Raph Koster's Blog, page 6

November 27, 2017

Some current game economics

Recently I was over on The Ancient Gaming Noob blog, where a discussion broke out on all the recent discussions about lootboxes, game development costs, game pricing, microtransactions, and all the rest. In particular, it was prompted by this video:

Despite the title of that video, games are indeed plenty expensive to make, and more specifically, they’re definitely too expensive to make without the revenue brought in by all this upsell stuff.

But the reasons why are complicated, and worth explaining in more detail. So I did, in comments on that blog, and the replies there suggested that I needed to make a blog post of it.

So here it is, basically a fix-up post, and not up to my usual essay standards, being as it is cobbled together from several impromptu comments. Bold text is comments I was asked or replied to.

First off, to address some of the figures in the video: cost of goods is not the same thing as cost of development. I’ll share some figures for that later on, but I think that by and large the public doesn’t really know how much games take to make.

Is it “too expensive”? Well, that’s a value judgement. We could look back at the history of studios that overextended and failed, and notice that it sure seems to be a high-risk business. But restaurants are a high-risk business too.

So question one: How many studios fail because video games are “too expensive to make” versus having a bad business plan or unrealistic expectations? (Or just a bad game?)

There is no question that there are plenty of studios that overspend. And yes, restaurants are extremely high risk businesses. But restaurants mostly compete on fixed costs — ingredients are largely the same for everyone, and barring something weird, their prices change at the rate of inflation. Games, not so much; every year a game that is competitive costs more to make.

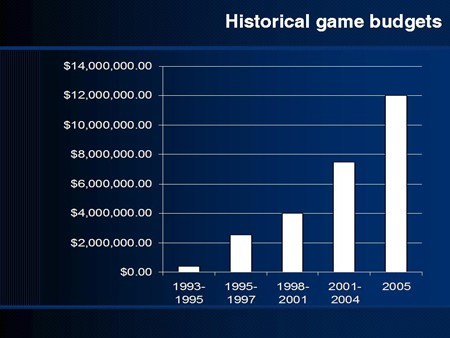

Data from 2005.

I did a talk back in 2005 about this. It’s here: https://www.raphkoster.com/games/presentations/moores-wall-technology-advances-and-online-game-design/ You can find graphs in there of the rise in costs for games. In short, it’s been an exponential curve for a few decades now. In 1995 it was around $2m to make a top-notch, AAA game. In 2000, it was more like $4m. In 2005, it was $12m. In 2010, $40m. In 2015, $120m or more. The biggest games are costing north of a quarter billion dollars to make. These figures, by the way, are already adjusted for inflation, and don’t include marketing money.

In terms of raw data generated — literally, the number of bytes the game takes up — we can easily see that dev teams have to generate many orders of magnitude more bytes than they used to. Voice and artwork have absolutely skyrocketed.

The result: a game like Assassin’s Creed has a staff of 1500 at seven studios in five countries.

Through it all, games mostly have sold for $60. Which used to be the equivalent of $100, because of inflation. Only today, thanks to Steam sales and the like, games actually sell on average for less than full retail.

The key thing to understand is that the public doesn’t buy B games. A game with stellar gameplay and less than state of the art graphics is generally simply left on the shelf. Yes, indie games with distinctive art have managed to break through so everyone will cite counterexamples, but looked at statistically, it’s something like 99.9% don’t. The average game on mobile makes somewhere between $0 and $100 total ever — and the typical game makes nothing. The average sales across all games on Steam is only 32,000 copies — that’s including all the hits that sell tens of millions. Metacritic scores show that you basically have to be up there at 85+ to be viable, and it’s very hard to get that without state of the art tech and visuals.

“Too expensive” isn’t a measure of just cost though, it’s a measure of risk. As costs have risen, we have seen massive consolidation across the industry. There used to be over 20 publishers of AAA games in the 90s. There also used to be dozens of third-party studios. As costs have risen, third parties have either died when they overextended trying to reach the quality bar, or they were absorbed by the larger companies. Publishers overextended by banking on major franchises, and when one didn’t hit, went away.

This cycle tends to reset only when new technology platforms come along that don’t let you do expensive productions because they don’t have the graphics horsepower. Mobile was like that, so was Flash gaming. But as soon as you can overspend on graphics, it becomes mandatory, and then the spiral starts. Early MMOs was like this — Ultima Online cost only a couple of million, Star Wars Galaxies under $20m, Sims Online and WoW north of $80m. Facebook games like Cityville cost more than UO to make! I wrote some about that in my post “An Industry Lifecycle.”

Basically, there isn’t a good business plan. There aren’t any realistic expectations. Any sane business person would say “don’t make games.” You can see this in MMOs now — where just getting 100k people subbing to something ought to make a highly satisfactory viable business… but go look at player reactions to visuals that aren’t at the absolute top end.

This is why service games — which reduce volatility and drive customer lock-in — help. And why free to play — which lowers marketing costs, hugely expands audience, eliminates price sensitivity, and removes spending ceilings — makes a difference. Bigger bets, fewer games, and try to make a service with microtransactions. It’s the only sensible way to play in the market if you have money.

If you don’t have money, the sensible thing to do is to make as many cheap small games as you can and hope one hits big and goes viral, so you have money and can switch to making a service-based game, or just keep making small ones. Just don’t switch to making a single bigger game that isn’t a service, because if it fails to hit, you’re dead. And it takes money to even make the public aware of your game. Marketing costs are huge. These days, $85m for marketing an AAA game isn’t a crazy figure. That would buy you four SWGs.

None of this is helped by the fact that the overall ecosystem has also changed a lot in many ways, which I wrote about in my post “The Financial Future of Game Developers.”

When games are cheaper to make, we get indies and creativity and explosions of awesome in the market. When games are expensive to make, we get predatory business models, sequels, and clones. People are complaining about predatory business models, sequels, and clones — so, games are too expensive.

November 1, 2017

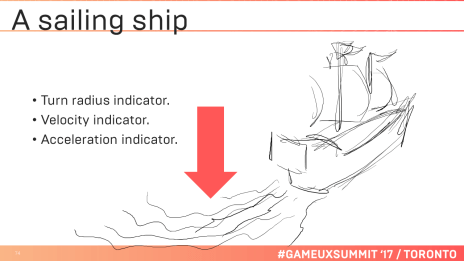

My GameUX Summit keynote: (Dis)Assembling Games

A while back I gave a keynote at the Game UX Summit in Toronto. Video of the talk is now up, so I’ve gone ahead and posted up a whole page for the talk that has the slideshow as well as the video.

A while back I gave a keynote at the Game UX Summit in Toronto. Video of the talk is now up, so I’ve gone ahead and posted up a whole page for the talk that has the slideshow as well as the video.

The talk was similar to some of my other talks on game grammar, but with a focus on user experience: the way in which we can see each UI button as a “game,” each high-level experience as a “game,” and that therefore there are huge commonalities between UX design and game design and narrative design… but there are also big differences when we dig into looking at them granularly. In some ways it therefore draws on the same stuff (and many of the same slides!) as my talk on Game Grammar from PaxDEV, and also from my blog post about UX vs game design.

If all you want is the video, though, the organizers have you covered. And if you watch to the end, you’ll get to see some stuff about some of the tabletop games that I have been working on for the last few years:

September 28, 2017

Ultima Online’s influence

This is the first question I’m answering from the ones I got for UO’s 20th anniversary.

This is the first question I’m answering from the ones I got for UO’s 20th anniversary.

I never played UO, so not knowledgeable. Maybe a routine question, but how do you think #UltimaOnline pushed the genre forward?

This is a big question.

I think we should start with a look at what the world was like in 1995, when the project was formally launched. Most people connected to the Internet via modem, and many of them were on 14.4k or 28.8k speeds. The 56K modem didn’t come out until 1998.

For comparison, my cable Internet at home gets 70.7Mbps for downloads. That’s 70,700k per second, versus 14k or 28k. The bandwidth difference is almost 2,500 times as much, if we look at the 28.8k modem. And that’s not counting speeds – ping times everywhere are quite a bit faster than they used to be. Old routers used to add 20ms just from you going through them, and getting 250ms ping time to anywhere was considered normal and if sustained, pretty good.

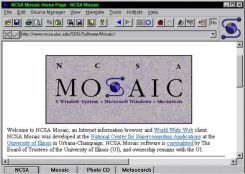

Before this, we used Lynx, which was a text-based browser.

Mosaic launched in January of 1993, and Netscape Navigator in 1995. Until Mosaic, the web didn’t have pictures. There was no Google, but there was Yahoo! and Webcrawler. Amazon launched in 1994 but only sold books and wasn’t a big deal yet. There were only around 100,000 websites on earth. Your dial-up internet service provider fees would be in the range of $20-30 a month.

Internet discussion happened mostly on Usenet, though there were some fledgling BBSes, and of course things like The WELL and discussions on the many closed online services like Prodigy, America OnLine, and CompuServe. This latter one charged by the hour — $5 to $16 per hour – and was flailing enough that AOL bought it. (Prodigy had pioneered flat rate pricing a few years earlier).

Prodigy streamed each screen down as an image, even the text ones.

Gaming, of course, was alive and well, including online gaming. The top games in 1997 included Final Fantasy VII, Goldeneye 64, Castlevania, Star Fox 64, Parappa the Rapper, The Curse of Monkey Island, Age of Empires, Mario Kart 64, Fallout, X-Wing vs Tie Fighter, Theme Hospital, and Total Annihilation. Max game resolution, if you had a powerful rig, was generally 800×600.

During the development of UO, we carefully watched the development and release of Diablo and heaved a sigh of relief when we realized it was a graphical version of Rogue or NetHack, rather than a persistent world (today people toss around “roguelike” as a common term. It didn’t use to be). I remember a bunch of us gathering around one computer to play the demo version, as we saw that first off, its graphics were much better than what we were already committed to, but its multiplayer was very limited. “That is forbidden in the demo” is still an occasional catchphrase in our house – our research sessions always ended there at the last doorway in the single-level demo.

WorldsAway was derived off of Habitat

Quake had come out in 1996, and many of the art team played it on the company LAN in the afternoons. Most online gameplay was LAN play, in fact; services like DWANGO (launched in 1994) allowed LAN games to be played over the Internet using a dedicated dial-up service that served as a matchmaker. Around 1995 to 1996 TEN and MPath (aka MPlayer, and eventually GameSpy) showed up, and started bundling games with LAN play into a subscription that let you play them online via the Internet. These services varied in price from $30 a month to $30 a year, on top of ISP fees, but by and large didn’t offer much if any persistent world gaming (TEN had Dark Sun Online which came out in ’96).

There were MMOs, for sure. You can read over the timeline to see just how many preceded Ultima Online – quite a lot, particularly if you count all the graphical worlds, as I do. Simutronics had its text-based MUDs running, such as DragonRealms and Gemstone. WorldsAway, a version of Habitat, was on CompuServe, as were Islands of Kesmai and Air Warrior. The aforementioned Dark Sun Online and also Lineage were played in the UO offices during the development process as well, though they were both in pretty rough state.

Meridian 59, like EverQuest after it, started out with a small game window with inventory and chat boxes around it

And of course, Meridian 59 beat UO to market as well. Sometime in 1995 or so, Mike Sellers logged into LegendMUD, and I toured him around. If I was online, I often greeted newbies personally, and if they were people involved in creating MUDs, I would offer to tour them around the game, showing off the many things that it did that were different from the run of the mill. After the tour, Mike talked to me about a possible job on Meridian 59, and I turned him down because Origin had already made an offer. I recommended Damion Schubert for it instead.

Lineage, when I first tried it, consisted of one house, that you stepped out of onto a killing field and basically died immediately. DSO was much larger, but had some sort of turn-based combat. If you got hit, you were put into the turn sequence for everyone in the fight; this resulted in a blob of dozens of players waiting a half hour to swing once or try to escape the fight. (I honestly don’t know whether this was a bug at the time or what – I never played it again). Sierra had launched The Realm in 1996; it had a side view, and each fight was actually an “instance” – when you engaged in combat with another entity, outsiders saw a cloud with fists and whatnot poking out, and you were sent to another screen to do battle.

Ultima Online COULD have been DragonSpires, but Origin decided to build their own

As Richard Garriott, Dr. Cat, and others tell it, the idea for an online, multiplayer version of the Ultima series had been around for quite some time. There was an abortive deal with Sierra to create a “Multima.” Dr. Cat, a long-time Origin veteran was had left the company, was interested enough in online gaming that he created a game called DragonSpires which was way ahead of its time, and the predecessor to Furcadia. Richard and Starr Long went to the executive greenlight board at Electronic Arts multiple times trying to get money to fund a prototype, and after being turned down multiple time, finally got a check for $150,000 or $250,000 (I have heard varying figures) directly from Larry Probst, the CEO.

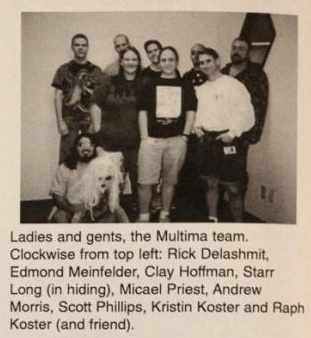

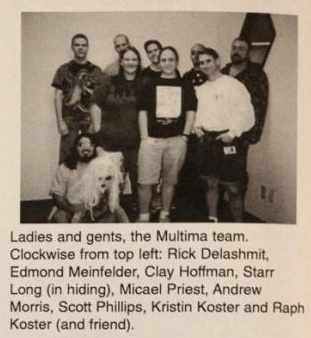

When they went looking for people make the game, they ended up having to look outside the company, and the place to look turned out to be MUDs. I’ve told the story elsewhere of how they found Rick Delashmit and from there they found my wife and I as designers, where we had cut our teeth in online world design on LegendMUD.

LegendMUD soft-launched in ’93 and officially Feb. 14th, ’94. At least five Legend players were involved with UO & the early MMO industry.

The state of the art in MUDs was quite different from what was going on in online services. Most of the games on the online services were basically hack and slash with quests. Most of the most popular MUDs were also hack n slash, the Diku style of game, which due to its hardcoded nature didn’t have much in the way of interactivity with objects and NPCs. LegendMUD, and the mud we had played before it, called Worlds of Carnage, were different from other Dikus. Thanks to an embedded scripting system, they had much more interactive worlds more akin to what was happening in the MOO and LPMud circles.

In MOOs, MUSHes, and LP’s, the use of scripting and domain-specific languages had opened up enormous potential for virtual worlds. Some of these kinds of worlds handed over coding capabilities to end users. Some didn’t but because they were dramatically easier to mod than a Diku, had all sorts of experimental things going on. Bear in mind we’re talking text-based games running on computers far less powerful than your typical smartwatch, but MUDs were exploring design ideas such as

Player driven voting systems and player governments.

Procedurally created zones.

“Roomless” worlds where the descriptions of locales were procedurally generated based on what landmarks were in nearby coordinates.

Agent-based AI systems where creatures had more autonomy and a bit of an ecology.

Spellword languages for dynamically creating magic.

Roleplay-mandatory worlds with permanent death.

The original UO logo, before marketing. I still have a team t-shirt with this on it.

LegendMUD itself was notable for having things like vehicles you could drive or fly, ships you could sail, furniture you could sit in, a rich chat system with moods and adverbs, a spell-word based magic system, an herbalism system that used the pharmacological properties of real world herbs, an out of character lounge anyone could teleport to, and more.

A lot of the discussion on features like this came from the fabled MUD-Dev mailing list, run by the redoubtable J. C. Lawrence. And it was on MUD-Dev where the designers and programmers of all the above games ended up gathering and swapping ideas and debating the future of online worlds. Out of this ferment came Ultima Online.

When we posted up the first FAQ for UO on our skunkworks domain owo.com (“Origin worlds online”) in 1995 or early 1996, a black website with little suns and llamas on it, and a giant long list of promises written in text, it was not only the first website ever created within Electronic Arts, but it also was a bit… ambitious. (Alas, the text seems lost to history).

Given all the above context, here are some things that Ultima Online attempted, and mostly pulled off.

I’ll start with the least remarkable, which was pure scale. A tile-based seamless world that was 4km on a side, with multiple ecologies. Further, one that supported multiple floors, in 2d isometric, and 3d terrain texture mapping. Although the art wasn’t as detailed as Diablo, this was something they (and most any 2d game competitor) simply couldn’t do. Being able to walk upstairs or into a basement in a building in game was startling at the time. Having actual 3d sloping terrain of any sort, likewise; most 2d games still faked elevation changes with optical illusions.

A tile-accurate map of UO, reduced by about 50% or so. Not including dungeons.

This map was enormous, for the time. So was the art asset load. There were sixty-one unique models for creatures, and each, though modeled in 3d, was output into sprite frames – 15 frames per animation, in eight directions. Forty-eight weapons. And hundreds of small items of many sorts, many of them interactive. In text games, you see, it had been easy to just invent more items, and we wanted that freedom in UO. Consider that the average number of items you could pick up or interact with in other graphical MMOs at the time was, for most locations, zero.

And all this was in service of supporting 2500+ people at once in a given world, literally ten times what other worlds typically supported. (Linux at the time even came out of the box with a limit of 250 or so file descriptors). More people in one world, interacting. If anything, the map was too small, which led J. C. Lawrence to call the game “a hothouse.”

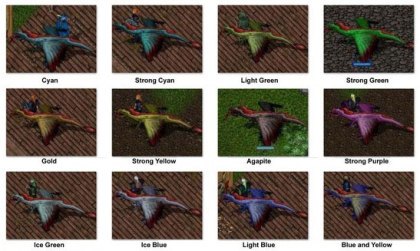

Scale was one thing, but a key difference in UO was that this stuff was actually used in more than one way. To my knowledge no previous 2d RPG had ever shown all your equipment on your character in game, but it was something that we took for granted, coming from the text MUD world. We came up with a means of mapping color ramps to grayscale pixels on the items, termed “hues,” which allowed us to take every item in the game and not just tint it, but actually change it to have multicolored patterns. This was applied to all the clothing, many of the creatures, all the armor and weapons and hair and skin. (The art team was not happy about this at all – we had to make the case to them that giving the power to the players was critical). UO was the single most varied fantasy world ever created, when it launched.

An excellent example of hue-based “partial tinting” — any parts of the sprite left in true grayscale would map to a palette, and any parts not gray would stay in original colors.

Don’t underestimate what seems like a trivial thing. Dye tubs existed in the world, which spawned with random hues. Dye tubs could be copied. Players could find objects that spawned in the world with rare colors, copy them to a dye tub, and then dye clothes with that rare color, cornering the market on a specific shade of green. There was an economy just for colors in Ultima Online. This led to lily-white wedding dresses, guilds that color-coordinated their uniforms, a pimp named Fly Guy on the docks with a purple feathered hat, and much more. When a bug in the system created “true black” as a hue (a palette with only #000000 black in it) it instantly became a highly coveted color that led to mass murder and economic mayhem. Eventually, I applied colors to metallic ores, and this led to a whole metal quality system as well. It’s not an exaggeration to say that the simple hues system enabled enormous amounts of player dynamics that frankly, still aren’t seen in most MMOs today.

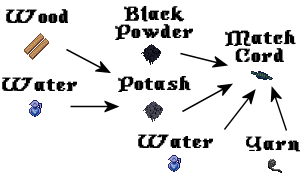

The world was also varied in behavior. The “resource system” has been written about extensively, and didn’t survive to launch. But the underlying data for it remained, and served as the basis for all sorts of simulation. Every patch of water was something you could fish in. You could shear the wool off of sheep, and it grew back. You had to rotate through stands of lumber, as you exhausted the harvestable wood. Name your cow Millie, milk her, then when you chose, slaughter her, and you got meat filets – “filet of Millie.” You could take that to a steak or a meat pie. “A meat pie of Millie.” For a brief period, you could do that with the meat from another player. Scissors cut cloth. Knives could whittle wood. Looms made cloth, if you had the flax or the wool. Just about everything was craftable — a current list for blacksmiths is pages long.

Lights turned on and off. NPCs moved about, and at first, closed up their shops at night. Bulletin boards in the towns weren’t static dressing, but message centers where players could post notes for one another. Town criers shouted out the latest news, and you could ask any NPC for directions to landmarks. Every NPC was born with a unique name and a rolled-up personality, and they could die and never come back. Fruit trees gave fruit. When you sailed around on a ship, the tillerman told shaggy dog sea stories. The book in the game didn’t just drop random bits of backstory – they did, of course, but you could also make or buy a blank book, and type in your own story, and then that would be added to the possible books that could spawn, and could appear anywhere in the world.

The “Baja Council” all wearing antlers, in uniform

You could create a microphone crystal, and link it to a speaker crystal, and use it to provide loudspeakers for an event. A chain of explosive potions would set of a chain reaction, like a fuse burning down. You could drop things on the ground, and spell out words, or leave a lure of stuff for creatures or animals to pick up. Monsters looted you, if they were victorious. Even when they spoke gibberish, they did so by listening for words you said, and repeated them back to you, which tricked many a player into thinking there was a real language to learn.

The simulation ran deep in UO, so much so that even when the main simulation was turned off, the game still ran as a giant simulated fantasy world. When you look at a typical house screenshot, realize that everything in that house was interactive to some degree, even if it was minor. You pretty much have to come forward in time to Dwarf Fortress or Minecraft to find something comparable in a major game.

This sort of thing unlocked higher order features.

The Golden Brew Players, a theater troupe, meet Lord British

Theater troupes could memorize plays, take over empty stages, and go on tour performing Shakespeare. Costuming was a thing. So were player cities creating their own guards in uniform – players volunteering in shifts to protect homes against playerkillers.

Guilds in UO could go to war with one another, could own a castle, and share a hoard. They could grant titles to the members lower down, and at the start even had a democratic voting system for leadership. Guilds prior to UO were a much simpler affair, and in most online games the list of possible guilds was hardcoded into the game at the outset.

Not that you needed a guild war; UO famously permitted anyone to kill anyone outside of the boundaries of town. The amount of griefing, playerkilling, and bad behavior in UO was legendary, from boring ambushes to boobytrapped chests that blew up in your face to magical gates to tiny islands leaving you stranded in the ocean. This cost us an ungodly number of subscribers, and led to many negative reviews early on.

A player house in UO

Housing in earlier room-based games was quite a different affair, if it existed at all. In UO, the placement of actual structures on the physical map at 1:1 scale with the rest of the world meant real estate was a real thing, with home values, lack of building space, and much more. This is a thorny enough problem that most worlds back away from it now, because of problem with overbuilding. Eventually, UO allowed full Sims-style ability to design your house within its plot.

An economic analysis of UO by Zach Booth Simpson and a few academic economists

Shopkeepers in UO launched with fluctuating prices and inventory based on local supply and demand. And supplies certainly did fluctuate! Early on there was a failed closed economy, but even with the more typical faucet-drain economy that UO moved to, there was enough there to basically create the market for eBayed virtual goods, as well as constantly changing prices within the game itself. This player-driven economy saw players set themselves up as commercial kingpins, not just as combatants.

Of course, players could just hire an NPC and set it their house, stock it with goods, set prices, and hang a sign out front (yes, you could actually hang a sign… there were about twenty to choose from, and you could select a name for the shop). Players built their small commercial empires this way.

The UORares rune library on the Atlantic server.

And that variety in play was everywhere. Bards whose music calmed angry monsters. Fishermen who pulled up messages in bottles, eventually with treasure maps inside. (When you got to the destination, the game spawned an entire encounter for you; this concept, called a “dynamic point of interest,” allowed the creation of entire orc camps, buildings and all, on the fly, then cleaned up later, leading to a more dynamic encounter map in general). Blacksmiths whose mark on a sword was a big deal, and whose popular smithies would have lines of people outside, because they were the only one that players trusted to repair their sword adequately. Mages could learn spells and inscribe them on scrolls and sell them to others. Museums of “recall runes” existed – teleportation depots, basically, where runes with farflung locations encoded into them sat on display for mages to come to and open mystical gates to other locales.

You learned by doing – and early on, by watching, until we had problems with people inadvertently learning stuff without wanting to – similar to the Elder Scrolls games. This meant practice yards were full of people swinging away at training dummies and practicing archery. Because the power spread between players was actually fairly tight, you didn’t get left behind by others outleveling you. In fact, a common tactic to take down advanced playerkillers was to go after then in naked mobs because sheer numbers could outweigh the power of even the best-equipped player. Gear wasn’t destiny – everything broke, decayed, wore away. Food spoiled. Stuff could only be repaired so far, and truly rare things were safely put in the safety deposit at the bank rather than risked out in the wild.

Don’t think that this was all an accident. This was consciously designed to be this sort of emergent world, carefully, skill by skill and object by object. There were happy surprises and unpleasant ones, but interdependence, economy, ecosystem, player types and roles — all of this was actively designed for and we attempted our best to anticipate behaviors. Theater troupes? Rune libraries? Real estate pricing? These were surprises that we expected to happen, in a sense. Even the weird ones, like people dropping enough objects in one tile to cause a DDOS attack on players who got close, or people piling up chairs until they could climb onto a player house roof, break in, and loot it dry.

All of this was prodded along by admin intervention: gamemasters who participated in the game, running events, and volunteers who helped them. Large-scale roleplay events and competitions happened all the time, from sporting events (wrestling matches!) to game-wide scavenger hunts. Players dressed up as orcs and actually took over the orc fort, and eventually we just let them run it instead.

Skull the Troll, from the PVPOnline comic strip, was originally a UO monster

This community was actively managed — at first, by me and a few others, then eventually by a team, at a time when the state of the art was .plan files. Short stories and poetry both from the players and from the team were posted on the website – this is part of how Scott Kurtz, today an award winning cartoonist and creator of Table Titans and PVPOnline, got his start. For a while, when we saw that the player-run forum sites were growing too popular and therefore getting too large a bandwidth bill, we quietly hosted them for the players on our own servers. Those sites grew into key parts of IGN and other such major game news sites – we never got a cut.

And every update, we posted up “here’s what we are thinking of changing and why.” There would be an open IRC chat forum, called the House of Commons, where players could join and make their case for different changes, advocate for specific fixes, and in general argue with the developers. Then changes moved through a regular process, from In Concept to In Development and thence to In Testing and deployment, in a transparent open development process that provided visibility on everything we could.

All of this, for a flat monthly free, on the open Internet. And that was a major business shift of its own – even Meridian 59 didn’t launch with that straightforward a model.

This was most of the original core team that conceptualized and built the basic game.

If at this point you are comparing all this in your head to World of Warcraft and wondering whether UO had any influence at all, I think that’s fair. Reading player stories from Ultima Online today has this strange quality, where you’d swear that no game could ever have offered that sort of freedom and depth and detail… because no game today does.

Even at the time, competitors ran ads saying “why play to bake bread?” UO was consciously an attempt to create a parallel fantasy universe in which you could live: be it as a craftsperson running a tidy shop, an adventurer deep in the bowels of a dungeon, an itinerant storyteller who made her living picking pockets and roleplaying, or even an explorer who was trying to mark the furthest regions of the map.

Today, if you point at the philosophical heirs of UO, you find them in unexpected places:

Minecraft, which has quite a similar underlying resource system, similarly leveraged for crafting. This is possibly via Wurm Online and Runescape, both games heavily inspired by UO.

Survival games, like PUBG, which recapture that sense of utter fear involved in leaving town. UO was a full PVP world, where anyone could attack anyone outside the confines of town.

Games like Animal Crossing, where that feeling of an ongoing world that lives without you, where you can live a peaceful existence picking fruit and catching fish and decorating a house, remains intact. Even Facebook games.

A game like Eve Online outright stated an intention to be “UO in space” when it started up.

Were these directly inspired by UO? I don’t know. Housing and crafting and the notion that there are many ways to play the game, those were definitely things that spread outwards from UO, just as they were taken in their turn from ideas on MUD-Dev and text muds and early graphical games. The eBay market for UO goods created gold farming, and eventually that led to the free-to-play microtransaction model, through a twisty chain of influence.

But it’s impossible to make clear claims. As I mentioned, there were many fellow travelers, on many other projects, and we all swapped ideas and gathered for dinners at GDC. In many senses, UO had almost no “firsts” — you can always find an antecedent for something it did, somewhere, probably for everything I’ve listed above. Convergent evolution means many of the innovations were doubtlessly invented by others as well. At the same time, it’s hard to picture some of these things spreading as they did, in UO’s absence.

I could go on. Just to launch UO, we had to invent early forms of database sharding (the term likely comes from UO), pioneer the large-scale use of VPNs, pioneer character customization, invent seamless multiserver clusters, basically invent modern community management, invent the now-ubiquitous codes on cards for accounts or payment… many were simultaneous inventions, but we basically had to do a whole bunch of new things. You see that pic of the core team up there? The average person in that picture was in their mid or early twenties, on their first game industry job.

No doubt as a consequence of that: many of the things that were tried in UO didn’t work. They broke under unforeseen player stresses – no one had ever designed for thousands of people playing at once in a simulated economy; or they collapsed when the (puny by today’s standards) computers we used as servers couldn’t handle the load. Many were simply bad ideas, as our understanding of player psychology and behaviors evolved. UO chased the industry away from player-vs-player combat for years. To this day, Richard warns people away from trying to tackle a simulated ecology (not me, though, I’m still determined and stubborn). It’s important to realize that UO was a profoundly broken experience in many many ways.

And of course, since players managed to reverse-engineer most of the game in short order, just about everything that worked, or didn’t work, was worked over, redesigned, and recreated by players in the hundreds upon hundreds of “gray shards” created since 1998. At least three server codebases, complete with scripting languages, compatibility with the official client, and, at peak, hundreds of thousands of players, outstripping the official servers. When I got to China for the first time, I learned that UO was well-known there, despite never having launched officially in the country; it was because so many gray shards were run there that it helped create a generation of MMO developers. For a while, UO was probably the world’s most popular user-run virtual world codebase, and thus a true heir to the MUD tradition.

The original painting done by the Hildebrandt Brothers for the Ultima Online box cover

But in the end, if you ask how it pushed the genre forward, I think the answer is that it did so by offering a dream, a dream that even today people compromise on and don’t offer. This idea of a true parallel world with its own life, its own ongoing history, one that doesn’t pander or make concessions for tutorials, bolted-on quests, pay-to-win gear schemes, or any of the other niceties of the business of games… the idea that “what if you just actually modeled another world, in as much detail as possible, and let players loose?”

That’s something that frankly, still isn’t really on offer. So to answer your question: Ultima Online pushed the genre forward by providing an early Camelot, a shining city on a hill that technology wasn’t really yet able to build. It was, and remains, aspirational. It started retreating away from its own lofty goals almost immediately upon launch, and nobody else has managed to make something quite like it.

So that imperfect, barely functional, insane thing: that’s all we got. It’s twenty years in the past – how implausible! And somehow, it still feels like something always twenty more years in the future.

September 25, 2017

Video of UO 20th

I didn’t make it to the 20th anniversary celebrations for Ultima Online out in Virginia this past week, but luckily an attendee has posted up video of it! This segment here is the presentation by Richard “Lord British” Garriott and Starr Long on the early history of Origin and of UO.

There seem to be several more videos of the event there, linked from the original.

September 24, 2017

Ultima Online is Twenty

The early UO team, from Nov 3rd 1995’s issue of the internal Origin newsletter

Today marks the twentieth anniversary of Ultima Online‘s launch day.

Funny enough, I have no particular memories of that day.

I’ve written a fair amount about UO in the past, so I am at a bit of a loss as to what to say, other than “thank you” to the folks who hired me and let me work on it, and “thank you” to the players who played and continue to play it. It has been an honor.

I posted on Twitter and Facebook asking for questions to answer and stuff to write on. One problem is that I can’t remember what stories I have told when… about the wisps? About tillerman stories? About the books system? Sherry the Mouse? The birth of orc roleplay? About burning to death in Ultima 8? About third party tools? About trying to develop 3d terrain? About character customization, which wasn’t really a thing before UO — and the faces system that didn’t quite make it? I just don’t remember. So if you want to hear more about anything from the way early days, let me know here or on Twitter or Facebook or whatever, and I’ll see about doing replies in a fresh post.

In the meantime, these are some of the past posts on UO that I would recommend on the blog:

UO’s resource system parts one, two and three. These describe how the underlying world of UO works — from the “infamous dragon example” that never came to fruition, to how it still underpins crafting and AI.

A UO postmortem of sorts, which is a written one I did and not the same as…

UO Classic Game Postmortem, which was a GDC Online panel.

The evolution of UO’s economy

Database ‘sharding’ came from UO?

How UO rares were born

Random UO anecdote #2

Random UO anecdote #1

Ultima Online is fifteen

“Making of UO” articles at MMORPG.com — these are actually my notes on

The end of the world covers several games, but includes the story of the end of beta.

September 22, 2017

What old tennis players teach us

First, read this article on how older players have come to dominate the top ranks of tennis, and how the reason why is probably money.

I found this utterly unsurprising, and here is why.

These things are axiomatic:

In any system where rewards accrue to “winners,” it results in those winners doing even better next time.

The result of this is always a power law curve. My favorite shorthand for this is “the typical person in the system ends up below average.”

Meanwhile, the winners at the top compete and drive up costs of entry.

As this happens, the basic cost of entry to participate in the system rises, and the result is those without resources get closed out.

The curve eventually grows towards a cartel at the top, and eventually a monopoly.

The system as a whole stops growing — customers, players, etc.

Attrition for a variety of reasons means the system dies.

This is true in tennis. It is true in a game’s PVP system. It is true in the indie gaming business. It is true in MMO subscriber acquisition. It is true with Amazon and WalMart versus small shops, and it is true with Facebook. Sometimes this means piling up money, sometimes users, sometimes connections. But the nature of the asset doesn’t matter. It’s about the size of the hub.

Systems that don’t destroy their kings on a regular basis end up destroying the kings and the citizenry. And life under a king is never advantageous to the citizens, either.

There is a sweet spot for ecosystems, you see. A certain level of connectedness, a certain level of inequality, gives us teams and cities and competition and cooperation. But a level above that gives us stagnation and centralization and loss of freedoms. There are thresholds in systemic complexity that serve the system but do not serve the components of the system well. Having hugely paid celebrity tennis players serves them and the system of tennis that monetizes that celebrity well, but does not serve anything else in tennis well, just like having a music scene of only the major rock stars does not serve garage musicians well.

This is game design: set up your system to cause ferment, not stability and inevitability. But it is also long-term thinking in business, and for that matter in social structures. Runaway hubs cause problems whether they are guilds controlling servers, tennis champions benefitting from big prizes, or companies that dominate online commerce.

August 27, 2017

Consent systems

I was asked on Twitter recently for references for my mention of “consent systems” in my talk on “What AR and VR can Learn from MMOs.” I didn’t have any handy at the time but today I had some free time so I went looking.

I was asked on Twitter recently for references for my mention of “consent systems” in my talk on “What AR and VR can Learn from MMOs.” I didn’t have any handy at the time but today I had some free time so I went looking.

Textual antecedents

The basic concept can be found throughout roleplay social virtual worlds such as MUSHes. (For example: Black Ops MUSH, The Lady’s Cage MUSH, Star Wars Omens). These sorts of worlds typically do not have combat systems, and rely heavily on free-form emotes (though the commands there more often have the syntax “pose” or “emit” or the like). Like any other full roleplay environment, of course, fights and conflicts happen all the time.

This description of how it happens in practice is pretty good:

You can pose an ATTEMPT:

Reginald smirks, then brings an arm up to lean on Nidonocu.

And wait to see if they pose a reaction:

Nidonocu glances down at the arm as it rests on his shoulder.

-or-

Phineus side-steps, avoiding contact with the arm.

Note that the above are all done with the free-form command. On most MMOs today, as well as in most MUDs, this might be called the “emote” command:

/emote does whatever they want.

Raph does whatever they want.

But of course most worlds also offer a huge array of pre-baked emotes, most of which permit targeting at other people, and which the recipient cannot control. Here’s a list from World of Warcraft, which includes stuff like

You bite . Ouch!

You scratch . How catty!

You cuddle up against .

You bonk on the noggin. Doh!

You brush up against and fart loudly.

You give a high five!

You lick .

You massage ’s shoulders.

You pounce on top of

You slap across the face. Ouch!

You tickle . Hee hee!

The basic contrast here is centered on who has the authority in the interaction. A standard MUD approach would grant the authority to the actor, not the target. A standard MUSH approach would grant authority to the target, not the actor.

The reasons for this divergence are complex and cultural; many MUSHes and MOOs would lean heavily on free-form emotes and poses, and would often have deep and intricate social behaviors heading well into extremely intimate territory. Players would form extreme attachments to personas and avatars, seeing them as proxies for themselves. The whole point of the game was social: roleplay, collaborative storytelling, or in OOC scenarios, of course, getting to know one another for real. Having a stranger come up and lick you (ewww!) in the middle of a Regency ballroom dance, let’s say, would be profoundly jarring. Hence, you see lengthy documents defining proper codes of conduct for participation in the MUSH space, such as this example from Arx.

1. Every player has agency over their own characters’ attempted actions, but not the consequences of the attempt.

This is something fairly universal to most role-playing games, but still often gives newer players some trouble. With the pose and @emit commands, players have the ability to write or describe anything, but really need to restrain themselves from describing the results of non-trivial actions. In other words, one character trying to hit another or attempt some difficult feat cannot just assume success. This would be decided by code built into the game (such as combat), the decision of staff (a GM arbitrating a decision), or the consent of all effected players in a scene (friends RPing a social scene and just making rolls as desired for randomizing results, for example). It is not appropriate to describe the actions of another character, or the results of actions upon them, since it removes agency from the other player. Players not having control over the results of their actions means their characters will have to deal with undesired consequences of actions, such as attempting something very dangerous and dying in the attempt. Staff fully knows how difficult players often take character death, and we don’t treat it lightly, but risk is necessary to add meaning to some storylines.

In MUDs, the point of the game was bashing orcs and killing giant spiders. Player characters die all the time, and it often means very little. The pace of the game was often far faster, and the array of “socials” (as the canned emotes were often called) were used in preference to the free-form emote command. An action like licking someone was taken extremely lightly, generally, and seen as an expression of utter goofiness, because people’s personas are held at a farther remove.

Though I never saw a set of socials that did this, it’s pretty easy to envision canned emotes that respect the privacy and personal space boundaries inherent in the spirit of the typical MUSH code of conduct. It would be pretty easy to simply edit the WoW canned emotes to be attempts instead of successes:

You try to bite .

You offer to scratch . How catty!

You attempt to bonk on the noggin. Doh!

(I tried rewriting the “lick” one here and pretty much failed at coming up with something that wasn’t gross).

This would leave the decision on how to respond to the target, and you can even envision an “/accept” command that could play the second half of the sequence. You could even make the first half simply not happen until /accept is performed, and then play the original WoW text.

Adding graphics

When we moved to graphical worlds, some of this became obligatory if we wanted to display it using character animations. A canned “hug” emote will result in someone just sticking their arms out and waving them about; unless the target is within range and positioned correctly, the animation will be to empty air. And if someone isn’t also reading the chat box, it will be nonsensical. You can either choose to simply not animate all of these powerful social tools… or you can solve the problem.

It’s worth a brief digression here on why it can be worth it to do the expensive thing, and try to solve the problem. In a graphical world, the textual form of all of these is dramatically weaker in terms of emotive impact. (In a textual world, this is very much not the case). Graphics pull the eye, and a huge amount of our brain processing power is designed to cope with all sorts of subtle social cues. I’ve written about this before at length, and we can see how little work has been done in the field since. But social bandwidth is a powerful tool to improve player retention. It increases connections and commitment between players, and reduces the degree to which they objectify others (thereby encouraging better behavior and less griefing).

In Star Wars Galaxies we went to great lengths to create as socially rich a communications system as we could; we still used the MUD-style impositional emotes, but tied as much as graphical support in as we could. We detected words embedded in your chat in order to affect body and facial animations. We attempted to set avatar eye line based on who was speaking most recently. We included a rich moods and adverbs system. The screenshot to the left shows off several of these things, including selection of chat bubble style as an additional channel to convey emotional content.

In Star Wars Galaxies we went to great lengths to create as socially rich a communications system as we could; we still used the MUD-style impositional emotes, but tied as much as graphical support in as we could. We detected words embedded in your chat in order to affect body and facial animations. We attempted to set avatar eye line based on who was speaking most recently. We included a rich moods and adverbs system. The screenshot to the left shows off several of these things, including selection of chat bubble style as an additional channel to convey emotional content.

In Metaplace, we had a far far poorer animation system because we were working with 2d images, sprite frames, streamed over the network. This meant adding new animations was extremely challenging and expensive. I asked for a very limited set of social actions: waving, pointing with arm outstretched, and sitting. And I built a hug system out of the point animation, after there was a bit of an outcry from players for it.

But Metaplace was a social world, not a MUD. The culture of the space was far more like a MUSH or MOO than it was like a hack n slash dragon slaying space. To make the hug work, we needed an automated consent system. The idea isn’t new; getting added as a friend in any game works the same way, and of course even Facebook offers consent systems for certain social activities, such as tagging people in photos or posts.

The flow of it went like this:

Buffy initiates a /hug command on a target Bob.

Bob receives a pop-up informing them that Buffy desires to hug him.

Bob accepts or rejects. If reject, nothing happens. If timed out, nothing happens.

If Bob accepts, Buffy is notified.

Buffy pathfinds to Bob.

Upon arrival at a precisely calculated position relative to Bob, Buffy plays the arm outstretched emote, but also notifies Bob of arrival.

Upon notification, Bob pivots in place to mirror Buffy’s position. The two overlapping avatars and outstretched arms overlap in such a way that it looks like a hug.

Any movement by either player breaks the tandem animation.

A /kiss system was added as extra support on top; it did exactly the same thing, except that it played little floating hearts over the couple.

This sort of thing is what is done in pretty much all forms of fighting game anyway. When a player in a fighting game executes some cool combo that results in grabbing the opponent in some way and slamming them to the ground, it’s termed a tandem animation; you have to get the two characters precisely positioned (often by “cheating” the real physics) in order to play the awesome cool effect with both characters moving in synchrony. This is why you typically lose control of the avatar while something like this is going on; we can’t let you have control and also have it look good. (It can also be used in pro-social ways, as in the synchronization of dance moves in Star Wars Galaxies).

LARPing

What I was advocating for in that talk which prompted this little essay, was for systems like the one in Metaplace or the one in MUSHes to be considered when designing social VR. In VR we rely heavily on the graphical equivalent of /pose and @emit, with actual physical movements tracked with the headset and controllers providing the “freeform” aspect of the input. Social VR doesn’t currently use canned commands all that much outside of facial expressions, because hands and heads can be so expressive. On the other hand, head and hands alone is of course going to hugely limit the canvas of possible social interaction, so I wouldn’t be at all surprised if more advanced avatar puppeteering would someday require either freeform tools for the body (VR suits or body tracking) or avatar control tools that work more like the systems in Galaxies and Metaplace.

But if social VR is going to lean on freeform input, then it needs a consent culture akin to that of the MUSH world — and actually, probably one even more robust than that, and that’s where the LARP enters the picture, particularly the Nordic LARP.

Nordic LARP is not just people dressing funny and running around in the woods shouting “Fireball!” at one another. It is used in school curricula in Scandinavia; it is used for therapy, for historical education, and for anti-bullying lessons.

The concept of consent can extend well beyond the simple examples I have discussed here. It essentially extends all the way through your Code of Conduct. In the Nordic LARP community there has been a lot of discussion and attention towards this topic. Here’s the briefest possible dip into the subject, from “The Consent and Community Safety Manifesto” on nordiclarp.org:

The 10 Principles of Consent and Community Safety

People are more important than larps. Larp organizers and communities must value the safety of their participants as their number one priority.

Each person’s body is their own. They alone may set their boundaries and say what makes them comfortable…

The 20 Statements of Support for Community Safety

I will give a clear and honest “yes, please” or “no, thank you” when I am asked for my consent, and negotiate more specifics if I feel they are needed.

I will respect the boundaries another person sets and accept that my boundaries may be different from someone else’s.

I will not touch another participant in-game or off-game, without their consent…

The 10 Larp Designer Commitments to Community Safety

With my community, I will create and maintain a Code of Conduct that outlines expected, encouraged, and prohibited behavior.

With assistance, as needed, I will create a harassment policy and reporting procedure for my larps which condemns harassment and establishes a clear and confidential way for participants to come forward if it is violated.

I will designate one or more people on my organizer team as Community Safety Coordinators and give these people the resources and respect they need to conduct Community Safety business…— heavily excerpted from nordiclarp.org

This has, of course, a lot in common with codes of conduct and EULAs and TOSes found elsewhere, with the notable difference that it offers that set of designer commitments; that of course calls to mind older rights documents for players.

Once you start thinking in terms of consent, it can force you to think in terms of consent up and down the entirety of the social system for your world. LARPers simply bump into the issues much faster, and therefore have tended to discuss them relatively unprompted, precisely because real-world engagement greatly increases vulnerability.

The bottom line

As social VR develops, it would be wise for its developers to think on the ways in which they are effectively treading old ground. I’ve singled out MUSHes, MUDs, MMOs, and LARPs here as models, but in point of fact, any public space designed for play is going to have developed best practices that are likely relevant. Theme parks, wilderness areas, and concert venues likely have applicable processes, cultural signposts, and policies too. To host a multiplayer virtual environment is to host and govern a space, and there are no shortage of models precisely because spaces are where we normally live.

And heck, it’d be nice if Facebook had a few more consent systems too. Adding people to groups without their consent? That’s a dark design pattern…!

August 19, 2017

Slides for my FDG17 talk on Reconciling Games

I have posted up slides for the keynote talk I gave at the Foundations of Digital Games conference. It was called “Reconciling Games” and it was about fish tanks. Well, fish tanks as an example of a naturally occurring ludic system that offers up surprising lessons for game design, across many disciplines: internal game economics and systems balancing, but also narrative, community design, and more.

I have posted up slides for the keynote talk I gave at the Foundations of Digital Games conference. It was called “Reconciling Games” and it was about fish tanks. Well, fish tanks as an example of a naturally occurring ludic system that offers up surprising lessons for game design, across many disciplines: internal game economics and systems balancing, but also narrative, community design, and more.

Among the key quotes from the talk (based on tweeted comments from attendees) are

“When game devs start a game, they usually don’t know what they’re making.”

“Games were born multiplayer.”

“Games are a medium of communication between players.”

“How many things are we not making because they aren’t framed as ‘games?'”

“The ball is not the game, the physics system around it is.”

“My favorite game is making games…. it’s one hell of a ludic system.”

“We all live in a digital fishbowl.”

“Every game I make is a society I tend.”

Unfortunately, the talk wasn’t recorded, and I spoke without notes. So you’ll have to decide for yourselves where those fall on the slides.

As a side note… this was actually the first time that I have ever attended FDG, or its original parent conference (famously held on cruise ships). I had been asked to attend many many times, particularly by the key mover in getting the whole thing going, John Nordlinger. It was really wonderful, and I wish I had been able to stay for the full event.

John passed away only a few weeks ago from accelerated ALS which had only recently been diagnosed. Sorry I took so long to go, John. You built an amazing community.

August 11, 2017

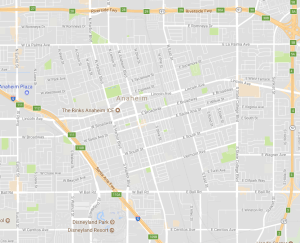

Simple Maps improvements

Map software drives me nuts, because it’s clearly designed only by engineers. I think all of these could be done with current data sets:

Map software drives me nuts, because it’s clearly designed only by engineers. I think all of these could be done with current data sets:

If current road segment is blue or yellow and next road segment is red: “Watch out, traffic is getting heavy ahead.”

If current road segment is red and next few road segments are clear: “Traffic is clearing up ahead.”

If past road segment is red, current one isn’t, but the one after is, “Don’t get your hopes up, traffic is still bad ahead.”

If current speed is significantly above average for cars in the next road segment: “Slow down, you’re about to hit traffic!”

If telling the user “turn left/right in n feet,” and there is more than one possible turn between the car’s position and the indicated turn, “Not this one, the next one” and “you want the third right.”

If approaching a turn in the directions, and traffic is heavy, scale the distance at which the driver is warned proportional to the traffic: “You want to try to get over to the right lane now, because it might be tricky.”

If about to make a turn, “This is the left turn you want.”

If about to make a turn left across traffic, and not onto a street, “Turn into parking on the left; keep an eye out for the sign!”

If target location is in an urban area and public parking lots are detected within 1/2m of target location, “Public parking is available nearby. Set that as the destination?”

If circling is detected and there are public parking lots nearby, “Do you want directions to available public parking?”

If approaching a gas station and the interval distance to the next gas station on the route is long, “This is the last chance to fuel up for n miles. How are you on gas?”

If a turn is missed and re-routing is triggered, “I think you missed your turn.”

If a correct and incorrect turn ahead are separated by an angle less than 90 degrees, “This next turn is tricky; you want (the first/the second/the rightmost) road, called name.”

If the next turn is at a T intersection, append “at the T” to the turn directions.

Left turns with no light onto red segments should be routed around: “You’ll never be able to make that left turn, there’s no gap in traffic. Let me find another route.”

If path changes (reroutes, traffic estimates, etc) in such a way that destination time changes notably past the original destination time, “You’re going to get there ten minutes later than I originally thought. Do you want to call anyone to let them know you’ll be late?”

If car is moving at very slow speed and in a red segment, “Wow, traffic SUUUUCCKS.”

We often think that accurate feedback is adequate feedback. But that’s not what people actually need. Relatively few people can judge how close they are to a turn in 800 feet when moving a 20mph versus 30mph. People shouldn’t need to watch the screen to be told “you’re going to need to stand on the brakes in three seconds.” And directions shouldn’t guide you to unprotected left turns where you will be stuck waiting half an hour for a break in traffic.

August 6, 2017

The Sunday Poem: Made of Moon

every corner we turned there was the moon

north south east west the moon

full and every corner bigger

until the sky was made of moon

you stood between me and moon

and said i'll take the hit

and you did

now when i see the moon i reach

it is always waning