Raph Koster's Blog, page 5

May 31, 2018

New book POSTMORTEMS

My new book Postmortems is now available at various booksellers. The print edition ships on the 26th. Various sites may have the ebook already, some may not just yet.

My new book Postmortems is now available at various booksellers. The print edition ships on the 26th. Various sites may have the ebook already, some may not just yet.

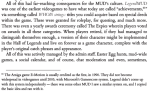

This is the first volume of a projected three that gather together many of the essays and writings that I have been sharing on this blog over the last several decades. This book focuses specifically on games I have worked on, from LegendMUD up through social games, and is a book of design history, lessons learned, and anecdotes. Richard Garriott was kind enough to write a foreword for the book.

It’s not a memoir or tell-all; the focus is on game design and game history. There’s still nowhere near enough material out there in print covering things like the history and evolution of online worlds (MUDs especially), in-depth dives into decisions made in games by the people who made them, and detailed breakdowns of how they worked. So I hope that this will be useful to scholars and designers, and that players might find it a fascinating glimpse behind the scenes. Just don’t expect salacious stories and secrets.

Those of you who have been reading the blog for a while will find much in there that is familiar; if you have ever wanted the SWG postmortem series in book form, here it is in expanded form. If you have ever wished that the various articles on the UO design were gathered together, here they are, along with new chapters covering things like all the things we tried doing to curb excessive playerkilling. If you ever wondered what happened with Metaplace, this is how you find out, as there’s a new and extensive postmortem. Many blog commenters make cameos in footnotes.

The contents:

Early Days, which covers my apprenticeship creating board games as a kid, and the lessons I learned that way.

MUDs, which has design articles about DikuMUDs, design and administrative practices material on LegendMUD , a lengthy article on the struggles with MUD governance that we went through back then, and even samples from what MUDding was like (for the younger folks out there!).

Ultima Online, including the resource system, playerkilling, the evolution of the game economy model, “A Story About a Tree” and the aftermath, and more.

Star Wars Galaxies, including the whole postmortem series, a new overall design overview, and even materials I wrote to the players explaining our design philosophy. Oh, and of course, a new piece on the NGE.

Transitions, a section on the way in which MMOs changed and the impact they left on players over the course of the 2000s.

Andean Bird, the little art game I made back in the mid-2000s, with design diary and a transcript of the popular “Influences” speech that resulted.

Metaplace, which hopefully answers the lingering question “what was it?” once and for all, and covers not only the tech architecture but also has a frank postmortem of why it didn’t work. I also go into the social games we made afterwards, with some special love for My Vineyard.

I’m sharing snippets from the text on Twitter all month. Here’s some of the samples so far:

I could use your help. Please make noise about the book online. Once you read it, please leave a review on Amazon (or wherever you buy it) — book featuring is dependent on there being a certain number of reviews there. Talk about the book on social media sites and let interested folks know it exists. I took time off from actually earning a living in order to make this happen, because I think documenting this history is important.

It was also eye-opening to go back through all this history. Many of of the lessons in these older articles are more relevant than ever, honestly, as the whole world gets swallowed up into a vast virtual world. I’d love for those lessons to get shared widely.

April 30, 2018

UOForever livestream

I spent a lovely few hours on UOForever yesterday, wandering around and seeing what UO looks like for the first time in fifteen years. Much of that time was spent doing a livestream where I told tales of UO’s development, and showed off pictures out of my design sketchbook from back then, many of them things that no one has seen publicly before.

It was a real trip to wander around Trinsic and point out art of mine that is still in the game, the rippled terrain that I still remember painstankingly making, and seeing objects that still act the way I coded them two decades ago (though of course, UOForever actually reimplemented everything themselves).

Here’s the video:

March 31, 2018

GDC18 videos

The GDCVault has posted videos of sessions from this year’s GDC already! That was fast!

The GDCVault has posted videos of sessions from this year’s GDC already! That was fast!

I’ve linked videos for the three sessions of mine that were filmed (a fourth was for a private event and wasn’t; a fifth was on the Expo floor and wasn’t). You can find them each on the page with the slides:

AI Wish List: What Do Designers Want out of AI? (panel with Noah Falstein, Robin Hunicke, Richard Lemarchand, and Laralyn McWilliams, moderated by Dave Mark.

I want it all. I want to have the tools, the machine learning, the AI, the rich data environment, to be able to make a single, probably online, connected universe that we are in fact simulating down to the point of the little pink alien gophers on the thirteenth planet around that particular green sun (which was entirely procedurally generated) actually have a history and care about one another, and I want it to have all of that stuff and have all of it be alive. Specifically because I want to drop a player into that world and have them realize, as they play, that they are touching lives, messing with things that are alive, they are trampling grass that struggled to grow, “goddamnit, you’re stepping on me again,” to realize that when they build their virtual cities, when they conquer their virtual enemies that they are being colonialist about, you know — all of those things, I want them to realize that in their daily lives, they do the same thing in the real world. Because I want the AI and the machine learning and the code and the systems out there to hold a mirror back up to us as humans. I want them to use that space as practice for being better here. So give me all of it so that people can wake up and realize what they do day to day.

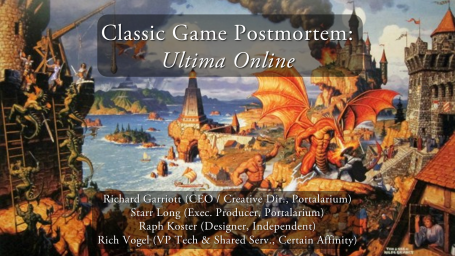

Classic Game Postmortem: Ultima Online at 20 (panel with Richard Garriott, Starr Long, and Rich Vogel).

Raph: The King was dead. Right? And I think for all of us that was the moment that we realized, right, this was no longer about control. Right? The new rulers of our virtual world, that now we all play in all the time — this was really the moment when we realized — the players were going to be the ones who topple the kings. This was the moment we realized what we had set free. You. We had set you free. And you know, no offense, but Richard was no longer the ruler of fantasy worlds. The power was now in your hands. And from the bottom of all of our hearts, I think we actually want to say “Thank you for that.” Thank you so much.

Starr: Thank you for killing Richard!

Richard: But don’t do it again!

Rules of the Game: Five Further Techniques from Rather Clever Designers. (panel with Erin Hoffman-John, Soren Johnson, Stone Librande, Richard Rouse III, Josh Sawyer)

This matters because of game longevity, which matters to me because I want my art to live for centuries, but also because it includes a bunch of stuff that drives revenue, if you like eating. It’s driven by how much space the game can have, right? And despite what we might want as creators, a lot of the power in a game experience actually comes from a loss of control. It comes from letting players have the actual authority over the experience. And so what gives that? What is it that gives that core sim? The three critical ingredients I end up looking for: first is a space that just is an interesting mathematical or structural landscape. And by this I mean, you know… a physics system meets that. Interesting relationships between objects. Like the relationships between suits and numbers and colors in a deck of cards is an interesting landscape of relationships. I look for it to be simple, with only a few rules even though it might have room for tons of data. What usually works is a way to have lots of kinds of data that work on top of the same underlying sim, and you can stack as many separate rule systems on the sim as you like. So Poker leverages the set of playing cards, but so does Blackjack and Go Fish. Pokemon leverages Pokemon types and attack types, with systems. And lastly, I look for that set of relationships, that sim, to not actually have implicit goals. I want it to be a toy. I want it to allow players to create their own goals on top of the system. It doesn’t mean then that you can’t layer goals on top of that. You can have AI with goals. It doesn’t mean the game can’t provide as many goals as you want. It means the system itself doesn’t imply them. We choose them based on the narrative or experience we want to provide. Because there is a difference between a system where all you can do is get to the other side, and a system that says “here’s cool movement physics, let’s build Portal.”

There were so many standout talks that I am hesitant to provide recommendations here for fear of forgetting a really good one. A huge amount of the videos are completely free, so I’d suggest just heading over to the GDCVault and digging in!

March 28, 2018

UO postmortem from GDC2018

I have posted up a page with the slides from the UO postmortem panel that Richard Garriott, Starr Long, Rich Vogel, and I gave at GDC 2018. We ended up doing the hour long talk, followed by an additional hour and a half (!) of Q&A afterwards. No video is available yet, but I’ll post here once it is — likely not for a few weeks.

I have posted up a page with the slides from the UO postmortem panel that Richard Garriott, Starr Long, Rich Vogel, and I gave at GDC 2018. We ended up doing the hour long talk, followed by an additional hour and a half (!) of Q&A afterwards. No video is available yet, but I’ll post here once it is — likely not for a few weeks.

One thing that the static images of the slides don’t capture is that the opening had “Stones” playing (the version from the opening screen of UO) and the chest actually animated opening when the crowd shouted that yes, we should log in.

There was a fairly large amount of coverage of the panel, much of it from outlets in Asia. I’ve provided links to the articles I’ve found so far. The most detailed, including some description of the Q&A afterwards, is the one from Massively.

VentureBeat: EA Hated Ultima Online Until It Didn’t

Rolling Stone Glixel: Ultima Online Creators Look Back on Revolutionary Game

MassivelyOP: GDC 2018: Ultima Online post-mortem with Richard Garriott, Starr Long, Raph Koster, and Rich Vogel

4Gamer (translated)

Inven (translated)

Ars Technica

Famitsu (translated)

Mein MMO (translated)

Most of the articles don’t get what we were saying about Kristen quite right — she was basically the other key designer on the team, early on; I was saying she doesn’t get enough credit for that, not that she was uncredited in the manual/game. I’ve written up the story of our job application before here on this blog, so if you want to know more, check out the article I wrote on the occasion of UO’s fifteenth anniversary. The articles also fail to mention Rick Delashmit, whom we mentioned numerous times as the key engineer on the project and who also the key programmer on LegendMUD.

The Q&A was lengthy… one bit not captured by any of the articles was the brief debate between Richard and myself about the feasibility of the virtual ecology that was intended to be in UO. He still warns people away from attempting something similar. I think it’s absolutely doable these days. I told him he had to go check out the AI Summit, and told the crowd, “Tell you what, I’ll do it in my next MMO.”

March 1, 2018

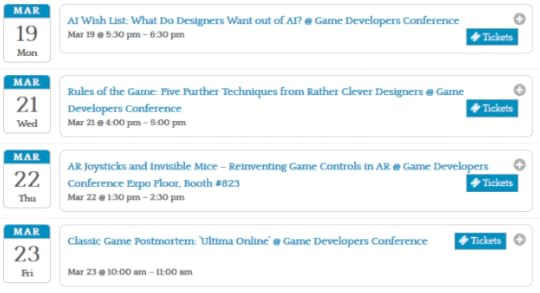

My GDC schedule

I’ve got quite a busy speaking schedule at the Game Developers Conference this year! Here’s what’s up.

I’ve got quite a busy speaking schedule at the Game Developers Conference this year! Here’s what’s up.

Monday at 5:30pm: I join a distinguished group of friends to discuss the topic of “AI Wish List: What Do Designers Want out of AI?” The other panelists are Dave Mark, Richard Lemarchand, Laralyn McWilliams, Noah Falstein, and Robin Hunicke. This should be an interesting conversation!

In 2012 and 2013, long-time game designer Warren Spector called out the discipline of AI in games as being too focused on “combat and pathfinding”, urging designers to expand into non-combat behaviors, social interactivity, and other areas. To this end, this panel brings designers from across the industry together and asks, “what is YOUR wishlist for AI?” Whether it be character AI, procedural content, animation, speech, or “director”-style pacing and content delivery, the panel won’t necessarily focus on the practical of “what can we do” but explore “what COULD we do?” The goal is to give AI programmers ideas for “what SHOULD we do?”

Wednesday at 4pm: Richard Rouse continues his annual series on “Rules of the Game,” where a panel of designers offer up one rule or design approach that has served them well in their design practice. I’ll be sharing mine alongside Erin Hoffman-John, Soren Johnson, Josh Sawyer, and Stone Librande.

How do you make your games work? There’s no sure-fire way to design great games, but over numerous successful projects the best designers develop techniques that help them craft compelling experiences. Returning for GDC 2018, the Rules of the Game session takes five renowned designers and asks them to go into detail about a rule they’ve used in their work. Each speaker has ten minutes to dive into their technique and provide detailed examples about how they have used the rule in past projects, honestly sharing the pluses and minuses including where their rule works well and where it may be less applicable. These are personal rules that you may not always agree with, but they’re guaranteed to provide interesting fodder for your own game design thoughts and help you build your own design rulebook.

Thursday at 1:30pm: I’ll be at the Google booth on the Expo Floor co-presenting with Aaron Cammarata. We (and others!) have been working together on “AR Joysticks and Invisible Mice – Reinventing Game Controls in AR“ at Google for a while. (I can finally say that out loud, because this talk listing is actually public now). Look for Aaron’s other talk during Google’s Developer Day on “Building a better multiplayer” as well.

Historically, game developers have had a library of well-understood controls available for building games: d-pads, steering wheels, mice and keyboards, pedals, shoulder buttons, and of course, analog joysticks. In the emerging world of AR, designing the UX of even basic actions like “select unit” can bring development to a screeching halt. In this talk, we’ll share with you our attempt to create AR versions of the two most common controls: mouse click and analog joystick. Starting with hypotheses, we built prototypes, and tested different options. In this deep dive talk we’ll share our findings, and show you the control schemes in finished game products!

Friday at 10am: Rich Vogel, Starr Long, and the legendary Richard Garriott (plus me, of course) will be offering up a “Classic Game Postmortem: Ultima Online” to celebrate the game’s 20th anniversary as a live service this past fall.

Kal Ort Por! The death of Lord British. Simulated ecologies. Playerkillers. The Bank of Britain. City sieges. Weddings. Sports events. Players who were orcs. Living the Virtues.

September 2017 marked the 20th anniversary of the launch on Origin’s ‘Ultima Online’, the pioneering massively multiplayer RPG that changed online gaming forever. Join key members of the team as they talk about the things that went wrong and right: Richard Garriott de Cayeux, the legendary Lord British and producer on the game; Starr Long, the original director; Rich Vogel, the producer; and Raph Koster, the creative lead.

You can always check out the full calendar here on the site for dates and times of upcoming speaking events or whatever; I try to keep it up to date.

February 10, 2018

Favorite game designs from 2017

I already posted about my favorite game of last year — What Remains of Edith Finch — but I liked a lot of other games last year too, so here are some recommendations and why I liked them.

I play well over a hundred games a year, for varying lengths of time, usually mostly right at the end of the year when I have time off and can devote it to sitting in front of a screen and playing for eight hours a day. Even the games I really enjoy, I often never get to go back to. My completion rate is terrible. Though this year, I did finish Gorogoa, Edith Finch, and Old Man’s Journey, mostly because they are short. So bear in mind that for me, “favorite” usually means “intrigued me from a design perspective” and not necessarily “had the most fun playing.” Think of this list as “games designers should play,” in my opinion.

These are just in alphabetical order, by the way, not ranked in any way.

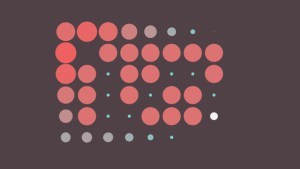

I ended up considering this one of my favorite examples of pure design this year. The game takes on the challenge of defining a system – based on mouse movements – wherein circles grow and shrink. Sometimes they get bigger when you move up and smaller when you move down. Sometimes they grow and shrink based on your mousing speed. Your goal is to mouse a cursor around to reach an exit. There is little visual language tying the behavior of obstacles to the movement of the mouse, so you must approach each puzzle as learning a new system, yet one which is internally consistent with the ones you have learned previously. The game itself is then framed in its own visual language that encompasses all elements of the UI and basic structural stuff (level exits, etc). The extreme minimalist approach may turn off some, but I see it as a tough design challenge that was met excellently, and the way in which the game gradually teaches its own framework is actually quite reminiscent of and resonant with what Gorogoa is doing, without the narrative scaffolding.

I ended up considering this one of my favorite examples of pure design this year. The game takes on the challenge of defining a system – based on mouse movements – wherein circles grow and shrink. Sometimes they get bigger when you move up and smaller when you move down. Sometimes they grow and shrink based on your mousing speed. Your goal is to mouse a cursor around to reach an exit. There is little visual language tying the behavior of obstacles to the movement of the mouse, so you must approach each puzzle as learning a new system, yet one which is internally consistent with the ones you have learned previously. The game itself is then framed in its own visual language that encompasses all elements of the UI and basic structural stuff (level exits, etc). The extreme minimalist approach may turn off some, but I see it as a tough design challenge that was met excellently, and the way in which the game gradually teaches its own framework is actually quite reminiscent of and resonant with what Gorogoa is doing, without the narrative scaffolding.

This game is subversive. Unfortunately, it takes a long time to get to the twists that make it so, and I almost gave up before getting to them. The entire first third of the game is a pretty bog standard flirty visual novel thing, that I basically was clicking through as fast as possible, bored out of my skull. Then (spoilers!) a character suicide, glitching, and the metafictional aspects kicked in, and it got a lot more interesting. I hesitate to describe it more, because it really is more powerful when you encounter the twists yourself. Suffice to say, it blows up visual novel design in interesting ways, while critiquing the form itself (and its content preoccupations).

This game is subversive. Unfortunately, it takes a long time to get to the twists that make it so, and I almost gave up before getting to them. The entire first third of the game is a pretty bog standard flirty visual novel thing, that I basically was clicking through as fast as possible, bored out of my skull. Then (spoilers!) a character suicide, glitching, and the metafictional aspects kicked in, and it got a lot more interesting. I hesitate to describe it more, because it really is more powerful when you encounter the twists yourself. Suffice to say, it blows up visual novel design in interesting ways, while critiquing the form itself (and its content preoccupations).

This is obviously a game as artistic statement, and it’s quite a powerful one. In this game, you play… everything. Embodying everything from virii to lizards to trees to continents to galaxies, you explore, and switch bodies, and you dance and sing. You can be a wedding ring or a quark or a herd of deer or superheated gas, and in doing so, feel the commonalities across everything there is. I feel like I have only scratched the surface of the total collection available, but I managed to cycle through what I think are all scales from the elemental to the cosmic. It’s mesmerizing and beautiful, and there are philosophy recordings as collectibles that add a lot. All in all, this felt like something beyond “game” to me, in that it’s not really systemically that fascinating despite its innovation; what systems are there are not intended as challenges really so much as conceptual notions that help you explore what is in the end a giant loop of connected content. This is really great game direction, hampered only by what feels like time and budget. I could quibble with the pacing at first, and the challenge of navigation once you are in 1d space, but all in all this delivers an experience that only our medium can really deliver. Don’t miss this one, it was definitely in my top five.

This is obviously a game as artistic statement, and it’s quite a powerful one. In this game, you play… everything. Embodying everything from virii to lizards to trees to continents to galaxies, you explore, and switch bodies, and you dance and sing. You can be a wedding ring or a quark or a herd of deer or superheated gas, and in doing so, feel the commonalities across everything there is. I feel like I have only scratched the surface of the total collection available, but I managed to cycle through what I think are all scales from the elemental to the cosmic. It’s mesmerizing and beautiful, and there are philosophy recordings as collectibles that add a lot. All in all, this felt like something beyond “game” to me, in that it’s not really systemically that fascinating despite its innovation; what systems are there are not intended as challenges really so much as conceptual notions that help you explore what is in the end a giant loop of connected content. This is really great game direction, hampered only by what feels like time and budget. I could quibble with the pacing at first, and the challenge of navigation once you are in 1d space, but all in all this delivers an experience that only our medium can really deliver. Don’t miss this one, it was definitely in my top five.

Here’s the thing… there’s a lot of Gang Beasts that is TERRIBLE. No controls explanations, not even good guidance on the menus. You can launch a multiplayer melee game with only you in it and be unable to really do anything. And yet… when you play this with other people it totally comes alive, with truly fresh brawl mechanics around grabbing hold, throws, climbing, and more. You play these doughy, floppy, goofy figures in an arena brawler. It’s basically a game where the awkwardness of the controls and physics themselves generate the humor. Interesting to contrast to plenty of recent fighting games, which takes themselves so so seriously and yet feel shallower (!) and to Nidhogg 2, where everything works together. Easily some of the most fun I’ve had in multiplayer recently.

Here’s the thing… there’s a lot of Gang Beasts that is TERRIBLE. No controls explanations, not even good guidance on the menus. You can launch a multiplayer melee game with only you in it and be unable to really do anything. And yet… when you play this with other people it totally comes alive, with truly fresh brawl mechanics around grabbing hold, throws, climbing, and more. You play these doughy, floppy, goofy figures in an arena brawler. It’s basically a game where the awkwardness of the controls and physics themselves generate the humor. Interesting to contrast to plenty of recent fighting games, which takes themselves so so seriously and yet feel shallower (!) and to Nidhogg 2, where everything works together. Easily some of the most fun I’ve had in multiplayer recently.

Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy

Fundamentally, a game about frustration – and therefore about games. Maybe even about Cuphead. Foddy wrings a lot out of the deliberately challenging control mechanic (a design signature of Foddy’s, see QWOP), and the level design is really carefully tuned, rather exquisite actually. As a player, it maybe means I shelve the game after a while feeling like I got the point, because, well, I suck. But there’s an active speedrun community out there accomplishing what looks like the impossible. Play this to get a sense of the way in which some players can make a cult of perfect play execution. And I can’t shake the feeling that I should go back to it and try to get better…. Not to mention, the game itself talks to you (well, Foddy does through the game) telling you it’s quite OK to give up. As a meta-commentary, that works for me rather well.

Fundamentally, a game about frustration – and therefore about games. Maybe even about Cuphead. Foddy wrings a lot out of the deliberately challenging control mechanic (a design signature of Foddy’s, see QWOP), and the level design is really carefully tuned, rather exquisite actually. As a player, it maybe means I shelve the game after a while feeling like I got the point, because, well, I suck. But there’s an active speedrun community out there accomplishing what looks like the impossible. Play this to get a sense of the way in which some players can make a cult of perfect play execution. And I can’t shake the feeling that I should go back to it and try to get better…. Not to mention, the game itself talks to you (well, Foddy does through the game) telling you it’s quite OK to give up. As a meta-commentary, that works for me rather well.

A lot of attention went towards Zelda and Mario this year, but I think I have sunk just as many hours into Golf Story. (And can I say that the Switch first year line-up is astonishingly good, perhaps the best since the Dreamcast’s fabled library?). A real charmer that was a bit of a sleeper, this game manages to execute golf just about as well as hit mobile games like Golf Clash do, but wraps it in an RPG. The RPG is engaging and solid, the pacing is great, the challenges are fun and very different from typical RPG exercises… all in all, a sleeper for me, with some fun and engaging game design. The golf is fairly standard overall, swing meters and the like, but it does have stuff like gophers that steal the ball and even advanced controls, to add some depth. Also, Zelda: Breath of the Wild should have used this inventory system.

A lot of attention went towards Zelda and Mario this year, but I think I have sunk just as many hours into Golf Story. (And can I say that the Switch first year line-up is astonishingly good, perhaps the best since the Dreamcast’s fabled library?). A real charmer that was a bit of a sleeper, this game manages to execute golf just about as well as hit mobile games like Golf Clash do, but wraps it in an RPG. The RPG is engaging and solid, the pacing is great, the challenges are fun and very different from typical RPG exercises… all in all, a sleeper for me, with some fun and engaging game design. The golf is fairly standard overall, swing meters and the like, but it does have stuff like gophers that steal the ball and even advanced controls, to add some depth. Also, Zelda: Breath of the Wild should have used this inventory system.

It’s art, in the best sense. The overall experience is mesmerizing, consistent, and gorgeous. The puzzles are clever yet proceed from inexorable logic. I give it a bit of a knock on the design side if only because it is basically a really amazing puzzle collection, and some of the puzzles end up vulnerable to the classic “obscurity” problem where you just have to try every possible combination before you notice something that you hadn’t tried in combination with something else. But it’s all in service of delivering a lovely meditation on life, mortality, and memory that resonates beautifully in connection with Edith Finch. At first I was concerned that it was overly linear as well, but around the third fruit it opened up. It reminded me of the old Mac classic The Fool’s Errand a bit. Also one of my top five for the year.

It’s art, in the best sense. The overall experience is mesmerizing, consistent, and gorgeous. The puzzles are clever yet proceed from inexorable logic. I give it a bit of a knock on the design side if only because it is basically a really amazing puzzle collection, and some of the puzzles end up vulnerable to the classic “obscurity” problem where you just have to try every possible combination before you notice something that you hadn’t tried in combination with something else. But it’s all in service of delivering a lovely meditation on life, mortality, and memory that resonates beautifully in connection with Edith Finch. At first I was concerned that it was overly linear as well, but around the third fruit it opened up. It reminded me of the old Mac classic The Fool’s Errand a bit. Also one of my top five for the year.

A sleeper for me – I didn’t play the original. We get an evocative opening, followed by a tense rush and movement tutorial, and after a moderately dull “learn the map” exploration sequence, the game unveils a really fun and weird gravity-based control scheme set in an world that draws from some of the better choices for anime inspiration. The characters are great, the art is very good. Level design is somewhat punishing, and harmed a lot by the uniform palette of colors and shapes which make “find the character” challenges and quests an exercise in annoyance. Even so, there’s a freshness here that most JRPGs simply don’t hit for me. This is one of the games out of the set that I’d be inclined to come back to, on a personal level, because I found it engaging.

A sleeper for me – I didn’t play the original. We get an evocative opening, followed by a tense rush and movement tutorial, and after a moderately dull “learn the map” exploration sequence, the game unveils a really fun and weird gravity-based control scheme set in an world that draws from some of the better choices for anime inspiration. The characters are great, the art is very good. Level design is somewhat punishing, and harmed a lot by the uniform palette of colors and shapes which make “find the character” challenges and quests an exercise in annoyance. Even so, there’s a freshness here that most JRPGs simply don’t hit for me. This is one of the games out of the set that I’d be inclined to come back to, on a personal level, because I found it engaging.

It’s interesting to contrast this to the very very different RiME. Both are fundamentally linear 3rd person adventure puzzlers. Each has a feature or two the other doesn’t (combat, herding), but at formalist heart, they aren’t that different. But they do end up different, thanks to Hellblade’s focus on unreliable narration grounded in an extremely realistic presentation — it’s a game where you feel the challenges of mental illness (voices in your head, hallucinations, and other symptoms of psychosis) whilst traversing a landscape that is exactly what we mean when we use the hackneyed phrase “a descent into madness,” full of corpses on spikes and horrific scenes. In the process, it deconstructs that phrase, grounding the environment in realism including fairly accurate depictions of the Picts and Norse. There’s even a metafictional element to the portrayal of the psychosis, with one of the voices aware that there is in fact a player playing the game. Intense and emotionally challenging, this is one to look at in order to appreciate the ways in which a narrative layer can massively reinforce and reframe mechanics, aided by stellar voice acting.

It’s interesting to contrast this to the very very different RiME. Both are fundamentally linear 3rd person adventure puzzlers. Each has a feature or two the other doesn’t (combat, herding), but at formalist heart, they aren’t that different. But they do end up different, thanks to Hellblade’s focus on unreliable narration grounded in an extremely realistic presentation — it’s a game where you feel the challenges of mental illness (voices in your head, hallucinations, and other symptoms of psychosis) whilst traversing a landscape that is exactly what we mean when we use the hackneyed phrase “a descent into madness,” full of corpses on spikes and horrific scenes. In the process, it deconstructs that phrase, grounding the environment in realism including fairly accurate depictions of the Picts and Norse. There’s even a metafictional element to the portrayal of the psychosis, with one of the voices aware that there is in fact a player playing the game. Intense and emotionally challenging, this is one to look at in order to appreciate the ways in which a narrative layer can massively reinforce and reframe mechanics, aided by stellar voice acting.

Unquestionably a standout for the year. Rich gameplay mechanics, and a stellar job of unveiling an open world environment that rivals the best I’ve seen from more established series like Tomb Raider. A very interesting IP as well, with appealing characters. Basically, if game direction is about everything working together, this is one of the best I’ve seen in a while. It gets boosted by its freshness – a new world, interesting and fresh stealth mechanics, diverse weapon types with new effects, etc. It’s not as experimental as most of the titles on this list — it, like Uncharted: Lost Legacy and Super Mario Odyssey, are basically “just” triumphs of development execution against mostly familiar game design challenges. But we shouldn’t minimize what an achievement that is, when it’s pulled off as well as it is here.

Unquestionably a standout for the year. Rich gameplay mechanics, and a stellar job of unveiling an open world environment that rivals the best I’ve seen from more established series like Tomb Raider. A very interesting IP as well, with appealing characters. Basically, if game direction is about everything working together, this is one of the best I’ve seen in a while. It gets boosted by its freshness – a new world, interesting and fresh stealth mechanics, diverse weapon types with new effects, etc. It’s not as experimental as most of the titles on this list — it, like Uncharted: Lost Legacy and Super Mario Odyssey, are basically “just” triumphs of development execution against mostly familiar game design challenges. But we shouldn’t minimize what an achievement that is, when it’s pulled off as well as it is here.

This game rocks. The pixel art is gorgeous. The controls are tuned to precision. The weapons mechanics are deep and diverse, with a rock-paper-scissors depth that is really elegant (I love the rapier, but boy, it is harder to block thrown weapons or bow shots with it!). The territory mechanic combined with the level structure (doors, platforms, varying height, traps, etc) and weapon variety reward multiple play strategies, from aggressive to extremely careful ranged play. Just really great design here that clicks intuitively. I suspect it has to be played multiplayer to really be appreciated. Out of the various head to head fighting games this year, this was easily the best.

This game rocks. The pixel art is gorgeous. The controls are tuned to precision. The weapons mechanics are deep and diverse, with a rock-paper-scissors depth that is really elegant (I love the rapier, but boy, it is harder to block thrown weapons or bow shots with it!). The territory mechanic combined with the level structure (doors, platforms, varying height, traps, etc) and weapon variety reward multiple play strategies, from aggressive to extremely careful ranged play. Just really great design here that clicks intuitively. I suspect it has to be played multiplayer to really be appreciated. Out of the various head to head fighting games this year, this was easily the best.

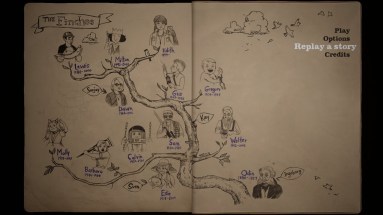

Sometimes, as with Doki Doki Literature Club or this title, there’s a reluctance to hop on the bandwagon of Tumblr popularity. Don’t let that stop you from trying out Night in the Woods. A blend of platformer, rhythm game (!), and straight-up narrative adventure game, Night in the Woods succeeds on the strength of its writing, which evokes a very specific small town and a host of fascinating characters, with humor and affection, and a keen cognizance of their personality flaws. The execution is excellent all the way down the care taken with chat bubbles; it says something when your top complaint about a title’s polish is that too many unmissable jokes are hidden behind having to talk to every character three times (it gets a tad tedious). The IP design is an object lesson in appeal to a modern younger audience: a broad cast of characters in which almost anyone can find someone to identify with, practically designed to be doodled in fan art. This is an area that more developers need to pay attention to, as that sort of emotional connection to characters is going to vital for standing out in crowded markets. NitW nails that gushing “Oh, I love her” affectionate reaction from a cosplayer in a way that few titles do.

Sometimes, as with Doki Doki Literature Club or this title, there’s a reluctance to hop on the bandwagon of Tumblr popularity. Don’t let that stop you from trying out Night in the Woods. A blend of platformer, rhythm game (!), and straight-up narrative adventure game, Night in the Woods succeeds on the strength of its writing, which evokes a very specific small town and a host of fascinating characters, with humor and affection, and a keen cognizance of their personality flaws. The execution is excellent all the way down the care taken with chat bubbles; it says something when your top complaint about a title’s polish is that too many unmissable jokes are hidden behind having to talk to every character three times (it gets a tad tedious). The IP design is an object lesson in appeal to a modern younger audience: a broad cast of characters in which almost anyone can find someone to identify with, practically designed to be doodled in fan art. This is an area that more developers need to pay attention to, as that sort of emotional connection to characters is going to vital for standing out in crowded markets. NitW nails that gushing “Oh, I love her” affectionate reaction from a cosplayer in a way that few titles do.

Another commonality across games this year was meditations on loss and mortality. Old Man’s Journey is a poetic game, heavily reliant on quiet mood-setting and stunningly beautiful visuals, that also offers up some relatively lightweight but interesting puzzle play. Taken in the abstract, the puzzle could easily have been done in a manner akin to Circles (only with lines and arcs), and would likely have lost its charm pretty quickly. As a designer whose puzzle designs often lean abstract, this was an object lesson in how to infuse dry mechanics with rich emotional content.

Another commonality across games this year was meditations on loss and mortality. Old Man’s Journey is a poetic game, heavily reliant on quiet mood-setting and stunningly beautiful visuals, that also offers up some relatively lightweight but interesting puzzle play. Taken in the abstract, the puzzle could easily have been done in a manner akin to Circles (only with lines and arcs), and would likely have lost its charm pretty quickly. As a designer whose puzzle designs often lean abstract, this was an object lesson in how to infuse dry mechanics with rich emotional content.

Here’s the thing – I haven’t enjoyed a lot of the more recent Mario titles, but this one is just a) super inviting b) full of side tasks and puzzles and quests, and c) so varied thanks to the possession mechanic. It deserves the accolades it is getting. Zelda: Breath of the Wild edges it out for me in both design and overall experience, thanks to the variety in play – fundamentally, this is still mostly jumping puzzles and simple attacks, with no real resource management. And Zelda just attempts a tougher challenge in terms of the UX, given Mario’s stronger linearity. But this is simply state of the art anyway, for what it is doing. The co-op play is a great addition, and it’s probably the best secrets/collection system in a Mario game in years.

Here’s the thing – I haven’t enjoyed a lot of the more recent Mario titles, but this one is just a) super inviting b) full of side tasks and puzzles and quests, and c) so varied thanks to the possession mechanic. It deserves the accolades it is getting. Zelda: Breath of the Wild edges it out for me in both design and overall experience, thanks to the variety in play – fundamentally, this is still mostly jumping puzzles and simple attacks, with no real resource management. And Zelda just attempts a tougher challenge in terms of the UX, given Mario’s stronger linearity. But this is simply state of the art anyway, for what it is doing. The co-op play is a great addition, and it’s probably the best secrets/collection system in a Mario game in years.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild

An open world that is highly explorable yet you never feel truly lost. Deep deep systems at a simulation level, from AI to even basic movement. Such simple and elegant little touches that add such depth, like the fatigue management and the sound meter. Cooking things. The clothing. Somehow this is managing to pack in more depth into its systems than many an open world game with ammo and guns and set pieces and the like, and yet it is so clean, so straightforward. I might quibble about the slight clunkiness in the interfaces for inventory and the like (they could have taken a tip or two from Golf Story, actually!) but compared to the core gameplay, it’s really a minor quibble. Most importantly, this shows a path forward for AAA games, away from raw content generation and towards simulation, in a way that isn’t dry and numbers-heavy or hopelessly obscure and invisible to players.

An open world that is highly explorable yet you never feel truly lost. Deep deep systems at a simulation level, from AI to even basic movement. Such simple and elegant little touches that add such depth, like the fatigue management and the sound meter. Cooking things. The clothing. Somehow this is managing to pack in more depth into its systems than many an open world game with ammo and guns and set pieces and the like, and yet it is so clean, so straightforward. I might quibble about the slight clunkiness in the interfaces for inventory and the like (they could have taken a tip or two from Golf Story, actually!) but compared to the core gameplay, it’s really a minor quibble. Most importantly, this shows a path forward for AAA games, away from raw content generation and towards simulation, in a way that isn’t dry and numbers-heavy or hopelessly obscure and invisible to players.

Just about flawless. Stunning visuals, near-perfect guidance, great writing. Oh, there are weaknesses: gameplay was by and large the same stuff we’ve seen for quite some time, new systems were thin on the ground, and when compared to the emergent characteristics of a game like Zelda, it starts to suffer. The banter and characterization were excellent, but somehow the stick figures in West of Loathing were occasionally more emotionally affecting. And yet… when you first see the bazaar in the opening city, you get a sense for how far AAA has come in presenting immersive locales, and start to see a future in which high-end games have less bang-bang and more quiet moments that are still strong storytelling. Those quieter moments have always been the strength of the Uncharted series, more so than the puzzling or platforming, and definitely more so than the combat sequences. It’s still rarely done, and just about never as well as it’s done here. In some design circles there may be disdain for the sort of craftsmanship that goes into this sort of experiential achievement, but there shouldn’t be.

Just about flawless. Stunning visuals, near-perfect guidance, great writing. Oh, there are weaknesses: gameplay was by and large the same stuff we’ve seen for quite some time, new systems were thin on the ground, and when compared to the emergent characteristics of a game like Zelda, it starts to suffer. The banter and characterization were excellent, but somehow the stick figures in West of Loathing were occasionally more emotionally affecting. And yet… when you first see the bazaar in the opening city, you get a sense for how far AAA has come in presenting immersive locales, and start to see a future in which high-end games have less bang-bang and more quiet moments that are still strong storytelling. Those quieter moments have always been the strength of the Uncharted series, more so than the puzzling or platforming, and definitely more so than the combat sequences. It’s still rarely done, and just about never as well as it’s done here. In some design circles there may be disdain for the sort of craftsmanship that goes into this sort of experiential achievement, but there shouldn’t be.

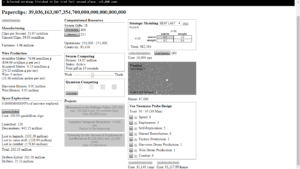

If I had stuck disclaimers all through this list, I’d probably have to label at least half the games as having been worked on by people I know. This one is no exception, as it was made by my friend Frank Lantz. It’s an idle game where you make paperclips instead of cookies. It’s also a parable about AI taking over the universe. The unlocks and balancing act here are a lot more intricate than most idle games, and the subversive narrative commentary is nicely done. Pretty innovative clicker gameplay starts to show up, and for the genre it is pretty cutting edge design. But for an experience, it’s of course lacking, with the mobile version presenting much like the web version did previously. I look forward to Frank getting ripped off like other text-based idle games were, and fresh versions of his many innovative design elements in here showing up in far slicker formats. However, it’s unlikely more commercial endeavors will serve up quite the same wit and philosophical depth.

If I had stuck disclaimers all through this list, I’d probably have to label at least half the games as having been worked on by people I know. This one is no exception, as it was made by my friend Frank Lantz. It’s an idle game where you make paperclips instead of cookies. It’s also a parable about AI taking over the universe. The unlocks and balancing act here are a lot more intricate than most idle games, and the subversive narrative commentary is nicely done. Pretty innovative clicker gameplay starts to show up, and for the genre it is pretty cutting edge design. But for an experience, it’s of course lacking, with the mobile version presenting much like the web version did previously. I look forward to Frank getting ripped off like other text-based idle games were, and fresh versions of his many innovative design elements in here showing up in far slicker formats. However, it’s unlikely more commercial endeavors will serve up quite the same wit and philosophical depth.

The game proceeds as basically a set of familiar errands and quests, with basic branching, closed off doors, etc. But it also has one of the clearest and strongest visions of anything this year, and total commitment to it. From the throwaway “colorblind mode” gag in the options menu, to the job collecting manure, to the silly walks Easter egg, to the way in which you can dramatically affect the course of the game through your choice of horse, mine level, or companion, it revels in its goofy world while still managing somehow to capture the pathos of the better Westerns. The storyline for the rancher is genuinely emotionally affecting, as is the doctor later into the game. A really pleasant surprise overall – in many ways as big a feast of coherent worldbuilding and storytelling as Mario Odyssey.

The game proceeds as basically a set of familiar errands and quests, with basic branching, closed off doors, etc. But it also has one of the clearest and strongest visions of anything this year, and total commitment to it. From the throwaway “colorblind mode” gag in the options menu, to the job collecting manure, to the silly walks Easter egg, to the way in which you can dramatically affect the course of the game through your choice of horse, mine level, or companion, it revels in its goofy world while still managing somehow to capture the pathos of the better Westerns. The storyline for the rancher is genuinely emotionally affecting, as is the doctor later into the game. A really pleasant surprise overall – in many ways as big a feast of coherent worldbuilding and storytelling as Mario Odyssey.

On stuff that isn’t on this list

There were a lot of other really good games that I’m not mentioning here, obviously. In some cases, I just didn’t like them, and I’m not going to spend my time bashing other developers’ hard work when instead I can put my effort towards calling attention to cool stuff instead. In other cases, there were specific features that are worth checking out but they just didn’t fit on the list above.

So, in no particular order, I’d also suggest designers check out:

Aaero, for applying melody into a rhythm game.

Cat Quest, for applying mobile game accessibility lessons to a PC RPG.

Cinco Paus, because it’s Michael Brough’s new game.

Cuphead, for beautiful game direction and visual design.

Death Coming, for creating an “active hidden object” game with quirky humor.

For Honor, tackling the challenge of melee combat.

Golf Clash, probably the current pinnacle of expert mobile game design.

Hollow Knight, a tremendously evocative Metroidvania game.

Knowledge is Power, part of a series of experiments on PSN in using mobile phones as control devices for hidden information in console games.

From the same series, Hidden Agenda explores ways to use that hidden info in the service of group narrative choice. I didn’t think it was hugely successful, but it was trying to break new ground.

A lot of people really like Nioh. I found it too grimdark to personally enjoy, but can’t deny the depth in the combat.

Persona 5, mostly for methods of storytelling, such as scene cuts between characters, uses of camera angles, and the like.

RiME, a peaceful puzzle explorer with gorgeous visuals.

Space Pirate Trainer, which offered a mix of genres in an expansive feeling world.

SteamWorld Dig 2, another stellar Switch title with really strong experience design.

The Sexy Brutale, which plays with time and rewinds in a fresh way.

Tooth and Tail, for a fresh take on the RTS.

Walden, for a view into ways in which literary adaptations and non-fiction experiences can be created using the games medium.

Big trends

Metafiction

Stories about loss and mortality

Insanely high levels of polish

Slick accessibility paths strongly inspired by mobile games

Completely opaque difficulty curves inspired by Dark Souls and seen as a virtue (for the record, I don’t see this as a virtue personally)

Anyway, now you have something to do for the rest of the weekend. Have fun!

February 6, 2018

Why I loved “Edith Finch”

I was chatting on Twitter with someone about narrative games, and What Remains of Edith Finch came up. It was my favorite game of last year, and I had written this little bit on it for a forum discussion elsewhere… but never posted it here. So here it is, slightly expanded.

I was chatting on Twitter with someone about narrative games, and What Remains of Edith Finch came up. It was my favorite game of last year, and I had written this little bit on it for a forum discussion elsewhere… but never posted it here. So here it is, slightly expanded.

I’ll try to do this without spoilers. TLDR: Basically, an amazing gamut of emotional stuff gets evoked by linking mini-games (mostly about control, which is crucial to the underlying themes of the story) to the stories really tightly.

Long form:

Edith Finch is a major structural evolution of what people have termed “walking simulators,” first person narrative storytelling, a hybridization of filmic story with narrative drips from static object interactions.

Gone Home (which I liked a lot) was basically “click on things, get story bit, move on.” The game consisted in finding all the story bits in a zone before moving to the next zone, and in assembling the bits in your head to form a coherent picture. In that sense, it was not very structurally sophisticated — it told an interesting story, but mechanically, it was basically the environmental storytelling mechanic over and over, with some minor key lock stuff in between. I hasten to add that this isn’t a negative–as designers, we should select mechanics based on whether they serve our goals, not because they are complex and cool.

Later narrative games ranging from That Dragon, Cancer to The Novelist have added more forms of mechanical interaction with the story. TDC is probably the most obvious direct antecedent to Edith Finch; sequences in TDC involved moving in particular directions, or doing specific actions, that lined up to the story.

For example, in TDC there is a moment where the story is about not being able to continue struggling, and needing to embrace the fact that terminal illness is going to win. The game has been presenting you with a challenge to swim to a surface, and the “correct answer” in terms of play action is to choose to drown. It’s a powerful moment of tightly coupling narrative and basic gameplay mechanics — what might get called ludonarrative consonance rather than dissonance.

For example, in TDC there is a moment where the story is about not being able to continue struggling, and needing to embrace the fact that terminal illness is going to win. The game has been presenting you with a challenge to swim to a surface, and the “correct answer” in terms of play action is to choose to drown. It’s a powerful moment of tightly coupling narrative and basic gameplay mechanics — what might get called ludonarrative consonance rather than dissonance.

It’s also, as I have mentioned was common in the large wave of art games over the last decade, a sort of denying gameness, structurally speaking. Like many other art games, it uses futility — failing, “not actually playing,” surrender — as the way to make its point. Edith Finch does the opposite.

Edith Finch is basically a linked short story collection. The player moves through gradual narrative discovery learning about the family history of the character they are playing. The action takes place entirely inside and in the immediate grounds of a magical-realist house on the shore somewhere in the Pacific northwest.

The actual exploration involves some basic puzzle solving, adventure game style, with hidden doors and the like. This is obviously not new in games, but it immediately frames the game as not confining itself solely to environmental storytelling. The game also uses location-based audio cues linked to progress to narrate. So basically, it makes use of all the techniques that you saw in games like Ethan Carter or Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture.

The actual exploration involves some basic puzzle solving, adventure game style, with hidden doors and the like. This is obviously not new in games, but it immediately frames the game as not confining itself solely to environmental storytelling. The game also uses location-based audio cues linked to progress to narrate. So basically, it makes use of all the techniques that you saw in games like Ethan Carter or Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture.

And then it hugely ups the ante. As you learn about individual characters who have lived in the house in the past, you start to inhabit their experiences. You take control of their body, in flashbacks, and experience what they went through — actually, it’s better put as you cause what they went through. In many cases, the rendering changes radically and with it the style of gameplay.

Some of these characters engage in just small minigames that get across what they do — a kid on a swing, a hermit repeatedly opening a tin. Others offer actual gameplay, such as a brief horror survival sequence narrated in comic book form, or a fun experimental control game where you play a tentacled monster, or a sequence with playing with toys in a bathtub that may make you cry (it’s a case where you the player are complicit in something terrible, but the mechanics make you want to do it, and even celebrate you doing it)

Some of these characters engage in just small minigames that get across what they do — a kid on a swing, a hermit repeatedly opening a tin. Others offer actual gameplay, such as a brief horror survival sequence narrated in comic book form, or a fun experimental control game where you play a tentacled monster, or a sequence with playing with toys in a bathtub that may make you cry (it’s a case where you the player are complicit in something terrible, but the mechanics make you want to do it, and even celebrate you doing it)

The near culmination of it all is a moment where you literally control a real world activity with one thumbstick and a videogame-in-the-game with the other, and both are rendered at the same time, with one taking over the other, and gradually the repetitive real world play turns out to matter to the trickier-to-drive game-in-game.

The near culmination of it all is a moment where you literally control a real world activity with one thumbstick and a videogame-in-the-game with the other, and both are rendered at the same time, with one taking over the other, and gradually the repetitive real world play turns out to matter to the trickier-to-drive game-in-game.

This is different from the sort of “subverting gameyness” that earlier works did. Rather than progress (or hit the “point of the game”) by hitting a wall in the game’s structure, Edith Finch actually sets up progression in a very traditional way, by having you engage in specific types of active complicity. But it manages to do it in service of the same sorts of themes as the earlier games. I find this important, because in some ways, the earlier games, taken as a whole, were starting to feel a bit one-note in a way because they used such similar techniques. Edith Finch to me opens up a whole new array of tools.

Basically, it plays with “mechanics that make you feel things” really effectively. And it’s a tour de force in doing so, because sometimes it does it for schlocky horror, others for sadness, others for humor, others for modeling suicidal depression.

Why is this exciting? Games and story historically coexist in troubled fashion. Embedded mini-games typically serve as just “ways to turn the page” — stuff like a lock picking game in an Uncharted game or something is just a little mini-game and carries basically no emotional impact. Stories may be well written and acted — and Edith Finch is both, obviously — but often you are passively observing during the emotionally powerful moments. In Edith Finch, we have the single best example of marrying story and game basically ever — and not once, but done like twelve times in one game, twelve different ways, with twelve different effects. It’s a tremendous achievement in that sense.

On top of that, yeah, many of the actual mini-games are fun. Heck, the plain old navigation of the space is pretty fun — it’s a cool place to explore, and the hidden passages and the like offer the right amount of that given the emphasis the game puts on story.

On top of that, yeah, many of the actual mini-games are fun. Heck, the plain old navigation of the space is pretty fun — it’s a cool place to explore, and the hidden passages and the like offer the right amount of that given the emphasis the game puts on story.

All in all, it ends up as a meditation on life and death and whether there is such as thing as a good death or a good life. It does it by talking about control: control over your own life, over what happens in it, and almost every mini-game is basically an exploration of unique controls. That is pretty damn weighty territory for a videogame and hugely more ambitious in terms of story than 99% of games, easily. (Gorogoa, a close runner-up to being my favorite from last year, tackles similar themes via puzzles, but isn’t as emotionally direct about it — the puzzles provide a bit of emotional remove). Even more interesting to me is that it opens up yet more tonal space for art games that maybe aren’t about just loss, futility, or impossibility — all of which are certainly great topics, but we shouldn’t mistake “sad” for “deep.”

So… is it as “fun” as Zelda: Breath Of The Wild? No.

Edith Finch focuses on solving on a very hard design problem and does it brilliantly, and it does it in service of way better writing and storytelling than Zelda does. Zelda, which was also in my top three last year, goes broad with stuff I eat up: simulation, diverse play styles, etc. It offers a far heavier weighting on traditional game play. But as an experience it is therefore far more diffuse, and doesn’t reach the same emotional peaks. So it was a greater achievement in pound-for-pound systemic design, particularly given its breadth — shit, it deserves an award just for its fatigue meter — but it’s a bit like comparing a season-long TV show that has a ton of intricate plot that is great fun to watch but has some episodes that are better than others, and a movie that is smaller, quieter, impeccably crafted at that smaller length, and tears your heart out. (In Zelda, for example, we might call out, well, the entire inventory UI as “worst episode ever,” it’s really below standard for BOTW’s overall bar.)

It comes down to building one really huge systemic machine with tons of nooks and crannies, and building a smaller set of elegant ones to address a particular really hard problem. The upshot is that Edith Finch is more startling than Zelda; not as “fun” overall, but for its brief length, for me, more captivating.

Last year was an exceptionally stellar year for games. I may follow this up with (much briefer) notes on some of the other titles that really stuck out to me.

February 2, 2018

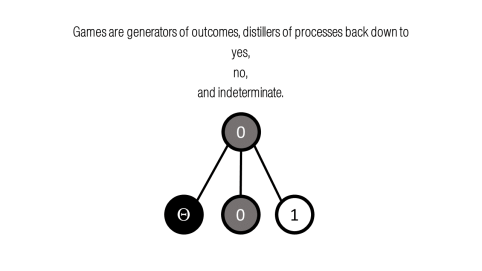

My AAAI Workshop talk on game depth

Today, at the kind invitation of Joe Osborn, I gave a talk for one of the workshops at AAAI-18, one on Knowledge Extraction from Games. I was pretty intimidated about talking at all; any time I stand up in front of people who really know algorithms, systems, or math, I feel like an utter dilettante who is bound to say foolish things. I had been noodling around with some notes around the broad topics of depth and indeterminacy, centered around the idea of games as ternary output machines, so I sent them to him, and he talked me into getting in front of an audience with them.

Today, at the kind invitation of Joe Osborn, I gave a talk for one of the workshops at AAAI-18, one on Knowledge Extraction from Games. I was pretty intimidated about talking at all; any time I stand up in front of people who really know algorithms, systems, or math, I feel like an utter dilettante who is bound to say foolish things. I had been noodling around with some notes around the broad topics of depth and indeterminacy, centered around the idea of games as ternary output machines, so I sent them to him, and he talked me into getting in front of an audience with them.

Along the way, I stumbled into formalizing many of the “game grammar” ideas into an actual Backus-Naur Form grammar. This is something that was mentioned to me casually on Facebook, and which I was aware of from long ago classes on programming, in the context of parsers… but which I hadn’t ever seriously considered as an approach to the more humanities-driven process i was going through with game grammar work. Grammar was just a metaphor!

But as I worked on the talk, I ended up noodling about a fair amount with the idea, and was surprised to see that more of it fell out quite naturally than I ever would have expected!

A large part of the talk is about the question of depth, in particular some critiques of an approach to the idea of “what is depth anyway?” that was kicked off by Frank Lantz and a bunch of other folks during the workshop I attended in Banff a couple of years ago and formalized into a paper a year later. Another big chunk of it (and in fact the “moral” of it all) is about the difference between computation and human experience, and how even our understandings of games are different if we’re a human or a computer.

There is also discussion of Moment #37 and of the game Set.

In the end, I think this may be one of the crunchiest and most in-depth talks I’ve ever given on really nitty-gritty details of the larger game grammar project. I’m in the midst of writing what I hope will be the book describing it all in a way that is hopefully as accessible as Theory of Fun was. In the meantime, this talk gives you the very not-accessible version of a small portion of it, citing Sirlin and Cook and Burgun and more.

You can read the notes I originally sent Joe, the slides themselves, and also watch a video of the actual presentation on this page here. Apologies for the technical glitches! Many thanks to Joe and Matt Guzdial for virtually “hosting” me, to the attendees for listening to my ramblings, and of course, fellow formalist travelers whose ideas I mangled therein.

And if you actually know BNF, feel free to fix this:

game → result

game → game + result

result → system( action ) = ( ( Θ, [ 0,] 1 ) | 1 )

system → side + side { [, side] }

side → player + mechanic + statistic { , statistic }

player → ( ( mind + experience + body ) | AI ) + perception

mechanic → rule { , rule } + statistic { , statistic }

rule → token { , token } expression { , expression } statistic { , statistic }

action → verb [ { + action } ] ( data )

verb → intent + input

input → affordance + action [ + game ]

affordance → player ( data )

January 17, 2018

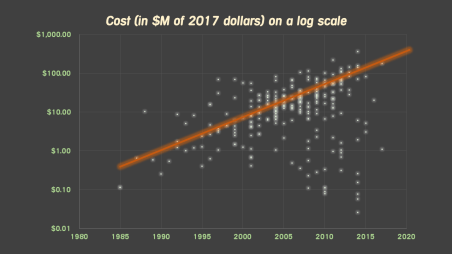

The cost of games

Yesterday I was in Anaheim giving a talk called “Industry Lifecycles.” It was intended to be a brief summary of the blog post of the same title, with a dash of material from my recent post on game economics.

Yesterday I was in Anaheim giving a talk called “Industry Lifecycles.” It was intended to be a brief summary of the blog post of the same title, with a dash of material from my recent post on game economics.

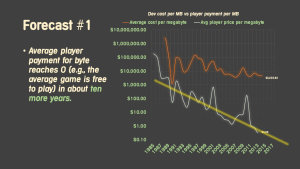

Now, that latter post resonated quite a lot. There was lengthy discussion on more Internet forums than I can count, but it came accompanied by skepticism regarding the data and conclusions. If you recall, the post was originally replies to various comment threads on different sites, glued together into a sort of Q&A format. It wasn’t based on solid research.

As many pointed out, getting hard data on game costs is difficult. When I did my talk “Moore’s Wall” in 2005, I did some basic research using mostly publicly available data on costs, and extrapolated out an exponential curve for game costs, and warned that the trendlines looked somewhat inescapable to me. But much has changed, not least of which is the advent of at least two whole new business models in the intervening time.

So the Casual Connect talk ended up being an updated Moore’s Wall. Using industry contacts and a bunch of web research, I assembled a data set of over 250 games covering the last several decades. This post is going to show you what I found, and in rather more detail than the talk since the talk was only 25 minutes. (You can follow this link to see the full slides, but this post is really a deeper dive on the same data.)

Each game has a reported development cost which, importantly, excludes marketing spend. So this is mostly the cost of salaries and various forms of overhead such as tools. When costs were reported in currencies other than the dollar (Euro, yen, even zlotys) I went back to the year of release, and converted the cost to a dollar value using the exchange rate prevailing in December of that year. I then took all dollar values and adjusted them for inflation so that we are comparing actual cost in today’s money.

The result:

As should be immediately apparent, it’s pretty hard to read the costs, because the vast majority of games cost under $50 million US dollars to make. Outliers are AAA console and PC titles that have enormous budgets, and you have probably heard about them because costs like that tend to make the news.

As should be immediately apparent, it’s pretty hard to read the costs, because the vast majority of games cost under $50 million US dollars to make. Outliers are AAA console and PC titles that have enormous budgets, and you have probably heard about them because costs like that tend to make the news.

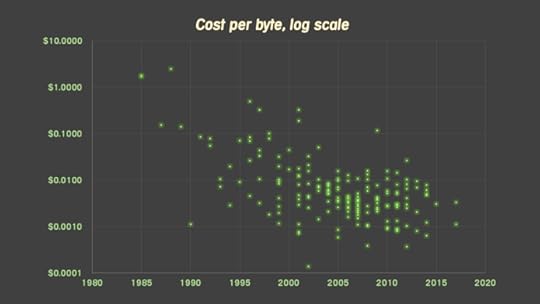

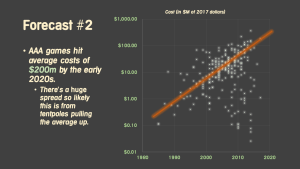

The chart gets a lot easier to read if you plot it on a log scale; in this chart, each vertical box implies costs going up by a factor of ten.

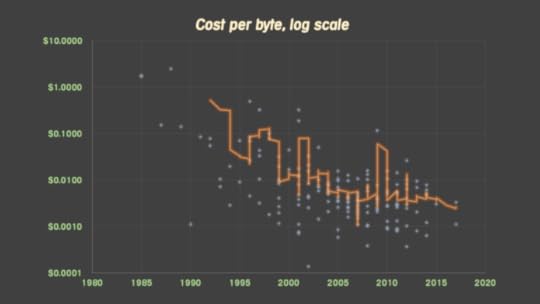

The trajectory line for AAA games is very clear. You can just eyeball that the slope of the line for console and PC releases goes up 10x every ten years and has since at least 1995 or so, and possibly earlier (data points start getting sparse back there). Remember, this is already adjusted for inflation.

The trajectory line for AAA games is very clear. You can just eyeball that the slope of the line for console and PC releases goes up 10x every ten years and has since at least 1995 or so, and possibly earlier (data points start getting sparse back there). Remember, this is already adjusted for inflation.

We can also clearly see the appearance of indie games and mobile games on the chart. I have a lot less data points for these, as you can see, and a truly staggering number of them are released with basically no budget whatsoever. But the vast majority of those are also done at a loss; most of the mobile figures come from games that were at least nominally successful.

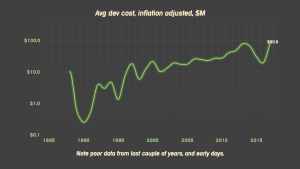

I took an average of the data per year, but it only tells us so much given that the data is weighted towards AAA games, and they pull up the average so dramatically. So I wouldn’t read too much into this graph except to say that even with the lack of really recent data points and older data points, the line is shockingly straight. I will say that a couple of the recent top of the line mobile games have budgets ranging from $5m to $20m — the bottom end is not as low as people think, when doing “AAA mobile.” Even PC indie games with high polish hit multiple millions.

I took an average of the data per year, but it only tells us so much given that the data is weighted towards AAA games, and they pull up the average so dramatically. So I wouldn’t read too much into this graph except to say that even with the lack of really recent data points and older data points, the line is shockingly straight. I will say that a couple of the recent top of the line mobile games have budgets ranging from $5m to $20m — the bottom end is not as low as people think, when doing “AAA mobile.” Even PC indie games with high polish hit multiple millions.

All in all, given reporting bias (crazy expenses are more fun to talk about), and given that exponential cost differences mean the median or “typical” game is certainly not climbing at the same rate, and given the lack of enough mobile and indie titles in the data set, this average line is certainly over-reporting for games as a whole. You may find that somewhat reassuring, especially if you’re working on a $50m AAA game right now.

On the other hand, this picture is actually far too rosy in another way: it doesn’t include any marketing costs. As a rule of thumb, you can say that an AAA game’s marketing budget is approximately equal to 75-100% of its development cost. So costs of getting an AAA game to a consumer’s hands are actually more like double. In mobile, it’s not uncommon to hear savvy shops set aside three to ten times the development budget for marketing, because the market is that crowded.

Looking closely at the data points, there is rather an upward trend to the mobile titles and the indie titles as well. This isn’t surprising, given that as markets mature production costs tend to go up. But it raises the question as to whether there is some way we can compare apples to apples and see if there are global trends. After all, costs rising is fine if revenue and audience rise to match, right? It all comes out in the wash.

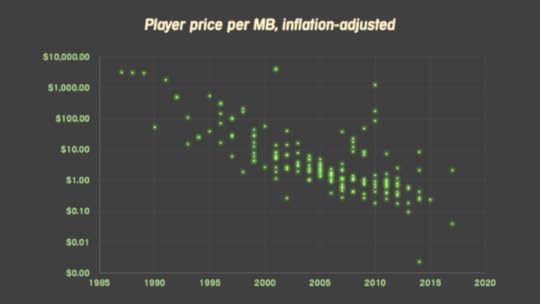

So I went looking for something that would correlate. I expected something like hardware power and capability to introduce “steps” in the graph, for example, and I wasn’t seeing that. Finally, I settled on one simple thing as a proxy: bytes. I went back and for each game, I located the actual install size, space taken up on disk (or on device) after a full install and all sideloaded, streamed, or first day patches were applied.

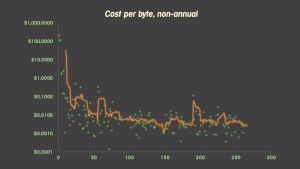

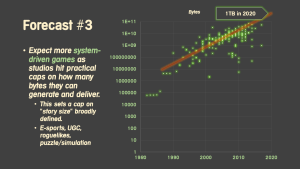

Needless to say, this also had to be plotted on a log scale, because the earliest games on the chart were only a few K in size, and the latest were many gigabytes. The result was this.

So, needless to say, bytes go up. Surprisingly, they don’t tend to go up in stepwise fashion as platforms are released, even back in the midst of console wars. Early on, carts with extra memory were slipped into production midway through the lifecycles of consoles, and later on, new run-time decompression techniques enabled disks to literally just have more bytes on them. For example, the NXE update to the 360 reduced install sizes using compression techniques by up to 30%. Given the addition of various forms of streaming that aren’t cached, for lots of types of games that require a connection, and it’s likely that the byte count here is, unlike costs, rather under-reported.

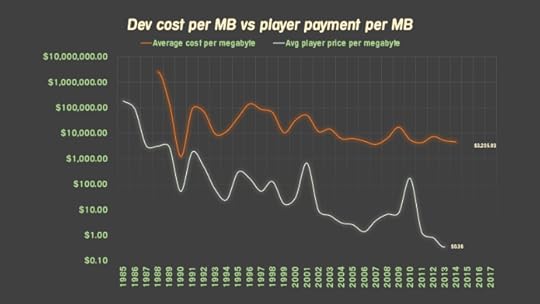

Either way, we now have a simple way to baseline. How many dollars does it cost a developer to create a byte? We know what we want to see: costs falling. In my earlier Moore’s Wall talk, I had looked at costs and costs per byte for the window of 1985 to 2005, and had arrived a simple conclusion (one which I repeated in several later talks such as “Age of the Dinosaurs”): game size went up by 122 times, costs rose by 22x, and therefore we got six times more efficient at creating content.

So here is the simple division of dollars and bytes, on a log scale.

Suddenly what become apparent is that there’s about 10x variability in costs within a given year, most of the time. Looking at the specific data points, I can tell you that most of this can be chalked up to whether the game is content-driven or system-driven. A story-based game, an RPG, something with tons of assets, will just naturally have a higher cost. There are also some famously troubled productions on in the data set; no surprise that they tend to sit towards the upper end of the range for their respective years.

The real eye-opener is that the $5m indie mobile title and the giant $100 million AAA cross-platform extravaganza cost the same to make in terms of megabytes. (They were actually off by only 3/1000’s of a penny). That’s likely because salaries are salaries, and don’t move that much when you change segments within the industry.

More troubling to me was that eyeballing the average cost per byte, it looks like we have plateaued.

Unreal Engine 3 and Unity both launched in the 2004-5 window. I would have expected these two amazing toolchains to have hugely helped the cost per byte. Instead, it kind of looks like it went flat.

It raises the disturbing possibility that maybe standardizing on these two engines has actually blocked faster innovation on techniques that reduce cost. I don’t know what else might be contributing to the flattening of the curve. Maybe the fact that Unity and Unreal are designed around static content pipelines, and don’t do a lot more with procedural content affects this? Maybe this is actually the good result, and costs were going to boomerang back up? There’s no way to know. I even unrolled the yearly average and simply sorted the games by release year to see if I was seeing things, and if anything it looks flatter because it reduces the impact of those outliers.

It raises the disturbing possibility that maybe standardizing on these two engines has actually blocked faster innovation on techniques that reduce cost. I don’t know what else might be contributing to the flattening of the curve. Maybe the fact that Unity and Unreal are designed around static content pipelines, and don’t do a lot more with procedural content affects this? Maybe this is actually the good result, and costs were going to boomerang back up? There’s no way to know. I even unrolled the yearly average and simply sorted the games by release year to see if I was seeing things, and if anything it looks flatter because it reduces the impact of those outliers.

Data complexity in games is a real thing, and it is something that players, I think, routinely hugely underestimate. This post by Steve Theodore on Quora is illustrative. In it he shows a 1997 character that took ten working days, then one from ten years later that took 35. His estimate for a character today is a hundred days. What used to be one 256×256 texture is now authored as many 4096×4096 textures, for specular maps, bump maps, displacement maps, etc etc.