can heat up the pond and watch it turn to steam, and float away. That’s OK — it’ll precipitate somewhere else.

Everything does what you expect it to do. Which sounds sort of ordinary, until you realize it’s also kind of magical.

Cardboard and stage setsOn LegendMUD, I would carefully handcode NPCs in ways that made them more interactive than just fodder for slayage. You could play blackjack against one in Victorian London. I made an Indiana Jones bot that roamed the whole MUD and could speak about a ton of trivia details garnered from the Young Indiana Jones Chronicles TV series. But it was super apparent this was a ton of work, and players just consumed the content.

Think about that word. Consumed. They ate it, chewed it to bits, spat out the bones. There was no way to keep pace.

On Ultima Online, we swung for the fences with a creature ecology based on abstract properties. It still serves as the basis for the crafting system and more, but we never managed to get it performant enough to be worthwhile, and it wasn’t directly visible enough to players. But even though you could take an axe to the trees, they never fell.

On Star Wars Galaxies, we had shifting resource maps, and the ability for players to even found cities that existed on the map. But when when you dug up special ore, you never made a hole in the ground.

The fact is that one long-term legacy of themeparks and earlier online worlds is that they are really built more like stage sets, than as inhabitable places. They look good from a distance, but they are really not designed to be lived in.

To go beyond that, you have to simulate.

Meteors falling from the sky and leaving craters

The approach in Stars Reach

Meteors falling from the sky and leaving craters

The approach in Stars ReachAs the video describes, we are doing a cellular automata approach. And from the video you might think that only applies to the terrain. But what is really going on is that we are pulling the evolved version of how the simulation worked in UO and SWG into 3d space.

Like UO, every “tile” knows what materials it is. Unlike UO, they can change. (On UO, we could only change the totals every 64 tiles, and we couldn’t reflect it visually at all, because the map was baked down and static).

Like SWG, we have the notion of these materials actually having varying statistics. But now, instead of these only being used for crafting, they can affect the physics of the world.

Like UO, creature AI is driven by looking for these underlying qualities — not by referencing specific object types. And like both games, crafting also uses these resource types and statistics.

There are new tricks, like states of matter, having everything affect locomotion, having chemical reactions between things, and so on. All in all, it should let us do much richer gameplay on many fronts. Even something mundane like farming can now draw from a host of variables that normally aren’t available to the game system.

Static on top of dynamicOne concern people always have is that this can mean that you have a soup of procedurally generated stuff that doesn’t cohere or cannot accommodate narrative. But the beauty of simulation, as opposed to just procedural generation of static content, is that you can always stack static content on top of it and it will fit in pretty well, because it also obeys the rules of the sim.

The real win, though, is always player empowerment. And that’s really what we are aiming for here: worlds that react to what you do as you play, in plausible and fun ways.

Again, you can wishlist the game here.

June 28, 2024

Announcing Stars Reach

It’s been years of work, and we are far from done, but I am super happy to finally reveal what I have been working on at Playable Worlds: Stars Reach.

This is the game I have wanted to make for nearly thirty years. It is the spiritual sequel to Ultima Online and to Star Wars Galaxies. It has in it all the lessons of all these decades of online game development — and it looks forward, not back, to reinvent what an online world can be. I believe it does things that other games just can’t do.

The most alive game world ever madeStars Reach uses simulation to a degree never seen in an MMO before. We know the temperature, the humidity, the materials, for every cubic meter of every planet. Our water actually flows downhill and puddles. It freezes overnight or during the winter. It evaporates and turns to steam when heated up. And not just our water — everything does this. Catch a tree on fire with a stray blaster bolt. Melt your way through a glacier to find a hidden alien laboratory embedded in the ice. Stomp too hard on a rock bridge, and watch out, it might collapse under your feet. Dam up a river to irrigate your farm. Or float in space above an asteroid, and mine crystals from its depths.

The whole game environment is modelled this way. It gives us not just those examples of gameplay, but many more. And it makes the whole experience that much more immersive, because everything acts like you expect. Melt the sand on the beach, and it becomes glass.

A video on the vision for the game Humanity’s second chanceLong ago, an incredibly powerful alien civilization we know only as The Old Ones terraformed arms of our galaxy to make their Garden, a place where they could play with their superscience powers and their genetically engineered creations — such as us humans. They’re long gone now — and we should probably be pretty terrified of whatever chased ’em off.

But they left behind robot Servitors who roam the spaceways tending the planets and their various lifeforms. The Servitors fight off the tentacled spores of the hivemind Cornucopia that infects worlds. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of worlds, each with their own unique gravity, minerals, creatures, landscapes, seasons, and even lengths of day.

Unfortunately, we humans have ruined our homeworlds. Nuclear winter. Peak oil. Climate change. Even global pandemics, if you can believe that one. And so it is that the Servitors have felt obliged to let us out of our cozy planets and into the wider Garden.

It’s our chance to do better this time.

STARS REACH announcement trailer A classic sandbox worldThis is a sandbox online world featuring all the things that players of those games love.

A classless skill tree advancement system, where peaceful play matters just as much as combatAn intricate player-driven economy where players can craft their way to fame and fortuneAn accessible yet deep combat system, where you can choose whether to play using action aiming or more forgiving homing shots or lock-on targetingIn-world player housing that lets you build and customize your home and form towns… and enough room for everyone to have a houseA single shardless galaxy, with both space and ground gameplay… in fact, you can build that house on an asteroid, if you wantThe ability for a group to govern a planet, and define its laws, whether you want a peaceful home or a PvP free for allBut we’re also doing a lot of new stuff. Like, we are aiming for sessions as short as five minutes. A fresh take on horizontal progression. Making an MMO with hardly any HUD!

We’re not done yetWe’re announcing today, but that’s because we are finally ready to decloak. It’s time to move from stealth to bringing the community along on the journey. We have a lot left to build, but we want to do it in public, with the help of the players that this game is for.

The graphics need a lot of work. Combat isn’t balanced. We haven’t fleshed out all the skill trees. But we’re going to start testing with players this summer. Because this game is for you, and you should be involved in the choices we make.

The stars are yoursYou’re being given a galaxy. The question is, what will you make of it?

Follow along with the project at any of the links on this linktree: https://linktr.ee/starsreach — and I hope to see you in the Discord or on Reddit, or just in the comments here! I’ll be doing an AMA at 10am Pacific today in r/MMORPG and answering questions, too.

March 28, 2024

GDC talk: Revisiting Fun

My GDC 2024 talk Revisiting Fun: 20 Years of a Theory of Fun is now posted here.

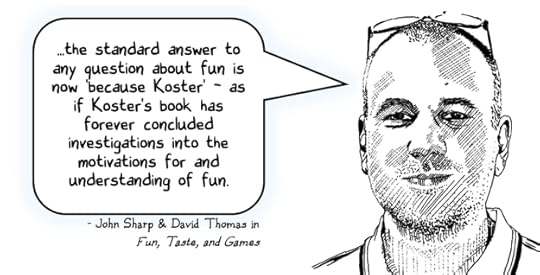

Once again, I had a lot of fun drawing cartoon heads of lots of people who feature in the talk.

The talk really is a direct sequel to the one from a decade ago, Ten Years Later. Unlike last time, there is no updated edition just yet, though I was asked by lots of people if there was!

Since the original book came out, it has gone from being controversial, to being dogma to rebel against, to being “obvious” according to many. It’s available in nine languages, and continues to sell just about as well as it did when it first came out.

The talk mostly covers objections and concerns people have had with the original book, a discussion of some of the newer science and ways in which is updates or makes obsolete parts of the original, and a hefty section on how to apply the principles in the book in a practical way. This latter one draws heavily on the recent article on the NYT game Connections, but also on several other talks I have given in the last decade or so.

Someday, I’ll get around to the three sequels I have planned out in my head!

September 2, 2023

Why NYT’s Connections makes you feel bad

Connections

ConnectionsThe new daily game at the New York Times is called Connections, and I’ve seen a few people comment that they just don’t like it as much as Wordle or Spelling Bee. That the difficulty is inconsistent and it often makes you just feel stupid.

I thought it would be interesting to contrast this to Word Dad, a puzzle game made by my friend, master game designer John Cutter.

A brief aside on puzzlesAll three of these are more correctly called puzzles, of course. The main difference between a game and a puzzle is that a puzzle has one real solution, an optimal way through the challenge. In a game, finding an optimal way through the challenge is known as a degenerate strategy or even “solving the game” if you’re a mathematician. This means that really, puzzles and games are terms that are matters of degree, not kind.

In A Theory of Fun I term games “a series of puzzles,” partly because a game is presenting you with lots of decisions, each of which has a theoretical optimum choice. In practices, most good puzzles also have many decisions, because you tend to play the same ruleset repeatedly, but with different statistical variations in the content. In that sense, like a game atom, puzzle are usually one logical ruleset, and have just one way in which the puzzle operates, which is a systemic machine that can take data variations. Sudoku is a machine; a given Sudoku layout is an individual puzzle. A Rubik’s Cube always has the same verbs and the same logic, but it has a ton of possible starting states. Not that different from fighting one monster versus another using the same combat system in an RPG! You get the same verbs, the same affordances.

But a puzzle’s output is usually pretty binary. You either got the answer or you didn’t. A game will give you finer-grained feedback, you can do better or worse at it. Many puzzle games try to offer an efficiency metric to give you a gauge instead. This is going to be important for our design comparison.

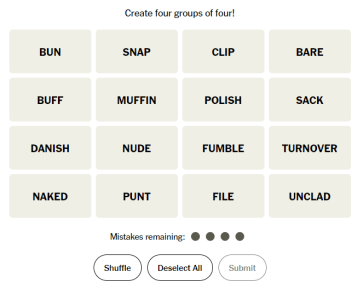

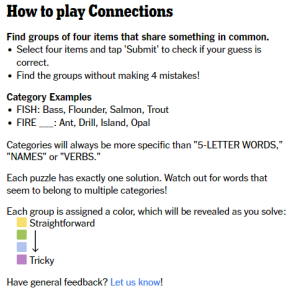

Connections The rules of Connections

The rules of ConnectionsConnections is a game with a grid of 16 words. They’re jumbled around, but they are actually four sets of four. The trick is, you don’t know what the grouping terms are. The rules somewhat misleadingly give examples that are essentially noun-based: group all fish together, group all compound words starting with “fire” together. But then it says “categories will always be more specific than ‘five letter words,’ ‘names,’ or ‘verbs.'”

The trick of course is that words might well belong to many categories at once.

If that were all, the game would be much like Set, a game of set-building by examining the “stats” on the individual items and grouping them. Set, however, uses essentially numbers as its stats. A fixed list of colors, a fixed list of shapes. The permutation space is sizable but still small: there are only 81 distinct cards in Set. This is larger than a standard deck of cards, but also smaller in some key ways. (Doing the exercise of tallying up the number of “fields” and how large the “scale” is on each in a standard deck versus a Set deck is a worthy system design exercise I leave to the reader).

Word games have really really large, unbounded scales and fields. As the game rules mentioned, number of letters in the word is one such field. Meanings is another. Spellings is another. Heck, Connections could make a set of four words out of whether or not they use the dʒ, tʃ, or ŋ phonemes.

The learning loopIf we go back to Theory of Fun again, the core premise of the theory is that iteratively tackling a problem helps you come to understand the systemic machine in an intuitive way, and fun is the reward for that. All those varying Sudoku puzzles are there so you learn the generic methods of solving all Sudoku puzzles. The variations are like touching more parts of the elephant with your eyes closed. The more parts you touch, the closer you get to understanding the shape underneath.

So you loop over the game, and do it again with a slightly different problem set, and you keep doing it until you master the underlying logic. After that, you may only enjoy the game as a way to practice, or to mindlessly meditate. A larger game might scaffold you to more sophisticated problems by making this mastered element be simply one brick in a larger edifice of understanding. (Dan Cook has a great article walking through structures like this).

Ah, but what happens when a puzzle depends on your knowing facts, as opposed to methods?

Trivia games have this problem, so do spelling games, and games like Scrabble. They call for a large quantity of crystallized intelligence — large vocabularies, historical minutiae, memorized stuff. Games can help you learn memorized stuff, for sure! Anyone who has kids who learned the name and statistics of every Pokemon knows how that goes! But we learn those things in the service of mastering the loop.

Different people come to a game not only with different amounts of experience in systemic rulesets — which is why they bounce off of some genres — but also with differing amounts of crystallized knowledge. A core issue with trivia games, though, is that the statistical space of a trivia game is so large that playing more trivia games doesn’t particularly help you get better at trivia. This is why so many trivia games (such as Jackpot Trivia, the one I worked on with NTN Buzztime) have other mechanics alongside, in order to help people who may not bring a huge memorization library to the table when they play. In Trivial Pursuit you have a degree of control over the category, and you have control over which direction to travel. These effectively add more variables in the game so that a player with less trivia knowledge can outplay a player with more, through smart movement and concentrating questions on their strengths.

Can you learn to get better?If Connections only relied on crystallized knowledge for the words, that would be one thing. But in practice, the set-building criteria themselves are often dependent on crystallized knowledge. Let’s look at yesterday’s puzzle. The words are:

ConnectionsFluteCoffeePoundOboeSteinFricasseeBishopTumblerBassoonFrostGobletClarinetOldsSnifterSaxophoneBalloon

ConnectionsFluteCoffeePoundOboeSteinFricasseeBishopTumblerBassoonFrostGobletClarinetOldsSnifterSaxophoneBalloon

The trick, of course, is that many of the words clump very easily into groups, and can belong to many groups. There are five wind instruments: flute, oboe, bassoon, clarinet, saxophone. Ah, but four of those five are reed instruments — which is trivia knowledge, relatively esoteric to anyone not a musician with a particular sort of training. And all five are woodwinds even though saxes are made of brass! All of those are things you blow on or into, but so are coffee and balloons! There are four drinking vessels for alcohol: stein, snifter, goblet, and tumbler. Ah, but Gertrude Stein, Robert Frost, and Ezra Pound all jump out as famous poets. Those last names are like a card in a deck being both an ace — all poets — while all being of different suits, where the suits are other categories they could belong to.

You get the idea — the more you know, the more categories you see. The puzzle is trying to teach a form of orthogonal thinking, to push players to find unusual ways to group things. But it’s fundamentally elitist — it basically requires you to have a broad education to find the categories in the first place.

The success/failure metricIf you had unlimited tries, this wouldn’t matter. You could essentially brute force the puzzle. Create a set of four. See if you can find a set in the remaining. Repeat. Any time you cannot, back out a level, undo the set you already tried. Over time, this algorithm will in fact give you the result, probably along with a lot of Googling.

The fact that the puzzle is susceptible to a brute force search isn’t a problem — so is Sudoku! Lots of games are like that, actually. Crosswords are! In fact, A Theory of Fun would argue that learning how to do that is in fact the lesson the game teaches, since it can’t teach you modernist poets or the difference between classical wind instruments itself. No, what it can teach you is how to be methodical, and the value of research.

But in order to add a sense of challenge, the designers of this puzzle decided to not let you use that algorithm. If you make an incorrect set more than four times, you lose. Now the game is handicapped in teaching you its intrinsic lessons! (You can still do it, but the puzzle affordances push you not to. You could make index cards with the words, sit with Google, try to solve it offline, then once you do, input your solution. But this is a pain in the ass).

Fundamentally, the game invites you to make guesses, but punishes you for them — and a missed guess doesn’t help you prune the logic space, only the trivia space.

As a result, it is entirely possible to build a solve that is all wrong, based entirely on valid category groupings that aren’t the ones that the puzzle designer intended.

Inconsistent difficultyBut building a good puzzle of this sort is very very hard. Do you feel clever when you notice that fricassee, balloon, coffee, and bassoon all use doubled vowels? Probably — the thrill of seeing a pattern you knew must exist. But did the designer mean to also have four words with two O’s in them? Balloon, bassoon, oboe, and saxophone do. It’s a valid pattern that is a red herring. A well-designed puzzle of this sort should have fewer red herrings than the number of mistakes it allows. But no puzzle maker will be able to anticipate all the valid groupings a knowledgeable and clever person will be able to find.

Out of those five wind instruments, by the way, the right answer was flute, clarinet, oboe, and saxophone. To the player, this can’t help but feel arbitrary — the only reason bassoon isn’t valid is because of the constraints of a different set.

When I said this was an elitist’s puzzle, I meant it. It demands a lot of knowledge, or a lot of time, it basically makes you “do the crossword in pen,” and it’s basically not something you can ever expect to have a good learning loop. It will always feel like it is inconsistent in difficulty, and that’s why we are seeing the reception we are.

I am not sure you can fix the basic premise here, to solve these issues. You’d need to have a fixed list of category types, and that would render the problem space trivial rather quickly over time. One approach might be to gather data on the the wrong solves players assemble, so that over time you can get a sense of which set types are harder than others. But it’d be a lot of manual labor, probably. Maybe ChatGPT could deduce what a submission was meant to group as… Maybe.

Over time, I expect that players will start to deduce the rules the NYT authors themselves use for authoring… what they consider to be an easy versus hard category. They have such a rubric — supposedly the four sets are each of a different difficulty level. But… the easy one this time was supposed to be the woodwinds. So… I suspect there’s a lot to learn about what actually makes for hard versus easy categories. Big Data may be the only way to actually arrive at a valid answer in order to smooth out the play experience.

As an aside, the advanced style of NYT crossword has many similar elements to this. But there are several things that help: difficulty ratings on the puzzles, learning puzzle authors’ styles, and the wide availability of easier crosswords out there, which help you learn the underlying logic (which at the advanced level, includes truly esoteric trivia, often multilingualism, advanced degrees, and a keen sensitivity for wordplay). If the only crossword puzzles in the world were like advanced NYT ones, few people would do crosswords.

Word DadWhere a puzzle becomes a game

Word DadWhere a puzzle becomes a gameWord Dad has a very different approach. Unlike Connections, it does not have a singular answer to the puzzle. You see spaces for three words of varying length. You have a set of letters, exactly enough to fill all the spaces. You just need to make three words.

Once again, this is open-ended set building, and rewards crystallized knowledge in the sense of a wide vocabulary. The contrast to a typical puzzle is that the game accepts any valid solution that makes three words! Now, instead of the puzzle designer being in charge of the “category” axis, you are. This makes the words into verbs rather than content, which is the same move that is pulled by Scrabble and Boggle and countless other classics.

You have a success metric, too. All valid words, you see, fall into one of three levels: common, uncommon, and rare. This gives an implicit “score” you can get. If we assign 1 point for common, 2 for uncommon, and 3 for rare, you can solve the puzzle with any score from 3 though 9. (The game doesn’t actually show you a numerical score this way, but players have gravitated quickly towards aiming for scores of 9 — i.e. three rare words). Rare words, by the way, are not all that rare! You will almost never need to reach for a dictionary.

A mediocre but valid solve for this puzzle

A mediocre but valid solve for this puzzleYou also get only one submission — so you can experiment all you like, iteratively finding an optimal solution — and even better, there are frequently several solves worth 9 points! Invalid words are quietly rejected with no penalty.

Word Dad rewards you with a groaner dad joke or pun when you solve the puzzle, which is a nice bit of feedback that strongly themes the game. But the underlying problem space is already pleasing. You feel in control, you can iteratively learn the patterns to to go for. In this case, the logic rulesets you are deducing are “which words tend to be common and rare in a corpus?”, “what is the letter frequency of words in English” which is a nicely bounded statistical space to master, and a fun resource allocation problem across that landscape with vowels. You quickly learn tactics that turn STUB (uncommon) into BUST (still uncommon) into BUTS (rare!).

A fun wrinkle: given a dictionary of valid words, you can procedurally generate Word Dad puzzles, and guarantee 9 point solves. You just pick three rare words and scramble them! So it’s easy to make more content for, rather than hard. This is a virtue.

Making it even betterWord Dad uses word length as its difficulty metric. Over the course of the week, the words get longer. But I don’t think this is actually the right metric at all.

In practice, the thing that most affects difficulty is “how many valid solves there are.” The more there are, the more opportunities for players to deploy their vocabulary verbs, the more chances to feel smart by finding more solutions. If a given layout only had one solution, given that the words are generated by starting with three rares, the puzzle would be extremely hard, and back to binary: either you score 9 or you lose.

You could address this by adding a solver to your generation routine: have an unscrambler check the layout, and see how many valid solves it can find. Reject puzzles with less than a certain threshold. Ideally, reject them unless they permit the full range of scores from 3 to 9. Personally, I would also reject puzzles that only have one 9-point solve.

You could also make your generator better. The main thing that constrains the possible solutions landscape is the number of vowels. One of the things that currently messes up the difficulty ramp from the early week easy puzzle to the hard end of week puzzle is that you might get an “easy” puzzle with very few vowels. This cuts the possible solutions down dramatically, and starts favoring “trivia” knowledge like “Scrabble words with no vowels” and the like.

Lastly, there would be a big win in expanding the scoring scale. A decent player can start scoring 9 every single day without too much effort. In that sense, the game is too easy. This is no major sin: There is lots of room in the world for an easy daily diversion, but designers have to eat, so improving the game’s retention is still a worthy goal. Easy ways to add “skill ceiling” would include

Including time as a score component: a higher score goes to a 9 point solve in a shorter time — this rewards one sort of playerHaving rarity within solutions: there are often several 9 point solves. Grant more score for esoteric, unusual solutions compared to the commonest solution the playerbase arrived at. This would reward a creative impulse and add a whole new logic puzzle to solve (“how do other players of this game tend to think?”)Bonuses for unusual words: a solve that included a word no one else used could provide a different sort of thrill to a player, and provide an orthogonal goal to pursue.None of these need conflict with one another, and they’d all add to the game’s depth and replayability. It’s probably not hard to come up with more.

Game grammarAnyway… I didn’t really mean to spend my Saturday afternoon doing a close systems analysis, but it’s been a while since I did anything of the sort. Or posted on the blog at all!

If you are a game systems designer, these are ways of thinking you should learn. Learn to see how games — even word games — are built out of common elements like set formation, tokens as verbs, statistical distributions, learning loops, and all the other concepts I’ve mentioned here. This is what I call game grammar: the underlying rules all games share. This same analysis can be done on a platformer or an RPG, a tabletop game or a sport. They’re all games in the end.

September 24, 2022

Ultima Online’s 25th anniversary

Well, twenty-five years is a long time. Half a life, in fact!

Given that I actually started work on UO on September 1st 1995, it’s actually more than half. The fact that the game is still running is a testament to the devoted community and the ongoing maintenance over the years from countless people.

I note a lack of thinkpieces and articles, this time around. The fact of the matter is that the most frequently targeted gamer audience wasn’t born when UO came out. A lot of the folks streaming about games weren’t born yet either.

I saw a post on Reddit yesterday that asked “how come no other MMOs have done open world housing, besides ArcheAge?” Ah well….

In many ways the influence of UO is so pervasive that it isn’t visible. Whether it’s Runescape, Minecraft, Eve, DayZ or Neopets, those younger folks probably played something that was inspired by UO in some fashion, and don’t realize how big a shift from prior games it represented. These days, when people say they are sick of crafting being in everything — it makes me want to apologize a little bit. Won’t apologize for games that let you sit, decorate a house, or go fishing, though.

I’m running low on specific stories about UO and its development, so instead, I’ll just point back at older ones:

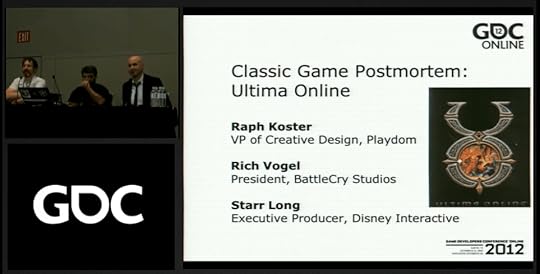

First of course, has to be the postmortem we did at GDC for the 20th anniversary:

This postmortem drew pretty heavily on the article “Ultima Online’s Influence,” published on this blog five years ago at the 20th anniversary. If you’re one of those people too young to know why UO mattered, this article is probably the place to start.

That video wasn’t the only time we did a GDC postmortem though! There was another one back at the 15th anniversary in 2012 as well, which is available on the GDCVault. The session was very informal — don’t expect a lot of actually useful development takeaways, five things that went well and five poorly in Gamasutra-approved format, any of that. Instead, it’s mostly war stories and anecdotes.

Click to go to the GDCVault… they don’t let you embed these, it looks like.

Click to go to the GDCVault… they don’t let you embed these, it looks like.A thing you cannot see in the vid — when at the very start Starr asks how many people in the room worked on UO, a lot of people in the room stood up. And when asked who played — it was almost everyone. A nice moment.

At the twentieth anniversary, I recommended these articles in a blog post, and I think they’re still the place to go if you want to read more on this site about the game’s development, philosophy, and challenges.

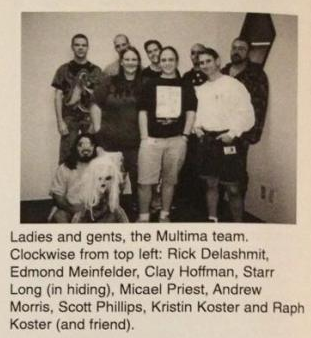

UO’s resource system parts one, two and three. These describe how the underlying world of UO works — from the “infamous dragon example” that never came to fruition, to how it still underpins crafting and AI.A UO postmortem of sorts, which is a written one I did and not the same as either of the above videosThe evolution of UO’s economy. Every time I turn around on social media, I see another Web3 enthusiast saying that they are drawing all their inspiration for digital economies from their childhood playing Ultima Online. Really not sure that’s the right takeaway… Database ‘sharding’ came from UO?How UO rares were bornRandom UO anecdote #2, which periodically goes viral on TwitterRandom UO anecdote #1Ultima Online is fifteen, which has a host of stories about the game development.The end of the world covers several games, but includes the story of the end of beta. Our original tiny team. The friend is a hobbyhorse that was around for some reason. I don’t remember why I took it to the shoot.

Our original tiny team. The friend is a hobbyhorse that was around for some reason. I don’t remember why I took it to the shoot.Since that list was put together, I’d also add “A Brief History of Murder,” which is over at Game Developer. It’s an excerpt from Postmortems, my book that has a bunch more material on the history of UO.

UO when it first came out got a pretty mixed reception. Including picking up the “Coaster of the Year” award (which made more sense when games came on CDs). But it did pick up plenty of awards at the time.

But since then its legacy has gone on to be cemented by being named one of the 100 most important games in history several times over, by both gamer sites like PC Gamer and Polygon, and by big mainstream press like TIME Magazine.

The alpha logo

The alpha logoNot too bad, even if all the younger folk aren’t quite sure what it is.

That’s OK. Frankly, my sense is that in many ways, now is actually UO’s time, in that the ideas it represented (and still represents!) are actually everywhere in games. It just took a while for everyone else to catch up.

If you’re one of the oldbies yourself, try reviving your account over at Broadsword Games: they’re giving away a veteran reward for people who have quarter-century-old accounts.

Ultima Online is giving a special shield to players who have played the game FOR 25 YEARS pic.twitter.com/O4KOoNFd7e

— @mikko (@mikko) September 23, 2022

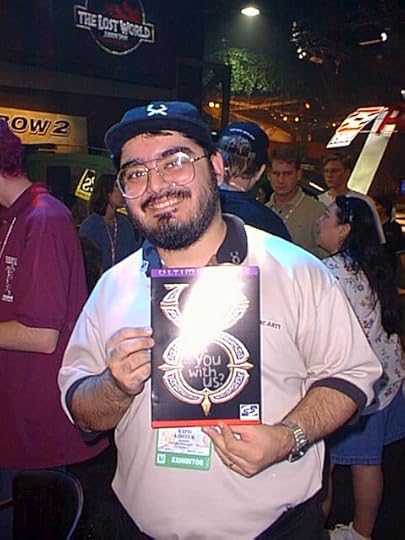

I have some photos that various folks have sent me over the years from the early days. So here’s a few:

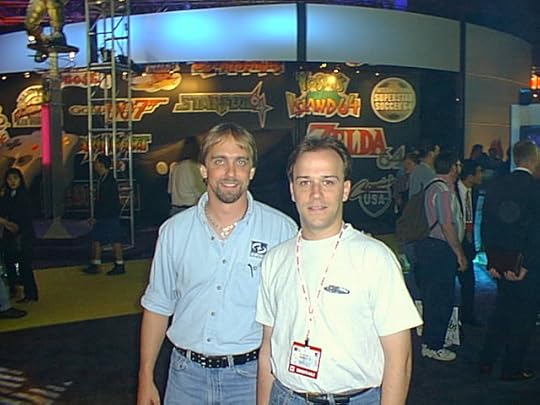

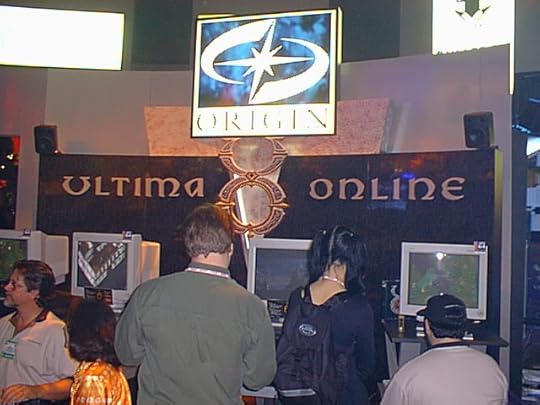

These first ones are all from E3 in 1997.

Me with the brochure

Me with the brochure Richard Garriott on the left

Richard Garriott on the left Starr Long on the right

Starr Long on the right

Scott Phillips demoing, Starr behind him

Scott Phillips demoing, Starr behind him Rick Delashmit, myself, and Todd McKimmey taking a break from UO development to try out that newfangled Playstation

Rick Delashmit, myself, and Todd McKimmey taking a break from UO development to try out that newfangled Playstation

September 1, 2022

Sandbox vs themepark

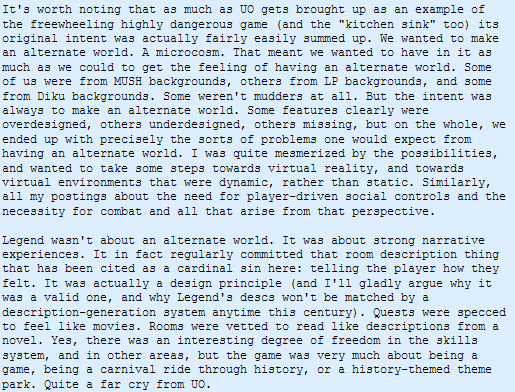

I just watched a couple of videos about sandbox vs themepark games (in particular one by NerdSlayer and another by Josh “Strife” Hayes)… One thing that struck me about the ways players often talk about this (because at this point the history is so old) is that people think of sandbox as the older version of MMOs, and themeparks as newer. But that’s not right – sandbox is not the older form.

Sandboxes are the evolution of themepark MMOs, not the antecedent.

Part of the reason why this isn’t clear is because most players today haven’t played what themeparks were originally, back on the text virtual worlds called MUDs that led directly to MMOs. Given that I suspect I am partly to blame for these two words having currency in the first place, I thought I’d put in my two cents.

MUDs had more “species” than MMOs do today. Caveat: I’m gonna really oversimplify this history here. If you really care, the MUD Wiki on Fandom, started in the wake of the great Wikipedia purge of MUD content, has you covered. At peak in the early 1990s, MUDs had mostly abandoned some of the older sorts (such as “talkers” and “scavenger hunts”) and solidified around a few types.

There were creative worlds such as MOOs where anyone could build anything. Today’s inheritor to this tradition is something like Second Life. Maaaybe Roblox could be considered this, but really Roblox is more oriented around making games than any MOO was.

Many many MOOs ended up less about creativity than they were about just hanging out – basically, the progenitors of social worlds ranging from Habbo Hotel to There.com, and eventually even the hellsites known as Facebook and Twitter.

There were pure roleplaying environments, usually on MUSHes — an activity that these days happens more on Discord probably! Or in GTA Online, weirdly. These usually had LARP-style combat, with mutual-consent style systems for interaction.

There were a few roleplay combat MUDs like Armageddon where you had to apply to even be allowed to play, with a full roleplaying background. They had all the gameplay of the combat games, but you could be banned for breaking character!

WoW introduced the “quest-led” game

WoW introduced the “quest-led” gameThen there were pure hack n slash games, the Diku model but also most LPMuds. These were about starting out at level 1, going to zones for your level, killing mobs to lvl up, then off to the new zones that you could now handle with your increased power. While there were tough encounters (the “raids” of their day) the levelling was the principal gameplay. There wasn’t usually a major narrative element there, though – it wasn’t until World of Warcraft that we saw what I call the “quest-led game.”

Combat MUD zones were assembled more or less carefully to supply the right level of challenge for players or groups of a given level range, reward with gear of the appropriate power, and were assumed to be “run” over and over until you got diminishing returns. Each zone was often fictionally themed, and usually they made no sense sitting next to one another. If you want to analogize to a “land” in a theme park, you are really not far off at all. And hence some of the origins of the term…

Earlier in MUD design, these zones even “repopped” all at once. That is to say, players ran in, and killed stuff, and the zone respawned all the mobs at once, on a timer. It was like resetting a little stage-play; the NPC actors hit their marks and reappeared at their start location. It was actually seen as a notable innovation when individual mobs repopped on their own timers. Why did something like that come to be? Well, because many of us who were making MUDs wanted more… realism. More immersion.

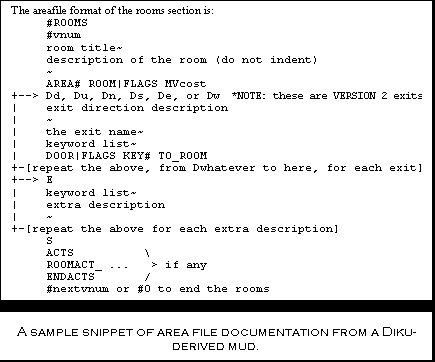

Here’s where the history gets interesting. MOOs and LPMuds were highly scriptable – the former exposed it to users, the latter to builders. But either one was radically different in that way than the most popular game engine, which was the Diku style (we called them “codebases” back then).

Dikus were entirely hardcoded. All the content in the game was just data in fields. And that meant you had to be a programmer who knew how to code C on a Unix machine to add any new behavior to the system. On the flip side, adding data was really easy. On MOOs and LPMuds, you had a lower barrier for adding features, but you also had a higher barrier for “just making content.” Most Dikus could, with minor text editing, share their zone files, because they almost all played exactly the same!

(Ironically, the high barrier for LPMuds actually led to something similar, where because adding consistent functionality to games was hard, people released “mudlibs” of functionality, which resulted in lots of clone games there too).

As you might guess, pretty soon this led to more Dikus than any other type of MUD. But it also led to… envy. LPMuds usually pioneered the cool features in combat MUDs, because they could. They also had (gasp!) quests. Not a new idea, of course…Quests had existed in the earlier MUDs predating the whole LP/Diku/Tiny ecosystem… they were in fact implicit in the scavenger hunt model that went all the back to gathering items to put in a display case in Zork; and present in the design of MUD2 (it had eight of them by 1991, and you had to solve some to become a wizard).

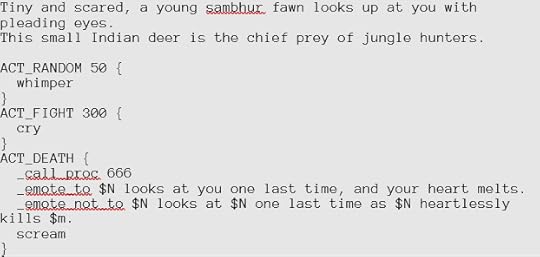

So… DikuMUDs started to add scripting systems, which were generally much more limited than the ones on LPMuds, but fit better with the whole “fill out some rows in a form to add content” development model. Some of this was used to just add nicer NPCs, with conversations, reactions to the environment, etc. But on a few Dikus, it led to making quests too, and it was actually a lot easier to build quests in a “quest system” than to one-off hand code them in an LP mudlib that didn’t implement a “system” for it.

I played on Worlds of Carnage, the first DikuMUD to have scripting like this, and then worked on LegendMUD, which was one of the very next to have scripting – and Legend’s was quite a bit more powerful, apparently.

Carnage is the first Diku game where you really see stuff comparable to quests from World of Warcraft. But it was still very much a Diku! We would sit at the fountain waiting for the spider queen or whatever to repop, which we would check by typing the HUNT command over and over. Then we’d zoom over and kill it in order to maximize our XP per hour. But you could also have a newbie sword that talked to you and gave you advice, or visit a zone based on Romeo and Juliet full of quotes from the play… and kill ‘em all. The scripting on WoC made for better combat too, because you weren’t stuck with just the built-in combat AI for your enemies. AI had more sophisticated combat tactics, because designers could add fresh behaviors to the monsters.

A bit of ACTS scripting from LegendMUD

A bit of ACTS scripting from LegendMUDOn LegendMUD, though, we chased after something else. We pushed the Diku style to add things like… a tavern where you could play blackjack. An entire instanced Last Man Standing minigame. (Pretty sure we lifted that from an LPMud). An out of character lounge where you could attend a lecture series. When a famous player character retired, we could create a bot with their name AND give it all the catchphrases and RP the player had developed, and set it loose.

And above all… quests. Real ones. Stuff that in many ways was quite a bit fancier than what WoW eventually did. This, in fact, was what my signature design style was. Highly narrative, intricate puzzles, and immersive storytelling. It would take a looong time before any MMORPG had anything comparable. If you follow that link, you’ll see open world events occurring as the quest proceeds, done without zone or quest locking, etc. Heck, there was one quest that redid the entire zone spawn.

These were absolutely “rides” the player went on. And I loved them, and loved making them. But they were also a ton of work. And we and other MUD designers were wondering how to get more of this stuff to happen without having to hand-code it all.

Enter “simulationism.” We used the term actively on MUD-Dev back in the day, making the distinction between simulation and “stagecraft.” Simulationism was the idea that you could get the MUD’s basic behavior to the point where cool stuff happened organically. MUD2 had far more simulation than MUDs did in the 90s… or any MMOs today!

A key inspiration in the mid-90s was a game called DartMUD, which featured farming! And crafting! Crafting in other games was mostly one-off stuff tied to quests, or really simple magic item creation. DartMUD tried for a fuller player economy.

The state of the art has moved on so far that it’s hard to convey how important the idea of “let’s make these behaviors generic” was. An example from a bit later, from EverQuest 2: they had dogs that chased cats. Simulationism says “dogs dislike cats, and attack them. Cats flee when attacked by dogs.” In fact, it says “mobs have hates, and aversions.” It’s generic. But the old scripted way was hand coded, so it only worked with that cat and that dog.

In fact, EQ2 did in fact just hardcode some cats running a loop around the city, with some dogs running the same loop a few feet behind them, and called that “virtual ecology.” Contrast that with Ultima Online, a simulationist game where wolves actually did hunt rabbits.. and at first, the rabbits learned from the experience, and got stronger!

When people today say sandbox versus themepark, they mostly mean simulationism versus stagecraft. WoW is a giant amazing piece of stagecraft. So is FFXIV. But Eve is basically simulationist. The tradeoffs were evident early on.

Vaguely “themeparky” content in UO

Vaguely “themeparky” content in UOSo simulationism was born as a way to make fantasy worlds richer, more immersive… in a sense, to “make the ride better.” Despite the knock against it today, it was not seen as a way to offload the effort onto players – back then, that’s what MOOs were for. In fact, UO was fully intended to have the same sorts of quest content that LegendMUD did. You can even find the bones of it – a hedge maze here, some inscriptions in a dungeon there. But we simply did not have time to make any of it, and so you got a freeform “sim world.”

You might enjoy this MUD-Dev post from 1998, which contains boggling moments like “nobody’s really tried a good storytelling MMO” and astonishment that “there’s now an EXCHANGE RATE between UO gold and real world money…”

Contrast this to EverQuest. EverQuest was based on Diku gameplay, end to end. At launch, it had no quests, really, despite the name. Zones had level ranges (though infamously, lots of “zone sweeper” mobs). It famously only added any crafting because the dev team saw it in UO during beta. Today some folks like to say it is “sandboxy” but I’m here to tell you that it was absolutely a Diku-style themepark, of the pre-scripting period.

Hence why I say that to some degree, the terms are my fault. Not that I coined them, of course; the concepts were very much in the air.

The result: when we put linear narrative quest content into Star Wars Galaxies, we called those portions of the map where those narratives lived “themeparks.” We didn’t have anywhere near enough of them, because ironically, we didn’t pick up the Diku lesson and have nice templatized quest systems.

But then along came World of Warcraft, and the whole game was linear narrative quest content. How? By spending around five times more money than any other virtual world developer ever had in the history of mankind. Before WoW, you played a Diku-style game to kill ten rats. After World of Warcraft, you had a quest to kill ten rats. It seriously changed everything, because both sandboxy and themeparky games had a problem with guiding players.

It’s hard to get across how big a revolution that was. We had chased simulation in part because of cost and scalability, which was a horrendous problem for us all, a problem that both Josh Hayes and Nerdslayer specifically called out in modern themeparks. And a problem EQ blithely inherited.

Now, WoW made MMOs accessible by fundamentally making them linear. Oh, not totally. But classic WoW actually punished you for leaving the quest line. WoW was less explorable at low levels than vanilla EQ, for example, precisely because of how carefully and well done the level scaling of content was.

Which brings me to the other terms I used to use: “worldy” versus “gamey.” The MUDs that wanted to seem more immersive, more like an alternate world, they didn’t color-code your opponents (there was a “consider” command but you had to invoke it manually). They definitely didn’t color code your gear. You didn’t march through “progression sets” of gear at all, really. A lot of gear was easy come easy go, actually. There was a general design consensus that even if a MUD was telling a story in its quests, the world was definitely not “your story.”

It was a world. Worlds do tend to be larger and more confusing and less approachable than games, for sure.

One last thing – these days, because UO set the template for “sandboxes,” and then Eve reinforced it, a lot of people identify sandbox gameplay with ganking, full player vs player environments. But they aren’t equivalent. UO had that for simulation reasons. Galaxies did not. Any given game can decide where to draw that simulation line. UO was trying to solve governance problems using simulation, out of a belief that to do it by controlling players would be too expensive. We were mostly wrong.

I say mostly, because social media today shows we were partly right also.

Bottom line: sandbox does not equal PvP combat.

These days, if you are a hardcore enough aficionado of online worlds, you might see reference to the term “sandpark,” often applied to games like Runescape, Black Desert Online, or ArcheAge. That definition is actually what sandbox meant originally. (Runescape at launch was basically very much like UO btw.)

You can build linear narrative themeparky content on top of a rich simulation. And sandbox does not have to be devoid of content. But it is impossible to do the reverse. Linear narrative themepark stuff is by definition breaking the rules of the sim.

Cooking in Sword Art Online is just one example of the way fiction assumes simulationism in depictions of online worlds.

Cooking in Sword Art Online is just one example of the way fiction assumes simulationism in depictions of online worlds.Today, that simulationist impulse is visible in Minecraft. In Roblox, which is built on a physics sim, at heart. In No Man’s Sky and in Fallout 76. But it’s also visible in the Holodeck, or in anime like Sword Art Online (which was directly inspired by Ultima Online!).

In fact, it’s visible in pretty much every other fictional depiction of online worlds. When we dream of alternate virtual realities, they are always simulationist, because the whole point of dreaming is to dream of richer worlds and richer experiences, ones with more internal consistency.

This doesn’t mean that the guided onramp, the clear progression, and the crisp goal-setting of themeparks is bad. Hardly. It’s necessary for broader audiences. Even Minecraft has a much clearer starter set of goals than UO did. But!

Sandboxy stuff – worldy stuff – simulated stuff – is how your themeparks get better. And the biggest reason why the themepark line has dominated is because it tackles mostly solved problems, compared to building a true alternate world. It’s stuff that single-player game designers know how to do. Breadcrumbs, dialogue trees, cutscenes, progression paths. Expensive, but at heart predictable for the developer. Alas, also for the player, after a few run-throughs.

Me personally… I’ve been visiting these worlds for thirty years. I was done with predictable a long time ago.

August 12, 2022

New paper applies predictive processing to “what is fun?”

This paper on “Mastering uncertainty: A predictive processing account of enjoying uncertain success in video game play” is very worth a read if you are interested in the frontiers of figuring out what “fun” is. Luckily for me, it doesn’t say I’ve been on the wrong track for decades.

It does raise interesting questions given its framework — I’d love to see slot machines explained — though there is some stuff on affect that likely ties in. It also teases out some of why I have never felt comfortable with the “flow = fun” equation.

/

Another interesting intersection with other material would be motivations (a la Bartle/Quantic Foundry) and personal goal-setting. Players DO grind, after all, as they optimize, and tho the paper mentions people don’t get stuck in “popping bubble wrap,” they do for a lot longer than one would expect.

For me the answer to that ties back to the lemma/heuristic model of pruning possibility that is usually discussed in the context of “what is game depth.” I’ve come to see forward strategy and perception of depth as being about indeterminacy and a sense of “victory parity” tilting back and forth as we project. There’s something to tease out in that plus motivations plus this paper that could be useful in thinking about how to construct game metas in particular.

Anyway, I encourage the read. It ties nicely to other work such as OpenAI’s RND.

One of the niftiest parts of my career has been seeing pieces of my work turn up as building blocks for others (such as AI systems trying to mathematically implement Theory of Fun). Always feels good when your stuff is built on. Nothing gets to stay at the pinnacle for very long, but getting to be a piece of foundation is a pretty cool and a lot better than the alternative.

Dan Cook also has thoughts on this paper that are worth a read, and open yet more rabbit holes to explore.

Neat paper on psychological motivation to reduce prediction error in player models of cause and effect. References the (new to me) model of predictive processing from psychology. With math?

— Daniel Cook (@danctheduck) August 12, 2022

Linking earlier work from working game designer literature that is highly related https://t.co/hTyASnlbr3