Raph Koster's Blog, page 3

June 18, 2022

GLS 2022 Keynote posted

I’ve posted up the slides for my Games Learning + Society keynote that I gave at UC Irvine on Wednesday morning. It’s more talk about metaverses, with some cautionary notes. Those of you who have read recent blog posts will find a decent amount of it familiar. Click here to take a look!

I’ve posted up the slides for my Games Learning + Society keynote that I gave at UC Irvine on Wednesday morning. It’s more talk about metaverses, with some cautionary notes. Those of you who have read recent blog posts will find a decent amount of it familiar. Click here to take a look!

October 21, 2021

Ownership: How Virtual Worlds Work, part 5

Let’s get one thing out of the way first. Ownership of anything digital is illusory, and always will be.

Then again, it’s illusory in the real world, too. Ownership is a convention, not physical reality. This is why we have sayings like “Possession is nine-tenths of the law,” which basically means “you can claim you own something all you want, but if you don’t physically have the object, it’s pretty hard to enforce.”

In digital settings, of course, you never physically have anything. At best, you have a physical container of data.

Data is differentThe characteristics of data are quite different from physical objects:

It does not exist without a physical container of some sort, whether that be a piece of paper, a book, a CD, a hard drive, or cloud storage.It is perfectly replicable. By definition it can be duplicated infinitely.If I send you data over the wire – even if it’s encrypted! – I am basically handing you a full copy of it, which you could save off (controversies over this long predate the more recent “right-click save as” debates with NFTs). After all, to show it to you, we have to decrypt it on your machine, which means you have a copy of it in the clear.Once upon a time, Stewart Brand said “information wants to be free.” That wasn’t just a philosophical statement. It was a literal description of digital data, which is effectively an infinite resource.

The history of computing is full of examples of trying to stuff this genie back in the bottle. It’s why we have software licenses, EULAs, subscriptions, dongles, DRM, and the DMCA. Oh, and everything about crypto. They are all about turning an infinite resource back into something scarce, recreating a non-digital world.

Lest we forget, the other half of Brand’s formulation was “Information also wants to be expensive, because it’s so valuable. The right information in the right place just changes your life.”

Economists have terms for these differences. To oversimplify, goods that only one person can have are called “rivalrous goods”, and goods that many people can have at the same time are“non-rival.” There’s also the notion of “Veblen goods” which are items that have increased value just because they signal status. Think of a really fashionable shoe – they aren’t any more useful than any other shoe, but they are more “valuable” because they are high-end, scarce, and fancy. You get the fancy shoe because it shows off the fact that you can get one.

All digital content, like all information, is effectively a non-rival good. But most ideas about “decentralized object ownership” or about “virtual items” in general are trying to turn them back into rival goods or even (in the case of NFTs) Veblen goods.

(Those who are more politically inclined among you may choose to veer off tangent here, and ponder the ironies in humanity taking the first truly infinite economic resource we have, something actually capable of creating an economy of abundance, and hemming it in with scarcity.)

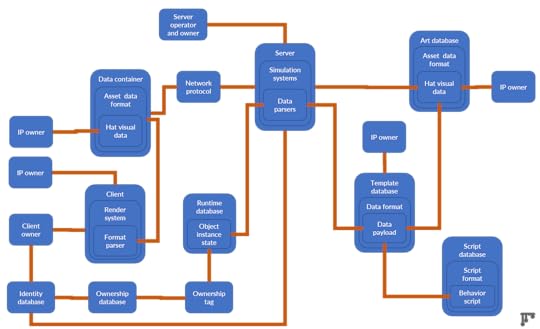

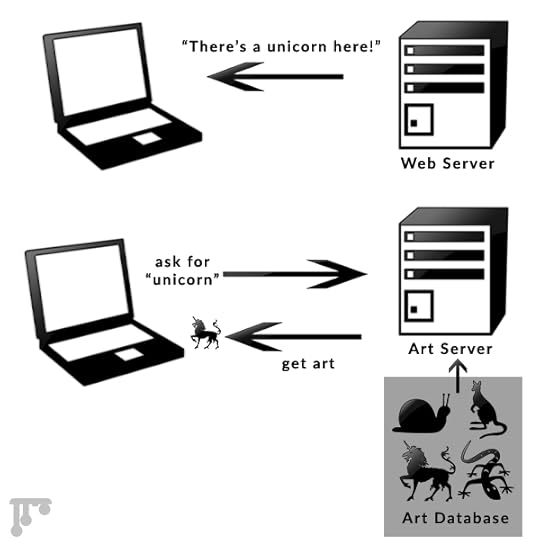

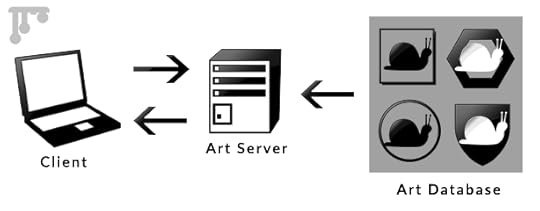

Most people don’t even know what ownership isOver the last few articles, I’ve been sharing diagrams like this one:

These pictures have illustrated how the various conceptual pieces of a virtual object connect together. But all of these diagrams are missing a lot of connections that carry enormous weight – connections that aren’t all technical.

Here’s an actual map of a digital object set up for a cool distributed metaverse:

Still simplified, I’m afraid! Notice, for example, that it leaves out the question of who owns all the databases along the way.

In earlier articles, I emphasized that the data that made up a virtual sword existed in a format, and formats themselves then demand a system environment with a system that knows what to do with data in that format, and when you send it to the client, it needs another chunk of data, the art which is also in its own format and requires another parser to interpret it so it can be rendered, and so on.

All of this should sound familiar to you because it’s much the same as when you read a book. A story is data contained in a physical book. We shouldn’t forget that when you buy a book, you own the container and not the content.

Here’s another example. Let’s say you listen to a song. A song is data contained in a physical container. Here’s how that works:

Someone wrote a song. This is something someone can own, thanks to intellectual property law, most specifically copyright.Someone then performed the song. A performance is actually the process of a human manually parsing the information data of a song, and turning it into a different set of data. This is also something someone can own.Someone recorded it. This recording captures the owned performance as data, and puts it in a container. (This container, the “master recording,” is what burned in the Universal fire of 2008, which destroyed the original master copies of countless classic albums). This is also something someone can own!The master is then rendered into different formats. These formats are each associated with a container. For a vinyl record, the format is literally a wiggly groove in plastic. For a digital recording, it’s a set of bits and bytes.Then the data has to get put into the matching container. Vinyl records. Cassette tapes. CDs. 8-track tapes. MP3s. Each of these is a container for the format for the recording of the performance of the song. And yes, someone can own this too!Then you buy one. You own the container. But each container is matched to a playback device. An MP3 is useless without an MP3 player which knows how to parse the data in the container and turn it back into the recording of the performance of the song.And once you have the vinyl of, I dunno, BTS or Taylor Swift’s latest hit, you tell yourself that you own the song. But you really don’t. A songwriter does, a music publisher does, and so on. You just own a container.All of this is based on precedents such as “the right of first sale,” which is basically a legal rule saying that you can sell the container holding a song you bought to someone else; as well as the entire notion of copyright, which is all derived from the Statute of Anne in 1710, which basically invented the idea that the data and the container had different sorts of ownership.

What about virtual items?Digital objects have the same subtlety as the above, complicated by these facts:

They enable perfect copies at every stage of the chain. In fact, they make perfect copies at every stage of the chain. They even leave these copies scattered all over your hard drive!The server side can transfer the notion of ownership by just updating a column in a database. In a typical game, you never owned anything. You paid for the right to access a server which happened to keep some records linked to your character id.To quote myself from an article from many years ago,

A digital item is made up of database entries. It’s bits and bytes living on a server. It may have been made by the same folks who operate the server, or it may not have. It may have been uploaded by someone who pays for the privilege of manipulating the data on the server, or it may have been uploaded by someone who gets access for free.

In some cases, these bits and bytes might be a unique arrangement of data, in which case it is probably copyrighted by someone. In some cases, it may actually be a record of activity instead, in which case and under some laws, it might be subject to privacy laws instead.

In no [legal] sense are any of these database entries “objects.”

As a result, digital stuff actually challenges the notion of ownership itself. You can’t have a doctrine of first sale for data, only for its container. Instead, we live in a world of software licenses, which has gradually evolved into subscribing to every bit of software that can get away with it.

Further, because “software eats everything,” we are seeing that license regime creep the other way and start making containers into something protected by copyright instead of being objects.

To quote myself again, “copyright controls who gets to make a buck.”

CopymessThe definition of copyright for a given medium has never been particularly pure – what is legal and what is not has entirely depended on who had better lobbyists at the time. It’s why the music industry managed to get a royalty on every blank cassette sold, but the software industry didn’t pull off the same trick with blank floppy discs. It’s why there’s a broader concept of “moral rights” in European copyright law than there is in the US legal system.

Where does this leave you with digital object ownership? The only real answer is “uncomfortable.” Because even when you explore cutting edge stuff like NFTs; delve into the controversies over right-click-save-as, pump-and-dumps, or energy consumption; whether you admire the tidy Veblen good markets around high end generative art NFTs or not – you still run headlong into the fact that all that tech is going to collide with copyright law in a messy way.

Put another way: if you get a cool branded digital object in MegaWorld, and you move it to NiftyWorld in the metaverse… some rightsholder may tell you “no, you can’t do that, because we don’t have a publishing agreement with NiftyWorld. MegaWorld has exclusive rights, and I don’t care that you own this.”

And there is always a rightsholder. The law creates that rightsholder by default the moment the work in question is created.

Laws are social constructs, of course. They can change and evolve. Our own relationship to songs and stories has changed tremendously as the technology of containers has evolved. Tech does not replace laws… but it does reshape them. Old hands at virtual worlds have known that viscerally ever since the first experiments in allowing players to govern themselves failed in spectacular fashion. (cw: rape).

In other words, ownership is actually just a tiny category in the larger issue of governance. It’s a huge category error to believe that tech can solve governance. But that hasn’t stopped idealistic technologists – myself included! – from trying.

But at that point, we’re done talking about “how virtual worlds work”… and instead, we’re talking about “how people work when in virtual worlds.” And that’s a whole family of topics for another day.

October 14, 2021

Object Behaviors: How Virtual Worlds Work part 4

Making objects in a virtual world actually do something is way harder than just drawing them – and as we have seen, drawing them is already fraught with challenges.

Items as pure dataOnce upon a time, in the old days of DikuMUDs, every object in the game was of a type – ITEM_WEAPON, ITEM_CONTAINER and so on. These were akin to what I referred to as templates in the last article. But they were hard-coded into the game server.

If you added new content to the game, you were limited by the data fields that were provided. You couldn’t add new behaviors to a vanilla DikuMUD at all. That item type defined everything the item could do, and a worldbuilder couldn’t change the code to add new item types.

To extend the behaviors a little bit, there was a small set of “special procedures” also hardcoded into the game – things like “magic_missile” or “energy_drain.” The slang term for these was “procs,” and to this day players speak of weapons that “proc” monsters. You could basically fill in a field on a weapon and specify that it had a “spec proc,” choosing from that limited menu.

If we look back at the previous article, and think about what this means for portability of object ownership, one fact jumps out at us: the functionality of a given object in a DikuMUD is inextricably bound up with the context in which it lives: the DikuMUD game server. There wasn’t any code attached to the item that could come with it as it moved between worlds. Instead, it really was just a database entry. The meaning of the fields was entirely dependent on the game server.

Attaching behaviors

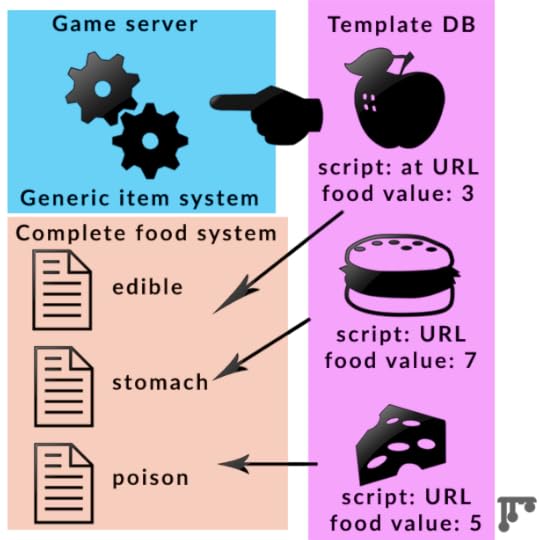

Attaching behaviorsModern worlds are more flexible, thank goodness. The concept of attaching a block of script code to the individual item opened up the ability for an item and its intended behavior to both be “data” in the database. This allowed people who were not the operators of the world to add functionality.

Each object in the database maintained a list of the scripts attached to it. When this tech first came along, the scripts were literally placed directly in fields on the object itself.

Later on, they became their own data type, and they were instead linked to the object template and the object instance. This allowed scripts to be attached and detached from objects on the fly.

This was an architectural revolution: suddenly a behavior might get attached to anything. You could share behaviors across objects. You could mix and match behaviors from different sources and use them as building blocks to create more sophisticated gameplay.

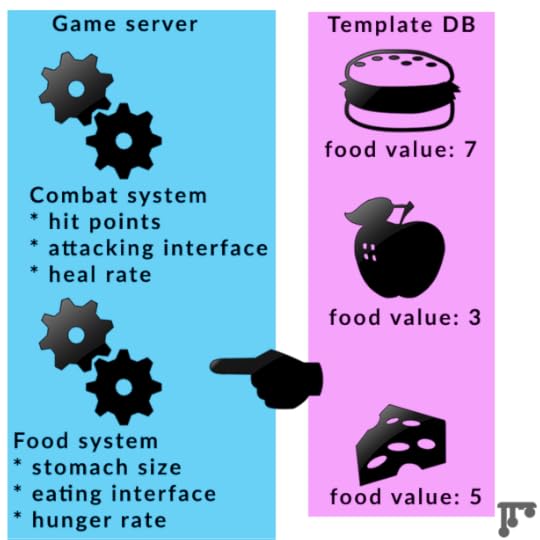

There are still limitations. A behavior doesn’t carry a whole game system with it. Each script still has dependencies on other scripts. For example, let’s say you have an apple. You want it to be food, so you might attach this behavior to it:

When this object is eaten{ Figure out how much food value the object has Increment my stomach’s fullness by that much Make sure I don’t go over the max stomach fullness! Delete the eaten object}That seems simple… but it has assumptions:

Where does “eaten” come from? That implies a whole UI, the concept of food in the first place, etc.If the object has a food value, but it wasn’t food until this behavior was attached, then where is the food value stored? Are there generic empty fields on the object (“since the food script is attached, check storage box #1?” How do you pre-populate it? Do scripts need to be able to add fields on the fly?Wait, the player has a stomach? Is that defined in the player template? If I am adding “food” as a concept via script, then probably not. That means I need to add “food eater” as a script to the player, and have that script add the necessary fields.The stomach has a max? Where is that defined?Worse… what if you want to add poison to a food? (The answer, by the way, is overloading the event handler for the “eaten” message, which then means you need to be able to define script precedence…)

Even worse… what if the world you are importing this into is an RTS, where there isn’t an avatar in the first place?

If you tried to carry just the food script from one world to another, it would utterly fail to work, because all those assumptions are dependencies.

Object portability isn’t entirely hopelessPeople often think you could just set up mappings between the values of fields in one game and the fields in another game. And indeed, we have had things like “compatible player files” since early home computer RPGs in the late 1970s and early 1980’s. But we should not underestimate the magnitude of the task of figuring out what value a cooked pie from Breath of the Wild has in Halo — or mapping every game to every other game.

There are no standards right now for “what things can do” in a virtual world, and we shouldn’t want them. The act of setting the standard is also setting the limit, which would curb creativity enormously. There’s far too much possibility to be explored still.That said, since scripts are just data – just text! — you could load them from a remote site. If there’s a popular set of scripts that lots of people load from a common location on the web, then standards could start to emerge based on actual usage. As long as scripts could actually add data fields on the fly, as long as scripts could come packaged with all dependencies internal, and as long as things like “eaten” could be just messages to the object – you could indeed share behaviors across worlds.

We know this works, because we’ve built it before, including at my previous startup Metaplace.

Ironically for fans of decentralization, though, the literal decentralizing of the script locations results instead in centralizing the point of failure. If that script has a bug, everyone’s eating stops working. So instead, you need to make copies… maintain version history… worry about forks… build consensus on how to extend or change the behavior…

We are back to “tech is for people”What used to be a technical problem then becomes a people problem. It becomes the political challenge of managing open source software projects. With the extra complication that a poisoned apple isn’t like application software. There is no right answer for how it should work!

A sci fi game may want to use this very differently from a fantasy game where witches can enchant apples.The scale for “stomach fullness” may need to be wildly different for a game where you can play anything from an insect to a mammoth.A survival game might want actual nutritional values rather than a single “food” value.A casual title’s gameplay experience may be badly damaged by that degree of complexity.If you can carry food to a new world and eating restores health, that might really unbalance a game where you aren’t supposed to be able to heal at all.This is why carrying object functionality around between worlds is above all a thorny social problem, and item portability in the way that most people dream of it is far more likely to be limited to appearances for a long while. The exception would be cases where there is central control over, or at least strong agreement on, the game design across multiple worlds.

Which leaves us with the largest social problem of them all, one I touched on lightly a couple of articles ago: ownership.

October 7, 2021

Digital Objects: How Virtual Worlds Work part 3

How Virtual Worlds Work

1: Clients, servers, and art

2: Maps

3: Object templates and instances

First we talked about clients and servers; then we talked about maps. Now we are finally at the hardest part of virtual worlds to wrap your head around – not coincidentally, also the aspect that gets people the most excited.

Things. Stuff. Bits and bobs. Widgets. You know: objects.

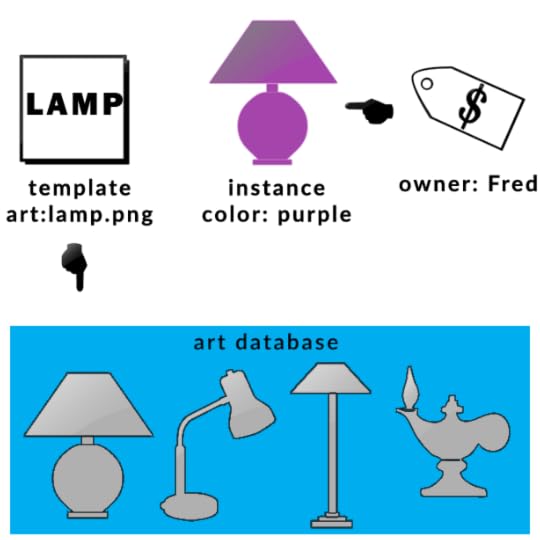

A lot of folks think a digital object is something like this:

Objects might seem simple, but they are actually very complicated. The subtleties lead to confusion about what is possible in online worlds or metaverses – and the answer is both more and less than people tend to think.

Digital paradoxesLet’s start by hitting on some of the core dichotomies that exist with virtual objects:

Appearance versus the thing itself. A digital object’s appearance is not the object. In fact, in a well-architected online world, the object can change appearance willy-nilly because the visuals representing the object and the object itself are decoupled.

Ownership versus possession. There is quite a lot of interest today in digital object ownership, of course. But every digital object is, by definition, stored on a server. Someone owns that server, and can turn it off or wipe the hard drive. Separating the control of the object from the ownership is the main project of NFTs, for example; and yet even NFTs mostly don’t manage it, partly because of…

Data versus code. Typically, a digital object consists of a set of data. Statistics about the thing that describe the functionality it is supposed to have. But that functionality is not generally part of the object. It’s like sheet music, not an MP3 player. It takes code to read the data, and code to make the object do anything at all. Otherwise, it’s just rows in a spreadsheet.

Container versus content. We’ve all run into a movie that our computer’s movie player has trouble with. Those rows in the spreadsheet are set up with specific headers on the columns. Even if you have the code that can theoretically interpret the rows on the spreadsheet, if your movie player expects them in a different order, the movie won’t work. This is a data format question, which I touched on back in the first article in this series. It doesn’t help to have a BluRay player if all the songs in the world are in VHS format only.

The structure of digital objectsIn the real world, when you go to buy a car, you probably have a particular model of car in mind. Virtual objects work the same way. There’s a cookie cutter that defines the object, and there’s the cookie you get when you use the cookie cutter. You can make as many cookies as you like, and they will have basically the same shape.

There are many names for this distinction, but I will use the terms template and instance. The cookie cutter is the template: it defines the shape. An individual cookie is an instance.

If you’ve ever played Dungeons & Dragons, this concept is familiar to you. The Monster Manual defines what orcs are. But you fight a specific orc. And when that orc falls victim to your mighty blade, the “master copy” orc remains in the book, ready to spawn more orcs for future encounters.

The “shape” of that orc is therefore the list of specific bits of data that make an orc different from a dragon. The name is one of those bits, how many hit points it has is another, and so on.

In many virtual worlds, the instance is actually a carbon copy of the template. This means that all instances of a given template are exactly the same. This is done to save on computer storage and memory; the fields that don’t change on an instance don’t need to be on the instance at all! You don’t need to store the name “orc” on every orc – you can just use the name from the template.

On the other hand, if the data or fields can change or vary, then you do need to store it with the instance. Data on templates is immutable by players; data on instances is modifiable. An orc named Fred and an orc named Betty need to store their names individually, and it takes up space. A wounded orc needs to know how hurt it is, because the template only stores what a healthy orc is like.

How many databases?

How many databases?Because of this concept, pretty much every virtual world maintains a minimum of two databases.

One of them is read-only, and is the source of templates. The only people who get to populate this template database are the developers of the virtual world. The other is read-write, and whatever you change is persisted. This runtime database is the one that saves instances.(Even this is a massive simplification. Back in the late 1980s, a virtual world architecture approach was developed in which there were no templates. Every object was unique, and therefore each instance tracked all its data. Instead of templates, you could clone an object from another object, which gave you the functionality of a template. One cost to this approach is that the economy of looking back at the template for information was lost – this style of server was far less efficient to run. What we gained was the ability to create new kinds of objects on the fly. Over time, this evolved into architectures in which the template database can be altered while the world is running, but which do not require every object to know every piece of data about itself. There are lots of more subtle variations, such as the notion of object types which are classifications of sets of object templates… this is a deep rabbit hole).When people speak of decentralizing virtual worlds, this distinction is often one of the things omitted. Which database are you decentralizing? It’s not hard to share template data – text MUDs have been doing it for decades! It gave rise to a phenomenon called “stock mud syndrome,” where MUDs used so much shared template data that it was hard to tell two games apart!

The precedent is even older: the Monster Manual actually is a decentralized template database. Every game table has their own copy of the book. In fact, every adventure module sold is an optional add-on to the template database, because that static DB often holds maps, treasure items, and everything else.

On the other hand, what people seem to want to decentralize is actually the runtime database. That’s the hope for things like NFTs, which are all about instances. And in particular, those people want to decentralize just one field: who owns the instance. We’ll have to come back to that topic later.

Fields aren’t just text

Fields aren’t just textLet’s go back up to those paradoxes at the top of the article. We’ve already established that a given field might be immutable, in which case it lives in the template; or mutable, in which case it has to live in an instance.

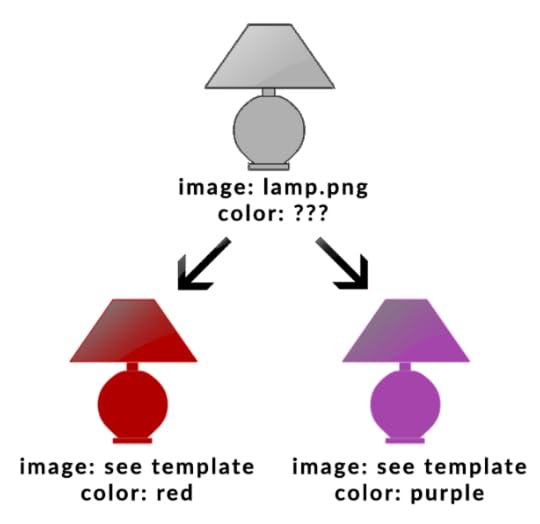

A given field doesn’t just store stats, though. It can store entries that point to another database. The most common use for this is to link a set of stats (such as “orc”) with its appearance (“a 3d model of an orc”).

Back in the first article in the series, I pointed out why this is challenging already – there are many formats for art. But there’s also the question of whether the art lives in the template or the instance – this determines whether it can change or not! Modern character customization systems store the basic avatar in the template, and a set of fields lives in the instance for all those sliders, letting you adjust the height and cheekbones and hair color and whatnot.

You can’t carry runtime customization data like that over to another world unless the template matches. And this is true not just for art-related fields, but for all fields. You can’t carry over your current health to another game if the template for players in that game doesn’t handle health.

So now, our little diagram for what objects look like is kind of like this:

Something worth pointing out: this diagram has an assumption that all the art is in the same database. And indeed, in most games it is, and most online worlds it is. But it doesn’t have to be. If the art field pointed at a URL instead of a database entry, it might be anywhere on the Internet – and in fact, things like web browsers, NFTs, and our platform here at Playable Worlds all rely on that idea.

But we’re not even half done. After all, the lamps in our diagram can’t be turned on and off. In fact, they do nothing at all. Dealing with functionality will introduce a whole new level of complexity… next week.

October 6, 2021

Building the Metaverse session

The redoubtable Jon Radoff from Beamable has been doing a great series of videos called Building the Metaverse on a wide array of topics related to, well, the Metaverse. Today he’s posted up a video where the two of us riff on interoperability, governance, digital ownership, and much much more.

It’s got lots of real talk. Some key bits to whet your appetite:

It’s far more likely that you’re going to replicate aspects of human reality than invent a new human reality.

Governance is not a technology problem.

If you are operating a Cloud AR kind of environment, are you a government?

Everything digital is non-rival… but real world economies are mostly based on rival goods. The whole point of blockchain is to re-create rivalry…

Are we recreating rentiers?

The biggest takeaway I really want everyone to have is “the metaverse is made out of people,” and that we cannot lose sight of the human element in all this. It’s so easy to get caught up in reductionist tech solves — exciting ones, even! — that ignore the wider context. There’s a lot of history to learn, lots of mistakes made, so there’s not much excuse for blind naivete anymore.

September 30, 2021

How Virtual Worlds Work, part two

Last week I wrote about the challenges of moving art between virtual worlds – especially the long-standing dream of moving avatars across wildly different worlds and experiences.

Something I didn’t touch on is whether this is a dream you actually want.

Chasing the wrong dreamsThere are a lot of things people assume they want out of a metaverse which don’t really hold up under close scrutiny.

Do you really want to move your avatar between a fantasy world and a gritty noir world set in the Prohibition era? Even if it shatters all immersion when you head into a speakeasy and someone casts a fireball spell at you?

Do you really want to be in a ten thousand person battle with the latest weapons technology if it means you get headshot by a sniper a mile away that you never got to see, dodge, or avoid in any way?

Do you really want to be able to just walk from one player-created world to another, if it means their distasteful content is clearly visible over your fence line?

What if all these features mean you can’t have a world where you’re actually a sailing ship instead of a person? Or controlling a swarm of beings? Or just playing a 2d puzzle game? Or…

You get the idea. It’s quite easy to arrive at poor architecture decisions because you’re chasing technical dreams that don’t hold up to what users actually want. Above all, we should never forget that the metaverse is for people, because all technology is for people.

Virtual worlds are placesAn MMO, a multiverse, or the future dream of a metaverse, all have one simple thing in common. They are places. Since inception, online worlds have been about representing areas of virtualized space.

In the very earliest worlds, everything was just text. Players moved between individual rooms, each of which described a particular location. They were linked together in a web just like webpages are with hyperlinks.

a MUD map of London in 1889, illustrating the room-based model

a MUD map of London in 1889, illustrating the room-based modelGradually, we got worlds with graphics. At first, the solution was to just display a picture in each room. But eventually, we were able to move around on a continuous map, first using 2d graphics and later using modern 3d rendering.

It didn’t take long for these graphical worlds to become so intensive and complex that it took a suite of computers to handle the continuous map for just one world – technology we invented to launch Ultima Online exactly 24 years ago this week, back at my first real game industry job.

By definition though, any multiverse (and remember, a metaverse is just a more advanced version of a multiverse) is going to involve many very different places. You don’t want those all to exist on one map. You’d end up with Fairyland butting up against World War II.

Aesthetics isn’t the main reason this is bad. The real issue is that players won’t be happy if they were expecting a nice peaceful tea party with talking flowers, but they took one step too far, and were run over by a Sherman tank.

Different places can offer different experiences, and different experiences is the point of having a multiverse at all. Otherwise, why not just have separate worlds?

Luckily, the older “room” model offers a solution, even though it might seem like a technologically boring one. It’s better to think of these different environments as alternate dimensions, rather than one “reality.” They can be linked via portals just like webpages are hyperlinked. This lets the worlds still fall nicely into the spatial metaphor we’re all comfortable navigating, because it’s the way the web already works.

Maps are maps are mapsThis becomes relevant to metaverse aspirations when you realize there isn’t much difference between the maps app you use for navigating real world highways, and the minimap you use to explore a fantasy world.

In both cases, there is a server somewhere holding map data. The map data might be carefully crafted by a game worldbuilder… or it might come from GIS digital elevation map data. It might have landmarks on it like the Dread Wizard’s Tower… or it might have locations marked with Yelp reviews.

This is where applications that seem hugely different today will converge. When you explore Azeroth in World of Warcraft, your client is updating your location on an invented fantasy map. When you scroll around Zillow in your living room, your client is moving your location on a digital real world map. When you use Waze for up to date traffic info, you are physically moving in the real world, and your movement is controlling a virtual “avatar” on the digital map. And when you hunt Pikachu in PokemonGO, your movement is doing the exact same thing, but the map is a clever mix of reality and fantasy.

You could think of it as a little table like this:

Real mapInvented mapMove only in virtual spaceYelp, Zillow, and pretty much all other apps that annotate real world places.All MMOs.Move in virtual and real spacePretty much all GPS-enabled apps today.All AR games like PokemonGO.The bottom right box also includes much of what is dreamed about in “AR Cloud,” including videos like this dystopian nightmare.

Today, apps like Yelp or Waze use the typical web stack to deliver their content. But as Cloud AR evolves, it is going to quickly become apparent how much real-time data and interactions matter. The right solution for moving digital avatars that interact on maps in real time is and has always been a virtual world server.

(This, by the way, also means that everything we’ve seen happen in video games – whether it be the corrupted blood plague in World of Warcraft or dupe bugs or flying genitalia – is something we can look forward to happening in our real life neighborhoods someday. If you are interested in a sobering look at those consequences, you might enjoy this lengthy talk I gave a few years ago).

How it looks versus what it isYou may recall that in my last article I pointed out that the lack of standards for art is a big barrier to a fully interoperable, standards-driven metaverse.

We have even fewer standards for maps.

Worse… maps change. A lot. People want to change them. Restaurants close. Buildings are demolished. One of the biggest complaints players have about their virtual worlds today is they are basically cardboard stage sets that cannot evolve.

Virtual world maps today mostly work like the art I talked about last time: they are baked into a static form, and then pre-installed on your hard drive with the client. This makes changing them hard, which is exactly backwards for the single commonest use humanity has always had for any place: to build on it.

It’s actually worse than you think: common practice is to ship the map as art. It is literally a sculpture carefully made by an artist. It isn’t even “map data.” It’s a picture of map data, a sculpture of map data.

There is some sort of fallacious assumption many developers have about virtual worlds, where they seem to think the stuff on the client matters. But it doesn’t. I call it “the goggles fallacy.” We get really caught up in the rendering of it all, the way it looks. This is why maps get shipped as art these days even though we have the cloud.

Look: My car is old enough that it has a built-in navigation system with a DVD of maps. It’s hilariously obsolete! Why do we think it’s OK for our metaverse future to work this way?

A client can display a map – and therefore a virtual world — any way it wants. In fact, it should! It should display it in the most useful way for the user. That means we need to get away from the idea of maps being art. They aren’t. They’re data. They need to come down on the fly. They need to be able to change. To evolve. They need to be maps of alternate dimensions and far-flung realities and of downtown Cleveland.

A funny little secret: virtual world operators have always had clients that offered specialized views of what was going on in the virtual world. Density maps, load maps, debugging views, all sorts of things. That’s the right way to think of it all: the player view is just one of many.

Which brings me to where the rubber really meets the virtual road: If everything is data, then we really need to dig into how that data works, how it is structured, how we inform the client of it, and most crucially how the data can mean things.

But that sounds like a big topic, so I’ll save it for another day.

September 23, 2021

How Virtual Worlds Work, part one

Apparently, our recent articles have caused a bit of a stir. It’s been gratifying to see so many folks commenting and weighing in on what we have planned, and the metaverse in general.. One thing that’s really struck me is the enthusiasm for the reinvention of online world technology. Whether a particular commenter is focused on decentralization, player ownership, or user creativity, there’s clearly a lot of interest in new ways of doing things.

Apparently, our recent articles have caused a bit of a stir. It’s been gratifying to see so many folks commenting and weighing in on what we have planned, and the metaverse in general.. One thing that’s really struck me is the enthusiasm for the reinvention of online world technology. Whether a particular commenter is focused on decentralization, player ownership, or user creativity, there’s clearly a lot of interest in new ways of doing things.

In my experience, whenever we are exploring new ways to approach old concepts, it’s important to look backwards at the ways things have been done before. A lot of these dreams aren’t new, after all. They’ve been around since the early days of online worlds. So why is it that some of them, such as decentralization, haven’t come to pass already?

The answer lies in the nitty gritty details of actual implementation. A lot of big dreams crash and burn when they meet reality – and some of our most cherished hopes for virtual worlds have pretty big technical barriers.

That’s why I am writing about how virtual worlds work today, so it’s easier to have these conversations, and all reach for those dreams together. And I’m going to try to do it with minimal technical jargon, so everyone can follow along.

This is a big topic, so today we’ll confine ourselves to just one part of the virtual world picture: what you, as the user, see.

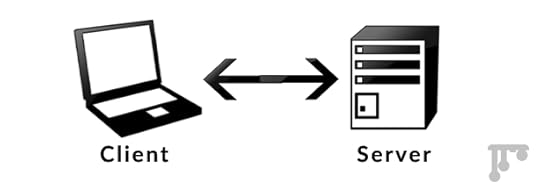

Clients over here, servers over thereLet’s start with the simplest picture that most people have of a virtual world. You have a client over here, running on a local computer of some sort. And somewhere out in the Internet, there is a server.

This picture is deeply misleading. It gives the impression there’s a nice clean divide between these two things, when that isn’t the case at all. Everything is always more complicated than you think.

You would think that a client simply displays whatever’s happening on the server side. And once upon a time, that was true: back in the text days, the server actually sent the text over the wire, and the client just plastered it on your screen. It’s similar to Stadia or Netflix today: the server sends pixels over the wire, and the client just plasters them on your screen.

But virtual worlds haven’t worked that way for a long time now.

Instead, when you get a game client, it actually comes with all the art. The client is just told which piece of art to draw where. This dates back to when we couldn’t send art over the wire because it was just too big. (Of course, these days, you have, on average, around 2500 times more bandwidth than we did back when we made Ultima Online.)

So let’s update the earlier diagram. It’s really more like this:

But it doesn’t have to work that way. Pieces of art are all just data. And something we should bear in mind as we keep going through this article (and the upcoming ones in this series), is that you can always pull data out of a box in the diagram, and once you do, it can live somewhere else.

For example, when you connect to a webpage, the art data needed to draw logos and photos and background images isn’t baked into your browser. It’s on a server too. The client gets told “draw this item!” and instead of loading it off your local hard drive, it loads it over the wire (and saves a local copy so it’s faster next time).

But — and this is a big but — this only works for the web because we have some technological standards. Every browser knows how to load a .jpg, a .gif, a .png, and more. The formats the data exists in are agreed upon. If you point a browser at some data in a format it doesn’t understand, it’s going to fail to load and draw the image, just like you can’t expect Instagram to know how to display an .stl meant for 3d printing.

This is a crucial concept, which is going to come up again and again in these articles: data doesn’t exist in isolation. A vinyl record and a CD might both have the same music on them, but a record player can’t handle a CD and a vinyl record doesn’t fit into the slot on a CD player (don’t try, you will regret it).

Anytime you see data, you need to think of three things: the actual content, the format it is in, and the “machine” that can recognize that format. You can think of the format as the “rules” the data needs to follow in order for the machine to read it.

The thing about formats is that they need to be standardized. They’re agreed upon by committees, usually. And committees are slow and political… and of course, different members might have very different opinions on what needs to be in the standard – and for good reasons!

One of the common daydreams for metaverses is that a player should be able to take their avatar from one world to another. But… what format avatar? A Nintendo Mii and a Facebook profile picture and an EVE Online character and a Final Fantasy XIV character don’t just look different. They are different. FFXIV and World of Warcraft are fairly similar games in a lot of ways, but the list of equipment slots, possible customizations, and so on are hugely different. These games cannot load each other’s characters because they do not agree on what a character is.

Moving avatars between worlds is actually one of the hardest metaverse problems, and we are nowhere near a solution for it at all, despite what you see on screen in Ready Player One.

There have been attempts to make standard formats for metaverses before. I’ve been in meetings where a consortium of different companies tried to settle on formats for the concept of “an avatar.” Those meetings devolved into squabbles after less than five minutes, no joke.

But even simple problems turn out to be hard – like, say, “a cube.”

VRML and its successor X3D were attempts at defining formats for 3d art for metaverses. Games tend to use different specific 3d art formats. 3d printers use other ones. These days, 3d assets by themselves – just the formats for “a cube” – have narrowed down to a relatively small set of common formats. By which I mean “only” hundreds of them.

One of the things that is intrinsic to the dream of a metaverse is democratizing and decentralizing everything. But there’s a harsh reality shown to us by the web: the more “formats” you need your “machine” to be able to “play,” the harder and more expensive the “machine” is to make.

And that means only groups that are already rich tend to make “machines.”

That’s why we only have a few web rendering engines, and they’re all made by giant megacorps. Under the hood, even Microsoft Edge is actually Google Chrome, and every single browser on your iPhone is actually Safari.

This has substantial implications for a democratized metaverse. It’s pretty clear, for example, that Epic is trying to make the Unreal Engine into one of the few winners — it’s part of why they are not just an engine company, but also buying 3d art libraries.

So can we just pick a couple of formats and stick with them?

Part of the reason why different formats are used is because subtle differences are useful for different use cases. Game engines today favor efficiency. Because of this, they can import a wide range of common 3d file formats from 3d modeling software. The engines then convert them internally into another format, often compressing, combining, and in general optimizing the data. That conversion process (Unreal calls it “cooking”) is not fast. It’s not real-time. In fact, it can take hours. And the result, by the way, is not compatible between engines.

Needless to say, if you are trying to make a real-time experience, you can’t realistically fetch data from a remote site in a more generic format and end up having to cook it on the client side before loading it. Everything would screech to a halt.

All that just to draw a cube. And we’ve already run into very serious implications for the metaverse dreams of democratizing content creation, preventing monopolization or corporate dominance of the metaverse “browser” market, and enabling interoperability between worlds.

You would think that the other parts of a virtual world might be simpler than this problem. I’m afraid not. A cube, with all the above complexities, is actually the simplest part of the entire equation.

Everything else is much, much harder. And we’ll talk about that next week.

— Crossposted from the Playable Worlds website.

September 16, 2021

But First, the Game

In the last couple of articles, I might have spent too much time talking about big buzzwords – metaverse this and persistent state technology that. I get it, it can be confusing!

If I were to start throwing around even more technical stuff – like, how we drive Node.js from our highly-optimized C# server backend to implement a TypeScript-based scripting environment so gameplay code can be reloaded without a build or restart – well, plenty of people’s eyes might glaze over.

So instead, I want to talk about why our overall tech approach makes for better lives for our developers and better games for our players.

A fundamental truthTo make better games, we need to enable developers to iterate faster.

Slow iteration means fewer chances to refine gameplay. It also means higher costs, which leads to greater conservatism in game design; higher costs make devs less inclined to take risks.

When we look across the history of games, we see periods of enormous innovation come along whenever costs fall. Flash games, mobile games, the availability of Unity and Unreal: all of them led to new experiences, because cost barriers fell.

Well, MMOs have not had that happen. If anything, barriers just keep going up.

The reason why we’ve built a metaverse platform is because, by its nature, it brings barriers down.

An exampleWe have this philosophy that “everything about the game should be data.” That’s a fancy way of saying that even the game rules are done in “softcode” or “script” rather than hardcoded. In and of itself that’s neither new nor unusual.

But let’s look at what it means for a developer:

There’s no need to do a compile or build to update content. Doing a build of a big game on Unreal can take hours.We can reload the gameplay scripts on live servers without taking them down, too. A gameplay engineer can try tweaks and changes really fast. Or launch a fix for a problem as soon as it’s solved.In fact, multiple people can be working on the same servers at the same time, working live against the actual game, seeing their changes happen in real time, which means better collaboration and iteration.This gives us higher odds of “finding the fun” in a system.Less obvious is the ability to A/B test. This is traditionally very hard to do with game systems in an MMO (though mobile games have done it a lot). The benefits in terms of balancing and improving a game are pretty dramatic. A system like this is built out of tons of small bits of code. If one of them has a bug, only that code stops working. The rest of the game keeps running. It’s way more fault-tolerant, which means fewer crashes and fewer completely broken systems.The point is to set designer creativity free by removing the shackles of traditional tedious, trudging iteration.

Another exampleEverything you see and hear in our game comes down from the cloud on the fly only when you need it. These days, gamers are so used to giant install sizes that the benefits of this change aren’t immediately apparent:

We don’t need to patch your install to add things to the game; we only need to do patches to update the client. Imagine patching your browser every time Amazon added an item to its store! Seems ridiculous, right? That’s where games are today.New art can come out constantly, not just in big lumps.In fact, that art might be procedural, customizable, or modifiable in ways that aren’t possible when it’s baked into your client. This can make crafting or building much cooler.And of course, these days install sizes are enormous. With art coming down on the fly, we can also delete it from your hard drive if you haven’t seen it in a while. That means your install won’t eat all your storage! I don’t know about you, but I am really tired of having to delete games I still play to make room for new ones.Even all that only scratches the surface, though.

Once upon a time, we used to be able to maintain special ruleset shards easily. Now, it’s much harder. The days of having parallel worlds with different rulesets or even different appearances can come back. (Anyone remember Siege Perilous on Ultima Online?)

We could magically replace every pine tree with a decorated tree during the holidays, and put them back after, seamlessly.

We could create “pocket” worlds for arenas, minigames, or unique experiences. Or offer much better support for player organized events like concerts, sporting tournaments or beauty pageants.

Once upon a time on text worlds, it was common to play minigames like “recall tag.” It was a sort of “last man standing” battle game. You just teleported to the arena – which looked nothing like the game it was set in – and back out when you were eliminated. In text, that was easy. With this set up, it’s easy again.

But the fact that everything is server-driven, dynamic, and streaming has one big benefit above all.

The world doesn’t have to be an unchanging cardboard stage set.

Dynamic things can change. Players can affect them. Leave their mark on the world.

Streaming down everything on the fly means the world doesn’t have to be static. It can be simulated. It can evolve on its own. It can respond to player action.

Our game is built on that idea, and it opens up huge amounts of gameplay. But I don’t want to dive too deep into that until we announce the game.

Looking towards the futureEverything I’ve talked about helps us as developers make a better game for you, the player.

We can make more things faster, which helps us make things more fun.The game can change on the fly, at any time.This allows the most alive game world ever seen.This lets players affect it in real ways.It enables a wider array of gameplay within one online world.Without all the hassle of patches and lack of disk space when things change.That’s just the stuff that this platform gives us for the game we’re making now. But there are future benefits that it could unlock as well.

Since assets stream, we could allow assets to be uploaded by players.Because worlds stream and editing is live, we could allow players to edit worlds.The script is in a widely used language, so we could allow players to script someday.It is all architected as a network of worlds, which means we can segment that stuff off so it doesn’t break the main game, or cause the sorts of “TTP” issues (Google it) that so many games have seen.Are we doing any of that right now? No. We are making a game with this tech for you, rather than asking you to make games for us.

Why? Because that’s a lot to ask! Most people aren’t expert MMO designers, or ready to start building one from scratch!

We have a very specific plan:

Build tech that supports the future: all the stuff we’ve outlined so far. It makes making MMOs easier, cheaper, faster; and the resulting games are more varied and can offer things that current MMOs can’t.Build a game on it. Prove that it does what we think it does. Later on, once the game works and is out, we figure out what else we do. This platform would allow user modding, for example. Or outright user-created content. Or networks of multiple games, not all made by us.But there’s no point in paying much attention to that until you make a great game. All of this only matters if players are happy. So that’s what we’re working on first. A great player experience is the point.

— crossposted from the Playable Worlds website

September 9, 2021

Revealing Playable Worlds technology

Last week, I talked about “metaverse,” the hype around it, and how much of what people dream about is actually stuff online worlds have done for many years now. I ended the article on a bit of a tease, promising that I would talk about what we are doing.

I won’t tease this time.

We have built a metaverse platform.

Wait, did you say “have built?” Past tense?Oh, it’s not done. We’re probably going to be working on this for years. But I say “built” because, well, we have the basics of this stuff working.

We have a working massively multiplayer server.

Further, it’s a true persistent state world, where everything you do is saved. Worlds change, evolve, and develop based on player actions (or AI or simulation, for that matter). It’s running on the cloud right now.

But it’s not just a server. It’s a network of servers. Whole MMO worlds can bubble up and go away on the fly based on player demand. It’s a heck of a lot more efficient than something like a headless Unreal server.

And you’ll be able to hop between worlds without needing to switch clients. It permits a single, shardless, ever-expanding, ever-changing online universe.

We’ve already got it working with full server-side game logic. Meaning – each world can have completely different gameplay, without needing to change code or take the server down for updates. We’ll even be able to map your controls from the cloud, because when we say different gameplay, we mean it.

This unlocks things that AAA games haven’t been able to do before, like A/B testing. It means that someday, we can let users write their own code for those servers, and they could earn money from their creations.

When you visit different worlds, or even different parts of worlds, everything comes down on the fly to a thin client. We don’t need to patch to add new content. Every world can look completely different – one might be ours, one might be a 3rd party creator, or a branded world, or built by users. For that matter, it won’t eat your hard drive: assets go in a cache, and the cache throws away old stuff you don’t need.

That client might be on any device: phone, console, PC. Because as far as we are concerned, a device is just a window into other worlds. What device you use should not matter.

Basically, we’ve taken our decades of experience and built the platform that online worlds and their players need for the future. It’s scalable, cloud-based, enables full cross-play, and works in a way that is transparent to the people who matter: players. They get an app or game, they log in and they go where they want. And that’s it.

In other words, it makes AAA virtual spaces as straightforward as the Web. In fact, it’s meant to interoperate with the Web. We leverage lots of web technologies in our architecture. Because online worlds can’t stay in silos forever.

So… now what?Now we are building a game on top of it. We’re reasonably far along on building it, actually. For most of you, that game is what you’ll see and experience.

As we’ve said in previous posts and interviews: We are building a modern sandbox MMO. A game that fulfills the dream of living worlds that we’ve all had for a couple of decades now. It’s just built atop a modern, re-usable, scalable platform. A platform that lets us make a game no one else can make.

But our metaverse platform is plumbing. Important plumbing, but still plumbing. It just happens to be plumbing that very few people on Earth know how to build. (It helps to have built a platform with all the above characteristics before.)

If it weren’t for that plumbing, we couldn’t build the next generation of online worlds. Current engines just can’t do it.

But… we build technology for people. What matters is the way people use the tech.

And if you have dreams of a Ready Player One virtual park full of varied experiences — like so many do — well, it’s pretty important to be able to deliver one world first. Every park needs a first “land,” after all.

Look: saying you are building The Metaverse( ) is silly — that’s a project for many people over many years, and any one company that promises it anytime soon is probably biting off more than they can chew.

) is silly — that’s a project for many people over many years, and any one company that promises it anytime soon is probably biting off more than they can chew.

That’s why we decided not to talk about our platform until it was already working. There’s enough hype out there already. Most of you shouldn’t care! Most of you want a fresh experience, not a whitepaper about plumbing.

(Of course, if you happen to be someone who does care about plumbing, well, drop us a line. We do think what we have built is pretty exciting).

It’s all good to talk about metaverse dreams. But we’re practical people here at Playable Worlds. We’re not in this for virtual goods speculation. We’re not in this for acronyms.

We are here to deliver experiences that have not been possible before. Experiences that are honestly kind of overdue.

Technology is about people. And people have been waiting a long time for the dreams of online worlds to start coming true. This tech is just an (amazing, unique, and powerful) enabler.

Your dreams are the goal.

September 2, 2021

Online world or metaverse?

A lot of people are talking about the “metaverse”, and as a result, a lot of folks are wondering what the heck that word even means.

Frankly, it’s a reasonable question. But as someone who has actually built, launched, and operated a metaverse before, I have answers!

I recently spoke at the Digital Economy Forum, hosted in Korea by the Ministry of Economy and Finance, and organized by the Korea Startup Forum. After the panel, we got the question “what’s the difference between Second Life and a metaverse?”

Here’s the short-form answer:

Online worlds lead to multiverses which lead to metaverses. And just about no one has actual metaverses to offer right now.

Second Life is not a metaverse; after all, it’s just one world. A social online world oriented around creativity.

Online worlds have been around since 1978. They started out being text-only, and only for games. But around 1985, online worlds that were just for socializing and chatting came along, and in 1989 worlds meant for creativity were invented. These three kinds of worlds have been the three major types ever since.

Social worlds are used for classrooms, lectures, events, or just hanging out. Sometimes people play roleplaying games in them, but they usually don’t have game systems.Creative worlds (like Second Life) also have many of these qualities, but they are designed to allow users to create content within them, which regular social worlds don’t usually allow.Game worlds are what developed into MMORPGs: they feature game systems and combat and the like.It’s pretty easy to confuse a social world or a creative world with a metaverse. After all, they often have concerts (with live audio — sorry, Fortnite), classrooms, and lots of user-generated content. But really, the lines between all three types are blurry.

I myself worked on a game world called LegendMUD back in 1994 that had multiple games within it, including sporting events, a regular lecture series, live storytelling, and other activities. But it was still very clearly a game world where you mostly spent your time slaying monsters, and these other things to do were “extras.”

The next step up from this would be a multiverse. Pretty much all graphical online worlds have a single visual theme, you see. Merely hopping between shards of the same game? That’s just load balancing your playerbase, not building a multiverse.

In a real multiverse, there are multiple different worlds connected in a network, which do not have a shared theme or ruleset. This lets you hop between very different worlds, with completely different types of experiences.

This is the vision of the movie (and book) Ready Player One. Many connected virtual environments, running on common enough technology that you can hop between them. Roblox is a very good example of this sort of multiverse today, but it’s not a new idea, even though very few people have actually made something like it — people were talking about “interMUD protocols” and even got them working, clear back in the 90’s.

The dream of the future is a metaverse. A metaverse is a multiverse which interoperates more with the real world. In most conceptions, it includes significant elements of augmented reality – such as walking around a real city and seeing virtual things. It includes shopping at actual stores via VR interfaces. If you attend classes, it might be a class that has mixed attendance between virtual attendees and physical ones. You might perform a job solely in virtual space, and get paid real money. It blends the real and the virtual.

It can still include worlds that are games, and worlds that are social, and worlds that are creative. But it also includes worlds that are digital copies of the real world (called “mirror worlds”), including stuff that doesn’t even look like worlds. After all, when you use Maps, your car is an avatar logged into an online world of real roads, and when you check Yelp, you’re actually reading tags on a virtual version of a restaurant.

In 2006, my team and I built a metaverse called Metaplace. Before it went away, it was a network of over 70,000 worlds. Users could make their own worlds — and I mean, make them from the ground up, code and art — and we developers also made dozens of them.

Some of them were puzzle games and some of them were RPGs. Some were platformers and some were battle arenas. But some were also shops connected to real world stores. Or concert halls, or classrooms, or even art projects. You, as the user, had a common identity across all of them, but you could look different in every world.

Metaplace could perform Shakespeare plays from XML files on random websites, it could display a walkable version of an Amazon storefront, it could source data from Google Maps or talk to Google Translate on the fly, host live concerts, and much more. Basically, it could do anything the web does, and put it in a virtual space.

Oh, we didn’t tick every box you might want today; it rendered in 2d, since there were no VR headsets back then, and cloud AR was a pipedream… and we sold the company to Disney before we got around to letting our users play to earn a living from their virtual work. But it was a true metaverse. (And I do miss it, and no, there’s literally nothing else like it on earth right now).

Most metaverse technology is still speculative. To get to today’s common dream of a metaverse, there are many interoperability questions to be answered, big questions about standards, digital object ownership, and more.

That said, we shouldn’t forget

you can walk around a real city and see virtual things in Pokemon GOyou could shop at a real store via a virtual interface in Metaplace a dozen years agocountless students are attending real classes virtually via video chat todayworlds like Second Life can and do interoperate with the Web in a bunch of waysand people have been making a living selling game gold since 1998.In other words, a lot of those things that people dream of happening in the metaverse have happened in online worlds, because online world technology is the backbone of a metaverse.

That’s why I am skeptical whenever I hear someone say they are building a metaverse if they haven’t built and operated at least one online world before. After all, building just one online world is famously difficult — take it from someone who has spent a quarter of a century doing it several times over!

So no, despite what many may think, “metaverse” is not just a buzzword. It is different from an online world. But metaverses presume multiverses, and multiverses are built from online worlds. They are all in the same family.

What does this have to do with Playable Worlds? Well, the answer is pretty simple, given what I’ve said, and you’ve probably connected the dots already…even so, I think I’ll answer it next week.

But… uh… the name of the company is a hint.

—crossposted from the Playable Worlds website… head over there to check out more blog posts on what we’re doing